1. Introduction

Sleep disturbances are among the most common and distressing symptoms of dementia, and have substantial implications for both individuals living with the condition and their caregivers [

1,

2]. In Alzheimer’s disease, poor sleep is associated with impaired clearance of amyloid-β, a neuropathological hallmark that accelerates disease progression [

3,

4]. Beyond biological mechanisms, sleep disruption contributes to fatigue, mood disturbance, and behavioural symptoms such as agitation and aggression [

5,

6,

7], all of which heighten caregiver burden [

8,

9]. Caregivers themselves frequently experience poor sleep due to both the nocturnal disruptions of the person with dementia and the psychological and physical strain of caregiving [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Consequently, sleep problems in dementia are best conceptualised as a dyadic phenomenon—where a partner or co-residing caregiver is present—because disturbances impact both the individual with dementia and the wellbeing of their caregiver.

Current responses to sleep disturbance in dementia remain largely medical and reactive, despite Cochrane reviews highlighting the weak evidence for medication and the need for safe, sustainable, non-drug alternatives (McCleery et al., 2020; McPhillips et al., 2020). Mind–body approaches such as mindfulness, breathing exercises, and Tai Chi show promising benefits for sleep, stress, and overall wellbeing in older adults with dementia [

14,

15,

16]. However, existing interventions rarely engage both the person with dementia and their caregiver concurrently, nor do they typically integrate multiple forms of support within a single programme.

Emerging evidence suggests that sleep disturbances and their consequences may be more pronounced among certain ethnic groups, particularly people from Black and South Asian communities. For example, studies show that non-Hispanic Black adults experience greater sleep discontinuity and poorer sleep quality than White adults, with associated impacts on memory performance [

17] and increased vulnerability during stressful periods such as COVID-19 [

18]. Research involving participants from South Asian and Black populations also reports shorter sleep duration and higher burdens of chronic conditions linked to poorer sleep [

19]. Additionally, ethnic differences in modifiable health risk factors may further contribute to disparities relevant to dementia risk (Mukadam et al., 2023). Yet little is known about how ethnically diverse communities perceive and manage sleep disturbance in dementia, and culturally tailored interventions remain scarce. In the UK, the number of individuals with dementia from minority ethnic backgrounds is predicted to increase substantially in the coming decades [

21]. However, these groups are less likely to access dementia services, often doing so only in later stages or during crises [

22]. Health inequalities—including stigma, structural inequities, and a lack of culturally appropriate care—further restrict access to timely and effective support [

23].

Addressing these challenges needs a clear, structured, and theory-based approach. Sleep interventions for people with dementia are naturally complicated. They often include several components—such as environmental modifications, daily activity scheduling, relaxation, and caregiver support strategies—that need to working together to be effective, may need to support both the person with dementia and their caregiver, and must still work for individuals who do not have a care partner. In addition, interventions must be sensitive and responsive to diverse cultural and community contexts. The updated Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework for complex interventions emphasises systematic, theory-informed development that considers mechanisms of change, implementation processes, and equity from the outset [

24]. However, existing caregiver sleep interventions remain small-scale, heterogeneous, and weakly theorised, highlighting the need for more structured designs [

25]. Similarly, reviews of dyadic interventions in dementia underscore the importance of articulating behaviour-change mechanisms and accounting for contextual variability [

26]. Behavioural science has begun to inform dementia sleep interventions, as exemplified by the DREAMS-START programme [

27], which combined psychoeducation, routine optimisation, light exposure, physical activity, and structured caregiver support while examining mechanisms of change. However, these approaches have not yet been culturally adapted to meet the needs of communities at higher risk, nor designed to benefit both people living with dementia and their caregivers at the same time.

Building on this progress, the present study integrates behaviour-change principles with culturally resonant, embodied practices—including mindfulness, breathwork, and gentle Tai Chi–based movement. Accordingly, the DREAM (Dyadic Resilience, Engagement, Awareness & Mind–body intervention) programme was developed using Intervention Mapping (IM; Stages 1–4) [

28,

29] and the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) and COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation → Behaviour) model [

30,

31] to ensure theoretical rigour, systematic development, and stakeholder relevance. This study aimed to co-develop and culturally ground the DREAM programme through collaboration with people living with mild dementia and their caregivers from White British, Caribbean, Chinese, and South Asian communities, alongside input from healthcare professionals. To our knowledge, this is the first dyadic, culturally adapted mind–body sleep intervention for people with dementia in the UK, addressing both clinical and cultural dimensions of sleep and wellbeing in dementia care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Participants

The study took place in a city in Southwest England and involved 12 dementia–caregiver dyads, drawn equally from four ethnic communities: White British (n=3), Caribbean (n=3), Chinese (n-3), and South Asian (n=3). The co-development process also included six Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) representatives and two Tai Chi and mindfulness practitioners with experience in culturally tailored practice. Within each community, we held two co-development consultation sessions followed by a pilot run of eight sessions of the co-designed DREAM programme, with both activities contributing directly to Intervention Mapping (IM) Stages 2–4. Through these sessions, contributors helped refine the programme’s content, delivery style, and cultural adaptations. Their involvement was essential to ensuring that the final intervention was both culturally relevant and practically feasible. Participants were identified and recruited through trusted local networks—including Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Sectors—to ensure meaningful representation across ethnic, linguistic, and socio-cultural backgrounds. This approach allowed a broad range of perspectives to inform the programme’s content, delivery, and acceptability, strengthening the credibility of the co-design process.

2.2. DREAM Development and Procedures (Structured by IM Stages)

2.2.1. Design Framework

IM provided a clear, structured framework for developing DREAM in a systematic and co-produced way. Using the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) and COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation → Behaviour) frameworks helped identify key barriers and facilitators and guided the selection of practical behaviour-change strategies. This process ensured that DREAM was theory-driven, culturally grounded, and shaped directly by stakeholder experience, in line with best practice for developing complex health interventions (Duncan et al., 2020; O’Cathain et al., 2019).

Table 1 summarises the key development tasks.

2.2.2. Stage 1: Needs Assessment

Guided by IM, Stage 1 was previously undertaken in an earlier phase of this research programme. The multi-source needs assessment identified priorities, contextual factors, and behavioural determinants for a dyadic mind–body intervention targeting sleep disturbances in dementia–caregiver dyads. A diverse working group—comprising dementia–caregiver dyads from White British, Caribbean, Chinese, and South Asian communities, alongside PPI contributors, mind–body practitioners, community leaders, and clinicians—collaboratively guided the process. Data from focus groups, stakeholder consultations, and a targeted literature review were integrated to refine intervention outcomes.

In that earlier phase, workshops and prioritisation exercises were conducted to identify and rank key outcome domains for the intervention. Participants independently rated the importance of potential targets, and group discussions were used to refine priorities for subsequent programme development. The BCW and COM-B framework were then applied to systematically identify behavioural determinants relevant to engagement with mind–body practices. Using structured prompts aligned with Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation domains, participants reported perceived barriers and facilitators to learning and sustaining sleep-related practices. These data were integrated with insights from focus groups and the targeted literature review to generate an initial problem analysis and needs statement. This process informed specification of the core outcomes and behavioural targets to be addressed in Stage 2 of programme development.

2.2.3. Stage 2: Programme Outcomes and Change Objectives

Stage 2 involved defining programme outcomes, specifying performance objectives, and developing matrices of change objectives to guide intervention design. Within each community, a new group of dementia–caregiver dyads, PPI representatives, mind–body practitioners, and community stakeholders took part in a structured workshop to review and expand upon the findings from Stage 1. Participants engaged in facilitated discussions to identify priority outcomes for improving sleep and wellbeing, after which the research team translated these priorities into performance objectives describing the behaviours required of people with dementia, caregivers, and facilitators. These draft objectives were iteratively refined to ensure cultural relevance and feasibility.

To identify determinants influencing these behaviours, data from Stage 1 and workshop activities were analysed using the COM-B model, with further categorisation informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF v2) [

34]. This process enabled systematic identification of Capability-, Opportunity- and Motivation-related barriers and facilitators. Performance objectives and corresponding determinants were then mapped onto intervention functions from the BCW and linked to candidate behaviour change techniques (BCTs). The resulting matrix of change objectives specified what needed to change, for whom, and through which mechanisms, forming the behavioural pathway guiding Stage 3 (see

Table 2).

2.2.4. Stage 3: Theory-Based Methods and Strategies

Stage 3 involved selecting BCTs and operationalising them into delivery strategies for the DREAM intervention (

Table 2). Candidate BCTs were identified through the BCW, BCT Taxonomy [

31,

35], the Theory and Techniques Tool [

36], and relevant dementia and mind–body literature. These were reviewed in another iterative workshop in each community with PPI contributors, caregivers, practitioners, and community stakeholders to determine theoretical relevance, cultural suitability, and practical feasibility.

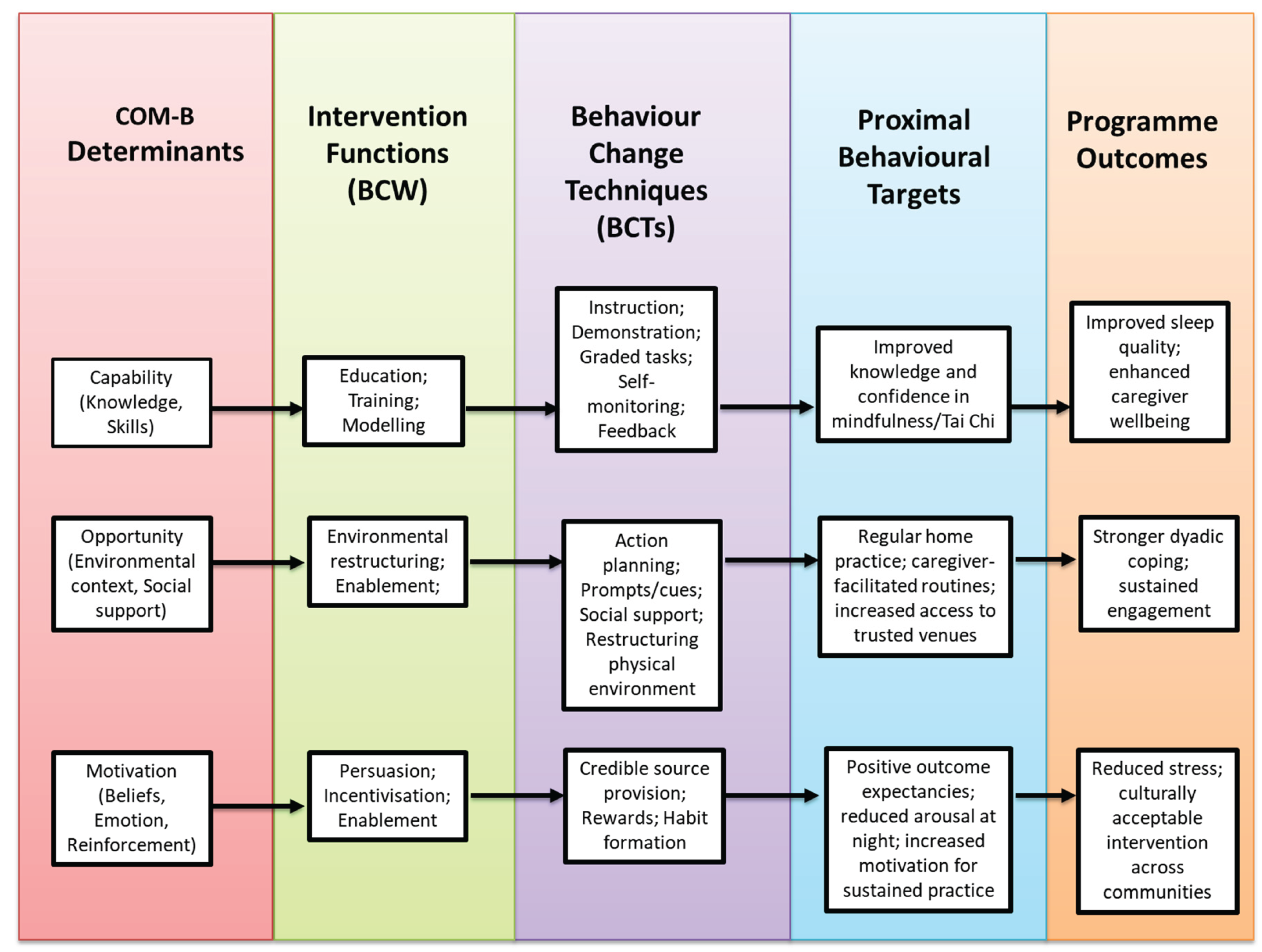

Selected BCTs were then translated into concrete delivery strategies through structured design activities. These activities focused on determining appropriate formats for guided practice, home-practice routines, visual prompts, caregiver-supported activities, and culturally adapted language and imagery. A facilitator manual was developed to support fidelity and consistency. Finally, all techniques were mapped to COM-B determinants and proximal behavioural targets and organised within a logic model of change. This mapping clarified the intended pathways from intervention functions to behavioural change and the overarching outcomes of improved sleep, caregiver wellbeing, and dyadic coping (see

Figure 1).

2.2.5. Stage 4: Programme Design and Materials

Stage 4 involved translating the selected theory-based methods and strategies into a fully specified, culturally adapted intervention. Through an iterative co-design process with PPI contributors, caregivers, practitioners, and community stakeholders, the research team developed an eight-week dyadic programme integrating brief mindfulness practices and gentle Tai Chi–based movements, supported by caregiver-facilitated home practice. Session content, language, visuals, and examples were adapted to ensure relevance and accessibility across White British, Caribbean, Chinese, and South Asian communities.

Detailed delivery procedures were established to guide weekly session structure, progression of skills, and home-practice planning. A comprehensive resource package—including a Facilitator Manual, session outlines, simplified practice guides, culturally adapted handouts, visual aids, video links, and home-practice logs—was created to support consistent delivery. All materials were iteratively reviewed by PPI contributors and community stakeholders for clarity, cultural appropriateness, and usability. Programme components were systematically checked against the logic model of change to ensure alignment with identified determinants, behaviour change techniques and intended outcomes. This process produced a theory-driven, culturally responsive intervention ready for pilot evaluation.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Faculty Research Ethics Committee at the University of the West of England on 11th February 2025 (UWE REC Ref No: 13515168), and all procedures adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from both individuals living with mild dementia and their caregivers prior to participation. All individuals with dementia were assessed as having the capacity to provide informed consent at the time of enrolment, in accordance with ethical guidance. Participants were given clear explanations of the study’s aims and procedures, along with opportunities to ask questions and withdraw at any time without consequence.

All data, including audio recordings and transcripts, were anonymised and securely stored on password-protected university servers accessible only to authorised members of the research team. Identifiable information was kept separate from research data, and pseudonyms have been used in all reports, publications, and dissemination materials to protect participant confidentiality. Data management adhered to institutional policies and research governance standards, with all audio recordings and transcripts retained for five years before secure destruction in line with data protection regulations. These procedures ensured that the study maintained full compliance with ethical principles for research involving vulnerable populations, promoting trust, respect, and participant safety across diverse cultural communities

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1: Needs Assessment

The focus groups, stakeholder consultations[

37] and targeted literature review [

16,

38]—reported previously—brought together dementia–caregiver dyads from White British, Caribbean, Chinese, and South Asian communities, alongside practitioners, clinicians, and community representatives. Across all groups, sleep disruption was consistently described as a strain on physical and emotional wellbeing, with clear implications for relationship dynamics and caregiving burden. Participants broadly viewed mind–body practices as acceptable and potentially beneficial but stressed the importance of approaches that were simple to follow, culturally relevant, and supportive of both members of the dyad, including through guided home practice.

The prioritisation and COM-B exercises further revealed shared concerns across communities, while also bringing important cultural nuances to light (see

Table 3). Although all groups endorsed sleep and dyadic engagement as central targets, communities varied in how strongly they emphasised cultural fit, familiarity with mind–body approaches, and the practical constraints that might shape engagement. For example, cultural acceptability was particularly prominent among Chinese and South Asian participants, reflected also in their reports of lower familiarity with mind–body practices and greater language-related challenges. Caribbean and White British groups highlighted fewer cultural or linguistic barriers but raised issues related to transport, motivation, and competing responsibilities. Motivation-related facilitators, such as the cultural meaning of practices and perceived dyadic benefit, were widely endorsed, yet the extent of scepticism or stigma differed notably between groups. Taken together, these findings illustrate both common behavioural determinants and specific cultural considerations that informed the development of programme goals and pathways for subsequent IM stages.

3.2. Stage 2: Programme Outcomes and Change Objectives

A further 12 dyads from the four ethnic communities participated in IM Stages 2–4, together with PPI representatives, mind–body practitioners, and community stakeholders. Together, these groups took part in a structured prioritisation process using facilitated discussions, ranking exercises, and iterative feedback rounds. Through this consensus-building process, stakeholders reviewed the needs assessment findings and collectively identified the three outcomes that the programme should focus on. The final outcomes—(i) improved sleep quality, (ii) enhanced caregiver wellbeing, and (iii) strengthened dyadic coping and engagement—were therefore co-agreed. Agreement was reached when at least 80% of participants across all groups ranked an outcome as essential or high priority. These outcomes were theorised by the research team and the PPI contributors to yield short-term benefits (e.g., reduced stress, increased participation) and longer-term benefits (e.g., improved quality of life and reduced caregiver burden).

Four performance objectives were identified through a structured co-production process. These objectives were developed during facilitated workshops in which participants reviewed the prioritised outcomes and then worked together—using brainstorming, discussion, and ranking exercises—to specify what behaviours would be required for the DREAM programme to achieve its aims. The four agreed performance objectives were: (1) establishing consistent dyadic bedtime routines; (2) integrating mindfulness or Tai Chi into daily life; (3) reducing night-time stress; and (4) maintaining caregiver-supported home practice. Workshops highlighted the need for simplified movements, stepwise guidance, and accessible materials. To understand what might help or hinder these behaviours, we explored determinants—factors that influence whether a behaviour can occur. These determinants were generated through participant discussions and then coded using the COM-B model and mapped to the TDF for behavioural precision: cognitive and physical limitations and limited familiarity (Capability); trusted venues, flexible scheduling, culturally relevant materials, and caregiver support (Opportunity); and perceived dyadic benefit, sleep-related goals, and cultural resonance (Motivation). Despite overall enthusiasm, stigma and scepticism emerged as remaining barriers—particularly among some participants from Chinese and South Asian communities who expressed uncertainty about discussing sleep problems openly due to cultural norms around privacy, reluctance to burden others, and discomfort talking about personal or family difficulties. These concerns influenced motivation, highlighting the need for sensitive communication and normalisation within programme delivery. Together, these defined the behavioural pathway guiding Stage 3.

3.3. Stage 3: Theory-Based Methods and Strategies

Stage 3 refined a structured suite of theory-driven BCTs guided by COM-B and IM. Core BCTs included action planning, habit formation, self-monitoring, prompts and cues, demonstration and modelling, graded practice, social support, credible source provision, and environmental restructuring, with cultural adaptations such as using metaphors and imagery relevant to Chinese and South Asian traditions. BCTs were operationalised through practical strategies: structured home-practice schedules, practice logs, guided group demonstrations, visual prompts, culturally resonant materials, and dyadic support activities. Environmental restructuring was achieved through delivery in trusted community venues. These settings were important not only for their accessibility but also because participants associated them with cultural safety and familiar, trusted people. This increased comfort and willingness to engage, highlighting the value of locating interventions within community-based, culturally relevant spaces for effective service delivery.

Each BCT was mapped to Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation determinants and aligned with proximal behavioural targets (e.g., routine building, arousal reduction, dyadic support) and the overarching outcomes of improved sleep, caregiver wellbeing, and dyadic coping. The resulting guiding principles emphasised dyadic involvement, clear outcome setting, motivation-building, structured action planning, self-monitoring, regular review, problem-solving, and progressive independence. This process clarified

how the intervention was expected to work and

why specific components were necessary. Importantly, these mapped components were then brought together into a logic model of change linking determinants, intervention functions, BCTs, and outcomes, as developed jointly by the research team and stakeholders (see

Figure 1).

3.4. Stage 4: Programme Design and Materials

Stage 4 resulted in the final specification of the DREAM intervention and the development of a comprehensive package of supporting resources. Building on the theoretical, behavioural, and cultural foundations established in earlier stages, this phase translated the identified methods and strategies into a fully developed, ready-to-deliver programme that was both theory-driven and community-informed.

The DREAM programme was structured as an eight-week dyadic course integrating brief mindfulness practices, and gentle Tai Chi–based movement, reinforced by caregiver-facilitated home practice. Weekly sessions were delivered in trusted community venues and tailored with culturally relevant language, imagery, and examples to ensure accessibility and resonance across White British, Caribbean, Chinese, and South Asian communities. Delivery of the intervention during this stage was undertaken solely by the first author who has over 20 years’ experience of delivering mindfulness meditation and Tai Chi . Each session followed a consistent format that combined check-in, guided practice, reflective discussion, and planning for home practice. The content progressively introduced mindfulness and Tai Chi elements designed to enhance awareness, calmness, and dyadic connection. This structured progression enabled participants to develop skills gradually, with each week reinforcing previous learning while introducing new practices to deepen self-awareness, balance, and relational attunement (see

Table 4 for the detailed weekly programme outline).

A comprehensive package of resources was produced to support the intervention. These included:

Facilitator Manual

Simplified stepwise mindfulness and Tai Chi guides

Picture guides, illustrated handouts and video links

Home practice logs

Feedback and outcome monitoring tools

These materials were made available to participants in both printed and digital formats, depending on individual preference and accessibility needs. To ensure inclusivity, all core resources—including handouts, instructions, and practice logs—were provided in English, Punjabi, Urdu, and Chinese, with video demonstrations recorded in multiple languages where possible.

All materials underwent multiple rounds of iterative review by PPI contributors and community stakeholders from White British, Caribbean, Chinese, and South Asian communities. Their feedback directly shaped the clarity, cultural appropriateness, and accessibility of each resource. For example:

Language and Tone: PPI reviewers identified terms that felt too clinical or unfamiliar; these were replaced with simpler, everyday language. Instructions were rewritten to be shorter, more direct, and more supportive in tone.

Cultural Framing: Contributors recommended using metaphors and imagery meaningful within their communities—for instance, linking slow breathing to “settling the heart” in Chinese contexts or emphasising “mutual care” and family interdependence in South Asian groups.

Movement Adaptations: Tai Chi movements were simplified further after reviewers noted physical limitations among elders, and culturally respectful seating arrangements were suggested for group sessions.

Translation Quality: Bilingual PPI contributors improved the accuracy and cultural nuance of corresponding translations, ensuring that mindfulness terms were familiar and appropriate for older adults.

Visual Materials: Chinese and South Asian groups suggested adding more diverse illustrations showing people who “look like us,” which was implemented across handouts and slides.

Programme refinement ensured all elements aligned with the logic model and directly addressed behavioural, social, and motivational determinants identified earlier—such as reducing cognitive load, building confidence with unfamiliar practices, and ensuring delivery settings felt culturally safe and trusted. The resulting DREAM intervention is theory-driven, culturally responsive, and ready for pilot evaluation and scaling.

4. Discussion

The DREAM programme was developed using a rigorous, theory-informed, and community co-design approach based on the IM framework. This systematic process integrated empirical evidence, behavioural theory, and extensive public engagement, resulting in an intervention that is evidence-informed, culturally responsive, and feasible for implementation within community settings. The co-development process engaged people living with dementia, their caregivers, mind–body practitioners, clinicians, and community representatives from four ethnic groups, ensuring that DREAM reflects the lived realities, preferences, and barriers of its intended users.

4.1. Relational Dimensions of Sleep in Dementia Care

The theoretical grounding of DREAM aligns with research highlighting the multifaceted and relational nature of sleep disturbance in dementia. Sleep disruption affects physical health, emotional regulation, cognition, and relationships, with recent studies showing dyadic consequences for wellbeing, emotional attunement, and relationship quality [

39]. Qualitative work similarly demonstrates how night-time disturbances contribute to cumulative strain within caregiving partnerships [

40]. Responding to this evidence, DREAM adopts a dyadic, non-pharmacological framework targeting sleep quality, caregiver wellbeing, and dyadic coping. The inclusion of cultural responsiveness further broadens its biopsychosocial scope. Stakeholders emphasised that mutual support, attunement, and shared meaning are central to effective dyadic interventions—consistent with evidence that dyadic engagement enhances the impact of mind–body approaches on sleep and psychological outcomes [

41].

4.2. Integrating Cultural Adaptation and Dyadic Mind–Body Practices

DREAM’s cultural adaptations—linguistically and visually tailored materials, culturally resonant metaphors, and delivery in trusted community venues—reflect evidence that adapted psychosocial interventions enhance accessibility and engagement among diverse groups [

42]. Following the structured guidance outlined by Ibekaku et al. (2025), cultural tailoring was undertaken through stakeholder consultation, iterative refinement, and pilot testing. Mind–body practices such as Tai Chi and mindfulness were incorporated based on evidence of feasibility and acceptability for dementia–caregiver dyads. Findings from the TACIT (TAi ChI for people with demenTia) programme demonstrate benefits of dyadic Tai Chi alongside challenges such as difficulty interpreting static images, suggesting that dynamic instructional materials may improve adherence [

44,

45]. Joint mindfulness training has also shown promise in enhancing emotional regulation and dyadic understanding [

46]. More recently, multimodal therapist-led sleep interventions integrating mind–body components have demonstrated feasibility and acceptability [

47]. Together, this evidence supports DREAM’s integrative and culturally responsive design.

4.3. Behavioural Objectives and Change Mechanisms

A central contribution of DREAM lies in its systematic specification of behavioural objectives using the COM-B model and TDF. These frameworks identified key determinants of engagement—including capability, opportunity, and motivation—and informed the development of behavioural performance objectives such as bedtime routines, integrating mindfulness or Tai Chi, reducing night-time stress, and sustaining home practice. The content of DREAM was deliberately designed to target known mechanisms underpinning sleep disturbance in dementia. Mindfulness practices were included to help reduce pre-sleep cognitive and emotional restlessness, supporting a calmer mental state conducive to sleep. Gentle Tai Chi movements were selected to promote physiological relaxation and autonomic regulation, helping the body transition into a state compatible with sleep onset. The dyadic component was intended to strengthen relational safety, reduce caregiver burden, and support shared routines—factors known to contribute to more stable and less disrupted sleep patterns within dementia-caregiver dyads. Objectives were mapped onto relevant BCTs (e.g., action planning, habit formation, self-monitoring, prompts, graded practice, social support) and corresponding intervention functions (education, training, modelling, environmental restructuring), aligning with best practice in intervention development [

48,

49]. This structured mapping enhances DREAM’s theoretical precision, replicability, and readiness for implementation [

50,

51], and aligns with emerging guidance from implementation science [

52,

53].

4.4. Practical Outputs and Translational Potential

The development process produced a ready-to-deliver intervention supported by a Facilitator Manual, participant guides, home-practice logs, feedback tools, and culturally adapted materials. The eight-week structure allows graded skill development, with seated options supporting accessibility. A clearly articulated logic model provides a transparent link between determinants, intervention functions, and outcomes, supporting replication and fidelity assessment. DREAM aligns with contemporary models of community-based dementia care and social prescribing, offering a low-cost, scalable non-pharmacological approach to improving sleep and wellbeing.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

Strengths include the systematic use of IM, integration of behavioural theory and cultural adaptation, and multi-stage co-design involving diverse stakeholders. However, DREAM has not yet undergone formal feasibility or efficacy testing, requiring future evaluation of acceptability, fidelity, and effectiveness. While development involved participants from White British, Caribbean, Chinese, and South Asian communities, the sample in a single city in UK limits generalisability, and further work is needed to ensure accessibility for broader and intersectional groups. Voluntary participation may also introduce selection bias toward individuals with greater interest in mind–body practices. Scaling up will require structured facilitator training and fidelity procedures. Despite these limitations, DREAM provides a robust foundation for feasibility and implementation research and represents a culturally attuned, theoretically grounded approach to sleep and wellbeing in dementia care.

4.6. Implications for Research and Practice

Future work will move DREAM to IM Stages 5 and 6, focusing on Implementation Planning and Evaluation. Stage 5 will develop a detailed implementation strategy addressing fidelity, sustainability, and integration into community and healthcare systems. This will include establishing a train-the-trainer model to equip local practitioners, community workers, and carers with the skills needed to deliver DREAM independently. By building local delivery capacity, this approach aims to enhance long-term sustainability, reduce reliance on specialist facilitators, and support the wider embedding of the programme within community organisations and routine care pathways. Stage 6 will employ a Hybrid Type 3 feasibility design [

54], assessing both implementation processes (e.g., acceptability, fidelity, cultural fit) and preliminary outcomes (e.g., sleep quality, caregiver wellbeing, dyadic engagement). In the longer term, DREAM’s framework may be applicable to other neurodegenerative or chronic conditions where sleep and caregiver wellbeing are interconnected, such as Parkinson’s disease or stroke.

5. Conclusions

The DREAM programme demonstrates the feasibility and value of using Intervention Mapping to co-develop a dyadic, culturally adapted mind–body intervention for older adults with dementia and their caregivers. Grounded in behavioural theory, cultural adaptation, and community partnership, DREAM represents a robust model for non-pharmacological sleep intervention that integrates the biological, psychological, social, and cultural dimensions of care. Future feasibility and pilot evaluations will determine its acceptability, practicality, and potential for scalable implementation across diverse community settings. If successful, DREAM has the potential to offer a safe, accessible, and empowering non-pharmacological pathway to improving sleep for people living with dementia—and, crucially, for those who care for them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and R.C.; methodology, S.C. and R.C.; formal analysis, S.C. and R.C.; investigation, S.C., R.H., and Z.H.; resources, R.H., and Z.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C. writing—review and editing, S.C. and R.C.; supervision, R.C.; project administration, S.C., R.H., and Z.H.; funding acquisition, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Capacity Fund (Type 2) of the NHS Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire Integrated Care Board (BNSSG ICB) (Ref: RCF 24/25-2SC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Faculty Research Ethics Committee at the University of the West of England (UWE REC Ref No: 13515168 and date of approval: on 11th February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to Dr James Selwood and Mr Shaun Popel from the Bristol Dementia Wellbeing Service for their invaluable support in facilitating participant recruitment and for their insightful guidance throughout the research process. Their contribution has been instrumental to the success of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCT |

Behaviour change techniques |

| BCW |

Behaviour Change Wheel |

| COM-B |

Capability, Opportunity, Motivation → Behaviour |

| DREAM |

Dyadic Resilience, Engagement, Awareness & Mind–body intervention |

| DREAM START |

Dementia Related Manual for Sleep; Strategies for Relatives |

| IM |

Intervention Mapping |

| MRC |

Medical Research Council |

| PPI |

Patient and Public Involvement |

| TACIT |

TAi ChI for people with demenTia |

| TDF |

Theoretical Domains Framework |

| VCSE |

Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise |

References

- Gao, C.; Chapagain, N.Y.; Scullin, M.K. Sleep Duration and Sleep Quality in Caregivers of Patients With Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019, 2, e199891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, T.; Fisher, E.; Webster, L.; Livingston, G.; Rapaport, P. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in people with dementia living in the community: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2023, 83, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, B.A.; Winer, J.R.; Jagust, W.J.; Walker, M.P. Sleep: A Novel Mechanistic Pathway, Biomarker, and Treatment Target in the Pathology of Alzheimer’s Disease? Trends in neurosciences (Regular ed). 2016, 39, 552–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghmousavi, S.; Eskian, M.; Rahmani, F.; Rezaei, N. The effect of insomnia on development of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapan, A.; Ristic, M.; Felsinger, R.; Waldhoer, T. Association of Self-Perceived Fatigue, Muscle Fatigue, and Sleep Disorders with Cognitive Function in Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2025, 26, 105477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.A.; Bower, J.L.; Cho, K.W.; Clementi, M.A.; Lau, S.; Oosterhoff, B.; et al. Sleep Loss and Emotion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Over 50 Years of Experimental Research. Psychol Bull. 2024, 150, 440–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chekani, F.; Fleming, S.P.; Mirchandani, K.; Goswami, S.; Zaki, S.; Sharma, M. Prevalence and Risk of Behavioral Symptoms among Patients with Insomnia and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Retrospective Database Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2023, 24, 1967–1973.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gonzalo, L.; García-Batalloso, I.; Márquez-González, M.; Cabrera, I.; Olazarán, J.; Losada-Baltar, A. The role of hyperarousal for understanding the associations between sleep problems and emotional symptoms in family caregivers of people with dementia. A network analysis approach. J Sleep Res. 2025, 34, e14310-n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benca, R.; Herring, W.J.; Khandker, R.; Qureshi, Z.P.; Galimberti, D. Burden of Insomnia and Sleep Disturbances and the Impact of Sleep Treatments in Patients with Probable or Possible Alzheimer’s Disease: A Structured Literature Review. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease 2022, 86, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, R.; Helm, A.; Ross, I.; Gander, P.; Breheny, M. “I think I could have coped if I was sleeping better”: Sleep across the trajectory of caring for a family member with dementia. Dementia (London) 2023, 22, 1038–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gonzalo, L.; Vara-García, C.; Romero-Moreno, R.; Márquez-González, M.; Olazarán, J.; von Känel, R.; et al. An integrated model of psychosocial correlates of insomnia severity in family caregivers of people with dementia. Aging Ment Health 2024, 28, 969–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.J.; Kim, J.H. Family Caregivers of People with Dementia Have Poor Sleep Quality: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 13079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Aranda, M.P.; Lloyd, D.A. Association between Role Overload and Sleep Disturbance among Dementia Caregivers: The Impact of Social Support and Social Engagement. J Aging Health 2020, 32, 1345–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, C.; Fan, X.; Shirai, K.; Dong, J.Y. Mind–body therapies for older adults with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022, 13, 881–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhang, M.; Miranda-Castillo, C.; Rubio, M.; Furtado, G. Impact of mind-body interventions in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 643–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.H.W.; Cheston, R.; Steward-Anderson, C.; Yu, C.H.; Dodd, E.; Coulthard, E. Mindfulness meditation for sleep disturbances among individuals with cognitive impairment: A scoping review. Healthcare 2025, 3, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokett, E.; Duarte, A. Age and Race-Related Differences in Sleep Discontinuity Linked to Associative Memory Performance and Its Neural Underpinnings. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019, 13, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hokett, E.; Arunmozhi, A.; Campbell, J.; Duarte, A. Factors that protect against poor sleep quality in an adult lifespan sample of non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White adults during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 949364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Hall, K.A.; Reynolds, A.; Palmer, L.J.; Mukherjee, S. The Relationship of Sleep Duration with Ethnicity and Chronic Disease in a Canadian General Population Cohort. Nat Sci Sleep. 2020, 12, 239–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukadam, N.; Marston, L.; Lewis, G.; Mathur, R.; Lowther, E.; Rait, G.; et al. South Asian, Black and White ethnicity and the effect of potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia: A study in English electronic health records. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0289893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- All-Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia. Dementia does not Discriminate: The experiences of Black, Asian and ethnic minority communities. 2013. Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/2013-appg-report (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Dodd, E.; Pracownik, R.; Popel, S.; Collings, S.; Emmens, T.; Cheston, R. Dementia services for people from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic and White-British communities: Does a primary care based model contribute to equality in service provision? Health Soc Care Community. 2022, 30, 622–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, C.R.; van den Heuvel, E.; Pentecost, C.; Quinn, C.; Charlwood, C.; Clare, L. Understanding dementia in minority ethnic communities: The perspectives of key stakeholders interviewed as part of the IDEAL programme. Dementia (London) 2024, 23, 1172–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ (Online) 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatiello, G.A.; Martin, R.; Kraus, N.; Gutierrez, A.; Cusick, R.; Hickman, R.L. Sleep Interventions for Informal Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: A Systematic Review. West J Nurs Res. 2022, 44, 886–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van’t Leven, N.; Prick, A.E.J.C.; Groenewoud, J.G.; Roelofs, P.D.D.M.; de Lange, J.; Pot, A.M. Dyadic interventions for community-dwelling people with dementia and their family caregivers: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 1581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, P.; Amador, S.; Adeleke, M.O.; Barber, J.A.; Banerjee, S.; Charlesworth, G.; et al. Clinical effectiveness of DREAMS START (Dementia Related Manual for Sleep; Strategies for Relatives) versus usual care for people with dementia and their carers: a single-masked, phase 3, parallel-arm, superiority randomised controlled trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024, 5, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew Eldredge, L.K. Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. Fourth edition. San Francisco, CA: Wiley; 2016. (Jossey-Bass Public Health).

- Fernandez, M.E.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Markham, C.M.; Kok, G. Intervention Mapping: Theory- and Evidence-Based Health Promotion Program Planning: Perspective and Examples. Front Public Health 2019, 7, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel : a guide to designing interventions. Sutton: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; et al. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Annals of behavioral medicine 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O”Cathain, A.; Croot, L.; Duncan, E.; Rousseau, N.; Sworn, K.; Turner, K.M.; et al. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e029954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, E.; O’Cathain, A.; Rousseau, N.; Croot, L.; Sworn, K.; Turner, K.M.; et al. Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): an evidence-based consensus study. BMJ Open. 2020, 10, e033516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cane, J.; O’Connor, D.; Michie, S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science 2012, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Michie, S. A Taxonomy of Behavior Change Techniques Used in Interventions. Health psychology 2008, 27, 379–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.; Carey, R.N.; Connell Bohlen, L.E.; Johnston, D.W.; Rothman, A.J.; de Bruin, M.; et al. Development of an online tool for linking behavior change techniques and mechanisms of action based on triangulation of findings from literature synthesis and expert consensus. Transl Behav Med. 2021, 11, 1049–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.W.; Steward-Anderson, C.; Cheston, R. Listening to voices across cultures: Non-pharmacological approaches to coping with sleep problems in dementia among ethnically diverse older adults in the UK. BMC Complement Med Ther 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.H.W.; Tsang, H.W.H. The beneficial effects of Qigong on elderly depression. International Review of Neurobiology 2019, 147, 155–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marques, M.J.; Woods, B.; Jelley, H.; Kerpershoek, L.; Hopper, L.; Irving, K.; et al. Addressing relationship quality of people with dementia and their family carers: which profiles require most support? Front Psychiatry. 2024, 15, 1394665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, C.A.M.; Huisman, E.R.C.M.; Brankaert, R.G.A.; Kort, H.S.M. Sleep at home for older persons with dementia and their caregivers: a qualitative study of their experiences and challenges. Eur J Ageing [Internet] 2025, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, E.S.; Bitane, R.M.; Schoones, J.W.; Achterberg, W.P.; Smaling, H.J.A. Mind-body practices for people living with dementia and their family carers: a systematic review. J Complement Integr Med. 2025, 22, 15–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, S.; Laver, K.; Jeon, Y.H.; Radford, K.; Low, L.F. Frameworks for cultural adaptation of psychosocial interventions: A systematic review with narrative synthesis. Dementia (London) 2023, 22, 1921–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibekaku, M.C.; Weeks, L.E.; Ghanouni, P.; Adebusoye, L.; McArthur, C. Cultural Adaptations of Evidence-Based Interventions in Dementia Care: A Critical Review of Literature. Journal of ageing and longevity 2025, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrado-Martín, Y.; Heward, M.; Polman, R.; Nyman, S.R. People living with dementia and their family carers’ adherence to home-based Tai Chi practice. Dementia (London) 2021, 20, 1586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, S.R.; Hayward, C.; Ingram, W.; Thomas, P.; Thomas, S.; Vassallo, M.; et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of tai chi alongside usual care with usual care alone on the postural balance of community-dwelling people with dementia: protocol for the TACIT trial (TAi ChI for people with demenTia). BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, L.; Warmenhoven, F.; Stiekema, A.P.M.; van Oorsouw, K.; van Os, J.; de Vugt, M.; et al. Mindfulness-Based Intervention for People With Dementia and Their Partners: Results of a Mixed-Methods Study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Varma, P.; Brown, A.; Bei, B.; Gibson, R.; Valenta, T.; et al. Multi-modal sleep intervention for community-dwelling people living with dementia and primary caregiver dyads with sleep disturbance: protocol of a single-arm feasibility trial. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mather, M.; Pettigrew, L.M.; Navaratnam, S. Barriers and facilitators to clinical behaviour change by primary care practitioners: a theory-informed systematic review of reviews using the Theoretical Domains Framework and Behaviour Change Wheel. Syst Rev. 2022, 11, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisavadia, K.; Edwards, R.T.; Davies, C.T.; Gould, A.; Parkinson, J. Preventative behavioural interventions that reduce health inequities: a systematic review using the theoretical domains framework. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, O.S.; Dowling, N.L.; Brown, C.; Robinson, T.; Johnson, A.M.; Ng, C.H.; et al. Using the Theoretical Domains Framework to Inform the Implementation of Therapeutic Virtual Reality into Mental Healthcare. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 2023, 50, 237–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meloncelli, N.; O’Connor, H.; de Jersey, S.; Rushton, A.; Pateman, K.; Gallaher, S.; et al. Designing a behaviour change intervention using COM-B and the Behaviour Change Wheel: Co-designing the Healthy Gut Diet for preventing gestational diabetes. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2024, 37, 1391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommerskirch-Manietta, M.; Manietta, C.; Purwins, D.; Braunwarth, J.I.; Quasdorf, T.; Roes, M. Mapping implementation strategies of evidence-based interventions for three preselected phenomena in people with dementia—a scoping review. Implement Sci Commun. 2023, 4, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, N.; Evans, S.; Russell, C.; Brooker, D. Development and Implementation of a Novel Approach to Scaling the Meeting Centre Intervention for People Living with Dementia and Their Unpaid Carers, Using an Adapted Version of the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist. Behavioral Sciences 2025, 15, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, M.A.; Murphy, L.D.; Sherwin, E.B.; Shade, S.B. Practical application of hybrid effectiveness–implementation studies for intervention research. Int J Epidemiol [Internet] 2025, 54, dyaf039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).