Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Implications

2. Introduction

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Modelling

3.2.1. Randomization and Group Formation

3.2.2. Validation and Quality Assurance

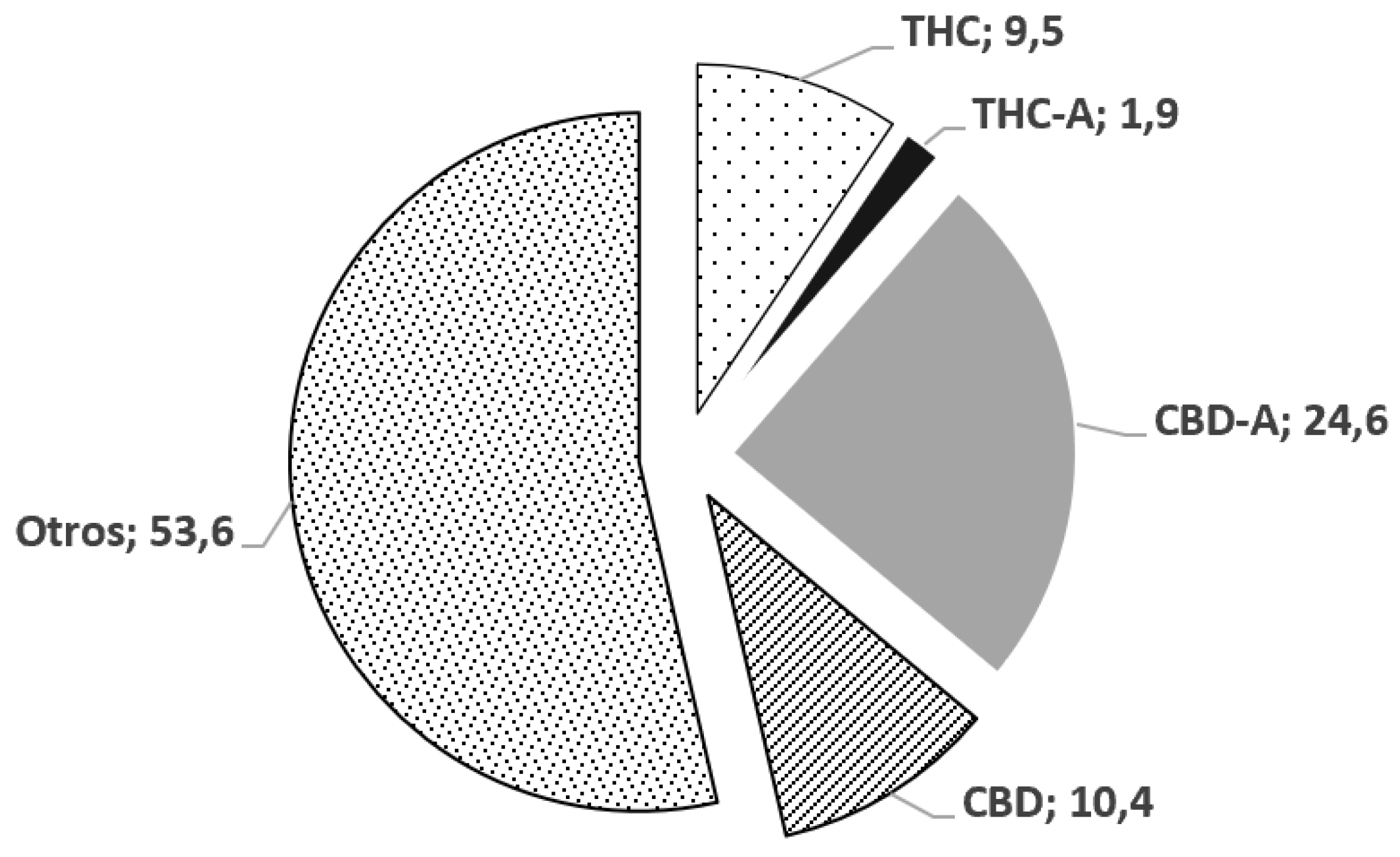

3.3. Analysis of the oily extract of C. sativa.

3.4. Samples

3.5. Drops Concentration and Treatment

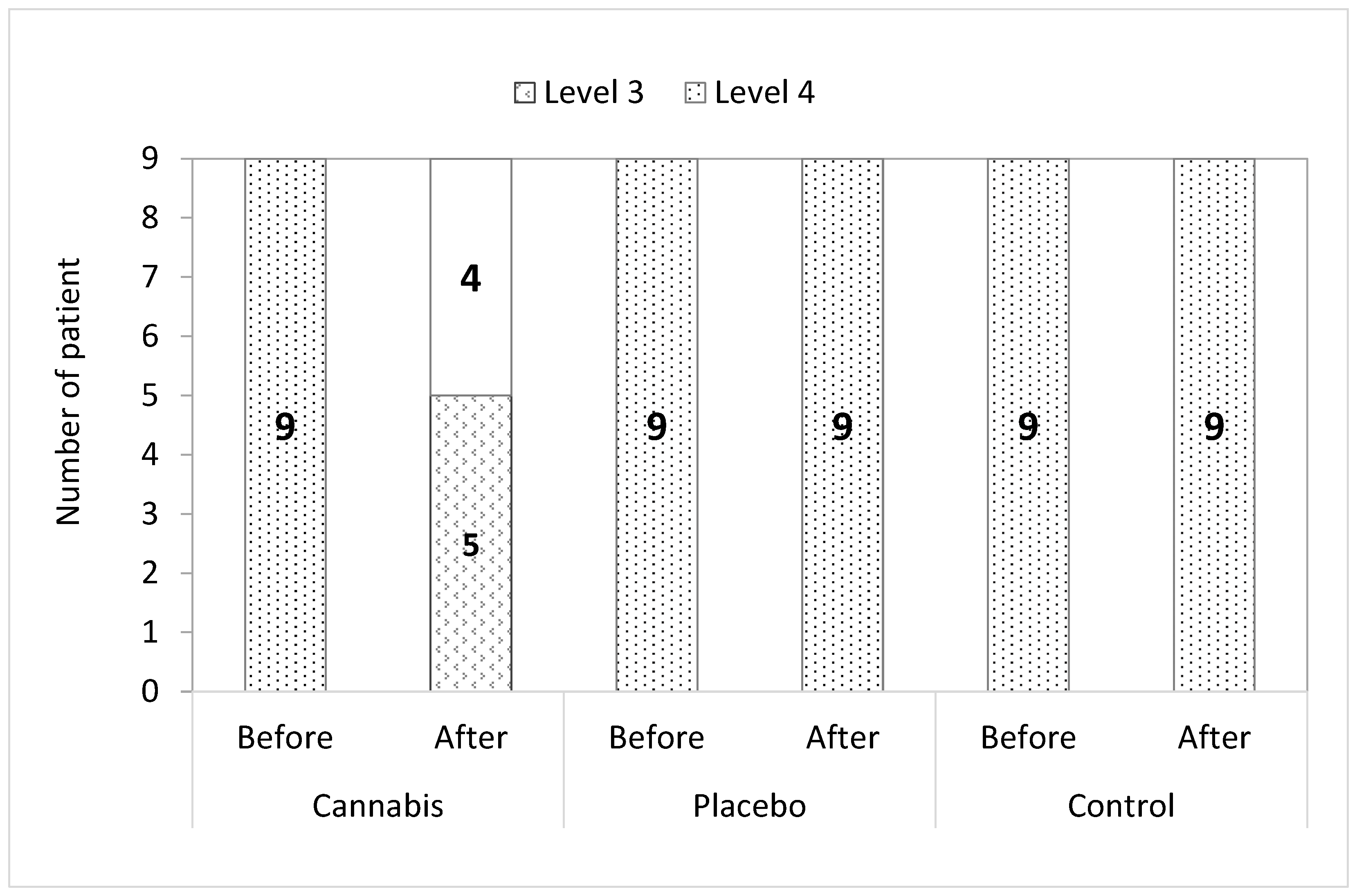

3.6. Pain Assessment and Staging of Pain

3.7. Statistical Analysis of Results

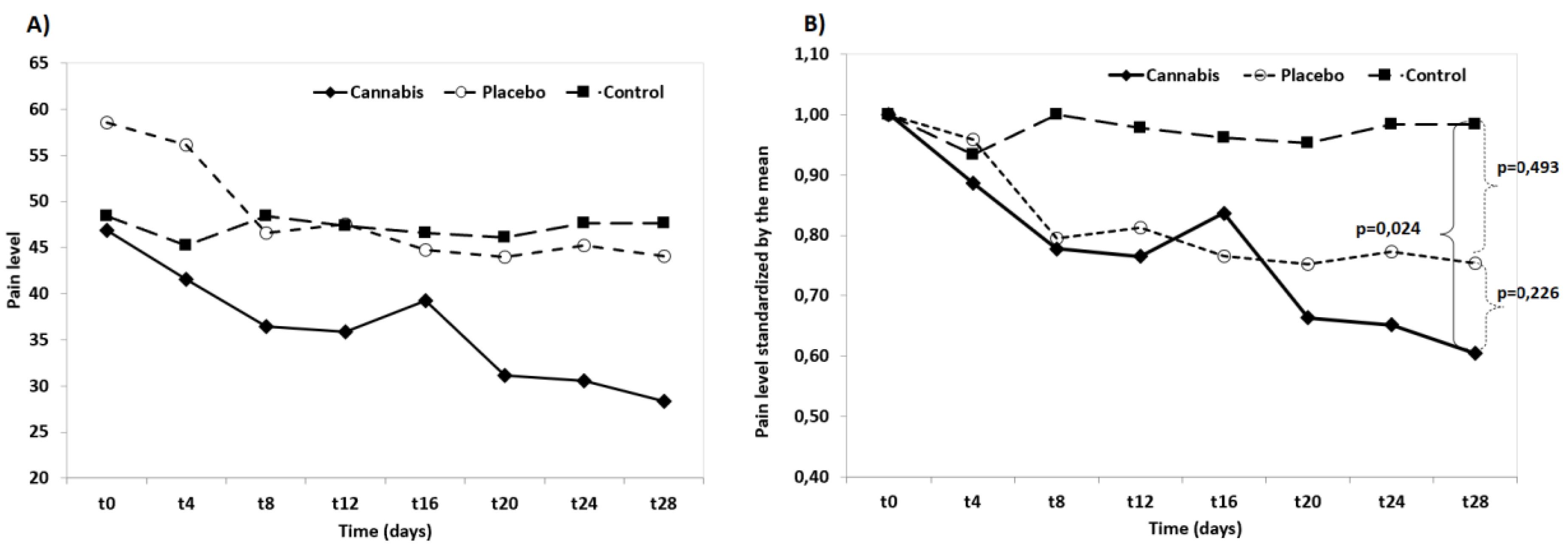

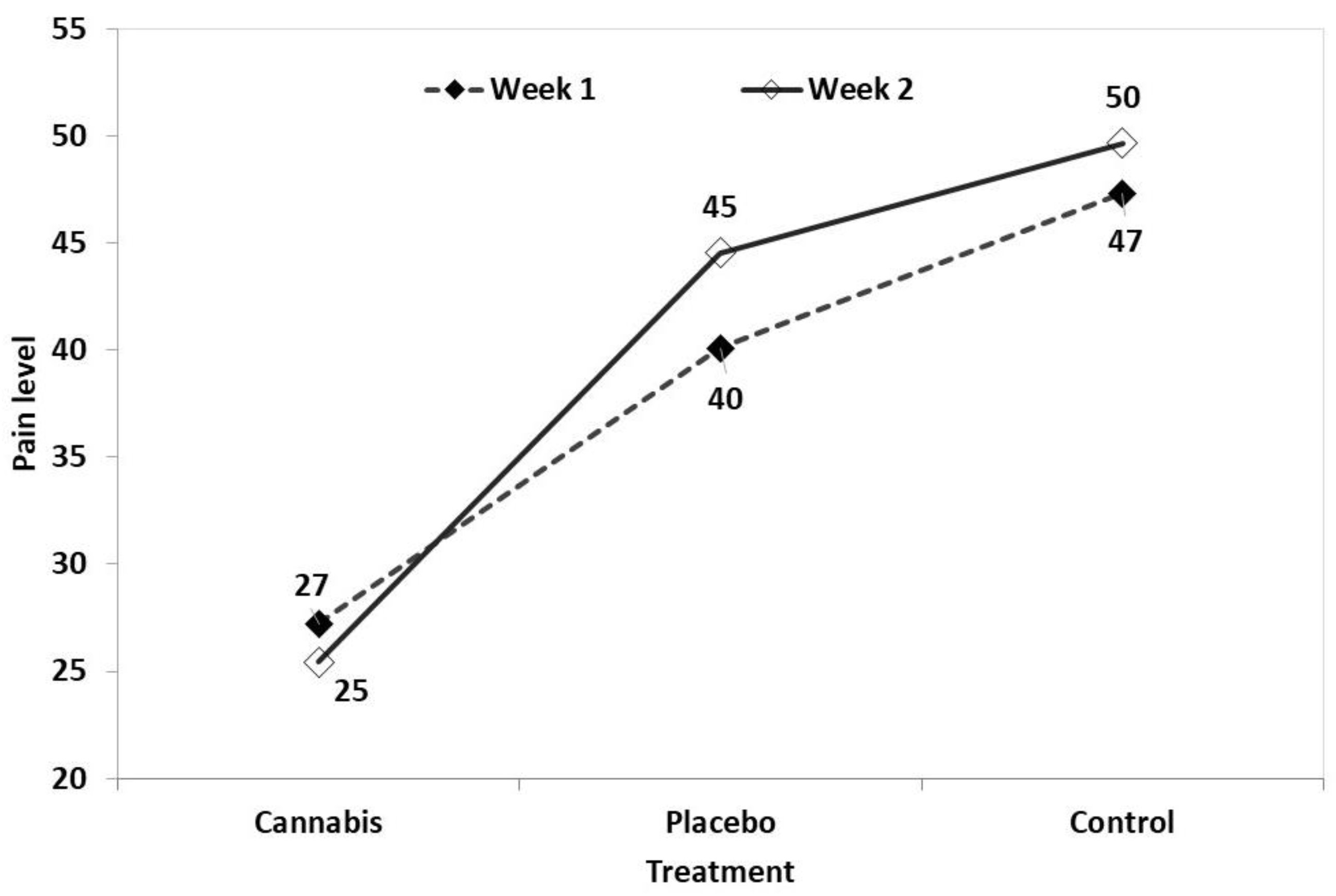

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Financial support statement

Informed Consent Statement

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data and model availability statement:

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Acknowledgements

Data Availability Statement

References

- Brioschi, F. A. , Di Cesare, F., Gioeni, D., Rabbogliatti, V., Ferrari, F., D’urso, E. S., Amari, M., & Ravasio, G. Oral transmucosal cannabidiol oil formulation as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen: Effects on pain relief and quality of life improvement in dogs affected by spontaneous osteoarthritis. Animals 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, C. , Bruniges, N., Peffers, M., & Comerford, E. Advances in the pharmaceutical treatment options for canine osteoarthritis. The Journal of small animal practice 2022, 63, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donvito, G., Nass, S.R., Wilkerson, J.L., Curry, Z.A., Schurman, L.D., Kinsey, S.G. and Lichtman, A. H. The Endogenous Cannabinoid System: A Budding Source of Targets for Treating Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 43, 52–79. [CrossRef]

- Zamith Cunha, R.; Salamanca, G.; Mille, F.; Delprete, C.; Franciosi, C.; Piva, G.; Gramenzi, A.; Chiocchetti, R. Endocannabinoid System Receptors at the Hip and Stifle Joints of Middle-Aged Dogs: A Novel Target for the Therapeutic Use of Cannabis sativa Extract in Canine Arthropathies. Animals 2023, 13, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turcotte, C. , Blanchet, M.R., Laviolette, M., Flamand, N. The CB2 receptor and its role as a regulator of inflammation Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 4449–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, U. , Pacchetti, B., Anand, P., & Sodergren, M. H. Cannabis-based medicines and pain: A review of potential synergistic and entourage effects. Pain management 2021, 11, 395–403. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, E.B. , Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects. Br, J, Pharmacol. 2011, 63, 1344–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rock, E. M. , Limebeer, C. L., & Parker, L. A. Effect of combined doses of Δ (9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) on acute and anticipatory nausea using rat (Sprague- Dawley) models of conditioned gaping. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 4445–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S. , Misawa, K., Yamamoto, I., & Watanabe, K. Cannabidiolic acid as a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory component in cannabis. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2008, 36, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis, L. , Ligresti, A., Moriello, A. S., Allarà, M., Bisogno, T., Petrosino, S., Stott, C. G., & Di Marzo, V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. British journal of pharmacology 2011, 163, 1479–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis, L. , Ligresti, A., Schiano Moriello, A., Lappelli, M., Verde, R., Stott, C. G., Cristino, L., Orlando, P., & Di Marzo, V. Non-THC cannabinoids inhibit prostate carcinoma growth in vitro and in vivo: pro-apoptotic effects and underlying mechanisms. British journal of pharmacology 2013, 168, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S. , Okazaki, H., Ikeda, E., Abe, S., Yoshioka, Y., Watanabe, K., & Aramaki, H. Down-regulation of cyclooxCygenase-2 (COX-2) by cannabidiolic acid in human breast cancer cells. The Journal of toxicological sciences 2014, 39, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klatzkow, S. , Davis, G., Shmalberg, J., Gallastegui, A., Miscioscia, E., Tarricone, J., Elam, L., Johnson, M.D., Leonard, K.M. and Wakshlag, J. J. Evaluation of the efficacy of a cannabidiol and cannabidiolic acid rich hemp extract for pain in dogs following a tibial plateau leveling osteotomy. Front Vet. Sci. 2023, 9, 1036056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Pennsylvania, CBPI https://www.vet.upenn.edu/research/clinical-trials-vcic/our-services/pennchart/cbpi-tool/cbpi-tool-form, from the University of Pennsylvania 2021.

- Brown, D. C. , Boston, R. C., Coyne, J. C., Farrar, J. T. The ability of the Canine Brief Pain Inventory to detect responses to treatment in dogs with osteoarthritis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2008, 233, 1278–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D. C. The Canine Brief Pain Inventory - User Guide. https://www.vet.upenn.edu/research/clinical-trials-vcic/our.Services/pennchart/cbpi-tool, 2018.

- Cachon, T., Frykman, O., Innes, J. F., Lascelles, B., Okumura, M., Sousa, P., Staffieri, F., Steagall, P. V., Van Ryssen, B., & COAST Development Group. Face validity of a proposed tool for staging canine osteoarthritis, 2018: Canine OsteoArthritis Staging Tool (COAST). In: Veterinary journal (London, England:. 1997, 235, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J. , White, K. Pain management in small animal practice, 2019. In: Self I (ed). BSAVA guide to pain management in small animal practice. 1st edn. Gloucester: BSAVA: 24–41.

- Capon, H. (2019). Understanding the pharmaceutical approach to pain management in canine osteoarthritis. Companion animal | April–June 2021, Volume 26 No 6.

- Yeung, T. and Uquillas, E. Does oral cannabidiol oil in adjunct to pain medications help reduce pain and improve locomotion in dogs with osteoarthritis? Veterinary Evidence 2025, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar, D. , Mazus, M., Ion., A., & Koltai, H. Variation in the compositions of cannabinoid and terpenoids in Cannabis sativa derived from inflorescence position along the stem and extraction methods. Industrial Crops & Products 2018, 113, 376–382. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, D. , Kulpa, J. and Paulionis, L. Preliminary Investigation of the Safety of Escalating Cannabinoid Doses in Healthy Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindekamp, N., Weigel, S., Sachse, B., Schäfer, B., Rohn, S., Triesch, N. Comprehensive analysis of 19 cannabinoids in commercial CBD oils: concentrations, profiles, and safety implications. J. Consum. Prot. Food. Saf. 2024, 19, 259–267. [CrossRef]

- Gamble, L.J. , Boesch, J.M., Frye, C.W., Schwark, W.S., Mann, S., Wolfe, L., Brown, Holly., Berthelsen, E.S. & Wakshlag, J.J. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and clinical efficacy of cannabidiol treatment in osteoarthritic dogs. Frontiers in Veterinary Evidence. 2018, 5, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, C.; Rathinasabapathy, T.; Metzger, B.; Dodson, S.; Hanson, D.; Griffiths, J.; Komarnytsky, S. Efficacy and tolerability of full spectrum hemp oil in dogs living with pain in common household settings. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1384168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, M.B. , Deabold, K.A., Talsma, B.N., et al. Serum cannabidiol, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and their native acid derivatives after transdermal application of a low-THC Cannabis sativa extract in beagles. J. vet. Pharmacol. Therap. 2020, 43, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicoine, A. , Illing, K., Vuong, S., Pinto, K.R., Alcorn, J. and Cosford, K. Pharmacokinetic and Safety Evaluation of Various Oral Doses of a Novel 1:20 THC: CBD Cannabis Herbal Extract in Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 583404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, L. , Hellyer, P. & Downing, R. The Use of Cannabidiol-Rich Hemp Oil Extract to Treat Canine Osteoarthritis-Related Pain: A Pilot Study. American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association Journal 2020, 58, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia, S. , Duerr, F.M., Griffenhagen, G. & McGrath, S. Evaluation of the Effect of Cannabidiol on Naturally Occurring Osteoarthritis-Associated Pain: A Pilot Study in Dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 2021, 57, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, C. , Vari, R., Scazzocchio, B., De Sanctis, P., Giovannini, C., D'Archivio, M., & Masella, R. Anti-inflammatory activity of extra virgin olive oil polyphenols: ¿Which role in the prevention and treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases? Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders - Drug Targets 2018, 18, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakshlag, J. J. , Cital, S., Eaton, S. J., Prussin, R., & Hudalla, C. Pharmacokinetics of cannabidiol and cannabidiolic acid in dogs using different delivery methods. Animals 2020, 10, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).