Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

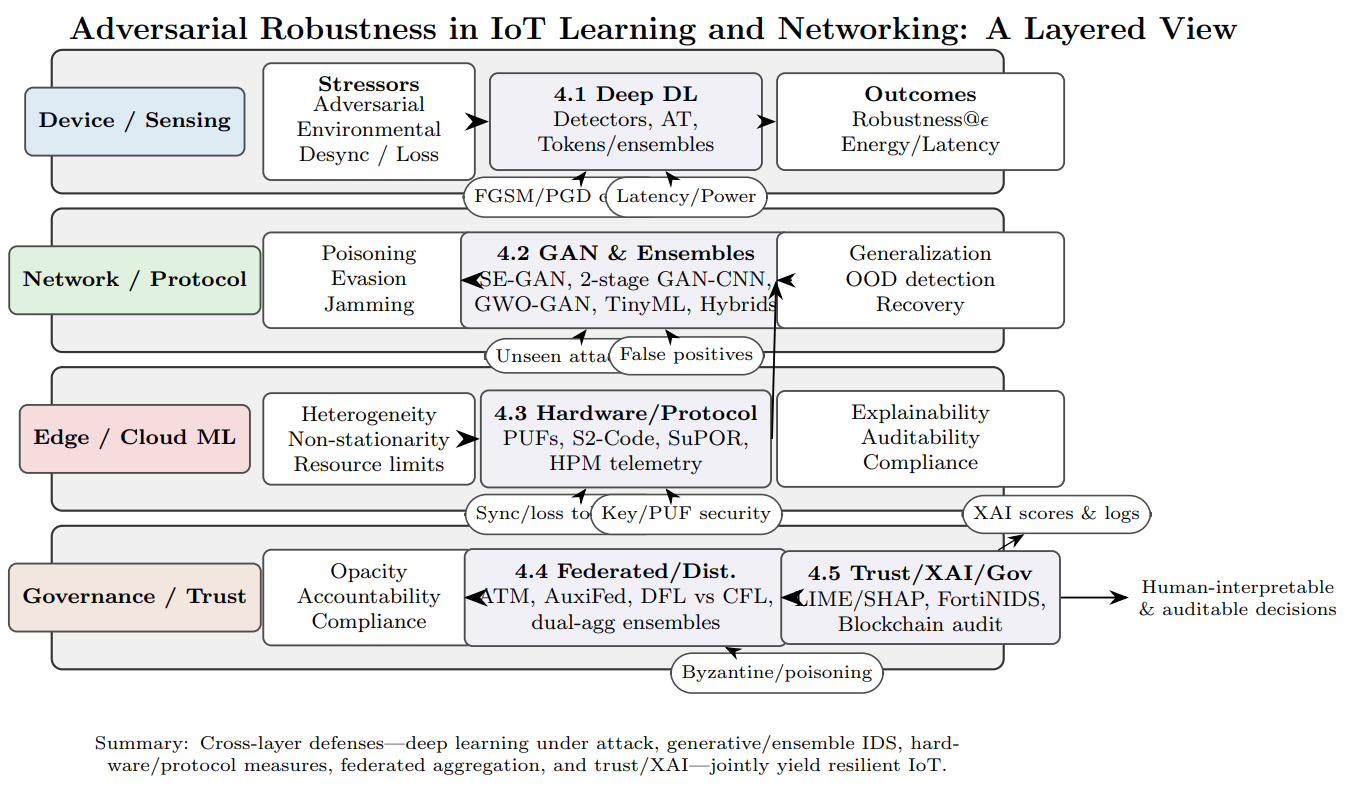

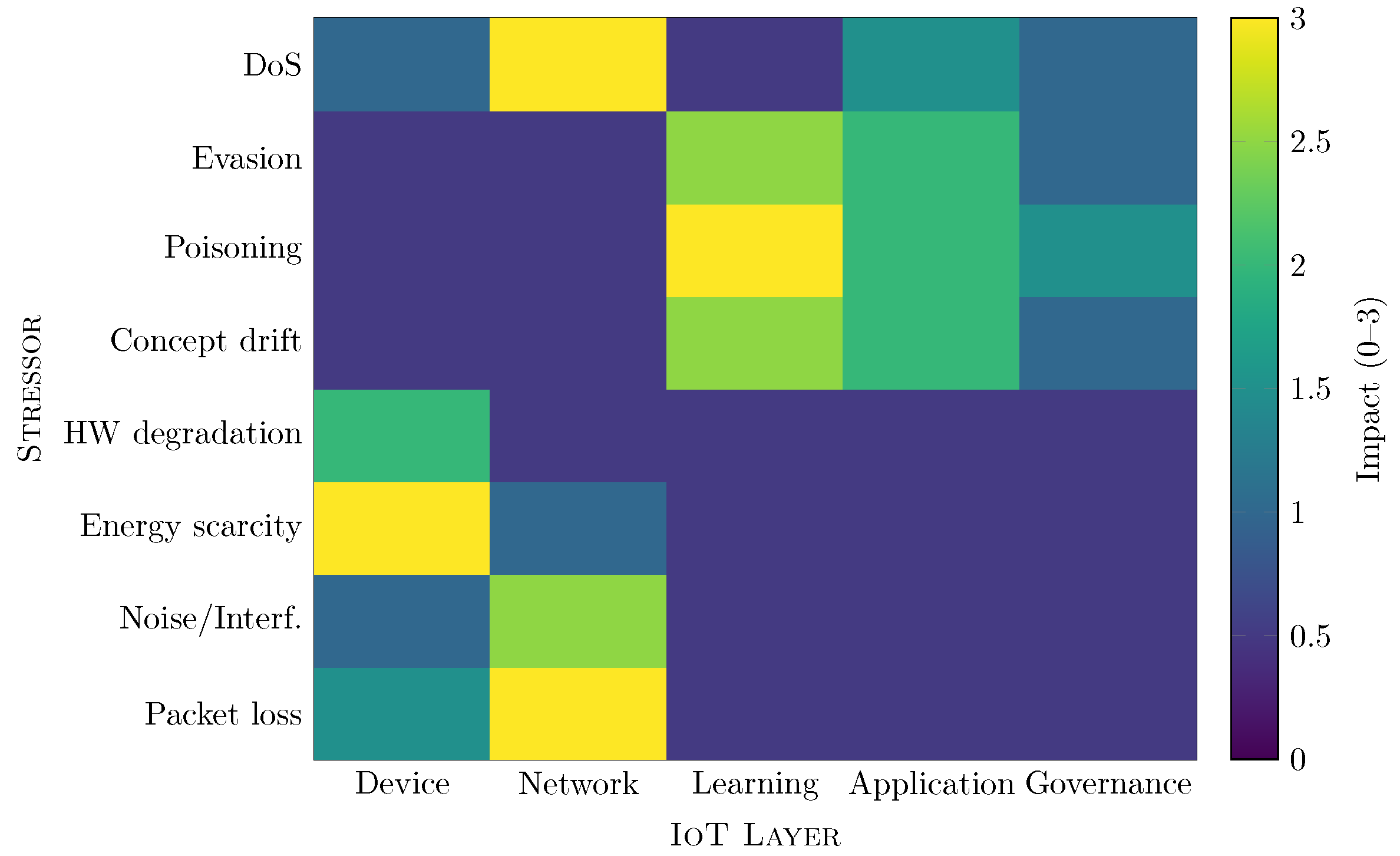

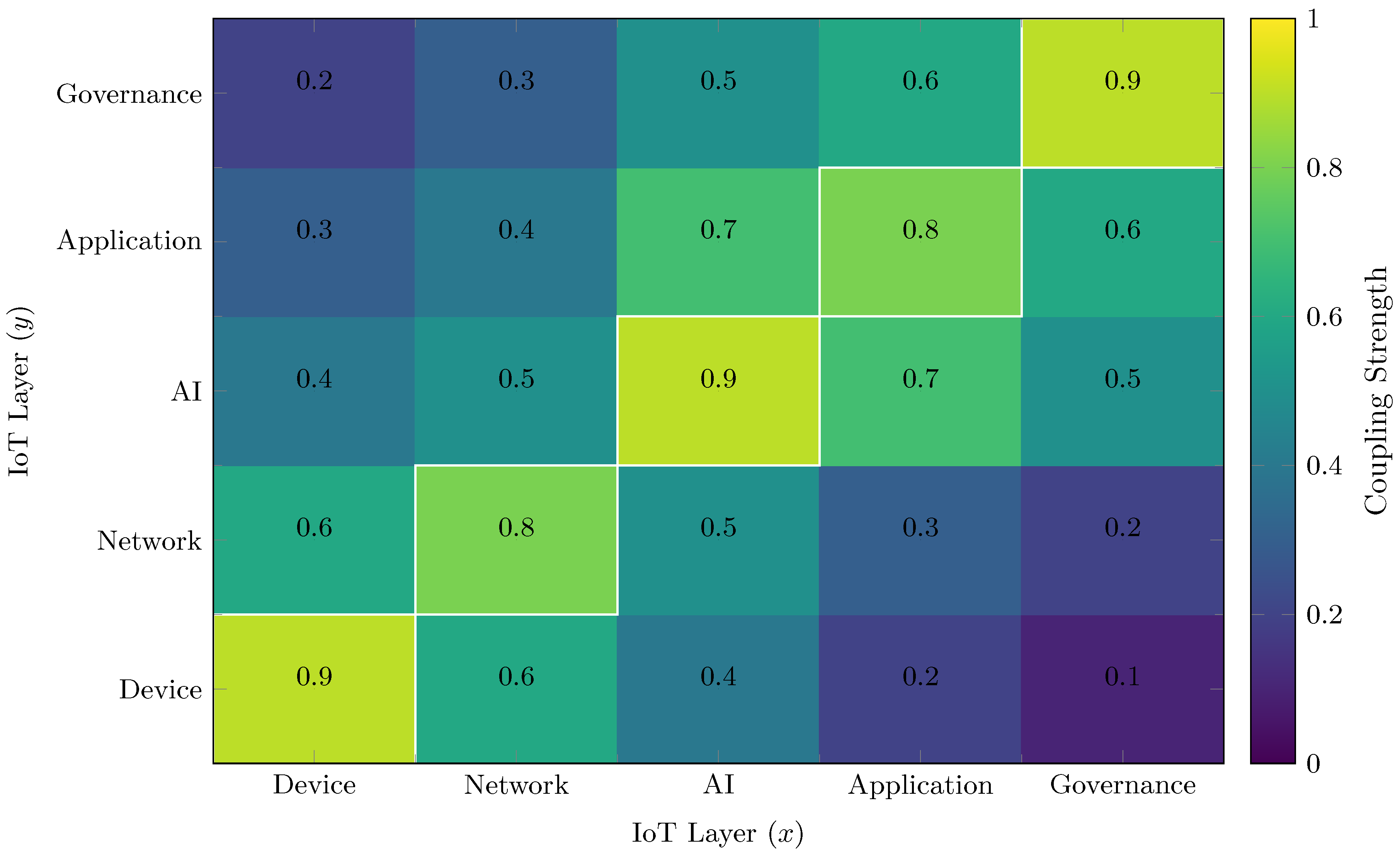

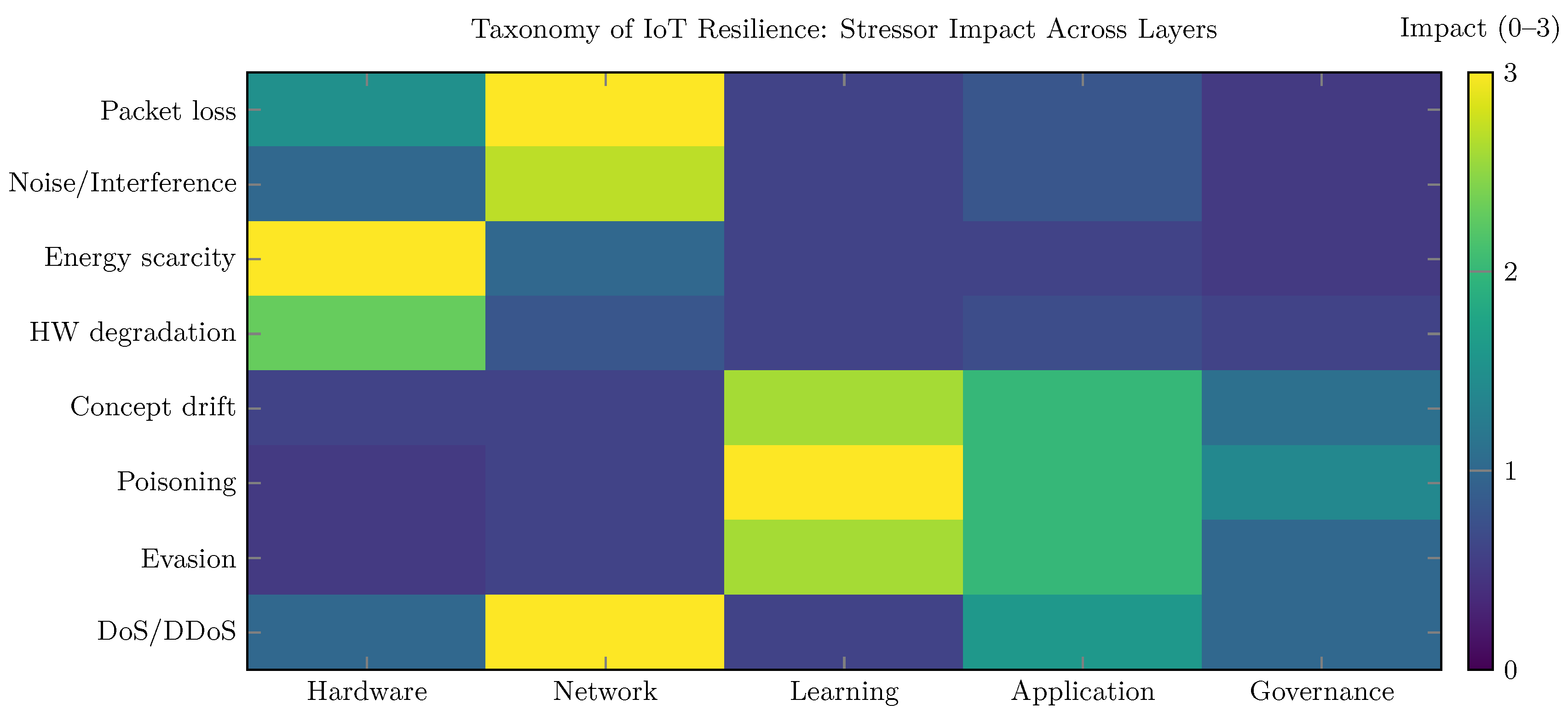

- A unified taxonomy of IoT resilience, categorizing methods by stressor type (adversarial, environmental, hybrid) and by the IoT layer they protect (hardware, protocol, learning, application, or governance).

- A systematic, critical analysis of recent research, including federated adversarial learning, PUF-based authentication, GAN-driven defenses, explainable-AI governance, and multi-agent recovery frameworks.

- A forward-looking discussion of challenges and future directions, emphasizing the need for hybrid-stress benchmarks, cross-layer defense orchestration, and the integration of antifragile design principles into practical IoT deployments.

2. Related Work

3. Background and Definitions

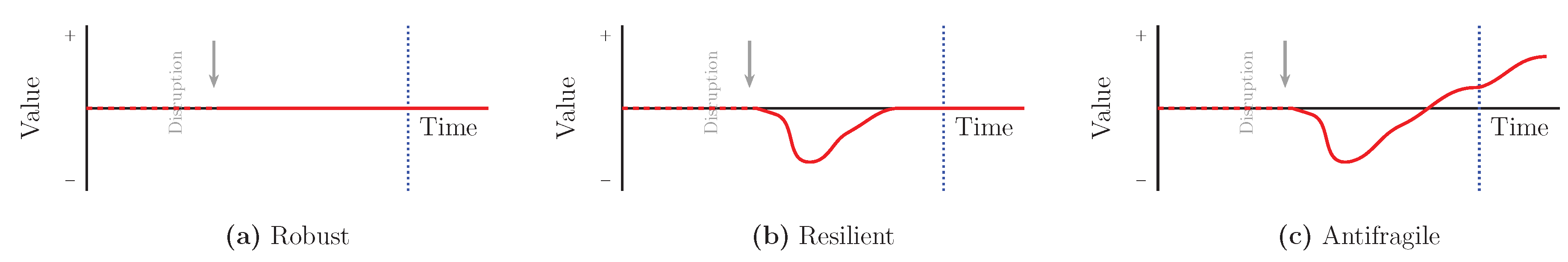

3.1. From Robustness to Resilience to Antifragility

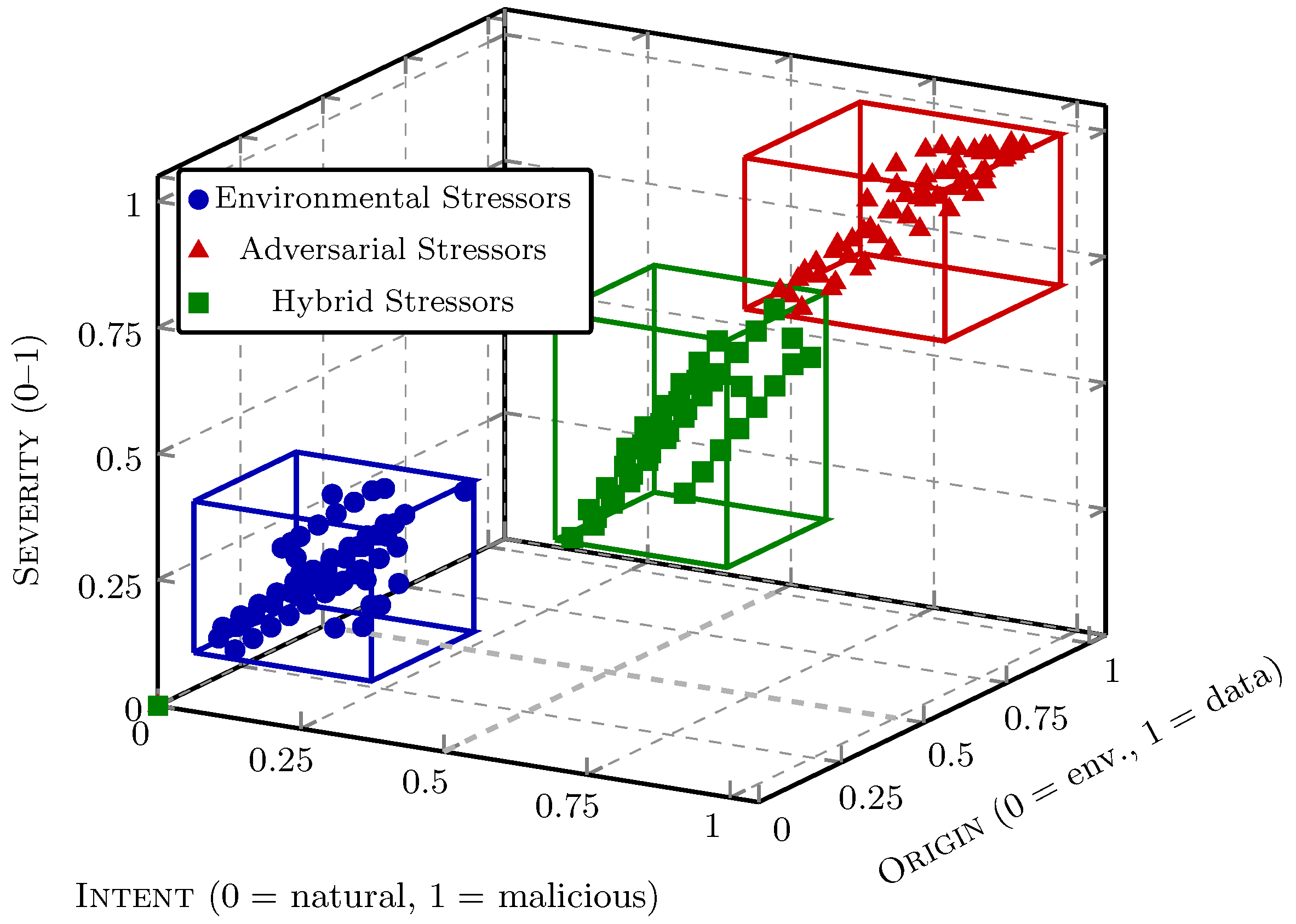

3.2. Stressors in IoT Systems

-

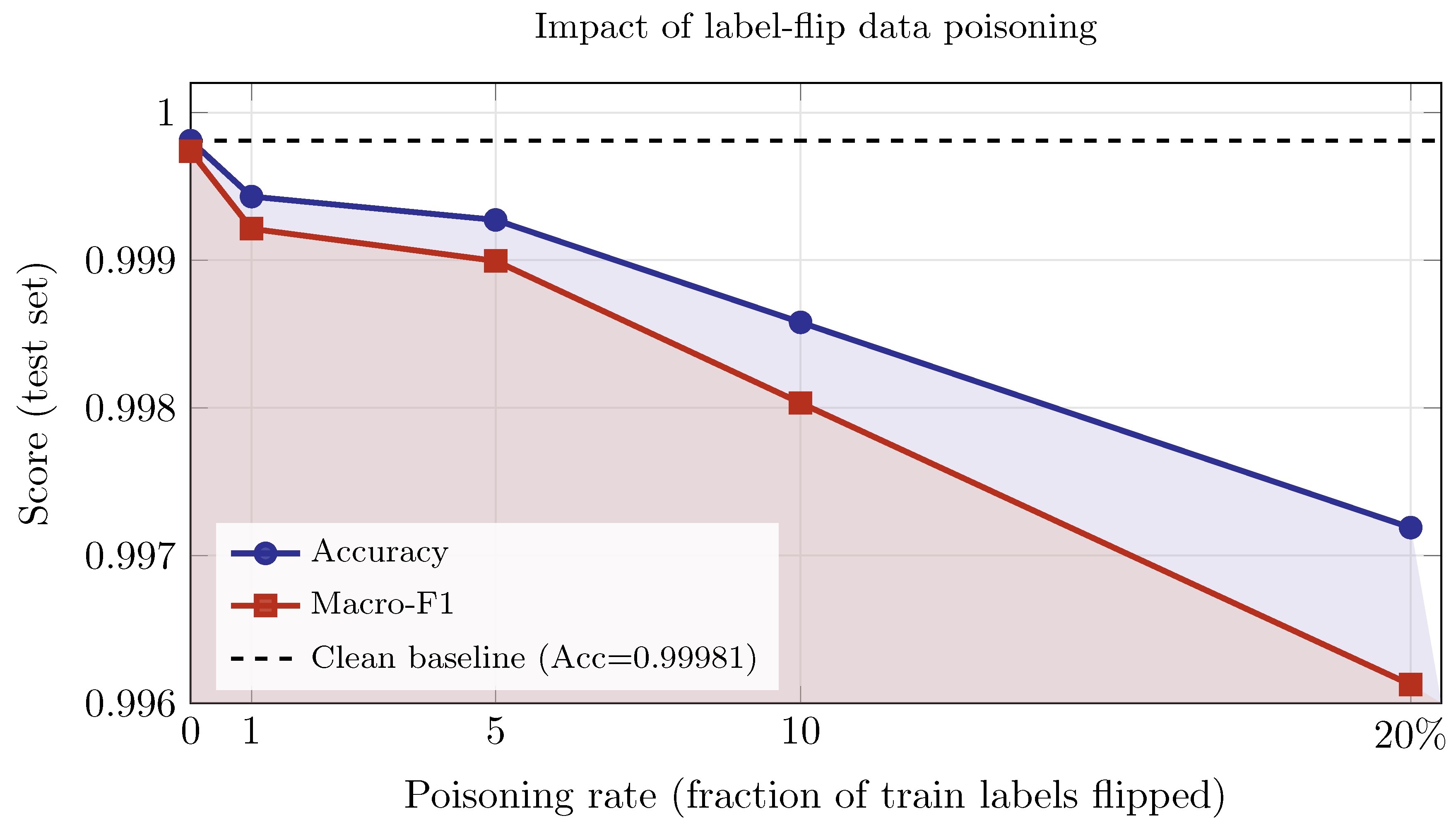

Data poisoning: before or during training, an adversary corrupts a fraction of the training set so that the learned model exhibits degraded or adversarially biased behavior at deployment [51,52]. Common tactics include label flipping, clean labeling, backdoor or trigger attacks, and model or gradient poisoning. Label-flip poisoning changes ground-truth labels while leaving features intact [53]. Clean-label poisoning creates what appear to be legitimate examples that manipulate the decision boundary [54]. Backdoor or trigger attacks exploit an uncommon pattern, leading the model to misclassify any input that includes it [55]. Model or gradient poisoning in federated environments can inject biases into global aggregation (for instance, as a result of Byzantine attacks). As shown in Figure 5, we simulate label-flip poisoning on ToN-IoT by flipping a fraction of training labels uniformly at random while keeping validation and test sets clean. Test Accuracy and Macro-F1 decrease smoothly as p increases. The small absolute drops (e.g., Acc at ) indicate that random label flips primarily act as label noise, to which this tabular model is relatively robust—likely due to high class separability and redundancy in features. This is a lower bound on risk. Structured attacks, such as class-conditional or rare-class targeting, clean-label poisoning, and backdoor triggers, can cause larger errors at lower probabilities p. The effects may also amplify in federated training without robust aggregation methods. Attack goals when using poisoning attacks range from availability (overall error inflation) to targeted or class-specific failures on chosen classes or trigger patterns. Mitigations include distributional validation and data filtering (outlier and influence diagnostics), robust training losses and regularization, differential clipping/noise in FL, robust aggregation (trimmed mean, coordinate-wise median, Krum), holdout audits with canaries, and cryptographic or signed provenance logs to trace data lineage [51,52,56].

-

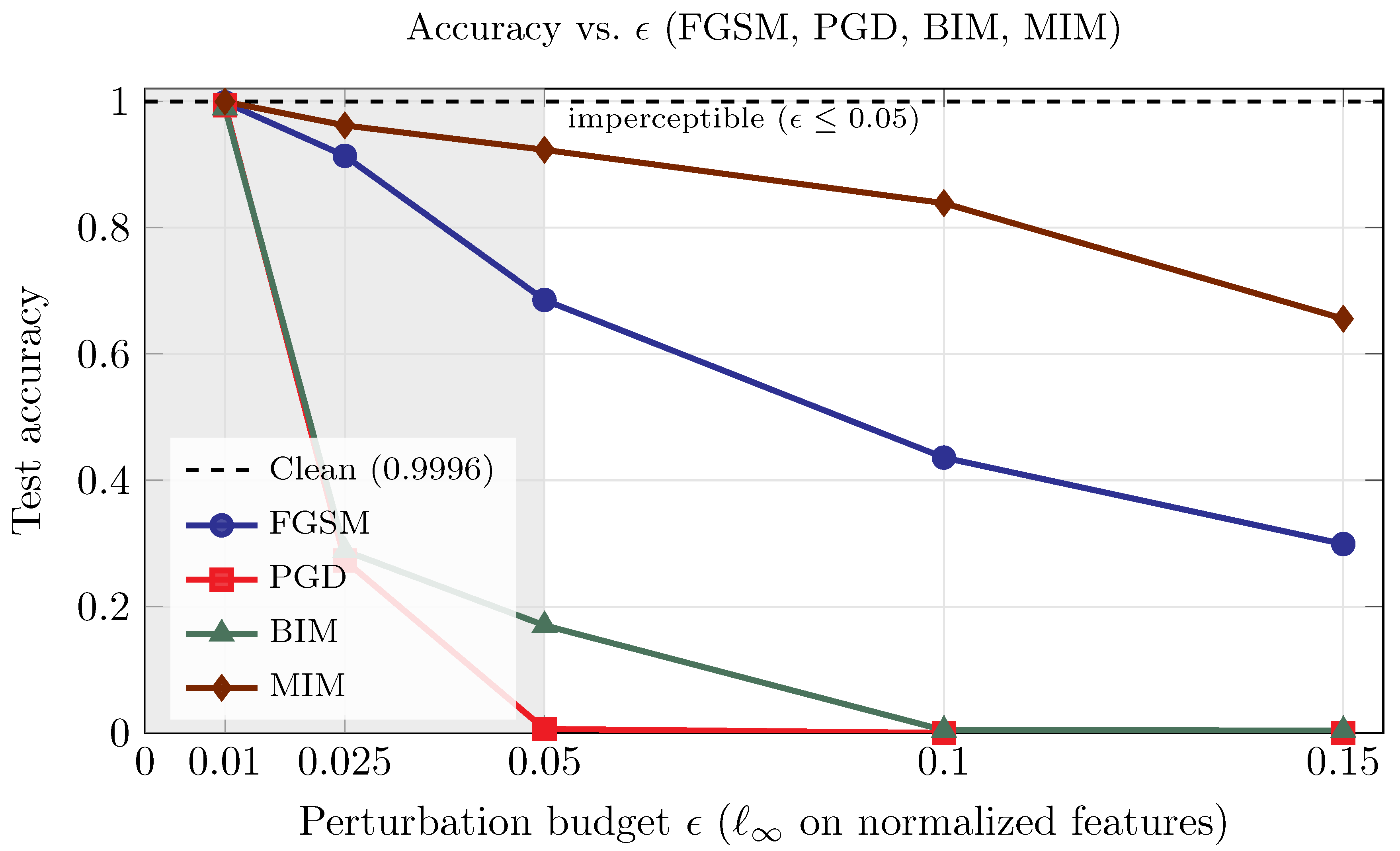

Evasion at inference: once models are deployed, an adversary can add carefully tuned, norm-bounded noise to inputs so that the perturbations remain visually or statistically imperceptible but still induce misclassification [57]. Representative attacks include: fast gradient sign method (FGSM) [58], basic iterative method (BIM) [59], projected gradient descent (PGD) [60], momentum iterative method (MIM) [61], and DeepFool [62]. FGSM takes a single step that prompts each input feature in the direction that most increases the loss (the sign of the gradient), with step size , yielding a small -bounded change that can already flip the prediction. BIM/Iterated-FGSM repeats FGSM in many small steps (step size ), clipping after each step to keep the total perturbation within the ball of radius . This iterative refinement typically finds stronger adversarial examples than a single step. PGD further strengthens BIM by starting from a random point inside the -ball and then iterating gradient steps with projection back to the ball; random restarts help avoid weak local optima, which is why PGD is a widely used (strong first-order) baseline [63]. MIM (Momentum Iterative FGSM) also iterates, but it accumulates a momentum term (an exponential average of recent gradients) to stabilize the update direction; this often improves transferability, making the crafted examples more effective even on unseen models [64]. DeepFool approximates the classifier’s decision boundary and iteratively moves the input in the smallest direction that crosses that boundary, aiming for near-minimal change; unlike the -bounded methods above, it does not fix a budget in advance but adapts the perturbation to reach misclassification with minimal effort [65]. To illustrate the effect of evasion at inferecne attacks, we experimented using ToN-IoT dataset and control the maximum perturbation size by a budget (e.g., ), where bounds the per-feature deviation under the chosen norm (typically ); here, the symbol ∈ means is an element of (i.e., chosen from the set). Figure 6 shows the test accuracy under evasion as the perturbation budget increases. Relative to the clean baseline where the accuracy is 0.9996, FGSM declines gradually to 0.299 at . At the same time, PGD and BIM collapse rapidly (e.g., at , accuracy is 0.006 and 0.170, respectively, and for ). MIM degrades slowest among iterative methods (0.962 at , 0.923 at , 0.656 at ). The shaded band () denotes our imperceptible regime, where iterative attacks already cause large drops (e.g., PGD 0.273, BIM 0.288 at ). Even with small budgets within our imperceptible range, iterative attacks such as PGD and BIM can substantially degrade accuracy, while MIM tends to degrade more slowly on our model; DeepFool, which does not use an explicit , instead adapts its steps to cross the nearest decision boundary. A representative example of evasion at inference, a small modulation change in a wireless packet could bypass an intrusion detection model. To address such attacks, it is a valuable practice to integrate one or more of the following techniques: adversarial training, randomized smoothing, and/or cross-modal input consistency checks.

-

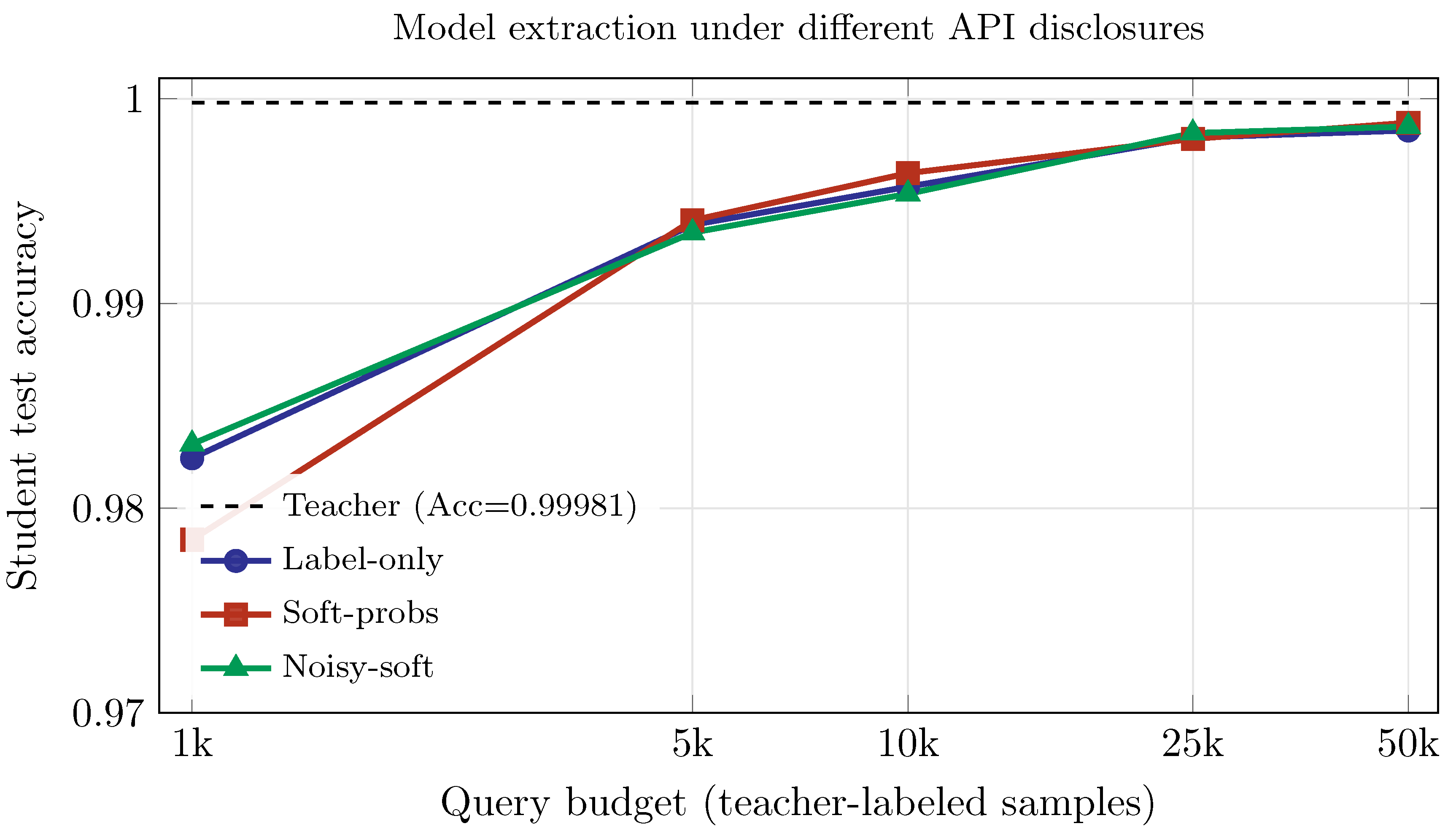

Model extraction and inversion: in cloud/edge APIs, an adversary can iteratively query a deployed (black-box) model to extract a high-fidelity surrogate (recovering decision boundaries or even approximating parameters), or to invert the model to reconstruct features of sensitive training records [66]. Leakage surfaces include top-1 labels, confidence scores (soft probabilities), and auxiliary signals (temperature-scaling artifacts, calibration curves), which together facilitate knowledge distillation and amplify privacy risks—potentially exposing patient attributes, user habits, or network signatures [67,68]. As shown in Figure 7, to illustrate model extraction, we train a high-accuracy teacher (test Acc ) and simulate an attacker who can fit a student using teacher-labeled queries under three disclosures: label-only (hard top-1), soft-probs (full confidences), and noisy-soft (soft-probs with Laplace noise, ). Across budgets , student accuracy rises monotonically toward the teacher: for example, at queries the student attains for {label-only, soft-probs, noisy-soft}, and at reaches respectively—still below the dashed teacher baseline. Soft-prob disclosure yields the strongest extraction at high budgets (e.g., at ), while injecting calibrated noise slightly suppresses student performance (noisy-soft ) with minimal utility loss for benign users, and label-only sits in between. The x-axis is log-scaled to emphasize early-query efficiency: most gains occur by – queries, underscoring the value of early throttling and score suppression in production APIs. Practical approches that can be used to mitigate model extraction and inversion include API governance (authentication, rate or volume limits, burst throttling, per-class quota), output minimization (label-only, confidence truncation or quantization, randomized response on scores), noise mechanisms (Laplace or Gaussian noise on logits or probabilities), and privacy-preserving training (DP-SGD or post-training DP), complemented by extraction watermarking, server-side audit tests (monitor agreement patterns vs. natural data), and adaptive blocking when query statistics deviate from benign usage [67,68].

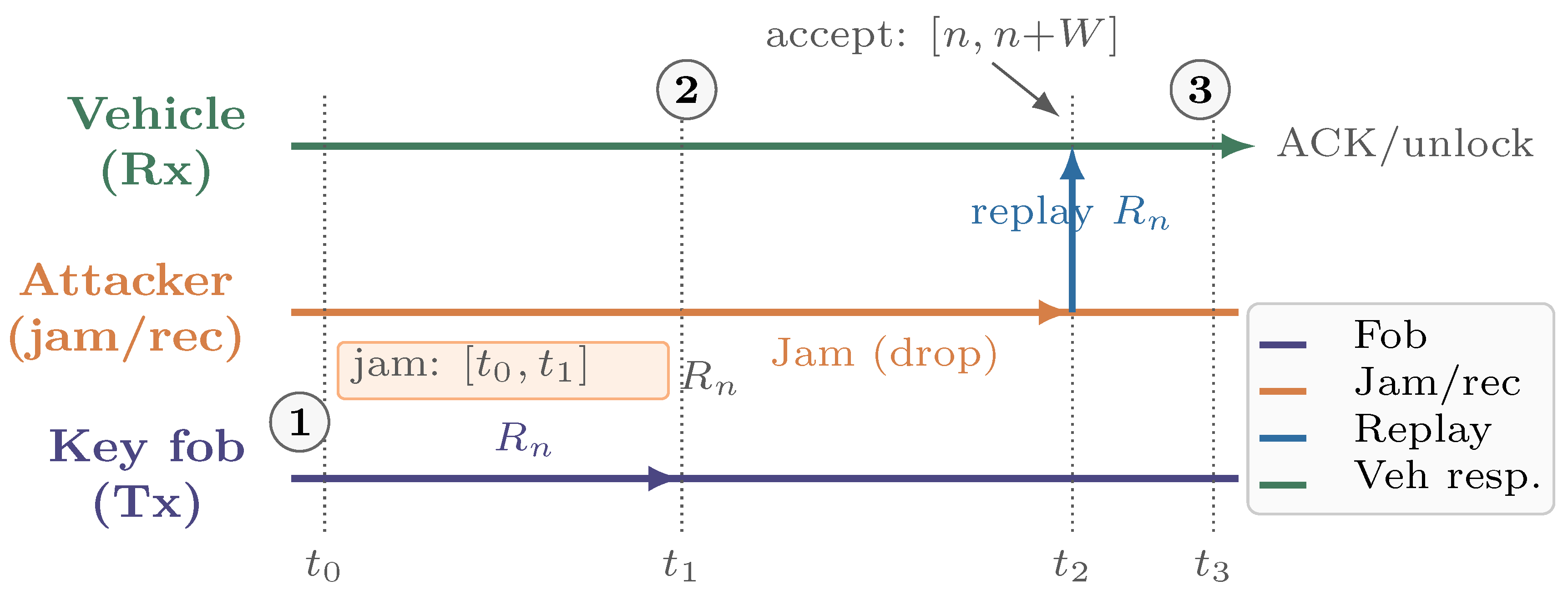

- Protocol spoofing: beyond software-level API abuse, adversaries can impersonate endpoints by manipulating the RF channel itself. Common attack vectors include satellite deception, such as GPS spoofing, link-layer replay attacks like Roll-Jam, and waveform injections that imitate a device’s modulation [69,70,71]. In a typical replay attack, illustrated in Figure 8, an attacker captures a fob’s rolling code at time , preventing the vehicle’s receiver from decoding it at time . The attacker then replays within the receiver’s acceptance window at time , causing the vehicle to respond with an unlock or acknowledgment (ACK) at time . To mitigate protocol spoofing, various methods can be used, including cross-layer defenses, desynchronization-resilient rolling-code updates, PHY hardening, spectrum-level defenses, and RF fingerprinting. Defense at the cross-layer can be employed, such as cryptographic freshness with nonce-based challenge–response and strict single-use counters (no grace window or for critical actions). Desynchronization-resilient rolling code updates use session-bound keys and monotone counters with limited resynchronization attempts. Physical layer security is enhanced through time-of-flight and multi-antenna angle-of-arrival checks to limit plausible emitter geometry. RF fingerprinting that exploits device-specific imperfections (carrier-frequency offset, I/Q imbalance, transient shape) and channel-state/timing features to reject cloned waveforms [72,73]. Spectrum-level defenses (frequency-hopping spread spectrum (FHSS) or direct-sequence spread spectrum (DSSS), adaptive carrier sensing) with anomaly analytics on energy, inter-frame timing, and Doppler patterns. Operational controls—lockout or backoff after failed frames, localized rate-limits, and out-of-band second factors (e.g., proximity ultra wide band (UWB) ranging)—further shrink the attack surface while preserving usability [74].

-

Denial-of-Service/Distributed DOS (DoS/DDoS): in IoT environments, attackers exploit resource limitations to overwhelm bandwidth at gateways or drain device resources (CPU, memory, battery), resulting in service interruptions or cascading failures [75,76,77]. Botnet-driven swarms of compromised endpoints (e.g., cameras or smart plugs) can generate high-rate floods or carefully timed bursts that defeat naive token buckets, overwhelm queueing buffers, and trigger retransmission storms, further reducing goodput. Let L denote the offered load (benign and malicious) and C the gateway capacity. In the benign regime, goodput G roughly increases with . However, under attack, issues like queue overflows and packet drops cause G to drop sharply below a critical threshold , well before reaching nominal capacity C. This behavior is reflected in the goodput versus offered load curve in Figure 9. Rate limiting delays collapse goodput; puzzles add slight latency but reduce bot amplification; and edge filtering maximizes performance beyond C by eliminating unnecessary traffic before it occupies limited buffer space. In practice, robust deployments combine the following practical countermeasures with lightweight anomaly scoring, short control loops for threshold tuning, and fail-open exceptions for safety-critical flows to avoid overblocking. Practical countermeasures span admission control and in-network enforcement, trading reactivity against collateral damage. Per-packet/flow rate limiting caps burstiness and bounds worst-case load, raising while keeping implementation lightweight at edge routers [78]. Client puzzles that are stateless and adjustable in difficulty shift computational tasks to suspected sources, limiting the impact of bot swarms on CPU usage and reducing unnecessary gateway processing. The difficulty of the puzzles can be modified based on observed queue occupancy to maintain quality of service for compliant devices [79]. In-network filtering at access gateways (e.g., prefix-/behavior-based filters, Bloom-filter aggregates, or programmable data-plane rules) removes malicious traffic near its ingress and prevents backpressure into constrained subnets, preserving goodput even when [80].Figure 8. An illustration of link-layer replay attack in the form of Roll–Jam on rolling codes.

Figure 9. Goodput vs. offered load under IoT DoS/DDoS.

Figure 9. Goodput vs. offered load under IoT DoS/DDoS.

- Packet loss and desynchronization: wireless IoT connections—especially within low-power wide-area networks (LPWANs)—often encounter burst losses caused by interference, duty-cycle limitations, and synchronization drift [82,83]. In rolling-code systems, missing even one frame can lead to a permanent authentication failure [84,85]. To mitigate these problems, it is advantageous to use self-synchronizing codes [86], selective retransmissions [87], and interleaved packet scheduling [88].

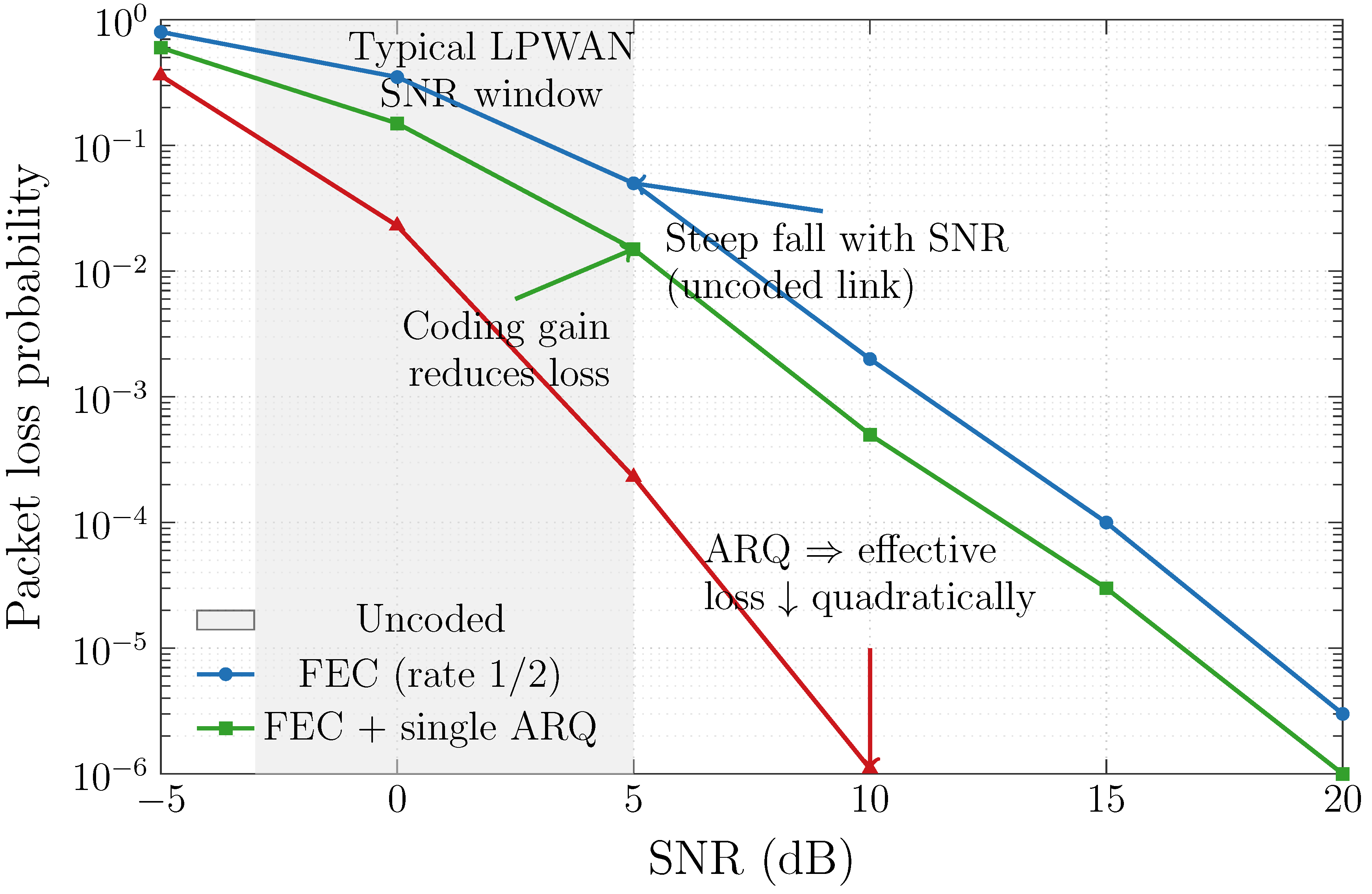

- Noise and interference: the unlicensed industrial, scientific, and medical (ISM) bands that most IoT devices rely on are congested [89], leading to signal collisions, higher bit-error rates, and increased timing jitter. In industrial control systems, this congestion can destabilize control loops [90]. To deal with noise and interference, the following measures can be employed: frequency hopping, adaptive modulation/coding, and sensor fusion with uncertainty-aware weighting [91,92]. To better illustrate the impact of physical-layer resilience mechanisms under realistic channel conditions, Figure 10 shows the packet loss probability in relation to the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for uncoded, forward error correction (FEC)-coded, and FEC and automatic repeat request (ARQ) transmission modes. The uncoded link shows the classical waterfall region where even small SNR degradations cause orders-of-magnitude increases in loss. By introducing FEC (rate ), the reliability curve shifts toward lower SNR values—representing a coding gain of several decibels. Adding a single ARQ layer significantly reduces effective loss, demonstrating that lightweight hybrid error-control strategies can enhance environmental resilience without redesigning protocols. The shaded area represents the typical SNR range of −3 to +5 dB for LPWAN, crucial for maintaining connectivity in noisy industrial and outdoor settings.

- Energy scarcity: battery-powered and energy-harvesting devices often enter aggressive sleep modes [93], resulting in sparse or delayed data streams. For instance, a remote soil sensor may report only once per hour on cloudy days. It is helpful to implement event-driven sensing, compressive sampling, and lightweight on-device learning (i.e., tiny machine learning (TinyML)) [94,95,96,97].

- Hardware degradation: over time, sensors drift due to temperature fluctuations, aging, or wear [98]. PUFs used for device identification can also lose reliability under thermal stress [99]. To address these issues, specific measures can be utilized, such as periodic recalibration, helper data schemes for PUF correction, and redundant sensing with majority voting [100,101,102].

- Non-stationary data (concept drift): IoT data often evolves as environments, users, or firmware change [103]. A model trained on winter energy patterns may perform poorly during the summer months [104]. To mitigate this issue, the following measures can be employed: sliding-window retraining, online learning, and drift detection algorithms such as adaptive windowing (ADWIN) or the drift detection method (DDM) [105,106].

3.3. Layers of IoT Resilience

3.4. Metrics and Evaluation Frameworks

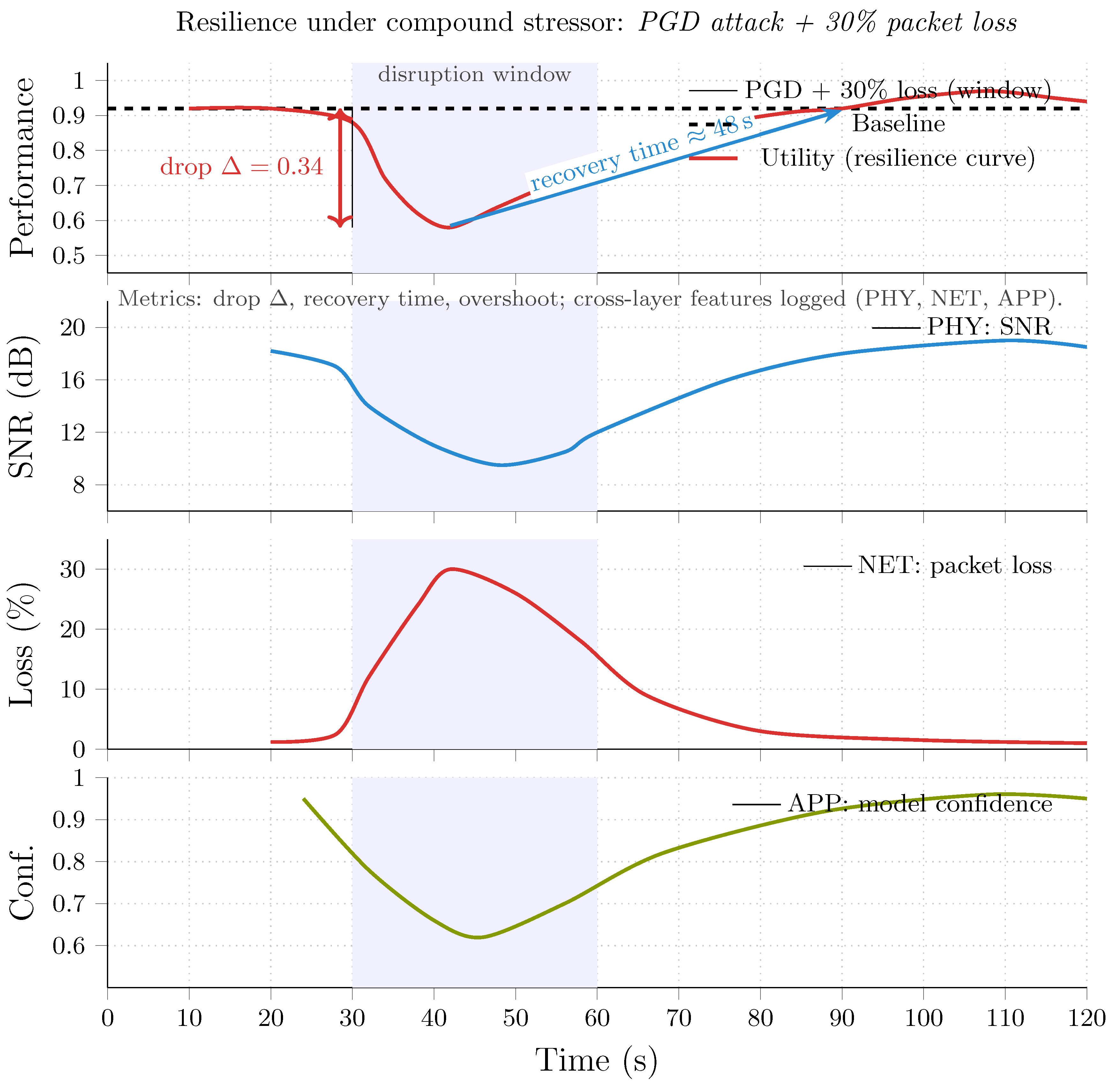

- Performance metrics under stress: the first dimension assesses how well a model or system maintains operational quality during and after disruptions. Common indicators include: accuracy or macro-F1 under perturbation, area under the resilience curve (AURC), and latency and energy overhead. Accuracy, or macro-F1, evaluates prediction consistency under difficult conditions, such as data degradation or network issues (e.g., 30% packet loss). The AURC measures performance from the start of a disruption to recovery, with a higher AURC indicating a faster or more complete restoration. Latency and energy overhead capture the efficiency cost of resilience mechanisms, such as self-healing routing or retraining after poisoning. For instance, a resilient intrusion detection model might drop from 95% to 70% accuracy under a PGD adversarial attack but recover to 90% within 200 s—yielding a higher AURC than a static model that stagnates at 75%.

- Scalability and system-level metrics: resilience must extend beyond individual devices to distributed IoT environments where hundreds of clients cooperate through federated or edge learning. Evaluations, therefore, include client scalability, network resilience index, and cross-layer coordination latency. Client scalability varies in performance as the number of participants increases (e.g., from 10 to 150 nodes in federated learning). Network resilience index is measured by the ratio of sustained throughput or model convergence speed under partial connectivity loss (e.g., 20% clients offline). Cross-layer coordination latency measures the time between fault detection at one layer and adaptation at another, indicating the resilience mesh’s interdependence. In a federated healthcare network, an adaptive aggregator that maintains over 85% accuracy with a 30% client dropout rate demonstrates better resilience than one that drops below 70%.

- Trust, transparency, and interpretability metrics: because resilience also involves human oversight, operators must trust the system’s adaptation process. Interpretability metrics quantify this human–machine alignment using Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) or local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) attribution stability, trust-score variance, and recovery transparency [122]. SHAP and LIME attribution stability assess the consistency of feature importance across model recoveries, highlighting semantic preservation. Trust-score variance measures fluctuations in model reliability under stress, with lower variance signifying more stable behavior. Recovery transparency is a qualitative or quantitative measure of how well recovery actions are logged, explained, and verifiable (e.g., via blockchain audit trails). For example, a resilient anomaly detector should not only regain performance after retraining but also maintain stable SHAP attributions—ensuring that its reasoning process remains interpretable and trustworthy.

- Hybrid and compound benchmarks: disruptions in real-world IoT environments result from multiple factors. Current assessment frameworks should use compound stress testing by introducing various stressors—like adversarial perturbations, packet loss, and energy constraints—at the same time. Hybrid benchmarks, such as compound-scenario testing, cross-layer metrics, and resilience trade-off curves, remain scarce in the literature but are essential for realistic validation. Compound scenario testing involves two or more measures, e.g., PGD and 30% packet loss or concept drift and node dropout. Cross-layer metrics combine physical-layer link reliability, network-layer throughput, and model-layer recovery accuracy. Resilience trade-off curves visualize the balance between recovery speed, energy cost, and trust stability across scenarios. For example, an antifragile federated model might slightly reduce accuracy during an attack but significantly shorten recovery time and energy cost across combined network and model stressors.

4. Taxonomy of IoT Resilience

5. Adversarial Robustness in IoT Learning and Networking

5.1. Deep Learning Under Adversarial Attack

| Paper | Methodology | Dataset(s) | Main Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rahman et al. [128] | Transformer-based attack detector and disease classifier | Chest X-ray, Retinal OCT, Skin cancer | F1 = 0.97; Accuracy = 0.98; strong detection recovery | High compute cost; limited real-time feasibility |

| Güngör et al. [130] | Stacking ensemble (Deep learners and LR/RF/XGBoost) | NASA C-MAPSS, UNIBO Powertools | Up to 60% higher robustness vs. baselines | Increased latency and complexity; not edge-suitable |

| Zhang et al. [132] | Vision Transformer with adversarial indicator token | RML [148] and RDL [149] | Stronger resilience to FGSM/PGD/BIM; interpretable attention | Tested only under white-box conditions; no hardware validation |

| Zyane and Jamiri [133] | CNN with adversarial training and feature squeezing | IoT-23 intrusion dataset | Accuracy: 32% → 61% under PGD attack | Static defense; vulnerable to adaptive/black-box attacks |

| Efatinasab et al. [135] | GAN and OOD samples | Electrical Grid Stability Simulated | Accuracy = 0.981 (stability); robust to GAN-based perturbations (0.989) | Simulation-only; limited scope |

| Javed et al. [137] | Review: adversarial training, uncertainty, privacy tools | Medical diagnostic DL | Synthesizes robustness metrics; highlights trade-offs | Survey only; lacks empirical evaluation |

| Moghaddam et al. [140] | Transformer, GAN augmentation, and bio-inspired optimizer | CIC-IoT-2023, TON_IoT | Accuracy: 99.67%, 98.84%; handles imbalance | High computational load; limited edge scalability |

| Tian et al. [142] | Adversarial attack/defense study for NN state estimation (FAA/RSA); adversarial training and input sanitization | Synthetic power-system measurements (IEEE bus cases) | Small perturbations cause significant estimation bias; adversarial training substantially restores accuracy on attacked inputs with modest clean-data impact | White-box focus; offline simulation only; no embedded/real-time validation |

| Tusher et al. [144] | FEMUS-Nowcast: feature-enhanced multi-scale U-Net with robustness-oriented augmentation/denoising | SKIPP’D dataset for solar nowcasting | Higher nowcast accuracy than baselines; reduced sensitivity to image artifacts and noisy frames; practical inference latency | No explicit eval vs. strong adversarial attacks; transferability across climates/cameras requires fine-tuning |

| Alsubai et al. [146] | IoMT adversarial dataset and digital-twin pipeline; benchmarks CNN/Transformer with adversarial attacks and training | Curated IoMT adversarial dataset (classification tasks) | Reproducible stress tests; significant drops under attack; adversarial training recovers part of the loss; provides baselines/tools | Limited modality/task coverage; compute overhead for strong attacks; needs broader cross-institution validation |

5.2. Generative and Ensemble Intrusion Detection

| Paper | Methodology | Dataset(s) | Main Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Son et al. [150] | Self-Attention Conditional GAN with ensemble classifiers | UNSW-NB15, ToN-IoT, Power system | Strong detection of unseen attacks; improved generalization | Latency/energy on edge not analyzed |

| Khatami et al. [154] | GAN with 5-Dimensional Gray Wolf Optimizer for hyperparameter tuning | NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, IoT-23 | ∼100% detection; reduced false positives | Offline evaluation only; no scalability proof |

| Alwaisi [155] | TinyML anomaly detector (KNN, SVM, NB, RF) for Mirai variants | Real 6G smart-home and industrial testbeds | KNN >99% accuracy with minimal memory | Excludes deep models; limited adaptability |

| Vajrobol et al. [156] | Adversarial training with hybrid LSTM with XGBoost | CICIoT2023 | Accuracy = 97.7%; robust to adversarial samples | High computational overhead |

| Alajaji [157] | Surrogate adversarial training + RONI filtering | CICDDoS2019 | Recovered accuracy under severe attack; reduced false positives | Compute-intensive; DDoS-focused |

| Omara and Kantarci [159] | GAN-based detector for adversarial V2M attacks | V2M edge simulations | Attack Detection Rate up to 92.5%; resilient to adaptive attacks | Synthetic data; untested in real-world edge |

| Morshedi et al. [161] | GAN combined with controlled Gaussian noise for anomaly detection | CICIDS2017 | achieved a high accuracy and recall of 99.88%; lower false negatives on unseen attacks | Evaluated offline only; no IoT/edge deployment |

| Lakshminarayana et al. [163] | sparse regression and PINN for IoT-enabled load-altering attack detection | IEEE-bus smart-grid simulations | 3% error rate; precise attack localization; interpretable fusion | Simulation-based; untested under adaptive adversaries |

5.3. Hardware and Protocol-Level Defenses

| Paper | Methodology | Dataset/Testbed | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bao et al. [164] | CNN-based RF fingerprinting for device ID | RF signal traces | Reveals brittleness of RF-only identifiers under FGSM/PGD | No defense proposed |

| Sánchez et al. [165] | LSTM-CNN with adversarial distillation | Raspberry Pi 4 cluster | F1 = 0.96; attack success reduced 0.88→0.17 | Limited to homogeneous hardware; needs wider validation |

| Cao et al. [167] | Dual-window symmetric authentication (ChaCha20-Poly1305 AEAD) | Hardware, Mininet, ProVerif simulation | 50-step desync recovery; <17 ms latency; 101 J/session | Relies on pre-shared keys; potential side-channel exposure |

| Hemavathy et al. [169] | Lightweight authentication protocol to counter model learning attacks on FPGA PUFs | FPGA (16-, 32-, and 64-bit) | ML attacker success reduced to 50%; lightweight | Not validated under hybrid stress or large-scale deployment |

| Aribilola et al. [170] | Möbius S-box stream cipher | IoT video data on NUC | More secure and efficent than AES-CFB and ChaCha20 | Requires deeper cryptanalysis and multimodal testing |

| Elhajj et al. [171] | Three-layer blockchain for IoT data integrity and access control | UK-DALE and PECAN Street | Energy-efficient; resilient to DoS, Sybil, and MITM; low latency | Requires trusted consortium; scalability limits |

| Alnfiai [174] | Multi-agent RL for dynamic 5G defense orchestration | NS3-based 5G simulation | 95.8% detection; <50 ms mitigation; adaptive learning | Reward poisoning risk; deployment complexity |

| Dong et al. [175] | Multi-layered optimization for adaptive cyber-decoy placement; MADRL and Bayesian inference for evolving attakcs and uncertanties | IEEE 123-bus grid, real PMU traces | 35% better resilience metrics; 40% success rates of attacks decrease | High computation during re-optimization; no hardware-in-loop validation |

5.4. Federated and Distributed Resilience

| Paper | Methodology | Dataset/Testbed | Key Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reis [176] | Edge FL testbed on Jetson Nano and Raspberry Pi | CICIDS2017, TON_IoT | F1-score (>91%); AUC-ROC (>96%); Latency (<20 ms) | No defenses; small-scale |

| Albanbay et al. [177] | DNN, CNN, CNN-BiLSTM profiling on edge nodes | CICIoT2023, Raspberry Pi 5 | CNN: 98% accuracy; CNN-BiLSTM: 99% accuracy | controlled offline settings; reliable devices assumption |

| Shabbir et al. [178] | DFL vs CFL for smart grid forecasting | Hourly Energy Consumption | DFL MAPE < 0.5%, 4.5%, 1%; CFL MAPE >6%, 18%, 10% under poisoning | Simulation-only; no real-world noise |

| Haghbin et al. [180] | GAN-augmented FL with AC-GAN synthesis | MNIST, EMNIST | Best convergence under PGD/FGSM; higher robustness | Not IoT-scale validated; compute cost |

| Al Dalaien et al. [183] | Client ensemble (RF/GBM) + weighted server aggregation | CICIoT-2023 | ∼91% accuracy; moderate cost | Backdoor resistance untested |

| Wang et al. [184] | Adaptive Trimmed Mean aggregation | CICIoV2024, Edge-IIoTset, and ForgeIIOT Pro | >91% accuracy; better than FedAvg, Krum | Added complexity; scalability untested |

| Vinita [188] | Nash bargaining, Shapley-value incentives, AES-GCM | CASA Smart Home, MNIST | +6.5% accuracy, +28% fairness, -39.5% communication | Complex incentive computation; large-scale burden |

| Prasad et al. [189] | Two-tier hybrid optimization (Coati–GWO with CVAE) | RT-IoT2022 | 99.91% accuracy; robust adversarial mitigation | Multi-stage training cost; label dependency |

| ALFahad et al. [190] | Contextual multi-armed bandit node selection | Simulated edge environment | Adaptive, resilient to gradient noise; faster convergence | Requires feedback loop; limited low-power feasibility |

5.5. Trust, Explainability, and Governance

| Paper | Methodology | Dataset/Testbed | Key Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nugraha et al. [191] | Model-agnostic XAI, LIME and ANOVA feature analysis | CICDDoS2019, CICIoT2023, and 5G-PFCP | XGB best accuracy; efficent feature importance method | Limited transfer to multimodal IoT |

| Naik et al. [121] | Context entropy + anomaly/confidence scoring | MIMIC-III, MIT-BIH | F1 = 94.3%; latency <160 ms | Calibration and adaptation remain difficult |

| Majumdar and Awasthi [196] | AI anomaly detection and Hyperledger Fabric ledger | Simulated emergency IoT | Tamper-proof logs; ∼250 ms latency; fewer false positives | Scalability and regulation gaps |

| He et al. [197] | Visualization-driven black-box tuning | UQ-IoT | Improved robustness and interpretability | Degrades on high-dimensional data |

| Al-Fawa’reh et al. [199]) | Semi-supervised latent entropy transformation (VAE and flows) | KDD99, X-IIoTID | High F1 under black-box attacks; OOD detection | Computationally expensive; non-real-time |

| Alasmari et al. [201] | CNN-LSTM, DistilBERT, SHAP for phishing detection | Web and Email datasets (>1.6 M samples) | Accuracy = 98.64%; 41% better transparency | Limited adaptation to new phishing strategies |

| Jin and Lee [30] | Antifragile governance model (conceptual) | Theoretical / literature synthesis | Advocates learning-based resilience and policy evolution | No empirical validation; conceptual only |

6. Case Study: Adversarial Robustness on ToN-IoT

6.1. Dataset and Task

6.2. Model and Training Protocol

6.3. Baseline Performance

6.4. Adversarial Stress Testing

6.5. Adversarial Training and Robustness Gains

7. Challenges and Future Directions

7.1. Cross-Layer and Hybrid-Stressor Integration

7.2. Scalability and Real-World Benchmarking

7.3. Lightweight and Energy-Aware Robustness

7.4. Federated and Decentralized Resilience

7.5. Explainability, Governance, and Human Trust

7.6. Standardization, Ethics, and Societal Readiness

7.7. Toward Antifragile IoT Ecosystems

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abikoye, O.C.; Bajeh, A.O.; Awotunde, J.B.; Ameen, A.O.; Mojeed, H.A.; Abdulraheem, M.; Oladipo, I.D.; Salihu, S.A. Application of internet of thing and cyber physical system in Industry 4.0 smart manufacturing. In Emergence of Cyber Physical System and IoT in Smart Automation and Robotics: Computer Engineering in Automation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zeadally, S.; Bello, O. Harnessing the power of Internet of Things based connectivity to improve healthcare. Internet Things 2021, 14, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenna, A.; Harous, S.; Saidouni, D.E. Internet of things meet internet of threats: New concern cyber security issues of critical cyber infrastructure. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Singh, G. Internet of Vehicles for Sustainable Smart Cities: Opportunities, Issues, and Challenges. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.Z.; Hanapi, Z.M. Efficient secure routing mechanisms for the low-powered IoT network: A literature review. Electronics 2023, 12, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiknas, K.; Taketzis, D.; Demertzis, K.; Skianis, C. Cyber threats to industrial IoT: A survey on attacks and countermeasures. IoT 2021, 2, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntafloukas, K.; McCrum, D.P.; Pasquale, L. A cyber-physical risk assessment approach for internet of things enabled transportation infrastructure. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Yadav, M.; Singh, Y.; Moreira, F. Techniques in reliability of internet of things (IoT). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 256, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.; Sansavini, G.; Kröger, W. Building an integrated metric for quantifying the resilience of interdependent infrastructure systems. In International Conference on Critical Information Infrastructures Security; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Gu, X. Option-based design for resilient manufacturing systems. IFAC-Pap. 2016, 49, 1602–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Barker, K. Modeling infrastructure resilience using Bayesian networks: A case study of inland waterway ports. Comput. & Ind. Eng. 2016, 93, 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Mottahedi, A.; Sereshki, F.; Ataei, M.; Nouri Qarahasanlou, A.; Barabadi, A. The resilience of critical infrastructure systems: A systematic literature review. Energies 2021, 14, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekeraho, A.; Cotfas, D.T.; Balan, T.C.; Cotfas, P.A.; Acheampong, R.; Tuyishime, E. Cybersecurity Threat Modeling for IoT-Integrated Smart Solar Energy Systems: Strengthening Resilience for Global Energy Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Padhy, N.; Sharma, K. Strengthening IoT Resilience: A Study on Backdoor Malware and DNS Spoofing Detection Methods. 2025 International Conference on Emerging Systems and Intelligent Computing (ESIC), 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 795–800. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Ye, D.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, W. Defending Against Neural Network Model Inversion Attacks via Data Poisoning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 16324–16338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fares, S.; Nandakumar, K. Attack to defend: Exploiting adversarial attacks for detecting poisoned models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 24726–24735. [Google Scholar]

- Jarwan, A.; Sabbah, A.; Ibnkahla, M. Information-oriented traffic management for energy-efficient and loss-resilient IoT systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 7388–7403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zheng, L.; Fang, X.; Chen, W.; Fang, K.; Yin, L.; Zhu, H. Pioneering advanced security solutions for reinforcement learning-based adaptive key rotation in Zigbee networks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirne, A.; Sousa, P.R.; Resende, J.S.; Antunes, L. Hardware security for internet of things identity assurance. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 26, 1041–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvaux, J.; Peeters, R.; Gu, D.; Verbauwhede, I. A survey on lightweight entity authentication with strong PUFs. ACM Comput. Surv. 2015, 48, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, C.; Yuan, X.; Li, S.; Zou, S.; Ahmed, S.S.; Ni, W.; Niyato, D.; Jamalipour, A.; Dressler, F.; et al. Zero-trust foundation models: A new paradigm for secure and collaborative artificial intelligence for internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 46269–46293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Alam, M.; Dey, V.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Mukhopadhyay, D. A survey on adversarial attacks and defences. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2021, 6, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Doddapaneni, S.; Khapra, M.M.; Ravindran, B. A survey of adversarial defenses and robustness in nlp. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaqib, M.; Ali, A.; Chen, L.; Nibouche, O. IoT trust and reputation: A survey and taxonomy. J. Cloud Comput. 2023, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Ferreira, M.; Rubio-Hernan, J.; Cavalli, A.; Garcia-Alfaro, J. A survey on cyber-resilience approaches for cyber-physical systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaloopour, L.; Su, Y.; Raskob, F.; Meuser, T.; Bless, R.; Janzen, L.; Abedi, K.; Andjelkovic, M.; Chaari, H.; Chakraborty, P.; et al. Resilience-by-design in 6G networks: Literature review and novel enabling concepts. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 155666–155695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrumaih, T.N.; Alenazi, M.J.; AlSowaygh, N.A.; Humayed, A.A.; Alablani, I.A. Cyber resilience in industrial networks: A state of the art, challenges, and future directions. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.; Eichhammer, P.; Reiser, H.P.; Domaschka, J.; Hauck, F.J.; Habiger, G. A survey on resilience in the iot: Taxonomy, classification, and discussion of resilience mechanisms. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, V.; Mirandola, R.; Perez-Palacin, D. Towards a conceptual characterization of antifragile systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Conference on Software Architecture Companion (ICSA-C), L’Aquila, Italy, 13–17 March 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.; Lee, H. Position: Ai safety must embrace an antifragile perspective. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.13339. [Google Scholar]

- Koç, Y.; Warnier, M.; Van Mieghem, P.; Kooij, R.E.; Brazier, F.M. The impact of the topology on cascading failures in a power grid model. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2014, 402, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, Y.; Raman, A.; Warnier, M.; Kumar, T. Structural vulnerability analysis of electric power distribution grids. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. 2016, 12, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyza, J.; Yusta, J.M. Characterising the security of power system topologies through a combined assessment of reliability, robustness, and resilience. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, J. Parameter space design of robust control systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2003, 25, 1058–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibašić, H. Strategic Resilience and Sustainability Planning: Management Strategies for Sustainable and Climate-Resilient Communities and Organizations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alibašić, H. Hyper-engaged citizenry, negative governance and resilience: Impediments to sustainable energy projects in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 100, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibašić, H. Advancing disaster resilience: The ethical dimensions of adaptability and adaptive leadership in public service organizations. Public Integr. 2025, 27, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghandeh, R.; Von Meier, A.; Mehrmanesh, L.; Mili, L. On the definition of cyber-physical resilience in power systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, H. Resilience of transportation systems: Concepts and comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 4262–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, N.N. Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder; Penguin UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pravin, C.; Martino, I.; Nicosia, G.; Ojha, V. Fragility, robustness and antifragility in deep learning. Artif. Intell. 2024, 327, 104060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Oosthuizen, R.; Sawah, S.E.; Abbass, H. Agile, antifragile, artificial-intelligence-enabled, command and control. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.06874. [Google Scholar]

- Scotti, V.; Perez-Palacin, D.; Brauzi, V.; Grassi, V.; Mirandola, R. Antifragility via Online Learning and Monitoring: An IoT Case Study; Karlsruher Institut für Technologie: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.H. Engineering antifragile systems: A change in design philosophy. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 32, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillson, D. Beyond resilience: Towards antifragility? Contin. Resil. Rev. 2023, 5, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, D.; Anand, B.; Chowdhary, C.L. Digital twin: Exploring the intersection of virtual and physical worlds. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 75152–75172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellios, I.; Kotzanikolaou, P.; Psarakis, M.; Alcaraz, C.; Lopez, J. A survey of iot-enabled cyberattacks: Assessing attack paths to critical infrastructures and services. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 3453–3495. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, D.R.; Midkiff, S.F. Denial-of-service in wireless sensor networks: Attacks and defenses. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2008, 7, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, K.M.; Shams, R.; Khan, F.H.; Luque-Nieto, M.A. Securing underwater wireless sensor networks: A review of attacks and mitigation techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 161096–161133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, Ö.; Aktuğ, S.S.; Ozkan-Okay, M.; Yilmaz, A.A.; Akin, E. A comprehensive review of cyber security vulnerabilities, threats, attacks, and solutions. Electronics 2023, 12, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Cong, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, Q.; Lyu, L.; Liu, J. Data poisoning attacks on federated machine learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 11365–11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Chen, J.; Yu, C.; Ma, J. Poisoning attacks in federated learning: A survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 10708–10722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abroshan, H. AI to protect AI: A modular pipeline for detecting label-flipping poisoning attacks. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2025, 22, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Pan, M.; Just, H.A.; Lyu, L.; Qiu, M.; Jia, R. Narcissus: A practical clean-label backdoor attack with limited information. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Copenhagen, Denmark, 26–30 November 2023; pp. 771–785. [Google Scholar]

- Hanif, M.A.; Chattopadhyay, N.; Ouni, B.; Shafique, M. Survey on Backdoor Attacks on Deep Learning: Current Trends, Categorization, Applications, Research Challenges, and Future Prospects. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 93190–93221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; He, D.; Chen, D. Poisoning attack on load forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE innovative smart grid technologies-Asia (ISGT Asia), Chengdu, China, 21–24 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1230–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, A.; Rassam, M.A. Adversarial machine learning attacks against intrusion detection systems: A survey on strategies and defense. Future Internet 2023, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6572. [Google Scholar]

- Kurakin, A.; Goodfellow, I.J.; Bengio, S. Adversarial examples in the physical world. In Artificial Intelligence Safety and Security; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.06083. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Liao, F.; Pang, T.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Hu, X.; Li, J. Boosting adversarial attacks with momentum. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 9185–9193. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.M.; Fawzi, A.; Frossard, P. Deepfool: A simple and accurate method to fool deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2574–2582. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, J.; Nie, Y. Generation and Countermeasures of adversarial examples on vision: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Han, D.; Lu, C.; Hou, C.; Han, Y.; Hao, X.; Zhang, C. Transferable Targeted Adversarial Attack on Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Image Recognition. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yin, X. You Only Attack Once: Single-Step DeepFool Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 15, 302. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Wu, D.; Cai, T.; Zhu, Y.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Tang, Z.; Li, Y. Deep learning model inversion attacks and defenses: A comprehensive survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, L.; Ding, K.; Gong, N.Z.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, Y. A Systematic Survey of Model Extraction Attacks and Defenses: State-of-the-Art and Perspectives. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.15031. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, H.; Yu, W.; Kong, J.; Chong, B.; Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Xia, Sh.; Xu, K. Privacy leakage on dnns: A survey of model inversion attacks and defenses. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.04013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaweel, A.; Mukkath, H.; Kamel, I. Gps spoofing attacks in fanets: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 55233–55280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswarath, R.P.; Abhishek, N.V.; Sikdar, B. A quantum safe authentication protocol for remote keyless entry systems in cars. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 98th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2023-Fall), Hong Kong, 10–13 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Shen, G.; Saad, W.; Chowdhury, K. Radio frequency fingerprint identification for device authentication in the internet of things. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coston, I.; Plotnizky, E.; Nojoumian, M. Comprehensive Study of IoT Vulnerabilities and Countermeasures. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ardizzon, F.; Piana, M.; Shen, G.; Tomasin, S. Physical Layer-Based Device Fingerprinting For Wireless Security: From Theory To Practice. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 5296–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Resa, A.; Garcia-Bosque, M.; Sánchez-Azqueta, C.; Celma, S. Self-synchronized encryption for physical layer in 10gbps optical links. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2019, 68, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kponyo, J.J.; Agyemang, J.O.; Klogo, G.S.; Boateng, J.O. Lightweight and host-based denial of service (DoS) detection and defense mechanism for resource-constrained IoT devices. Internet Things 2020, 12, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, C. Energy depletion attack against routing protocol in the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2019 16th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–14 January 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Alamri, H.A.; Thayananthan, V. Bandwidth control mechanism and extreme gradient boosting algorithm for protecting software-defined networks against DDoS attacks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 194269–194288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Dai, R.; Zuo, C.; Chen, J.; Li, K.; Qin, Z. A Low-rate DoS Attack Mitigation Scheme Based on Port and Traffic State in SDN. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2025, 74, 1758–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikwar, M.; Gligoroski, D. Non-interactive vdf client puzzle for dos mitigation. In Proceedings of the 2021 European Interdisciplinary Cybersecurity Conference, Virtual, 10–11 November 2021; pp. 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Arabas, P.; Dawidiuk, M. Filter aggregation for DDoS prevention systems: Hardware perspective. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2025, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, P.; Singh, Y.; Anand, P.; Bangotra, D.K.; Singh, P.K.; Hong, W.C. Internet of things: Evolution, concerns and security challenges. Sensors 2021, 21, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelantado, F.; Vilajosana, X.; Tuset-Peiro, P.; Martinez, B.; Melia-Segui, J.; Watteyne, T. Understanding the limits of LoRaWAN. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, B.; Khriji, S.; Chéour, R.; Lahoud, C.; Moessner, K.; Kanoun, O. Improving the reliability of long-range communication against interference for non-line-of-sight conditions in industrial Internet of Things applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, A. Security Analysis of Rolling Code-based Remote Keyless Entry Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Csikor, L.; Lim, H.W.; Wong, J.W.; Ramesh, S.; Parameswarath, R.P.; Chan, M.C. Rollback: A new time-agnostic replay attack against the automotive remote keyless entry systems. ACM Trans. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2024, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunoda, Y.; Fujiwara, Y. The Asymptotics of Difference Systems of Sets for Synchronization and Phase Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), Taipei, Taiwan, 25–30 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 678–683. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Chen, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Shen, H.; Bian, Y.; Lu, Y.; Ruan, Z.; Li, B.; et al. Fast and Scalable Selective Retransmission for RDMA. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2025-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, London, UK, 19–22 May 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, F.; Wu, M.; Zhai, A.; Zhang, Z.L. Interleaved Function Stream Execution Model for Cache-Aware High-Speed Stateful Packet Processing. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 44th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Jersey City, NJ, USA, 23–26 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 531–542. [Google Scholar]

- Qadri, Y.A.; Jung, H.; Niyato, D. Toward the Internet of Medical Things for Real-Time Health Monitoring Over Wi-Fi. IEEE Netw. 2024, 38, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, M.K.; Pati, A.; Mishra, S.K.; Appasani, B.; Kabalci, E.; Bizon, N.; Thounthong, P. A comprehensive review of the evolution of networked control system technology and its future potentials. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Qi, P.; Wang, D.; Li, Z. On the anti-interference tolerance of cognitive frequency hopping communication systems. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2020, 69, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dai, W.; Sun, J.; Xu, Z.; Li, G.Y. Uncertainty awareness in wireless communications and sensing. In IEEE Communications Magazine; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Reinfurt, L.; Breitenbücher, U.; Falkenthal, M.; Leymann, F.; Riegg, A. Internet of things patterns. In Proceedings of the 21st European Conference on Pattern Languages of programs, Irsee, Germany, 6–10 July 2016; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Agrawal, N. EDMA-RM: An Event-Driven and Mobility-Aware Resource Management Framework for Green IoT-Edge-Fog-Cloud Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 23004–23012. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kadhim, H.M.; Al-Raweshidy, H.S. Energy efficient data compression in cloud based IoT. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 12212–12219. [Google Scholar]

- Sabovic, A.; Aernouts, M.; Subotic, D.; Fontaine, J.; De Poorter, E.; Famaey, J. Towards energy-aware tinyML on battery-less IoT devices. Internet Things 2023, 22, 100736. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, N.; Acar, A.; Aris, A.; Uluagac, A.S.; Gungor, V.C. Energy consumption of on-device machine learning models for IoT intrusion detection. Internet Things 2023, 21, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MeasureX. Understanding Pressure Sensor Drift: Causes, Effects & How to Prevent It. 25 August 2025. Available online: https://www.measurex.com.au (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Sutar, S.; Raha, A.; Raghunathan, V. Memory-based combination PUFs for device authentication in embedded systems. IEEE Trans. Multi-Scale Comput. Syst. 2018, 4, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, R.; Jain, S. Adaptive recalibration algorithm for removing sensor errors and its applications in motion tracking. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 2916–2924. [Google Scholar]

- Kusters, C.J. Helper Data Schemes for Secret-Key Generation Based on Sram Pufs: Bias & Multiple Observations; Technische Universiteit Eindhoven: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karpinskyy, B.; Lee, Y.; Choi, Y.; Kim, Y.; Noh, M.; Lee, S. 8.7 Physically unclonable function for secure key generation with a key error rate of 2E-38 in 45nm smart-card chips. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 31 January–4 February 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Shami, A. IoT data analytics in dynamic environments: From an automated machine learning perspective. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 116, 105366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, M. Nonlinear autoregressive prediction model for VAWT power supply network energy management. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 5446–5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shami, A. A lightweight concept drift detection and adaptation framework for IoT data streams. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2021, 4, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Manias, D.M.; Shami, A. Pwpae: An ensemble framework for concept drift adaptation in iot data streams. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference (Globecom), Madrid, Spain, 7–11 December 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, B.B.; Quamara, M. An overview of Internet of Things (IoT): Architectural aspects, challenges, and protocols. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2020, 32, e4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, F.; Esposito, C. Efficient PUF-Based IoT Authentication Framework without Fuzzy Extractor. In Proceedings of the 40th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing, Sicily, Italy, 31 March–4 April 2025; pp. 695–704. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qaisi, A.; Aldahdouh, K.; Al-Sit, W.T.; Olaimat, A.A.; Alouneh, S.; Darabkh, K.A. Low Power Wide Area Network (LPWAN) Protocols: Enablers for Future Wireless Networks. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, R.; da Silva, L.; Santos, W.; Souza, M. Cognitive Radio Strategy Combined with MODCOD Technique to Mitigate Interference on Low-Orbit Satellite Downlinks. Sensors 2023, 23, 7234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burhan, M.; Rehman, R.A.; Khan, B.; Kim, B.S. IoT elements, layered architectures and security issues: A comprehensive survey. sensors 2018, 18, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, Z.; Zakaria, M.; Hassan, R. An enhanced ensemble defense framework for boosting adversarial robustness of intrusion detection systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.; Yong, K.S.C.; Lau, B.T.; Tan, C.C.L. Future of generative adversarial networks (GAN) for anomaly detection in network security: A review. Comput. Secur. 2024, 139, 103733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Lin, X.; Li, S.; Peng, H.; Zhang, B. Global or local adaptation? Client-sampled federated meta-learning for personalized IoT intrusion detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 20, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, W.; Vlaski, S.; Ling, Q. Mean aggregator is more robust than robust aggregators under label poisoning attacks on distributed heterogeneous data. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2025, 26, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Erazo-Garzón, L.; Cedillo, P.; Rossi, G.; Moyano, J. A domain-specific language for modeling IoT system architectures that support monitoring. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 61639–61665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajewska, E.; Mikołajewski, D.; Mikołajczyk, T.; Paczkowski, T. Generative AI in AI-based digital twins for fault diagnosis for predictive maintenance in Industry 4.0/5.0. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiasari, M.; Ghaffari, M.; Aly, H.H. A comprehensive review of the current status of smart grid technologies for renewable energies integration and future trends: The role of machine learning and energy storage systems. Energies 2024, 17, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulothungan, V. Using Blockchain Ledgers to Record AI Decisions in IoT. IoT 2025, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla, P.; Berríos, S.; Allende-Cid, H. Explainable AI for Forensic Analysis: A Comparative Study of SHAP and LIME in Intrusion Detection Models. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, N.; Surendranath, N.; Raju, S.A.B.; Madduri, C.; Dasari, N.; Shukla, V.K.; Patil, V. Hybrid deep learning-enabled framework for enhancing security, data integrity, and operational performance in Healthcare Internet of Things (H-IoT) environments. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31039. [Google Scholar]

- Saranya, A.; Subhashini, R. A systematic review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence models and applications: Recent developments and future trends. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 7, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Yang, M.; Cozzani, V. Enhancing pipeline system resilience: A reliability-centric approach. J. Pipeline Sci. Eng. 2024, 5, 100252. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulhussain, S.H.; Mahmmod, B.M.; Alwhelat, A.; Shehada, D.; Shihab, Z.I.; Mohammed, H.J.; Abdulameer, T.H.; Alsabah, M.; Fadel, M.H.; Ali, S.K.; et al. A comprehensive review of sensor technologies in IOT: Technical aspects, challenges, and future directions. Computers 2025, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Gao, M.; Yuan, W.; Ye, G.; Sadiq, S.; Yin, H. Poisoning attacks and defenses in recommender systems: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.01022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Sagduyu, Y.E. Evasion and causative attacks with adversarial deep learning. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2017—2017 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), Baltimore, MA, USA, 23–25 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.; Jang, D.J.; Lee, E.K. Adversarial Evasion Attacks on SVM-Based GPS Spoofing Detection Systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Pal, S.; Fallah, A.; Doss, R.; Karmakar, C. RAD-IoMT: Robust adversarial defense mechanisms for IoMT medical image analysis. Ad. Hoc. Netw. 2025, 178, 103935. [Google Scholar]

- Kermany, D. Labeled Optical Coherence Tomography (oct) and Chest X-Ray Images for Classification. Mendeley Data. 2018. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Gungor, O.; Rosing, T.; Aksanli, B. Stewart: Stacking ensemble for white-box adversarial attacks towards more resilient data-driven predictive maintenance. Comput. Ind. 2022, 140, 103660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosello, M. UNIBO Powertools Dataset. 2021. Available online: https://cris.unibo.it (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Lambotharan, S.; Zheng, G.; Liao, G.; Liu, X.; Roli, F.; Maple, C. Vision Transformer with Adversarial Indicator Token against Adversarial Attacks in Radio Signal Classifications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 35367–35379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyane, A.; Jamiri, H. Securing IoT Networks with Adversarial Learning: A Defense Framework Against Cyber Threats. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (IRASET), Dhar El Mahraz Fez, Morocco, 15–16 May 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, E.C.P.; Dadkhah, S.; Ferreira, R.; Zohourian, A.; Lu, R.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoT2023: A real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in IoT environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efatinasab, E.; Brighente, A.; Donadel, D.; Conti, M.; Rampazzo, M. Towards robust stability prediction in smart grids: GAN-based approach under data constraints and adversarial challenges. Internet Things 2025, 33, 101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzamasov, V. Electrical grid stability simulated data. UCI Mach. Learn. Repos. 2018, 10, C5PG66. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, H.; El-Sappagh, S.; Abuhmed, T. Robustness in deep learning models for medical diagnostics: Security and adversarial challenges towards robust AI applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 58, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Papernot, N.; McDaniel, P.D.; Feinman, R.; Faghri, F.; Matyasko, A.; Sheatsley, R. Cleverhans v0.1: An adversarial machine learning library. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.0076817. [Google Scholar]

- Papernot, N.; Goodfellow, I.; Sheatsley, R.; Feinman, R.; McDaniel, P. cleverhans v2.0.0: An adversarial machine learning library. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.0076810. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam, P.S.; Vaziri, A.; Khatami, S.S.; Hernando-Gallego, F.; Martín, D. Generative Adversarial and Transformer Network Synergy for Robust Intrusion Detection in IoT Environments. Future Internet 2025, 17, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaedi, A.; Moustafa, N.; Tari, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Anwar, A. TON_IoT telemetry dataset: A new generation dataset of IoT and IIoT for data-driven intrusion detection systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 165130–165150. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Konstantinou, C. Adversarial attack and defense methods for neural network based state estimation in smart grid. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 3507–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Pinson, P.; Fan, S. Global energy forecasting competition 2012. Int. J. Forecast. 2014, 30, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusher, A.S.; Rahman, M.A.; Islam, M.R.; Bosak, S.; Hossain, M.J. FEMUS-Nowcast: A Robust Deep Learning Model for Sky Image–Based Short-Term Solar Forecasting Under Adversarial Attacks. Int. J. Energy Res. 2025, 2025, 8286945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Li, X.; Scott, A.; Sun, Y.; Venugopal, V.; Brandt, A. SKIPP’D: A SKy Images and Photovoltaic Power Generation Dataset for short-term solar forecasting. Sol. Energy 2023, 255, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Alsubai, S.; Karovič, V.; Almadhor, A.; Hejaili, A.A.; Juanatas, R.A.; Sampedro, G.A. Future-Proofing AI Models in IoMT Environment: Adversarial Dataset Generation and Defense Strategies. Digit. Twins Appl. 2025, 2, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hady, A.A.; Ghubaish, A.; Salman, T.; Unal, D.; Jain, R. Intrusion detection system for healthcare systems using medical and network data: A comparison study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 106576–106584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’shea, T.J.; West, N. Radio machine learning dataset generation with gnu radio. GNU Radio Conf. 2016, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, S.; Gao, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z. Automatic modulation classification: Cauchy-Score-function-based cyclic correlation spectrum and FC-MLP under mixed noise and fading channels. Digit. Signal Process. 2022, 126, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, N.K.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Medhane, D.V.; Alenazi, M.J.; Aborokbah, M. Enhancing Resilience in Edge IoT Devices Against Adversarial Attacks. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2024, 14, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N.; Slay, J. UNSW-NB15: A comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). In Proceedings of the 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS), Canberra, Australia, 10–12 November 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa, N. New generations of internet of things datasets for cybersecurity applications based machine learning: TON_IoT datasets. In Proceedings of the eResearch Australasia Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 22–24 October 2019; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hink, R.C.B.; Beaver, J.M.; Buckner, M.A.; Morris, T.; Adhikari, U.; Pan, S. Machine learning for power system disturbance and cyber-attack discrimination. In Proceedings of the 2014 7th International Symposium on Resilient Control Systems (ISRCS), Denver, CO, USA, 19–21 August 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Khatami, S.S.; Shoeibi, M.; Oskouei, A.E.; Martin, D.; Dashliboroun, M.K. 5DGWO-GAN: A Novel Five-Dimensional Gray Wolf Optimizer for Generative Adversarial Network-Enabled Intrusion Detection in IoT Systems. Computers. Mater. Contin. 2025, 82, 881–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwaisi, Z. Memory-efficient and robust detection of Mirai botnet for future 6G-enabled IoT networks. Internet Things 2025, 32, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajrobol, V.; Gupta, B.B.; Gaurav, A.; Chuang, H.M. Adversarial learning for Mirai botnet detection based on long short-term memory and XGBoost. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 2024, 5, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajaji, A. FortiNIDS: Defending Smart City IoT Infrastructures Against Transferable Adversarial Poisoning in Machine Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Lashkari, A.H.; Hakak, S.; Ghorbani, A.A. Developing realistic distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack dataset and taxonomy. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology (ICCST), Chennai, India, 1–3 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Omara, A.; Kantarci, B. An AI-driven solution to prevent adversarial attacks on mobile Vehicle-to-Microgrid services. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2024, 137, 103016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.; Ott, M.; Friedli, M.; Rumsch, A.; Paice, A. Residential power traces for five houses: The ihomelab rapt dataset. Data 2020, 5, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Morshedi, R.; Matinkhah, S.M. Combining Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) With Gaussian Noise for Anomaly Detection in Internet of Things (IoT) Traffic. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Lashkari, A.H.; Ghorbani, A.A. Toward generating a new intrusion detection dataset and intrusion traffic characterization. ICISSp 2018, 1, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarayana, S.; Sthapit, S.; Jahangir, H.; Maple, C.; Poor, H.V. Data-driven detection and identification of IoT-enabled load-altering attacks in power grids. IET Smart Grid 2022, 5, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Mao, S. Threat of adversarial attacks on DL-based IoT device identification. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 9012–9024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.M.S.; Celdrán, A.H.; Bovet, G.; Pérez, G.M. Adversarial attacks and defenses on ML-and hardware-based IoT device fingerprinting and identification. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 152, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P.M.S.; Valero, J.M.J.; Celdrán, A.H.; Bovet, G.; Pérez, M.G.; Pérez, G.M. LwHBench: A low-level hardware component benchmark and dataset for Single Board Computers. Internet Things 2023, 22, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Kou, M.; Lai, Y.; Mei, Z. S²-Code: A Resilient and Lightweight Self-Synchronizing Authentication Protocol for Unreliable IoT Networks. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 156153–156169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, B.; Smyth, B.; Cheval, V.; Sylvestre, M. ProVerif 2.00: Automatic cryptographic protocol verifier, user manual and tutorial. 2018, 16, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hemavathy, S.; Bhaaskaran, V.K. Arbiter PUF—A review of design, composition, and security aspects. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 33979–34004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aribilola, I.; Lee, B.; Asghar, M.N. Möbius transformation and permutation based S-box to enhance IOT multimedia security. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 140792–140808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhajj, M.; Attar, A.E.; Mikati, A. Integrating IoT and blockchain for smart urban energy management: Enhancing sustainability through real-time monitoring and optimization. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Knottenbelt, W. The UK-DALE dataset, domestic appliance-level electricity demand and whole-house demand from five UK homes. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borst, T.W. Aggregation of energy consumption forecasts across spatial levels. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alnfiai, M.M. AI-powered cyber resilience: A reinforcement learning approach for automated threat hunting in 5G networks. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2025, 2025, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wei, Z.; Peiyi, C.; Yiqing, L.; Hua, H. Multi-Layered Optimization for Adaptive Decoy Placement in Cyber-Resilient Power Systems Under Uncertain Attack Scenarios. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2025, 19, e70078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.J. Edge-FLGuard: A Federated Learning Framework for Real-Time Anomaly Detection in 5G-Enabled IoT Ecosystems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanbay, N.; Tursynbek, Y.; Graffi, K.; Uskenbayeva, R.; Kalpeyeva, Z.; Abilkaiyr, Z.; Ayapov, Y. Federated learning-based intrusion detection in IoT networks: Performance evaluation and data scaling study. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, A.; Manzoor, H.U.; Manzoor, M.N.; Hussain, S.; Zoha, A. Robustness against data integrity attacks in decentralized federated load forecasting. Electronics 2024, 13, 4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, R. Hourly Energy Consumption. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Haghbin, Y.; Badiei, M.H.; Tran, N.H.; Piran, M.J. Resilient Federated Adversarial Learning With Auxiliary-Classifier GANs and Probabilistic Synthesis for Heterogeneous Environments. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2025, 22, 4998–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L. The mnist database of handwritten digit images for machine learning research [best of the web]. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2012, 29, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Afshar, S.; Tapson, J.; Van Schaik, A. EMNIST: Extending MNIST to handwritten letters. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Anchorage, AK, USA, 2017, May; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 2921–2926. [Google Scholar]

- Al Dalaien, M.; Ullah, R.; Al-Haija, Q.A. A Dual-Aggregation Approach to Fortify Federated Learning Against Poisoning Attacks in IoTs. Array 2025, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukisa, K.J.; Ahakonye, L.A.C.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.M. Blockchain-Augmented FL IDS for Non-IID Edge-IoT Data Using Trimmed Mean Aggregation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 45150–45159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, E.C.P.; Taslimasa, H.; Dadkhah, S.; Iqbal, S.; Xiong, P.; Rahman, T.; Ghorbani, Ali A. CICIoV2024: Advancing realistic IDS approaches against DoS and spoofing attack in IoV CAN bus. Internet Things 2024, 26, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, M.A.; Friha, O.; Hamouda, D.; Maglaras, L.; Janicke, H. Edge-IIoTset: A new comprehensive realistic cyber security dataset of IoT and IIoT applications for centralized and federated learning. IEEe Access 2022, 10, 40281–40306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Mullick, S.; Das, R.; Nandi, A.; Banerjee, I. IoTForge Pro: A security testbed for generating intrusion dataset for industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 8453–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinita, J. An incentive-aware federated bargaining approach for client selection in decentralized federated learning for IoT smart homes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34412. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, K.S.; Udayakumar, P.; Laxmi Lydia, E.; Ahmed, M.A.; Ishak, M.K.; Karim, F.K.; Mostafa, S.M. A two-tier optimization strategy for feature selection in robust adversarial attack mitigation on internet of things network security. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ALFahad, S.; Parambath, S.P.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Kolomvatsos, K. Node selection using adversarial expert-based multi-armed bandits in distributed computing. Computing 2025, 107, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, B.; Jnanashree, A.V.; Bauschert, T. A versatile XAI-based framework for efficient and explainable intrusion detection systems. Ann. Telecommun. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St, L.; Wold, S. Analysis of variance (ANOVA). Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1989, 6, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponis, G.; Radoglou-Grammatikis, P.; Nakas, G.; Goudos, S.; Argyriou, V.; Lagkas, T.; Sarigiannidis, P. 5G core PFCP intrusion detection dataset. In Proceedings of the 2023 12th International Conference on Modern Circuits and Systems Technologies (MOCAST), Athens, Greece, 28–30 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.E.; Pollard, T.J.; Shen, L.; Lehman, L.W.H.; Feng, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Moody, B.; Szolovits, P.; Celi, L.A.; Mark, R.G. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, G.B.; Mark, R.G. The impact of the MIT-BIH arrhythmia database. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 2001, 20, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, S.; Awasthi, A. From vulnerability to resilience: Securing public safety GPS and location services with smart radio, blockchain, and AI-driven adaptability. Electronics 2025, 14, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Kim, D.D.; Asghar, M.R. NIDS-Vis: Improving the generalized adversarial robustness of network intrusion detection system. Comput. Secur. 2024, 145, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Kim, D.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, M.; Lam, U.; Yu, J. UQ IoT IDS Dataset 2021; The University of Queensland: Brisbane City, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fawa’reh, M.; Abu-Khalaf, J.; Janjua, N.; Szewczyk, P. Detection of on-manifold adversarial attacks via latent space transformation. Comput. Secur. 2025, 154, 104431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawawreh, M.; Sitnikova, E.; Aboutorab, N. X-IIoTID: A connectivity-agnostic and device-agnostic intrusion data set for industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 3962–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmari, S.M.; Sakly, H.; Kraiem, N.; Algarni, A. Phishing detection in IoT: An integrated CNN-LSTM framework with explainable AI and LLM-enhanced analysis. Discov. Internet Things 2025, 5, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiew, K.L.; Tan, C.L.; Wong, K.; Yong, K.S.; Tiong, W.K. A new hybrid ensemble feature selection framework for machine learning-based phishing detection system. Inf. Sci. 2019, 484, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, C.; Chen, Y.; Wei, B. Look before you leap: Detecting phishing web pages by exploiting raw URL and HTML characteristics. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K. Malicious and benign webpages dataset. Data Brief 2020, 32, 106304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannousse, A.; Yahiouche, S. Towards benchmark datasets for machine learning based website phishing detection: An experimental study. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 104, 104347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey | Primary Scope | Layers Covered | Adversarial ML Depth | IoT Constraints Considered | What Our Survey Adds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chakraborty et al. [22] | General ML (vision and speech) | Model level | High (attacks and defenses taxonomy) | Low (domain-agnostic) | IoT-specific datasets and testbeds, cross-layer integration, deployability on constrained devices |

| Goyal et al. [23] | Text and NLP | Model, data | High (text attacks and defenses) | Low (NLP-centric) | Non-text IoT data (traffic, RF, images), cross-layer coupling to protocols and hardware |

| Aaqib et al. [24] | Trust and reputation systems | Application and governance | Low (conceptual) | Medium (trust overheads) | Bridges trust controllers and XAI with adversarial defenses and edge feasibility |

| Segovia-Ferreira et al. [25] | CPS resilience phases | System and architecture | Medium (anomaly) | Medium (CPS ops focus) | Latest adversarial and federated IoT methods, dataset-driven comparisons |

| Khaloopour et al. [26] | 6G network resilience | Network and service mgmt | Low (device learning) | Medium (6G orchestration) | Links radio and edge learning defenses to protocol and hardware anchors for IoT |

| Alrumaih et al. [27] | Industrial IoT (IIoT) | Network and ops | Low–Medium (anomaly) | High (industrial constraints) | Industrial adversarial ensembles, robust FL, deployability analysis |

| Berger et al. [28] | General IoT resilience | Multi-layer (high level) | Low–Medium (pre-2022 focus) | Medium (broad) | Updated 2022–2025 coverage, paper-by-paper summaries, five-section taxonomy |

| Ours | IoT resilience 2022–2025 | Hardware → Governance | High (DL and ViT, GAN, FL, certified trends) | High (latency, energy, thermal, radio noise, packet loss) | Unified cross-layer synthesis, testbed-aware analysis, actionable gaps and roadmap |

| Property | Definition | Typical Metric | Example in IoT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robustness | Withstands bounded disturbances | Deviation in accuracy or service under fixed faults or noise | Sensor fusion tolerant to up to 10% packet loss |

| Resilience | Recovers or adapts after disruptions | Area under resilience curve, time to recovery | Intrusion detector recovers accuracy after network attack |

| Antifragility | Improves through exposure to shocks | Increase in performance after perturbation, negative regret | intrusion detection system (IDS) that becomes more accurate after adversarial training with real attack traffic |

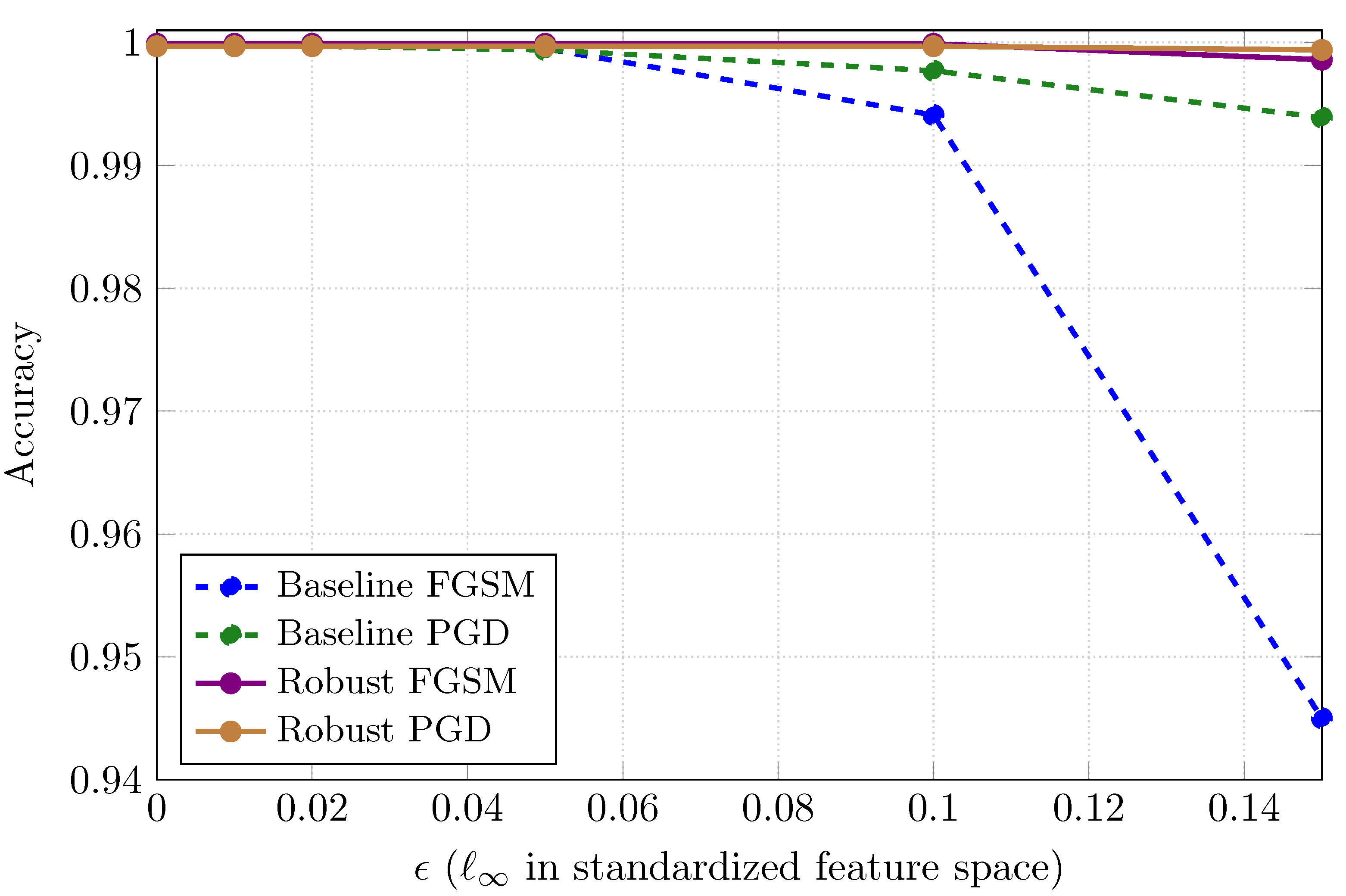

| FGSM Accuracy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| Baseline | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 0.9995 | 0.9941 | 0.9450 |

| Robust | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 0.9986 |

| PGD Accuracy | ||||||

| Model | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| Baseline | 0.9997 | 0.9997 | 0.9997 | 0.9994 | 0.9977 | 0.9939 |

| Robust | 0.9997 | 0.9997 | 0.9997 | 0.9997 | 0.9997 | 0.9994 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).