Introduction

Vertebral fractures are a frequent complication of osteoporosis, characterised by reduced bone density in older adults, often leading to chronic back pain, reduced mobility, and a noticeable drop in quality of life. [

1,

2] Because symptoms can be vague or occur without a clear injury, many of these fractures are often unnoticed initially. [

2] With a gradual global increase of the elderly population, radiologists frequently diagnose these fractures incidentally and as a cause of acute back pain. [

3] Although most osteoporotic fractures are benign, a few may mask underlying malignancies, infections, or other secondary causes. Therefore, a detailed understanding of radiologic patterns and the timely identification of “red flag” signs is crucial in accurate diagnosis, optimal management and minimising further complications. [

4] This article highlights radiologic patterns, clinical red flag signs, and advances in the screening of vertebral fractures.

Epidemiology and Clinical Context

In Sri Lanka’s urban centres, studies show that it affects roughly 27% of women and 7% of men over the age of 50. [

5] The global picture reveals an even more striking consequence of this condition: by age 70, nearly a quarter of women and 12% of men will experience a vertebral compression fracture due to weakened bones. [

6]

What makes osteoporosis so deceptive is that many fractures are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on chest or abdominal imaging. Patients may seek medical advice when they experience sudden-onset back pain, loss of height, or progressive kyphosis. Osteoporotic bone fractures can occur with minimal trauma, such as falling from a standing height. When pain is disproportionate or accompanied by systemic symptoms,

“red flag” causes such as malignancy or infection must be excluded. [

4]

Understanding the Cause

Osteoporosis does not have a single cause. It is helpful to understand its two main categories: Primary Osteoporosis, the most common form related to the natural ageing process, and Secondary Osteoporosis, which is caused by specific diseases or medications. [

7]

Primary Osteoporosis

Postmenopausal osteoporosis (Type I)-In women, the sharp decline in estrogen during menopause accelerates bone loss.

Senile osteoporosis (Type II) - This affects both men and women, typically after the age of 70.

Secondary Osteoporosis

Long-term corticosteroid use

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperthyroidism

Diabetes

Rheumatoid arthritis.

Chronic kidney or liver disease.

Multiple myeloma

Prolonged immobility or lack of weight-bearing exercise.

Imaging Modalities

DEXA (Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry) Scan

The DEXA scan is recognised as the gold standard for evaluating bone health. Its primary goal is to detect low bone mineral density (BMD) before fractures occur, enabling proactive management and treatment. This low-radiation test provides precise measurements of BMD at key weight-bearing sites, most commonly the lumbar spine and proximal femur.DEXA scans report two main scores: the T-score and the Z-score. [

8,

9,

10,

11]

T-Score: Key Indicator for Adults

For postmenopausal women and men over 50, the T-score is the primary diagnostic measure for assessing bone density. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has defined the following thresholds:

Normal Bone Density: T-score ≥ -1.0

Osteopenia (Low Bone Mass): T-score between -1.0 and -2.5

Osteoporosis: T-score <-2.5

Beyond simply categorising bone health, the T-score provides a quantitative link to fracture risk: each drop of one standard deviation in the T-score corresponds to a substantial increase in fracture likelihood. [

8,

9,

10,

11]

Z-Score: Age-Specific Assessment

In younger adults, premenopausal women, and children, the Z-score is more relevant. It shows how a bone density compares with what is typical for someone of the same age and sex. If the Z-score is -2.0 or lower, it is considered unusually low for their age, and further investigation may be needed to identify possible underlying causes of bone loss. [

8,

9,

10,

11]

Plain Radiography

Lateral spine X-ray is the first-line imaging modality for suspected vertebral fractures. X-rays can identify loss of vertebral height and deformity, although early or subtle fractures may be missed.

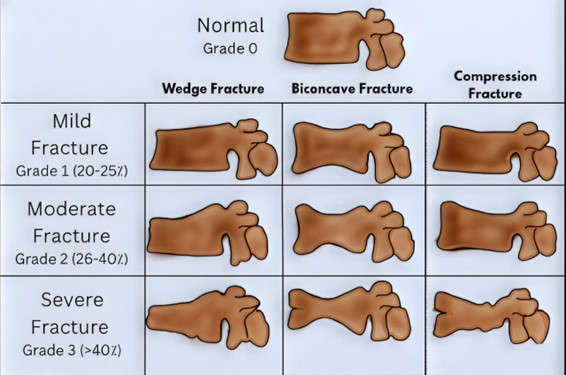

The Genant semiquantitative method is a common method for grading vertebral deformities as mild (20–25% height loss), moderate (25–40%), or severe (>40% height loss). (

Figure 1). Despite its utility, plain radiography has limitations as it cannot reliably distinguish between acute and chronic fractures or between benign and malignant causes. [

10]

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT offers excellent spatial resolution for evaluating fracture morphology, cortical breaches, retropulsed bone fragments, posterior element involvement, and neural canal involvement. In osteoporotic compression fractures, CT typically reveals anterior wedge-shaped vertebral bodies with intact posterior elements and absence of soft-tissue mass. Conversely, malignant fractures may show lytic lesions, cortical destruction, irregular endplates, and associated paraspinal or epidural soft-tissue masses

(Figure 2). CT is also invaluable in surgical planning and evaluating complex burst or unstable fractures. [

9,

11]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI remains the gold standard for differentiating benign osteoporotic fractures from pathologic fractures due to malignancy or infection.

T1W images show marrow with low signal (hypointense) in acute fractures, while STIR or fat-saturated T2 sequences demonstrate marrow oedema (hyperintense), confirming the acuity.

(Figure 3) Chronic fractures often lack marrow oedema and may exhibit fatty replacement.

Benign osteoporotic fractures typically exhibit band-like low signal intensity on T1 and T2 images along the endplate, with spared posterior elements and normal adjacent discs. Malignant fractures, in contrast, exhibit diffuse marrow replacement, convex posterior vertebral borders, epidural or paraspinal soft-tissue components, and involvement of the posterior elements or multiple contiguous vertebrae.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and contrast-enhanced MRI further aid in characterisation: restricted diffusion and early enhancement suggest malignancy. At the same time, benign fractures show variable enhancement patterns. [

11,

12]

Nuclear Medicine and PET Imaging

Bone scintigraphy(99mTc-MDP) can help detect multiple fractures and assess chronicity when MRI is contraindicated. However, increased uptake may persist for months after an acute event. 18F-FDG PET/CT can differentiate between metastatic and benign fractures, as malignant lesions typically show higher standardised uptake values. [

11,

12]

Morphological Classification of Vertebral Compression Fractures

1. Wedge compression fracture

The most common pattern involves anterior height loss with preservation of the posterior wall.

Usually seen in the thoracolumbar junction (T12–L2).

Suggests osteoporosis when occurring with minimal trauma.

2. Biconcave (Codfish) fracture

3. Crush fracture

Uniform collapse of the vertebral body height.

It can cause severe kyphotic deformity.

It may mimic pathological fractures if extensive.

4. Burst fracture

Results from axial loading with involvement of both anterior and posterior walls.

Retropulsed fragments may impinge on the spinal canal, which is a red flag requiring urgent assessment.

Often seen in trauma or advanced osteoporosis.

Red Flag Signs Suggesting Pathologic or Complicated Fracture

Radiologists must recognise imaging features that raise suspicion for secondary causes or instability. Evidence-supported red flags include:

| Red Flag Feature |

Possible Cause |

| Involvement of posterior elements |

Malignancy or infection |

| Paraspinal or epidural soft-tissue mass |

Metastasis, myeloma, abscess |

| Convex posterior border of the vertebral body |

Malignant infiltration |

| Irregular endplate destruction |

Infection or neoplasm |

| Multiple contiguous vertebral involvement |

Metastatic disease, myeloma |

| Preservation of the intervertebral disc with adjacent bone destruction |

Neoplasm |

| Disc space narrowing with endplate erosions |

Spondylodiscitis |

| Retropulsed bony fragments or canal compromise |

Unstable fracture |

| Persistent or worsening pain beyond 6 weeks |

Possible secondary pathology |

Although the diagnostic accuracy of red flags is variable, a combination of these signs substantially increases their predictive value for identifying pathologic or complicated fractures. This warrants a more intensive diagnostic workup, including advanced imaging, to guide subsequent management. [

13]

Management Implications

Osteoporosis management in osteoporotic patients is important in minimising future fractures. This includes Calcium and Vitamin D supplementation, Bisphosphonates, Denosumab and Teriparatide. Management of vertebral fractures in older people primarily involves conservative treatment focused on pain relief, functional restoration, and prevention of future fractures. Correct identification of the fracture pattern and underlying aetiology guides therapy.

Benign osteoporotic fractures are managed conservatively with short-term bed rest, with analgesia for pain relief, and gradual mobilisation with physiotherapy could be focused initially.

Vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty may be considered for persistent pain with stable fractures.

Pathologic fractures due to malignancy or infection warrant biopsy and targeted therapy.

Unstable fractures with neurological compromise require surgical stabilisation.

MRI follow-up after 6–12 weeks can document fracture healing and resolution of marrow oedema, helping to avoid unnecessary repeat interventions. [

14]

Prevention and Prognosis

Preventing further fractures is one of the most important goals in managing osteoporosis. Once a person experiences a vertebral fracture, their risk of having another increases by nearly five times. This highlights the importance of early detection and prompt treatment. Management includes calcium and vitamin D supplements, together with medications such as bisphosphonates, denosumab, or teriparatide. Regular weight-bearing exercises and a practical approach to minimise the risk of falls are also essential parts of care. While many simple fractures heal well with conservative treatment, missing a malignant or unstable fracture can lead to lasting nerve damage or persistent pain. [

14]

Conclusions

In elderly patients, vertebral fractures should never be ignored as casual findings on imaging. They often indicate weakened bones or, in some cases, a more serious underlying condition. Radiologists play a crucial role in identifying these fractures early and distinguishing between different causes. Recognising typical imaging features and being alerted to warning signs helps ensure timely treatment, reduces complications, and supports better mobility, independence, and quality of life in later stages of life.

Author Contributions

SRS formulated the concept, designed the review, conducted the literature review and wrote the manuscript. WNH conducted the literature review and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This review received no external funding.

Availability of data and materials

Acquired DICOM medical images during the current review are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The subject’s identifying information was removed from the radiology images.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not considered, as our work is a narrative review. However, we have secured informed consent to publish radiological images from each patient (Image numbers:

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Figure 1 was created by WNH. Additionally, we have intentionally removed identifying information from the radiology images. Consent was obtained in the local and English languages, and fully completed consent forms are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Genant HK, Li J, Wu CY, Shepherd JA. Vertebral fractures in osteoporosis: a new method for clinical assessment. Journal of Clinical Densitometry. 2000 Sep 1;3(3):281-90.

- Old JL, Calvert M. Vertebral compression fractures in the elderly. American family physician. 2004 Jan 1;69(1):111-6.

- Lentle B, Koromani F, Brown JP, Oei L, Ward L, Goltzman D, Rivadeneira F, Leslie WD, Probyn L, Prior J, Hammond I. The radiology of osteoporotic vertebral fractures revisited. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2019 Mar 1;34(3):409-18.

- Han CS, Hancock MJ, Downie A, Jarvik JG, Koes BW, Machado GC, Verhagen AP, Williams CM, Chen Q, Maher CG. Red flags to screen for vertebral fracture in people presenting with low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023(8).

- Karunanayake AL, Pinidiyapathirage MJ, Wickremasinghe AR. Prevalence and predictors of osteoporosis in an urban Sri Lankan population. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2010 Oct;13(4):385-90.

- McDonald CL, Alsoof D, Daniels AH. Vertebral compression fractures. Rhode Island Medical Journal. 2022 Oct 1;105(8):40-5.

- Ebeling PR, Nguyen HH, Aleksova J, Vincent AJ, Wong P, Milat F. Secondary osteoporosis. Endocrine reviews. 2022 Apr 1;43(2):240-313.

- Sangondimath G, Sen RK, T FR. DEXA and Imaging in Osteoporosis. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2023 Dec;57(Suppl 1):82-93.

- Clemente MA, Rabasco P, Iannelli G, Villonio A, Lotumolo A, Gioioso M, Zandolino A, Guglielmi G, Cammarota A. Vertebral Compression Fractures in Elderly: How to Recognize and Report. Current Radiology Reports. 2018 Jul 4;6(9):32.

- Löffler MT, Sollmann N, Mei K, Valentinitsch A, Noël PB, Kirschke JS, Baum T. X-ray-based quantitative osteoporosis imaging at the spine. Osteoporosis International. 2020 Feb;31(2):233-50.

- Adams JE. Advances in bone imaging for osteoporosis. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2013 Jan;9(1):28-42.

- Panda A, Das CJ, Baruah U. Imaging of vertebral fractures. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2014 May 1;18(3):295-303.

- Downie A, Williams CM, Henschke N, Hancock MJ, Ostelo RW, De Vet HC, Macaskill P, Irwig L, Van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Maher CG. Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain: systematic review. Bmj. 2013 Dec 11;347.

- Beeharry MW, Moqeem K, Rohilla MU. Management of cervical spine fractures: a literature review. Cureus. 2021 Apr 11;13(4).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).