Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort and Workflow

2.2. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling

2.3. Variant Interpretation

2.4. Outcome and Clinical Data Assessment

3. Results

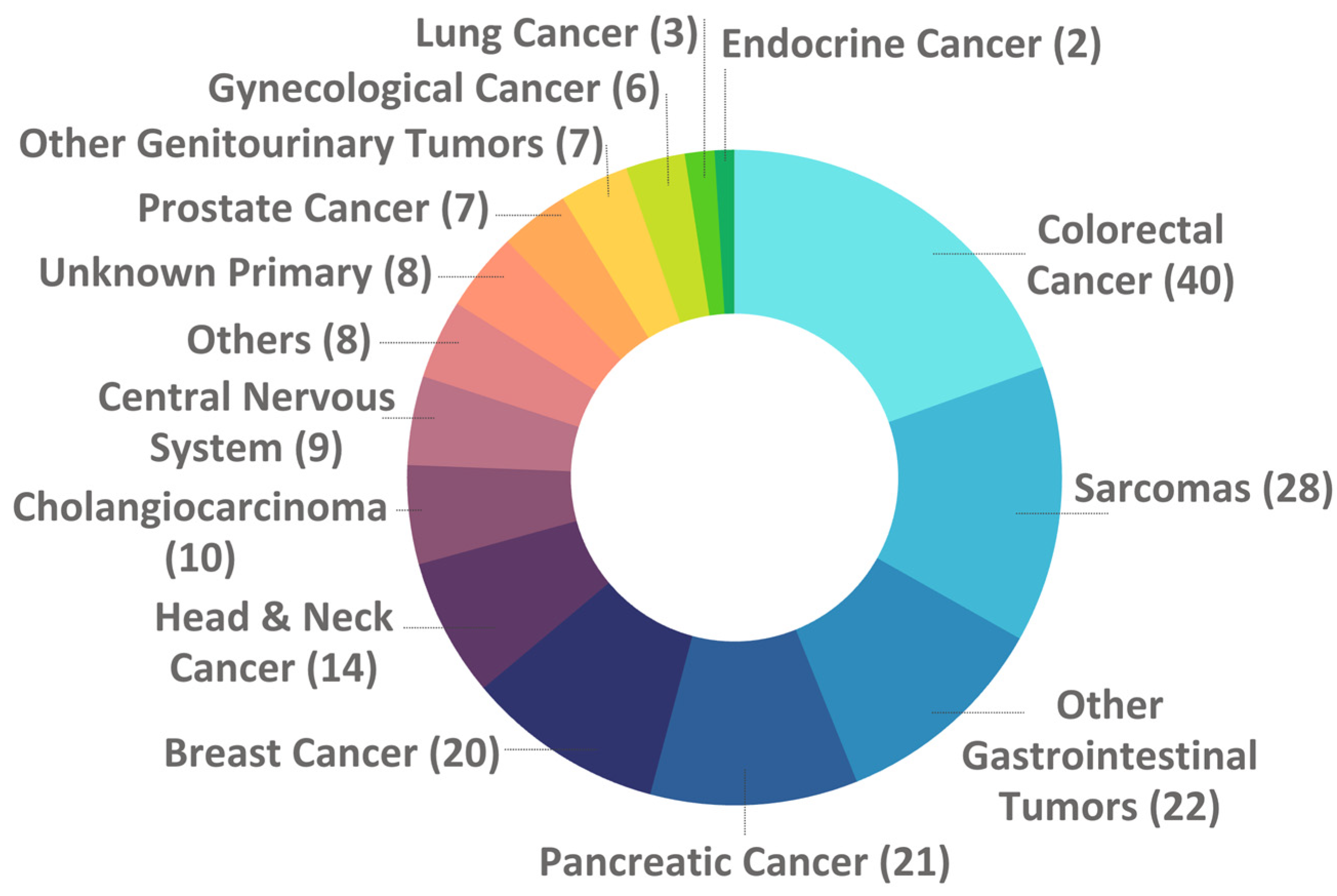

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients

3.2. Molecular Testing

3.3. Outcomes

3.4. Molecular Tumor Boards

3.5. Quality of Life Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASCO | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| bTMB | Blood tumor mutational burden |

| cfDNA | Circulating cell-free DNA |

| CGP | Comprehensive genomic profiling |

| CNA | Copy Number Alterations |

| ESCAT | ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets |

| ESMO | European Society for Medical Oncology |

| FFPE | Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded |

| FRONTAL | Foundation Medicine Real wOrld evideNce in PorTugAL |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| HRD | Homologous Recombination Deficiency |

| Indels | Insertion and deletion alterations |

| LOH | Loss of Heterozygosity |

| MSI | Microsatellite Instability |

| MTB | Molecular Tumor Boards |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| RWE | Real-World Evidence |

| TMB | Tumor Mutational Burden |

References

- Hyman, D.M.; Taylor, B.S.; Baselga, J. Implementing Genome-Driven Oncology. Cell 2017, 168, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, M.F.; Mardis, E.R. The emerging clinical relevance of genomics in cancer medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbury, C.A.; Creeden, J.; Yip, W.K.; Smith, D.L.; Pattani, V.; Maxwell, K.; Sawchyn, B.; Gjoerup, O.; Meng, W.; Skoletsky, J.; et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne®CDx, a comprehensive genomic profiling assay for solid tumors. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0264138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodhouse, R.; Li, M.; Hughes, J.; Delfosse, D.; Skoletsky, J.; Ma, P.; Meng, W.; Dewal, N.; Milbury, C.; Clark, T.; et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne Liquid CDx, a novel 324-Gene cfDNA-based comprehensive genomic profiling assay for cancers of solid tumor origin. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0237802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Nahas, M.K.; Wang, K.; Rampal, R.K.; Intlekofer, A.M.; Patel, J.; Krivstov, A.; Frampton, G.M.; Young, L.E.; et al. Integrated genomic DNA/RNA profiling of hematologic malignancies in the clinical setting. Blood 2016, 127, 3004–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, M.F.; Westphalen, C.B.; Stenzinger, A.; Barlesi, F.; Bayle, A.; Bièche, I.; Bonastre, J.; Castro, E.; Dienstmann, R.; Krämer, A.; et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with advanced cancer in 2024: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tourneau, C.; Delord, J.P.; Gonçalves, A.; Gavoille, C.; Dubot, C.; Isambert, N.; Campone, M.; Trédan, O.; Massiani, M.A.; Mauborgne, C.; et al. Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massard, C.; Michiels, S.; Ferté, C.; Le Deley, M.C.; Lacroix, L.; Hollebecque, A.; Verlingue, L.; Ileana, E.; Rosellini, S.; Ammari, S.; et al. High-Throughput Genomics and Clinical Outcome in Hard-to-Treat Advanced Cancers: Results of the MOSCATO 01 Trial. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trédan, O.; Wang, Q.; Pissaloux, D.; Cassier, P.; de la Fouchardière, A.; Fayette, J.; Desseigne, F.; Ray-Coquard, I.; de la Fouchardière, C.; Frappaz, D.; et al. Molecular screening program to select molecular-based recommended therapies for metastatic cancer patients: analysis from the ProfiLER trial. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, K.T.; Gray, R.J.; Chen, A.P.; Li, S.; McShane, L.M.; Patton, D.; Hamilton, S.R.; Williams, P.M.; Iafrate, A.J.; Sklar, J.; et al. Molecular Landscape and Actionable Alterations in a Genomically Guided Cancer Clinical Trial: National Cancer Institute Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3883–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangat, P.K.; Halabi, S.; Bruinooge, S.S.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Alva, A.; Janeway, K.A.; Stella, P.J.; Voest, E.; Yost, K.J.; Perlmutter, J.; et al. Rationale and Design of the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry Study. JCO Precision Oncology 2018, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kringelbach, T.; Højgaard, M.; Rohrberg, K.; Spanggaard, I.; Laursen, B.E.; Ladekarl, M.; Haslund, C.A.; Harsløf, L.; Belcaid, L.; Gehl, J.; et al. ProTarget: a Danish Nationwide Clinical Trial on Targeted Cancer Treatment based on genomic profiling - a national, phase 2, prospective, multi-drug, non-randomized, open-label basket trial. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velden, D.L.; Hoes, L.R.; van der Wijngaart, H.; van Berge Henegouwen, J.M.; van Werkhoven, E.; Roepman, P.; Schilsky, R.L.; de Leng, W.W.J.; Huitema, A.D.R.; Nuijen, B.; et al. The Drug Rediscovery protocol facilitates the expanded use of existing anticancer drugs. Nature 2019, 574, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerdes, I.; Filis, P.; Fountoukidis, G.; El-Naggar, A.I.; Kalofonou, F.; D’Alessio, A.; Pouptsis, A.; Foukakis, T.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Ahlgren, J.; et al. Comprehensive genome profiling for treatment decisions in patients with metastatic tumors: real-world evidence meta-analysis and registry data implementation. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2025, 117, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, S.N.; Peneva, D.; Cuyun Carter, G.; Palomares, M.R.; Thakkar, S.; Hall, D.W.; Dalglish, H.; Campos, C.; Yermilov, I. Comprehensive Review on the Clinical Impact of Next-Generation Sequencing Tests for the Management of Advanced Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 2023, 7, e2200715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, A.M.; Riess, J.W.; McLaughlin-Drubin, M.; Huang, R.S.P.; Hjulstrom, M.; Creeden, J.; Alexander, B.M.; Erlich, R.L. Insights of Clinical Significance From 109 695 Solid Tumor Tissue-Based Comprehensive Genomic Profiles. Oncologist 2024, 29, e224–e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Chakravarty, D.; Dienstmann, R.; Jezdic, S.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Lopez-Bigas, N.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Bedard, P.L.; Tortora, G.; Douillard, J.Y.; et al. A framework to rank genomic alterations as targets for cancer precision medicine: the ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets (ESCAT). Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremke, N.; Rodepeter, F.R.; Teply-Szymanski, J.; Griewing, S.; Boekhoff, J.; Stroh, A.; Tarawneh, T.S.; Riera-Knorrenschild, J.; Balser, C.; Hattesohl, A.; et al. NGS-Guided Precision Oncology in Breast Cancer and Gynecological Tumors-A Retrospective Molecular Tumor Board Analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruzas, S.; Kuemmel, S.; Harrach, H.; Breit, E.; Ataseven, B.; Traut, A.; Rüland, A.; Kostara, A.; Chiari, O.; Dittmer-Grabowski, C.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing-Directed Therapy in Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer in Routine Clinical Practice. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, D.P.; Rini, B.I.; Khorana, A.A.; Dreicer, R.; Abraham, J.; Procop, G.W.; Saunthararajah, Y.; Pennell, N.A.; Stevenson, J.P.; Pelley, R.; et al. Prospective Clinical Study of Precision Oncology in Solid Tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphalen, C.B.; Bokemeyer, C.; Büttner, R.; Fröhling, S.; Gaidzik, V.I.; Glimm, H.; Hacker, U.T.; Heinemann, V.; Illert, A.L.; Keilholz, U.; et al. Conceptual framework for precision cancer medicine in Germany: Consensus statement of the Deutsche Krebshilfe working group 'Molecular Diagnostics and Therapy'. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 135, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkala, M. Mutational landscape of cancer-driver genes across human cancers. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; El Hage, M.; Linnebacher, M. Mutation patterns in colorectal cancer and their relationship with prognosis. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damerell, V.; Pepper, M.S.; Prince, S. Molecular mechanisms underpinning sarcomas and implications for current and future therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, S.; Liu, B.; Pant, V.; Celii, F.; Chau, G.; Elizondo-Fraire, A.C.; Yang, P.; You, M.J.; El-Naggar, A.K.; et al. Somatic Trp53 mutations differentially drive breast cancer and evolution of metastases. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012, 490, 61–70. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Etemadmoghadam, D.; Temple, J.; Lynch, A.G.; Riad, M.; Sharma, R.; Stewart, C.; Fereday, S.; Caldas, C.; Defazio, A.; et al. Driver mutations in TP53 are ubiquitous in high grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. J. Pathol. 2010, 221, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandoth, C.; Schultz, N.; Cherniack, A.D.; Akbani, R.; Liu, Y.; Shen, H.; Robertson, A.G.; Pashtan, I.; Shen, R.; Benz, C.C.; et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013, 497, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuno, I.; Takayanagi, D.; Asami, Y.; Murakami, N.; Matsuda, M.; Shimada, Y.; Hirose, S.; Kato, M.K.; Komatsu, M.; Hamamoto, R.; et al. TP53 mutants and non-HPV16/18 genotypes are poor prognostic factors for concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasco, M.; Crook, T. The p53 network in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2003, 39, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofner, H.; Kramer, G.; Shariat, S.F.; Hassler, M.R. TP53 Deficiency in the Natural History of Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLendon, R.; Friedman, A.; Bigner, D.; Van Meir, E.G.; Brat, D.J.; M. Mastrogianakis, G.; Olson, J.J.; Mikkelsen, T.; Lehman, N.; Aldape, K.; et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 2008, 455, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.S.; Wang, K.; Gay, L.; Otto, G.A.; White, E.; Iwanik, K.; Palmer, G.; Yelensky, R.; Lipson, D.M.; Chmielecki, J.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Carcinoma of Unknown Primary Site: New Routes to Targeted Therapies. JAMA Oncol 2015, 1, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, A.J.; Lamlum, H.; Ilyas, M.; Wheeler, J.; Straub, J.; Papadopoulou, A.; Bicknell, D.; Bodmer, W.F.; Tomlinson, I.P. APC mutations in sporadic colorectal tumors: A mutational "hotspot" and interdependence of the "two hits". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2000, 97, 3352–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saoudi Gonzalez, N.; Patelli, G.; Crisafulli, G. Clinical Actionability of Genes in Gastrointestinal Tumors. Genes 2025, 16, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utilização de testes genómicos no apoio à decisão terapêutica em Oncologia. Ordem dos Médicos versão revista 2023.

- Volders, P.-J.; Aftimos, P.; Dedeurwaerdere, F.; Martens, G.; Canon, J.-L.; Beniuga, G.; Froyen, G.; Van Huysse, J.; De Pauw, R.; Prenen, H.; et al. A nationwide comprehensive genomic profiling and molecular tumor board platform for patients with advanced cancer. npj Precision Oncology 2025, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogas, M.; Antas, J.; Magalhães, C.; Revige, M.; Guerra, L.; Ribeiro, C.; Eça, R.C.; Nunes, F.; Lopes, A.; Costa, L.; et al. Assessment of competencies of clinical research professionals and proposals to improve clinical research in Portugal. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, Volume 16-2025. [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, J.; Mukai, K.; Kondo, T.; Yoshioka, M.; Kage, H.; Oda, K.; Kudo, R.; Ikeda, S.; Ebi, H.; Muro, K.; et al. First-Line Genomic Profiling in Previously Untreated Advanced Solid Tumors for Identification of Targeted Therapy Opportunities. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6, e2323336–e2323336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Health System Category | # of pts |

| University Hospital(a) | 128 |

| General Hospital(b) | 32 |

| Private Hospital(c) | 27 |

| Oncology Institute(d) | 18 |

| Total | 205 |

| N | Percentage (%) | |

| Total | 205 | 100 |

| Biological Sex | ||

| Male | 110 | 53.7 |

| Female | 95 | 46.3 |

| Race | ||

| White | 168 | 82.0 |

| Black or African Descent | 4 | 2.0 |

| Asian | 1 | 0.5 |

| Unknown/Not reported | 32 | 15.6 |

| Patient Status | ||

| Deceased | 161 | 78.5 |

| Alive | 44 | 21.5 |

| Family History of Cancer | ||

| Yes | 87 | 42.4 |

| No | 77 | 37.6 |

| Unknown | 41 | 20.0 |

| Tobacco Use | ||

| Never | 120 | 58.5 |

| Previous or Current | 66 | 32.2 |

| Unknown | 19 | 9.3 |

| Alcohol Consumption | ||

| Never | 174 | 84.9 |

| Previous or Current | 13 | 6.3 |

| Unknown | 18 | 8.8 |

| Tumor stage at diagnosis | % | |

| I - III | 81 | 39.5 |

| IV | 101 | 49.3 |

| Unknown/ Not reported | 23 | 11.2 |

| Initial therapeutic intention | % | |

| Curative Intent | 119 | 58.0 |

| Palliative Intent | 86 | 42.0 |

| # of Palliative Lines of Treatment until CGP | % | |

| 0 | 17 | 8.3 |

| 1 | 52 | 25.4 |

| 2 | 52 | 25.4 |

| 3 | 42 | 20.5 |

| >3 | 42 | 20.5 |

| 3 (median) | 0 - 11 (range) |

| Tumor Type | Purpose of the test | Total | |||

| Few treatment options | Rare tumor | Unknown Primary | Advanced tumor at young age | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 86 | 6 | NA | 1 | 93 |

| Sarcomas | 27 | 1 | NA | NA | 28 |

| Breast & Gynecological | 25 | NA | NA | 1 | 26 |

| Head & Neck / Respiratory | 11 | 6 | NA | NA | 17 |

| Urological | 11 | 3 | NA | NA | 14 |

| Others | 5 | 5 | NA | NA | 10 |

| Central Nervous System | 8 | 1 | NA | NA | 9 |

| Unknown Primary | NA | NA | 8 | NA | 8 |

| Total | 173 (84.4%) | 22 (10.7%) | 8 (3.9%) | 2 (1.0%) | 205 |

|

Gastrointestinal 93 cases (643 alterations, 100%) |

Sarcomas 28 cases (96 alterations, 100%) |

Breast & Gynecological 26 cases (156 alterations, 100%) |

Head & Neck / Respiratory 17 cases (77 alterations, 100%) |

||||

| Genes | % | Genes | % | Genes | % | Genes | % |

| TP53 | 11.7 | TP53 | 16.7 | TP53 | 8.3 | TP53 | 15.6 |

| APC | 11.7 | CDKN2A | 5.2 | PIK3CA | 7.7 | BRAF | 5.2 |

| KRAS | 9.5 | ATRX | 4.2 | ESR1 | 4.5 | TERT | 3.9 |

| NRAS | 4.4 | CDKN2B | 4.2 | FGF3 | 3.8 | ARID1A | 2.6 |

| PIK3CA | 3.3 | PTEN | 4.2 | FGF4 | 3.8 | ASXL1 | 2.6 |

|

Urological 14 cases (83 alterations, 100%) |

Others 10 cases (60 alterations, 100%) |

Central Nervous System 9 cases (83 alterations, 100%) |

Unknown Primary 8 cases (46 alterations, 100%) |

||||

| Genes | % | Genes | % | Genes | % | Genes | % |

| TP53 | 10.8 | TP53 | 6.7 | TP53 | 9.6 | TP53 | 8.7 |

| MYC | 6.0 | APC | 5.0 | EGFR | 6.0 | ALK | 8.7 |

| APC | 3.6 | BRAF | 5.0 | CDKN2A | 4.8 | TET2 | 6.5 |

| AR | 3.6 | TERT | 5.0 | CDKN2B | 4.8 | CDKN2A | 4.3 |

| EGFR | 3.6 | ASXL1 | 3.3 | PIK3CA | 4.8 | CDKN2B | 4.3 |

| FRONTAL ID | Cancer Type | Actionable Alteration |

CGP-Targeted Treatment |

Disease control (in weeks) |

| 220 | Head and Neck Cancer | NTRK3 fusion | Entrectinib | 149 |

| 219 | Head and Neck Cancer | BRAF non-V600 mutation | Trametinib | 126 |

| 124 | Head and Neck Cancer | FBXW7 mutation | Everolimus | 95 |

| 1 | Head and Neck Cancer | BRAF V600E mutation | Dabrafenib and Trametinib |

84 |

| 149 | Head and Neck Cancer | ERBB2 amplification | Trastuzumab | 80 |

| 138 | Others | ATM mutation | Niraparib | 52 |

| 108 | Gynecological Cancer | TMB high | Pembrolizumab | 45 |

| 159 | Head and Neck Cancer | BRAF V600E mutation | Sorafenib & Dabrafenib-Trametinib |

45 |

| 52 | Others | BRAF V600E mutation | Dabrafenib & Trametinib |

45 |

| 123 | Pancreatic Cancer | BRAF V600E mutation | Dabrafenib & Trametinib |

37 |

| 179 | Colorectal Cancer | BRCA1/2 & BRIP1 mutations | Talazoparib | 36 |

| 153 | Colorectal Cancer | PIK3CA mutation | Alpelisib | 35 |

| 11 | Other Gastrointestinal Tumors |

MSI and TMB high | Pembrolizumab | 35 |

| 213 | Cholangiocarcinoma | HRAS mutation | Trametinib | 35 |

| 207 | Endocrine Cancer | TMB high | Pembrolizumab | 33 |

| 210 | Colorectal Cancer | NF1 large deletion | Trametinib | 30 |

| 90 | Cholangiocarcinoma | TMB high | Pembrolizumab | 30 |

| 161 | Unknown Primary Tumors |

ALK rearrangement | Entrectinib | 26 |

| 76 | Others | EGFR amplification | Anti-EGFR | 25 |

| 189 | Cholangiocarcinoma | FGFR2 rearrangement | Pemigatinib | 25 |

| 120 | Cholangiocarcinoma | TMB high | Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin | 24 |

| 151 | Colorectal Cancer | PIK3CA mutation | Alpelisib | 22 |

| 217 | Other Gastrointestinal Tumors |

BRCA2 mutation | Olaparib | 20 |

| 5 | Head and Neck Cancer | TMB high | Nivolumab and Ipilimumab | 20 |

| 111 | Breast Cancer | ESR1 mutation | Abemaciclib and Fulvestrant | 19 |

| 172 | Pancreatic Cancer | BRCA2 mutation | Olaparib | 19 |

| 112 | Gynecological Cancer | PIK3CA mutation | Everolimus and Letrozole | 19 |

| 182 | Colorectal Cancer | VEGFA amplification | Sorafenib | 18 |

| 70 | Sarcomas | ALK fusion | Alectinib | 17 |

| 145 | Other Gastrointestinal Tumors |

KIT mutation | Sorafenib | 17 |

|

Molecular Alteration |

Controlled disease |

% | Not Controlled disease | % | Total |

| MSI and/or TMB High | 6 | 50.0 | 6 | 50.0 | 12 |

| BRAF mutations | 5 | 83.3 | 1 | 16.7 | 6 |

| BRCA1/2 & BRIP1 mutations | 3 | 50.0 | 3 | 50.0 | 6 |

| PIK3CA mutations | 3 | 75.0 | 1 | 25.0 | 4 |

| ATM mutations | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 3 |

| ALK alterations | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 |

| ERBB2 amplification | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 2 |

| NF1 mutations | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 2 |

| EGFR amplification | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| ESR1 mutation | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| FBXW7 mutation | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| FGFR2 rearrangement | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| HRAS mutation | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| KIT mutation | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| NF1 large deletion | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| NTRK3 fusion | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| VEGFA amplification | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| GNA11 mutation | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 |

| KRAS mutation | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 |

| PDGFRA mutation | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 |

| PTCH1 mutation | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 |

| Total | 30 | 60.0 | 20 | 40.0 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).