1. Introduction

Chronic urticaria (CU) is a relatively common skin disease that has a significant impact on patients due to its unpredictability, associated problems in daily life, persistence, and occasional therapeutic inefficacy, which can all pose a therapeutic challenge [

1,

2]. CU is characterized by the recurrent appearance of wheals and/or angioedema, lasting for at least six weeks. There are two subtypes: chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) and inducible urticaria. For CSU, the most common form of CU, wheals are often accompanied by intense pruritus [

3,

4]. Patients experience sleep disturbances and have a reduced quality of life and a higher propensity for psychiatric comorbidity and/or psychological burden, such as depression and anxiety [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Although not life-threatening, symptoms of CSU significantly affect various aspects of everyday life [

1,

2].

In the pathogenesis of CU, skin mast cells and basophils are key inflammatory cells that, after being stimulated by IgE, are activated and release proinflammatory mediators, including histamine, leukotriene C4, platelet-activating factor (PAF), IL-13, IL-25, CXCL8/IL-8, and others [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Thus, mast cells secrete many preformed mediators (such as tryptase, heparin, chymase, cathepsin G, carboxypeptidase A3, renin, etc.) and prostaglandin D2. Binding of histamine to its receptor H4R triggers mast cell activation, which involves stimulation of intracellular calcium mobilization and ultimately leads to the expression of proinflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), tumor growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, activation-regulated, normally expressed and secreted by T-cells (RANTES) and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1). Thus, activated mast cells release mediators associated with inflammation (histamine, TNF-α, MMP-9, IL-4, IL-6 and others), important for T cell-mediated inflammation and extravasation and recruitment of leukocytes to the area of skin inflammation. Consequently, significantly higher serum levels of histamine, leukotriene C4, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6 and TGF-β were confirmed in patients with chronic urticaria (CUR) than in healthy individuals (mast cells produce significant amounts of the cytokines IL-6 and IL-5 [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, it should be mentioned that many other factors and pathogenetic processes participate in the complex pathogenesis of chronic urticaria [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Research has shown that patients with CSU often exhibit elevated inflammatory markers and mediators. According to the reccomendations for CSU, in diagnostic procedures it is necessary to evaluate differential blood count (DBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and/or C-reactive protein (CRP), as well as other factors like IgG anti-TPO and total IgE values [

1,

22]. In addition, increased serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α have been observed in CU patients. These proinflammatory cytokines are considered potential biomarkers of CSU, as their plasma levels are elevated in patients with more active disease and significantly lower during spontaneous remission. This implies that CSU is an immune-mediated chronic inflammatory condition arising from immune activation following exposure to various triggering factors [

23,

24,

25,

26].

Among the psychological influences on CU, the negative impact of stress is frequently reported, either when observed in CU patients by healthcare professionals or when reported by patients themselves [

22,

27]. The stress response involves physiological mechanisms primarily governed by two neuroendocrine systems: the sympatho-adrenal-medullary (SAM) system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. In response to perceived stress, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), stimulating the anterior pituitary to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), subsequently leading to the release of cortisol, a biomarker for stress level, from the adrenal cortex) [

27,

28,

31,

32].

The aim of our study was to investigate the correlation between clinical features of CSU (disease severity and quality of life) and levels of serum inflammatory parameters (IL-6 and TNF-α), as well as stress levels (serum cortisol levels and perceived psychological stress) by comparing CSU patients and healthy controls (HCs). Additionally, the study aimed to determine the intercorrelation of the measured parameters and their relationship with CSU severity, and to identify differences in the measured factors between CSU patients and HCs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

We performed a cross-sectional case-control study at the University Hospital Center “Sestre Milosrdnice”, Department of Dermatology and Venereology. The study included patients with CSU who were triaged during dermatological evaluations at the Allergy and Clinical Immunology Outpatient Clinic. All participants were examined by a board-certified dermatologist. The control group consisted of healthy individuals, matched to the CSU patients by age and sex, who met the inclusion criteria. Each participant was informed about the study protocol, and written informed consent was obtained prior to participation. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Center “Sestre Milosrdnice”, Zagreb, Croatia in January 2022 (Number of protocol: 251-29-11-22-01-9),

2.2. Participants

Participants were recruited from a pool of CSU follow-up patients who met all the inclusion criteria (18 plus years of age, CSU diagnosis based on clinical guidelines for dermatological examination, and a patient history involving wheals and/or angioedema lasting more than 6 weeks) [

1]. Patients with isolated angioedema or isolated chronic inducible urticaria were excluded.

Exclusion criteria for all participants included use of psychoactive medications, corticosteroids, or immunosuppressants within one month prior to enrollment; vaccination within 28 days prior to the study; pregnancy or breastfeeding; use of oral contraceptives; follicular phase of the menstrual cycle; presence of systemic inflammatory or autoimmune diseases; history of neoplasms; previously diagnosed psychiatric disorders; and diseases of the oral mucosa.

Inclusion criteria for healthy controls were an age of 18 years or over and the absence of skin, inflammatory, or autoimmune diseases.

In total, 46 participants were included in the study: 23 patients with diagnosed CSU and 23 healthy controls. The sample consisted of individuals aged 21 to 73 years (median age: 35; interquartile range: 28–48), with 30 out of 46 (65%) being female.

2.3. Questionnaires

Disease severity in CSU patients was evaluated using the Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) [

1].

The Urticaria Activity Score (UAS) asks respondents to assess both urticaria (hives) and pruritus (itching) severity during the previous 24 hours. Each are scored from 0 to 3, 0 indicating an absence of symptoms, 1 being mild, 2 being moderate, and a score of 3 indicating severe severity. The UAS7 assesses severity on a 1 to 42-point scale over a period of 7 days (1–6 points = well-controlled disease, 7–15 = mild disease, 16–27 = medium severity, and 28–42 points = severe disease [

1,

33].

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): On this 10-question survey, respondents are asked to assess the impact of their disease over the previous week on certain areas of their life—symptoms and feelings, daily activitie, free time, work and school, personal relationships, and treatment. For each question, answers range from 0 to 3 points. A total survey score of 0 to 1 indicates no impact from the disease on the patient’s life, 2 to 5 indicates a small impact, 6–10 is a moderate impact, 11–20 is a very large impact, and a score of 21 to 30 indicates a very large impact [

34].

2.4. Serum Biomarker Analysis

Blood samples were collected in the morning between 07:00 and 09:00 for the analysis of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) and cortisol levels.

Serum concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α were measured using the chemiluminescence method on an Immulite 1000 analyzer. Analyses were performed at the Department of Oncology and Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital Center “Sestre Milosrdnice”, using the Immulite 1000 (Siemens) and FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson) analyzers.

The reference values for serum cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α (IMMULITE® 1000 and FACSCalibur™) were as follows: for IL-6: 0–7 pg/mL, while TNF-α: 0–8.1 pg/mL [

35].

An electrochemiluminescent immunoassay (ECLIA) was used to measure serum cortisol levels. The reference values for measured cortisol levels (Roche, ECLIA) were 133–537 nmol/L.

2.5. Psychological Stress Analysis

Psychological stress was assessed both by measuring serum cortisol levels and by using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) questionnaire [

36,

37,

38,

39].

Perceived stress scores from the PSS were also recorded for all participants in this study, as PSS has high reliability [

36]

. All participants (patients and healthy participants) completed the PSS questionnaire, which examines stress experienced during the past month. The PSS questionnaire includes 10 Likert-scale questions (0–4). Finally, the total score reflects stress levels and includes three groups of stress experience: low stress (0–13 points), moderate stress (14–26 points), high stress (27–40 points).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Since there were fewer than 30 respondents per group, non-parametric statistics were used to analyze continuous data (Mann-Whitney test). The Fisher test was used to compare frequencies, and the effect size was calculated using the formula r = Z/√N for Mann-Whitney and Cramer's V for the Fisher test. The association between the continuous variables was checked by analyzing the scatter plot and Spearman's correlation. Effect size and correlation strength were interpreted using Cohen's criteria: r = 0.25 – 0.3 = small effect size /low correlation, 0.3 – 0.5 = moderate, 0.5 – 0.7 = large, and >0.7 = very large. Commercial software (IBM SPSS 22; IBM Corp., Armonk, US) was used.

3. Results

Analysis of participants by age and sex revealed no significant differences between the patient and control groups. Furthermore, no differences in the examined parameters were found between male and female participants. Serum biomarkers and perceived stress were not associated with age in the total sample.

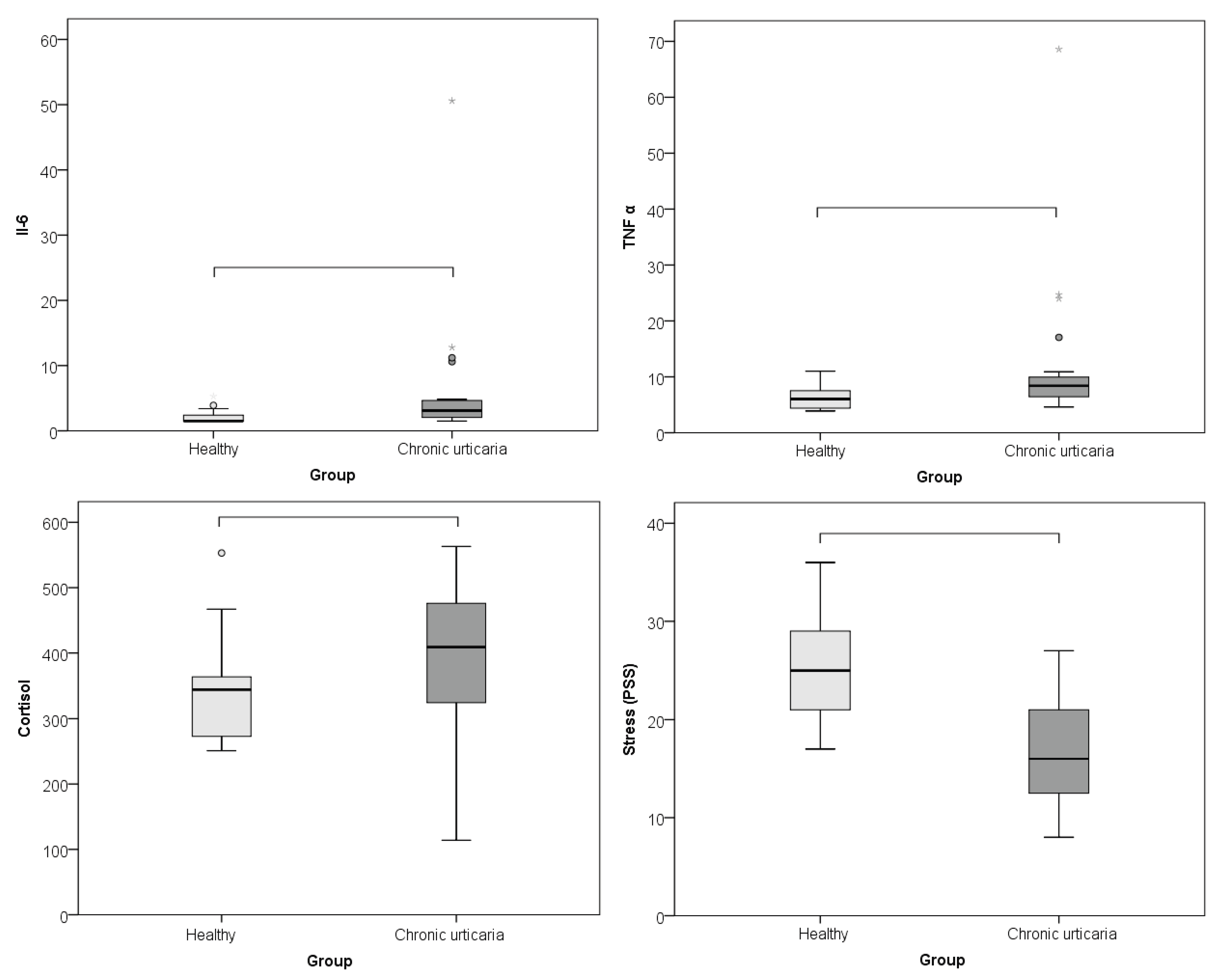

The comparison between CU patients and healthy controls of serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and morning cortisol, as well as perceived psychological stress (PSS), showed that subjects with CU had significantly higher levels of IL-6 (p = 0.002; r = -0.460), TNF-α (p = 0.001; r = -0.485), cortisol (p = 0.015; r = -0.360), and lower perceived stress/PSS (p < 0.001; r = -0.608) than healthy individuals (

Table 1;

Figure 1). The effect was large for perceived stress and moderate for cortisol, IL- 6 and TNF-α.

The analysis of the correlation between serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and morning cortisol levels with disease severity and quality of life in patients with CSU revealed the following: The severity of CSU showed a positive linear correlation with serum cortisol levels (r = 0.463; p = 0.046) and with impaired quality of life (r = 0.715; p < 0.001). Additionally, impaired quality of life was positively correlated with perceived stress (r = 0.523; p = 0.010) and negatively correlated with age (r = –0.529; p = 0.009) (

Table 2).

When looking at correlations for both healthy persons and CSU patients, IL-6 correlated with perceived stress (r = -0.402; p = 0.006) linearly, negatively and moderately. As stress increased, IL-6 decreased. There were no associations between other parameters.

4. Discussion

Psychological stress is often reported as a trigger for, or contributing factor to, chronic dermatoses such as CU, yet research on this topic remains limited. One major challenge lies in accurate objectivization of stress, which can vary significantly between individuals. For this, psychometric questionnaires are valuable tools for assessing psychological stress, primarily by evaluating changes in behavior and cognitive functions. Additionally, serum cortisol, the most commonly used biomarker of stress, is also frequently measured. In recent years, scientific interest has increasingly focused on the psychoneuroimmunological (PNI) approach, which explores the impact of stress on disease onset and progression [

31,

40,

41]. However, despite considerable theoretical insight, clinical studies with dermatological patients that simultaneously examine psychological, neuroendocrine, and immune parameters—and their interrelations—remain scarce. This gap in the literature was a key motivating factor for our study. Our findings show that CSU patients exhibited significantly higher serum cortisol levels, but lower perceived stress (PSS) scores compared to HCs. This suggests that, although CSU patients exhibit a significant biologically measurable level of stress, their subjective perception of stress may be reduced. This could be, at least partially, explained by the mobilization of positive coping and adjustment mechanisms due to the long duration of CSU. Notably, CSU severity in our sample was positively correlated with cortisol levels and associated with poorer quality of life, implying a meaningful link between disease severity, stress level, and quality of life impairment. This aligns with existing evidence indicating a bidirectional relationship between chronic illnesses like CU and psychological stress: chronic skin conditions may induce stress, while chronic stress can exacerbate or trigger disease activity [

30,

41].

The stress response involves the adrenal and sympathetic components of the neuroendocrine system, both of which exert significant influence on immune function [

31]. Lymphoid tissues receive signals via sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons, thereby modifying immune cell behavior. The immune system comprises both innate and adaptive components, including cellular and humoral immunity, coordinated by cytokine mediators that facilitate intercellular communication. Under stress, ACTH stimulates adrenal cortisol production. Unlike the immediate effects of sympathetic activation and adrenaline release, prolonged cortisol exposure may impair immune functioning depending on stress intensity and duration [

31,

42]. While some previous studies have shown reduced cortisol levels in CU patients, an inverse correlation has also been observed between cortisol and psychological stress intensity [

43]. In our study, CSU patients demonstrated higher cortisol levels and lower perceived stress, although these two variables did not correlate. Previous studies also reported that IL-18 and CRP (regulated by cortisol) positively correlated with CSU severity (measured by the UAS), whereas cortisol showed a negative correlation, which is consistent with our findings. These results suggest that chronic stress in CU patients may reduce cortisol levels and elevate inflammatory mediators [

44].

CU is associated with increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, and these cytokines contribute to local skin inflammation and recruit immune cells involved in lesion resolution. Some also activate the sympathetic nervous system, promoting catecholamine release. Among these, IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α are particularly important for HPA axis activation and for initiating and sustaining skin inflammatory responses [

45]. The type and duration of psychological stress are also crucial. Acute stress, through HPA axis activation and elevated cortisol, may suppress proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), whereas chronic stress can induce cortisol resistance, paradoxically resulting in elevated cytokine levels [

46]. In our study, the duration of CSU was not associated with cytokine levels or any other measured variable.

Additionally, in CSU patients, impaired quality of life was positively correlated with perceived stress and negatively with age. This implies that both stress perception and younger age negatively impact quality of life. Younger adults could exhibit less adaptive stress-coping capacities and also experience greater disruption in work, family, or educational responsibilities due to disease burden. Moreover, IL-6 was significantly associated with perceived stress, showing a moderate negative linear correlation—as perceived stress increased, IL-6 levels decreased. This finding indicates a potential link between proinflammatory cytokines and stress in CSU manifestations.

Consistent with other studies, we confirmed that CSU patients had significantly higher serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-α compared to healthy controls (p = 0.002, p = 0.001). Grzanka et al. reported elevated TNF-α in patients with moderate to severe CSU, but no significant difference between mild CSU and healthy individuals [

47]. Genetic predispositions have also been suggested [

20,

21,

48]. For instance, Tavakol et al. found that polymorphisms in the TNF-α and IL-6 genes may influence CU susceptibility. These cytokines play roles in the initiation and progression of inflammatory, autoimmune, and infectious diseases, including CU [

48]. TNF-α and IL-6 activate immune cells, regulate cellular differentiation and apoptosis, and are secreted by activated inflammatory cells and macrophages, creating a feedback loop of sustained inflammation [

48]. While Habal et al. found no significant differences in IL-6 or TNF-α levels between patient with CU/angioedema and controls, other studies have demonstrated clinical efficacy of TNF-α inhibitors in CU patients [

49,

50]. In our cohort, IL-6 levels were significantly elevated and negatively correlated with perceived stress, reinforcing the complexity of these interactions. CU patients have also been shown to exhibit elevated psychological stress levels [

52], which our findings support through significant differences in stress indicators between CSU patients and healthy controls. When interpreting these results, it is important to recognize and highlight the bidirectional relationship between chronic diseases and stress, where stress may be both a cause and a consequence [

30,

41].

A significant negative correlation between psychological stress and CU indicates the need for a multidisciplinary approach to treatment. Regarding therapeutic implications, for instance, antidepressants have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects and reduction of urticarial symptoms in chronic skin disorders, suggesting their potential use beyond psychiatric comorbidities [

53]. In addition, there are other measures and approaches to treating patients with CSU that include various psychological methods that can be used in addition to standard treatment of the disease [

54,

55,

56].

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has simultaneously compared stress levels and proinflammatory markers in the same CSU patient group with healthy controls, while also considering disease severity. Its limitation involves a small number of patients, therefore future research would be needed that should include a larger number of patients. Our findings support the existence of significant differences in immunological, neuroendocrine, and psychological parameters between CSU patients and healthy individuals. They also provide insight into how these factors relate to disease severity and quality of life. Understanding these correlations contributes to a better grasp of CSU pathogenesis and highlights opportunities for future research and a more effective, multidisciplinary therapeutic approach, ultimately improving outcomes and quality of life in affected patients. The identification of serological biomarkers for urticaria activity, and the clarification of their relationship with psychological states such as stress, remain priority areas for further research, as mentioned in current trends and perspectives for CU [

1].

5. Conclusions

In CSU patients, significantly elevated serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α, higher cortisol levels, and lower perceived stress (PSS) scores, when compared to healthy controls, indicate the involvement of both psychological stress and immune mechanisms in the pathophysiology of CSU. Furthermore, the negative correlation between IL-6 and perceived stress suggests a complex relationship between inflammation and psychological stress.

The positive linear correlation between CSU severity and serum cortisol levels, as well as with impaired quality of life, further supports the association between stress and the clinical expression of CSU. Additionally, impaired quality of life positively correlated with perceived stress and negatively with age, highlighting the broader psychosocial impact of the disease, particularly in younger individuals.

Taken together, these findings highlight the significant influence of psychological stress on the course and severity of CSU, and emphasize the need for a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of CSU patients.

The manuscript is not under consideration elsewhere.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.-M.; methodology,. M.Š.; M.K.; E.B. and M.V.; validation, M.Š.; M.K.; and B.L.-D.; formal analysis, M.Š.; M.K.; and B.L.-D..; investigation B.L.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.-M.; E.B. and M.V. .; writing—review and editing, L.L.-M.; E.B. and M.V..; visualization, B.L.-D.. E.B. and M.V.; supervision, L.L.-M.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

The written informed consent for publication this article was given to our patients. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CU |

chronic urticaria |

| QoL |

quality of life |

| CSU |

chronic spontaneous urticaria |

| TGF-β1 |

tumor growth factor-β1 |

| MIP-1α |

macrophage inflammatory protein 1α |

| RANTES |

regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted |

| MCP-1 |

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 |

| DBC |

differential blood count |

| ESR |

erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| IL- |

interleukin |

| TNF-α |

tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| SAM |

sympatho-adrenal-medullary system |

| HPA |

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis |

| CRH |

corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| ACTH |

adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) |

| DLQI |

Dermatology Life Quality Index |

| UAS |

Urticaria Activity Score |

| ECLIA |

electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay |

| PSS |

perceived Stress Scale |

References

- Zuberbier, T.; Latiff, A. H. A.; Abuzakouk, M.; Aquilina, S.; Asero, R.; Baker, D.; Bangert, C.; Ben-Shoshan, M.; Bernstein, J. A.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; et al. The International EAACI/GA²LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI Guideline for The Definition, Classification, Diagnosis, and Management of Urticaria. Allergy 2022, 77, 734–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, L.; Stitt, J. Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: Quality of Life and Economic Impacts. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2024,44(3):453-467. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Song, Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, Z.; Wang, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; et al. Beyond the Itch: The Complex Interplay of Immune, Neurological, and Psychological Factors in Chronic Urticaria. J Neuroinflammation. 2025, 22(1):75. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, BR.; Pio-Abreu, JL.; Figueiredo, A.; Misery, L. Pruritus, Allergy and Autoimmunity: Paving the Way for an Integrated Understanding of Psychodermatological Diseases? Front Allergy. 2021, 2:688999. [CrossRef]

- Esen, M.; Demirbaş, A.; Diremsizoglu, E. Quality Of Life, Sleep, and Psychological Well-Being in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Patients Receiving Omalizumab: A Case-Control Study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025, 317(1):715. [CrossRef]

- Cetinkaya, PO.; Kurt, BO.; Aktaran, A.; Aksu, A.; Altunay, IK. Sleep Disturbance and Psychological Stress: Two Interconnected Conditions in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tıp Bul. 2025, 59(1):35-43. [CrossRef]

- Bešlić, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Vrtarić, A.; Bešlić, A.; Škrinjar, I.; Hanžek, M.; Crnković, D.; Artuković, M. Melatonin in Dermatologic Allergic Diseases and Other Skin Conditions: Current Trends and Reports. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shoshan M, Blinderman I, Raz A. Psychosocial Factors and Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Systematic Review. Allergy. 2013, 68(2):131-141. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly J.; Ridge K.; O'Donovan R.; Conlon N.; Dunne PJ. Psychosocial Factors and Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11(1):239. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, J.; Liu, R.; Zhu, L.; Peng, C. The Role of Crosstalk of Immune Cells in Pathogenesis of Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Front. Immunol. 2022, 31, 879754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P; Sharma, PK; Chitkara, A; Rani, S. To Evaluate the Role and Relevance of Cytokines IL-17, IL-18, IL-23 and TNF-α and Their Correlation With Disease Severity in Chronic Urticaria. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020, 11(4):594–597. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, K; Shibata, S; Yoshikawa, S; Karasuyama, H. Basophils and Their Effector Molecules in Allergic Disorders. Allergy. 2021, 76(6):1693–706. [CrossRef]

- He, L; Yi W; Huang, X; Long, H; Lu, Q. Chronic Urticaria: Advances in Understanding of the Disease and Clinical Management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021, 61(3):424–48. [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Arnau, AM; DeMontojoye, L; Asero, R; Cugno, M; Kulthanan, K; Yanase, Y; et al. The Pathogenesis of Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: The Role of Infiltrating Cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021, 9(6):2195–2208. [CrossRef]

- Voss, M; Kotrba, J; Gaffal, E; Katsoulis-Dimitriou, K; Dudeck, A. Mast Cells in the Skin: Defenders of Integrity or Offenders in Inflammation? Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(9):4589. [CrossRef]

- Falduto, GH; Pfeiffer, A; Luker, A; Metcalfe, DD; Olivera, A. Emerging Mechanisms Contributing to Mast Cell-Mediated Pathophysiology With Therapeutic Implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2021, 220:107718.

- Saini SS.; Asero R.; Cugno M.; Park HS.; Oliver ET. Pathogenesis of Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria with or Without Angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2025,S2213-2198(25)00715-9. [CrossRef]

- Lebedkina, M.; Kovalkova, E.; Andrenova, G.; Dushkin, A.; Chernov, A.; Nikitina, E.; Karaulov, A.; Lysenko, M.; Maurer, M.; Kocatürk, E.; et al. Chronic inducible urticaria - having more than one is common and clinically relevant. Front Immunol. 2025,16:1584771. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y.; Zhang H.; Du S.; Yan S.; Zeng J. Advanced Biomarkers: Therapeutic and Diagnostic Targets in Urticaria. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2021,182(10):917-931. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Guo, L.; Li, L.; Li, N.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y. Identification of Key Genes And Molecular Mechanisms of Chronic Urticaria Based on Bioinformatics. Skin Res Technol. 2024,30(4):e13624. [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Tian, Y.; Wei, Y.; Hao, F.; Ji, J. Key genes and immune infiltration in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a study of bioinformatics and systems biology. Front Immunol. 2023,14:1279139. [CrossRef]

- Kuna, M.; Štefanović, M.; Ladika Davidović, B.; Mandušić, N.; Birkić Belanović, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Chronic Urticaria Biomarkers IL-6, ESR and CRP in Correlation with Disease Severity and Patient Quality of Life—A Pilot Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deza, G.; Ricketti, P. A.; Giménez-Arnau, A. M.; Casale, T. B. Emerging Biomarkers and Therapeutic Pipelines for Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, K.; Zuberbier, T.; Maurer, M. Clinically Relevant Outcome Measures for Assessing Disease Activity, Disease Control, and Quality of Life Impairment in Patients with Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria and Recurrent Angioedema. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 15, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkhir, P.; André, F.; Church, M. K.; Maurer, M.; Metz, M. Potential Blood Biomarkers in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2017, 47 (1), 19–36.

- Kasperska-Zajac, A.; Grzanka, A.; Damasiewicz-Bodzek, A. IL-6 Trans-signaling in Patients with Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10 (12), e0145751.

- Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Su, J. Role of Stress in Skin Diseases: A Neuroendocrine-Immune Interaction View. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 116, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, J. J. Cutaneous Neuropeptides: The Missing Link between Psychological Stress and Chronic Inflammatory Skin Disease? Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2023, 315, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinou, G. N.; Konstantinou, G. N. Psychological Stress and Chronic Urticaria: A Neuro-immuno-cutaneous Crosstalk. A Systematic Review of the Existing Evidence. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, G. N.; Konstantinou, G. N. Psychiatric Comorbidity in Chronic Urticaria Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2019, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pondeljak, N.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Stress-Induced Interaction of Skin Immune Cells, Hormones, and Neurotransmitters. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, K.; Słodka, A.; Tarkowski, B.; Zalewska-Janowska, A. Neuro-Immuno-Psychological Aspects of Chronic Urticaria. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, K.; Groffik, A.; Church, M. K.; Hawro, T.; Krause, K.; Metz, M.; Martus, P.; Casale, T. B.; Staubach, P.; Maurer, M. Development and Validation of the Urticaria Control Test: A Patient-Reported Outcome Instrument for Assessing Urticaria Control. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1365–1372.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, A. Y.; Khan, G. K. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—A Simple Practical Measure for Routine Clinical Use. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1994, 19, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pondeljak, N.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Davidović, B. L.; Karlović, D.; Hanžek, M.; Neuberg, M. Serum Levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, Salivary Morning Cortisol and Intensity of Psychological Stress in Patients with Allergic Contact Hand Dermatitis and Healthy Subjects. Life 2025, 15, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P. D. The 10-Item Perceived Stress Scale as a Valid Measure of Stress Perception. Asia-Pac. Psychiatry 2021, 13, e12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazlić, H.; Brborović, O.; Vukušić Rukavina, T.; Fišter, K.; Milošević, M.; Mustajbegović, J. Karakteristike osoba sa opaženim stresom u hrvatskoj: Crohort istraživanje. Coll. Antropol. 2012, 36 (Suppl. 1), 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schut, C.; Magerl, M.; Hawro, T.; Kupfer, J.; Rose, M.; Gieler, U.; Maurer, M.; Peters, E. M. J. Disease Activity and Stress Are Linked in a Subpopulation of Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Patients. Allergy. 2020, 75, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeshma, J.; Mariyath, O. K. R.; Narayan, K. D.; Devi, K.; Ajithkumar, K. Quality of Life and Perceived Stress in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: Counting the Burden. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2024, 15, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, C. J.; Bansal, A. S. Stress, Pseudoallergens, Autoimmunity, Infection and Inflammation In Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2019, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elçin, A.; Ayla, G.; Tuba Saadet Deveci, B.; Özlem, G.; Murat, Ö.; Ahmet Selim, B.; Behçet, C. Stressful Life Events, Psychiatric Comorbidities and Serum Neuromediator Levels in Patients with Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Treated with Omalizumab. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr.) 2024, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Bae, Y. J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.C.; Lee, H.Y.; Ban, G.Y.; Shin, Y. S.; Park, H. S.; Kratzsch, J.; Ye, Y. M. Adaptation and Validation of the Korean Version of the Urticaria Control Test and Its Correlation With Salivary Cortisone. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2019, 11, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; Rajappa, M.; Chandrashekar, L.; Kattimani, S.; Archana, M.; Munisamy, M.; Revathy, G.; Thappa, D. M. Association Among Stress, Hypocortisolism, Systemic Inflammation, and Disease Severity in Chronic Urticaria. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016, 116, 344–348.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.; Zang, D.; Yi, J.; Dong, H.; Niu, Y.; Zhai, Q.; Teng, Y.; Bin, P.; Zhou, W.; Huang, X.; et al. Cytokine Expression in Trichloroethylene-Induced Hypersensitivity Dermatitis: An In Vivo And In Vitro Study. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 215, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Hou, G.; Li, D.; Yuan, T. F. A Possible Change Process of Inflammatory Cytokines in the Prolonged Chronic Stress and its Ultimate Implications for Health. Scientific World Journal. 2014, 2014, 780616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzanka, R.; Damasiewicz-Bodzek, A.; Kasperska-Zajac, A. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha and Fas/Fas Ligand Signaling Pathways in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2019, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Amirzargar, A. A.; Movahedi, M.; Aryan, Z.; Bidoki, A. Z.; Gharagozlou, M.; Aghamohammadi, A.; Nabavi, M.; Ahmadvand, A.; Behniafard, N.; et al. Interleukin-6 and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Gene Polymorphisms in Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr.). 2014, 42, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habal, F, Huang, V. Angioedema Associated with Crohn's Disease: Response to Biologics. World J Gastroenterol. 2012,18(34):4787-90. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J. M.; Fernandez, A. P.; Lang, D. M. Biologic Therapy in the Treatment of Chronic Skin Disorders. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 2017, 37, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaie, D.; Nabavi, M.; Arshi, S.; Gorjipour, H.; Darougar, S. The Relationship Between Serum Interleukin-6 Level and Chronic Urticaria. Immunoregulation. 2019, 2, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ograczyk-Piotrowska, A.; Gerlicz-Kowalczuk, Z.; Pietrzak, A.; Zalewska-Janowska, A. M. Stress, Itch And Quality Of Life in Chronic Urticaria Females. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2018, 35, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskeland, S.; Halvorsen, J. A.; Tanum, L. Antidepressants have Anti-inflammatory Effects that may be Relevant to Dermatology: A Systematic Review. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2017, 97, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tat, T. S. Higher Levels of Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Chronic Urticaria. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinou, GN.; Podder, I.; Konstantinou, G. Mental Health Interventions in Refractory Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Call to Expand Treatment Guidelines. Cureus. 2025, 17(3):e81443. [CrossRef]

- Grieco, T.; Porzia, A.; Paolino, G.; Chello, C.; Sernicola, A.; Faina, V.; Carnicelli, G.; Moliterni, E.; Mainiero, F. IFN-γ/IL-6 and Related Cytokines in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: Evaluation of Their Pathogenetic Role And Changes During Omalizumab Therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2020, 59(5):590-594. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).