1. Introduction

Cancer survivors often experience behavioral and cognitive changes [

1,

2]. Prostate cancer is highly survivable but patients suffer from the effects of the cancer and cancer treatment [

3]. Apolipoprotein E (apoE) is involved in cholesterol and lipid homeostasis [

4], immunomodulation [

5], and apoE expression is increased in prostate cancer and correlate with poor prognosis [

6]. In humans, there are three major isoforms of apoE, E2, E3, and E4. E4 is associated with increased susceptibility to develop cognitive injury after cancer treatment in breast cancer, lymphoma, and testicular cancer patients [

7].

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), often used in prostate cancer patients, can increase cardiovascular risk [

8], diabetes risk, and osteoporosis risk [

9], cognitive injury [

10,

11], and risk to develop Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [

12]. Exercise intervention might improve quality of life in survivors [

13,

14] but might increase salivary testosterone levels. In addition, the gut microbiome can generate testosterone and as a result promote prostate cancer growth and resistance in prostate cancer patients who received ADT [

15,

16].

The gut microbiome interacts with the brain [

17] via the gut–brain axis and apoE might be involved in the regulation of this axis in cancer patients, as it is expressed in the gut [

18], modulates inflammation and gastrointestinal health [

19], antitumor activity [

20,

21], survival in melanoma patients, and risk to develop gastric cancers [

20]. The beneficial effects of exercise intervention on the brain might involve alterations in the gut microbiome and gut-brain axis [

22,

23], and these effects might be

APOE genotype-dependent. We recently reported that exercise intervention,

APOE genotype, and salivary testosterone levels modulate gut microbiome-cognition association in prostate cancer survivors [

24].

In addition to exercise, diet has a strong effect on the gut microbiome [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. The Diet Questionnaire III (DHQ) from the National Cancer Institute for those over 19 years of age and based on 24-hour dietary recall data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys [

30] is often used to assess diets in study participants. However, as it contains 201 variables, its use in integrated diet gut microbiome analyses with limited sample size is statistically challenging. Therefore, diet indices/scores have been proposed [

31,

32], especially considering those related to the Mediterranean diet which has consistently been shown to be beneficial for gut [

33] and brain health [

34]. In a recent systematic review, the Mediterranean diet was not consistently linked to reduced prostate cancer risk [

35]. This might be due to modulating effects of genetic factors.

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of diet-microbiome associations in prostate cancer survivors enrolled in a randomized exercise intervention trial using the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Score (MEDAS), Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015), and the Mediterranean-Dash Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet scores.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subject Recruitment, Study Design, and Study Participants

This study represents a secondary analysis of dietary intake and gut microbiome composition in prostate cancer survivors enrolled in a randomized exercise intervention trial [

24,

36]. The parent studies evaluated the effects of exercise modality on fall risk, cognitive function, and physiological outcomes in men with a history of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for prostate cancer. The present analysis examines associations between habitual dietary intake and gut microbiome diversity and composition, with attention to effect modification by exercise intervention,

APOE genotype, and testosterone status. Men were eligible if they had a confirmed diagnosis of prostate cancer, had received ADT (currently or within the past 10 years), were aged 55 years or older, were able to provide informed consent, and had no contraindications to moderate-intensity exercise. Exclusion criteria included unstable cardiovascular disease, neurological conditions affecting cognition or balance, current chemotherapy, and antibiotic use within 30 days of stool sample collection. A total of 79 prostate cancer survivors with complete microbiome data were included. The cohort was predominantly elderly (age range: 62-81 years), with 59.5% (n = 47) having metastatic disease. All participants had ADT exposure, creating a relatively homogeneous hormonal milieu. Participants were randomized to one of three 12-week exercise interventions: progressive resistance training (n = 36, 45.6%), Tai Chi (n = 23, 29.1%), or flexibility and stretching exercises (control; n = 20, 25.3%). Dietary assessment and biological sample collection occurred at baseline, prior to initiation of the exercise intervention. Exercise group assignment served as a potential effect modifier of diet-microbiome associations. This study was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Cognitive Testing

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment [

37] was administered through videoconferencing as reported [

24].

2.3. Dietare Assessment

Habitual dietary intake was assessed using the National Cancer Institute Diet History Questionnaire III (DHQ-III), a validated food frequency questionnaire capturing usual dietary intake over the preceding 12 months [

30]. The DHQ-III yields estimates for 201 dietary variables including macronutrients (energy, protein, carbohydrates, total fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids), micronutrients (vitamins A, C, D, E, K, B-complex; minerals including calcium, iron, magnesium, zinc, selenium), food groups (fruits, vegetables, whole grains, dairy, protein foods), and bioactive compounds (dietary fiber, carotenoids, flavonoids, caffeine). Missing values were handled via complete-case analysis for each model.

Given the high dimensionality of dietary data (201 variables) relative to sample size (n = 79), we employed both theory-driven dietary pattern scores and data-driven feature selection. The 13-item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) was calculated according to Schroder et al. [

38], with one point assigned for each dietary criterion met (total range 0-13). The Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015) was calculated using the density-based scoring method [

39], comprising nine adequacy components and four moderation components (total range 0-100). The Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet score was calculated according to Morris et al. [

40], comprising 10 brain-healthy and 5 brain-unhealthy food groups scored based on consumption frequency (total range 0-15).

Data-driven feature selection employed Random Forest models fit using all 201 dietary variables as predictors of Shannon diversity, with variable importance assessed using permutation-based scores. Cross-validated LASSO regression was performed using the glmnet package [

41] with 10-fold cross-validation, selecting the optimal regularization parameter to minimize cross-validated mean squared error.

2.4. Sample Collection of Saliva and Stool Samples

Stool was collected for gut microbiome analysis and saliva samples were collected for

APOE genotyping and analysis of salivary testosterone (T) levels, as reported [

24]. Briefly, participants collected stool samples at home using OMNIgene-GUT tubes (DNA Genotek, Ottawa, Canada) for DNA stabilization, returning samples via mail at ambient temperature. Samples were stored at -80C upon receipt. Saliva samples were collected using Oragene-DNA kits (DNA Genotek) for

APOE genotyping and testosterone measurement. Microbial community DNA was extracted using QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer instructions, with concentration and purity assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the 515F/806Rb primer pair with Illumina adapter sequences. PCR amplification was performed in triplicate, with replicates pooled prior to sequencing. Amplicon libraries were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform (v3 chemistry; 2 x 300 bp paired-end reads) at the Center for Quantitative Life Sciences, Oregon State University, targeting a minimum of 40,000 reads per sample. Quality control included ATCC 20-strain staggered mix mock communities to assess taxonomic assignment accuracy and molecular-grade water blanks to monitor contamination.

2.5. Bioinformatic Processing

Demultiplexed sequences were processed using the DADA2 pipeline [

42] in R (version 4.2). Processing included primer trimming using cutadapt [

43], quality filtering and trimming, error rate learning and denoising, paired-end read merging, chimera removal using the consensus method, and amplicon sequence variant (ASV) inference. Taxonomy was assigned using the naive Bayesian classifier in DADA2 against the SILVA database (version 138) [

44]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using FastTree [

45]. Microbiome data were organized into a phyloseq object [

46] containing the ASV abundance table, sample metadata, taxonomic assignments, and phylogenetic tree.

2.6. Host Factor Assessment

APOE genotype was determined from saliva DNA using TaqMan SNP genotyping assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific) targeting rs429358 and rs7412 polymorphisms. Genotypes were classified as E2 carriers (e2/e2 or e2/e3;

n = 7), E3/E3 homozygotes (

n = 46), or E4 carriers (e3/e4 or e4/e4; n = 17); nine participants had missing genotype data. Salivary testosterone was measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and log-transformed prior to analysis. Cognitive function was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [

37], administered via secure videoconferencing by trained research staff. Total MoCA scores range from 0 to 30, with scores below 26 generally indicating cognitive impairment.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed in R (version 4.2) with a fixed random seed. Statistical significance was defined as

p < 0.05, with false discovery rate (FDR) correction applied for multiple comparisons. Alpha diversity was calculated using Shannon diversity index, Simpson diversity index, and observed ASV richness on rarefied count data using the phyloseq package. Associations between dietary exposures and alpha diversity were evaluated using beta regression (betareg package [

47]) for bounded indices and linear regression for richness. Models included diet score, exercise group,

APOE status, age, and log-transformed testosterone as covariates. Interaction terms (diet score x exercise; diet score x

APOE) were tested separately.

Beta diversity was assessed using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (abundance-weighted) and Sorensen distance (presence/absence) computed using the vegan package [

48]. Associations between dietary exposures and community composition were tested using PERMANOVA via the adonis2 function [

49] with 999 permutations. Constrained ordination was performed using distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA) via the capscale function.

Taxon-level associations were tested using MaAsLin2 [

50] with negative binomial regression on raw counts. Taxa present in fewer than 10% of samples or with mean relative abundance below 0.01% were excluded. Multiple testing correction used the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR method [

51], with q < 0.10 considered significant and

q < 0.25 reported as suggestive.

Diet-cognition associations were evaluated by testing all 297 dietary variables (201 DHQ-III variables, 3 diet pattern scores, 41 component scores, and 52 derived variables) against MoCA scores using linear regression adjusted for exercise group,

APOE status, age, and testosterone. Variables surviving FDR correction were further evaluated in the E3/E3 subgroup. Mediation analysis testing whether diet-cognition associations were mediated through gut microbiome diversity was conducted using the mediation package [

52], estimating average causal mediation effect (ACME), average direct effect (ADE), and proportion mediated using 1,000 bootstrap simulations.

Key R packages included phyloseq (v1.40+) for microbiome data structures, vegan (v2.6+) for diversity metrics and PERMANOVA, MaAsLin2 (v1.10+) for taxon-level associations, betareg (v3.1+) for beta regression, glmnet (v4.1+) for LASSO regression, randomForest (v4.7+) for feature selection, and mediation (v4.5+) for mediation analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics and Baseline Assessments

This analysis included 79 prostate cancer survivors with complete microbiome and dietary data. The cohort was elderly (age range: 62–81 years) and predominantly affected by metastatic disease (59.5%, n = 47). All participants had prior exposure to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), creating a relatively homogeneous hormonal milieu. Participants were randomized across three exercise interventions: strength training (n = 36, 45.6%), Tai Chi (n = 23, 29.1%), and flexibility control (n = 20, 25.3%). APOE genotype was available for 70 participants (88.6%), distributed as E3/E3 homozygotes (n = 46, 65.7%), E4 carriers (n = 17, 24.3%), and E2 carriers (n = 7, 10.0%). Testosterone measurements were available for 73 participants (92.4%; log-transformed mean ± SD: 3.83 ± 0.87).

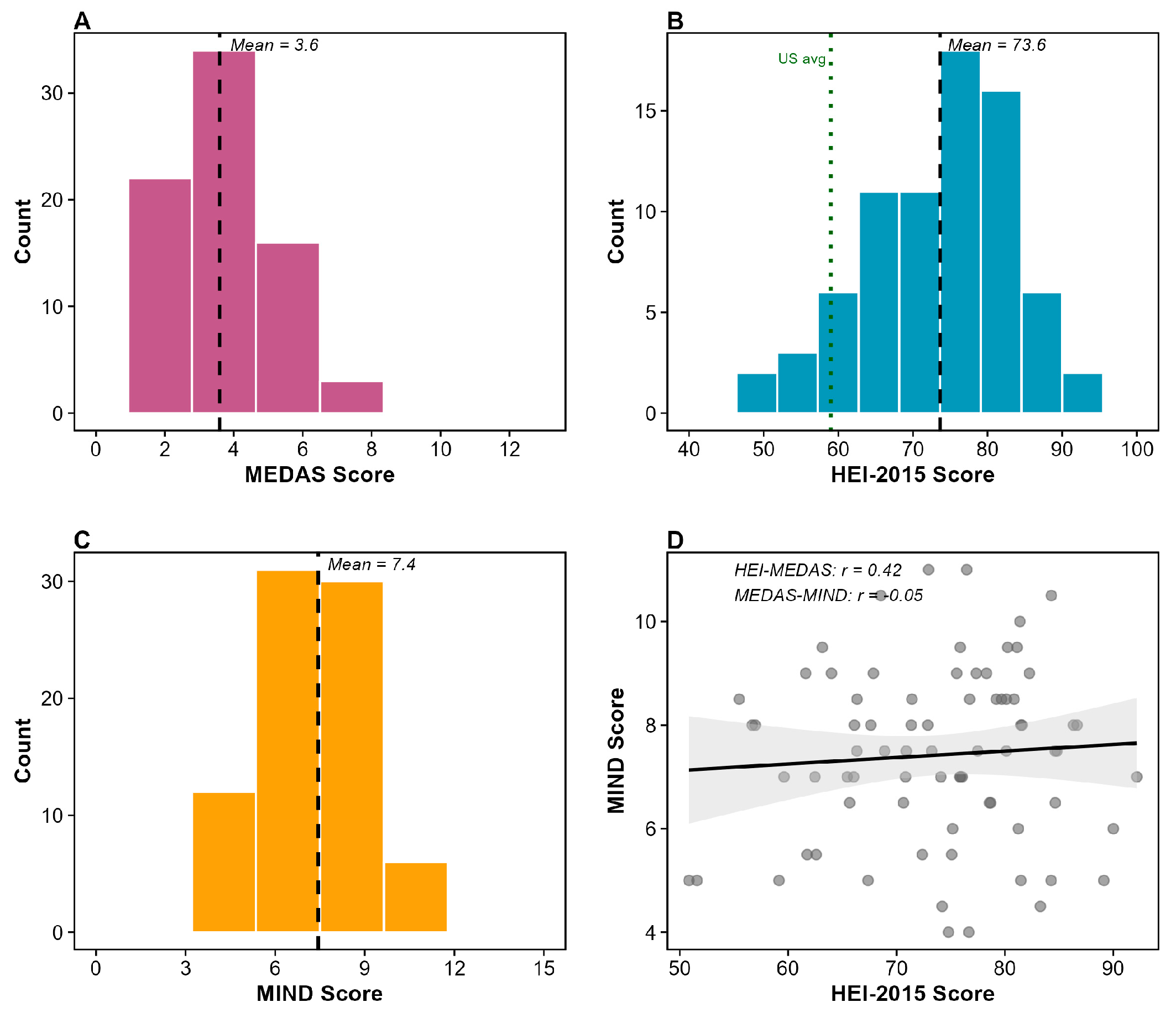

Dietary pattern scores showed moderate variation across the cohort (

Figure 1). Mediterranean Diet Adherence Score (MEDAS) ranged from 1 to 8 (mean ± SD: 3.59 ± 1.55;

n = 75), indicating relatively low Mediterranean diet adherence with the cohort utilizing approximately half of the possible 0–13 score range (

Figure 1A). In contrast, Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015) scores ranged from 50.9 to 92.2 (mean ± SD: 73.64 ± 9.22;

n = 75), indicating generally good overall diet quality exceeding the US national average of approximately 59 points (

Figure 1B). MIND diet scores ranged from 4 to 11 (mean ± SD: 7.44 ± 1.69;

n = 79), consistent with published values in older adult populations (

Figure 1C). The three diet scores were moderately to strongly correlated with one another (HEI-2015 and MIND:

r = 0.74; MEDAS and MIND:

r = 0.63; HEI-2015 and MEDAS:

r = 0.42) (

Figure 1D), suggesting they capture overlapping but distinct aspects of diet quality.

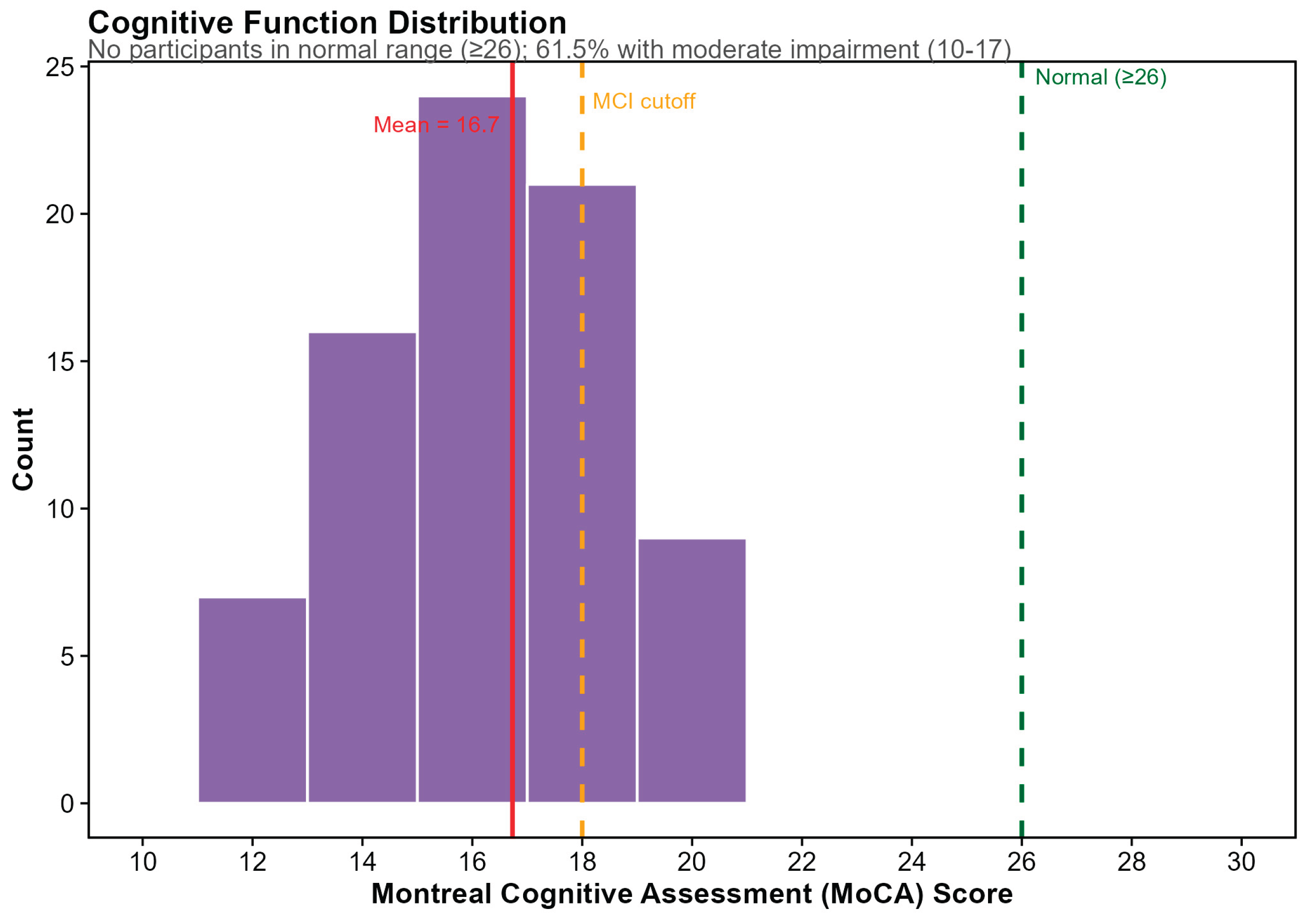

Among individual dietary variables, caffeine intake exhibited the highest coefficient of variation (CV = 79.4%; mean ± SD: 249 ± 198 mg/day; range: 0.2–962 mg/day), whereas diet pattern scores showed more restricted variation (CV: 12.5%–43.3%).

Cognitive function, assessed via Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), was available for 78 participants (98.7%). Scores ranged from 11 to 21 (mean ± SD: 16.73 ± 2.34), representing only one-third of the possible 0–30 score range. Notably, no participants scored in the normal cognitive range (≥26), with 38.5% (

n = 30) meeting criteria for mild cognitive impairment (MoCA 18–25) and 61.5% (

n = 48) meeting criteria for moderate impairment (MoCA 10–17) (

Figure 2). This restricted variance and universal cognitive impairment likely reflects the effects of ADT on cognition in this population, a constraint that informed our subsequent analyses of diet–cognition relationships.

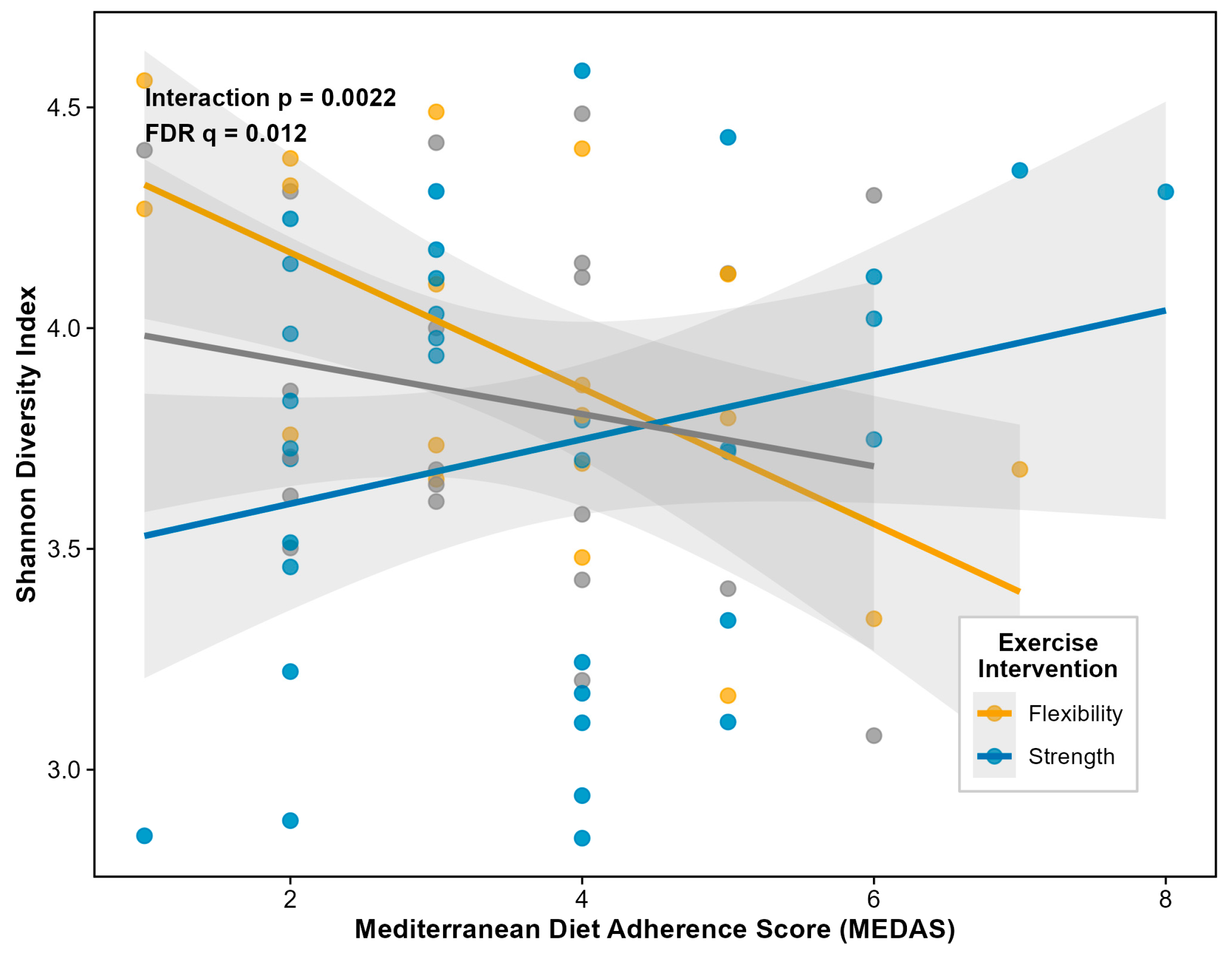

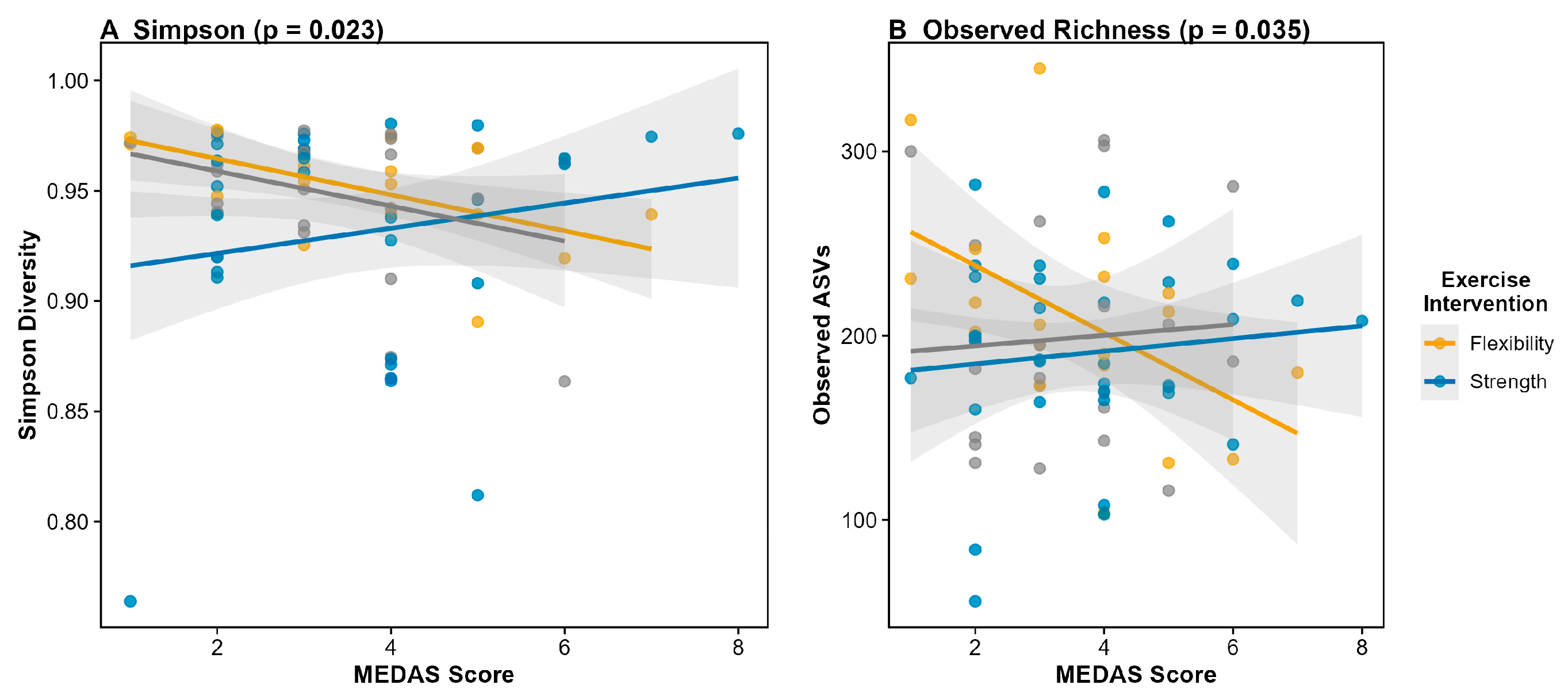

3.2. Diet–Microbiome Associations: Alpha Diversity

A striking interaction between Mediterranean diet adherence and exercise intervention emerged for alpha diversity. This interaction was significant across all metrics, with the strongest effect observed for Shannon diversity (interaction β = +0.55, SE = 0.18,

p = 0.0022, FDR

q = 0.012) (

Figure 3), and consistent effects for Simpson diversity (

p = 0.023) and observed richness (

p = 0.035) (

Figure 4.). The interaction pattern indicates that Mediterranean diet adherence shows stronger positive associations with microbiome diversity in the strength training and Tai Chi groups compared to the flexibility control group. This finding suggests that physical activity may enhance the gut microbiome's responsiveness to dietary inputs, a pattern with potential implications for integrated lifestyle interventions in cancer survivorship.

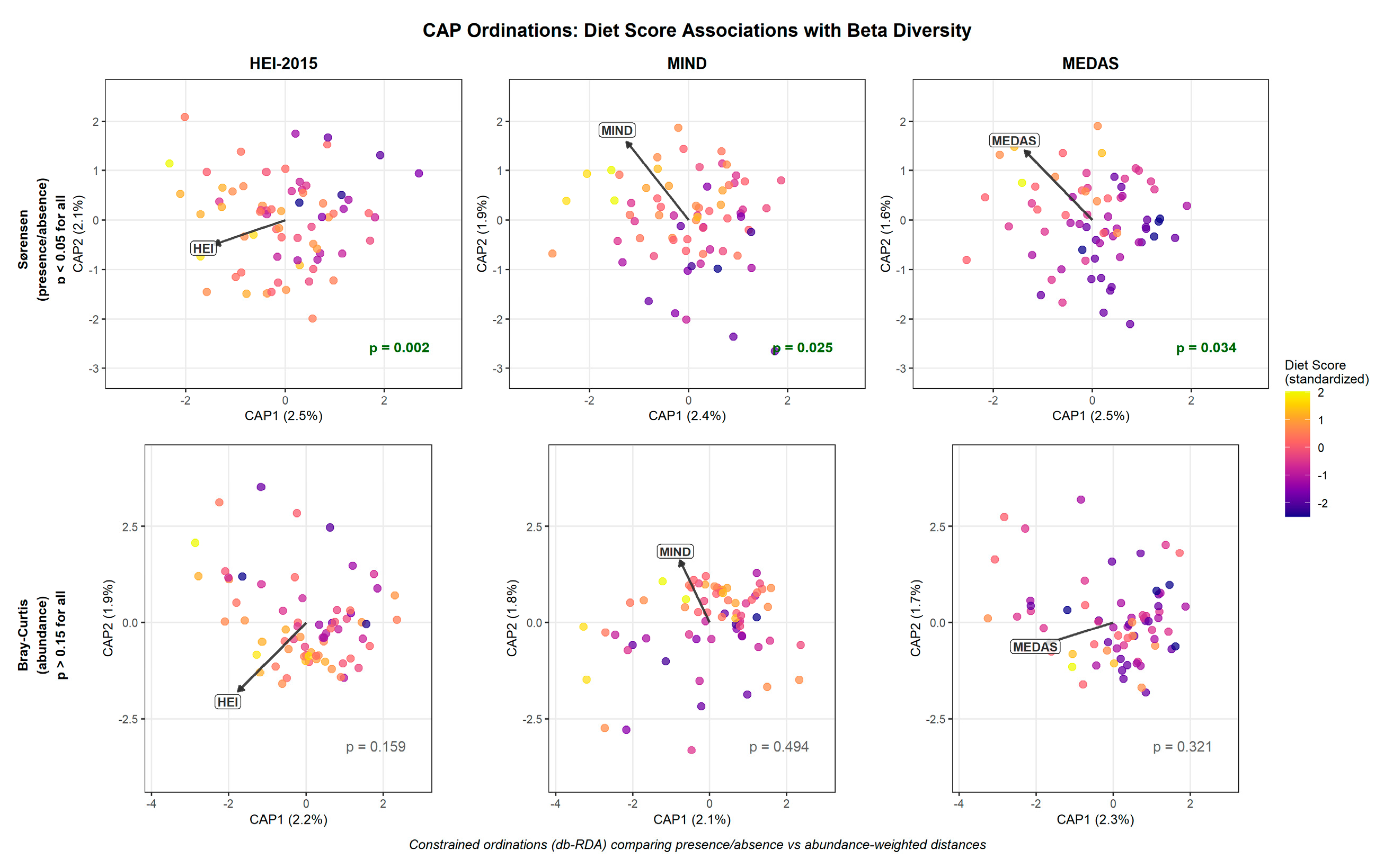

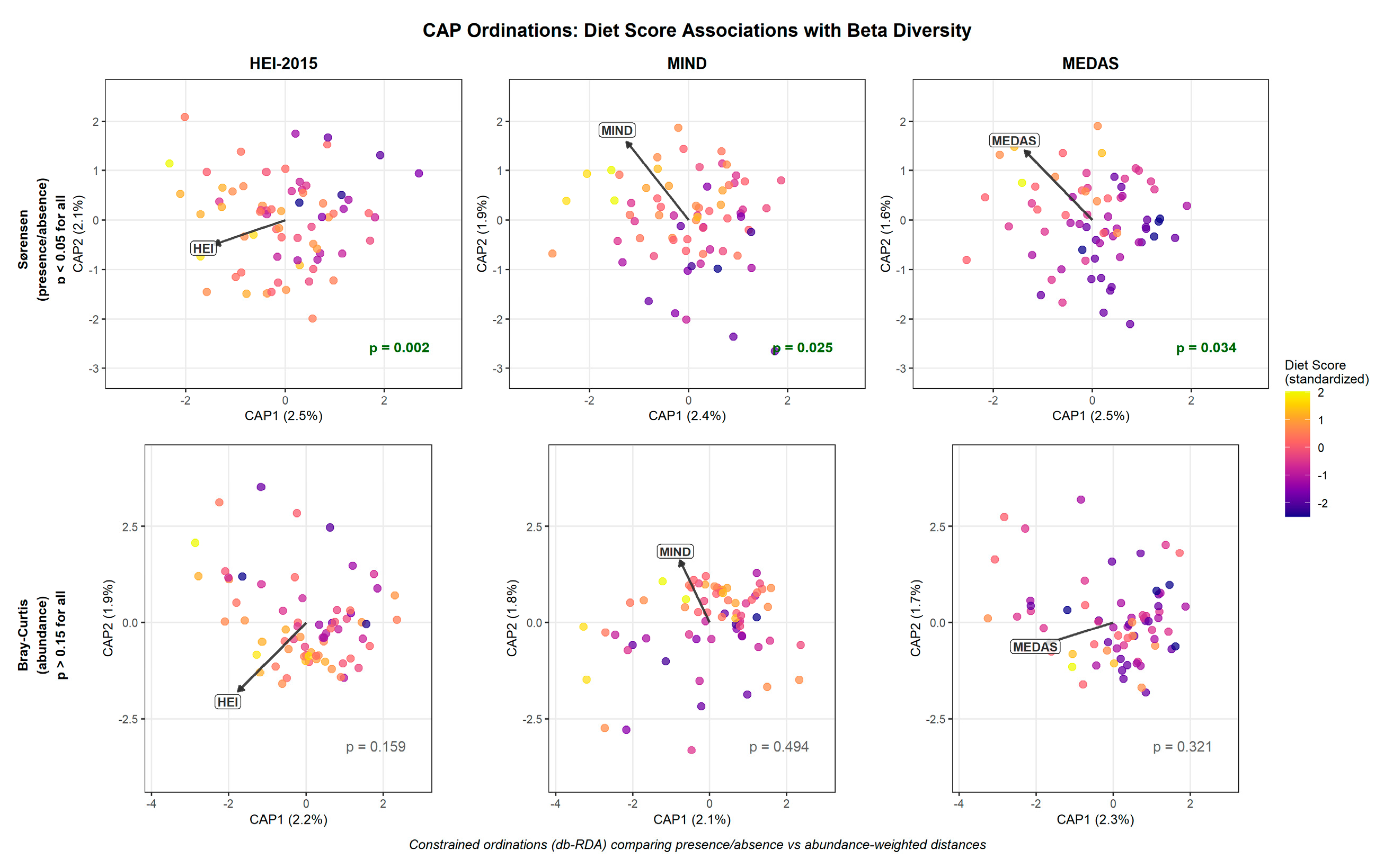

3.3. Diet–Microbiome Associations: Beta Diversity

Analysis of between-sample (beta) diversity revealed a striking dissociation between the two metrics examined (

Figure 5). All three diet quality scores significantly predicted Sørensen (presence/absence) distance – HEI-2015 (

R² = 2.3%,

p = 0.002), MIND (

R² = 2.0%,

p = 0.025), and MEDAS (

R² = 1.9%,

p = 0.034) – effects that remained significant after adjustment for exercise group and

APOE status. In marked contrast, none of the diet quality scores significantly predicted Bray-Curtis (abundance-weighted) distance: HEI-2015 (

R² = 1.7%,

p = 0.159), MIND (

R² = 1.4%,

p = 0.494), and MEDAS (

R² = 1.5%,

p = 0.321) (

Figure 5). This metric-specific dissociation suggests that diet quality primarily affects community membership—which taxa are present—rather than relative abundance patterns among established taxa.

Random Forest feature selection identified specific dietary variables associated with beta diversity beyond the aggregate diet scores. For Bray-Curtis distance, meat/poultry/eggs intake showed the strongest association (R² = 3.7%, F = 2.80, p = 0.004, FDR q < 0.05). For Sørensen distance, fruit intake was significantly associated with community membership (R² = 2.3%, F = 1.70, p = 0.029, FDR q < 0.10). The MIND diet score showed a significant interaction with exercise intervention on Sørensen distance (p = 0.030), with HEI-2015 showing a trend toward interaction (p = 0.076), while no significant diet × exercise interactions were observed for Bray-Curtis distance (all p > 0.67).

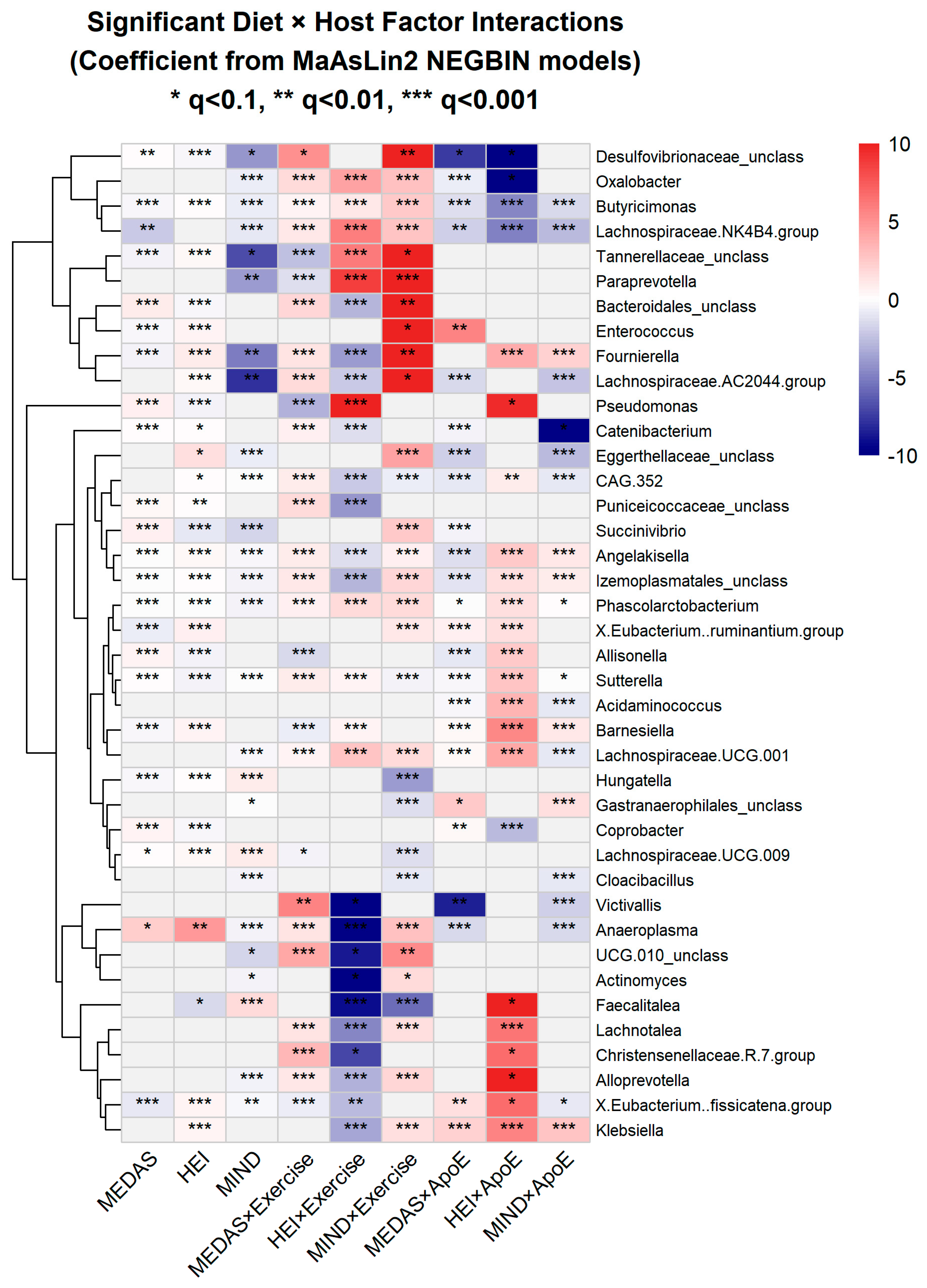

3.4. Taxon-Level Associations

MaAsLin2 analysis using negative binomial regression identified extensive associations between diet quality scores and genus-level abundances (

Figure 6). At FDR

q < 0.10, significant associations emerged for MEDAS (41 genera), HEI-2015 (49 genera), and MIND (39 genera). The most responsive genera included known health-associated taxa such as

Phascolarctobacterium (a short-chain fatty acid producer), members of the Lachnospiraceae family, and

Butyricimonas. Both positive and negative associations were observed, indicating that diet quality scores promote certain taxa while suppressing others.

These taxon-level effects were substantially modified by host factors. Diet × exercise interactions (FDR q < 0.10) affected 55 genera for MEDAS, 48 genera for HEI, and 42 genera for MIND. For MEDAS × exercise interactions specifically, top responding genera included Prevotella_9 (strongest MEDAS × Tai Chi interaction), Phascolarctobacterium (consistent MEDAS × strength training effects), and Anaeroplasma (strong exercise-dependent responses). Diet effects were also modified by APOE genotype (40–41 genera per diet score, q < 0.10) and testosterone status (34–51 genera per diet score), providing evidence for gene–diet–microbiome and hormone–diet–microbiome interactions in this cohort.

Across all main effect and interaction analyses, 129 unique genera showed at least one significant association (q < 0.10) with diet quality scores or diet × host factor interactions. Several genera showed remarkable consistency, with Angelakisella, Butyricimonas, Izemoplasmatales (unclassified), Phascolarctobacterium, and Sutterella each showing significant effects across all nine analysis categories (three main effects plus six interaction categories). Given caffeine's strong association with cognitive function (detailed below), we specifically tested for caffeine–taxa associations across 227 genera. After FDR correction, no significant associations emerged (lowest q = 0.69), indicating definitively null results for direct caffeine effects on gut microbial composition.

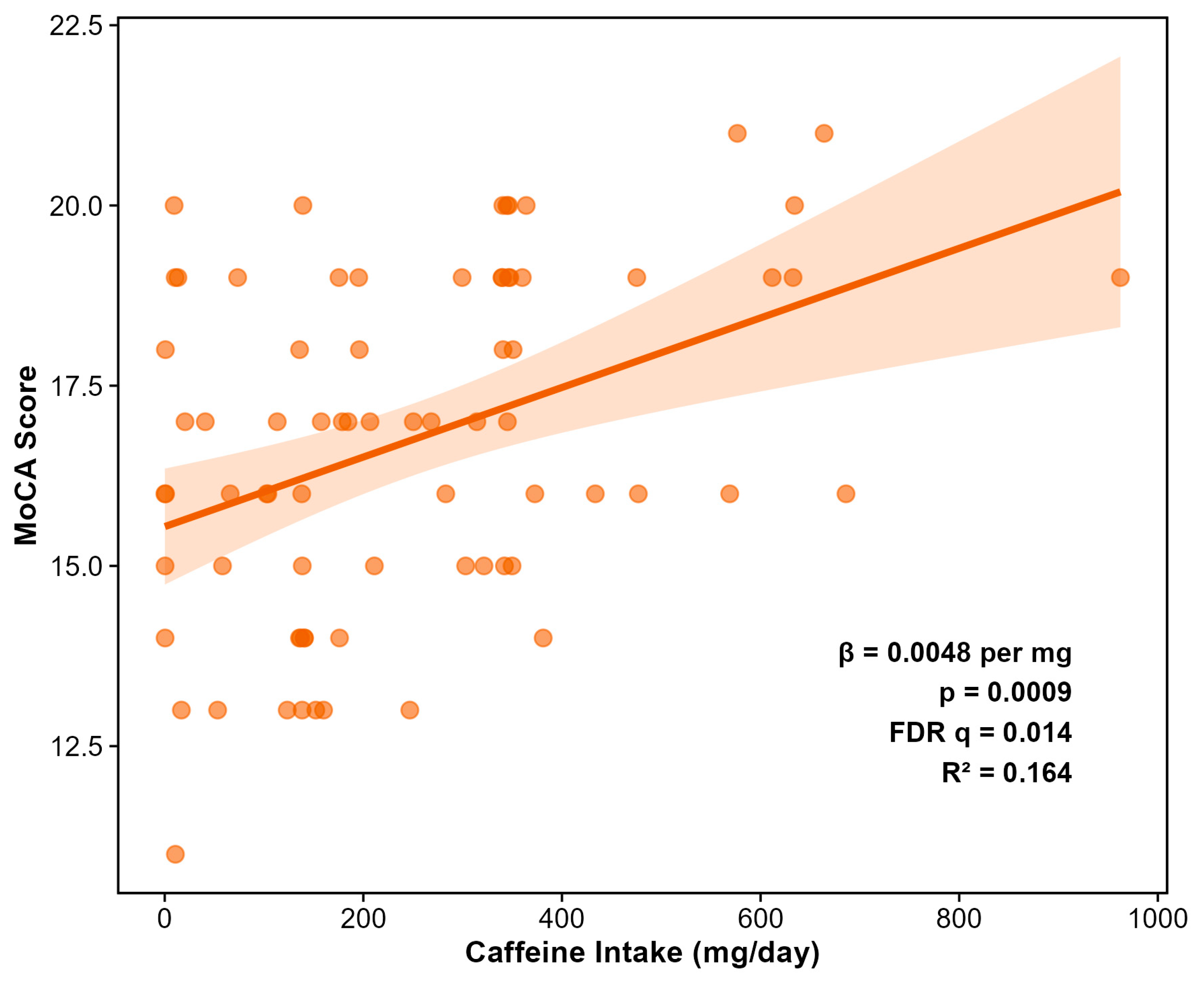

3.5. Dietary Predictors of Cognitive Function

Comprehensive feature selection across 297 dietary variables identified caffeine as the sole predictor of MoCA scores surviving FDR correction (β = +0.0047, SE = 0.0014,

p = 0.0009, FDR

q = 0.014) (

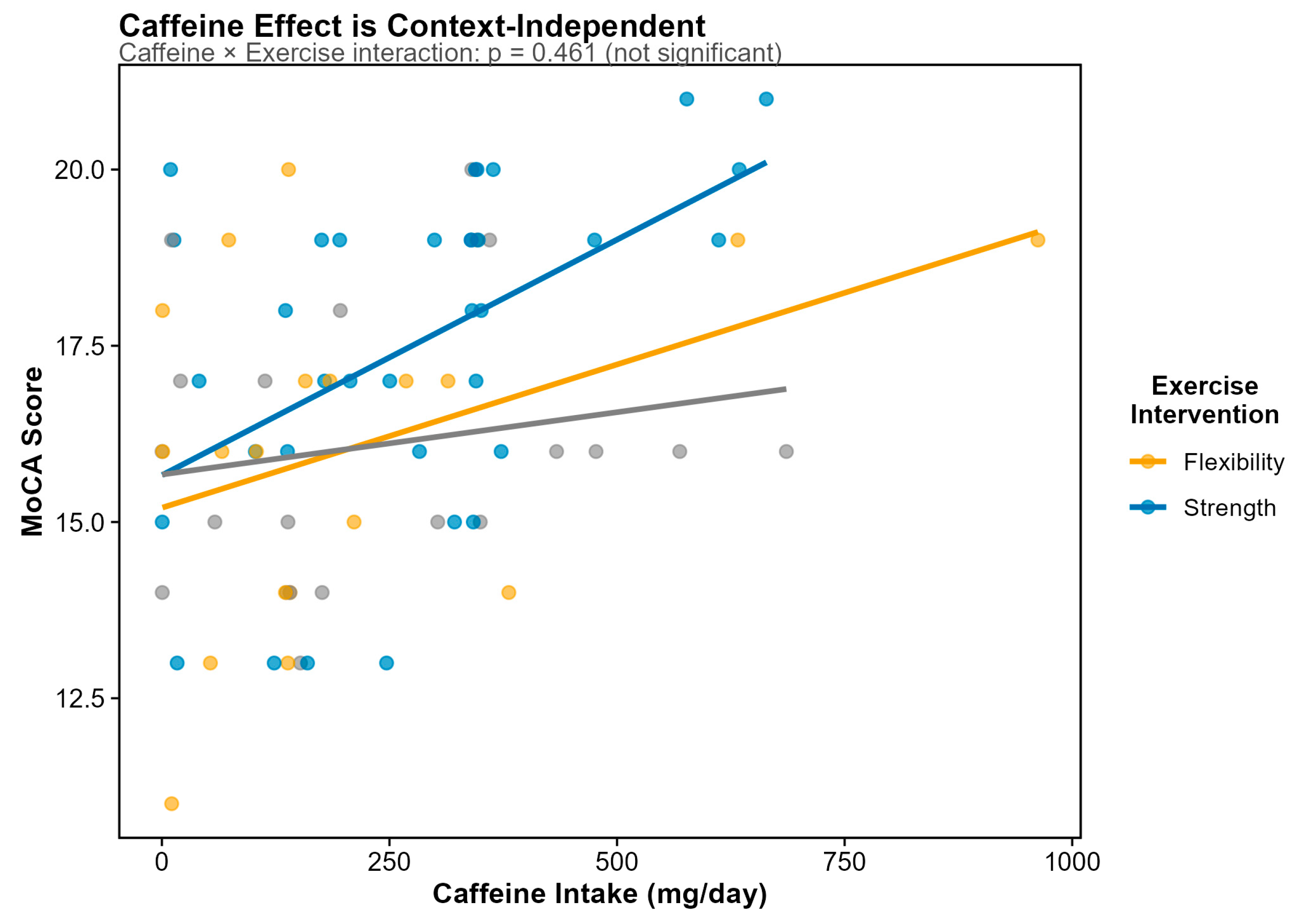

Figure 7). This positive association indicates that higher caffeine intake is associated with better cognitive performance, with an effect size corresponding to approximately 0.5 MoCA points per 100 mg daily caffeine (roughly one cup of coffee). Both Random Forest and LASSO feature selection independently identified caffeine as the top dietary predictor of MoCA, with caffeine being the only dietary variable retained at the optimal regularization parameter (λ.1se) in cross-validated LASSO regression. The beneficial effect of caffeine was context-independent; there was no caffein intake x exercise intervention.

Figure 8.

Association between caffeine intake and MoCA score stratified by exercise intervention group. Unlike the MEDAS × Exercise interaction on microbiome diversity, the caffeine-cognition association does not show significant effect modification by exercise (interaction p = 0.461). This context-independent effect suggests that caffeine's cognitive benefits operate through direct pharmacological mechanisms rather than through microbiome-mediated pathways that might be sensitive to exercise status.

Figure 8.

Association between caffeine intake and MoCA score stratified by exercise intervention group. Unlike the MEDAS × Exercise interaction on microbiome diversity, the caffeine-cognition association does not show significant effect modification by exercise (interaction p = 0.461). This context-independent effect suggests that caffeine's cognitive benefits operate through direct pharmacological mechanisms rather than through microbiome-mediated pathways that might be sensitive to exercise status.

Notably, none of the three diet quality scores significantly predicted MoCA scores: MIND (p = 0.636), MEDAS (p = 0.652), or HEI-2015 (p = 0.622). This null finding is particularly striking for the MIND diet, which was explicitly designed for cognitive outcomes. However, the restricted MoCA variance in this cohort (observed range 11–21 vs. possible 0–30; CV = 14%) and the universal cognitive impairment (0% with normal cognition) create a fundamentally different population context than the community-dwelling elderly cohorts in which the MIND diet was originally validated. The caffeine–MoCA association remained highly significant in the E3/E3 homozygous subgroup (n = 45, p = 0.0007), demonstrating robustness to genetic stratification and ruling out confounding by APOE-related differences in caffeine metabolism or cognition.

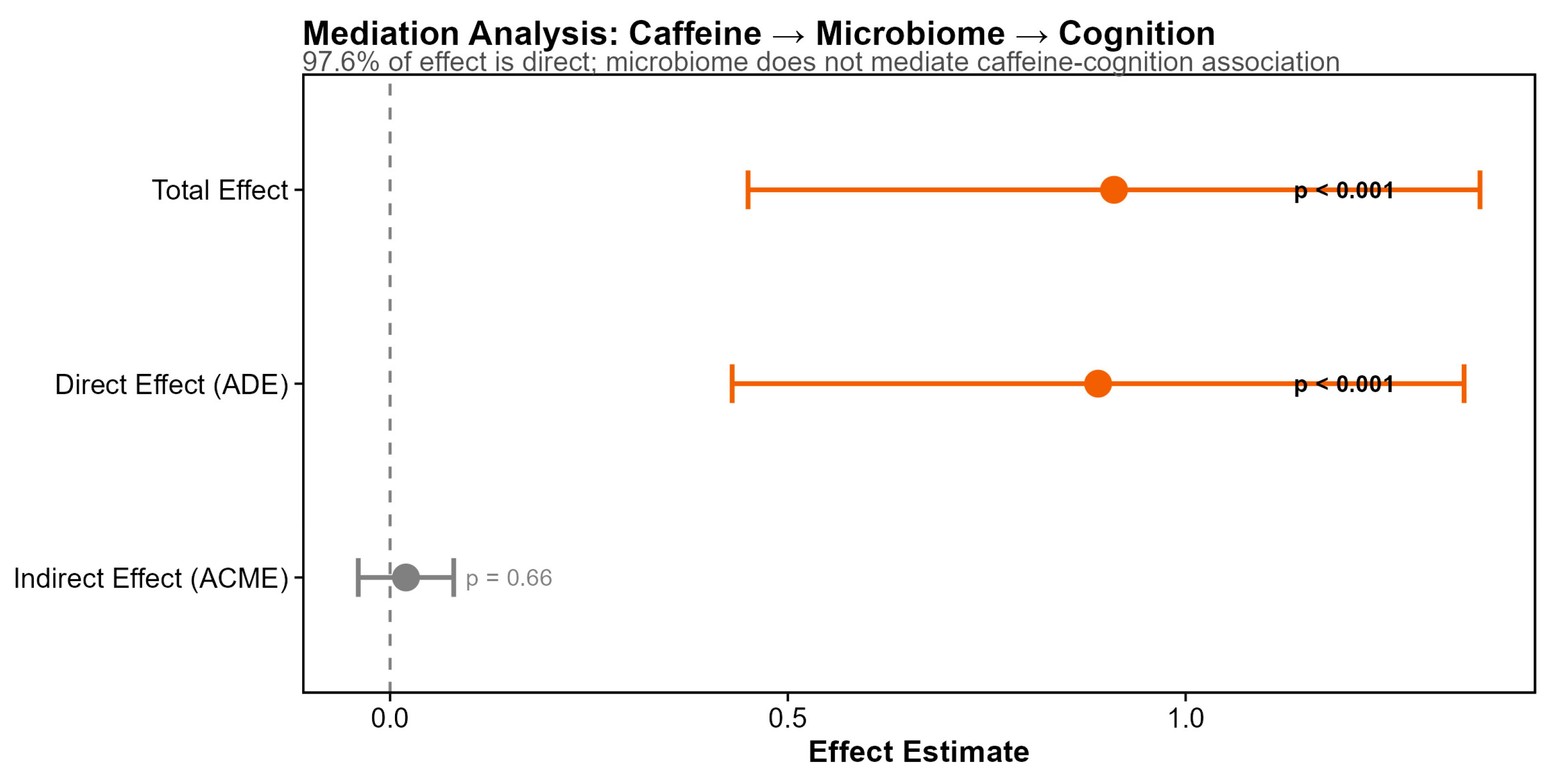

Formal mediation analysis tested whether the caffeine–cognition association was mediated through gut microbiome alpha diversity (

Figure 9). Using 1,000 bootstrap simulations with standardized coefficients, we found that the total effect of caffeine on cognition (standardized β = 0.91,

p < 0.001) was almost entirely attributable to the direct pathway (average direct effect = 0.89,

p < 0.001), with negligible mediation through gut microbiome diversity (average causal mediation effect = 0.02,

p = 0.66; proportion mediated = 2.4%, not significant) (

Figure 6). Secondary mediation analyses testing specific taxa also failed to identify significant mediation pathways, though one genus showed a trend (indirect effect

p = 0.082). These results indicate that caffeine's cognitive benefits in this cohort operate through direct neurological mechanisms rather than through modulation of the gut–brain axis.

4. Discussion

This study examined diet-microbiome associations in prostate cancer survivors with prior ADT exposure, with attention to effect modification by exercise, APOE genotype, and testosterone status. Three principal findings emerged. First, diet-microbiome associations are context-dependent: the significant MEDAS x Exercise interaction on alpha diversity (Shannon p = 0.0022) demonstrates that Mediterranean diet adherence has stronger positive associations with gut microbiome diversity in physically active individuals, supporting precision nutrition frameworks wherein dietary recommendations account for concurrent lifestyle factors. Second, diet quality shapes community membership rather than abundance dynamics: all three diet scores predicted Sorensen (presence/absence) but not Bray-Curtis (abundance-weighted) beta diversity, suggesting diet determines which taxa colonize rather than their relative abundances once established. Third, caffeine uniquely predicts cognitive function through direct pathways: among 297 dietary variables, only caffeine significantly predicted MoCA scores (p = 0.0009, q = 0.014), with mediation analysis confirming 97.6% of this effect operates independently of microbiome modulation.

The MEDAS x Exercise interaction suggests that exercise may prime the gut ecosystem to respond to dietary inputs, consistent with literature demonstrating that physical activity modulates gut microbiome composition through altered splanchnic blood flow, gut transit time, and systemic inflammation [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. The specificity of this interaction (significant for MEDAS but not HEI or MIND) may reflect the Mediterranean diet's characteristic substrates (monounsaturated fatty acids, fermentable fibers, polyphenols) being particularly responsive to exercise-induced physiological changes, whereas HEI and MIND capture broader diet quality constructs less mechanistically coupled to exercise pathways. This finding has direct clinical implications: dietary counseling for cancer survivors may be most effective when paired with exercise recommendations. A sedentary prostate cancer survivor may derive less microbiome benefit from improving Mediterranean diet adherence than one simultaneously engaging in resistance training or Tai Chi, suggesting that oncology dietitians and exercise physiologists should coordinate rather than deliver recommendations in isolation. Such integrated counseling aligns with emerging precision nutrition frameworks [

60].

The consistent pattern wherein all three diet scores predicted Sorensen but none predicted Bray-Curtis distance suggests a two-stage model: diet quality may primarily affect community membership by creating diverse ecological niches through varied fibers and polyphenols [

61], enabling specialist taxa to colonize, while relative abundances of established taxa may be determined by other factors including host genetics, immune function, or acute dietary variation. The finding that specific foods (meat/poultry/eggs: Bray-Curtis

p = 0.004) showed abundance associations, while aggregate diet scores did not, supports this interpretation, suggesting that particular dietary components, rather than overall diet quality, may drive abundance shifts. That said, alternative explanations warrant acknowledgment: Sorensen may simply have greater statistical power in sparse communities, and effect sizes were modest (

R2 = 1.9-2.3%). However, the consistency across all three diet scores strengthens confidence in this observation. If the two-stage interpretation holds, dietary optimization may be most effective at establishing beneficial taxa, with complementary approaches (targeted prebiotics or synbiotics) potentially needed to promote their outgrowth.

Caffeine emerged as the sole FDR-significant dietary predictor of cognitive function, likely reflecting its acute pharmacological effects (primarily adenosine receptor antagonism) detectable even cross-sectionally [

62], its well-documented neuroprotective properties [

63,

64,

65], and its high variance in this cohort (CV = 79.4%) providing statistical power despite limited MoCA variance. The mediation finding that caffeine's cognitive effects likely bypass the gut-brain axis, operating through direct neurological mechanisms [

66], is mechanistically informative and clinically relevant given that ADT is associated with cognitive impairment [

67,

68].

The null associations between diet pattern scores (MIND, MEDAS, HEI) and MoCA (all

p > 0.6) likely reflect methodological constraints rather than absence of true effects. The restricted MoCA range (11-21 vs. possible 0-30), universal cognitive impairment, and cross-sectional design severely limit power to detect cumulative dietary pattern effects typically observed in longitudinal studies [

40,

69]. That modifiable factors nonetheless predicted cognition (strength training in the parent study,

p = 0.007; caffeine here,

p = 0.0009) suggests that acute or proximal effects remain detectable where cumulative dietary pattern effects are not.

The identification of 129 genera with significant diet associations or diet x host factor interactions (q < 0.10) demonstrates that diet profoundly shapes taxonomic composition. Extensive effect modification by exercise (42-55 genera), APOE genotype (40-41 genera), and testosterone (34-51 genera) underscores that identical dietary patterns produce different microbiome responses depending on host context. The consistency of certain genera, including Phascolarctobacterium, Butyricimonas, and Sutterella, across all nine analysis categories identifies these taxa as particularly diet-responsive and potential targets for mechanistic studies or intervention monitoring.

Several limitations warrant consideration. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference; longitudinal studies with dietary interventions are needed to establish whether dietary patterns causally modify the microbiome. The sample size (n = 79) limits power for detecting smaller effects and complex interactions, and the E2 carrier subgroup (n = 7) is too small for reliable APOE e2-specific inference. Population specificity limits generalizability: our cohort of elderly men with prostate cancer and ADT exposure represents a unique hormonal and physiological context, and findings may not generalize to other cancer types, women, or younger individuals. Self-reported dietary data carry inherent recall bias and social desirability effects.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal validation to test whether cross-sectional associations predict changes over time, multi-omics integration (metagenomics, metabolomics) to strengthen mechanistic interpretation, randomized dietary intervention trials pairing Mediterranean diet with exercise, and expanded population studies to test replication across cancer types and demographic groups.

Overall, this analysis yields three translational insights. First, the MEDAS x Exercise interaction demonstrates that dietary effects on the gut microbiome depend on physical activity context, supporting integrated dietary-exercise counseling over siloed recommendations. Second, the Sorensen-Bray-Curtis dissociation suggests that, at least for this cohort, diet quality affects which taxa colonize rather than their relative abundances, with implications for intervention design. Third, multiple distinct pathways to cognitive support exist: strength training and caffeine both associate with better cognition through different mechanisms, offering complementary targets for survivorship care. Combined with evidence that APOE genotype and testosterone status condition microbiome responses to exercise, these findings motivate precision survivorship strategies integrating exercise prescriptions with genotype-, diet-, and hormone-informed monitoring.

5. Conclusions

The principal findings of this analysis establish several key patterns in diet–microbiome–cognition relationships among prostate cancer survivors with ADT exposure. First, the significant MEDAS × exercise interaction on alpha diversity (Shannon p = 0.0022) demonstrates that Mediterranean diet adherence shows stronger positive associations with gut microbiome diversity in physically active individuals compared to sedentary controls, supporting the hypothesis that physical activity may prime the gut ecosystem to respond to dietary inputs. Second, the consistent dissociation between beta diversity metrics – where all three diet quality scores significantly predicted Sørensen distance (all p < 0.035) but none predicted Bray-Curtis distance (all p > 0.15) – suggests that diet quality shapes community membership rather than abundance dynamics. Third, the extensive taxa-level findings, with 129 unique genera showing significant associations with diet scores or diet × host factor interactions (q < 0.10), demonstrate profound diet effects on gut microbial composition that are substantially modified by exercise, APOE genotype, and testosterone status. Fourth, among 297 dietary variables tested, only caffeine significantly predicted cognitive function after FDR correction (p = 0.0009, q = 0.014), with mediation analysis confirming that 97.6% of this effect operates through direct pathways rather than through microbiome modulation. Finally, despite theoretical expectations, the MIND, MEDAS, and HEI diet scores did not predict cognitive function in this cohort, a null finding likely attributable to MoCA range restriction and population homogeneity rather than absence of true diet–cognition relationships. Together, these findings support precision nutrition approaches in cancer survivorship that integrate dietary recommendations with exercise programming and account for individual host characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R. and T.J.S; methodology, J.R. and T.J.S.; software, T.J.S.; validation, J.R. and T.J.S.; formal analysis, J.R., K.D.K. and T.J.S.; investigation, J.R., A.O., K.D.K., A.P., N.R., .C., K.W.-S. and T.J.S.; resources, J.R., K.W.-S. and T.J.S.; data curation, C.G., K.D.K. and T.J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.; writing—review and editing, J.R., A.O., K.D.K., A.P., N.R., C.G., C.C., K.W.-S. and T.J.S.; visualization, T.J.S.; supervision, J.R., K.W.-S. and T.J.S.; project administration, J.R.; funding acquisition, J.R. and K.W.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a CCSG CPCP-2023-002 pilot project of the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute and NIA T32 AG055378.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Oregon Health & Science University (approval code: MOD00049193; approval date: 10 May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bower J, Ganz Pa, Tao M. Inflammatory biomarkers and fatigue during radiation therapy for breast and prostate cancer. . Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5534-40. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Von Ah D. Cancer-related cognitive impairment: updates to treatment, the need for more evidence, and impact on quality of life—a narrative review. Ann Pal Med. 2024;13:1265-80.

- Ettridge K, et al. Prostate cancer is far more hidden…”: Perceptions of stigma, social isolation and help-seeking among men with prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2018;27:e12790. [CrossRef]

- Raber J, Huang Y, Ashford J. ApoE genotype accounts for the vast majority of AD risk and AD pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:641-50. [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Holtzman D. Interplay between innate immunity and Alzheimer disease: APOE and TREM2 in the spotlight. Nature reviews Immunology. 2018;18:759-72. [CrossRef]

- Bancaro M, et al. Apolipoprotein E induces pathogenic senescent-like myeloid cells in prostate ca. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:602-19.

- Ahles T, Saykin A, Noll N, et al. The relationship of APOE genotype to neuropsychological performance in long-term cancer survivors treated with standard dose chemotherapy. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12:612-9. [CrossRef]

- V N, et al.. How to Treat Prostate Cancer With Androgen Deprivation and Minimize Cardiovascular Risk. JACC CardioOncol. 2021;3:737-41.

- Shim M, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy and risk of cognitive dysfunction in men with prostate cancer: is there a possible link? Prostate Int. 2022;10:68-74. [CrossRef]

- Janowsky JS, Oviatt SK, Orwoll ES. Testosterone influences spatial cognition in older men. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1994;108(2):325-32. PubMed PMID: 8037876.

- Janowsky JS, Chavez B, Orwoll E. Sex steroids modify working memory. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12:407-14. [CrossRef]

- Motlagh R, Quhal F, Mori K, Miura N, Aydh A, Laukhtina E, et al. The Risk of New Onset Dementia and/or Alzheimer Disease among Patients with Prostate Cancer Treated with Androgen Deprivation Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Urol. 2021;205:60-7. [CrossRef]

- Patel A, Friedenreich C, Moore S, et. al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Cancer Prevention and Control. Med Sci Sports Excercise. 2019;51:2391-402. [CrossRef]

- Bardia A, Arieas E, Zhang Z, et al. Comparison of breast cancer recurrence risk and cardiovascular disease incidence risk among postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:907-14. [CrossRef]

- Kaul S, Miller JG, Grayburn PA, Hashimoto S, Hibberd M, Holland MR, et al. A suggested roadmap for cardiovascular ultrasound research for the future. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24(4):455-64. Epub 2011/03/29. PubMed PMID: 21440216. [CrossRef]

- Perenigoni N, Zagato E, Calcinotto A, Troiani M, Pereira Mestre R, Cali B, et al. Commensal bacteria promote endocrine resistance in prostate cancer through androgen biosynthesis. Science. 2021;374:216-24. [CrossRef]

- Afzaal M, et al. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front Microbol. 2022;10:3389.

- Niemi M, Hakkinen T, Karttunen T, Eskelinen S, Kervinen K, Savolainen M, et al. Apolipoprotein E and colon cancer: Expression in normal and malignant human intestine and effect on cultured human colonic adenocarcinoma cells. Eur J Intern Med. 2002;13:37-43.

- Tran T, Corsini S, Kellinggray L, Hegarty C, Le Gail C, Narbad A, et al. APOE genotype influences the gut microbiome structure and function in humans and mice: relevance for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. FASEB J. 2019;33:8221-31. [CrossRef]

- Pencheva N, Tran H, Buss C, et al. Convergent Multi-miRNA Targeting of ApoE Drives LRP1/LRP8-Dependent Melanoma Metastasis and Angiogenesis. Cell. 2012;151:1068-82. [CrossRef]

- Ostndorf B, Bilanovic J, Adaku N, et al. Common germline variants of the human APOE gene modulate melanoma progression and survival. Nat Med. 2020;26:1048-53. [CrossRef]

- Lucy M, Allen J, Buford T, Fields C, Woods J. Exercise and the Gut Microbiome: A Review of the Evidence, Potential Mechanisms, and Implications for Human Health. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2019;47:75-89. [CrossRef]

- Clauss M, Gerard P, Mosca A, Leclerc M. Interplay Between Exercise and Gut Microbiome in the Context of Human Health and Performance. Front Nutr. 2021;8:637010. [CrossRef]

- Raber J, O’Niel A, Kasschau K, Pederson A, Robinson N, Guidarelli C, et al. Exercise, APOE genotype, and testosterone modulate gut microbiome-cognition associations in prostate cancer survivors. Genes. 2025;16:1507. [CrossRef]

- Tilg H, Kaser A. Gut microbiome, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2126-32. [CrossRef]

- Ohland C, Kish L, Bell HC, Thiesen A, Hotte N, Pankiv E, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus helveticus on murine behavior are dependent on diet and genotype and correlate with alterations in the gut microbiome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1738-47. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda S, Ohno H. Gut microbiome and metabolic diseases. Seminars in immunopathology. 2014;36:103-14.

- Hatch A, Horne JA, Toma R, Twibell B, Somerville K, Pelle B, et al. A Robust Metatranscriptomic Technology for Population-Scale Studies of Diet, Gut Microbiome, and Human Health. Int J Genomics. 2019;2019:1718741. [CrossRef]

- Koblinsky N, Power K, Middleton L, Ferland G, Anderson N. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Diet and Exercise Effects on Cognition: A Review of the Intervention Literature. J Gerontol. 2023;78:195-205. [CrossRef]

- NCI. Diet History Questionnaire III. https://epigrantscancergov/dhq3/. 2025.

- Fransen H, Ocke M. Indices of diet quality. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:559-65. [CrossRef]

- Kourlaba G, Panagiotakos D. Dietary quality indicaes and human health: a review. Maturitas. 2009;62:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Perrone P, D’Angelo S. Gut Microbiota Modulation Through Mediterranean Diet Foods: Implications for Human Health. Nutrients. 2025;17:948. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Yang B, Liu Q, Gao M, Luo M. The long-term neuroprotective effect of MIND and Mediterranean diet on patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2025;15:32725. [CrossRef]

- Lin P-H, Burwell A, Giovannucc E, et al. Dietary patterns in prostate cancer prevention and management: A systematic review of prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials. Eur Urol. 2025;88:571-88. [CrossRef]

- Winters-Stone K, Lyons K, Dieckmann N, Lee C, Mitri Z, Beer T. Study protocol for the Exercising Together© trial: a randomized, controlled trial of partnered exercise for couples coping with cancer. Trials. 2021;22:579. [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine Z, Phillips N, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Ger Soc. 2005;53:695-9. [CrossRef]

- Schröder H, Fitó M, Estruch R, et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr. 2011;141:1140-5. [CrossRef]

- Krebs-Smith S, Pannucci T, Subar A, et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2015. J Acad Nutr Diet. . J Acad Nutr Diettetics. 2018;118:1591-602. [CrossRef]

- Morris M, Tangney C, Wang Y, et al. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer's disease. . Alzheimer Dement. 2015;11:1007-14. [CrossRef]

- Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. . J Stat Software. 2010;33:1-22. [CrossRef]

- Callahan B, McDurdie P, Rosen M, AW H, Johnson A, Holmes S. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Meth. 2016;13:581-3.

- Martin M. Cutadept removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequences reads. EMBnet J. 2011;17:10-2. [CrossRef]

- Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nuc Acids Res. 2013;41(D1):D590-D6.

- Price M, Dehal P, Arkin A. FastTree 2 – Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLOSOne. 2010;5:e9490. [CrossRef]

- McMurdie P, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. . PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61217. [CrossRef]

- Cribari-Neto F, Zeileis A. Beta regression in R. . J Stat Software. 2010;34:1-24.

- Oksanen J, Simpson G, Blanchet F, et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-4. . https://CRANR-projectorg/package=vegan. 2022.

- Anderson M. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26:32-46.

- Mallick H, Rahnavard A, McIver L, et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17:e1009442. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Statist Soc Ser B (Methodological). 1995;57:289-300. [CrossRef]

- Tingley D, Yamamori T, Hirose K, Keele L, Imai K. mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. . J Stat Software. 2014;59:1-38.

- Mailing L, Allen J, Buford T, Fields T, Woods J. Exercise and the gut microbiome: a review of the evidence, potential mechanisms, and implications for human health. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2019;47:75-85. [CrossRef]

- Clauss M, Gerard P, Mosca A, Leclerc M. Interplay between exercise and gut microbiome in the context of human health and performance. . Front Nutr. 2021;8:637010. [CrossRef]

- Mohr A, Jager R, Carpenter K, et al. The athletic gut microbiota. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2020;17:24. [CrossRef]

- ter Steege R, Kolkman J. Review article: the pathophysiology and management of gastrointestinal symptoms during physical exercise, and the role of splanchnic blood flow. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:516-28. [CrossRef]

- De Schryver A, Keulemans Y, Peters H, et al. Effects of regular physical activity on defecation pattern in middle-aged patients complaining of chronic constipation. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2005;40:422-9. [CrossRef]

- Petersen A, Pedersen B. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1154-62.

- Codella R, Luzi L, Terruzi I. Exercise has the guts: how physical activity may positively modulate gut microbiota in chronic and immune-based diseases. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:331-41. [CrossRef]

- Zeevi D, Korem T, Zmore N, al e. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. . Cell. 2015;163:1079-94. [CrossRef]

- Zmora N, Suez J, Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. . Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2019;16:35-56. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro J, Sebastiao AM. Caffeine and adenosine. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 1):S3-S15.

- Eskelinen M, Kivipelto M. Caffeine as a protective factor in dementia and Alzheimer's disease. JAlzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl):S167-S74. [CrossRef]

- Santos C, Costa J, Santos J, Vaz-Carneiro A, Lunet N. Caffeine intake and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 1):S187-S204. [CrossRef]

- Nehlig A. Is caffeine a cognitive enhancer? . J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 1):S85-S94.

- Cunha R, Agostinho P. Chronic caffeine consumption prevents memory disturbance in different animal models of memory decline. . J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 1):S95-S116. [CrossRef]

- Nead K, Gaskin G, Chester C, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy and future Alzheimer's disease risk. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:566-71. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez B, Jim H, Booth-Jones M, al e. Course and predictors of cognitive function in patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen-deprivation therapy: a controlled comparison. . J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2021-7. [CrossRef]

- Morris M, Tangney C, Wang Y, al. e. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimer Dement. 2015;11:1015-22. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Diet Score Distributions in Prostate Cancer Survivors. Distribution of diet quality scores among study participants (N = 79). **(A)** Mediterranean Diet Adherence Score (MEDAS; possible range 0–13); mean = 3.6, indicating relatively low Mediterranean diet adherence with the cohort utilizing 54% of the possible score range. **(B)** Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015; possible range 0–100); mean = 73.6, exceeding the US national average (~59, green dotted line). **(C)** MIND diet score (possible range 0–15); mean = 7.4, consistent with published values in older adult populations. **(D)** Correlation scatterplot showing positive associations among diet scores (HEI-MIND: r = 0.74; HEI-MEDAS: r = 0.42; MEDAS-MIND: r = 0.63), indicating convergent validity while measuring distinct dietary aspects. Dashed lines indicate cohort means.

Figure 1.

Diet Score Distributions in Prostate Cancer Survivors. Distribution of diet quality scores among study participants (N = 79). **(A)** Mediterranean Diet Adherence Score (MEDAS; possible range 0–13); mean = 3.6, indicating relatively low Mediterranean diet adherence with the cohort utilizing 54% of the possible score range. **(B)** Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015; possible range 0–100); mean = 73.6, exceeding the US national average (~59, green dotted line). **(C)** MIND diet score (possible range 0–15); mean = 7.4, consistent with published values in older adult populations. **(D)** Correlation scatterplot showing positive associations among diet scores (HEI-MIND: r = 0.74; HEI-MEDAS: r = 0.42; MEDAS-MIND: r = 0.63), indicating convergent validity while measuring distinct dietary aspects. Dashed lines indicate cohort means.

Figure 2.

Cognitive Function Distribution in Study Cohort Distribution of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores among study participants (N = 78 with available data). Scores ranged from 11 to 21 (mean = 16.7), representing only one-third of the possible score range (0–30). Green dashed line indicates normal cognition cutoff (≥26); no participants scored in the normal range. Orange dashed line indicates mild cognitive impairment (MCI) cutoff (<18); 61.5% of participants (n = 48) scored in the moderate impairment range (10–17), while 38.5% (n = 30) met criteria for MCI (18–25). This restricted variance reflects the cognitive effects of androgen deprivation therapy in this cancer survivor population.

Figure 2.

Cognitive Function Distribution in Study Cohort Distribution of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores among study participants (N = 78 with available data). Scores ranged from 11 to 21 (mean = 16.7), representing only one-third of the possible score range (0–30). Green dashed line indicates normal cognition cutoff (≥26); no participants scored in the normal range. Orange dashed line indicates mild cognitive impairment (MCI) cutoff (<18); 61.5% of participants (n = 48) scored in the moderate impairment range (10–17), while 38.5% (n = 30) met criteria for MCI (18–25). This restricted variance reflects the cognitive effects of androgen deprivation therapy in this cancer survivor population.

Figure 3.

Mediterranean Diet × Exercise Interaction on Gut Microbiome Alpha Diversity. Association between Mediterranean Diet Adherence Score (MEDAS) and Shannon diversity index stratified by exercise intervention group (N = 75 with complete data). The significant interaction (p = 0.0022; FDR q = 0.012) indicates that Mediterranean diet adherence shows stronger positive associations with microbiome diversity in physically active groups (Strength training: blue; Tai Chi: green) compared to the sedentary control group (Flexibility: orange). Points represent individual participants; lines represent linear regression fits with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Mediterranean Diet × Exercise Interaction on Gut Microbiome Alpha Diversity. Association between Mediterranean Diet Adherence Score (MEDAS) and Shannon diversity index stratified by exercise intervention group (N = 75 with complete data). The significant interaction (p = 0.0022; FDR q = 0.012) indicates that Mediterranean diet adherence shows stronger positive associations with microbiome diversity in physically active groups (Strength training: blue; Tai Chi: green) compared to the sedentary control group (Flexibility: orange). Points represent individual participants; lines represent linear regression fits with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4.

MEDAS × Exercise Interaction Across Alpha Diversity Metrics. Association between Mediterranean Diet Adherence Score (MEDAS) and additional alpha diversity metrics stratified by exercise intervention group. **(A)** Simpson diversity index (interaction p = 0.023). **(B)** Observed ASV richness (interaction p = 0.035). The consistent interaction pattern across all three alpha diversity metrics (Shannon, Simpson, Observed) provides robust evidence that Mediterranean diet effects on gut microbiome diversity depend on physical activity status.

Figure 4.

MEDAS × Exercise Interaction Across Alpha Diversity Metrics. Association between Mediterranean Diet Adherence Score (MEDAS) and additional alpha diversity metrics stratified by exercise intervention group. **(A)** Simpson diversity index (interaction p = 0.023). **(B)** Observed ASV richness (interaction p = 0.035). The consistent interaction pattern across all three alpha diversity metrics (Shannon, Simpson, Observed) provides robust evidence that Mediterranean diet effects on gut microbiome diversity depend on physical activity status.

Figure 5.

Constrained Ordinations Reveal Metric-Specific Diet–Beta Diversity Associations. Canonical Analysis of Principal Coordinates (CAP; also termed distance-based redundancy analysis, db-RDA) comparing diet score associations with presence/absence (Sørensen) versus abundance-weighted (Bray-Curtis) beta diversity. **Top row:** Sørensen distance ordinations showing significant associations for all three diet scores (HEI-2015 p = 0.002, MIND p = 0.025, MEDAS p = 0.034). **Bottom row:** Bray-Curtis distance ordinations showing non-significant associations for all diet scores (HEI-2015 p = 0.159, MIND p = 0.494, MEDAS p = 0.321). Points represent individual participants (n = 69 with complete data), colored by standardized diet score (plasma color scale). The biplot vector in each panel indicates the direction and relative magnitude of the diet score loading in ordination space. PERMANOVA p-values are displayed in the lower right of each panel (significant values in bold green, non-significant in gray). Axis labels show percent of total variance explained by each constrained axis. All models adjusted for exercise intervention and *APOE* genotype. This dissociation between distance metrics suggests that diet quality shapes community membership (which taxa are present) rather than relative abundance patterns (how much of each taxon), consistent with a model where plant-rich diets provide diverse substrates that enable specialist taxa to colonize without preferentially fueling blooms of particular organisms.

Figure 5.

Constrained Ordinations Reveal Metric-Specific Diet–Beta Diversity Associations. Canonical Analysis of Principal Coordinates (CAP; also termed distance-based redundancy analysis, db-RDA) comparing diet score associations with presence/absence (Sørensen) versus abundance-weighted (Bray-Curtis) beta diversity. **Top row:** Sørensen distance ordinations showing significant associations for all three diet scores (HEI-2015 p = 0.002, MIND p = 0.025, MEDAS p = 0.034). **Bottom row:** Bray-Curtis distance ordinations showing non-significant associations for all diet scores (HEI-2015 p = 0.159, MIND p = 0.494, MEDAS p = 0.321). Points represent individual participants (n = 69 with complete data), colored by standardized diet score (plasma color scale). The biplot vector in each panel indicates the direction and relative magnitude of the diet score loading in ordination space. PERMANOVA p-values are displayed in the lower right of each panel (significant values in bold green, non-significant in gray). Axis labels show percent of total variance explained by each constrained axis. All models adjusted for exercise intervention and *APOE* genotype. This dissociation between distance metrics suggests that diet quality shapes community membership (which taxa are present) rather than relative abundance patterns (how much of each taxon), consistent with a model where plant-rich diets provide diverse substrates that enable specialist taxa to colonize without preferentially fueling blooms of particular organisms.

Figure 6.

Consolidated Diet-Taxa Associations and Interactions (129 unique genera). Columns: Main effects (MEDAS: 41, HEI: 49, MIND: 39 significant genera) followed by Diet × Exercise interactions (6 columns) and Diet × ApoE interactions (6 columns). Color = coefficient from MaAsLin2 NEGBIN models (red = positive, blue = negative). Gray cells = not significant (q ≥ 0.1). Asterisks: * q < 0.1, ** q < 0.01, *** q<0.001.

Figure 6.

Consolidated Diet-Taxa Associations and Interactions (129 unique genera). Columns: Main effects (MEDAS: 41, HEI: 49, MIND: 39 significant genera) followed by Diet × Exercise interactions (6 columns) and Diet × ApoE interactions (6 columns). Color = coefficient from MaAsLin2 NEGBIN models (red = positive, blue = negative). Gray cells = not significant (q ≥ 0.1). Asterisks: * q < 0.1, ** q < 0.01, *** q<0.001.

Figure 7.

Positive association between daily caffeine intake and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score (N = 73 with complete data). Caffeine was the only dietary variable (of 297 tested) to achieve significance after FDR correction (β = +0.0047 per mg; p = 0.0009; FDR q = 0.014). The effect size corresponds to approximately 0.5 MoCA points per 100 mg daily caffeine (~1 cup of coffee). Points represent individual participants; line represents linear regression fit with 95% confidence interval.

Figure 7.

Positive association between daily caffeine intake and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score (N = 73 with complete data). Caffeine was the only dietary variable (of 297 tested) to achieve significance after FDR correction (β = +0.0047 per mg; p = 0.0009; FDR q = 0.014). The effect size corresponds to approximately 0.5 MoCA points per 100 mg daily caffeine (~1 cup of coffee). Points represent individual participants; line represents linear regression fit with 95% confidence interval.

Figure 9.

Mediation Analysis: Caffeine Effects on Cognition Are Direct Results of formal mediation analysis testing whether the caffeine-cognition association is mediated through gut microbiome alpha diversity (1,000 bootstrap simulations). The Average Direct Effect (ADE = 0.89; p < 0.001) was highly significant, while the Average Causal Mediation Effect (ACME = 0.02; p = 0.66) was not significant. The proportion mediated (2.4%) indicates that 97.6% of caffeine's association with cognition operates through direct pathways, with negligible mediation through gut microbiome diversity.

Figure 9.

Mediation Analysis: Caffeine Effects on Cognition Are Direct Results of formal mediation analysis testing whether the caffeine-cognition association is mediated through gut microbiome alpha diversity (1,000 bootstrap simulations). The Average Direct Effect (ADE = 0.89; p < 0.001) was highly significant, while the Average Causal Mediation Effect (ACME = 0.02; p = 0.66) was not significant. The proportion mediated (2.4%) indicates that 97.6% of caffeine's association with cognition operates through direct pathways, with negligible mediation through gut microbiome diversity.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |