Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Studies

2.2. Fecal Sample Collection and DNA Isolation

2.3. 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

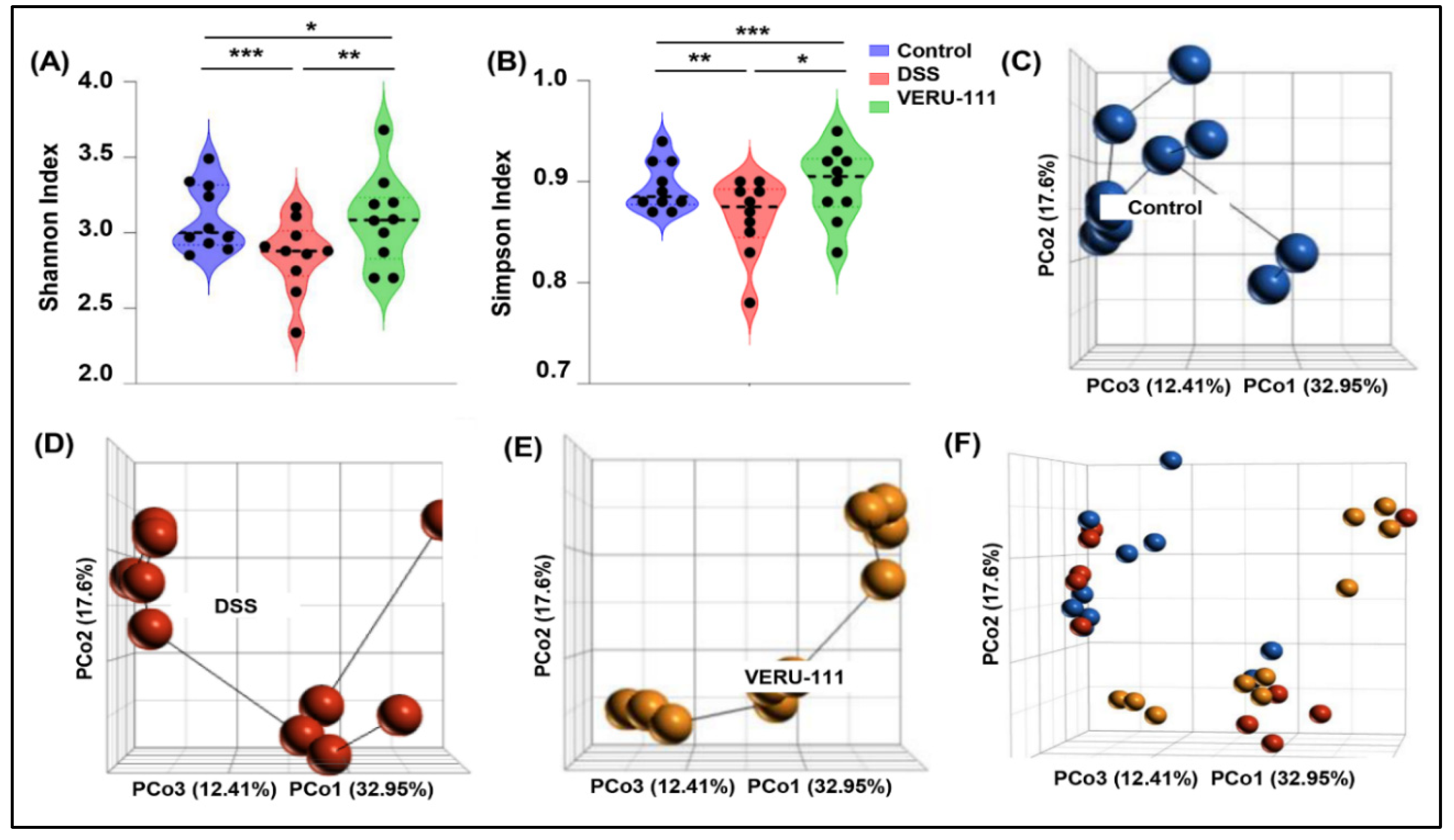

3.1. VERU-111 Treatment Reversed Overall Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis

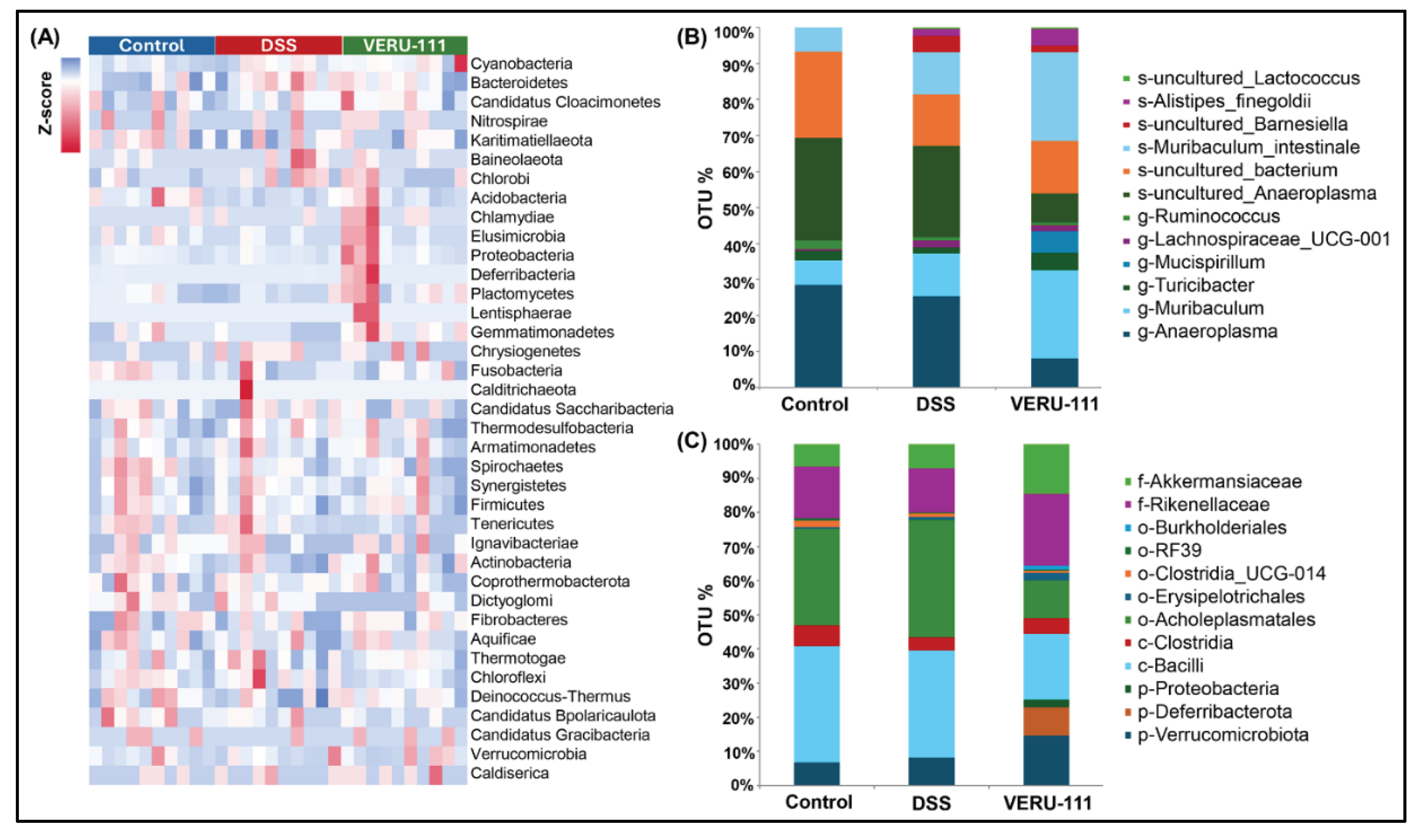

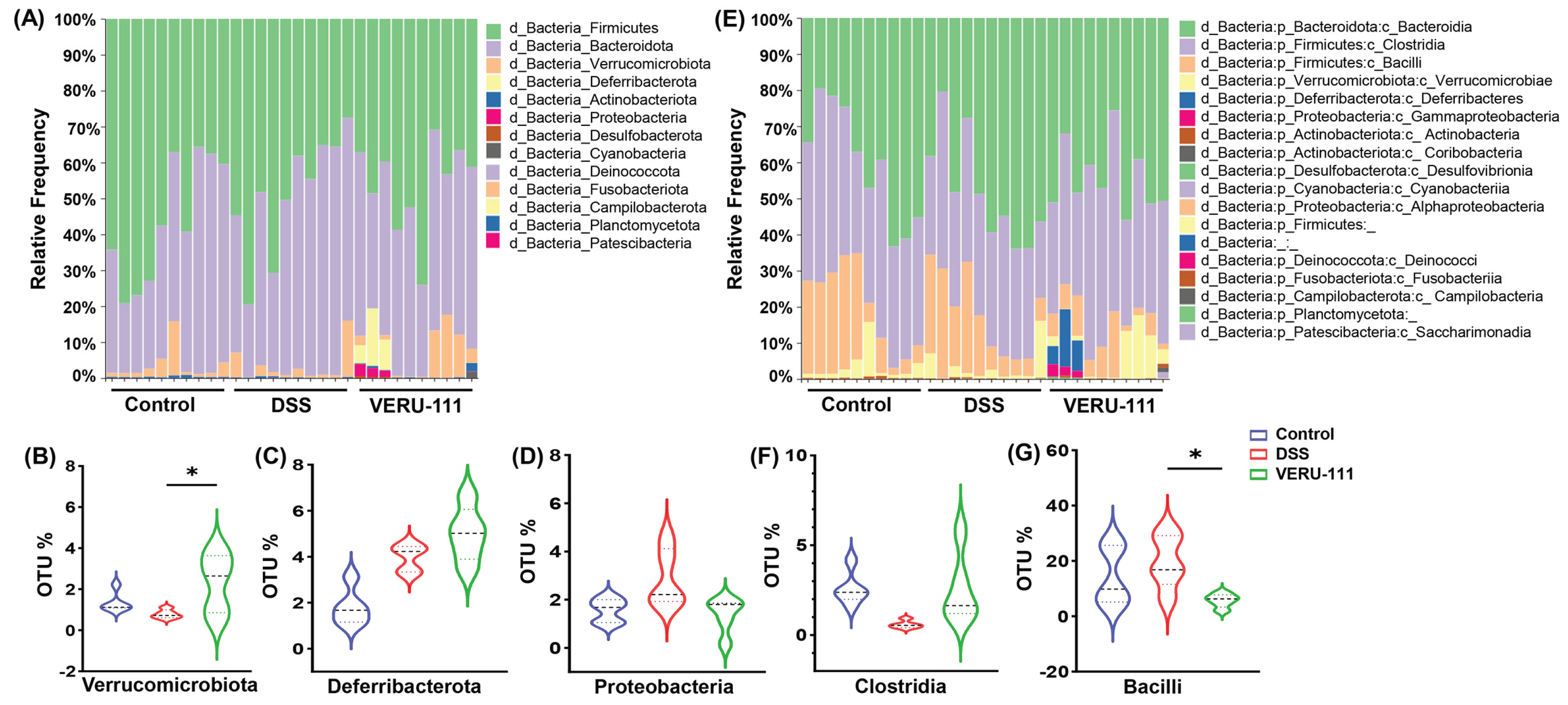

3.2. VERU-111 Modulated Gut Microbiota and Favored Beneficial Bacterial Phyla

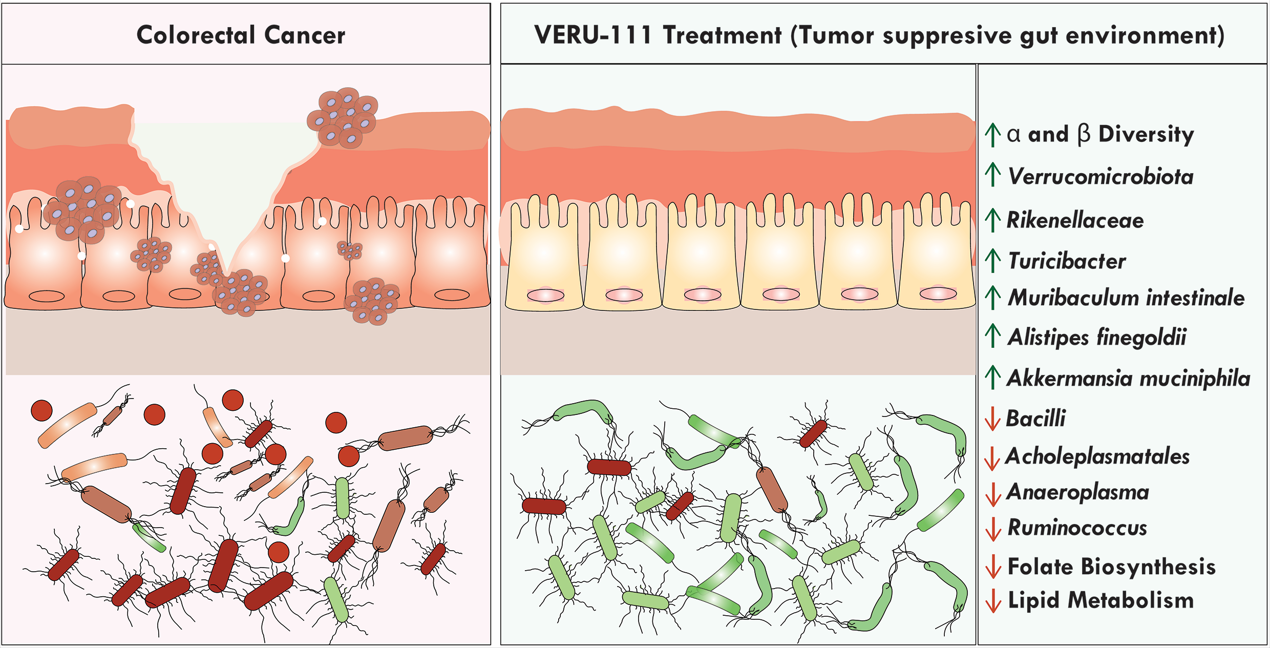

3.3. VERU-111 Enhanced the Abundance of Protective Bacteria and Created a Tumor-Suppressing Gut Environment

3.4. VERU-111 Improved the Abundance of Gut-Friendly Bacteria to Increase the Effectiveness of Chemotherapy

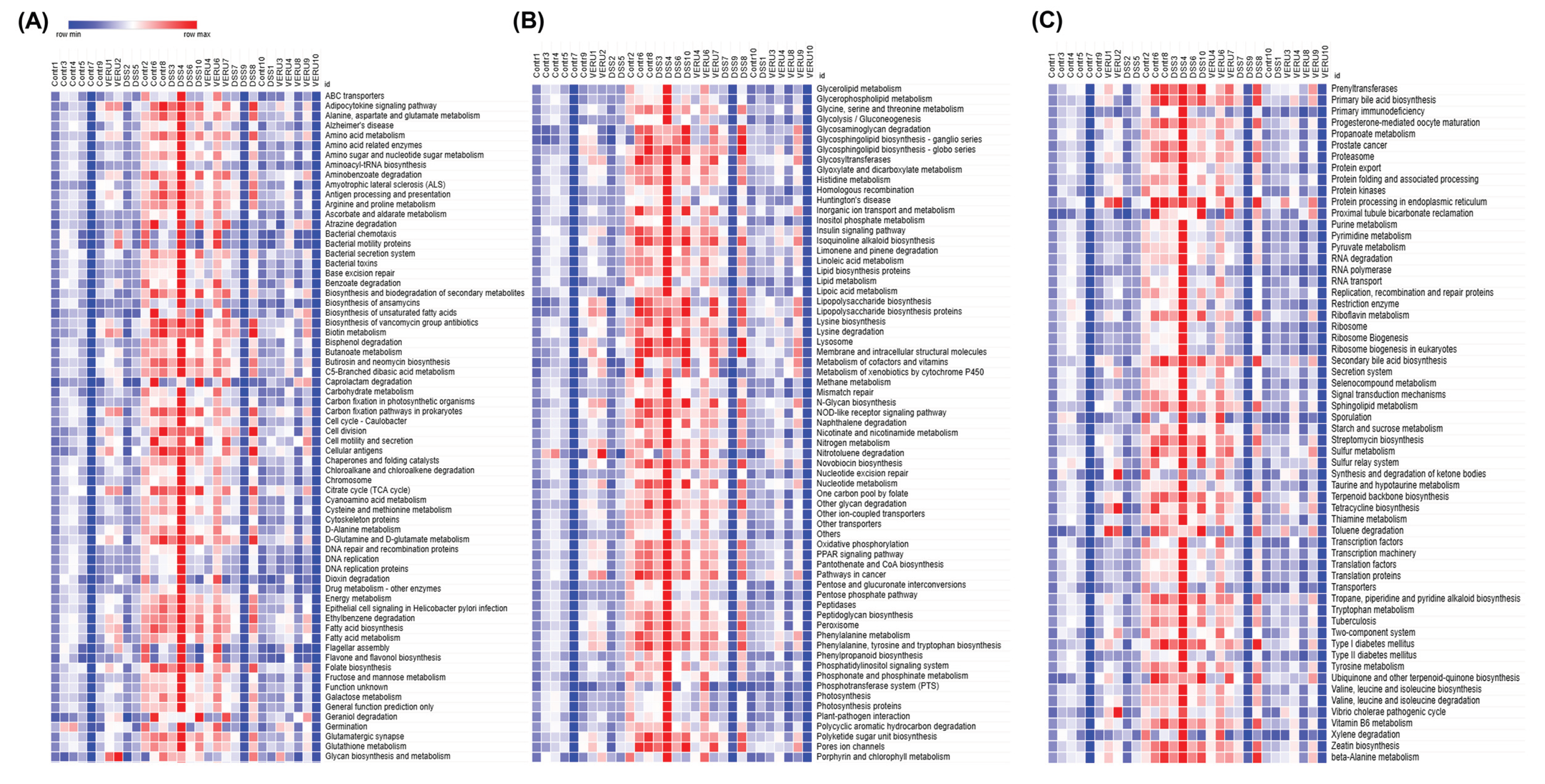

3.5. Prediction of Functional Capacity of Microbiome Through KEGG Pathway Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cahenzli, J.; Köller, Y.; Wyss, M.; Geuking, M.B.; McCoy, K.D. Intestinal microbial diversity during early-life colonization shapes long-term IgE levels. Cell host & microbe 2013, 14, 559-570. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.-Y.; Mei, J.-X.; Yu, G.; Lei, L.; Zhang, W.-H.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.-L.; Kołat, D.; Yang, K.; Hu, J.-K. Role of the gut microbiota in anticancer therapy: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 201. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell research 2020, 30, 492-506. [CrossRef]

- Sadrekarimi, H.; Gardanova, Z.R.; Bakhshesh, M.; Ebrahimzadeh, F.; Yaseri, A.F.; Thangavelu, L.; Hasanpoor, Z.; Zadeh, F.A.; Kahrizi, M.S. Emerging role of human microbiome in cancer development and response to therapy: special focus on intestinal microflora. Journal of translational medicine 2022, 20, 301. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Hu, Y. Microbiome harbored within tumors: a new chance to revisit our understanding of cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020, 5, 136.

- Wong-Rolle, A.; Wei, H.; Zhao, C.; Jin, C. Unexpected guests in the tumor microenvironment: microbiome in cancer. Protein Cell 12: 426–435. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2023, 20, 429-452. [CrossRef]

- Carding, S.; Verbeke, K.; Vipond, D.T.; Corfe, B.M.; Owen, L.J. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microbial ecology in health and disease 2015, 26, 26191.

- Rebersek, M. Gut microbiome and its role in colorectal cancer. BMC cancer 2021, 21, 1325. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.K. Potential role of the gut microbiome in colorectal cancer progression. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 12, 807648. [CrossRef]

- Iida, N.; Dzutsev, A.; Stewart, C.A.; Smith, L.; Bouladoux, N.; Weingarten, R.A.; Molina, D.A.; Salcedo, R.; Back, T.; Cramer, S. Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. science 2013, 342, 967-970.

- Geller, L.T.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Danino, T.; Jonas, O.H.; Shental, N.; Nejman, D.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Cooper, Z.A.; Shee, K. Potential role of intratumor bacteria in mediating tumor resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine. Science 2017, 357, 1156-1160.

- Flanagan, L.; Schmid, J.; Ebert, M.; Soucek, P.; Kunicka, T.; Liska, V.; Bruha, J.; Neary, P.; Dezeeuw, N.; Tommasino, M. Fusobacterium nucleatum associates with stages of colorectal neoplasia development, colorectal cancer and disease outcome. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases 2014, 33, 1381-1390. [CrossRef]

- Mima, K.; Nishihara, R.; Qian, Z.R.; Cao, Y.; Sukawa, Y.; Nowak, J.A.; Yang, J.; Dou, R.; Masugi, Y.; Song, M. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut 2016, 65, 1973-1980. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudian, F.; Gheshlagh, S.R.; Hemati, M.; Farhadi, S.; Eslami, M. The influence of microbiota on the efficacy and toxicity of immunotherapy in cancer treatment. Molecular Biology Reports 2025, 52, 86. [CrossRef]

- Said, S.S.; Ibrahim, W.N. Breaking barriers: the promise and challenges of immune checkpoint inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancer. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 369. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.N.; McQuade, J.L.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; McCulloch, J.A.; Vetizou, M.; Cogdill, A.P.; Khan, M.A.W.; Zhang, X.; White, M.G.; Peterson, C.B. Dietary fiber and probiotics influence the gut microbiome and melanoma immunotherapy response. Science 2021, 374, 1632-1640. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Cancer immunotherapy: harnessing the immune system to battle cancer. The Journal of clinical investigation 2015, 125, 3335-3337.

- André, T.; Shiu, K.-K.; Kim, T.W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Benavides, M.; Gibbs, P. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite-instability–high advanced colorectal cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 2207-2218.

- Chung, Y.; Ryu, Y.; An, B.C.; Yoon, Y.-S.; Choi, O.; Kim, T.Y.; Yoon, J.; Ahn, J.Y.; Park, H.J.; Kwon, S.-K. A synthetic probiotic engineered for colorectal cancer therapy modulates gut microbiota. Microbiome 2021, 9, 122. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Li, F.; Yang, R. The roles of gut microbiota metabolites in the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer: Multiple insights for potential clinical applications. Gastro Hep Advances 2024, 3, 855-870. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Li, R.; Pan, C.; Luo, C. Gut microbiota–derived metabolites in immunomodulation and gastrointestinal cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, 16, 1710880. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Arnst, K.E.; Wang, Y.; Kumar, G.; Ma, D.; Chen, H.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J.; White, S.W.; Miller, D.D. Structural modification of the 3, 4, 5-trimethoxyphenyl moiety in the tubulin inhibitor VERU-111 leads to improved antiproliferative activities. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2018, 61, 7877-7891.

- Kashyap, V.K.; Dan, N.; Chauhan, N.; Wang, Q.; Setua, S.; Nagesh, P.K.; Malik, S.; Batra, V.; Yallapu, M.M.; Miller, D.D. VERU-111 suppresses tumor growth and metastatic phenotypes of cervical cancer cells through the activation of p53 signaling pathway. Cancer letters 2020, 470, 64-74. [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Krutilina, R.I.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Parke, D.N.; Playa, H.C.; Chen, H.; Miller, D.D.; Seagroves, T.N.; Li, W. An orally available tubulin inhibitor, VERU-111, suppresses triple-negative breast cancer tumor growth and metastasis and bypasses taxane resistance. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2020, 19, 348-363. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, F.; Deng, S.; Chen, H.; Miller, D.D.; Li, W. Orally available tubulin inhibitor VERU-111 enhances antitumor efficacy in paclitaxel-resistant lung cancer. Cancer letters 2020, 495, 76-88.

- Krutilina, R.I.; Hartman, K.L.; Oluwalana, D.; Playa, H.C.; Parke, D.N.; Chen, H.; Miller, D.D.; Li, W.; Seagroves, T.N. Sabizabulin, a potent orally bioavailable colchicine binding site agent, suppresses HER2+ breast cancer and metastasis. Cancers 2022, 14, 5336. [CrossRef]

- Busbee, P.B.; Menzel, L.; Alrafas, H.R.; Dopkins, N.; Becker, W.; Miranda, K.; Tang, C.; Chatterjee, S.; Singh, U.P.; Nagarkatti, M. Indole-3-carbinol prevents colitis and associated microbial dysbiosis in an IL-22–dependent manner. JCI insight 2020, 5. [CrossRef]

- Nagalingam, N.A.; Kao, J.Y.; Young, V.B. Microbial ecology of the murine gut associated with the development of dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2011, 17, 917-926. [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome biology 2011, 12, R60. [CrossRef]

- Yachida, S.; Mizutani, S.; Shiroma, H.; Shiba, S.; Nakajima, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Watanabe, H.; Masuda, K.; Nishimoto, Y.; Kubo, M. Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses reveal distinct stage-specific phenotypes of the gut microbiota in colorectal cancer. Nature medicine 2019, 25, 968-976.

- Thomas, A.M.; Jesus, E.C.; Lopes, A.; Aguiar Jr, S.; Begnami, M.D.; Rocha, R.M.; Carpinetti, P.A.; Camargo, A.A.; Hoffmann, C.; Freitas, H.C. Tissue-associated bacterial alterations in rectal carcinoma patients revealed by 16S rRNA community profiling. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2016, 6, 179.

- Pongen, Y.L.; Thirumurugan, D.; Ramasubburayan, R.; Prakash, S. Harnessing actinobacteria potential for cancer prevention and treatment. Microbial Pathogenesis 2023, 183, 106324. [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.-K.; Kim, W.-S.; Paik, H.-D. Bacillus strains as human probiotics: characterization, safety, microbiome, and probiotic carrier. Food science and biotechnology 2019, 28, 1297-1305.

- Huycke, M.M.; Abrams, V.; Moore, D.R. Enterococcus faecalis produces extracellular superoxide and hydrogen peroxide that damages colonic epithelial cell DNA. Carcinogenesis 2002, 23, 529-536. [CrossRef]

- Gubernatorova, E.O.; Gorshkova, E.A.; Bondareva, M.A.; Podosokorskaya, O.A.; Sheynova, A.D.; Yakovleva, A.S.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A.; Nedospasov, S.A.; Kruglov, A.A.; Drutskaya, M.S. Akkermansia muciniphila-friend or foe in colorectal cancer? Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 1303795. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zou, S.; Xie, C.; Meng, Y.; Xu, X. Effect of the β-glucan from Lentinus edodes on colitis-associated colorectal cancer and gut microbiota. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 316, 121069.

- Lin, T.-C.; Soorneedi, A.; Guan, Y.; Tang, Y.; Shi, E.; Moore, M.D.; Liu, Z. Turicibacter fermentation enhances the inhibitory effects of Antrodia camphorata supplementation on tumorigenic serotonin and Wnt pathways and promotes ROS-mediated apoptosis of Caco-2 cells. Frontiers in pharmacology 2023, 14, 1203087.

- Gates, T.J.; Yuan, C.; Shetty, M.; Kaiser, T.; Nelson, A.C.; Chauhan, A.; Starr, T.K.; Staley, C.; Subramanian, S. Fecal microbiota restoration modulates the microbiome in inflammation-driven colorectal cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 2260.

- Li, L.; Lian, P.; Dong, W.; Song, S.; Wazir, J.; Wang, R.; Lin, K.; Pu, W.; Lu, R.; Yu, Z. Restoring Muribaculum intestinale–Derived Butyrate Mitigates Skeletal Muscle Loss in Cancer Cachexia. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 2025, 16, e70140. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-Y.; Wu, Q.-W.; Han, Y.; Xiang, S.-J.; Wang, Y.-N.; Wu, W.-W.; Chen, Y.-X.; Feng, Z.-Q.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Xu, Z.-G. Alistipes finegoldii augments the efficacy of immunotherapy against solid tumors. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 1714-1730. e1712. [CrossRef]

- Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D.; Petitfils, C.; De Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; El-Omar, E.M. What defines a healthy gut microbiome? Gut 2024, 73, 1893-1908. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cho, W.C.; Nicolls, M.R. Colorectal cancer-associated microbiome patterns and signatures. Frontiers in Genetics 2021, 12, 787176.

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Marano, L.; Merola, E.; Roviello, F.; Połom, K. Sodium butyrate in both prevention and supportive treatment of colorectal cancer. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2022, 12, 1023806. [CrossRef]

- Byrd, D.A.; Damerell, V.; Gomez Morales, M.F.; Hogue, S.R.; Lin, T.; Ose, J.; Himbert, C.; Ilozumba, M.N.; Kahlert, C.; Shibata, D. The gut microbiome is associated with disease-free survival in stage I–III colorectal cancer patients. International Journal of Cancer 2025, 157, 64-73.

- Belzer, C.; Chia, L.W.; Aalvink, S.; Chamlagain, B.; Piironen, V.; Knol, J.; de Vos, W.M. Microbial metabolic networks at the mucus layer lead to diet-independent butyrate and vitamin B12 production by intestinal symbionts. MBio 2017, 8, 10.1128/mbio. 00770-00717.

- Hosomi, K.; Saito, M.; Park, J.; Murakami, H.; Shibata, N.; Ando, M.; Nagatake, T.; Konishi, K.; Ohno, H.; Tanisawa, K. Oral administration of Blautia wexlerae ameliorates obesity and type 2 diabetes via metabolic remodeling of the gut microbiota. Nature communications 2022, 13, 4477. [CrossRef]

- Yixia, Y.; Sripetchwandee, J.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. The alterations of microbiota and pathological conditions in the gut of patients with colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Anaerobe 2021, 68, 102361. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Weng, W.; Guo, B.; Cai, G.; Ma, Y.; Cai, S. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil by upregulation of BIRC3 expression in colorectal cancer. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 38, 14.

- Hou, X.; Zhang, P.; Du, H.; Chu, W.; Sun, R.; Qin, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, F. Akkermansia muciniphila potentiates the antitumor efficacy of FOLFOX in colon cancer. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 725583.

- Zhang, M.; Wei, Z.; Wei, B.; Lai, C.; Zong, G.; Tao, E.; Fan, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, B.; Shen, L. Microbiota-derived urocanic acid triggered by tyrosine kinase inhibitors potentiates cancer immunotherapy efficacy. Cell Host & Microbe 2025, 33, 915-931. e919. [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Zhou, K.; Lei, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, H. Gut microbiota shapes cancer immunotherapy responses. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2025, 11, 143. [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J.B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z.M.; Benyamin, F.W.; Man Lei, Y.; Jabri, B.; Alegre, M.-L. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti–PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015, 350, 1084-1089.

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; Prieto, P.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti–PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 97-103.

- Chaput, N.; Lepage, P.; Coutzac, C.; Soularue, E.; Le Roux, K.; Monot, C.; Boselli, L.; Routier, E.; Cassard, L.; Collins, M. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Annals of Oncology 2017, 28, 1368-1379.

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, D.; Jiang, W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, P.; Song, R. Gut microbiome affects the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2019, 7, 193. [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Isobe, J.; Hattori, K.; Hosonuma, M.; Baba, Y.; Murayama, M.; Narikawa, Y.; Toyoda, H.; Funayama, E.; Tajima, K. Turicibacter and Acidaminococcus predict immune-related adverse events and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor. Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 1164724.

- Davar, D.; Dzutsev, A.K.; McCulloch, J.A.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Chauvin, J.-M.; Morrison, R.M.; Deblasio, R.N.; Menna, C.; Ding, Q.; Pagliano, O. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti–PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science 2021, 371, 595-602.

- Chen, Y.; Jia, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, J. Predicting response to immunotherapy in gastric cancer via multi-dimensional analyses of the tumour immune microenvironment. Nature communications 2022, 13, 4851. [CrossRef]

- Fridman, W.H.; Pagès, F.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Galon, J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nature Reviews Cancer 2012, 12, 298-306. [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S.; Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Gajewski, T.F. Tumor and host factors controlling antitumor immunity and efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Advances in immunology 2016, 130, 75-93.

- Cremonesi, E.; Governa, V.; Garzon, J.F.G.; Mele, V.; Amicarella, F.; Muraro, M.G.; Trella, E.; Galati-Fournier, V.; Oertli, D.; Däster, S.R. Gut microbiota modulate T cell trafficking into human colorectal cancer. Gut 2018, 67, 1984-1994. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Hugerth, L.W.; Hases, L.; Saxena, A.; Seifert, M.; Thomas, Q.; Gustafsson, J.Å.; Engstrand, L.; Williams, C. Colitis-induced colorectal cancer and intestinal epithelial estrogen receptor beta impact gut microbiota diversity. International journal of cancer 2019, 144, 3086-3098. [CrossRef]

- Di Modica, M.; Gargari, G.; Regondi, V.; Bonizzi, A.; Arioli, S.; Belmonte, B.; De Cecco, L.; Fasano, E.; Bianchi, F.; Bertolotti, A. Gut microbiota condition the therapeutic efficacy of trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Research 2021, 81, 2195-2206.

- Yang, W.; Cong, Y. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites in the regulation of host immune responses and immune-related inflammatory diseases. Cellular & molecular immunology 2021, 18, 866-877. [CrossRef]

- Trompette, A.; Gollwitzer, E.S.; Pattaroni, C.; Lopez-Mejia, I.C.; Riva, E.; Pernot, J.; Ubags, N.; Fajas, L.; Nicod, L.P.; Marsland, B.J. Dietary fiber confers protection against flu by shaping Ly6c− patrolling monocyte hematopoiesis and CD8+ T cell metabolism. Immunity 2018, 48, 992-1005. e1008.

- Vogel, F.C.; Chaves-Filho, A.B.; Schulze, A. Lipids as mediators of cancer progression and metastasis. Nature cancer 2024, 5, 16-29.

- Wang, W.; Bai, L.; Li, W.; Cui, J. The lipid metabolic landscape of cancers and new therapeutic perspectives. Frontiers in oncology 2020, 10, 605154.

- Zhu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zheng, Y.; Yao, Y.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, D.-D.; Zhang, J. Folate metabolism-associated CYP26A1 is a clinico-immune target in colorectal cancer. Genes & Immunity 2025, 1-18. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).