Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Case Selection and Tissue Processing

2.3. RNA Extraction and Nucleic Acid Quantification

2.4. One-Step RT-qPCR Workflow

2.4.1. Input Optimization

2.4.2. Cycling Conditions and Data Acquisition

2.4.3. Run Controls and Acceptance Criteria

2.5. Primer Design, Procurement, and Assay Validation

2.6. Reference Gene Strategy and Stability Assessment

2.7. Quantification and Data Processing

2.8. Replicates and Quality Criteria

2.9. Statistics

2.10. Reporting Standards

3. Results

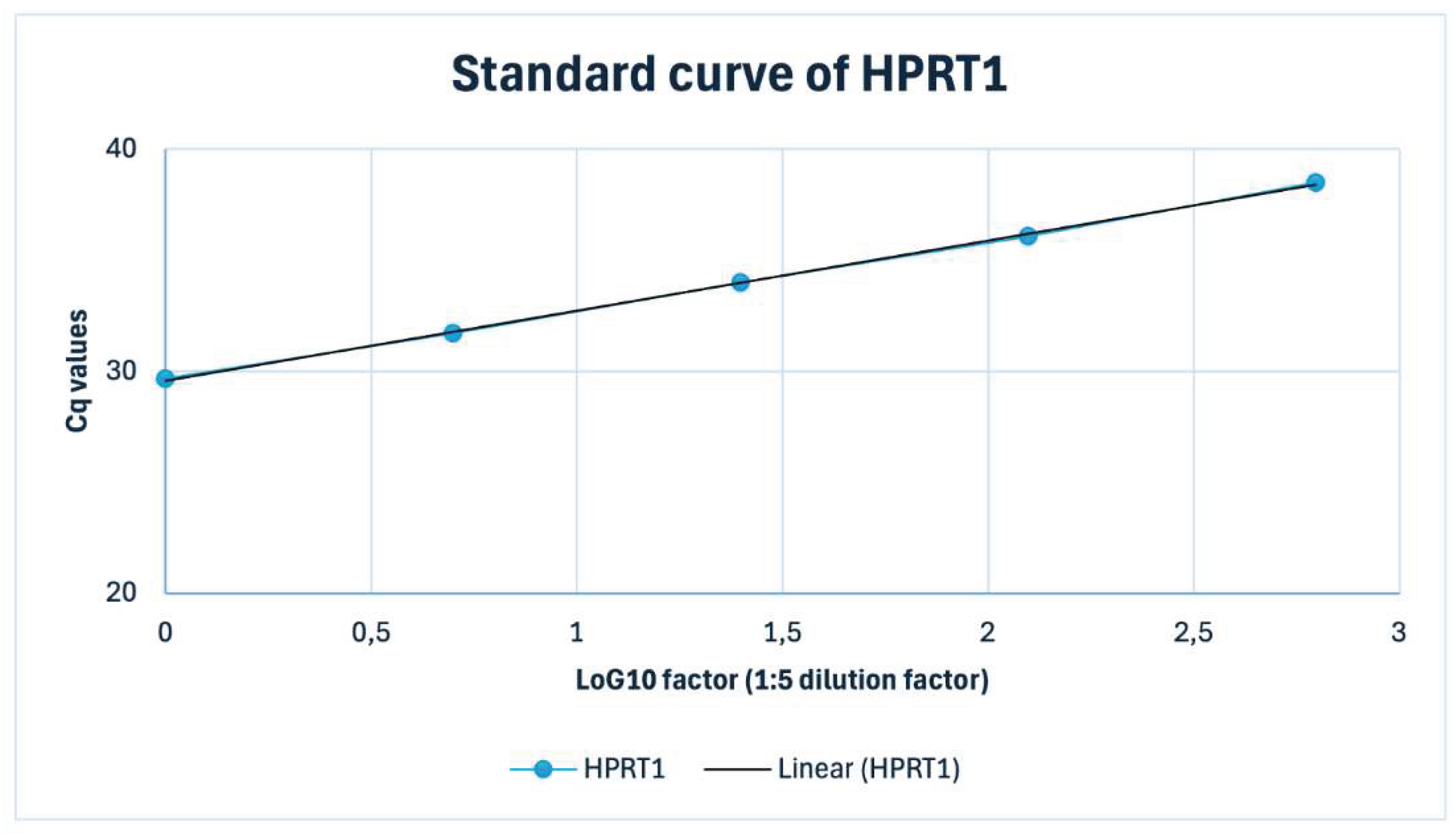

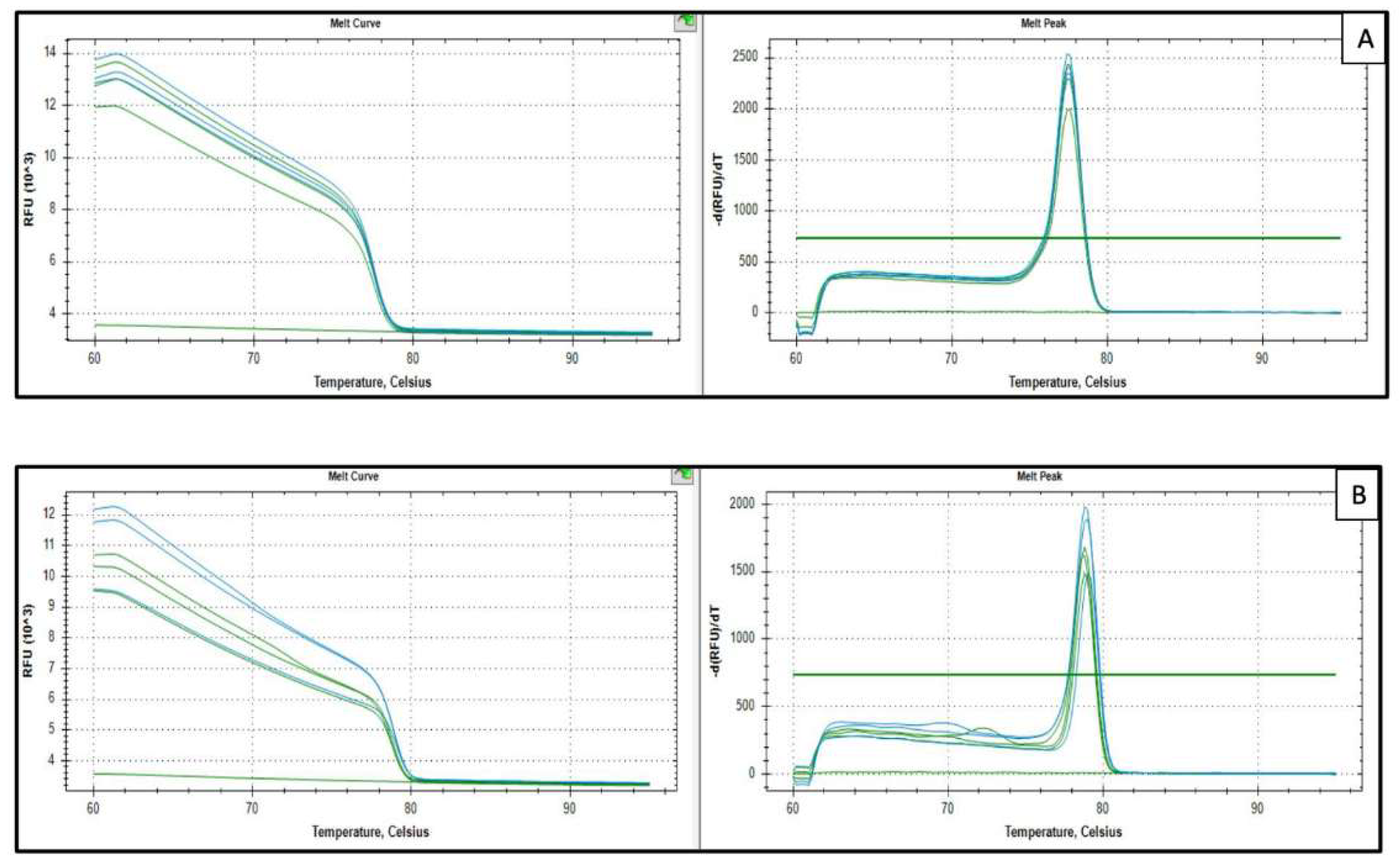

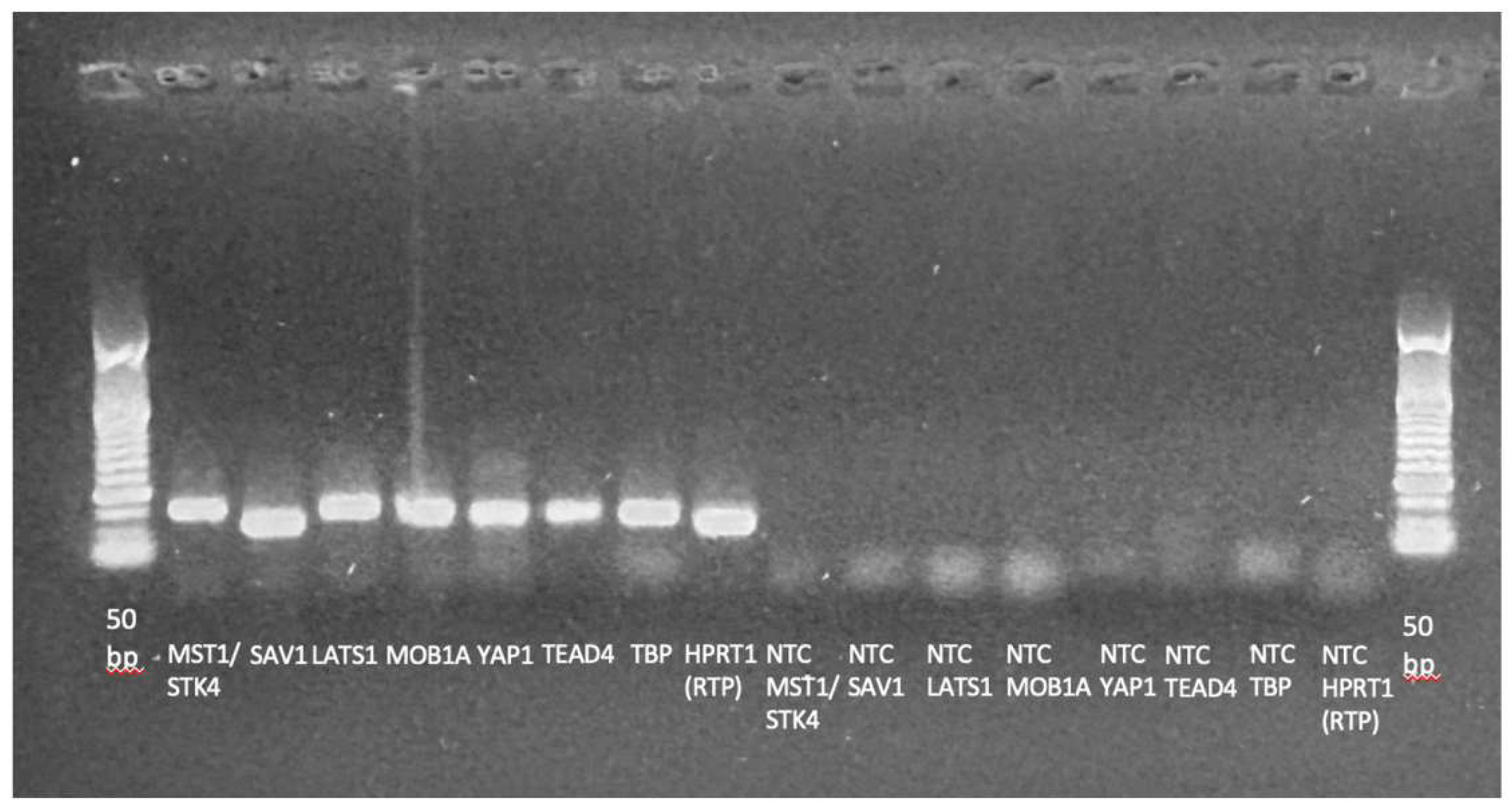

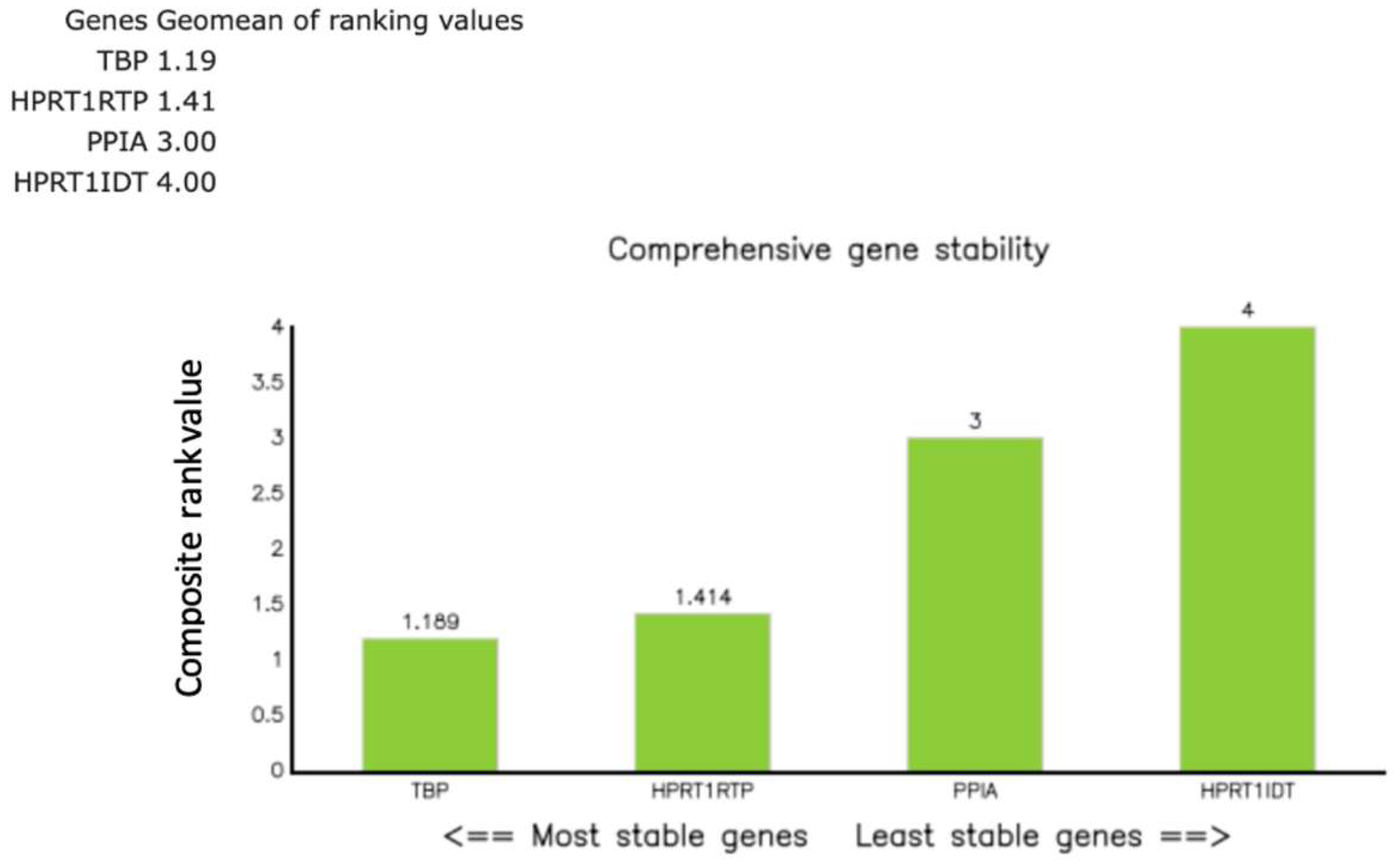

3.1. qPCR Assay Performance and Normalization Strategy

3.2. Relative Expression of Hippo Pathway Genes

3.2.1. Relative Expression of MST1 (STK4)

3.2.2. Relative Expression of SAV1

3.2.3. Relative Expression of LATS1

3.2.4. Relative Expression of MOB1A

3.2.5. Relative Expression of YAP1

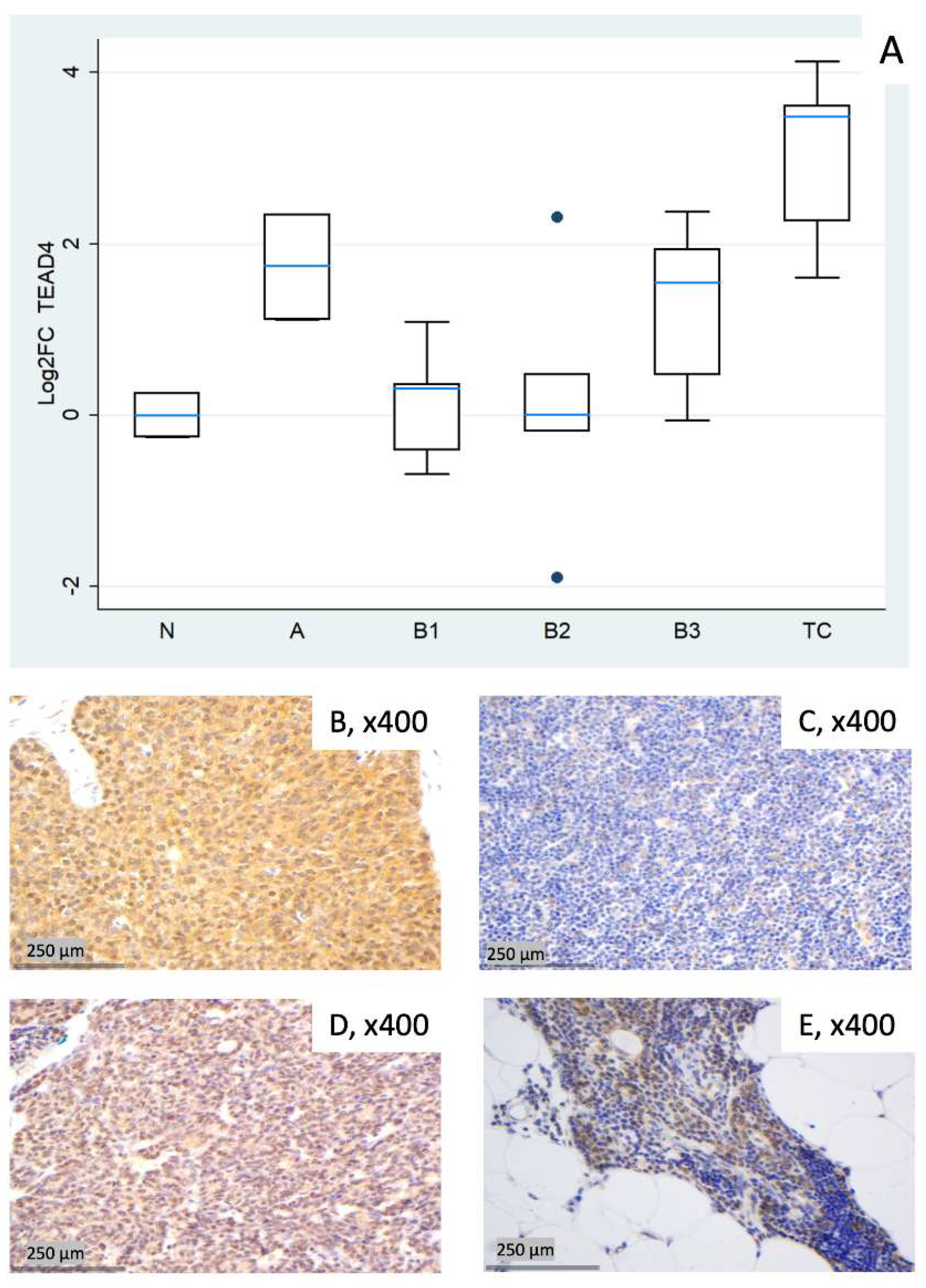

3.2.6. Relative Expression of TEAD4

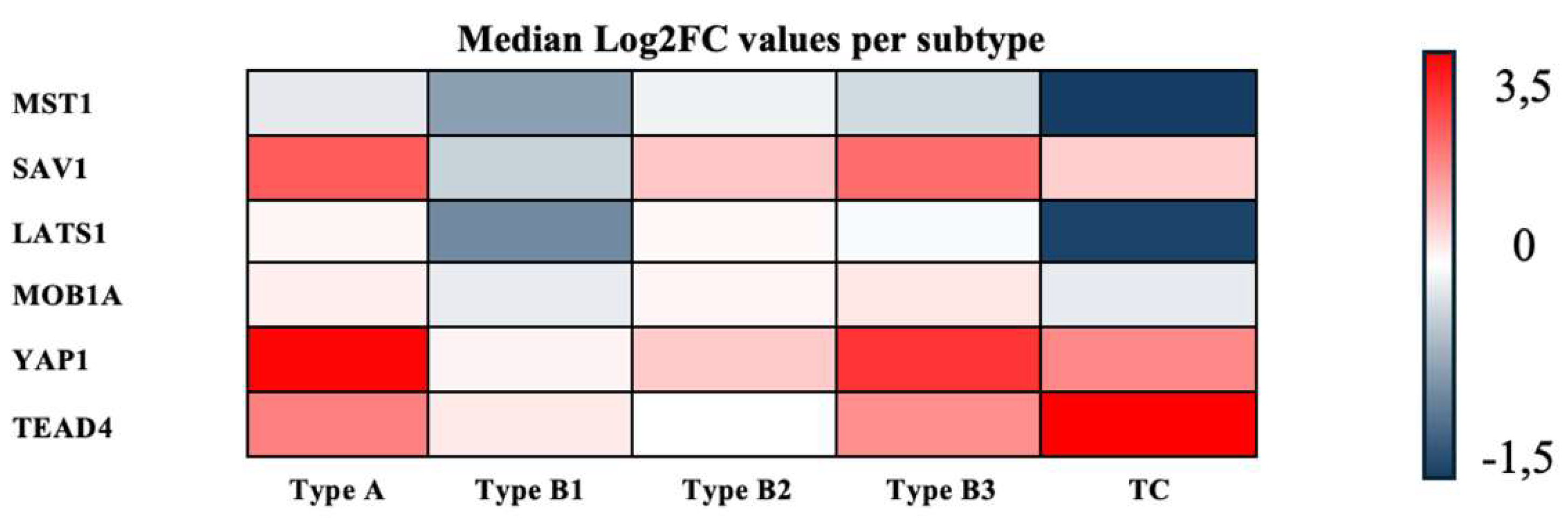

3.3. Consolidated Overview of the Relative Expression Results of Hippo Pathway Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMU TET(s) |

Paracelsus Medical University Thymic Epithelial Tumor(s) |

| FFPE (RT)-qPCR |

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (Real-time) quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| WHO FC(s) TC YAP1 TAZ WWTR1 TEAD1-4 IHC |

World Health Organization Fold change(s) Thymic Carcinoma Yes-associated protein 1 Transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif WW domain-containing transcription regulator 1 TEA domain transcription factor 1-4 Immunohistochemistry/immunohistochemical |

| MST1/2 SAV1 |

Mammalian STE20-like kinases 1/2 Salvador homolog 1 |

| LATS1/2 | Large tumor suppressor kinases 1/2 |

| MOB1(A) mRNA IRB gDNA IC RT TBP HPRT1 RTP Cq Log2FC N NTC NRT QC PPIA IDTTM cDNA MIQE HKG EMT AYAP TCGA GTF2I |

Mps one binder 1(A) Messenger RNA Institutional review board Genomic DNA Internal control Reverse transcription TATA-box binding protein Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 RealTimePrimers.com Quantification Cycle Log2-transformed fold changes Normal (thymus) sample No-template controls No-reverse transcription control Quality control Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase A Integrated DNA Technologies Complementary DNA Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments Housekeeping gene Epithelial–mesenchymal transition Active YAP1 The Cancer Genome Atlas Program General Transcription Factor II-I |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

Appendix A.4

References

- Imbimbo, M.; Salfi, G.; Borgeaud, M.; Ottaviano, M.; Froesch, P.; Bouchaab, H.; Cafarotti, S.; Addeo, A. Thymic epithelial tumors: what’s new and what’s next? ESMO Rare Cancers 2025, 4, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elm, L.; Gerlitz, N.; Hochholzer, A.; Papadopoulos, T.; Levidou, G. Hippo Pathway Dysregulation in Thymic Epithelial Tumors (TETs): Associations with Clinicopathological Features and Patients’ Prognosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von der Thüsen, J. Thymic epithelial tumours: histopathological classification and differential diagnosis. Histopathology 2024, 84, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barron, D. A.; Kagey, J. D. The role of the Hippo pathway in human disease and tumorigenesis. Clin Transl Med 2014, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Sardo, F.; Strano, S.; Blandino, G. YAP and TAZ in Lung Cancer: Oncogenic Role and Clinical Targeting. Cancers 2018, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. H.; Pahuja, K. B.; Hagenbeek, T. J.; Zbieg, J.; Noland, C. L.; Pham, V. C.; Yao, X.; Rose, C. M.; Browder, K. C.; Lee, H.-J.; et al. Targeting the Hippo pathway in cancers via ubiquitination dependent TEAD degradation; eLife Sciences Publications, Ltd., 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vega, F.; Mina, M.; Armenia, J.; Chatila, W. K.; Luna, A.; La, K. C.; Dimitriadoy, S.; Liu, D. L.; Kantheti, H. S.; Saghafinia, S.; et al. Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell 2018, 173, 321–337.e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamaris, K.; Levidou, G.; Kordali, K.; Masaoutis, C.; Rontogianni, D.; Theocharis, S. Searching for Novel Biomarkers in Thymic Epithelial Tumors: Immunohistochemical Evaluation of Hippo Pathway Components in a Cohort of Thymic Epithelial Tumors. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QIAGEN. QuantiNova SYBR Green RT-PCR Handbook; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bustin, S. A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J. A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M. W.; Shipley, G. L.; et al. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clinical Chemistry 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, D.; Uhl, B.; Sailer, V.; Holmes, E. E.; Jung, M.; Meller, S.; Kristiansen, G. Improved PCR Performance Using Template DNA from Formalin-Fixed and Paraffin-Embedded Tissues by Overcoming PCR Inhibition. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e77771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijter, J. M.; Pfaffl, M. W.; Zhao, S.; Spiess, A. N.; Boggy, G.; Blom, J.; Rutledge, R. G.; Sisti, D.; Lievens, A.; De Preter, K.; et al. Evaluation of qPCR curve analysis methods for reliable biomarker discovery: bias, resolution, precision, and implications. Methods 2013, 59, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suslov, O.; Steindler, D. A. PCR inhibition by reverse transcriptase leads to an overestimation of amplification efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svec, D.; Tichopad, A.; Novosadova, V.; Pfaffl, M. W.; Kubista, M. How good is a PCR efficiency estimate: Recommendations for precise and robust qPCR efficiency assessments. Biomol Detect Quantif 2015, 3, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowska, D.; Rothwell, L.; Bailey, R. A.; Watson, K.; Kaiser, P. Identification of stable reference genes for quantitative PCR in cells derived from chicken lymphoid organs. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 2016, 170, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rácz, G. A.; Nagy, N.; Gál, Z.; Pintér, T.; Hiripi, L.; Vértessy, B. G. Evaluation of critical design parameters for RT-qPCR-based analysis of multiple dUTPase isoform genes in mice. FEBS Open Bio 2019, 9, 1153–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, G.; Guan, P.; Barlow-Anacker, A. J.; Gosain, A. Comprehensive selection of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR analysis of murine extramedullary hematopoiesis during development. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0181881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Xiao, P.; Chen, D.; Xu, L.; Zhang, B. miRDeepFinder: a miRNA analysis tool for deep sequencing of plant small RNAs. Plant Mol Biol 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S. A.; Ruijter, J. M.; van den Hoff, M. J. B.; Kubista, M.; Pfaffl, M. W.; Shipley, G. L.; Tran, N.; Rödiger, S.; Untergasser, A.; Mueller, R.; et al. MIQE 2.0: Revision of the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments Guidelines. Clinical Chemistry 2025, 71, 634–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E.; Pescia, C.; Mendogni, P.; Nosotti, M.; Ferrero, S. Thymic Epithelial Tumors: An Evolving Field. Life 2023, Vol. 13, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Loskutov, J.; Küffer, S.; Marx, A.; Regenbrecht, C. R. A.; Ströbel, P.; Regenbrecht, M. J. Cell Culture Models for Translational Research on Thymomas and Thymic Carcinomas: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2024, Vol. 16, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Hu, Y.; Lan, T.; Guan, K.-L.; Luo, T.; Luo, M. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Maglic, D.; Dill, M. T.; Mojumdar, K.; Ng, P. K.-S.; Jeong, K. J.; Tsang, Y. H.; Moreno, D.; Bhavana, V. H.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of the Hippo Signaling Pathway in Cancer. Cell Reports 2018, 25, 1304–1317.e1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F. X.; Zhao, B.; Guan, K. L. Hippo Pathway in Organ Size Control, Tissue Homeostasis, and Cancer. Cell 2015, 163, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Li, L.; Lei, Q.; Guan, K. L. The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes Dev 2010, 24, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Jiao, Z.; Yu, F.-X. The Hippo signaling pathway in development and regeneration. Cell Reports 2024, 43, 113926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elm, L.; Levidou, G. The Molecular Landscape of Thymic Epithelial Tumors: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovich, M.; Pickering, C. R.; Felau, I.; Ha, G.; Zhang, H.; Jo, H.; Hoadley, K. A.; Anur, P.; Zhang, J.; McLellan, M.; et al. The Integrated Genomic Landscape of Thymic Epithelial Tumors. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 244–258.e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmauch, B.; Cabeli, V.; Domingues, O. D.; Le Douget, J. E.; Hardy, A.; Belbahri, R.; Maussion, C.; Romagnoni, A.; Eckstein, M.; Fuchs, F.; et al. Deep learning uncovers histological patterns of YAP1/TEAD activity related to disease aggressiveness in cancer patients. iScience 2025, 28, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Huang, B.; Zhu, L.; Chen, K.; Liu, M.; Zhong, C. Structural and Functional Overview of TEAD4 in Cancer Biology. Onco Targets Ther 2020, 13, 9865–9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Li, N.; Sun, C.; Li, Z.; Xie, H. A Four-Gene Prognostic Signature Based on the TEAD4 Differential Expression Predicts Overall Survival and Immune Microenvironment Estimation in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 874780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Collins, C. C.; Chen, C.-L.; Kung, H.-J. TEAD4 as an Oncogene and a Mitochondrial Modulator. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology;Review 2022, 10–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-Y.; Li, Y.-H.; Lin, H.-X.; Liao, Y.-J.; Mai, S.-J.; Liu, Z.-W.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Jiang, L.-J.; Zhang, J.-X.; Kung, H.-F.; et al. Overexpression of YAP 1 contributes to progressive features and poor prognosis of human urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Kang, Y.; Xue, N.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, B. Integrative analysis identifies TEAD4 as a universal prognostic biomarker in human cancers. In Frontiers in Immunology; Original Research, 2025; pp. 16–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. H.; Shin, J. E.; Park, H. W. The Role of Hippo Pathway in Cancer Stem Cell Biology. Molecules and Cells 2018, 41, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xu, R.; Li, X.; Ren, W.; Ou, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; et al. Prognostic Value of Yes-Associated Protein 1 (YAP1) in Various Cancers: A Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0135119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Chang, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, M.; Fan, H.-Y. YAP Promotes Ovarian Cancer Cell Tumorigenesis and Is Indicative of a Poor Prognosis for Ovarian Cancer Patients. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e91770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Ge, H.; Song, Y.; Wang, D.; Yuan, H.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, J. TEAD4 overexpression promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and associates with aggressiveness and adverse prognosis in head neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell International 2018, 18, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möhrmann, L.; Rostock, L.; Werner, M.; Oleś, M.; Arnold, J. S.; Paramasivam, N.; Jöhrens, K.; Rupp, L.; Schmitz, M.; Richter, D.; et al. Genomic landscape and molecularly informed therapy in thymic carcinoma and other advanced thymic epithelial tumors. Med 2025, 6, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. The role of YAP1 in survival prediction, immune modulation, and drug response: A pan-cancer perspective. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1012173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Zou, H.; Guo, Y.; Tong, T.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, P. The oncogenic roles and clinical implications of YAP/TAZ in breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer 2023, 128, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanconato, F.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. YAP/TAZ at the Roots of Cancer. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 783–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J. S.; Kim, S. M.; Lee, H. The Hippo signaling pathway provides novel anti-cancer drug targets. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 16084–16098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furth, N.; Aylon, Y. The LATS1 and LATS2 tumor suppressors: beyond the Hippo pathway. Cell Death Differ 2017, 24, 1488–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Moroishi, T.; Guan, K. L. Mechanisms of Hippo pathway regulation. Genes Dev 2016, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S. J.; Ni, L.; Osinski, A.; Tomchick, D. R.; Brautigam, C. A.; Luo, X. SAV1 promotes Hippo kinase activation through antagonizing the PP2A phosphatase STRIPAK. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Xie, R.; Guan, K.; Zhang, M. A WW Tandem-Mediated Dimerization Mode of SAV1 Essential for Hippo Signaling. Cell Rep 2020, 32, 108118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Nakamura, F. Importance of the filamin A-Sav1 interaction in organ size control: evidence from transgenic mice. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2023, 67, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Zheng, Y.; Hara, M.; Pan, D.; Luo, X. Structural basis for Mob1-dependent activation of the core Mst-Lats kinase cascade in Hippo signaling. Genes Dev 2015, 29, 1416–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Wang, W. A tale of two Hippo pathway modules. The EMBO Journal 2023, 42, EMBJ2023113970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, J. Ubiquitination-deubiquitination in the Hippo signaling pathway (Review). Oncol Rep 2019, 41, 1455–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. H.; Kugler, J. M. Ubiquitin-Dependent Regulation of the Mammalian Hippo Pathway: Therapeutic Implications for Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Li, C.; He, Y.; Xue, L.; Guo, X. Regulatory roles of RNA binding proteins in the Hippo pathway. Cell Death Discovery 2025, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.; Hansen, C. G. The Hippo pathway in cancer: YAP/TAZ and TEAD as therapeutic targets in cancer. Clin Sci (Lond) 2022, 136, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, B.; Guan, W.; Fan, Z.; Pu, X.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, W.; Cai, W.; Quan, X.; Miao, S.; et al. Molecular genetic characteristics of thymic epithelial tumors with distinct histological subtypes. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 10575–10586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, S. Genomic insights into molecular profiling of thymic carcinoma: a narrative review. Mediastinum 2024, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, N.; Li, M.; Hong, T.; Meng, W.; Ouyang, T. The Hippo Signaling Pathway: The Trader of Tumor Microenvironment. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 772134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtari, R. B.; Ashayeri, N.; Baghaie, L.; Sambi, M.; Satari, K.; Baluch, N.; Bosykh, D. A.; Szewczuk, M. R.; Chakraborty, S. The Hippo Pathway Effectors YAP/TAZ-TEAD Oncoproteins as Emerging Therapeutic Targets in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaboura, N. Unraveling the Hippo pathway: YAP/TAZ as central players in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Excli j 2025, 24, 612–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Ahlfen, S.; Missel, A.; Bendrat, K.; Schlumpberger, M. Determinants of RNA quality from FFPE samples. PLoS One 2007, 2, e1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M.; Pho, M.; Dutta, D.; Stephans, J. C.; Shak, S.; Kiefer, M. C.; Esteban, J. M.; Baker, J. B. Measurement of gene expression in archival paraffin-embedded tissues: development and performance of a 92-gene reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay. Am J Pathol 2004, 164, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggerholm-Pedersen, N.; Safwat, A.; Bærentzen, S.; Nordsmark, M.; Nielsen, O. S.; Alsner, J.; Sørensen, B. S. The importance of reference gene analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples from sarcoma patients - an often underestimated problem. Transl Oncol 2014, 7, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Huang, Y.; Lv, Q.; Yu, C.; Ying, J.; Duan, L.; Guo, Y.; Huang, G.; Shen, W.; et al. Abnormal Cellular Populations Shape Thymic Epithelial Tumor Heterogeneity and Anti-Tumor by Blocking Metabolic Interactions in Organoids. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2406653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagenbeek, T. J.; Zbieg, J. R.; Hafner, M.; Mroue, R.; Lacap, J. A.; Sodir, N. M.; Noland, C. L.; Afghani, S.; Kishore, A.; Bhat, K. P.; et al. An allosteric pan-TEAD inhibitor blocks oncogenic YAP/TAZ signaling and overcomes KRAS G12C inhibitor resistance. Nat Cancer 2023, 4, 812–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapeau, E. A.; Sansregret, L.; Galli, G. G.; Chène, P.; Wartmann, M.; Mourikis, T. P.; Jaaks, P.; Baltschukat, S.; Barbosa, I. A. M.; Bauer, D.; et al. Direct and selective pharmacological disruption of the YAP-TEAD interface by IAG933 inhibits Hippo-dependent and RAS-MAPK-altered cancers. Nat Cancer 2024, 5, 1102–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pobbati, A. V.; Kumar, R.; Rubin, B. P.; Hong, W. Therapeutic targeting of TEAD transcription factors in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci 2023, 48, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lao, Z.; Chen, X.; Pan, B.; Fang, B.; Yang, W.; Qian, Y. Pharmacological regulators of Hippo pathway: Advances and challenges of drug development. Faseb j 2025, 39, e70438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Median | Mix-Max | |

| Age (years) | 59 | 36-77 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 7.5 | 2.4-13 | |

| Number | % | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 13 | 56.5 | |

| Female | 10 | 43.5 | |

| WHO subtypes | |||

| Type A | 3 | 13 | |

| Type B1 | 5 | 21.7 | |

| Type B2 | 5 | 21.7 | |

| Type B3 | 5 | 21.7 | |

| Thymic carcinoma (TC) | 5 | 21.7 | |

| Masoka-Koga stage* | |||

| I | 5 | 21.7 | |

| II | 9 | 39.1 | |

| III | 2 | 8.7 | |

| IVa | 3 | 13 | |

| IVb | 2 | 8.7 | |

| Presence of Myasthenia Gravis | 4 | 17.4 | |

| Event | |||

| Alive, cencored | 23 | 100 | |

| Dead | 0 | 0 | |

| Fold Change (FC) (Median N1/N3) | Log2FC | |||||||||||

| Sample (TET subtype) | MST1 | SAV1 | LATS1 | MOB1A | YAP1 | TEAD4 | MST1 | SAV1 | LATS1 | MOB1A | YAP1 | TEAD4 |

| 1 (N) | 1.42 | 0.92 | 1.12 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.51 | –0.13 | 0.16 | –0.07 | –0.13 | –0.26 |

| 2 (N)* | 1.34 | 1.53 | 1.76 | 1.13 | 2.25 | 0.94 | 0.42 | 0.62 | 0.82 | 0.18 | 1.17 | –0.08 |

| 3 (N) | 0.70 | 1.09 | 0.89 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 1.20 | –0.51 | 0.13 | –0.16 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

| 4 (A) | 2.66 | 2.52 | 1.09 | 1.68 | 3.98 | 2.17 | 1.41 | 1.34 | 0.13 | 0.75 | 1.99 | 1.12 |

| 5 (A) | 0.90 | 14.07 | 2.05 | 1.06 | 10.76 | 5.07 | –0.15 | 3.82 | 1.04 | 0.08 | 3.43 | 2.34 |

| 6 (A) | 0.50 | 4.76 | 1.09 | 1.17 | 13.11 | 3.33 | –1.01 | 2.25 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 3.71 | 1.74 |

| 7 (B1) | 0.58 | 0.72 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 1.08 | 1.24 | –0.78 | –0.48 | –0.09 | –0.13 | 0.11 | 0.31 |

| 8 (B1) | 0.64 | 1.54 | 0.56 | 0.78 | 1.84 | 1.28 | –0.65 | 0.63 | –0.83 | –0.37 | 0.88 | 0.36 |

| 9 (B1) | 0.98 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 0.78 | 1.50 | 0.75 | –0.03 | 0.20 | 0.20 | –0.36 | 0.59 | –0.41 |

| 10 (B1) | 0.48 | 0.80 | 0.52 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 2.13 | –1.07 | –0.32 | –0.93 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 1.09 |

| 11 (B1) | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.98 | 0.73 | 0.62 | –0.68 | –0.82 | –1.40 | –0.02 | –0.45 | –0.69 |

| 12 (B2) | 1.13 | 1.20 | 1.08 | 0.89 | 1.57 | 0.88 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.10 | –0.16 | 0.65 | –0.19 |

| 13 (B2) | 0.64 | 1.60 | 0.75 | 1.04 | 1.67 | 0.27 | –0.65 | 0.67 | –0.42 | 0.05 | 0.74 | –1.90 |

| 14 (B2) | 0.76 | 1.74 | 0.53 | 1.11 | 2.68 | 1.01 | –0.39 | 0.80 | –0.91 | 0.15 | 1.42 | 0.01 |

| 15 (B2) | 0.94 | 4.38 | 1.26 | 1.21 | 4.34 | 4.97 | –0.09 | 2.13 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 2.12 | 2.31 |

| 16 (B2) | 0.96 | 1.72 | 1.09 | 1.22 | 1.28 | 1.39 | –0.06 | 0.78 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.48 |

| 17 (B3) | 0.69 | 2.70 | 0.98 | 1.24 | 4.15 | 1.38 | –0.53 | 1.44 | –0.03 | 0.31 | 2.05 | 0.47 |

| 18 (B3) | 2.10 | 3.96 | 1.50 | 1.47 | 6.86 | 0.96 | 1.07 | 1.99 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 2.78 | –0.06 |

| 19 (B3) | 0.76 | 4.03 | 0.58 | 0.96 | 5.61 | 3.84 | –0.40 | 2.01 | –0.78 | –0.06 | 2.49 | 1.94 |

| 20 (B3) | 1.15 | 7.54 | 1.10 | 2.05 | 12.79 | 5.21 | 0.20 | 2.92 | 0.14 | 1.04 | 3.68 | 2.38 |

| 21 (B3) | 0.83 | 6.57 | 0.80 | 1.25 | 7.15 | 2.93 | –0.26 | 2.72 | –0.32 | 0.33 | 2.84 | 1.55 |

| 22 (TC) | 0.43 | 3.67 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 3.11 | 4.83 | –1.21 | 1.88 | –0.43 | –0.45 | 1.64 | 2.27 |

| 23 (TC) | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.14 | 2.30 | 3.23 | 17.48 | –3.83 | –0.81 | –2.87 | 1.20 | 1.69 | 4.13 |

| 24 (TC) | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 1.40 | 3.05 | –1.38 | –0.28 | –0.67 | –0.14 | 0.48 | 1.61 |

| 25 (TC) | 0.26 | 1.59 | 0.33 | 0.71 | 0.96 | 11.22 | –1.93 | 0.67 | –1.62 | –0.49 | –0.06 | 3.49 |

| 26 (TC) | 0.52 | 2.17 | 0.39 | 0.96 | 3.19 | 12.19 | –0.94 | 1.12 | –1.34 | –0.06 | 1.67 | 3.61 |

| MST1 | SAV1 | LATS1 | MOB1A | YAP1 | TEAD4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymoma Type A | –0.15 | 2.25 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 3.43 | 1.74 |

| Thymoma Type B1 | –0.68 | –0.32 | –0.83 | –0.13 | 0.18 | 0.31 |

| Thymoma Type B2 | –0.09 | 0.78 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.74 | 0.01 |

| Thymoma Type B3 | –0.26 | 2.01 | –0.03 | 0.33 | 2.78 | 1.55 |

| Thymus Carcinoma (TC) | –1.38 | 0.67 | –1.34 | –0.14 | 1.64 | 3.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).