1. Introduction

Monitoring water quality is essential for public health, environmental conservation, and sustainable development. Continuous and integrated surveillance enables the early detection of risks, contributing to the reduction of infections and associated healthcare costs. In this context, wastewater-based epidemiology has emerged as a powerful tool for tracking and understanding disease outbreaks in real time. Waterborne diseases, caused by pathogenic microorganisms or chemical contaminants present in aquatic environments, remain particularly common in regions with inadequate sanitation infrastructure. Consequently, the identification of microbial indicator organisms is critical for assessing the microbiological quality of water and supporting more effective preventive actions [

1,

2,

3].

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents an escalating threat to global public health. Among the major drivers of this phenomenon is the environmental dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and their associated resistance genes. The release of antibiotics into the environment through domestic and hospital effluents creates critical hotspots of resistance, as previously documented in urban settings such as the Dilúvio Stream in Porto Alegre. Of particular concern is the detection of bacteria producing carbapenemase enzymes (including KPC, NDM, VIM, and OXA-48), which confer resistance to last-line antibiotics. These resistance genes are frequently carried on mobile genetic elements, facilitating their spread across microbial communities and diverse aquatic ecosystems [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Together, these findings underscore the need to evaluate water systems not only for pathogens but also for resistance determinants.

Although viral pathogens were not evaluated in this study, the successful application of molecular surveillance to detect SARS-CoV-2 in Porto Alegre illustrates the broader value of integrating molecular tools into water quality monitoring frameworks [

11,

12,

13,

14]. This example underscores the growing importance of combining microbiological and molecular approaches for comprehensive water surveillance.

The water supply and sanitation system of Porto Alegre serves more than 99.5% of the population and relies on a robust infrastructure that includes Water Treatment Plants (WTP), Raw Water Pumping Stations (REPS), Treated Water Pumping Stations (TWPS), and multiple reservoirs. Approximately 80% of the wastewater produced in the city undergoes treatment [

15,

16]. However, assessing water quality requires going beyond the physicochemical and microbiological parameters defined by current regulations. In particular, conventional monitoring may overlook emerging biological hazards that persist even in treated water.

Molecular methods such as qPCR offer enhanced sensitivity and specificity for detecting antimicrobial resistance genes, including carbapenemase-encoding loci such as KPC, NDM, IMP, VIM, and OXA-type variants [

17,

18,

19]. These techniques allow the detection of resistance determinants that may persist in the environment even when cultivable bacteria are absent, highlighting gaps in traditional microbiological monitoring [

20]. The incorporation of molecular assays into water quality surveillance therefore strengthens early detection of emerging resistance risks [

21]. However, such tools are still not routinely implemented in urban water monitoring programs.

Microbiological monitoring of water quality traditionally relies on the detection of cultivable indicator organisms, a strategy that does not account for the presence of viable but non-culturable bacteria or antimicrobial resistance genes [

22,

23]. Urban aquatic environments have increasingly been recognized as reservoirs of these genetic determinants, even when treated water meets established bacteriological standards [

22]. In particular, genes associated with carbapenem resistance represent an emerging concern for both public health and environmental microbiology [

19]. Integrating classical microbiological methods with quantitative molecular approaches can enhance the sensitivity of water quality surveillance, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of these systems [

24]. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to investigate the spatial distribution and seasonal trends in the occurrence of carbapenem resistance genes, aiming to identify hotspots and periods of increased incidence while using microbiological results and the Water Quality Index as complementary interpretive tools.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Sampling Points

The study was conducted over a one-year period in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, with sampling carried out across four climatic seasons (winter, spring, summer, and fall) to assess seasonal variability. Detailed information regarding the identification of samples, geographic coordinates, and characteristics of the sampling points is presented in

Table 1.

Raw (untreated) water samples were collected at two sites in Guaíba Lake: one located in the northern region, near the Moinhos de Vento Raw Water Pumping Station (EBAB Moinhos de Vento), and another in the southern region, near the Belém Novo Raw Water Pumping Station (EBAB Belém Novo). These sites correspond to the sampling points RLN and RLS, respectively.

Treated (potable) water samples were collected at two public squares supplied by distinct water distribution systems. One sampling point was located in the Moinhos de Vento neighborhood (TPN), supplied by the Moinhos de Vento Water Treatment Plant (WTP Moinhos de Vento), and the other in the Belém Novo neighborhood (TPS), supplied by the Belém Novo Water Treatment Plant (WTP Belém Novo).

Raw water samples were collected by the State Environmental Protection Foundation (FEPAM), while treated water samples were collected by the National Service for Industrial Training (SENAI). Sampling followed a seasonal schedule, with four quarterly campaigns conducted from winter 2024 to summer 2025, resulting in a total of 15 samples. After collection, all samples were kept refrigerated during transport and until laboratory processing.

The following methodological considerations apply: (i) For raw water samples, a portion of the physicochemical data was provided by FEPAM, as these analyses were performed in situ. (ii) For molecular assays targeting antimicrobial resistance genes, samples were sent to the SENAI microbiology laboratory, where they underwent a filtration step as detailed in a subsequent section.

2.2. Physicochemical Analyses

Dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, and temperature were measured in situ using a ProDSS multiparameter water quality meter (YSI–Xylem). All remaining analyses were performed at the SENAI Physicochemical Laboratory following standardized methodologies for each parameter: chloride (Method 4110 B), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD₅, Method 5210 D), phosphate (Method 4110 B), nitrate (Method 4110 B), total solids (Method 2540 B), and turbidity (Method 2130 B) [

25].

2.3. Microbiological Analyses

Microbiological analyses for total coliforms, thermotolerant coliforms,

Escherichia coli, and heterotrophic bacteria counts were performed at the SENAI Microbiology Laboratory following standard methodologies: thermotolerant coliforms (Methods 9221 B and 9221 E), total coliforms and

E. coli (Method 9223 B), and heterotrophic plate counts (Methods 9215 A and 9215 B) [

25].

2.4. Water Quality Index (WQI) Determination

To determine the Water Quality Index (WQI), the following parameters were evaluated: water temperature, chlorides, sampling site altitude, dissolved oxygen, fecal coliforms, pH, BOD₅, nitrate, phosphate, turbidity, and total solids. The criteria used for WQI calculation are primarily indicators of contamination from domestic sewage discharge as well as industrial, agricultural, and urban solid waste effluents [

26]. Each parameter is associated with a specific weighting factor and a standardized rating curve.

2.5. Interpretation of Physicochemical and Microbiological Analyses

The interpretation of physicochemical and microbiological results was based on current Brazilian environmental and sanitary regulations. For raw water samples, the reference standard was CONAMA Resolution No. 357/2005, which classifies water bodies and establishes environmental guidelines and effluent discharge limits. According to this resolution, Guaíba Lake is classified as a freshwater body (salinity ≤ 0.5%) of Class 2, suitable for human consumption after conventional treatment [

27].

For treated water, the analysis followed Ministry of Health Ordinance GM/MS No. 888/2021, which establishes procedures for the control and surveillance of drinking water quality. Parameters not included in this ordinance were evaluated according to the Consolidation Ordinance No. 5/GM/MS, issued on September 28, 2017 [

28,

29].

2.6. Detection of Carbapenem Resistance Genes

Water samples were filtered using hydrophilic PTFE membranes (0.45 µm, 47 mm; Filtrilo®) under vacuum (Millipore system) at the SENAI Microbiology Laboratory. For raw water samples, 350 mL were filtered per membrane, whereas 1 L was filtered for treated water samples. Each sampling site was processed in biological triplicate.

Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerWater Kit (Qiagen

®). DNA quality, concentration, and integrity were assessed by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop™), fluorometry (Qubit™), and agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA amplifiability was confirmed by conventional PCR targeting the

16S rRNA gene [

30]. All samples were retained for analysis regardless of initial DNA quality.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays were performed in technical triplicate using the StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System with PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primers targeting the

IMPa,

KPC,

NDM,

OXA-48, and

VIM genes were selected based on previously published studies [

31]. Standard curves (10¹⁰–10⁵ copies/µL) were generated from serial dilutions in technical triplicate to determine amplification efficiency (E = 10^(−1/slope)) and enable absolute quantification. Specificity was confirmed by melting curve analysis. Ct thresholds were adjusted manually, and samples with high variability (SD > 0.5) were retested as part of quality control procedures.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Analyses

The results of the physicochemical analyses of raw and treated water samples, along with the corresponding reference values, are shown in

Table 2.

For raw water samples, the only parameter exceeding the limits established by the Brazilian National Environmental Council (CONAMA) Resolution No. 357/2005 was biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) in the BBN–spring sample (13 mg/L), indicating an elevated organic load. BOD reflects the amount of oxygen required for microbial decomposition of organic matter in aquatic environments, and elevated values may arise from natural organic inputs, increased microbial activity, or the discharge of domestic, industrial, or agricultural effluents. Environmental variables—including pH, temperature, and nutrient enrichment—may also influence BOD dynamics [

32,

33]. When this finding was examined in conjunction with the other physicochemical parameters at the same site, the deviation appeared to be isolated and was most likely associated with high concentrations of natural organic matter such as leaves, branches, plant debris, and organic-rich sediments.

For treated water samples, pH values at the TMV sampling point remained below the acceptable regulatory range across all sampling periods, with a mean value of 5.57. At the TBN site, the winter sample presented a pH of 5.49, while the remaining samples were close to the lower limit of acceptability (6.03). Overall, these results indicate slight acidity in the treated water, suggesting insufficient pH adjustment during the treatment process. Considering that raw water at these locations exhibited mean pH values of 7.08 (TMV) and 7.34 (TBN), the marked decrease observed after treatment suggests ineffective pH correction. This pattern may reflect operational issues in the treatment system, such as inadequate dosing of alkalinizing agents or excessive application of acidic coagulants, which can disrupt chemical stability in the final water supplied to consumers [

32,

34].

Contextual factors should also be considered for the TMV–winter sample. In August 2024, the Moinhos de Vento Water Treatment Plant underwent an emergency shutdown to repair a major water pipeline, affecting water supply to 21 neighborhoods in Porto Alegre. Although plant operations resumed in early September, coinciding with the sampling period, water distribution was still being gradually reestablished. According to guidance from the municipal water authority, prolonged service interruptions may mobilize sediments within the distribution network, temporarily altering water color and taste. While such particles are generally considered harmless, their mobilization may have contributed to the physicochemical variability observed during this sampling event.

3.2. Microbiological Analyses

The results of the microbiological analyses are presented in

Table 3.

To assess hygienic quality, total coliforms and heterotrophic bacteria were quantified. These microbial groups are naturally present in the environment, including soil, vegetation, and aquatic ecosystems, and their occurrence may indicate general environmental contamination [

1]. Although there are no specific regulatory limits for raw water, these measurements provide a useful estimate of the overall microbiological condition of the sampled sites. For treated water, however, both parameters serve as indicators of potential failures in disinfection or deficiencies within the distribution system. As observed, all treated water samples complied with the limits established by current Brazilian regulations [

27,

28,

29], demonstrating the effectiveness of the treatment processes in place.

Sanitary quality was evaluated through the detection of thermotolerant coliforms and Escherichia coli. The presence of these microorganisms indicates recent fecal contamination, with E. coli functioning as a more specific marker of high sanitary risk and potential pathogen presence [

1]. In raw water samples, thermotolerant coliform counts exceeded the permitted limits only at the BMV sampling point during winter and spring, suggesting episodic fecal contamination events at this site.

Regarding E. coli, Brazilian Resolution CONAMA No. 357/2005 [

27] authorizes its use as a surrogate marker for thermotolerant coliforms, provided its concentration does not exceed 80% of the total. Although its presence strongly indicates recent fecal pollution, relying solely on E. coli may limit interpretive depth when thermotolerant coliform quantification is available. As expected for effectively treated water, E. coli was not detected in any treated water samples across all sampling periods, further supporting the efficacy of disinfection processes and the protection of the distribution system.

Overall, both water treatment systems evaluated (TMV and TBN) effectively removed fecal contamination and sanitary indicator organisms. Even in instances where raw water exhibited elevated microbial counts, as observed during winter at the BMV site, the corresponding treated water samples (e.g., TMV–winter) demonstrated complete absence of indicator microorganisms. These results confirm the satisfactory microbiological performance of the treatment operations throughout the study period.

3.3. Determination of the Water Quality Index (WQI)

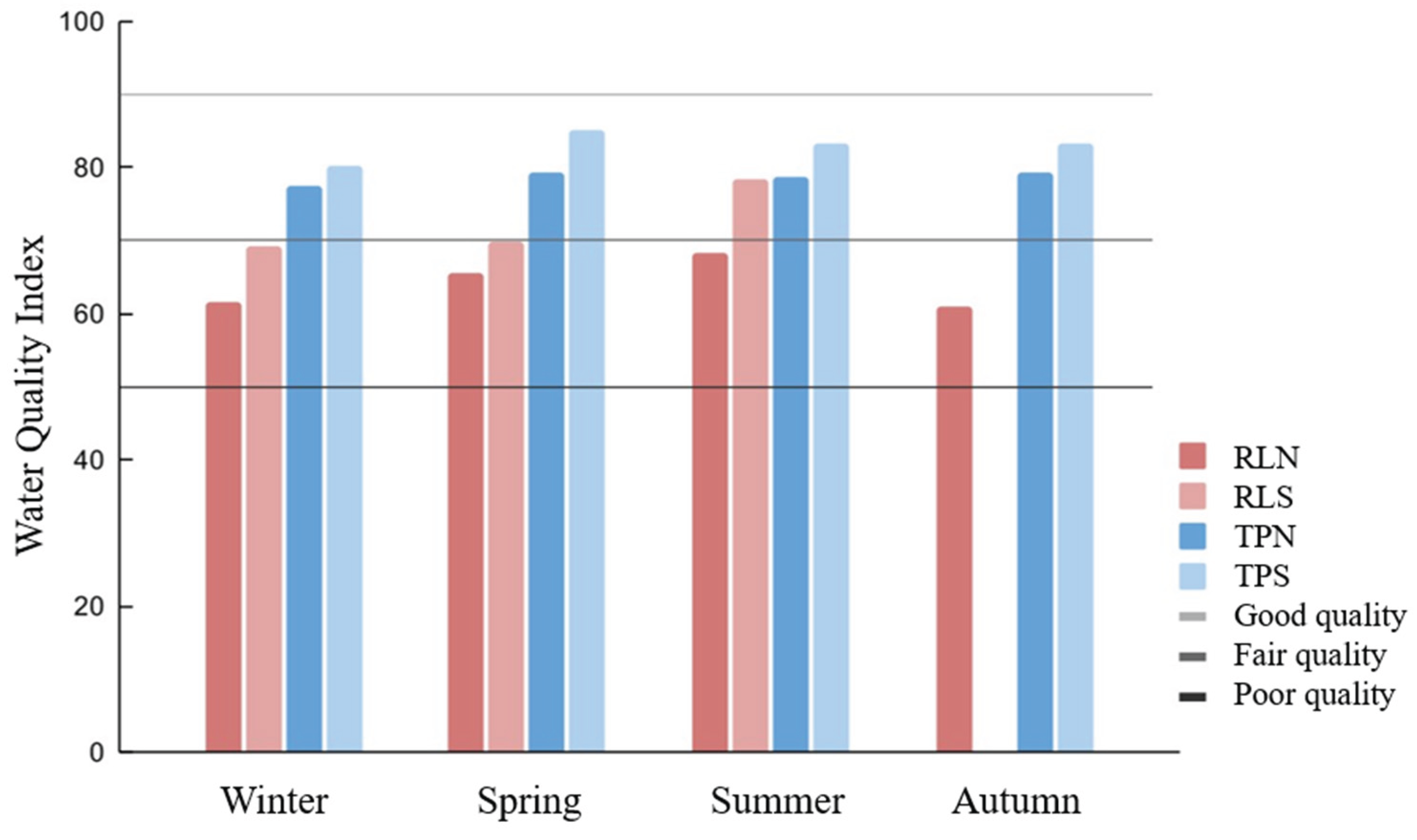

The analysis of the Water Quality Index (WQI) provided an integrated assessment of the environmental condition of raw and treated water samples across the four seasons (

Figure 1).

The criteria used for WQI calculation are primarily based on indicators of contamination associated with domestic sewage discharge, as well as industrial, agricultural, and urban solid waste effluents [

35]. Although WQI determination is not a regulatory requirement for treated water, its inclusion in this study served as a complementary approach, enabling a quantitative and integrative comparison of water quality before and after treatment.

For treated water samples, WQI values reflected the efficiency of treatment processes, with marked reductions in critical parameters such as turbidity, organic matter, coliforms, and nutrient concentrations. These improvements, combined with the stabilization of physicochemical variables that negatively influence environmental quality, reinforce the overall effectiveness of the applied treatment systems.

In contrast, raw water samples exhibited seasonal variation, with higher WQI values observed during summer. This trend may be associated with more favorable hydrological and environmental conditions typical of this period, such as increased solar radiation, elevated temperatures, and enhanced microbial inactivation, which together promote reductions in turbidity and fecal contamination indicators [

36,

37]. Such seasonal improvement is consistent with known patterns in subtropical lake systems, where climatic dynamics strongly influence water quality parameters.

3.4. Detection of Carbapenem Resistance Genes

The results of the molecular analyses are presented in

Table 4.

Recurrent detection of the blaOXA-48-like gene was observed at all raw and treated water sampling points across most seasons. During autumn, a simultaneous occurrence of three carbapenem resistance genes (blaOXA-48-like, blaKPC, and blaNDM) was detected at the RLN sampling site, with notably high copy numbers. The blaVIM gene appeared exclusively in spring, whereas no antimicrobial resistance genes were detected during the summer. The blaIMPa gene was not detected in any sample. This seasonal pattern may reflect fluctuations in antibiotic usage, hospital discharge dynamics, or environmental stability of the genetic material, all of which merit further investigation.

Urban aquatic environments are recognized reservoirs of multidrug-resistant bacteria and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs), primarily due to inputs from domestic sewage, hospital effluents, and diffuse urban sources that select and disseminate ARGs within aquatic systems [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Among the five epidemiologically relevant carbapenemase genes investigated (

blaKPC,

blaIMPa,

blaNDM,

blaVIM,

blaOXA-48-like),

blaOXA-48-like was the most prevalent, with consistent detection across sites and seasons in both raw and treated water. This pattern suggests high environmental persistence and continuous introduction from anthropogenic sources, aligning with findings from recreational waters, freshwater bodies, and drinking water systems worldwide [

42,

43,

44].

The genes

blaVIM,

blaKPC, and

blaNDM were detected sporadically, with isolated events primarily in spring and autumn. The simultaneous detection of three carbapenemase genes during autumn indicates a potential episodic contribution of wastewater, consistent with irregular discharges or increased domestic and hospital inputs reported in other urban systems [

39,

45]. The exclusive detection of

blaVIM in spring, combined with the absence of

blaIMPa, suggests low regional prevalence of some carbapenemase families or an absence of significant emission sources during the monitoring period [

41].

A clear seasonal influence was observed: the complete absence of ARGs in summer may be related to environmental conditions such as increased dilution, higher temperatures, and enhanced solar radiation, all of which accelerate DNA degradation and reduce bacterial persistence [

46]. In contrast, spring represented the period of greatest detection frequency, including occurrences in treated water samples that otherwise met bacteriological criteria. This underscores limitations of monitoring strategies based exclusively on cultivable indicator organisms.

The detection of ARGs in treated water despite the absence of cultivable coliforms suggests the persistence of extracellular DNA (eDNA) or viable but non-culturable (VBNC) bacteria, phenomena well documented in drinking water and wastewater treatment systems [

45,

47]. Although chlorination is effective at microbial inactivation, it does not fully degrade free DNA, allowing ARGs to persist post-treatment [

48]. Advanced technologies, such as combined ultraviolet radiation and hydrogen peroxide, have demonstrated superior efficiency in degrading extracellular genetic material [

49]. Therefore, even treatment systems that successfully meet microbiological standards may remain reservoirs of resistance genes with potential for horizontal gene transfer, reinforcing the need to integrate molecular-based surveillance into routine water quality monitoring [

50].

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that carbapenem resistance genes can be detected in urban aquatic systems even when treated water complies with conventional bacteriological standards. The recurrent occurrence of the blaOXA-48-like gene in both raw and treated water, together with the seasonal detection of blaVIM, highlights the environmental persistence of clinically relevant resistance determinants and their temporal variability. The absence of resistance genes during summer and their restricted detection in specific seasons and sampling points indicate the influence of environmental and operational factors on their occurrence and stability.

The detection of resistance genes in treated water in the absence of cultivable coliforms underscores the limitations of traditional microbiological monitoring and reinforces the value of molecular approaches as complementary tools for water quality surveillance. Integrating microbiological indicators, molecular data, and physicochemical parameters enables a more comprehensive understanding of antimicrobial resistance dynamics in urban aquatic environments.

Overall, the findings contribute to environmental microbiology by emphasizing the importance of incorporating molecular-based monitoring into routine surveillance programs and supporting the adoption of a One Health approach to better address the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in interconnected environmental, human, and animal systems. Collectively, these results highlight the strategic value of integrating molecular surveillance into national drinking water monitoring programs, strengthening early detection and risk mitigation efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H., T.M.M., and F.S.C.; Methodology, L.H., and T.M.M.; Validation, L.H., T.M.M., and L.C.T.; Formal analysis, L.H. and T.M.M.; Investigation, L.H. and T.M.M.; Resources, L.C.T., H.M.J., A.A.S., F.S.C.; Data curation, L.H. and T.M.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, L.H. and T.M.M.; Writing-review and editing, T.M.M., A.A.S., and F.S.C.; Supervision, A.A.S. and F.S.C.; Project administration, A.A.S., T.M.M. and F.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No publicly archived datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by SENAI. The authors also thank FEPAM, Agrega Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Biotecnologia Ltd.a., and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) for their institutional partnership and technical collaboration. F.S.C. is CNPq research fellow.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fundação Nacional de Saúde (FUNASA). Manual Prático de Análise de Água, 4th ed.; Coordenação de Comunicação Social: Brasília, Brazil, 2013. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/analise_agua_bolso.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Franco, B.D.G. de M.; Landgraf, M. Microbiologia de Alimentos; 1st ed.; Editora Atheneu: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2008.

- Secretaria Estadual de Saúde de São Paulo (SES/SP). Doenças Relacionadas à Água ou de Transmissão Hídrica: Perguntas e Respostas e Dados Estatísticos; São Paulo, Brazil, 2009. Available online: https://www.saude.sp.gov.br/resources/cve-centro-de-vigilancia-epidemiologica/areas-de-vigilancia/doencas-transmitidas-por-agua-e-alimentos/doc/2009/2009dta_pergunta_resposta.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Hu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Sun, X.; Wu, J.; Ma, L.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, K.; Luo, Y.; Cui, C. Risk assessment of antibiotic resistance genes in the drinking water system. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149650. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.L.; et al. Multiplex detection of the big five carbapenemase genes using solid-phase recombinase polymerase amplification. Analyst 2024, 149, 1527–1536. [CrossRef]

- Hanna, N.; Tamhankar, A.J.; Stålsby Lundborg, C. Antibiotic concentrations and antibiotic resistance in aquatic environments of the WHO Western Pacific and South-East Asia regions: A systematic review and probabilistic environmental hazard assessment. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e45–e54. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Antibacterial Agents in Clinical Development: An Analysis of the Antibacterial Clinical Development Pipeline; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240000193 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Sanganyado, E.; Gwenzi, W. Antibiotic resistance in drinking water systems: Occurrence, removal, and human health risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 785–797. [CrossRef]

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Resistência Antimicrobiana é Ameaça Global; 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/noticias-anvisa/2019/resistencia-antimicrobiana-e-ameaca-global-diz-oms (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Ministério da Saúde. Plano de Ação Nacional de Prevenção e Controle da Resistência aos Antimicrobianos no Âmbito da Saúde Única 2018–2022 (PAN-BR); Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2018. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/plano_prevencao_resistencia_antimicrobianos.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Hegarty, B.; Dai, Z.; Raskin, L.; Pinto, A.; Wigginton, K.; Duhaime, M. A Snapshot of the Global Drinking Water Virome: Diversity and Metabolic Potential Vary with Residual Disinfectant Use. Water Res. 2022, 218, 118484. [CrossRef]

- Aschidamini Prandi, B.; Mangini, A.T.; Santiago Neto, W.; Jarenkow, A.; Violet-Lozano, L.; Campos, A.A.S.; Colares, E.R.D.C.; Buzzetto, P.R.O.; Azambuja, C.B.; Trombin, L.C.B.; Raugust, M.S.; Lorenzini, R.; Larre, A.D.S.; Rigotto, C.; Campos, F.S.; Franco, A.C. Wastewater-Based Epidemiological Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 in Porto Alegre, Southern Brazil. Sci. One Health 2023, 1, 100008. [CrossRef]

- Chapron, C.D.; Ballester, N.A.; Fontaine, J.H.; Frades, C.N.; Margolin, A.B. Detection of Astroviruses, Enteroviruses, and Adenovirus Types 40 and 41 in Surface Waters Collected and Evaluated by the Information Collection Rule and an Integrated Cell Culture-Nested PCR Procedure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 2520–2525. [CrossRef]

- Prado, T.; Miagostovich, M.P. Virologia ambiental e saneamento no Brasil: Uma revisão narrativa. Cad. Saúde Pública 2014, 30, 1367–1378. [CrossRef]

- DMAE. Informações sobre a água. Departamento Municipal de Água e Esgotos de Porto Alegre. Available online: https://prefeitura.poa.br/dmae/informacoes-agua (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- DMAE. Informações educação ambiental – Informações sobre o esgoto, o tratamento e os cuidados. Departamento Municipal de Água e Esgotos de Porto Alegre. Available online: https://prefeitura.poa.br/sites/default/files/usu_doc/sites/dmae/Folder%20%C3%A1gua%20-%20compressed%20(1).pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; Vandesompele, J.; Wittwer, C.T. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Osborn, A.M. Advantages and limitations of quantitative PCR (Q-PCR)-based approaches in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 67, 6–20. [CrossRef]

- Manaia, C.M.; Macedo, G.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Nunes, O.C. Antibiotic resistance in urban aquatic environments: Can it be controlled? Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 1543–1557. [CrossRef]

- Paruch, L. Molecular Diagnostic Tools Applied for Assessing Microbial Water Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5128. [CrossRef]

- Rompré, A.; Servais, P.; Baudart, J.; de-Roubin, M.R.; Laurent, P. Detection and Enumeration of Coliforms in Drinking Water: Current Methods and Emerging Approaches. J. Microbiol. Methods 2002, 49, 31–54. [CrossRef]

- Abebe, T.A.; Gebreyes, D.S.; Abebe, B.A.; Yitayew, B. Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Resistance Genes in Drinking Water Source in North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1422137. [CrossRef]

- Caliskan-Aydogan, O.; Alocilja, E.C. A Review of Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacterales and Its Detection Techniques. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1491. [CrossRef]

- Paruch, L. Molecular Diagnostic Tools Applied for Assessing Microbial Water Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5128. [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association (APHA). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- CETESB – Companhia Ambiental do Estado de São Paulo. Índice de Qualidade das Águas (IQA): Métodos e Aplicações; CETESB: São Paulo, Brazil, 2023. Available online: https://cetesb.sp.gov.br/aguasinteriores/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2022/11/Apendice-E-Indices-de-Qualidade-das-Aguas.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Conselho Nacional do Meio Ambiente (CONAMA). Resolução No. 357, de 17 de Março de 2005; Ministério do Meio Ambiente: Brasília, Brazil, 2005. Available online: https://conama.mma.gov.br/?id=450&option=com_sisconama&task=arquivo.download (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria GM/MS No. 888, de 4 de Maio de 2021; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2021; pp. 1–29. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-gm/ms-n-888-de-4-de-maio-de-2021-318461562 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria de Consolidação No. 5, de 28 de Setembro de 2017; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2017; pp. 1–856. Available online: https://portalsinan.saude.gov.br/images/documentos/Legislacoes/Portaria_Consolidacao_5_28_SETEMBRO_2017.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 697–703. [CrossRef]

- Mentasti, M.; Prime, K.; Sands, K.; Khan, S.; Wootton, M. Rapid detection of IMP, NDM, VIM, KPC and OXA-48-like carbapenemases from Enterobacteriales and Gram-negative non-fermenter bacteria by real-time PCR and melt-curve analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 2029–2036. [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Vigilância e Controle da Qualidade da Água para Consumo Humano; Série B; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2006. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/vigilancia_controle_qualidade_agua.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Valente, J.P.S.; Padilha, P.M.; Silva, A.M.M. Oxigênio dissolvido (OD), demanda bioquímica de oxigênio (DBO) e demanda química de oxigênio (DQO) como parâmetros de poluição no ribeirão Lavapés/Botucatu-SP. Eclética Química 1997, 22, 49–66. [CrossRef]

- von Sperling, M.; Verbyla, M.E.; Oliveira, S.M.A.C. Assessment of Treatment Plant Performance and Water Quality Data: A Guide for Students, Researchers and Practitioners; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Rice, E.W. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Davies-Colley, R.J.; Bell, R.G.; Donnison, A.M. Sunlight inactivation of enterococci and fecal coliforms in sewage effluent diluted in seawater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 2049–2058. [CrossRef]

- Bahlaoui, M.A.; Baleux, B.; Troussellier, M. Dynamics of pollution-indicator and pathogenic bacteria in high-rate oxidation wastewater treatment ponds. Water Research 1997, 31, 630–638. [CrossRef]

- Amos, G.C.; Hawkey, P.M.; Gaze, W.H.; Wellington, E.M. Waste water effluent contributes to the dissemination of CTX-M-15 in the natural environment. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 1785–1791. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L.; Manaia, C.; Merlin, C.; Schwartz, T.; Dagot, C.; Ploy, M.C.; Michael, I.; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 447, 345–360. [CrossRef]

- Ferro, G.; Guarino, F.; Castiglione, S.; Rizzo, L. Antibiotic resistance spread potential in urban wastewater effluents disinfected by UV/H₂O₂ process. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 560–561, 29–35. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, N.E.; Altayb, H.N.; Gurashi, R.M. Detection of carbapenem-resistant genes in Escherichia coli isolated from drinking water in Khartoum, Sudan. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020, 2571293. [CrossRef]

- Tafoukt, R.; Touati, A.; Leangapichart, T.; Bakour, S.; Rolain, J.M. Characterization of OXA-48-like-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated from river water in Algeria. Water Res. 2017, 120, 185–189. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, B.M.; Brehony, C.; Cahill, N.; McGrath, E.; O’Connor, L.; Varley, A.; Cormican, M.; Ryan, S.; Hickey, P.; Keane, S.; Mulligan, M.; Ruane, B.; Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C.; Brisse, S.; Morris, D. Detection of OXA-48-like-producing Enterobacterales in Irish recreational water. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.P.; Adeli, A.; McLaughlin, M.R. Microbial ecology, bacterial pathogens, and antibiotic resistant genes in swine manure wastewater as influenced by three swine management systems. Water Res. 2014, 57, 96–103. [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Yu, S.; Rysz, M.; Luo, Y.; Yang, F.; Li, F.; Hou, J.; Mu, Q.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Prevalence and proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes in two municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2015, 85, 458–466. [CrossRef]

- Tsvetanova, Z.; Boshnakov, R. Antimicrobial Resistance of Waste Water Microbiome in an Urban Waste Water Treatment Plant. Water 2025, 17, 39. [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, R.; Mezzomo, L.C.; Machado, W.; da Silva Morais Hein, C.; Müller, C.Z.; da Silva, T.C.B.; Jank, L.; Lamas, A.E.; da Costa Ballestrin, R.A.; Wink, P.L.; Lima, A.A.; Corção, G.; Martins, A.F. The occurrence of antimicrobial residues and antimicrobial resistance genes in urban drinking water and sewage in Southern Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 1483–1489. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Fang, H.; Kong, M. Effect of antibiotics, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and extracellular antibiotic resistance genes on the fate of ARGs in marine sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164305. [CrossRef]

- Umar, S.A.; Tasduq, S.A. Ozone Layer Depletion and Emerging Public Health Concerns—An Update on Epidemiological Perspective of the Ambivalent Effects of Ultraviolet Radiation Exposure. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 866733. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Sun, X.; Wu, J.; Ma, L.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, K.; Luo, Y.; Cui, C. Risk assessment of antibiotic resistance genes in the drinking water system. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149650. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).