Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

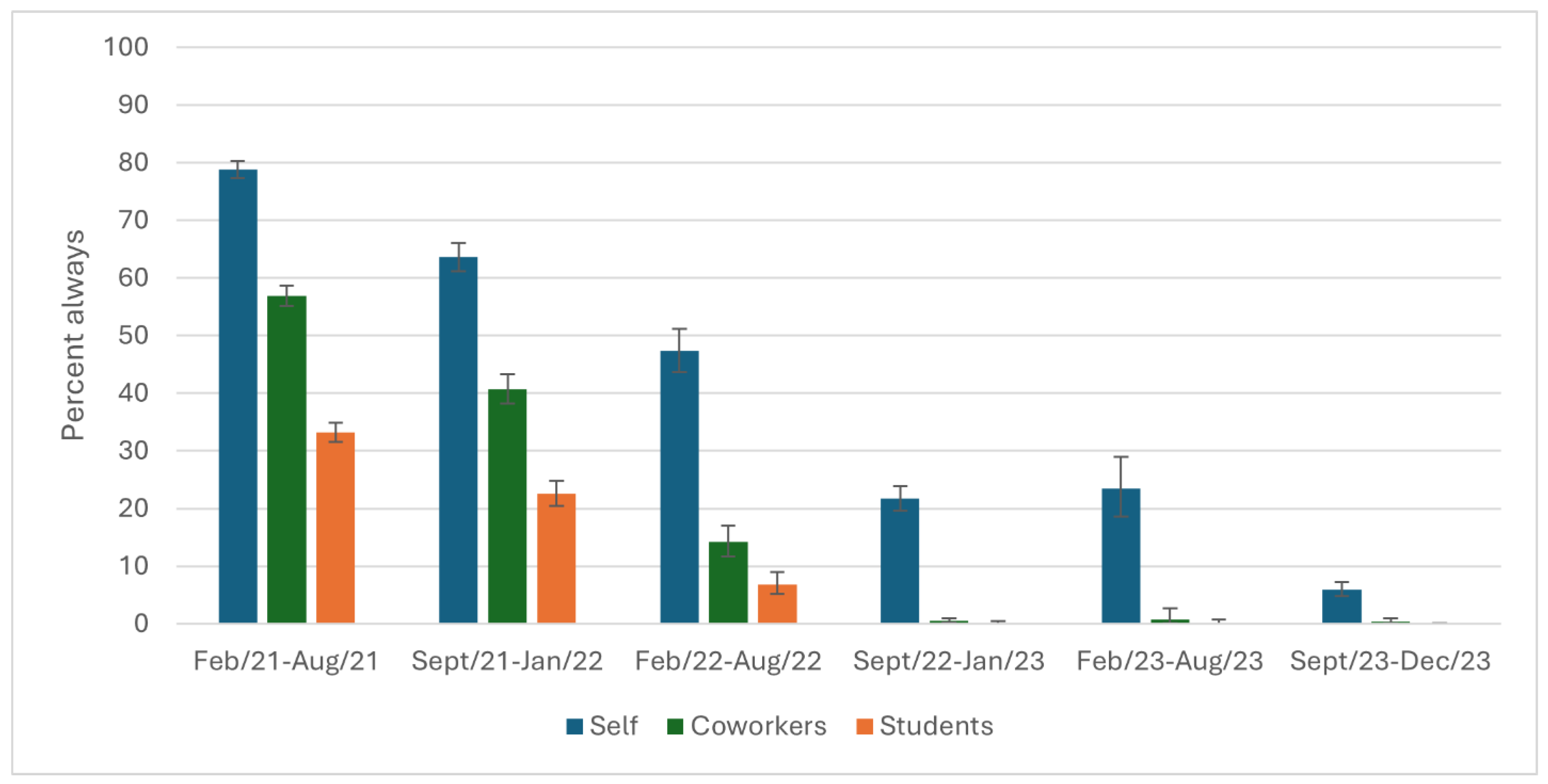

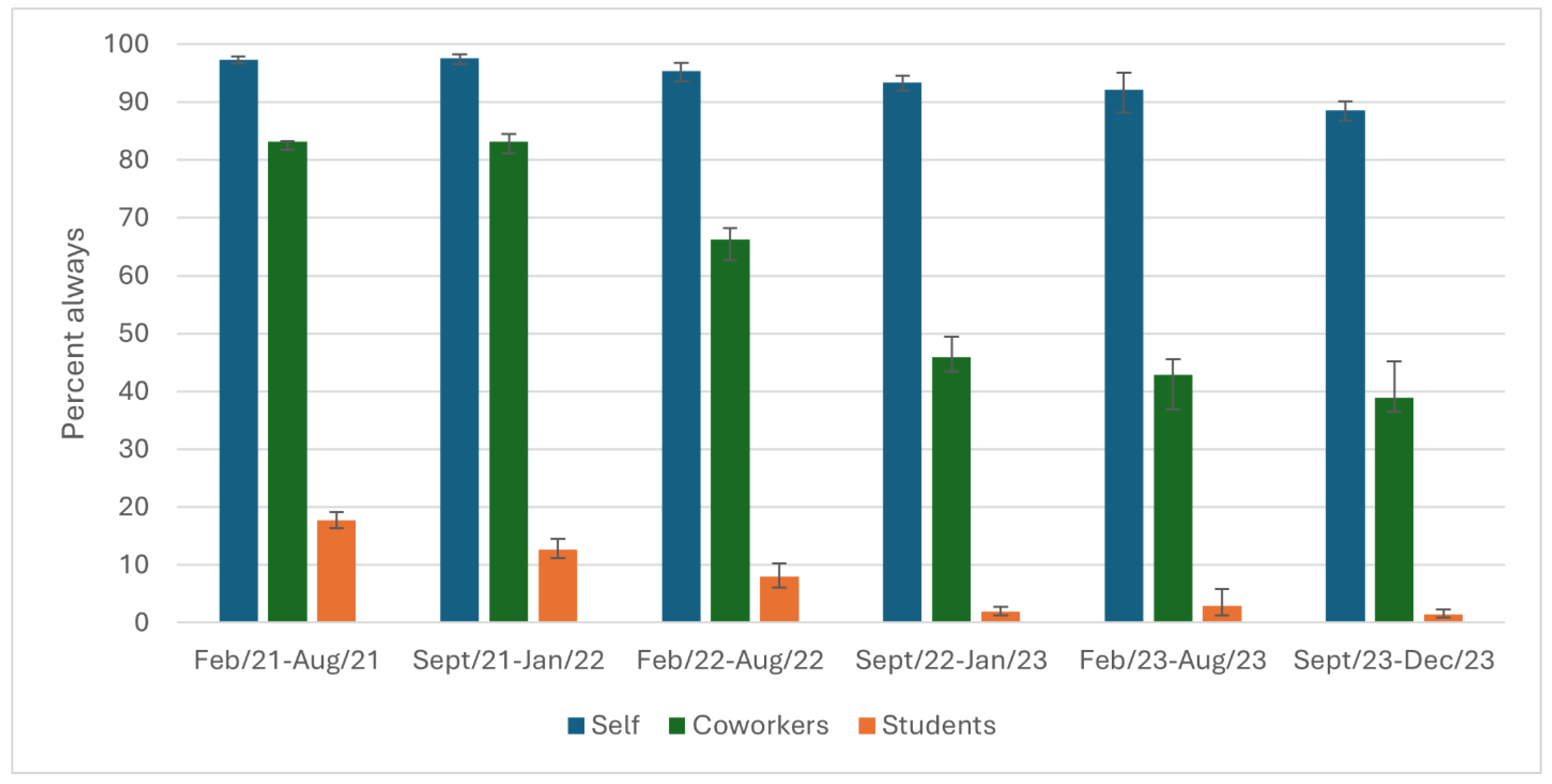

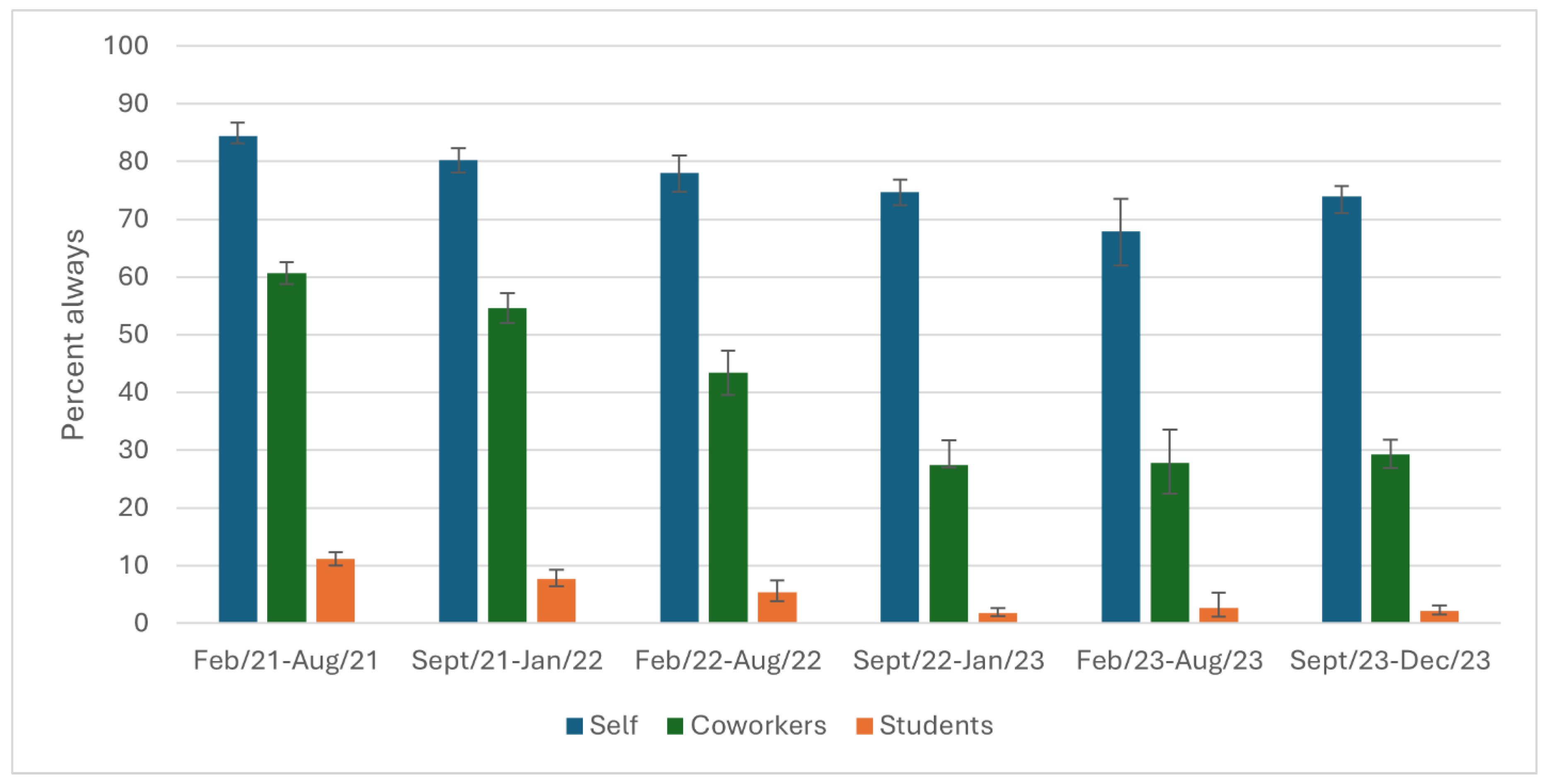

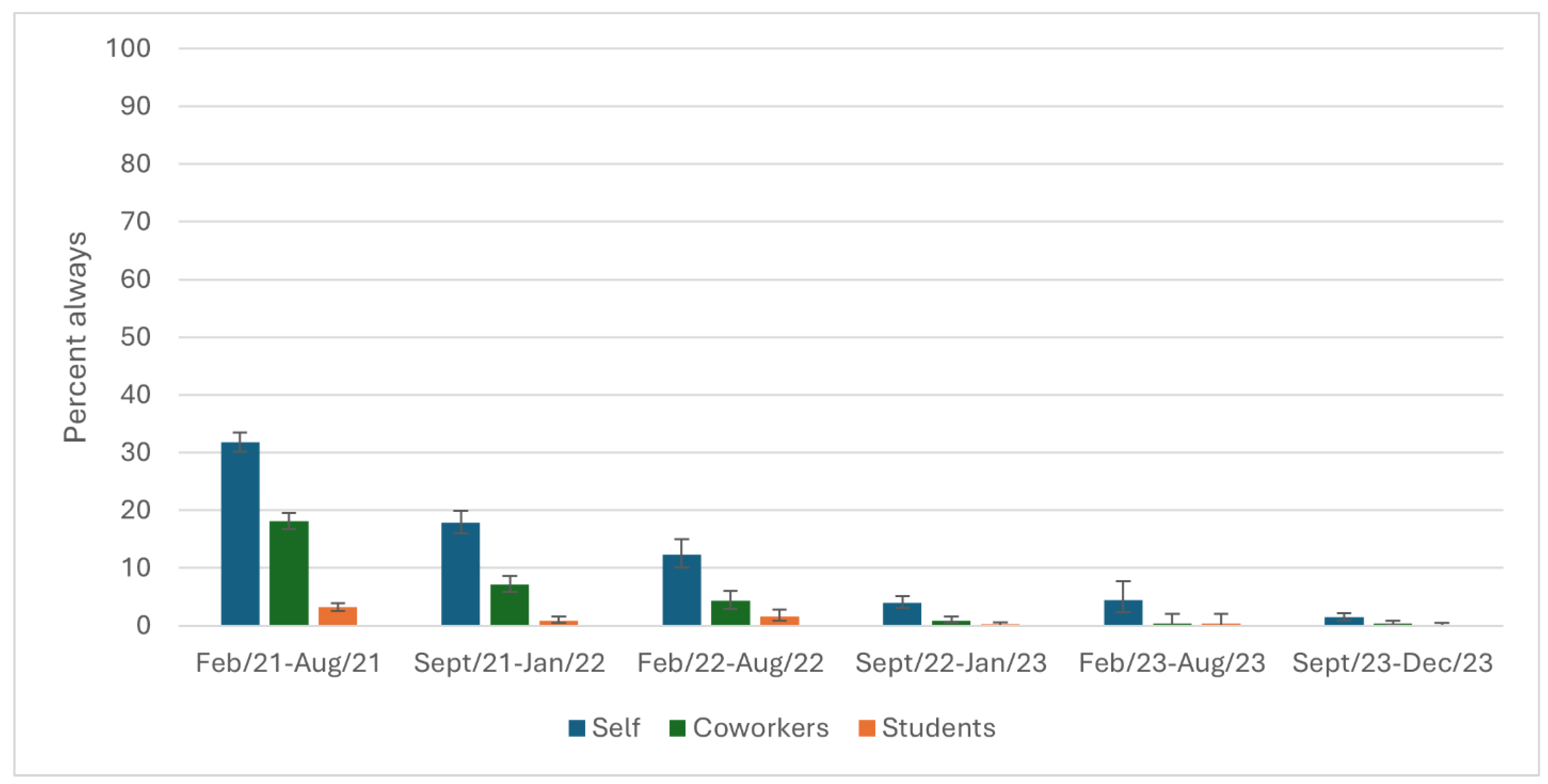

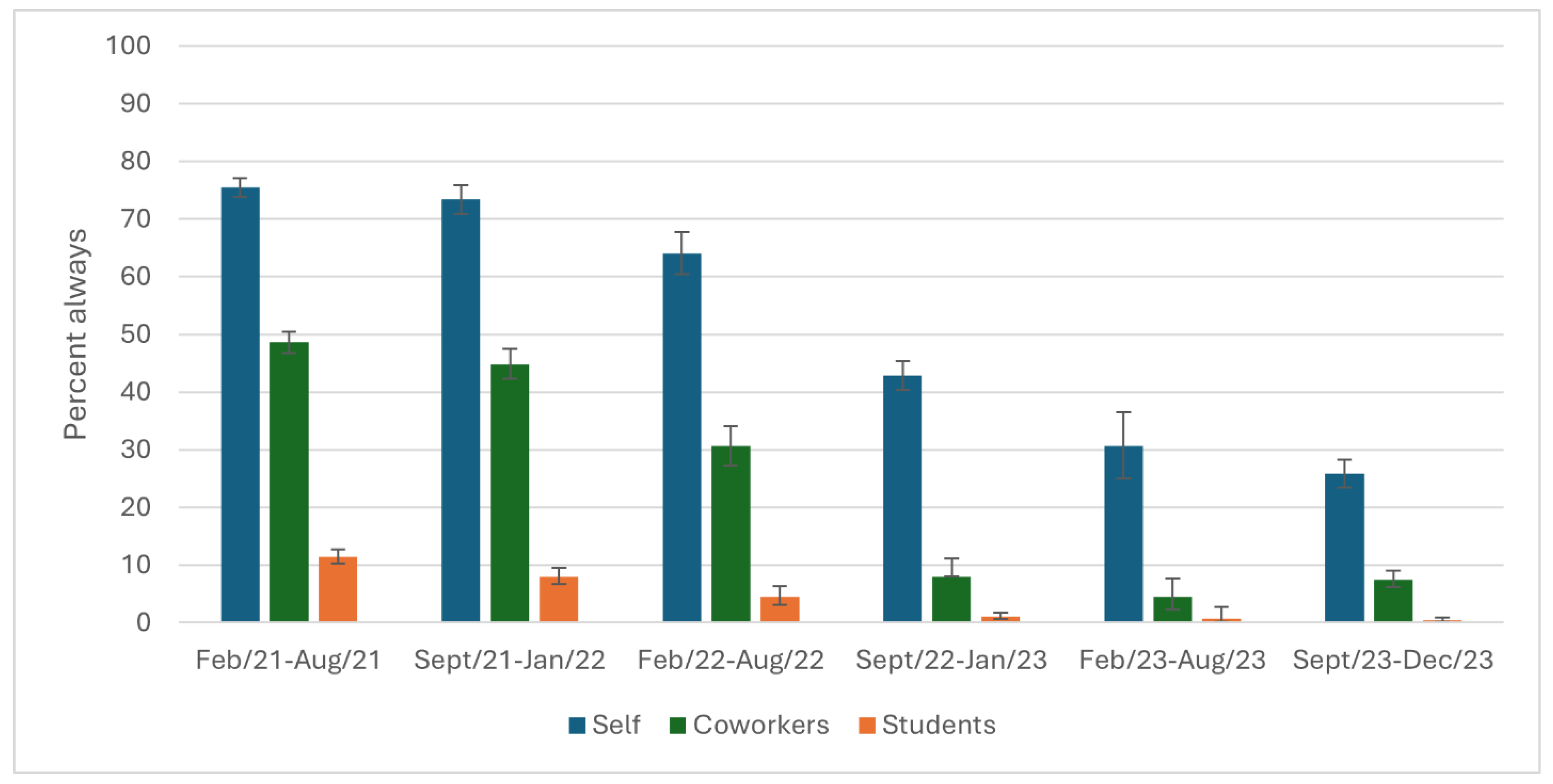

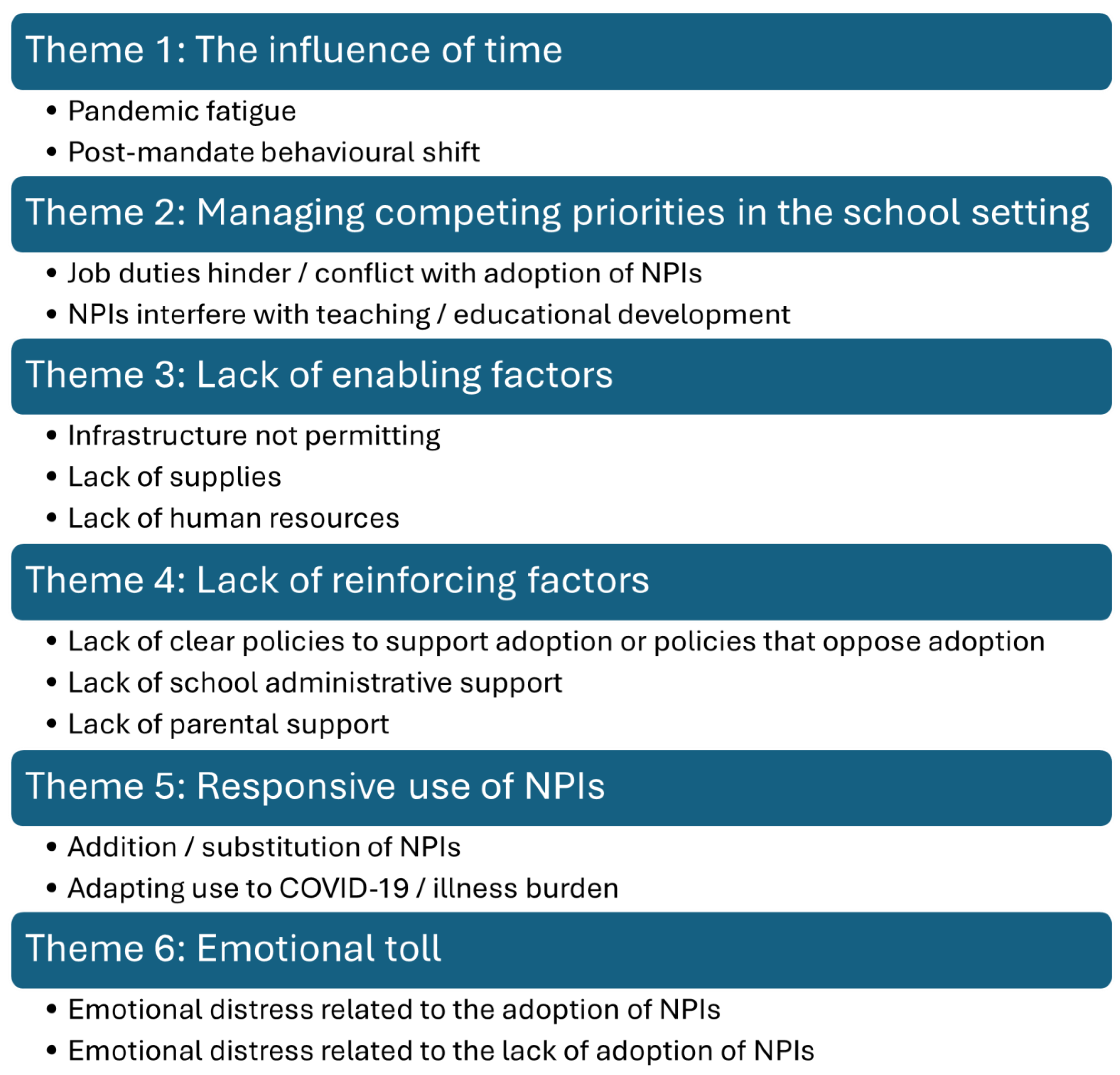

The use of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) was imperative to avoid prolonged school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this study was to understand the levels of adherence to and attitudes towards NPIs from February 2021 to December 2023 in schools in Ontario, Canada. Participants reported how frequently they, their coworkers, and their students used five NPIs: hand hygiene, covering coughs, staying home when ill, wearing a mask, and physically distancing. Open text comments provided participants with the option to provide additional details. A mixed methods approach incorporated a series of descriptive statistics calculated at consecutive time points and thematic analysis. Participants reported higher adherence to NPIs than their coworkers and students, with less than perfect adherence that declined over time. Six themes emerged from the analysis on NPI use in schools: 1) the influence of time; 2) managing competing priorities; 3) lack of enabling factors; 4) lack of reinforcing factors; 5) responsive use of NPIs; and 6) emotional toll. Poor use of hand hygiene, covering coughs, and staying home when ill indicate a need to improve these in schools as it would help reduce the transmission of communicable diseases and thereby reduce sick days for staff and students.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection and Preparation

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results: Reported Use Over Time

3.2. Qualitative Results: Themes

3.2.1. Theme 1: The Influence of Time

3.2.2. Theme 2: Managing Competing Priorities in the School Setting

3.3.3. Theme 3: Lack of Enabling Factors

3.3.4. Theme 4: Lack of Reinforcing Factors

3.3.5. Theme 5: Responsive Use of NPIs

3.3.6. Theme 6: Emotional Toll

4. Discussion

6. Study Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): Situation report - 1: 21 January 2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/situation-report---1.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing spread of infections in K-12 schools [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/orr/school-preparedness/infection-prevention/index.html.

- Hoofman J, Secord E. The Effect of COVID-19 on Education. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2021;68(5):1071-9. [CrossRef]

- Mazrekaj D, De Witte K. The Impact of School Closures on Learning and Mental Health of Children: Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2024;19(4):686-93. [CrossRef]

- Science M, Thampi N, Bitnun A, Born KB, Blackman N, Cohen E, et al. Infection prevention and control considerations for schools during the 2022-2023 academic year. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. 2022;3(64). [CrossRef]

- Whitley J, Beauchamp MH, Brown C. The impact of COVID-19 on the learning and achievement of vulnerable Canadian children and youth. FACETS. 2021;6:1693-713. [CrossRef]

- Government of Ontario Newsroom. Ontario Confirms First Case of Wuhan Novel Coronavirus [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/55486/ontario-confirms-first-case-of-wuhan-novel-coronavirus.

- Office of the Premier, Government of Ontario Newsroom. Ontario Enacts Declaration of Emergency to Protect the Public [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56356/ontario-enacts-declaration-of-emergency-to-protect-the-public.

- Office of the Premier, Government of Ontario Newsroom. School Closures Extended to Keep Students, Staff and Families Safe 2020 [Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56776/school-closures-extended-to-keep-students-staff-and-families-safe.

- Office of the Premier, Government of Ontario Newsroom. Ontario Extends School and Child Care Closures to Fight Spread of COVID-19 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56529/ontario-extends-school-and-child-care-closures-to-fight-spread-of-covid-19.

- Office of the Premier, Government of Ontario Newsroom. Health and Safety Top Priority as Schools Remain Closed [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56971/health-and-safety-top-priority-as-schools-remain-closed.

- Gallagher-Mackay K, Srivastava P, Underwood K, Dhuey E, McCready L, Born KB, et al. COVID-19 and Education Disruption in Ontario: Emerging Evidence on Impacts. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. 2021;2(34). [CrossRef]

- Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. Ontario Returns to School: An Overview of the Science [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 11]. Available from: https://covid19-sciencetable.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Ontario-Returns-to-School-An-Overview-of-the-Science_20220112-1.pdf.

- Science M, Thampi N, Bitnun A, Allen U, Birken C, Blackman N, et al. School Operation for the 2021-2022 Academic Year in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. 2021;2(38). [CrossRef]

- Viner R, Russell S, Saulle R, Croker H, Stansfield C, Packer J, et al. School Closures During Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-being Among Children and Adolescents During the First COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(4):400-9. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Non-pharmaceutical interventions to reduce SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 with relative hospitalization rates [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/canada-communicable-disease-report-ccdr/monthly-issue/2022-48/issue-10-october-2022/effectiveness-non-pharmaceutical-interventions-reduce-sars-cov-2-transmission-canada-association-covid-19-hospitalization-rates.html.

- Mossong J, Hens N, Jit M, Beutels P, Auranen K, Mikolajczyk R, et al. Social Contacts and Mixing Patterns Relevant to the Spread of Infectious Diseases. PLoS Med. 2008;5(3):e74. [CrossRef]

- Haug N, Geyrhofer L, Londei A, Dervic E, Desvars-Larrive A, Loreto V, et al. Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(12):1303-12. [CrossRef]

- Ontario Ministry of Education. Archived - Approach to reopening schools for the 2020-2021 school year [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/approach-reopening-schools-2020-2021-school-year#section-5.

- Ontario Ministry of Education. Archived - COVID-19: Health, safety and operational guidance for schools (2021-2022) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/document/covid-19-health-safety-and-operational-guidance-schools-2021-2022.

- Jarnig G, Kerbl R, van Poppel MNM. How Middle and High School Students Wear Their Face Masks in Classrooms and School Buildings. Healthcare. 2022;10(9). [CrossRef]

- Amin-Chowdhury Z, Bertran M, Kall M, Ireland G, Aiano F, Powell A, et al. Parents' and teachers' attitudes to and experiences of the implementation of COVID-19 preventive measures in primary and secondary schools following reopening of schools in autumn 2020: a descriptive cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2022;12(9):e052171. [CrossRef]

- España G, Cavany S, Oidtman R, Barbera C, Costello A, Lerch A, et al. Impacts of K-12 school reopening on the COVID-19 epidemic in Indiana, USA. Epidemics. 2021;37:100487. [CrossRef]

- Hast M, Swanson M, Scott C, Oraka E, Espinosa C, Burnett E, et al. Prevalence of risk behaviors and correlates of SARS-CoV-2 positivity among in-school contacts of confirmed cases in a Georgia school district in the pre-vaccine era, December 2020-January 2021. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):101. [CrossRef]

- Heinsohn T, Lange B, Vanella P, Rodiah I, Glöckner S, Joachim A, et al. Infection and transmission risks of COVID-19 in schools and their contribution to population infections in Germany: A retrospective observational study using nationwide and regional health and education agency notification data. PLoS Med. 2022;19(12):e1003913. [CrossRef]

- Jain S, Bajaj A, Mohanty V, Arora S, Gangil N, Grover S. Assessing Social Distancing Strategies in Government Schools of Delhi, India: A Formative Research Study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2023;16(1):101-6. [CrossRef]

- Kratzer S, Pfadenhauer LM, Biallas RL, Featherstone R, Klinger C, Movsisyan A, et al. Unintended consequences of measures implemented in the school setting to contain the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;6(6):Cd015397. [CrossRef]

- Krishnaratne S, Littlecott H, Sell K, Burns J, Rabe JE, Stratil JM, et al. Measures implemented in the school setting to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;1(1):Cd015029. [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Pol SJ, Korczak DJ, Coelho S, Segovia A, Matava CT, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Public Health Protocols on Teachers Instructing Children and Adolescents During an In-Person Simulation. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31(2):52-63.

- Littlecott H, Krishnaratne S, Burns J, Rehfuess E, Sell K, Klinger C, et al. Measures implemented in the school setting to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;5(5):Cd015029. [CrossRef]

- Mickells GE, Figueroa J, West KW, Wood A, McElhanon BO. Adherence to Masking Requirement During the COVID-19 Pandemic by Early Elementary School Children. J Sch Health. 2021;91(7):555-61. [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Research to Insights: A look at Canada’s economy and society three years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Sept 15]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-631-x/11-631-x2023004-eng.htm.

- Government of Ontario. Statement from Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Dec 5]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/statement/1001732/statement-from-ontarios-chief-medical-officer-of-health.

- Coleman BL, Gutmanis I, Bondy SJ, Harrison R, Langley J, Fischer K, et al. Canadian health care providers' and education workers' hesitance to receive original and bivalent COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine. 2024;42(24):126271. [CrossRef]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2009.

- Creswell JW, Plano-Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2007.

- Rossman GB, Wilson BL. Numbers and Words:Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Methods in a Single Large-Scale Evaluation Study. Eval Rev. 1985;9(5):627-43. [CrossRef]

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80-92. [CrossRef]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WF. A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. Doing qualitative research. Research methods for primary care, Vol. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1992. p. 93-109.

- Roberts K, Dowell A, Nie J-B. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):66. [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis R. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development: Sage; 1998.

- Proudfoot K. Inductive/Deductive Hybrid Thematic Analysis in Mixed Methods Research. J Mix Methods Res. 2023;17(3):308-26. [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18.5. College Station, TX 2024.

- SocioCultural Research Consultants LLC. Dedoose Version 9.2.22, cloud application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA2024.

- Gershon RRM, Karkashian CD, Grosch JW, Murphy LR, Escamilla-Cejudo A, Flanagan PA, et al. Hospital safety climate and its relationship with safe work practices and workplace exposure incidents. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28(3):211-21. [CrossRef]

- Zohair D. Safety climate in industrial organizations: Theoretical and applied implications. J Appl Psychol. 1980;65(1):96-102. [CrossRef]

- Serrano F, Saragosa M, Nowrouzi-Kia B, Woodford L, Casole J, Gohar B. Understanding Education Workers' Stressors after Lockdowns in Ontario, Canada: A Qualitative Study. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2023;13(5):836-49. [CrossRef]

- Smith PM, Oudyk J, Cedillo L, Inouye K, Potter G, Mustard C. Perceived Adequacy of Infection Control Practices and Symptoms of Anxiety Among In-Person Elementary School Educators in Ontario. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64(11). [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Respiratory infectious diseases: How to reduce the spread with personal protective measures [Internet ]. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/respiratory-infectious-diseases-reduce-spread-personal-protective-measures.html.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hygiene and Respiratory Viruses Prevention [Internet ]. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/prevention/hygiene.html.

- Lau CH, Springston EE, Sohn MW, Mason I, Gadola E, Damitz M, et al. Hand hygiene instruction decreases illness-related absenteeism in elementary schools: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:52. [CrossRef]

- Chang LY, Wang CJ, Chiang TL. Childhood Handwashing Habit Formation and Later COVID-19 Preventive Practices: A Cohort Study. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(8):1390-8. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Hand Hygiene as a Family Activity [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 13]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/clean-hands/prevention/index.html.

- Kim J, Oh S. The relationship between mothers' knowledge and practice level of cough etiquette and their children's practice level in South Korea. Child Health Nurs Res. 2021;27(4):385-94. [CrossRef]

- Howard JT, Howard KJ. The effect of perceived stress on absenteeism and presenteeism in public school teachers. J Workplace Behav Health. 2020;35(2):100-16. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Suh EE, Ju S, Choo H, Bae H, Choi H. Sickness Experiences of Korean Registered Nurses at Work: A Qualitative Study on Presenteeism. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2016;10(1):32-8. [CrossRef]

- Woodland L, Brooks SK, Webster RK, Amlôt R, Rubin GJ. Risk factors for school-based presenteeism in children: a systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):169. [CrossRef]

- Czumbel I, Quinten C, Lopalco P, Semenza JC. Management and control of communicable diseases in schools and other child care settings: systematic review on the incubation period and period of infectiousness. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):199. [CrossRef]

- Richardson M, Elliman D, Maguire H, Simpson J, Nicoll A. Evidence base of incubation periods, periods of infectiousness and exclusion policies for the control of communicable diseases in schools and preschools. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20(4).

- Gravina N, Nastasi JA, Sleiman AA, Matey N, Simmons DE. Behavioral strategies for reducing disease transmission in the workplace. J Appl Behav Anal. 2020;53(4):1935-54. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre F, Ontario College of Teachers. Transition to Teaching 2021: 20th annual survey of Ontario’s early-career elementary and secondary teachers [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.oct.ca/-/media/PDF/transition_to_teaching_2021/2021T2Ten.pdf.

- Woodland L, Smith LE, Webster RK, Amlôt R, Rubin JG. Why do children attend school, engage in other activities or socialise when they have symptoms of an infectious illness? A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2023;13(11):e071599. [CrossRef]

- Donaldson AL, Harris JP, Vivancos R, O'Brien SJ. Risk factors associated with outbreaks of seasonal infectious disease in school settings, England, UK. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e287. [CrossRef]

- Chafloque Céspedes R, Vara-Horna A, Lopez-Odar D, Santi-Huaranca I, Diaz-Rosillo A, Asencios-Gonzalez Z. Absenteeism, Presentism and Academic Performance in Students from Peruvian Universities. Propósitos y Representaciones. 2018;6(1):109-33. [CrossRef]

- Komp R, Kauffeld S, Ianiro-Dahm P. Student Presenteeism in Digital Times-A Mixed Methods Approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24). [CrossRef]

- Bornand E, Letourneux F, Deschanvres C, Boutoille D, Lucet J-C, Lepelletier D, et al. Social representations of mask wearing in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Constantino SM, Grenfell BT, Weber EU, Levin SA, Vasconcelos VV. Sociocultural determinants of global mask-wearing behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(41):e2213525119. [CrossRef]

- Duong D. Calls for masking in schools as respiratory infections overwhelm children’s hospitals. CMAJ. 2022;194(47):E1619. [CrossRef]

- Neumann M, Moore ST, Baum LM, Oleinikov P, Xu Y, Niederdeppe J, et al. Politicizing Masks? Examining the Volume and Content of Local News Coverage of Face Coverings in the U.S. Through the COVID-19 Pandemic. Polit Commun. 2024;41(1):66-106. [CrossRef]

- Scoville C, McCumber A, Amironesei R, Jeon J. Mask Refusal Backlash: The Politicization of Face Masks in the American Public Sphere during the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Socius. 2022;8:23780231221093158. [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Pandemic fatigue: Reinvigorating the public to prevent COVID-19 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 1]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/337574/WHO-EURO-2020-1573-41324-56242-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Brankston G, Merkley E, Loewen PJ, Avery BP, Carson CA, Dougherty BP, et al. Pandemic fatigue or enduring precautionary behaviours? Canadians’ long-term response to COVID-19 public health measures. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2022;30:101993. [CrossRef]

- Crane MA, Shermock KM, Omer SB, Romley JA. Change in Reported Adherence to Nonpharmaceutical Interventions During the COVID-19 Pandemic, April-November 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(9):883-5. [CrossRef]

- Delussu F, Tizzoni M, Gauvin L. Evidence of pandemic fatigue associated with stricter tiered COVID-19 restrictions. PLOS Digit Health. 2022;1(5):e0000035. [CrossRef]

- Keeley JM, Sato A, Marizen RR, Gillian AMT. Psychological distress as a driver of early COVID-19 pandemic fatigue: a longitudinal analysis of the time-varying relationship between distress and physical distancing adherence among families with children and older adults. BMJ Public Health. 2024;2(2):e001256. [CrossRef]

- Petherick A, Goldszmidt R, Andrade EB, Furst R, Hale T, Pott A, et al. A worldwide assessment of changes in adherence to COVID-19 protective behaviours and hypothesized pandemic fatigue. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(9):1145-60. [CrossRef]

- Rader B, Sehgal NKR, Michelman J, Mellem S, Schultheiss MD, Hoddes T, et al. Adherence to non-pharmaceutical interventions following COVID-19 vaccination: a federated cohort study. NPJ Digit Med. 2024;7(1):241. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Lu Y, Jiang B. Built environment factors moderate pandemic fatigue in social distance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide longitudinal study in the United States. Landsc Urban Plan. 2023;233:104690. [CrossRef]

- Bardosh K, Figueiredo Ad, Gur-Arie R, Jamrozik E, Doidge J, Lemmens T, et al. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(5):e008684. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic |

Participants N = 3617 |

| Age in years, mean (95% CI) | 45.3 (45.0, 46.0) |

|

Gender Female Male Other |

3091 (85.5) 517 (14.3) 9 (0.2) |

|

Education, highest achieved Diploma, college, or less Bachelor's degree/teaching certification Graduate school (Master's or PhD) |

341 (9.4) 2441 (67.5) 835 (23.1) |

|

Occupation Teacher Educational assistant Early childhood educator Principal / vice principal Administration1 Professional student services roles2 Support staff3 |

2923 (80.8) 224 (6.2) 80 (2.2) 133 (3.7) 87 (2.4) 130 (3.6) 40 (1.1) |

|

Chronic illness4 Yes No |

921 (25.5) 2696 (74.5) |

|

Postal district Eastern Ontario Central Ontario Metropolitan Toronto Southwestern Ontario Northern Ontario |

643 (17.8) 1251 (34.6) 721 (19.9) 831 (23.0) 171 (4.7) |

|

School setting Elementary Secondary Both / mixed setting |

2227 (61.6) 1103 (30.5) 287 (7.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).