Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Target | Reagent | Clinical trial description | Trial number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

JAK/STAT |

Ruxolitinib Ruxolitinib Ruxolitinib Tacrolimus + Ruxolitinib + Methotrexate Itacitinib Itacitinib + PTCy Baricitinib Belumosudil Belumosudil |

Phase 2 single-arm trial in SR-aGvHD; 55% ORR at day 28, 73% best ORR, durable responses, manageable safety profile. Phase III trial in SR-aGvHD; higher day-28 ORR with ruxolitinib vs BAT (62% vs 39%) and durable responses. Phase III randomized trial in SR-cGvHD; superior week-24 ORR vs BAT (50% vs 26%), durable responses, manageable safety. Phase III, randomized trial in allo-PBSC transplant; 24-month GVHD-free survival, aiming to assess whether addition of ruxolitinib to standard prophylaxis improves long-term GVHD control. Phase 1, open-label trial in steroid-naïve and SR aGVHD; Day-28 ORR 79% (200 mg) and 67% (300 mg); manageable safety profile with diarrhea and anemia. Open-label Phase 1 study; low-grade CRS (0–1), no ≥grade 2 CRS; 1-year OS ~80%, NRM ~8%, 1-year moderate/severe cGvHD ~5%. Phase 1/2 study in SR cGvHD; manageable neutropenia/infections, 6-month ORR ~63%, best overall response ~90%, durable at 12 months, steroid-sparing, preserves GvL activity. Phase IIa, open-label dose-finding trial in cGvHD; ORR 65–69%, QoL improvement, corticosteroid reduction, mild cytopenias. Phase II randomized trial in heavily pretreated cGvHD; ORR ~74% (QD) and ~77% (BID) with durable and well-tolerated responses. |

NCT02953678 (REACH1) NCT02913261 (REACH2) NCT03112603 (REACH3) NCT06615050 (BMT CTN 2203) NCT02614612 NCT03755414 NCT02759731 NCT02841995 NCT03640481 |

[48] [28] [47] [52] [155] [51] [38] [30] |

|

BTK/ITK |

Ibrutinib | Multi-center, single-arm study in SR- cGvHD, ORR 67%, durable responses; improved quality of life; led to FDA approval |

NCT02195869 | [29,67] |

|

LYN/SYK |

Fostamatinib (R788) | Phase I study for prophylaxis and treatment of cGvHD after allo-HCT, ORR ≈ 77 %; median duration ~19.3 months; steroid-dose reduced by ~80 % |

NCT02611063 | [85] |

|

PI3K/AKT/mTOR |

Sirolimus+ Tacrolimus + Methotrexate Sirolimus + Tacrolimus ± Methotrexate |

Phase II RCT, RIC allo-HCT in lymphoma; reduced grade II–IV aGvHD 9% vs 25%, no increased overall toxicity Phase II RCT, RIC allo-HSCT with HLA-mismatched; cumulative incidence of grade II–IV aGvHD 36% vs historical ~70%, preserved GvL, no added toxicity |

NCT00928018 NCT01251575 |

[78] [77] |

|

NFAT |

Tacrolimus (FK506) + Methotrexate Cyclosporine A + Methotrexate |

Phase III RCT for aGvHD prophylaxis after allo-HSCT; Reduced grade II–IV aGvHD (17.5%) vs cyclosporine (48%) Phase III trial for aGvHD prophylaxis after allo-BMT; with long-term follow-up demonstrating sustained survival and cGvHD incidence over several years |

|

[100] [99] |

|

NF-κB |

Bortezomib + prednisone Bortezomib |

Single-arm Phase II in SR-cGvHD; ORR ≈ ~80% at 15 wks; steroid-sparing; responses in multiple organ sites; tolerable/expected toxicity profile. Phase I/II, prospective treatment in SR-cGvHD; manageable safety and tolerability; evidence of clinical activity |

NCT00815919 NCT01672229 |

[108] [106] |

| BAT, best available therapy; CR, complete response; GFS, GvHD-free survival; GRFS, GvHD/relapse-free survival; MMF, mycophenolic acid; NRM, non-relapse mortality; OS, overall survival; ORR, overall response rate; ROM, range of motion; MMUD, mismatched unrelated donor; Tac/MTX/Rux, tacrolimus/ methotrexate/ ruxolitinib; PTCy/Tac/MMF, post-transplant cyclophosphamide/ tacrolimus/ mycophenolate mofetil; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; QoL, quality of life; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning. | ||||

2. Methodology of Literature Selection

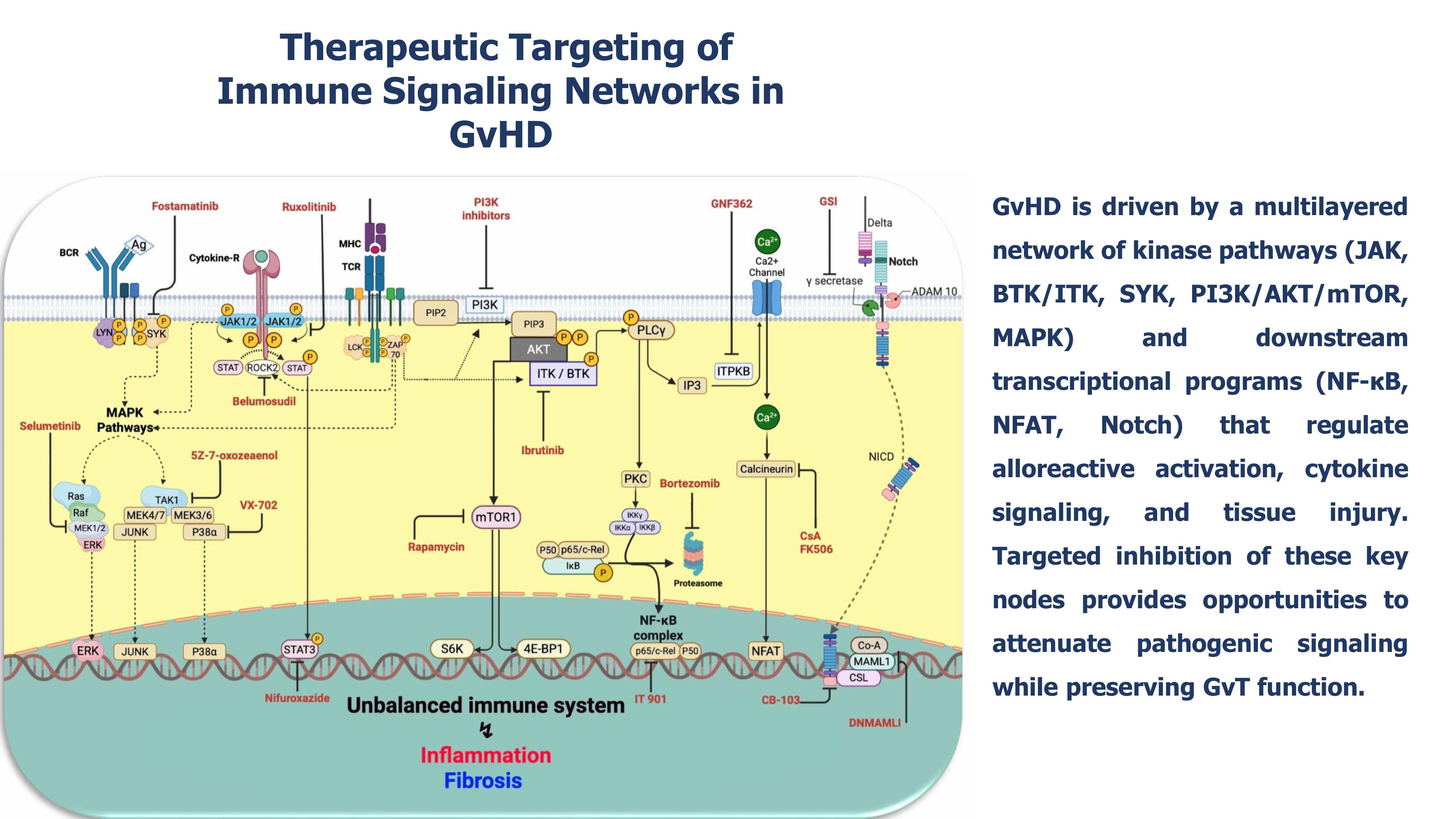

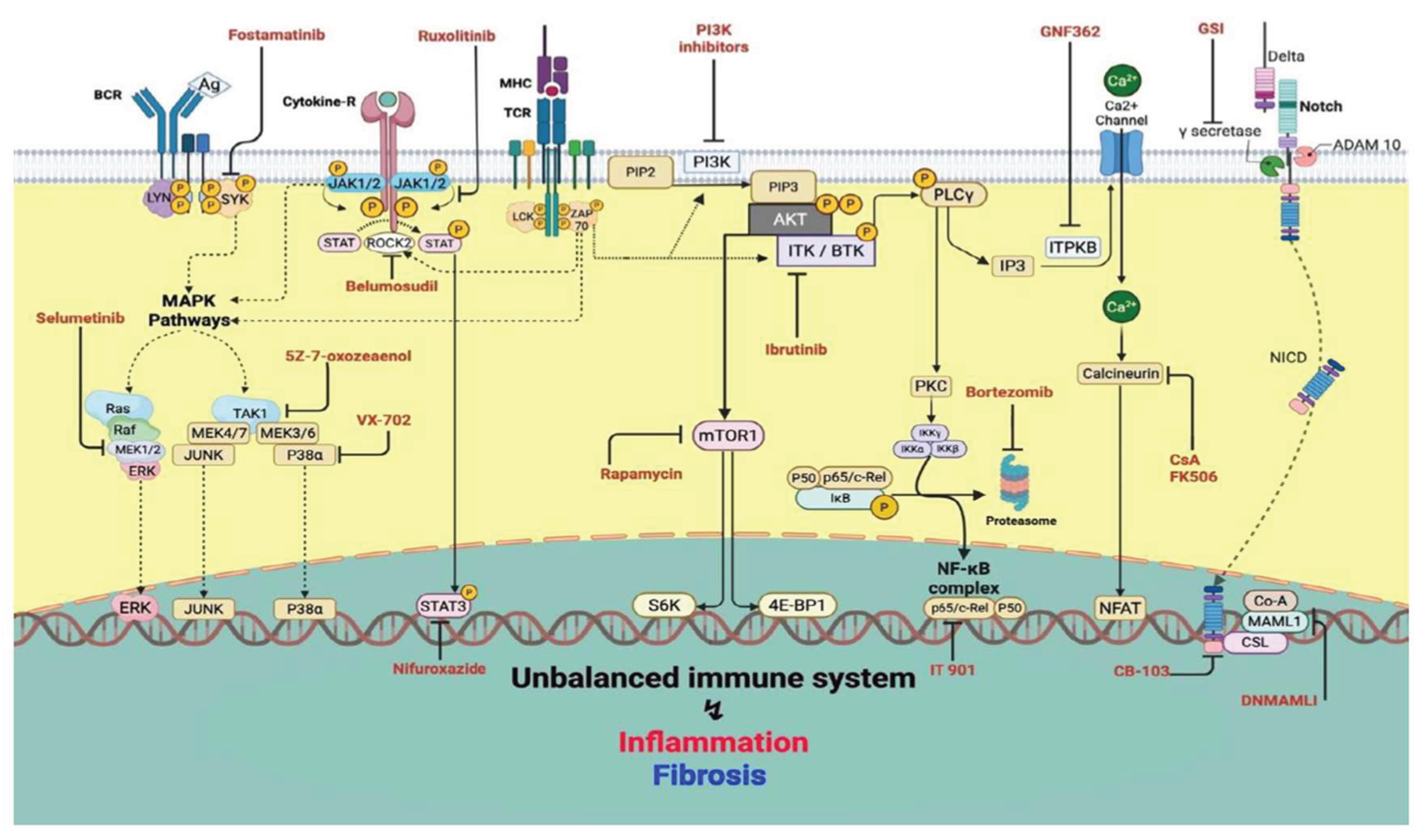

3. Mechanistic Signaling Pathways Underlying GvHD

3.1. Therapeutic Targeting of Central Signaling Pathways in GvHD

3.1.1. JAK/STAT

3.1.2. BTK/ITK

3.1.3. PI3K/AKT/mTOR

3.1.4. LYN/SYK

3.1.5. MAPK

3.1.6. NFAT

3.1.7. NF-κB

3.1.8. Notch

3.2. Other Signaling Pathways

4. Future Therapeutic Directions

4.1. Data-driven discovery of actionable signaling nodes

4.2. Computational prioritization using AI-driven modeling and immune digital twins

4.3. Precision genome engineering for pathway-level modulation

4.4. Closed-loop experimental validation using single-cell perturbation platforms

4.5. Translational roadmap: integrating safety, specificity, and immunological fidelity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| allo-HSCT | allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| GvHD | graft-versus-host disease |

| GvT | graft-versus-tumor |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| STAT | signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| BTK | Bruton’s tyrosine kinase |

| ITK | interleukin-2–inducible T-cell kinase |

| ROCK2 | Rho-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase 2 |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| CRISPR | clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

References

- Pidala, J; Onstad, L; Carpenter, P; Hamilton, BK; Kitko, CL; Juckett, M; et al. Longitudinal study of late acute and chronic GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: A long-term follow up study from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Transplant Cell Ther [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666636725015313.

- Arai, S; Arora, M; Wang, T; Spellman, SR; He, W; Couriel, DR; et al. Increasing incidence of chronic graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic transplantation: a report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015, 21(2), 266–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, GR; Betts, BC; Tkachev, V; Kean, LS; Blazar, BR. Current concepts and advances in graft-versus-host disease immunology. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021, 39(1), 19–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malard, F; Holler, E; Sandmaier, BM; Huang, H; Mohty, M. Acute graft-versus-host disease. Nat Rev Dis Primer 2023, 9(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, R; Blazar, BR. Acute graft-versus-host disease—biologic process, prevention, and therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377(22), 2167–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manduzio, P. Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease: A concise review. Hematol Rep. 2018, 10(4), 7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, NV; Porter, DL. Graft-versus-host disease after donor leukocyte infusions: presentation and management. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2008, 21(2), 205–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Z; Niu, S; Fang, Y; Chen, Y; Li, YR; Yang, L. Addressing graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic cell-based immunotherapy for cancer. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2025, 14(1), 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrin, E; Loren, AW; Falk, SJ; Mays, JW; Cowen, EW. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Part I: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024, 90(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, ME; Inamoto, Y; Carpenter, PA; Lee, SJ; Kiem, HP; Petersdorf, EW; et al. Comparative analysis of risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease and for chronic graft-versus-host disease according to National Institutes of Health consensus criteria. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2011, 117(11), 3214–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, R; Blazar, BR. Pathophysiology of chronic graft-versus-host disease and therapeutic targets. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377(26), 2565–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socié, G; Ritz, J. Current issues in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2014, 124(3), 374–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtan, SG; Pasquini, M; Weisdorf, DJ. Acute graft-versus-host disease: a bench-to-bedside update. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2014, 124(3), 363–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castor, MGM; Pinho, V; Teixeira, MM. The role of chemokines in mediating graft versus host disease: opportunities for novel therapeutics. Front Pharmacol. 2012, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, T; Hashimoto, D. Novel Insights Into the Mechanism of GVHD-Induced Tissue Damage. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 713631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T; Liu, L; Jiang, W; Zhou, R. DAMP-sensing receptors in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020, 20(2), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, GR; Koyama, M. Cytokines and costimulation in acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2020, 136(4), 418–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, M; Flynn, R; Price, A; Ranger, A; Browning, JL; Taylor, PA; et al. Donor B-cell alloantibody deposition and germinal center formation are required for the development of murine chronic GVHD and bronchiolitis obliterans. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2012, 119(6), 1570–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S; Leigh, ND; Cao, X. The role of co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory signals in graft-vs.-host disease. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H; Fu, D; Bidgoli, A; Paczesny, S. T cell subsets in graft versus host disease and graft versus tumor. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 761448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegari, A; Mohebbi, F. Immune mediators as therapeutic targets in GvHD; cytokines, growth factors, chemokines, and co-stimulation /co-inhibition. Transpl Immunol. 2025, 93, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, C; Levy, DE; Decker, T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J Biol Chem. 2007, 282(28), 20059–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, LM; Zeiser, R. Kinase Inhibition as Treatment for Acute and Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 760199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaglowski, SM; Devine, SM. Graft-versus-host disease: why have we not made more progress? Curr Opin Hematol 2014, 21(2), 141–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurya, AU; Aliyu, U; Tudu, AI; Usman, AG; Yusuf, M; Gupta, S; et al. Graft-versus-host disease: Therapeutic prospects of improving the long-term post-transplant outcomes. Transplant Rep. 2022, 7(4), 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazar, BR; Murphy, WJ; Abedi, M. Advances in graft-versus-host disease biology and therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012, 12(6), 443–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Blanc, K; Dazzi, F; English, K; Farge, D; Galipeau, J; Horwitz, EM; et al. ISCT MSC committee statement on the US FDA approval of allogenic bone-marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. In Cytotherapy; Elsevier, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiser, R; von Bubnoff, N; Butler, J; Mohty, M; Niederwieser, D; Or, R; et al. Ruxolitinib for Glucocorticoid-Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382(19), 1800–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklos, D; Cutler, CS; Arora, M; Waller, EK; Jagasia, M; Pusic, I; et al. Ibrutinib for chronic graft-versus-host disease after failure of prior therapy. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2017, 130(21), 2243–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, C; Lee, SJ; Arai, S; Rotta, M; Zoghi, B; Lazaryan, A; et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood 2021, 138(22), 2278–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, R; Choi, J; Ruminski, P; Schroeder, MA; Kim, S; Abboud, CN; et al. Insights into the role of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in graft-versus-host disease. Ther Adv Hematol. 2020, 11, 2040620720914489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, KP; Blazar, BR; Hill, GR. Cytokine mediators of chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2017, 127(7), 2452–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, MA; Choi, J; Staser, K; DiPersio, JF. The role of Janus kinase signaling in graft-versus-host disease and graft versus leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018, 24(6), 1125–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Togni, E; Cole, O; Abboud, R. Janus kinase inhibition in the treatment and prevention of graft-versus-host disease. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1304065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L; Zhao, Y; Yang, J; Deng, L; Wang, N; Zhang, X; et al. Ruxolitinib plus steroids for acute graft versus host disease: a multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9(1), 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santosa, D; Rizky, D; Tandarto, K; Kartiyani, I; Yunarvika, V; Ardini, DNE; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ibrutinib for Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease: A Systematic Review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP 2023, 24(12), 4025–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S; Jung, J; Victor, E; Arceo, J; Gokhale, S; Xie, P. Clinical Trials of the BTK Inhibitors Ibrutinib and Acalabrutinib in Human Diseases Beyond B Cell Malignancies. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 737943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagasia, M; Lazaryan, A; Bachier, CR; Salhotra, A; Weisdorf, DJ; Zoghi, B; et al. ROCK2 Inhibition With Belumosudil (KD025) for the Treatment of Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2021, 39(17), 1888–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Sánchez, MC; Rodríguez-Serrano, C; Almeida, J; San Segundo, L; Inogés, S; Santos-Briz, Á; et al. Targeting of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway to inhibit T cell activation and prevent graft-versus-host disease development. J Hematol OncolJ Hematol Oncol 2016, 9(1), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ianni, M; Del Papa, B; Baldoni, S; Di Tommaso, A; Fabi, B; Rosati, E; et al. NOTCH and graft-versus-host disease. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaeth, M; Bäuerlein, CA; Pusch, T; Findeis, J; Chopra, M; Mottok, A; et al. Selective NFAT targeting in T cells ameliorates GvHD while maintaining antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112(4), 1125–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Valdepeñas, C; Casanova, L; Colmenero, I; Arriero, M; González, A; Lozano, N; et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB inducing kinase is required for graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica 2010, 95(12), 2111–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, HH; Ziegler, J; Li, C; Sepulveda, A; Bedeir, A; Grandis, J; et al. Sequential activation of inflammatory signaling pathways during graft-versus-host disease (GVHD): early role for STAT1 and STAT3. Cell Immunol. 2011, 268(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, A; Held, SAE; Daecke, SN; Wallner, S; Yajnanarayana, SP; Kurts, C; et al. The JAK-inhibitor ruxolitinib impairs dendritic cell function in vitro and in vivo. Blood 2013, 122(7), 1192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoerl, S; Mathew, NR; Bscheider, M; Schmitt-Graeff, A; Chen, S; Mueller, T; et al. Activity of therapeutic JAK 1/2 blockade in graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2014, 123(24), 3832–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, DB; Lim, JY; Kim, TW; Shin, S; Lee, SE; Park, G; et al. Preclinical evaluation of JAK1/2 inhibition by ruxolitinib in a murine model of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Exp Hematol 2021, 98, 36–46.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, R; Russo, D; Ram, R; Hashmi, SK; Chakraverty, R; Middeke, JM; et al. Ruxolitinib in Patients With Corticosteroid-Refractory or Corticosteroid-Dependent Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease: 3-Year Final Analysis of the Phase III REACH3 Study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2025, 43(23), 2566–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagasia, M; Perales, MA; Schroeder, MA; Ali, H; Shah, NN; Chen, YB; et al. Ruxolitinib for the treatment of steroid-refractory acute GVHD (REACH1): a multicenter, open-label phase 2 trial. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2020, 135(20), 1739–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D; Liu, Y; Lai, X; Chen, J; Cheng, Q; Ma, X; et al. Efficiency and Toxicity of Ruxolitinib as a Salvage Treatment for Steroid-Refractory Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 673636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redondo, S; Esquirol, A; Novelli, S; Caballero, AC; Garrido, A; Oñate, G; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ruxolitinib in Steroid-Refractory/Dependent Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: Real-World Data and Challenges. Transplant Cell Ther 2022, 28(1), 43.e1–43.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, NG; Im, A; Ostojic, A; Curtis, LM; Parsons-Wandell, L; Nashed, J; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Baricitinib in Refractory Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease (cGVHD): Preliminary Analysis Results of a Phase 1/2 Study. Blood 2020, 136, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, MA; Khoury, HJ; Jagasia, M; Ali, H; Schiller, GJ; Staser, K; et al. A phase 1 trial of itacitinib, a selective JAK1 inhibitor, in patients with acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood Adv. 2020, 4(8), 1656–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W; Nyuydzefe, MS; Weiss, JM; Zhang, J; Waksal, SD; Zanin-Zhorov, A. ROCK2, but not ROCK1 interacts with phosphorylated STAT3 and co-occupies TH17/TFH gene promoters in TH17-activated human T cells. Sci Rep. 2018, 8(1), 16636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin-Zhorov, A; Weiss, JM; Nyuydzefe, MS; Chen, W; Scher, JU; Mo, R; et al. Selective oral ROCK2 inhibitor down-regulates IL-21 and IL-17 secretion in human T cells via STAT3-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111(47), 16814–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, R; Paz, K; Du, J; Reichenbach, DK; Taylor, PA; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A; et al. Targeted Rho-associated kinase 2 inhibition suppresses murine and human chronic GVHD through a Stat3-dependent mechanism. Blood 2016, 127(17), 2144–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, SH; Moon, SJ; Park, MJ; Kim, EK; Moon, YM; Cho, ML. PIAS3 suppresses acute graft-versus-host disease by modulating effector T and B cell subsets through inhibition of STAT3 activation. Immunol Lett 2014, 160(1), 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H; Cui, J; Jia, X; Zhao, J; Feng, Y; Zhao, P; et al. Therapeutic effects of STAT3 inhibition by nifuroxazide on murine acute graft graft-vs.-host disease: Old drug, new use. Mol Med Rep. 2017, 16(6), 9480–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S; Yang, Q; Zhou, Y; Li, L; Shan, S. CS12192: A novel selective and potent JAK3 inhibitor mitigates acute graft-versus-host disease in bone marrow transplantation. Transpl Immunol 2024, 85, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S; Ashami, K; Lim, S; Staser, K; Vij, K; Santhanam, S; et al. Baricitinib prevents GvHD by increasing Tregs via JAK3 and treats established GvHD by promoting intestinal tissue repair via EGFR. Leukemia 2022, 36(1), 292–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Rodriguez, J; Kraus, ZJ; Schwartzberg, PL. Tec family kinases Itk and Rlk / Txk in T lymphocytes: cross-regulation of cytokine production and T-cell fates. FEBS J 2011, 278(12), 1980–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, JL; Tata, PV; Fore, MS; Wooten, J; Rudra, S; Deal, AM; et al. Increased BCR responsiveness in B cells from patients with chronic GVHD. Blood 2014, 123(13), 2108–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, AT; Wilcox, HM; Lai, Z; Berg, LJ. Signaling through Itk promotes T helper 2 differentiation via negative regulation of T-bet. Immunity 2004, 21(1), 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, AJ; Yu, L; Bäckesjö, CM; Vargas, L; Faryal, R; Aints, A; et al. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk): function, regulation, and transformation with special emphasis on the PH domain. Immunol Rev. 2009, 228(1), 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutt, SD; Fu, J; Nguyen, H; Bastian, D; Heinrichs, J; Wu, Y; et al. Inhibition of BTK and ITK with Ibrutinib Is Effective in the Prevention of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease in Mice. PloS One 2015, 10(9), e0137641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovsky, JA; Flynn, R; Du, J; Harrington, BK; Zhong, Y; Kaffenberger, B; et al. Ibrutinib treatment ameliorates murine chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2014, 124(11), 4867–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, LT; Logan, AC. Ibrutinib for the treatment of patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease after failure of one or more lines of systemic therapy. Drugs Today Barc Spain 1998 2018, 54(5), 305–13. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, EK; Miklos, D; Cutler, C; Arora, M; Jagasia, MH; Pusic, I; et al. Ibrutinib for Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease After Failure of Prior Therapy: 1-Year Update of a Phase 1b/2 Study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2019, 25(10), 2002–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichhart, T; Hengstschläger, M; Linke, M. Regulation of innate immune cell function by mTOR. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15(10), 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruman, DA; Rommel, C. PI3K and cancer: lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014, 13(2), 140–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero-Sánchez, MC; Rodríguez-Serrano, C; Almeida, J; San-Segundo, L; Inogés, S; Santos-Briz, Á; et al. Effect of mTORC1/mTORC2 inhibition on T cell function: potential role in graft-versus-host disease control. Br J Haematol 2016, 173(5), 754–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S; Passang, T; Li, Y; Zhang, H; Das, PK; Chen, K; et al. Dual Inhibition of PI3K Delta and PI3K Gamma Isoforms to Prevent Graft-Versus-Host Disease By Limiting T Cell Expansion In Vivo. Blood 2022, 140 Supplement 1, 10219–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castor, MGM; Rezende, BM; Bernardes, PTT; Vieira, AT; Vieira, ELM; Arantes, RME; et al. PI3Kγ controls leukocyte recruitment, tissue injury, and lethality in a model of graft-versus-host disease in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2011, 89(6), 955–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz, K; Flynn, R; Du, J; Tannheimer, S; Johnson, AJ; Dong, S; et al. Targeting PI3Kδ function for amelioration of murine chronic graft-versus-host disease. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg 2019, 19(6), 1820–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L; Gu, Z; Zhai, R; Li, D; Zhao, S; Luo, L; et al. The efficacy and safety of sirolimus-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transfusion (Paris) 2015, 55(9), 2134–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, C; Kim, HT; Hochberg, E; Ho, V; Alyea, E; Lee, SJ; et al. Sirolimus and tacrolimus without methotrexate as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after matched related donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2004, 10(5), 328–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, VT; Aldridge, J; Kim, HT; Cutler, C; Koreth, J; Armand, P; et al. Comparison of Tacrolimus and Sirolimus (Tac/Sir) versus Tacrolimus, Sirolimus, and mini-methotrexate (Tac/Sir/MTX) as acute graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2009, 15(7), 844–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblit, B; Storer, BE; Andersen, NS; Maris, MB; Chauncey, TR; Petersdorf, EW; et al. Sirolimus with CSP and MMF as GVHD prophylaxis for allogeneic transplantation with HLA antigen-mismatched donors. Blood 2020, 136(13), 1499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armand, P; Kim, HT; Sainvil, MM; Lange, PB; Giardino, AA; Bachanova, V; et al. The addition of sirolimus to the graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis regimen in reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for lymphoma: a multicentre randomized trial. Br J Haematol 2016, 173(1), 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, F; Zirlik, K; Buchner, M; Prinz, G; Hechinger, AK; Gerlach, UV; et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) is a potent target for GvHD prevention at different cellular levels. Leukemia 2012, 26(7), 1617–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, EJ; Infantino, S; Low, MSY; Tarlinton, DM. Lyn, Lupus, and (B) Lymphocytes, a Lesson on the Critical Balance of Kinase Signaling in Immunity. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, HL; Davis, WW; Whiteman, EL; Birnbaum, MJ; Puré, E. The tyrosine kinases Syk and Lyn exert opposing effects on the activation of protein kinase Akt/PKB in B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96(12), 6890–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, M; Sabe, H; Hata, A; Inazu, T; Homma, Y; Nukada, T; et al. Tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk regulate B cell receptor-coupled Ca2+ mobilization through distinct pathways. EMBO J 1994, 13(6), 1341–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, R; Allen, JL; Luznik, L; MacDonald, KP; Paz, K; Alexander, KA; et al. Targeting Syk-activated B cells in murine and human chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2015, 125(26), 4085–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Huu, D; Kimura, H; Date, M; Hamaguchi, Y; Hasegawa, M; Hau, KT; et al. Blockade of Syk ameliorates the development of murine sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Dermatol Sci 2014, 74(3), 214–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C; DiCioccio, RA; Haykal, T; McManigle, WC; Li, Z; Anand, SM; et al. A Phase I Trial of SYK Inhibition with Fostamatinib in the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Transplant Cell Ther. 2023, 29(3), 179.e1–179.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poe, JC; Jia, W; Di Paolo, JA; Reyes, NJ; Kim, JY; Su, H; et al. SYK inhibitor entospletinib prevents ocular and skin GVHD in mice. JCI Insight 2018, 3(19), 122430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, T; Kim, TK; Benjamin, CL; Wieder, ED; Levy, RB; Komanduri, KV. MEK inhibitors selectively suppress alloreactivity and graft-versus-host disease in a memory stage-dependent manner. Blood 2013, 121(23), 4617–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S; Rauch, J; Kolch, W. Targeting MAPK Signaling in Cancer: Mechanisms of Drug Resistance and Sensitivity. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, GL; Lapadat, R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science 2002, 298(5600), 1911–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itamura, H; Shindo, T; Tawara, I; Kubota, Y; Kariya, R; Okada, S; et al. The MEK inhibitor trametinib separates murine graft-versus-host disease from graft-versus-tumor effects. JCI Insight 2016, 1(10), e86331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itamura, H; Shindo, T; Muranushi, H; Kitaura, K; Okada, S; Shin-I, T; et al. Pharmacological MEK inhibition promotes polyclonal T-cell reconstitution and suppresses xenogeneic GVHD. Cell Immunol 2021, 367, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, A; Kobayashi, S; Miyai, K; Osawa, Y; Horiuchi, T; Kato, S; et al. TAK1 inhibition ameliorates survival from graft-versus-host disease in an allogeneic murine marrow transplantation model. Int J Hematol 2018, 107(2), 222–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, T; Date, M; Kano, M; Mizumaki, K; Tennichi, M; Kobayashi, T; et al. Blockade of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Inhibits Murine Sclerodermatous Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Am J Pathol 2017, 187(4), 841–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y; Song, Y; Zhang, Y; Shi, M; Hou, A; Han, S. NFAT signaling dysregulation in cancer: Emerging roles in cancer stem cells. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother 2023, 165, 115167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feske, S. Calcium signalling in lymphocyte activation and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2007, 7(9), 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangavelu, G; Du, J; Paz, KG; Loschi, M; Zaiken, MC; Flynn, R; et al. Inhibition of inositol kinase B controls acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2020, 135(1), 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, AT; Dahlberg, C; Sandberg, ML; Wen, BG; Beisner, DR; Hoerter, JAH; et al. Inhibition of the Inositol Kinase Itpkb Augments Calcium Signaling in Lymphocytes and Reveals a Novel Strategy to Treat Autoimmune Disease. PloS One 2015, 10(6), e0131071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storb, R; Deeg, HJ; Pepe, M; Appelbaum, F; Anasetti, C; Beatty, P; et al. Methotrexate and cyclosporine versus cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease in patients given HLA-identical marrow grafts for leukemia: long-term follow-up of a controlled trial. Blood 1989, 73(6), 1729–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka, A; Ohashi, Y; Okamoto, S; Moriyama, Y; Nagao, T; Kodera, Y; et al. Phase III study comparing tacrolimus (FK506) with cyclosporine for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001, 28(2), 181–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeckinghaus, A; Ghosh, S. The NF-kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009, 1(4), a000034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K; Welniak, LA; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A; O’Shaughnessy, MJ; Liu, H; Barao, I; et al. Inhibition of acute graft-versus-host disease with retention of graft-versus-tumor effects by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101(21), 8120–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T; Zhang, L; Joo, D; Sun, SC. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodanovic-Jankovic, S; Hari, P; Jacobs, P; Komorowski, R; Drobyski, WR. NF-kappaB as a target for the prevention of graft-versus-host disease: comparative efficacy of bortezomib and PS-1145. Blood 2006, 107(2), 827–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shono, Y; Tuckett, AZ; Ouk, S; Liou, HC; Altan-Bonnet, G; Tsai, JJ; et al. A small-molecule c-Rel inhibitor reduces alloactivation of T cells without compromising antitumor activity. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4(5), 578–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, CCS; Chen, M; Mirsoian, A; Grossenbacher, SK; Tellez, J; Ames, E; et al. Treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease with bortezomib. Blood 2014, 124(10), 1677–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Homsi, AS; Feng, Y; Duffner, U; Al Malki, MM; Goodyke, A; Cole, K; et al. Bortezomib for the prevention and treatment of graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Exp Hematol 2016, 44(9), 771–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, AF; Kim, HT; Bindra, B; Jones, KT; Alyea, EP, 3rd; Armand, P; et al. A phase II study of bortezomib plus prednisone for initial therapy of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2014, 20(11), 1737–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, M. Notch signalling in the nucleus: roles of Mastermind-like (MAML) transcriptional coactivators. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2016, 159(3), 287–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J; Ebens, CL; Perkey, E; Radojcic, V; Koch, U; Scarpellino, L; et al. Fibroblastic niches prime T cell alloimmunity through Delta-like Notch ligands. J Clin Invest. 2017, 127(4), 1574–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, F; MacDonald, HR; Tacchini-Cottier, F. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by Notch. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13(6), 427–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grazioli, P; Felli, MP; Screpanti, I; Campese, AF. The mazy case of Notch and immunoregulatory cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2017, 102(2), 361–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y; Sandy, AR; Wang, J; Radojcic, V; Shan, GT; Tran, IT; et al. Notch signaling is a critical regulator of allogeneic CD4+ T-cell responses mediating graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2011, 117(1), 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, IT; Sandy, AR; Carulli, AJ; Ebens, C; Chung, J; Shan, GT; et al. Blockade of individual Notch ligands and receptors controls graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2013, 123(4), 1590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachev, V; Vanderbeck, A; Perkey, E; Furlan, SN; McGuckin, C; Gómez Atria, D; et al. Notch signaling drives intestinal graft-versus-host disease in mice and nonhuman primates. Sci Transl Med. 2023, 15(702), eadd1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radojcic, V; Paz, K; Chung, J; Du, J; Perkey, ET; Flynn, R; et al. Notch signaling mediated by Delta-like ligands 1 and 4 controls the pathogenesis of chronic GVHD in mice. Blood 2018, 132(20), 2188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medinger, M; Junker, T; Heim, D; Tzankov, A; Jermann, PM; Bobadilla, M; et al. CB-103: A novel CSL-NICD inhibitor for the treatment of NOTCH-driven T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A case report of complete clinical response in a patient with relapsed and refractory T-ALL. EJHaem 2022, 3(3), 1009–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Shen, L; Dreißigacker, K; Zhu, H; Trinh-Minh, T; Meng, X; et al. Targeting of canonical WNT signaling ameliorates experimental sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2021, 137(17), 2403–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadli, M; Harris, R; Mahmudlu, S; Verma, A; May, A; Dhawan, R; et al. Human Wnt/β-Catenin Regulates Alloimmune Signaling during Allogeneic Transplantation. Cancers 2021, 13(15). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, HZ; Ye, YL; Suo, Y; Qu, H; Zhang, HY; Yang, KB; et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling mediates the abnormal osteogenic and adipogenic capabilities of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from chronic graft-versus-host disease patients. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12(4), 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayase, E; Ara, T; Saito, Y; Takahashi, S; Yoshioka, K; Ohigashi, H; et al. R-Spondin1 protects gastric stem cells and mitigates gastric GVHD in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Adv. 2024, 8(3), 725–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takashima, S; Kadowaki, M; Aoyama, K; Koyama, M; Oshima, T; Tomizuka, K; et al. The Wnt agonist R-spondin1 regulates systemic graft-versus-host disease by protecting intestinal stem cells. J Exp Med. 2011, 208(2), 285–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutt, SD; Wu, Y; Tang, CHA; Bastian, D; Nguyen, H; Sofi, MH; et al. Inhibition of the IRE-1α/XBP-1 pathway prevents chronic GVHD and preserves the GVL effect in mice. Blood Adv. 2018, 2(4), 414–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, HJ; Tang, CHA; Tian, L; Wu, Y; Sofi, MH; Ticer, T; et al. XBP-1s Promotes B Cell Pathogenicity in Chronic GVHD by Restraining the Activity of Regulated IRE-1α-Dependent Decay. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 705484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorton, D; Bellinger, DL. Molecular mechanisms underlying β-adrenergic receptor-mediated cross-talk between sympathetic neurons and immune cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2015, 16(3), 5635–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y; Zhang, XN; Su, S; Ruan, ZL; Hu, MM; Shu, HB. β-adrenoreceptor-triggered PKA activation negatively regulates the innate antiviral response. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023, 20(2), 175–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazova, S; Klena, L; Galvankova, K; Babula, P; Krizanova, O. Role of adrenergic receptors and their blocking in cancer research. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother 2025, 192, 118637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, ND; Kokolus, KM; O’Neill, RE; Du, W; Eng, JWL; Qiu, J; et al. Housing Temperature-Induced Stress Is Suppressing Murine Graft-versus-Host Disease through β2-Adrenergic Receptor Signaling. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 2015, 195(10), 5045–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarberg, KMK; Li, J; Heinrichs, J; Wang, D; Liu, C; Bronk, CC; et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of PKCα and PKCθ prevents GVHD while preserving GVL activity in mice. Blood 2013, 122(14), 2500–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, JO; Iclozan, C; Hossain, MS; Prlic, M; Hopewell, E; Bronk, CC; et al. PKCtheta is required for alloreactivity and GVHD but not for immune responses toward leukemia and infection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009, 119(12), 3774–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubai, T; Sun, Y; Tawara, I; Friedman, A; Liu, C; Evers, R; et al. Ikaros-Notch axis in host hematopoietic cells regulates experimental graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2011, 118(1), 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heizmann, B; Kastner, P; Chan, S. The Ikaros family in lymphocyte development. Curr Opin Immunol 2018, 51, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, AD; de Molla, VC; Fonseca, ARBM; Tucunduva, L; Novis, Y; Pires, MS; et al. Ikaros expression is associated with an increased risk of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Sci Rep. 2023, 13(1), 8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Huang, A; Chen, Q; Chen, X; Fei, Y; Zhao, X; et al. A distinct glycerophospholipid metabolism signature of acute graft versus host disease with predictive value. JCI Insight 2019, 5(16), 129494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M; Zhang, K; Li, S; Guo, H; Sun, Y; Kong, J; et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals heterogeneity of mucosa-associated invariant T cells in donor grafts and its diagnostic relevance in gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H; Li, R; Wang, M; Hou, Y; Liu, S; Peng, T; et al. Multiomics Analysis Identifies SOCS1 as Restraining T Cell Activation and Preventing Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Adv Sci Weinh Baden-Wurtt Ger 2022, 9(21), e2200978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamimoto, K; Stringa, B; Hoffmann, CM; Jindal, K; Solnica-Krezel, L; Morris, SA. Dissecting cell identity via network inference and in silico gene perturbation. Nature 2023, 614(7949), 742–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibar, S; González-Blas, CB; Moerman, T; Huynh-Thu, VA; Imrichova, H; Hulselmans, G; et al. SCENIC: single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering. Nat Methods 2017, 14(11), 1083–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vamathevan, J; Clark, D; Czodrowski, P; Dunham, I; Ferran, E; Lee, G; et al. Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019, 18(6), 463–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamiri, SS; Amin, R. The Potential Use of Digital Twin Technology for Advancing CAR-T Cell Therapy. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2025, 47(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niarakis, A; Laubenbacher, R; An, G; Ilan, Y; Fisher, J; Flobak, Å; et al. Immune digital twins for complex human pathologies: applications, limitations, and challenges. NPJ Syst Biol Appl. 2024, 10(1), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V; Sharma, S; Pokharel, YR. Exploring CRISPR-Cas: The transformative impact of gene editing in molecular biology. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2025, 36(4), 102717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neidemire-Colley, L; Khanal, S; Braunreiter, KM; Gao, Y; Kumar, R; Snyder, KJ; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 deletion of MIR155HG in human T cells reduces incidence and severity of acute GVHD in a xenogeneic model. Blood Adv. 2024, 8(4), 947–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, AJ; Lin, DTS; Gillies, JK; Uday, P; Pesenacker, AM; Kobor, MS; et al. Optimized CRISPR-mediated gene knockin reveals FOXP3-independent maintenance of human Treg identity. Cell Rep. 2021, 36(5), 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, V; Meringa, A; Dunnebach, E; van Velzen, A; Moreira, AV; Stam, RW; et al. Combining CRISPR-Cas9 and TCR exchange to generate a safe and efficient cord blood-derived T cell product for pediatric relapsed AML. J Immunother Cancer 2024, 12(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flumens, D; Campillo-Davo, D; Janssens, I; Roex, G; De Waele, J; Anguille, S; et al. One-step CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of native TCRαβ genes in human T cells using RNA electroporation. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4(1), 102112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T; Wang, Y; Zhang, Y; Yang, Y; Cao, J; Huang, J; et al. Leveraging CRISPR gene editing technology to optimize the efficacy, safety and accessibility of CAR T-cell therapy. Leukemia 2024, 38(12), 2517–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X; Zhong, S; Zhan, Y; Zhang, X. CRISPR-Cas9 applications in T cells and adoptive T cell therapies. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2024, 29(1), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, D; Binan, L; Bezney, J; Simonton, B; Freedman, J; Frangieh, CJ; et al. Scalable genetic screening for regulatory circuits using compressed Perturb-seq. Nat Biotechnol. 2024, 42(8), 1282–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, A; Parnas, O; Li, B; Chen, J; Fulco, CP; Jerby-Arnon, L; et al. Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens. Cell 2016, 167(7), 1853–1866.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraivogel, D; Steinmetz, LM; Parts, L. Pooled Genome-Scale CRISPR Screens in Single Cells. Annu Rev Genet. 2023, 57, 223–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, SQ; Zheng, Z; Nguyen, NT; Liebers, M; Topkar, VV; Thapar, V; et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2015, 33(2), 187–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H; Zhang, M; Chakarov, D; Bansal, V; Mourelatos, H; Sánchez-Rivera, FJ; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR guide RNA design and specificity analysis with GuideScan2. Genome Biol. 2025, 26(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höijer, I; Johansson, J; Gudmundsson, S; Chin, CS; Bunikis, I; Häggqvist, S; et al. Amplification-free long-read sequencing reveals unforeseen CRISPR-Cas9 off-target activity. Genome Biol. 2020, 21(1), 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abboud, R; Schroeder, MA; Rettig, MP; Jayasinghe, RG; Gao, F; Eisele, J; et al. Itacitinib for prevention of graft-versus-host disease and cytokine release syndrome in haploidentical transplantation. Blood 2025, 145(13), 1382–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).