1. Introduction

Today, with industrialisation firmly embedded in modern societies, global plastic production has reached approximately 413.8 million metric tonnes per year, resulting in a growing environmental crisis associated with plastic waste mismanagement [

1]. An estimated 23 million tonnes of plastics enter aquatic environments annually through maritime activities, urban runoff and inadequate waste management practices. Due to their resistance to biodegradation, plastics progressively fragment into microplastics—synthetic hydrocarbon particles smaller than 5 mm—which persist in marine and freshwater systems and accumulate across environmental compartments [

2,

3]. These particles can act as vectors for toxic contaminants and are associated with ecological and human health concerns, including biochemical interactions and disruptions in organisms and humans [

4,

5].

While a substantial body of literature addresses the environmental fate, transport and ecological impacts of microplastics, the present study does not investigate natural processes such as environmental uptake, sequestration or degradation. Instead, it focuses exclusively on the environmental performance of laboratory-based analytical workflows required for the quantification of microplastics in environmental matrices.

Seagrass meadows and marine macroalgae are frequently described as temporary sinks for microplastics due to their structural complexity, reduced hydrodynamic flow and biofilm development. In seagrass ecosystems, dense leaf canopies slow water movement and promote sedimentation, resulting in elevated microplastic concentrations in sediments compared to adjacent non-vegetated areas [

6,

7,

8]. Similarly, marine macroalgae species, particularly filamentous species, exhibit high microplastic retention capacity through adhesion and physical entanglement, often reaching concentrations substantially higher than those observed in surrounding seawater [

9,

10].

The retention of microplastics by marine vegetation is influenced by physical trapping, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) secretion and biofilm development, which can enhance particle aggregation and sedimentation [

11,

12]. Biofilms associated with microplastics consist of diverse microbial communities embedded in an EPS matrix, facilitating adhesion on plastic surfaces and contributing to their vertical transport in marine environments [

10,

12]. Although these microbial interactions can alter microplastic properties and, under specific conditions, initiate partial degradation pathways, most synthetic polymers remain highly persistent in aquatic systems.

Despite the ecological relevance of these natural retention mechanisms, their investigation relies on complex laboratory workflows involving sample collection, pre-treatment, chemical digestion, density separation and instrumental detection. These analytical procedures typically require the use of energy-intensive equipment, chemical reagents and consumables, generating secondary waste streams whose environmental implications are rarely considered beyond analytical performance metrics.

To date, most studies comparing microplastics quantification methods focus on recovery rates, detection limits and reproducibility, while the environmental burdens associated with alternative analytical workflows remain largely unexplored. This lack of methodological assessment limits the ability to select analytical approaches that are not only robust and reproducible, but also environmentally efficient, particularly as microplastics monitoring expands in scope and frequency.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has been extensively applied to evaluate energy-intensive process systems, demonstrating their suitability for comparing alternative configurations and identifying environmental hotspots driven by energy consumption. Such applications underscore the relevance of LCA for analysing laboratory-based workflows, where electricity demand and processing duration can dominate environmental impact profiles [

13]. By applying LCA to microplastics quantification methods, this study addresses a methodological gap by comparing the environmental performance of alternative laboratory workflows under controlled conditions, without assessing natural microplastics absorption, transport or fate processes. The results aim to support more sustainable decision-making in analytical method selection and laboratory practice. Previous process-based environmental assessments have demonstrated the applicability of LCA to complex systems characterised by multiple operational stages and heterogeneous inputs. These studies provide a methodological precedent for applying LCA beyond conventional industrial systems, extending its use to analytical and laboratory-scale processes that require systematic comparison of alternative scenarios [

14]. From a broader sustainability perspective, LCA has been increasingly used as a decision-support tool to inform environmentally responsible practices within the context of circular economy strategies. Incorporating LCA into the evaluation of analytical and monitoring activities allows environmental impacts to be considered alongside data quality and scientific reliability, supporting the development of more sustainable approaches to environmental monitoring and assessment [

15].

Thus, the objective of this study was to quantify the environmental impacts associated with laboratory-based microplastic analysis in two contrasting marine vegetated matrices—pelagic algae and seagrass—using a gate-to-gate LCA. By evaluating digestion, filtration, concentration and analytical detection as interconnected subsystems, this work aims to provide the first systematic assessment of the environmental performance of microplastic quantification workflows and to identify matrix-specific drivers influencing their life cycle burdens. The system boundaries are strictly limited to laboratory operations and analytical inputs, excluding environmental microplastics dynamics or natural absorption processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Goal and Scope

The objective of the LCA was to determine the environmental impact of quantifying the microplastic absorption process of biofilms in two aquatic ecosystems: Scenario 1. Seagrass beds; and Scenario 2. Sargassum. The methodological design of this study is informed by recent critical analyses of LCA applications, which highlight functional unit definition, system boundary selection and impact category choice as major sources of uncertainty, particularly in laboratory-scale and process-oriented assessments. To ensure methodological consistency and transparency, a gate-to-gate approach was therefore adopted, focusing exclusively on the technosphere processes associated with microplastic quantification while excluding natural processes beyond direct human control [

16]. The functional unit for this analysis was 1 kg of biomass (sargassum or seagrass) that has the capacity to absorb microplastics.

2.1.1. Limitations

Several limitations inherent to the scope and methodological design of this LCA must be acknowledged.

The study adopts a gate-to-gate approach focused exclusively on the processes associated with quantifying microplastic retention by biofilms. As recommended by the ILCD Handbook, such a restricted boundary may omit upstream or downstream environmental burdens that could be relevant in a broader assessment [

17]. Consequently, the results should not be interpreted as the total environmental impact of microplastic pollution, nor as the environmental performance of the ecosystems studied, but solely as the impact of the analytical quantification process.

The natural process of microplastic absorption by seagrass meadows and sargassum is not modelled in terms of environmental impact, as it is an uncontrolled and non-anthropogenic phenomenon. Only the mass of microplastics retained—used as the functional output—is considered. According to ISO 14040 and ISO 14044, excluding biological processes beyond human control is acceptable when they are not part of the technosphere; however, this introduces uncertainty regarding comparability across different environmental conditions [

18,

19].

The quantification of microplastics depends on laboratory methods that may vary in recovery efficiency, detection limits, analytical sensitivity, and accuracy. Studies have shown that FTIR and Raman spectroscopy may under-detect small particles (<20 µm), while digestion protocols can partially degrade certain polymers, leading to underestimation (e.g., [

20,

21]). Although standard quality-control measures (blanks, replicates, calibration) reduce these uncertainties, they cannot be eliminated.

Data availability for some inventory flows—particularly energy consumption of analytical equipment and specific emission factors for laboratory reagents—may require the use of secondary datasets. As emphasised by the ILCD data quality guidelines, reliance on secondary data introduces uncertainty related to technological, geographical, and temporal representativeness [

17]. Sensitivity analysis is recommended to evaluate the robustness of results to these uncertainties.

The study does not include a cradle-to-grave assessment of the microplastics themselves. Their production, release into the ocean, environmental transport, fragmentation, and fate are excluded. Reviews on LCA of plastics and microplastic pollution highlight that excluding life-cycle emissions of polymers prevents capturing the full environmental burden associated with the presence of microplastics in marine environments [

22]. This limitation is consistent with the study’s objective but restricts interpretability.

The spatial and temporal representativeness is constrained to the sampling locations and experimental conditions selected. Microplastic concentrations, hydrodynamics, biofilm structure, and vegetation density can vary substantially across regions and seasons [

23]. Therefore, extrapolation of the results to other ecosystems should be performed with caution.

2.1.2. System Boundary

The system includes the processes of sampling and collection of biomass in the field, transport of samples to the laboratory, preparation and separation of the biofilm, chemical digestion when applicable, filtration, concentration, drying or preservation, analytical analysis (FTIR, µ-FTIR/Raman, microscopy), data recording, as well as the handling of reagents, waste, and consumables. Energy consumption is also considered associated with drying, filtration, and analysis, as well as material inputs (filters, membranes, reagents, containers).

The production of the vegetation (seagrass or sargassum), its natural cycle in the ecosystem, the original production of microplastics, their previous use in the marine environment, and subsequent management stages (use, final disposal outside the laboratory) are intentionally excluded, except for the immediate treatment of waste generated during the analysis. The “cradle-to-grave” phase of the microplastic as a pollutant is also not included, given that the objective is the quantification of retention.

The spatial boundary is limited to the coordinates and conditions of the sampling sites defined for each scenario (vegetation density, hydrodynamics, depth, etc.). The temporal horizon considers the time of sampling, transport, processing, and analysis. If the environmental fate of the retained microplastics is estimated (sedimentation, remobilisation, etc.), the fate horizon and the associated assumptions must be clearly defined. The input flows considered include reagents, energy, sampling and filtration materials. The outputs are solid and liquid laboratory waste, retained microplastics, possible remobilised ones, and emissions or discharges derived from the use of energy or reagents.

2.2. LCA Inventory

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the inventories considered for both scenarios. These inventories were taken from various sources and were used to determine the environmental impact of quantifying the microplastics retained by these two biomasses.

The equipment considered for those scenarios were: Drying oven Stereomicroscope FT-IR Spectrometer, Incubator/Shaker, Filtration, and Microscopy.

2.3. LCA Assessment

The LCA was carried out using the open-source software openLCA v2.5 [

26], following the ISO 14040/14044 framework for impact assessment characterisation, normalisation, and interpretation [

18,

19]. All foreground inventory data derived from the sampling, preparation, digestion, filtration, and analytical quantification stages were modelled as independent processes within openLCA, while background data—such as electricity supply, chemical production, transport, and waste treatment—were sourced from the

OzLCI2019 data base combined with

elcd_3_2_greendata_v2_18_correction_20220908 and

USDA_1901009 databases. Impact characterisation was performed using the ReCiPe Midpoint (H) V1.13 method, selected due to its comprehensive coverage of environmental impact categories relevant to laboratory-intensive processes, including climate change, freshwater ecotoxicity, human toxicity, and resource use [

27]. All characterisation factors were applied as provided in the original method without modification. Data quality assessment followed ILCD recommendations for representativeness, completeness, and methodological appropriateness [

17]. Sensitivity analysis was conducted for key parameters (electricity use, reagent consumption, filtration efficiency) to evaluate the robustness of results and to account for uncertainty inherent in laboratory-scale microplastic quantification. The overall LCIA results represent the environmental impacts associated exclusively with the technosphere processes required to quantify one gram of microplastic retained by biofilm, in accordance with the defined goal, scope, and system boundary of this study.

2.4. LCA Interpretation

The interpretation of results will be conducted following the methodological requirements established in ISO 14040 and ISO 14044, ensuring that the findings are consistent with the goal and scope of the study and that conclusions are technically justified and transparent [

18,

19]. The interpretation will comprise four structured components: (i) identification of significant issues, (ii) evaluation, (iii) consistency and completeness checks, and (iv) conclusions and recommendations.

Significant issues will be identified by examining the relative contributions of each process within the technosphere—such as digestion, filtration, and analytical procedures—to the midpoint impact categories assessed. Contribution analysis, normalised results, and hotspot identification will be used to determine which processes dominate the environmental burden. This step follows internationally recognised interpretation practices as outlined in the ILCD Handbook [

17].

An evaluation step will be performed, including a completeness check, sensitivity analysis, and uncertainty assessment. Completeness checks will verify that all relevant foreground and background processes defined in the system boundary were included. Sensitivity analysis will assess the influence of key parameters such as electricity consumption, reagent use, and microplastic recovery rates on overall impact results. Parameters showing high sensitivity will be highlighted as potential contributors to uncertainty. Where applicable, uncertainty will be addressed by comparing variations across alternative datasets (e.g., electricity mixes) and by examining methodological choices, following guidelines from ILCD and recent literature on analytical variability in microplastic quantification [

20]. Then, a consistency check will ensure that assumptions, data sources, allocation rules, and characterisation methods have been applied uniformly across scenarios and system processes. This assessment will verify that modelling decisions in openLCA—such as database selection, impact method, and process connections—align with the goal and scope, maintaining methodological coherence throughout the study.

Conclusions and recommendations will be formulated based on identified hotspots and sensitivity outcomes, focusing on opportunities to reduce environmental burdens within laboratory protocols and supporting best practices for microplastic quantification. All interpretation findings will explicitly reflect the uncertainties and constraints identified during the evaluation process, in accordance with ISO standards and ILCD guidance. The impact categories evaluated can be seen in

Table 3.

It should be noted that, for some impact categories such as marine ecotoxicity (METPinf), negative values may arise due to the modelling approach adopted. These values result from the application of an avoided burden perspective; whereby environmental credits are assigned when upstream processes—such as the production of chemical reagents or the management of hazardous laboratory waste—are partially substituted or avoided within the analytical workflows. Such credits reflect impacts avoided in the background system and do not represent direct environmental benefits occurring during laboratory operations.

3. Results

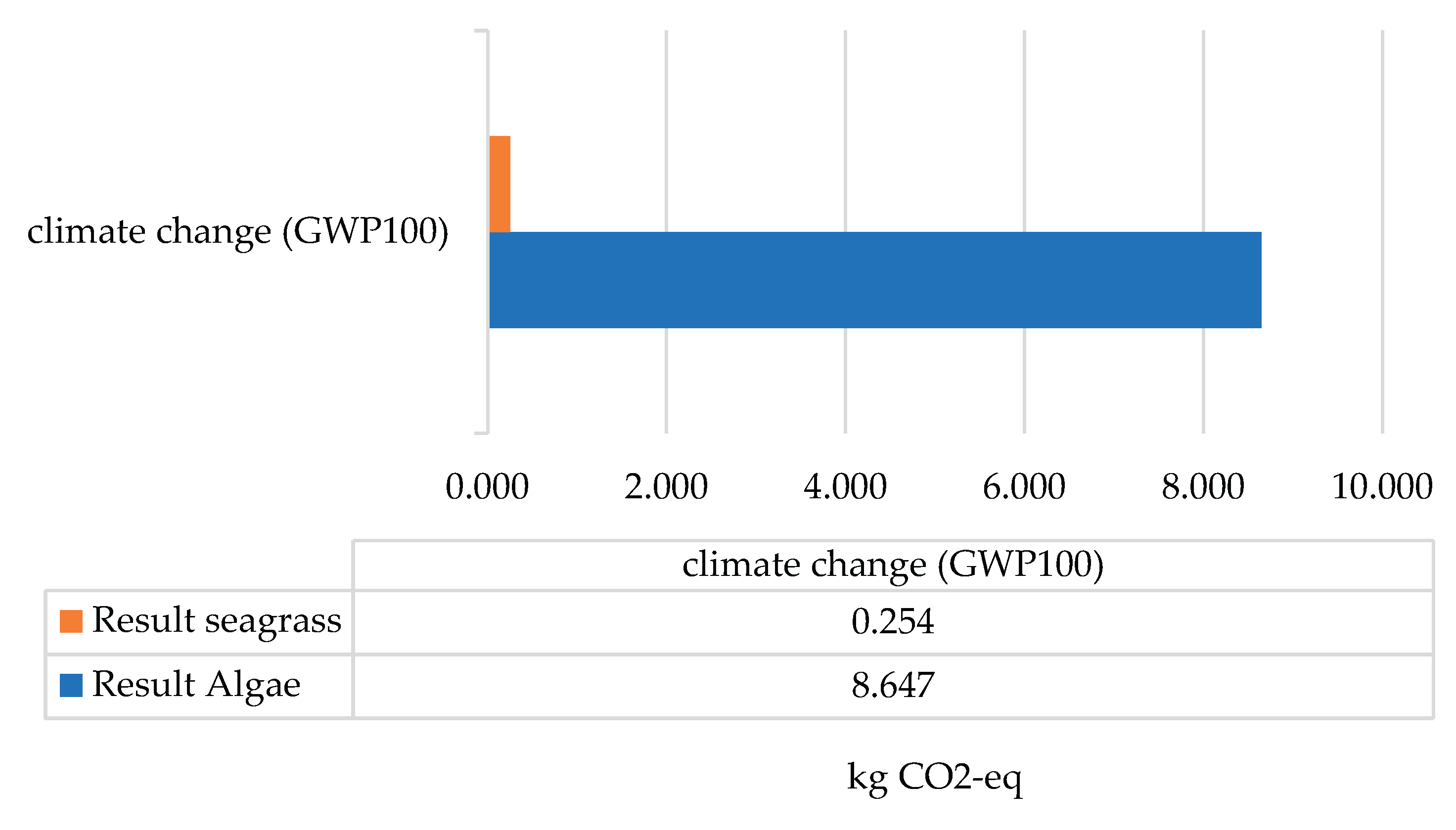

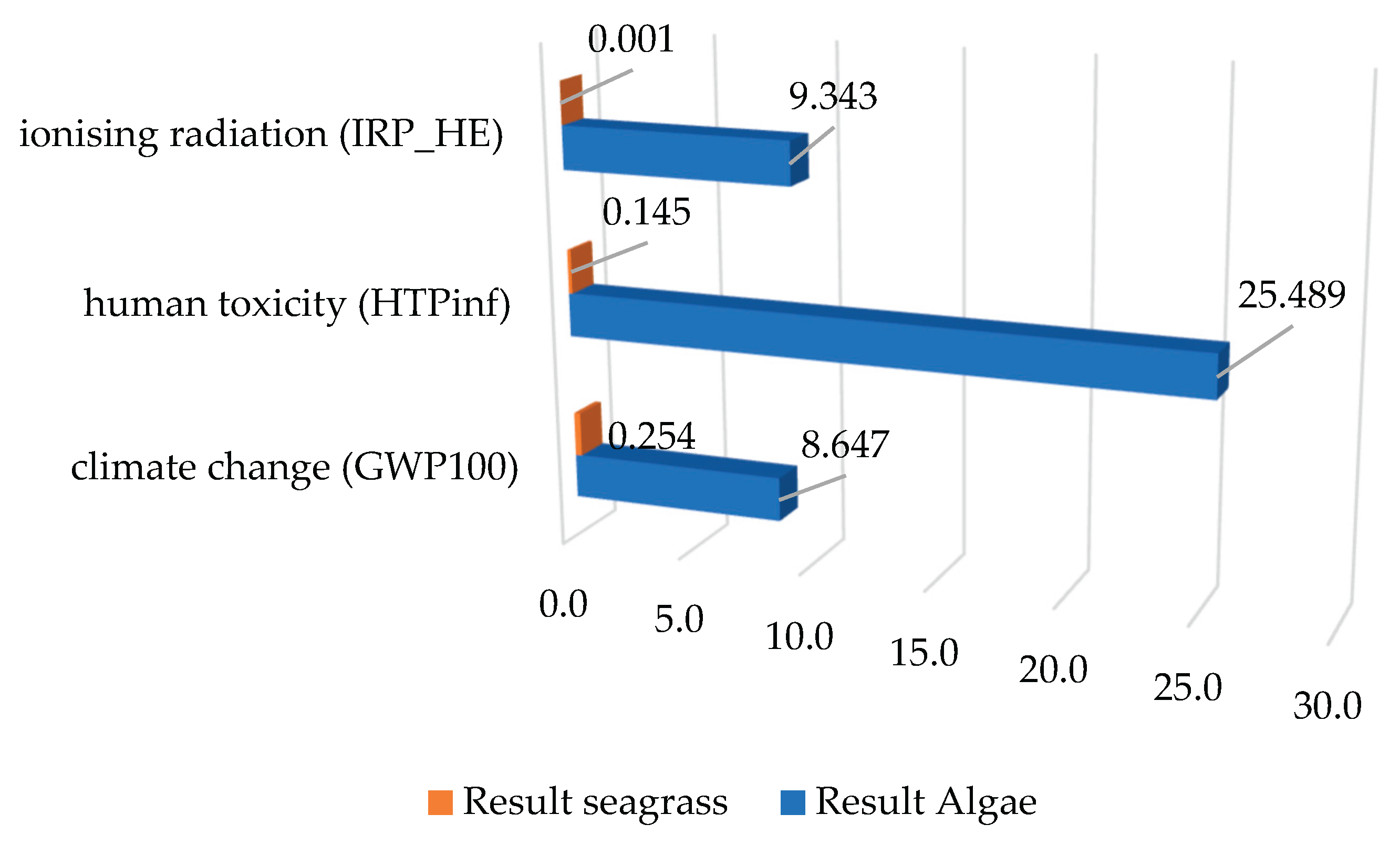

In both scenarios, as biomass represents natural carbon reservoirs and seagrass represents microplastic reservoirs, both cases are related to the climate change category. When evaluating this impact category, focusing on the laboratory process and performing a comparative analysis between the scenarios, scenario 2, with 8.65 kg CO

2-Eq had a greater impact than scenario 1 with 0.25 kg CO

2-Eq, as shown in

Figure 1. This relationship is directly proportional to energy consumption in both scenarios, since scenario 2 has higher consumption, as the shaker was used for around 52 h continuously, the impact is greater.

To analyse the assessment of the different impact categories in relation to natural resources, the different categories were classified into three main groups: water impacts, soil impacts, and air impacts.

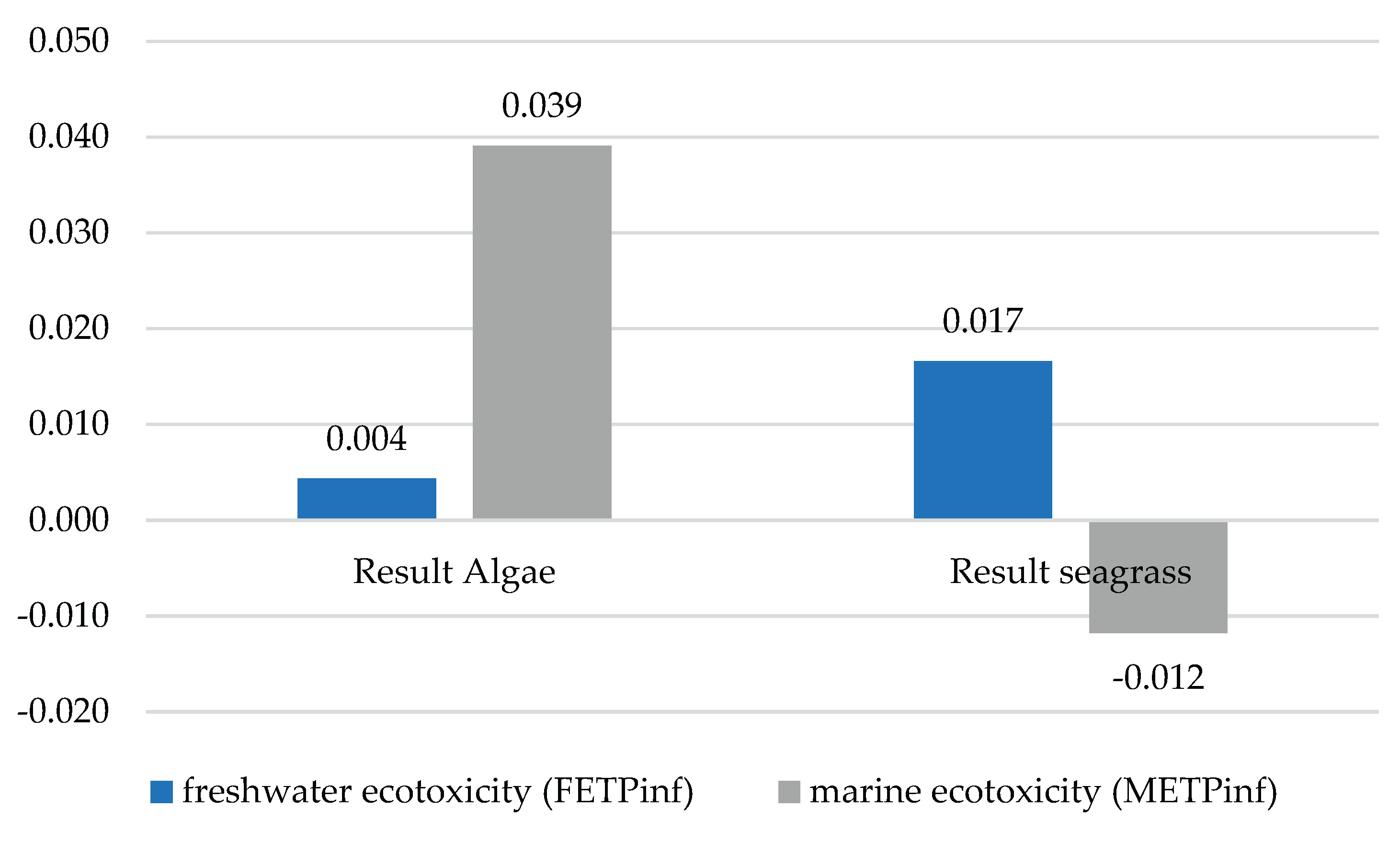

3.1. Water Impacts

The impact categories classified in this group were FETPinf and METPinf. It was evident that in the case of FETPinf, scenario 2 was higher than scenario 1. METPinf showed different behaviour, as scenario 1 had an environmental credit or avoided impact load. This behaviour may indicate that there is a subprocess that has reduced pollution in a system, as shown in

Figure 2. The negative values obtained for METPinf should therefore be interpreted as relative environmental credits rather than net environmental benefits. They reflect the avoidance of marine ecotoxicity impacts associated with upstream chemical production or waste management processes, and do not imply a direct reduction of marine pollution during the analytical procedures themselves.

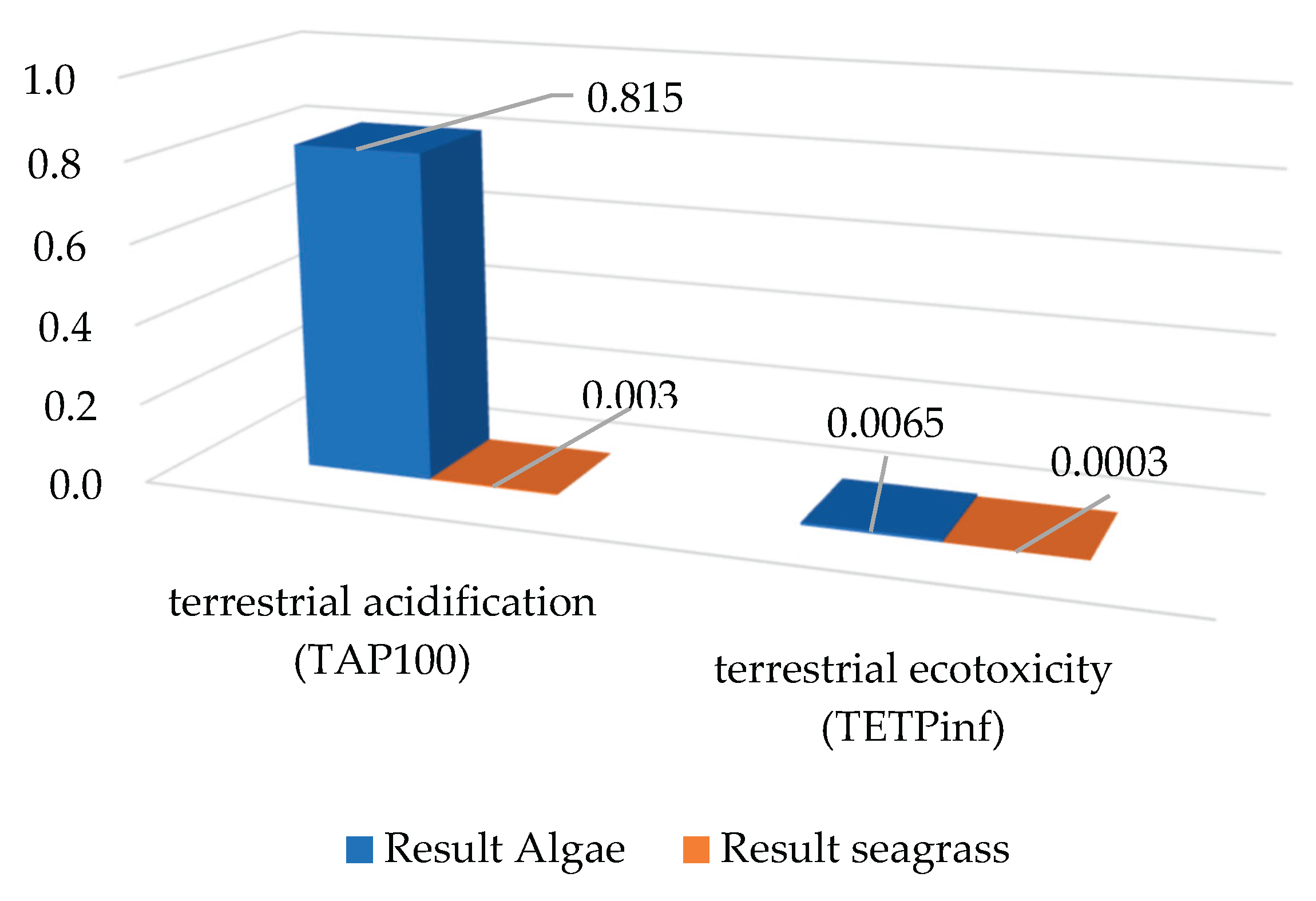

3.2. Soil Impacts

When evaluating terrestrial ecotoxicity (TETPinf) and terrestrial acidification (TAP100), the trend of greater intensity in the treatment of sargassum in scenario 2 is confirmed (see

Figure 3). Furthermore, regarding TETPinf, scenario 2 is significantly higher than scenario 1. In TAP100, scenario 2 also has a significantly higher value than scenario 1.

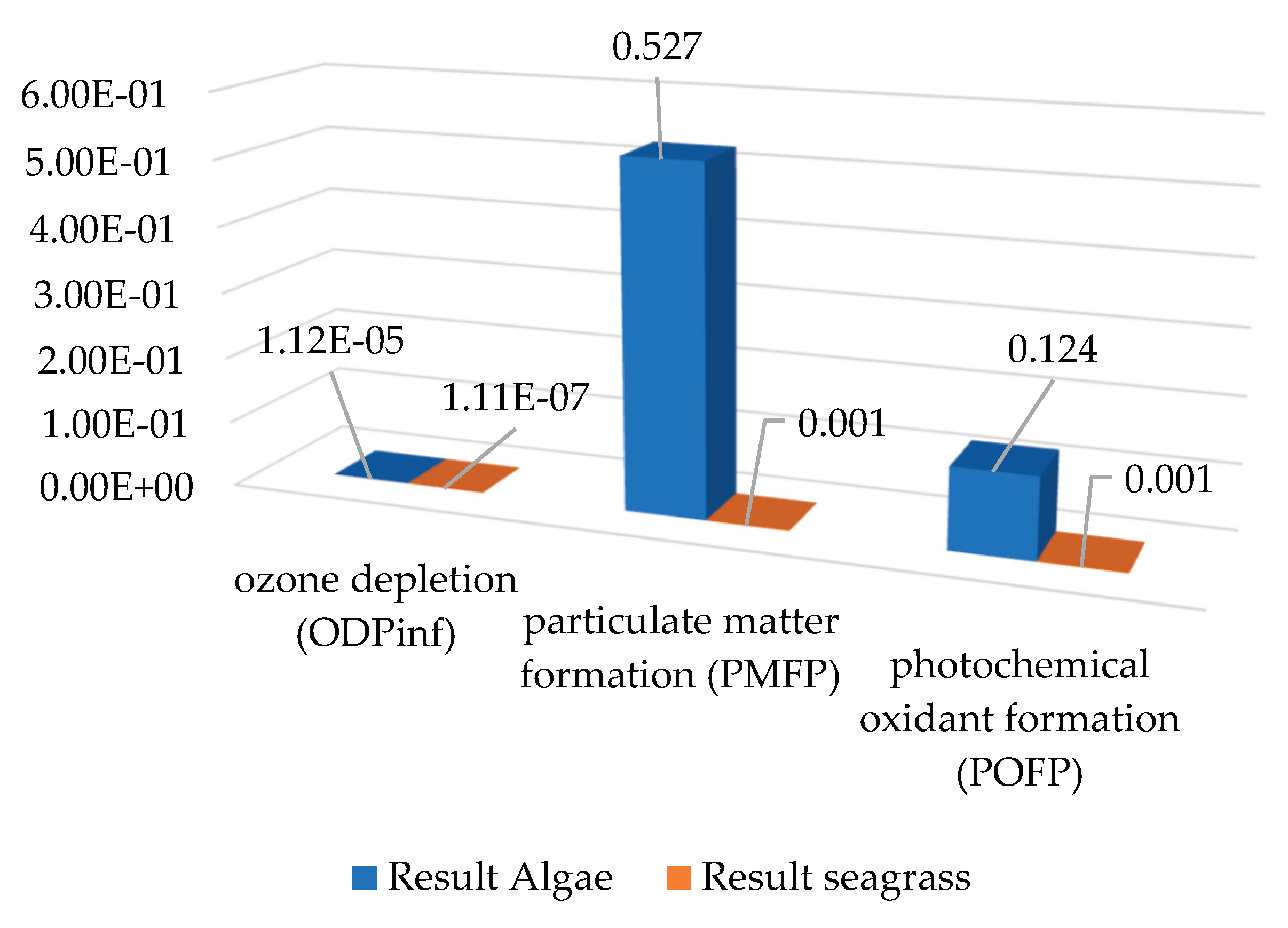

3.3. Air Impacts

The air-related impact categories include photochemical oxidant formation (POFP), particulate matter formation (PMFP) and ozone depletion (ODPinf). Regarding ODPinf, very low values close to zero are evident in both scenarios, with scenario 2 being higher than scenario 1 (see

Figure 4). In terms of PMFP and POFP, scenario 2 has a greater impact than scenario 1. This may be due to the burning of fossil fuels for energy generation or transport of supplies.

3.4. Other impact Categories

On the other hand, within the other impact categories, it was found that these categories have a similar trend, as shown in

Figure 5. Here, in the case of IRP, scenario 2 accounts for a higher impact than scenario 1. The same behaviour was evidenced for HTPinf, although the magnitudes were greater.

4. Discussion

Methodological uncertainties observed in this study are consistent with challenges reported in recent critical reviews of LCA applications to complex environmental systems. In particular, the definition of the functional unit, the selection of background databases and the allocation of energy-intensive laboratory processes can significantly influence the magnitude and distribution of impact categories [

16]. Acknowledging these sources of uncertainty is essential for a transparent interpretation of results and for ensuring comparability across LCA studies addressing analytical workflows. The substantial differences observed between the algae and seagrass scenarios across multiple impact categories reflect the interplay between analytical method intensity and ecosystem matrix complexity rather than fundamental ecological differences alone. Several lines of evidence from the microplastic and life cycle literature support this interpretation.

Laboratory workflows that involve energy-intensive instruments such as FTIR spectrometers, ovens for drying and prolonged filtration steps can contribute substantially to energy use and related environmental impacts in analytical procedures. Although few life cycle assessments focus specifically on microplastic quantification, reviews of analytical methods note that energy consumption from instrument operation and solvent production are important contributors to the overall environmental profile of analytical chemistry workflows [

28].

Methodological reviews underscore the high variability in extraction and detection protocols for microplastics, noting that the choice of reagents, digestion methods, and analytical detection (FTIR, Raman, microscopy) can lead to significant differences in recovery rates and resource requirements [

20]. This heterogeneity in protocols can translate into differing life cycle burdens even when addressing the same environmental sample. For example, aggressive oxidative digestion, often necessary to remove organic matrices from algal samples, requires greater energy input and chemical usage, which elevates impacts in categories such as human toxicity and freshwater ecotoxicity. Indeed, chemical reagents and their upstream production pathways contribute substantially to toxicity-related indicators when included in life cycle inventories.

The physical and biological characteristics of sample matrices further influence analytical intensity. Marine macroalgae and pelagic biomass such as sargassum often contain high organic loads and complex biofilms, making it more challenging to liberate bound microplastics without extensive pre-treatment and repeated filtration. Field studies demonstrate that macroalgal assemblages can accumulate significant quantities of microplastics embedded within biofilms or mucilage, necessitating more exhaustive laboratory processing relative to more structurally accessible matrices such as seagrass detritus [

26,

29]. These ecological patterns align with the observed life cycle results: the algae scenario, representing more complex biomass, incurs higher impacts per gram of microplastic quantified.

The influence of background datasets and regional electricity profiles also plays a role in several impact categories. While the present study uses a combined database that includes datasets not specific to the Colombian energy mix, the choice of electricity source and chemical production pathways influences impacts such as ionising radiation and particulate matter formation. This observation echoes broader LCA literature showing that differences in regional electricity mixes and upstream supply chains can significantly alter impact profiles, particularly in categories sensitive to energy source composition.

This contribution analysis aims to identify the main drivers of environmental impacts across the evaluated laboratory workflows, focusing on energy use, chemical reagents and filtration-related consumables. The analysis is intended to support the interpretation of the LCA results rather than to provide a detailed inventory-level breakdown. Across all impact categories, energy consumption associated with laboratory equipment (e.g., ovens, agitation and filtration systems) emerges as a dominant contributor, particularly in categories related to climate change and cumulative energy demand. The prominence of climate change and related impact categories in the present results reflects patterns commonly observed in LCA studies of energy-intensive processes. Previous assessments have shown that prolonged operating times of equipment and high electricity demand can be decisive contributors to overall environmental burdens, a trend that is consistent with the higher impacts observed in the more analytically demanding scenario evaluated here [

13].

Workflows involving prolonged heating or repeated processing steps show consistently higher impacts, highlighting the sensitivity of laboratory-scale analyses to electricity use. Chemical reagents contribute significantly to toxicity-related categories, including freshwater and marine ecotoxicity, as well as human toxicity indicators. The use of strong oxidants and high-purity chemicals increases upstream impacts associated with chemical production, which partially explains the higher environmental burdens observed in chemically intensive workflows. Filtration steps and single-use consumables contribute to material- and waste-related impacts, particularly when fine-pore filters and disposable units are employed. Although their relative contribution is generally lower than that of energy and reagents, their cumulative effect becomes relevant when workflows require multiple filtration stages.

The comparative approach adopted in this study aligns with earlier process-oriented LCA applications, where scenario-based analysis has proven effective in identifying trade-offs between operational complexity and environmental performance. Such consistency reinforces the validity of using LCA as a framework for evaluating alternative laboratory workflows for microplastic quantification [

14].

The need for methodological standardisation in microplastic quantification has been emphasised in the literature. The absence of harmonised procedures contributes not only to variability in ecological data but also limits comparability among studies [

30,

31]. Optimised protocols that minimise reagent use and reduce instrument time could indirectly decrease the environmental burdens associated with analytical routines, although dedicated life cycle assessments of such strategies remain scarce.

5. Perspectives and Future Work Regarding LCA of Microplastic Quantification

Future research on the life cycle impacts of microplastic quantification should prioritise the development of standardised, low-impact analytical protocols. As highlighted in methodological reviews, the absence of harmonised procedures leads to limited comparability among ecological datasets and analytical outcomes [

20,

32]. Standardisation efforts could target digestion conditions, filter types, spectroscopic minimum detection thresholds and sample pre-treatment workflows. Harmonised methods would also enable cross-laboratory comparisons of analytical performance and environmental burdens, providing a clearer understanding of the trade-off between analytical accuracy and environmental cost.

A second avenue for future work concerns the integration of energy-optimised laboratory practices into microplastic research. Several studies examining sustainability in scientific laboratories report that analytical instruments, particularly thermal and spectroscopic equipment, are frequently operated under non-optimised conditions that elevate energy demand unnecessarily [

33]. Implementing best practices such as batch processing, timed shutdown systems, and instrument energy profiling could substantially reduce the life cycle impacts associated with routine microplastic analysis. Future LCAs specifically quantifying the benefits of such optimisations would provide valuable guidance to laboratories and research networks.

Another promising direction involves expanding LCA boundaries beyond the laboratory gate to incorporate field sampling logistics, biosphere interactions, and long-term environmental feedback. Research into the environmental behaviour of microplastics in vegetated coastal systems shows complex retention and release dynamics depending on hydrodynamic exposure, biofilm development, and vegetation density [

34,

35]. Incorporating these processes into hybrid LCA-modelling frameworks—potentially coupled with ecological transport models—could yield richer insights into how microplastics move through and persist within seagrass beds and macroalgal assemblages.

Future assessments should also explore alternative extraction technologies that minimise chemical reagents. Emerging techniques such as enzymatic digestion, density separation using biodegradable media, and machine learning-assisted automated particle recognition are increasingly being investigated as lower-impact alternatives to conventional oxidative digestion and manual microscopy [

32]. Comparative LCAs of these novel approaches could identify not only environmentally preferable workflows but also those that improve particle recovery and reduce analytical bias.

Another priority is to expand LCA comparisons across multiple types of matrices—including sediments, biofilms, marine snow, atmospheric deposition, and biota. Evidence shows that microplastic extraction efficiency and environmental burdens vary substantially depending on matrix organic content and particle entrapment levels [

23]. Systematically evaluating and comparing laboratory burdens across these matrices would help clarify whether certain ecosystems or sample types disproportionately drive environmental impacts associated with scientific research. This would also support the development of ecosystem-specific guidance for optimised sample processing.

Future work could benefit from integrating LCA with risk assessment and policy evaluation frameworks. Emerging synthesis papers underscore that effective microplastic policy requires robust, reproducible quantification and improved understanding of exposure pathways [

36]. Linking life cycle burdens of analytical protocols with policy needs—such as monitoring under regional marine strategies or blue carbon accounting—could help decision-makers evaluate trade-offs between scientific precision and environmental sustainability. In the long term, developing sustainable monitoring frameworks that balance scientific quality with reduced laboratory impacts may be critical for large-scale microplastic surveillance programs.

6. Conclusions

This study provides the first life cycle-based evaluation of microplastic quantification workflows applied to two ecologically relevant marine matrices. The results demonstrate that laboratory processing is highly sensitive to biomass characteristics, with the algae scenario consistently showing greater environmental burdens across several impact categories due to longer digestion processes, increased reagent demand and higher energy consumption. In contrast, the seagrass scenario required fewer pre-treatment steps and exhibited substantially lower impacts per functional unit.

The findings highlight the importance of considering methodological choices, sample matrix complexity and background dataset composition when interpreting microplastic analytical results. They also underscore that laboratory protocols themselves carry measurable environmental footprints which, although small relative to large-scale industrial processes, become relevant when analytical workflows are repeated across extensive monitoring programmes.

Furthermore, the study identifies opportunities to reduce impacts by optimising digestion conditions, refining energy-intensive stages and adopting harmonised procedures. Future research should integrate alternative extraction methods, evaluate additional matrices and consider hybrid LCA-ecological frameworks to better connect analytical sustainability with environmental monitoring needs. Overall, this work establishes a foundational benchmark for improving the environmental performance of microplastic quantification, contributing to more sustainable and reliable assessments of marine pollution.

Author Contributions

R.F.C.-Q. participated in the review of the resources used and of the manuscript and supervised the methodology as whole. L.S.C.-M. participated in the simulation of LCA, and in the construction of the original draft, specifically in the results sections. J.C.C.-Q. contributed to the overall supervision of the draft, and S.P.-R. participated in the construction of the original draft, specifically in the methodology, discussion and future work sections. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the program: 948 – 2024 ORQUÍDEAS MUJERES EN LA CIENCIA,

within the research. Projecttitle “Estudio de las posibilidades del uso de biomasa endógena colombiana en la

producción de bio-productos a través de métodos termo- y electro-catalíticos” Code: 109361. Also, this work was

also supported by the National Science Centre (NCN) of Poland through the project OPUS-26 (Project No.

2023/51/B/ST5/00752). Project title “Surface-Interface engineering in constructing multi-dimensional functional

hybrid piezophotocatalysts for redox selective organic synthesis in flow”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for the support given by the program: 948 – 2024 ORQUÍDEAS MUJERES EN LA CIENCIA, within the research Project: “Estudio de las posibilidades del uso de biomasa endógena colombiana en la producción de bio-productos a través de métodos termo- y electro-catalíticos” Code: 109361. Also, the authors highlight the support given by by the National Science Centre (NCN) of Poland within the project “Surface-Interface engineering in constructing multi-dimensional functional hybrid piezophotocatalysts for redox selective organic synthesis in flow”, project OPUS-26 (Project No. 2023/51/B/ST5/00752).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| OzLCI2019, ELCD and USDA |

Free databases for LCA and sustainability data |

| FTIR and µ-FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy, and micro-FTIR |

| GWP |

Climate Change |

| FETPinf |

Freshwater Ecotoxicity |

| FEP |

Freshwater Eutrophication |

| HTPinf |

Human Toxicity |

| IRP_HE |

Ionising Radiation |

| METPinf |

Marine Ecotoxicity |

| MEP |

Marine Eutrophication |

| ODPinf |

Ozone Depletion |

| PMFP |

Particulate Matter Formation |

| POFP |

Photochemical Oxidant Formation |

| TAP100 |

Terrestrial Acidification |

| TETPinf |

Terrestrial Ecotoxicity |

| CFCs |

Chlorofluorocarbons |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| NOx |

The gases nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide |

| VOCs |

Volatile Organic Compounds |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ILCD |

International Life Cycle Data |

| EPS |

Extracellular polymeric substances |

References

- Greenshields, J.; Irving, A.D.; Anastasi, A.; Capper, A. Sediment composition influences microplastic trapping in seagrass meadows. Environmental Pollution 2025, 373, 126090. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; He, Y.; Yan, Y.; Junaid, M.; Wang, J. Characteristics, Toxic Effects, and Analytical Methods of Microplastics in the Atmosphere. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2747. [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.; Slat, B.; Ferrari, F.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Aitken, J.; Marthouse, R.; Hajbane, S.; Cunsolo, S.; Schwarz, A.; Levivier, A.; Noble, K.; Debeljak, P.; Maral, H.; Schoeneich-Argent, R.; Brambini, R.; Reisser, J. Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Scientific Reports 2018, 8(1), 4666. [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Prabhakar, R.; Barua, V.B.; Zekker, I.; Burlakovs, J.; Krauklis, A.; Hogland, W.; Vincevica-Gaile, Z. Microplastics in aquatic systems: A comprehensive review of its distribution, environmental interactions, and health risks. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2024, 32(1), 56–88. [CrossRef]

- Thin, Z.S.; Chew, J.; Ong, T.Y.Y.; Raja Ali, R.A.; Gew, L.T. Impact of microplastics on the human gut microbiome: a systematic review of microbial composition, diversity, and metabolic disruptions. BMC Gastroenterology 2025, 25(1), 583. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Tu, C.; Fu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, K.; Zhao, X.; Li, L.; Waniek, J. J.; Luo, Y. Characteristics and distribution of microplastics in the coastal mangrove sediments of China. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 703, 134807. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, H.; Qasim, W.; Wan, L.; Wang, Y.; Lian, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, J.; Lin, S.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Drip fertigation with straw incorporation significantly reduces N2O emission and N leaching while maintaining high vegetable yields in solar greenhouse production. Environmental Pollution 2021, 273, 116521. [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, A.C.; de Abreu, C.H.M.; Crizanto, J.L.P.; Cunha, H.F.A.; Brito, A.U.; Pereira, N.N. Modeling pollutant dispersion scenarios in high vessel-traffic areas of the Lower Amazon River. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 168, 112404. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, N.; Liu, T.; Feng, C.; Ma, L.; Chen, S.; Li, M. The mechanism of nitrate-Cr(VI) reduction mediated by microbial under different initial pHs. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 393, 122434. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, N.; Liu, S.; Xiao, Q.; Geng, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, F.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Ren, A.; Xue, T.; Ji, J. The PM2.5 concentration reduction improves survival rate of lung cancer in Beijing. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858, 159857. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, E.; Marín, A.; Gámez-Pérez, J.; Cabedo, L. Recent advances in the relationships between biofilms and microplastics in natural environments. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2024, 40(7), 220. [CrossRef]

- Oberbeckmann, S.; Labrenz, M. Marine Microbial Assemblages on Microplastics: Diversity, Adaptation, and Role in Degradation. Annual Review of Marine Science 2020, 12(1), 209–232. [CrossRef]

- Colmenares-Quintero, R.F.; Corredor-Muñoz, L.S.; Piedrahita-Rodriguez, S. Valorisation Pathways Analysis of Marine and Coastal Resources for Renewable Energy Carriers and High Value Bioproducts in La Guajira, Colombia. Energies 2025, 18, 6459. [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Arcos, C.; Caicedo-Concha, D.M.; Coz, A.; Llano, T.; Colmenares-Quintero, J.C.; Colmenares-Quintero, R.F. Assessment of the Potential for Biogas Production in Post-Conflict Rural Areas in Colombia Using Cocoa Residues. Energies 2025, 18, 3091. [CrossRef]

- Colmenares-Quintero, R.F.; Rojas, N.; Colmenares-Quintero, J.C.; Stansfield, K.E.; Villar-Villar, S.S.; Albericci-Avendaño, S.E. Design of an Integral Simulation Model for Solar-Powered Seawater Desalination in Coastal Communities: A Case Study in Manaure, La Guajira, Colombia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1505. [CrossRef]

- Colmenares-Quintero, R.F.; Caicedo-Concha, D.M.; Corredor-Muñoz, L.S.; Piedrahita-Rodríguez, S.; Coz, A.; Colmenares-Quintero, J.C. A Critical Review of Life Cycle Assessments of Cocoa: Environmental Impacts and Methodological Challenges for Sustainable Production. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 419. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.; Chomkhamsri, K.; Brandao, M.; Pant, R.; Ardente, F.; Pennington, D.; Manfredi, S.; De Camillis, C.; Goralczyk, M. International Reference Life Cycle Data System (ILCD) Handbook—General guide for Life Cycle Assessment—Detailed guidance. EUR 24708 EN. Luxembourg (Luxembourg): Publications Office of the European Union; 2010. JRC48157.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2006). ISO 14040:2006 – Environmental management — Life cycle assessment — Principles and framework. ISO.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2006). ISO 14044:2006 – Environmental management — Life cycle assessment — Requirements and guidelines. ISO.

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Methods for sampling and detection of microplastics in water and sediment: A critical review. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2019, 110, 150–159. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhang, M.; Jing, R.; Bai, L.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, M.; Pei, X.; Wei, L.; Chen, G.H. Thiosulfate as the electron acceptor in Sulfur Bioconversion-Associated Process (SBAP) for sewage treatment. Water Research 2019, 163, 114850. [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 586, 127–141. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, T.; Kang, S.; Allen, S.; Luo, X.; Allen, D. Microplastics in glaciers of the Tibetan Plateau: Evidence for the long-range transport of microplastics. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 758, 143634. [CrossRef]

- de los Santos, C.B.; Krång, A.S.; Infantes, E. Microplastic retention by marine vegetated canopies: Simulations with seagrass meadows in a hydraulic flume. Environmental Pollution 2021, 269, 116050. [CrossRef]

- Aldana Arana, D.; Gil Cortés, T.P.; Castillo Escalante, V.; Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E. Pelagic Sargassum as a Potential Vector for Microplastics into Coastal Ecosystems. Phycology 2024, 4, 139-152. [CrossRef]

- GreenDelta. openLCA 2.0 – The world’s leading open source LCA software. GreenDelta GmbH 2023. https://www.openlca.org.

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: a harmonised life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2017, 22(2), 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Raccary, B.; Loubet, P.; Peres, C.; Sonnemann, G. Evaluating the environmental impacts of analytical chemistry methods: From a critical review towards a proposal using a life cycle approach. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2022, 147, 116525. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, N.; Liu, S.; Xiao, Q.; Geng, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, F.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Ren, A.; Xue, T.; Ji, J. The PM2.5 concentration reduction improves survival rate of lung cancer in Beijing. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858, 159857. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Alegre, R.; Durán-Videra, S.; Carmona-Fernández, D.; Pérez Megías, L.; Andecochea Saiz, C.; You, X. Comparative Assessment of Protocols for Microplastic Quantification in Wastewater. Microplastics 2025, 4, 49. [CrossRef]

- Zea Cobos, A.G.; Amón, J.; León, E.; Caballero, P. Standardization of FTIR-Based Methodologies for Microplastics Detection in Drinking Water: A Meta-Analysis Indeed and Practical Approach. Water 2024, 16, 3170. [CrossRef]

- Cowger, W.; Gray, A.; Christiansen, S.H.; DeFrond, H.; Deshpande, A.D.; Hemabessiere, L.; Lee, E.; Mill, L.; Munno, K.; Ossmann, B.E.; Pittroff, M.; Rochman, C.; Sarau, G.; Tarby, S.; Primpke, S. Critical Review of Processing and Classification Techniques for Images and Spectra in Microplastic Research. Applied Spectroscopy 2020, 74(9), 989-1010. PMID: 32500727. [CrossRef]

- Eckelman, M.J.; Sherman, J. Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health. PLOS ONE 2016, 11(6), e0157014. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, M.; Bergman, S.; Björk, M.; Diaz-Almela, E.; Granberg, M.; Gullström, M.; Leiva-Dueñas, C.; Magnusson, K.; Marco-Méndez, C.; Piñeiro-Juncal, N.; Mateo, M.Á. A temporal record of microplastic pollution in Mediterranean seagrass soils. Environmental Pollution 2021, 273, 116451. [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Dixon, S.J. Microplastics: An introduction to environmental transport processes. WIREs Water 2018, 5(2). [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Bakir, A.; Burton, G.A.; Janssen, C.R. Microplastic as a Vector for Chemicals in the Aquatic Environment: Critical Review and Model-Supported Reinterpretation of Empirical Studies. Environmental Science & Technology 2016, 50(7), 3315–3326. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).