Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

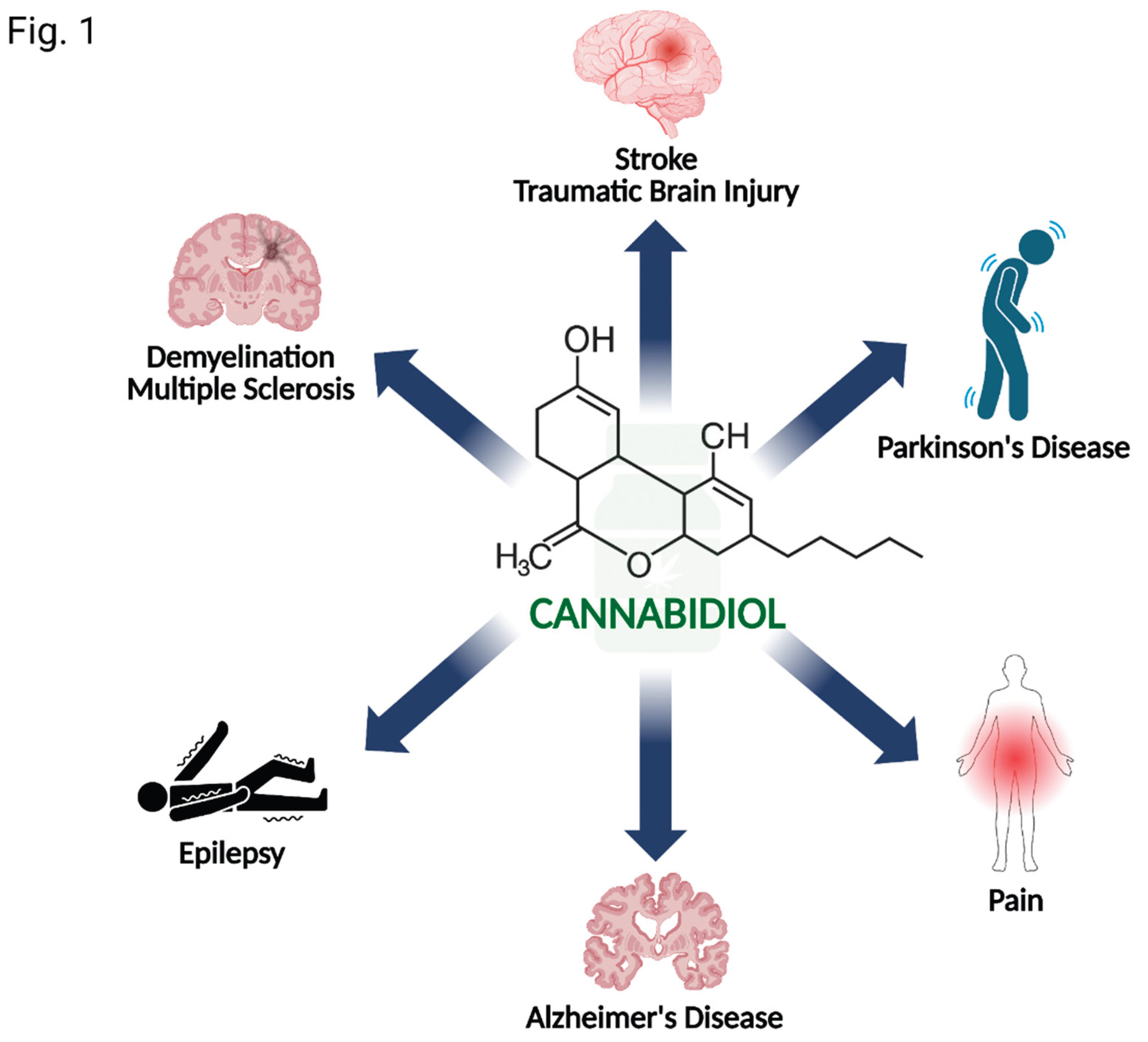

1. Introduction

2. Pharmacological Profile of CBD

3. Evidence in Specific Neurological Disorders

3.1. Epilepsy

3.2. Multiple Sclerosis

3.3. Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia

3.4. Parkinson’s Disease

3.5. Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injury

3.6. Neuropathic Pain

4. Challenges and Future Directions

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

Author’s Contribution

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piao, J.J.; Kim, S.; Shin, D.; Lee, H.J.; Jeon, K.-H.; Tian, W.J.; Hur, K.J.; Kang, J.S.; Park, H.-J.; Cha, J.Y.; et al. Cannabidiol Alleviates Chronic Prostatitis and Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome via CB2 Receptor Activation and TRPV1 Desensitization. World J. Mens Health 2025, 43, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieba, J.; Sinclair, D.; Sebree, T.; Bonn-Miller, M.; Gutterman, D.; Siegel, S.; Karl, T. Cannabidiol (CBD) Reduces Anxiety-Related Behavior in Mice via an FMRP-Independent Mechanism. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2019, 181, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesworth, R.; Cheng, D.; Staub, C.; Karl, T. Effect of Long-Term Cannabidiol on Learning and Anxiety in a Female Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 931384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-M.; Li, J.-C.; Gu, Y.-F.; Qiu, R.-H.; Huang, J.-Y.; Xue, R.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.-Z. Cannabidiol Exerts Sedative and Hypnotic Effects in Normal and Insomnia Model Mice Through Activation of 5-HT1A Receptor. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 49, 1150–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkhou, M.; Bedder, R.H.; George, T.P. The Behavioral Sequelae of Cannabis Use in Healthy People: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 630247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cásedas, G.; de Yarza-Sancho, M.; López, V. Cannabidiol (CBD): A Systematic Review of Clinical and Preclinical Evidence in the Treatment of Pain. Pharm. Basel Switz. 2024, 17, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrazzi, J.F.C.; Silva-Amaral, D.; Issy, A.C.; Gomes, F.V.; Crippa, J.A.; Guimarães, F.S.; Del Bel, E. Cannabidiol Attenuates Prepulse Inhibition Disruption by Facilitating TRPV1 and 5-HT1A Receptor-Mediated Neurotransmission. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2024, 245, 173879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldager, M.B.; Biojone, C.; da Silva, N.R.; Godoy, L.D.; Joca, S. New Insights into the Involvement of Serotonin and BDNF-TrkB Signalling in Cannabidiol’s Antidepressant Effect. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 133, 111029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annett, S.; Moore, G.; Robson, T. FK506 Binding Proteins and Inflammation Related Signalling Pathways; Basic Biology, Current Status and Future Prospects for Pharmacological Intervention. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 215, 107623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Xiao, Y.; Nakaya, M.; D’Angelillo, A.; Chang, M.; Jin, J.; Hausch, F.; Masullo, M.; Feng, X.; Romano, M.F.; et al. FKBP51 Employs Both Scaffold and Isomerase Functions to Promote NF-κB Activation in Melanoma. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 6983–6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, C.; Jin, S.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X. Cannabidiol Alleviates Neuroinflammation and Attenuates Neuropathic Pain via Targeting FKBP5. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2023, 111, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucca, E.; Bialer, M. Critical Aspects Affecting Cannabidiol Oral Bioavailability and Metabolic Elimination, and Related Clinical Implications. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, K.R.; Alghalayini, A.; Valenzuela, S.M. Current Challenges and Opportunities for Improved Cannabidiol Solubility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, S.A.; Stone, N.L.; Yates, A.S.; O’Sullivan, S.E. A Systematic Review on the Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol in Humans. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saals, B.A.D.F.; De Bie, T.H.; Osmanoglou, E.; van de Laar, T.; Tuin, A.W.; van Orten-Luiten, A.C.B.; Witkamp, R.F. A High-Fat Meal Significantly Impacts the Bioavailability and Biphasic Absorption of Cannabidiol (CBD) from a CBD-Rich Extract in Men and Women. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeo, G.; Kapoor, A.; Giorgetti, R.; Busardò, F.P.; Carlier, J. Update on Cannabidiol Clinical Toxicity and Adverse Effects: A Systematic Review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 2323–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Green, A.; Sovi, S.; Wilson, J.; Englund, A.; Freeman, T.P.; McGuire, P. Adverse Effects of Cannabidiol: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 45, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huestis, M.A.; Solimini, R.; Pichini, S.; Pacifici, R.; Carlier, J.; Busardò, F.P. Cannabidiol Adverse Effects and Toxicity. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 974–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholler, D.J.; Schoene, L.; Spindle, T.R. Therapeutic Efficacy of Cannabidiol (CBD): A Review of the Evidence from Clinical Trials and Human Laboratory Studies. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2020, 7, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Cross, J.H.; Laux, L.; Marsh, E.; Miller, I.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Thiele, E.A.; Wright, S. Trial of Cannabidiol for Drug-Resistant Seizures in the Dravet Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, E.A.; Marsh, E.D.; French, J.A.; Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska, M.; Benbadis, S.R.; Joshi, C.; Lyons, P.D.; Taylor, A.; Roberts, C.; Sommerville, K.; et al. Cannabidiol in Patients with Seizures Associated with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (GWPCARE4): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial. The Lancet 2018, 391, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devinsky, O.; Patel, A.D.; Cross, J.H.; Villanueva, V.; Wirrell, E.C.; Privitera, M.; Greenwood, S.M.; Roberts, C.; Checketts, D.; VanLandingham, K.E.; et al. Effect of Cannabidiol on Drop Seizures in the Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, T.J.; Berkovic, S.F.; French, J.A.; Messenheimer, J.A.; Sebree, T.B.; Bonn-Miller, M.O.; Gutterman, D.L. Adjunctive Transdermal Cannabidiol for Adults With Focal Epilepsy. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2220189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, E.; Marsh, E.; Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska, M.; Halford, J.J.; Gunning, B.; Devinsky, O.; Checketts, D.; Roberts, C. Cannabidiol in Patients with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome: Interim Analysis of an Open-Label Extension Study. Epilepsia 2019, 60, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.-A.; Farrar, M.; Cardamone, M.; Gill, D.; Smith, R.; Cowell, C.T.; Truong, L.; Lawson, J.A. Cannabidiol for Treating Drug-Resistant Epilepsy in Children: The New South Wales Experience. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, C.; Davies, P.; Mutiboko, I.K.; Ratcliffe, S. Sativex Spasticity in MS Study Group Randomized Controlled Trial of Cannabis-Based Medicine in Spasticity Caused by Multiple Sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007, 14, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovà, J.; Essner, U.; Akmaz, B.; Marinelli, M.; Trompke, C.; Lentschat, A.; Vila, C. Sativex® as Add-on Therapy vs. Further Optimized First-Line ANTispastics (SAVANT) in Resistant Multiple Sclerosis Spasticity: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomised Clinical Trial. Int. J. Neurosci. 2019, 129, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethoux, F.A.; Farrell, R.; Checketts, D.; Sahr, N.; Berwaerts, J.; Alexander, J.K.; Skobieranda, F. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Nabiximols Oromucosal Spray on Clinical Measures of Spasticity in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 89, 105740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, C.; Davies, P.; Mutiboko, I.K.; Ratcliffe, S. Sativex Spasticity in MS Study Group Randomized Controlled Trial of Cannabis-Based Medicine in Spasticity Caused by Multiple Sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007, 14, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, P.; Emadzadeh, M.; Karimikhoshnoudian, B.; Sahraian, M.A.; Ghaffari, M.; Shaygannejad, V.; Payere, M.; Baghaei, A.; Zabeti, A.; Nahayati, M. A Randomized Trial on Efficacy of Purified Cannabidiol on Spasticity in Multiple Sclerosis Patients with Gait Problems: First Report in Iran. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 17435–17444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayudhan, L.; Dugonjic, M.; Pisani, S.; Harborow, L.; Aarsland, D.; Bassett, P.; Bhattacharyya, S. Cannabidiol for Behavior Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease (CANBiS-AD): A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 1270–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertyn, C.P.; Guu, T.-W.; Chu, P.; Creese, B.; Young, A.; Velayudhan, L.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Jafari, H.; Kaur, S.; Kandangwa, P.; et al. Sativex (Nabiximols) for the Treatment of Agitation & Aggression in Alzheimer’s Dementia in UK Nursing Homes: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Feasibility Trial. Age Ageing 2025, 54, afaf149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V, H.; L, O.; N, S.; N, M.; M, F.; M, K.; E, S.; Ve, L.; B.-L.S., L. Effects of Rich Cannabidiol Oil on Behavioral Disturbances in Patients with Dementia: A Placebo Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Med. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitarnun, W.; Kanjanarangsichai, A.; Junlaor, P.; Kongngern, L.; Mitarnun, W.; Pangwong, W.; Nonghan, P. Cannabidiol and Cognitive Functions/Inflammatory Markers in Parkinson’s Disease: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial at Buriram Hospital (CBD-PD-BRH Trial). Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2025, 135, 107841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bainbridge, J.; Sillau, S.; Rajkovic, S.; Adkins, M.; Domen, C.H.; Thompson, J.A.; Seawalt, T.; Klawitter, J.; Sempio, C.; et al. Short-Term Cannabidiol with Δ-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Trial. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2024, 39, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria, S.M.; de Morais Fabrício, D.; Tumas, V.; Castro, P.C.; Ponti, M.A.; Hallak, J.E.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Chagas, M.H.N. Effects of Acute Cannabidiol Administration on Anxiety and Tremors Induced by a Simulated Public Speaking Test in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Psychopharmacol. Oxf. Engl. 2020, 34, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos de Alencar, S.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Brito, M.C.M.; Pimentel, Â.V.; Cecilio Hallak, J.E.; Tumas, V. A Single Oral Dose of Cannabidiol Did Not Reduce Upper Limb Tremor in Patients with Essential Tremor. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2021, 83, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, M.H.N.; Zuardi, A.W.; Tumas, V.; Pena-Pereira, M.A.; Sobreira, E.T.; Bergamaschi, M.M.; dos Santos, A.C.; Teixeira, A.L.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Crippa, J.A.S. Effects of Cannabidiol in the Treatment of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: An Exploratory Double-Blind Trial. J. Psychopharmacol. Oxf. Engl. 2014, 28, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.H.; Cullen, B.D.; Tang, M.; Fang, Y. The Effectiveness of Topical Cannabidiol Oil in Symptomatic Relief of Peripheral Neuropathy of the Lower Extremities. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, M.; Meissner, W.; Sator, S.; Keßler, J.; Schoder, V.; Häuser, W. Full-Spectrum Extract from Cannabis Sativa DKJ127 for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Phase 3 Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nat. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.S.; Acevedo, C.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Bogacz, A.; Cross, J.H.; Elger, C.E.; Engel, J.; Forsgren, L.; French, J.A.; Glynn, M.; et al. ILAE Official Report: A Practical Clinical Definition of Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludányi, A.; Erőss, L.; Czirják, S.; Vajda, J.; Halász, P.; Watanabe, M.; Palkovits, M.; Maglóczky, Z.; Freund, T.F.; Katona, I. Downregulation of the CB1 Cannabinoid Receptor and Related Molecular Elements of the Endocannabinoid System in Epileptic Human Hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 2976–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maglóczky, Z.; Tóth, K.; Karlócai, R.; Nagy, S.; Erőss, L.; Czirják, S.; Vajda, J.; Rásonyi, G.; Kelemen, A.; Juhos, V.; et al. Dynamic Changes of CB1-receptor Expression in Hippocampi of Epileptic Mice and Humans. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fezza, F.; Marrone, M.C.; Avvisati, R.; Di Tommaso, M.; Lanuti, M.; Rapino, C.; Mercuri, N.B.; Maccarrone, M.; Marinelli, S. Distinct Modulation of the Endocannabinoid System upon Kainic Acid-Induced in Vivo Seizures and in Vitro Epileptiform Bursting. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.J.; Blair, R.E.; Falenski, K.W.; Martin, B.R.; DeLorenzo, R.J. The Endogenous Cannabinoid System Regulates Seizure Frequency and Duration in a Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 307, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsicano, G.; Goodenough, S.; Monory, K.; Hermann, H.; Eder, M.; Cannich, A.; Azad, S.C.; Cascio, M.G.; Gutiérrez, S.O.; Van Der Stelt, M.; et al. CB1 Cannabinoid Receptors and On-Demand Defense Against Excitotoxicity. Science 2003, 302, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugaya, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Uchigashima, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Watanabe, M.; Sakimura, K.; Kano, M. Crucial Roles of the Endocannabinoid 2-Arachidonoylglycerol in the Suppression of Epileptic Seizures. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epilepsy: Its Symptoms, Treatment, and Relation to Other Chronic Convulsive Diseases. Br. Foreign Medico-Chir. Rev. 1862, 30, 309–312.

- Epilepsy and Other Chronic Convulsive Diseases: Their Causes, Symptoms & Treatment - Digital Collections - National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-100954847-bk (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Chiu, P.; Olsen, D.M.; Borys, H.K.; Karler, R.; Turkanis, S.A. The Influence of Cannabidiol and Delta 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol on Cobalt Epilepsy in Rats. Epilepsia 1979, 20, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landucci, E.; Mazzantini, C.; Lana, D.; Calvani, M.; Magni, G.; Giovannini, M.G.; Pellegrini-Giampietro, D.E. Cannabidiol Inhibits Microglia Activation and Mitigates Neuronal Damage Induced by Kainate in an In-Vitro Seizure Model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 174, 105895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Shekh-Ahmad, T.; Khalil, A.; Walker, M.C.; Ali, A.B. Cannabidiol Exerts Antiepileptic Effects by Restoring Hippocampal Interneuron Functions in a Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Model. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 2097–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.A.; Hill, A.J.; Smith, I.; Bevan, S.A.; Williams, C.M.; Whalley, B.J.; Stephens, G.J. Cannabidiol Displays Antiepileptiform and Antiseizure Properties In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 332, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadzadeh, Y.; Santos, A.; Aquilino, M.S.; Mylvaganam, S.; Urban, K.; Carlen, P.L. Cannabidiol Exerts Anticonvulsant Effects Alone and in Combination with Δ9-THC through the 5-HT1A Receptor in the Neocortex of Mice. Cells 2024, 13, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Aguirre, C.; Márquez, L.A.; Santiago-Castañeda, C.L.; Carmona-Cruz, F.; Nuñez-Lumbreras, M. de los A.; Martínez-Rojas, V.A.; Alonso-Vanegas, M.; Aguado-Carrillo, G.; Gómez-Víquez, N.L.; Galván, E.J.; et al. Cannabidiol Modifies the Glutamate Over-Release in Brain Tissue of Patients and Rats with Epilepsy: A Pilot Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Rojas, V.A.; Márquez, L.A.; Martinez-Aguirre, C.; Sollozo-Dupont, I.; López Preza, F.I.; Fuentes Mejía, M.; Alonso, M.; Rocha, L.; Galván, E.J. Cannabidiol Reduces Synaptic Strength and Neuronal Firing in Layer V Pyramidal Neurons of the Human Cortex with Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1627465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Jin, B.; Qin, X.; Zhu, X.; Sun, J.; Huo, L.; Wang, R.; Shi, Y.; Jia, Z.; et al. Cannabidiol Inhibits Febrile Seizure by Modulating AMPA Receptor Kinetics through Its Interaction with the N-Terminal Domain of GluA1/GluA2. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 161, 105128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, C.; Liu, S.; Rong, Y.; Tian, J.; Peng, C.; Shao, Y.; Ma, Z.; et al. The DEC2-SCN2A Axis Is Essential for the Anticonvulsant Effects of Cannabidiol by Modulating Neuronal Plasticity. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e16315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debski, K.J.; Ceglia, N.; Ghestem, A.; Ivanov, A.I.; Brancati, G.E.; Bröer, S.; Bot, A.M.; Müller, J.A.; Schoch, S.; Becker, A.; et al. The Circadian Dynamics of the Hippocampal Transcriptome and Proteome Is Altered in Experimental Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaat5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, S.; Quigley, A.; Rochfort, S.; Christodoulou, J.; Van Bergen, N.J. Cannabinoids and Genetic Epilepsy Models: A Review with Focus on CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker-Haliski, M.; Hawkins, N.A. Innovative Drug Discovery Strategies in Epilepsy: Integrating next-Generation Syndrome-Specific Mouse Models to Address Pharmacoresistance and Epileptogenesis. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2024, 19, 1099–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, K.L.; Udoh, M.; Sharman, L.A.; Harman, T.; Bedoya-Pérez, M.; Anderson, L.L.; Banister, S.D.; Arnold, J.C. Cannabinoid-like Compounds Found in Non-Cannabis Plants Exhibit Antiseizure Activity in Genetic Mouse Models of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2025, 66, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Hai, D.; Yu, J.; Tang, S.; Liu, N.; Liu, Y. Cannabidiol Ameliorates Seizures and Neuronal Damage in Ferric Chloride-Induced Posttraumatic Epilepsy by Targeting TRPV1 Channel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 351, 120072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Cairasco, N.; Umeoka, E.H.L.; Cortes de Oliveira, J.A. The Wistar Audiogenic Rat (WAR) Strain and Its Contributions to Epileptology and Related Comorbidities: History and Perspectives. Epilepsy Behav. EB 2017, 71, 250–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, R.M.; Iannotti, F.A.; Amodeo, P. The (Poly)Pharmacology of Cannabidiol in Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Molecular Mechanisms and Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.A.; Glyn, S.E.; Akiyama, S.; Hill, T.D.M.; Hill, A.J.; Weston, S.E.; Burnett, M.D.A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Stephens, G.J.; Whalley, B.J.; et al. Cannabidiol Exerts Anti-Convulsant Effects in Animal Models of Temporal Lobe and Partial Seizures. Seizure 2012, 21, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Madaan, P.; Bansal, D. Update on Cannabidiol in Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Indian J. Pediatr. 2025, 92, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchio, N.; Auvin, S.; Greco, T.; Lagae, L.; Nortvedt, C.; Zuberi, S.M. Clinically Meaningful Reduction in Drop Seizures in Patients with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Treated with Cannabidiol: Post Hoc Analysis of Phase 3 Clinical Trials. CNS Drugs 2025, 39, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Patel, A.D.; Thiele, E.A.; Wong, M.H.; Appleton, R.; Harden, C.L.; Greenwood, S.; Morrison, G.; Sommerville, K. On behalf of the GWPCARE1 Part A Study Group; et al. Randomized, Dose-Ranging Safety Trial of Cannabidiol in Dravet Syndrome. Neurology 2018, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Patel, A.D.; Cross, J.H.; Villanueva, V.; Wirrell, E.C.; Privitera, M.; Greenwood, S.M.; Roberts, C.; Checketts, D.; VanLandingham, K.E.; et al. Effect of Cannabidiol on Drop Seizures in the Lennox–Gastaut Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Cross, J.H.; Laux, L.; Marsh, E.; Miller, I.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Thiele, E.A.; Wright, S. Cannabidiol in Dravet Syndrome Study Group Trial of Cannabidiol for Drug-Resistant Seizures in the Dravet Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börnsen, L.; Romme Christensen, J.; Ratzer, R.; Hedegaard, C.; Søndergaard, H.B.; Krakauer, M.; Hesse, D.; Nielsen, C.H.; Sorensen, P.S.; Sellebjerg, F. Endogenous Interferon-β-Inducible Gene Expression and Interferon-β-Treatment Are Associated with Reduced T Cell Responses to Myelin Basic Protein in Multiple Sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete, C.; García-Martín, A.; Rolland, A.; DeMesa, J.; Muñoz, E. Cannabidiol and Other Cannabinoids in Demyelinating Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaszewska-Zaremba, D.; Gajewska, A.; Misztal, T. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Cannabinoids in Therapy of Neurodegenerative Disorders and Inflammatory Diseases of the CNS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleisher-Berkovich, S.; Sharon, N.; Ventura, Y.; Feinshtein, V.; Gorelick, J.; Bernstein, N.; Ben-Shabat, S. Selected Cannabis Cultivars Modulate Glial Activation: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. J. Cannabis Res. 2024, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, C.; García-Martín, A.; Correa-Sáez, A.; Prados, M.E.; Fernández, F.; Pineda, R.; Mazzone, M.; Álvarez-Benito, M.; Calzado, M.A.; Muñoz, E. A Cannabidiol Aminoquinone Derivative Activates the PP2A/B55α/HIF Pathway and Shows Protective Effects in a Murine Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.S.; Riordan, S.M.; Gernon, M.C.; Koulen, P. Cannabinoids and Endocannabinoids as Therapeutics for Nervous System Disorders: Preclinical Models and Clinical Studies. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furgiuele, A.; Cosentino, M.; Ferrari, M.; Marino, F. Immunomodulatory Potential of Cannabidiol in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021, 16, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, É.; Vlachou, S. A Critical Review of the Role of the Cannabinoid Compounds Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) and Cannabidiol (CBD) and Their Combination in Multiple Sclerosis Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D.M.; Singh, N.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.S. Cannabidiol Attenuates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Model of Multiple Sclerosis Through Induction of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, C.; Torres, I.M.; García-Hernández, R.; Campos-Ruíz, L.; Esparragoza, L.R.; Coronado, M.J.; Grande, A.G.; García-Merino, A.; Sánchez López, A.J. Mechanisms of Action of Cannabidiol in Adoptively Transferred Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 298, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozela, E.; Lev, N.; Kaushansky, N.; Eilam, R.; Rimmerman, N.; Levy, R.; Ben-Nun, A.; Juknat, A.; Vogel, Z. Cannabidiol Inhibits Pathogenic T Cells, Decreases Spinal Microglial Activation and Ameliorates Multiple Sclerosis-like Disease in C57BL/6 Mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; Faizi, M.; Talebi, F.; Noorbakhsh, F.; Kahrizi, F.; Naderi, N. Interaction between the Protective Effects of Cannabidiol and Palmitoylethanolamide in Experimental Model of Multiple Sclerosis in C57BL/6 Mice. Neuroscience 2015, 290, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhavan Tavakoli, M.; Soleimani, M.; Marzban, H.; Shabani, R.; Moradi, F.; Ajdary, M.; Mehdizadeh, M. Autophagic Molecular Alterations in the Mouse Cerebellum Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Model Following Treatment with Cannabidiol and Fluoxetine. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 1797–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitarelli da Silva, T.; Bernardes, D.; Oliveira-Lima, O.C.; Fernandes Pinto, B.; Limborço Filho, M.; Fraga Faraco, C.C.; Juliano, M.A.; Esteves Arantes, R.M.; A Moreira, F.; Carvalho-Tavares, J. Cannabidiol Attenuates In Vivo Leukocyte Recruitment to the Spinal Cord Microvasculature at Peak Disease of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2024, 9, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, D.M.; Singh, N.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.S. Cannabidiol Attenuates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Model of Multiple Sclerosis Through Induction of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghezi, Z.Z.; Miranda, K.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.S. Combination of Cannabinoids, Δ9- Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol, Ameliorates Experimental Multiple Sclerosis by Suppressing Neuroinflammation Through Regulation of miRNA-Mediated Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghezi, Z.Z.; Busbee, P.B.; Alghetaa, H.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. Combination of Cannabinoids, Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and Cannabidiol (CBD), Mitigates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE) by Altering the Gut Microbiome. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2019, 82, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.P. Sativex®: Clinical Efficacy and Tolerability in the Treatment of Symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis and Neuropathic Pain. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2006, 7, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre-Garriga, J.; Vila, C.; Clissold, S.; Montalban, X. THC and CBD Oromucosal Spray (Sativex®) in the Management of Spasticity Associated with Multiple Sclerosis. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2011, 11, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermersch, P. Sativex(®) (Tetrahydrocannabinol + Cannabidiol), an Endocannabinoid System Modulator: Basic Features and Main Clinical Data. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2011, 11, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Calabrò, R.S.; Naro, A.; Sessa, E.; Rifici, C.; D’Aleo, G.; Leo, A.; De Luca, R.; Quartarone, A.; Bramanti, P. Sativex in the Management of Multiple Sclerosis-Related Spasticity: Role of the Corticospinal Modulation. Neural Plast. 2015, 2015, 656582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragona, M.; Onesti, E.; Tomassini, V.; Conte, A.; Gupta, S.; Gilio, F.; Pantano, P.; Pozzilli, C.; Inghilleri, M. Psychopathological and Cognitive Effects of Therapeutic Cannabinoids in Multiple Sclerosis: A Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled, Crossover Study. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2009, 32, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachová, M.; Novotná, A.; Mares, J. A Multicentre, Double-Blind, Randomised, Parallel-Group, Placebo-Controlled Study of Effect of Long-Term Sativex® Treatment on Cognition and Mood of Patients with Spasticity Due to Multiple Sclerosis. J. Mult. Scler. 2013, 01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoedel, K.A.; Chen, N.; Hilliard, A.; White, L.; Stott, C.; Russo, E.; Wright, S.; Guy, G.; Romach, M.K.; Sellers, E.M. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study to Evaluate the Subjective Abuse Potential and Cognitive Effects of Nabiximols Oromucosal Spray in Subjects with a History of Recreational Cannabis Use. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 26, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’hooghe, M.; Willekens, B.; Delvaux, V.; D’haeseleer, M.; Guillaume, D.; Laureys, G.; Nagels, G.; Vanderdonckt, P.; Van Pesch, V.; Popescu, V. Sativex® (Nabiximols) Cannabinoid Oromucosal Spray in Patients with Resistant Multiple Sclerosis Spasticity: The Belgian Experience. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D. Evaluation of the Safety and Tolerability Profile of Sativex: Is It Reassuring Enough? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2012, 12, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK/H/2462/001/DC; Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency Sativex Oromucosal Spray. Public Assessment Report. 2010.

- Toledano, R.S.; Akirav, I. Cannabidiol Prevents Cognitive and Social Deficits in a Male Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease through CB1 Activation and Inflammation Modulation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, F.L.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Becher, B. Immune Attack: The Role of Inflammation in Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Barger, S.; Barnum, S.; Bradt, B.; Bauer, J.; Cole, G.M.; Cooper, N.R.; Eikelenboom, P.; Emmerling, M.; Fiebich, B.L.; et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2000, 21, 383–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Fisher, D.W.; Rodriguez, G.; Yu, T.; Dong, H. Comparisons of Neuroinflammation, Microglial Activation, and Degeneration of the Locus Coeruleus-Norepinephrine System in APP/PS1 and Aging Mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello-Hortega, J.V.; de Oliveira, C.S.; de Araujo, V.S.; Furtado-Alle, L.; Tureck, L.V.; Souza, R.L.R. Cannabidiol and Alzheimer Disease: A Comprehensive Review and In Silico Insights Into Molecular Interactions. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2025, 62, e70229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, H. Memory Loss in Alzheimer’s Disease. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 15, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raïch, I.; Lillo, J.; Rebassa, J.B.; Griñán-Ferré, C.; Bellver-Sanchis, A.; Reyes-Resina, I.; Franco, R.; Pallàs, M.; Navarro, G. Cannabidiol as a Multifaceted Therapeutic Agent: Mitigating Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Enhancing Cognitive Function. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado, K.D.C.B.; Nascimento, R.G. de F.; Coelho, P.J.F.N.; Oliveira, L.A.M.; Nogueira, K.O.P.C. Cannabidiol Protects Mouse Hippocampal Neurons from Neurotoxicity Induced by Amyloid β-Peptide25-35. Toxicol. Vitro Int. J. Publ. Assoc. BIBRA 2024, 99, 105880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, G.; De Filippis, D.; Maiuri, M.C.; De Stefano, D.; Carnuccio, R.; Iuvone, T. Cannabidiol Inhibits Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Protein Expression and Nitric Oxide Production in Beta-Amyloid Stimulated PC12 Neurons through P38 MAP Kinase and NF-kappaB Involvement. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 399, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, S.; Riazi, G.; Ashrafi-Kooshk, M.R.; Meknatkhah, S.; Ahmadian, S.; Hooshyari Ardakani, M.; Hosseinkhani, B. Cannabidiol Inhibits Tau Aggregation In Vitro. Cells 2021, 10, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, M.; Watt, G.; Kreilaus, F.; Karl, T. Medium-Dose Chronic Cannabidiol Treatment Reverses Object Recognition Memory Deficits of APP Swe /PS1ΔE9 Transgenic Female Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 587604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanta, A.K.; Chaulagain, B.; Gothwal, A.; Singh, J. Engineered PLGA Nanoparticles for Brain-Targeted Codelivery of Cannabidiol and pApoE2 through the Intranasal Route for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 3533–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanta, A.K.; Chaulagain, B.; Trivedi, R.; Singh, J. Mannose-Functionalized Chitosan-Coated PLGA Nanoparticles for Brain-Targeted Codelivery of CBD and BDNF for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 4021–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Faria, D.; Estessi de Souza, L.; Duran, F.L. de S.; Buchpiguel, C.A.; Britto, L.R.; Crippa, J.A. de S.; Filho, G.B.; Real, C.C. Cannabidiol Treatment Improves Glucose Metabolism and Memory in Streptozotocin-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Rat Model: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodland, M.N.; Banerjee, S.; Niehoff, M.L.; Young, B.J.; Macarthur, H.; Butler, A.A.; Morley, J.E.; Farr, S.A. Cannabidiol Improves Learning and Memory Deficits and Alleviates Anxiety in 12-Month-Old SAMP8 Mice. PLOS One 2025, 20, e0296586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.-Q.; Jia, J.-X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.-J.; Yang, Z.-J.; Wang, X.-X.; Yan, X.-S. Cannabidiol Improves the Cognitive Function of SAMP8 AD Model Mice Involving the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, G.; Shang, K.; Zieba, J.; Olaya, J.; Li, H.; Garner, B.; Karl, T. Chronic Treatment with 50 Mg/Kg Cannabidiol Improves Cognition and Moderately Reduces Aβ40 Levels in 12-Month-Old Male AβPPswe/PS1ΔE9 Transgenic Mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2020, 74, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, M.F. The Relationship Between Anxiety and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 2021, 5, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, H.; Salles, É.L.; Jarrahi, A.; Costigliola, V.; Khan, M.; Yu, J.C.; Morgan, J.C.; Hess, D.C.; Vaibhav, K.; Dhandapani, K.M.; et al. Cannabidiol Ameliorates Cognitive Function via Regulation of IL-33 and TREM2 Upregulation in a Murine Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 80, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishara, M.A.; Chum, P.P.; Miot, F.E.L.; Hooda, A.; Hartman, R.E.; Behringer, E.J. Molecular Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease Onset in a Mouse Model: Effects of Cannabidiol Treatment. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1667585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, C.; Steardo, L.; Esposito, G. Cannabidiol Promotes Amyloid Precursor Protein Ubiquitination and Reduction of Beta Amyloid Expression in SHSY5YAPP+ Cells through PPARγ Involvement. Phytother. Res. PTR 2014, 28, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drożak, P.; Skrobas, U.; Drożak, M. Cannabidiol in the Treatment and Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease – a Comprehensive Overview of in Vitro and in Vivo Studies. J. Educ. Health Sport 2022, 12, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, E.; Sánchez-Pla, A.; Vegas-Lozano, E.; Maldonado, R.; Ferrer, I. Cannabis-Based Medicine Reduces Multiple Pathological Processes in AβPP/PS1 Mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2015, 43, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Spiro, A.S.; Jenner, A.M.; Garner, B.; Karl, T. Long-Term Cannabidiol Treatment Prevents the Development of Social Recognition Memory Deficits in Alzheimer’s Disease Transgenic Mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2014, 42, 1383–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Feng, Y. Cannabidiol (CBD) Enhanced the Hippocampal Immune Response and Autophagy of APP/PS1 Alzheimer’s Mice Uncovered by RNA-Seq. Life Sci. 2021, 264, 118624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnanz, M.A.; Ruiz de Martín Esteban, S.; Martínez Relimpio, A.M.; Rimmerman, N.; Tweezer Zaks, N.; Grande, M.T.; Romero, J. Effects of Chronic, Low-Dose Cannabinoids, Cannabidiol, Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and a Combination of Both, on Amyloid Pathology in the 5xFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2024, 9, 1312–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Fernández, N.; Gómez-Acero, L.; Castañé, A.; Adell, A.; Campa, L.; Bonaventura, J.; Brito, V.; Ginés, S.; Queiróz, F.; Silva, H.; et al. A Combination of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol Modulates Glutamate Dynamics in the Hippocampus of an Animal Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aumer, B.; Rosa-Porto, R.; Coles, M.; Ulmer, N.; Watt, G.; Kielstein, H.; Karl, T. Combination Treatment with Medium Dose THC and CBD Had No Therapeutic Effect in a Transgenic Mouse Model for Alzheimer’s Disease but Affected Other Domains Including Anxiety-Related Behaviours and Object Recognition Memory. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2025, 174101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, O.P.; Lemmer, Y.; Mason, S. A Narrative Review of the Therapeutic and Remedial Prospects of Cannabidiol with Emphasis on Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. J. Cannabis Res. 2024, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkhondeh, T.; Khan, H.; Aschner, M.; Samini, F.; Pourbagher-Shahri, A.M.; Aramjoo, H.; Roshanravan, B.; Hoyte, C.; Mehrpour, O.; Samarghandian, S. Impact of Cannabis-Based Medicine on Alzheimer’s Disease by Focusing on the Amyloid β-Modifications: A Systematic Study. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2020, 19, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahji, A.; Meyyappan, A.C.; Hawken, E.R. Cannabinoids for the Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2020, 65, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broers, B.; Bianchi, F. Cannabinoids for Behavioral Symptoms in Dementia: An Overview. Pharmacopsychiatry 2024, 57, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, L.; Alexandri, F.; Tsolaki, A.; Moraitou, D.; Konsta, A.; Tsolaki, M. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia. The Added Value of Cannabinoids. Are They a Safe and Effective Choice? Case Series with Cannabidiol 3%. Ann. Case Rep. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandri, F.; Papadopoulou, L.; Tsolaki, A.; Papantoniou, G.; Athanasiadis, L.; Tsolaki, M. The Effect of Cannabidiol 3% on Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia - Six-Month Follow-Up. Clin. Gerontol. 2024, 47, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermush, V.; Ore, L.; Stern, N.; Mizrahi, N.; Fried, M.; Krivoshey, M.; Staghon, E.; Lederman, V.E.; Bar-Lev Schleider, L. Effects of Rich Cannabidiol Oil on Behavioral Disturbances in Patients with Dementia: A Placebo Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 951889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.E.; Pérez, J.C. Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease with a Cannabis-Based Magistral Formulation: An Open-Label Prospective Cohort Study. Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2024, 7, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, K.; Patel, A.; Ansari, S.; Shet, P.; Panag, S.S. Cannabinoids in Treating Parkinson’s Disease Symptoms: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2023, 8, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Bainbridge, J.; Sillau, S.; Rajkovic, S.; Adkins, M.; Domen, C.H.; Thompson, J.A.; Seawalt, T.; Klawitter, J.; Sempio, C.; et al. Short-Term Cannabidiol with Δ-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Trial. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2024, 39, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esfandi, A.; Mehrafarin, A.; Kalateh Jari, S.; Naghdi Badi, H.; Larijani, K. Cannabidiol Extracted from Cannabis Sativa L. Plant Shows Neuroprotective Impacts Against 6-HODA-Induced Neurotoxicity via Nrf2 Signal Transduction Pathway. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. IJPR 2025, 24, e160499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, C.; Francavilla, M.; Ongari, G.; Petese, A.; Ghezzi, C.; Rossini, N.; Blandini, F.; Cerri, S. Neuroprotective and Symptomatic Effects of Cannabidiol in an Animal Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivelaro do Nascimento, G.; Ferrari, D.P.; Guimaraes, F.S.; Del Bel, E.A.; Bortolanza, M.; Ferreira-Junior, N.C. Cannabidiol Increases the Nociceptive Threshold in a Preclinical Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neuropharmacology 2020, 163, 107808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.C.; Bioni, V.S.; Becegato, M.S.; Meier, Y.; Cunha, D.M.G.; Aguiar, N.A.; Gonçalves, N.; Peres, F.F.; Zuardi, A.W.; Hallak, J.E.C.; et al. Preventive Beneficial Effects of Cannabidiol in a Reserpine-Induced Progressive Model of Parkinsonism. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1539783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.C.D.; de Aquino, P.E.A.; Rebouças, C. da S.M.; Sallem, C.C.; Guizardi, M.P.P.; Noleto, F.M.; Zampieri, D. de S.; Ricardo, N.M.P.S.; de Brito, D.H.A.; Silveira, E.R.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects of a Cannabidiol Nanoemulsion in a Rotenone-Induced Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease: Insights into the Gut-Brain Axis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1002, 177748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, G.C.; Bálico, G.G.; de Mattos, B.A.; Dos-Santos-Pereira, M.; Oliveira, I.G.C.; Queiroz, M.E.C.; do Carmo Heck, L.; Navegantes, L.C.; Guimarães, F.S.; Del-Bel, E. Cannabidiol Improves L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia and Modulates Neuroinflammation and the Endocannabinoid, Endovanilloid and Nitrergic Systems. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 141, 111456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapmanee, S.; Bhubhanil, S.; Wongchitrat, P.; Charoenphon, N.; Inchan, A.; Ngernsutivorakul, T.; Dechbumroong, P.; Khongkow, M.; Namdee, K. Assessing the Safety and Therapeutic Efficacy of Cannabidiol Lipid Nanoparticles in Alleviating Metabolic and Memory Impairments and Hippocampal Histopathological Changes in Diabetic Parkinson’s Rats. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitarnun, W.; Kanjanarangsichai, A.; Junlaor, P.; Kongngern, L.; Mitarnun, W.; Pangwong, W.; Nonghan, P. Cannabidiol and Cognitive Functions/Inflammatory Markers in Parkinson’s Disease: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial at Buriram Hospital (CBD-PD-BRH Trial). Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2025, 135, 107841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Faria, S.M.; de Morais Fabrício, D.; Tumas, V.; Castro, P.C.; Ponti, M.A.; Hallak, J.E.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Chagas, M.H.N. Effects of Acute Cannabidiol Administration on Anxiety and Tremors Induced by a Simulated Public Speaking Test in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Psychopharmacol. Oxf. Engl. 2020, 34, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos de Alencar, S.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Brito, M.C.M.; Pimentel, Â.V.; Cecilio Hallak, J.E.; Tumas, V. A Single Oral Dose of Cannabidiol Did Not Reduce Upper Limb Tremor in Patients with Essential Tremor. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2021, 83, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, M.H.N.; Zuardi, A.W.; Tumas, V.; Pena-Pereira, M.A.; Sobreira, E.T.; Bergamaschi, M.M.; dos Santos, A.C.; Teixeira, A.L.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Crippa, J.A.S. Effects of Cannabidiol in the Treatment of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: An Exploratory Double-Blind Trial. J. Psychopharmacol. Oxf. Engl. 2014, 28, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belardo, C.; Iannotta, M.; Boccella, S.; Rubino, R.C.; Ricciardi, F.; Infantino, R.; Pieretti, G.; Stella, L.; Paino, S.; Marabese, I.; et al. Oral Cannabidiol Prevents Allodynia and Neurological Dysfunctions in a Mouse Model of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.; Rieder, P.; Gobbo, D.; Candido, G.; Scheller, A.; de Oliveira, R.M.W.; Kirchhoff, F. Cannabidiol Exerts a Neuroprotective and Glia-Balancing Effect in the Subacute Phase of Stroke. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.-T.; Li, M.-F.; Chen, K.-C.; Li, X.; Cai, N.-B.; Xu, J.-P.; Wang, H.-T. Mitofusin-2 Mediates Cannabidiol-Induced Neuroprotection against Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Xu, B.; Xiao, X.; Long, L.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, Z.; Tu, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, H. Involvement of CKS1B in the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Cannabidiol in Experimental Stroke Models. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 373, 114654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhao, H.; Nie, M.; Sha, Z.; Feng, J.; Liu, M.; Lv, C.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, W.; Yuan, J.; et al. Cannabidiol Alleviates Neurological Deficits After Traumatic Brain Injury by Improving Intracranial Lymphatic Drainage. J. Neurotrauma 2024, 41, e2009–e2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Castañeda, C.; Huerta de la Cruz, S.; Martínez-Aguirre, C.; Orozco-Suárez, S.A.; Rocha, L. Cannabidiol Reduces Short- and Long-Term High Glutamate Release after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury and Improves Functional Recovery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepulveda, D.E.; Vrana, K.E.; Graziane, N.M.; Raup-Konsavage, W.M. Combinations of Cannabidiol and Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Reducing Chemotherapeutic Induced Neuropathic Pain. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus, C.H.A.; Ferreira, M.V.; Gasparin, A.T.; Rosa, E.S.; Genaro, K.; Crippa, J.A. de S.; Chichorro, J.G.; Cunha, J.M. da Cannabidiol Enhances the Antinociceptive Effects of Morphine and Attenuates Opioid-Induced Tolerance in the Chronic Constriction Injury Model. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 435, 114076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.D.; Leung, E.J.Y.; Wong, B.A.; Rivera, Z.M.G.; Kruse, L.C.; Clark, J.J.; Land, B.B. Orally Consumed Cannabinoids Provide Long-Lasting Relief of Allodynia in a Mouse Model of Chronic Neuropathic Pain. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 45, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.A.; Harley, J.; Casey, S.L.; Vaughan, A.C.; Winters, B.L.; Vaughan, C.W. Oral Efficacy of Δ(9)-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol in a Mouse Neuropathic Pain Model. Neuropharmacology 2021, 189, 108529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, J.D.; Farkas, D.J.; Huynh, L.M.; Kinney, W.A.; Brenneman, D.E.; Ward, S.J. Behavioural and Pharmacological Effects of Cannabidiol (CBD) and the Cannabidiol Analogue KLS-13019 in Mouse Models of Pain and Reinforcement. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 3067–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.; Veras, F.; Netto, G.; Elisei, L.; Sorgi, C.; Faccioli, L.; Galdino, G. Cannabidiol Prevents Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain by Modulating Spinal TLR4 via Endocannabinoid System Activation. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2023, 75, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccella, S.; Fusco, A.; Ricciardi, F.; Morace, A.M.; Bonsale, R.; Perrone, M.; Marabese, I.; De Gregorio, D.; Belardo, C.; Posa, L.; et al. Acute Kappa Opioid Receptor Blocking Disrupts the Pro-Cognitive Effect of Cannabidiol in Neuropathic Rats. Neuropharmacology 2025, 266, 110265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.H.; Cullen, B.D.; Tang, M.; Fang, Y. The Effectiveness of Topical Cannabidiol Oil in Symptomatic Relief of Peripheral Neuropathy of the Lower Extremities. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Li, G.; Stephens, K.L.; Timko, M.P.; DeGeorge, B.R. The Use of Cannabinoids in the Treatment of Peripheral Neuropathy and Neuropathic Pain: A Systematic Review. J. Hand Surg. 2025, 50, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, M.; Meissner, W.; Sator, S.; Keßler, J.; Schoder, V.; Häuser, W. Full-Spectrum Extract from Cannabis Sativa DKJ127 for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Phase 3 Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 4189–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vela, J.; Dreyer, L.; Petersen, K.K.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Duch, K.S.; Kristensen, S. Cannabidiol Treatment in Hand Osteoarthritis and Psoriatic Arthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Pain 2022, 163, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubcevic, K.; Petersen, M.; Bach, F.W.; Heinesen, A.; Enggaard, T.P.; Almdal, T.P.; Holbech, J.V.; Vase, L.; Jensen, T.S.; Hansen, C.S.; et al. Oral Capsules of Tetra-Hydro-Cannabinol (THC), Cannabidiol (CBD) and Their Combination in Peripheral Neuropathic Pain Treatment. Eur. J. Pain 2023, 27, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagredo, O.; Pazos, M.R.; Satta, V.; Ramos, J.A.; Pertwee, R.G.; Fernández-Ruiz, J. Neuroprotective Effects of Phytocannabinoid-Based Medicines in Experimental Models of Huntington’s Disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2011, 89, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdeolivas, S.; Sagredo, O.; Delgado, M.; Pozo, M.A.; Fernández-Ruiz, J. Effects of a Sativex-Like Combination of Phytocannabinoids on Disease Progression in R6/2 Mice, an Experimental Model of Huntington’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consroe, P.; Laguna, J.; Allender, J.; Snider, S.; Stern, L.; Sandyk, R.; Kennedy, K.; Schram, K. Controlled Clinical Trial of Cannabidiol in Huntington’s Disease. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991, 40, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, S.; Kloiber, S.; Le Foll, B. Effects of Cannabidiol (CBD) in Neuropsychiatric Disorders: A Review of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Findings. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 167, 25–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sendón Moreno, J.L.; García Caldentey, J.; Trigo Cubillo, P.; Ruiz Romero, C.; García Ribas, G.; Alonso Arias, M.A.A.; García de Yébenes, M.J.; Tolón, R.M.; Galve-Roperh, I.; Sagredo, O.; et al. A Double-Blind, Randomized, Cross-over, Placebo-Controlled, Pilot Trial with Sativex in Huntington’s Disease. J. Neurol. 2016, 263, 1390–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.; Greer, R.; Huggett, G.; Kearney, A.; Gurgenci, T.; Good, P. Phase IIb Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Escalating, Double-Blind Study of Cannabidiol Oil for the Relief of Symptoms in Advanced Cancer (MedCan1-CBD). J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.R.; Greer, R.M.; Pelecanos, A.M.; Huggett, G.E.; Kearney, A.M.; Gurgenci, T.H.; Good, P.D. Medicinal Cannabis for Symptom Control in Advanced Cancer: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomised Clinical Trial of 1:1 Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, M.; Choo, T.-H.; Tiersten, A.; Levin, F.R.; Grassetti, A.; DeSilva, N.; Arout, C.A.; Martinez, D. Oral Cannabis for Taxane-Induced Neuropathy: A Pilot Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2025, 10, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocis, P.T.; Wadrose, S.; Wakefield, R.L.; Ahmed, A.; Calle, R.; Gajjar, R.; Vrana, K.E. CANNabinoid Drug Interaction Review (CANN-DIRTM). Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2023, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.J.Y.; Goh, C.; Leong, C.S.A.; Ng, K.Y.; Bakhtiar, A. Evaluation of Potential Drug-Drug Interactions with Medical Cannabis. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e13812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nader, F.D.; Lopes, L.P.N.; Ramos-Silva, A.; Matheus, M.E. Evidence of Potential Drug Interactions Between Cannabidiol and Other Drugs: A Scoping Review to Guide Pharmaceutical Care. Planta Med. 2025, 91, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffrey, A.L.; Pollack, S.F.; Bruno, P.L.; Thiele, E.A. Drug-Drug Interaction between Clobazam and Cannabidiol in Children with Refractory Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2015, 56, 1246–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Patel, A.D.; Thiele, E.A.; Wong, M.H.; Appleton, R.; Harden, C.L.; Greenwood, S.; Morrison, G.; Sommerville, K. Randomized, Dose-Ranging Safety Trial of Cannabidiol in Dravet Syndrome. Neurology 2018, 90, e1204–e1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, P.; Elsohly, M.; Hill, K.P. Cannabidiol Interactions with Medications, Illicit Substances, and Alcohol: A Comprehensive Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, S.; Bardhi, K.; Prasad, B.; Lazarus, P. Evaluation of the Drug-Drug Interaction Potential of Cannabidiol Against UGT2B7-Mediated Morphine Metabolism Using Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.G.; China, M.; Cláudio, M.; Capinha, M.; Torres, R.; Oliveira, S.; Fortuna, A. Drug–Cannabinoid Interactions in Selected Therapeutics for Symptoms Associated with Epilepsy, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Cancer, Multiple Sclerosis, and Pain. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | Type of study | Administered compounds and dosage | Subjects | Time | Endpoint/outcomes | Results | Reference |

| DS |

multinational, randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind trial | CBD 20 mg/kg/day or placebo, in addition to standard antiepileptic treatment | 120 children and young adults | 4-week baseline period, a 14-week treatment period (2 weeks of dose escalation and 12 weeks of dose maintenance), a 10-day taper period, and a 4-week safety follow-up period | change in convulsive-seizure frequency over a 14-week treatment period, as compared with a 4-week baseline period | positive |

[20] |

| LGS |

randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 20 mg/kg oral CBD daily or matched placebo | 171 patients receiving CBD (n=86) or placebo (n=85) | 14 weeks | percentage change from baseline in the monthly frequency of drop seizures during the treatment period | positive | [21] |

| LGS | double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | CBD 10 mg/kg, 20 mg/kg bw or placebo | 293 patients were assessed; 68 were excluded | 4-week baseline period + 14-week treatment period (2 weeks of dose escalation, followed by 12 weeks of stable dosing + a tapering period of up to 10 days + a 4-week safety follow-up period |

The primary outcome was the percentage change from baseline in the frequency of drop seizures (average per 28 days). |

positive | [22] |

| Drug-resistant focal epilepsy | randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter clinical trial | 195 mg (approximately 2.6 mg/kg) or 390 mg (approximately 5.3 mg/kg) transdermal CBD or placebo; twice daily | 188 patients (85 M; 103 F), 18-70 years old | 12 weeks | least squares mean difference in the log-transformed total seizure frequency per 28-day period, adjusted to a common baseline log seizure rate, during the 12-week treatment period | negative | [23] |

| LGS | open-label extension trial | Epidiolex (100 mg/mL), titrated from 2.5 to 20 mg/kg/day; addition to existing AEDs. | treatment was ongoing in 299 patients, 2-55 years old, 54% M; 46% F; 208 patients had completed 48 weeks of treatment | Median treatment duration was 263 days (38 weeks; range 3-430 days), | to evaluate the long-term safety and tolerability of adjunctive CBD treatment | positive | [24] |

| Drug-resistant epilepsy | prospective, open-label cohort study | CBDl as an adjunct anti-epileptic drug, titrated to a maximum of 25 mg/kg/day | 22 boys and 18 girls were enrolled; their mean age was 8.4 years (median, 8.5 years; range, 1.6-16.6 years; 36 completed 12 weeks’ therapy | 12 weeks | evaluation tolerability and safety of CBD for treating drug-resistant epilepsy in children, and to describe adverse events associated with such treatment | positive | [25] |

| MS spasticity | Randomized controlled trial |

Sativex® (cannabis based medicine - CBM); subjects were instructed to titrate their daily dose steadily as required over 2 weeks, to a maximum of 48 sprays per day | 189 subjects were randomized (124 to CBM, and 65 to placebo); subjects over 18 years of age; 75 M, 114 F | 6 weeks | change from baseline in the severity of spasticity based on a daily diary assessment by the subject on a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS) | positive | [26] |

| MS spasticity | a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial |

Sativex®; patients up-titrated the dosage of THC:CBD spray to a maximum of 12 sprays/day or placebo |

≥18 yo; Phase B: 109 patients; for placebo (n = 46), THC:CBD spray (n = 48) |

12 weeks phase B | ≥ 30% improvement of the numerical rating scale (NRS) of spasticity |

positive |

[27] |

| MS spasticity | phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial |

Nabiximols; 2 treatment periods. Treatment periods consisted of a 14-day dose titration phase, in which patients were advised to titrate their dose beginning with 1 spray/day to an individually optimized dose, up to a maximum of 12 sprays/day | 68 patients | 21 + 21 days | change in velocity-dependent muscle tone as measured by the MAS Lower Limb Muscle Tone-6 from day 1 predose to day 21 (period 1) and from day 31 predose to day 51 (period 2) | the primary endpoint was not met | [28] |

| MS spasticity | Randomized controlled trial, double-blind | Sativex | 189 subjects with definite MS and spasticity | 6 weeks | The change from baseline in the severity of spasticity based on a daily diary assessment by the subject on a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS) | positive | [29] |

| MS spasticity | double-blinded clinical trial | CBD C2 oral drops; initially 5 mg/day, increasing to 70 mg/day over 2 weeks, and 80 mg/day from the third week to the fourth week | 49 MS patients; CBD (n = 24) or a placebo (n = 25); the mean age was 40.65 ± 7.35 years | 8 weeks (4 weeks of treatment and 4 weeks of follow-up) | spasticity reduction measured in T25-FW test | mixed | [30] |

| AD | randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial |

oral capsules of CBD (200 mg) or placebo, starting with one capsule/day and titrated upwards to 3 capsules/day; | patients AD and BPSD; 15 received treatment (n = 8 CBD and n = 7 placebo); mean age of 77.91 years (±8.08) | 6 weeks | the primary endpoints were acceptability, adherence to treatment, and retention rates from baseline to week 6, while secondary outcomes included safety/tolerability and clinical and cognitive measures | according to primary endpoints: positive | [31] |

| AD |

randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled feasibility trial |

Sativex®; The target dose was four sprays/day of nabiximols (10.8-mg THC/10-mg CBD) or placebo, titrated up from one spray per day for the first 3 days to a maximum dose of four sprays/day | 24 ineligible participants (14 to placebo, 15 to nabiximols | 8 weeks (4 weeks of treatment + 4 weeks of observations) | to assess the feasibility and safety of nabiximols as a potential treatment for agitation in AD, defined by meeting four prespecified thresholds for recruitment, retention, adherence, and estimating a minimum effect size (≥0.3) on the Cohen–Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) score at Week 4 | the clinical effect size for CMAI did not reach the desired threshold |

[32] |

| Dementia | randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | “Avidekel,” cannabis oil (30% CBD and 1% THC: 295 mg and 12.5 mg per ml, respectively); 3 times a day | 60 with a diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder and associated behavioral disturbances; mean age, 79.4 years; cannabis oil n=40; placebo n=20 | 16 weeks | decrease, as compared to baseline, of four or more points on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory score by week 16 | positive | [33] |

| PD | double-blind randomized controlled trial | sublingual CBD-enriched product (101.9 mg/ml CBD, 4.8 mg/ml tetrahydrocannabinol [THC]) | Sixty PD patients were randomized into CBD (n = 30) or placebo (n = 30) | 12 weeks | CBD was safe (no adverse effects on motor, cognitive, or affective symptoms), improved Montreal Cognitive Assessment naming scores, but language scores increased in the placebo group but remained unchanged in the CBD group[34] | equivocal | [34] |

| Persons with PD with ≥20 on motor Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale | Randomized Trial | cannabis extract oral sesame oil solution increasing to final dose of 2.5 mg/kg/day | CBD/THC (n = 31) or placebo (n = 30) | 2 weeks | no benefit, worsened cognition and sleep, many mild adverse events, strong placebo response | negative | [35] |

| PD | randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover clinical trial | CBD at a dose of 300 mg | 24 individuals with PD, placebo | two experimental sessions within a 15-day interval | CBD attenuated the anxiety experimentally induced by the Simulated Public Speaking Test | positive | [36] |

| Essential tremor | randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover study | single oral dose of CBD (300 mg) or placebo | 19 patients, 10 males, 9 females, mean 63 years of age | two experimental sessions performed 2-weeks apart | no significant differences in upper limb tremors score, specific motor task tremor scores (writing and drawing/pouring) or clinical impression of change | negative | [37] |

| PD | exploratory double-blind trial | three groups of 7 subjects each, treated with placebo, cannabidiol (CBD) 75 mg/day or CBD 300 mg/day | 21 PD patients without dementia or comorbid psychiatric conditions | no statistically significant differences in general symptoms score, plasma BDNF levels or H1-MRS measures, CBD 300 mg/day had significantly different mean total scores in the well-being and quality of life | positive | [38] | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Randomized and placebo controlled trial | Oil: 250 mg CBD/3 fl. oz | 29 patients with symptomatic peripheral neuropathy: 15 CBD, 14 placebo | 4 weeks | reduction in intense pain, sharp pain, cold and itchy sensations in the CBD group when compared to the placebo group | positive | [39] |

| Chronic low back pain | randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial | VER-01: a standardized full-spectrum extract from the Cannabis sativa L. strain DKJ127, each dose unit (119 µl) contains 50 µl of the extract (2.5 mg THC, 0.1 mg cannabigerol and 0.02 mg CBD, sesame oil as excipient) | 820 participants randomly assigned to VER-01 (n = 394) or placebo (n = 426) | 2-week treatment phase (phase A), a 6-month open-label extension (phase B), followed by either a 6-month continuation (phase C) or randomized withdrawal (phase D) | reduced pain compared to the placebo group; the compound was also well-tolerated with no signs of dependence or withdrawal | positive | [40] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).