Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

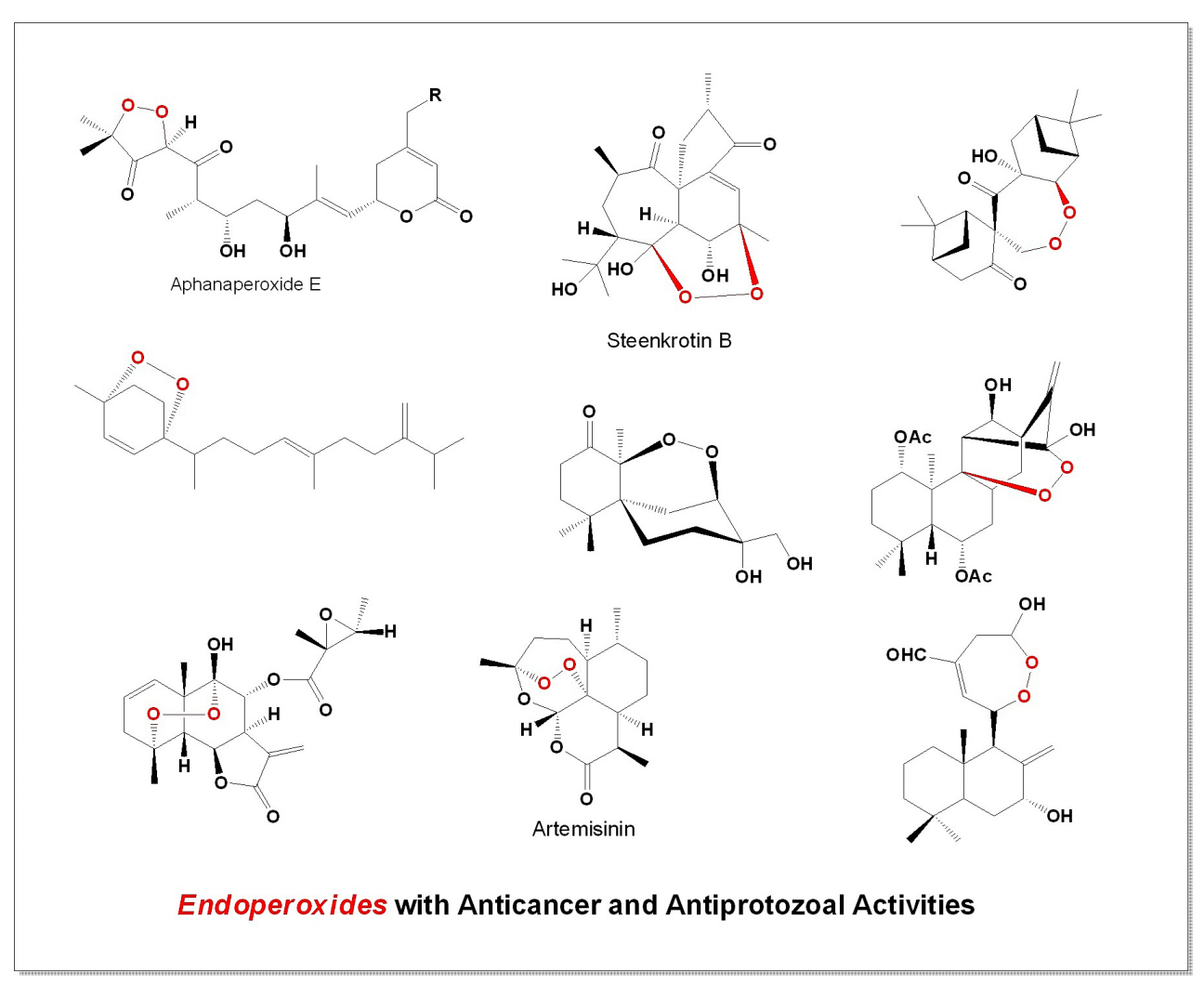

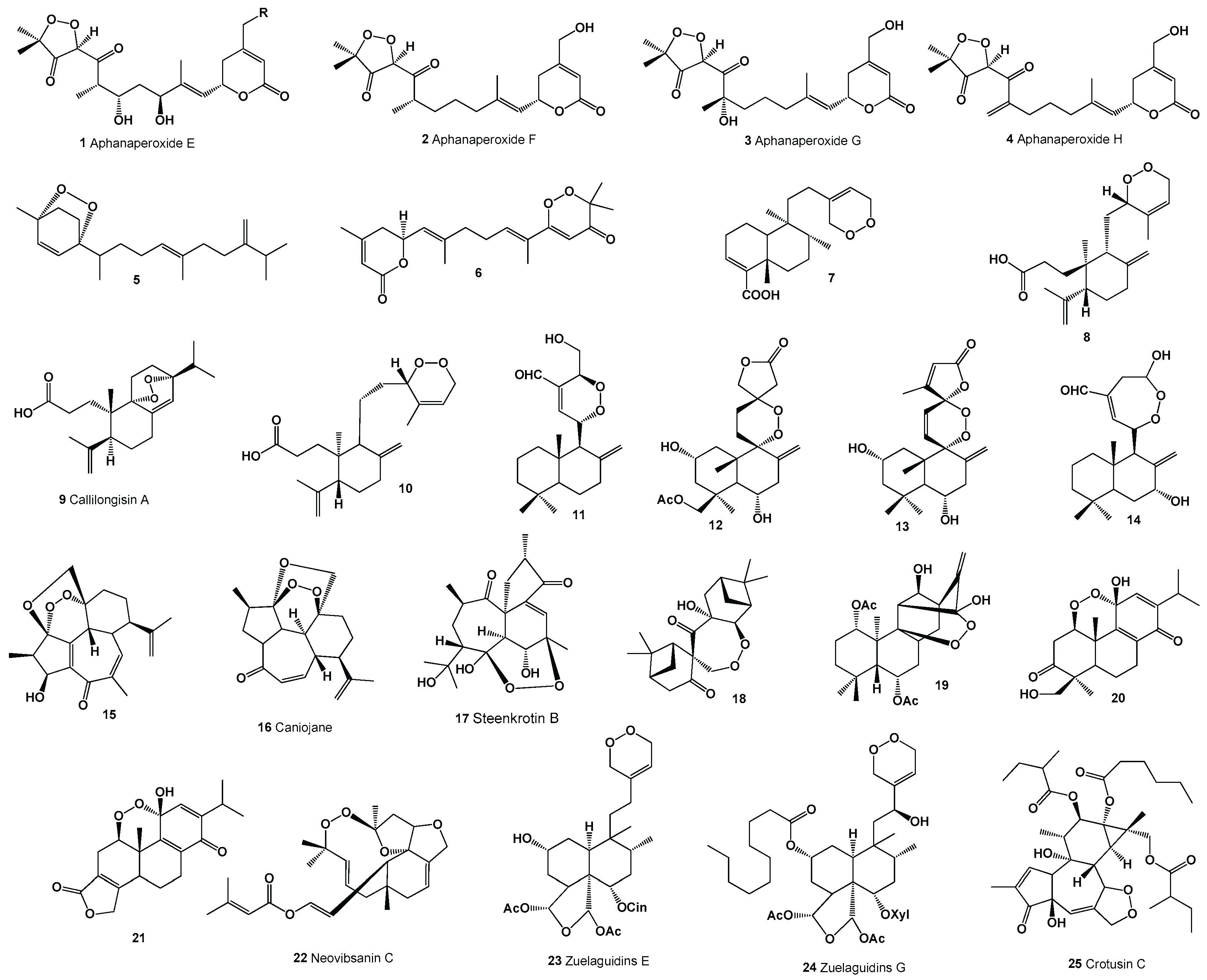

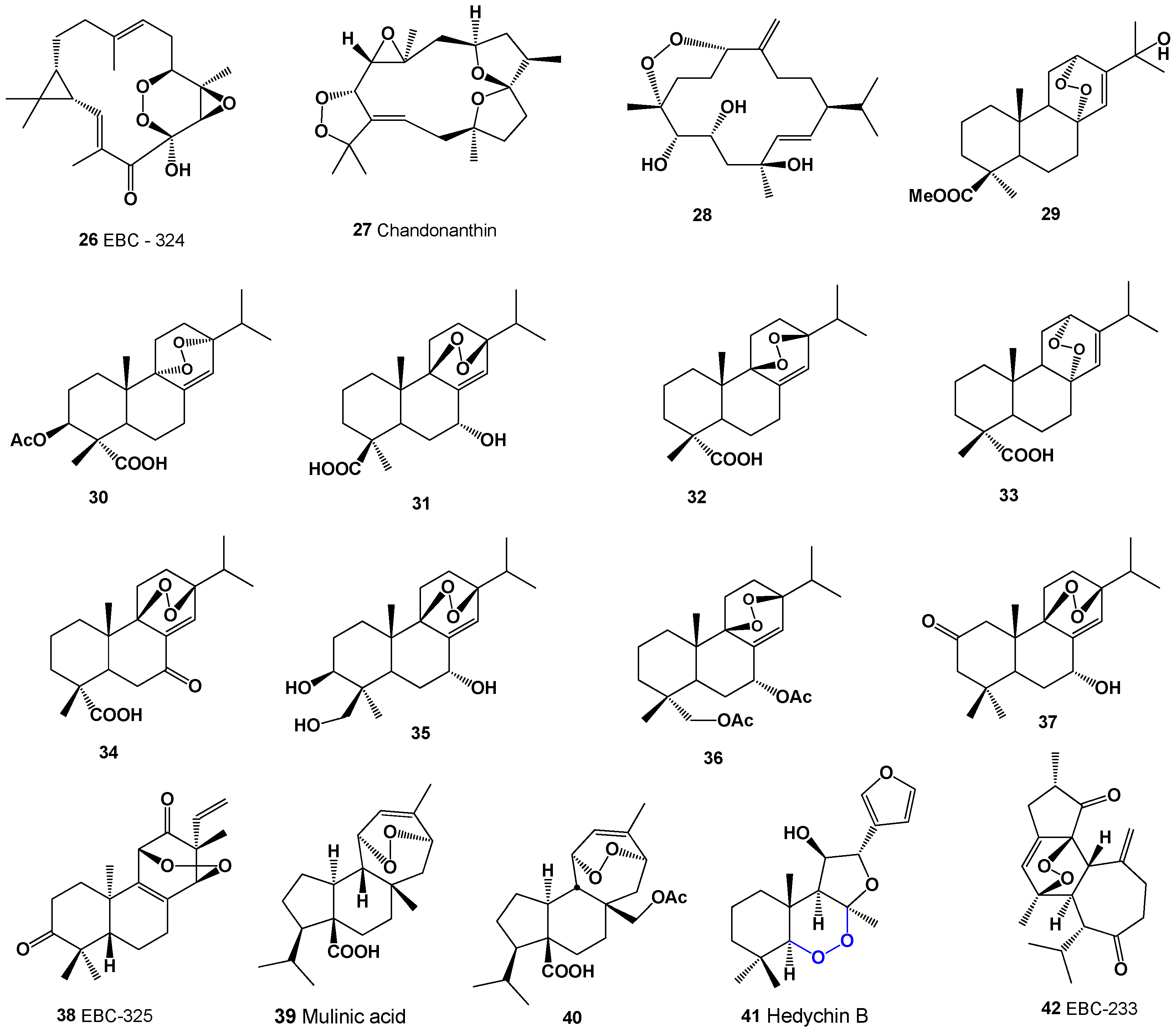

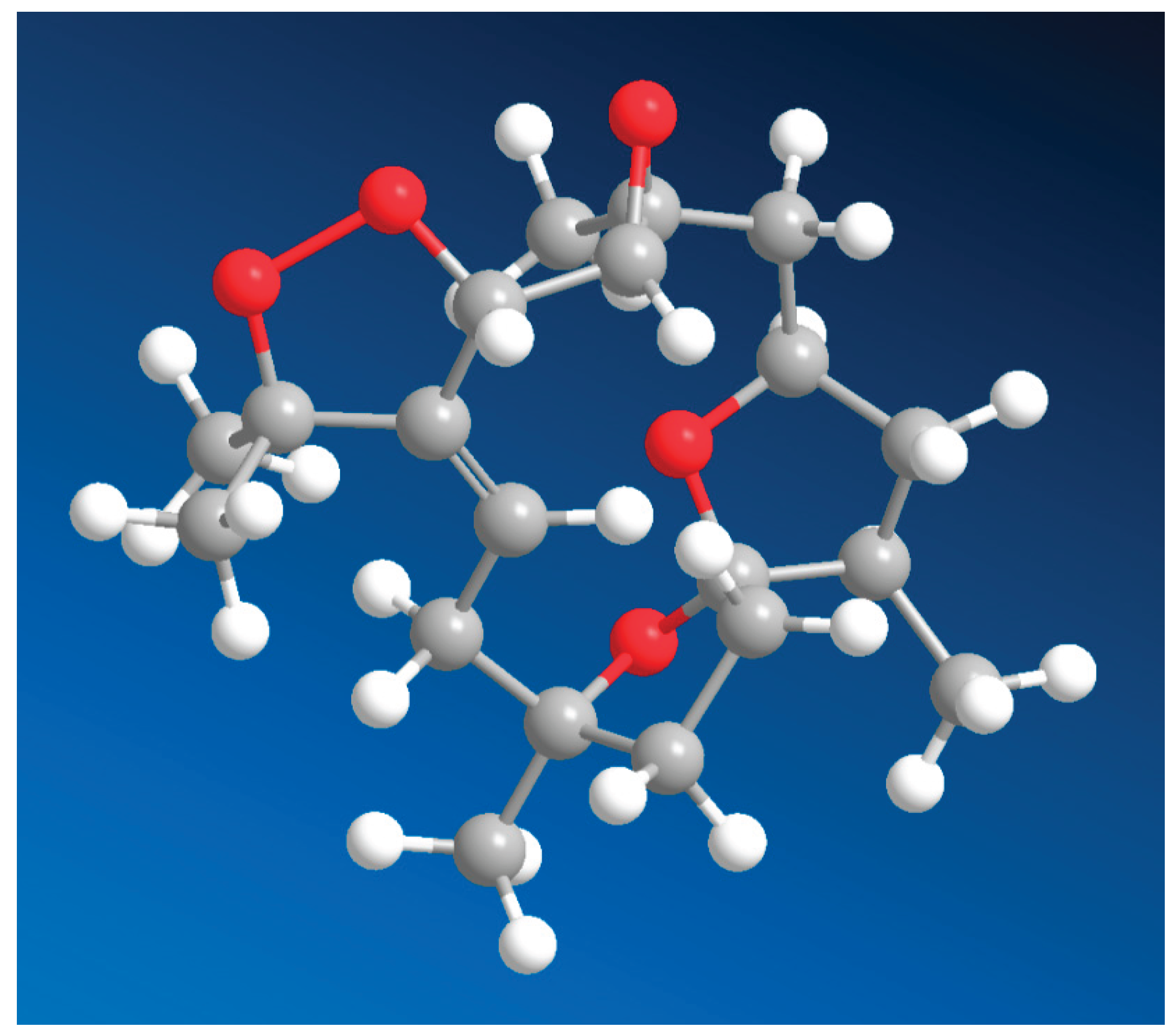

1. Introduction

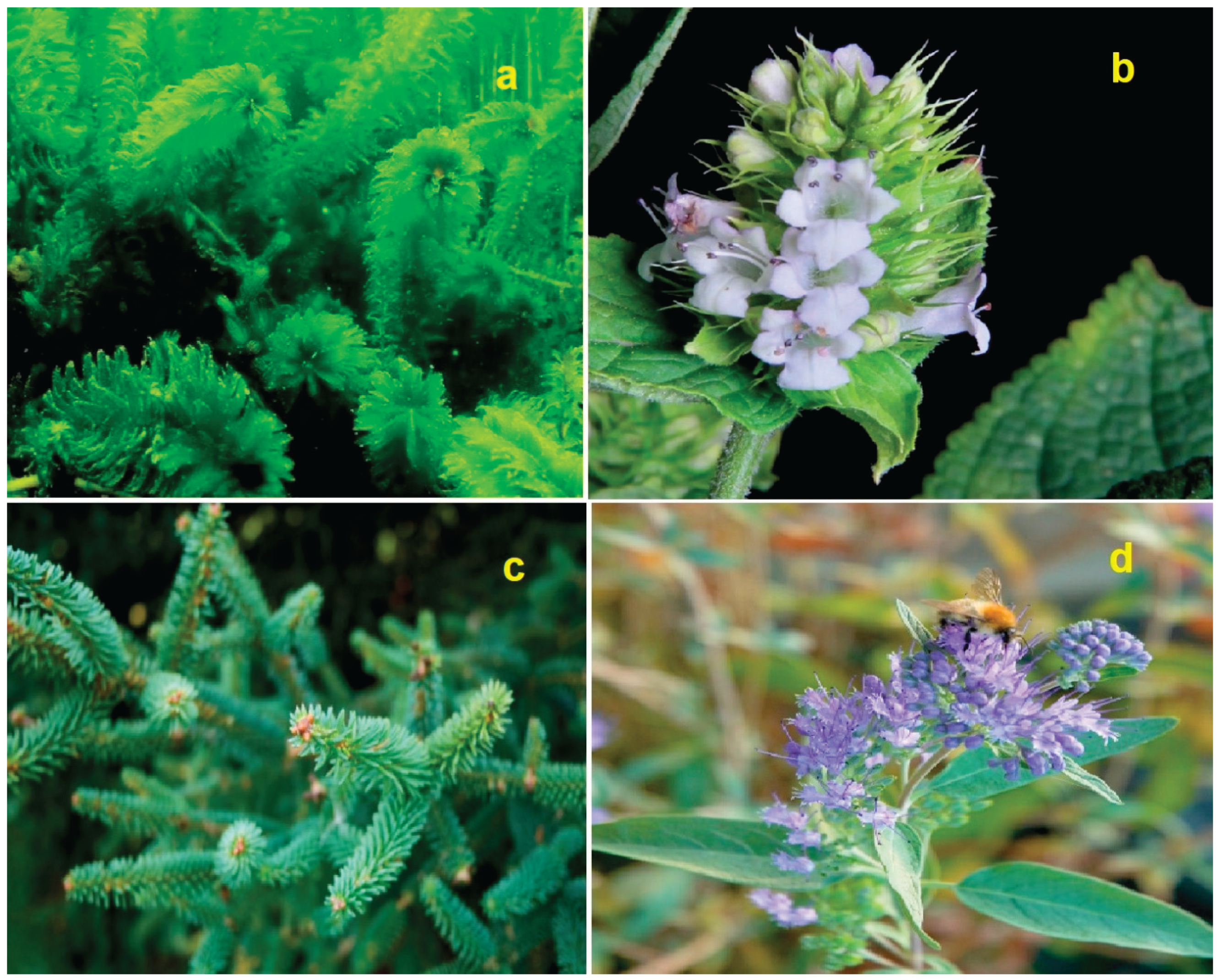

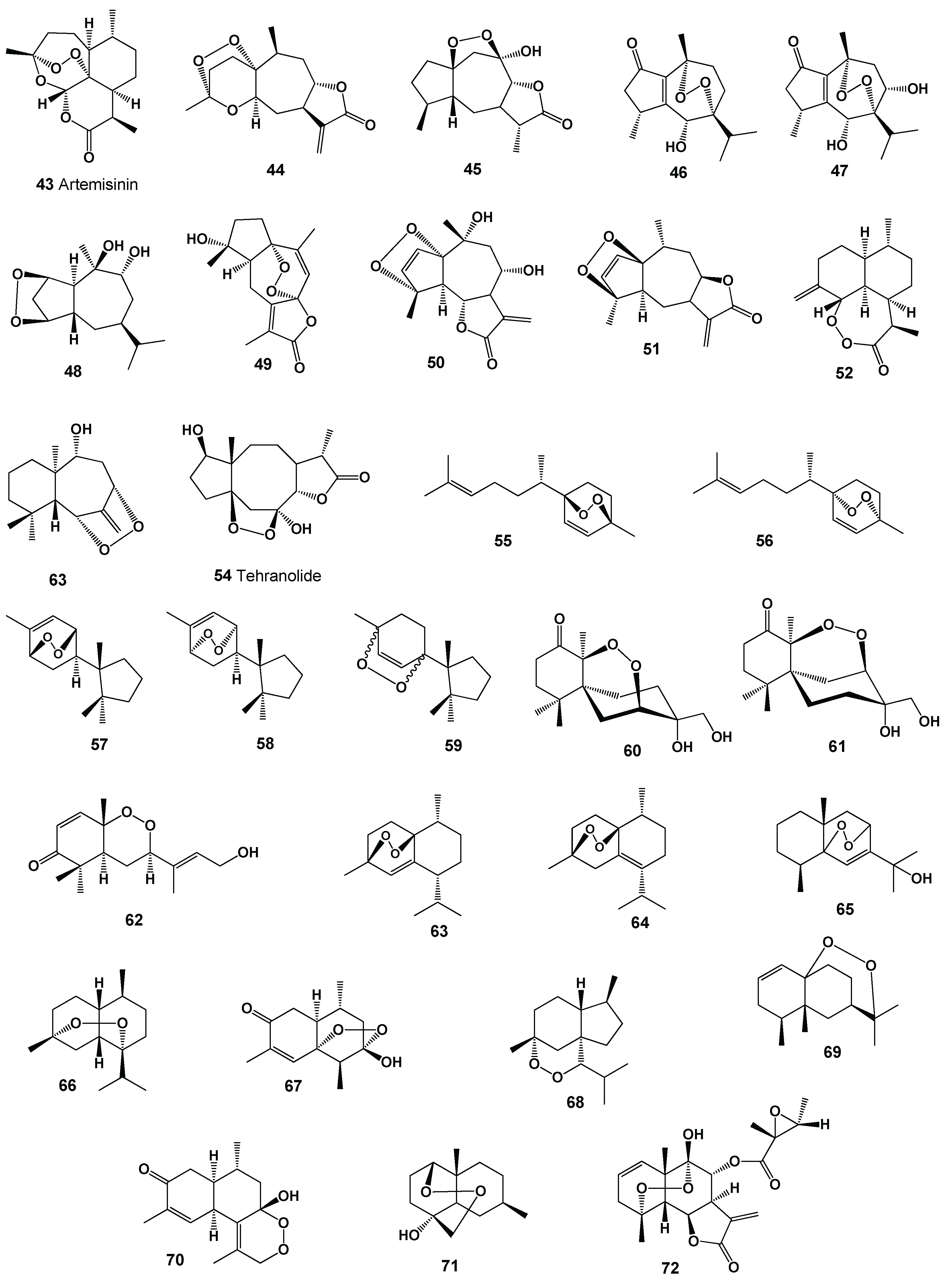

2. Distribution in Nature

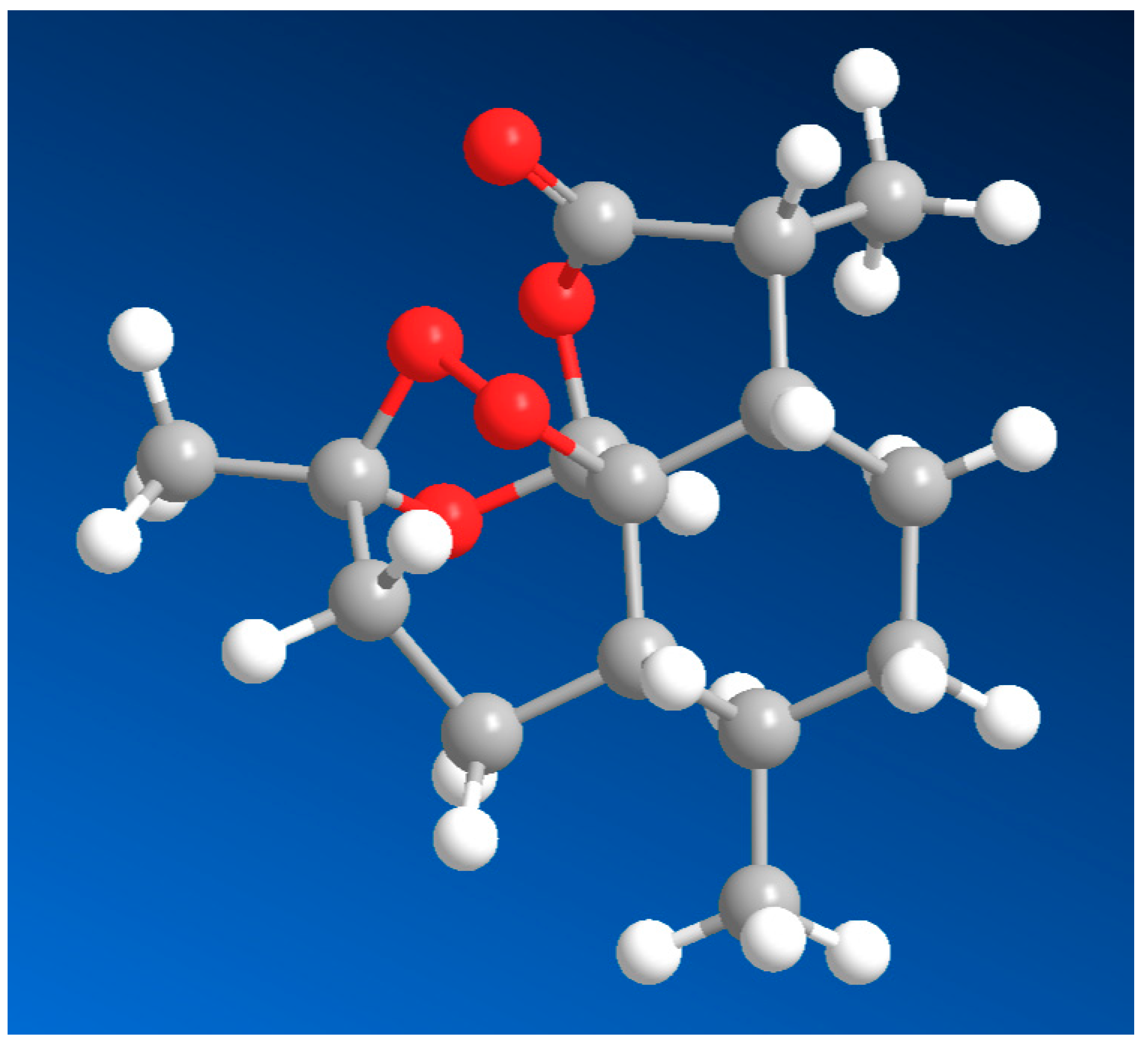

3. Comparison of the Biological Activity of Endoperoxides

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dembitsky, V.M. Highly oxygenated cyclobutane ring in biomolecules: Insights into structure and activity. Oxygen 2024, 4, 181–235. [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.; Gohr, S.T.; Köllner, T.G.; Bathe, U.; Lackus, N.D.; Padilla-Gonzalez, F.; Tissier, A. Biosynthesis of biologically active terpenoids in the mint family (Lamiaceae). Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, 42, 1887–1908. [CrossRef]

- Câmara, J.S.; Perestrelo, R.; Ferreira, R.; Berenguer, C.V.; Pereira, J.A.; Castilho, P.C. Plant-derived terpenoids: A plethora of bioactive compounds with several health functions and industrial applications—A comprehensive overview. Molecules 2024, 29, 3861. [CrossRef]

- Saber, F.R.; Salehi, H.; Khallaf, M.A.; Rizwan, K.; Gouda, M.; Ahmed, S.; Simal-Gandara, J. Limonoids: Advances in extraction, characterization, and applications. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1–62. [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Ermolenko, E.; Savidov, N.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Antiprotozoal and antitumor activity of natural polycyclic endoperoxides: Origin, structures and biological activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 686. [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Bioactive peroxides as potential therapeutic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 223–251. [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Bioactive fungal endoperoxides. Med. Mycol. 2015, 53, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Vil, V.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Poroikov, V.V.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Savidov, N.; Dembitsky, V.M. Peroxy steroids derived from plants and fungi and their biological activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7657–7667. [CrossRef]

- Vil, V.A.; Yaremenko, I.A.; Ilovaisky, A.I.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Dembitsky, V.M. Peroxides with anthelmintic, antiprotozoal, fungicidal and antiviral bioactivity: Properties, synthesis and reactions. Molecules 2017, 22, 1881. [CrossRef]

- Terent’ev, A.O.; Borisov, D.A.; Vil, V.A. Synthesis of five- and six-membered cyclic organic peroxides: Key transformations into peroxide ring-retaining products. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 34–114. [CrossRef]

- Klayman, D.L.; Lin, A.J.; Acton, N.; Scovill, J.P.; Hoch, J.M.; Milhous, W.K.; Theoharides, A.D. Isolation of artemisinin (qinghaosu) from Artemisia annua growing in the United States. J. Nat. Prod. 1984, 47, 715–717. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.F.S.; Janick, J. Distribution of artemisinin in Artemisia annua. Prog. New Crops 1996, 1, 579–584.

- Duke, S.O.; Vaughn, K.C.; Croom, E.M. Jr. Artemisinin, a constituent of annual wormwood (Artemisia annua), is a selective phytotoxin. Weed Sci. 1987, 35, 499–505. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, B.; Qu-Bie, A.; Li, M.; Luo, M.; Feng, M.; Liu, Y. Endoperoxidases in biosynthesis of endoperoxide bonds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 136, 136806. [CrossRef]

- Mannan, A.; Liu, C.; Arsenault, P.R. DMSO triggers the generation of ROS leading to an increase in artemisinin and dihydroartemisinic acid in Artemisia annua shoot cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2010, 29, 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Kuehl, F.A., Jr.; Humes, J.L.; Egan, R.W. Role of prostaglandin endoperoxide PGG₂ in inflammatory processes. Nature 1977, 265, 170–173. [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.L.; Urade, Y.; Jakobsson, P.-J. Enzymes of the cyclooxygenase pathways of prostanoid biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5821–5865. [CrossRef]

- Caruana, A.; Savona-Ventura, C.; Calleja-Agius, J. COX isozymes and non-uniform neoangiogenesis: What is their role in endometriosis? Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2023, 167, 106734. [CrossRef]

- Barsegyan, Y.A.; Vil, V.A.; Terent’ev, A.O. Macrocyclic organic peroxides: Constructing medium and large cycles with O–O bonds. Chemistry 2024, 6, 1246–1270. [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Vil, V.A. Medicinal chemistry of stable and unstable 1,2-dioxetanes: Origin, formation, and biological activities. Sci. Synth. Knowl. Updates 2019, 38, 333–381.

- Clennan, E.L. Aromatic endoperoxides. Photochem. Photobiol. 2023, 99, 204–220. [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Yaremenko, I.A. Stable and unstable 1,2-dioxolanes: Origin, synthesis, and biological activities. Sci. Synth. Knowl. Updates 2020, 38, 277–321.

- Yaremenko, I.A.; Vil, V.A.; Demchuk, D.V.; et al. Rearrangements of organic peroxides and related processes. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 1647–1748. [CrossRef]

- Tamez-Fernández, J.F.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Ibarra-Rivera, T.R.; et al. Plant-derived endoperoxides: Structure, occurrence, and bioactivity. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 827–864. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.F.; Zhang, X.P.; Wang, Y.; et al. Four new diterpenes from Aphanamixis polystachya. Fitoterapia 2013, 90, 126–131. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; He, H.P.; Di, Y.T.; et al. Chemical constituents from Aphanamixis grandifolia. Fitoterapia 2014, 92, 100–104. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.L.; Jong, J.R. A cyclic peroxide of clerodenoic acid from the Taiwanese liverwort Schistochila acuminata. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2001, 3, 241–246. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, F.; Takaishi, Y.; Kashiwada, Y.; et al. ent-3,4-seco-Labdane and ent-labdane diterpenoids from Croton stipuliformis (Euphorbiaceae). Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 2406–2410. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.W.; Cheng, Y.B.; Liaw, C.C.; et al. Bioactive diterpenes from Callicarpa longissima. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 689–693. [CrossRef]

- Adelekan, A.M.; Prozesky, E.A.; Hussein, A.A.; et al. Bioactive diterpenes and other constituents of Croton steenkampianus. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1919–1922. [CrossRef]

- Kamchonwongpaisan, S.; Nilanonta, C.; Tarmchampoo, B.; et al. An antimalarial peroxide from Amomum krervanh Pierre. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 1821–1824. [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.B.; Zhu, R.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; et al. ent-Kaurane diterpenoids from the liverwort Jungermannia atrobrunnea. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1418–1422. [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Xi, M.; Li, Y. Triptotin A and B, two novel diterpenoids from Tripterygium wilfordii. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 947–950. [CrossRef]

- Kubo, M.; Minami, H.; Hayashi, E.; et al. Neovibsanin C, a macrocyclic peroxide-containing neovibsane-type diterpene from Viburnum awabuki. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 6261–6265. [CrossRef]

- Calderón, C.; De Ford, C.; Castro, V.; et al. Cytotoxic clerodane diterpenes from Zuelania guidonia. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 455–463. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Yang, K.X.; Yang, X.W.; et al. New cytotoxic tigliane diterpenoids from Croton caudatus. Planta Med. 2016, 82, 729–733. [CrossRef]

- Graikou, K.; Aligiannis, N.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; et al. New diterpenes from Croton insularis. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 685–688. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Harrison, L.J.; Tan, B.C. Terpenoids from the liverwort Chandonanthus hirtellus. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 4035–4043. [CrossRef]

- Arndt, R.; Wahlberg, I.; Enzell, C.R.; et al. Tobacco chemistry: Structure determination and biomimetic syntheses of two new tobacco cembranoids. Acta Chem. Scand. 1988, 42, 294–302. [CrossRef]

- Barrero, A.F.; del Moral, J.F.Q.; Aitigri, M. Oxygenated diterpenes and other constituents from Moroccan Juniperus phoenicea and Juniperus thurifera var. africana. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 2507–2515. [CrossRef]

- Escudero, J.; Pérez, L.; Rabanal, R.M.; et al. Diterpenoids from Salvia oxyodon and Salvia lavandulifolia. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 585–588. [CrossRef]

- Monaco, P.; Parrilli, M.; Previtera, L. Two endoperoxide diterpenes from Elodea canadensis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 4609–4612. [CrossRef]

- Barrero, A.F.; Sánchez, J.F.; Álvarez-Mansaneda, E.J.; et al. Endoperoxide diterpenoids and other constituents from Abies marocana. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 593–597. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, G.; Sánchez, E.; Hernández, J.; et al. Abietanoid acids from Lepechinia caulescens. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 3159–3161. [CrossRef]

- San Feliciano, A.; del Corral, J.M.M.; Gordaliza, M.; et al. Two diterpenoids from the leaves of Juniperus sabina. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 695–697. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.G.; Chou, G.X.; Mao, X.D.; et al. Nepetaefolins A–J, cytotoxic chinane and abietane diterpenoids from Caryopteris nepetaefolia. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 1742–1749. [CrossRef]

- Barrero, A.F.; Quílez del Moral, J.F.; Herrador, M.M.; et al. Abietane diterpenes from the cones of Cedrus atlantica. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 105–111.

- Maslovskaya, L.A.; Savchenko, A.I.; Gordon, V.A.; et al. Isolation and confirmation of the proposed cleistanthol biogenetic link from Croton insularis. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1032–1035. [CrossRef]

- Maslovskaya, L.A.; Savchenko, A.I.; Pierce, C.J.; et al. Unprecedented 1,14-seco-crotofolanes from Croton insularis: Oxidative cleavage of crotofolin C via a putative homo-Baeyer–Villiger rearrangement. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 14226–14230.

- Loyola, L.A.; Morales, C.; Rodríguez, B.; et al. Mulinic and isomulinic acids: Rearranged diterpenes with a new carbon skeleton from Mulinum crassifolium. Tetrahedron 1990, 46, 5413–5420. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Gao, J.J.; Qin, X.J.; et al. Hedychins A and B, 6,7-dinorlabdane diterpenoids with a peroxide bridge from Hedychium forrestii. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 704–707. [CrossRef]

- Liao, F. Discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu). Molecules 2009, 14, 5362–5366. [CrossRef]

- Dahnum, D.; Abimanyu, H.; Senjaya, A. Isolation of artemisinin as an antimalarial drug from Artemisia annua L. cultivated in Indonesia. Int. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2012, 12, 90–95.

- Firestone, G.L.; Sundar, S.N. Anticancer activities of artemisinin and its bioactive derivatives. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2009, 11, e32. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Sun, Z.; Kong, F.; et al. Artemisinin-derived hybrids and their anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 188, 112044. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yi, C.; Li, W.W.; et al. Current advances in the anticancer activity of artemisinin metal complexes, hybrids, and dimers. Arch. Pharm. 2022, 355, 2200086.

- Mahmoud, A.A. Xanthanolides and xanthane epoxide derivatives from Xanthium strumarium. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 724–727. [CrossRef]

- Rustaiyan, A.; Nahrevanian, H.; Kazemi, M.; Larijani, K. Antimalarial effects of extracts of Artemisia diffusa against Plasmodium berghei. Planta Med. 2007, 73, 892–902. [CrossRef]

- Takaya, Y.; Kurumada, K.; Takeuji, Y.; et al. Nardoperoxide and related guaiane-type sesquiterpenoids from Nardostachys chinensis roots. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 1361–1364.

- Takaya, Y.; Takeuji, Y.; Akasaka, M.; et al. Nardoguaianones A–D, novel guaiane endoperoxides from Nardostachys chinensis and their biological activities. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 7673–7681.

- Aguilar-Guadarrama, A.B.; Ríos, M.Y. Three new sesquiterpenes from Croton arboreus. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 914–917.

- Dong, J.Y.; Ma, X.Y.; Cai, X.Q.; et al. Sesquiterpenoids from Curcuma wenyujin with anti-influenza viral activity. Phytochemistry 2013, 85, 122–128. [CrossRef]

- Todorova, M.; Vogler, B.; Tsankova, E. Terpenoids from Achillea setacea. Z. Naturforsch. C 2000, 55, 840–842. [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, M.E.F.; Nakamura, S.; Tawfik, W.A.; et al. Rare hydroperoxyl guaianolide sesquiterpenes from Pulicaria undulata. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 12, 177–181. [CrossRef]

- Sy, L.K.; Brown, G.D. Abietane diterpenes from Illicium angustisepalum. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 907–912. [CrossRef]

- Sy, L.K.; Brown, G.D.; Haynes, R. A novel endoperoxide and related sesquiterpenes from Artemisia annua possibly derived from allylic hydroperoxides. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 4345–4356. [CrossRef]

- Sy, L.K.; Ngo, K.S.; Brown, G.D. Biomimetic synthesis of arteannuin H and the 3,2-rearrangement of allylic hydroperoxides. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 15127–15140. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, K.S.; Brown, G.D. Allohimachalane, seco-allohimachalane, and himachalane sesquiterpenes from Illicium tsangii. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 759–766. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, K.S.; Brown, G.D. Santalane and isocampherenane sesquiterpenoids from Illicium tsangii. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 1213–1219. [CrossRef]

- Alza, N.P.; Murray, A.P. Chemical constituents and acetylcholinesterase inhibition of Senecio ventanensis Cabrera (Asteraceae). Rec. Nat. Prod. 2016, 10, 513–518.

- Rustaiyan, A.; Faridchehr, A.; Bakhtiyar, M. Sesquiterpene lactones of the Iranian Asteraceae family: Chemical constituents and antiplasmodial properties of tehranolide (Review). Orient. J. Chem. 2017, 33, 2506–2521. [CrossRef]

- Amen, Y.; Abdelwahab, G.; Heraiz, A.A.; et al. Exploring sesquiterpene lactones: Structural diversity and antiviral therapeutic insights. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 1970–1988. [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, F.; Suzuki, M.; Takaoka, S.; Asakawa, Y. New sesqui- and diterpenoids from the Japanese liverwort Jungermannia infusca (Mitt.) Steph. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1998, 46, 1184–1187. [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, F.; Suzuki, M.; Takaoka, S.; Asakawa, Y. New acorane- and cuparane-type sesquiterpenoids and labdane- and seco-labdane-type diterpenoids from Jungermannia infusca. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 9117–9128.

- Chokpaiboon, S.; Sommit, D.; Bunyapaiboonsri, T.; et al. Antiangiogenic effects of chamigrane endoperoxides from a Thai mangrove-derived fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 2290–2299. [CrossRef]

- Chokpaiboon, S.; Sommit, D.; Teerawatananond, T.; et al. Cytotoxic nor-chamigrane and chamigrane endoperoxides from a basidiomycetous fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1005–1012. [CrossRef]

- Efange, S.M.N.; Brun, R.; Wittlin, S.; et al. Okundoperoxide, a bicyclic cyclofarnesyl sesquiterpene endoperoxide from Scleria striatinux with antiplasmodial activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 280–283.

- Ma, W.H.; Tan, C.M.; He, J.C.; et al. A novel eudesmene sesquiterpenoid from the stems of Schisandra sphenanthera. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2011, 47, 713–717.

- Adio, A.M.; König, W.A. Sesquiterpene constituents from the essential oil of the liverwort Plagiochila asplenioides. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 599–609. [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, F.; Matsumura, N.; Ashigaki, Y.; Asakawa, Y. Biologically active compounds from bryophytes. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 2003, 94, 197–205.

- He, L.; Hou, J.; Gan, M.; et al. Cadinane sesquiterpenes from the leaves of Eupatorium adenophorum. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1485–1488. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zheng, G.W.; Niu, X.M.; et al. Terpenes from Eupatorium adenophorum and their allelopathic effects on Arabidopsis seed germination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 478–482. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.F.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.Z. Two eremophilane-type sesquiterpenoids from the rhizomes of Ligularia veitchiana. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2009, 25, 480–483.

- Moreira, I.C.; Roque, N.F.; Contini, K.; Lago, J.H.G. Sesquiterpenes and hydrocarbons from the fruits of Xylopia emarginata (Annonaceae). Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2007, 17, 55–62.

- Müller, S.; Murillo, R.; Castro, V.; et al. Sesquiterpene lactones from Montanoa hibiscifolia that inhibit the transcription factor NF-κB. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 622–630. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.C.; Fraser, T.R. The connection of chemical constitution and physiological action. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1868, 25, 224–242.

- Hansch, C.; Fujita, T. p-σ-π analysis: A method for the correlation of biological activity and chemical structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 1616–1626.

- Hansch, C.; Leo, A. Exploring QSAR: Fundamentals and Applications in Chemistry and Biology; ACS: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Vols. 1–2.

- Dembitsky, V.M. Microbiological aspects of unique, rare, and unusual fatty acids derived from natural amides and their pharmacological profiles. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 13, 377–417. [CrossRef]

- Muratov, E.N.; Bajorath, J.; Sheridan, R.P.; et al. QSAR without borders. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3525–3564. [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Bioactive steroids bearing an oxirane ring. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2237. [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Highly oxygenated cyclobutane rings in biomolecules: Insights into structure and activity. Oxygen 2024, 4, 181–235. [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Naturally occurring norsteroids: Design and pharmaceutical applications. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1021. [CrossRef]

| No | Discovered Activity, Pa* | Rank | Additional Activity, Pa* | Rank |

| 1 | Antineoplastic (0,692) | Weak |

Antiprotozoal (0,677) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,655) |

Weak Weak |

| 2 | Antineoplastic (0,766) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,702) | Weak |

| 3 | Antineoplastic (0,782) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,698) | Weak |

| 4 | Antineoplastic (0,791) Lymphocytic leukemia (0,756) | Weak Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,724) | Weak |

| 5 | Antineoplastic (0,621) Antimetastatic (0,575) | Weak Weak |

Antihelmintic (0,755) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,735) |

Weak Weak |

| 6 | Antineoplastic (0,859) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,583) | Weak |

| 7 | Antineoplastic (0,647) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,861) | Moderate |

| 8 | Antineoplastic (0,876) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,779) | Weak |

| 9 | Antineoplastic (0,728) Antimetastatic (0,528) | Weak Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,770) Antiparasitic (0,711) | Weak Weak |

| 10 | Antineoplastic (0,832) Antimetastatic (0,631) | Moderate Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,762) Antifungal (0,693) | Weak Weak |

| 11 | Antineoplastic (0,873) Apoptosis agonist (0,850) |

Moderate Moderate |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,900) | Strong |

| 12 | Antineoplastic (0,876) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,752) | Weak |

| 13 | Antineoplastic (0,857) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,846) | Moderate |

| 14 | Antineoplastic (0,939) | Strong | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,871) | Moderate |

| 15 | Antineoplastic (0,774) Antimetastatic (0,512) |

Weak Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,926) Antiparasitic (0,786) | Strong Weak |

| 16 | Antineoplastic (0,805) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,905) | Strong |

| 17 | Antineoplastic (0,804) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,854) | Moderate |

| 18 | Antineoplastic (0,599) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,908) | Strong |

| 19 | Antineoplastic (0,848) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,915) | Strong |

| 20 | Antineoplastic (0,685) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,829) | Moderate |

| 21 | Antineoplastic (0,726) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,772) | Weak |

| 22 | Anti-renal cancer (0,824) Antineoplastic (0,799) |

Moderate Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,917) Antifungal (0,656) | Strong Weak |

| 23 | Antineoplastic (0,804) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,731) | Weak |

| 24 | Antineoplastic (0,796) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,731) | Weak |

| 25 | Antineoplastic (0,756) Anti-renal cancer (0,592) |

Weak Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,835) Antiparasitic (0,783) | Moderate Weak |

| No | Discovered Activity, Pa* | Rank | Additional Activity, Pa* | Rank |

| 26 | Antineoplastic (0,798) Antimetastatic (0,567) |

Weak Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,851) Antifungal (0,620) | Moderate Weak |

| 27 | Antineoplastic (0,917) Antimetastatic (0,625) | Strong Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,944) Antiparasitic (0,756) | Strong Weak |

| 28 | Antineoplastic (0,980) | Strong | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,798) | Weak |

| 29 | Antineoplastic (0,824) Chemopreventive (0,675) | Moderate Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,888) | Moderate |

| 30 | Antineoplastic (0,798) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,734) | Weak |

| 31 | Antineoplastic (0,882) Antimetastatic (0,550) | Moderate Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,769) | Weak |

| 32 | Antineoplastic (0,736) Chemopreventive (0,550) | Weak Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,788) | Weak |

| 33 | Antineoplastic (0,818) Chemopreventive (0,687) |

Moderate Weak |

Antiinflammatory (0,924) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,894) | Strong Moderate |

| 34 | Antineoplastic (0,800) Chemopreventive (0,549) |

Weak Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,851) Antiinflammatory (0,661) | Moderate Weak |

| 35 | Antineoplastic (0,911) | Strong | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,744) | Weak |

| 36 | Antineoplastic (0,890) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,746) | Weak |

| 37 | Antineoplastic (0,904) Chemopreventive (0,653) | Strong Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,832) | Moderate |

| 38 | Antineoplastic (0,871) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,801) | Weak |

| 39 | Antineoplastic (0,887) | Moderate | Antiinflammatory (0,946) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,868) | Strong Moderate |

| 40 | Antineoplastic (0,856) Antimetastatic (0,567) |

Weak Weak |

Antiinflammatory (0,934) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,834) | Strong Moderate |

| 41 | Antineoplastic (0,681) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,908) | Strong |

| 42 | Antineoplastic (0,809) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,918) | Strong |

| No | Discovered Activity, Pa* | Rank | Additional Activity, Pa* | Rank |

| 43 | Antineoplastic (0,928) Antimetastatic (0,892) Antimelanoma (0,901) Apoptosis agonist (0,896) |

Strong Moderate Strong Moderate |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,998) Antibacterial (0,910) Antiprotozoal (Trypanosoma) (0,914) Antiprotozoal (Leishmania) (0.954) |

Strong Strong Strong Strong |

| 44 | Antineoplastic (0,911) Apoptosis agonist (0,883) |

Strong Moderate |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,967) Antiprotozoal (Leishmania) (0,731) |

Strong Weak |

| 45 | Antineoplastic (0,914) | Strong | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,925) | Strong |

| 46 | Antineoplastic (0,787) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,739) | Weak |

| 47 | Antineoplastic (0,855) Prostate cancer treatment (0,641) |

Moderate Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,745) |

Weak |

| 48 | Antineoplastic (0,797) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,917) | Strong |

| 49 | Antineoplastic (0,769) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,889) | Moderate |

| 50 | Antineoplastic (0,912) Apoptosis agonist (0,890) Cytostatic (0,870) |

Strong Moderate Moderate |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,936) Antiparasitic (0,774) Antifungal (0,687) |

Strong Weak Weak |

| 51 | Antineoplastic (0,898) Apoptosis agonist (0,741) |

Moderate Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,939) Antiparasitic (0,716) |

Strong Weak |

| 52 | Antineoplastic (0,885) Prostate disorders treatment (0,588) |

Moderate Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,933) Antiinflammatory (0,713) |

Strong Weak |

| 53 | Antineoplastic (0,946) Apoptosis agonist (0,782) |

Strong Weak |

Antiinflammatory (0,949) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,752) |

Strong Weak |

| 54 | Antineoplastic (0,917) | Strong | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,922) | Strong |

| 55 | Antimetastatic (0,628) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,842) | Moderate |

| 56 | Antimetastatic (0,628) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,842) | Moderate |

| 57 | Antineoplastic (0,932) Apoptosis agonist (0,617) |

Strong Weak |

Antiinflammatory (0,958) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,936) |

Strong Strong |

| 58 | Antineoplastic (0,932) Apoptosis agonist (0,617) |

Strong Weak |

Antiinflammatory (0,958) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,936) |

Strong Strong |

| 59 | Apoptosis agonist (0,910) Antineoplastic (0,768) | Strong Weak |

Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,954) | Strong |

| 60 | Antineoplastic (0,681) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,928) | Strong |

| 61 | Antineoplastic (0,681) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,928) | Strong |

| 62 | Antineoplastic (0,730) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,951) | Strong |

| 63 | Antineoplastic (0,714) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,908) | Strong |

| 64 | Antineoplastic (0,866) |

Moderate | Antiinflammatory (0,934) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,879) |

Strong Moderate |

| 65 | Antineoplastic (0,854) | Moderate | Antiinflammatory (0,945) Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,916) |

Strong Strong |

| 66 | Antineoplastic (0,792) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,965) | Strong |

| 67 | Apoptosis agonist (0,565) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,954) | Strong |

| 68 | Antineoplastic (0,670) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,956) | Strong |

| 69 | Apoptosis agonist (0,862) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,964) | Strong |

| 70 | Antineoplastic (sarcoma) (0,529) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,945) | Strong |

| 71 | Antineoplastic (0,599) | Weak | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,881) | Moderate |

| 72 | Antineoplastic (0,862) | Moderate | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium) (0,884) | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).