Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Introduction: Surgical site infections (SSIs) and prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) remain among the most serious complications in orthopedic surgery, and chemical debridement is recommended for all septic revisions. The combination of polyhexanide (PHMB) and poloxamer (PLX), with in vitro antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity, represents a promising antiseptic solution. A Delphi consensus to define the indications and clinical applications of PHMB/PLX as an antiseptic solution was carried out. Materials and methods: A steering committee convened a panel of orthopedic surgeons, infectious disease specialists, and wound care specialists with expertise in musculoskeletal infections. A three-phase Delphi process was conducted. Twelve clinical questions and four outcome measures were developed through literature review and iterative discussion. Two Delphi rounds were conducted using a 9-point Likert scale, and statements were rated according to the GRADE method. Results: All 12 final statements achieved strong agreement. The panel identified key patient-related risk factors (smoking, diabetes, obesity, immunosuppression) and procedure-related risks (open fractures, primary/revision arthroplasty, prolonged operative time). Antiseptic irrigation was considered superior to saline, and PHMB-PLX was seen as a helpful addition to mechanical debridement given its antibiofilm activity and good cytocompatibility. Low-pressure irrigation and short exposure times are the preferred application methods, while avoiding use on cartilage or neural tissues. Conclusions: The Delphi panel reached a strong consensus supporting the intraoperative use of PHMB-PLX as a safe and effective antiseptic adjunct for preventing and treating SSIs in orthopedic surgery. The panel recommended conducting high-quality clinical research to verify these findings and improve standardized irrigation protocols.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

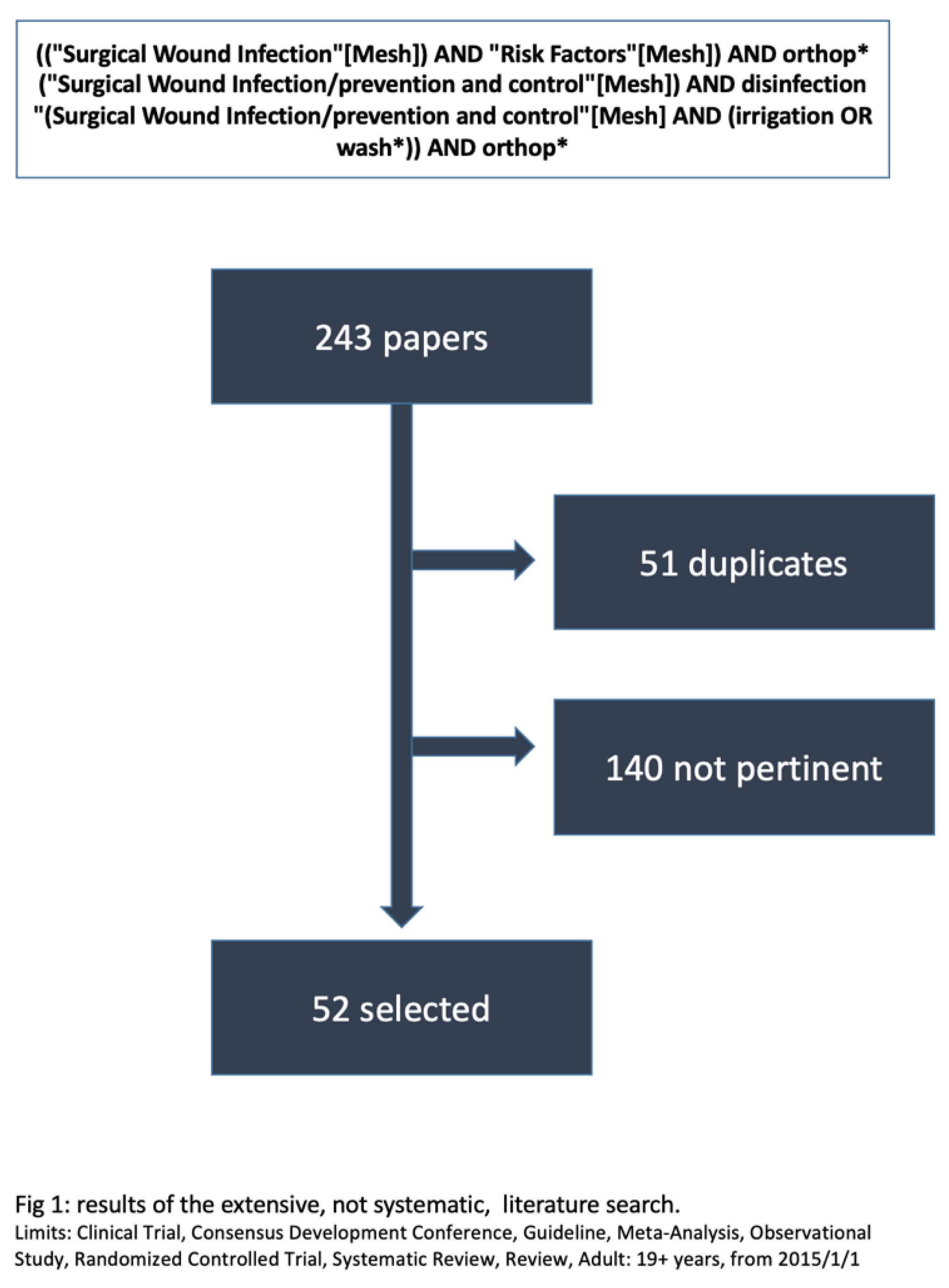

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- ‘Strong agreement’ if the median was ≥8 and the lower end of the IQR was >5

- -

- ‘Weak agreement’ if the median was 6 or 7 and the lower boundary of the IQR was ≥5

- -

- ‘Disagreement’ if the median was less than 5 and the upper boundary of the IQR was less than or equal to 5

- -

- ‘Uncertain’ in the remaining situations (median=5; median >5 but lower quartile <5; median <5 but upper quartile >5)

3. Results

3.1. Risk Stratification

- Evidence Background

- Comments

3.2. Management of Surgical Wounds

- Evidence background

- Comments

3.3. Polyhexanide-Poloxamer in Orthopedic Surgery

- Evidence Background

- Comments

3.4. Pre-and Post-Operative Procedures and Outcomes

- Evidence background

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foux, L; Szwarcensztein, K; Panes, A; Schmidt, A; Herquelot, E; Galvain, T; Phan Thanh, TN. Clinical and economic burden of surgical site infections following selected surgeries in France. PLoS One 2025, 20(6), e0324509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Percival, SL; Emanuel, C; Cutting, KF; Williams, DW. Microbiology of the skin and the role of biofilms in infection. Int Wound J 2012, 9(1), 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, A; Abdo, ZE; Springer, BD; Chen, AF. Pursuit of the ideal antiseptic irrigation solution in the management of periprosthetic joint infections. J Bone Jt Infect. 2021, 6(6), 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honegger, A.L.; Schweizer, T.A.; Achermann, Y.; Bosshard, P.P. Antimicrobial Efficacy of Five Wound Irrigation Solutions in the Biofilm Microenvironment In Vitro and Ex Vivo. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M; Liu, Y; Fang, X; Jiang, Z; Zhang, W; Wang, X. The Effectiveness of Polyhexanide in Treating Wound Infections Due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus: A Prospective Analysis. Infect Drug Resist 2024, 17, 1927–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Watson, F.; Chen, R.; Saint Bezard, J.; Percival, S.L. Comparison of antimicrobial efficacy and therapeutic index properties for common wound cleansing solutions, focusing on solutions containing PHMB. GMS Hygiene and Infection Control 2024, 19, Doc73. [Google Scholar]

- Castiello, G; Caravella, G; Ghizzardi, G; Conte, G; Magon, A; Fiorini, T; Ferraris, L; De Vecchi, S; Calorenne, V; Andronache, AA; Varrica, A; Giamberti, A; Saracino, A; Caruso, R. Impact of Polyhexanide Care Bundle on Surgical Site Infections in Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiac Surgery: A Propensity Score-Matched Retrospective Cohort Study. Int Wound J 2025, 22(6), e70710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Valpiana, P.; Salvi, A.G.; Festini Capello, M.P.; Qordja, F.; Schaller, S.; Kim, J.; Indelli, P.F. Application of Molecular Diagnostics in Periprosthetic Joint Infection Microorganism Identification Following Screening Colonoscopy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, C (Ed.) Medical Technology Assessment Directory: A Pilot Reference to Organizations, Assessments, and Information Resources. In National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Program; Goodman, C (Ed.) National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC), 1988; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218375/.

- McMillan, SS; King, M; Tully, MP. : How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm 2016, 38, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P; Brunnhuber, K; Chalkidou, K; Chalmers, I; Clarke, M; Fenton, M; Forbes, C; Glanville, J; Hicks, NJ; Moody, J; Twaddle, S; Timimi, H; Young, P. How to formulate research recommendations. BMJ 2006, 333, 804–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannotti, F.; Prati, P.; Fidanza, A.; Iorio, R.; Ferretti, A.; Pèrez Prieto, D.; Kort, N.; Violante, B.; Pipino, G.; Schiavone Panni, A.; Hirschmann, M.; Mugnaini, M.; Indelli, P. F. Prevention of Periprosthetic Joint Infection (PJI): A Clinical Practice Protocol in High-Risk Patients. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2020, 5(4), 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H; Xing, H; Zhang, G; Wei, A; Chang, Z. Risk factors for surgical site infections after orthopaedic surgery: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Int Wound J 2025, 22(5), e70068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H; Wang, Y; Xing, H; Chang, Z; Pan, J. Risk factors for deep surgical site infections following orthopedic trauma surgery: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024, 19(1), 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L; Liu, Z; Meng, F; Shen, Y. Smoking and Risk of Surgical Site Infection after Spinal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2017, 18(2), 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaboli Mahdiabadi, M; Farhadi, B; Shahroudi, P; Mohammadi, M; Omrani, A; Mohammadi, M; Hekmati Pour, N; Hojjati, H; Najafi, M; Majd Teimoori, Z; Farzan, R; Salehi, R. Prevalence of surgical site infection and risk factors in patients after knee surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J 2024, 21(2), e14765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Zheng, QJ; Wang, S; Zeng, SX; Zhang, YP; Bai, XJ; Hou, TY. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased risk of surgical site infections: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Infect Control 2015, 43(8), 810–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, AH; Tetsworth, K. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline Summary: Prevention of Surgical Site Infection After Major Extremity Trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2023, 31(1), e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onggo, JR; Onggo, JD; de Steiger, R; Hau, R. Greater risks of complications, infections, and revisions in the obese versus non-obese total hip arthroplasty population of 2,190,824 patients: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2020, 28(1), 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indelli, PF; Iannotti, F; Ferretti, A; Valtanen, R; Prati, P; Pérez Prieto, D; Kort, NP; Violante, B; Tandogan, NR; Schiavone Panni, A; Pipino, G; Hirschmann, MT. Recommendations for periprosthetic joint infections (PJI) prevention: the European Knee Associates (EKA)-International Committee American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (AAHKS)-Arthroplasty Society in Asia (ASIA) survey of members. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022, 30(12), 3932–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, H; Indelli, PF; Ricciardi, B; Kim, TY; Homma, Y; Kigera, J; Veloso Duran, M; Khan, T. What Are the Absolute Contraindications for Elective Total Knee or Hip Arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty;Epub 2025, 40(2S1), S45–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, R; Haurin, K; Saxena, A; DiSantis, KI. The impact of nutritional status on surgical site infection rates among total joint arthroplasty patients: A systematic review. Am J Infect Control 2025, 53(11), 1228–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y; Chen, W. Association between malnutrition status and total joint arthroplasty periprosthetic joint infection and surgical site infection: a systematic review meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024, 19(1), 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J; Isler, M; Barry, J; Mottard, S. Major wound complication risk factors following soft tissue sarcoma resection. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014, 40(12), 1671–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, S; Hozumi, T; Yamakawa, K; Goto, T; Kondo, T. Risk factors for surgical site infection after posterior fixation surgery and intraoperative radiotherapy for spinal metastases. Eur Spine J 2016, 25(4), 1034–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morii, T; Ogura, K; Sato, K; Kawai, A. Incidence and risk of surgical site infection/periprosthetic joint infection in tumor endoprosthesis-data from the nationwide bone tumor registry in Japan. J Orthop Sci. 2024, 29(4), 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmiston, CE, Jr.; Chitnis, AS; Lerner, J; Folly, E; Holy, CE; Leaper, D. Impact of patient comorbidities on surgical site infection within 90 days of primary and revision joint (hip and knee) replacement. Am J Infect Control 2019, 47(10), 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D; Liang, GH; Pan, JK; Zeng, LF; Luo, MH; Huang, HT; Han, YH; Lin, FZ; Xu, NJ; Yang, WY; Liu, J. Risk factors for postoperative surgical site infections after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2023, 57(2), 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, MS; Choi, CH; Yoon, HK; Yoo, JH; Oh, HC; Lee, JH; Park, SH. Risk factors of postoperative complications following total knee arthroplasty in Korea: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100(48), e28052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liukkonen, R; Honkanen, M; Skyttä, E; Eskelinen, A; Karppelin, M; Reito, A. Clinical Outcomes After Revision Hip Arthroplasty due to Prosthetic Joint Infection-A Single-Center Study of 369 Hips at a High-Volume Center With a Minimum of One Year Follow-Up. J Arthroplasty 2024, 39(3), 806–812.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanroy, R; Gubbels, S; Møller, JK; Overgaard, S; Varnum, C. Risk of second revision and mortality following first-time revision due to prosthetic joint infection after primary total hip arthroplasty: results on 1,669 patients from the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2024, 95, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H; Chen, BP; Soleas, IM; Ferko, NC; Cameron, CG; Hinoul, P. Prolonged Operative Duration Increases Risk of Surgical Site Infections: A Systematic Review. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2017, 18(6), 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Randelli, PS; Merghani, K; Atilla, B; Efimov, D; El Hadj, LA; DE Garín, Z; Lustig, S; Mahajan, R; Marazzi, FC; Menon, A; Nikolaev, N; Pokharel, B; Romanini, E; Sheth, NP; Tsiridis, E; Wu, M; Wimmer, MD. 2025 ICM: Surgical Procedure Time. J Arthroplasty Epub ahead of print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, L.P. Bone and Joint Infection in Immunocompromised Patients. In Bone and Joint Infections; Ruggieri, P., Parwani, R., Emara, K.M., Angelini, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, J; Mortazavi, SMJ; Indelli, PF; Rele, S; Haasper, C; Yildiz, F; Holland, CT; Lizcano, JD; Auñón-Rubio, Á; Tai, DBG; Allende, B; Alvand, A; Arias, C; Arshi, A; Artyukh, V; Babis, GC; Baeza-Oliete, J; Budhiparama, N; Buttacavoli, F; Carvalho, PI; Vilchez Cavazos, FC; Chen, CF; Chodór, P; Choong, PFM; Çiloglu, O; Dewar, D; Díaz, FJ; Dikmen, G; Ebied, A; Esmaeili, S; Evans, JT; Falotico, G; Foguet, P; Franceschini, M; Gold, P; Gómez-Barrena, E; Gómez-Junyent, J; Gould, D; Hammad, AA; Han, HS; Hipfl, C; Hunter, C; Incesoy, MA; Kaplan, NB; Karaytug, K; Li, H; Linares, FA; Manrique-Succar, J; Marín-Peña, O; McCarroll, P; McCulloch, R; Mihalič, R; Morata, L; Mortazavi, SA; Nandi, S; Naufal, E; Palacios, JC; Martinez Pastor, JC; Petheram, T; Ritter, A; Rolfson, O; Ros, JM; Sanchez, M; Sancho, I; Shah, JD; Sheng, P; Soriano, A; Spangehl, MJ; Stambough, JB; Tarabichi, S; Taupin, D; Thiengwittayaporn, S; Tözün, IR; Trebše, R; Tsai, SW; Tuncay, I; Veltman, ES; Vilchez-Cavazos, F; Westberg, M; Wu, H; Yates, PJ; Yilmaz, MK; Yoo, JH. 2025 ICM: Debridement, Antibiotics, and Implant Retention. J Arthroplasty Epub ahead of print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, E; Ji, B; Dietz, MJ; Hoveidaei, AH; Zahar, A; Mu, W; Shahi, A; Bozhkova, SA; Abolghasemian, M; Angad, C; Baeza-Oliete, J; Bedard, NA; Bernaus, M; Brown, SA; Brown, TS; Bucsi, L; Campbell, D; Cao, L; Cashman, J; Çiloğlu, O; Citak, M; Costantini, J; Davis, JS; De Meo, D; Ebied, A; Elhence, A; Evans, JT; Fraval, A; Glehr, M; Gold, P; Marcelino Gomes, LS; Goosen, J; Herndon, C; Hilton, TL; Horváth, BL; Kinov, PS; Kolur, S; Kramer, CD; Kuiper, JWP; Kupczik, F; Lange, J; Lastinger, A; Li, Y; Llobet, F; Malhorta, R; Mosalamiaghili, S; Nace, J; Otero, JE; Preobrazhensky, PM; Qin, Y; Ratkowski, J; Rupp, M; Sanchez, JI; Sousa, R; Sződy, R; Taghavi, SP; Taupin, D; Tevell, S; Tortia, R; Vahedi, H; Vasily, A; Veltman, E; Wang, WW. 2025 ICM: One-Stage Exchange. J Arthroplasty 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhence, A; Böhler, C; Kolhoff, F; Fraval, A; Sharma, RK; Belden, K; Aggarwal, VK; Amanatullah, D; Ascione, T; Atilla, B; Bozhkova, SA; Daniliyants, A; De Meo, F; Del Pozo, JL; Fernando, L; Fink, B; Gancher, E; Gould, D; Henry, MW; Hess, B; Jamal, A; Jennings, JM; Lieberman, J; Mahajan, R; Meek, D; Murillo, O; Murylev, V; Neufeld, M; Odgaard, A; Pietsch, M; Powell, J; Pupaibool, J; Rajgopal, A; Rajnish, RK; Roberto, R; Sekar, P; Seon, JK; Shah, JD; Straub, J; Talevski, D; Taupin, DH; Tay, D; Vinayak, U; Yamada, K; Young, B. 2025 ICM: Two-Stage Epub ahead of print. J Arthroplasty 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klasan, A; Dworschak, P; Heyse, TJ; Malcherczyk, D; Peterlein, CD; Schüttler, KF; Lahner, M; El-Zayat, BF. Transfusions increase complications and infections after hip and knee arthroplasty: An analysis of 2760 cases. Technol Health Care 2018, 26(5), 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC National and State Healthcare-Associated Infections Progress Report. April 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthcare-associatedinfections/php/data/progressreport.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/portal/progressreport.html#cdc_report_pub_study_section_2-2022-hai-progress-report.

- Yang, Q; Sun, J; Yang, Z; Rastogi, S; Liu, YF; Zhao, BB. Evaluation of the efficacy of chlorhexidine-alcohol vs. aqueous/alcoholic iodine solutions for the prevention of surgical site infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2024, 110(11), 7353–7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, RG; Burr, NE; McCauley, G; Bourke, G; Efthimiou, O. The Comparative Efficacy of Chlorhexidine Gluconate and Povidone-iodine Antiseptics for the Prevention of Infection in Clean Surgery: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2021, 274(6), e481–e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y; Xu, K; Hou, W; Yang, Z; Xu, P. Preoperative chlorhexidine reduces the incidence of surgical site infections in total knee and hip arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2017, 39, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, B; Herlyn, PKE; Mittlmeier, T; Herlyn, A. Preoperative skin antisepsis using chlorhexidine may reduce surgical wound infections in lower limb trauma surgery when compared to povidone-iodine - a prospective randomized trial. Am J Infect Control 2020, 48(2), 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanish, SJ; Kirwan, MJ; Hou, N; Coble, TJ; Mihalko, WM; Holland, CT. Surgical Site Preparation Using Alcohol with Chlorhexidine Compared with Povidone Iodine with Chlorhexidine Results in Similar Rate of Infection After Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty. Antibiotics (Basel) 2025, 14(2), 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenen, H; et al. Incisional Wound Irrigation for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. JAMA Surg 2024, 159(7), 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, H; Norman, G; Welton, NJ; Crosbie, EJ; Blazeby, J; Dumville, JC. Intra-Cavity Lavage and Wound Irrigation for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2021, 22(2), 144–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerci, OF; Yapar, A; Dogruoz, F; Selcuk, H; Kose, O. Preventive strategies to reduce the rate of periprosthetic infections in total joint arthroplasty; a comprehensive review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2024, 144(12), 5131–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra-Farfán, E; Najafi, F; Hamidreza, Y; Randelli, PS; Albelooshi, A; Alenezi, H; Burgo, FJ; Devito, FS; Ekhtiari, S; Federica, R; Garceau, S; Goswami, K; Guerra-Perez, J; Hakan, K; Iannotti, F; Inoue, D; Kimura, O; Kramer, TS; Lizarraga, M; Lustig, S; Menon, A; Minte, JE; Mohsen, KA; Norambuena, GA; Oussedik, S; Pokharel, B; Slullitel, P; Smailys, A; Spak, RT; Volodymyr, F; Walter, R; Wang, Q; Yirong, Z. 2025 ICM: Surgical Site Irrigation. J Arthroplasty 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seta, JF; Weaver, MJ; Hallstrom, BR; Zheng, HT; Larese, DM; Dailey, EA; Markel, DC. Intraoperative Irrigation and Topical Antibiotic Use Fail to Reduce Early Periprosthetic Joint Infection Rates: A Michigan Arthroplasty Registry Collaborative Quality Initiative Study. J Arthroplasty 2025, 40(8S1), S297–S303.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, B.; Brożyna, M.; Karoluk, M.; Frankiewicz, M.; Migdał, P.; Szustakiewicz, K.; Matys, T.; Wiater, A.; Junka, A. In vitro and in vivo translational insights into the intraoperative use of antiseptics and lavage solutions against microorganisms causing orthopedic infections. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(23), 12720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honegger, A.L.; Schweizer, T.A.; Achermann, Y.; Bosshard, P.P. Antimicrobial Efficacy of Five Wound Irrigation Solutions in the Periprosthetic Joint Infection Microenvironment In Vitro and Ex Vivo. Antibiotics 2025, 14(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koburger, T; Hübner, NO; Braun, M; Siebert, J; Kramer, A. Standardized comparison of antiseptic efficacy of triclosan, PVP-iodine, octenidine dihydrochloride, polyhexanide and chlorhexidine digluconate. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010, 65(8), 1712–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rippon, MG; Rogers, AA; Ousey, K. Polyhexamethylene biguanide and its antimicrobial role in wound healing: a narrative review. J Wound Care 2023, 32(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, T; Wolcott, RD; Peghetti, A; Leaper, D; Cutting, K; Polignano, R; Rosa Rita, Z; Moscatelli, A; Greco, A; Romanelli, M; Pancani, S; Bellingeri, A; Ruggeri, V; Postacchini, L; Tedesco, S; Manfredi, L; Camerlingo, M; Rowan, S; Gabrielli, A; Pomponio, G. Recommendations for the management of biofilm: a consensus document. J Wound Care 2016, 25(6), 305–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, T; Ekhtiari, S; Mundi, R; Citak, M; Sancheti, PK; Guerra-Farfan, E; Schemitsch, E; Bhandari, M. The Effect of Irrigation Fluid on Periprosthetic Joint Infection in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2020, 12(4), e7813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seidelman, JL; Mantyh, CR; Anderson, DJ. Surgical Site Infection Prevention: A Review. JAMA 2023, 329(3), 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accessible on National Guideline System website (PNLG) at the address. Available online: https://siot.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/LG-366-SIOT-Prevenzione-delle-infezioni-in-chirurgia-ortopedica.pdf.

- Zhu, Z; Tung, TH; Su, Y; Li, Y; Luo, H. Intrawound vancomycin powder for prevention of surgical site infections in primary joint arthroplasty: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int J Surg 2025, 111(5), 3508–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, MJ; Choe, H; Abedi, AA; Austin, MS; Bingham, J; Bouji, N; Clyburn, TA; Hieda, Y; Lizcano, JD; Lora-Tamayo, J; Maruo, A; Nishitani, K; Parvizi, J; Ratkowski, J; Rolfson, O; Saleh, UH; Slullitel, P; Trobos, M; Varnasseri, M. 2025 ICM: Antibiotics Usage Criteria. J Arthroplasty Epub ahead of print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surgical Site Infection Event. NHSN. Jan 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf.

- Wildeman, P; Rolfson, O; Wretenberg, P; Nåtman, J; Gordon, M; Söderquist, B; Lindgren, V. Effect of a national infection control programme in Sweden on prosthetic joint infection incidence following primary total hip arthroplasty: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2024, 14(4), e076576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| # | Statement | Median | IQ25% | % Strong agreement | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk stratification | |||||

| 1 | Current smoking and non-compensated diabetes are the major risk factors for SSI. Other relevant risk factors are: BMI >35 kg/m2, malnutrition, immunosuppression, previous irradiation of the surgical site, previous infection involving the site of intervention, history of relapsing soft tissues infections and intra-articular therapy in the three months prior the surgery |

8 | 8 | 100 | SA |

| 2 | Should be considered at high-risk for SSI the procedures performed on:

|

9 | 8 | 100 | SA |

| 3 | Need to perform surgery under urgent or emergency conditions, large surgical wound site, prolonged duration of surgery further increase the risk of SSI | 8 | 8 | 87.5 | SA |

| 4 | In patients who underwent orthopedic surgery the definition of surgical site infection can be derived from the criteria provided by CDC | 9 | 8 | 100 | SA |

| Management of surgical wound | |||||

| 5 | In all patients, regardless of intrinsic risk level associated to patient-related of intervention-related factors, preoperative skin antisepsis using alcoholic CHX solution is recommended | 8.5 | 8 | 100 | SA |

| 6 | Surgical wound irrigation with antiseptic solution is preferable to irrigation with saline or no-irrigation in all the interventions at increased risk of infection | 8 | 7 | 62.5 | SA |

| 7 | The use of antibiotic solutions for surgical wound irrigation should be discouraged due to the increased risk of inducing antibiotic resistance | 9 | 8 | 100 | SA |

| 8 | In all patients, especially in cases where at least one risk factor related to the patient or the type of surgery is present, the use of polyhexanide-poloxamer for surgical wound irrigation should be considered | 8 | 7 | 62.5 | SA |

| 9 | In high-risk orthopedic surgery, especially in cases where the surgery is conducted on infected territories, the use of Polyhexanide-poloxamer for surgical wound irrigation is recommended | 8 | 7.75 | 75 | SA |

| 10 | When polyhexanide-poloxamer is used to irrigate surgical wounds: -it is recommended to use a solution volume sufficient to completely fill the surgical site - to use a low pressure is preferable, particularly in traumatic surgery - the minimum suggested contact time is 1 minute when the intervention is performed on sterile territories and 3 minutes when the intervention is performed on infected territories |

8 | 7 | 62.5 | SA |

| Pre-operative procedures | |||||

| 11 | Panel recommendations for pre-operative procedures in all patients:

|

8 | 8 | 87.5 | SA |

| Post-operative procedures | |||||

| 12 | Panel recommendations for post-operative procedures in all patients:

|

8 | 7.75 | 87.5 | SA |

| Outcomes, primary | |||||

| A | Appearance of clinical signs of infection at the intervention site within 90 days (early infection) or 2 years (prosthetic joints late infections) from the surgery | 8 | 8 | 87.5 | Critical |

| Other Outcomes | |||||

| B | Appearance of systemic signs of infection* within 90 days from the intervention *(Fever, C-reactive protein elevation) |

8 | 7.25 | 75 | SA |

| C | Prolongation of hospital stay and/or need of systemic antibiotic therapy | 8 | 8.75 | 87.5 | SA |

| D | Need of re-intervention within 90 days | 8 | 7.75 | 97.5 | SA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).