Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

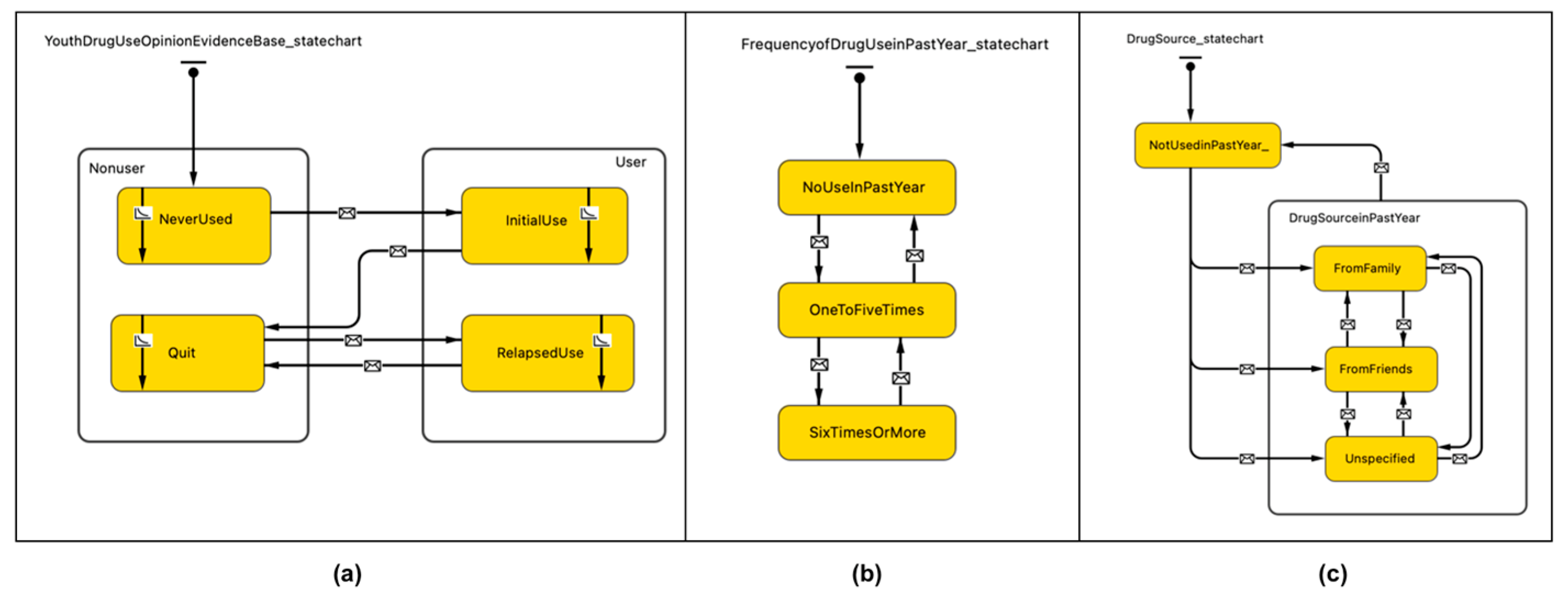

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

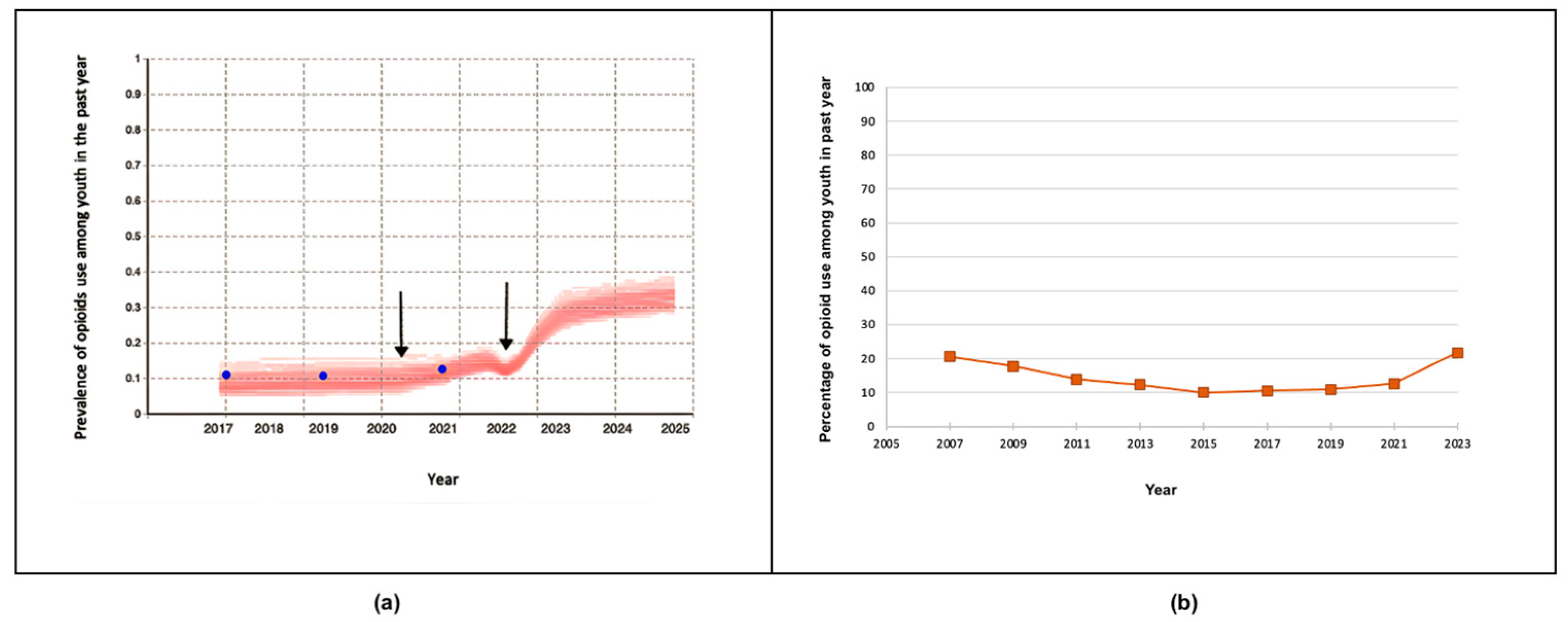

3.1. Validation of Prior Published Results Against Newly Released 2023 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS)

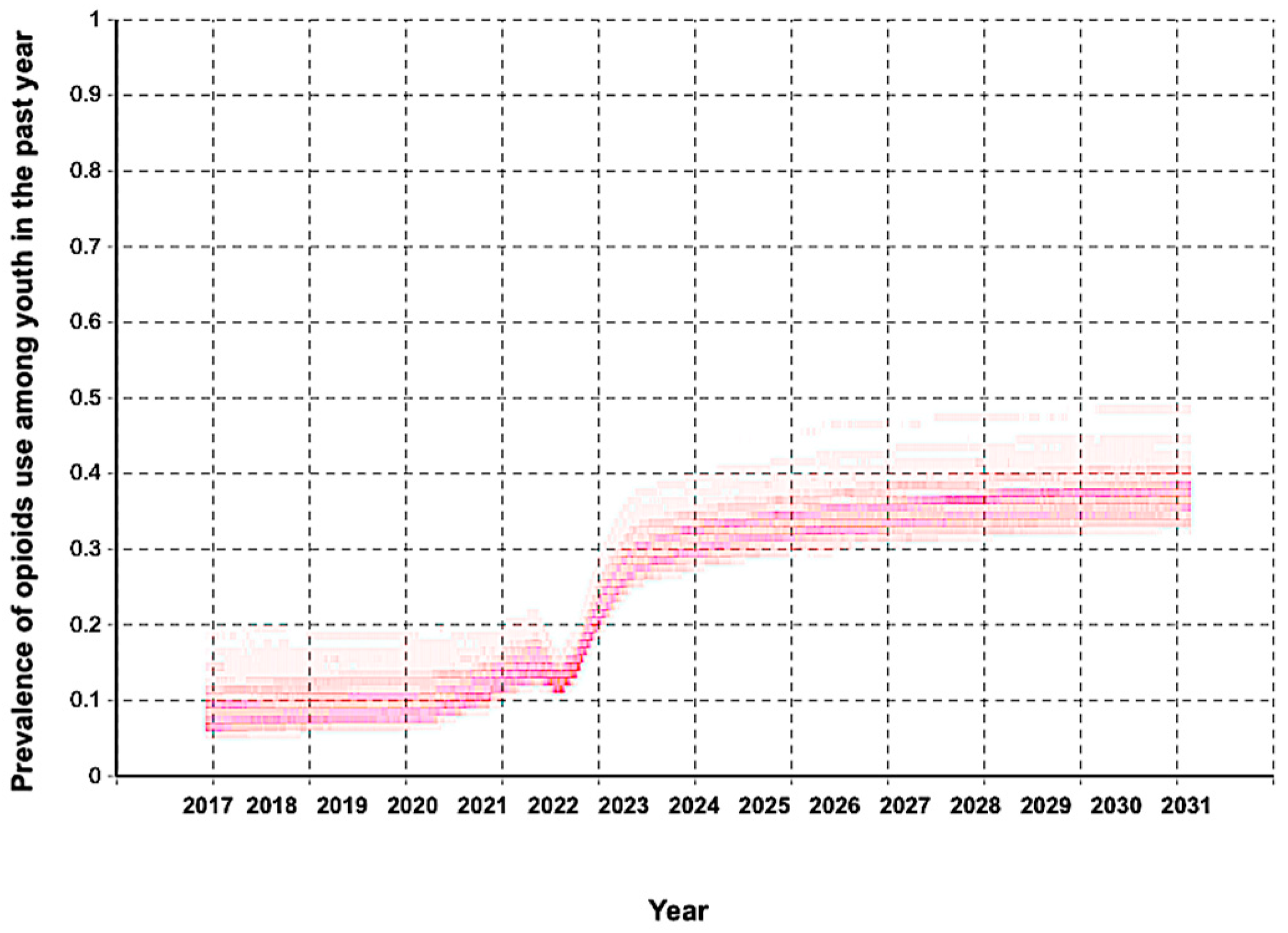

3.2. Extended Model-Generated Projections Of Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use Prevalence Among Ontario Adolescents Through 2030

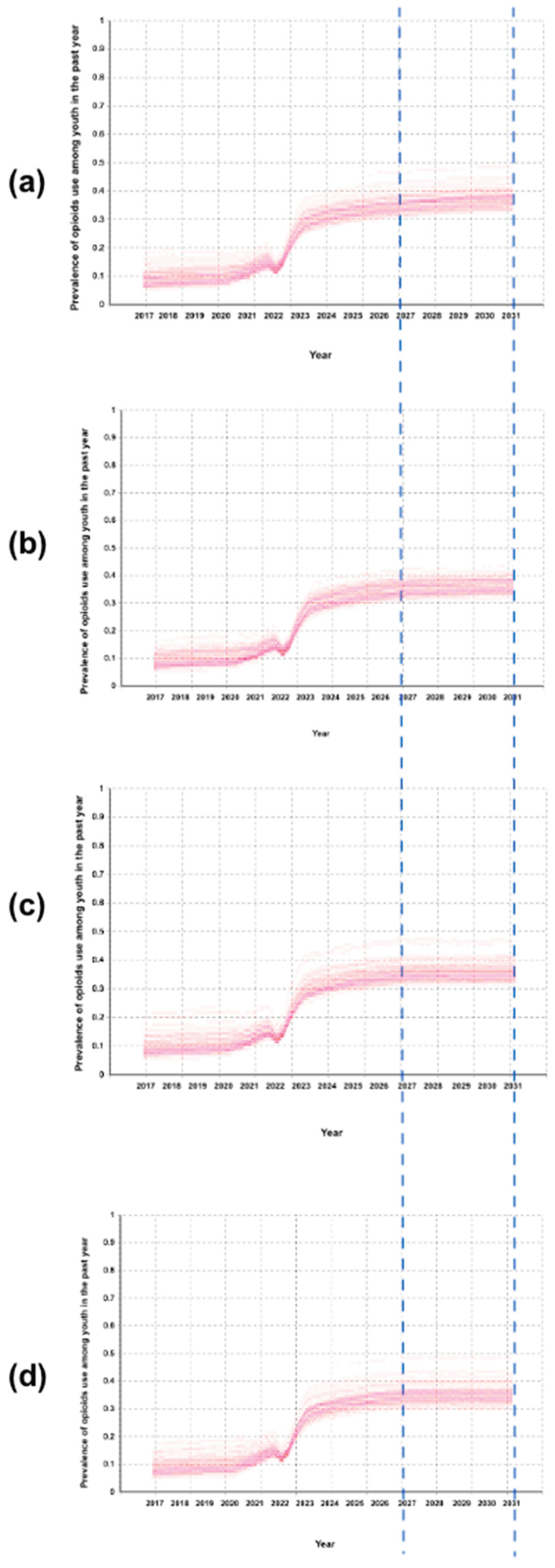

3.2. Investigating Impact of Reductions in Youth Household Opioid Exposure Through Safe mediecin Storage Scenarios

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | COronaVIrus Disease 2019 |

| OSDUHS | Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey |

| SDM | System Dynamics Model |

| ABM | Agent-Based Model |

| SIR model | Susceptible–Infected–Recovered model |

References

- Vaillancourt, T.; McDougall, P.; Comeau, J.; Finn, C. COVID-19 School Closures and Social Isolation in Children and Youth: Prioritizing Relationships in Education. Facets 2021, 6, 1795–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurini, J.; Davies, S. COVID-19 School Closures and Educational Achievement Gaps in Canada: Lessons from Ontario Summer Learning Research. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie 2021, 58, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadermann, A.; Thomson, K.; Gill, R.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Gagné Petteni, M.; Guhn, M.; Warren, M.T.; Oberle, E. Early Adolescents’ Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Changes in Their Well-Being. Frontiers in public health 2022, 10, 823303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBonte, R.; Barbour, M.K.; Mongrain, J. Teaching during Times of Turmoil: Ensuring Continuity of Learning during School Closures. In A Special Report of the Canadian eLearning Network; 2022; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Mackay, K.; Srivastava, P.; Underwood, K.; Dhuey, E.; McCready, L.; Born, K.; Maltsev, A.; Perkhun, A.; Steiner, R.; Barrett, K. COVID-19 and Education Disruption in Ontario: Emerging Evidence on Impacts. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartney, M.T.; Finger, L.K. Politics, Markets, and Pandemics: Public Education’s Response to COVID-19. Perspectives on Politics 2022, 20, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Principi, N. School Closure during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: An Effective Intervention at the Global Level? JAMA pediatrics 2020, 174, 921–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervais, C.; Côté, I.; Lampron-deSouza, S.; Barrette, F.; Tourigny, S.; Pierce, T.; Lafantaisie, V. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Quality of Life: Experiences Contributing to and Harming the Well-Being of Canadian Children and Adolescents. International journal on child maltreatment: research, policy and practice 2023, 6, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, R.; Russell, S.; Saulle, R.; Croker, H.; Stansfield, C.; Packer, J.; Nicholls, D.; Goddings, A.-L.; Bonell, C.; Hudson, L. School Closures during Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-Being among Children and Adolescents during the First COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review. JAMA pediatrics 2022, 176, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Otto, C.; Adedeji, A.; Devine, J.; Erhart, M.; Napp, A.-K.; Becker, M.; Blanck-Stellmacher, U.; Löffler, C. Mental Health and Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Results of the COPSY Study. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 2020, 117, 828. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, S.; Kyron, M.; Hunter, S.C.; Lawrence, D.; Hattie, J.; Carroll, A.; Zadow, C. Adolescents’ Longitudinal Trajectories of Mental Health and Loneliness: The Impact of COVID-19 School Closures. Journal of adolescence 2022, 94, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.; Di Maio, J.; Weeraratne, T.; Kennedy, K.; Oliver, L.; Bouchard, M.; Malhotra, D.; Habashy, J.; Ding, J.; Bhopa, S. Resilience in Adolescence during the COVID-19 Crisis in Canada. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundahl, L.H.; Cannoy, C. COVID-19 and Substance Use in Adolescents. Pediatric Clinics of North America 2021, 68, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, T.M.; Ellis, W.E.; Van Hedger, S.; Litt, D.M.; MacDonald, M. Lockdown, Bottoms up? Changes in Adolescent Substance Use across the COVID-19 Pandemic. Addictive behaviors 2022, 131, 107326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigatu, Y.T.; Wells, S.; Buckley, L.; Quilty, L.C.; Bozinoff, N.; Ali, F.; Imtiaz, S.; Hamilton, H.A. Non-Medical Use of Prescription Opioids: Use to Experience Subjective Effects vs. Other Non-Medical Use among Adults in Ontario, Canada from 2020 to 2024. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2025, jsad–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.; Kaoser, R.; Rudoler, D.; Fischer, B. Trends in Dispensing of Individual Prescription Opioid Formulations, Canada 2005–2020. Journal of pharmaceutical policy and practice 2022, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, G.; Woo, B.; Lo-Ciganic, W.-H.; Gordon, A.J.; Donohue, J.M.; Gellad, W.F. Defining Nonmedical Use of Prescription Opioids within Health Care Claims: A Systematic Review. Substance abuse 2015, 36, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, E.A. Understanding the Risk Factors and Lived Experiences of Prescription Drug Abuse among Canadian Children and Adolescents: A Retrospective Phenomenological Study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse 2019, 28, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.A.; Wilson, J.D. Management of Opioid Misuse and Opioid Use Disorders among Youth. Pediatrics 2020, 145, S153–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calihan, J.; Matson, P.; Alinsky, R. The Adolescent and the Medicine Cabinet; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Seamans, M.J.; Carey, T.S.; Westreich, D.J.; Cole, S.R.; Wheeler, S.B.; Alexander, G.C.; Pate, V.; Brookhart, M.A. Association of Household Opioid Availability and Prescription Opioid Initiation among Household Members. JAMA internal medicine 2018, 178, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.N.; Coen, S.E.; Tobin, D.; Martin, G.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. The Mental Well-Being and Coping Strategies of Canadian Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative, Cross-Sectional Study. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal 2021, 9, E1013–E1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussong, A.; Midgette, A.; Thomas, T.; Coffman, J.; Cho, S. Coping and Mental Health in Early Adolescence during COVID-19. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology 2021, 49(9), 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of youth and adolescence 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, L.; Tadros, E.; Patton, R. The Role of Family in Youth Opioid Misuse: A Literature Review. The Family Journal 2019, 27, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Blanco, C. Research on Substance Use Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2021, 129, 108385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, D.J.; Kirk, H.M.; Leonard, K.E.; Lynch, J.J.; Nielsen, N.; Clemency, B.M. Assessing Challenges and Solutions in Substance Abuse Prevention, Harm Reduction, and Treatment Services in New York State. SSM-Health Systems 2024, 3, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panos, G.D.; Boeckler, F.M. Statistical Analysis in Clinical and Experimental Medical Research: Simplified Guidance for Authors and Reviewers. Drug design, development and therapy 2023, 1959–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajula, H.S.R.; Verlato, G.; Manchia, M.; Antonucci, N.; Fanos, V. Comparison of Conventional Statistical Methods with Machine Learning in Medicine: Diagnosis, Drug Development, and Treatment. Medicina 2020, 56, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Complex Adaptive Systems. Daedalus 1992, 121, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pritsker, A.A.B. Why Simulation Works. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21st conference on Winter simulation, 1989; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, A. Systems Modelling, Simulation, and the Dynamics of Strategy. Journal of Business Research 2003, 56, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.P.; Pugh, A.L., III. Introduction to System Dynamics Modeling with DYNAMO. Journal of the Operational Research Society 1997, 48, 1146–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Railsback, S.F.; Grimm, V. Agent-Based and Individual-Based Modeling: A Practical Introduction; Princeton university press, 2019; ISBN 0-691-19004-6. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, J.A.P. Mathematical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases: Model Building, Analysis and Interpretation; John Wiley & Sons, 2000; Vol. 5, ISBN 0-471-49241-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom, C.T.; Hanage, W.P. Human Behavior and Disease Dynamics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2317211120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.A. Lessons Learned on Development and Application of Agent-Based Models of Complex Dynamical Systems. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2018, 83, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B.D. Agent-Based Modeling. Systems science and population health 2017, 15, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. A Narrative Review of the Use of Agent-Based Modeling in Health Behavior and Behavior Intervention. Translational behavioral medicine 2019, 9, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZHANG, T. Exploring the Mechanism-Based Explanation of Complex Social Phenomena: A Social Simulation Study of the Diffusion of College Students Drinking Behavior in Friendship Networks. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Hipp, J.R.; Butts, C.T.; Jose, R.; Lakon, C.M. Peer Influence, Peer Selection and Adolescent Alcohol Use: A Simulation Study Using a Dynamic Network Model of Friendship Ties and Alcohol Use. Prevention science 2017, 18, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmacher, N.; Ballato, L.; van Geert, P. Using an Agent-Based Model to Simulate the Development of Risk Behaviors during Adolescence. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 2014, 17, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J.R.; Andrejko, K.L.; Cheng, Q.; Collender, P.A.; Phillips, S.; Boser, A.; Heaney, A.K.; Hoover, C.M.; Wu, S.L.; Northrup, G.R. School Closures Reduced Social Mixing of Children during COVID-19 with Implications for Transmission Risk and School Reopening Policies. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2021, 18, 20200970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A.A.; El Antably, A. Agent-Based Modeling and Simulation of Pandemic Propagation in a School Environment. International Journal of Architectural Computing 2023, 21, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Hernandez, A.M.; Huerta-Quintanilla, R. Managing School Interaction Networks during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Agent-Based Modeling for Evaluating Possible Scenarios When Students Go Back to Classrooms. Plos one 2021, 16, e0256363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, A.T.; Patton, T.; Peacock, A.; Larney, S.; Borquez, A. Illicit Substance Use and the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States: A Scoping Review and Characterization of Research Evidence in Unprecedented Times. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19, 8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegal, N.; Simon, K.; Freedman, S.; Aalsma, M.C.; Wing, C. Stalled Improvements? Youth Opioid Misuse 2015–2022. Journal of Adolescent Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Jain, S. Contemporary Approaches to Analyze Non-Stationary Time-Series: Some Solutions and Challenges. Recent Advances in Computer Science and Communications (Formerly: Recent Patents on Computer Science) 2023, 16, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Sa-Ngasoongsong, A.; Beyca, O.; Le, T.; Yang, H.; Kong, Z.; Bukkapatnam, S.T. Time Series Forecasting for Nonlinear and Non-Stationary Processes: A Review and Comparative Study. Iie Transactions 2015, 47, 1053–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaati, N.; Osgood, N.D. An Agent-Based Social Impact Theory Model to Study the Impact of in-Person School Closures on Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use among Youth. Systems 2023, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B. The Psychology of Social Impact. American psychologist 1981, 36, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boak, A.; Elton-Marshall, T.; Mann, R.E.; Hamilton, H.A. Drug Use among Ontario Students. In Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boak, A.; Elton-Marshall, T.; Hamilton, H.A. The Well-Being of Ontario Students: Findings from the 2021 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey. 2021. Available online: https://www.

- Boak, A.; Hamilton, H.A. Drug Use Among Ontario Students. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hołyst, J.A.; Kacperski, K.; Schweitzer, F. Social Impact Models of Opinion Dynamics. Annual Reviews Of Computational PhysicsIX 2001, 253–273. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, C.; Fortunato, S.; Loreto, V. Statistical Physics of Social Dynamics. Reviews of modern physics 2009, 81, 591–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borshchev, A. The Big Book of Simulation Modeling: Multimethod Modeling with AnyLogic 6; AnyLogic North America, 2013; ISBN 0-9895731-7-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, A.; Taghiyareh, F. Effect of Segregation on the Dynamics of Noise-Free Social Impact Model of Opinion Formation through Agent-Based Modeling. International Journal of Web Research 2019, 2, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, A.; Szamrej, J.; Latané, B. From Private Attitude to Public Opinion: A Dynamic Theory of Social Impact. Psychological review 1990, 97, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.; Klein, M. Dependence, Withdrawal and Rebound of CNS Drugs: An Update and Regulatory Considerations for New Drugs Development. Brain communications 2019, 1, fcz025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilachinski, A. Cellular Automata: A Discrete Universe; World Scientific Publishing Company, 2001; ISBN 981-310-256-X. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, K., Jr.; Duff, M.J. Modern Cellular Automata: Theory and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013; ISBN 1-4899-0393-3. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, E.F. Machine Models of Self-Reproduction; American Mathematical Society New York, 1962; Vol. 14, pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mollick, J.A.; Kober, H. Computational Models of Drug Use and Addiction: A Review. Journal of abnormal psychology 2020, 129, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumann, R.B.; Guynn, I.; Clare, H.M.; Lich, K.H. Insights from System Dynamics Applications in Addiction Research: A Scoping Review. Drug and alcohol dependence 2022, 231, 109237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Miguel, M.; Johnson, J.H.; Kertesz, J.; Kaski, K.; Díaz-Guilera, A.; MacKay, R.S.; Loreto, V.; Erdi, P.; Helbing, D. Challenges in Complex Systems Science. The European Physical Journal Special Topics 2012, 214, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadami, A.; Epureanu, B.I. Data-Driven Prediction in Dynamical Systems: Recent Developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2022, 380, 20210213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).