Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Problem Statement & Objecctives

3.1. Problem Statement

3.2. Objectives of the Study

- To create an effective preprocessing and feature extraction process that transforms raw Twitter text into meaningful numerical data while retaining sentiment information.

- To apply the Egret Swarm Optimization Algorithm (ESOA) for selecting relevant and non-redundant features from high-dimensional TF-IDF representations, thereby reducing computational complexity and enhancing classification accuracy.

- To build a sentiment classification model utilizing a Multi-Head Attention Mechanism (MHAM) that captures diverse semantic patterns and improves the contextual understanding of short Twitter messages.

- To optimize the hyperparameters of the deep learning model using Dwarf Mongoose Optimization (DMO) in order to improve training stability and overall performance.

- To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed framework using the Sentiment140 dataset and compare its performance with existing sentiment analysis approaches based on standard evaluation metrics.

4. Proposed System

4.1. Dataset Description for Sentiment140

- Tweet polarity

- Tweet ID

- Date

- Query

- Username

- Tweet text

| Tweet ID | Tweet Text | Polarity |

|---|---|---|

| 1467810672 | feels cheated out of the ability to text Facebook status updates | 0 |

| 1467810917 | @Kenichan Numerous times, I dove for the ball | 0 |

| 1467824967 | No jobs = no income. How the hell is the minimum wage | 0 |

| 2065732947 | @KateHope thanks for having my back Haha | 4 |

| 2065733289 | Finally home and getting stuff done before an awesome birthday dinner... | 4 |

| 2065782488 | @DerrenLitten Oh, fantastic, I checked it out while napping | 4 |

4.2. Tweets Pre-Processing

- First, we split the tweets into individual words, making sure to remove extra spaces and punctuation.

- Next, we take out any numbers since they don’t help in determining the sentiment.

- We also remove common words like ’a’, ’the’, ’to’, and ’at’ because they don’t carry much meaning in this context.

- Then, we get rid of punctuation marks that don’t add any real meaning to the text.

- After that, we use a process called stemming, which reduces words to their basic form using the Porter stemming method.

- We also pay special attention to words like ’not’, ’never’, and ’do not’, as they can change the meaning and sentiment of a sentence.

- We use a part-of-speech tagging tool called Apache OpenNLP to identify and keep words that are important for sentiment, especially adjectives.

- Finally, we remove mentions of users, URLs, and retweet symbols, but we keep hashtags by removing the ’#’ symbol so the actual words are still useful.

4.2.1. SentiWordNet-Based Polarity Computation

- P be the set of positive opinion words,

- N be the set of negative opinion words,

- be the positivity score of the word,

- be the negativity score of the word.

4.3. Feature Extraction Using Term Weighting TF-IDF

4.4. Feature Selection Algorithm: Egret Swarm Optimization Algorithm (ESOA)

- Sit-and-Wait Strategy

- Aggressive Strategy

- Discriminant Condition

- Egret A, which uses a method similar to finding the best path

- Egret B, which randomly explores different areas

- Egret C, which helps bring the group together to focus on the best solution

4.4.1. Sit & Wait Strategy

4.4.2. Aggressive Strategy

4.4.3. Discriminant Condition

4.4.4. ESOA Pseudocode

| Algorithm 1 Egret Swarm Optimization Algorithm (ESOA) |

|

4.4.5. Computational Complexity

4.5. Classification Using Deep Learning Model

4.5.1. Seq2Seq Model and Attention Mechanism

4.5.2. Multi-Head Attention Mechanism

4.5.3. Penalty Term

4.5.4. Hyperparameter Optimization

4.5.5. Dwarf Mongoose Optimization (DMO) Procedure

Results & Discussion

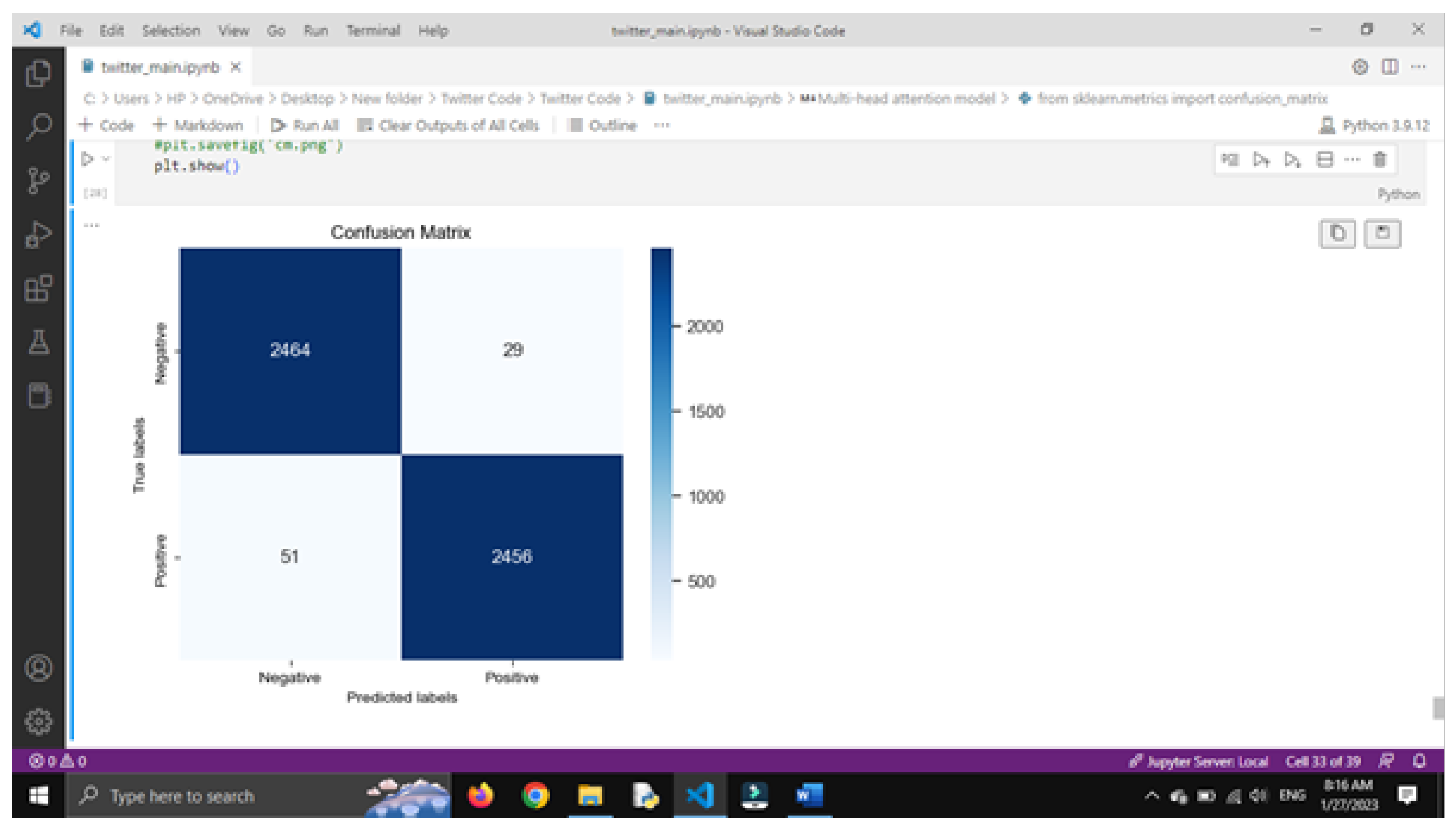

Confusion Matrix

- True Positive (TP): when the model correctly identifies something as positive.

- False Positive (FP): when the model wrongly says something is positive.

- True Negative (TN): when the model correctly identifies something as negative.

- False Negative (FN): when the model wrongly says something is negative.

| Actual / Predicted | Predicted Positive | Predicted Negative |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Positive | True Positive (TP) | False Negative (FN) |

| Actual Negative | False Positive (FP) | True Negative (TN) |

Basic Measures Derived from the Confusion Matrix

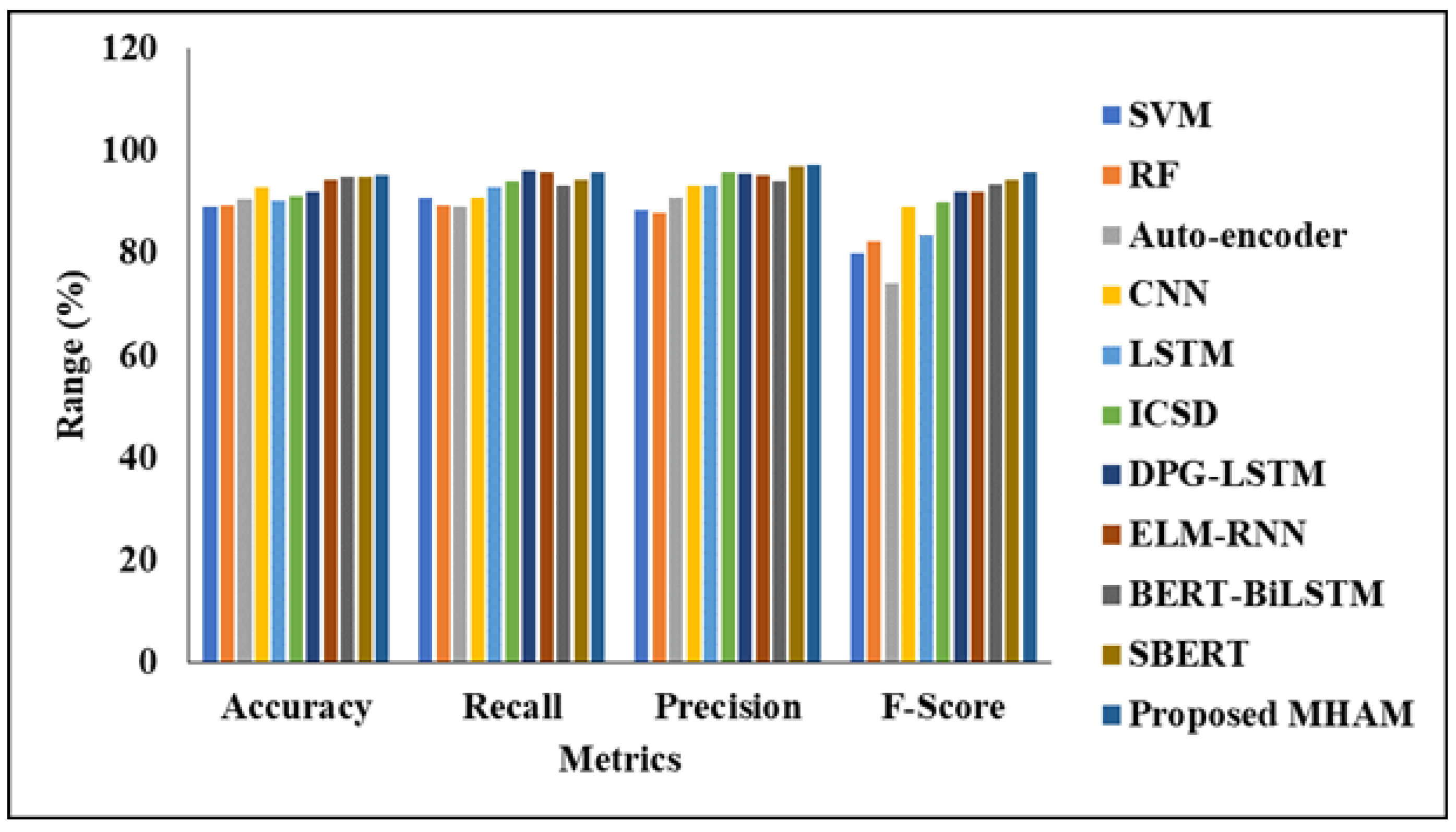

4.6. Performance Analysis of the Proposed Model Without Feature Selection

| Methodology | Accuracy (%) | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | F-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 89.02 | 90.91 | 88.34 | 79.82 |

| RF | 89.27 | 89.27 | 87.72 | 82.20 |

| Auto-encoder | 90.38 | 88.90 | 90.86 | 74.02 |

| CNN | 92.82 | 90.67 | 93.09 | 88.88 |

| LSTM | 90.21 | 92.91 | 93.20 | 83.49 |

| ICSD | 91.20 | 94.04 | 95.90 | 89.90 |

| DPG-LSTM | 92.03 | 95.92 | 95.55 | 91.91 |

| ELM-RNN | 94.44 | 95.64 | 95.30 | 92.04 |

| BERT-BiLSTM | 94.80 | 93.22 | 94.02 | 93.30 |

| SBERT | 94.92 | 94.30 | 96.90 | 94.43 |

| Proposed MHAM | 95.20 | 95.78 | 97.32 | 95.65 |

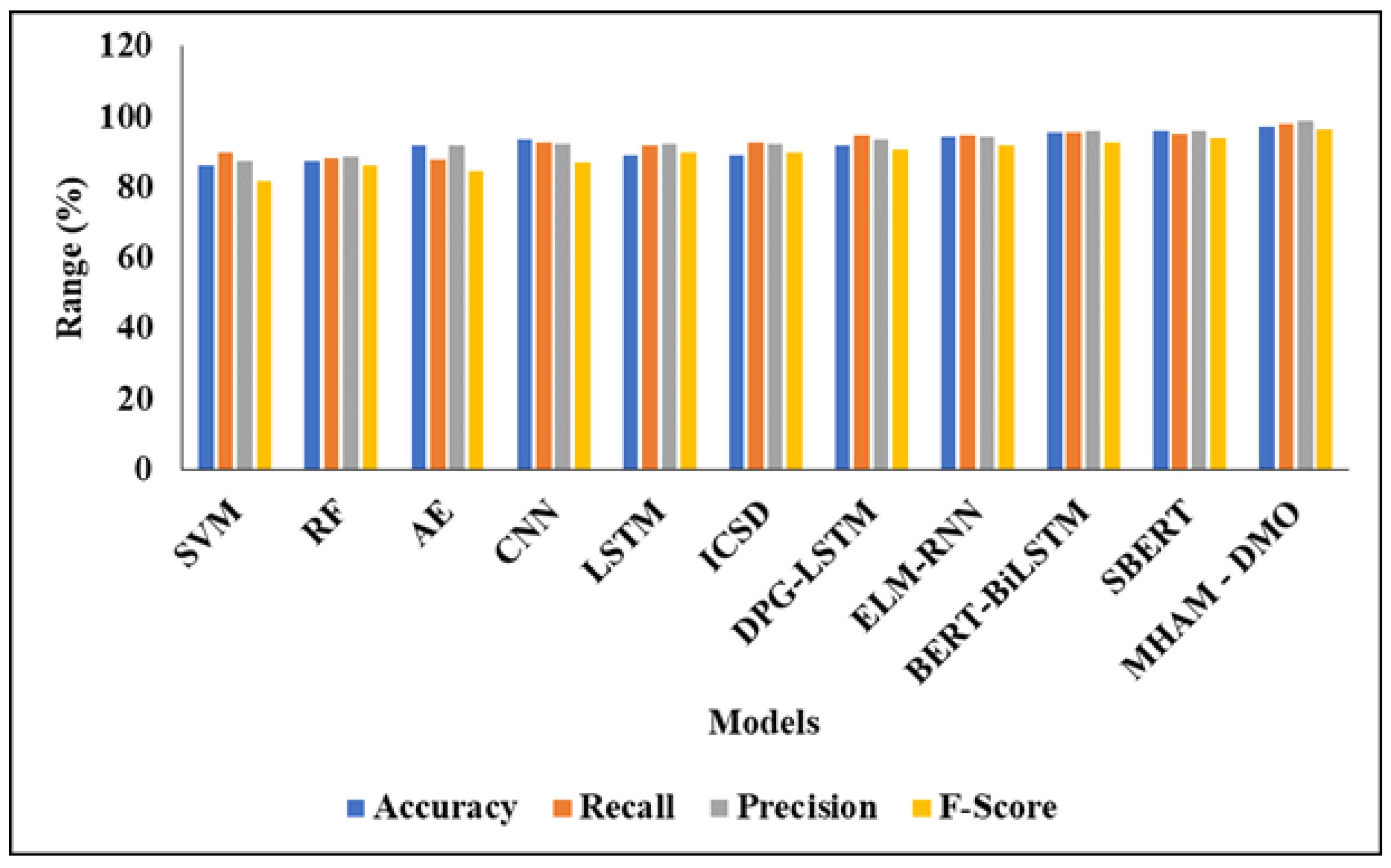

4.7. Performance Analysis of the Proposed Model with Feature Selection

| Methodology | Accuracy (%) | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | F-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 86.12 | 89.94 | 87.38 | 81.85 |

| RF | 87.29 | 88.28 | 88.78 | 86.27 |

| Auto-encoder | 91.88 | 87.95 | 91.87 | 84.42 |

| CNN | 93.42 | 92.68 | 92.12 | 86.89 |

| LSTM | 88.93 | 91.95 | 92.23 | 89.99 |

| ICSD | 89.23 | 92.72 | 92.45 | 89.95 |

| DPG-LSTM | 91.90 | 94.78 | 93.60 | 90.87 |

| ELM-RNN | 94.45 | 94.82 | 94.15 | 91.97 |

| BERT-BiLSTM | 95.46 | 95.55 | 95.80 | 92.54 |

| SBERT | 95.88 | 95.27 | 95.92 | 93.80 |

| Proposed MHAM-DMO | 97.28 | 97.98 | 98.77 | 96.29 |

5. Conclusion

References

- Carvalho, J.; Plastino, A. On the evaluation and combination of state-of-the-art features in Twitter sentiment analysis. Artificial Intelligence Review 2021, 54, 1887–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasthuri, S.; Jebaseeli, N. An Artificial Bee Colony and Pigeon Inspired Optimization Hybrid Feature Selection Algorithm for Twitter Sentiment Analysis. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 2020, 17(12), 5378–5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manguri, K.H.; Ramadhan, R.N.; Amin, P.R.M. Twitter sentiment analysis on worldwide COVID-19 outbreaks. Kurdistan Journal of Applied Research 2020, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Jaiswal, A. Systematic literature review of sentiment analysis on Twitter using soft computing techniques. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 2020, 32(1), e5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasthuri, S.; Jebaseeli, N. Review Analysis of Twitter Sentimental Data. Bioscience Biotechnology Research Communications 2020, 13(6), 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Pota, M.; Ventura, M.; Catelli, R.; Esposito, M. An effective BERT-based pipeline for Twitter sentiment analysis: A case study in Italian. Sensors 2021, 21(1), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasthuri, S.; Jebaseeli, N. A Robust Data Classification in Online Social Networks through Automatically Mining Query Facts. International Journal of Scientific Research in Computer Science Applications and Management Studies 2018, 7(4). [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P.; Pandya, S. A review on sentiment analysis methodologies, practices and applications. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research 2020, 9(2), 601–609. [Google Scholar]

- Naseem, U.; Razzak, I.; Musial, K.; Imran, M. Transformer based deep intelligent contextual embedding for twitter sentiment analysis. Future Generation Computer Systems 2020, 113, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasthuri, S.; Jebaseeli, N. An efficient Decision Tree Algorithm for analyzing the Twitter Sentiment Analysis. Journal of Critical Reviews 2020, 7(4), 1010–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Neogi, A.S.; Garg, K.A.; Mishra, R.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Sentiment analysis and classification of Indian farmers’ protest using Twitter data. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 2021, 1(2), 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruz, G.A.; Henríquez, P.A.; Mascareño, A. Sentiment analysis of Twitter data during critical events through Bayesian networks classifiers. Future Generation Computer Systems 2020, 106, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasthuri, S.; Jebaseeli, N. Social Network Analysis in Data Processing. Adalya Journal 2020, 9(2), 260–263. [Google Scholar]

- Nagamanjula, R.; Pethalakshmi, A. A novel framework based on bi-objective optimization and LAN2FIS for Twitter sentiment analysis. Social Network Analysis and Mining 2020, 10(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouza, N.; Akli-Astouati, K.; Ibrahim, R. TwitterBERT: Framework for Twitter sentiment analysis based on pre-trained language model representations. In Emerging Trends in Intelligent Computing and Informatics; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 428–437. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, G.; Sharma, A. A deep learning-based model using hybrid feature extraction approach for consumer sentiment analysis. Journal of Big Data 2023, 10(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, M.M.; Duraisamy, B.; Vankara, J. Independent component support vector regressive deep learning for sentiment classification. Measurement: Sensors 2023, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Shao, J.; Hussain, M.J.; Hao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L. DPG-LSTM: An Enhanced LSTM Framework for Sentiment Analysis in Social Media Text. Applied Sciences 2023, 13(1), 354. [Google Scholar]

- Albahli, S.; Irtaza, A.; Nazir, T.; Mehmood, A.; Alkhalifah, A.; Albattah, W. A Machine Learning Method for Prediction of Stock Market Using Real-Time Twitter Data. Electronics 2022, 11(20), 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfagergish, S.G.; Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė, J.; Damaševičius, R. Zero-shot emotion detection for semi-supervised sentiment analysis. Applied Sciences 2022, 12(17), 8662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhade, M.; Rao, A.C.S. Opinion analysis during COVID-19 using BERT-BiLSTM ensemble. Scientific Reports 2022, 12(1), 17095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Ramanna, S.; Kotecha, K.; Walambe, R. Short Text Classification with Tolerance-Based Soft Computing Method. Algorithms 2022, 15(8), 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.A.; Marium, S.M.; Begum, S.A.; Dipa, N.S. Sentiment analysis using text and emoticon. ICT Express 2020, 6(4), 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachman, F.H. Twitter sentiment analysis of COVID-19 using TF-IDF and logistic regression. Proc. 6th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), 2020; IEEE; pp. 238–242. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).