1. Introduction

Consider the first-order difference equations with several advanced arguments

where

denotes the set of positive integers and

is the backward difference operator. Throughout the paper, the coefficient sequences

,

, are assumed to be nonnegative real-valued for all sufficiently large

n. Moreover, the integer-valued sequences

represent advanced arguments and satisfy

A sequence

, for some

, is said to be a solution of equation (

1) if it satisfies the equation for all

.

The oscillation theory of differential and difference equations provides fundamental insights into the qualitative behavior of dynamical systems across diverse domains, including population dynamics, control systems, biological feedback or feedforward mechanisms [

24,

31], neural modeling [

30,

33], and economics, see [

2,

23,

28,

29]. The analysis of oscillatory behavior enables researchers to determine whether solutions fluctuate around equilibrium states or converge monotonically, thereby revealing underlying stability properties, periodic tendencies, or chaotic dynamics in physical and biological processes. In discrete systems, oscillation analysis assumes particular significance, as many real-world models evolve through discrete time steps and incorporate delay or advance arguments to capture memory effects or anticipation mechanisms, see [

2,

23].

The study of oscillation in difference equations plays an essential role in discrete mathematics, and its development has been addressed in a wide range of contributions; see [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

18,

19,

20,

22,

23,

25,

26,

27,

32,

34,

35,

36,

37]. While classical results typically assume single monotone arguments, realistic systems often involve several advanced arguments that may vary non-monotonically over time. Such complex structures arise naturally in predictive control systems, biological population models with anticipation mechanisms, and signal propagation through feedback networks [

10,

20,

31].

Ladas [

27] investigated the oscillatory behavior of the first-order differential equation with non-decreasing delay

and established the well-known lim sup-type oscillation criterion

Motivated by the continuous case, Chatzarakis and Stavroulakis [

21] extended Ladas’ condition to the discrete setting. In particular, they obtained the following discrete analogue of (

2):

for the advanced difference equation

where

is a sequence of nonnegative real numbers and

is an integer-valued non-decreasing sequence satisfying

Subsequently, Chatzarakis, Pinelas, and Stavroulakis [

14] extended condition (

3) to Eq. (

1) and obtained

where

and each

represents a non-decreasing sequence.

Braverman and Karpuz [

9] demonstrated that condition (

2) is not valid for both the continuous and the corresponding discrete cases when the assumption of monotonicity is relaxed to allow for general, not necessarily monotone, delay arguments. This finding highlights the limitations of directly extending results from monotone to non-monotone delays and shows that more specific methods are required for equations with non-monotone arguments [

25,

26].

Despite notable progress in the oscillation theory of delay difference equations, the case involving several advanced arguments remains insufficiently explored. Existing studies [

1,

9] present only sufficient conditions for the oscillation of all solutions; however, they do not reveal the qualitative differences between equations with one or with several advanced arguments. Following the approach in [

9], we construct a counterexample showing that some extensions of condition (

3) cannot hold for Eq. (

1), even when the advanced arguments are non-decreasing and satisfy

. In this work, we show that there is no constant

such that any of the following conditions guarantees the oscillation of all solutions of Eq. (

1):

or

This paper has two additional goals. First, we develop a new framework for studying oscillatory behavior and obtain new sufficient conditions that extend and unify earlier results (see

Table 1 on page 7). Second, we show that, for a certain class of equations of the form (

1), some of our criteria guarantee oscillation, while all previously known conditions, whether iterative or not, fail for this class. Finally, we introduced a new concept for difference equations with advanced arguments, namely, the distance between generalized successive zeros of solutions, illustrated through numerical simulations.

2. Main Results

Theorem 1.

None of the following conditions, for any constant , guarantees the oscillation of Eq. (1) when is non-decreasing for all and :

Proof. Consider the first–order difference equation with several advanced arguments

It is evident that this equation is a particular case of (

1), with

The above equation possesses a non-oscillatory solution

Furthermore, we obtain

and similarly,

As the integer

M may be taken arbitrarily large, the proof of the theorem is complete. □

In what follows, and throughout the remainder of this work, we assume that

, for

, are integer-valued (it is not necessarily assumed to be non-decreasing). Accordingly, we introduce the non-decreasing sequences

Furthermore, for integers

, we define

The following lemma provides an iterative sequence of lower bounds for the ratio

, which progressively increases as

k increases. The proof of this Lemma, for difference equation with several delays, can be found in [

10].

Lemma 1.

Assume that is a positive solution of Eq. (1). Then for all , , we have

Proof. Dividing Eq. (

1) by

and taking the product from

to

p, we obtain

Since the sequence

is positive, it follows from Eq. (

1) that

is eventually non-decreasing. Consequently,

Hence, from (

8) we have

Moreover, since

, it follows that

Substituting this estimate into (

8) and rearranging the terms yields

Proceeding inductively in this manner, we finally arrive at inequality (

7). □

Theorem 2. (Main oscillation criterion for several non-monotone advanced arguments)

Let . Suppose that there exists an unbounded sequence such that

Then Eq. (1) is oscillatory.

Proof. Assume, for the sake of contradiction, that Eq. (

1) possesses a non-oscillatory solution

. Without loss of generality, we may suppose that

for all sufficiently large values of

n. Hence,

is eventually non-increasing for all sufficiently large

n.

Summing Eq. (

1) from

n to

,

, yields

By virtue of inequality (

7) and the fact that

for all

, it follows that

Substituting this estimate into the previous equality gives

Summing this inequality for

, we obtain

Now, according to condition (

9), there exists a sufficiently large

i such that

Combining this fact with inequality (

11) yields a contradiction that completes the proof. □

Theorem 3.

Assume that for , , . If

then, Eq. (1) is oscillatory.

Proof. By applying the same approach employed in the proof of Theorem 2, we deduce that

where

and

is a positive solution of Eq. (

1). Using the inequality

for all

, and summing over

, we get

that is,

Consequently,

Therefore,

contradicts (

12). □

It is straightforward to reorder the sequences

and

, for

, associated with Eq. (

1), so that the following inequality is eventually satisfied:

Theorem 4.

Let and . Assume that there exists an unbounded sequence such that

Then Eq. (1) is oscillatory.

Proof. As before, let

denote a positive solution of Eq. (

1). From Eq. (

1), it immediately follows that

Following the same arguments as in the proof of Theorem 2, and using (

7) with

for all

, summing from

ℓ to

m yields

From this and condition (

14), we arrive at a contradiction, which completes the proof of the theorem. □

Remark 1.

It is worth noting that one of the significant consequences of Theorem 1 is that none of the conditions

or

where each denotes a non-decreasing sequence of positive integers, is a necessary condition for the non-oscillation of Eq. (1).

3. Numerical Results and Simulations

In this section, we provide a comparative analysis between our results and those reported in previous studies, as summarized in

Table 1. It is clear that all existing works establish only sufficient conditions for the oscillation of Eq. (

1). In contrast, our results not only yield new and sharper oscillation criteria but also reveal that certain formulates are not sufficient to ensure the oscillatory behavior of all solutions of Eq. (

1).

We also present two numerical examples to demonstrate the validity and sharpness of the obtained results. The first example applies one of the main theorems to show that a class of difference equations of the form (

1) is oscillatory, while previously known criteria fail to detect this behavior; several solution simulations and graphical representations further illustrate the oscillatory nature and identify regions where earlier conditions are ineffective. The second example addresses a qualitative property that, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, has not been previously studied for difference equations advanced arguments, namely the distance between generalized zeros, and the simulations indicate that this distance decreases as the sequence of coefficients increases, highlighting the relevance of this property for a deeper understanding of the solution dynamics.

Example 1.

Consider the first-order difference equation with several advanced arguments

where

and

where

, and

denotes the greatest integer less than or equal to

.

Furthermore,

, and

where

,

, and the sequence

satisfies

It follows directly that condition (

13) holds, and

Consequently, for

, we obtain

Therefore, condition (

14) is satisfied with

, and hence Eq. (

17) is oscillatory.

However, as will be demonstrated below, all known iterative and non-iterative oscillation criteria fail to establish the oscillatory behavior of Eq. (

17). For example,

where

. Therefore,

Consequently, ([

14] Theorem 3.2) cannot be applied to Eq. (

17). Furthermore, we observe that

and

Moreover, define

Therefore,

and

Similarly,

Consequently,

for sufficiently small

and

. Hence, [

17] (Theorem 2.7) is not satisfied.

Likewise, it can be shown that the remaining oscillation conditions are not satisfied for Eq. (

17).

This example demonstrates that condition (

14) yields sharper results than existing ones. The numerical results confirm the oscillatory behavior of Eq. (

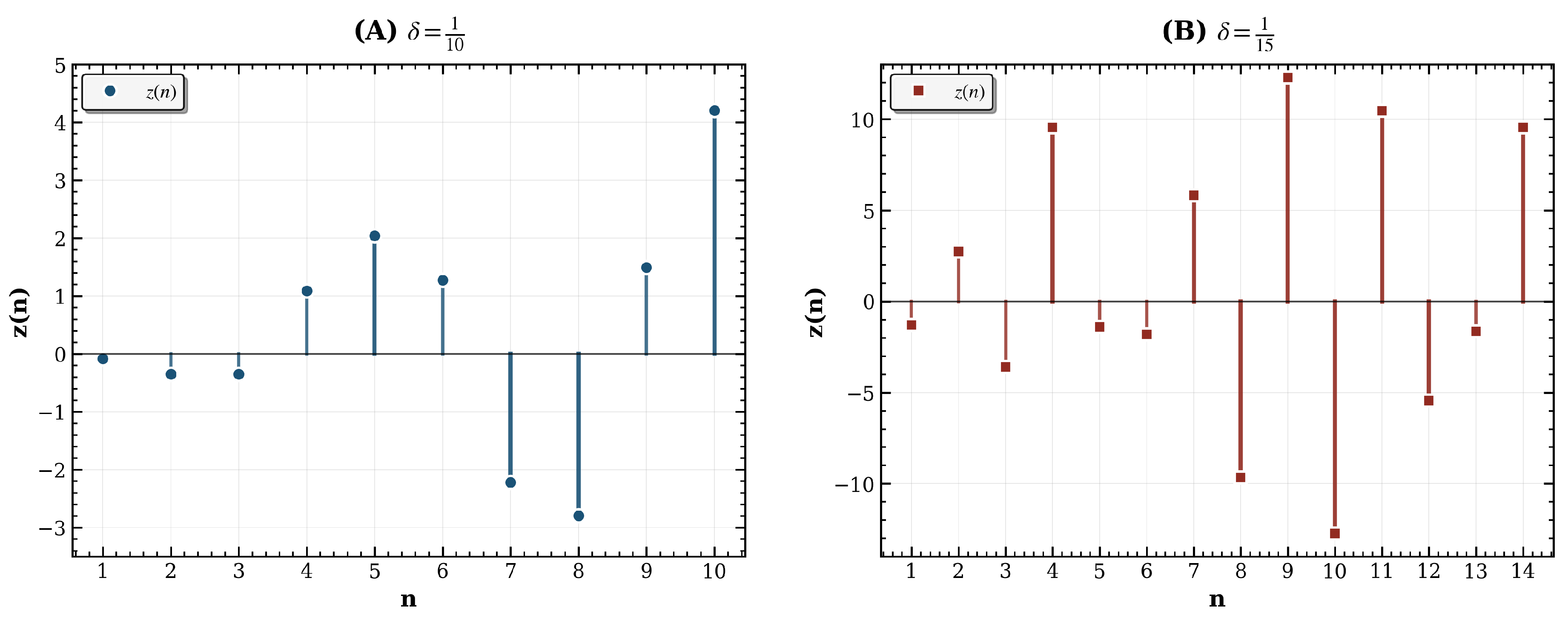

17). As seen in

Figure 1, the solution

oscillates for

and

with

, while smaller

leads to more sign changes, motivating further study of the

distance between generalized zeros (see Example 2).

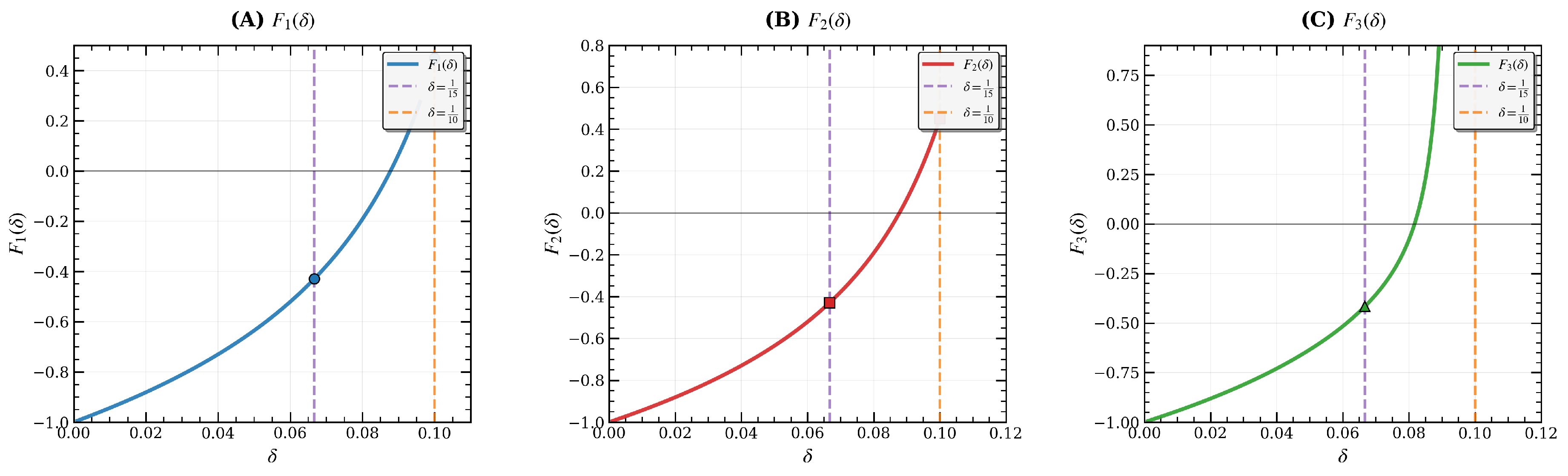

In addition, we illustrate, through several graphical representations, a comparison between condition (

14) and [

17] (Theorem 2.7). Specifically, we define the function

where

. We plot the relationship between

and the parameter

. As illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Table 2, the oscillation condition of [

17] (Theorem 2.7), for

and 3, is not satisfied on the intervals

respectively. However, as shown above, Eq. (

17) is oscillatory for all

and

.

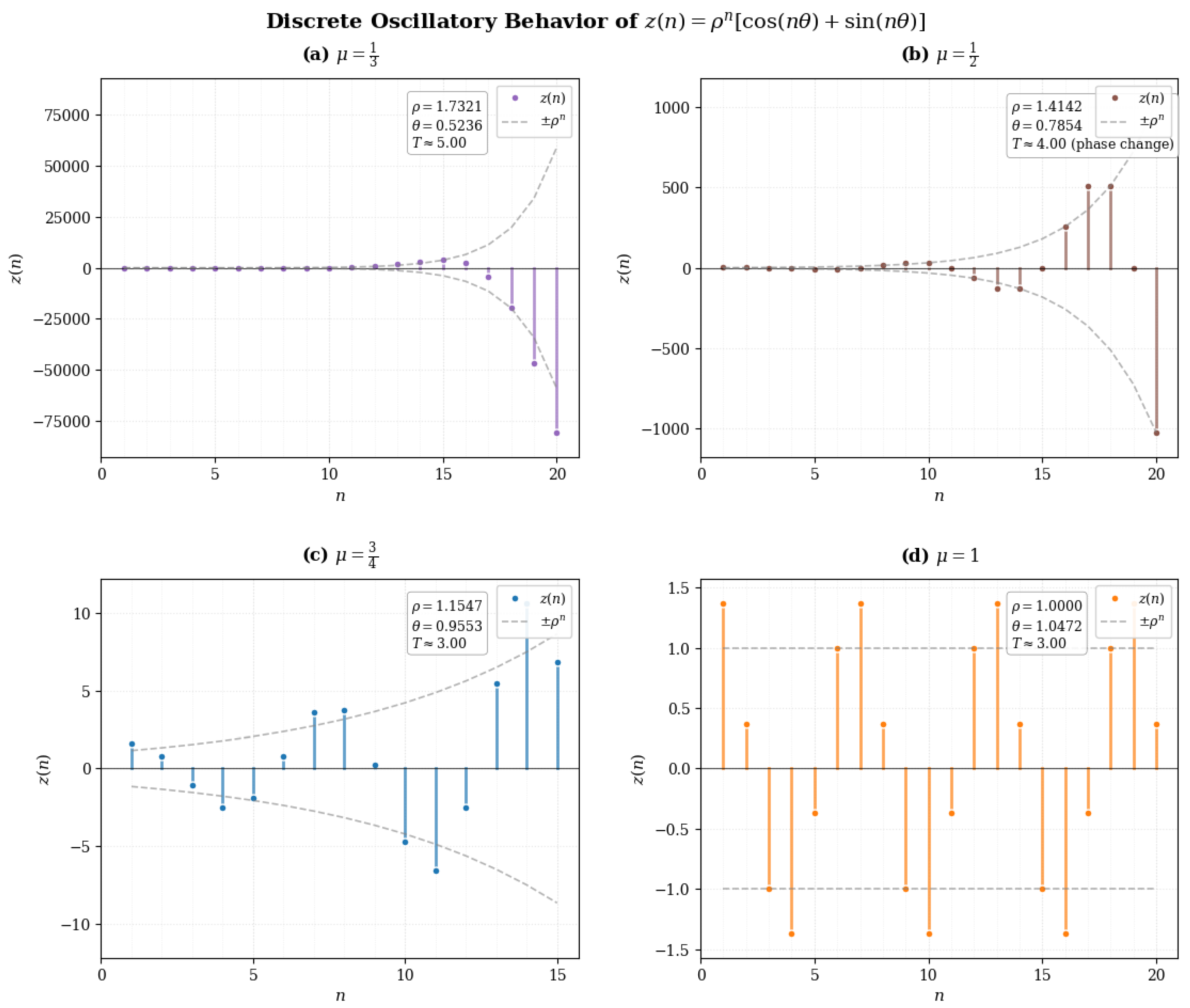

Example 2.

Consider the difference equation with advanced argument

This equation represents a particular case of Eq. (

4) with

and

. Numerical simulations of Eq. (

18) reveal a clear dependence between the parameter

and the distance between consecutive generalized zeros of the solutions. Here, a generalized zero is a positive integer at which the solution is zero or has a different sign than at the preceding integer. The numerical results show that the maximum interval length

T, over which the solution remains positive (or negative), decreases as

increases. Specifically, for

, the corresponding lengths are

and 3, respectively (see

Figure 3). These findings highlight the importance of examining the spacing between successive generalized zeros in advanced-type difference equations, as such an analysis provides deeper insight into the qualitative oscillatory dynamics of these equations.

Conclusion

In this work, we obtained new oscillation criteria for first–order difference equations with several, not necessarily monotone, advanced arguments. Our results substantially strengthen and extend the existing results in the literature. Theorem 1 shows that there are fundamental differences between equations with a single advanced argument and those with several advanced arguments. Moreover, the analytical approach presented here is sufficiently flexible to be applied to further qualitative investigations, including the study of the distribution of generalized zero and related properties of difference equations with generalized delays or advanced arguments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.N. and E.R.A.; methodology, M.T.N. and E.R.A.; software, M.T.N. and E.R.A.; validation, M.T.N., E.R.A. and G.E.C.; formal analysis, M.T.N. and E.R.A.; investigation, M.T.N. and E.R.A.; resources, M.T.N. and E.R.A.; data curation, M.T.N. and E.R.A.; writing original draft preparation, M.T.N., E.R.A. and G.E.C.; writing, review and editing, M.T.N., E.R.A. and G.E.C.; visualization, M.T.N. and E.R.A.; supervision, E.R.A.; project administration, E.R.A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, project number PSAU/2025/01/31196. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was also funded by Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study does not involve human participants or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants.

Data Availability Statement

This is a theoretical study in the field of mathematics. No new data were created or analyzed in this work. Therefore, data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this work through project number (PSAU/2025/01/31196).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DE |

Difference Equation |

| NDE |

Neutral Difference Equation |

| 1st-order |

First-order |

| non-monot. |

Non-monotone |

| args. |

Arguments |

| e.g. |

For example (exempli gratia) |

| i.e. |

That is (id est) |

| etc. |

And so forth (et cetera) |

| cf. |

Compare (confer) |

| lim inf |

Limit inferior |

| lim sup |

Limit superior |

| w.l.o.g. |

Without loss of generality |

| w.r.t. |

With respect to |

| resp. |

Respectively |

References

- Agarwal, R.P.; O’Regan, D.; Wong, P.J.Y. Positive solutions of differential, difference and integral equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2005, 300, 465–483. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R.P.; Grace, S.R.; O’Regan, D. Oscillation Theory for Difference and Functional Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, E.R. New oscillation results for first-order nonlinear difference equations with retarded arguments. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2024, 32, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, E.R.; Chatzarakis, G.E. Oscillation tests for difference equations with non-monotone retarded arguments. Appl. Math. Lett. 2022, 123, 107551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, E.R.; El-Matary, B.M. New aspects for the oscillation of first-order difference equations with deviating arguments. Opusc. Math. 2022, 42, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, E.R.; El-Matary, B.M.; Chatzarakis, G.E. New oscillation conditions for first-order linear retarded difference equations with non-monotone arguments. Opusc. Math. 2022, 42, 769–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benekas, V.; Garab, Á.; Kashkynbayev, A.; Stavroulakis, I.P. Oscillation criteria for linear difference equations with several variable delays. Opusc. Math. 2021, 41, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezansky, L.; Braverman, E. On existence of positive solutions for linear difference equations with several delays. Adv. Dyn. Syst. Appl. 2006, 1, 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Braverman, E.; Karpuz, B. On oscillation of differential and difference equations with non-monotone delays. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 218, 3880–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, E.; Chatzarakis, G.E.; Stavroulakis, I.P. Iterative oscillation tests for difference equations with several non-monotone arguments. J. Difference Equ. Appl. 2015, 21, 854–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Koplatadze, R.; Stavroulakis, I.P. Oscillation criteria of first-order linear difference equations with delay argument. Nonlinear Anal. 2008, 68, 994–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Philos, Ch.G.; Stavroulakis, I.P. An oscillation criterion for linear difference equations with general delay argument. Port. Math. 2009, 66, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Manojlović, J.; Pinelas, S.; Stavroulakis, I.P. Oscillation criteria of difference equations with several deviating arguments. Yokohama Math. J. 2014, 60, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Pinelas, S.; Stavroulakis, I.P. Oscillations of difference equations with several deviated arguments. Aequat. Math. 2014, 88, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Kusano, T.; Stavroulakis, I.P. Oscillation conditions for difference equations with several variable arguments. Math. Bohem. 2015, 140, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Jadlovská, I. Improved iterative oscillation tests for first-order deviating difference equations. Int. J. Difference Equ. 2017, 12, 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Jadlovská, I. Oscillations in difference equations with several arguments using an iterative method. Filomat 2018, 32, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Jadlovská, I. Difference equations with several non-monotone deviating arguments: Iterative oscillation tests. Dyn. Syst. Appl. 2018, 27, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Horvat-Dmitrović, L.; Pašić, M. Oscillation tests for difference equations with several non-monotone deviating arguments. Math. Slovaca 2018, 68, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Pašić, M. Improved iterative oscillation tests in difference equations with several arguments. J. Difference Equ. Appl. 2019, 25, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Stavroulakis, I.P. Oscillations of difference equations with general advanced argument. Cent. Eur. J. Math. 2012, 10, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzarakis, G.E.; Grace, S.R.; Jadlovská, I. Oscillation tests for linear difference equations with non-monotone arguments. Tatra Mt. Math. Publ. 2021, 79, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaydi, S.N. An Introduction to Difference Equations, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Karatas, M.; Noblet, V.; Nasseef, M.T.; et al. Mapping the living mouse brain neural architecture: Strain-specific patterns of brain structural and functional connectivity. Brain Struct. Funct. 2024, 226, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpuz, B. Sharp oscillation and nonoscillation tests for linear difference equations. J. Difference Equ. Appl. 2017, 23, 1929–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitić, N.; Öcalan, Ö. Oscillation criteria for difference equations with several arguments. Int. J. Difference Equ. 2020, 15, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ladas, G. Sharp conditions for oscillations caused by delays. Appl. Anal. 1979, 9, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Frassu, S.; Viglialoro, G. Combining effects ensuring boundedness in an attraction–repulsion chemotaxis model with production and consumption. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 2023, 74, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Pintus, N.; Viglialoro, G. Properties of solutions to porous medium problems with different sources and boundary conditions. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 2019, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupinsky, D.; Nasseef, M.T.; et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals altered functional connectivity associated with resilience and susceptibility to chronic social defeat stress in the mouse brain. Mol. Psychiatry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasseef, M.T. Measuring Directed Functional Connectivity in Mouse fMRI Networks Using Granger Causality

. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Trento, Trento, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pinelas, S.; Dix, J.G. Oscillation of solutions to non-linear difference equations with several advanced arguments. Opusc. Math. 2017, 37, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanpour, S.; Utama, R.; Chang, A.; Nasseef, M.T.; et al. SST-DUNet: Automated preclinical functional MRI skull stripping using smart Swin transformer and dense UNet. J. Neurosci. Methods 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroulakis, I.P. Oscillations of delay difference equations. Comput. Math. Appl. 1995, 29, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroulakis, I.P. Oscillation criteria for delay and difference equations with non-monotone arguments. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 226, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Dix, J.G. Oscillation of nabla difference equations with several delay arguments. Int. J. Difference Equ. 2019, 14, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.G.; Tian, C.J. Nonexistence and existence of positive solutions for difference equations with unbounded delay. Comput. Math. Appl. 1998, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).