Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Test Methods

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Main Results

3.2.1. Precision

- Intra-rater Agreement

- Inter-rater agreement

3.2.2. Accuracy

4. Discussion

4.1. Precision of TW3

4.1.1. Intra-Rater Agreement

4.1.2. Inter-Rater Agreement

4.2. Accuracy of TW3

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tanner, J.M. Growth at Adolescence; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1962; pp. 1–350.

- Greulich, W.W.; Pyle, S.I. Radiographic Atlas of Skeletal Development of the Hand and Wrist, 2nd ed.; Stanford University Press: California, CA, USA, 1959; pp. 1–272.

- Ebrí Torné, B. Maduración ósea: Metodología numérica sobre tarso y carpo; [s.n.]: 1988; pp. 1–320.

- Martín Pérez, S.E.; Martín Pérez, I.M.; Vega González, J.M.; Molina Suárez, R.; León Hernández, C.; Rodríguez Hernández, F.; Herrera Pérez, M. Precision and Accuracy of Radiological Bone Age Assessment in Children among Different Ethnic Groups: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3124. [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.M.; Whitehouse, R.; Healy, M. A New System for Estimating Skeletal Maturity from the Hand and Wrist, with Standards Derived from a Study of 2,600 Healthy British Children. Part II: The Scoring System; Centre International de L’Enfance: Paris, France, 1962; pp. 1–100.

- Tanner, J.M.; Whitehouse, R.H.; Marshall, W.A., et al. Assessment of Skeletal Maturity and Prediction of Adult Height (TW2 Method); Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 1–142.

- Tanner, J.M.; Realy, J.; Goldstein, H. Assessment of Skeletal Maturity and Prediction of Adult Height (TW3 Method); Harcourt Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 1–200.

- Fregel, R.; Ordóñez, A.C.; Serrano, J.G. The Demography of the Canary Islands from a Genetic Perspective. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, R64–R71.

- Tejera Gaspar, A. Tenerife y los guanches; Centro de la Cultura Popular Canaria: Tenerife, Spain, 2002; p. 17.

- Afonso, L. Esquema de geografía física de las islas canarias; Ediciones Idea: Tenerife, Spain, 2004; p. 210.

- Martín Ruiz, J.F. La población de Canarias: Análisis sociodemográfico y territorial (El debate actual); Anroart Ediciones: Las Palmas, Spain, 2005; p. 116.

- Burriel de Orueta, E.L. Canarias: Población y agricultura en una sociedad dependientes; Oikos-Tau: Barcelona, Spain, 1982; pp. 46–47.

- Hernandez Hernández, P. Natura y Cultura de las Islas Canarias, 8th ed.; 2003; pp. 56, 63.

- Toledo Trujillo, F.M. Maduración Ósea en una Muestra de Población Urbana de las Islas Canarias. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de La Laguna, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain, 1978.

- Toledo, F.; Cruz, M.; Pastor, S.; Paz, G.; Fernández, J.; Machado, M. Estudios radio-antropométrico de una muestra preadulta de la población canaria. In Actualizaciones en Medicina del Hospital Universitario de Canarias; Cabildo de Tenerife: Tenerife, Spain, 1992; pp. 25–35.

- Martín Pérez, I.M.; Martín Pérez, S.E.; Vega González, J.M.; Molina Suárez, R.; García Hernández, A.M.; Rodríguez Hernández, F.; Herrera Pérez, M. The Validation of the Greulich and Pyle Atlas for Radiological Bone Age Assessments in a Pediatric Population from the Canary Islands. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1847. [CrossRef]

- Martín Pérez, S.E.; Martín Pérez, I.M.; Vega González, J.M.; Molina Suárez, R.; León Hernández, C.; Rodríguez Hernández, F.; Herrera Pérez, M. Análisis comparativo de dos métodos radiográficos para determinar la edad ósea en la población pediátrica canaria. In Proceedings of the III Congreso Internacional de Jóvenes por la Investigación, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain, 14–16 November 2019; Universidad de La Laguna: Tenerife, Spain, pp. 15–20.

- Cohen, J.F.; Korevaar, D.A.; Altman, D.G.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Hooft, L.; Irwig, L.; Levine, D.; Reitsma, J.B.; de Vet, H.C.; Bossuyt, P.M. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012799. [CrossRef]

- Fraga Bermúdez, J.M.; Fernández Lorenzo, J.R. La Pediatría, el Niño y el Pediatra: Una Aproximación General. In Tratado de Pediatría, 1st ed.; Moro Serrano, M., Málaga Guerrero, S., Madero López, L., Eds.; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1–18.

- Pinchi, V.; De Luca, F.; Ricciardi, F.; Focardi, M.; Piredda, V.; Mazzeo, E.; Norelli, G.-A. Skeletal age estimation for forensic purposes: A comparison of GP, TW2, and TW3 methods on an Italian sample. Forensic Sci. Int. 2014, 238, 83–90.

- López, P.; Morón, A.; Urdaneta, O. Maduración ósea de niños escolares (7–14 años) de las etnias Wayúu y Criolla del Municipio Maracaibo, Estado Zulia. Estudio Comparativo. Cienc. Odontológica 2020, 5, 99–111. Available online:https://produccioncientificaluz.org/index.php/cienciao/article/view/33940 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Kowo-Nyakoko, F.; Gregson, C.L.; Madanhire, T.; Stranix-Chibanda, L.; Rukuni, R.; Offiah, A.C.; Micklesfield, L.K.; Cooper, C.; Ferrand, R.A.; Rehman, A.M.; et al. Evaluation of two methods of bone age assessment in peripubertal children in Zimbabwe. Bone 2023, 170, 116725.

- Kim, J.R.; Lee, Y.S.; Yu, J. Assessment of bone age in prepubertal healthy Korean children: Comparison among the Korean Standard Bone Age Chart, Greulich-Pyle Method, and Tanner-Whitehouse Method. Korean J. Radiol. 2015, 16, 201–205.

- Shin, N.Y.; Lee, B.D.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, H.R.; Oh, D.H.; Lee, B.I.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, M.S.; Heo, M.S. Evaluation of the Clinical Efficacy of a TW3-Based Fully Automated Bone Age Assessment System Using Deep Neural Networks. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2020, 50, 237–243. [CrossRef]

- Benjavongkulchai, S.; Pittayapat, P. Age estimation methods using hand and wrist radiographs in a group of contemporary Thais. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 287, 218.e1–218.e8.

- Geng, J.; Zhang, W.; Ge, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, P.; Liu, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhou, F.; Ma, K.; Blake, G.M.; Xu, G.; Yan, D.; Cheng, X. Inter-Rater Variability and Repeatability in the Assessment of the Tanner-Whitehouse Classification of Hand Radiographs for the Estimation of Bone Age. Skeletal Radiol. 2024, 53, 2635–2642. [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, K.; Offiah, A.C. Applicability of Two Commonly Used Bone Age Assessment Methods to Twenty-First Century UK Children. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 30, 504–513.

- Yuh, Y.S.; Chou, T.Y.; Tung, T.H. Bone Age Assessment: Large-Scale Comparison of Greulich-Pyle Method and Tanner-Whitehouse 3 Method for Taiwanese Children. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2023, 86, 246–253. [CrossRef]

- Toledo, F.; Rodríguez, I. Atlas radiológico de referencia de la edad ósea en la población canaria; Fundación Canaria Salud y Sanidad, Cabildo de Tenerife: Tenerife, Spain, 2009; p. 22.

- Ferrante, L.; Cameriere, R. Statistical methods to assess the reliability of measurements in the procedures for forensic age estimation. Int. J. Legal Med. 2009, 123, 277–283. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.L.; Warner, J.T. TW2 and TW3 Bone Ages: Time to Change? Arch. Dis. Child. 2007, 92, 371–372. [CrossRef]

- Ebrí-Torné, B. Comparative Study Between Bone Ages: Carpal, Metacarpophalangic, Carpometacarpophalangic Ebrí, Greulich and Pyle, and Tanner Whitehouse 2. Med. Res. Arch. 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C. Sexual Dimorphism of Body Composition. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 21(3), 415–430. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.F. Race, Genetics and Growth. J. Biosoc. Sci. 1969, 1(S1), 43–67.

- Díaz Gómez, N.M. Crecimiento y Desarrollo Físico del Niño; Tenerife, 1992; p. 18.

- Lejarraga, H. Growth in Infancy and Childhood: A Pediatric Approach. In Human Growth and Development; 2nd ed.; 2002.

- Thomis, M.A.; Towne, B. Genetic Determinants of Prepubertal and Pubertal Growth and Development. Food Nutr. Bull. 2006, 27(4 Suppl Growth Standard), S257–S278. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.L.; Sawyer, A.J.; Bachrach, L.K. Rationale for Bone Health Assessment in Childhood and Adolescence. In Bone Health Assessment in Pediatrics; Fung, E., Bachrach, L., Sawyer, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–21.

- López, J.M. Bone Development and Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6767. [CrossRef]

- Perrone, S.; Caporilli, C.; Grassi, F.; Ferrocino, M.; Biagi, E.; Dell’Orto, V.; Beretta, V.; Petrolini, C.; Gambini, L.; Street, M.E.; et al. Prenatal and Neonatal Bone Health: Updated Review on Early Identification of Newborns at High Risk for Osteopenia. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3515. [CrossRef]

- Boyanov, M.A. Bone Development in Children and Adolescents. In Puberty; Kumanov, P., Agarwal, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 105–123. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.; Llewellyn, C.H.; van Jaarsveld, C.H.; Cole, T.J.; Wardle, J. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Infant Growth: Prospective Analysis of the Gemini Twin Birth Cohort. PLoS One 2011, 6(5), e19918. [CrossRef]

- Iuliano-Burns, S.; Hopper, J.; Seeman, E. The Age of Puberty Determines Sexual Dimorphism in Bone Structure: A Male/Female Co-Twin Control Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94(5), 1638–1643. [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, L.I.; Bruzzaniti, A.; Pianeta, R. Sexual Dimorphism in the Musculoskeletal System: Sex Hormones and Beyond. J. Endocr. Soc. 2024, 8(10), bvae153. [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Reed, M.; Patel, S. Gender-Specific Pattern Differences of the Ossification Centers in the Pediatric Elbow. Pediatr. Radiol. 2009, 39, 226–231. [CrossRef]

- Bakos, B.; Takacs, I.; Stern, P.H.; et al. Skeletal Effects of Thyroid Hormones. Clin. Rev. Bone Miner. Metab. 2018, 16, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, J.H.D.; Williams, G.R. Role of Thyroid Hormones in Skeletal Development and Bone Maintenance. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37(2), 135–187. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Pang, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, B.; Gao, J. Endocrine Regulation on Bone by Thyroid. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 873820. [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.M.; Brent, G.A. The Influence of Thyroid Hormone on Growth Hormone Secretion and Action. In Growth Hormone Deficiency; Cohen, L., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 221–237. [CrossRef]

- Petrie, K.A.; Burbank, K.; Sizer, P.S.; James, C.R.; Zumwalt, M. Considerations of Sex Differences in Musculoskeletal Anatomy Between Males and Females. In The Active Female; Robert-McComb, J.J., Zumwalt, M., Fernandez-del-Valle, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 45–61. [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Hasegawa, Y. Factors Affecting Prepubertal and Pubertal Bone Age Progression. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 967711. [CrossRef]

- Nieves, J.W. Sex-Differences in Skeletal Growth and Aging. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2017, 15, 70–75. [CrossRef]

- Papalia, D.E.; Martorell, G. Desarrollo Humano; 13th ed.; McGraw Hill: Ciudad de México, 2017.

- Gavela-Pérez, T.; Garcés, C.; Navarro-Sánchez, P.; López Villanueva, L.; Soriano-Guillén, L. Earlier Menarcheal Age in Spanish Girls Is Related with an Increase in Body Mass Index Between Pre-Pubertal School Age and Adolescence. Pediatr. Obes. 2015, 10, 410–415. [CrossRef]

- De Bont, J.; Díaz, Y.; Casas, M.; García-Gil, M.; Vrijheid, M.; Duarte-Salles, T. Time Trends and Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents in Spain. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3. [CrossRef]

- Rogol, A.D. Leptin and Puberty. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83(4), 1089–1090. [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Verduci, E.; Magenes, V.C.; Pascuzzi, M.C.; Rossi, V.; Sangiorgio, A.; Bosetti, A.; Zuccotti, G.; Mameli, C. The Role of Pediatric Nutrition as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Precocious Puberty. Life 2021, 11, 1353. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yan, W.; Bigambo, F.M.; et al. Association Between Dietary Behavior and Puberty in Girls. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 349. [CrossRef]

- Noirrit-Esclassan, E.; Valera, M.-C.; Tremollieres, F.; Arnal, J.-F.; Lenfant, F.; Fontaine, C.; Vinel, A. Critical Role of Estrogens on Bone Homeostasis in Both Male and Female: From Physiology to Medical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1568. [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S.; Monroe, D.G. Regulation of Bone Metabolism by Sex Steroids. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8(1), a031211. [CrossRef]

| Stage | Gender | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preschool | Female | 24 | 39.33 | 15.18 | 20.00 | 67.00 | 0.235 | |

| Male | 45 | 46.49 | 13.33 | 18.00 | 69.00 | 0.105 | ||

| Age (mos.) | Scholar | Female | 40 | 92.00 | 26.08 | 85.00 | 118.00 | 0.310 |

| Male | 62 | 100.16 | 20.33 | 75.00 | 109.00 | 0.089 | ||

| Teenager | Female | 16 | 144.17 | 23.81 | 102.00 | 168.00 | 0.150 | |

| Male | 27 | 151.53 | 20.17 | 107.00 | 192.00 | 0.080 | ||

| Preschool | Female | 24 | 14.52 | 2.05 | 9.80 | 18.60 | 0.215 | |

| Male | 45 | 13.09 | 2.17 | 7.40 | 18.00 | 0.175 | ||

| Weight (kg) | Scholar | Female | 40 | 29.58 | 7.14 | 17.60 | 40.00 | 0.200 |

| Male | 62 | 23.67 | 4.85 | 14.20 | 44.00 | 0.115 | ||

| Teenager | Female | 16 | 33.84 | 4.62 | 22.00 | 39.50 | 0.250 | |

| Male | 27 | 34.21 | 3.19 | 23.80 | 45.70 | 0.140 | ||

| Preschool | Female | 24 | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.77 | 1.05 | 0.289 | |

| Male | 45 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.175 | ||

| Height (m) | Scholar | Female | 40 | 1.14 | 0.07 | 0.99 | 1.30 | 0.200 |

| Male | 62 | 1.16 | 0.05 | 0.94 | 1.40 | 0.115 | ||

| Teenager | Female | 16 | 1.33 | 0.04 | 1.21 | 1.37 | 0.250 | |

| Male | 27 | 1.33 | 0.03 | 1.16 | 1.45 | 0.140 | ||

| Preschool | Female | 24 | 17.53 | 2.47 | 8.32 | 19.49 | 0.180 | |

| Male | 45 | 14.81 | 2.45 | 18.81 | 18.87 | 0.120 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Scholar | Female | 40 | 22.76 | 5.49 | 13.45 | 20.29 | 0.175 |

| Male | 62 | 17.59 | 3.60 | 12.57 | 20.92 | 0.150 | ||

| Teenager | Female | 16 | 19.13 | 2.66 | 15.02 | 21.73 | 0.240 | |

| Male | 27 | 19.33 | 1.80 | 14.61 | 20.99 | 0.130 |

| Group | Time of Measurement | Gender | Mean | ICC | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rater 1 | T1 | Female | 76.82 | |||

| Male | 77.94 | |||||

| T2 | Female | 74.89 | 0.996 | 0.991 | 0.998 | |

| Male | 75.67 | 0.994 | 0.989 | 0.997 | ||

| Rater 2 | T1 | Female | 73.50 | |||

| Male | 81.32 | |||||

| T2 | Female | 71.12 | 0.988 | 0.976 | 0.994 | |

| Male | 79.58 | 0.993 | 0.980 | 0.997 | ||

| Rater 3 | T1 | Female | 77.45 | |||

| Male | 79.02 | |||||

| T2 | Female | 79.34 | 0.845 | 0.968 | 0.964 | |

| Male | 80.21 | 0.935 | 0.986 | 0.989 |

| Groups | Gender | Mean | ICC | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rater 1–Rater 2 | Female | 76.82 | |||

| 73.50 | 0.976 | 0.950 | 0.987 | ||

| Male | 77.94 | ||||

| 81.32 | 0.968 | 0.940 | 0.982 | ||

| Rater 1–Rater 3 | Female | 76.82 | |||

| 77.45 | 0.812 | 0.702 | 0.896 | ||

| Male | 77.94 | ||||

| 79.02 | 0.857 | 0.770 | 0.921 | ||

| Rater 2–Rater 3 | Female | 73.50 | |||

| 77.45 | 0.880 | 0.820 | 0.922 | ||

| Male | 81.732 | ||||

| 79.02 | 0.912 | 0.860 | 0.946 |

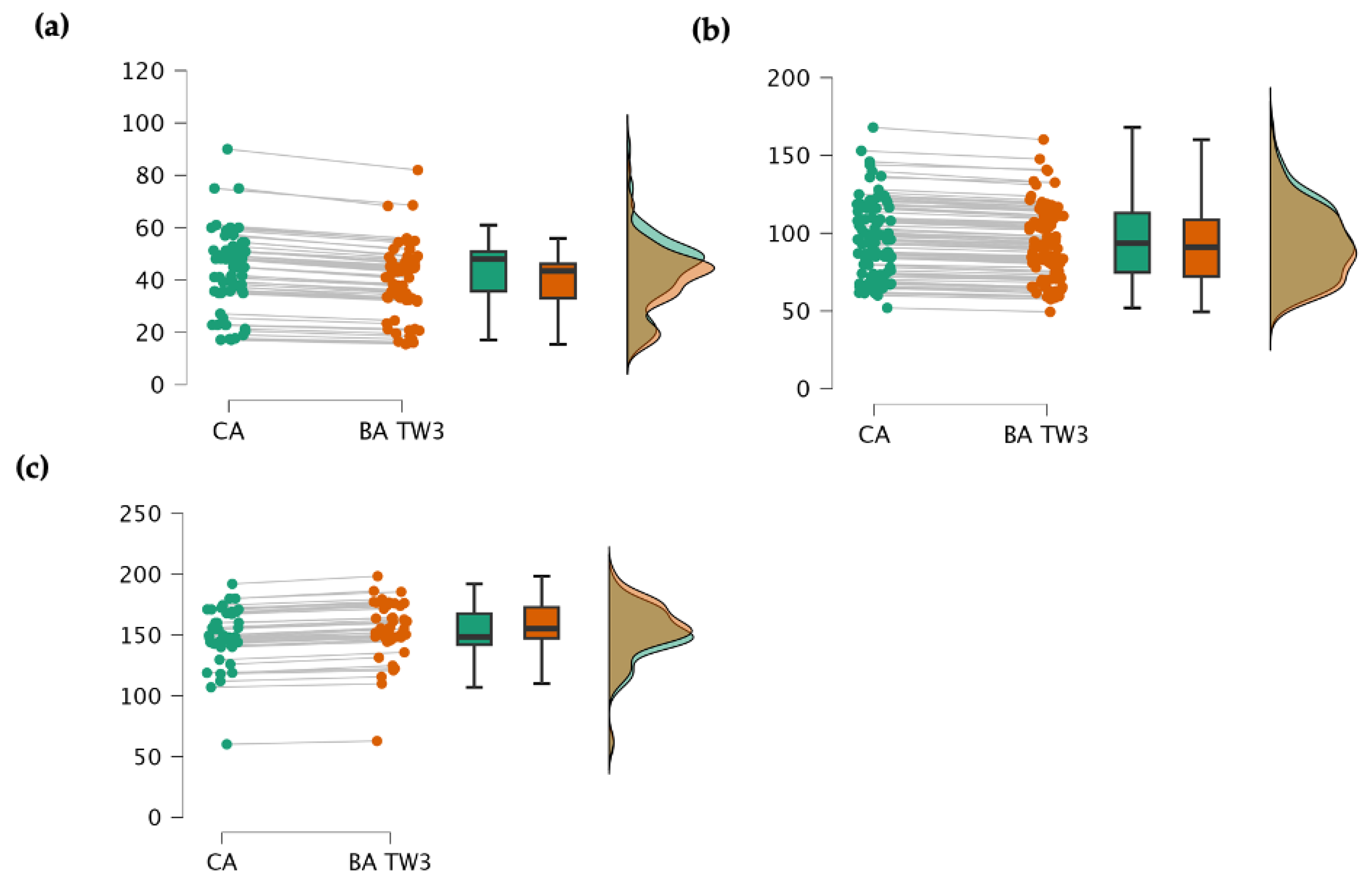

| Stage | Mean | SD | MD | Lower CI 95% |

Superior CI 95% |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preschool (n = 69) | CA | 43.485 | 14.476 | ||||

| BA | 39.772 | 15.409 | 3.712 | 1.290 | 6.130 | 0.199 | |

| Female | CA | 39.331 | 15.182 | ||||

| BA | 35.131 | 16.896 | 4.200 | 0.780 | 7.620 | 0.164 | |

| Male | CA | 46.496 | 13.333 | ||||

| BA | 46.390 | 24.881 | 0.106 | -4.830 | 5.05 | 0.935 | |

| Scholar (n = 102) | CA | 95.684 | 23.906 | ||||

| BA | 92.161 | 35.572 | 3.522 | 1.050 | 5.990 | 0.888 | |

| Female | CA | 92.001 | 26.086 | ||||

| BA | 87.891 | 37.203 | 4.110 | -8.250 | 16.47 | 0.945 | |

| Male | CA | 100.168 | 20.338 | ||||

| BA | 96.190 | 33.876 | 3.978 | -12.55 | 4.59 | 0.926 | |

| Teenager (n = 43) | CA | 148.883 | 23.665 | ||||

| BA | 149.242 | 29.943 | −0.360 | -0.770 | −0.954 | 0.299 | |

| Female | CA | 144.170 | 23.810 | ||||

| BA | 144.549 | 24.231 | −0.380 | -4.840 | 5.500 | 0.256 | |

| Male | CA | 151.53 | 20.176 | ||||

| BA | 151.86 | 18.179 | −0.330 | -1.03 | 1.78 | 0.222 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).