1. Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), a member of the Coronaviridae family, is a highly pathogenic enteric coronavirus that causes severe watery diarrhea, vomiting, and high mortality in neonatal piglets, leading to substantial economic losses in the global swine industry [

1]. Since its initial identification in the 1970s, PEDV has evolved into multiple genotypes, with the emerging GI (classical) and GII (variant) strains becoming dominant in recent outbreaks [

2]. Among these, the GII genotype-particularly the GIIa, GIIb, and GIIc subgroups-has shown increased virulence and antigenic variability, posing significant challenges to existing vaccine strategies [

3,

4]. Current commercial vaccines, primarily based on classical GI strains (such as CV777), have demonstrated limited efficacy against emerging GII variants due to antigenic drift and poor cross-neutralization [

5,

6]. Although several inactivated and attenuated vaccines derived from GIIa strains have been developed, their protective scope remains narrow, often failing to elicit broad immune responses against heterologous GIIb and GIIc variants [

7]. This immunological gap underscores the urgent need for novel vaccine candidates that can address the ongoing genetic divergence of PEDV.

The PEDV genome is approximately 28 kb in length and consists of a 5’ cap structure, a 3’ poly(A) tail, and at least seven open reading frames (ORFs), including ORF1a, ORF1b, S, ORF3, E, M, and N genes [

8]. These ORFs encode four structural proteins (spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins), 16 nonstructural proteins (NSPs), and one accessory protein, ORF3 [

9]. The S protein, located on the surface of the virion, is the largest structural protein and can induce the production of neutralizing antibodies [

10]. The PEDV S gene can be classified into three genotypes: GI, GII, and S-Indel. Variations such as nucleotide substitutions, deletions, or insertions in the S gene exist among different PEDV strains [

11]. Consequently, the S gene is frequently used as a target for molecular epidemiological and phylogenetic analyses of PEDV. Recent studies have highlighted the critical role of the spike (S) protein in mediating viral entry and neutralizing antibody responses [

12,

13]. Phylogenetic analyses of circulating strains in China (2020–2022) indicate that GIIc variants have become increasingly prevalent, with distinct mutations in the S gene receptor-binding domain potentially contributing to immune evasion [

14]. However, few studies have focused on the development of GIIc-based vaccines, and their cross-protective potential against other prevalent genotypes remains unexplored.

In this study, we isolated and characterized a novel PEDV strain, designated PEDV-HeN2024, belonging to the GIIc subgroup. This strain demonstrated high pathogenicity in both neonatal (3–5 days) piglets, causing severe enteric pathology and high viral shedding. We further developed an inactivated vaccine using this strain adjuvanted with ISA 201 VG and evaluated its immunogenicity and cross-protective efficacy. Our results demonstrate that the vaccine induces high titers of neutralizing antibodies and total immunoglobulins, providing robust cross-protection against homologous GIIc and heterologous GIIa/GIIb challenges. These findings highlight the potential of GIIc-based vaccines as broad-spectrum candidates for controlling PED outbreaks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Viruses

Vero cells were purchased from BeNa Culture Collection (Xinyang, China). The cells were cultured in Gibco™ DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% Gibco™ fetal calf serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and Gibco™ penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The cells were maintained at 37℃, 5% CO2, and 90% relative humidity. The PEDV-GIIa and PEDV-GIIb strains were isolated and preserved by our laboratory.

2.2. Virus Isolation and Propagation

The intestinal contents or fecal samples from piglets with severe watery diarrhea were collected from a swine farm in China. The samples were homogenized, centrifuged, and filtered through a 0.22-μm filter. The filtrate was inoculated onto confluent monolayers of Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 μg/mL trypsin (TPCK-treated) and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ incubator. After 1 hour of adsorption, the inoculum was removed, and fresh maintenance medium was added. The cells were monitored daily for cytopathic effects (CPE). Blind passages were performed until stable CPE (syncytium formation and cell detachment) was observed [

2,

7].

Plaque Purification:When the cell density in the 6-well plate reached approximately 90%, a plaque assay was performed. The virus was diluted in DMEM, inverted, and vortexed twice. The pipette tip was changed, and the nutrient solution in the 6-well plate was aspirated and discarded in two steps. Subsequently, 1 mL of virus-containing DMEM was added to the wells from 10-7 to 10-2 dilutions. The plate was incubated for 2 hours and gently shaken every 20 minutes. Agar was melted in a water bath 1 hour in advance, and both the melted agar and 2× DMEM (supplemented with 2% serum, pH=7.6) were placed in a 37°C water bath 0.5 hour prior to use. A mixture of 2% low-melting-point agarose and 2× DMEM was prepared at a 1:1 ratio, with 14 mL of each combined in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. After aspirating the virus-containing DMEM from the wells (10-7 to 10-2), 2 mL of the mixed agarose was added to each well and allowed to solidify at room temperature for 0.5 hour. Once solidified, the plate was transferred to a 5% CO₂ incubator at 37°C for 72–96 hours. When distinct plaques became visible, the plate was removed, stained with crystal violet solution for 12 hours at room temperature, rinsed under running water to remove the agarose, and plaque morphology was observed.

50% Tissue Culture Infective Dose (TCID₅₀) Assay: pon the appearance of significant cytopathic effects (CPE), the collected viral supernatant was titrated. Vero cells were passaged into a 96-well cell culture plate one day prior to the assay. On the day of the assay, the viral solution was serially diluted twofold in DMEM containing 10 μg/mL trypsin, ranging from 10-1 to 10-8. The supernatant of confluent Vero cell monolayers in the 96-well plate was discarded, and the cells were washed twice with PBS. The diluted viral solution was then inoculated into the cell culture plate, with eight parallel replicates per dilution, and 100 μL of viral solution was added per well. Normal cells were used as a blank control, with 100 μL of DMEM containing 10 μg/mL trypsin added per well. After 5–7 days of incubation, CPE was observed, and the data were analyzed using the Reed–Muench method [

15].

2.3. Virus Identification and Characterization

Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA): Vero cells infected with the isolated virus were fixed with 80% acetone. The cells were then incubated with a porcine anti-PEDV specific antibody (MEDIAN Diagnostics, Korea) for 1 h at 37°C, followed by incubation with a FITC-conjugated goat anti-pig IgG antibody (1:200 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich). The nuclei were stained with DAPI. The cells were visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti2).

Genetic Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis: Viral RNA was extracted from the cell culture supernatant using TRIzol LS Reagent (Invitrogen). The full-length spike (S) gene was amplified by RT-PCR using specific primers (S1-Forward: 5’- AGATTGCTCTACCTTATACCTG-3’, S1-Reverse: 5’- GAAAGAACTAAACCCATTGATA-3’; S2-Forward: 5’- AGCCAACTCAAGTGTTCTCAGG-3’, S2-Reverse: 5’- AGCCACAGTGTTCAAACCCTT-3’; S3-Forward: 5’- TTAATAAAGTGGTTACTAATGGC-3’, S3-Reverse: 5’- ATAATAAAGAGCGCATTTTTATA-3’;). The amplified products were purified and sequenced (Sangon Biotech). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the complete nucleotide sequence of the spike (S) gene. Reference sequences of different genotypes (GI, S-Indel, GII) were downloaded from GenBank.

2.4. Animal Challenge Studies

All animal experiments were approved by Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee (AWEC) of ShenLian Bio-medicine (Shanghai) Co.,Ltd (Approval No: 2025003-1 and 2025009-1) and were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) piglets from two age groups (3-5 days old, n=3; 28-30 days old, n=3) were orally inoculated with 10 mL of the fifth-passage virus stock. A control group (n=3 for each age group) was inoculated with an equal volume of sterile PBS. Clinical signs (diarrhea, vomiting, lethargy) were recorded daily. Fecal swabs were collected daily for viral RNA detection by RT-PCR targeting the PEDV N gene. At 5 days post-inoculation (dpi), all piglets were euthanized for necropsy. Intestinal tissues were collected for histopathological examination and viral load quantification.

2.5. Vaccine Preparation and Immunization

The isolated PEDV-GIIc virus was propagated, inactivated with 0.1% binary ethylenimine (BEI) at 37°C for 24 h, and confirmed for complete inactivation by three blind passages in Vero cells. The inactivated antigen was emulsified with ISA 201 VG adjuvant (Seppic) at a ratio of 1:1 (v/v) to form a Water-in-Oil-in-Water (W/O/W) emulsion.

Twenty-one 3-5 days old SPF piglets were randomly divided into three groups (n=3 per group): Group 1 (Vaccinated): Immunized intramuscularly with 2 mL of the inactivated vaccine. Group 2 (Placebo control): Inoculated with 2 mL of PBS emulsified with ISA 201 VG adjuvant (1:1). Group 3 (Blank control): Inoculated with 2 mL of PBS. A booster immunization was administered with the same formulation 14 days later.

2.6. Serological Assay

Sera were collected at 0, 14, 21, 28 and 35 days post-immunization (dpi). Virus Neutralization (VN) assay: Serum samples were serially diluted two-fold and mixed with an equal volume of 200 TCID₅₀ of PEDV strains (GIIa, GIIb, and GIIc). The mixture was incubated and then added to Vero cell monolayers. The neutralizing antibody titer was calculated as the highest serum dilution that completely inhibited CPE [

16].

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): PEDV-specific total antibodies (IgG) in serum were detected using a commercial PEDV Antibody Test Kit (Lanzhou Shou yan Biotechnology Co., Ltd) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Virus Isolation and Genetic Characterization

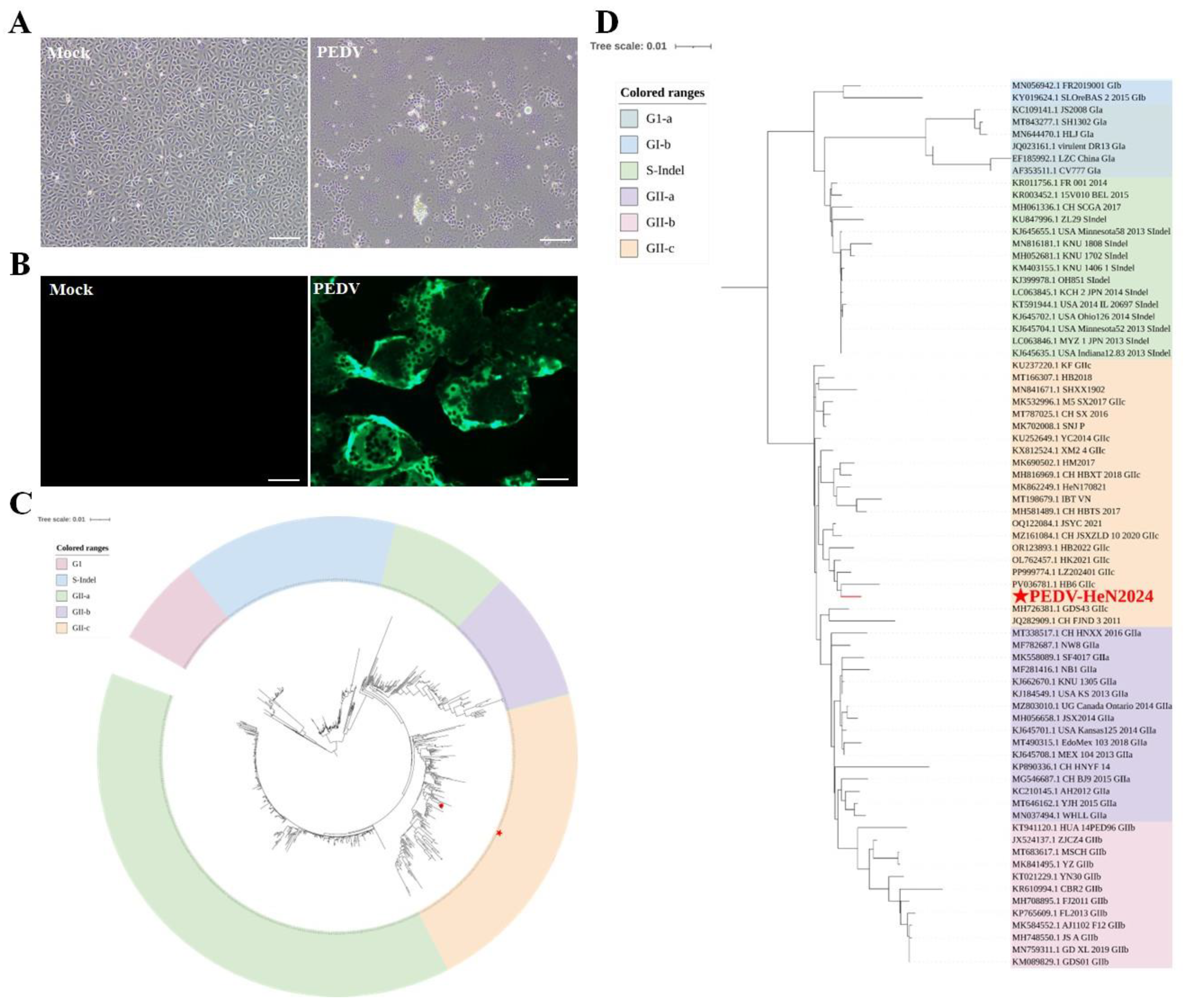

A novel PEDV strain was successfully isolated from the clinical samples using Vero cells. The two processed intestinal homogenates (Intestine-1 and Intestine-2) were identified by RT-PCR (Figure S1A). The results showed that, compared with the positive control, both samples produced a specific band of approximately 830 bp. The culture supernatant harvested after five serial blind passages in Vero cells was also analyzed by RT-PCR. As shown in Figure S1B, with properly functioning negative and positive controls, the amplified products exhibited bands of the expected size. This indicates that the PEDV isolate obtained from the processed intestinal homogenate was stably passaged from passages 1 to 5 (P1-P5). After four blind passages, typical cytopathic effects (CPE), characterized by syncytium formation and cell detachment, were consistently observed (

Figure 1A). Subsequent plaque purification was performed on the F5 viral harvest originating from intestinal sample 2. After three rounds of purification, a single clone exhibiting the most rapid growth was selected for use as the seed virus (Figure S1C). To further verify the viral identity, an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) was performed. The assay utilized a monoclonal antibody that specifically targets the spike (S) protein of PEDV, which yielded positive results, thereby confirming the virus’s identity. Robust fluorescence signals were observed in the cytoplasm of virus-infected Vero cells, whereas no signal was detected in mock-infected cells (

Figure 1B). The isolated virus was designated as PEDV-HeN2024.

Genetic characterization based on the complete spike (S) gene sequence (GenBank accession no. PX470115) was performed. Sequence alignment revealed that our isolate possessed the signature insertions and deletions in the S gene that are characteristic of variant strains, distinguishing it from classical CV777-like strains. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that PEDV/HeN2024 clustered within the GIIc genogroup, which has been increasingly reported in China since 2020. Notably, it formed a distinct branch with other recently emerged GIIc strains, indicating its status as a new and evolving variant within this genogroup (

Figure 1C,D).

Table 1.

Clinical symptoms among piglet pathogenesis experiments of PEDV-HeN2024.

Table 1.

Clinical symptoms among piglet pathogenesis experiments of PEDV-HeN2024.

| Groups |

Neonatal piglets |

Weaned piglets |

| No. |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| ID |

104.0

|

C |

106.0

|

C |

| MTA |

18 ± 3 |

/ |

25 ± 4 |

/ |

| MTD |

1.0 ± 0.3 |

/ |

1.5 ± 0.4 |

/ |

| MTH |

36 ± 24 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| M/M |

100/100 |

/ |

100/0 |

/ |

| RI |

0 |

/ |

100 |

/ |

No., the number of animals. C, Control. ID, Inoculated doses (TCID50). MTA, Mean time loss of appetite (hours). MTD, Mean time to show watery diarrhea (days). MTH, Mean time to death after showing clinical signs (hours). M/M, Morbidity/mortality (%). RI, Recovery rate after MEV-SD1 infection (%). /, no found.

3.2. Pathogenicity of PEDV/HeN2024/GIIc in Piglets

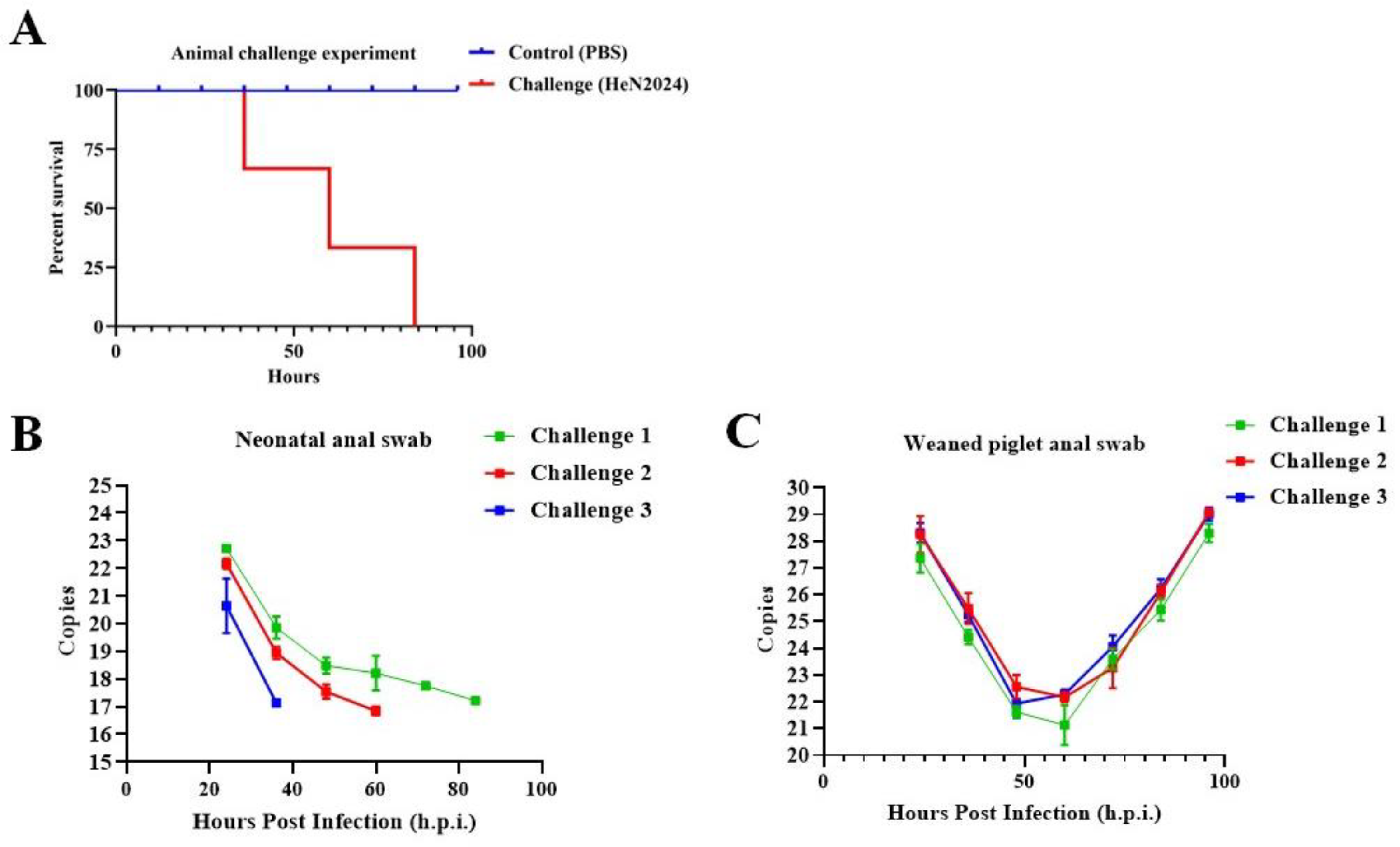

The pathogenicity of the PEDV/HeN2024/GIIc isolate was evaluated in both neonatal (3-5 days old) and weaned (28-30 days old) specific-pathogen-free (SPF) piglets. All inoculated piglets in both age groups developed severe clinical signs, including watery diarrhea and vomiting, within 24-48 hours post-inoculation (hpi) (

Table 1). The clinical disease was notably more acute in neonatal piglets. Consistent with field observations of variant PEDV strains, 100% mortality (n=3/3) was observed in the neonatal group by 96 hpi (

Figure 2A). In contrast, weaned piglets showed significant morbidity (e.g., severe diarrhea, lethargy, anorexia) but no mortality, highlighting the age-dependent susceptibility to PEDV (

Table 1). No clinical signs were observed in the PBS-inoculated control groups throughout the study. High levels of viral shedding were detected via RT-qPCR in fecal swabs collected from all challenged piglets, starting from 1 day post-inoculation (dpi) and persisting until the endpoint of the experiment (for weaned piglets) or death (for neonates) (

Figure 2B,C). Viral RNA copies in feces peaked at around 2-4 dpi.

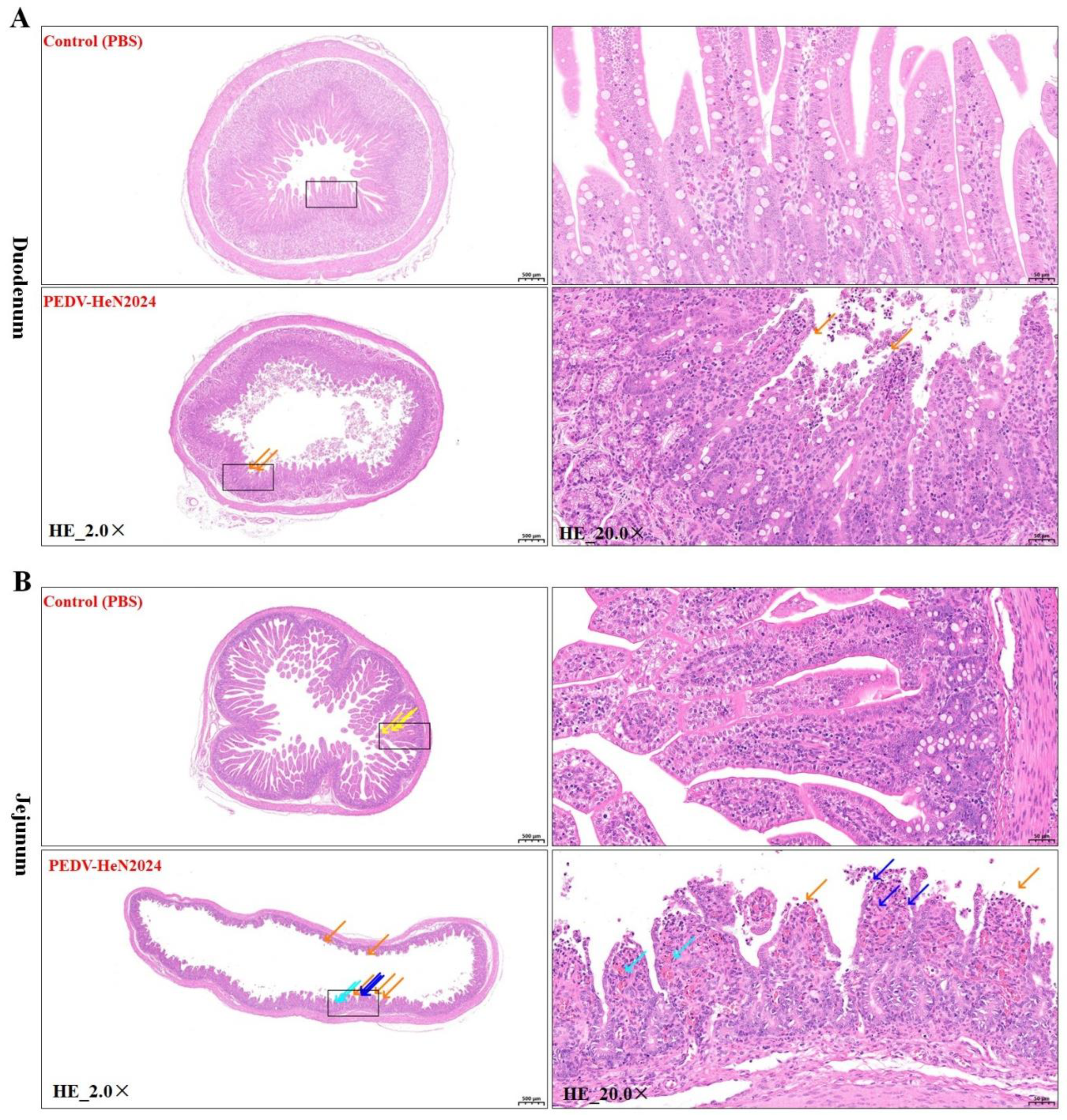

Postmortem examination of dead piglets revealed characteristic lesions of severe PEDV infection. The small intestines, particularly the duodenum and jejunum, were thin-walled, transparent, and distended with yellow, watery fluid (Figure S2). Histopathological analysis (H&E staining) of the duodenum and jejunum from infected piglets revealed villus atrophy and degeneration of intestinal epithelial cells compared to the control groups (

Figure 3). These findings confirm the high enteropathogenicity of the PEDV/HeN2024/GIIc isolate.

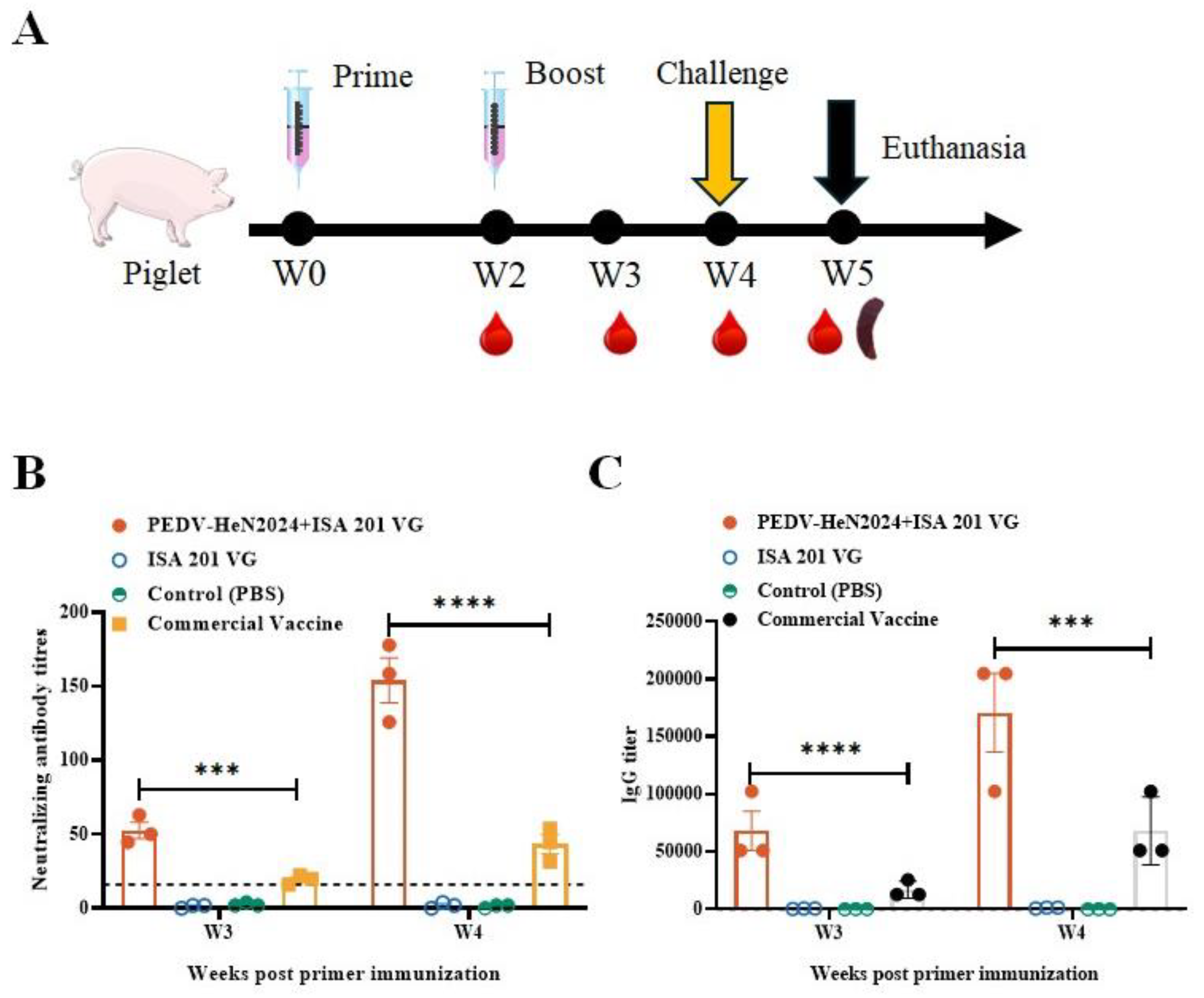

3.3. Immunogenicity of the Inactivated Vaccine

The inactivated vaccine formulated with ISA 201 VG adjuvant (1:1 ratio) induced robust humoral immune responses in immunized piglets. Virus-neutralizing (VN) antibody titers and PEDV-specific IgG antibody levels were measured weekly (

Figure 4A). From 21 days post-immunization (dpi) onwards, the geometric mean titers (GMT) of virus-neutralizing (VN) antibodies and the concentrations of IgG antibodies in the vaccinated group were significantly higher than those in the placebo (adjuvant-only) group, the blank control group (p<0.01), and the commercial vaccine group. The VN antibody titers in the vaccinated group continued to rise until the challenge study at 28 dpi, indicating a strong and sustained immune response elicited by the vaccine (

Figure 4B,C).

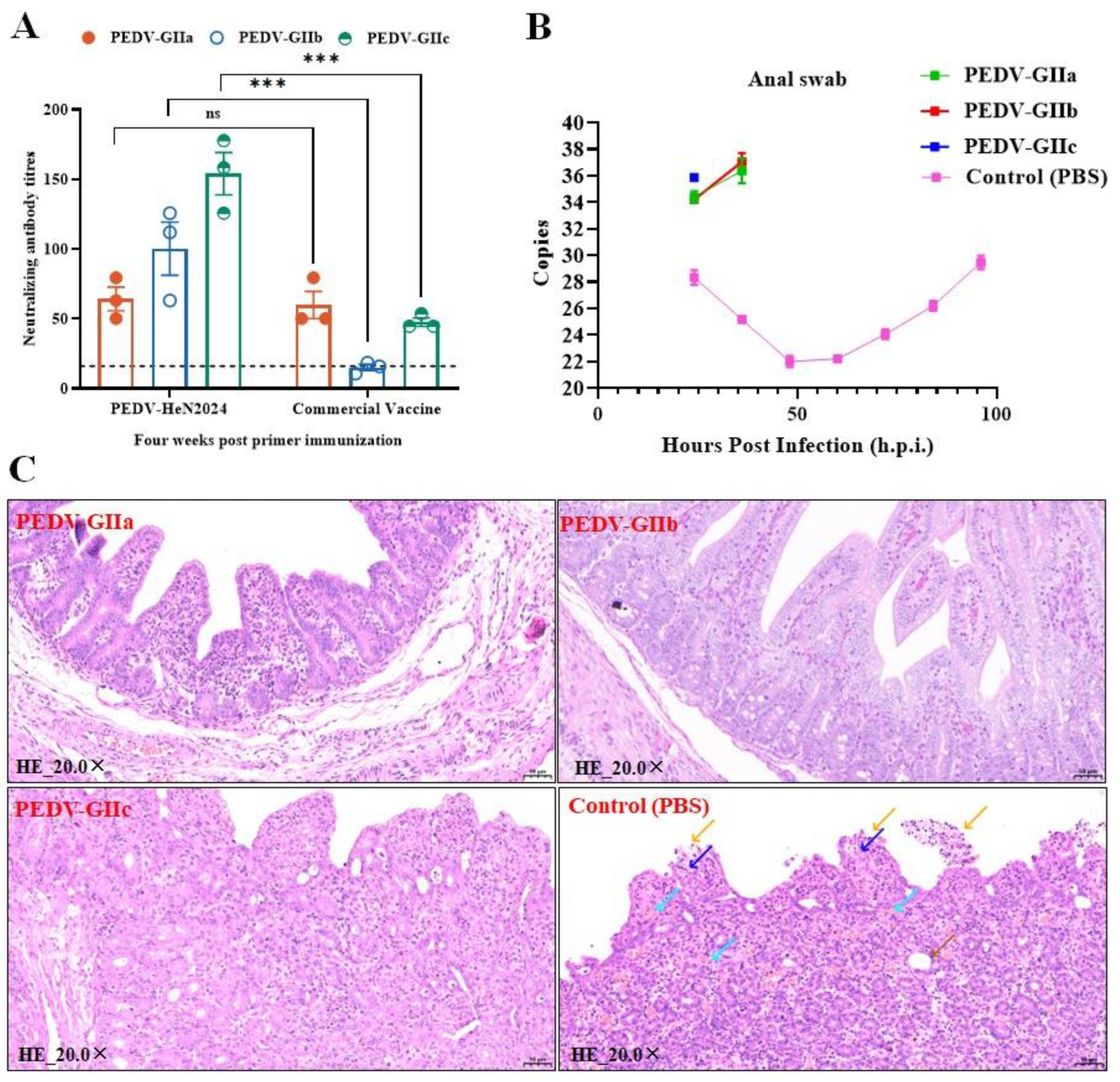

3.4. Cross-Protective Efficacy Against Heterologous Challenges

The key finding of this study was the broad cross-neutralizing activity elicited by the GIIc-based inactivated vaccine. At 28 days post-immunization, serum samples were tested for neutralization activity in vitro. The sera demonstrated potent neutralizing activity against both the homologous GIIc strain (PEDV/HeN2024/GIIc) and heterologous GIIa and GIIb strains. Notably, the neutralizing antibody titers against all tested strains were significantly higher than those elicited by the commercial vaccine.. The sera effectively neutralized all three tested strains, with the highest GMT observed against the homologous virus (

Figure 5A). This result demonstrated the induction of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies.

The PEDV-HeN2024 vaccine conferred complete protection against clinical disease upon challenge with all three genotypes (GIIa, GIIb, and GIIc), the absence of diarrhea and fecal viral shedding served as the primary endpoints for efficacy evaluation. Following heterologous viral challenges (with GIIa and GIIb strains), piglets in the vaccinated group exhibited significant protection: they showed no clinical signs, and significantly reduced viral shedding in feces was detected via RT-qPCR (

Figure 5B). Histopathological examination of the jejunum post-challenge revealed well-preserved intestinal villus structures in the vaccinated group, in stark contrast to the villus atrophy observed in the control groups (

Figure 5C).

4. Discussion

The continuous emergence of PEDV variants, particularly within the GII genogroup, poses a significant and ongoing challenge to the global swine industry [

2,

17,

18]. Vaccination remains the most effective strategy for controlling PED; however, the efficacy of existing commercial vaccines, often based on classical or earlier variant strains, is frequently compromised against these emerging variants due to antigenic differences [

19,

20]. In this study, we successfully isolated a novel PEDV strain, identified it as a GIIc variant through comprehensive genetic and phylogenetic analyses, and developed an inactivated vaccine that demonstrated exceptional immunogenicity and broad cross-protective efficacy against homologous and heterologous challenges.

Our phylogenetic analysis confirmed that the isolated strain, PEDV-HeN2024, clusters with recently emerging GIIc strains but occupies a distinct branch, suggesting ongoing viral evolution [

21]. This genetic divergence is a primary driver for the suboptimal protection offered by existing vaccines, as mutations, especially in the S protein which is the major target for neutralizing antibodies, can lead to antigenic drift and immune evasion [

22,

23]. The high pathogenicity of our isolate was unequivocally demonstrated in both neonatal and weaned piglets. The 100% mortality in neonatal piglets and significant morbidity in weaned piglets align with the severe clinical manifestations reported in outbreaks caused by contemporary variants, underscoring the urgent need for effective countermeasures [

5,

24,

25].

The cornerstone of our findings is the remarkable cross-protective ability induced by the GIIc-based inactivated vaccine. Sera from vaccinated animals potently neutralized not only the homologous GIIc virus but also heterologous GIIa and GIIb strains in vitro. This was further corroborated by in vivo challenge studies: vaccinated piglets, when challenged with all three genotypes (GIIa, GIIb, GIIc), exhibited significant protection, showing no clinical symptoms, substantially reduced viral shedding, and maintained normal intestinal architecture. This broad-spectrum protection is likely attributable to the presentation of conserved antigenic epitopes shared among the contemporary GII variants by our vaccine strain [

7]. By utilizing a recently circulating GIIc variant as the vaccine seed, we potentially elicited a broader and more relevant immune response compared to vaccines based on older strains. This finding is critically important, as it suggests that updating vaccine strains to match currently prevalent variants can overcome the limitations of cross-protection [

26,

27].

Our results are consistent with and extend the findings of other research groups focusing on PEDV variants. For instance, Li et al. highlighted the role of non-structural proteins, such as nsp1, in the immune evasion mechanisms of variant strains, which may explain the virulence of our isolate and the necessity for a well-matched vaccine to counteract such mechanisms [

20,

28,

29]. Furthermore, the approach of using a recently isolated variant for vaccine development mirrors the strategy advocated by others, emphasizing the importance of surveillance and timely updates to vaccine formulations [

18,

30,

31].

While our inactivated vaccine candidate shows great promise, several aspects warrant further investigation. First, the duration of immunity conferred by this vaccine needs to be evaluated in a long-term study, especially in sows to assess the level and persistence of maternal antibodies transferred to piglets [

6,

13]. Second, exploring the vaccine’s efficacy in a prime-boost regimen, potentially combining it with a live-attenuated vaccine, could further enhance the strength and breadth of the immune response [

32,

33,

34]. Furthermore, the challenge strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) exhibited attenuated pathogenicity in older piglets [

35]. Our results indicated that 31-day-old piglets challenged with the virus displayed only mild and transient clinical diarrhea, which somewhat complicated the assessment of protective efficacy. Finally, investigating the specific conserved epitopes responsible for the cross-neutralizing activity could guide the development of even more effective next-generation vaccines, such as subunit or epitope-based vaccines [

36].

In conclusion, we have developed a novel inactivated vaccine based on an emerging PEDV GIIc variant. This vaccine elicits robust neutralizing antibodies and provides broad cross-protection against the predominant heterologous GII strains currently in circulation. Our study underscores the importance of continuous viral surveillance and the timely development of vaccines based on prevalent strains as a viable strategy to control the devastating losses caused by PEDV variants in the swine industry.

Author Contributions

Jingjing Xu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing– original draft, Writing– review& editing. Ningning Fu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing– original draft. Zimin Liu: Formal Analysis, Software, review & editing. Mengli Chen: Investigation, review & editing. Guijun Ma: Investigation, Supervision. Hehai Li: Conceptualization, Methodology. Jianghui Wang: Investigation, Supervision. Bo Yin: Funding acquisition, Supervision. Zhen Zhang: Funding acquisition, Supervision, review & editing. Feifei Diao: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing– original draft.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanghai Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project (grant numbers K2024002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were approved by Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee (AWEC) of ShenLian Bio-medicine (Shanghai) Co.,Ltd (Approval No: 2025003-1 and 2025009-1, date 1 March 2025) and were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials supporting the findings of this study are available through the NCBI Nucleotide. The dataset has been deposited under the GenBank accession no. PX470115.

Acknowledgments

We thank Associated Professor Wentao Fan at the Institute of MOE Joint International Research Laboratory of Animal Health and Food Safety, College of Veterinary Medicine, Nanjing Agricultural University for his valuable guidance and insightful opinions throughout this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wood, E.N. An apparently new syndrome of porcine epidemic diarrhoea. Vet Rec 1977, 100, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: An emerging and re-emerging epizootic swine virus. Virol J 2015, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.Q.; et al. Outbreak of porcine epidemic diarrhea in suckling piglets, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2012, 18, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; et al. Global Dynamics of Porcine Enteric Coronavirus PEDV Epidemiology, Evolution, and Transmission. Mol Biol Evol 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; et al. New variants of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, China, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2012, 18, 1350–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; et al. Efficacy evaluation of a bivalent subunit vaccine against epidemic PEDV heterologous strains with low cross-protection. J Virol 2024, 98, e0130924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, T.; et al. Cell culture isolation and sequence analysis of genetically diverse US porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains including a novel strain with a large deletion in the spike gene. Vet Microbiol 2014, 173, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdts, V.; Zakhartchouk, A. Vaccines for porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and other swine coronaviruses. Vet Microbiol 2017, 206, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; et al. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus E protein suppresses RIG-I signaling-mediated interferon-β production. Vet Microbiol 2021, 254, 108994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Park, B. Porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus: a comprehensive review of molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, and vaccines. Virus Genes 2012, 44, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; et al. Emergence and evolution of highly pathogenic porcine epidemic diarrhea virus by natural recombination of a low pathogenic vaccine isolate and a highly pathogenic strain in the spike gene. Virus Evol 2020, 6, veaa049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A.C.; et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of a coronavirus spike glycoprotein trimer. Nature 2016, 531, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; et al. PEDV-spike-protein-expressing mRNA vaccine protects piglets against PEDV challenge. mBio 2024, 15, e0295823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, M.; et al. Genetic evolution and phylogenetic analysis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains circulating in and outside China with reference to a wild type virulent genotype CHYJ130330 reported from Guangdong Province, China. Gut Pathog 2024, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.F., VARIANCE ESTIMATION IN THE REED-MUENCH FIFTY PER CENT END-POINT DETERMINATION. Am J Hyg, 1964. 79: p. 37-46.

- Zhang, D.; et al. Development of a safe and broad-spectrum attenuated PEDV vaccine candidate by S2 subunit replacement. J Virol 2024, 98, e0042924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.H.; et al. Gut microbiota-derived LCA mediates the protective effect of PEDV infection in piglets. Microbiome 2024, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; et al. Based on the Results of PEDV Phylogenetic Analysis of the Most Recent Isolates in China, the Occurrence of Further Mutations in the Antigenic Site S1° and COE of the S Protein Which Is the Target Protein of the Vaccine. Transbound Emerg Dis 2023, 2023, 1227110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; et al. Mini-review: microbiota have potential to prevent PEDV infection by improved intestinal barrier. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1230937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; et al. Nonstructural Protein 1 of Variant PEDV Plays a Key Role in Escaping Replication Restriction by Complement C3. J Virol 2022, 96, e0102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; et al. Phylogenetic and Genetic Variation Analysis of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus in East Central China during 2020-2023. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; et al. Accurate location of two conserved linear epitopes of PEDV utilizing monoclonal antibodies induced by S1 protein nanoparticles. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 253 Pt 6, 127276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; et al. Research progress of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus S protein. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1396894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. The Emergence of Novel Variants of the Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Gene from 2011 to 2023. Transbound Emerg Dis 2024, 2024, 2876278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; et al. Investigation of Transmission and Evolution of PEDV Variants and Co-Infections in Northeast China from 2011 to 2022. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; et al. Engineering a recombination-resistant live attenuated vaccine candidate with suppressed interferon antagonists for PEDV. J Virol 2025, 99, e0045125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; et al. Neutralizing antibody levels as a key factor in determining the immunogenic efficacy of the novel PEDV alpha coronavirus vaccine. Vet Q 2025, 45, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; et al. Identification of Cell Types and Transcriptome Landscapes of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus-Infected Porcine Small Intestine Using Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. J Immunol 2023, 210, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; et al. Constructions and immunogenicity evaluations of two porcine epdemic diarrhea virus-like particle vaccines. Vet Microbiol 2025, 303, 110451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; et al. A new PEDV strain CH/HLJJS/2022 can challenge current detection methods and vaccines. Virol J 2023, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.; Saif, L.J. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection: Etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and immunoprophylaxis. Vet J 2015, 204, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; et al. Genetic signatures associated with the virulence of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus AH2012/12. J Virol 2023, 97, e0106323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; et al. Combination of S1-N-Terminal and S1-C-Terminal Domain Antigens Targeting Double Receptor-Binding Domains Bolsters Protective Immunity of a Nanoparticle Vaccine against Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 12235–12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; et al. Evaluating passive immunity in piglets from sows vaccinated with a PEDV S protein subunit vaccine. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14, 1498610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; et al. Trypsin-independent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus US strain with altered virus entry mechanism. BMC Vet Res 2017, 13, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; et al. Ferritin Complex Vaccine against Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV) Using Screened Immunogenic Sequences from Fv-Antibody Library. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2025, 11, 4492–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).