1. Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening syndrome of pathologic immune activation and severe hyperinflammation [

1,

2]. The condition is characterized by a dysregulated and uncontrolled immune response, culminating in widespread tissue damage, multi-organ failure, and high mortality if not recognized and treated with urgency [

3]. The core pathophysiology involves a failure of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) and natural killer (NK) cells to clear an antigenic trigger [

4]. This defect in cytolytic function results in the sustained activation of macrophages and a massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and various interleukins (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, IL-18) [

1,

5]. This cytokine cascade drives the classic clinical manifestations of HLH, such as prolonged fever, splenomegaly, profound cytopenia, and hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes, as defined by the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria [

6].

HLH can be classified as primary (familial), resulting from inherited genetic mutations affecting immune regulation, or secondary (acquired), which is more common in adults and is precipitated by an identifiable trigger [

2,

7]. These triggers include severe infections, autoimmune diseases, and, most ominously, malignancies [

8]. This raises a central question that this paper aims to address: How can an individual with a seemingly intact immune system develop HLH, a syndrome defined by profound immune dysregulation? This question frames the search for alternative pathogenic mechanisms beyond classic immunodeficiency. Among these secondary causes, malignancy-associated HLH (M-HLH) carries the poorest prognosis, presenting a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge [

9,

10]. Lymphoma is the most frequently identified neoplastic driver of HLH in the adult population [

11].

Lymphoma-associated HLH (LA-HLH), is characterized by an aggressive clinical course and historically poor outcomes, with mortality rates often exceeding 50% [

10,

12]. A substantial body of evidence from large, international cohorts and systematic reviews has defined a consensus regarding the prevalence of different lymphomas precipitating LA-HLH. Multiple studies have demonstrated that non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are the dominant drivers. In contrast, Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is consistently reported as a rare cause [

11,

13]. For instance, a 2024 review of 542 LA-HLH patients found T-cell/NK-cell NHL (45.2%) and B-cell NHL (45.6%) to be co-dominant etiologies, whereas Hodgkin lymphoma accounted for only 8.9% of cases [

14]. Similarly, a 2023 multi-national report found B-cell NHL (55%) and T-cell/NK-cell NHL (35%) to be the most common subtypes, with Hodgkin lymphoma comprising just 10% [

15]. Other large analyses report the prevalence of HL in LA-HLH to be between 2.6% and 5.8% [

11,

16].

Synthesizing these independent, large-scale data sources reveals that across diverse geographic and ethnic populations, Hodgkin lymphoma is an infrequent cause of LA-HLH, almost invariably accounting for less than 10% of cases. This study presents a retrospective, exploratory analysis from two large, urban medical centers serving a predominantly Hispanic patient population. The primary aim of this investigation was to characterize the clinical features, lymphoma subtype distribution, and treatment outcomes of patients with LA-HLH within this specific demographic in order to generate novel hypotheses regarding the disease’s underlying pathophysiology. A secondary aim was to explore the influence of key comorbidities, particularly HIV infection, on the clinicopathological presentation of the disease, with the goal of identifying distinct patterns that could inform both diagnosis and management.

To further probe the immunological mechanisms potentially driving these patterns, this study also aimed to incorporate an analysis of the soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R, also known as sCD25). sIL-2R is the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor, which is proteolytically cleaved from the surface of activated T-lymphocytes [

26]. Its elevated serum level is therefore considered a direct and quantitative measure of systemic T-cell activation, a central event in the pathophysiology of HLH [

7,

26]. Recognizing its reliability as an indicator of immune dysregulation, an elevated sIL-2R level (>2,400 U/mL) was formally incorporated into the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria. Beyond its diagnostic utility, sIL-2R has also been established as a potent prognostic marker. In various lymphomas, high levels correlate with greater tumor burden, more aggressive histology, and poor survival [

27]. Similarly, in HLH, extreme elevations (>10,000 U/mL) are strongly associated with increased mortality risk [

28,

29]. This study leverages sIL-2R analysis to provide a deeper biological context for the observed clinical findings and to further delineate the immunological differences between patient subgroups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Cohort

This study was a retrospective, multicenter analysis of adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) diagnosed with HLH between January 1, 2000, and January 31, 2024. The patient cohort was identified through a comprehensive review of electronic health records at two tertiary care urban academic medical centers: Harris Health Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, Texas, and Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach, Florida. An initial search of institutional databases using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for HLH identified a total of 78 patients with a discharge diagnosis of HLH. The medical records of these 78 patients were then manually reviewed to confirm the diagnosis and identify the underlying etiology. Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of both lymphoma and HLH were included in the final LA-HLH cohort. This process resulted in a total of 20 patients who met the full inclusion criteria. The study was conducted in accordance with Baylor College of Medicine and Mount Sinai Medical Center institutional review board approval.

2.2. Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of HLH was confirmed according to the internationally recognized HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria, which require the fulfillment of at least five of the eight specified clinical and laboratory parameters. The HLH-2004 criteria were utilized for case identification, as they represent the most widely accepted diagnostic standard and enabled consistent ICD-based screening across the 24-year study period. Acknowledging that these criteria were originally developed in pediatric populations and that their sensitivity and specificity remain insufficiently characterized in adult and malignancy-associated HLH, we included only patients whose diagnosis was confirmed by a hematologist following comprehensive diagnostic evaluation and exclusion of alternative etiologies. Cases with incomplete specialized testing (e.g., soluble IL-2 receptor, NK cell activity) were included if at least five HLH-2004 criteria were fulfilled based on available data.

Lymphoma diagnoses were confirmed by formal histopathological review of tissue biopsies (e.g., lymph node, bone marrow).

2.3. Data Collection

A standardized data collection form was used to extract a comprehensive set of variables from the electronic health records. These included: Demographics: Age at diagnosis, gender, and self-reported race and ethnicity. Comorbidities: HIV status (confirmed by serology) and evidence of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) viremia, defined as a positive EBV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay with a quantifiable viral load. Lymphoma Characteristics: Including histological subtype. Clinical and Laboratory Data at HLH Diagnosis: Presence of fever (highest recorded temperature), presence of hepatosplenomegaly on physical examination or imaging, complete blood count (hemoglobin, platelet count, absolute neutrophil count), ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), triglycerides, fibrinogen, liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase), international normalized ratio (INR), and, where available, soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R or sCD25) levels, which were measured as part of the clinical workup using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Treatment and Outcomes: Details of lymphoma-directed chemotherapy regimens, HLH-directed therapies (e.g., corticosteroids, etoposide), and clinical outcomes, including achievement of complete remission (CR) of lymphoma and all-cause mortality.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables between the HIV-negative and HIV-positive groups. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The boxplot of sIL-2R levels was generated on a logarithmic scale to accommodate the wide range of values observed.

3. Results

3.1. Etiology of HLH in the Overall Cohort

Over the 24-year study period, a total of 78 cases of adult HLH were identified across the two centers. Malignancy was the most common trigger, accounting for 39.7% (n=31) of all HLH cases. Among these M-HLH cases, lymphoma was the predominant underlying neoplasm, comprising 20 of the 31 cases (64.5% of M-HLH and 25.6% of all HLH). The remaining cases of HLH were associated with infections (25.6%), autoimmune diseases (20.5%), or were classified as idiopathic (14.1%) when no clear trigger could be identified (

Table 1).

3.2. Baseline Characteristics of the LA-HLH Cohort

The final LA-HLH cohort consisted of 20 patients. The baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics are detailed in

Table 2. The cohort had a median age of 40 years (range, 22-70) and was predominantly male (80%, n=16). A defining feature of the cohort was its ethnic composition, with 70% (n=14) of patients being of Hispanic descent. Coexisting viral infections were common, with 35% (n=7) of patients being HIV-positive and 75% (12 of 16 patients tested) having detectable EBV viremia. Among patients with HIV, 66.7% were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Clinically, all patients presented with febrile episodes (median peak temperature 39.2 °C, range 38.1–41.0 °C) and cytopenias involving two or more hematopoietic lineages. The median hemoglobin nadir was 6.3 g/dL (IQR 5.5–6.8), median platelet nadir was 35 × 103/µL (IQR 3–151 × 103/µL), and median peak ferritin level was 16,375 ng/mL (IQR 2,682–147,191). Laboratory findings were consistent with severe hyperinflammation, including markedly elevated ferritin (median 16,375 ng/mL), LDH (median 1,370 U/L), and evidence of coagulopathy and liver dysfunction.

3.3. Primary Finding: A Predominance of Hodgkin Lymphoma

The most significant and unexpected observation of this study was the distribution of underlying lymphoma subtypes. In contrast to the established literature demonstrating NHLs as the primary drivers of LA-HLH, the most common malignancy in this cohort was Hodgkin lymphoma. HL accounted for 60% (n=12) of all LA-HLH cases. The remaining cases were comprised of T-cell lymphoma (20%, n=4), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL; 10%, n=2), marginal zone lymphoma (MZL; 5%, n=1), and primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL; 5%, n=1).

3.4. Stratified Analysis by HIV Status Reveals Distinct Clinicopathological Entities

To investigate potential drivers of this unusual subtype distribution, the cohort was stratified by HIV status (

Table 3). The HIV-negative group (n=13) was significantly younger, with a median age of 34 years (vs. 52 years in the HIV-positive group;

p=0.04). This group was almost exclusively driven by Hodgkin lymphoma, which accounted for 85% (11/13) of cases. In contrast, the HIV-positive group (n=7) was predominantly driven by non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which comprised 71% (5/7) of cases. The association between HIV-negative status and HL as the underlying lymphoma type was statistically significant (

p=0.005). Furthermore, the inflammatory phenotype differed between the two groups. Patients in the HIV-positive group presented with a more profound systemic inflammatory response, evidenced by markedly higher median ferritin levels (77,346 ng/mL) compared to the HIV-negative group (6,241 ng/mL), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (

p=0.11).

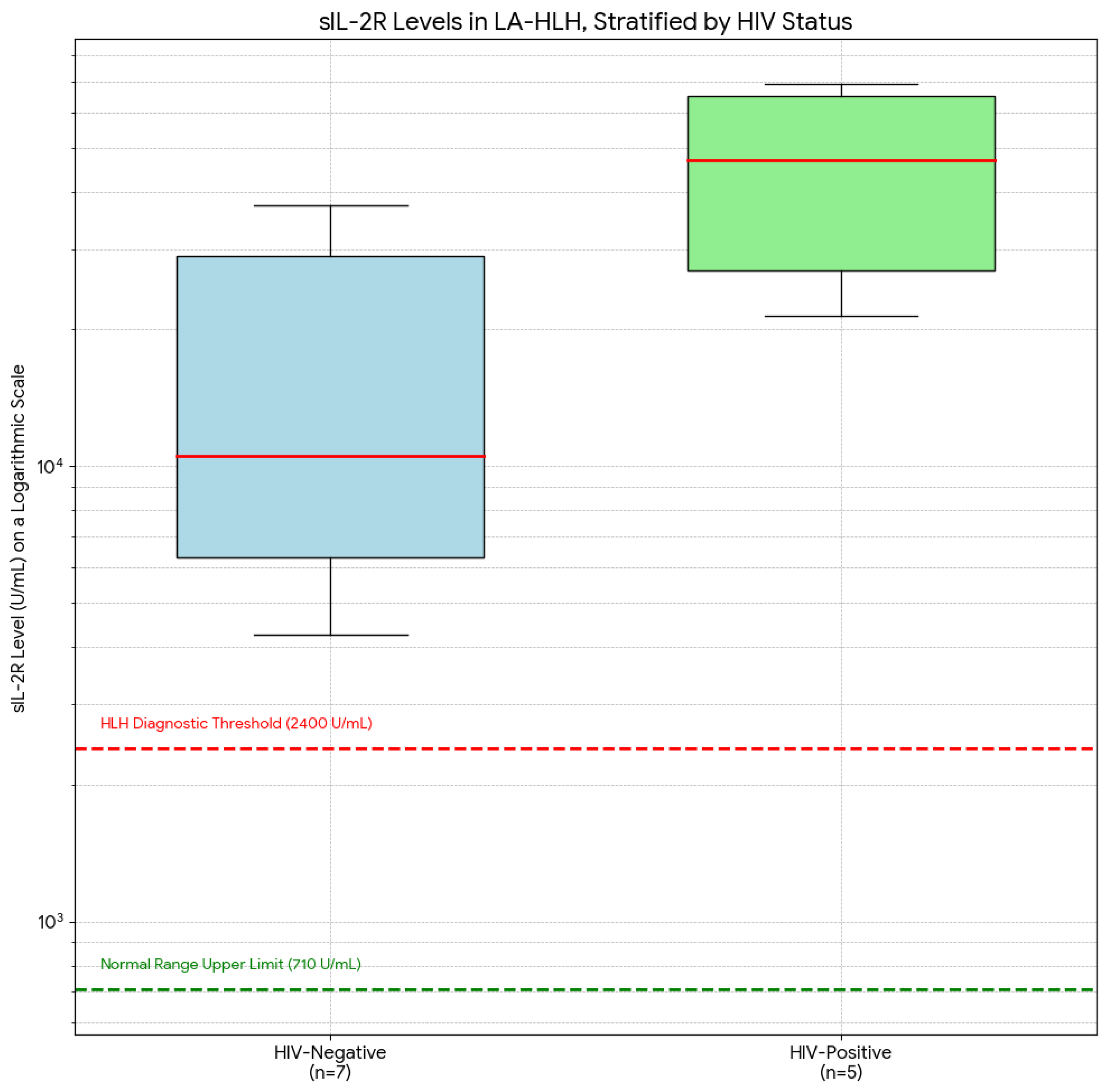

3.5. Soluble IL-2 Receptor Levels Provide an Immunological Correlate for the Clinical Profiles

To further investigate the immunological underpinnings of the distinct clinical phenotypes observed, we analyzed serum sIL-2R levels, a key marker of T-cell activation. Data were available for 12 of the 20 patients in the LA-HLH cohort, including 7 from the HIV-negative group and 5 from the HIV-positive group.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, all 12 patients had sIL-2R levels markedly above both the normal upper limit (710 U/mL) and the HLH-2004 diagnostic threshold (2,400 U/mL), consistent with a diagnosis of HLH. However, stratification by HIV status revealed a statistically significant difference in the magnitude of this elevation.

The OHI index, a binary inflammatory metric defined by ferritin >1,000 ng/mL and soluble IL-2 receptor >3,900 U/mL, was calculated for patients with available data. Among the 12 evaluable cases, 100% demonstrated a positive OHI index. Consistently, all patients in this subgroup also had HScores >240, a threshold associated with a diagnostic sensitivity of 98–99%.

The HIV-positive group (n=5) exhibited extreme elevations of sIL-2R, with a median level of 45,210 U/mL (IQR: 30,115 - 65,890 U/mL). In contrast, the HIV-negative group (n=7) had significantly lower levels, with a median of 11,050 U/mL (IQR: 4,120 - 35,400 U/mL). This difference was statistically significant (p=0.035). This finding is also summarized in

Table 3.

3.6. Histopathological Features of the Hodgkin Lymphoma Subgroup

Given the unexpected predominance of HL, a detailed review of the histopathology for these 12 cases was conducted. This analysis revealed among the 12 patients with HL-associated HLH (HL-HLH), 58% (n=7) were Hispanic. Of these 7 Hispanic patients, all (100%) had the mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma (MCHL) subtype. In contrast, the HL subtypes in the non-Hispanic patients were more varied (

Table 4).

3.7. Treatment and Clinical Outcomes

Outcome data were available for 19 of 20 patients, with an overall mortality rate of 57.9% (11/19), consistent with the historically poor prognosis for LA-HLH. Most patients were managed with a combination of therapies, receiving HLH-directed treatments (high-dose corticosteroids in 80% and etoposide in 70%) administered concurrently or sequentially with lymphoma-directed chemotherapy. Specific regimens were heterogeneous and tailored to the underlying lymphoma histology and the patient’s clinical status (

Table 5). Due to profound cytopenias and organ dysfunction, etoposide dose reductions were necessary in half of the patients who received it. Despite aggressive management, outcomes remained poor across most subtypes, with the highest mortality seen in patients with T-cell lymphoma (75%).

Table 5.

Lymphoma-Directed Treatment, HLH Management, and Clinical Outcomes (N=19).

Table 5.

Lymphoma-Directed Treatment, HLH Management, and Clinical Outcomes (N=19).

| Lymphoma Subtype (N) |

Lymphoma Treatment Regimens (N) |

HLH Management (N) |

Outcome (N, %) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma (11) |

|

|

|

| |

ABVD (4) |

Etoposide + Steroid (8) |

Death (6, 54.5) |

| |

ICE (3) |

Steroid Only (2) |

CR from HLH (5, 45.5) |

| |

AVD (2) |

None (1) |

|

| T-cell lymphoma (4) |

None (2) |

|

|

| |

CHOP-like (2) |

Etoposide + Steroid (4) |

Death (3, 75.0) |

| |

SMILE (1) |

|

Hospice (1, 25.0) |

| |

Other (1) |

|

|

| DLBCL (2) |

|

|

|

| |

R-CHOP (1) |

Etoposide + Steroid (1) |

CR from HLH (1, 50.0) |

| |

R-CEOP (1) |

None (1) |

Death (1, 50.0) |

| PCNSL (1) |

|

|

|

| |

HD-MTX (1) |

Steroid Only (1) |

CR from HLH (1, 100.0) |

| MZL (1) |

|

|

|

| |

Bendamustine/Rituximab |

Etoposide + Steroid (1) |

Death (1, 100.0) |

| Total (19) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Death (11, 57.9) |

| |

|

|

Non-Death (8, 42.1) |

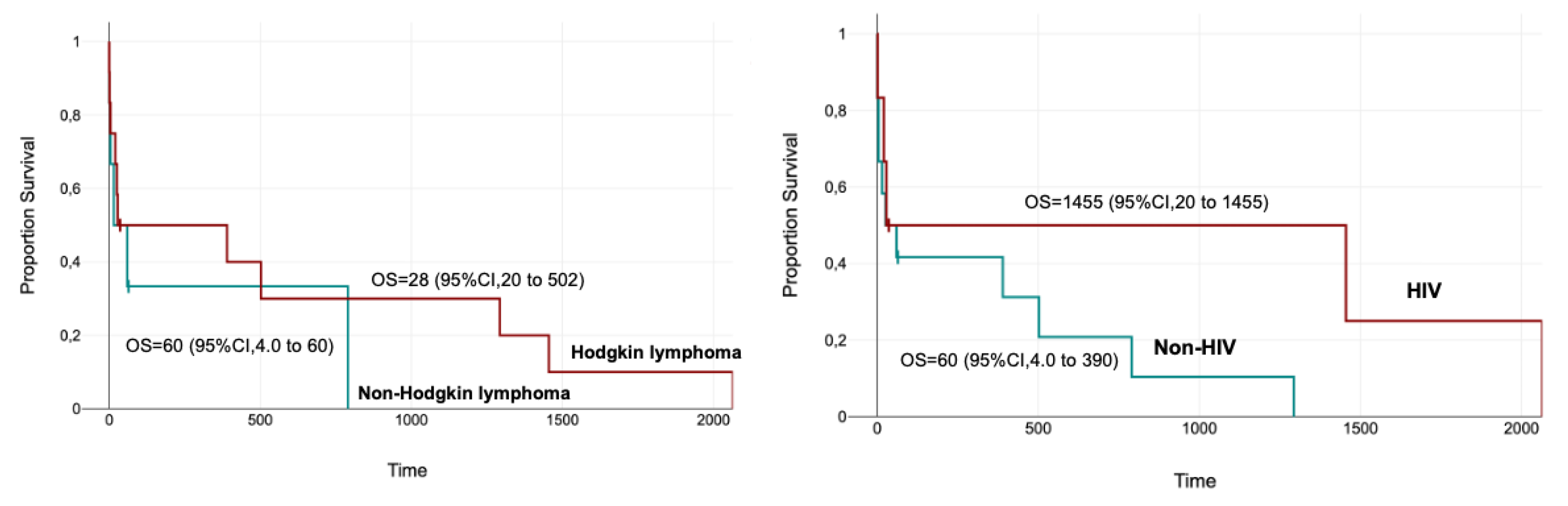

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrate no statistically significant difference in overall survival between patients with Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (median OS: 28 vs 60 days, p = 0.44). Similarly, survival did not differ significantly when stratified by HIV status (median OS: 1455 vs 60 days for HIV-positive vs HIV-negative patients, p = 0.175).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrate no statistically significant difference in overall survival between patients with Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (median OS: 28 vs 60 days, p = 0.44). Similarly, survival did not differ significantly when stratified by HIV status (median OS: 1455 vs 60 days for HIV-positive vs HIV-negative patients, p = 0.175).

4. Discussion

This study’s primary and most striking observation, which requires validation in a larger cohort, is the 60% prevalence of Hodgkin lymphoma as the underlying malignancy. As detailed previously, major international cohorts and systematic reviews consistently report HL as a rare cause of LA-HLH, typically accounting for less than 10% of cases [

14,

15]. This departure from the expected distribution prompts our first hypothesis: the unusual predominance of HL-driven HLH may be linked to ethnicity-specific factors. A plausible biological pathway was constructed by connecting observations from the current data with established lymphoma epidemiology. The first piece of evidence is the histopathological finding that 100% of the Hispanic patients with HL-HLH had the mixed cellularity (MCHL) subtype. This finding aligns with and extends previous epidemiological research. A large comparative study of over 13,000 patients found that Latin American patients had a significantly higher prevalence of the MCHL subtype compared to other US ethnic groups (26% vs. 13-19%) [

17]. The second link is the strong and well-documented association between the MCHL subtype and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, with EBV being present in the tumor cells in up to 75% of MCHL cases [

18]. Finally, EBV is one of the most common infectious triggers for HLH, and its reactivation is strongly implicated in the development of hyperinflammatory syndromes, particularly in the context of underlying immunodeficiency or malignancy [

19,

20]. Therefore, it is plausible that the high rate of HL-HLH observed in this predominantly Hispanic cohort may be due to these patients possessing an intrinsically greater capacity to provoke the systemic hyperinflammation that defines HLH, thus predisposing this patient population to this rare but devastating complication.

Beyond the role of ethnicity, the stratified analysis by HIV status revealed additional complexity, suggesting that LA-HLH may not represent a single, uniform entity. Instead, the findings support a model of at least two distinct pathobiological pathways, with HIV status serving as a critical determinant of both the underlying lymphoma biology and the resulting inflammatory phenotype—conceptually visualized as two divergent routes converging on a shared clinical syndrome. While these observations delineate differing clinical contexts—classic secondary HLH in immunocompromised hosts versus lymphoma-driven HLH in immunocompetent patients—mechanistic interpretations remain speculative. We cautiously propose that, in certain Hodgkin lymphoma–associated cases, tumor microenvironmental cytokine spillover may contribute to systemic immune activation. However, confirmatory evidence, such as paired tumor–serum cytokine profiling or EBER in situ hybridization, is currently lacking. Validation of this hypothesis will require prospective studies incorporating molecular and spatial analyses of the tumor microenvironment. We further discuss the hypothesis of two distinct clinical–biological profiles within LA-HLH, potentially shaped by HIV status and immune context.

4.1. The “Classic” Secondary HLH Pathway: HIV-Positive, NHL-Driven Disease

The clinical picture observed in the HIV-positive subgroup aligns with the more traditionally understood model of secondary HLH. These patients were older and predominantly developed aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas, presenting with an extreme hyperinflammatory state (median ferritin >10,000 ng/mL). This presentation can be interpreted as the result of a failure of immune surveillance. In patients with advanced HIV and profound CD4+ T-cell depletion, the immune system loses its ability to control latent viral infections [

21]. This immunodeficiency allows for the reactivation and uncontrolled replication of oncoviruses, most notably EBV, which is a known driver of aggressive B-cell lymphomas like DLBCL and primary CNS lymphoma in this population [

22]. The convergence of an aggressive, virally-driven malignancy with a severely compromised immune system creates an environment that is susceptible to inflammatory reactions [

23]. This may explain the extreme hyperferritinemia and poor outcomes seen in this group, which could represent a classic example of trigger-induced secondary HLH in a profoundly immunocompromised host.

4.2. A Proposed Pathophysiology: The “TME Spillover” Hypothesis in HIV-Negative Patients

The possible novel scenario in our HIV-negative group is described by their distinct sIL-2R profile. While still pathologically elevated, their median sIL-2R level was approximately four-fold lower than that of the HIV-positive group. This quantitative difference in the degree of systemic T-cell activation raises a different mechanistic explanation and lends support to our ‘TME spillover’ hypothesis. The key question is: what is the source of sIL-2R in these patients? In classic HLH, the source is systemic, activated T-cells [

7]. However, in B-cell malignancies like HL, an alternative mechanism has been described. The malignant cells themselves often do not express high levels of CD25 [

30]. Instead, the inflammatory tumor microenvironment (TME) is the primary driver [

31]. The TME of HL is densely populated by various immune cells, including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [

31]. Studies have shown that these TAMs can secrete enzymes, particularly matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), which cleave the CD25 molecule from the surface of bystander T-cells within the TME [

32]. The sIL-2R measured in the serum is therefore not necessarily a marker of a primary systemic T-cell disorder, but rather a direct byproduct of the intense, localized inflammatory activity within the lymph node [

32].

This provides a plausible molecular mechanism for the “spillover” concept. The defining histopathological feature of Hodgkin lymphoma is the scarcity of malignant Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells amidst an inflammatory environment [

33]. The model posits that this infiltrate, organized by the HRS cells through cytokine and chemokine secretion, is the source producing the sIL-2R [

30]. We therefore hypothesize that the moderately elevated sIL-2R levels in our HIV-negative, HL-driven cohort could represent the immunological ‘spillover’ from this TME-centric process. In this model, the HL TME is a site of contained, intense inflammation where sIL-2R is continuously generated. In susceptible individuals, it is conceivable that a failure of homeostatic mechanisms allows this locally produced biomarker of immune activation to accumulate systemically, crossing a threshold that triggers the full-blown HLH phenotype. It is important, however, to frame this as a speculative model, as we lack direct evidence such as a comparison of systemic cytokine levels in HL patients with and without HLH. One might assume that some level of systemic cytokine signaling is always present to recruit inflammatory cells to the lymph node;[

30] our model suggests a quantitative threshold is crossed during decompensation.

4.3. sIL-2R as a Potential Tool for Diagnosis and Risk Stratification in LA-HLH

Our findings also highlight the nuanced utility of sIL-2R in the diagnosis of LA-HLH. While an elevated level is a core diagnostic criterion, the magnitude of elevation may provide insight to the underlying pathophysiology. Extreme levels (>30,000 U/mL) in the context of a suspected lymphoma could heighten suspicion for an aggressive NHL in an immunocompromised host, as seen in our HIV-positive cohort. Conversely, more moderate elevations in an immunocompetent patient might suggest a process like HL, where the inflammation is primarily TME-derived.

From a prognostic standpoint, our data reinforce the role of sIL-2R as a critical risk-stratification tool. The different levels between our groups suggest that HIV-positive patients with LA-HLH may present with an intrinsically higher-risk biological profile. This could inform therapeutic decisions, potentially arguing for more aggressive upfront management or earlier consideration for novel targeted therapies in this population. Conversely, the lower levels in the HIV-negative group, while still pathological, may define a subgroup with a different risk profile, although outcomes remained poor overall in our small cohort.

4.4. Potential Clinical Implications and Future Directions

The findings from this exploratory study have potential clinical implications. The most significant is the suggestion that clinicians might need to re-evaluate the differential diagnosis of HLH. The data suggest that Hodgkin lymphoma should be considered as a potential underlying cause, particularly in young, HIV-negative individuals of Hispanic descent. This would represent a potential reversal of current clinical thinking, which correctly places T-cell and aggressive B-cell lymphomas at the top of the differential for LA-HLH. An expedited lymph node biopsy remains paramount, but this finding may guide clinicians to consider HL more strongly in the appropriate demographic context.

These findings also delineate a clear path for future research. There is a need for larger, prospective, multi-ethnic cohort studies to validate the observation of high prevalence of HL-HLH in Hispanic populations and to explore these associations in other ethnic groups. Further, molecular studies of the TME in patients who develop HL-HLH are warranted. Techniques such as cytokine profiling, spatial transcriptomics, and single-cell RNA sequencing could be used to directly test the proposed “TME spillover” hypothesis by comparing the cellular and cytokine composition within tumors from HL-HLH patients to those of HL patients who do not develop this complication. Such studies could identify the specific mechanisms that cause localized TME inflammation to become a systemic, life-threatening syndrome.

5. Limitations

This study has several important limitations that must be acknowledged. Its retrospective design introduces the potential for multiple forms of bias and relies on the completeness and accuracy of electronic health records originally created for clinical care, not research. The small sample size of 20 LA-HLH patients, while significant for such a rare condition, limits the statistical power for subgroup analyses. The p-values generated from comparing very small groups (n=13 vs. n=7) are unstable and should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating only. This limitation is particularly relevant for the subgroup analysis of sIL-2R levels, which was performed on an even smaller subset of 12 patients (7 HIV-negative and 5 HIV-positive) and must be considered strictly hypothesis-generating. Given the small subgroup sizes, these statistical findings should be interpreted with caution and require validation in larger cohorts.

As noted at the beginning of the discussion, the study is particularly susceptible to Selection and Referral Bias. The study was conducted at two large, urban, tertiary medical centers that serve not only as referral hubs for complex cases but also as safety-net institutions for unique sociodemographic groups, including underinsured and immigrant populations. This could lead to a disproportionate number of patients with rare presentations like HL-HLH, potentially inflating its observed prevalence relative to the broader, multi-institutional cohorts established in the literature. This specific patient demographic may have distinct patterns of healthcare access or unique environmental and infectious exposures that could act as significant confounding variables. Therefore, the observed association between HL-HLH and ethnicity may be driven by these environmental factors rather than a purely genetic predisposition.

Further, reliance on existing medical records means that data for certain variables, particularly specialized diagnostic tests like sCD25 or NK cell activity, were not uniformly available for all patients across the 24-year period. For example, twelve of the twenty patients in the LA-HLH cohort had sCD25 levels measured in their EMR. This missing information could impact the characterization of the cohort. The findings from this specific demographic—predominantly Hispanic patients at two urban centers—may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups or geographic locations. The unique observations in this cohort may be due to specific genetic, environmental, or social factors that are not present in the larger, more heterogeneous populations studied in previous international reports.

6. Conclusions

This exploratory, multicenter analysis of a predominantly Hispanic cohort found what appears to be an unexpectedly high prevalence of Hodgkin lymphoma driving LA-HLH. This finding contrasts with established literature, which identifies non-Hodgkin lymphomas as the primary trigger for this syndrome. Our analysis, strengthened by the inclusion of immunological biomarker data, suggests the hypothesis that LA-HLH may encompass at least two distinct pathobiological pathways determined by host immune status. The first is a “classic” secondary HLH in immunocompromised, HIV-positive individuals, driven by aggressive NHL and characterized by extreme systemic T-cell activation, as evidenced by profoundly elevated sIL-2R levels. The second is a more novel proposed pathway in immunocompetent, HIV-negative patients, where HLH appears to be a possible systemic “spillover” from the Hodgkin lymphoma TME, a process potentially reflected by more moderate, yet still pathological, sIL-2R elevations. These preliminary findings underscore the need for larger studies to validate these pathways and to explore the ethnic and molecular factors predisposing patients to this devastating syndrome.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and K.M.C.; methodology, M.B.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B., K.M.C. and H.N.; formal analysis, M.B. and K.M.C.; investigation, M.B., K.M.C. and H.N.; resources, K.M.C.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., K.M.C., and H.N.; writing—review and editing, M.B., K.M.C., H.N., C.R., A.L., J.B. and M.M.; visualization, H.N.; supervision, K.M.C., J.B. and M.M.; project administration, J.B. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Martha Mims is supported by CPRIT RP210143.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, please add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number for studies involving humans or animals. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine (H-57187, 8/4/2025) and Mount Sinai Medical Center (FWA00000176, 5/6/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions, as they contain protected health information (PHI). A limited, de-identified dataset may be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Requests will be reviewed to ensure they are for legitimate scientific inquiry and will require the completion of a data use agreement (DUA) in accordance with institutional policies.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used Google Gemini for the purpose of generating Figure 1. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Diseases and Syndromes: |

|

| HLH |

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. |

| LA-HLH |

Lymphoma-associated Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. |

| M-HLH |

Malignancy-associated Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus. |

| Lymphoma Subtypes: |

|

| HL |

Hodgkin lymphoma. |

| NHL |

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. |

| DLBCL |

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. |

| MCHL |

Mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma. |

| MZL |

Marginal zone lymphoma. |

| PCNSL |

Primary Central Nervous System (CNS) lymphoma. |

| Cellular and Molecular Terms: |

|

| CD25 |

Cluster of Differentiation 25 (alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor). |

| CNS |

Central nervous system. |

| CR |

Complete remission. |

| CTLs |

Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. |

| EBV |

Epstein-Barr virus. |

| HRS |

Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (cells). |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon-gamma. |

| IL |

Interleukin (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, IL-18). |

| MMP-9 |

Matrix metalloproteinase-9. |

| NK |

Natural killer (cells). |

| sIL-2R |

Soluble interleukin-2 receptor. |

| TAMs |

Tumor-associated macrophages. |

| TME |

Tumor microenvironment. |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha. |

| Lab Tests and Clinical Measures: |

|

| AST |

Aspartate aminotransferase. |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. |

| ICD |

International Classification of Diseases. |

| INR |

International normalized ratio. |

| IQR |

Interquartile range. |

| LDH |

Lactate dehydrogenase. |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction. |

| Chemotherapy Regimens: |

|

| ABVD |

Doxorubicin: bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine. |

| AVD |

Doxorubicin: vinblastine, dacarbazine. |

| CHOP |

Cyclophosphamide: doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone. |

| HD-MTX |

High-dose methotrexate. |

| ICE |

Ifosfamide: carboplatin, etoposide. |

| R-CEOP |

Rituximab: cyclophosphamide, etoposide, vincristine, prednisone. |

| SMILE |

Dexamethasone: methotrexate, ifosfamide, L-asparaginase, etoposide. |

References

- Ramos-Casals, M.; Brito-Zerón, P.; López-Guillermo, A.; Khamashta, M.A.; Bosch, X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 2014, 383, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosée, P.; Horne, A.; Hines, M.; von Bahr Greenwood, T.; Machowicz, R.; Berliner, N.; Birndt, S.; Gil-Herrera, J.; Girschikofsky, M.; Jordan, M.B.; et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood 2019, 133, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crayne, C.B.; Albeituni, S.; Nichols, K.E.; Cron, R.Q. The Immunology of Macrophage Activation Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, G.; Shenoi, S.; Hughes, G.C. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: An update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 34, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arca, M.; Fardet, L.; Galicier, L.; Rivière, S.; Marzac, C.; Aumont, C.; Lambotte, O.; Coppo, P. Prognostic factors of early death in a cohort of 162 adult haemophagocytic syndrome: impact of triggering disease and early treatment with etoposide. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 168, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henter, J.I.; Horne, A.; Aricó, M.; Egeler, R.M.; Filipovich, A.H.; Imashuku, S.; Ladisch, S.; McClain, K.; Webb, D.; Winiarski, J.; et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2007, 48, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, M.B.; Allen, C.E.; Weitzman, S.; Filipovich, A.H.; McClain, K.L. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 2011, 118, 4041–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoref-Lorenz, A.; Murakami, J.; Hofstetter, L.; Iyer, S.; Alotaibi, A.S.; Mohamed, S.F.; Miller, P.G.; Guber, E.; Weinstein, S.; Yacobovich, J.; et al. An improved index for diagnosis and mortality prediction in malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 2022, 139, 1098–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauft, J.; Schenk, T.; Ernst, T.; Schnetzke, U.; Hochhaus, A.; La Rosée, P.; Birndt, S. Lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (LA-HLH): a scoping review unveils clinical and diagnostic patterns of a lymphoma subgroup with poor prognosis. Leukemia 2024, 38, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, L.; Li, L.; Xie, W.; Tan, Y.; Ye, X. Clinical features and prognostic analysis of lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: A report of 139 cases. Oncol. Lett. 2022, 25, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Lu, X.; Wang, C.; et al. Pathological Subtyping, Outcomes, and Survival Trends of Lymphoma-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: A Multicenter Analysis of 464 Patients. Blood 2024, 144, 3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardet, L.; Galicier, L.; Lambotte, O.; Marzac, C.; Aumont, C.; Chahwan, D.; Coppo, P.; Hejblum, G. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 2613–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcarcel, B.; Garcia, A.; Rivarola, S.; Stemmelin, G.; Arrua, M.; von Glasenapp, S.; Quiroz, A.; Warley, F.; Orlova, M.; Vasquez, J.; et al. Comparing the distribution of Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes and survival outcomes between Latin American and US patients. Blood Glob. Hematol. 2025, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.I. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flerlage, J.E.; Metzger, M.L.; Bartlett, N.L. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: A Case Series and a Review of the Literature. J. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 37, 284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, C.P.; Shannon-Lowe, C.; Gothard, P.; Kishore, B.; Neilson, J.; O’Connor, N.; Rowe, M. Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults characterized by high viral genome load within circulating natural killer cells. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, R.; Shrestha, P.; Sharma, P.; et al. A Rare Case of Epstein-Barr Virus-Provoked Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis and Co-existing Hodgkin Lymphoma in a Newly Diagnosed HIV Patient. Cureus 2023, 15, e41151. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, R.A. Epstein-Barr Virus and Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 8, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, J.; Lee, D.; et al. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Resembling Recurrent Follicular Lymphoma: A Case Report. Clin. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 29, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tabaja, H.; Kanj, A.; El Zein, S.; Comba, I.Y.; Chehab, O.; Mahmood, M. A Review of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Patients With HIV. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Gan, X.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Shen, K.; Yang, Y.; Niu, T. Epstein-Barr Virus-Positive Lymphoma-Associated Hemophagocytic Syndrome: A Retrospective, Single-Center Study of 51 Patients. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 882589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, C.; Sabattini, E.; Agostinelli, C. Immune Microenvironment Features and Dynamics in Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Gloghini, A.; Carlo-Stella, C. Tumor microenvironment contribution to checkpoint blockade therapy: lessons learned from Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2023, 141, 2187–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamma, R.; Ingravallo, G.; Gaudio, F.; d’Amati, A.; Masciopinto, P.; Bellitti, E.; Lorusso, L.; Annese, T.; Benagiano, V.; Musto, P.; et al. The Tumor Microenvironment in Classic Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in Responder and No-Responder Patients to First Line ABVD Therapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Wierzbicki, K.; Sun, S.; Steidl, C.; Giulino-Roth, L. Tumor-microenvironment and molecular biology of classic Hodgkin lymphoma in children, adolescents, and young adults. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1515250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, LA; Kurman, CC; Fritz, ME; Biddison, WE; Boutin, B; Yarchoan, R; Nelson, DL. Soluble interleukin 2 receptors are released from activated human lymphoid cells in vitro. J Immunol 1985, 135(5), 3172–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, J; Arita, K; Wada, A; Mihara, H; Origasa, H; Kigawa, M; Yasuda, I; Sato, T. Serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels for screening for malignant lymphomas and differential diagnosis from other conditions. Mol Clin Oncol. 2019, 11(5), 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Allen, CE; Yu, X; Kozinetz, CA; McClain, KL. Highly elevated ferritin levels and the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008, 50(6), 1227–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, TF; Ferlic-Stark, LL; Allen, CE; Kozinetz, CA; McClain, KL. Rate of decline of ferritin in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a prognostic variable for mortality. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011, 56(1), 154–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aldinucci, D; Gloghini, A; Pinto, A; De Filippi, R; Carbone, A. The classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma microenvironment and its role in promoting tumour growth and immune escape. J Pathol 2010, 221(3), 248–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steidl, C; Connors, JM; Gascoyne, RD. Molecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: increasing evidence of the importance of the microenvironment. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29(14), 1812–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, DS; Yoon, HJ; Kim, WS; Ko, YH; Lee, H; Kim, CH. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is associated with the release of soluble IL-2 receptor alpha in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2010, 51(12), 2249–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Küppers, R. The biology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9(1), 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).