1. Introduction

Bone age evaluation constitutes a cornerstone of pediatric clinical practice, with broad applications spanning diagnostic decision-making, treatment planning, and medicolegal assessments [

1,

2]. In endocrinological and metabolic disorders—including growth hormone deficiency, thyroid disease, precocious puberty, and constitutional growth delay—bone age assessment represents a critical tool in pediatric clinical evaluation. Accurate determination of skeletal maturation underpins diagnostic accuracy, enables estimation of remaining growth potential, supports prediction of final adult height, and contributes to the appropriate timing and optimization of therapeutic interventions [

3,

4,

5]. In addition to its established role in endocrinology, bone age assessment constitutes a fundamental tool in forensic medicine, where it is routinely applied to estimate chronological age in individuals without reliable birth documentation, particularly in the context of asylum evaluations and judicial proceeding [

6].

Bone age estimation is traditionally performed using radiographic analysis of the left hand and wrist based on standardized atlases, most notably the Greulich-Pyle (GP) atlas and the Gilsanz-Ratib (GR) Digital Atlas [

1,

2]. These atlas-based approaches assess skeletal maturation by examining ossification centers, patterns of epiphyseal development, carpal bone maturation, and growth plate closure. The GP method, first introduced in 1959, is based on visual comparison with standardized reference radiographs, whereas the more recent GR atlas provides sex-specific digital reference images at six-month intervals [

1,

2].This digital framework, which stages maturity based on specific bone morphology rather than broad pattern matching, is particularly relevant when evaluating contemporary digital diagnostic tools. Alternative strategies include the Tanner–Whitehouse (TW) method, which relies on a numerical scoring system applied to individual bone [

7].Although these atlas-based techniques are widely regarded as the clinical gold standard, their application remains inherently dependent on radiologist experience and subjective interpretation, resulting in unavoidable inter- and intraobserver variability, with reported mean absolute differences ranging from 0.41 to 0.93 years even among experienced readers [

8,

9,

10].

Driven by rapid progress in artificial intelligence (AI), automated medical image analysis has become a prominent focus in contemporary radiology and clinical research [

11,

12,

13]. Early deep-learning approaches to automated bone age assessment primarily relied on convolutional neural networks ( CNNs) trained to estimate skeletal maturity directly from hand radiographs [

14,

15,

16].Early fully automated deep-learning systems for bone age assessment were demonstrated in studies such as Lee et al. [

14]. Landmark benchmarks, including the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) Pediatric Bone Age Machine Learning Challenge, as well as subsequent clinical evaluations, reportedmean absolute error (MAE) on the order of ~4–6 months under specific test settings [

15,

16]. In practice, these pipelines—largely based on CNNs—typically depend on large, carefully annotated training cohorts (often in the 10,000+ range) and task-specific model development and training workflows [

15,

16,

17,

18].

More recently, multimodal large language models (LLMs)—foundation models that can jointly process images and text—have emerged as a distinct AI paradigm with growing interest in medical application [

19,

20,

21]. By leveraging large-scale pre-training and instruction-style prompting, foundation models can generalize in zero-shot or few-shot settings; when combined with vision–language pre-training, they can integrate image content with natural-language context in selected applications [

22,

23].

Recently, the utility of multimodal LLMs has been increasingly explored across a diverse spectrum of radiological tasks, ranging from the interpretation of chest radiographs to the analysis of cross-sectional imaging findings [

24,

25,

26,

27]. However, despite these promising capabilities, the diagnostic performance of such models in nuanced and clinically critical domains—such as pediatric bone age assessment—remains insufficiently characterized. In particular, a systematic benchmarking of distinct multimodal foundation models using standardized protocols that mimic real-world clinical scenarios is essential to establish the robust evidence base required for their future clinical integration.

In our study, we evaluated four state-of-the-art multimodal systems—ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI), Claude 4 (Anthropic), Gemini 2.5 Pro (Google), and Grok-3 (xAI)—all of which support image inputs together with natural-language instructions [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Unlike task-specific CNN models, instruction-tuned multimodal LLMs commonly link a pre-trained vision encoder to a language model, enabling more general-purpose vision–language inference across multiple tasks [

32,

33]. Crucially, the performance of these models depends on their ability to interpret natural language instructions and integrate them with visual features, offering a fundamentally different paradigm from conventional regression-based CNNs.

The aim of this investigation is to quantify the diagnostic performance of these four multimodal LLMs in bone age assessment using the GR Atlas, benchmarked against an expert radiologist reference standard.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

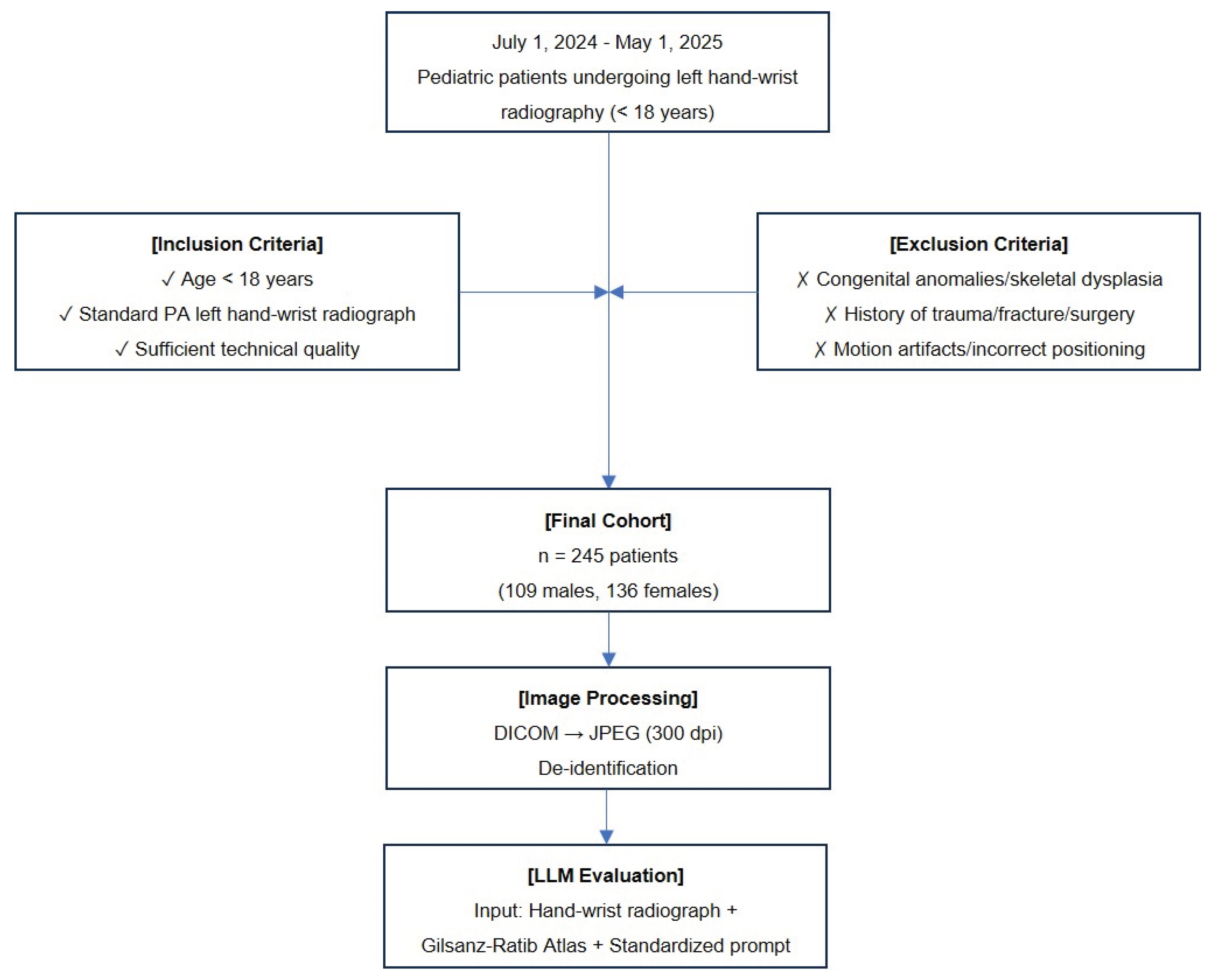

This retrospective, single-center study included pediatric patients (age < 18 years) who underwent left hand–wrist radiography for bone age assessment between 1 July 2024 and 1 May 2025. A final cohort of 245 patients (109 males, 136 females) was included in the study. All examinations were performed for established clinical indications, including the evaluation of growth disorders, endocrinological–metabolic conditions, or forensic age estimation.The flowchart illustrates the systematic workflow of the study (

Figure 1).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were defined as follows: (1) chronological age below 18 years; (2) availability of a standard posteroanterior (PA) left hand–wrist radiograph; and (3) radiographs of sufficient technical quality for diagnostic interpretation. The exclusion criteria included: (1) congenital hand–wrist anatomical anomalies or skeletal dysplasias; (2) history of significant hand–wrist trauma, fracture, or prior surgical intervention; and (3) radiographs with significant motion artifacts or incorrect positioning that would preclude reliable bone age assessment.

2.3. Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (Decision No.: 2025-45, Date: 18 September 2025). All procedures were conducted in full accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of de-identified data, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

2.4. Radiographic Acquisition and Pre-processing

All radiographic examinations were performed using a standardized digital radiography system (GXR82 SD; DRGEM Corp., Gwangmyeong, South Korea) with acquisition parameters standardized to 40–55 kVp and 2–3 mAs. To facilitate analysis by the multimodal LLMs, the original Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) images were exported from RadiAnt DICOM viewer software (version 2020.2.3, 64-bit, Medixant, Poznań, Poland) and then converted into high-resolution Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) format at 300 dots per inch (dpi). Prior to evaluation, all images were rigorously de-identified to remove patient identifiers and metadata, ensuring strict data privacy and blinding the models to the patients' chronological age.

2.5. Reference Standard Establishment

Bone age was assessed using the GR Digital Atlas [

2]. To validate the reliability of the reference standard, a quality-control subset of 30 radiographs was randomly selected for inter-observer assessment, with the sample size defined a priori in accordance with methodological guidance on intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)-based reliability study designs [

34,

35]. These radiographs were independently interpreted by two radiologists (with 8 and 9 years of experience in musculoskeletal radiography, respectively), who were blinded to each other’s measurements. Inter-observer agreement was quantified using the ICC and Pearson correlation, and further characterized by the mean absolute difference and Bland–Altman analysis. Given the excellent inter-observer agreement observed in this quality-control sample (ICC = 0.987), bone age assessment for the entire cohort was subsequently performed by the primary radiologist (with 9 years of experience). Consequently, the primary reader’s bone age measurements served as the ground truth reference standard for all subsequent LLM performance evaluations.

2.6. Large Language Models and Experimental Setup

This study benchmarked the diagnostic performance of four state-of-the-art multimodalLLMs, selected based on their advanced vision-language processing capabilities available as of September 2025. The specific models evaluated included: (1) ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA), (2) Google Gemini 2.5 Pro (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA), (3) Claude 4 Sonnet (Anthropic, San Francisco, CA, USA), and (4) Grok-3 (xAI, San Francisco, CA, USA). All models were accessed via their respective official web interfaces or Application Programming Interface (API), utilizing the most current stable versions available during the study period.

To ensure standardized and reproducible input across all models, a structured prompting strategy was employed. Each LLM was provided with the identical high-resolution JPEG image of the hand-wrist radiograph and the patient's biological sex. The prompt explicitly instructed the model to analyze the image according to the standardized criteria of the GR Digital Atlas and to provide a single numerical bone age estimate.To minimize variability, the model temperature parameter was set to 0 where API access permitted. The standardized prompt used for all queries was as follows:

"You are provided with a posteroanterior left hand and wrist radiograph of a [Male/Female] patient along with the Gilsanz–Ratib Digital Atlas as reference material. Your task: Estimate bone age by comparing the provided radiograph with the Gilsanz–Ratib Digital Atlas. Response format: 'Estimated Bone Age: [X.X years]'. Please provide a short and concise answer using only the format above, without explanation."

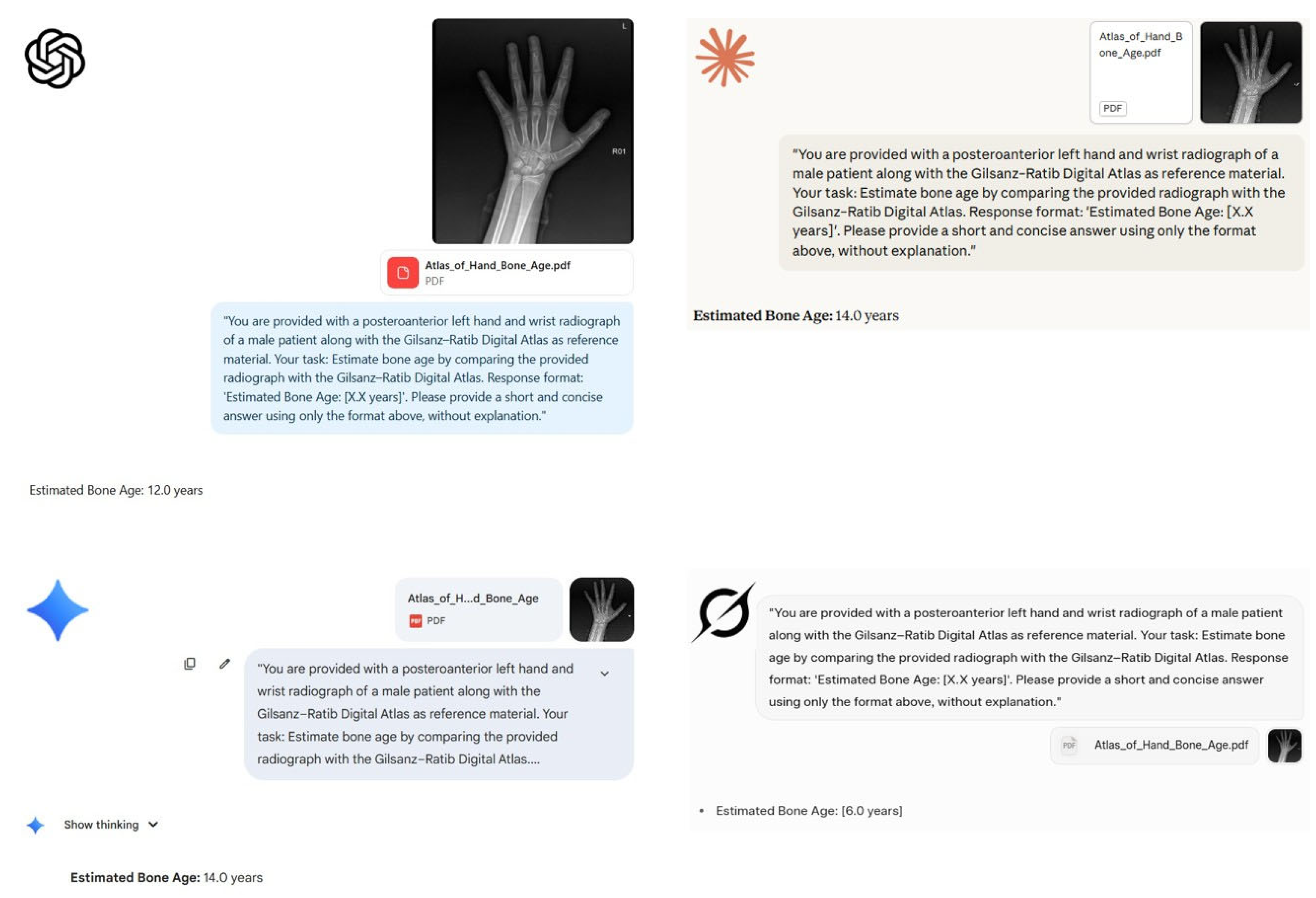

A representative example of patient evaluation by the models is illustrated in

Figure 2.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and range, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

To quantify the diagnostic accuracy of the LLMs, both the MAE and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) were calculated. MAE represented the average absolute difference between the model's predicted bone age and the reference standard (primary radiologist's assessment), while RMSE was computed to penalize larger prediction errors and assess model precision. The non-parametric Friedman test was employed to compare the paired error distributions across the four LLMs. Significant differences identified by the Friedman test were further analyzed using post-hoc pairwise comparisons.

Agreement between the LLM predictions and the reference standard was evaluated using the ICC (two-way mixed-effects model, absolute agreement) and the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) to assess linear relationships. Additionally, Bland–Altman analysis was conducted to visualize the agreement and quantify systematic bias. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

2.8. Use of AI Tools

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Google Gemini 2.5 Pro (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA) for text generation, editing, and translation between languages. The authors have reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Demographic Characteristics

A total of 245 pediatric patients were included in this retrospective study. The cohort consisted of 109 (44.5%) males and 136 (55.5%) females. The mean chronological age of the study population was 10.08 ± 3.21 years (range: 1.67–17.75 years). There was no statistically significant difference in chronological age between gender groups (p = 0.083).

The mean bone age determined by the reference radiologist was 10.1 ± 4.2 years. Detailed demographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Radiologist Inter-Observer Reliability

In the quality-control subset (n=30), the inter-observer reliability between the two radiologists (8 and 9 years of experience) was excellent. The ICC was 0.987 (95% CI: 0.972–0.994; p < 0.001), indicating near-perfect consistency. The mean absolute difference between the two readers was minimal (0.43 years). Furthermore, clinical agreement (defined as a difference of ≤1.0 year) was observed in 86.7% (26/30) of the cases, confirming the robustness of the reading method. Given this high level of agreement, the primary radiologist's measurements served as the reference standard for the entire cohort.Detailed interobserver reliability metrics are presented in

Table 2.

3.3. Comparative Diagnostic Performance of Multimodal LLMs

The diagnostic performance metrics of the four multimodal LLMs against the reference standard are detailed in

Table 3. ChatGPT-5 demonstrated statistically superior performance compared to all other models, achieving the lowest MAE of 1.46 years and the highest agreement with the reference standard (ICC = 0.849; 95% CI: 0.791–0.888; p< 0.001). Gemini 2.5 Pro ranked second with an MAE of 2.24 years and an ICC of 0.761 (95% CI: 0.687–0.817), showing moderate correlation compared to ChatGPT-5. This was followed by Grok-3, which exhibited significantly lower performance with an MAE of 3.14 years and an ICC of 0.379 (95% CI: 0.267–0.481), indicating poor reliability. Claude 4 Sonnet exhibited the poorest performance among all models, with the highest MAE (4.29 years) and the lowest ICC (0.216; 95% CI: 0.072–0.348), reflecting a lack of concordance with the expert radiologist. The Friedman test confirmed a statistically significant difference in error distributions across the models (χ²= 150.36, p< 0.001), with post-hoc analysis favoring ChatGPT-5.

3.4. Bias and Agreement Analysis (Bland–Altman)

Bland–Altman analysis, detailed in

Table 4, revealed distinct error profiles among the models. ChatGPT-5 exhibited the highest consistency with the lowest standard deviation of differences (SD = 1.85 years), showing a negligible negative bias of −0.59 years and the narrowest Limits of Agreement (LoA) range (7.25 years).

In contrast, Gemini 2.5 Pro displayed a moderate positive bias of +0.78 years, indicating a general tendency to overestimate bone age, with an intermediate LoA range (−4.51 to +6.07 years). Claude 4 Sonnet demonstrated the most substantial systematic error, consistently overestimating skeletal maturity by an average of +2.40 years with a wide error spread (SD = 4.74 years).

Notably, although Grok-3 presented a relatively low mean bias (+0.41 years), it exhibited significant instability in individual predictions. This was evidenced by a high standard deviation (SD = 4.01 years) and a remarkably wide LoA range (−7.44 to +8.26 years), suggesting that while its average error is low, its individual predictions are highly variable and unpredictable.

3.5. Clinical Utility and Stratification

Based on a clinical acceptability threshold of MAE < 1.5 years, the models were stratified into levels of utility as summarized in

Table 5. ChatGPT-5 was the sole model to qualify for the "Clinically Useful" tier, demonstrating sufficient reliability to serve as a supportive tool in radiological workflows. Gemini 2.5 Pro was classified as "Marginally Acceptable," indicating potential value subject to substantial expert revision. Conversely, both Grok-3 and Claude 4 Sonnet were deemed "Not Recommended" for clinical integration due to error margins exceeding acceptable limits and significant inconsistency in predictions.

4. Discussion

This study represents one of the pioneering systematic benchmarks evaluating the diagnostic utility of four multimodal LLMs—ChatGPT-5, Gemini 2.5 Pro, Grok-3, and Claude 4 Sonnet—against an expert radiologist standard in pediatric bone age assessment. Our findings reveal a profound performance disparity among current foundation models. While the leading model (ChatGPT-5) demonstrated a promising alignment with clinical standards (MAE: 1.46 years), the performance of other models, particularly Claude 4 Sonnet and Grok-3, fell significantly short of diagnostic acceptability, exhibiting error margins (MAE > 3.0 years) that would be deemed unsafe for clinical practice.

4.1. Comparative Performance and the "AI Gap" in Radiology

Bone age assessment is a nuanced task requiring the synthesis of complex morphological features, traditionally associated with interobserver variability of 0.4–0.9 years even among human experts [

8,

9,

10]. In our study, the rigorous quality-control subset demonstrated near-perfect agreement between radiologists (ICC = 0.987; MAE = 0.43 years), establishing a robust ground truth.

In stark contrast, a significant performance gap remains between this human "gold standard" and generalist AI. Even the top-performing model, ChatGPT-5, yielded an MAE of 1.46 years. This error margin is substantially wider than that of task-specific CNNs, which consistently achieve MAEs in the range of 4 to 6 months (0.3–0.5 years) in landmark benchmarks such as the RSNA Pediatric Bone Age Challenge [

15,

16]. This discrepancy highlights a fundamental distinction in AI architectures: while specialized CNNs are trained via supervised learning on massive, annotated datasets for pixel-level regression, multimodal LLMs operate as generalist "reasoning engines." Our results regarding the poor performance of Grok-3 (ICC: 0.379) and Claude 4 Sonnet (ICC: 0.216) suggest that, despite advanced vision encoders, many general-purpose LLMs currently lack the fine-grained feature discrimination required to match the precision of dedicated narrow AI models in specialized radiological tasks [

19,

20].

4.2. Methodology: The Impact of Atlas-Assisted Prompting

A distinguishing methodological feature of this study was the "atlas-assisted" evaluation protocol. Unlike standard zero-shot benchmarks where models rely solely on pre-trained weights, we simulated a comparative radiological workflow by providing the LLMs with both the patient radiograph and the corresponding GR digital reference plates.

Recently, Büyüktoka and Salbaş evaluated the zero-shot performance of multimodal LLMs, including Gemini 2.5 Pro and ChatGPT-4.5, on the RSNA pediatric dataset [

36]. In their analysis, even the top-performing model (Gemini 2.5 Pro) exhibited a high mean absolute error of approximately 2.37 years (28.48 months), leading them to conclude that current models are unsuitable for clinical use. In contrast, our study achieved a significantly lower MAE of 1.46 years with ChatGPT-5. This substantial performance gain in our cohort may be attributed to two key factors: the superior reasoning capabilities of the newer ChatGPT-5 architecture and, crucially, our implementation of an "atlas-assisted" prompting protocol, which provides the model with a reference standard rather than relying solely on internal weights.

The superior performance of ChatGPT-5 and, to a lesser extent, Gemini 2.5 Pro, suggests that these models possess a more advanced capability to integrate multimodal inputs [

27,

32]—performing visual cross-referencing between the "patient" and "atlas" images. However, this scaffolding proved insufficient for other models. Claude 4 Sonnet exhibited a massive systematic failure with an MAE of 4.29 years and a substantial positive bias (+2.40 years). Such systematic overestimation is clinically dangerous, as it could lead to the misdiagnosis of pathologies like precocious puberty or result in inappropriate aggressive treatments [

3,

4]. Similarly, while Grok-3 showed a low mean bias (+0.41 years), its high standard deviation and wide LoA (15.70 years) indicate a stochastic, unpredictable output pattern, rendering it unreliable despite the atlas support. This underscores that access to reference material cannot compensate for a model's intrinsic limitations in radiological pattern recognition.

4.3. Age-Dependent Variability and Clinical Implications

Consistent with previous literature on deep learning in auxology, our Bland–Altman analysis revealed performance degradation during the peri-pubertal period (approx. 10–15 years) across all models [

5,

14,

16]. This developmental phase involves subtle, rapid morphological changes in the carpal bones and epiphyses that are challenging to quantify without explicit measurements. The inability of current LLMs to consistently interpret these transitional stages mirrors the "fine-grained" vs. "coarse-grained" visual recognition challenge seen in computer vision research [

14,

17].

From a clinical utility perspective, a clear stratification emerged. ChatGPT-5 is the only model approaching a "Tier 1" utility level, potentially suitable as a "second reader" or educational adjunct [

13], provided the user is aware of its slight tendency to underestimate age (bias: -0.59 years). Gemini 2.5 Pro (Tier 2) requires mandatory expert revision. Conversely, Grok-3 and Claude 4 Sonnet failed to meet even the minimum requirements for rough screening [

6].

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

The primary strength of this investigation lies in its comprehensive comparative design. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to benchmark the diagnostic performance of these four distinct multimodal foundation models (ChatGPT-5, Gemini 2.5 Pro, Claude 4 Sonnet, and Grok-3) simultaneously for pediatric bone age assessment. By including newer and less-evaluated models such as Grok-3 and Claude 4 Sonnet, our study addresses a critical gap in the current radiological AI literature, which has predominantly focused on OpenAI and Google ecosystems. Additionally, the adoption of an "atlas-assisted" prompting protocol mimics real-world radiological practice, providing a more ecologically valid assessment of LLM capabilities compared to standard zero-shot benchmarks.

However, this study is subject to several limitations. First, the retrospective, single-center design may limit the generalizability of findings to diverse ethnic populations, as skeletal maturation norms can vary globally [

9]. Second, we utilized commercial, closed-source models; thus, the exact composition of their training data—and whether it included open-access bone age atlases—remains opaque, raising the possibility of data contamination. Third, due to the retrospective design and anonymization protocols, clinical diagnoses were not correlated with bone age findings. Therefore, this study focused strictly on the agreement between AI models and the radiologist's assessment, rather than the accuracy of age prediction relative to chronological age. Future research should explore "Chain-of-Thought" prompting, where LLMs are instructed to explicitly identify and describe specific ossification centers before generating an age estimate, which could potentially improve interpretability and accuracy [

22,

37]. Fourth, although our quality-control subset demonstrated excellent inter-observer agreement (ICC = 0.987), establishing the reference standard based primarily on a single expert radiologist's assessment for the full cohort represents a limitation inherent to the retrospective design. While common in large-scale studies, potential individual reader bias cannot be entirely excluded.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that while multimodal LLMs such as ChatGPT-5 show emerging promise in pediatric bone age assessment, they have not yet achieved the diagnostic precision of experienced radiologists or specialized CNNs. The significant performance disparities—ranging from the potentially useful (ChatGPT-5) to the clinically unreliable (Claude 4 Sonnet)—highlight that "multimodal" capability is not uniform across all foundation models. While the "atlas-assisted" approach validates the potential of LLMs to perform comparative reasoning, significant architectural improvements in fine-grained visual processing are necessary before these tools can be safely integrated into autonomous diagnostic workflows. Nevertheless, given the rapid evolution of multimodal LLM technology and ongoing model optimizations, these models hold significant potential to evolve into reliable adjunctive tools for bone age assessment in the near future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O. and M.K.; methodology, E.O. and M.K.; validation, E.O. and M.K.; formal analysis, E.O.; investigation, E.O. and M.K.; resources, E.O. and M.K.; data curation, E.O.; writing—original draft preparation, E.O.; writing—review and editing, M.K.; visualization, E.O. and M.K.; supervision, M.K..; project administration, E.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Kastamonu University, Turkey (Decision No.: 2025-45, Date: 18 September 2025)

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Google Gemini 2.5 Pro (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA) for text generation, editing, and translation between languages. The authors have reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Greulich, W.W.; Pyle, S.I. Radiographic atlas of skeletal development of the hand and wrist. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 1959, 238, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsanz, V.; Ratib, O. Hand bone age: a digital atlas of skeletal maturity; Springer, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, J.M. Assessment of skeletal maturity and prediction of adult height. TW 2 Method 1983, 50–106. [Google Scholar]

- Satoh, M. Bone age: assessment methods and clinical applications. Clinical Pediatric Endocrinology 2015, 24, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malina, R.M.; Rogol, A.D.; Cumming, S.P.; e Silva, M.J.C.; Figueiredo, A.J. Biological maturation of youth athletes: assessment and implications. British journal of sports medicine 2015, 49, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeling, A.; Grundmann, C.; Fuhrmann, A.; Kaatsch, H.-J.; Knell, B.; Ramsthaler, F.; Reisinger, W.; Riepert, T.; Ritz-Timme, S.; Rösing, F.W. Criteria for age estimation in living individuals. International journal of legal medicine 2008, 122, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.M.; Healy, M.J.R.; Cameron, N.; Goldstein, H. Assessment of Skeletal Maturity and Prediction of Adult Height (TW3 Method); W.B. Saunders, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Büken, B.; Safak, A.A.; Yazici, B.; Büken, E.; Mayda, A.S. Is the assessment of bone age by the Greulich-Pyle method reliable at forensic age estimation for Turkish children? Forensic Sci Int 2007, 173, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontell, F.K.; Ivanovic, M.; Ablin, D.S.; Barlow, T.W. Bone age in children of diverse ethnicity. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996, 167, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, R.K.; Edwards, P.D.; Kemp, P.M.; Fry, S.; Hughes, I.A. Bone age assessment: a large scale comparison of the Greulich and Pyle, and Tanner and Whitehouse (TW2) methods. Arch Dis Child 1999, 81, 172–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosny, A.; Parmar, C.; Quackenbush, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Aerts, H. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesapane, F.; Codari, M.; Sardanelli, F. Artificial intelligence in medical imaging: threat or opportunity? Radiologists again at the forefront of innovation in medicine. Eur Radiol Exp 2018, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Tajmir, S.; Lee, J.; Zissen, M.; Yeshiwas, B.A.; Alkasab, T.K.; Choy, G.; Do, S. Fully Automated Deep Learning System for Bone Age Assessment. J Digit Imaging 2017, 30, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabi, S.S.; Prevedello, L.M.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Mamonov, A.B.; Bilbily, A.; Cicero, M.; Pan, I.; Pereira, L.A.; Sousa, R.T.; Abdala, N.; et al. The RSNA Pediatric Bone Age Machine Learning Challenge. Radiology 2019, 290, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, D.B.; Chen, M.C.; Lungren, M.P.; Halabi, S.S.; Stence, N.V.; Langlotz, C.P. Performance of a Deep-Learning Neural Network Model in Assessing Skeletal Maturity on Pediatric Hand Radiographs. Radiology 2018, 287, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, C.; Palazzo, S.; Giordano, D.; Aldinucci, M.; Leonardi, R. Deep learning for automated skeletal bone age assessment in X-ray images. Med Image Anal 2017, 36, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglovikov, V.I.; Rakhlin, A.; Kalinin, A.A.; Shvets, A.A. Paediatric Bone Age Assessment Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support, Cham, 2018; pp. 300–308. [Google Scholar]

- Moor, M.; Banerjee, O.; Abad, Z.S.H.; Krumholz, H.M.; Leskovec, J.; Topol, E.J.; Rajpurkar, P. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature 2023, 616, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Ting, D.S.J.; Elangovan, K.; Gutierrez, L.; Tan, T.F.; Ting, D.S.W. Large language models in medicine. Nature Medicine 2023, 29, 1930–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Scales, N.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning, 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Ong, H.; Kennedy, P.; Wu, C.C.; Kazam, J.; Hentel, K.; Flanders, A.; Shih, G.; Peng, Y. Evaluating GPT-4V (GPT-4 with Vision) on Detection of Radiologic Findings on Chest Radiographs. Radiology 2024, 311, e233270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Youn, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, M.; Yoon, S.H. CXR-LLaVA: a multimodal large language model for interpreting chest X-ray images. Eur Radiol 2025, 35, 4374–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, D.; Sorin, V.; Barash, Y.; Konen, E.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Klang, E. Assessing GPT-4 multimodal performance in radiological image analysis. Eur Radiol 2025, 35, 1959–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Kyung, S.; Seo, J.; Song, J.M.; Kwon, J.; Kim, J.; Jo, W.; Park, H.; Sung, J.; et al. Multimodal Large Language Models in Medical Imaging: Current State and Future Directions. Korean J Radiol 2025, 26, 900–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- xAI. Grok 3 Beta — The Age of Reasoning Agents. Available online: https://x.ai/news/grok-3/ (accessed on 25 Sep 2025).

- Google. Gemini 2.5 Pro. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/docs/models/gemini/2-5-pro (accessed on 27 Sep 2025).

- Anthropic. Introducing Claude 4. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-4 (accessed on 29 Sep 2025).

- OpenAI. Introducing GPT-5. Available online: https://openai.com/index/introducing-gpt-5/ (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 34892–34916. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Tiong, A.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Fung, P.N.; Hoi, S. Instructblip: Towards general-purpose vision-language models with instruction tuning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 49250–49267. [Google Scholar]

- Bonett, D.G. Sample size requirements for estimating intraclass correlations with desired precision. Stat Med 2002, 21, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, S.D.; Eliasziw, M.; Donner, A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat Med 1998, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüktoka, R.E.; Salbas, A. Multimodal Large Language Models for Pediatric Bone-Age Assessment: A Comparative Accuracy Analysis. Acad Radiol 2025, 32, 6905–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

ChatGPT-5: 12.0 years,

ChatGPT-5: 12.0 years,  Claude 4 Sonnet: 14.0 years,

Claude 4 Sonnet: 14.0 years,  Google Gemini 2.5 Pro: 14.0 years, and

Google Gemini 2.5 Pro: 14.0 years, and  Grok-3: 6.0 years. The screenshots show each model's response and reveal the variability in estimated bone age across platforms.

Grok-3: 6.0 years. The screenshots show each model's response and reveal the variability in estimated bone age across platforms.

ChatGPT-5: 12.0 years,

ChatGPT-5: 12.0 years,  Claude 4 Sonnet: 14.0 years,

Claude 4 Sonnet: 14.0 years,  Google Gemini 2.5 Pro: 14.0 years, and

Google Gemini 2.5 Pro: 14.0 years, and  Grok-3: 6.0 years. The screenshots show each model's response and reveal the variability in estimated bone age across platforms.

Grok-3: 6.0 years. The screenshots show each model's response and reveal the variability in estimated bone age across platforms.