1. Introduction

Schizophrenia presents enduring challenges for theoretical integration due to pronounced heterogeneity across genetic liability, neurodevelopmental trajectories, circuit physiology, cognition, symptom expression, epidemiology, and treatment response. Findings at these levels are often addressed within partially overlapping models that emphasize distinct explanatory domains, including genetic risk, neurodevelopmental disruption, neurotransmitter dysfunction, and psychosocial stress, leaving open the question of how disparate observations can be coherently related without presupposing a single causal pathway or privileging one level of explanation.

The Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM) has been introduced as a systems-level framework intended to organize such heterogeneity through threshold-based relations among sensitivity, cumulative load, and processing capacity [

1]. A comprehensive exposition of the STM framework is provided elsewhere [

1]; the present paper does not revise, extend, or further elaborate its formal structure.

Instead, this work applies STM as an organizing lens to a set of 22 canonical findings in schizophrenia articulated by MacDonald and Schulz [

2]. These findings are widely cited as empirically robust phenomena that have shaped theoretical discourse in the field and are used here as reference points for conceptual mapping rather than as criteria for validation. For each finding, STM’s core constructs are used to illustrate how observations spanning multiple levels of organization may be interpreted within a shared systems-level structure.

The aim of this analysis is to demonstrate the internal coherence and organizational reach of STM when applied to established empirical phenomena, rather than to adjudicate among competing theories or to establish explanatory sufficiency. By situating diverse findings within a common conceptual architecture, the paper seeks to clarify relationships among observations and to highlight areas where STM-based interpretations may motivate future empirical investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper applies the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM) as a conceptual organizing framework to a set of twenty-two established findings in schizophrenia synthesized by MacDonald and Schulz [

2]. These findings are widely cited empirical phenomena spanning genetics, neurodevelopment, neurophysiology, cognition, symptom expression, epidemiology, and treatment response, and are used here as reference points for structured conceptual mapping rather than as criteria for theory validation. For the purposes of the present work, the findings are treated as fixed empirical observations that constrain interpretation, not as benchmarks for adjudicating explanatory success.

STM’s core constructs were applied in a multi-scale, descriptive manner to facilitate alignment with observations across levels of organization. Sensitivity was treated as baseline neural and psychological reactivity shaped by genetic, epigenetic, developmental, and constitutional factors. Load was treated as the cumulative influence of environmental, psychosocial, sensory, metabolic, immune, and pharmacological demands acting on neural systems. Capacity was treated as the regulatory and processing resources supporting neural stability, inhibition, integration, and adaptive regulation across microcircuit, regional, and whole-brain levels. Threshold dynamics were used as a conceptual descriptor of instability that may arise when interactions among sensitivity and load exceed available capacity, potentially affecting cognition, perception, and behavior. These constructs were treated as continuous dimensions capable of correspondence with cellular properties (e.g., excitatory–inhibitory balance), circuit-level dynamics, computational processes, and clinically observable phenomena.

Each of the twenty-two findings was examined using a structured mapping procedure. The empirical phenomenon was first decomposed into its biological, computational, and clinical components as described in the literature. STM constructs were then aligned to these components to illustrate how the observation could be situated within a common systems-level structure. Where appropriate, multi-level relational sequences were outlined to clarify how micro-level vulnerabilities and system-level constraints may be conceptually linked to the reported outcome, without asserting causal sufficiency.

The resulting mappings are presented as candidate interpretations expressed in STM sensitivity–load–capacity relations, together with indications of how specific dependencies could motivate future hypothesis generation. Collectively, this approach is intended to clarify the organizational scope and internal consistency of STM when applied to established empirical observations, rather than to establish explanatory adequacy or comparative superiority.

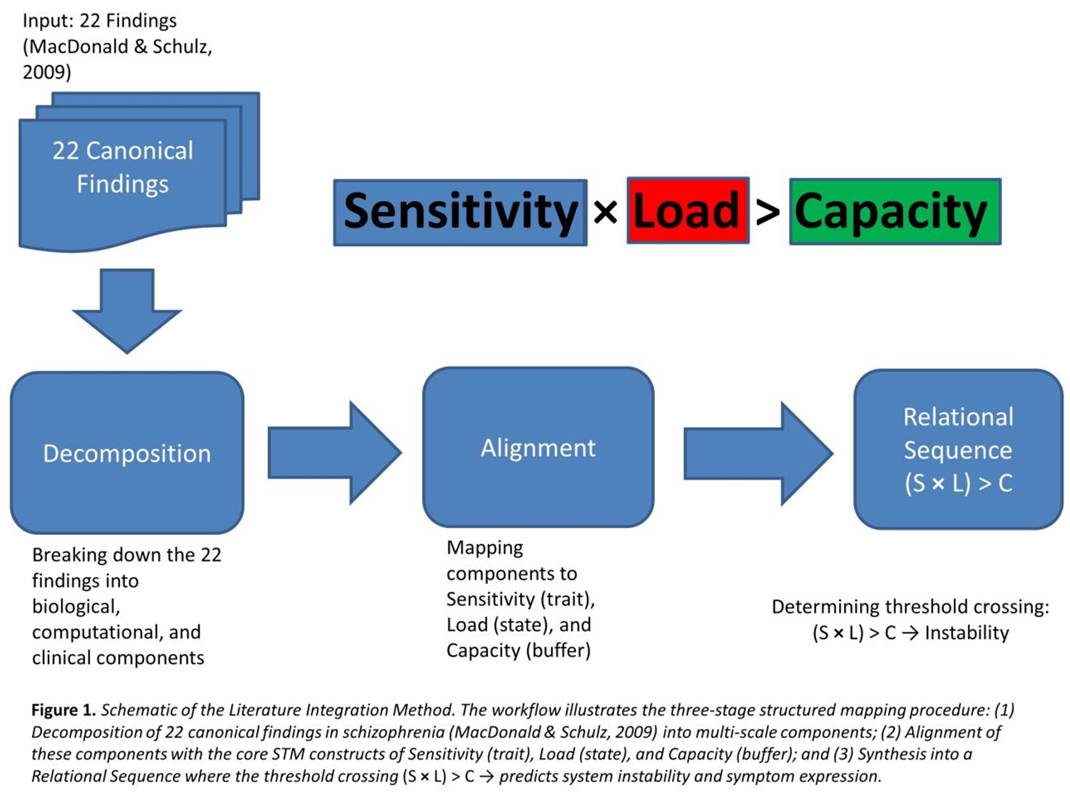

The mapping procedure followed a three-stage workflow, as illustrated in Figure 1.

3. Results

3.1. Core Finding 1 – Symptom Heterogeneity and Dynamic Phenotypic Variability

3.1.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia exhibit marked heterogeneity in symptom presentation, including varying combinations of positive symptoms, negative symptoms, disorganization, mood dysregulation, and cognitive impairment. This variability is observed both across individuals and within individuals across illness phases, with shifts in symptom dominance over time [

3,

4,

5].

3.1.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), symptom heterogeneity is interpreted as a consequence of subsystem-specific instability arising from interactions among individual sensitivity profiles, cumulative load, and finite processing capacity. STM accommodates the observation that different neural subsystems may reach instability thresholds under similar global conditions, depending on regionally distributed sensitivity shaped by genetic and developmental factors [

6,

7]. As a result, symptom expression is framed as reflecting which functional domains are most vulnerable at a given time, rather than as fixed categorical subtypes.

3.1.3. Mechanistic Implications (within Existing STM Constructs)

At the microcircuit level, subsystem-specific overload is consistent with excitatory–inhibitory imbalance, interneuron dysfunction, and synaptic instability, with regionally variable consequences [

8,

9]. At the network level, instability in thalamo-temporal circuits aligns with perceptual disturbances, fronto-striatal and limbic disruptions align with motivational and affective changes, and fronto-parietal destabilization aligns with executive dysfunction and disorganization [

10,

11,

12]. From a computational perspective, STM frames these patterns as domain-specific degradation of prediction stability, precision weighting, and error integration across perceptual, motivational, and control systems [

13,

14,

15]. At the behavioral level, these dynamics correspond to distinct cognitive and symptomatic profiles, including intrusive perceptual experiences, motivational blunting, and fragmented thought processes [

16].

3.1.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that experimentally manipulating sensory, motivational, or executive load would differentially influence symptom domains depending on individual vulnerability profiles. It further suggests that dominant symptom patterns may shift within individuals as load is redistributed across subsystems due to factors such as stress, sleep disruption, or substance exposure [

4]. Pre-illness measures of domain-specific sensitivity may therefore show prospective associations with later symptom predominance, and symptom clusters may be accompanied by distinguishable circuit-level signatures.

3.2. Core Finding 2 – Stable Lifetime Prevalence Near 0.7%

3.2.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Across cultures, continents, socioeconomic conditions, and historical eras, schizophrenia shows a relatively stable lifetime prevalence, typically estimated between 0.5% and 1.0%, with convergence near 0.7% [

17,

18]. This stability persists despite substantial variation in environmental exposures, fertility patterns, mortality rates, and access to health resources. The combination of rarity and cross-cultural consistency has been widely treated as a constraining feature for theoretical accounts [

5].

3.2.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), stable low prevalence is interpreted as an emergent population-level pattern arising from interactions among continuously distributed sensitivity, cumulative load, and finite capacity, rather than from discrete disease categories. STM accommodates the observation that sensitivity-related traits—such as stress responsivity, sensory reactivity, dopaminergic tone, immune activation, and inhibitory gating—are continuously distributed in the population [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In this framing, individuals at the higher end of sensitivity distributions may operate closer to instability thresholds under comparable environmental conditions, while most individuals remain well below such limits.

3.2.3. Mechanistic Implications (within Existing STM Constructs)

At the biological and systems levels, heightened sensitivity is conceptually aligned with reduced inhibitory reserve and narrower stability margins under cumulative stress [

8]. Environmental load is treated as an independently varying dimension encompassing social adversity, trauma, urbanicity, metabolic and inflammatory stress, sleep disruption, and sustained environmental unpredictability [

23,

24,

25]. STM provides a framework in which neither high sensitivity nor high load alone necessitates instability; rather, psychosis-level dysfunction is situated near regions of overlap where elevated sensitivity coincides with sustained load relative to available capacity. From this perspective, stable low prevalence reflects the rarity of such joint conditions at the population level rather than the infrequency of sensitivity or stress exposure per se.

At a population scale, STM allows observed prevalence ranges to be conceptually related to the tails of interacting continuous distributions. Modest cross-cultural variation in sensitivity traits and environmental load is therefore interpreted as compatible with relatively stable prevalence estimates when threshold relations constrain the frequency of instability.

3.2.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that schizophrenia incidence may be more closely associated with interactive sensitivity–load relationships than with either factor considered independently. It further suggests that increases in environmental load may disproportionately affect individuals with higher sensitivity profiles, while sustained reductions in cumulative load could shift population-level risk distributions. Epidemiological patterns may therefore be examined for consistency with threshold-based, multiplicative risk structures rather than linear additive models, providing potential avenues for future empirical evaluation.

3.3. Core Finding 3 – Sex Differences in Prevalence and Age of Onset

3.3.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Epidemiological studies consistently report sex differences in schizophrenia risk and timing. Males show a higher incidence in late adolescence and early adulthood, along with earlier onset and greater early negative symptom burden, whereas females show a later mean age of onset with a secondary incidence peak after midlife, often following menopause. Across the full lifespan, prevalence rates converge, and sex differences diminish in later adulthood [

26,

27,

28]. Any explanatory framework must therefore account for early male vulnerability, delayed female onset, and age-dependent convergence of risk.

3.3.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), sex differences in prevalence and age of onset are interpreted as reflecting lifespan-dependent interactions among sensitivity, cumulative load, and capacity, rather than as evidence of sex-specific disease mechanisms. STM accommodates the possibility that developmental trajectories differ between males and females in ways that influence proximity to stability thresholds at different life stages. These differences are framed as quantitative shifts in threshold proximity over time, shaped by neurodevelopmental timing, hormonal modulation, and patterns of load accumulation.

3.3.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

From a developmental perspective, male neurodevelopment has been associated with greater dopaminergic variability, slower maturation of frontal regulatory systems, and reduced early inhibitory buffering, which may correspond to higher effective sensitivity during adolescence and early adulthood [

29,

30]. In contrast, female development is associated with earlier prefrontal maturation and estrogen-related modulation of synaptic stability, stress responsivity, and inhibitory control, which can be interpreted within STM as contributing to greater effective capacity during early and mid-adulthood [

31]. With menopause, estrogen-mediated buffering declines [

32,

33], potentially narrowing sex differences in threshold proximity.

Differences in load trajectories further shape these patterns. Males, on average, experience higher early-life load through greater exposure to sleep disruption, substance use [

34], and through increased exposure to trauma-prone environments, and social instability [

35]. Females tend to accumulate load more gradually across adulthood, including caregiving stress, metabolic and vascular changes, sleep disruption, and cumulative allostatic burden. Within STM, early male risk is thus framed as reflecting the convergence of elevated developmental sensitivity with higher early load under comparatively lower buffering capacity, whereas later female risk reflects increasing cumulative load coinciding with declining hormone-mediated capacity.

3.3.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that markers of sensory gating, stress reactivity, and predictive instability may show age- and sex-dependent changes, including potential worsening in women during the menopausal transition. It further suggests that males with lower cumulative early-life load may exhibit delayed onset distributions, and that hormonal modulation could influence threshold proximity in susceptible individuals. Population-level modeling of sensitivity–load interactions may therefore be examined for age- and sex-dependent risk patterns consistent with observed bimodal incidence distributions.

3.4. Core Finding 4 – Sex Differences in Prevalence and Age of Onset

3.4.1 Finding (Brief Restatement)

Schizophrenia onset shows a pronounced peak in late adolescence and early adulthood. Males most commonly present between the late teens and mid-20s, while females show a slightly later peak, typically in the late 20s to early 30s. Onset before puberty or after midlife is comparatively rare, and this age distribution is conserved across cultures and historical periods [

36,

37,

4]. This temporal clustering represents a strong constraint on theoretical accounts, as risk is concentrated within a narrow developmental window rather than distributed evenly across the lifespan.

3.4.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), the concentration of onset during adolescence and early adulthood is interpreted as reflecting the convergence of age-dependent changes in sensitivity, cumulative load, and regulatory capacity, rather than a disorder-specific developmental trigger. STM accommodates the observation that this life stage is characterized by transient shifts in multiple system properties that jointly influence proximity to stability thresholds. Risk is therefore framed as emerging from predictable developmental dynamics rather than from a discrete pathological event.

3.4.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Adolescence and early adulthood are associated with heightened emotional and neurobiological reactivity, including pubertal and post-pubertal hormonal influences that modulate affective and dopaminergic systems [

37]. During this period, prefrontal regulatory systems continue to mature while limbic and sensory systems reach functional prominence, which can be interpreted within STM as a temporary elevation in effective sensitivity. Concurrently, synaptic pruning and prolonged myelination alter network organization, reducing redundancy and transiently narrowing stability margins. At the same time, cumulative load increases sharply due to rising social complexity, academic and occupational demands, sleep disruption, and the initiation of psychoactive substance exposure [

35,

38,

39]. STM frames this developmental interval as one in which elevated sensitivity, rapidly increasing load, and temporarily constrained capacity are more likely to coincide, increasing the likelihood that vulnerable individuals approach instability thresholds.

As regulatory systems mature and developmental reorganization stabilizes in later adulthood, capacity is interpreted as becoming more robust, while the rate of new load accumulation typically slows. Within STM, this shift is consistent with the marked decline in first-episode onset observed after early adulthood.

3.4.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that measures of inhibitory reserve, effective connectivity, and regulatory network stability may show transient reductions during adolescence relative to both childhood and mature adulthood. It further suggests that high-load environments—such as sustained sleep disruption, urbanicity, or intensive digital stimulation—may preferentially elevate onset risk within the adolescent and young adult age range. Individuals with heightened emotional or sensory reactivity may therefore show disproportionate vulnerability during periods of synaptic reorganization and myelination, while sex- and hormone-related modulation may shift threshold proximity within this window.

3.5. Core Finding 5 – High Heritability with Partial Monozygotic Twin Concordance

3.5.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Schizophrenia exhibits high heritability, commonly estimated at approximately 80–85%, yet concordance among monozygotic twins is incomplete, typically reported in the range of ~48–55% [

40,

41]. This pattern indicates a strong genetic contribution to vulnerability while also demonstrating that identical genomes do not yield uniform clinical outcomes. Any explanatory framework must therefore account for why genetic influence is substantial but not determinative.

3.5.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), this pattern is interpreted as consistent with genetic factors primarily shaping baseline sensitivity and aspects of capacity, while cumulative load accrues through partially stochastic and non-shared developmental processes. STM accommodates the observation that genetic liability confers vulnerability by influencing neural reactivity, inhibitory reserve, metabolic resilience, and developmental precision, without implying that genetic variation alone specifies disease expression. Divergence in outcomes among monozygotic twins is thus framed as reflecting differences in lifetime load trajectories relative to shared sensitivity profiles.

3.5.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Early in development, monozygotic twins may differ subtly in biological conditions such as placental environment, perinatal oxygenation, inflammatory exposure, or other sources of developmental variability, introducing small differences in initial system stability [

42]. Over time, these differences may be compounded by non-shared environmental exposures, including sleep patterns, psychosocial stress, trauma, substance use, infection burden, and social context. Within STM, such factors are treated as contributors to cumulative load that interact with genetically influenced sensitivity and finite capacity. From a threshold perspective, identical sensitivity profiles combined with divergent load accumulation naturally allow for high but incomplete concordance, as only some individuals approach or cross instability thresholds under their specific load histories.

At the behavioral and clinical levels, relatively modest divergence in regulatory demands or stress exposure may therefore correspond to different positions relative to threshold proximity, yielding discordant outcomes despite shared genetic vulnerability.

3.5.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that discordant monozygotic twin pairs may show greater divergence in cumulative lifetime load measures than in baseline sensitivity indicators. It further suggests that epigenetic variation related to stress, immune signaling, and plasticity may track with discordance, and that modeling approaches combining shared sensitivity with variable load distributions could reproduce observed concordance ranges. Early developmental factors that contribute to micro-level load differences may also warrant examination for their potential association with later divergence in clinical outcomes.

3.6. Core Finding 6 – Universal D2 Blockade and Stabilization of Salience Dysregulation

3.6.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

All currently effective antipsychotic medications share dopamine D2 receptor antagonism, with clinical efficacy closely related to receptor occupancy [

43,

44]. Despite this shared pharmacological feature, antipsychotics show limited effects on cognitive and negative symptoms, and clozapine—despite relatively lower D2 affinity—demonstrates superior efficacy in treatment-resistant schizophrenia [

45]. This pattern constrains interpretation by requiring an account of why D2 blockade is broadly necessary for symptom stabilization, why dopaminergic dysregulation is prominent, and why therapeutic effects are domain-specific.

3.6.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), dopaminergic signaling is interpreted as a load-sensitive channel involved in salience attribution and precision allocation, rather than as a primary disease driver. STM accommodates the observation that dopamine-related genetic and developmental variation influences sensitivity within salience-processing systems, including striatal reactivity and stress responsivity, without implying that dopamine dysfunction alone defines schizophrenia. In this framing, dopaminergic dysregulation is situated downstream of cumulative system strain, emerging as one manifestation of broader instability in neural processing under high sensitivity and load conditions.

3.6.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Under conditions of elevated sensory, emotional, cognitive, or metabolic load, salience-related networks—often involving striatal, insular, and cingulate circuitry—may become increasingly reactive and unstable. STM interprets this instability as contributing to excessive or inappropriate precision assignment to internal predictions or external stimuli, consistent with phenomena described as aberrant salience, hallucinations, and delusional belief formation. From this perspective, D2 receptor antagonism can be framed as a stabilizing intervention that reduces gain within an overloaded salience channel, thereby diminishing the behavioral impact of noisy or exaggerated prediction signals. This interpretation aligns with the preferential efficacy of antipsychotics for positive symptoms, while also accommodating their limited effects on cognition and motivation, which depend on broader capacity and load-related factors.

Clozapine’s distinctive clinical profile is interpreted within STM as reflecting its broader pharmacological effects across multiple systems, including dopaminergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic, serotonergic, and inflammatory pathways. Rather than acting solely on salience gain, clozapine may reduce effective load or instability across several interacting channels simultaneously, which is consistent with its efficacy in cases where narrower interventions are insufficient.

3.6.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that markers of salience-network instability may covary with acute load in high-sensitivity individuals, and that antipsychotic response may relate more closely to baseline salience dysregulation than to tonic dopamine measures. It further suggests that treatments with broader load-reducing or stabilizing effects may show enhanced efficacy in resistant cases, and that non-pharmacological interventions targeting sleep, stress, or sensory burden could modulate salience-related symptoms alongside or independent of dopamine blockade.

3.7. Core Finding 7 – Polygenic Risk and Distributed Vulnerability Architecture

3.7.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Genomic studies consistently indicate that schizophrenia risk is highly polygenic, involving hundreds of common variants and rare copy number variants (CNVs), with no single locus accounting for more than a small fraction of overall risk [

46,

6,

47,

48]. Genetic risk profiles vary widely across individuals and families, yet clinical presentations often converge, and even high-impact variants such as 22q11.2 deletions remain non-deterministic. This pattern constrains interpretation by requiring an account of why genetic liability confers vulnerability rather than inevitability.

3.7.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), this genomic architecture is interpreted as reflecting distributed modulation of sensitivity and capacity across neural systems, rather than the encoding of schizophrenia as a discrete genetic condition. STM accommodates the observation that diverse genetic variants can influence baseline neural reactivity, regulatory reserve, and recovery margins without specifying symptom form or clinical outcome. In this framing, polygenicity reflects the multiplicity of biological pathways through which proximity to instability thresholds may be shifted.

3.7.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Variants influencing sensory gain, dopaminergic and glutamatergic signaling, stress responsivity, immune activation, and sleep–wake regulation can be conceptually aligned with shifts in effective sensitivity. Variants affecting inhibitory stability, synaptic plasticity, mitochondrial and oxidative resilience, neurotrophic support, and myelination fidelity can be aligned with aspects of capacity. At circuit and systems levels, heterogeneous genetic perturbations are interpreted as converging on a common pattern of reduced stability margins under cumulative load, despite differing molecular entry points. From a computational perspective, individual variants may contribute small changes in noise sensitivity, energetic cost, precision weighting, or recovery dynamics, with aggregate effects influencing how rapidly systems approach instability under stress.

At cognitive and behavioral levels, this distributed architecture is consistent with subtle, trait-like differences in sensory filtering, stress tolerance, emotional regulation, sleep stability, and cognitive buffering that precede clinical onset. Within STM, convergence of psychotic phenotypes under high load is therefore interpreted as reflecting shared system-level failure modes rather than shared genetic causes.

3.7.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that polygenic risk scores may show stronger associations with quantitative measures of sensitivity, regulatory reserve, and recovery capacity than with specific symptom categories. It further suggests that distinct genetic risk profiles could yield similar psychosis-level outcomes under comparable high-load conditions, and that rare high-impact variants may be more likely to express clinically when accompanied by substantial cumulative load. Functional indicators of excitatory–inhibitory balance, sensory prediction noise, or recovery dynamics may therefore warrant examination as potential intermediates linking polygenic risk to clinical vulnerability.

3.8. Core Finding 8 – Subclinical Cognitive and Structural Differences in Unaffected Relatives

3.8.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Unaffected first-degree relatives of individuals with schizophrenia show small but reliable differences in cognition and brain structure, including mild reductions in executive function, working memory, and attentional control, as well as subtle alterations in gray matter volume, hippocampal integrity, and, in some studies, large-scale connectivity [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. Despite these deviations, most relatives do not develop psychosis and function within normative ranges. This pattern constrains interpretation by requiring an account of why measurable neural and cognitive differences can be present without progression to clinical illness.

3.8.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), these observations are interpreted as reflecting inherited sensitivity–capacity configurations that remain below instability thresholds under typical lifetime load. STM accommodates the finding that relatives may share genetic variants influencing baseline neural reactivity or regulatory reserve, positioning them closer to threshold boundaries without necessitating system-level failure. In this framing, subclinical differences are understood as stable expressions of vulnerability architecture rather than indicators of incipient disease.

3.8.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

At the circuit level, proximity to threshold is conceptually aligned with modest reductions in inhibitory precision, slightly less efficient prefrontal and hippocampal buffering, and increased noise in long-range coordination. These effects are expected to be subtle, producing detectable differences in neuroimaging or cognitive performance without compromising overall system stability. From a computational perspective, elevated sensitivity may require greater regulatory effort to maintain stable processing, increasing energetic cost and narrowing performance margins without generating overt instability. Behaviorally, this is consistent with mild inefficiencies in attentional control, working memory updating, and distractor suppression that remain stable over time when cumulative environmental and physiological load does not exceed available capacity.

3.8.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that experimentally increasing cognitive, emotional, or physiological load may reveal disproportionately larger performance decrements in unaffected relatives compared to controls, reflecting reduced buffering margins. It further suggests that subclinical cognitive and structural differences may correlate more strongly with polygenic risk measures than with symptom expression, and that such deviations are likely to remain non-progressive in the absence of sustained high load. Longitudinal exposure to elevated load—such as chronic sleep disruption, prolonged stress, or inflammatory burden—may therefore be examined for its potential to shift near-threshold systems toward greater instability.

3.9. Core Finding 9 – Environmental Contributors as Load and Capacity Modulators

3.9.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

A wide range of environmental exposures—including migration, urbanicity, discrimination, and psychosocial adversity [

53,

54], cannabis and stimulant use [

55], perinatal complications and seasonal birth effects [

53], and infection (e.g.,

Toxoplasma gondii) [

56]—are each associated with modest but reliable increases in schizophrenia risk, typically with odds ratios in the range of approximately 1.2–3.0 [

54,

57]. These exposures are heterogeneous in timing, biological targets, and contextual meaning, yet together form one of the most consistent epidemiological signatures of the disorder. Any explanatory framework must therefore account for why diverse environmental factors exert small but reproducible effects and how they converge on a shared clinical phenotype.

3.9.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), environmental contributors are interpreted as influencing psychosis risk through a common functional role: modulation of cumulative load and/or effective capacity. STM accommodates the observation that heterogeneous exposures can increase risk without invoking exposure-specific disease mechanisms, by framing them as perturbations that incrementally alter system demands or reduce regulatory reserve. In this view, convergence arises not from shared etiology but from shared effects on system stability.

3.9.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Perinatal factors such as infection, hypoxia, and malnutrition are conceptually aligned with early reductions in effective capacity, narrowing long-term regulatory margins. Exposures such as urbanicity, migration, discrimination, chronic stress, and social adversity are framed as persistent sources of psychosocial and sensory load, while cannabis use, stimulant exposure, sleep disruption, and inflammatory states are treated as acute or recurrent load amplifiers. Despite their diversity, these exposures are unified within STM by their tendency to increase background neural noise, elevate regulatory demand, disrupt inhibitory balance, or raise the energetic cost of maintaining stable processing.

At the systems level, such influences are interpreted as incrementally stressing thalamocortical filtering, prefrontal regulation, hippocampal context processing, and limbic threat monitoring. Individually, these effects are insufficient to produce instability, but over development and adulthood they may accumulate, particularly in individuals with elevated sensitivity or reduced capacity. Clinical psychosis is therefore framed as an emergent outcome of integrated lifetime load interacting with constrained regulatory reserve, rather than as the result of any single environmental exposure.

3.9.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that aggregated measures of cumulative environmental load may show stronger associations with schizophrenia risk than individual exposures considered in isolation. It further suggests that combinations of modest risk factors may interact nonlinearly, with effects amplified in individuals with higher sensitivity or lower capacity. Interventions that reduce sustained load—such as improving sleep stability, mitigating chronic stress and discrimination, reducing environmental pollutants, or lowering sensory burden—may therefore be examined for their potential to shift population-level risk distributions, particularly in vulnerable groups.

3.10. Core Finding 10 – Delayed and Variable Antipsychotic Response as Multi-Timescale System Stabilization

3.10.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Antipsychotic medications achieve dopamine D2 receptor occupancy within hours, yet clinically meaningful improvements in hallucinations, delusions, and disorganization typically emerge only after weeks of treatment [

58,

59]. Treatment response varies substantially across individuals, with many patients showing partial or delayed improvement [

60,

61]. In contrast, negative symptoms show limited responsiveness to antipsychotic treatment [

62,

16], while cognitive impairments often improve slowly or remain largely unchanged [

16,

61]. This temporal dissociation between rapid receptor engagement and delayed clinical change constrains interpretation by requiring an account of why symptom stabilization unfolds gradually and why recovery trajectories differ across patients.

3.10.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), delayed clinical improvement is interpreted as reflecting multi-scale system destabilization rather than a single neurotransmitter abnormality. STM accommodates the observation that dopaminergic modulation can rapidly alter salience-related signaling while broader circuit- and system-level parameters recover more slowly. From this perspective, antipsychotic response is framed as a staged stabilization process in which different components of the system normalize on distinct timescales.

3.10.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

D2 receptor antagonism is interpreted within STM as rapidly reducing excessive gain within salience-related channels, thereby attenuating the most disruptive prediction signals. However, STM does not treat this intervention as sufficient to immediately restore system stability. Regulatory features affected by sustained overload—including inhibitory precision, oscillatory coordination, metabolic clearance capacity, and thalamocortical filtering—are conceptualized as requiring days to weeks to re-equilibrate once excessive salience amplification is reduced. At the computational level, predictive processes destabilized by prolonged noise are framed as gradually recalibrating precision weighting and restoring stable internal models, processes that are slower than receptor pharmacodynamics.

Clinically, this interpretation is consistent with early reductions in agitation or perceptual intensity followed by more gradual improvements in coherence, contextual integration, and reality testing. Persistent negative or cognitive symptoms are framed as reflecting residual load or limited capacity rather than incomplete dopaminergic engagement.

Evidence from sleep-deprivation studies provides an illustrative analogue for these multi-timescale dynamics. Controlled experiments show that progressive sleep loss in healthy individuals is associated with graded emergence of perceptual distortions and psychosis-like experiences, followed by gradual symptom resolution with recovery sleep [

63]. Within STM, such findings are interpreted as demonstrating how isolated increases in load can drive systems toward instability and how recovery depends on time-dependent restoration of regulatory and metabolic processes, rather than on rapid signaling changes alone.

3.10.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that D2 receptor occupancy may relate more closely to early reductions in agitation or salience-related symptoms than to the overall pace of clinical recovery. It further suggests that neurophysiological indicators of network stability may normalize gradually over weeks and that persistent physiological or psychosocial load—such as sleep disruption or inflammatory burden—may delay stabilization despite adequate receptor blockade. Baseline measures of regulatory reserve and cumulative load may therefore be examined as potential predictors of individual recovery trajectories, and interventions that reduce ongoing load, including sleep normalization, may be evaluated for their potential to accelerate later phases of symptom improvement.

3.11. Core Finding 11 – Amphetamine-Induced Psychosis as Salience Overload

3.11.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Amphetamine and related psychostimulants can induce hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia that are often clinically similar to schizophrenia [

64,

65], with risk increasing as a function of dose, duration of exposure, and sensitization [

65,

66]. At the same time, many exposed individuals do not develop psychosis, and susceptibility varies substantially across individuals, indicating incomplete penetrance of stimulant-induced risk [

66,

67]. This pattern constrains interpretation by requiring an account of why dopaminergic stimulation can reproduce psychosis-like phenomena, why only a subset of exposed individuals cross clinical thresholds, and why repeated exposure increases vulnerability.

3.11.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), stimulant-induced psychosis is interpreted as a pharmacologically driven increase in system load imposed on an existing sensitivity–capacity architecture. STM accommodates the observation that individuals differ in baseline sensitivity across salience, sensory, affective, and regulatory systems, which influences how strongly dopaminergic perturbation affects network stability. In this framing, amphetamine exposure does not introduce a distinct pathological mechanism but acts as an acute load amplifier that can transiently push vulnerable systems toward instability.

3.11.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Amphetamine-induced increases in dopaminergic signaling are conceptually aligned within STM with heightened gain in salience-related networks, including striatal, limbic, and cortical pathways. This gain amplification is interpreted as increasing precision assignment to internal and external signals, placing elevated demands on inhibitory control and thalamocortical filtering. At the systems level, such perturbations may lead to patterns of salience dysregulation, contextual instability, and reduced prefrontal regulatory influence that resemble those observed in non–substance-induced psychosis, differing primarily in timing and mode of induction rather than in overall system organization.

From a computational perspective, excessive gain is framed as disrupting prediction-error regulation and belief updating processes, leading to unstable inference under conditions of heightened noise. Behaviorally, this may manifest as hypervigilance, suspiciousness, disorganized thought, and perceptual disturbances. Individuals with greater effective capacity or lower baseline sensitivity may tolerate substantial dopaminergic perturbation without crossing instability thresholds, whereas those with higher sensitivity may approach such thresholds at lower doses or shorter exposure durations. Repeated stimulant exposure is interpreted as incrementally altering baseline sensitivity or regulatory reserve, thereby shifting threshold proximity over time.

3.11.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that baseline measures of sensory gain, salience responsivity, or regulatory reserve may predict individual vulnerability to stimulant-induced psychosis. It further suggests that indicators of salience-network instability may increase prior to symptom emergence and that reductions in background load—such as minimizing sleep disruption or psychosocial stress—could modulate susceptibility. Longitudinal exposure to stimulants may also be examined for associations with progressive changes in regulatory stability that influence future threshold proximity.

3.12. Core Finding 12 – NMDA Antagonists and Overload-Like Computational Disruption

3.12.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Phencyclidine (PCP) and ketamine, both NMDA receptor antagonists, can induce a syndrome resembling schizophrenia across multiple domains, including positive, negative, cognitive, and dissociative symptoms [

68,

69,

70,

71]. Compared with dopaminergic agents, these compounds more reliably impair cognition and motivation in addition to perception, suggesting that NMDA-mediated signaling plays a central role in the neural processes disrupted during psychosis. Any explanatory framework must therefore account for why NMDA antagonism produces a conscious but disorganized and miscomputing state rather than simple sedation or isolated salience amplification.

3.12.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), the effects of NMDA antagonists are interpreted as reflecting a direct reduction in effective integrative capacity within neural systems. STM accommodates the observation that blocking NMDA-dependent processes can destabilize cognition and perception by impairing the mechanisms that support temporal integration, contextual binding, and inhibitory coordination. In this framing, NMDA antagonism is treated as functionally analogous to imposing a capacity-reducing perturbation on systems already operating under sensitivity- and load-dependent constraints.

3.12.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

At the microcircuit level, NMDA receptor blockade is conceptually aligned with disruptions in inhibitory interneuron coordination, local network stability, and activity-dependent plasticity, leaving circuits active but less able to support reliable integration over time. At the systems level, such perturbations may weaken coordination among prefrontal, hippocampal, thalamic, and default-mode networks, reducing contextual anchoring and long-range coherence. From a computational perspective, STM frames these effects as degradation of precision weighting and belief updating processes, resulting in unstable inference despite preserved arousal and sensory input.

Behaviorally, this pattern is consistent with the emergence of hallucinations, delusions, disorganization, affective flattening, and dissociative experiences under NMDA antagonism. Individuals with lower baseline integrative capacity or higher cumulative load are framed as operating closer to instability thresholds and may therefore exhibit stronger psychotomimetic responses at lower doses, whereas greater regulatory reserve may confer partial resistance.

3.12.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that individual differences in NMDA-dependent plasticity, inhibitory coordination, or baseline capacity may predict sensitivity to NMDA antagonist effects. It further suggests that electrophysiological measures of network coordination—such as gamma-band synchrony or frontoparietal coherence—may show rapid disruption following NMDA blockade, and that elevated sensory, inflammatory, or allostatic load could amplify these effects. Interventions that enhance inhibitory coordination or reduce background load may therefore be examined for their potential to modulate vulnerability to NMDA antagonist–induced psychosis-like states.

3.13. Core Finding 13 – Psychosocial Interventions as Load–Capacity Modulators

3.13.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Psychosocial interventions—including family psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis (CBTp), cognitive remediation, and social skills training—are associated with small-to-moderate but reliable improvements across several outcome domains. Family psychoeducation is linked to reduced relapse risk [

72], CBTp to modest reductions in symptom-related distress and positive symptoms [

73], cognitive remediation to improvements in cognitive performance and functional outcomes [

74,

75], and social skills training to gains in social and occupational functioning [

75]. These effects occur despite the absence of direct dopaminergic modulation, indicating that their therapeutic impact operates through broader system-level processes rather than through primary neurotransmitter correction.

3.13.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), psychosocial interventions are interpreted as influencing psychosis risk and course by modulating cumulative load and effective capacity, thereby altering proximity to instability thresholds. STM accommodates the observation that non-pharmacological interventions can meaningfully affect outcomes by reshaping environmental demands, internal regulatory processes, and cognitive resources, without invoking disorder-specific molecular mechanisms.

3.13.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Family-based interventions are conceptually aligned with reductions in chronic psychosocial load through decreases in expressed emotion, interpersona threat, and environmental unpredictability, thereby lowering sustained stress on salience and regulatory systems. CBT for psychosis is framed as reducing internal cognitive-emotional load by modifying maladaptive interpretations, weakening excessive salience assigned to intrusive experiences, strengthening higher-order contextual beliefs, and enhancing metacognitive monitoring. Cognitive remediation is interpreted as augmenting effective capacity by improving working memory, attentional control, and executive buffering, which may increase tolerance to cumulative load. Social skills training is aligned with reductions in social and emotional load by increasing predictability, controllability, and confidence in interpersonal contexts, thereby decreasing the computational demands imposed by complex social environments.

Within STM, these interventions are understood to act on different components of the sensitivity–load–capacity relationship, contributing to increased regulatory margins and more stable system operation without directly altering underlying sensitivity traits.

3.13.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that individuals exposed to elevated psychosocial load may show greater benefit from interventions that reduce environmental stressors, such as family-based treatments. It further suggests that gains from cognitive remediation may correspond to measurable changes in executive efficiency or regulatory reserve, and that reductions in sleep disruption, social threat, or emotional volatility may be associated with lower relapse risk. Combined pharmacological and psychosocial approaches may therefore be examined for complementary effects arising from simultaneous modulation of salience-related signaling, cumulative load, and effective capacity, particularly in individuals with higher baseline sensitivity.

3.14. Core Finding 14 – Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Outcome Trajectories

3.14.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Across large international cohorts, longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is consistently associated with poorer long-term outcomes. Prolonged DUP predicts greater persistence of positive symptoms and higher relapse rates [

76], more pronounced negative symptoms and poorer cognitive and functional recovery [

77], and worse social and occupational functioning (77-78]. These associations remain evident even after accounting for baseline illness severity [

76,

78]. This association indicates that the timing of intervention has substantial prognostic relevance and constrains theoretical accounts of illness progression.

3.14.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), DUP is interpreted as prolonged exposure to a state of elevated load and reduced regulatory stability following threshold crossing, rather than as a neutral passage of time. STM accommodates the observation that once psychosis emerges, ongoing symptoms may themselves contribute additional cognitive, emotional, physiological, and social demands. In this framing, untreated psychosis is situated as a period during which system instability may persist and interact with existing sensitivity and capacity constraints, influencing longer-term trajectories.

3.14.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Following threshold crossing, psychotic experiences are conceptually aligned with sustained salience dysregulation, heightened threat processing, executive strain, autonomic arousal, and sleep disruption. These features are treated as contributors to cumulative load that may operate concurrently with reductions in effective capacity. Sleep disturbance, for example, can increase physiological load and limit restorative processes; persistent hypervigilance and paranoia may elevate emotional and autonomic demand; social withdrawal and conflict may reduce external regulatory support; and intrusive perceptual or cognitive experiences may impose continuous attentional and predictive demands. Maladaptive coping strategies, including substance use or avoidance, may further modify load and capacity over time.

Prolonged residence in this destabilized regime is interpreted within STM as potentially shaping learning and adaptation processes. Extended periods of noisy or unstable inference may be associated with reinforcement of rigid threat-related expectations, reduced flexibility in regulatory circuits, and diminished executive reserve. These changes are framed as gradual shifts in system properties rather than as fixed damage, influencing how readily stability can be re-established and how close the system operates to threshold in the future.

3.14.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that shorter DUP may be associated with better outcomes because earlier stabilization limits exposure to sustained high-load conditions and preserves regulatory reserve. It further suggests that early restoration of sleep, reduction of physiological and psychosocial stress, and re-engagement with supportive social contexts may mitigate longer-term destabilization. Longitudinal studies may therefore examine whether markers of cumulative load, regulatory capacity, or learning rigidity mediate the relationship between DUP and outcome, providing avenues for future empirical evaluation.

3.15. Core Finding 15 – Elevated Suicide Risk as Load–Capacity–Prediction Failure

3.15.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Individuals with schizophrenia have a substantially elevated lifetime risk of suicide, estimated at approximately 4.9%, with risk peaking in the early years following illness onset and remaining elevated even outside major depressive episodes [

79,

80,

81]. Suicide risk has been associated with subjective distress, cognitive burden, perceived loss of control, and symptom destabilization, as well as with greater insight in some contexts. These patterns indicate that suicidality in schizophrenia cannot be fully accounted for by depression or command hallucinations alone.

3.15.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), suicidality is interpreted as emerging under conditions of extreme system strain, characterized by high cumulative load and markedly reduced effective capacity for regulation and prediction. STM accommodates the observation that early psychosis represents a period in which multiple load sources converge while regulatory and metacognitive resources are simultaneously compromised. In this framing, suicidal ideation is situated as a downstream consequence of how future states are inferred under conditions of instability, rather than as a primary affective syndrome.

3.15.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

During early illness phases, elevated load may arise from perceptual disruption, threat misattribution, autonomic arousal, sleep disturbance, and abrupt functional decline, while effective capacity for executive control, emotional regulation, and metacognitive monitoring is reduced. STM frames this imbalance as increasing uncertainty in predictive systems, leading to future-oriented models dominated by anticipated persistence of intolerable load and limited perceived avenues for recovery. Importantly, perceived capacity may decline more rapidly than underlying biological capacity, as unstable self-models and noise-driven inference amplify expectations of failure or loss of agency.

In this context, greater insight may transiently intensify distress by increasing awareness of impairment before compensatory strategies or regulatory support are established. Persistent internal threat signals, social withdrawal, stigma, and isolation may further elevate background load and reinforce maladaptive expectations. Within STM, suicidal ideation is therefore interpreted as an inferred response to predicted trajectories under conditions of sustained instability, rather than as an isolated symptom or discrete motivational state.

3.15.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that suicide risk may be most closely associated with markers of cumulative load, perceived regulatory capacity, and future-oriented predictive instability rather than with mood symptoms alone. It further suggests that early interventions that reduce perceptual and autonomic load, restore sleep and executive coherence, and re-establish social and environmental predictability may mitigate risk by stabilizing predictive processes. Longitudinal studies may examine whether changes in perceived capacity and future expectation mediate the relationship between early psychosis and suicidality, providing avenues for empirical evaluation.

3.16. Core Finding 16 – Structural Microcircuit Vulnerabilities as Capacity Constraints

3.16.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Schizophrenia is associated with modest but reliable microstructural differences, including reduced dendritic spine density on layer III pyramidal neurons in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) [

82,

83], atypical hippocampal cytoarchitecture involving altered layering and interneuron distribution [

84], reduced neuropil volume [

85,

86], and subtle long-range connectivity inefficiencies [

87]. These alterations do not reflect neuronal loss or classical neurodegeneration [

84,

88], but they preferentially affect integrative hubs supporting working memory, contextual processing, and predictive regulation. Despite their small magnitude, such differences are consistently observed and have disproportionate functional relevance.

3.16.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), these microstructural findings are interpreted as fixed constraints on effective processing capacity rather than as markers of progressive damage. STM accommodates the observation that stable, developmentally determined circuit features can influence how much regulatory reserve is available to maintain coherent internal representations under load. In this framing, structural vulnerabilities are treated as background parameters that shape proximity to instability thresholds, without implying inevitability of dysfunction.

3.16.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Reduced dendritic spine density in prefrontal pyramidal neurons is conceptually aligned with diminished recurrent excitation and weaker attractor stability, which may limit the robustness of working memory and executive control under increasing cognitive or emotional demand. Similarly, atypical hippocampal microarchitecture—particularly when inhibitory interneuron coordination is altered—can be interpreted as reducing precision in contextual encoding and pattern separation [

84,

89]. Within STM, these features correspond to a lower effective capacity for stabilizing representations and filtering internally generated noise.

At a systems level, such constraints may narrow the range over which regulatory mechanisms can accommodate fluctuations in sensitivity and load. From a computational perspective, reduced structural reserve is framed as increasing susceptibility to representational imprecision and prediction-error amplification when demands rise, rather than as causing constant dysfunction. Clinically, this interpretation is consistent with fragile working memory, impaired contextual tracking, and vulnerability to disorganization or salience misassignment under stress, while allowing for stable function under lower-load conditions.

3.16.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that microstructural measures related to prefrontal and hippocampal organization may correlate with performance under high-demand cognitive conditions more strongly than with baseline functioning. It further suggests that markers of excitatory–inhibitory coordination or representational noise may better index functional vulnerability than structural metrics alone, particularly when environmental or cognitive load increases. Longitudinal studies may therefore examine whether interactions between microstructural constraints and cumulative load predict variability in symptom expression or conversion risk over time.

3.17. Core Finding 17 – Inhibitory Circuit Fragility as a Core Capacity Constraint

3.17.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Schizophrenia is consistently associated with molecular and cellular alterations in inhibitory interneuron systems, including reduced expression of GAD67 and Reelin and functional impairment of parvalbumin-positive (PV+) GABAergic interneurons across the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and related cortical regions [

8,

90,

91,

92]. These alterations are linked to weakened inhibitory postsynaptic signaling, disrupted gamma-band oscillations, altered excitatory–inhibitory balance, reduced temporal precision, and instability in microcircuit synchronization [

93,

94,

95]. Among neurobiological findings in schizophrenia, inhibitory circuit differences are among the most robust and consistently reported.

3.17.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), inhibitory interneuron systems are interpreted as central contributors to effective processing capacity. STM accommodates the view that GABAergic circuits support temporal coordination, noise suppression, predictive gating, and stabilization of neural representations. In this framing, alterations in inhibitory function are not treated as disease-specific triggers but as constraints that shape how much load a system can tolerate while maintaining stable operation.

3.17.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Reduced GAD67 and Reelin expression are conceptually aligned within STM with diminished inhibitory synthesis and altered interneuron connectivity, which may limit the effectiveness of PV+ interneurons in constraining pyramidal cell activity. This reduction in inhibitory precision can be interpreted as lowering the robustness of gamma-band synchronization, a process implicated in information binding, working memory maintenance, and temporal coding. Within STM, such changes are framed as contributing to elevated baseline internal noise and reduced regulatory reserve, effectively narrowing the margin between stable operation and instability.

At the network level, inhibitory fragility is interpreted as impairing the system’s ability to filter sensory and internally generated signals. Reduced gating efficiency and less stable attractor dynamics may allow amplified or noisy inputs to propagate more readily, particularly under conditions of increased sensitivity or load. From a computational perspective, this configuration is framed as increasing the likelihood that incremental increases in demand lead to abrupt transitions in system behavior, rather than gradual performance degradation. Clinically, this interpretation is consistent with vulnerability to disorganization, perceptual instability, and salience misassignment under stress, while permitting relatively intact function in low-demand contexts.

3.17.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that measures of inhibitory integrity—such as GAD67 or Reelin expression, electrophysiological indices of sensory gating, or gamma-band synchrony—may relate to indicators of effective capacity and proximity to instability thresholds. It further suggests that individuals with milder inhibitory alterations may remain stable under low-load conditions but show disproportionate sensitivity to added stressors such as sleep disruption, sensory overload, or substance exposure. Interventions that enhance inhibitory coordination, whether pharmacological, cognitive, or neuromodulatory, may therefore be examined for their potential to increase effective capacity and reduce overload-related instability in individuals with prominent inhibitory circuit vulnerability.

3.18. Core Finding 18 – Subtle Macrostructural Reductions as Capacity Constraints

3.18.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Schizophrenia is consistently associated with modest macrostructural differences, including slightly enlarged ventricles and small reductions in total brain volume as well as gray- and white-matter volume, typically on the order of 1–3% [

96,

97,

98]. These differences are often present prior to first-episode psychosis, observed in antipsychotic-naïve individuals, and remain relatively stable over the course of illness [

96,

99,

100]. Although subtle and non-progressive, they represent some of the most robust structural findings reported in schizophrenia.

3.18.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), such macrostructural differences are interpreted as reflecting developmental constraints on effective processing capacity rather than evidence of neurodegeneration. STM accommodates the observation that stable anatomical features can shape the upper limits of integrative and regulatory function, thereby influencing how close an individual operates to instability thresholds under everyday conditions. In this framing, macrostructural variation sets boundary conditions for system performance without directly determining symptom expression.

3.18.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Mild reductions in cortical or hippocampal gray matter are conceptually aligned within STM with constraints on neuropil available for contextual integration, representational stability, and error correction. These constraints may lower the fidelity of internal predictive models and increase baseline processing demand, thereby consuming capacity even in the absence of acute stressors. Subtle white-matter inefficiencies and ventricular enlargement are interpreted as reflecting limitations in integrative bandwidth and temporal coordination across distributed circuits [

98,

101]. Together, these features may narrow the range over which neural systems can flexibly coordinate sensory, cognitive, and emotional information.

At a dynamical level, STM frames these architectural constraints as reducing stability margins, such that systems function adequately under low-load conditions but approach instability more rapidly as sensitivity-weighted load increases. This interpretation provides a conceptual account of how stable macrostructural features can coexist with fluctuating clinical states, as symptom emergence depends on interactions with load and sensitivity rather than on progressive structural change.

STM further allows for the possibility that modest macrostructural reductions reflect developmental trade-offs in representational architecture rather than uniform loss of function. More compact neural organization may support efficient associative encoding and rapid synaptic refinement, while simultaneously reducing redundancy, error-correction capacity, and reserve. In this framing, reduced anatomical volume need not imply impaired baseline performance, but rather diminished tolerance to sustained or complex load, consistent with preserved functioning under low-demand conditions and increased vulnerability as demands accumulate.

3.18.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that macrostructural measures may show stronger associations with tolerance to high cognitive or emotional demand than with baseline symptom severity. It further suggests that individuals with greater structural constraints may exhibit steeper performance decline or symptom emergence as load increases, despite stable anatomy over time. Longitudinal studies may therefore examine whether interactions between macrostructural features and cumulative load better predict episodic decompensation than either factor considered independently.

3.19. Core Finding 19 – Region-Specific Volume Reductions as Network-Level Capacity Constraints

3.19.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Neuroimaging studies consistently report modest but reliable volume reductions—typically in the range of 1–5%—in the hippocampus, superior temporal cortex, prefrontal cortex, and thalamus in individuals with schizophrenia [

96,

97,

102,

103]. These differences are often present at or before first episode, observed in antipsychotic-naïve individuals, and show little evidence of progressive decline. Importantly, the affected regions form a coherent functional network involved in contextual processing, sensory filtering, prediction, and integration, rather than a diffuse or random anatomical pattern.

3.19.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), region-specific volume reductions are interpreted as network-level constraints on effective processing capacity within a predictive hierarchy. STM accommodates the observation that small, stable anatomical differences can have disproportionate functional consequences when they affect high-leverage nodes in distributed networks. In this framing, these reductions are not treated as markers of degeneration, but as developmental or early-established architectural features that shape how efficiently predictive and regulatory processes can operate under load.

3.19.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Each of the affected regions occupies a central role in hierarchical inference. The hippocampus contributes to contextual anchoring and pattern separation; the thalamus regulates sensory filtering and routing; the superior temporal cortex supports auditory and language-related prediction; and the prefrontal cortex contributes to working memory maintenance, belief updating, and precision regulation. Modest volume reductions in these regions are conceptually aligned within STM with reduced circuit redundancy, noisier signaling, and less efficient inter-regional coordination at stages where predictive precision is particularly important.

At the systems level, STM frames these changes as producing a distributed bottleneck architecture rather than isolated regional deficits. Imprecise contextual signals, less efficient sensory filtering, and reduced top-down stabilization may interact to narrow overall regulatory margins, even if no single regional alteration is sufficient to produce instability on its own. This configuration is consistent with episodic vulnerability to dysregulation under conditions of increased sensitivity or cumulative load, while allowing for relative stability under lower-demand conditions.

3.19.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that region-specific volume measures may show domain-selective associations with functional performance under stress or ambiguity—for example, hippocampal volume with context-dependent memory demands, superior temporal volume with speech or auditory prediction under load, prefrontal volume with flexibility in belief updating, and thalamic volume with tolerance to sensory complexity. It further suggests that combined reductions across multiple nodes may interact to influence proximity to instability more strongly than any single regional measure alone. Longitudinal and task-based studies may therefore examine how structural constraints interact with load to shape dynamic clinical expression over time.

3.20. Core Finding 20 – Electrophysiological and Functional Network Abnormalities as Dynamic Indicators of Load–Capacity Imbalance

3.20.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Across electrophysiological and functional imaging modalities—including EEG, MEG, fMRI, intracortical recordings, and computational modeling—schizophrenia is associated with a convergent pattern of functional differences. These include reduced mismatch negativity (MMN), reduced P300 amplitude, disrupted gamma- and theta-band oscillations, impaired cross-frequency coupling, sensory gating deficits (P50), and inefficient prefrontal activation that shifts between relative hypo- and hyper-activation depending on task demand [

94,

104,

105,

106,

107]. These findings appear early, persist across illness stages, and map onto alterations in prediction error signaling, attentional updating, sensory filtering, and large-scale network coordination.

3.20.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), these electrophysiological and functional patterns are interpreted as dynamic indicators of how neural systems operate as demands approach or exceed effective processing capacity. STM accommodates the observation that many of these measures vary with task load, physiological state, and environmental context, suggesting sensitivity to system strain rather than fixed deficits. In this framing, electrophysiology provides a window into moment-to-moment stability and coordination of predictive and regulatory processes under varying sensitivity and load conditions.

3.20.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

Reduced MMN is conceptually aligned within STM with diminished efficiency of automatic prediction formation and mismatch detection at early sensory levels, consistent with increased internal noise or reduced precision when capacity is constrained. Reduced P300 amplitude is framed as reflecting limitations in allocating attentional and working-memory resources for belief updating when cumulative demands approach available capacity. Together, these measures suggest that both pre-attentive and higher-order updating processes may be affected as systems operate closer to instability thresholds.

Patterns of inefficient prefrontal activation—characterized by relative over-recruitment at low demand and under-recruitment at high demand—are interpreted as reflecting nonlinear control behavior in capacity-limited systems. Rather than indicating uniform under-functioning, such patterns are consistent with compensatory effort at lower load followed by reduced effectiveness as demand increases. Oscillatory abnormalities, including reduced gamma synchrony, altered theta–gamma coupling, and impaired cross-frequency integration, are framed as disruptions in the temporal coordination required for hierarchical communication among hippocampal, thalamic, prefrontal, and sensory networks. Within STM, these changes are interpreted as markers of reduced temporal precision and coordination under elevated load.

3.20.4. Testable Predictions / Falsifiability Cues (Future Work)

Within this framework, STM suggests that electrophysiological measures may vary systematically with acute and cumulative load, such as sleep disruption, stress, or sensory complexity, rather than serving solely as static correlates of diagnosis. It further suggests that reductions in MMN and P300 may track proximity to capacity limits during task engagement, that prefrontal activation patterns may shift with demand in a manner reflecting compensatory limits, and that alterations in oscillatory coordination may precede overt symptom exacerbation. Longitudinal and task-based studies may therefore examine whether these measures function as dynamic indicators of system stability and threshold proximity under changing load conditions.

3.21. Core Finding 21 – Global Cognitive Impairment as a Marker of Chronic Near-Threshold Operation

3.21.1. Finding (Brief Restatement)

Schizophrenia is associated with broad and relatively stable cognitive differences, averaging approximately one standard deviation below population norms. The largest effects are observed in processing speed, working memory, fluid reasoning, verbal memory, attention and vigilance, cognitive flexibility, and executive function [

59,

108,

109]. These differences often emerge years before the first psychotic episode, frequently during childhood or early adolescence [

7,

110], show limited progression across adulthood [

110,

111], predict functional outcome more strongly than positive symptoms [

112,

113,

114], and show limited responsiveness to antipsychotic treatment [

59,

115].

3.21.2. STM Interpretation (Systems-Level Framing)

Within the Sensitivity Threshold Model (STM), these cognitive patterns are interpreted as reflecting long-standing constraints on effective processing capacity rather than as secondary consequences of acute psychotic episodes. STM accommodates the observation that cognitive differences precede illness onset, remain relatively stable over time, and persist during symptomatic remission. In this framing, cognition is treated as an indicator of how closely neural systems operate to capacity limits under typical levels of sensitivity and load.

3.21.3. Mechanistic Implications (Within Existing STM Constructs)

When sensitivity-weighted load persistently approaches available capacity, STM frames cognitive processing as operating with reduced margin for integration and error correction. Under such conditions, information binding may become less efficient, working memory representations less stable, and long-range coordination more vulnerable to interference. Processing speed is conceptually aligned with global integration bandwidth, as tasks such as digit symbol coding require rapid coordination across perceptual, motor, and executive systems under time pressure. Consistent reductions in such measures are therefore interpreted as reflecting limits on integrative throughput rather than deficits localized to a single cognitive domain.