Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

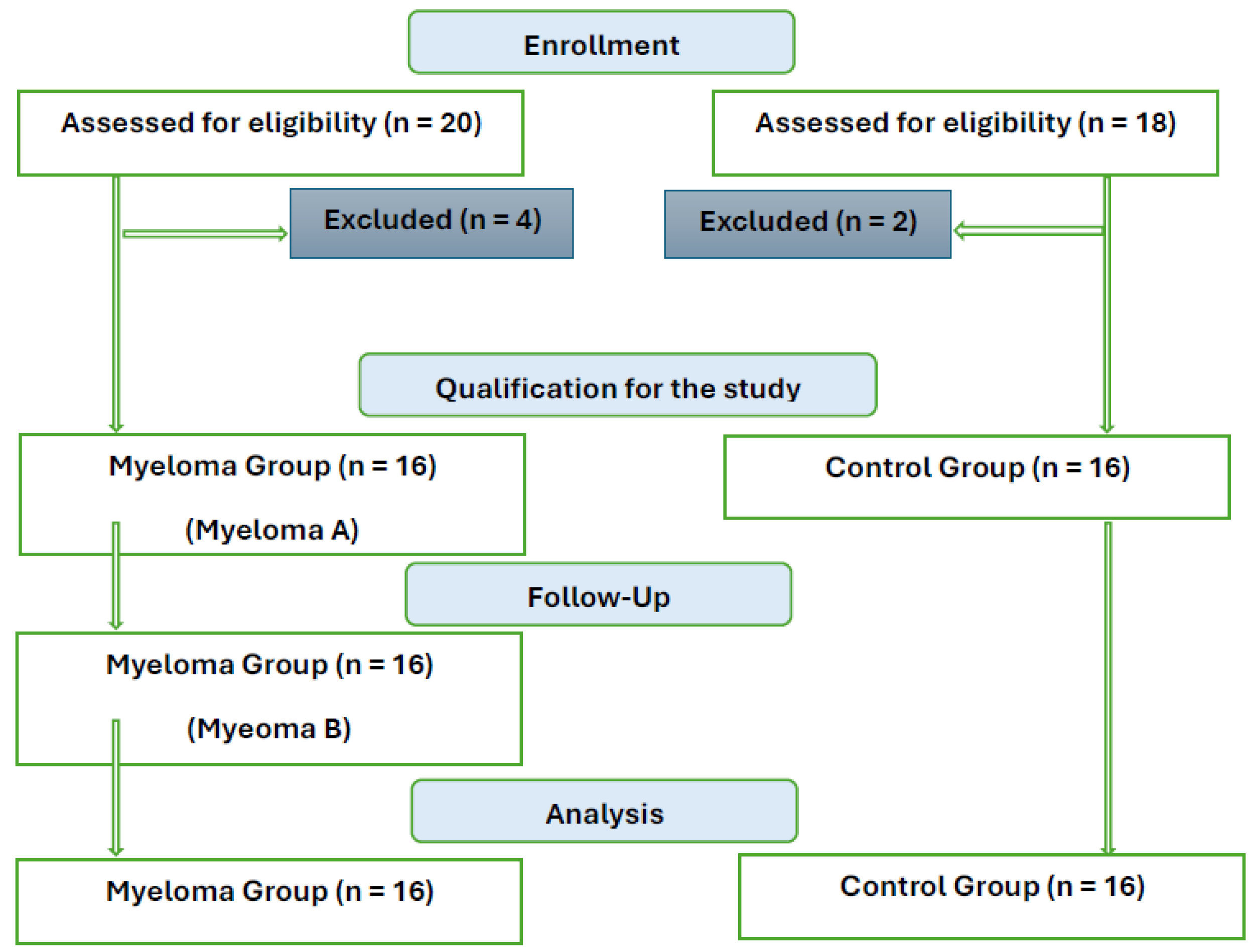

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Patient Group and Healthy Controls

2.2. Nordic Walking Training Protocol

2.3. Time Restricted Eating

2.4. Stool Collection, DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.5. Sequencing and Bioinformatics

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

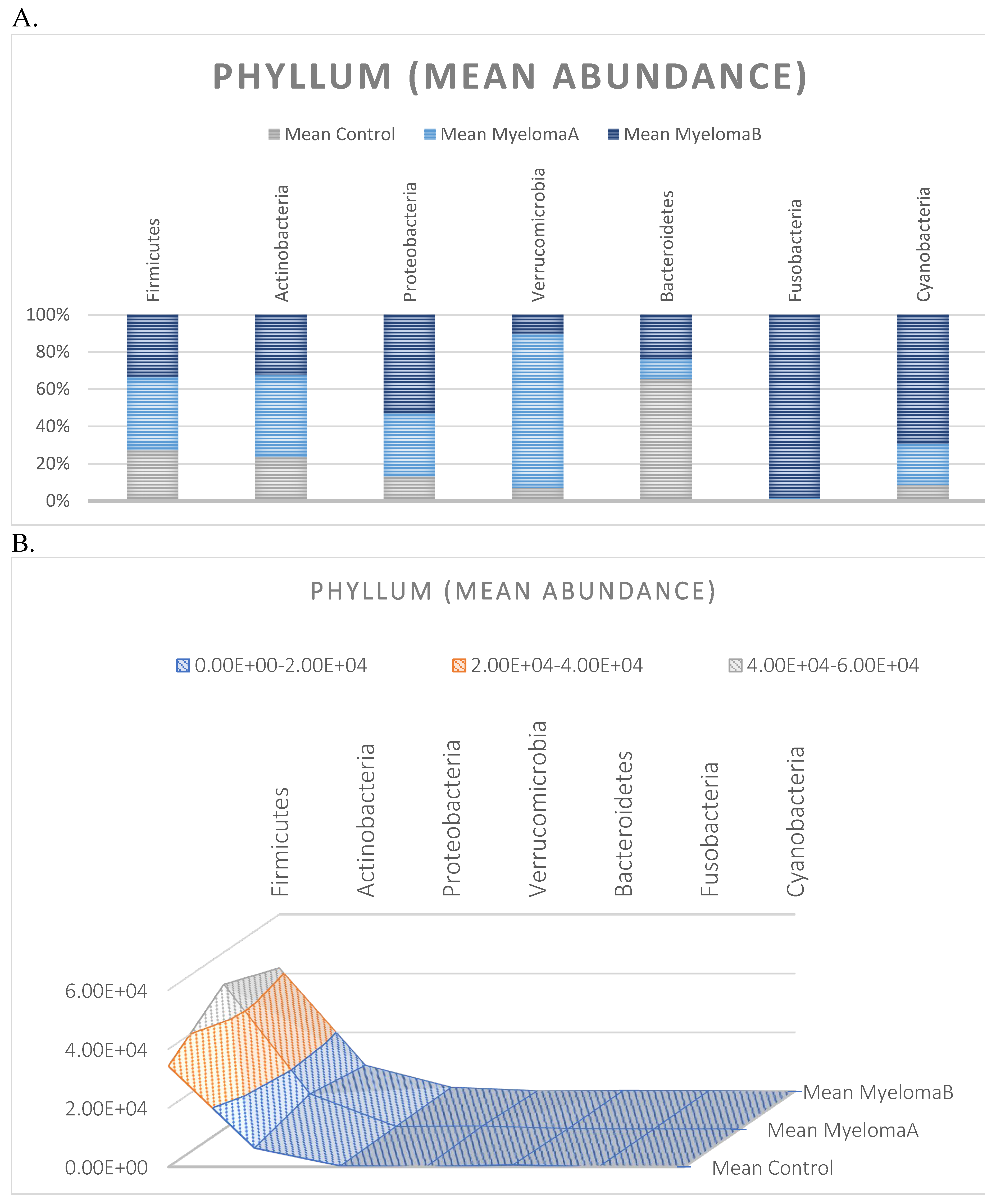

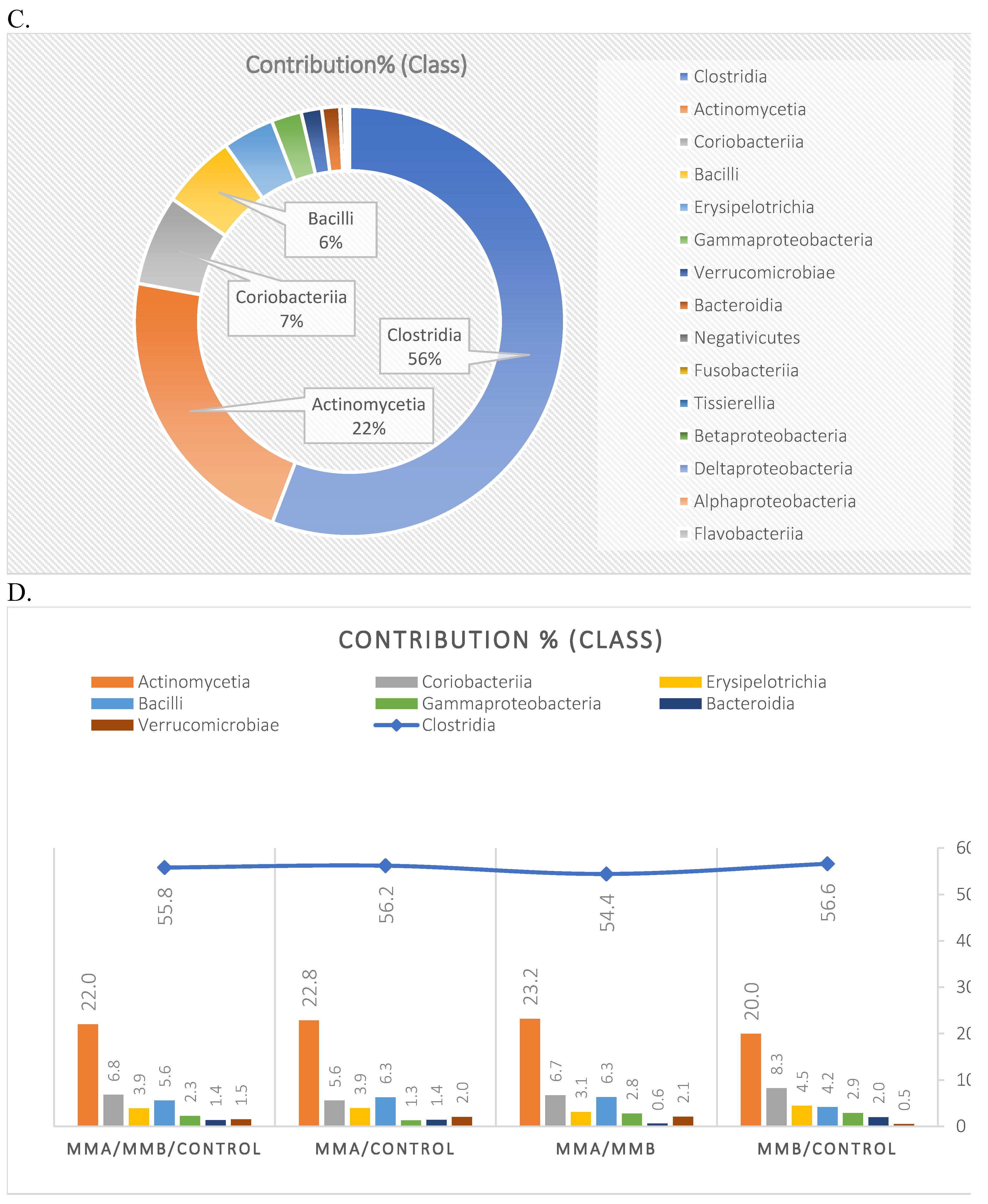

3.1. Microbiota Composition Diversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Belkum, A.; Broadwell, D.; Lovern, D.; Petersen, L.; Weinstock, G.; Dunne, W.M. Proteomics and Metabolomics for Analysis of the Dynamics of Microbiota. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2018, 15, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manrique, P.; Bolduc, B.; Walk, S.T.; Van Oost, J. Der; De Vos, W.M.; Young, M.J. Healthy Human Gut Phageome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10400–10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.; Weese, J.S. Methods and Basic Concepts for Microbiota Assessment. Vet. J. 2019, 249, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerdá, B.; Pérez, M.; Pérez-Santiago, J.D.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; González-Soltero, R.; Larrosa, M. Gut Microbiota Modification: Another Piece in the Puzzle of the Benefits of Physical Exercise in Health? Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressa, C.; Bailén-Andrino, M.; Pérez-Santiago, J.; González-Soltero, R.; Pérez, M.; Montalvo-Lominchar, M.G.; Maté-Muñoz, J.L.; Domínguez, R.; Moreno, D.; Larrosa, M. Differences in Gut Microbiota Profile between Women with Active Lifestyle and Sedentary Women. PLoS One 2017, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, S.; Bonavolontà, V.; Poli, L.; Clemente, F.M.; De Candia, M.; Carvutto, R.; Silva, A.F.; Badicu, G.; Greco, G.; Fischetti, F. The Relationship between Physical Activity, Physical Exercise, and Human Gut Microbiota in Healthy and Unhealthy Subjects: A Systematic Review. Biology (Basel). 2022, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, G.; Ho, J.W.K. Challenges and Emerging Systems Biology Approaches to Discover How the Human Gut Microbiome Impact Host Physiology. Biophys. Rev. 2020, 12, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huminska-Lisowsk, K.; Zielinska, K.; Mieszkowski, J.; Michalowska-Sawczy, M.; Cieszczyk, P.; Labaj, P.P.; Wasag, B.; Fraczek, B.; Grzywacz, A.; Kochanowicz, A.; et al. Microbiome Features Associated with Performance Measures in Athletic and Nonathletic Individuals: A Case-Control Study. PLoS One 2024, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine Pepeljugoski, C.; Morgan, G.; Braunstein, M. Analysis of Intestinal Microbiome in Multiple Myeloma Reveals Progressive Dysbiosis Compared to MGUS and Healthy Individuals. Blood 2019, 134, 3076–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, M.; Biliński, J.; Basak, G.W. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Pathogenesis, Biology, and Treatment of Plasma Cell Dyscrasias. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Gut Microbiome in Multiple Myeloma: Mechanisms of Progression and Clinical Applications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares, M.; Hermouet, S. Editorial: The Role of Microorganisms in Multiple Myeloma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, X.; Zhu, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lei, Q.; Xia, J.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; He, Y.; et al. Alterations of Gut Microbiome Accelerate Multiple Myeloma Progression by Increasing the Relative Abundances of Nitrogen-Recycling Bacteria. Microbiome 2020, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Gu, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, B.; Li, J. Fecal Microbiota Taxonomic Shifts in Chinese Multiple Myeloma Patients Analyzed by Quantitative Polimerase Chain Reaction (QPCR) and 16S RRNA High-Throughput Sequencing. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 8269–8280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, N.; Tavitian, E.; Mastey, D.; Lengfellner, J.; Hevroni, G.; Zarski, A.; Salcedo, M.; Mailankody, S.; Hassoun, H.; Smith, E.L.; et al. Association of Patient Activity Bio-Profiles with Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 57, 101854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, F.; Osaili, T.; Obaid, R.S.; Naja, F.; Radwan, H.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; Hasan, H.; Hashim, M.; Alam, I.; Sehar, B.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Time-Restricted Feeding/Eating: A Targeted Biomarker and Approach in Precision Nutrition. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwińska-Ledwig, O.; Kryst, J.; Ziemann, E.; Borkowska, A.; Reczkowicz, J.; Dzidek, A.; Rydzik, Ł.; Pałka, T.; Żychowska, M.; Kupczak, W.; et al. The Beneficial Effects of Nordic Walking Training Combined with Time-Restricted Eating 14/24 in Women with Abnormal Body Composition Depend on the Application Period. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortas, J.A.; Reczkowicz, J.; Juhas, U.; Ziemann, E.; Świątczak, A.; Prusik, K.; Olszewski, S.; Soltani, N.; Rodziewicz-Flis, E.; Flis, D.; et al. Iron Status Determined Changes in Health Measures Induced by Nordic Walking with Time-Restricted Eating in Older Adults– a Randomised Trial. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwińska-Ledwig, O.; Żychowska, M.; Jurczyszyn, A.; Kryst, J.; Deląg, J.; Borkowska, A.; Reczkowicz, J.; Pałka, T.; Bujas, P.; Piotrowska, A. The Impact of a 6-Week Nordic Walking Training Cycle and a 14-Hour Intermittent Fasting on Disease Activity Markers and Serum Levels of Wnt Pathway-Associated Proteins in Patients with Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nes, B.M.; Janszky, I.; Wisløff, U.; Støylen, A.; Karlsen, T. Age-Predicted Maximal Heart Rate in Healthy Subjects: The HUNT Fitness Study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2013, 23, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLARKE, K.R. Non-parametric Multivariate Analyses of Changes in Community Structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrêne, M.; Legendre, P. Species Assemblages and Indicator Species: The Need for a Flexible Asymmetrical Approach. Ecol. Monogr. 1997, 67, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, J.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Bulló, M.; Lopez, J.V.; Corella, D.; Castañer, O.; Vidal, J.; Atzeni, A.; Fernandez-García, J.C.; Torres-Collado, L.; et al. Effect on Gut Microbiota of a 1-y Lifestyle Intervention with Mediterranean Diet Compared with Energy-Reduced Mediterranean Diet and Physical Activity Promotion: PREDIMED-Plus Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the Human Gut Microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’angelo, G. Microbiota and Hematological Diseases. Int. J. Hematol. Stem Cell Res. 2022, 16, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftciler, R.; Ciftciler, A.E. The Importance of Microbiota in Hematology. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2022, 61, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianko, M.J.; Devlin, S.M.; Littmann, E.R.; Chansakul, A.; Mastey, D.; Salcedo, M.; Fontana, E.; Ling, L.; Tavitian, E.; Slingerland, J.B.; et al. Minimal Residual Disease Negativity in Multiple Myeloma Is Associated with Intestinal Microbiota Composition. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 2040–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwińska-Ledwig, O.; Jurczyszyn, A.; Piotrowska, A.; Pilch, W.; Antosiewicz, J.; Żychowska, M. The Effect of a Six-Week Nordic Walking Training Cycle on Oxidative Damage of Macromolecules and Iron Metabolism in Older Patients with Multiple Myeloma in Remission—Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwińska-Ledwig, O.; Gradek, J.; Deląg, J.; Jurczyszyn, A. The Effect of a 6-Week Nordic Walking Training Cycle on Myeloma-Related Blood Parameters, Vitamin 25(OH)D3 Serum Concentration and Peripheral Polyneuropathy Symptoms in Patients with Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021, 21, S114–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewiecka, H.; Buttar, H.S.; Kasperska, A.; Ostapiuk–Karolczuk, J.; Domagalska, M.; Cichoń, J.; Skarpańska-Stejnborn, A. Physical Activity Induced Alterations of Gut Microbiota in Humans: A Systematic Review. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomini-Gnutzmann, R.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Jorquera-Aguilera, C.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, F. Effect of Intensity and Duration of Exercise on Gut Microbiota in Humans: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, E.; Yokoyama, H.; Imai, D.; Takeda, R.; Ota, A.; Kawai, E.; Hisada, T.; Emoto, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Okazaki, K. Aerobic Exercise Training with Brisk Walking Increases Intestinal Bacteroides in Healthy Elderly Women. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlandson, K.M.; Liu, J.; Johnson, R.; Dillon, S.; Jankowski, C.M.; Kroehl, M.; Robertson, C.E.; Frank, D.N.; Tuncil, Y.; Higgins, J.; et al. An Exercise Intervention Alters Stool Microbiota and Metabolites among Older, Sedentary Adults. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczyńska-Zając, J.M.; Malinowska, A.; Łagowska, K.; Leciejewska, N.; Bajerska, J. The Effects of Time-Restricted Eating and Ramadan Fasting on Gut Microbiota Composition: A Systematic Review of Human and Animal Studies. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 82, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gerdel, T.; Camargo, M.; Alvarado, M.; Ramírez, J.D. Impact of Intermittent Fasting on the Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review. Adv. Biol. 2023, 7, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paukkonen, I.; Törrönen, E.N.; Lok, J.; Schwab, U.; El-Nezami, H. The Impact of Intermittent Fasting on Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review of Human Studies. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, A.E.; Sweazea, K.L.; Bowes, D.A.; Jasbi, P.; Whisner, C.M.; Sears, D.D.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R.; Jin, Y.; Gu, H.; Klein-Seetharaman, J.; et al. Gut Microbiome Remodeling and Metabolomic Profile Improves in Response to Protein Pacing with Intermittent Fasting versus Continuous Caloric Restriction. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Mean | SD | Independent Samples T-Test | |||

| BH [cm] | CG | 165.56 | 9.02 | 0.497 | ||

| MM | 163.27 | 11.16 | ||||

| BM [kg] | CG | 81.36 | 9.09 | 0.598 | ||

| MM | 80.24 | 13.31 | ||||

| LBM [kg] | CG | 49.79 | 5.51 | 0.734 | ||

| MM | 51.72 | 10.36 | ||||

| SLM [kg] | CG | 45.25 | 5.02 | 0.651 | ||

| MM | 47.42 | 9.78 | ||||

| TBW [%] | CG | 44.32 | 1.29 | 0.270 | ||

| MM | 46.19 | 4.62 | ||||

| BMI | CG | 29.64 | 2.60 | 0.836 | ||

| MM | 30.07 | 3.54 | ||||

| Body fat [%] | CG | 38.89 | 2.03 | <0.001* | ||

| MM | 30.84 | 3.27 | ||||

| Age [years] | CG | 62.19 | 5.40 | 0.070 | ||

| MM | 65.00 | 5.13 | ||||

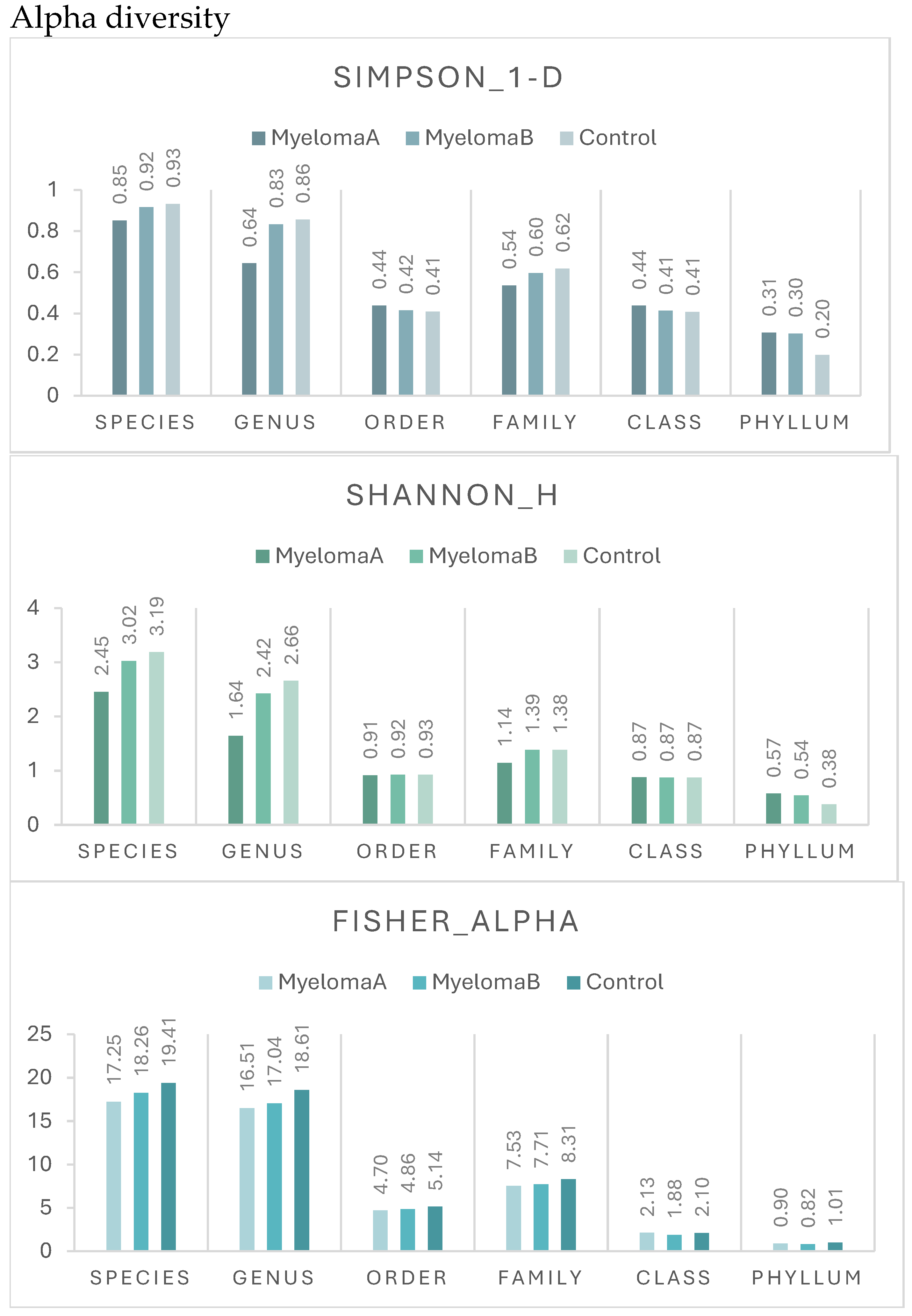

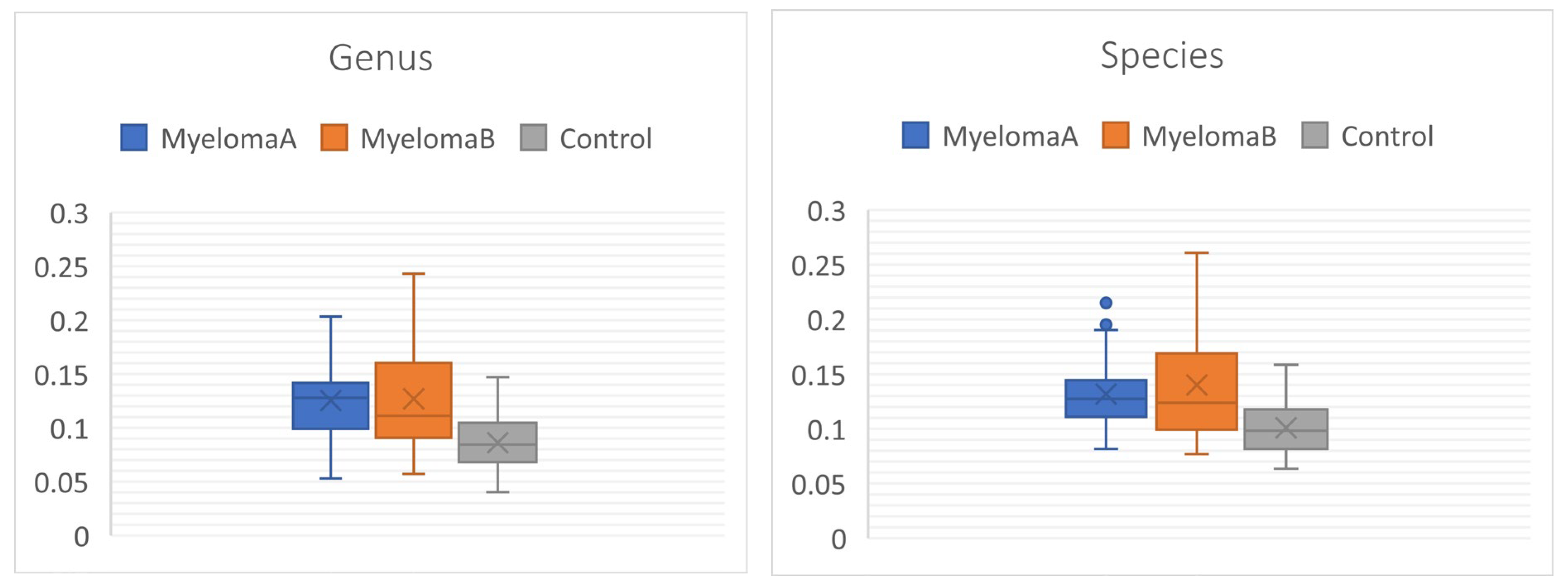

| ALPHA DIVERSITY | ||||

| Kruskal-Wallis test for equal (p) | Mann-Whitney pairwise (p) | |||

| Indeks | MMA-MMB | MMA-CG | MMB-CG | |

| Species | ||||

| Simpson_1-D | 0.004* | 0.300 | 0.002* | 0.519 |

| Shannon_H | 0.002* | 0.378 | 0.001* | 0.428 |

| Fisher_alpha | 0.031* | 1.000 | 0.050* | 0.127 |

| Genus | ||||

| Simpson_1-D | 0.012* | 0.472 | 0.006* | 0.948 |

| Shannon_H | 0.005* | 0.378 | 0.003* | 0.428 |

| Fisher_alpha | 0.012* | 0.472 | 0.006* | 0.948 |

| Order | ||||

| Simpson_1-D | 0.791 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Shannon_H | 0.908 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Fisher_alpha | 0.820 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

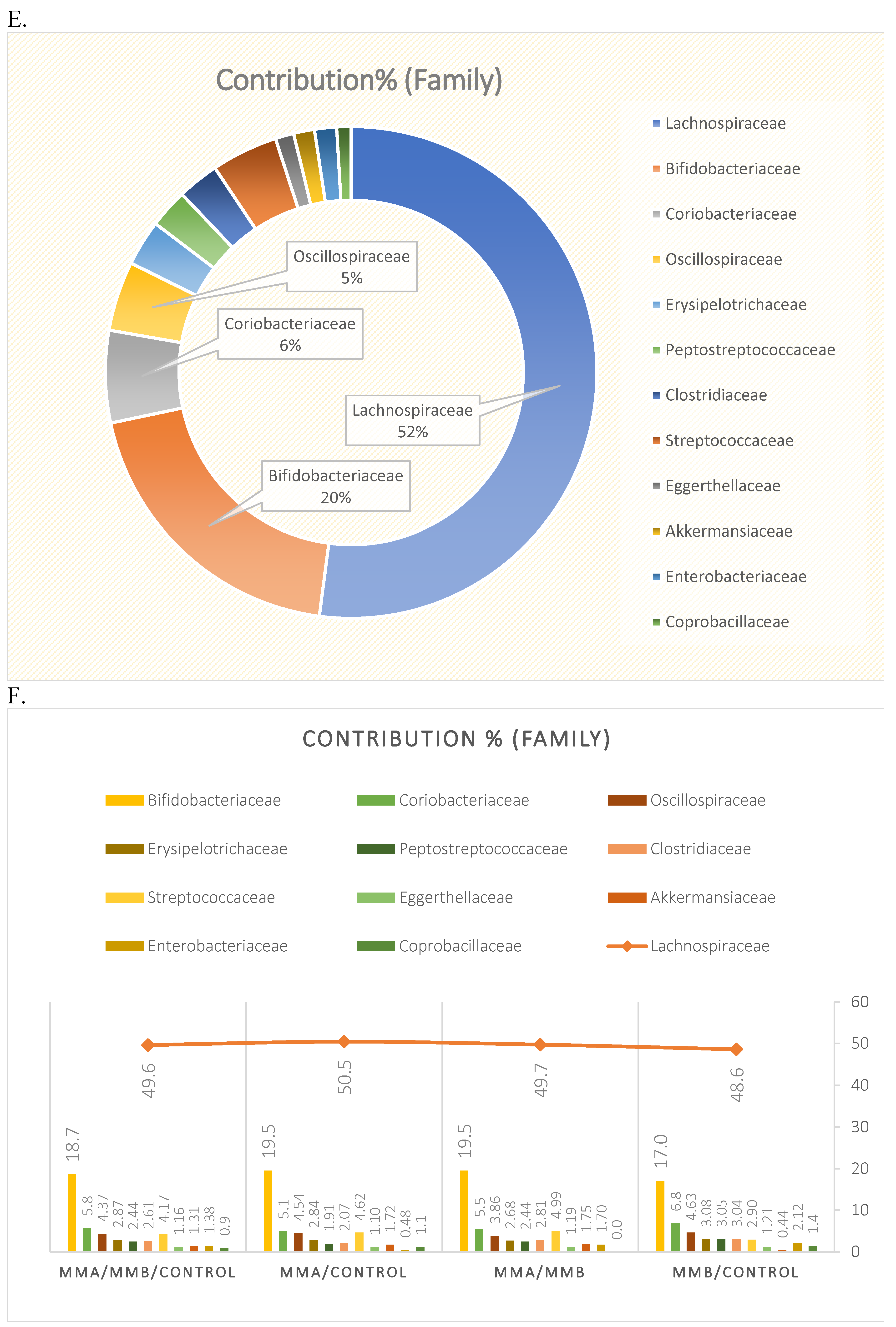

| Family | ||||

| Simpson_1-D | 0.564 | 1.000 | 0.806 | 1.000 |

| Shannon_H | 0.262 | 1.000 | 0.255 | 1.000 |

| Fisher_alpha | 0.343 | 1.000 | 0.472 | 1.000 |

| Class | ||||

| Simpson_1-D | 0.765 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Shannon_H | 0.851 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Fisher_alpha | 0.716 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Phyllum | ||||

| Simpson_1-D | 0.959 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Shannon_H | 0.859 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Fisher_alpha | 0.146 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.112 |

| Bray-Curtis distance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERMANOVA | F | p | MMA-MMB | MMA-CG | MMB-CG |

| Phyllum | 1.475 | 0.071* | 0.026* | 0.694 | 1.000 |

| Class | 1.778 | 0.026* | 0.020* | 0.111 | 1.000 |

| Family | 3.679 | 0.000* | 0.004* | 0.000* | 0.002* |

| Order | 2.787 | 0.000* | 0.009* | 0.001* | 0.134 |

| Genus | 5.453 | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.001* |

| Species | 3.307 | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.001* | 0.038* |

| Whittaker global beta diversity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Indeks | p | MMA-MMB | MMA-CG | MMB-CG |

| Phyllum | 2.055 | 3.11E-06* | 0.000* | 0.128 | 0.002* |

| Class | 1.956 | 1.50E-02* | 0.018* | 0.175 | 0.480 |

| Family | 0.505 | 3.90E-05* | 0.809 | 0.003* | 0.000* |

| Order | 1.663 | 4.31E-10* | 1.000 | 0.000* | 0.000* |

| Genus | 0.170 | 9.40E-13* | 1.000 | 0.000* | 0.000* |

| Species | 0.256 | 1.04E-10* | 1.000 | 0.000* | 0.000* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).