1. Introduction

The history of medicine is a multidisciplinary field that explores how human societies have experienced, defined, and attempted to treat disease over time. It integrates discoveries from the natural sciences with the cultural, social, ethical, and political dimensions of medicine. To study the history of healing is not merely to describe past practices, but to understand how yesterday’s discoveries shaped today’s knowledge and how they will continue to shape the medicine of the future (Patel & Desai, 2014).

Like all sciences, medicine has not developed along a linear trajectory; rather, it has been profoundly shaped by sociological, cultural, and political forces. Wars, migrations, epidemics, and shifts in diet and lifestyle have consistently redirected the course of medical knowledge (Amzat & Razum, 2014; Shok & Sergeeva, 2016). Hematology offers one of the clearest examples of this non-linear progress, with pivotal advances often arising from wartime innovations or unexpected scientific breakthroughs.

The present study makes a distinctive contribution by situating multiple myeloma not only within its clinical trajectory but also within its historical and social contexts. Human societies have been aware of cancer for millennia, yet the recognition of hematological malignancies has been possible for only about two centuries since the blood-bone marrow connection was established. Tracing the evolution of myeloma is therefore more than recounting a disease history; it is to follow the very essence of hematology’s own historical development.

Moreover, myeloma remains incurable. Over the past two centuries, therapeutic strategies from the earliest chemotherapies to modern biologics and cellular therapies have been directly influenced by broader sociopolitical dynamics, including wartime medicine and Cold War competition. For this reason, a history of myeloma must also be a history of therapy itself, revealing how medicine evolves at the intersection of science, society, and politics.

This review aims to provide a multidimensional analysis that goes beyond the clinical record. It traces the historical and sociological roots of multiple myeloma, examines how political and social forces shaped its therapies, and highlights persistent inequalities in access to treatment and their ethical implications. Unlike many accounts that begin with the mid-20th century description of myeloma, this review places the disease within the longer history of medicine. Early ideas about cancer in antiquity, the recognition of blood as a distinct tissue, and the rise of hematology as a scientific field are key to understanding how myeloma entered medical knowledge. The story of myeloma runs parallel to the emergence of hematology, showing how changes in science also reflected broader shifts in how societies understood the body and disease. By following this path from ancient cancer descriptions through the birth of hematology to modern biotechnology this review offers both a historical narrative and a critical view of how war, empire, industrialization, and pandemics shaped cancer research. In this way, the history of myeloma becomes more than the history of a single malignancy; it is also a window into the constant dialogue between medicine and society, where discoveries, crises, and innovations are deeply connected.

2. Brief History and the Ancient Roots of Cancer

Cancer is a multifactorial disease, characterized by uncontrolled cell division, resistance to cell death, the manipulation of its niche, invasion of surrounding tissues, and metastasis to distant compartments (Tomasetti & Vogelstein, 2015). By redirecting its bioenergetic resources entirely toward proliferation and survival, cancer disrupts systems regulating cell division and differentiation, evades immune surveillance, and reprograms its metabolism. It achieves limitless replicative capacity while creating an inflammatory, angiogenic microenvironment that supports tumor growth and invasion (Hanahan, 2022).

Although paleopathologists debate the extent to which cancer has afflicted humanity throughout evolutionary history, compelling evidence demonstrates that it has been a recognizable threat for millennia (Micozzi, 1991). One of the earliest descriptions appears in the Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 3000 BCE), attributed to Imhotep and his students in Ancient Egypt, where breast cancer was described as an “incurable swelling of the breast” (Breasted, 1930). This text also contained the earliest therapeutic recipes, mentioning surgical excision and medicinal compounds (Hajdu, 2016). Across ancient civilizations such as Sumer, Babylon, and China, plant-based preparations were commonly employed, supplemented by minerals (iron, copper, sulfur, arsenic, mercury) and animal-derived substances (Hajdu, 2016). Treatments ranged from herbal teas and oils to metallic pastes applied in advanced cases (Hajdu, 2011).

For nearly 2,500 years, Mesopotamian medicine was characterized by a form of “theocratic healing,” where priest-physicians combined spiritual and medical authority (Retief & Cilliers, 2007). This tradition, continued by Imhotep (c. 2700-2620 BCE), profoundly influenced subsequent civilizations. After his death, his disciples preserved his teachings, and his legacy shaped Egyptian, and later Greek, thought. Indeed, Egyptian medicine and its priest-healer ethos are considered foundational to Greek philosophy and medical systems (Hajdu, 2016). In the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE), cancer was described as incurable and interpreted as a divine curse (Hajdu, 2011).

In Ancient Greece, cancer became closely associated with Hippocrates (460-370 BCE), who introduced the term karkinos (“crab”), likely inspired either by the invasive, claw-like appearance of tumors or by mythological allusion. Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 BCE-50 CE) later translated the term into Latin as cancer, while Galen (130-200 CE) used the word oncos (“swelling”) (Galassi et al., 2024; Di Lonardo, Nasi & Pulciani, 2015). Underpinning Greek medicine was the humoral theory, which posited that disease arose from imbalance among the four bodily fluids-blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. This concept, later systematized by Galen, was endorsed by the Church and persisted for over 1,500 years, framing cancer as a disease of excess black bile (Hajar, 2022).

Knowledge transfer across civilizations occurred through wars, migrations, and trade. The Phoenicians (c. 3000 BCE) played a crucial role as cultural mediators, transmitting ideas between Egypt, Sumer, Assyria, and later Greece (Zalloua et al., 2018). Alexander the Great’s conquests (356-323 BCE) initiated the Hellenistic era, a period of East-West synthesis that shaped science, philosophy, and medicine (Austin, 2006). This knowledge flow, enriched by Greek and Egyptian traditions, established a foundation for continuous medical discourse (Mark, 2023; Teall, 2014).

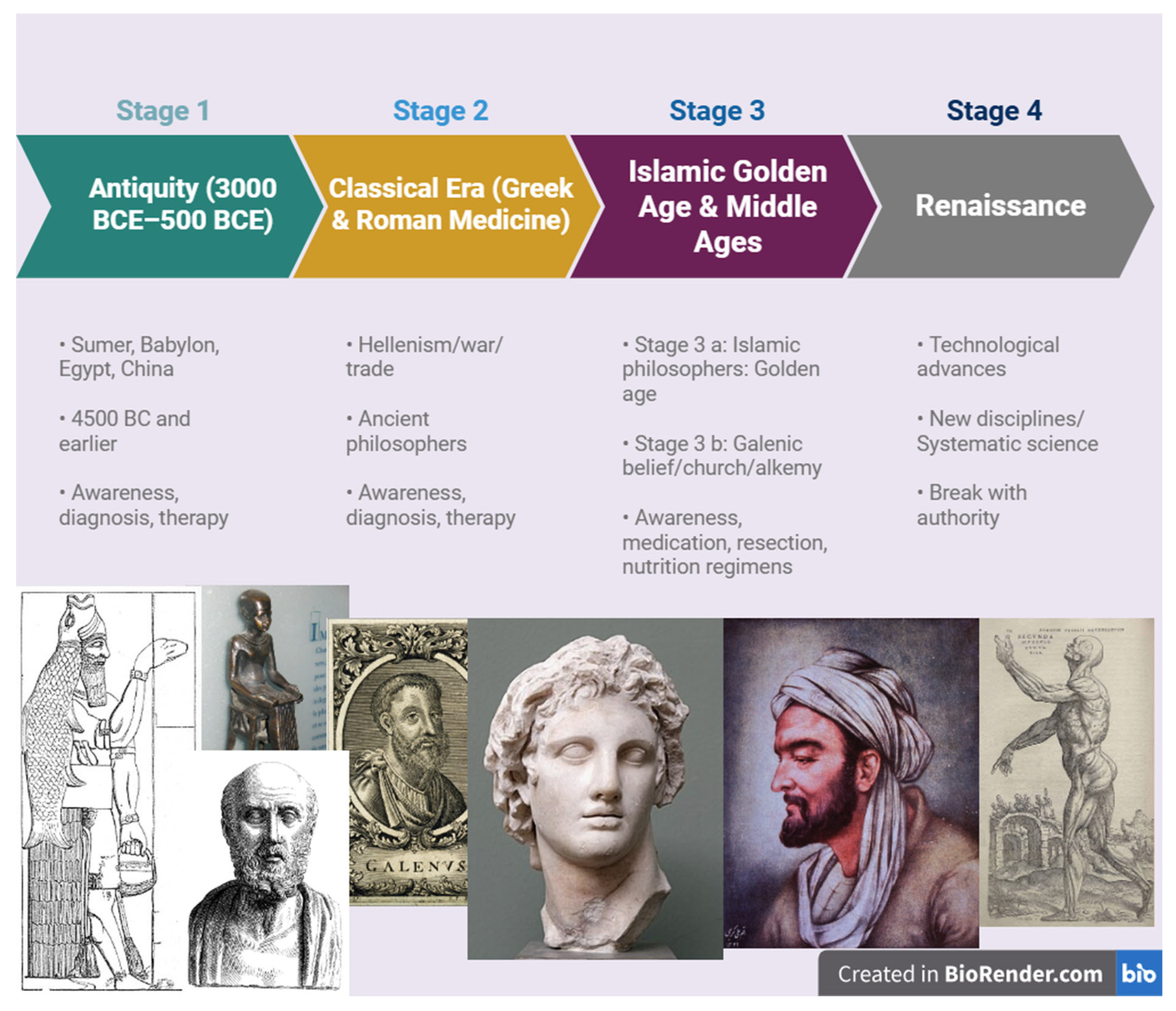

During the Islamic Golden Age, physicians such as Rhazes (865-925), Al Zahrawi (936-1013), and Ibn al-Nafis (1218-1288) integrated Greco-Roman knowledge with their own innovations. Their approaches emphasized dietary therapies, cautious pharmacological interventions, and, in severe cases, surgical excision (Zaid et al., 2011). This intellectual flourishing in Mesopotamia and Anatolia ensured the transmission of medical knowledge eastward and westward for centuries (Biggs, 1969; Kamiat, 1952). Ultimately, with the Renaissance and Reformation, this stream of knowledge reoriented back toward Europe, setting the stage for modern scientific medicine. (see

Figure 1)

3. Renaissance and the Rise of Systematic Science

The Renaissance, which took place in 15th-16th century Europe, was an era of renewal in science, philosophy, art, and architecture. Through the reintroduction of knowledge from Ancient Greece and the Islamic world, this period laid the foundations for many modern scientific disciplines (Tonelli, 2013).

Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), often regarded as the “father of anatomy,” published De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), where he advanced anatomical research beyond Galenic tradition. His cadaveric dissections of blood vessels, circulation, and organ structures provided a basis for the later emergence of hematology (Mesquita, Souza Júnior & Ferreira, 2015).

William Harvey (1578-1657) offered a systematic description of blood circulation in his 1628 treatise Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus. This discovery revolutionized cardiovascular medicine and became a cornerstone for the development of cell theory and the understanding of systemic disease processes, including cancer (Toledo-Pereyra, 2008).

Paracelsus (1493-1541) emphasized the role of minerals in therapy and is credited with the maxim, “All things are poison, and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison.” His recognition that chemical exposures could cause disease anticipated modern immunology, toxicology, pharmacology, and ultimately the conceptual basis for chemotherapy (Michaleas et al., 2021).

Ambroise Paré (1510-1590) contributed significantly to the surgical management of tumors, with early efforts at excision that marked an important step in oncological practice (Hernigou, 2013).

For millennia, blood carried symbolic meanings of lineage, nobility, and identity, and was revered as the essence of life. Yet the recognition that bone marrow serves as the “seedbed” of blood is only a few centuries old. Ancient Greek philosophers such as Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen considered marrow to be a structural support rather than a hematopoietic organ (Cooper, 2011; Tavassoli, 1980). Even in the Islamic Golden Age, physicians like Avicenna, while deeply engaged with anatomy, did not establish a link between marrow and blood (Afhsar, 2011; Strohmaier, 2019). This critical connection remained elusive until the invention of the microscope and the subsequent identification of blood cells, inaugurating a two-hundred-year process that illuminated the role of bone marrow in hematopoiesis (

Table 1).

Following the Renaissance, the dogmatic weight of scholastic thought in Europe began to wane, opening the way for what came to be known in the 16th and 17th centuries as the Scientific Revolution. During this period, experimental observation, mathematical proof, and the systematic measurement of nature became dominant approaches to knowledge. Copernicus’s heliocentric model, Vesalius’s anatomical studies, and Galileo’s experimental methods became symbols of this intellectual transformation. The Scientific Revolution enabled physiology, anatomy, chemistry, and astronomy to emerge as distinct scientific disciplines. In doing so, it laid the intellectual foundation of modern medicine and prepared the ground for the later rise of the pharmaceutical industry (Mokyrj, 2016). The intellectual transformation of the Scientific Revolution was soon followed by broader structural changes, including the rise of colonial enterprises and the Industrial Revolution. These developments reshaped the production of knowledge and resources, laying the groundwork for modern pharmacology. In the twentieth century, the global struggles over oil, the devastation of the World Wars, and the emergence of new research frontiers further accelerated the growth of pharmacology and oncology.

The expansion of European empires in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries reshaped both global trade and the foundations of modern medicine. Colonial powers extracted natural resources such as quinine, opium, and rubber from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, integrating them into European pharmacological practices and industrial production (Porter, 1997). Colonial expansion was also accompanied by the appropriation of Indigenous medicinal knowledge, from which substances such as cinchona bark and coca leaves entered Western pharmacology (Schiebinger, 2004). Yet this transfer occurred in the context of profound demographic collapse and cultural erasure of Native populations, illustrating how medical knowledge advanced in parallel with colonial violence (Crosby, 2003).

At the same time, the discovery of oil in the Middle East and elsewhere transformed not only the global energy system but also the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors. Petroleum-derived compounds became essential for the synthesis of new drugs, the mass production of plastics, and the development of laboratory equipment (Greene & Condrau, 2010). As colonial economies fueled industrial laboratories, pharmaceutical companies grew into global players, increasingly tied to the political and economic structures of empire.

One emblematic example of the entanglement between colonial exploitation and modern medicine is quinine, extracted from the bark of the cinchona tree native to the Andes. Initially introduced to Europe in the seventeenth century through Jesuit missionaries, quinine became indispensable for colonial expansion by protecting European soldiers from malaria in tropical regions. In the nineteenth century, the Dutch established plantations in Java, securing a near-monopoly on global quinine supply (Sneader, 2005). Beyond its colonial role, quinine’s legacy continued in oncology: its synthetic derivatives, such as chloroquine, have been investigated in multiple myeloma as modulators of autophagy (Vogl et al., 2014). This trajectory illustrates how a colonial commodity could evolve into a modern pharmacological tool, linking imperial history with contemporary hematology.

The Industrial Revolution of the 18th century provided the technological and material foundations for modern pharmacology. Mechanization, steam power, and advances in chemical engineering enabled the large-scale synthesis and purification of compounds that had previously been confined to artisanal practices. With the rise of industrial chemistry, laboratories could now produce standardized drugs and explore new chemical entities. At the same time, the economic expansion of industrialized nations fostered the growth of the pharmacy sector. Companies such as Merck, which originated as family-owned apothecaries, expanded into global enterprises during this period, transforming medicines from local remedies into industrial commodities. This convergence of technological innovation and economic growth established the infrastructure for the pharmaceutical industry that would dominate the twentieth century and beyond (Mokyr, 2016; Sneader, 2005).

4. Multiple Myeloma: First Definations (1844-1900)

Multiple Myeloma (MM) (from the Latin myelo, meaning marrow, and the suffix -oma, denoting tumor) is a lymphoproliferative disorder of terminally differentiated plasma cells within the bone marrow. It is the second most common hematological malignancy and predominantly affects elderly patients (Malard et al., 2024).

Over years of progression in the marrow, malignant plasma cells secrete abnormal monoclonal immunoglobulins collectively known as paraproteins. These are variably referred to as “M-protein,” “spike protein,” or “Bence Jones protein.” Despite intensive research, their precise biological function remains unclear; however, their heterogeneity has been increasingly recognized, and they represent important therapeutic targets (Pérez-Escurza et al., 2023).

Diagnosis requires the presence of ≥10% clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow. Clinical manifestations are characterized by the CRAB criteria: C- hypercalcemia, R- renal insufficiency, A- anemia, and B- bone lesions. In addition to CRAB features, disease classification also relies on bone marrow plasma cell burden, the amount of monoclonal immunoglobulin in serum, and serum free light chain (FLC) measurements (Rajkumar, 2024).

Paleopathological evidence suggests that multiple myeloma (MM) has threatened humankind for at least 6,000 years. The earliest known case dates back to the Neolithic period (ca. 4000 BCE), in which a mummy displayed skeletal lesions consistent with MM (Riccomi, Fornaciari & Giuffra, 2019). Despite early awareness of cancer in general, hematological malignancies remained poorly understood for millennia, largely due to the delayed recognition of bone marrow function and its link to blood and related diseases. The delayed recognition of multiple myeloma can also be explained by its clinical overlap with more familiar diseases of earlier centuries. Skeletal fragility and deformities were frequently misattributed to osteoporosis or so-called “bone tuberculosis,” while renal impairment was often regarded as primary kidney disease rather than a systemic malignancy. These diagnostic ambiguities further postponed the clear conceptualization of MM as a distinct hematological disorder.

The first modern clinical descriptions of MM emerged in the mid-19th century. In 1844, Samuel Solly reported the case of a 39 years old woman with multiple fractures involving the radius, tibia, femur, and fibula, noting replacement of spongy bone with red, tumor-like tissue (Solly, 1844). In 1845, the merchant Thomas Alexander McBean was admitted to St. George’s Hospital in London with severe skeletal pain. His urine analysis, performed by Dr. Henry Bence Jones, revealed a precipitating protein after nitric acid addition later termed Bence Jones protein (BJP). This discovery remains a cornerstone in MM diagnosis today. McBean’s case was later documented by William MacIntyre (1850), and Bence Jones himself interpreted the patient’s death as “atrophy due to albuminuria” (Bence, 1848; Rathore, Coward & Woywodt, 2012). At that time, therapy included corsets, leeches, bloodletting, rhubarb, orange peel, opium, and quinine (Kyle & Rajkumar, 2008).

Otto Kahler later published in 1889 what he regarded as the defining features of MM: bone pain, anemia, urinary protein precipitation, and necropsy findings (Kahler, 1889). For this reason, MM was long referred to as Kahler’s disease. Simultaneously, John Dalrymple contributed crucial histopathological observations, describing fragile, porous bones filled with gelatinous connective tissue and inflammatory material (Kyle, 2000). These descriptions remain consistent with modern imaging findings such as low-dose whole-body CT and FDG-PET/MRI (Hameed et al., 2020; Reagan et al., 2015).

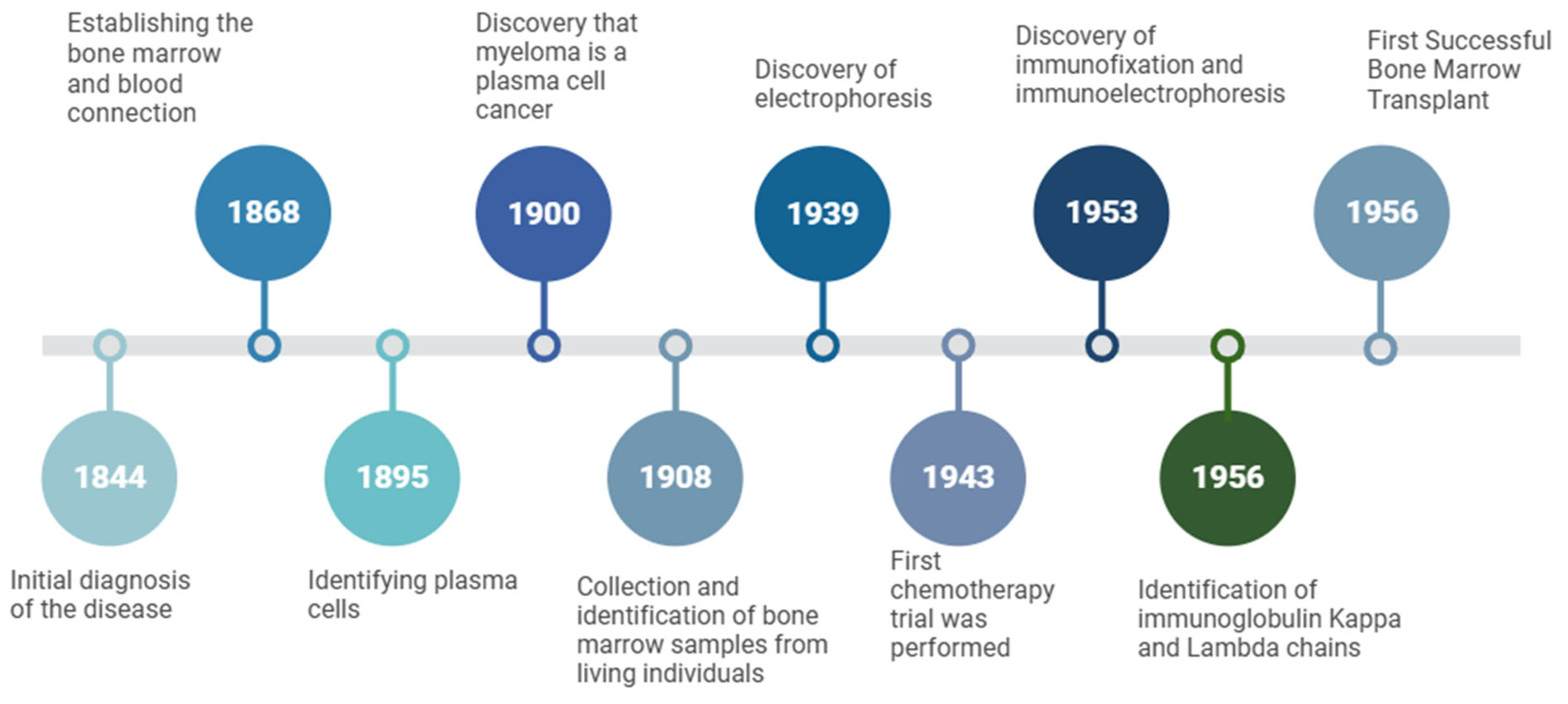

Histological advances further refined the understanding of MM. In 1846, Thomas Watson performed postmortem analysis of McBean’s marrow, identifying large round or oval cells with prominent nucleoli an early description of abnormal plasma cells (Kyle, 2000). In 1868, Franz Neumann established that bone marrow is the site of blood formation and demonstrated that leukemia originated there (Thomas, 2013). In 1895, Hungarian dermatologist Tamas von Marschalkó described cells highly consistent with modern plasma cell morphology (Schuh, Mielenz & Jäck, 2020). Shortly thereafter, James Homer Wright (1900) proposed that MM arises from plasma cells. Finally, Ghedini introduced the use of bone marrow aspiration for cytological analysis (Pizzi et al., 2022), a technique still fundamental in today’s hematology.

5. Myeloma Under the Shadow of Two Wars (1900-1956)

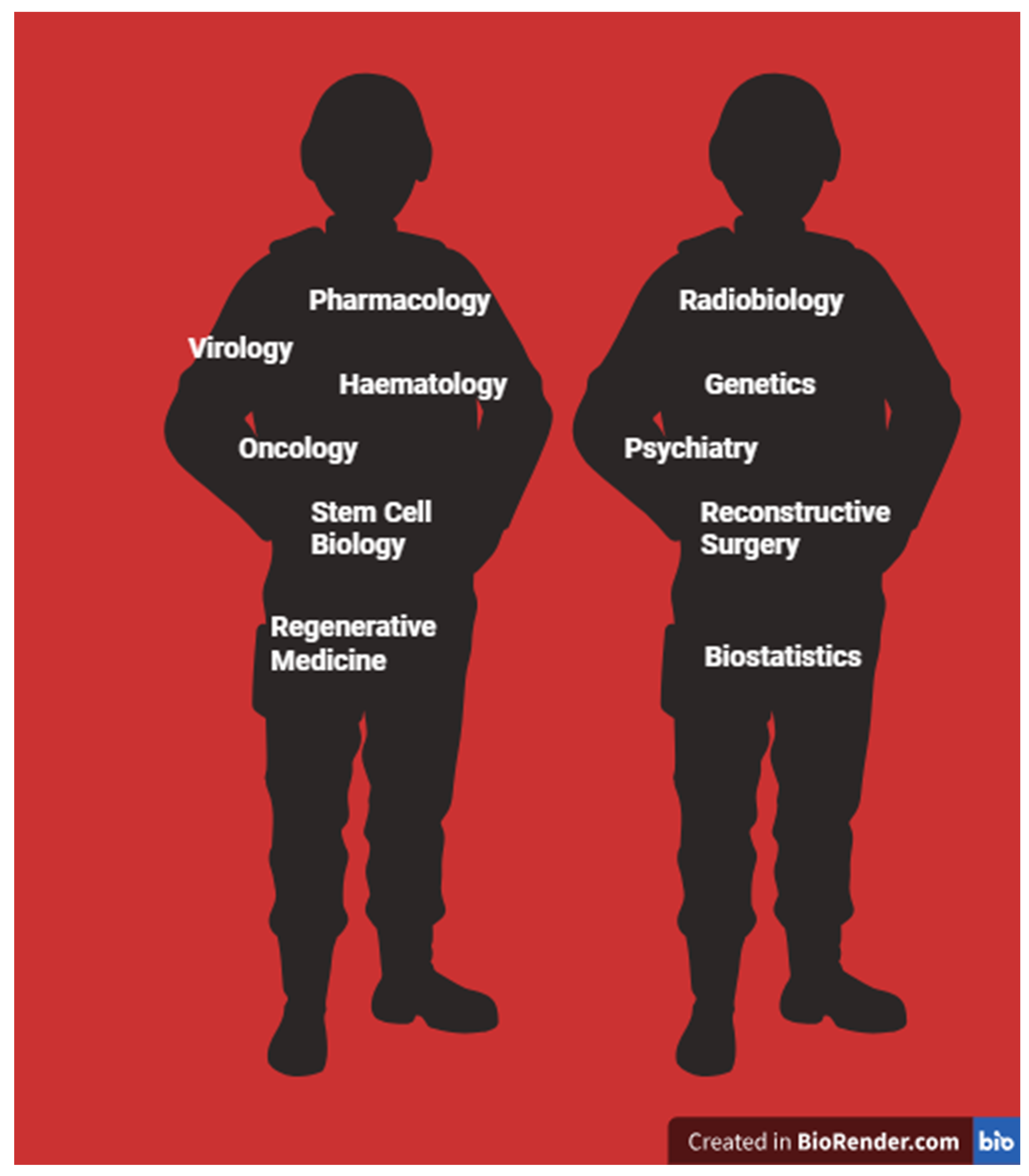

Between the late 19th century and the mid-20th century, hundreds of cases of multiple myeloma (MM) were described. A landmark review by Geschickter and Copeland in 1928 compiled 412 MM cases, providing a pivotal reference for the field (Ribatti, 2018). The first half of the 20th century was characterized by profound scientific revolutions interwoven with the catastrophic effects of two world wars. While war accelerated certain areas of medical progress including the development of chemotherapy, radiation biology, grafting techniques, stem cell research, drug discovery, and antibiotics such as penicillin it also fostered unethical experimentation and the creation of increasingly destructive weapons. Physicians confronted unprecedented pathological presentations among war casualties, yielding invaluable though tragic insights into human physiology. Importantly, the migration of Jewish scientists from Nazi Germany to the United States during World War II further accelerated advances in hematology and immunology. The expansion of the pharmaceutical industry in the post-war period was partly driven by urgent medical needs, but also influenced by ethically questionable human experimentation conducted during wartime (Van Way, 2016) (

Figure 2).

The 1920s and subsequent decades witnessed renewed momentum in cancer research, including hematological malignancies. A defining moment was the observation during World War I that mustard gas caused profound lymphopenia and bone marrow suppression. This toxic effect inspired the use of nitrogen mustard derivatives as the first chemotherapeutic agents, marking the beginning of the chemotherapy era (Krumbhaar & Krumbhaar, 1919; Goodman et al., 1984; Freireich, 1984; Smith, 2017). In Nazi Germany, significant resources were directed to cancer research (Proctor, 1999), and subsequent application of chemotherapeutic agents expanded across cancer types (Goodman & Wintrobe, 1946; Haddow, 1950). Psychological stress, chemical exposure, and wartime mobilization further contributed to the rising incidence and recognition of cancer worldwide (Jester et al., 2024; Ramani & Bennet, 1993). Alongside life-saving discoveries such as penicillin (Gaynes, 2017), the pharmaceutical industry and related sciences expanded often driven by urgent needs or by ethically questionable human and animal experiments (Leaning, 1996; Falzone, Salomone & Libra, 2018).

Key technological breakthroughs in this era included the first use of serum protein electrophoresis in 1939 by Longsworth, which revealed the characteristic “M-spike” (Ramakrishnan & Jialal, 2023). In 1953, Grabar and Williams refined immunoelectrophoresis, enabling detection of small monoclonal light chains otherwise missed by conventional electrophoresis (Grabar & Williams, 1953). Korngold and Lipari (1956) further distinguished κ and λ light chains, a critical advance for MM diagnosis. It was not until 1962 that Edelman and Gally definitively demonstrated the structural identity between Bence Jones proteins and immunoglobulin light chains, confirming their pathological and diagnostic significance (Edelman & Gally, 1962).

Perhaps the most transformative development following World War II was the emergence of

bone marrow transplantation, which dramatically reduced mortality in hematological malignancies and laid the foundation for modern cellular therapy (de la Morena & Gatti, 2010). The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, while devastating beyond measure, highlighted the consequences of marrow aplasia and immunosuppression. In response, efforts intensified to develop grafting techniques, study immune reconstitution, and explore marrow transplantation as a therapeutic strategy (Shimizutani & Yamada, 2021; Weissman & Shizuru, 2008) (see

Figure 3).

Thus, under the shadow of two wars, myeloma research advanced in a paradoxical way driven both by human tragedy and by unprecedented scientific discovery.

Bone marrow transplantation emerged in the postwar era, shaped by both the urgent medical needs and the scientific insights derived from warfare. The recognition of the cytotoxic effects of mustard gas, together with the experience of massive blood loss and traumatic injuries during the World Wars, created new imperatives for research into hematopoiesis and immune function. The development of transplantation was therefore not only a medical innovation but also a historical milestone that transformed the treatment of numerous immunological and hematological disorders.

The invention of the microscope had earlier made blood the first tissue to be systematically examined, enabling the recognition and classification of blood cells (Hajdu, 2003). By the mid-twentieth century, war-related research had accelerated hematology, as scientists identified and described numerous blood cell types (Sabine, 1940). Experimental grafting studies in rodents introduced fundamental immunological concepts such as tolerance and histocompatibility (de la Morena & Gatti, 2010), which laid the intellectual groundwork for bone marrow transplantation. In 1956, the first successful human bone marrow transplant was performed, marking a new era in hematology (Simpson & Dazzi, 2019).

Over the following decades, transplantation techniques evolved alongside advances in immunology and supportive care. By the 1980s, autologous stem cell transplantation had become established as a viable therapeutic approach for hematological malignancies such as multiple myeloma, offering improved survival outcomes and reducing the risks associated with immune rejection. Today, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation continues to represent a milestone in the history of oncology an innovation born from the convergence of wartime research, technological progress, and the expanding ambitions of modern medicine.

6. Cold War Era and the Evolution of Myeloma Therapy

The Cold War period (1947-1991) positioned science not only as a driver of medical progress but also as a strategic tool of national security and ideological competition (Etzkowitz, 1996). Within this climate, research in pharmacology and oncology expanded rapidly, as governments and pharmaceutical companies pursued innovations that could symbolize both scientific leadership and therapeutic progress.

During this era, the first truly systematic approaches to multiple myeloma therapy were introduced. Early attempts with urethane in the late 1940s proved ineffective and even harmful, but they illustrated the era’s urgency in testing new agents (Holland et al., 1966). A breakthrough came in the 1950s with the introduction of alkylating agents such as melphalan, which became a cornerstone of therapy (Blokhin et al., 1958). Around the same time, steroids like prednisone and prednisolone emerged, and their combination with melphalan produced markedly improved outcomes (Alexanian et al., 1969). These regimens defined myeloma treatment for decades.

Other discoveries reflected the dual legacy of scientific progress and ethical failure. Thalidomide, initially marketed in Europe in the 1950s as a safe sedative, was withdrawn after catastrophic teratogenic effects were revealed. Yet decades later it was repurposed as an immunomodulatory agent, opening a new therapeutic class in myeloma treatment (Richardson et al., 2002). Anthracyclines like doxorubicin also entered clinical use, though limited by toxicities (Arcamone et al., 1969).

Technological advances paralleled these pharmacological milestones. The refinement of protein electrophoresis and immunofixation enabled reliable detection of monoclonal proteins, while new classification systems (Durie & Salmon, 1975) and the recognition of precursor conditions such as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) (Kyle & Rajkumar, 2007) provided a conceptual framework that still shapes diagnostic practice today.

Thus, the Cold War era left a complex legacy: it was a time when geopolitical pressures, pharmaceutical ambition, and medical necessity converged to accelerate the development of therapies and diagnostic standards that continue to define multiple myeloma care.

In the present day, the treatment of hematological malignancies has been shaped by the convergence of precision medicine and digital technologies. Artificial intelligence (AI) methods are now being integrated into disease classification, building on nearly two centuries of accumulated clinical, histopathological, and molecular data. These systems hold the potential to assist clinicians in early diagnosis, staging, and treatment planning, offering optimized therapeutic pathways for both patients and healthcare providers (Allegra et al., 2022; Romero et al., 2024).

Targeted therapies represent another transformative development. The discovery of monoclonal antibody technology in the 1970s (Köhler & Milstein, 1975) ultimately enabled the approval of Rituximab in 1997, marking a paradigm shift toward precision approaches in oncology (Pierpont, Limper & Richards, 2018). In multiple myeloma, the identification of CD38 as a critical plasma cell marker (Reinherz et al., 1980) paved the way for the development of Daratumumab, approved in 2015, which remains among the most effective therapies for this disease (van de Donk, Richardson & Malavasi, 2018).

At the same time, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation continued to evolve. Introduced for multiple myeloma in the early 1980s (McElwain & Powles, 1983), autologous transplantation combined with high-dose melphalan conditioning soon became, and continues to remain, a central therapeutic option for eligible patients.

Together, these innovations illustrate how modern medicine has moved from empirical experimentation toward increasingly individualized and technology-driven models of care, reflecting broader societal investments in biotechnology, data science, and global health infrastructure.

7. The Era of Modern Therapies: Pharmacology

By the late twentieth century, chemotherapy, corticosteroids, and stem cell transplantation had become established as the mainstays of multiple myeloma (MM) treatment. However, these approaches were characterized by broad toxicity and only modest survival benefits, leaving a clear need for innovation. The early 2000s marked a turning point with the approval of proteasome inhibitors, beginning with bortezomib in 2003. By targeting what had long been considered a cellular “waste disposal” system, bortezomib reframed fundamental assumptions in biology and introduced a new therapeutic logic: disease could be controlled by regulating intracellular degradation pathways rather than indiscriminately destroying proliferating cells (Adams, 2002). This innovation also reflected a global transition from postwar state-driven research toward a biotechnology-centered pharmaceutical industry, in which scientific discovery was increasingly entangled with industrial competition.

The thalidomide tragedy of the 1960s, remembered as one of the darkest episodes in pharmaceutical history, later evolved into a striking example of how failure can generate progress. Its safer derivative, lenalidomide, reintroduced immunomodulation into the clinic, demonstrating superior efficacy with reduced toxicity (Richardson et al., 2002). This transformation highlighted how regulatory reform and public mistrust, born from past disasters, could foster the conditions for safer and more effective therapies. Other novel drug classes soon followed, including histone deacetylase inhibitors, BCL2 inhibitors, and antibody-drug conjugates, broadening the therapeutic arsenal of the twenty-first century (Rajkumar & Kumar, 2024). Yet despite these innovations, survival in multiple myeloma has remained limited five-year survival hovers around 50% due to drug resistance, cumulative toxicity, and recurrent disease (Costa et al., 2017). This succession of pharmacological innovations, while remarkable in scope, also reflects a persistent paradigm in modern medicine one that equates therapeutic success with the biochemical elimination of disease. Yet the capacity to destroy a tumor, whether through heat, radiation, or cytotoxic agents, does not necessarily translate into healing. In many cases, the treatment itself becomes a source of cumulative harm, reminding us that longevity without restoration cannot be the true measure of cure. Modern therapeutics often promises to kill the tumor but ends up exhausting the person (El-Cheikh et al., 2023; Andritos et al., 2008; Brighten et al., 2018). The true measure of cure should be the restoration of the human being, not merely the elimination of diseased cells.

Beyond biological toxicity, therapeutic harm also emerges from structural inequities. In many health systems, patients are not offered genuine choice but are constrained by cost, policy, or pharmaceutical monopoly. The paradox of modern oncology is that those least able to afford toxicity are often those most exposed to it. Financial constraints, reimbursement policies, and market incentives perpetuate a model in which economic survival dictates biological survival.

What, then, distinguishes these modern therapeutic paradigms from those born in the Cold War era? The same logic of militarization persists: diseases are still “enemies,” patients the “battlefield,” and drugs the “weapons.” In this sense, the biomedical ambition of our time remains haunted by the metaphors of war it once inherited.

8. The Era of Modern Therapies: Antibodies

Building on the success of targeted approaches in lymphoma, monoclonal antibodies were introduced into myeloma therapy, with daratumumab emerging as the most transformative example. Approved in 2015, daratumumab consolidated immunotherapy’s role in MM and symbolized a shift toward precision medicine. Its clinical impact extended beyond biology: patients and physicians began to expect individualized treatments tailored to molecular features rather than standardized regimens. At the same time, these therapies reignited debates about equity and access, as their high costs created stark disparities across socioeconomic groups and between high- and low-income countries. Thus, while daratumumab illustrated the promise of personalized medicine, it also exposed the gap between technological sophistication and the realities of everyday clinical practice, where melphalan and other older regimens remain widely used.

The success of monoclonal antibodies in lymphoma encouraged their extension into plasma cell malignancies. Among these, daratumumab, targeting the CD38 antigen highly expressed on myeloma cells, became the first widely adopted antibody therapy (Salteralla et al., 2020). Its approval in 2015 consolidated the role of immunotherapy in myeloma and marked a symbolic shift toward precision medicine. Drugs such as daratumumab illustrated the transition from “one-size-fits-all” treatments to biologically tailored regimens, reflecting a cultural moment when patients began to expect individualized care. At the same time, these advances sparked debates about equity, as the high costs of novel agents limited access across socioeconomic and national boundaries. While daratumumab represented progress, genuine personalization in myeloma remains incomplete. Current practice still relies heavily on older, highly toxic regimens such as melphalan, revealing the gap between technological innovation and routine care. A truly personalized approach would require integrating biological, psychological, social, and systemic dimensions. Genomic and molecular data provide critical insights, but outcomes are also shaped by the microbiome, environmental exposures, lifestyle, psychological resilience, socioeconomic status, cultural beliefs, and the structural realities of health systems. Moreover, individual preferences and values ultimately frame what patients perceive as meaningful care. Taken together, the rise of monoclonal antibodies illustrates that personalization is not merely a technological ambition but a holistic paradigm one that demands the integration of both measurable biological data and the lived realities of patients (Lourenço et al., 2022) (see

Figure 4).

In this sense, medicine may need to look backward to move forward. In antiquity, Egyptian, Greek, and Islamic physicians treated illness not as an isolated lesion but as a disturbance of the whole person. Therapies were adjusted to temperament, environment, and the patient’s concurrent conditions; mild remedies, diet, and emotional wellness formed the foundations of care. Avicenna, writing in the Canon of Medicine, described cancer and other chronic diseases as disorders of wellness (mizan al-nafs), emphasizing that healing required the restoration of mental and bodily harmony. In this framework, Avicenna emerges not as a moralist but as a rational empiricist whose observations anticipated psychosomatic medicine by nearly a millennium. His notion of mizan al-nafs-the balance of the self-was not a matter of faith or virtue but of physiology and perception. Disease, in his view, arose when this equilibrium between body and mind was disturbed. Far from superstition, his writings reveal an early recognition that emotion, environment, and bodily state are inseparable dimensions of health (Avicenna, The Canon of Medicine, 1025/1999). The modern ideal of personalized medicine, if it is to be truly humane, must rediscover these ancient roots where cure was inseparable from emotion, equilibrium, and ethical care.

9. The Era of Modern Therapies: CAR-T Therapy

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents one of the most transformative advances in hematologic oncology. For patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma often after years of cumulative toxicity and bone-marrow exhaustion CAR-T therapy has redefined what remission can mean. Despite being used at advanced disease stages, recent trials report median overall survival approaching 60 months in selected cohorts (Goel et al., 2025). Unlike conventional regimens requiring continuous intravenous therapy and chronic pharmacologic exposure, CAR-T therapy is typically a single-infusion treatment whose main risks occur within the first few weeks and are increasingly well-managed. The therapy does not demand endless hospital stays, daily injections, or lifelong medication; instead, it allows a period of genuine physiological recovery. For many patients, this represents not only extended survival but a restoration of autonomy and dignity an experience closer to healing than to mere disease control.

After decades of immunological experimentation, CAR-T received FDA approval in 2017, marking both a scientific milestone and a fragile re-establishment of public trust in gene therapy (Eshhar et al., 1993; Kalos et al., 2011). In MM, anti-BCMA CAR-T therapies such as ide-cel and cilta-cel have produced unprecedented outcomes, with survival exceeding 56 months in some cases and substantial quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gains (Keesari et al., 2025;Goel et al., 2025). Yet, in real-world practice, CAR-T is often applied only in late-line settings after patients have undergone multiple cycles of chemotherapy and immunomodulators, a delay that considerably limits its therapeutic impact. Recent cost-effectiveness analyses in related hematologic malignancies highlight that “immediate CAR-T” in earlier treatment lines yields superior outcomes compared to late application, both in survival and in QALY gains (Yamamoto et al., 2025). Moreover, access is limited to a handful of countries, leaving the majority of patients worldwide excluded from these advances. CAR-T therefore represents both the height of modern innovation and the persistence of structural inequality a therapy capable of mobilizing the patient’s immune system, yet confined to a privileged minority (Rasche et al., 2024; Swan et al., 2024; Ailawadhi et al., 2024).

From an ethical and economic standpoint, CAR-T cell therapy represents both the pinnacle of modern biomedical achievement and a mirror reflecting persistent inequities in global health. In multiple myeloma, it arguably constitutes the most effective therapy developed to date. Yet its availability remains confined to a few countries and to patients who can afford its substantial upfront cost. This situation raises a profound ethical dilemma: while the single-infusion cost of CAR-T appears prohibitive, the cumulative expense of years of chemotherapy, hospitalizations, and supportive care often exceeds it several-fold. In this sense, CAR-T may be “expensive” only in appearance but, in reality, offers a more sustainable and humane therapeutic model. Wider access through public funding, insurance inclusion, and global manufacturing support is essential to transform it from an innovation for the privileged few into a right of care for all. Ultimately, the promise of CAR-T lies not only in engineering the immune system to fight cancer but in re-engineering medicine itself toward fairness, accessibility, and human restoration.

The most recent disruption in the progress of myeloma therapy and one that profoundly affected patient care was the COVID-19 pandemic. During this period, patients often faced severe barriers to accessing necessary treatments, as hospitals prioritized emergency care and clinical research was temporarily halted.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with multiple myeloma already immunocompromised faced disproportionately high risks of severe infection and mortality (Chari et al., 2020). Lockdowns and overwhelmed health systems disrupted care continuity, while oncology trials, including those on CAR-T cells, were delayed, exposing the fragility of global research infrastructures (Upadhaya et al., 2020). From a biomedical perspective, the pandemic accelerated the convergence of immunology and virology within cancer medicine: the management of cytokine release syndrome in COVID-19 paralleled, and even informed, approaches to CAR-T-related toxicities (Lee et al., 2014; Fajgenbaum and June, 2020). Yet on a societal level, the inequities in vaccine distribution mirrored those already seen in CAR-T access, underscoring that scientific innovation cannot realize its potential without equitable implementation (Bollyky and Bown, 2020).

Taken together, the modern era of myeloma therapy demonstrates that biomedical discovery and social context are inseparable. Advances such as bortezomib, daratumumab, and CAR-T cells not only extended survival but also reshaped cultural expectations of medicine, while simultaneously revealing enduring structural inequities in global health. The trajectory of modern therapeutics is therefore not merely a chronicle of pharmacological progress but a reminder that innovation without social responsibility risks reproducing new forms of exclusion.

Discussion

The history of multiple myeloma, traced from ancient references to cancer through the birth of hematology and into the molecular era, illustrates how medical knowledge evolves alongside broader social and cultural change. Early descriptions of malignancies in antiquity reveal that cancer was understood not only as a biological affliction but also as a metaphor for imbalance and decay. The invention of the microscope in the seventeenth century transformed these symbolic notions into anatomical and cellular realities, making blood the first tissue systematically studied and ultimately enabling the recognition of plasma cell dyscrasias.

As medicine entered the industrial and modern scientific revolutions, progress in myeloma care became increasingly linked to political and economic forces. The rise of industrial chemistry, the exploitation of colonial resources, and the pharmaceutical industry’s expansion provided the tools and infrastructures for modern drug development. Wars and geopolitical competition accelerated hematology and oncology, producing both devastating tragedies, such as thalidomide, and major breakthroughs, such as the introduction of melphalan. These dynamics reveal a recurring theme: crises and conflicts catalyze discovery, but the benefits and harms are unevenly distributed.

In the contemporary era, therapies such as proteasome inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and CAR-T cells represent the culmination of centuries of experimentation and technological innovation. Yet the persistence of disparities in cost, accessibility, and equity echoes older patterns of exclusion. The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced these lessons, showing both the remarkable speed of biomedical innovation and the fragility of health systems in delivering it equitably. Thus, multiple myeloma provides a lens to examine the entanglement of science, society, and ethics across centuries of medical history.

Conclusions

Today, CAR-T therapy stands as the most emblematic achievement in myeloma care, offering survival gains once deemed unimaginable and redefining the boundaries of what biomedical science can accomplish. For the first time, treatment no longer relies solely on pharmacological toxicity but mobilizes the patient’s own immune system as a living drug demonstrating that when nature’s intrinsic mechanisms are harnessed through human ingenuity, the most powerful medicines can emerge.

Yet this achievement is shadowed by deep inequities that are not purely financial. CAR-T remains accessible only in selected regions, limited not by individual wealth alone but by the uneven global infrastructure of health systems, restrictive regulatory frameworks, and corporate monopolies that control manufacturing and distribution. In many countries, patients are excluded not because of personal poverty but because the therapy is simply unavailable or unsupported within national health policies. In this sense, CAR-T embodies both the promise and the paradox of modern medicine: it demonstrates humanity’s capacity to harness biology for therapeutic gain while exposing the structural injustices that determine who benefits from innovation.

True progress in multiple myeloma will therefore depend not only on future discoveries but on embedding equity, ethics, and social responsibility at the very core of medical innovation. Scientific breakthroughs alone cannot define success; success must also be measured by inclusivity, accessibility, and the capacity to narrow rather than widen global health disparities. The story of myeloma, culminating in the rise of CAR-T therapy, is thus not merely a medical history but a mirror reflecting humanity’s enduring struggles with knowledge, power, and justice.

References

- Adams, J. Development of the Proteasome Inhibitor PS-341. The Oncologist 2002, 7(1), 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshar, A. Concepts of Orthopedic Disorders in Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine. Archives of Iranian Medicine 2011, 14(2), 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ailawadhi, S.; Shune, L.; Wong, S. W.; Lin, Y.; Patel, K.; Jagannath, S. Optimizing the CAR T-Cell Therapy Experience in Multiple Myeloma: Clinical Pearls from an Expert Roundtable. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia 2024, 24(5), e217–e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexanian, R.; Haut, A.; Khan, A. U.; Lane, M.; McKelvey, E. M.; Migliore, P. J.; Stuckey, W. J., Jr.; Wilson, H. E. Treatment for Multiple Myeloma: Combination Chemotherapy with Different Melphalan Dose Regimens. JAMA 1969, 208(9), 1680–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegra, A.; Tonacci, A.; Sciaccotta, R.; Genovese, S.; Musolino, C.; Pioggia, G.; Gangemi, S. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Applications in Multiple Myeloma Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment Selection. Cancers 2022, 14(3), 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amzat, J.; Razum, O. Sociology and Health. In Medical Sociology in Africa; Amzat, J., Razum, O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2014; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andritsos, L. A.; Johnson, A. J.; Lozanski, G.; Blum, W.; Kefauver, C.; Awan, F.; Smith, L. L.; et al. Higher Doses of Lenalidomide Are Associated with Unacceptable Toxicity Including Life-Threatening Tumor Flare in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008, 26(15), 2519–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcamone, F.; Cassinelli, G.; Fantini, G.; Grein, A.; Orezzi, P.; Pol, C.; Spalla, C. Adriamycin (14-Hydroxydaunomycin), a New Antitumor Antibiotic from S. peucetius var. caesius. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 1969, 11(6), 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M. M. The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest: A Selection of Ancient Sources in Translation., 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Avicenna (Ibn Sina). 1999. The Canon of Medicine. Translated by O. Cameron Gruner. Chicago: Great Books of the Islamic World. Originally published ca. 1025.

- Baskett, T. F. James Blundell: The First Transfusion of Human Blood. Resuscitation 2002, 52(3), 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bence, H. J. On a New Substance Occurring in the Urine of a Patient with Mollities Ossium. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 1848, 138, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, R. Medicine in Ancient Mesopotamia. History of Science 1969, 8(1), 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhin, N.; Larionov, L.; Perevodchikova, N.; Chebotareva, L.; Merkulova, N. Clinical Experiences with Sarcolysin in Neoplastic Diseases. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1958, 68(3), 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollyky, T. J.; Bown, C. P. The Tragedy of Vaccine Nationalism. Foreign Affairs 2020, 99(5), 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Breasted, J. H. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: In Facsimile and Hieroglyphic Transliteration with Translation and Commentary.; University of Chicago, Oriental Institute Publications: Chicago, 1930; 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Bringhen, S.; Offidani, M.; Palmieri, S.; Pisani, F.; Rizzi, R.; Spada, S.; Evangelista, A.; et al. Early Mortality in Myeloma Patients Treated with First-Generation Novel Agents Thalidomide, Lenalidomide, Bortezomib at Diagnosis: A Pooled Analysis. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2018, 130, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chari, A.; Samur, M. K.; Martinez-Lopez, J.; Cook, G.; Biran, N.; Yong, K.; et al. Clinical Features Associated with COVID-19 Outcome in Multiple Myeloma: First Results from the International Myeloma Society Data Set. Blood 2020, 136(3), 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coller, B. S. Blood at 70: Its Roots in the History of Hematology and Its Birth. Blood 2015, 126(24), 2548–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B. The Origins of Bone Marrow as the Seedbed of Our Blood: From Antiquity to the Time of Osler. Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center) 2011, 24(2), 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L. J.; Brill, I. K.; Omel, J.; Godby, K.; Kumar, S. K.; Brown, E. E. Recent Trends in Multiple Myeloma Incidence and Survival by Age, Race, and Ethnicity in the United States. Blood Advances 2017, 1(4), 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, A. W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492.; Praeger: Westport, CT, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De la Morena, M. T.; Gatti, R. A. A History of Bone Marrow Transplantation. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America 2010, 30(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lonardo, A.; Nasi, S.; Pulciani, S. Cancer: We Should Not Forget the Past. Journal of Cancer 2015, 6(1), 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, D. William Hewson (1739–1774): The Father of Haematology. British Journal of Haematology 2006, 133(4), 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durie, B. G. M.; Salmon, S. E. A Clinical Staging System for Multiple Myeloma: Correlation of Measured Myeloma Cell Mass with Presenting Clinical Features, Response to Treatment, and Survival. Cancer 1975, 36(3), 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duverney, M. Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences.; Chez Pierre Mortier: Amsterdam, 1700. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, G. M.; Gally, J. A. The Nature of Bence-Jones Proteins: Chemical Similarities to Polypeptide Chains of Myeloma Globulins and Normal Gamma-Globulins. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 1962, 116(2), 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Cheikh, J.; Moukalled, N.; Malard, F.; et al. Cardiac Toxicities in Multiple Myeloma: An Updated and a Deeper Look into the Effect of Different Medications and Novel Therapies. Blood Cancer Journal 2023, 13, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshhar, Z.; Waks, T.; Gross, G.; Schindler, D. G. Specific Activation and Targeting of Cytotoxic Lymphocytes through Chimeric Single Chains Consisting of Antibody-Binding Domains and the Gamma or Zeta Subunits of the Immunoglobulin and T-Cell Receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1993, 90(2), 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H. Losing Our Bearings: The Science Policy Crisis in Post–Cold War Eastern Europe, Former Soviet Union and USA. Science and Public Policy 1996, 23(1), 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajgenbaum, D. C.; June, C. H. Cytokine Storm. The New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383(23), 2255–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falzone, L.; Salomone, S.; Libra, M. Evolution of Cancer Pharmacological Treatments at the Turn of the Third Millennium. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2018, 9, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freireich, E. Nitrogen Mustard Therapy. JAMA 1984, 251(17), 2262–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, F. M.; Varotto, E.; Vaccarezza, M.; Martini, M.; Papa, V. A Historical and Palaeopathological Perspective on Cancer. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene 2024, 65(1), E93–E97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaynes, R. The Discovery of Penicillin—New Insights after More than 75 Years of Clinical Use. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2017, 23(5), 849–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, U.; Zanwar, S.; Cowan, A. J.; Banerjee, R.; Khouri, J.; Dima, D. Ciltacabtagene Autoleucel for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: Efficacy, Safety, and Place in Therapy. Cancer Management and Research 2025, 17, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L. S.; Wintrobe, M. M. Nitrogen Mustard Therapy: Use of Methyl-bis(β-chloroethyl)amine Hydrochloride and Tris(β-chloroethyl)amine Hydrochloride for Hodgkin’s Disease, Lymphosarcoma, Leukemia, and Certain Allied and Miscellaneous Disorders. Journal of the American Medical Association 1946, 132, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, L. S.; Wintrobe, M. M.; Dameshek, W.; Goodman, M. J.; Gilman, A.; McLennan, M. T. Landmark Article Sept. 21, 1946: Nitrogen Mustard Therapy—Use of Methyl-bis(β-chloroethyl)amine Hydrochloride and Tris(β-chloroethyl)amine Hydrochloride for Hodgkin’s Disease, Lymphosarcoma, Leukemia, and Certain Allied and Miscellaneous Disorders. JAMA 1984, 251(17), 2255–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J. A.; Condrau, F. The Pharmaceutical Industry in the Twentieth Century. Medical History 2010, 54(3), 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddow, A. The Chemotherapy of Cancer. BMJ 1950, 2(4691), 1271–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, R. The Air of History. Part III: The Golden Age in Arab Islamic Medicine—An Introduction. Heart Views 2013, 14(1), 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, S. I. A Note from History: The Discovery of Blood Cells. Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science 2003, 33(2), 237–238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hajdu, S. I. A note from history: landmarks in history of cancer, part 1. Cancer 2011, 117(5), 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, S. I. Pathfinders in oncology from ancient times to the end of the Middle Ages. Cancer 2016, 122(11), 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, M.; Sandhu, A.; Soneji, N.; Amiras, D.; Rockall, A.; Messiou, C.; Wallitt, K.; Barwick, T. D. Pictorial Review of Whole-Body MRI in Myeloma: Emphasis on Diffusion-Weighted Imaging. British Journal of Radiology 2020, 93(1115), 20200312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discovery 2022, 12(1), 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernigou, P. Ambroise Paré’s Life (1510–1590): Part I. International Orthopaedics 2013, 37(3), 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J. F.; Hosley, H.; Scharlau, C.; Carbone, P. P.; Frei, E.; Brindley, C. O.; Hall, T. C.; et al. A Controlled Trial of Urethane Treatment in Multiple Myeloma. Blood 1966, 27(3), 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jester, D. J.; Assefa, M. T.; Grewal, D. K.; Ibrahim-Biangoro, A. M.; Jennings, J. S.; Adamson, M. M. Military Environmental Exposures and Risk of Breast Cancer in Active-Duty Personnel and Veterans: A Scoping Review. Frontiers in Oncology 2024, 14, 1356001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahler, O. Zur Symptomatologie des Multiplen Myeloms: Beobachtung von Albomosurie. Prager Medizinische Wochenschrift 1889, 14, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Kalos, M.; Levine, B. L.; Porter, D. L.; Katz, S.; Grupp, S. A.; Bagg, A.; June, C. H. T Cells with Chimeric Antigen Receptors Have Potent Antitumor Effects and Can Establish Memory in Patients with Advanced Leukemia. Science Translational Medicine 2011, 3(95), 95ra73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiat, A. H. On the Synthesis of East and West. Philosophy East and West 1952, 1(4), 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesari, P. R.; Samuels, D.; Vegivinti, C. T. R.; et al. Navigating the Economic Burden of Multiple Myeloma: Insights into Cost-Effectiveness of CAR-T and Bispecific Antibody Therapies. Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports 2025, 20(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korngold, L.; Lipari, R. Multiple-Myeloma Proteins. III. The Antigenic Relationship of Bence Jones Proteins to Normal Gammaglobulin and Multiple-Myeloma Serum Proteins. Cancer 1956, 9(2), 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumbhaar, E. B.; Krumbhaar, H. D. The Blood and Bone Marrow in Yellow Cross Gas (Mustard Gas) Poisoning: Changes Produced in the Bone Marrow of Fatal Cases. The Journal of Medical Research 1919, 40(3), 497–508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kyle, R. A. Multiple Myeloma: An Odyssey of Discovery. British Journal of Haematology 2000, 111(4), 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, R. A.; Rajkumar, S. V. Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance and Smoldering Multiple Myeloma. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America 2007, 21(6), 1093–ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, R. A.; Rajkumar, S. V. Multiple myeloma. Blood 2008, 111(6), 2962–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, G.; Milstein, C. Continuous Cultures of Fused Cells Secreting Antibody of Predefined Specificity. Nature 1975, 256(5517), 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leaning, J. War Crimes and Medical Science. BMJ 1996, 313(7070), 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. W.; Gardner, R.; Porter, D. L.; Louis, C. U.; Ahmed, N.; Jensen, M.; Grupp, J. F.; Mackall, C. L. Current Concepts in the Diagnosis and Management of Cytokine Release Syndrome. Blood 2014, 124(2), 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeboom, G. A. The Story of a Blood Transfusion to a Pope. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 1954, 9(4), 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço, D.; Lopes, R.; Pestana, C.; Queirós, A. C.; João, C.; Carneiro, E. A. Patient-Derived Multiple Myeloma 3D Models for Personalized Medicine-Are We There Yet? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(21), 12888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malard, F.; Neri, P.; Bahlis, N. J.; Terpos, E.; Moukalled, N.; Hungria, V. T. M.; Manier, S.; Mohty, M. Multiple Myeloma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2024, 10(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, J. J. Medicine in Ancient Mesopotamia. World History Encyclopedia. 25 January 2023. Available online: https://www.worldhistory.org.

- McElwain, T. J.; Powles, R. L. High-Dose Intravenous Melphalan for Plasma-Cell Leukaemia and Myeloma. The Lancet 1983, 2(8354), 822–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, E. T.; Souza Júnior, C. V.; Ferreira, T. R. Andreas Vesalius 500 Years—A Renaissance That Revolutionized Cardiovascular Knowledge. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Cardiovascular 2015, 30(2), 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaleas, S. N.; Laios, K.; Tsoucalas, G.; Androutsos, G. Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (Paracelsus) (1493–1541): The Eminent Physician and Pioneer of Toxicology. Toxicology Reports 2021, 8, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micozzi, M. S. Disease in Antiquity: The Case of Cancer. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 1991, 115(8), 838–844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mokyr, J. A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, P. M.; Desai, S. P. A Clinician’s Rationale for the Study of History of Medicine. The Journal of Education in Perioperative Medicine 2014, 16(4), E070. [Google Scholar]

- Pierpont, T. M.; Limper, C. B.; Richards, K. L. Past, Present, and Future of Rituximab—The World’s First Oncology Monoclonal Antibody Therapy. Frontiers in Oncology 2018, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, R. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escurza, O.; Flores-Montero, J.; Óskarsson, J. Þ.; Sanoja-Flores, L.; Del Pozo, J.; Lecrevisse, Q.; Martín, S.; et al. Immunophenotypic Assessment of Clonal Plasma Cells and B-Cells in Bone Marrow and Blood in the Diagnostic Classification of Early-Stage Monoclonal Gammopathies: An iSTOPMM Study. Blood Cancer Journal 2023, 13(1), 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, S. V. Multiple Myeloma: 2024 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-Stratification, and Management. American Journal of Hematology 2024, 99(9), 1802–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, N.; Jialal, I. Bence-Jones Protein. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, 2023; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541035/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Ramani, M. L.; Bennett, R. G. High Prevalence of Skin Cancer in World War II Servicemen Stationed in the Pacific Theater. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1993, 28 5 Pt 1, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, R.; Coward, R. A.; Woywodt, A. What’s in a Name? Bence Jones Protein. Clinical Kidney Journal 2012, 5(5), 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, M. R.; Liaw, L.; Rosen, C. J.; Ghobrial, I. M. Dynamic Interplay between Bone and Multiple Myeloma: Emerging Roles of the Osteoblast. Bone 2015, 75, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinherz, E. L.; Kung, P. C.; Goldstein, G.; Levey, R. H.; Schlossman, S. F. Discrete Stages of Human Intrathymic Differentiation: Analysis of Normal Thymocytes and Leukemic Lymphoblasts of T-Cell Lineage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1980, 77(3), 1588–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retief, F. P.; Cilliers, L. Mesopotamian Medicine. South African Medical Journal 2007, 97(1), 27–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D. A Historical Perspective on Milestones in Multiple Myeloma Research. European Journal of Haematology 2018, 100(3), 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccomi, G.; Fornaciari, G.; Giuffra, V. Multiple Myeloma in Paleopathology: A Critical Review. International Journal of Paleopathology 2019, 24, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P. G.; Schlossman, R. L.; Weller, E.; Hideshima, T.; Mitsiades, C.; Davies, F.; LeBlanc, R.; et al. Immunomodulatory Drug CC-5013 Overcomes Drug Resistance and Is Well Tolerated in Patients with Relapsed Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2002, 100(9), 3063–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.; Orgueira, A. Mosquera; Saldarriaga, M. Mejía. How Artificial Intelligence Revolutionizes the World of Multiple Myeloma. Frontiers in Hematology 2024, 3, 1331109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabine, J. C. A History of the Classification of Human Blood Corpuscles (Part II). Bulletin of the History of Medicine 1940, 8(6), 785–805. [Google Scholar]

- Saltarella, I.; Desantis, V.; Melaccio, A.; Solimando, A. G.; Lamanuzzi, A.; Ria, R.; Storlazzi, C. T.; et al. Mechanisms of Resistance to Anti-CD38 Daratumumab in Multiple Myeloma. Cells 2020, 9(1), 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebinger, L. Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schuh, W.; Mielenz, D.; Jäck, H. M. Unraveling the Mysteries of Plasma Cells. Advances in Immunology 2020, 146, 57–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizutani, S.; Yamada, H. Long-Term Consequences of the Atomic Bombing in Hiroshima. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 2021, 59, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shok, N. P.; Sergeeva, M. S. The History of Medicine as an Academic Discipline: Traditions in Clinical Medical Education and Modern Teaching Methods. History of Medicine 2016, 3(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.; Dazzi, F. Bone Marrow Transplantation 1957–2019. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. L. War! What Is It Good For? Mustard Gas Medicine. CMAJ 2017, 189(8), E321–E322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneader, W. Drug Discovery: A History.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Solly, S. Remarks on the Pathology of Mollities Ossium with Cases. Medico-Chirurgical Transactions 1844, 27, 435–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strohmaier, G. Avicenna between Galen and Aristotle. In Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen; Hankinson, R. J., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, 2014; pp. 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Swan, D.; Madduri, D.; Hocking, J. CAR-T Cell Therapy in Multiple Myeloma: Current Status and Future Challenges. Blood Cancer Journal 2024, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavassoli, M. Blood, Pure and Eloquent; Wintrobe, M. M., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Teall, E. K. Medicine and Doctoring in Ancient Mesopotamia. Grand Valley Journal of History 2014, 3(1), Article 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, X. First Contributions in the History of Leukemia. World Journal of Hematology 2013, 2(3), 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Pereyra, L. H. Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus Surgical Revolution. Journal of Investigative Surgery 2008, 21(6), 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasetti, C.; Vogelstein, B. Cancer Etiology: Variation in Cancer Risk among Tissues Can Be Explained by the Number of Stem Cell Divisions. Science 2015, 347(6217), 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, F. Science as Ground of the Renaissance Artists. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism 2013, 10(1), 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhaya, S.; Yu, J. X.; Oliva, C.; Hooton, M.; Hubbard-Lucey, V. M. Impact of COVID-19 on Oncology Clinical Trials. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2020, 19(6), 376–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Donk, N. W. C. J.; Richardson, P. G.; Malavasi, F. CD38 Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma: Back to the Future. Blood 2018, 131(1), 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Way, C., III. War and Trauma: A History of Military Medicine—Part II. Missouri Medicine 2016, 113(5), 336–340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vogl, D. T.; Stadtmauer, E. A.; Tan, K. S.; Heitjan, D. F.; Davis, L. E.; Pontiggia, L.; Rangwala, R.; et al. Combined Autophagy and Proteasome Inhibition: A Phase 1 Trial of Hydroxychloroquine and Bortezomib in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Myeloma. Autophagy 2014, 10(8), 1380–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, I. L.; Shizuru, J. A. The Origins of the Identification and Isolation of Hematopoietic Stem Cells, and Their Capability to Induce Donor-Specific Transplantation Tolerance and Treat Autoimmune Diseases. Blood 2008, 112(9), 3543–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J. H. A Case of Multiple Myeloma. Journal of the Boston Society of Medical Sciences 1900, 4(8), 195. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, C.; Honda, S.; Tominaga, R.; Yokoyama, D.; Furuki, S.; Noguchi, A.; Koyama, S.; et al. Impact of Real-World Clinical Factors on an Analysis of the Cost-Effectiveness of ‘Immediate CAR-T’ versus ‘Late CAR-T’ as Second-Line Treatment for DLBCL Patients. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy 2025, 31(5), 339.e1–339.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, H.; Silbermann, M.; Ben-Arye, E.; Saad, B. Greco-Arab and Islamic Herbal-Derived Anticancer Modalities: From Tradition to Molecular Mechanisms. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2012, 2012, 349040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalloua, P.; Collins, C. J.; Gosling, A.; et al. Ancient DNA of Phoenician Remains Indicates Discontinuity in the Settlement History of Ibiza. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 17567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Timeline of major historical milestones in the medical understanding of cancer. The figure illustrates key stages in the evolving conceptualization of cancer. Stage 1 (Antiquity, 3000 BCE-500 BCE): early awareness, diagnosis, and therapeutic attempts in civilizations such as Sumer, Babylon, Egypt, and China. Stage 2 (Classical Era-Greek & Roman Medicine): contributions of ancient philosophers, Hellenistic exchange, and the formalization of cancer terminology and humoral theory. Stage 3 (Islamic Golden Age & Middle Ages): in the Islamic world, physicians advanced therapeutic practices including resection, pharmacological regimens, and dietary therapy, while in medieval Europe Galenic concepts were reinforced by the Church alongside the rise of alchemy. Stage 4 (Renaissance): technological advances, the emergence of systematic science and new disciplines such as anatomy and pathology, and a break with religious authority established the foundations for modern medicine and hematology. (Images adapted from Wikimedia Commons - public domain and CC BY-SA licensed sources; Created with BioRender.com; license agreement available upon request.).

Figure 1.

Timeline of major historical milestones in the medical understanding of cancer. The figure illustrates key stages in the evolving conceptualization of cancer. Stage 1 (Antiquity, 3000 BCE-500 BCE): early awareness, diagnosis, and therapeutic attempts in civilizations such as Sumer, Babylon, Egypt, and China. Stage 2 (Classical Era-Greek & Roman Medicine): contributions of ancient philosophers, Hellenistic exchange, and the formalization of cancer terminology and humoral theory. Stage 3 (Islamic Golden Age & Middle Ages): in the Islamic world, physicians advanced therapeutic practices including resection, pharmacological regimens, and dietary therapy, while in medieval Europe Galenic concepts were reinforced by the Church alongside the rise of alchemy. Stage 4 (Renaissance): technological advances, the emergence of systematic science and new disciplines such as anatomy and pathology, and a break with religious authority established the foundations for modern medicine and hematology. (Images adapted from Wikimedia Commons - public domain and CC BY-SA licensed sources; Created with BioRender.com; license agreement available upon request.).

Figure 2.

Biomedical disciplines emerging under the shadow of the World Wars. This conceptual illustration highlights the scientific and clinical fields whose development was significantly accelerated by the conditions of the two World Wars. Advances in pharmacology, hematology, oncology, stem-cell biology, and regenerative medicine were closely tied to wartime research on blood, trauma, and toxic exposures. At the same time, radiobiology, genetics, psychiatry, and reconstructive surgery expanded in response to the medical and societal demands created by mass casualties, radiation injuries, and psychological trauma. Together, these fields illustrate how modern biomedicine evolved not only through scientific discovery but also under the shadow of global conflict. (Visual concept: the soldier silhouettes and red background symbolize the shadow of war under which biomedical progress unfolded, representing a historical metaphor rather than a political statement. Created with BioRender.com; license agreement available upon request.).

Figure 2.

Biomedical disciplines emerging under the shadow of the World Wars. This conceptual illustration highlights the scientific and clinical fields whose development was significantly accelerated by the conditions of the two World Wars. Advances in pharmacology, hematology, oncology, stem-cell biology, and regenerative medicine were closely tied to wartime research on blood, trauma, and toxic exposures. At the same time, radiobiology, genetics, psychiatry, and reconstructive surgery expanded in response to the medical and societal demands created by mass casualties, radiation injuries, and psychological trauma. Together, these fields illustrate how modern biomedicine evolved not only through scientific discovery but also under the shadow of global conflict. (Visual concept: the soldier silhouettes and red background symbolize the shadow of war under which biomedical progress unfolded, representing a historical metaphor rather than a political statement. Created with BioRender.com; license agreement available upon request.).

Figure 3.

Key milestones in the early clinical and scientific history of multiple myeloma. Multiple myeloma was first described in 1844 as a distinct disease entity. In 1868, bone marrow was established as the site of blood-cell production, followed by the identification of plasma cells in 1895. By 1900, myeloma was recognized as a plasma-cell malignancy, leading to subsequent studies on bone-marrow aspiration and cytology (1908). Technological breakthroughs during the twentieth century included the development of serum-protein electrophoresis in 1939, which enabled the quantification of Bence Jones proteins, and the introduction of chemotherapy in 1943. Immunofixation and immunoelectrophoresis were described in 1953, followed by the identification of κ and λ immunoglobulin light chains in 1956. The same year, the first successful bone-marrow transplant was performed, inaugurating a therapeutic strategy that continues shaping the management of hematological malignancies. (Created with BioRender.com; license agreement available upon request.).

Figure 3.

Key milestones in the early clinical and scientific history of multiple myeloma. Multiple myeloma was first described in 1844 as a distinct disease entity. In 1868, bone marrow was established as the site of blood-cell production, followed by the identification of plasma cells in 1895. By 1900, myeloma was recognized as a plasma-cell malignancy, leading to subsequent studies on bone-marrow aspiration and cytology (1908). Technological breakthroughs during the twentieth century included the development of serum-protein electrophoresis in 1939, which enabled the quantification of Bence Jones proteins, and the introduction of chemotherapy in 1943. Immunofixation and immunoelectrophoresis were described in 1953, followed by the identification of κ and λ immunoglobulin light chains in 1956. The same year, the first successful bone-marrow transplant was performed, inaugurating a therapeutic strategy that continues shaping the management of hematological malignancies. (Created with BioRender.com; license agreement available upon request.).

Figure 4.

Multidimensional determinants of personalized medicine in multiple myeloma. This conceptual illustration highlights the diverse biological, psychological, and social factors that shape personalized care in multiple myeloma. Beyond genomic and molecular data (“omics”), outcomes are influenced by drug exposures, comorbidities, socioeconomic status, psychological resilience, nutrition, and occupational context. Together, these elements illustrate that genuine personalization extends beyond molecular profiling to encompass the lived experiences and environments of patients. (Created with BioRender.com; license agreement available upon request.).

Figure 4.

Multidimensional determinants of personalized medicine in multiple myeloma. This conceptual illustration highlights the diverse biological, psychological, and social factors that shape personalized care in multiple myeloma. Beyond genomic and molecular data (“omics”), outcomes are influenced by drug exposures, comorbidities, socioeconomic status, psychological resilience, nutrition, and occupational context. Together, these elements illustrate that genuine personalization extends beyond molecular profiling to encompass the lived experiences and environments of patients. (Created with BioRender.com; license agreement available upon request.).

Table 1.

Key milestones in the discovery of blood, bone marrow, and the foundations of hematology.

Table 1.

Key milestones in the discovery of blood, bone marrow, and the foundations of hematology.

| Pioneering Discovery |

Scientist(s) |

Reference |

|

1674 First observation of blood cells under the microscope |

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek |

Coller, 2015 |

|

1700 Proposal that bones without marrow (e.g., middle ear bones) might serve other functions beyond nutrition |

Guichard Joseph Duverney |

Duverney, 1700 |

|

1770 William Hewson, considered the father of hematology, described white blood cells, coagulation, fibrin, and blood clotting mechanisms |

William Hewson |

Doyle, 2006 |

|

1818 First successful human blood transfusion |

James Blundell |

Lindeboom, 1954; Baskett, 2002 |

|

1838 Proposal of the cell theory |

Matthias Schleiden & Theodor Schwann |

Cooper, 2011 |

|

1868 Independent demonstrations by Neumann and Bizzozero of the role of bone marrow in hematopoiesis |

Ernst Neumann & Giulio Bizzozero |

Coller, 2015 |

|

1877 Introduction of staining techniques that differentiated blood cell types |

Paul Ehrlich |

Coller, 2015 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).