Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

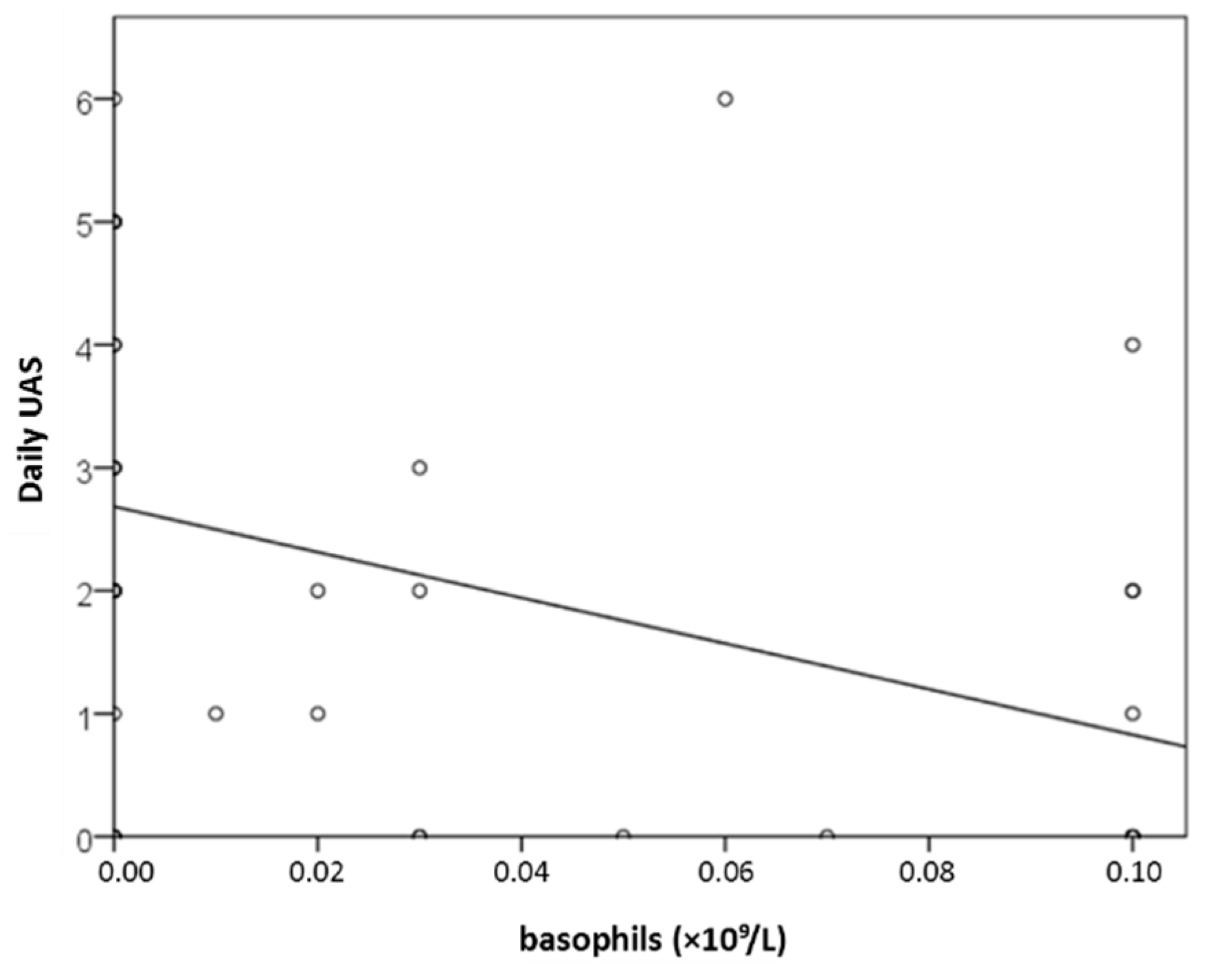

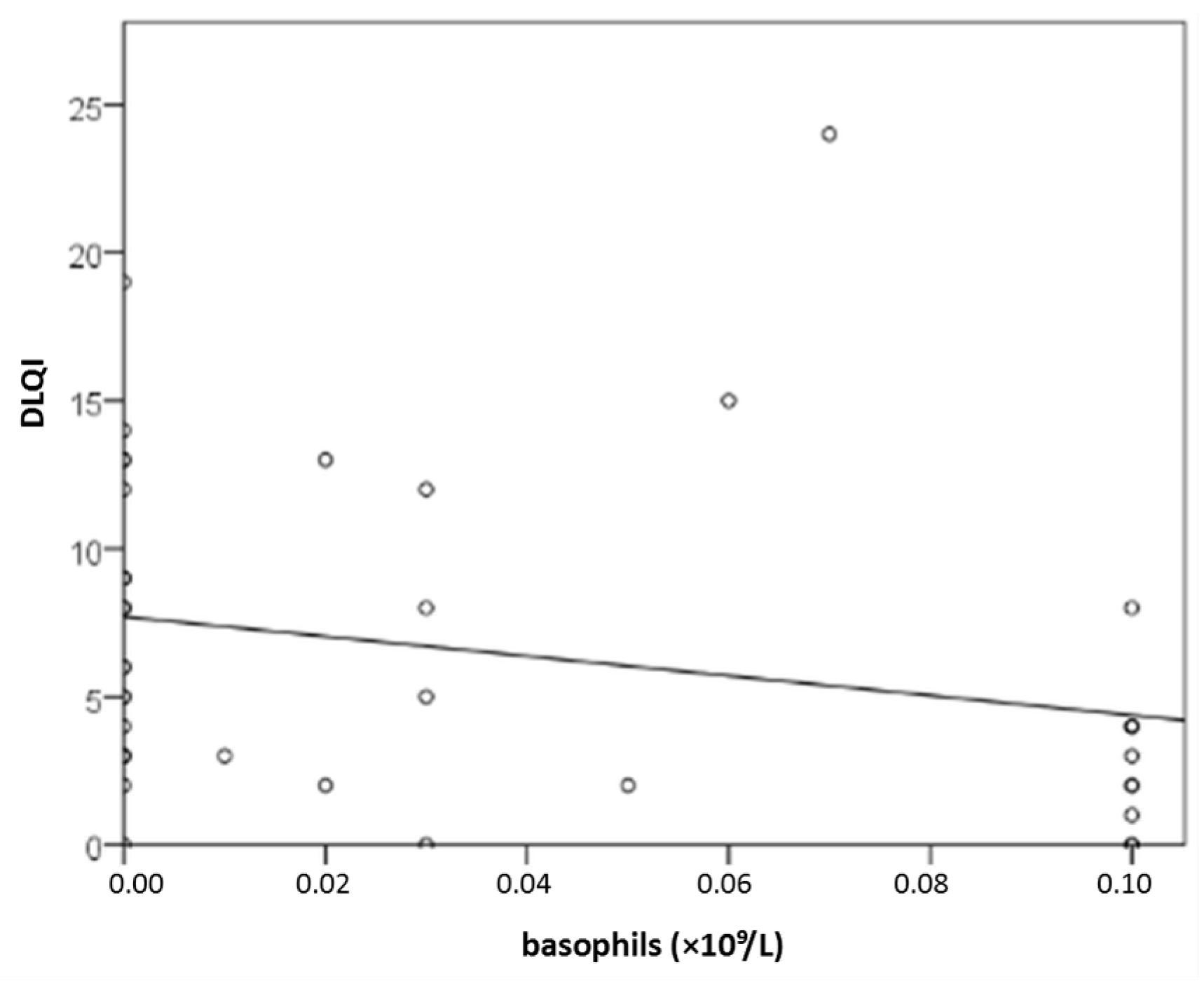

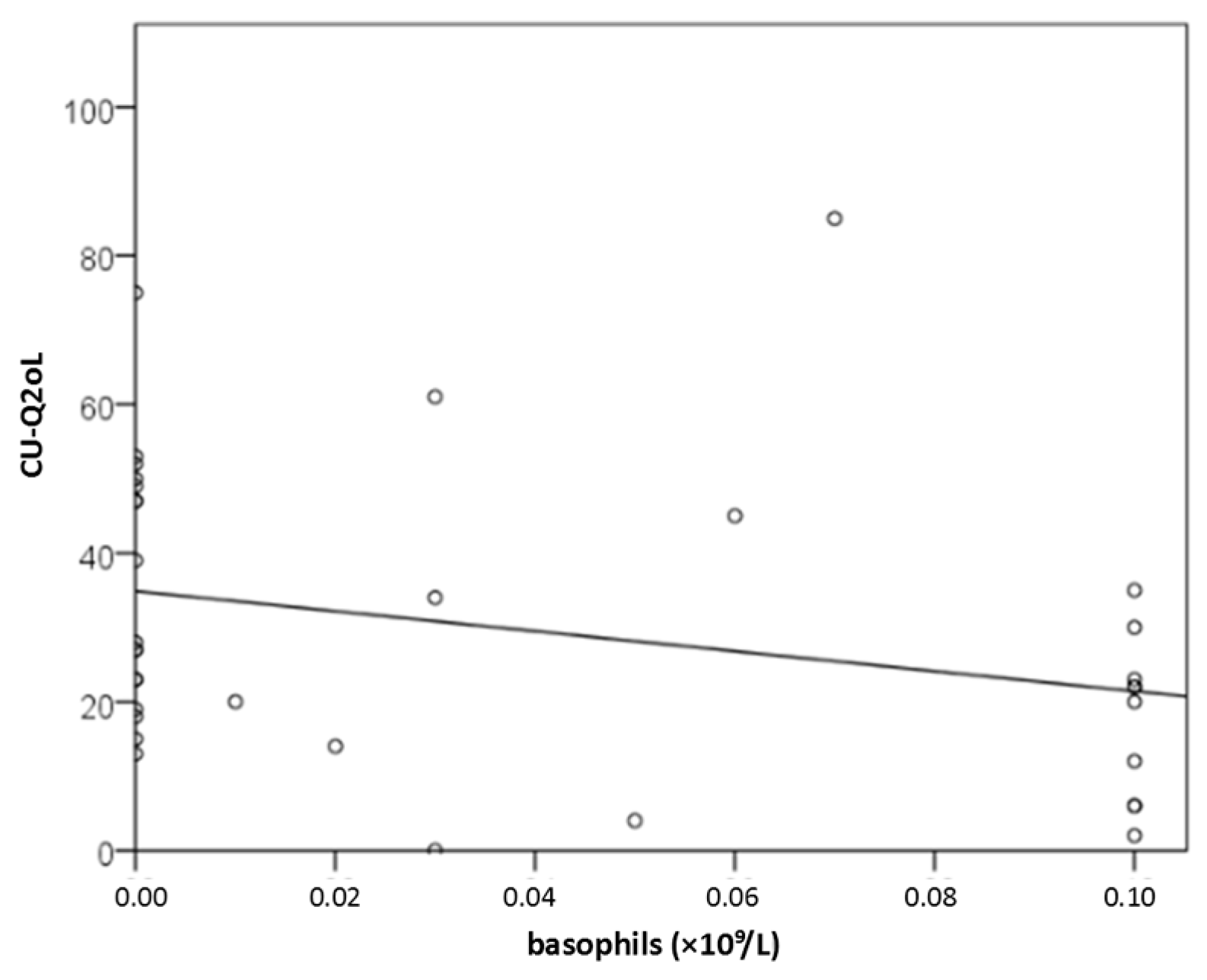

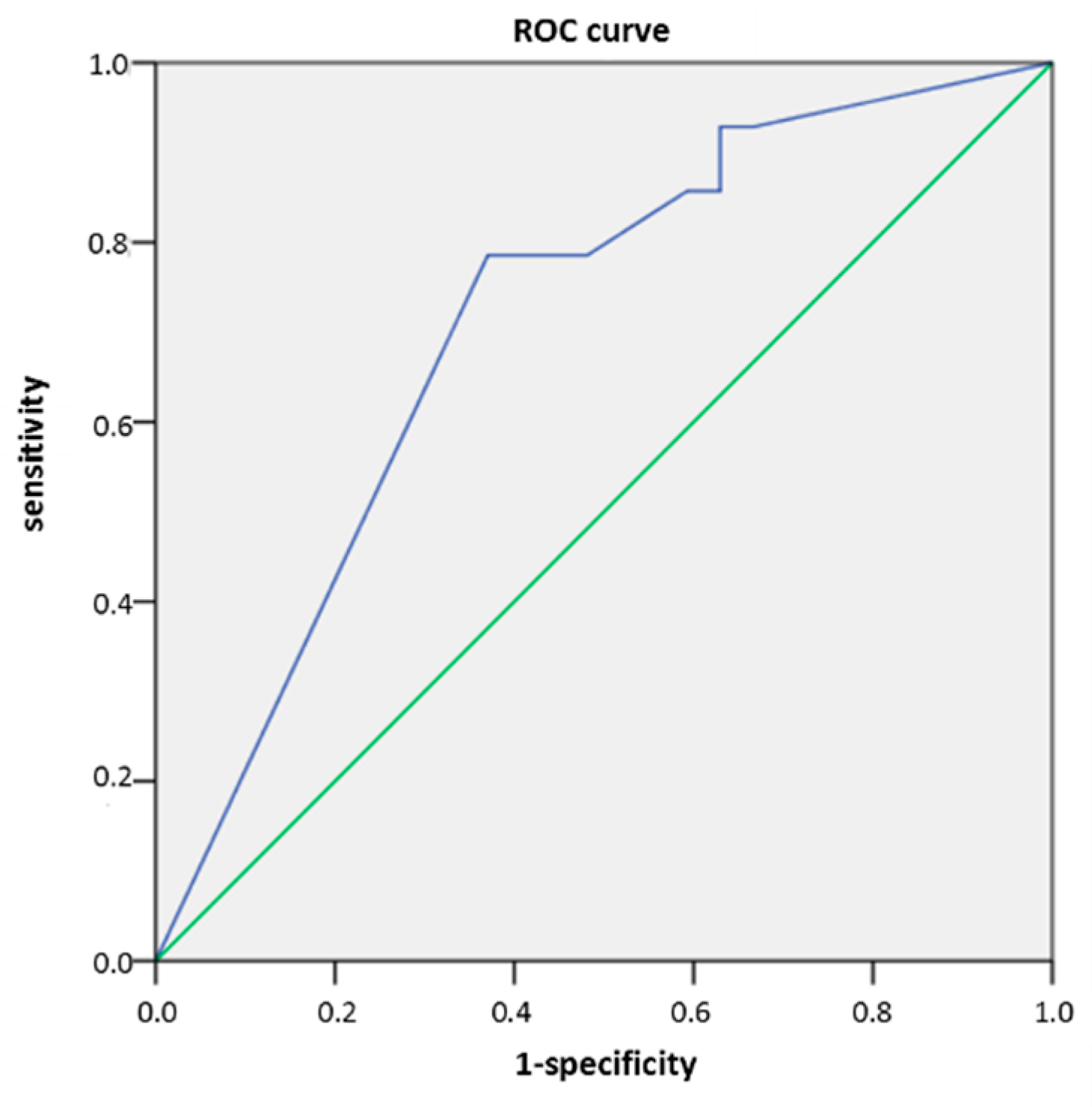

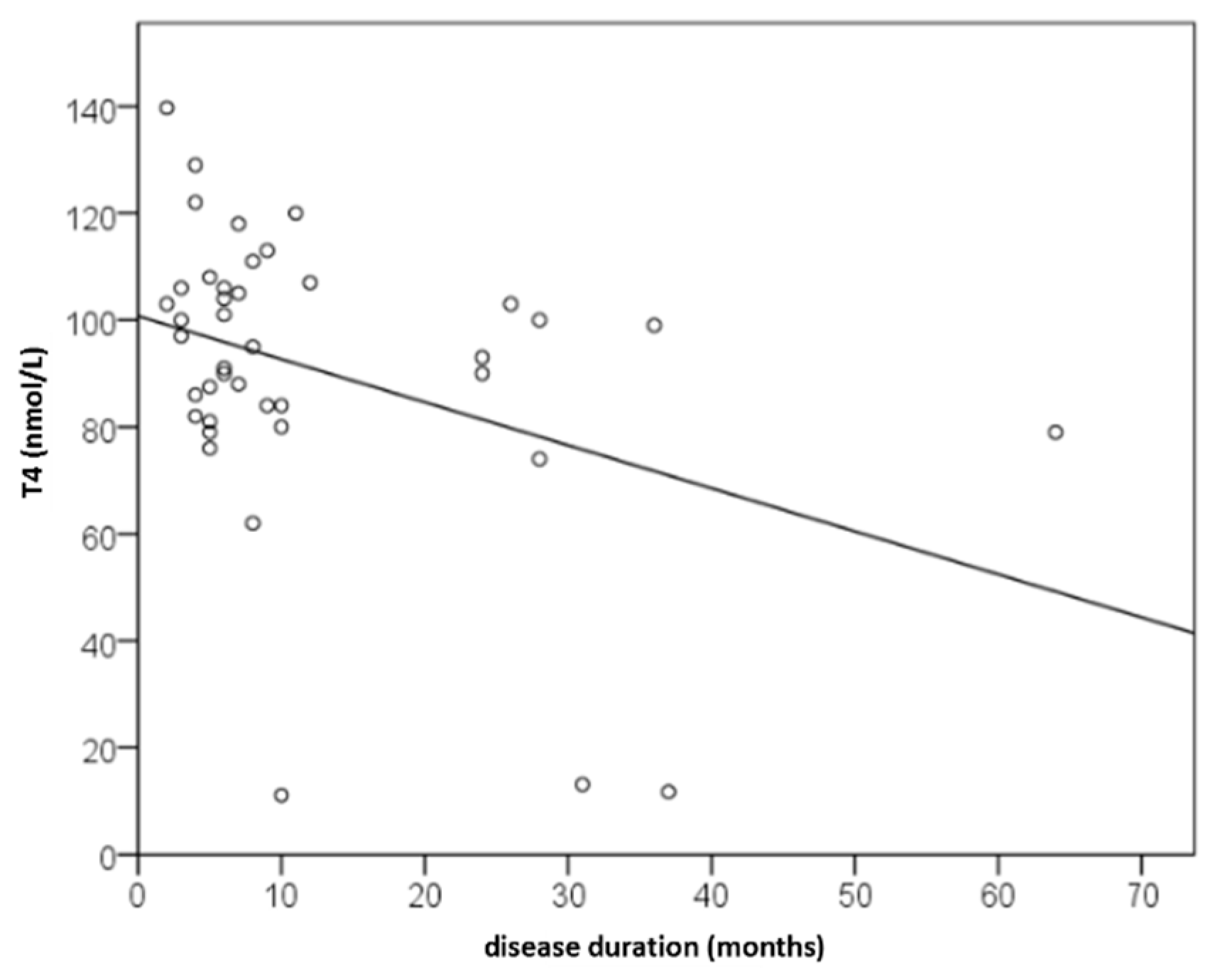

Background/Objectives: Recognizing several proposed serum biomarkers for chronic spontaneous urticaria, we investigated correlations among IL-6, ESR, CRP, CBC values, total IgE, thyroid abnormalities, ANA, D-dimer, and vitamin D in individuals with CSU/ Methods: In this prospective study of 41 patients with CSU, we assessed disease severity and quality of life using UAS7, daily UAS, UCT, DLQI, and CU-Q2oL. Concurrently, we measured serum IL-6, ESR, CRP, CBC, total IgE, thyroid antibodies and hormones, ANA, D-dimer, and vitamin D. Results: Serum parameter levels (IL-6, CBC, ESR, CRP, thyroid findigs, D-dimer, vitamin D) were most often slightly elevated, while basophil counts were frequently reduced. T4 showed a significant dependence on CSU duration(r=−0.328; p=0.036); basophil concentration significantly negatively correlated daily disease activity (daily UAS; r=−0.475; p=0.002); and with DLQI (r=−0.358 to −0.359; p≤0.034); basopenia was more frequent in patients with moderate/severe CSU than in those with mild disease or remission, as measured by daily UAS (79% vs. 37%; p=0.020); basophil concentration was the only biomarker useful in assessing CSU severity/daily UAS (sensitivity 78.6%; specificity 63%, p=0.028); ESR as the only significant predictor for UAS7 severity (p=0.038). Conclusions: These promising results highlight the need for replication in a study with a greater number of CSU patients.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

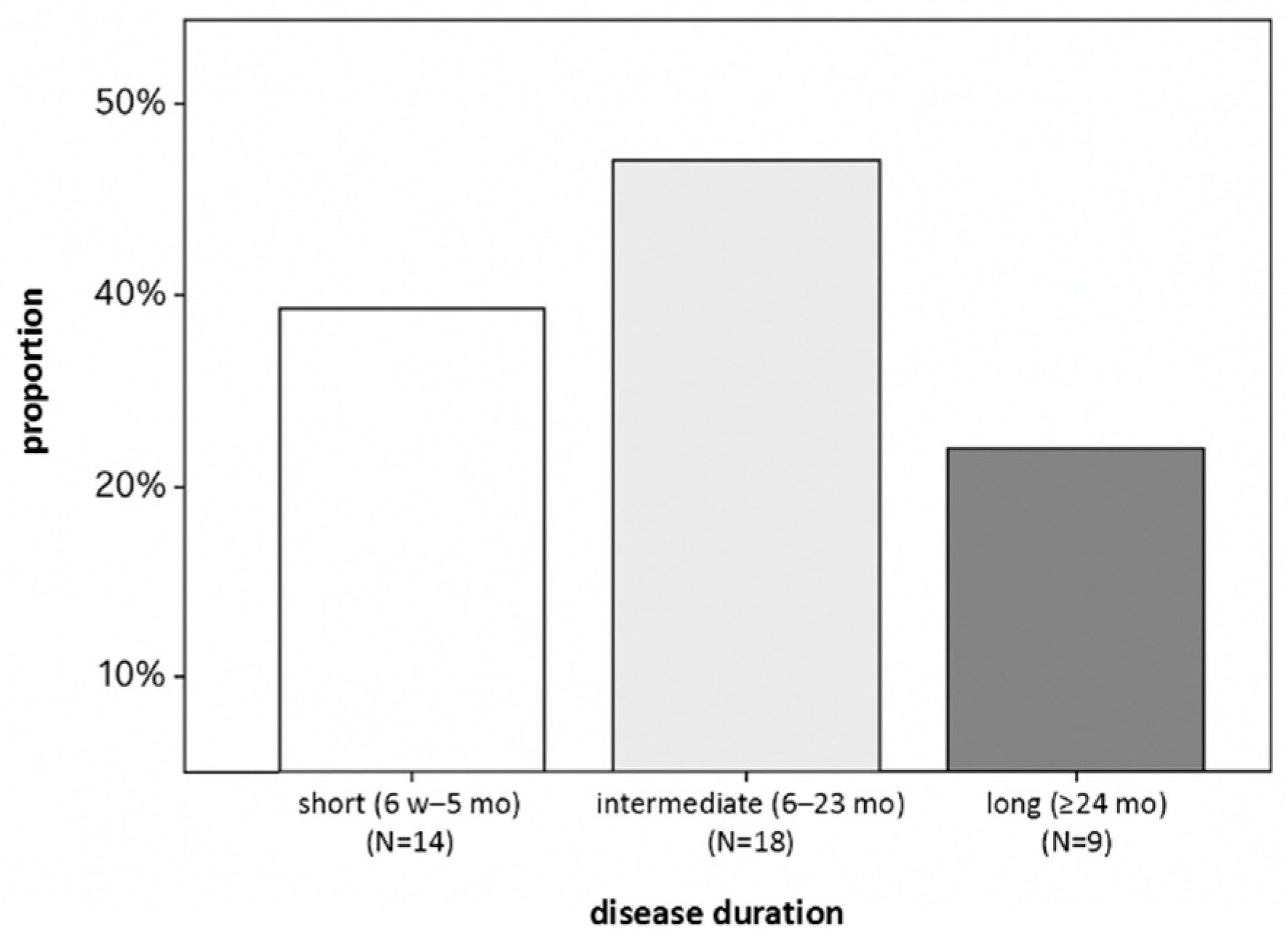

2.1. Study Population

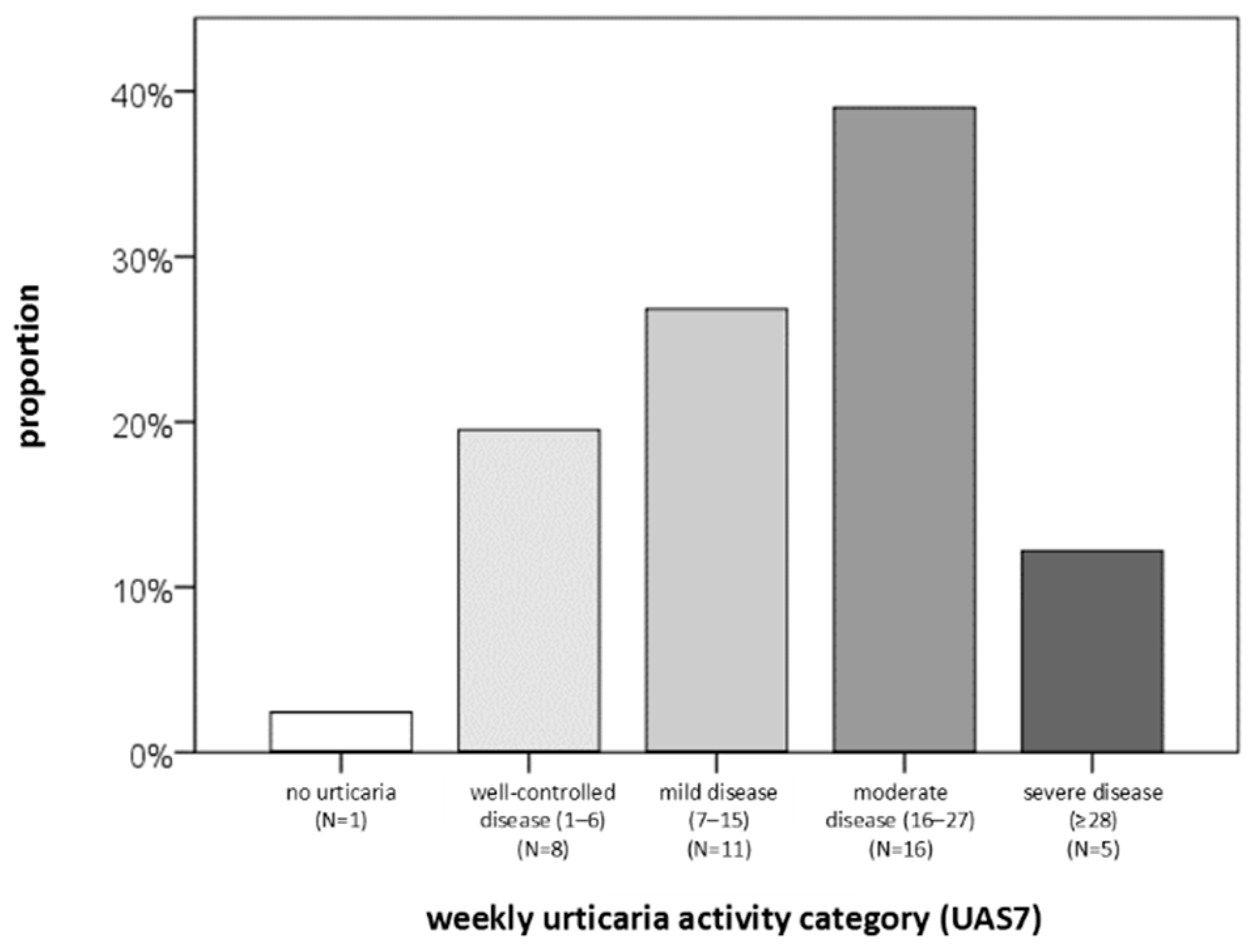

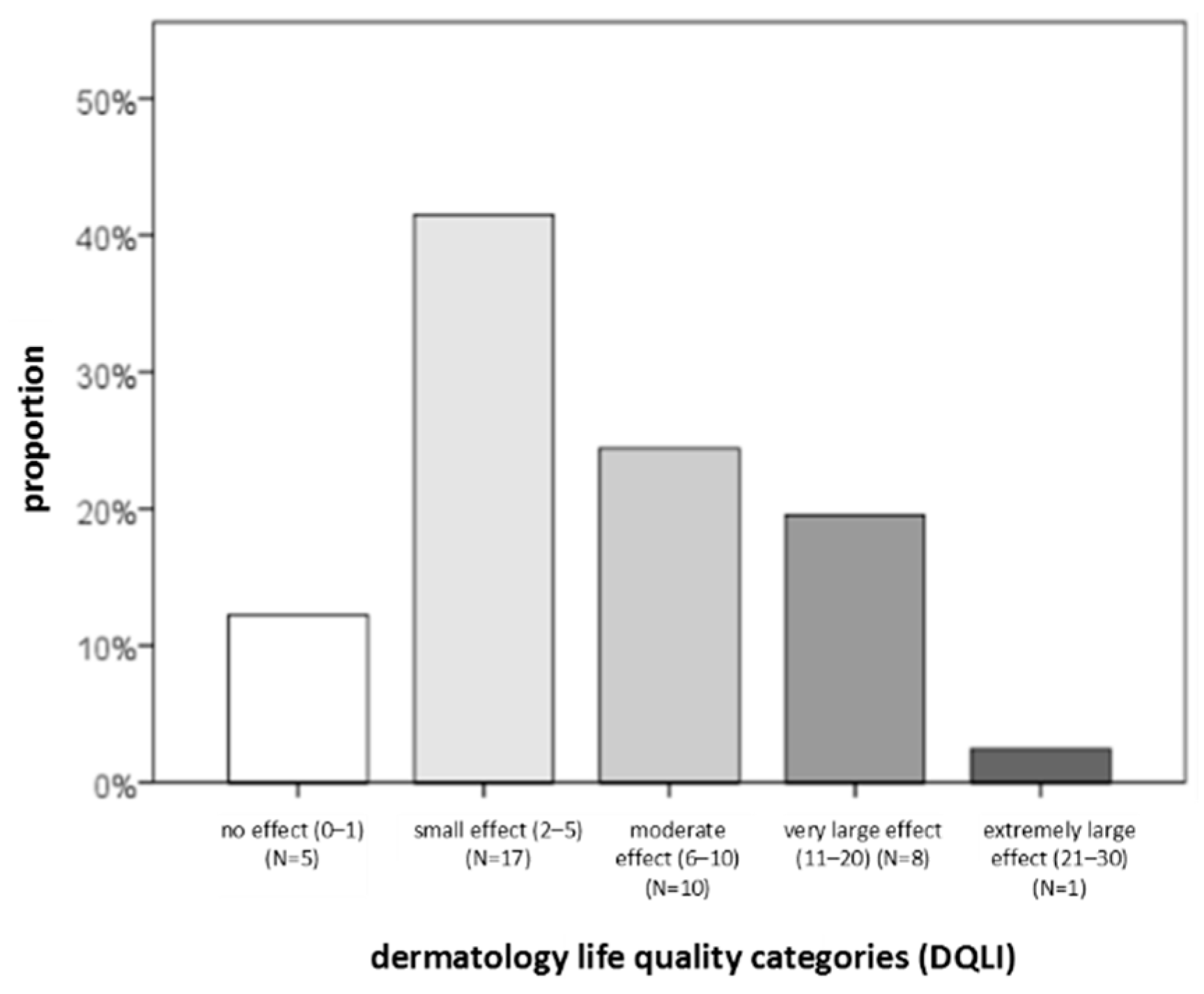

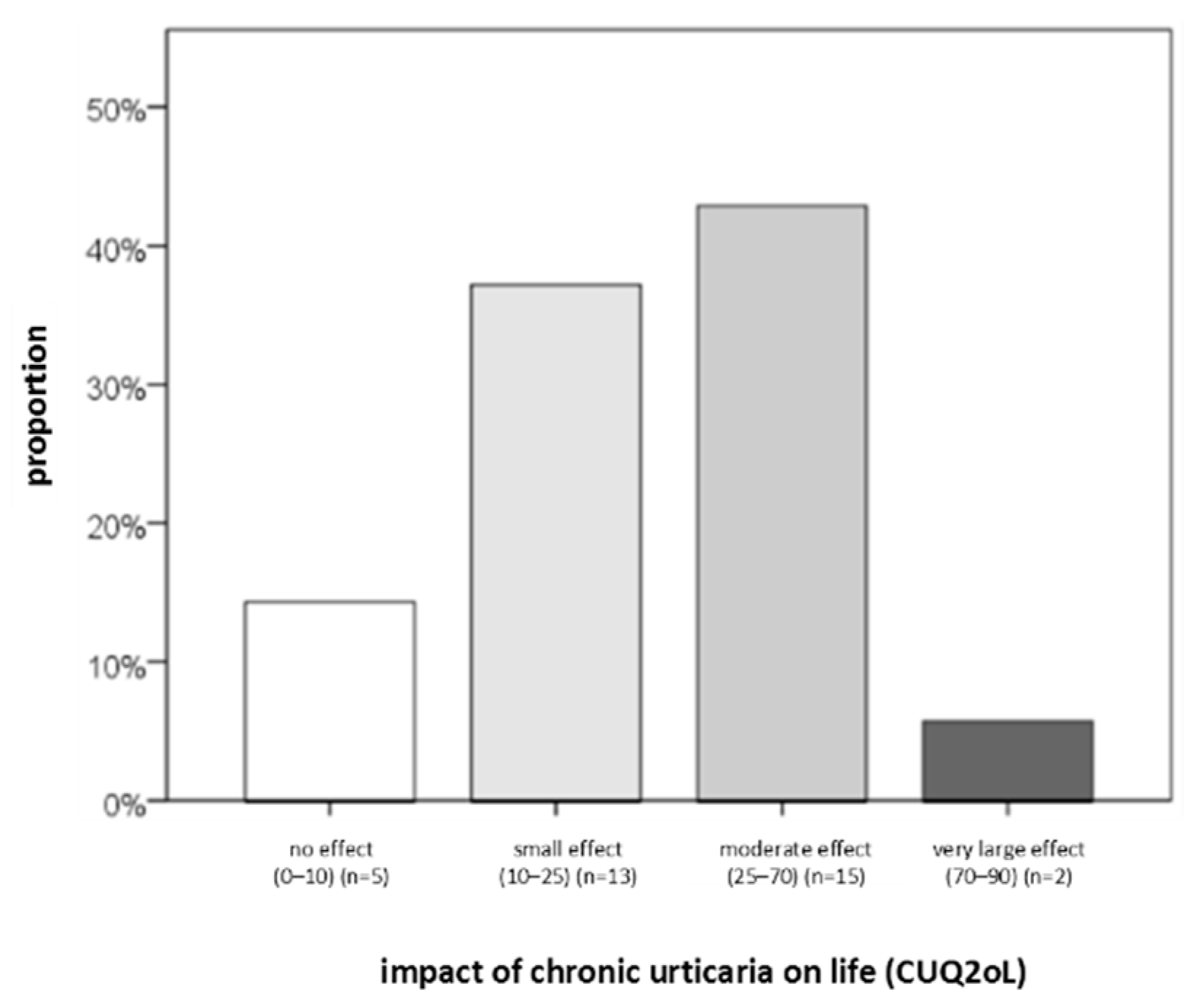

2.2. Descriptive Statistics

2.3. Associations of Serum Biomarkers with CSU Duration, Severity, Control, and QoL

2.3.1. Analysis of IL-6 Levels

2.3.2. Results for ESR

2.3.3. Results for CRP

2.3.4. Result for CBC (Basophils)

2.3.5. Results for Total IgE

2.3.6. Results for Thyroid Findings

2.3.7. Results for ANA

2.3.8. Results for D-Dimer

2.3.9. Results for Vitamin D

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

4.2. The Ethical Statement

4.3. Methods

4.3.1. Serum Parameters

4.3.2. Questionnaires

4.3.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zuberbier, T.; Abdul Latiff, A.H.; Abuzakouk, M.; Aquilina, S.; Asero, R.; Baker, D.; et al. The international EAACI/GA2LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2022;77(3):734-766. [CrossRef]

- Pozderac, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Artuković, M.; Stipić-Marković, A.; Kuna, M.; Ferček, I. Chronic inducible urticaria: Classification and prominent features of physical and non-physical types. Acta. Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica. Adriat. 2020;29:141–148. [CrossRef]

- Fricke, J.; Ávila, G.; Keller, T.; Weller, K.; Lau, S.; Maurer, M.; Zuberbier, T.; Keil, T. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in children and adults across the globe: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Allergy. 2020;75:423–432. [CrossRef]

- Bracken, S.J.; Abraham, S.; MacLeod, A.S. Autoimmune theories of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:627. [CrossRef]

- Kolkhir, P.; Giménez-Arnau, A.M.; Kulthanan, K.; Peter, J.; Metz, M.; Maurer, M. Urticaria. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2022;8:61. [CrossRef]

- Poddighe, D. The prevalence of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) in the pediatric population. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019;81:e149. [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.S.; Kaplan, A.P. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: the devil’s itch. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018;6(4):1097. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiardini, I.; Canonica, G.W.; La Grutta, S.; Braido, F. Clinically significant differences in patient-reported outcomes evaluations in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Curr. Opin. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2020;20(3):261-267. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleem, S.; Masood, Q.; Hassan, I. Correlation of C-reactive protein levels with severity – of chronic urticaria. Indian. J. Dermatol. 2014;59(6):636. [CrossRef]

- Kasperska-Zajac, A.; Sztylc, J.; Machura, E.; Jop, G. Plasma IL-6 concentration correlates with clinical disease activity and serum C-reactive protein concentration in chronic urticaria patients. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2011;41(10):1386–1391. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucmak, D.; Akkurt, M.; Toprak, G.; Yesilova, Y.; Turan, E.; Yildiz I. Determination of dermatology life quality index, and serum C-reactive protein and plasma interleukin-6 levels in patients with chronic urticaria. Postep. Dermatol. I Alergol. 2013;30(3):146–151. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Du, S.; Yan, S.; Zeng, J. Advanced biomarkers: therapeutic and diagnostic targets in urticaria. Int. Arch. Allergy. Immunol. 2021;182(10):917-931. [CrossRef]

- Rajappa, M.; Chandrashekar, L.; Sundar, I.; Munisamy, M.; Ananthanarayanan, P.H.; Thappa, D.M.; et al. Platelet oxidative stress and systemic inflammation in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2013;51(9),1789–1794. [CrossRef]

- Mishal, J.; Zeldin, Y.; Schlesinger, M. Clinical and laboratory features of antihistamine-resistant chronic idiopathic urticaria. Allergy. Asthma. Proc. 2011; 32(6): 460-466. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Chen, W.; Su, J.; et al. Association between C reactive protein and clinical characteristics in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Central South Univer. Med. Sci. 2017; 42(2): 168-172. [CrossRef]

- Huilan, Z.; Bihua, L.; Runxiang, L.; Jiayan, L.; Luyang, L.; Zhenjie, L. Features of antihistamine-resistant chronic urticaria and chronic urticaria during exacerbation. Indian. J. Dermatol. 2015; 60(3): 323. [CrossRef]

- Lugovic-Mihic, L.; Štrajtenberger, M.; Kuna, M.; Ladika-Davidović, B.; Barac, E.; Vilibić, M. Association Between Proinflammatory Cytokines IL-6 and TNF-Alpha, Psychological Stress and Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Severity. Preprints 2025, 2025081087. [CrossRef]

- Confino-Cohen, R.; Chodick, G.; Shalev, V.; Leshno, M.; Kimhi, O.; Goldberg, A. Chronic urticaria and autoimmunity: associations found in a large population study. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2012;129 (5):1307-1313. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, S.S. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: etiology and pathogenesis. Immunol. Allergy. Clin. North. Am. 2014;1;34(1):33–52. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, E.T.; Sterba, P.M.; Saini, S.S. Interval shifts in basophil measures correlate with disease activity in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy. Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;70(5):601-603. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, E.T.; Sterba, P.M.; Devine, K.B.; Vonakis, B.M.; Saini, S.S. Altered expression of chemoattractant receptorhomologous molecule expressed on TH2 cells on blood basophils and eosinophils in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2016;137(1):304-306. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jörg, L.; Pecaric-Petkovic, T.; Reichenbach, S.; et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of the effect of omalizumab on basophils in chronic urticaria patients. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2018; 48(2): 196-204. [CrossRef]

- Deza, G.; Bertolin-Colilla, M.; Pujol, R.M.; et al. Basophil FcepsilonRI expression in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a potential immunological predictor of response to omalizumab therapy. Acta. Dermato-Venereol. 2017; 97(6): 698-704. [CrossRef]

- Štrajtenberger, M.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Stipić-Marković, A.; Artuković, M.; Mihić, R.; Dolački, L.; Pravica, N.B.; Lokner, I. Analysis of coagulation factors in angioedema/urticaria: increased values of D-dimer and fibrinogen in isolated angioedema. Acta. Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica. Adriat. 2024 Jun;33(2):63-68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asero, R.; Marzano, A.V.; Ferrucci, S.; Cugno, M. D-dimer plasma levels parallel the clinical response to omalizumab in patients with severe chronic spontaneous urticaria. Int. Arch. Allergy. Immunol. 2017; 172(1): 40-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzano, A.V.; Genovese, G.; Casazza, G.; et al. Predictors of response to omalizumab and relapse in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a study of 470 patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019; 33(5): 918-924. [CrossRef]

- Ertas, R.; Ozyurt, K.; Atasoy, M.; Hawro, T.; Maurer, M. The clinical response to omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients is linked to and predicted by IgE levels and their change. Allergy. 2018; 73(3): 705-712. [CrossRef]

- Magen, E.; Chikovani, T.; Waitman, D.A.; Kahan, N.R. Factors related to omalizumab resistance in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy. Asthma. Proc. 2019; 40(4): 273-278. [CrossRef]

- Fok, J.S.; Kolkhir, P.; Church, M.K.; Maurer, M. Predictors of treatment response in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy. 2021 Oct;76(10):2965-2981. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuna, M.; Štefanović, M.; Ladika Davidović, B.; Mandušić, N.; Birkić Belanović, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Chronic Urticaria Biomarkers IL-6, ESR and CRP in Correlation with Disease Severity and Patient Quality of Life-A Pilot Study. Biomedicines. 2023;11(8):2232. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, K.; Groffik, A.; Church, M.K.; Hawro, T.; Krause, K.; Metz, M.; et al. Development and validation of the urticaria control test: a patient-reported outcome instrument for assessing urticaria control. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2014;133(5):1365-1372, 1372.e1-6. [CrossRef]

- Finlay, A.Y.; Khan, G.K. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210-216. [CrossRef]

- Kocatürk, E.; Kızıltaç, U.; Can, P.; Öztaş Kara, R.; Erdem T., Kızıltaç, K.; et al. Validation of the turkish version of the urticaria control test: correlation with other tools and comparison between spontaneous and inducible chronic urticaria. World. Allergy. Organ. J. 2019; 26;12(1):100009. [CrossRef]

- Kasperska-Zajac, A.; Brzoza, Z.; Rogala, B. Plasma concentration of interleukin 6 (IL-6), and its relationship with circulating concentration of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Cytokine. 2007;39(2):142-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasperska-Zajac, A.; Grzanka, A.; Machura, E.; Mazur, B.; Misiolek, M.; Czecior, E.; et al. Analysis of procalcitonin and CRP concentrations in serum of patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Inflamm. Res. 2013;62(3):309-312. [CrossRef]

- de Montjoye, L.; Darrigade, A.S.; Giménez-Arnau, A.; Herman, A.; Dumoutier, L.; Baeck, M. Correlations between disease activity, autoimmunity and biological parameters in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Eur. Ann. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2021; 53(2):55-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolkhir, P.; Altrichter, S.; Hawro, T.; Maurer, M. C-reactive protein is linked to disease activity, impact, and response to treatment in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy. 2018;73(4):940-948. [CrossRef]

- Yanase, Y.; Matsubara, D.; Takahagi, S.; Tanaka, A.; Ozawa, K.; Hide, M. Basophil characteristics as a marker of the pathogenesis of chronic spontaneous urticaria in relation to the coagulation and complement systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(12):10320. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poddighe, D.; Vangelista, L. Effects of omalizumab on basophils: potential biomarkers in asthma and chronic spontaneous urticaria. Cell. Immunol. 2020;358:104215. [CrossRef]

- Gericke, J.; Metz, M.; Ohanyan, T.; Weller, K.; Altrichter, S.; Skov, P.S.; et al. Serum autoreactivity predicts time to response to omalizumab therapy in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2017;139(3):1059-1061.e1. [CrossRef]

- Metz, M.; Torene, R.; Kaiser, S.; Beste, M.T.; Staubach, P.; Bauer, A.; et al. Omalizumab normalizes the gene expression signature of lesional skin in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Allergy. 2019;74(1):141-151. [CrossRef]

- Akdogan, N.; Demirel Ogut, N.; Dogan, S.; Atakan, N. Long-term effects of omalizumab on peripheral blood cells and C-reactive protein levels in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Dermatol. Ther. 2019;32(4):e12966. [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, M.E. Comparison of the Patients with Chronic Urticaria Who Responded and Did Not Respond to Omalizumab Treatment: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Int. Arch. Allergy. Immunol. 2022;183(11):1209-1215. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Qiu, L.; Wu, J.; Qi, Y.; Wang, H.; Qi, R.; et al. IgE and IgG anti-thyroid autoantibodies in Chinese patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria and a literature review. Allergy. Asthma. Immunol. Res. 2022;14(1):131-142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 27./110. Esmaeilzadeh, H.; Eskandarisani, M.; Nabavizadeh, H.; Alyasin, S.; Vali, M.; Mortazavi, N. Investigating the association of atopy and aeroallergen sensitization and chronic spontaneous urticaria. Postepy. Dermatol. Alergol. 2022;39(1):121-125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunkajohnsak, S.; Jiamton, S.; Tuchinda, P.; Chularojanamontri, L.; Rujitharanawong, C.; Chanchaemsri, N.; et al. Do antinuclear antibodies influence the clinical features of chronic spontaneous urticaria?: a retrospective cohort study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022; 29;2022:7468453. [CrossRef]

- Grzanka, A.; Machura, E.; Mazur, B.; Misiolek, M.; Jochem, J.; Kasperski, J.; et al. Relationship between vitamin D status and the inflammatory state in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Inflamm (Lond). 2014; 11(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-11-2.

- Wu, C.H.; Eren, E.; Ardern-Jones, M.R.; Venter, C. Association between micronutrient levels and chronic spontaneous urticaria. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015:926167. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Ha, E.K.; Jee, H.M.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, M.A.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of urticaria with a focus on chronic urticaria in children. Allergy. Asthma. Immunol. Res. 2017;9(3):212-219. [CrossRef]

- Thorp, W.A.; Goldner, W.; Meza, J.; Poole, J.A. Reduced vitamin D levels in adult subjects with chronic urticaria. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2010;126(2):413; author reply 413-414. [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.R.; Jung, K.E.; Koo, D.W.; Lee, J.S. Vitamin D as a marker for disease severity in chronic urticaria and its possible role in pathogenesis. Ann. Dermatol. 2015;27(4):423-430. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Mandušić, N.; Dasović, M.; Pondeljak, N.; Kuna, M.; Pozderac, I. Vitamin D supplementation in patients with atopic dermatitis, chronic urticaria and contact irritant and allergic dermatitis—possible improvement without risk. Folia. Med. 2022; 64(3):467–477. [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | mean ± SD | median | IQR | Min | Max |

| Disease duration (months) | 41 | 12,2 ± 12,8 | 7 | 5 – 11,5 | 2 | 64 |

| vitamin D (nmol/L ) | 41 | 60,3 ± 24,3 | 61,0 | 43,5 – 72,5 | 23,0 | 113,0 |

| Percentage of basophils (%) | 41 | 0,66 ± 0,36 | 0,50 | 0,35 – 0,80 | 0,0 | 1,7 |

| Basophil concentration (x 109/L) | 41 | 0,03 ± 0,4 | 0,00 | 0,00 – 0,09 | 0,00 | 0,10 |

| ESR (mm/3,6 ks) | 41 | 8,9 ± 6,9 | 6,0 | 4,0 – 12,5 | 2,0 | 28,0 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 39 | 0,48 ± 0,48 | 0,32 | 0,21 – 0,54 | 0,10 | 2,73 |

| total IgE (kIU/L) | 41 | 203,1 ± 396,7 | 94,0 | 18,5 – 171,0 | 3,0 | 2292,0 |

| anti-TG (kIU/L) | 41 | 24,3 ± 107,3 | 0,9 | 0,7 – 2,3 | 0,3 | 677,3 |

| Variables | serum IL-6 (pg/mL) | |

| CRP (mg/L) | R | 0,379 |

| P | 0,016 | |

| r | N | 40 |

| vitamin D (nmol/L) | R | 0,11 |

| P | 0,5 | |

| N | 40 | |

| Basophil presentage (%) | R | −0,097 |

| P | 0,553 | |

| N | 40 | |

| Basophil concentration (x 109/L) | R | −0,146 |

| P | 0,368 | |

| N | 40 | |

| ESR (mm/3,6 ks) | R | 0,319 |

| P | 0,045 | |

| N | 40 | |

| D-dimers (mg/L) | R | 0,606 |

| P | < 0,001 | |

| N | 39 |

| total IgE (kIU/L) | R | 0,207 |

| P | 0,199 | |

| N | 40 | |

| TSH (mIU/L) | R | 0,275 |

| P | 0,09 | |

| N | 39 | |

| T3 (nmol/L) | R | 0,370 |

| P | 0,019 | |

| N | 40 | |

| T4 (nmol/L) | R | 0,321 |

| P | 0,043 | |

| N | 40 | |

| anti-TPO (kIU/L) | R | −0,143 |

| P | 0,384 | |

| N | 39 | |

| anti-TG (kIU/L) | R | 0,252 |

| P | 0,117 | |

| N | 40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.