2. Digital Energy and AI

2.1. Policy Context

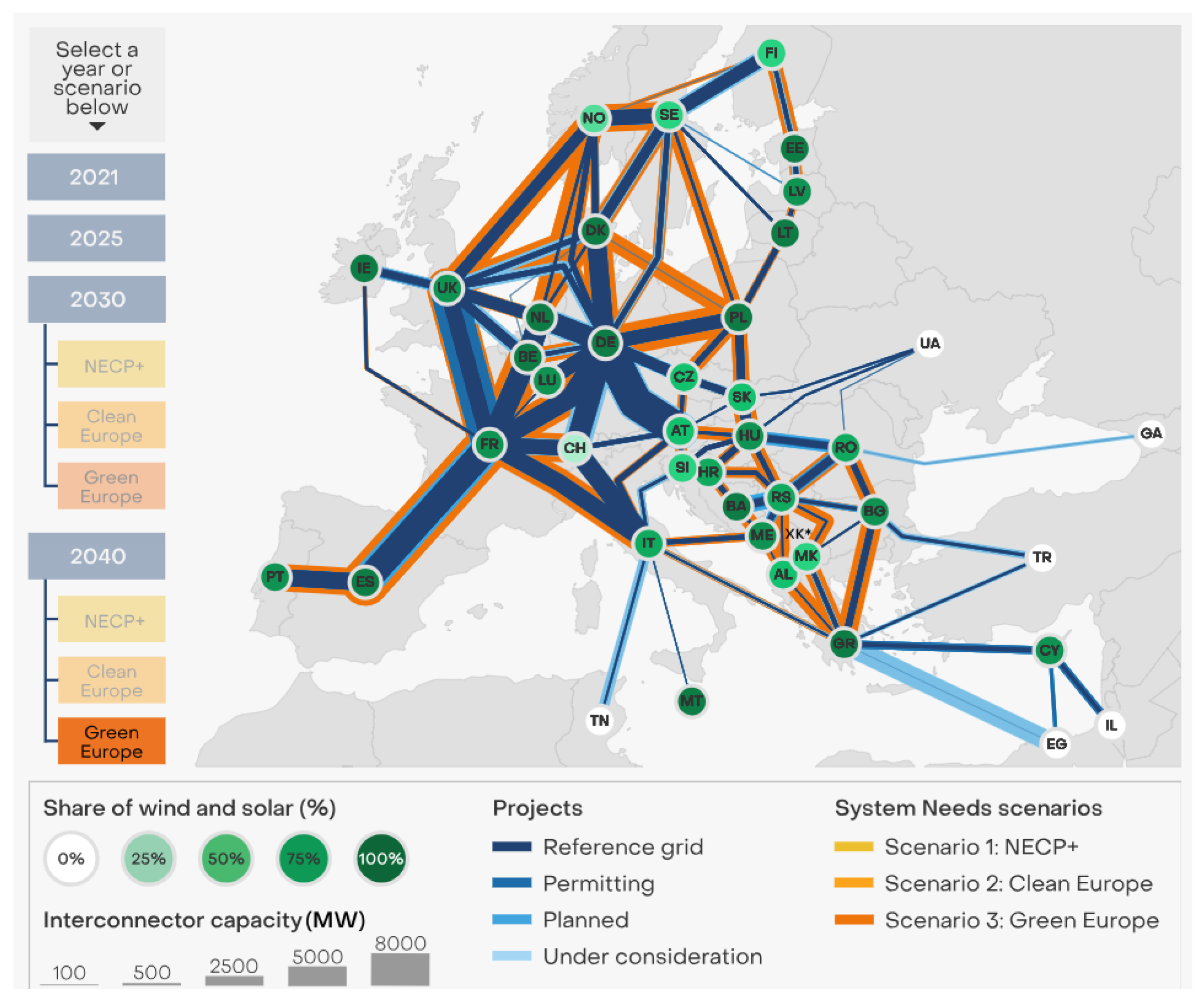

The European Network of Transmission System Operator for Electricity remains critical and issues recommendations (ENTSO-E) [

21]. Transmission System Operators (TSOs) from 40 Members and 36 countries are part of ENTSO-E. The document clearly defines two problems: the level of investment in network infrastructure, which has remained unchanged since 2010 (around

$300 billion per year), and the long timeframe for modernizing and rehabilitating the network. This implies the need for significant investments in networks while maintaining the security and efficiency of the system. ENTSO-E`s Roadmap 2024 – 2034 recommends as an urgent measure for the next decade the digitalization of the energy systems of the participating countries in order to better monitor, control and manage the hybrid electricity networks [

22]. Main innovation drivers in this direction according ENTSO-E Roadmap 2024 – 2034 are system digitalization, DTs, cybersecurity, AI-based technology, RES and load forecasting, monitoring and data management, IoT devices and metering and smart grid innovative tools. By 2034, the aim is to enhance grid utilization and sustainability through interoperability, integrated and standardized solutions, adoption of real-time data sensors and IoT devices for more efficient, cost-effective and secure remote monitoring, DTs to optimize maintenance and replacement of assets in service, standardization of asset management approaches [

23],

Figure 1.

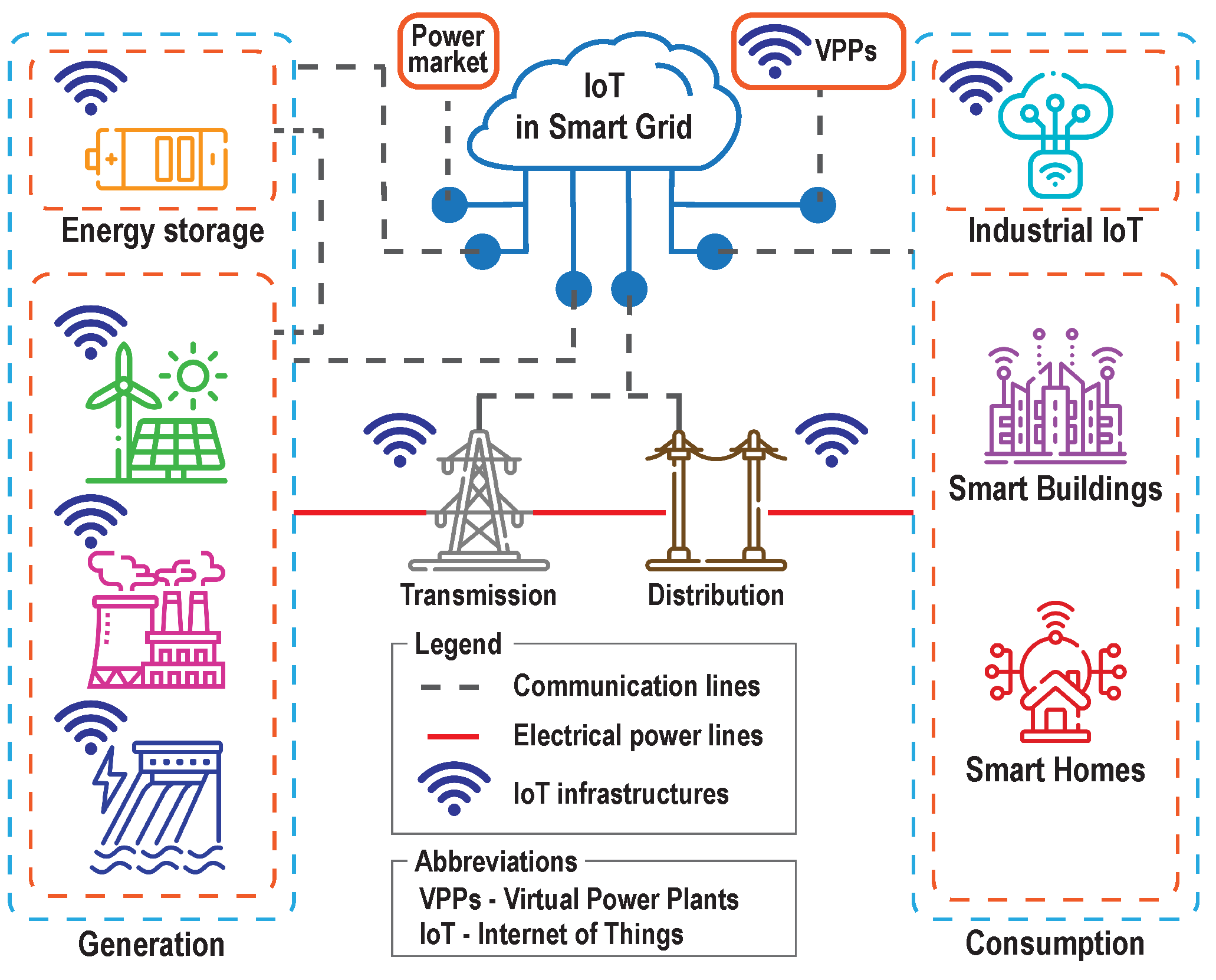

As far as the RES sector is concerned, digital technologies can help the sector in several ways: better monitoring, operation and maintenance of renewable energy facilities; more precise and real-time operation and control; introduction of new market and business models for energy exchange and distribution. IRENA analysts predict a future with a large share of RES, with three groups of AI technologies embedded: 1) IoT; 2) AI and Big Data; and 3) Blockchain. The analysis shows that none of them is sufficient on its own, but rather reinforce each other as part of a toolkit of digital solutions to optimize the operation of an increasingly complex system of RES [

24]. When considering the dynamic process of decentralization of energy systems through the implementation of distributed energy generation and battery energy storage, IoT holds significant potential for new management capabilities and business models. Future decentralized energy systems can realize their potential at the micro level as energy providers with guaranteed power quality indicators, however, they require monitoring, control and intelligent management [

25]. IoT devices meet these requirements and can help create "smart grids" by collecting, transmitting, and using large amounts of data, intelligently integrating users connected to the grid, optimizing grid performance, and increasing system flexibility. As energy systems progressively become more complex and decentralized, IoT applications improve the visibility and responsiveness of grid-connected devices. IoT plays a pivotal role in the convergence of Big Data and AI. The integration of the IoT into energy structures offers a multitude of benefits that extend along the entire chain: generation forecast – automated control and grid reliability and stability – aggregation, control, automated demand-side management – interconnection of mini-grids operation – optimized market formation. The forecasts for 2025 according to [

25], are 75 billion devices connected worldwide, most IoT projects in the power sector focus on demand-side applications (e.g., smart homes). It is expected that this digitalization will lead to a reduction of the operational and maintenance costs (O&M), boost renewable power generation and reduction of renewable energy curtailment. Advancements in communication procedures and protocols are essential for ensuring the high technological maturity, reliability, and cybersecurity of data exchange channels.

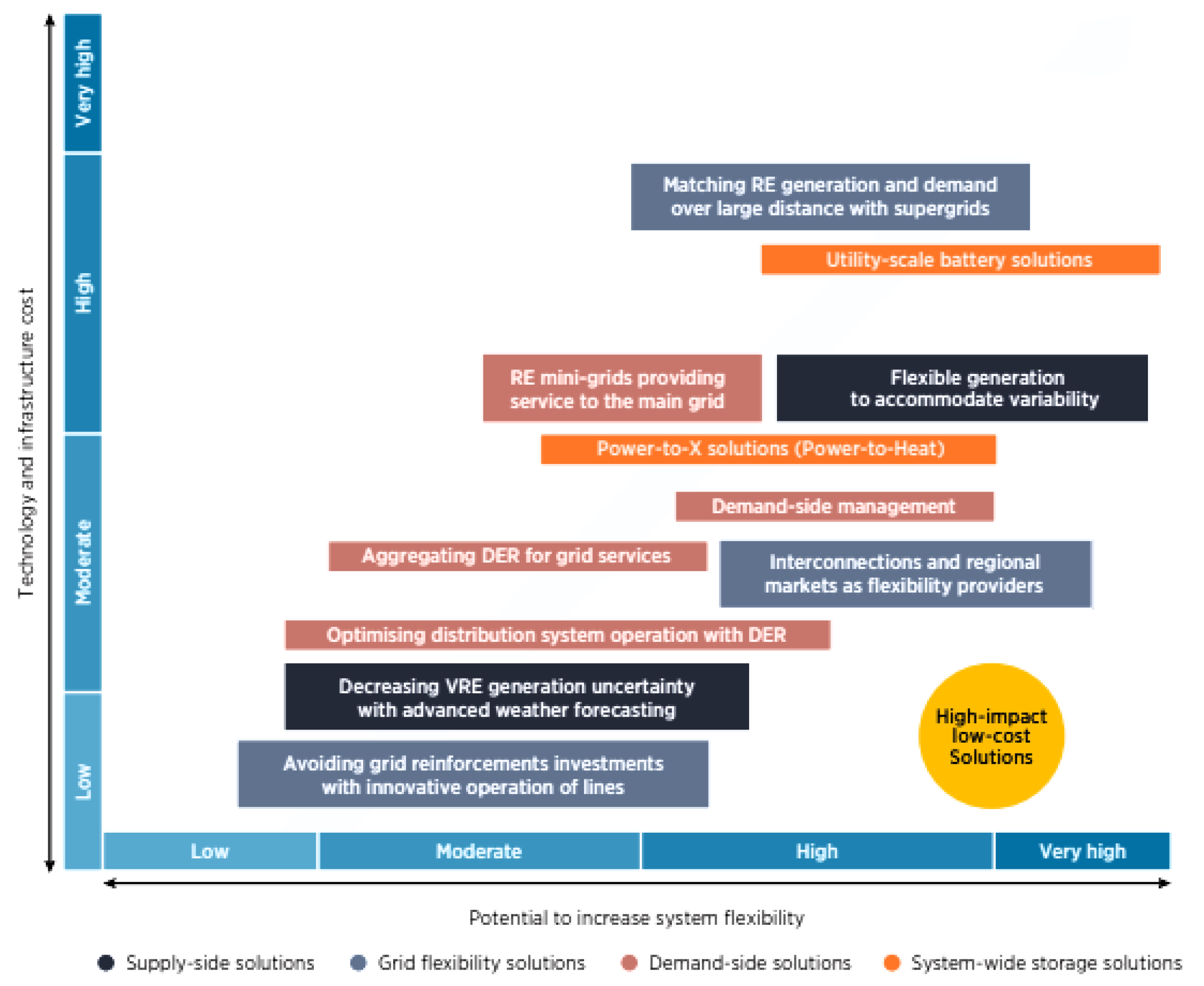

The IoT also brings solutions to optimise systems on both the supply and demand sides, leading to enormous opportunities for the integration of larger shares of variable renewable generation into the system. Variable renewable generation (VRG) or variable renewable energy (VRE) is a concept and term that encompasses the increasingly dynamic introduction of RES into the structures of electricity distribution networks. IRENA project “Innovation landscape for a renewable-powered future” maps the relevant innovations, identifies the synergies and formulates solutions for integrating high shares of VRE into power systems [

25,

26,

27]. Some examples of flexibility solutions being implemented in different countries: Supply-side flexibility (Germany); Grid flexibility (Denmark); Demand-side flexibility (United States); System-wide storage flexibility (Australia) etc. System-wide and demand-driven solutions continue to be the most expensive in terms of technology and infrastructure,

Figure 2.

Some important IoT technical implementation requirements come down to:

Hardware: smart meters with high-resolution metering data and sensors; sensors installed in different devices; supercomputers or “cloud technology”; other digital technologies add automated control to the electricity system to increase flexibility and manage multiple sources of energy flowing to the grid from local energy resources.

Software: data collection, data pre-processing, processing, testing; optimisation tools; software for version control, data storage and data quality assessment.

Communication protocol: common interoperable standards (at both the physical and the information and communication technology (ICT) layers); define cybersecurity protocols.

The necessary regulatory requirements (wholesale and retail market, distribution), roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in the context of energy system operators and owners/operators of distributed energy resources remain on the agenda.

AI potential is being unlocked by the generation of big data and increased processing power. In the energy sector, AI can enable fast and intelligent decision making, leading to increased grid flexibility and integration of VRE. Many useful solutions and examples are given in [

28]: EWeLiNE and Gridcast in Germany use AI to better forecast solar and wind generation, minimizing curtailments; DeepMind AI has reduced cooling consumption at a Google data centre by 40%. It applies machine learning to increase the centre’s energy efficiency; EUPHEMIA, an AI-based coupling algorithm, integrates 25 European day-ahead energy markets to determine spot prices and volumes etc. Big data and AI can produce accurate power generation forecasts that will make it feasible to integrate much more renewable energy into the grid. Accurate VRE forecasting at shorter time scales can help generators and market players to better forecast their output and to bid in the wholesale and balancing markets, while avoiding penalties. For system operators, accurate short term forecasting can improve unit commitment, increase dispatch efficiency and reduce reliability issues, and therefore reduce the operating reserves needed in the system. Accurate demand forecasting, together with renewable generation forecasting, can be used to optimize economic load dispatch as well as to improve demand-side management and efficiency. With the help of "smart contracts," blockchain has the potential to play an important role in supporting the integration of renewable energy sources by automating processes, increasing the flexibility of the power system, and reducing transaction costs. At the same time, blockchain technologies can accelerate the exchange between storage systems and electric vehicles (EVs). Thus, V2G and G2V models can improve the management of the grid and the operation of energy structures that contain charging stations [

29].

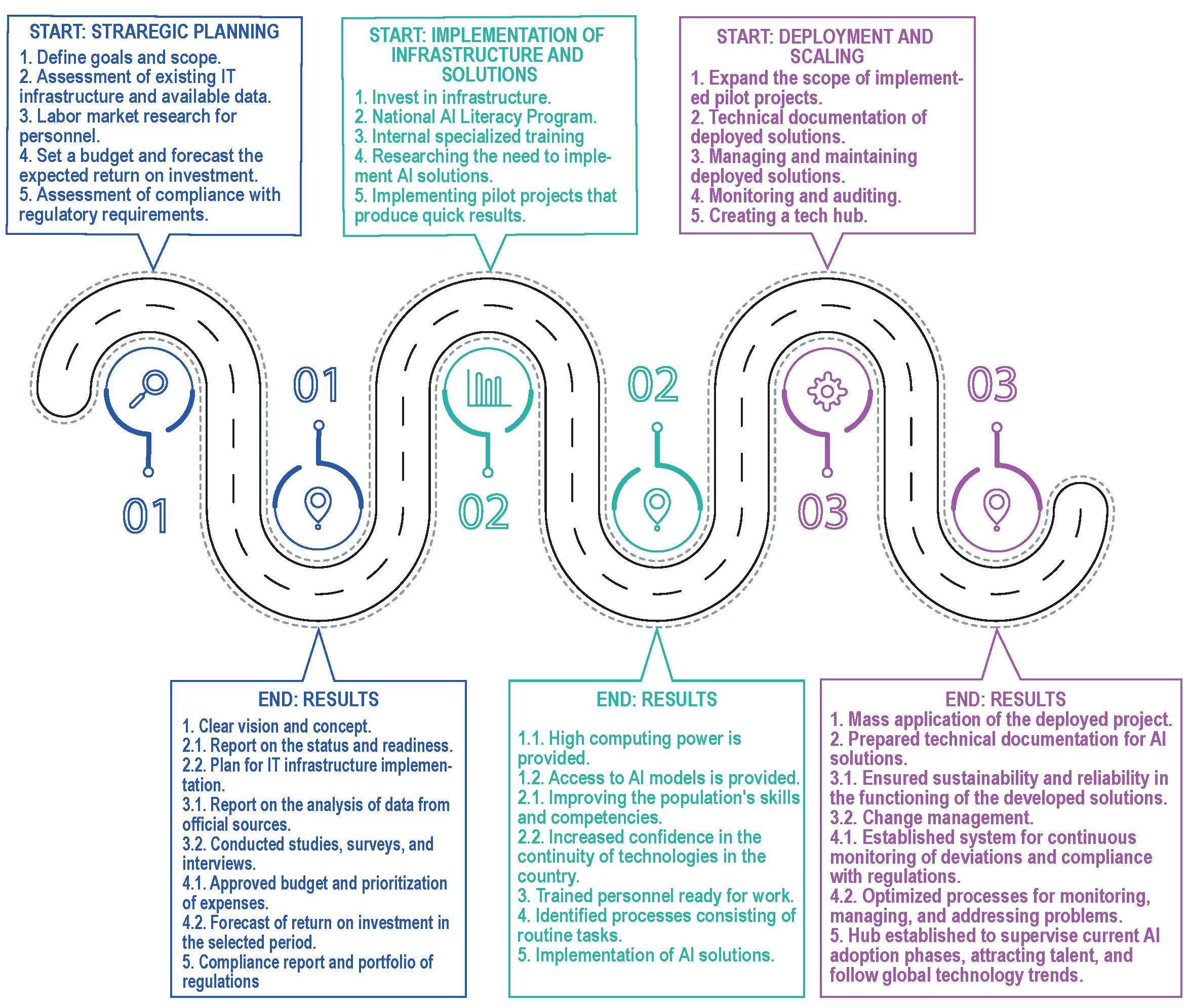

Considering everything discussed so far, the authors propose a Roadmap of AI Adoption in general case,

Figure 3.

2.2. Enabling Technologies

AI is a field of computer science that deals with the creation of intelligent agents - systems that can reason, learn, and act autonomously. Intelligent agents are systems that can perceive their environment and take actions that increase their chances of achieving a goal. They can learn from experience and adapt their behavior over time. AI is about building intelligent machines that can compute how to act effectively and safely in new situations [

30].

There are two main approaches to AI: Machine Learning (ML) - approach that involves training algorithms on large amounts of data. Algorithms learn to identify patterns in the data and use these patterns to make predictions or decisions; Deep Learning (DL) - approach that has been very successful in tasks such as image recognition, natural language processing, and speech recognition.

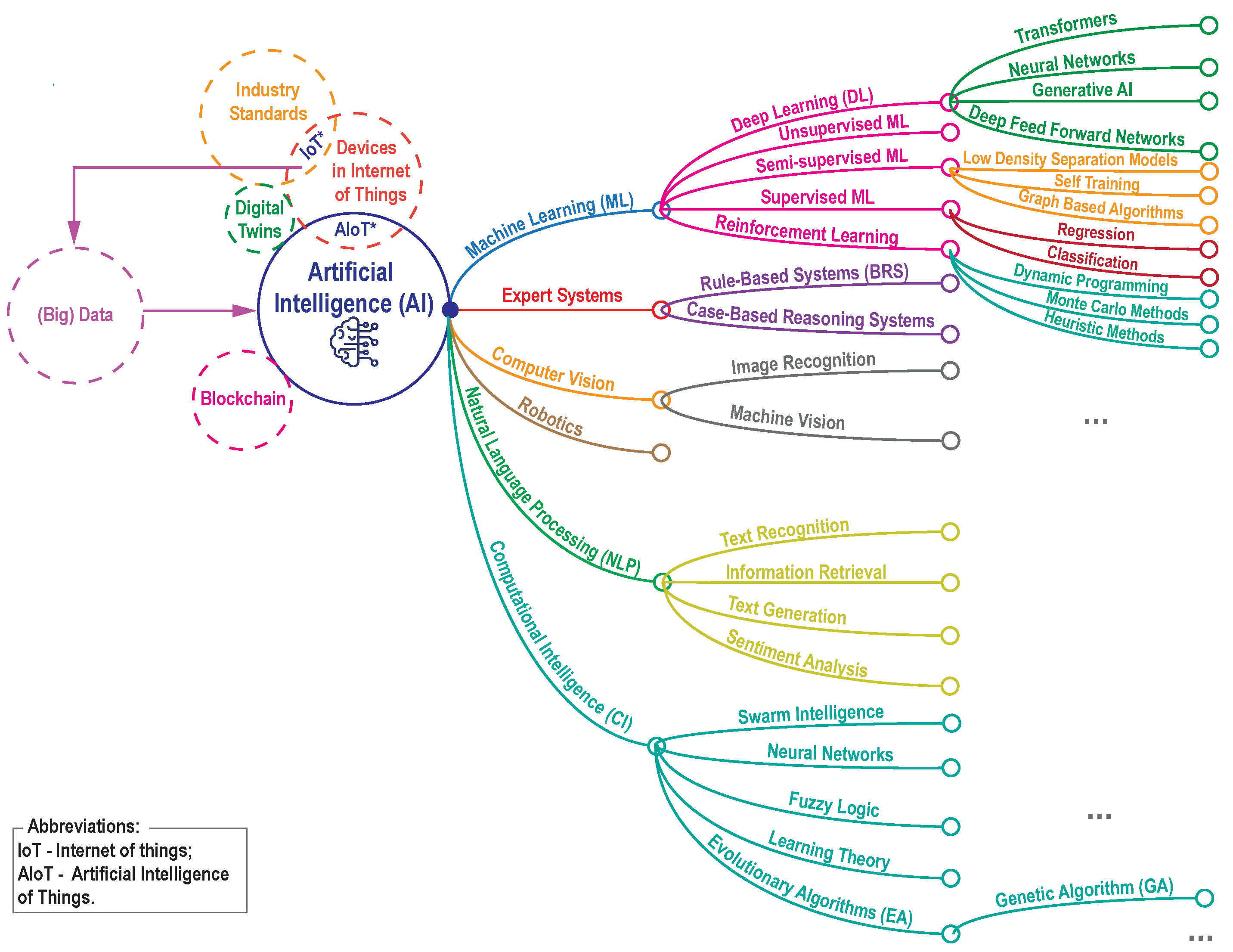

In order to further illustrate the interrelationship between the various subcategories of AI and their interplay with certain components of the digitalization of energy systems, as discussed in this paper, the authors propose the following graphic,

Figure 4, based on the materials [

31,

32,

33,

34].

Note: The figure provides an overview of some basic types of AI. Within these categories, there are numerous other AI technologies and subfields, as well as opportunities for combinations between them. AI research is a dynamic field, with new advances continually emerging.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the domain of AI, represented as central node, encompasses a broad spectrum of interlinked scientific fields, systems, and technologies:

ML - algorithms that can learn from data and perform tasks such as identifying patterns, making predictions or decisions without explicit instructions;

Expert Systems - computer programs designed to simulate the decision-making ability of a human expert. They utilize knowledge bases and inference engines to solve complex problems;

Computer Vision - the ability for computers to "see" and interpret information from images or videos. It involves algorithms that process and understand visual data;

Robotics - the field of design, construction, operation, and application of robots. It combines elements of engineering, computer science, and AI to create automated machines;

Natural Language Processing (NLP) - deals with enabling computers to understand, interpret, and generate human language. It combines computational linguistics with ML and DL to process and analyze text and speech;

Computational Intelligence (CI) - focuses on biologically inspired computing paradigms. It often involves techniques like neural networks, fuzzy systems, and evolutionary computation.

The figure also presents several concepts interrelated or adjacent to AI in the context of energetics, such as:

Data or Big Data - AI relies heavily on large datasets for training and analysis;

Blockchain - used for secure and transparent AI applications;

Industry Standards - standardization in AI development and deployment;

Devices in Internet of Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) - integrating AI into IoT devices and systems;

DTs - creating virtual replicas of physical systems for analysis and optimization.

These technologies work together in a powerful synergy. IoT devices generate big data that feeds the AI algorithms. AI powers DTs, which are virtual representations of physical entities. Blockchain technology ensures the security and trust of data and transactions within this ecosystem. Big data, IoT, blockchain, and DTs are all interconnected and play a crucial role in the advancement of AI. Together, these technologies provide the data, the virtual environments, and the trust that are necessary for AI to reach its full potential and transform industries.

The assumptions are that AI will undergo three distinct evolutionary phases of development: Artificial narrow (limited) intelligence (ANI), Artificial general intelligence (AGI), and Artificial superintelligence (ASI). Currently, we are surrounded by the first type of AI, ANI, which performs specific tasks but lacks the capacity to extend its functionality independently. ANIs outperform humans in certain routine activities or strictly typed tasks and improve performance. By 2040, it is anticipated that AI will have evolved to AGI systems. AGI systems are expected to possess intellectual capabilities comparable to those of humans. They will be capable of performing a wide range of tasks, competing with humans, and even taking away jobs. Following the evolution of generalized intelligence systems, AI is expected to evolve to ASI. Systems with superintelligence are anticipated to have higher intellectual capabilities than humans and to outperform humans [

35].

2.2.1. AI and ML Fundamentals

The integration of data analytics and machine learning into renewable energy, energy efficiency and grid management can yield benefits. Energy systems can be equipped with devices that consider multiple parameters during their operation. The development of technology in recent years has provided increasing opportunities for these measuring devices to be connected via networks, allowing for real-time remote monitoring and the subsequent analysis of reported data.

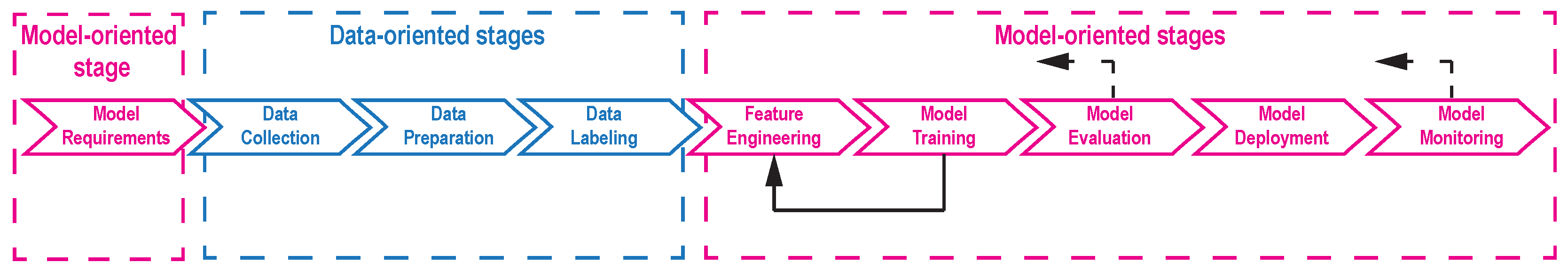

The process of data analysis involves the collection, cleansing, supplementation, and processing of data in order to identify patterns, trends, and relationships. When presented in an appropriate format, data can provide valuable insights into the performance of the system itself, as well as trends, tendencies, or prerequisites for its optimization. ML algorithms are well-suited for the analysis of large datasets, with the objective of predicting future events or the expected behavior of a system under specific conditions and external influences. The nine stages of the ML workflow are depicted in

Figure 5.

The stages of the workflow are divided into two categories: data-oriented (marked in blue) and model-oriented (marked in pink). There are numerous feedback loops within this workflow. The dotted feedback arrows indicate that model evaluation and monitoring can return to some of the previous stages. The solid feedback arrow illustrates that model learning can go back to the feature engineering stage. The main stages are as follows:

Model Requirements: At the outset of the process, the problem to be solved and the objectives of the machine learning model are delineated. It is of paramount importance to establish realistic expectations and metrics for success at this stage.

Data Collection: The raw data on which the model will be trained is collected. This usually involves aggregating data from a variety of sources and ensuring that it meets the requirements of the model in question.

Data Preparation: Ensuring data integrity is fundamental to the success of machine learning. Real-world data is often characterized by inconsistencies or missing values. At this stage, the following techniques can be applied to improve data quality for subsequent training: data cleaning, data validation, missing data handling, data duplication (creating synthetic data), and data normalization. The data can be further divided into different subsets, such as training data and test data for model training and model evaluation.

Data Labeling: If the specific model requires labeled data (e.g., identifying objects in images), this stage involves labeling the data entries.

Feature Engineering: Often the raw data cannot be used directly by the model. This stage involves transforming the data into features that the model can understand and learn from.

Model Training: The model is trained on the prepared data, allowing it to learn patterns and relationships.

Model Evaluation: Following training, the performance of the model is evaluated on data it did not receive during its training (test dataset) to assess its accuracy. If the evaluation is unsatisfactory, it is necessary to return to a previous stage.

Model Deployment: If the evaluation is satisfactory, the model can be deployed into production for use in real-world conditions. This involves further integration into an existing application or system.

Model Monitoring: An important part of the developing lifecycle of ML is the monitoring of its performance over time, even after deployment. This enables the identification of any issues or a decline in accuracy, allowing for the implementation of corrective measures, such as retraining, if necessary.

The utilization of a machine learning application is an iterative process. As data undergoes changes, user preferences evolve, and competition intensifies, it is important to keep the model up to date after implementation. While the same level of training as during the initial development phase is not typically necessary, it is unreasonable to expect the model to maintain the same level of efficiency throughout its entire lifespan. Consequently, ongoing training and adaptation are essential to maintain the model’s effectiveness and ensure its continuous usability [

36]. Only models trained on real data can be considered reliable [

37].

2.2.2. Transformers and Large Language Models

Large language model (LLM) are type of advanced AI systems representing a type of ML model. They are designed for NLP tasks, trained on large text datasets or through self-supervised learning to understand and generate human-like language [

38]. They acquire the predictive ability inherent in human language, but they also inherit the inaccuracies and biases present in the data on which they are trained. They use DL techniques, in particular transformer architectures, to process and produce text, allowing them to perform tasks such as translation, summarization, and question answering [

39,

40].

A major challenge in large language models is the performance gap between open-source models [

41,

42,

43,

44] and closed-source models [

45,

46]. In contrast, giant closed-source models, while powerful, are often inaccessible to many researchers and developers due to their proprietary nature [

47].

The beginning of open source models was in 2023, when Meta released Llama, available for research purposes [

48,

49,

50], which sparked interest due to the need for transparency, accessibility and customizability. It also contributed laying the foundations for open source LLMs. In July 2023, the Chinese AI startup DeepSeek [

51] released its first model. A couple of years later, in 2025, the company gained international attention with DeepSeek R-1, an open-source LLM with high performance and affordability compared to similarly parameterized but closed-source models.

Figure 6 and

Table 1 shows the intelligence-to-cost ratio, price calculated in USD per 1M Tokens, for 18 LLMs developed by 9 companies leaders in the field: OpenAI [

52,

53,

54], Meta [

55,

56], Google [

57], Anthropic [

58,

59], Mistral [

60,

61], DeepSeek [

62], Amazon Web Services (AWS) [

63], Cohere [

64], Alibaba Group [

65]. These are just some of the versions of these LLMs, data for which was provided by Artificial Analysis with an independent AI analysis ranking company [

66].

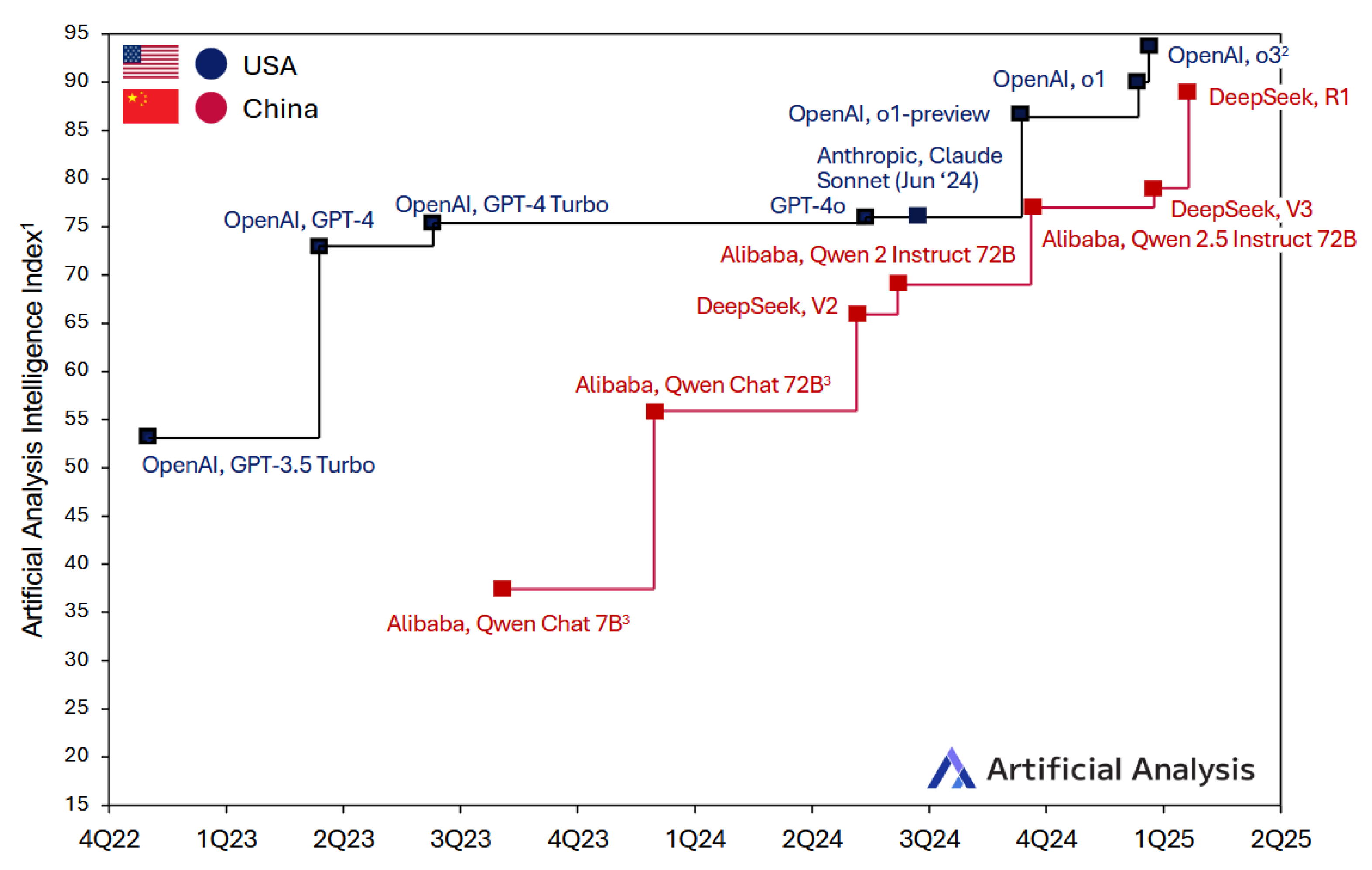

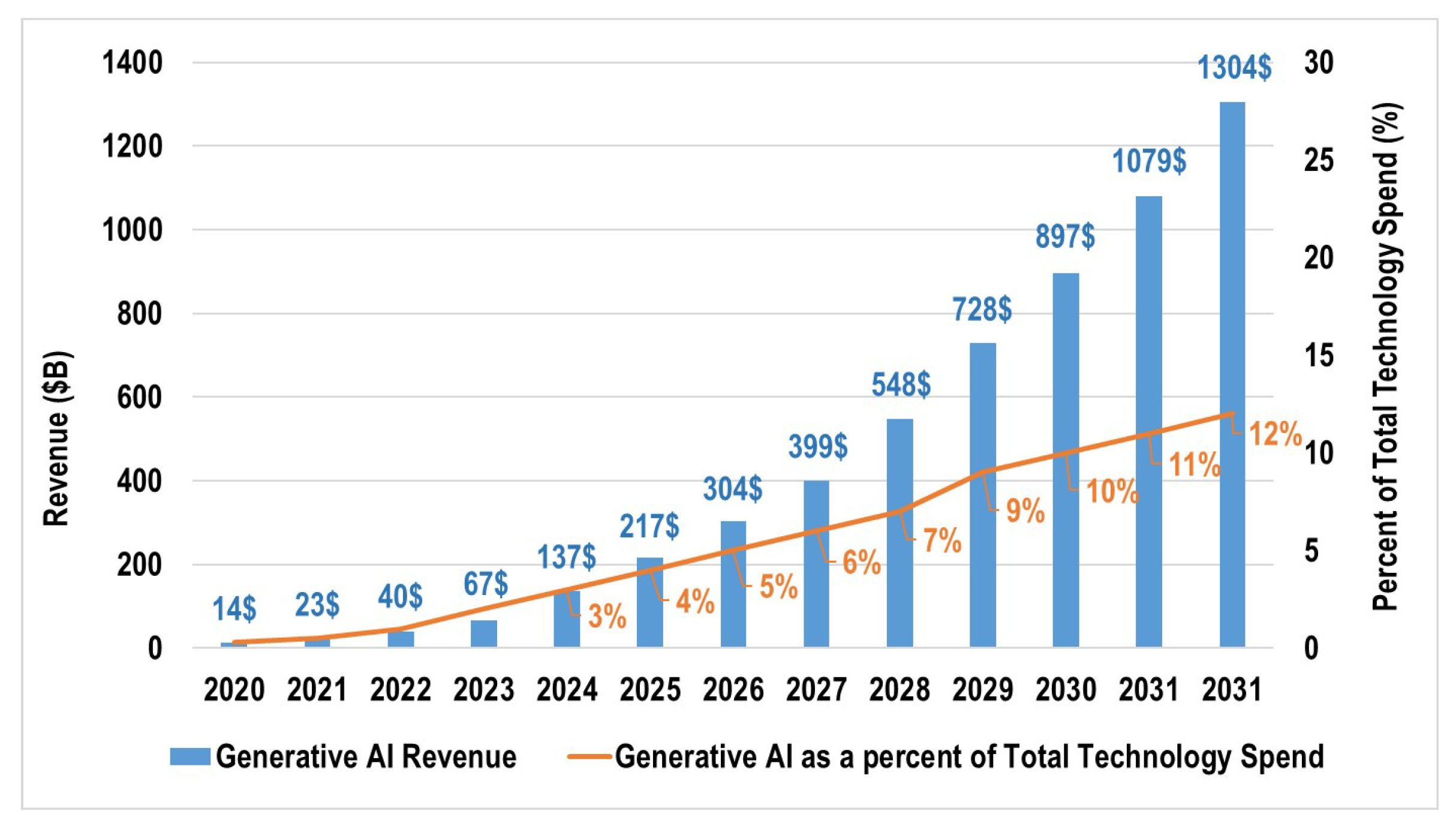

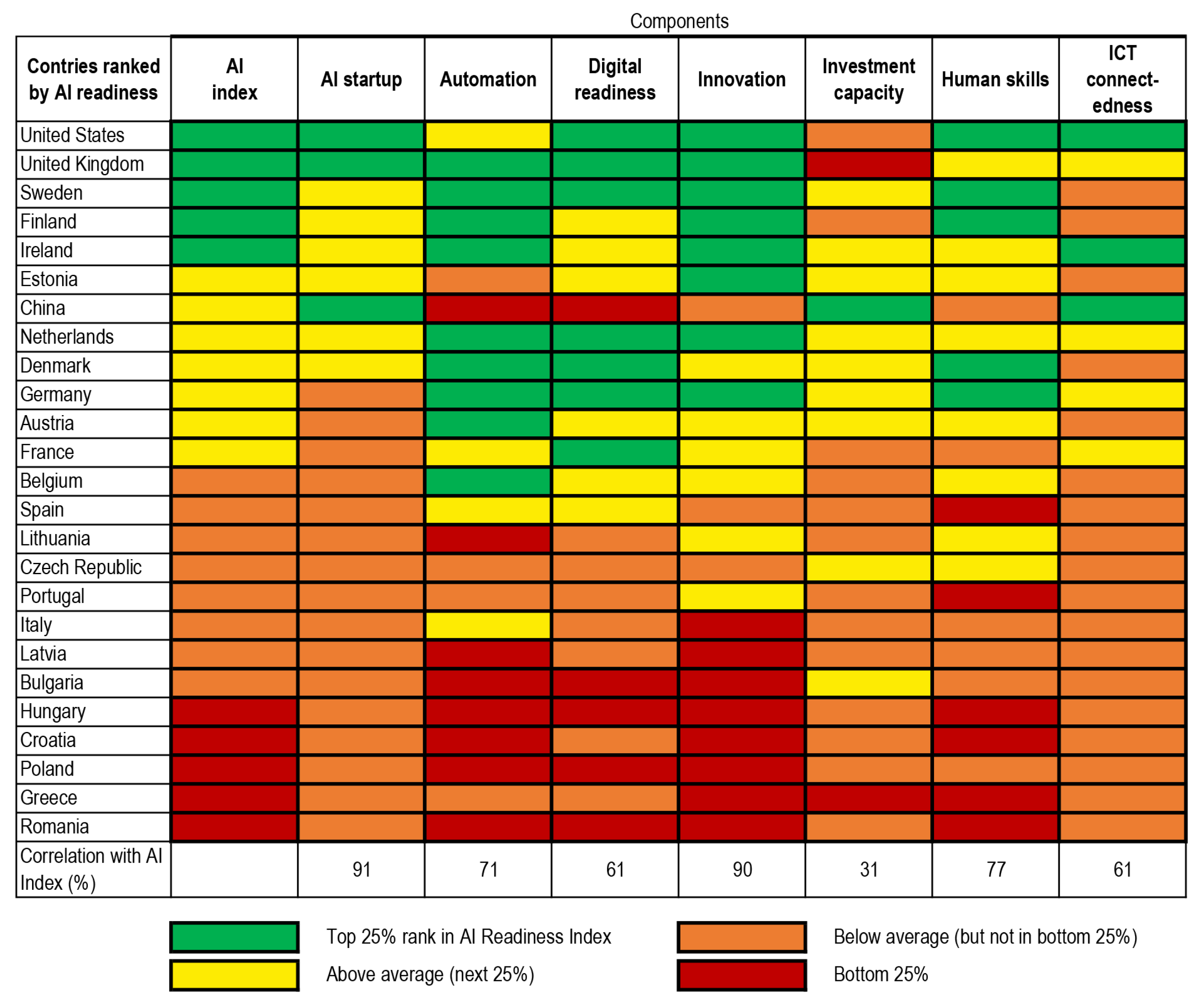

Due to the rapid development of the AI sector, as well as economic and strategic considerations, there is a lack of statistics that well summarize the technological progress of all countries around the world. In their report, the company Artificial Analysis [

67] provide an update and trends as of the first quarter of 2025 on the development of LLMs around the world,

Figure 7.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence models, such as OpenAI o1, OpenAI deep research [

68], and DeepSeek-R1, DeepSeek-R1-Zero [

62], highlight the growing ability of LLMs to perform multi-stage research and reasoning in complex domains. DeepSeek’s R1 model is very competitive and could outperform leading US developments in some aspects. Within a few months, Chinese competitors have largely replicated the intelligence of OpenAI’s o1.

OpenAI’s deep learning model explores advanced training techniques and reinforcement learning methods to enhance AI capabilities by leveraging reasoning to search, interpret, and analyze large amounts of online data, responding to real-time information as needed. As a result of this training, the model has a significantly improved ability to evaluate real-world problems, resembling a human-like approach. In spite of the encouraging results, Open AI has indicated that presently, the model still exhibits some minor limitations in its ability to discern reliable information and avoid incorrect inferences.

Similarly, the open-source DeepSeek-R1-Zero and DeepSeek-R1 models demonstrate advanced reasoning capabilities by leveraging large-scale reinforcement learning without using supervised fine-tuning (SFT) as a precursor, enabling self-checking, reflection, and long chain-of-thought (CoT) generation and improving upon drawbacks such as endless repetition and poor readability. In particular, it is the first open research to validate that the reasoning capabilities of LLMs can be initiated by reinforcement learning alone, without the need for Supervised Fine Tunning (SFT). The release of the source code has provided the research community with valuable tools to enhance reasoning performance and advance AI-driven knowledge synthesis [

62,

68]. These LLMs have self-correcting behaviors [

69] and focus on deep research with improving the reasoning process of AI. This is in contrast to the previous paradigm of merely scaling up the size of the model to improve performance, and it is a step forward in the evolution of AI to generalized intelligence [

70].

Impression from

Figure 7 for DeepSeek R1 is the price-intelligence ratio of 0.96 USD per 1 million tokens and an intelligence index of 60.17, compared to OpenAI’s o1 price of 26.25 USD per 1 million tokens and an intelligence index of 61.89. DeepSeek-R1 shows a considerable performance to cost ratio, competing with OpenAI, which continues to excel in terms of security and overall performance.

Based on the information presented, the following conclusions can be drawn: the development of frontier LLMs is primarily centered in China and the USA. While the Chinese AI labs officially released their LLMs in 2023, their models are approximating the intelligence level of the US ones; Choosing the optimal LLM for a specific purpose should be tailored to a number of factors such as open/close source code, application domain and capabilities, intelligence, training costs, price, performance (latency and output speed, response time etc.).

2.2.3. Autonomy and Decision-Making in AI Systems

AI systems are becoming increasingly sophisticated, which raises questions about their level of autonomy and how they make decisions. Autonomy is the ability of AI to make choices and take actions independently of human intervention. Levels of autonomy can vary from basic recommendations to autonomous decision-making in critical situations. Most current AI systems fall somewhere in between. Different levels of autonomy can be defined, such as:

Supervised Learning. These types of systems require human input and supervision for each decision. Supervised learning is a ML method in which the algorithm is trained on a data set containing both input data and desired output values (solutions designated as labels). Labels are features that have been assigned a specific meaning within the context of the data set. The goal of training is to identify a model that can be used to predict labels for new data that is unknown to the algorithm. Depending on the type of input data, supervised learning can provide the result as classification and regression [

30,

36,

71].

Semi-supervised Learning. AI is capable of making autonomous decisions, although it requires human guidance for more complex tasks. Many of these types of algorithms are combinations of supervised learning and unsupervised algorithms. [

71] This is due to the fact that the method deploys a combination of labeled and unlabeled data to train the model. The labeled data is utilized to direct the training process, whereas the unlabeled data is used to enhance the model and improve its generalizability. This approach is a common one, with the rapid labelling of some of the data enabling ML (semi-supervised learning systems) to make more effective use of the remaining unlabeled data [

30].

Reinforcement Learning. AI learns through trial and error within a set of rules and rewards. However, it may not fully understand the reasons for its decisions. In reinforcement learning, the system can observe the environment, choose and perform actions, and receive rewards or punishments in return. It must then learn on its own which is the best strategy (policy) to get the most rewards over time. The policy determines what action it should choose when it is in a given situation [

71].

Autonomous Systems. AI is capable of making decisions and taking actions autonomously, within the pre-defined parameters and based on its understanding of the environment.

Autonomy and the ability to make decisions independently are powerful tools in AI. However, they must be carefully considered and developed to ensure that their use is responsible. As AI systems become increasingly complex, questions arise about the level of autonomy they possess and the influence they exert on decision-making.

2.3. Use Cases in Energy

AI offers a variety of opportunities for use in the transforming energy sector that can improve efficiency, optimize operations, and ensure sustainability. The integration of AI technologies in the energy sector is still in its early stages, yet their influence on energy production, transmission, distribution, and consumption is becoming increasingly apparent with each implementation. In addition to the conventional predictive tasks of repairing, servicing, and maintaining electrical equipment, new specific areas are emerging in the energy industry. The development in these areas is of interest and importance due to their impact on critical energy infrastructure and the relationships with in these structures. The deployment of AI technologies in the agile energy industry is deployed in five main directions:

First direction: Forecasting electricity generation from RES: wind and solar power plants. AI is widely used in forecasting renewable energy generation. The fluctuations in the processes of solar and wind power generation present a challenge to effective grid management. The AI machine learning models can analyze historical data, weather patterns, and sensor readings in real time to predict power generation with sufficient accuracy. This enables grid operators to integrate renewable energy sources in a more efficient manner and improves the balance between supply and demand. The processing of data from meteorological maps, satellites and weather stations by means of neural networks enhances the forecasting of the amounts of electricity generated by solar and wind power plants. The data about the expected energy production of renewable energy facilities allows more effective planning of the load of the fuel-powered plants and the operational modes of the electricity transmission network. Furthermore, data about fluctuations in the volume of energy flows produced by renewable energy sources make it possible to forecast more accurately the price levels on the spot electricity market. RES have substantial initial capital costs, but no ongoing expenses for energy carriers or fuels. Consequently, substantial quantities of less expensive electrical energy can exert considerable downward pressure on market prices at relevant time intervals. This approach is employed by companies such as: Xcel Energy (electricity supplier company in Colorado, USA); Nnergix (Spain), which has developed a web-based algorithm that collects and examines weather and energy supplier data through ML; Meteo-Logic (Tel Aviv, Israel), which specializes in the analysis of annual energy quantities and price trends. The company can use large data sets to train ML and create algorithms that increase the accuracy of predictive models of generated quantities and adequate power supply. IBM has demonstrated an AI technology that improves predictive models by 30%. This technology combines predictive models with big datasets on weather, environmental and atmospheric conditions and the performance of solar and other power plants. The forecast range is 15 minutes to 30 days. The developers claim that it outperforms other solar activity forecasting models by 50% in accuracy. At the same time, data obtained by a group of researchers from Peshawar University of Engineering and Technology indicates that the use of neural networks can create fairly accurate forecasts of electricity production from wind farms in the range of one hour to one year. The average error of such a forecast with discretization up to a daily hourly breakdown does not exceed 1.049%. The integration of AI technologies into the energy sector offers new opportunities for the integration of renewable energy sources into energy storage systems (ESS). This reduces the unpredictability of generation, achieving an optimal power balance for current consumption and future needs. It is also becoming more important for owners of renewable energy sources to be able to forecast electricity production more accurately, especially as the rules governing electricity markets are becoming stricter and system operators developing the segment are expecting RES producers to plan production for the coming periods. The opposite is also true: the emergence of AI technologies, which allow relatively accurate forecasting of electricity production from RES, could in turn scale back the privileges associated with preferential unconditional acceptance of electricity from RES into the grid based solely on production.

Second direction: Forecasting the demand and price situation on the electricity spot market. Although AI has been used for a while to predict trading dynamics in energy markets worldwide, it is only recently that this method has started to get noticeable attention because of the dynamics of fuel markets. A study of the potential of AI to enhance the precision of short-term price forecasting in the electricity market, conducted at the Higher School of Economics in Russia [

72], found that the average absolute errors of hourly forecasts over time could vary from 2.48% to 3.41%. The liberalization of the electricity market has resulted in the formation of a wholesale electricity energy market. Market participants operate in a competitive environment, facing daily challenges in developing market strategies and planning future financial flows. In this context, forecasting electricity prices has become an essential and routine task for the majority of those engaged. In the context of market uncertainty, forecasting models that are independent of external variables are particularly relevant as any error in the forecast of exogenous parameters may have an adverse impact on the forecast of the desired indicator, namely the market price of electricity. [

72] assesses the potential of utilizing neural networks for short-term forecasting of day-ahead electricity prices, based solely on factors exclusively determined for the forecast period. The results indicate that the proposed set of six factors can effectively construct a monthly Day Ahead Market (DAM) price forecast across all four seasons, with high accuracy. The proposed model exhibits minimal errors in average hourly price prediction per month, enabling the prediction of significant price deviations.

Third direction: Management of configuration and operating modes of small local intelligent networks (micro-grid). The term "micro-grid" is used to describe a type of energy system that is designed to operate independently of a centralized network. This is typically the case in areas where access to the central network is limited or non-existent, such as islands or remote locations. Furthermore, microgrids provide the capability to efficiently link a large number of nearby local energy sources, such as solar panels, within the centralized energy system. This allows users of such a grid to exchange electricity within it to a significant extent, without relying on the central grid. A microgrid is typically constituted of energy production facilities, including those based on renewable energy sources, storage systems, and power main grid networks. These components are integrated to enable the automatic balancing of the mode of operation. This is achieved through the use of controllers, which are installed in the corresponding equipment. This allows the microgrid to respond effectively to fluctuations in energy supply from distributed sources and to accommodate local consumption patterns, including peaks and troughs. In this context, AI technologies can be utilized to achieve high-speed automation of processes and to predict future outcomes. One illustrative example is the REIDS project at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. It comprises eight micro-grids on Semakau Island, which utilize wind, solar and diesel generators, storage systems and a hydrogen-based energy storage system. The French company Metron has joined the international consortium that implements the project (Accenture, Alstom, Engie and Schneider Electric). Metron’s intelligent platform, called "Energy Virtual Assistant", is designed to help optimize the production, storage and consumption of energy in microgrids based on the data collected. Another example is the Isles of Scilly, Great Britain, where company Moixa has developed an intelligent solution in the form of the GridShare platform for this project. The optimal operation plan for the equipment and devices within the microgrid is determined by machine learning based on complex data, including load and production forecasts, weather conditions, user habits and preferences, among other factors.

Fourth direction: Improving the efficiency of the interaction between consumers and the energy system by analyzing the trends in energy demand and supply. This can apply to households as well as commercial and industrial users. Energy regulators are accustomed to assessing energy consumers based on demographic and geographic characteristics, which, at best, is through a commodity consumption profile. Concurrently, users generate a substantial volume of data that is transmitted through the electricity grid. Smart meters can provide a wide variety of information not only about network load, but also about the combination and intensity of use of electrical appliances and equipment, and thus about consumer habits. AI has the capacity to analyze historical data and consumer behavior patterns in order to predict future electricity demand over a specified period. This enables utility companies to optimize power generation and distribution, thereby reducing dependence on peaking power plants and minimizing costs. The use of data analytics allows energy companies to gain insights into customer behavior and preferences. This enables them to develop personalized energy plans or recommendations, which in turn enhances customer satisfaction and may ultimately result in increased energy efficiency through the provision of targeted advice.

Fifth direction: General industrial direction. In this case, AI technologies are used to improve the efficiency of the use of production equipment and energy production facilities, to replace preventive maintenance with predictive maintenance, to monitor the processes of electricity demand and energy resources in general. An example of a solution for predictive maintenance of equipment is the Russian analysis system PRANA, which is based on the Multidimentional Condition Assessment Tehnique (MSET) algorithm (multidimensional condition assessment technique, part of ML) with Hotelling maps, machine learning and AI. By using algorithms, the system compares the actual technical condition of the equipment with a reference model in real time and determines the differences between them, the deviation from the reference model signals an emerging negative trend, the predictive component identifies deviations 2-3 months before they lead to an unplanned shutdown of the equipment. AI technologies can also be used for demand response and distributed energy management platforms. AI, trained to respond to price and production data flows, can take over dispatching functions and effectively manage the energy system of a company or local group of companies, which is effectively a microgrid. Self-balancing of industrial clusters limited in terms of energy consumption is the basis of the active energy complexes development concept in Russia, promoted within the framework of the National Technology Initiative. Given the rapidly increasing complexity of power system structures and the growing number of active objects in the power system (both production and controlled consumption), it may soon become challenging for dispatchers to ensure balance in the power system without the support of AI systems. AI could potentially offer a solution by qualitatively processing the vast amount of information received by dispatchers and, based on this information, suggesting (and potentially implementing in the future) optimal operation modes for the power system.

A synthesizing table on the maturity, scalability, and remaining research challenges for each of the five directions is presented in

Table 2

The aforementioned applications of AI technology in the field of electric power are not merely assisting, but collectively have the potential to significantly reduce our reliance on energy infrastructure. The availability of an electric transmission network and free capacity no longer represents a limitation for the utilization of new areas and the development of already built urban spaces. A new microgrid, which operates in a self-balancing mode, has the potential to develop independently or serve to supplement the existing overloaded networks with new capabilities. In turn, the reduction of unanticipated peaks in consumption through the implementation of AI algorithms has the added benefit for energy companies of reducing the cost of electricity and the costs associated with the construction and maintenance of unused capacity for energy companies. The new format of electricity exchange is very convenient and attractive, but since it depends largely on the development and security of IT technologies, IT-related problems, especially cybersecurity, have now been added to the current problems in energy systems, consisting mainly of purely technical issues, such as reducing fuel costs or losses in the network.

Unlike the classical approach, which defines all necessary information (rules, outcomes) in advance, AI employs algorithms that imply autonomous system development through analysis and processing of newly received information. The primary trends in energy-related AI can be classified into three groups:

Increasing energy efficiency (for example, monitoring actual generated/consumed energy flows). AI algorithms can analyze data from sensors in the building (temperature, occupancy) to optimize heating, ventilation, air conditioning and lighting systems. This leads to significant energy savings, i.e. better energy efficiency, lower utility bills and improved occupant comfort.

Processes of intellectualization and digitalization (development of algorithms, processing of the results of monitoring the state of energy objects, load management, smart grid strategies). Through continuous data analysis, the grid can be closely monitored and potential bottlenecks or outages can be identified in real time. Machine learning can then recommend corrective actions, such as rerouting power flows or adjusting voltage levels, to maintain grid stability and prevent outages.

Predictive modeling (algorithms and strategies for optimizing the operation of energy facilities, forecasting consumed or stored energy, predicting emergency conditions and failures). Periods of excess renewable energy production can be identified through data analysis. Based on this, AI can optimize battery energy storage systems to store this energy and release it during periods of peak demand, thereby maximizing the use of renewable energy. The analysis of data obtained from sensors on industrial equipment allows for the prediction of potential failures. The early detection of such failures enables the implementation of preventative maintenance procedures, which minimize downtime, energy loss, and associated repair costs.

The impact of LLMs is becoming increasingly apparent across various aspects of our society. The energy sector is no exception to this trend. Examples of LLM applications in the energy sector are numerous: automated generation of energy models and optimization of energy management to increase energy efficiency of buildings [

73]; their integration with building energy modeling software with applications in energy efficiency and decarbonization [

74]; their potential in increasing efficiency and sustainability in buildings to reduce global carbon emissions [

75]; Accurate load forecasting in integrated energy systems, particularly beneficial for renewable energy integration and smart grid applications [

76]; Accurate zero-shot load forecasting technique in integrated energy systems, particularly beneficial for renewable energy integration and smart grid applications [

77]; Innovative LLM GAIA, tailored to power dispatch tasks, demonstrating its potential to improve decision making and operational efficiency in power systems [

78]; LLM oriented to renewable and hydrogen energy, developed by controlling physicochemical and process parameters in energy exchange processes for generation and storage fine tuning on a curated renewable energy corpus [

79]; Their potential within the electric energy sector [

80].

As the amount of data increases and more people work and collaborate from all over the world, an integral part of securing energy infrastructure is cybersecurity with its set of processes, best practices and technology systems that help protect against digital attacks. Through the use of AI, anomalies and potential cyberattacks against energy infrastructure can be identified, thereby enhancing security and resilience. [

81] presents a comprehensive framework for securing smart grids in energy systems from cyberattacks by integrating IoT and blockchain technologies within the Digital Twin framework. Through AI, the development of threat detection algorithms can be automated, improving security. After reviewing AI technologies and their applications in the energy sector, the authors provide a comparative overview of some types of AI that could be applied to solve problems in the energy sector in

Table 3.

It can be concluded that AI is transforming the energy sector as a whole, enabling more intelligent decision-making, optimizing resource use, and promoting a more sustainable energy future. As AI technologies continue to evolve, it can be anticipated that even more innovative applications will emerge, which will revolutionize the way energy is produced, distributed, and consumed.

3. Discussion of AI-Driven Renewable Energy Technologies

AI in energy democracy processes combines and applies multiple techniques from various fields of mathematical, engineering and economic sciences. Thus, through modeling, statistical analysis and optimization, process studies and identification of operational parameters, optimal or near-optimal solutions are found to problems related to decision making, adequate management of energy flows and resource efficiency in energy societies, and in the processes of continuous decentralization and digitalization of the energy sector.

The term "energy community" is a relatively new legal concept that the European Union defined in 2019 in the finalized Clean Energy for All Europeans package (CEP) [

82].

At their core, energy communities are legal entities formed by citizens, small businesses, and local authorities. These communities empower their members to produce, manage, and consume their own energy. The scope of an energy community can encompass various aspects of the energy value chain, including production, distribution, supply, consumption, and aggregation. Ultimately, the specific structure and focus of an energy community will depend on factors like location, the participating members, and the types of energy services offered [

83]. According to CEP [

82], energy communities are divided into two types - Renewable Energy Communities and Citizen Energy Communities.

Energy societies with hybrid RES are proving to be a successful, sustainable, and adequate solution during energy transitions. However, it is not always economical to invest in fuel imports or grid expansion. Is a 100% RES scenario possible for countries in Europe by 2050, at what cost and under what conditions? According to [

84,

85], the conditions are as follows: a technological shift in terms of primary energy production, action on carbon emissions (renewables, transport, conventional plants, biofuels) and a change in the economic approach to renewables. From a geopolitical and scientific point of view, the authors recommend the following steps: decommissioning of all nuclear capacities, technical and technological solutions for the use of waste heat, electric transport, eco-fuels, district heating networks for human settlements. The Smart Energy Europe scenario is estimated to be 10-15% more expensive than standard business scenarios for energy investments. Instead of expensive fuel imports and added dependence on them, which come with huge transmission and distribution network investment costs and increased losses in them, this scenario is based on local investments in energy societies with a different concept: a flexible electricity system. Successful implementation of the new concept of energy societies requires changes in transport, technology, regulations, policy, and institutions.

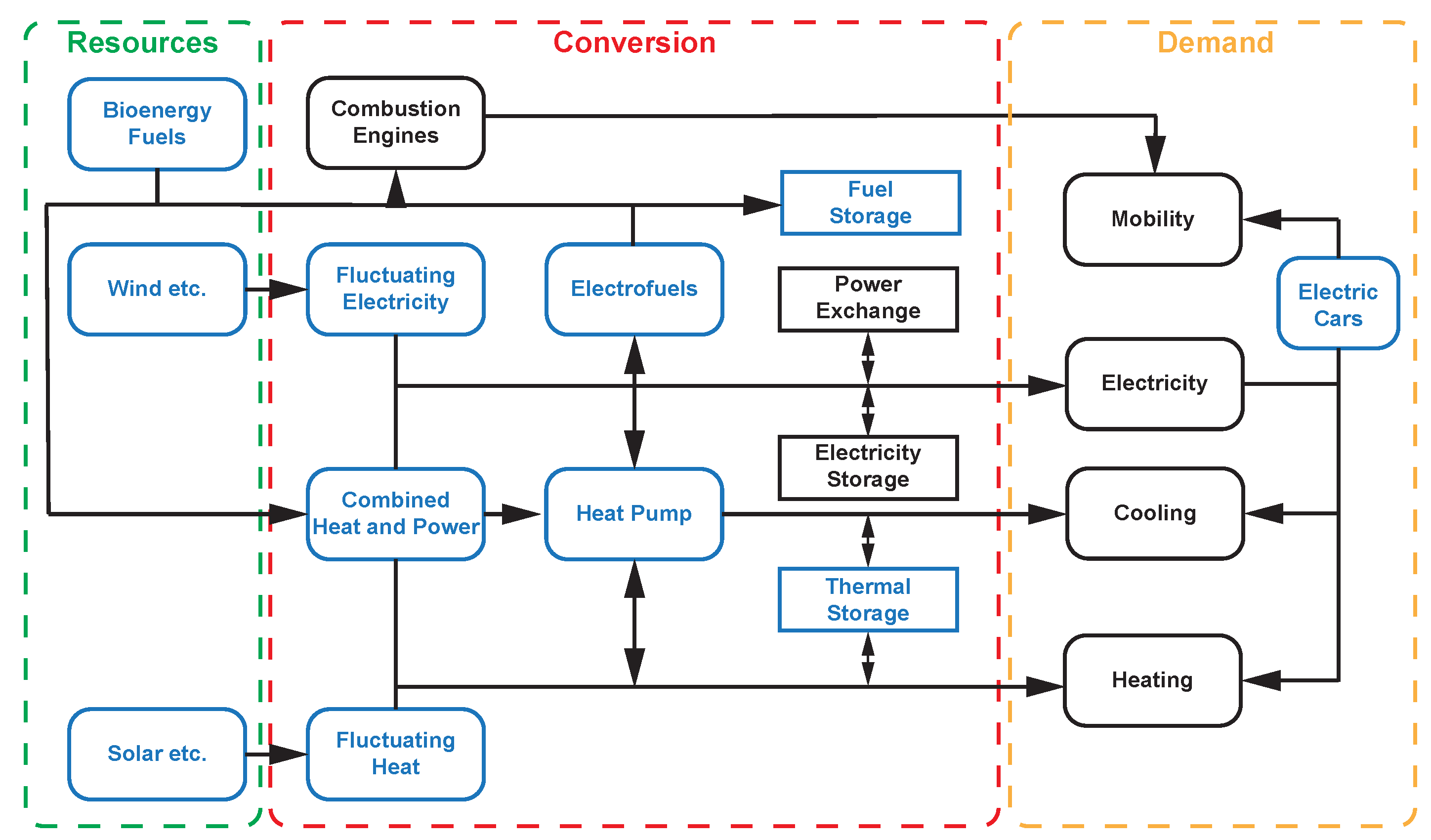

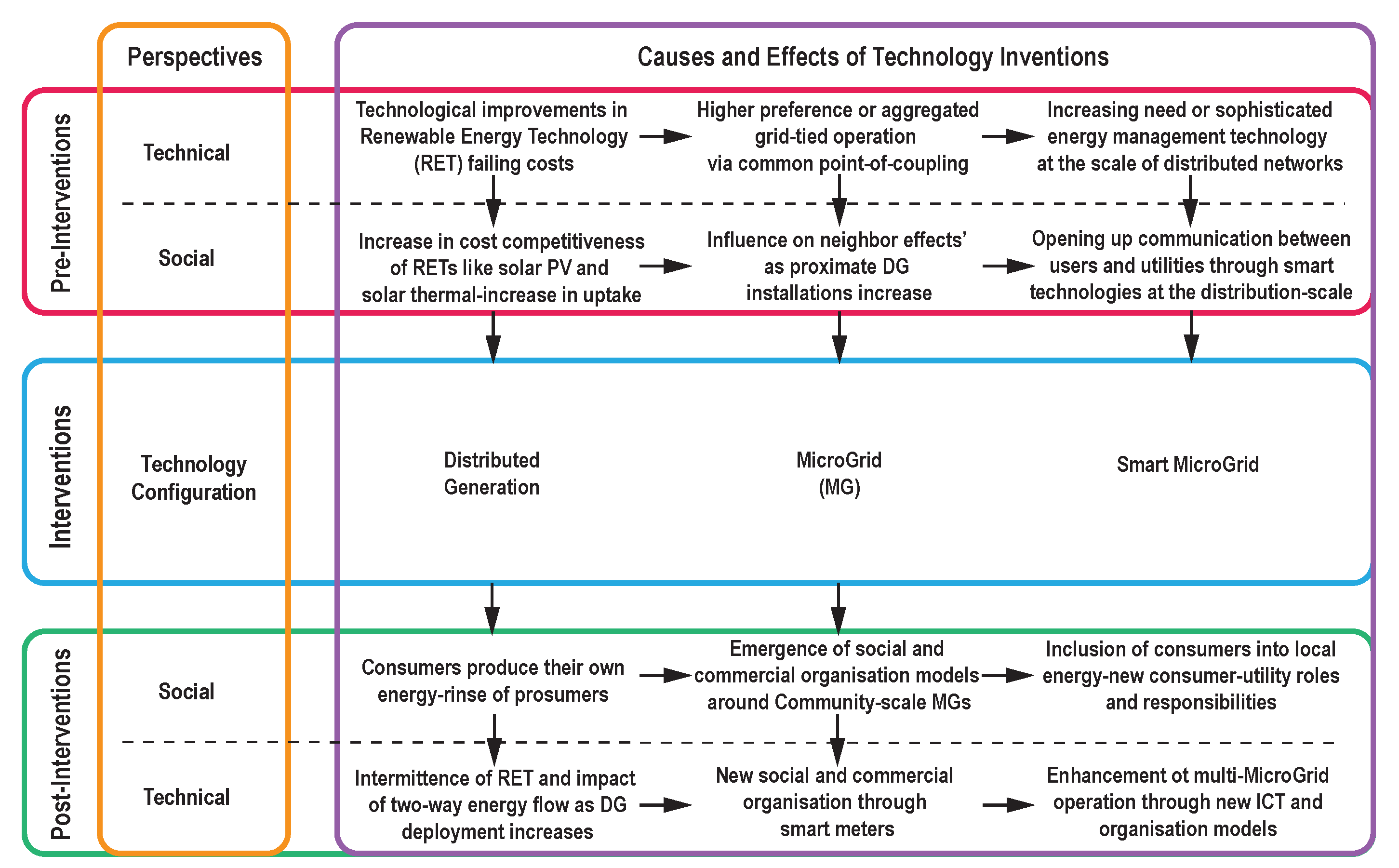

The Smart Energy System concept was developed by the Sustainable Energy Planning Research Group at Aalborg University. A business-as-usual scenario for the European energy system in 2050, called EU28 Ref2050, is compared to an alternative 100% renewable energy scenario for Europe, called Smart Energy Europe. The Energy Plan is used to simulate the energy, transport and heating/cooling sectors on an annual basis for each hour. The data on consumption and generation is stored, processed, and updated continuously to reflect the latest energy exchange figures for all EU countries. The processing, transfer, and analysis of these large datasets is only possible with the help of AI algorithms and techniques that provide integration between sectors and technologies,

Figure 8. The flow diagram is incomplete since it does not represent all of the components in the energy system, but the blue boxes demonstrate the key technological changes required.

What are the advantages of energy democracy and energy societies if there is no well-planned and flexibly managed decentralized generation of renewable energy from hybrid sources? Having been proven to be a good solution and a solution that works [

86]. The efficient generation and distribution of RES according to the participating technologies is achieved through a stakeholder analysis of the integral participation of all actors in the energy mix (decentralized energy planning, DEP). This approach ensures a balance between generation and consumption with minimum installation and maintenance costs. It is applicable to a specific location (city, island, finite number of consumers, etc.) under known climatic, geographical, economic, and other conditions. The additional benefits of DEP include the reduction of uneven distribution, the encouragement of the inclusion of new members of the energy community through affordable energy pricing, and the reduction of carbon emissions. The involvement of AI in the formation and demonstration of DEP is as follows: the creation of a model study of the best performing hybrid RES combinations, the implementation of predictive analysis of generation and consumption load profiles, and the evaluation and selection of appropriate storage technology. As a result, the guaranteed flexibility of micro- and nano-grids and their synergetic integration is achieved.

In [

87], various models and software solutions are employed (Hybrid Optimization of Multiple Energy Resources - HOMER, Network Planner, RETScreen, Long-term Energy Alternative Planning System - LEAP) in order to achieve the optimal energy planning. Three types of sites are considered: enterprise, regional planning, and network planning. Different combinations of hybrid RES are formed, and energy models are prepared in three main steps: model design, predictive analysis procedure, and results. The technological, socio-economic, and energy benefits of decentralized sources in the energy society [

88] are presented in

Figure 9.

The focus here is the use of GAs. For practical application, the final values of some objective, such as actual energy exchange, generation, transmission, distribution, and consumption, are determined. These values can be either maximum (of profit, productivity, or yield) or minimum (of loss, risk, or cost). A typical GA requires a genetic representation of the decision domain and a fitness function to evaluate the decision domain. Once the genetic representation and fitness function have been defined, the GA begins to initialize a population of decisions and then improves it by iteratively applying the mutation, crossover, inversion, and selection operators. The genetic algorithm seeks near-optimal performance by matching short low-order schemes with high-order performance or building blocks.

The fitness function is a special type of objective function used to summarize, as a single value, how close a design solution is to achieving the stated objectives. These functions are used in evolutionary algorithms (EA), such as genetic programming and genetic algorithms, to guide simulations toward optimal design solutions. In such analyses, poor decisions are common problems for the following reason: ignorance of the exchange mechanism between supply members. For this purpose, multi-criteria decision-making is required for appropriate energy distribution and energy digitization, for which we use blockchain.

In [

89], four scenarios are compared using a combination of geographic information systems (GIS) and mathematical modeling. The comparative energy price analysis and investment risk analysis are performed using the HOMER software. The simulations monitor the probability of power loss, the behavior of the system under load dynamics, and the combining of different energy mixes. Through the use of a genetic algorithm, it was found that if the probability of power loss is between 1-5%, it significantly reduces costs. Specifically, capital costs are reduced by 25-30%, operating costs by 15-17%, and the cost of electricity. These are therefore the key parameters to be monitored in off-grid remote areas. In this case, the capacity of the Waste Assimilative Capacity (WAC) has little impact on the model used to determine the electricity price and assess the reliability of the whole system. Furthermore, the extension of the grid to remote locations is identified as an unreliable, inefficient, and cost-ineffective solution due to the presence of high maintenance costs and high-power transmission losses.

The deployment of renewable energy sources for off-grid remote energy communities continues to present challenges, particularly in terms of the high initial capital and operating costs associated with these technologies. In this context, it is essential to optimize the energy dispatch of the system to ensure the most efficient use of resources.

Hybrid systems, which combine different renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and diesel generators, have emerged as a promising solution for these communities. However, it is crucial to consider the trade-offs associated with these systems. For instance, while Diezel-Solar-Wind hybrids offer a cost-effective solution with an electricity price of 0.44

$/kWh, they also result in high CO2 emissions [

89]. For the PV-Wind-Battery combination, the cost of electricity is 0.363

$/kWh with a production of 169 kWh per day, resulting in a reduction of 25t of CO2 per year [

89]. In order to optimize this system, it is necessary to consider the following factors: temperature variation, tilt of the panels, and load variation. In this case, the cost will be higher, at 1.045

$/kWh. However, it is 9-11% lower than the hybrid PV-Wind without Battery. The wind-battery combination has the greatest impact on price and on shaping the energy mix due to the high initial investment and maintenance costs. However, it is indispensable in the evening hours. Achievable and possible optimal low cost of energy is 0.488

$/kWh. If model scenarios are played out with the HOMER software, an average energy cost of 0.595

$/kWh is achieved with 250 kWh of energy generated per day. In this context, the role of AI is to optimize the price of generated electricity. In hybrid systems, the cost is a nonlinear problem whose minimum objective function can be successfully found using numerical, intuitive, and AI methods. Many authors have explored the application of AI in this area. The most commonly used methods include: artificial bee swarm optimization algorithm [

90,

91,

92]; Pareto evolutionary algorithm [

93]; biogeographic-based algorithm [

94]; genetic algorithm [

95,

96]. Despite the diversity of methods, they are rarely combined with techno-economic analysis of capital costs. Cost of storage state charge and COE analyses are even absent from the literature.

For this reason, in [

89] the aforementioned is accomplished. For a 5 kW and 10 kW wind turbine as part of a hybrid power plant. The authors employ a genetic algorithm to assess the LPST and to compare the GA results with those obtained using the HOMER software. The metrics observed include lifetime cost, system reliability (LPST) at different numbers and ratios of panels, turbine height, and battery capacity. The model assumes daily consumption per household (25.55 kWh), weekly consumption (178.85 kWh), and a lead-acid battery bank (for lower cost and sustainable operation at low temperatures).

3.1. Smart Grids and AI Integration

Each energy electricity system (EES) is a single entity comprising both a main centralized generation structure and an additional decentralized structure. This structure is founded upon disparate principles, and its evolution is contingent upon the availability of information and communication technologies. The primary objective of AI in the energy sector is to facilitate the constant adaptation to the dynamic operational requirements of the EES. This naturally gives rise to an increasing interest in digitalization and intellectualization, which offer solutions to the management of the development and operation of integrated energy systems. In fact, AI is creating a new generation of EES - smart grids - which represent a synthesis of energy and information systems. These smart grids possess new functional capabilities for the organization of technical and economic interactions. The aforementioned functionalities are as follows:

Highly operational and adaptable in the conditions of dynamic operating modes and constant technological development.

Priority-oriented price liberalization of the energy market.

Strategic behavior in maintaining the EES reserve margin, pricing mechanisms under different EES operating modes, and energy mix composition.

The fundamental components of a smart energy system (Smart Grid), represent a qualitatively new technological level of interconnectivity between generation, transmission, and conversion systems, as well as consumers. The operation of the Smart Grid is predicated on a unified information space that encompasses data, knowledge, a compendium of mathematical models and methodologies for addressing energy challenges under active-adaptive control. Smart Grids represent a prominent instance of AI implementation within the energy sector. In order to guarantee the stability of the power system and ensure the control of energy flows and reliability, the following fundamental issues must be addressed [

97,

98,

99]:

Advanced forecasting and modeling.

Full automation of energy metering, distribution, and measurement processes, through real-time monitoring and control, allows for an adequate response to be made in case of an imbalance between supplied and consumed electricity, thus avoiding power outages.

Demand response. Real-time optimization of network operation is achieved while maintaining system balance, ensuring energy response to dynamically changing load.

Demand response. Real-time optimization of network operation - in the conditions of maintaining system balance and guaranteeing energy response to dynamically changing load.

Optimization of marketing decisions, output, resources, and inventories.

Safety measures.

Advanced control and monitoring facilitate the identification and localization of faults and failures before they occur, thereby ensuring the safe and reliable operation of the network.

Energy storage.

Forecasting systems with AI elements should help transmission systems cope with greater fluctuations in electricity transmission due to weather and market conditions. AI is therefore useful in the digitization of the entire energy industry by: maintaining and managing energy flows, forecasting generation, consumption, energy losses and energy storage quantities. In [

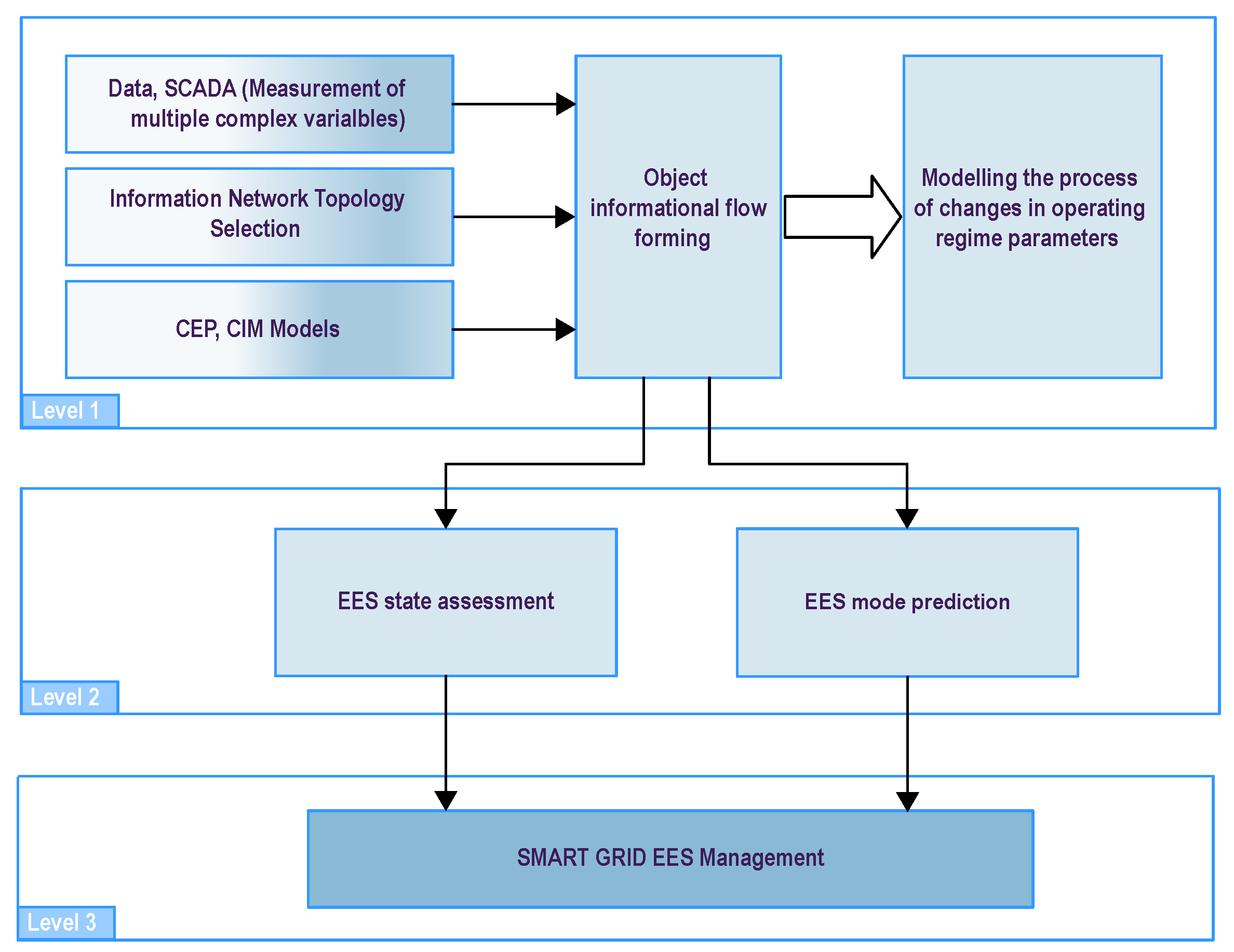

100], an approach for processing information flows in Smart Grid monitoring and control modes is proposed. Decision making is supported by an AI infrastructure that analyzes the situation and models the mode to manage the operating modes of the power system with guaranteed high reliability, efficiency, integration of RES, control and management of generated and stored energy flows. The proposed AI solves three tasks: 1) collection, transmission and processing of data streams; 2) development of software complexes that exchange and use common information resources; 3) development of intelligent modules to support decision making for operation mode management. In order to solve these tasks permanently over time, the AI infrastructure has 8 systems: a data acquisition and transmission system; a dispatch and process control communication system; a supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) system; an object-oriented data model creation system; a data visualization system; an electric power generation and transmission management system; an electric power capacity market management system; an electric power transmission and distribution management system The nature of and interrelation between the different systems are shown in

Figure 10. Complex Event Processing (CEP) models are used for real-time event processing and Common Information Model (CIM) models are used for data exchange in power system modeling.

Two main aspects emerge in the integration of AI in Smart Grids: 1) data processing, knowledge extraction from the data, intellectual analysis of the data and ML; 2) semantic representation of the knowledge extracted from the data through semantic technologies and expert systems. In this way, we achieve the solution of the main tasks of AI in Smart Grids: predictive maintenance, energy forecasting, demand response, grid optimization and cybersecurity.

In smart grids, neural networks are used to solve the following tasks: consumption forecasting (25%), dynamic stability assessment (14%), control and identification (9%), fault and outage diagnosis (18%), planning (7%), reliability assessment (17%), outage warning (10%). Other emerging AI technology trends in the smart grid are: edge computing, advanced metering (smart meters, two-way communication, data management, demand response, time-of-use pricing), distributed automation (sensors, communication, 5G wireless networks, control systems, and cybersecurity).

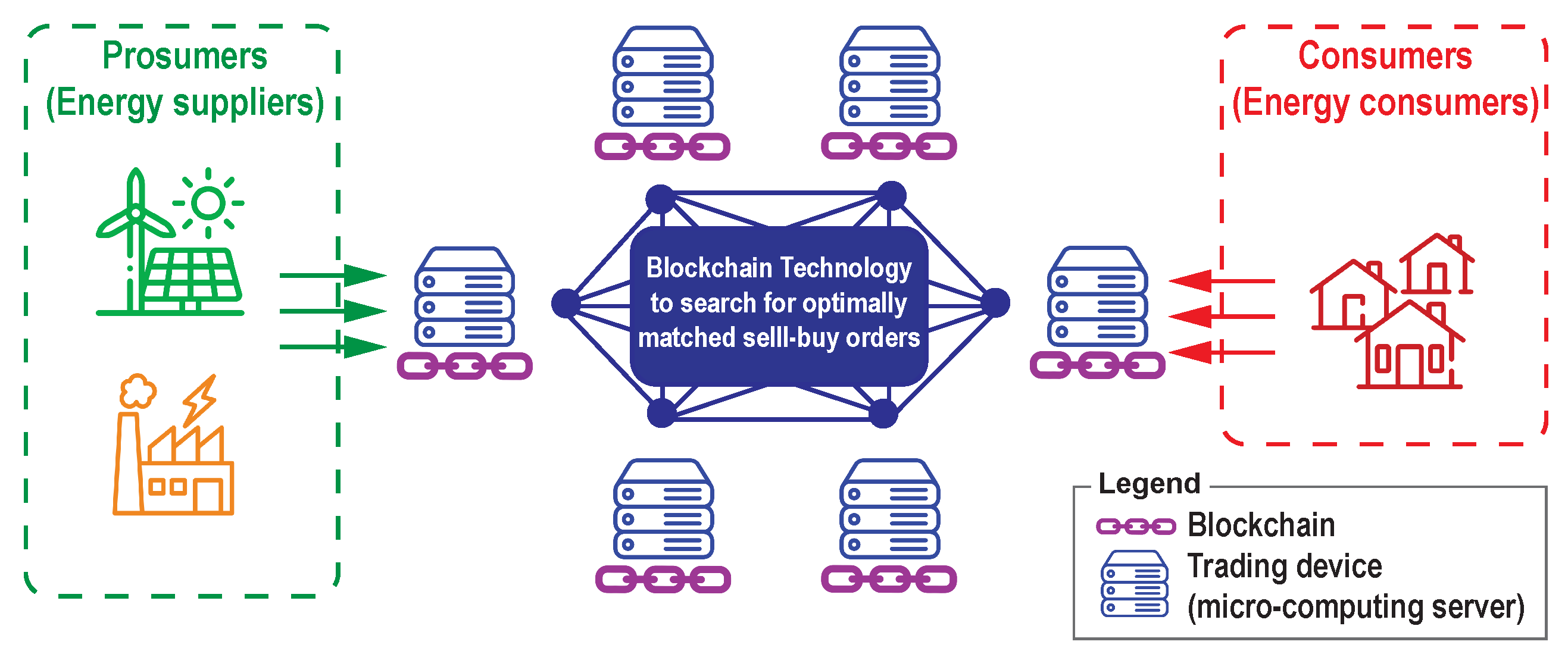

The blockchain technology in the context of energy societies and energy democracy is now a pressing necessity, as illustrated in

Figure 11.

A similar perspective is presented in [

101], which highlights the key points in the "National AI Development Strategy 2030" relevant to Russia’s energy sector. At the outset of the digital transformation of the energy sector at various stages of production, transmission, distribution and consumption of electricity in order to reduce losses (financial and energy), the following modern information and intelligent technologies are applicable:

Industrial Internet (IoT in industry) for telemeasurements of various parameters of the EES.

Big Data analytics technologies enable the prediction of the behavior of energy sites within the EES.

Building Information Model (BIM) technology for the collection of data regarding energy infrastructure, including substations, power plants, and sites engaged in energy extraction and processing.

Technology for the remote sensing of natural and technogenic factors on Earth.

Satellite navigation systems for discrete transport control.

Business Entity Ontological Model (BEOM) - Ontological models to create a single comprehensive dynamically evolving model related to the structuring and description of task types, organizational structures, territories and objects. This simplifies and unifies the data exchange, allowing the accumulation of knowledge and experience pertaining to specific situations and/or sites.

In all structures of the energy sector, including energy societies, the so-called "digital economy" plays an important role, operating with energy and econometric indicators. In this area, big data, neural networks and AI, quantum technology systems, the industrial Internet, new manufacturing technologies, sensing and virtual and augmented reality technologies, contactless technologies are used. Authors relied on expert systems in the beginning, which describe an algorithm to make a decision under certain conditions, today we rely on machine learning. ML methods allow information systems to autonomously form rules and identify solutions through dependency analysis using output datasets. As computing power increases and AI advances, it becomes possible to integrate Big Data with Deep Learning methods, which serve as the foundation of neural networks. ML represents a subset of AI methods that do not directly solve the problem but conduct a learning process by solving multiple similar problems. ML methods are founded upon a number of mathematical and statistical tools, including numerical methods, optimization methods, probability theory, graph theory, and techniques for dealing with numerical data. One of the key challenges of ML is the development of techniques that enable the reduction of the data set required for neural network training. While ML methods yield results, they do not explain how these results were obtained. CC is capable of autonomous decision-making, audio and video recognition, machine vision, and word processing. While ML methods yield results, they do not explain how these results were obtained. This is achieved using Explainable AI (XAI), which represents a set of processes and methods that facilitate the understanding of the rationale behind the output or conclusions reached by machine learning algorithms. XAI is used to describe AI models, their expected impact and potential capabilities. Furthermore, XAI helps to determine the accuracy, reliability and transparency of AI-driven decision-making processes.

Edge computing (EC) has emerged as the dominant technology trend in the IoT market. The concept of edge analytics is based on the collection, processing and analysis of data from network peripherals (sensors, network switches, actuators and controllers) that are closely connected to the source of information. Due to advancements in cloud technologies, software, communication, and data storage systems, edge computing enables data processing to occur at the periphery of the network, where the physical integration of IoT devices with the Internet is established. This enables the real-time analysis of pivotal data in real time and "on the spot",

Figure 12.

Edge Computing is not simply data processing, rather, it is a technology that enables seamless integration of peripherals and cloud computing in a two-way data exchange. [

102] provides a detailed explanation of the precise manner in which edge computing technology is used in the Russian power sector to create DTs.

Ontology engineering in energy represents a new field of engineering science that enables the integration of mathematical models to create digital counterparts of energy structures and objects in order to investigate, control and predict their behavior [

103,

104]. Digital energy is increasingly replacing standard mathematical and model-based research. DTs are considered to be in the top ten strategic technology directions for 2019.

The basis of the hierarchical research technology in the energy sector is the development of a software-information interface between the solved problems in the horizontal (between individual energy systems) and vertical (between generating sources and external conditions) directions. The development and implementation of such type of interfaces ensure: the preservation of the confidentiality of the underlying data sets supporting the specific task; accelerated information exchange and provision of uniqueness of the exchanged data; certain unification of the used information models; priority sequence of the decisions. The aforementioned requirements are covered by DTs, digital shadows, digital patterns, and digital models.

There are three types of DTs:

Digital Twin Prototype - a virtual analogue of a real existing element. It contains information that describes the item in all its development stages (construction, technological processes in operation, and even requirements in the item’s utilization).

Digital Twin Instance - a virtual analogue containing information on the description of the element/equipment, including material data and complex information from the condition monitoring system.

Digital Twin Aggregate - combines prototype and object, collecting all the equipment information of the power system.

For companies that service/build/maintain electrical grids, the most suitable is Digital Twin Instance, based on mathematical grid modeling. In this case, the Digital Twin Instance will contain information about the parameters of the equipment used (cables, transformers, start-up protection equipment), geographical coordinates, data from measuring devices, etc. All this information is used for calculations during the commissioning of new users, testing different modes of operation of the network, short circuit currents, consistency of protective apparatuses, etc. In this way, the digital twin of the power grid, together with the data contained in it, is integrated with other AI systems of the power company (SCADA, asset management systems, etc.). The digital twin synchronizes all data to match the current state of the grid.

A digital shadow is defined as a system of relationships and dependencies that describe a real energy object in actual operating conditions and contain additional data. This data is used to predict the behavior of the real energy object when the combination of collected and available data does not allow modelling. Experiments conducted on real energy objects are often prohibitively expensive or dangerous. In such cases, the use of virtual simulations and training represents an excellent alternative. A variety of AI mechanisms automate the aforementioned processes, interpret them in accordance with the hierarchical technology of the study or modeling, and formulate an assessment of the situation or site by proposing a solution for subsequent action.

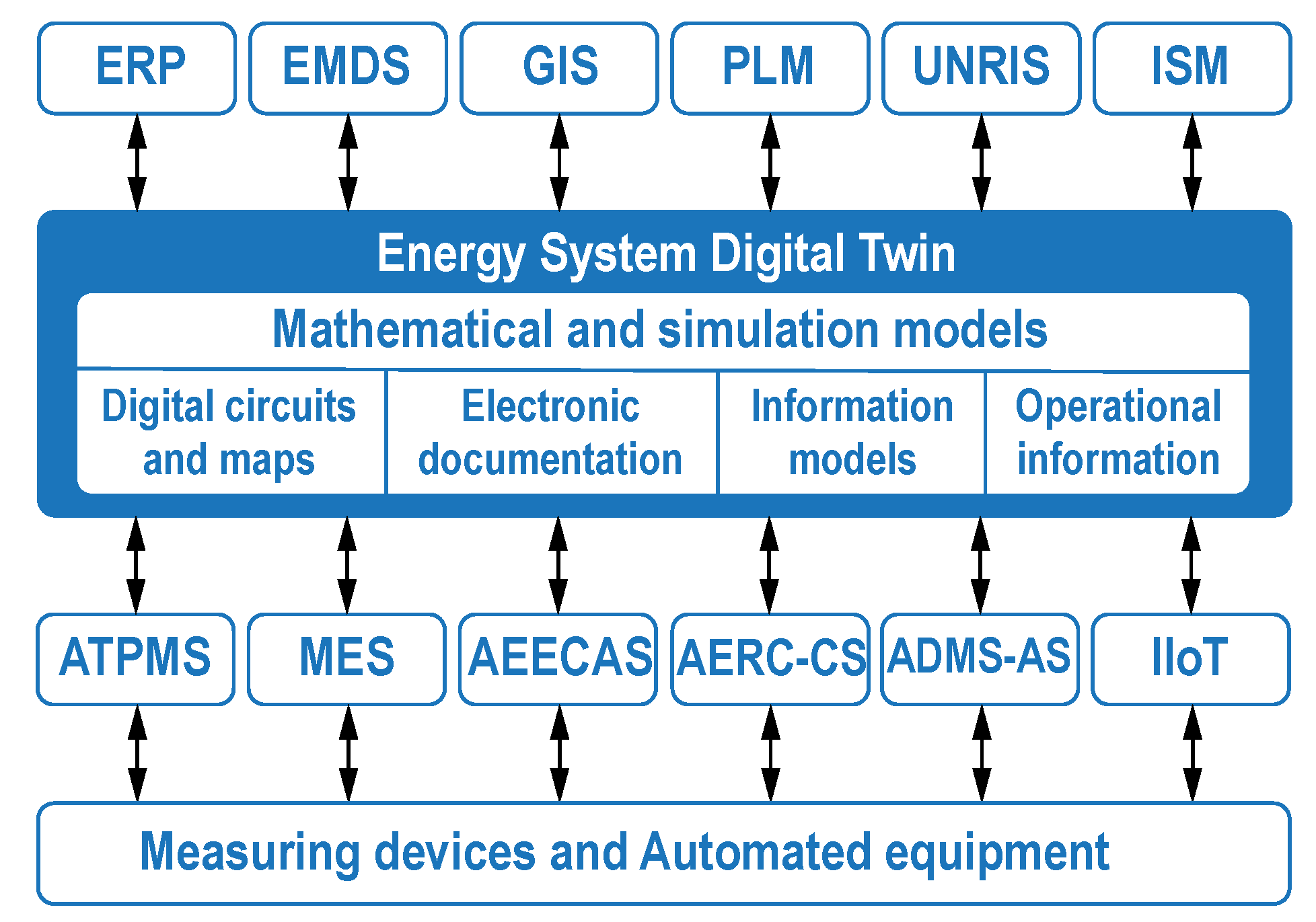

DTs are real copies of all components in the life cycle of a site, created with real physical data, virtual data and interaction data. DTs integrate information about the parameters of the site’s functioning, its exact mathematical model based on real data that is accessible online. Smart DTs are an integration technology that includes: a core of DTs (mathematical, simulation and information models); a system for collecting data from the physical object; storage of the data sets; a service system for communication between all components (IoT).

A new but integral part of the digital twin trend is cognitive technologies in energy. They enable the collection, storage, and processing of extremely large databases (big data). However, implementing these technologies in the energy sector is challenging because much of the output data is not from digital processes, but from analog and material structures. A key factor is the availability of a proprietary data collection and storage infrastructure for training the cognitive models. It is important to note that a key component of the digital dual is the complex set of mathematical and economic numerical simulation, and neural models that describe every aspect of the energy site’s behavior. Of course, mechanisms are provided for model calibration, including ML. With a high degree of sophistication, the numerical representations are needed to explore possible scenarios for the evolution of the power system and to make strategic decisions about it. An example architecture of a digital power system twin is shown in

Figure 13.

Where:

ERP: Enterprise Resource Planning. Automated system of enterprise management. It is a system of software, technical, information, linguistic, organizational and technical means and personnel actions designed to manage the activities of the enterprise. ERP - a strategy for integration of production and labor management, financial management, asset management.

EDMS: Electronic Document Management System.

GIS: Geographic Information System. System for collecting, storing, analyzing, and graphically visualizing objects and related data.

PLM: Product Lifecycle Management. Automated design system combined with PLM.

UNRIS: Unified Normative and Reference Information System. Unified normative and reference information system for the purpose of providing automated creation, updating, and use of basic government information resources and/or interagency information assurance.

ISM: Information Security Measures.

ATPMS: Automated Technological Process Management System.

MES: Manufacturing Execution System. Automated system for control and monitoring of technological processes for power generation (including collection, processing, transmission, visualization of information about the equipment, the course of technological processes, allowing operational intervention and influence on the processes for optimization, efficiency and safety).

AEECAS: Automated Electric Energy Control and Accounting System.

AERC-CS: Automated Energy Resource Consumption Control System.

ADMS-AS: Automated Dispatching and Monitoring System for All. Automated dispatching and monitoring system for all subsystems (power supply, fire and alarm systems, ventilation, air conditioning, video surveillance and access control, etc.).

DTs are a solution for energy-intensive sites: industrial, transportation infrastructure, e.g. airports [

105]. For such energy sites, the European Union has launched the Stargate IES initiative. Stargate IES is developing a digital twin to demonstrate the potential of buildings in the real world, with the goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2030. IES is developing a digital replica of the 40 most energy-intensive buildings at Brussels Airport and then modeling scenarios such as installing photovoltaic solar panels, electric car chargers and electrifying heating to find the most efficient ways to achieve zero carbon by 2030 for the airport. This flagship project is part of the EU-funded Stargate initiative, which received a €24.8 million grant from the European Green Deal to develop concrete solutions to improve the sustainability of airports and aviation. Brussels Airport plays a leading role in the Stargate project, which is being implemented with a consortium of 21 partners, including Athens, Budapest and Toulouse airports, which are also working with IES to develop DTs to support their decarbonization goals. Through rigorous modeling phases, IES simulated Brussels Airport’s plan to reduce emissions in its buildings through various energy-saving measures (replacing gas boilers with heat pumps, installing on-site photovoltaic systems, etc.). These measures result in a CO2 reduction of up to 63% compared to the 2019 baseline. Modelling shows that the decarbonization plan is a viable path and, to ensure its sustainability, will be pursued with the implementation of zero-carbon energy solutions over the next six years. Investments will be made in additional renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, to reduce reliance on external energy suppliers, meaning the airport will be carbon neutral by the end of 2030.

What are the circumstances under which it is appropriate to construct DTs in smart cities? In urban environments with intensive traffic, the digital twin represents a solution that can ensure the safety and control of the environment. The creation of a digital twin of a city’s road network allows for the achievement of several benefits. Firstly, traffic patterns and driver behavior can be mimicked in real-world conditions, which enables the identification of causes of delays and traffic. Secondly, solutions for infrastructure changes, new traffic management strategies or alternative routes can be tested to assess their impact before implementation. Thirdly, repair and other costs would be significantly reduced, and traffic data would be collected and analyzed. DTs have one major advantage: their scalability. The approach used to create a digital twin is scalable to cities of different sizes and structural complexity. By creating DTs of urban infrastructure, digital replicas of a city’s key infrastructure networks (e.g., power grids, water systems, transportation) can be used as the basis for simulating the impacts of weather events such as floods, storms, and other extreme weather events. An example of such a project is the Climate Resilience Demonstrator (CReDo), a digital twin project for climate change adaptation that provides a practical example of how linked data can improve climate adaptation and energy resilience in a system of systems. The CReDo hub is dedicated to the examination of the impact of flooding on energy, water, and telecommunications networks. It demonstrates how those who own and operate them can use secure, resilient and cross-border information sharing to mitigate the effects of flooding on network operations and service delivery. Climate change is a systemic challenge that requires a systemic solution. CReDo illustrates the advantages of this integrated strategy and demonstrates how enhanced data and coordination lead to more effective solutions for service providers. The collaborative use of DTs in a connected environment is a crucial strategy for addressing climate change. CReDo provides an important template to build on. There is huge potential to adapt it to other challenges, such as climate mitigation and net zero. The end goal is building an ecosystem of connected DTs. The objective of CReDo is to serve as a connected digital twin of critical infrastructure, supporting the cross-sector infrastructure network in adapting to climate change and enhancing climate resilience. CReDo is the result of a unique collaboration between academia, utilities, and government. In the first phase of CReDo, Anglian Water, BT and UK Power Networks work together to use their asset and operational data, as well as weather data from the Met Office, on a secure, shared basis to improve infrastructure resilience. These datasets are being securely shared to create a digital twin of the energy, water and telecoms infrastructure system. This enables real-time capital and operational planning and decision making, reducing the cost and disruption of extreme weather events.

CReDo was delivered through a collaboration of research centres (Universities of Cambridge, Edinburgh, Newcastle, and Warwick along with the Science and Technology Facilities Council, and the Joint Centre of Excellence in Environmental Intelligence) and industry, funded by BEIS, the Connected Places Catapult and the University of Cambridge.

Another example of DTs is smart buildings. They are useful solutions for improved management of energy flows in buildings. By creating 3D models of buildings, better space management, optimization, and overall management of energy flows can be achieved. Unfortunately, local governments still consider this technology and AI intervention to be unacceptable and risky. For DTs in the public sector, it is important to take account of the following considerations:

It is necessary to analyze the costs and benefits of such an AI deployment. It is critical to weigh the cost of implementing a digital twin platform against the potential benefits in terms of efficiency and cost saving.

Data security is paramount, and security measures are needed against cyberattacks and data theft.

The nature and sensitivity of the data to be stored (building drawings, security camera footage, population information, microclimate parameters, etc.) must be clear from the outset.

How will access to the platform and the data stored on it be controlled? Who will have access and what level of access (read-only, edit-only, etc.)?

How will data be encrypted: at rest and in transit? Are industry-standard encryption protocols being used?

What is the platform vendor’s data backup and recovery plan? How quickly can data be recovered in the event of a disaster or cyberattack?

Does the platform comply with relevant data security regulations (e.g., HIPAA, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR))?