1. Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) refers to harmful acts inflicted upon individuals based on socially constructed gender roles and power inequalities. These acts include physical, emotional, sexual, and economic abuse, occurring across private and public spheres (Allen-Leap et al., 2023). In the aftermath of GBV, survivors often rely on a combination of internal and external resources to support their recovery. Internal resources are the personal strengths, skills, and coping mechanisms that help individuals endure and navigate traumatic experiences. In contrast, external resources involve the assistance and services available from outside sources, such as healthcare providers, community organizations, legal aid, and support groups. Together, these resources form a foundation of support critical to the healing process. Internal motivators may include a personal desire for healing, self-reclamation, or the well-being of one’s children. External motivators arise from surrounding circumstances, such as encouragement from peers, access to justice, or opportunities for independence and empowerment (AUTHOR et al., manuscript submitted for publication). This paper will present the psychometric analysis of the Motivators and Resources for Trauma Recovery (I-MOVE) Scale.

1.1. Background

While GBV can affect people of all genders, it most commonly impacts women, with intimate partner violence (IPV) being the most prevalent form. Globally, approximately 27% of women aged 15 to 49 have experienced IPV in their lifetime (Sardinha et al., 2018). The consequences of such violence are profound, ranging from immediate physical injuries to long-term mental health challenges, economic instability, and social isolation. These effects are often intensified for women who experience overlapping forms of marginalization, such as racism, socioeconomic disadvantage, or migration-related stress (Allen-Leap et al., 2023). While much of the existing literature has historically focused on the psychological trauma and clinical diagnoses resulting from GBV, there is a growing shift toward a more holistic and strength-based understanding of survivor recovery (Reid et al., 2008; Sinko et al., 2020). Recovery, in this context, is seen as a complex, multidimensional process influenced by cognitive, emotional, relational, and structural factors (Reid et al., 2008).

Survivors’ recovery journeys are shaped by diverse sociocultural contexts that influence how they navigate and access support (Wright et al., 2022). While cultural norms and social expectations can sometimes act as barriers that discourage help-seeking (Saint Arnault & Zonp, 2022) or promote self-silencing (Wright et al., 2022), they can also offer pathways to healing through community solidarity, spiritual practices, and culturally grounded coping mechanisms (Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013). Within these contexts, survivors often demonstrate remarkable strength and resilience, drawing upon motivators and resources that align with their lived realities. Acknowledging these dynamics highlights not only the complexity of trauma recovery but also the profound capacity survivors must access, adapt, and build upon available resources in ways that are personally meaningful and culturally relevant.

Recent literature on trauma recovery has increasingly shifted toward identifying and understanding the motivators and resources that support survivors’ healing. A systematic review of 68 quantitative studies and qualitative interviews with 27 women in India found that, while social norms and attitudes supportive of violence acted as barriers, factors such as women’s empowerment, financial independence, and informal social support served as both protective factors and facilitators in addressing IPV (Sabri et al., 2022). Another study analyzing the narratives of ten diverse IPV survivors revealed that healing is a multidimensional, nonlinear, and deeply personal process characterized by internal awareness, reconstruction of self, and the pursuit of meaning often through helping others (D’Amore et al., 2021). In a phenomenological study with 22 survivors who had experienced post-traumatic growth (PTG), participants described moving from victimhood to a sense of mastery, citing personal strengths, positive attitudes, boundary setting, and the choice to surround themselves with constructive, non-controlling environments as key contributors to their healing (Bryngeirsdottir & Halldorsdottir, 2022). Additionally, a comprehensive meta-analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials involving 4,683 participants assessed the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in improving survivors’ wellbeing. The findings indicated improvements across a range of outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, stress, safety, social support, self-esteem, and health, highlighting the importance of empowerment and mental health-focused treatment strategies (Karakurt et al., 2022). Taken together, these studies reinforce that survivors not only cope with adversity but actively mobilize a variety of personal and contextual strengths to support their recovery, underscoring the need to assess these motivators and resources systematically.

1.2. Measurement of Resources and Motivators for Trauma Healing

Understanding the multifaceted processes of trauma recovery among GBV survivors requires tools that can capture the full spectrum of internal and external factors that influence healing. While existing instruments address components of recovery such as coping, resilience, and meaning making (Sinko et al., 2021; Benight et al., 2015). There remains a significant need for a comprehensive, survivor-centered tool that brings together these dimensions into a single, cohesive framework. Several tools address certain aspects of the healing journey. For instance, the GBV-Heal Scale assesses recovery by capturing valuable internal and relational aspects of healing (Sinko et al., 2021). The Coping Self-Efficacy Scale for Trauma (Benight et al., 2015) and the Domestic Violence Coping Self-Efficacy (Benight et al., 2004) measure trauma-related coping capabilities, particularly at the intrapersonal level. The Resilience Rugged Scale measures personal resilience (Jefferies et al., 2022) whereas Sense of Meaning Inventory (Saint Arnault & Zonp, 2024) explore broader existential and psychological constructs. The Trauma Recovery Rubric outlines general stages of recovery but does not deeply examine cultural, structural, or community-level influences (Koutra et al., 2022).

Despite their contributions, these tools are often limited in scope highlighting either personal motivators or external resources but not connecting these together in a unified way. Moreover, they may not fully reflect the intersectional realities of diverse survivor populations, including immigrants, whose experiences of trauma and recovery are shaped by layered cultural, systemic, and social dynamics. The I-MOVE Scale was developed to address this critical gap.

1.3. The Current Study

The I-MOVE Scale is a 57-item measure developed to assess internal and external resources, as well as motivators, that facilitate healing among gender-based violence (GBV) survivors. Grounded in survivor-informed perspectives, the scale is intended to capture constructs relevant across diverse sociocultural contexts. This study aims to psychometrically evaluate the I-MOVE scale through structural equation modeling, including both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The goal is to examine the scale’s dimensionality, assess its internal consistency, and determine the most relevant items to retain.

The present study is guided by the following research questions:

What are the underlying factor structures of the I-MOVE scale, as identified through EFA and CFA, in GBV context?

To what extent does the I-MOVE scale demonstrate convergent, discriminant, and known group validity across varied sociocultural samples?

How do demographic variables particularly parenting status and migration experience influence scores on the I-MOVE scale?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to conduct a psychometric assessment of the 57-item Motivators and Resources for Trauma Recovery (I-MOVE) Scale. A convenience sampling approach was used to recruit participants who were 18 years or older, identified as women, and self-identified as having experienced gender-based violence (GBV), including but not limited to intimate partner violence, sexual assault, child abuse, or stalking. Individuals who had not experienced GBV were excluded from participation.

Participants were recruited through a university-affiliated health research portal in Michigan; ResearchMatch, a nonprofit program funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that links interested volunteers with researchers across the U.S.; and targeted outreach via Facebook. Participants accessed and completed a secure, anonymous online survey, which took approximately 30 minutes. Participation implied informed consent. As an incentive, twenty participants were randomly selected to receive a $10 gift card, with recipients chosen using randomization software (Haahr, n.d.). The study protocol and materials were reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan ethics committee (HUM00268370).

2.2. Instruments and Measures

Demographic information collected in this study included participants’ country of origin, age, gender identity, immigrant status, parental status (whether they have children), racial identity, education level, and employment status. Additional questions assessed participants’ experiences with gender-based violence (GBV), including the type of violence experienced, history of abuse within the past year, and perceived need for support. To ensure clarity and consistency in responses, a standardized definition of GBV was provided at the beginning of the survey. Participants were informed that, according to the United Nations, gender-based violence is defined as any act that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.

2.3. Motivators and Resources for Trauma Recovery (I-MOVE) Scale

The Motivators and Resources for Trauma Recovery (I-MOVE) Scale is a 57-item instrument designed to assess both internal and external resources, as well as key motivators that support healing among individuals who have experienced gender-based violence (GBV) (AUTHOR et al., Under Review). Participants respond using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (To a great extent), with an additional “Not Applicable” option. Higher total scores indicate a greater presence of motivators and resources that support trauma recovery.

2.4. Convergent Validity

To assess convergent validity, three established instruments were used: the Sense of Meaning Inventory (SOMI), the Healing After Gender-Based Violence Scale (GBV-HEAL), and the Coping Self-Efficacy- Trauma Scale (CSE-T). It was hypothesized that the I-MOVE instrument would demonstrate significant positive correlations with each of these scales, providing evidence of convergent validity.

The SOMI is a 15-item scale that examines manageability, comprehension, and meaning in life (Saint Arnault & Zonp, 2024), rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1-5). Higher total scores indicate a higher sense of coherence. Cronbach's alpha for this study was 0.81. The GBV-HEAL Scale is an 18-item instrument assessing multidimensional healing among individuals among GBV (Sinko et al., 2021). Rated on a 5-point Likert Scale (0-4). Higher scores reflect greater perceived healing. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.83. The (CSE-T) 7-item scale, developed to evaluate an individual's perceived ability to manage the psychological and emotional demands following a traumatic event (Benight et al., 2015). Rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1-7). Higher scores indicate greater coping self-efficacy. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.65.

2.5. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Post-traumatic Cognition Inventory (PTCI), Barriers to Help Seeking – Trauma Recovery (BHS-TR), and the Normalization of Gender-Based Violence Scale (NGBV). It was hypothesized that the I-MOVE instrument would demonstrate low or nonsignificant correlations with these measures. The PTCI-8 is an 8-item measure assessing negative trauma-related thoughts (Hansen et al., 2010). Rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1-7). Higher scores indicate stronger negative cognitions. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.58. The BHS-TR is a 24-item instrument assessing barriers to support (Saint Arnault & Zonp, 2022). Only the internal barriers dimension was used. Rated on a 4-poinr scale (0-3). The Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.89. The NGBV is a 13-item instrument assessing normalization of GBV (AUTHOR et al., 2024). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1-5). Higher scores reflect a stronger normalization of gender-based violence. The Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.85.

2.6. Known Group Validity

Known-groups validity was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 – Short Form (PCL-5-8) to distinguish participants by depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms. It was hypothesized that those scoring above clinical cutoffs would report lower scores on the I-MOVE scores. The PHQ-8 is a modified version of the PHQ-9, excluding the ninth item that assesses suicidal ideation, which enhances its suitability for use in community-based research settings (Kroenke et al., 2009). Rated a 4-point Likert scale (0-3). Higher scores reflect more severe depressive symptoms. For this study, a clinical cutoff of 10 or higher was used (Kroenke et al., 2009). The Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.69. The PCL-5-8 is developed to efficiently screen for PTSD symptoms (Price et al., 2016). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0-4). A score of 13 or higher is used as a cutoff to identify probable PTSD (Price et al., 2016). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.72.

2.7. Analyses

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) Statistics for Windows, Version 30. Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations (SD), frequencies, and percentages were computed to summarize participant characteristics.

2.8. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The psychometric evaluation of the I-MOVE scale was conducted through both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on separate datasets. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted in IBM SPSS using principal component analysis with ProMax rotation to examine the latent structure of the I-MOVE scale. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO; Cerny & Kaiser, 1977) measure of sampling adequacy was .835, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (Bartlett, 1954) was significant, χ²(946) = 3217.96, p < .001, supporting factorability. Components with eigenvalues > 1 were retained. Items with loadings < .30 or cross-loadings ≥ .35 were excluded to ensure construct clarity. Internal consistency of extracted factors was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then performed in IBM AMOS to validate the factor structure. Model fit was evaluated using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI; Byrne, 1994), Incremental Fit Index (IFI; Bollen, 1989), Normed Fit Index (NFI; Byrne, 1994), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Byrne, 1994), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Kline, 2016). Conventional thresholds were applied: CFI, TLI, NFI, and IFI ≥ .90; SRMR ≤ .08; and RMSEA ≤ .10, with lower AIC values indicating better model fit.

2.9. Convergent and Discriminant and Known Group Validity

Construct validity of the I-MOVE scale was examined through convergent, discriminant, and known-groups validity. Convergent validity was assessed using Pearson correlations with SOMI, GBV-HEAL, and CSE-T. Discriminant validity was tested against BHS-TR and NGBV. Known-groups validity was evaluated by comparing I-MOVE scores across participants with elevated depressive symptoms (PHQ-8) and PTSD symptoms (PCL-5-8) using independent samples t-tests and linear regression analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The sample included 526 gender-based violence (GBV) survivors, who were randomly divided into two equal groups (n = 263 each) for exploratory factor analysis (Group 1, EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (Group 2, CFA). Randomization was stratified to ensure equal representation of participants currently experiencing abuse (43.0%) and those not currently experiencing abuse (57.0%) across both groups. The mean age was 40.1 years (SD = 15.2) for Group 1 and 35.3 years (SD = 14.5) for Group 2. Most participants were from the United States (89.3%), followed by Pakistan (4.4%), Afghanistan (1.7%), India (1.1%), Bangladesh (0.6%), Egypt (0.2%), and Germany (0.2%). Only a small proportion of participants identified as immigrants: 3.8% in Group 1 and 4.2% in Group 2. The distribution of participants across countries of origin was similar in both groups. The racial composition of the sample was diverse, with most participants identifying as Caucasian (64.0% in Group 1 and 54.0% in Group 2) or Black or African American (29.1% in Group 1 and 35.6% in Group 2). Smaller percentages identified as Asian, Hispanic/Latino, Native American, Middle Eastern/North African, or multi-racial. The majority in both groups reported having children (78.2% in Group 1 and 79.8% in Group 2). In terms of educational attainment, both groups were comparable in their educational backgrounds. In Group 1, 30.2% held an associate’s degree and 23.7% held a bachelor’s degree. In Group 2, 32.3% held an associate’s degree and 26.2% held a bachelor’s degree. Other education levels were distributed relatively evenly. Most participants were employed (84.8% in Group 1, 85.5% in Group 2). Participants reported their experiences with different forms of GBV (which was not exclusive, and they could indicate all that applied. In Group 1, psychological/emotional violence was most common (13.3%), followed by sexual violence (38.8%) and physical violence (46.4%). In Group 2, similar trends were observed: psychological/emotional (14.5%), sexual (41.4%), and physical (43.3%). Fewer participants in both groups reported economic/financial abuse or stalking. There were no significant demographic differences between the EFA and CFA groups, indicating comparability for scale validation. The demographic characteristics for both groups are summarized in

Table 1.

Group comparisons examined whether I-MOVE scores varied by demographic characteristics within Groups 1 and 2. In Group 1, no significant differences were found in I-MOVE scores based on having children (t (261) = –1.47, p = .144, d = –0.18), immigrant status (t (260) = –1.11, p = .267, d = –0.36), or current abuse history (t (259) = –0.02, p = .983, d = –0.003). In contrast, Group 2 showed significantly lower I-MOVE scores among participants experiencing current abuse (t (260) = –3.73, p = .003, d = –1.19) and, to a lesser extent, among those with children (t (261) = –2.72, p = .007, d = –0.34).

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

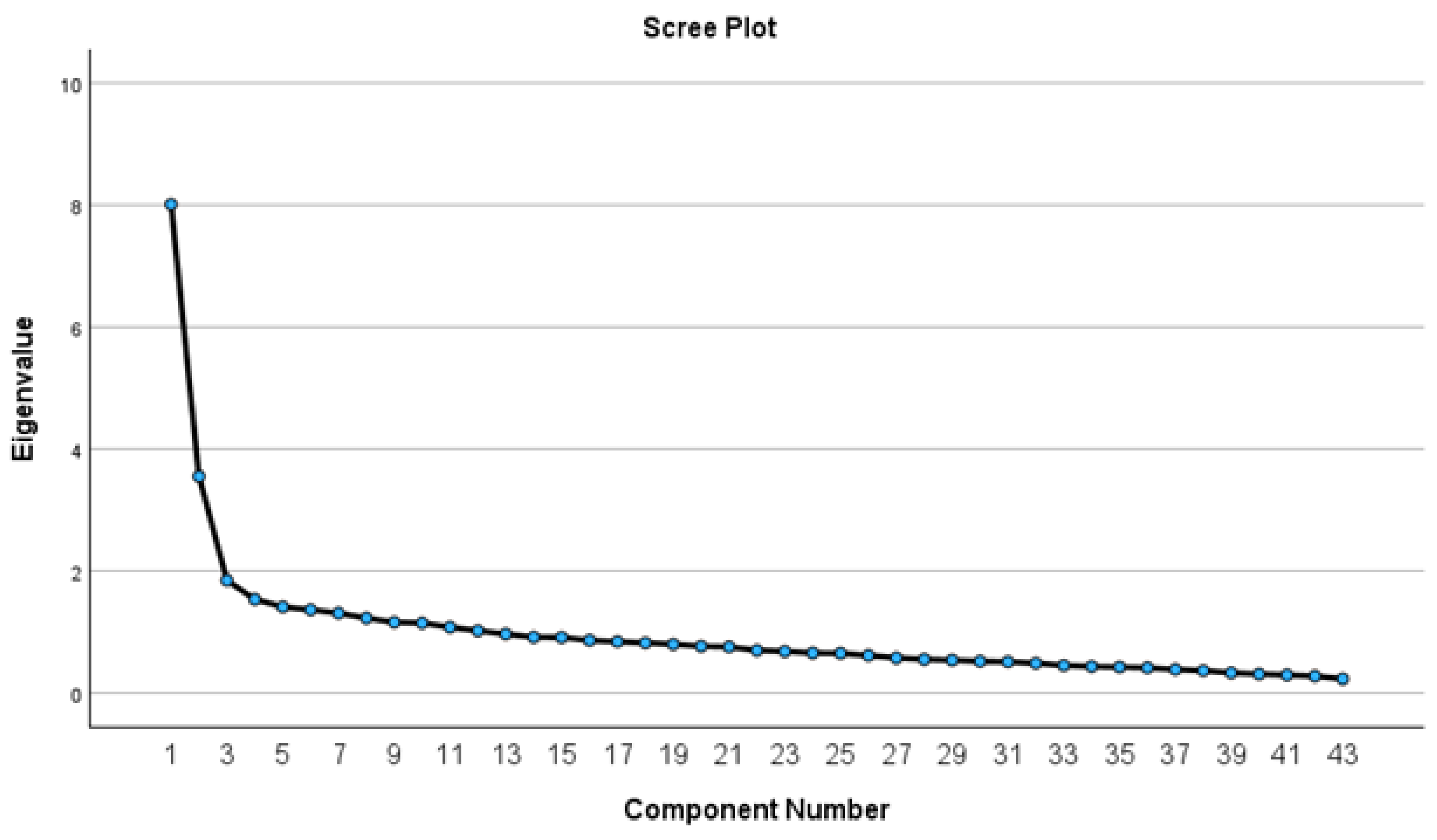

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using principal component analysis with ProMax rotation. Five components with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted, collectively explaining 38.1% of the total variance. While higher explained variance is preferred, values around 40% are considered acceptable in social science research, particularly with complex constructs (Hair et al., 2014). This level of explained variance suggests that the retained factors adequately captured a substantial portion of variability among the observed variables, supporting the robustness of the factor solution. The eigenvalue plot (

Figure 1) further supports factor retention decisions by visually identifying the point of inflection (elbow), which justifies the number of factors retained (Costello & Osborne, 2005).

The initial item pool comprised 57 items. During the analysis, two items loaded independently on a single factor with extreme values and were therefore excluded (#55: I wanted to protect my children, and #56: I wanted to provide a better future for my children). Additionally, six items did not load on any factor at the .30 level and were removed: (#18: I was looking for new hope, #24: I wanted to acquire new skills, #38: I wanted to be a role model, #41: I wanted to break the cycle of violence, #54: My new partner offered kindness and encouragement, and #57: My resident status provided me with stability and opportunities).

In addition, six items were excluded due to substantial double loadings. These included: (#1: My beliefs supported my recovery journey, #9: I wanted to become more comfortable in my body, #12: I realized that gender norms were inhibiting my self-care, #13: I found the language to communicate what was happening to me, #23: I wanted to learn new ways to recover from my experiences and #53: A trusted person gave me a referral). All excluded items were carefully reviewed, and decisions were based on both statistical loading patterns and theoretical relevance, to enhance model clarity and reduce redundancy.

The final EFA model consisted of 43 items distributed across five conceptually coherent factors: Self driven recovery (14 items), Access to supportive resources (9 items), Self-awareness and growth subscale (8 items), Social awareness and empowerment subscale (7 items), and Turning points towards healing subscale (5 items) (see

Table 2). This five-factor structure provides a clear and interpretable foundation for the subsequent confirmatory factor analysis.

The pattern matrix and reliability scores for the entire scale and subscales are presented below in

Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated for the total scale and each of the five subscales. The alpha reliability for the total scale was 0.89, indicating good internal consistency. Subscale reliability scores were as follows: 0.83 for Self-driven Recovery, 0.75 for Access to Supportive Resources, 0.71 for Self-awareness and Growth, 0.73 for Social Awareness and Empowerment, and 0.61 for Turning Points Toward Healing. These results suggest acceptable to strong internal consistency for most subscales.

The reliability of subscale 5 is modest (α=0.61), this reflects the conceptual breadth of turning point experiences, which by nature are diverse and situational. This subscale should be interpreted with caution in clinical applications.

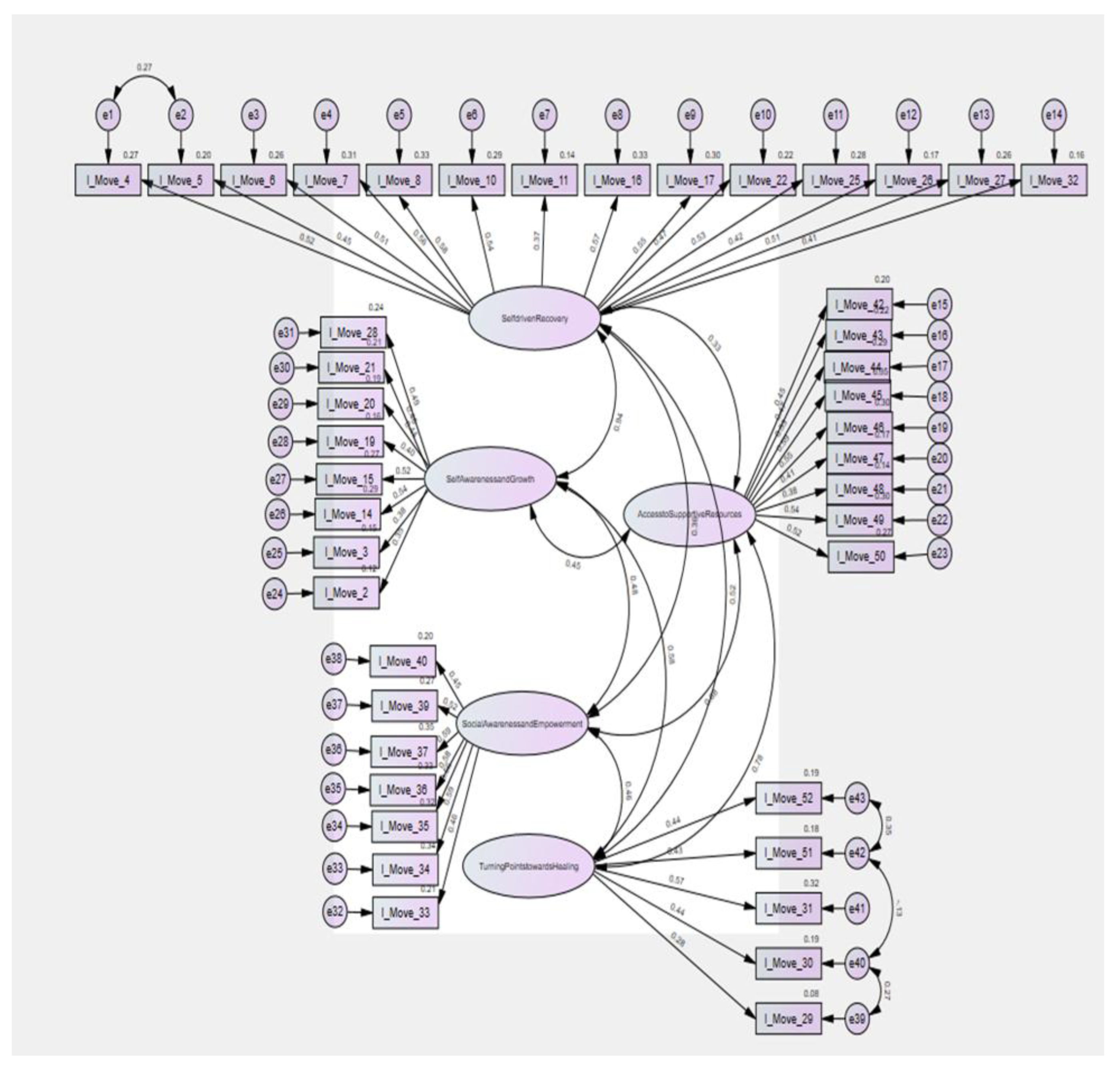

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis supported the hypothesized five-factor structure of the I-MOVE instrument, demonstrating an acceptable model fit to the data. The fit indices were as follows: CFI = 0.809, TLI = 0.796, RMSEA = 0.045 (90% CI: 0.040–0.050), and CMIN/DF = 1.53 (

Table 4). While the CFI and TLI values fell slightly below the conventional 0.90 threshold, this is not uncommon in complex models with multiple latent constructs and numerous indicators. Prior literature acknowledges that incremental fit indices may underestimate model adequacy in such contexts, particularly within social-behavioral research (Marsh et al., 2005; Hair et al., 2019). Importantly, the RMSEA and CMIN/DF values indicated strong absolute fit, and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) value for the final model was 1493.91, which was substantially lower than that of the independence and saturated models, indicating a better fitting and more parsimonious model.

To enhance model fit without compromising theoretical integrity, four error covariances were added between item residuals within the same latent construct. These adjustments were based on high modification indices and conceptual justification, such as shared phrasing or subdomain overlap. All items loaded significantly onto their respective latent factors (p < .001), with most standardized loadings exceeding 0.40, supporting the construct validity of the I-MOVE model in capturing diverse motivators and resources for trauma recovery (see

Figure 2).

3.4. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Convergent validity was assessed by examining the associations between the I-MOVE scale and three conceptually related measures: the Sense of Meaning Inventory (SOMI), the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale for Trauma (CSE-T), and the Healing After Gender-Based Violence Scale (GBV-Heal). Significant positive correlations were found between I-MOVE and SOMI (

r = 0.258), CSE-T (

r = 0.195), and GBV-Heal (

r = 0.254) (

Table 5).

Discriminant validity was evaluated by analyzing the correlations between I-MOVE and three theoretically unrelated or opposing constructs: the Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI), the Normalization of Gender-Based Violence Scale (NGBV), and the Barriers to Help-Seeking for Trauma Scale (BHS-TR). I-MOVE showed a significant weak positive correlation with BHS-TR (r = 0.239) (

Table 5). The associations between PTCI, NGBV and the I-MOVE were not significant. Given the unexpected positive correlation between I-MOVE and BHS-TR, additional Pearson correlation analyses were conducted between the I-Move subscales and the BHS-TR. Three out of five subscales showed significant positive correlations: Empowerment through Action (r = 0.410), Support and Belonging (r = 0.420), and Turning Points toward Healing (r = 0.255).

3.5. Known-Groups Validity

Independent samples t-tests revealed that participants who had probable depression had significantly lower I-MOVE scores compared with those who did not,

t (523) = –2.764,

p = 0.006. Similarly, participants who had probable PTSD symptoms reported significantly lower I-MOVE scores compared with those who did not,

t (524) = –4.203,

p < 0.001 (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the psychometric properties of the I-MOVE Scale, a survivor-informed tool developed to assess internal and external resources and motivators that support recovery among GBV survivors. The findings support the reliability and validity of the instrument, demonstrating its potential utility in both clinical and research contexts. The I-MOVE demonstrated a stable five-factor structure with acceptable reliability and model fit, confirming that trauma recovery can be meaningfully conceptualized through domains of personal motivation, supportive resources, self-awareness, empowerment, and healing turning points. Although some conceptually important items were excluded such as parenting and migration-related motivators their removal reflects statistical considerations rather than irrelevance. Prior research has shown that parenting responsibilities (AUTHOR & AUTHOR, 2024; Campbell & Mannell, 2016) and immigration-related aspirations (Guruge & Khanlou, 2004) are central to recovery for many survivors. These findings highlight a tension in scale development: standardized factor solutions may overlook culturally grounded or context-specific motivators. Future iterations of I-MOVE may benefit from optional subdomains that capture these salient but variable drivers of healing.

Convergent validity was supported by positive associations with measures of meaning-making, coping self-efficacy, and healing (SOMI, CSE-T, GBV-HEAL), suggesting conceptual alignment while also indicating that I-MOVE captures a distinct dimension of recovery. This multidimensional perspective is consistent with trauma recovery literature emphasizing the interplay of individual strengths and environmental resources (Herman, 1992; Campbell, 2016). By integrating both motivators and resources, I-MOVE advances strengths-based approaches to survivor-centered healing. Discriminant validity findings further reinforce this interpretation. Non-significant associations with constructs such as normalization of violence (NGBV) and trauma-related cognitions (PTCI) confirm conceptual distinctiveness. The unexpected positive association with internal barriers to help-seeking (BHS-TR) is notable. Rather than undermining validity, this finding may reflect survivors’ increased awareness of their own barriers as part of recovery a dynamic consistent with trauma-informed models that recognize recovery as nonlinear and intertwined with ongoing struggles (Campbell, 2022; Sinko & Saint Arnault, 2021). This suggests that acknowledging internal obstacles may itself be an indicator of growth and self-awareness. Known-groups validity analyses further demonstrated that survivors with probable depression and PTSD symptoms reported lower I-MOVE scores. This aligns with prior research indicating that psychological distress constrains access to recovery resources and reduces survivors’ perceived agency (Magaard et al., 2017; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). The sensitivity of I-MOVE to clinical subgroup differences strengthens its relevance for both research and applied trauma-informed care.

The scale also showed consistency across demographic characteristics such as race, education, and immigrant status, while remaining sensitive to lived trauma contexts. Participants currently experiencing abuse and, to a lesser extent, those with children reported lower scores in some groups. These findings reinforce the balance of generalizability and contextual nuance in I-MOVE: it appears robust across static demographic factors yet responsive to the dynamic realities of survivors’ current circumstances. Such sensitivity enhances its utility for equitable application in diverse populations. Together, these findings demonstrate that I-MOVE is a psychometrically sound tool that integrates internal motivators with external resources to capture a more holistic view of recovery. This survivor-centered lens shifts emphasis away from symptom reduction alone and toward strengths, agency, and contextual supports—an approach increasingly called for in trauma recovery research and practice (Sinko & Saint Arnault, 2021; Campbell & Mannell, 2016). Clinically, I-MOVE can help practitioners identify areas of resilience alongside unmet needs, supporting individualized and culturally informed care planning. For researchers, the instrument provides a systematic means of assessing recovery processes that extend beyond pathology, facilitating comparative studies across populations and contexts.

Future research should explore how I-MOVE’s domains interact with trauma symptoms over time and how context-specific motivators, such as parenting or migration experiences, can be meaningfully incorporated without compromising psychometric rigor. Longitudinal and cross-cultural studies are particularly needed to examine how recovery processes vary across diverse sociocultural environments and among survivors facing structural inequities. By centering survivor perspectives while maintaining strong psychometric foundations, the I-MOVE scale contributes to the advancement of trauma-informed, strengths-based approaches to supporting recovery.

5. Limitations and Conclusions

This study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design was appropriate for psychometric evaluation but does not allow assessment of how motivators and resources change over time. Longitudinal research is needed to evaluate the I-MOVE’s sensitivity to change and predictive validity. The sample was predominantly U.S.-based, providing a strong initial foundation but highlighting the need for cross-cultural validation, particularly given the scale’s emphasis on culturally relevant recovery resources. Model fit indices (CFI, TLI) were slightly below conventional thresholds, a common occurrence in complex models with many indicators. Consistent with best practices, we relied on multiple indices, including RMSEA and AIC, which demonstrated adequate fit (Kline, 2016). Finally, modest correlations between some I-MOVE subscales and the BHS-TR suggest conceptual proximity; however, these relationships likely reflect the complexity of trauma recovery, where empowerment and support may co-exist with awareness of barriers. This underscores the importance of conceptualizing recovery as a multidimensional and non-linear process. The I-MOVE scale offers a survivor-centered, strengths-based approach to assessing trauma recovery among GBV survivors by integrating internal motivators and external resources. The instrument demonstrated robust psychometric properties, including convergent, discriminant, and known-groups validity. Its multidimensional structure provides utility for clinical assessment, program evaluation, and survivor-informed research. Future studies should examine longitudinal applications, sensitivity to intervention effects, and cross-cultural generalizability, particularly in structurally marginalized populations. As the field advances toward empowerment-based, trauma-informed models of care, I-MOVE provides a timely and actionable tool for tailoring recovery planning and amplifying survivor voices in healing processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B.M. and D.S.A.; methodology, F.B.M. and D.M.S.A.; software, F.B.M.; validation, F.B.M., L.S., and S.K.; formal analysis, F.B.M.; investigation, F.B.M.; resources, D.S.A. and L.F.; data curation, F.B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B.M.; writing—review and editing, F.B.M., L.S., S.K., L.F., and D.S.A.; visualization, F.B.M.; supervision, D.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan (HUM00268370 and date of approval).”.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.:.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.:

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GBV |

Gender Based Violence |

| IPV |

Intimate Partenr Violence |

| I-MOVE |

Motivators and Resources for Trauma Recovery |

| EFA |

Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| SOMI |

Sense of Meaning Inventory |

| GBV-HEAL |

Healing after Gender Based Violence |

| CSE-T |

Coping Self-Efficacy Trauma |

| BHS-TR |

Barriers to Help Seeking- Trauma Recovery |

| NGBV |

Normalization of Gender Based Violence |

| PTCI-8 |

Post Traumatic Cognition Inventory-8 |

| PHQ-8 |

Patient Health Questionnaire-8 |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Allen-Leap, M.; Hooker, L.; Wild, K.; Wilson, I. M.; Pokharel, B.; Taft, A. Seeking. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- help from primary health-care providers in high-income countries: A scoping review of the experiences of migrant and refugee survivors of domestic violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 24(5), 3715–3731.

- Benight, C. C.; Harding-Taylor, A. S.; Midboe, A. M.; Durham, R. L. Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- and psychometric validation of a domestic violence coping self-efficacy measure (DV-CSE). Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 17(6), 505–508. [CrossRef]

- Benight, C. C.; Shoji, K.; James, L. E.; Waldrep, E. E.; Delahanty, D. L.; Cieslak, R. 2015.

-

Trauma coping self-efficacy: A context-specific self-efficacy measure for traumatic stress; Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy: Psychological Trauma; Volume 7, 6, p. 591.

- Bryngeirsdottir, H. S.; Halldorsdottir, S. “I’ma winner, not a victim”: The facilitating. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- factors of post-traumatic growth among women who have suffered intimate partner violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(3), 1342. [CrossRef]

- Bryant-Davis, T.; Wong, E. C. Faith to move mountains: Religious coping. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- spirituality, and interpersonal trauma recovery. American Psychologist 68(8), 675. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, B. M. Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows; Sage, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D. J. Women's experiences of self-compassion in coping with sexual. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- problems following a sexual assault.

- Campbell, R.; Mannell, J. Conceptualizing the agency of survivors of gender-based. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- violence: The importance of the socio-ecological context. Global Public Health 11(1–2), 1–16.

- Cerny, B. A.; Kaiser, H. F. A study of a measure of sampling adequacy for factor-. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- analytic correlation matrices. Multivariate Behavioral Research 12(1), 43–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, A. B.; Osborne, J. W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 10(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, C.; Martin, S. L.; Wood, K.; Brooks, C. Themes of healing and. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- posttraumatic growth in women survivors’ narratives of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36(5–6), NP2697–NP2724. [CrossRef]

- Haahr, M. True random number service. n.d. Available online: https://www.random.org.

- Hair, J. F.; Black, W. C.; Babin, B. J.; Anderson, R. E. Multivariate data analysis 2014.

-

Pearson Education; ed.

- Hansen, M.; Andersen, T. E.; Armour, C.; Elklit, A.; Palic, S.; Mackrill, T. PTSD-8: A. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- short PTSD inventory. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health: CP & EMH 6, 101.

- Herman, J. L. Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to 1997, 27.

-

political terror; Basic Books.

- Jeffries, S.; Menih, H.; Rathus, Z.; Field, R. Domestic and family violence and private. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- family report writing practice in the Australian family law system: A study. Bond Law Review 34, 167. [CrossRef]

- Karakurt, G.; Koç, E.; Katta, P.; Jones, N.; Bolen, S. D. Treatments for female victims. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- of intimate partner violence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 13, 793021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th ed.; The, 2016. [Google Scholar]

-

Guilford Press.

- Koutra, K.; Burns, C.; Sinko, L.; Kita, S.; Bilgin, H.; Arnault, D. S. Trauma recovery. 2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- rubric: A mixed-method analysis of trauma recovery pathways in four countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(16), 10310. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T. W.; Spitzer, R. L.; Williams, J. B.; Berry, J. T.; Mokdad, A. H. 2009.

- The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders 114(1–3), 163–173. [CrossRef]

- Magaard, J. L.; Seeralan, T.; Schulz, H.; Brütt, A. L. Factors associated with help-. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- seeking behaviour among individuals with major depression: A systematic review. PloS One 12(5), e0176730.

- Marsh, H. W.; Hau, K. T.; Grayson, D. Goodness of fit in structural equation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

-

Contemporary Psychometrics; pp. 275–340.

- AUTHOR, F. B.; Saint Arnault, D. Protective factors affecting trauma recovery among. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- female South Asian immigrant intimate partner violence survivors: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 25(4), 2927–2941. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AUTHOR, F. B.; Koutra, K.; Rodelli, M.; Arnault, D. S. Psychometric evaluation of a. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- multicultural instrument: Normalization of gender-based violence against women scale. Journal of Family Violence 1–13. [CrossRef]

- AUTHOR, F. B.; Sinko, L.; Saint Arnault, D. Development and validation of. [PubMed]

- the Motivators and Resources for Trauma Recovery (I-MOVE) Scale for gender-based. [CrossRef]

- violence survivors. Manuscript submitted for publication to Nursing Research.

- Price, M.; Szafranski, D. D.; van Stolk-Cooke, K.; Gros, D. F. Investigation of. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- abbreviated 4- and 8-item versions of the PTSD Checklist 5. Psychiatry Research 239, 124–130. [CrossRef]

- Reid, R. J.; Bonomi, A. E.; Rivara, F. P.; Anderson, M. L.; Fishman, P. A.; Carrell, D. S.

- Thompson, R. S. Intimate partner violence among men: Prevalence, chronicity. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- and health effects. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 34(6), 478–485.

- Sabri, B.; Rai, A.; Rameshkumar, A. Violence against women in India: An analysis of. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- correlates of domestic violence and barriers and facilitators of access to resources for support. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work 19(6), 700–729. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint Arnault, D.; Zonp, Z. Understanding help-seeking barriers after gender-based. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- violence: Validation of the barriers to help seeking-trauma version (BHS-TR). Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 37, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Saint Arnault, D. M.; Zonp, Z. Revising the original Antonovsky sense of coherence. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- concepts: A mixed method development of the sense of meaning inventory (SOMI). Sexes 5(4), 596–610. [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, L.; Catalán, H. E. N. Attitudes towards domestic violence in 49 low-and. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- middle-income countries: A gendered analysis of prevalence and country-level correlates.

-

PloS One 13(10), e0206101.

- Sinko, L.; Saint Arnault, D. Finding the strength to heal: Understanding recovery after. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- gender-based violence. Violence Against Women 26(12–13), 1616–1635.

- Sinko, L.; Dubois, C.; Thorvaldsdottir, K. B. Measuring healing and recovery after. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- gender-based violence: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 25(4), 2907–2926. [CrossRef]

- Sinko, L.; Schaitkin, C.; Saint Arnault, D. The healing after gender-based violence. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- scale (GBV-heal): An instrument to measure recovery progress in women-identifying survivors. Global Qualitative Nursing Research 8, 2333393621996679. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. G.; Calhoun, L. G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry 15(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Wright, E. N.; Anderson, J.; Phillips, K.; Miyamoto, S. Help-seeking and barriers to. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- care in intimate partner sexual violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 23(5), 1510–1528. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).