Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Culturing of Human Monocytes and Differentiation into Monocyte-Derived Macrophages

2.3. ZIKV Infection and Treatments

2.4. RNA Isolation, Library Preparation, and miRNA-Seq

2.5. Read Alignment and Differential miRNA Expression Analysis

2.6. Read Alignment and Differential lncRNA Expression Analysis

2.7. mRNA Differential Expression

2.8. VDR Motif Analysis

2.9. Gene Enrichment Analysis

2.10. miRNA Target Prediction

2.11. Construction of the ceRNA Network

2.12. lncRNA-mRNA Correlation

3. Results

3.1. Vitamin D–Mediated Regulation of Non-Coding RNA Networks in ZIKV-Infected Macrophages

3.1.1. Vitamin D-Mediated Modulation of lncRNA Expression in ZIKV-Infected MDMs

3.1.2. Vitamin D Modulates Cis-Acting lncRNAs to Regulate Gene Expression

3.1.3. Vitamin D Modulates miRNA Expression in ZIKV-Infected Macrophages

3.1.4. Vitamin D-Regulated miRNAs Modulate Key Biological Processes in ZIKV-Infected Macrophages

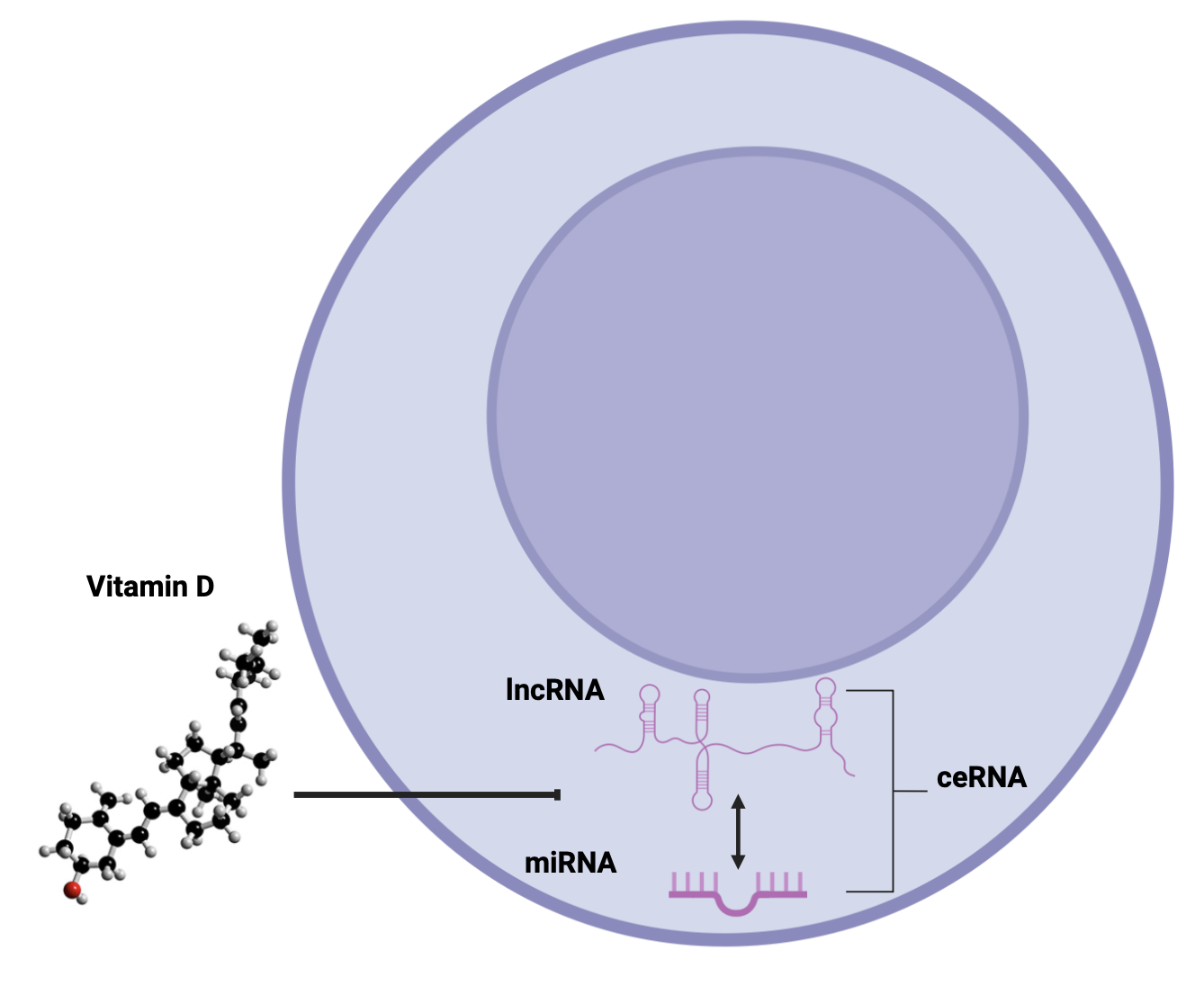

3.1.5. Regulation of Gene Expression by Vitamin D via Competing Endogenous RNA Mechanisms in ZIKV-Infected Macrophages: A Network Approach of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA Interactions

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VitD | Vitamin D |

| ZIKV | Zika virus |

| MDMs | Monocyte-derived macrophages |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding RNAs |

| miRNAs | MicroRNAs |

| ceRNA | Competing endogenous RNA |

| Kb | Kilobases |

| ChIP-Seq | Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

References

- Igbinosa, II; Rabe, IB; Oduyebo, T; Rasmussen, SA. Zika Virus: Common Questions and Answers. Am Fam Physician 2017, 95, 507–513. [Google Scholar]

- Cerbino-Neto, J; Mesquita, EC; Souza, TML; Parreira, V; Wittlin, BB; Durovni, B; et al. Clinical Manifestations of Zika Virus Infection, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 2016, 22, 1318–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazear, HM; Diamond, MS. Zika Virus: New Clinical Syndromes and Its Emergence in the Western Hemisphere. J Virol 2016, 90, 4864–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A; Ponia, SS; Tripathi, S; Balasubramaniam, V; Miorin, L; Sourisseau, M; et al. Zika Virus Targets Human STAT2 to Inhibit Type I Interferon Signaling. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trobaugh, DW; Klimstra, WB. MicroRNA Regulation of RNA Virus Replication and Pathogenesis. Trends Mol Med 2017, 23, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, JS; Hewison, M. Unexpected actions of vitamin D: new perspectives on the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2008, 4, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kow, CS; Hadi, MA; Hasan, SS. Vitamin D Supplementation in Influenza and COVID-19 Infections Comment on: “Evidence that Vitamin D Supplementation Could Reduce Risk of Influenza and COVID-19 Infections and Deaths” Nutrients 2020, 12(4), 988. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, PT; Stenger, S; Li, H; Wenzel, L; Tan, BH; Krutzik, SR; et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science 2006, 311, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, GJ; Ramírez-Mejía, JM; Castillo, JA; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Vitamin D modulates expression of antimicrobial peptides and proinflammatory cytokines to restrict Zika virus infection in macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 119, 110232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn, JL; Chang, HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem 2012, 81, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J; Hu, J; Chen, J-L. lncRNAs regulate the innate immune response to viral infection. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2016, 7, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ala, U. Competing Endogenous RNAs, Non-Coding RNAs and Diseases: An Intertwined Story. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesana, M; Cacchiarelli, D; Legnini, I; Santini, T; Sthandier, O; Chinappi, M; et al. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell 2011, 147, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, GJ; Ramírez-Mejía, JM; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Vitamin D boosts immune response of macrophages through a regulatory network of microRNAs and mRNAs. J Nutr Biochem 2022, 109, 109105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, GJ; Ramírez-Mejía, JM; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms that regulate the genetic program in Zika virus-infected macrophages. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2022, 153, 106312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberán-Soler, S; Vo, JM; Hogans, RE; Dallas, A; Johnston, BH; Kazakov, SA. Decreasing miRNA sequencing bias using a single adapter and circularization approach. Genome Biol 2018, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrasi, AC; Fernandez, GJ; Grotto, RMT; Silva, GF; Goncalves, J; Costa, MC; et al. New LncRNAs in Chronic Hepatitis C progression: from fibrosis to hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 9886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaide, M; Ishmakej, A; Brown, C; Mazzella, M; Agosta, P; Perez-Cruet, M; et al. The potential role of integrin alpha 6 in human mesenchymal stem cells. Front Genet 2022, 13, 968228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z; Tan, M; Chen, G; Li, Z; Lu, X. LncRNA SOX2-OT is a novel prognostic biomarker for osteosarcoma patients and regulates osteosarcoma cells proliferation and motility through modulating SOX2. IUBMB Life 2017, 69, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q; Wang, B; Zhao, H; Wang, W; Wang, P; Deng, Y. LncRNA promoted inflammatory response in ischemic heart failure through regulation of miR-455-3p/TRAF6 axis. Inflamm Res 2020, 69, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y; Zhang, D; Zhang, H; Hou, L; Wang, Z; Yang, L; et al. Construction of a ferroptosis-related five-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis and immune response in thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int 2022, 22, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, M; Takarada, S; Miyao, N; Nakaoka, H; Ibuki, K; Ozawa, S; et al. G0S2 regulates innate immunity in Kawasaki disease via lncRNA HSD11B1-AS1. Pediatr Res 2022, 92, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, EA; El Sayed, IE; Gabber, MKR; Ghobashy, EAE; Al-Sehemi, AG; Algarni, H; et al. Are Antisense Long Non-Coding RNA Related to COVID-19? Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q; Wang, J; Cui, N; Liu, X; Wang, H. Autophagy-related long non-coding RNA signature for potential prognostic biomarkers of patients with cervical cancer: a study based on public databases. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y; Wang, H-T; Zheng, X-F; Huang, X; Meng, J-Z; Huang, J-P; et al. Autophagy-related long non-coding RNA prognostic model predicts prognosis and survival of melanoma patients. World J Clin Cases 2022, 10, 3334–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L; Zhang, H; Ren, P; Sun, X. LncRNA SLC9A3-AS1 knockdown increases the sensitivity of liver cancer cell to triptolide by regulating miR-449b-5p-mediated glycolysis. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, P; Mishra, P; Mehta, P; Soni, J; Gupta, R; Tarai, B; et al. Transcriptomic study reveals lncRNA-mediated downregulation of innate immune and inflammatory response in the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination breakthrough infections. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1035111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C; Wu, X; Li, C; Wang, C; Liu, J; Luo, Q. A cuproptosis-associated long non-coding RNA signature for the prognosis and immunotherapy of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Biomolecules & Biomedicine 2023, 23, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J; Guo, J; Zhu, L; Zhou, Y; Tong, J. Comprehensive analyses of glycolysis-related lncRNAs for ovarian cancer patients. J Ovarian Res 2021, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seroussi, E; Kedra, D; Pan, HQ; Peyrard, M; Schwartz, C; Scambler, P; et al. Duplications on human chromosome 22 reveal a novel Ret Finger Protein-like gene family with sense and endogenous antisense transcripts. Genome Res 1999, 9, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X; Geng, J; Li, X; Wan, J; Liu, J; Zhou, Z; et al. Long Noncoding RNA LINC01619 Regulates MicroRNA-27a/Forkhead Box Protein O1 and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Podocyte Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 29, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, GJ; Castillo, JA; Giraldo, DM; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Vitamin D Regulates the Expression of Immune and Stress Response Genes in Dengue Virus-infected Macrophages by Inducing Specific MicroRNAs. Microrna 2021, 10, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neme, A; Seuter, S; Carlberg, C. Selective regulation of biological processes by vitamin D based on the spatio-temporal cistrome of its receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 2017, 1860, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, S; Alves-Guerra, M-C; Mozo, J; Miroux, B; Cassard-Doulcier, A-M; Bouillaud, F; et al. The biology of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Diabetes 2004, 53 Suppl 1, S130–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, WJ; Shimizu, T; Shindou, H. Lysophospholipid acyltransferases orchestrate the compositional diversity of phospholipids. Biochimie 2023, 215, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, SE; Gharib, SA; Bench, EM; Sussman, SW; Wang, RT; Rims, C; et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 moderates the proinflammatory status of macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013, 49, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, NR; Azevedo R do S da, S; Kraemer, MUG; Souza, R; Cunha, MS; Hill, SC; et al. Zika virus in the Americas: Early epidemiological and genetic findings. Science 2016, 352, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao-Lormeau, V-M; Blake, A; Mons, S; Lastère, S; Roche, C; Vanhomwegen, J; et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet 2016, 387, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moreno, J; Hernandez, JC; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Effect of high doses of vitamin D supplementation on dengue virus replication, Toll-like receptor expression, and cytokine profiles on dendritic cells. Mol Cell Biochem 2020, 464, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemoto, Y; Nishimura, K; Hayakawa, A; Sawada, T; Amano, R; Mori, J; et al. A long non-coding RNA as a direct vitamin D target transcribed from the antisense strand of the human HSD17B2 locus. Biosci Rep 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrzad, MK; Gharehgozlou, R; Fadaei, S; Hajian, P; Mirzaei, HR. Vitamin D and Non-coding RNAs: New Insights into the Regulation of Breast Cancer. Curr Mol Med 2021, 21, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R; Yang, Y; Wang, L; Shi, Q; Ma, H; He, S; et al. SOX2-OT Binds with ILF3 to Promote Head and Neck Cancer Progression by Modulating Crosstalk between STAT3 and TGF-β Signaling. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J; Ren, T; Cao, S; Zheng, S; Hu, X; Hu, Y; et al. HBx-related long non-coding RNA DBH-AS1 promotes cell proliferation and survival by activating MAPK signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 33791–33804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q; Matsuura, K; Kleiner, DE; Zamboni, F; Alter, HJ; Farci, P. Analysis of long noncoding RNA expression in hepatocellular carcinoma of different viral etiology. J Transl Med 2016, 14, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J; Ren, T; Cao, S; Zheng, S; Hu, X; Hu, Y; et al. HBx-related long non-coding RNA DBH-AS1 promotes cell proliferation and survival by activating MAPK signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 33791–33804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C; Dai, Y; Wu, Z; Yang, Q; He, S; Zhang, X; et al. SMAD3/SP1 complex-mediated constitutive active loop between lncRNA PCAT7 and TGF-β signaling promotes prostate cancer bone metastasis. Mol Oncol 2020, 14, 808–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J; Zhang, S; Luo, M. LncRNA PCAT7 promotes the malignant progression of breast cancer by regulating ErbB/PI3K/Akt pathway. Future Oncol 2021, 17, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K; Zhang, L; Li, X; Zhao, J. High expression of lncRNA HSD11B1-AS1 indicates favorable prognosis and is associated with immune infiltration in cutaneous melanoma. Oncol Lett 2022, 23, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q; Xia, Y. c-Jun, at the crossroad of the signaling network. Protein Cell 2011, 2, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadillo, E; Taniguchi-Ponciano, K; Lopez-Macias, C; Carvente-Garcia, R; Mayani, H; Ferat-Osorio, E; et al. A Shift Towards an Immature Myeloid Profile in Peripheral Blood of Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients. Arch Med Res 2021, 52, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsuta, T; Langer, T. Intramitochondrial phospholipid trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2017, 1862, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, MB; Hong, HS; Michmerhuizen, BC; Lawrence, A-LE; Zhang, L; Knight, JS; et al. Cardiolipin coordinates inflammatory metabolic reprogramming through regulation of Complex II disassembly and degradation. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eade8701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potting, C; Tatsuta, T; König, T; Haag, M; Wai, T; Aaltonen, MJ; et al. TRIAP1/PRELI complexes prevent apoptosis by mediating intramitochondrial transport of phosphatidic acid. Cell Metab 2013, 18, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeller, MR; Herrera-Rodriguez, S; Ma, W; Ortiz-Quintero, B; Rangel, R; Candé, C; et al. Vital function of PRELI and essential requirement of its LEA motif. Cell Death Dis 2010, 1, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, BY; Cho, MH; Kim, KJ; Cho, KJ; Kim, SW; Kim, HS; et al. Effects of PRELI in Oxidative-Stressed HepG2 Cells. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2015, 45, 419–425. [Google Scholar]

- Guil, S; Esteller, M. Cis-acting noncoding RNAs: friends and foes. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012, 19, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reales-Calderón, JA; Aguilera-Montilla, N; Corbí, ÁL; Molero, G; Gil, C. Proteomic characterization of human proinflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages and their response to Candida albicans. Proteomics 2014, 14, 1503–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, DH; Raynal, MC; Tejwani, GA; Cayre, YE. Activation of the fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase gene by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 during monocytic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988, 85, 6904–6908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W; Zhu, Y; Zhang, S; Zhang, W; Si, Z; Bai, Y; et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D regulates macrophage activation through FBP1/PKR and ameliorates arthritis in TNF-transgenic mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2023, 228, 106251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, K; Umesono, K; Kikawa, Y; Shigematsu, Y; Taketo, A; Mayumi, M; et al. Identification of a response element for vitamin D3 and retinoic acid in the promoter region of the human fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase gene. J Biochem 2000, 127, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besançon, F; Just, J; Bourgeade, MF; Van Weyenbergh, J; Solomon, D; Guillozo, H; et al. HIV-1 p17 and IFN-gamma both induce fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase. J Interferon Cytokine Res 1997, 17, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diosa-Toro, M; Echavarría-Consuegra, L; Flipse, J; Fernández, GJ; Kluiver, J; van den Berg, A; et al. MicroRNA profiling of human primary macrophages exposed to dengue virus identifies miRNA-3614-5p as antiviral and regulator of ADAR1 expression. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0005981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleda, JF; Fernandez, GJ; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Vitamin D-mediated attenuation of miR-155 in human macrophages infected with dengue virus: Implications for the cytokine response. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2019, 69, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y; Wang, W; Zou, Z; Fan, Q; Hu, Z; Feng, Z; et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 released from macrophages induced by hepatitis C virus promotes monocytes migration. Virus Res 2017, 240, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhorukov, VN; Khotina, VA; Bagheri Ekta, M; Ivanova, EA; Sobenin, IA; Orekhov, AN. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Macrophages: The Vicious Circle of Lipid Accumulation and Pro-Inflammatory Response. Biomedicines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista-Gonzalez, A; Vidal, R; Criollo, A; Carreño, LJ. New Insights on the Role of Lipid Metabolism in the Metabolic Reprogramming of Macrophages. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S; Yan, W; Wang, SE; Baltimore, D. Dual mechanisms of posttranscriptional regulation of Tet2 by Let-7 microRNA in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 12416–12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magryś, A; Bogut, A. MicroRNA hsa-let-7a facilitates staphylococcal small colony variants survival in the THP-1 macrophages by reshaping inflammatory responses. Int J Med Microbiol 2021, 311, 151542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S; Yan, W; Wang, SE; Baltimore, D. Dual mechanisms of posttranscriptional regulation of Tet2 by Let-7 microRNA in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 12416–12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G; Zhou, C; Ma, K; Zhao, W; Xiong, Q; Yang, L; et al. MiRNA-494 enhances M1 macrophage polarization via Nrdp1 in ICH mice model. J Inflamm (Lond) 2020, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ingen, E; Foks, AC; Woudenberg, T; van der Bent, ML; de Jong, A; Hohensinner, PJ; et al. Inhibition of microRNA-494-3p activates Wnt signaling and reduces proinflammatory macrophage polarization in atherosclerosis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2021, 26, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, G; Zhou, C; Ma, K; Zhao, W; Xiong, Q; Yang, L; et al. MiRNA-494 enhances M1 macrophage polarization via Nrdp1 in ICH mice model. J Inflamm (Lond) 2020, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S; He, K; Zhou, W; Cao, J; Jin, Z. miR-494-3p regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in RAW264.7 cells by targeting PTEN. Mol Med Rep 2019, 19, 4288–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A; Rastogi, M; Singh, SK. Zika virus NS1 suppresses the innate immune responses via miR-146a in human microglial cells. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 193, 2290–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, J; Wu, S; Xie, H; Li, Y; Yang, Z; Wu, X; et al. miR-146a Inhibits dengue-virus-induced autophagy by targeting TRAF6. Arch Virol 2017, 162, 3645–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khongnomnan, K; Makkoch, J; Poomipak, W; Poovorawan, Y; Payungporn, S. Human miR-3145 inhibits influenza A viruses replication by targeting and silencing viral PB1 gene. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2015, 240, 1630–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadkhani, A; Bastani, F; Khorrami, S; Ghanbari, R; Eghtesad, S; Sharafkhah, M; et al. Negative Association of Plasma Levels of Vitamin D and miR-378 With Viral Load in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Infection. Hepat Mon 2015, 15, e28315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W-T; Zhang, Q. MicroRNA-708-5p regulates mycobacterial vitality and the secretion of inflammatory factors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages by targeting TLR4. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23, 8028–8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P; Song, H; Gao, J; Li, B; Liu, Y; Wang, Y. Vitamin D (1,25-(OH)2D3) regulates the gene expression through competing endogenous RNAs networks in high glucose-treated endothelial progenitor cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2019, 193, 105425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M; Wang, H; Ning, X; Jia, F; Zhang, L; Pan, Y; et al. Functional analysis of differentially expressed long non-coding RNAs in DENV-3 infection and antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infection. Virus Res 2022, 319, 198883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L; Liang, L; Fang, Q; Wang, J. Construction of novel lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA ceRNA networks associated with prognosis of hepatitis C virus related hepatocellular carcinoma. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D; Podder, S. Deregulation of ceRNA Networks in Frontal Cortex and Choroid Plexus of Brain during SARS-CoV-2 Infection Aggravates Neurological Manifestations: An Insight from Bulk and Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analyses. Adv Biol 2022, 6, e2101310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C; Gu, T; Li, Y; Zhang, Q. Depression of long non-coding RNA SOX2 overlapping transcript attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced injury in bronchial epithelial cells via miR-455-3p/phosphatase and tensin homolog axis and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 13643–13653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodangeh, F; Sadeghi, Z; Maleki, P; Raheb, J. Long non-coding RNA SOX2-OT enhances cancer biological traits via sponging to tumor suppressor miR-122-3p and miR-194-5p in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W; Peng, F; Cui, X; Li, J; Sun, C. LncRNA SOX2OT facilitates LPS-induced inflammatory injury by regulating intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) via sponging miR-215-5p. Clin Immunol 2022, 238, 109006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J; Li, D; Zhang, X; Li, C; Zhu, F. Long noncoding RNA SLC9A3-AS1 increases E2F6 expression by sponging microRNA-486-5p and thus facilitates the oncogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncol Rep 2021, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X; Huang, M; Chen, M; Chen, X. lncRNA SLC9A3-AS1 Promotes Oncogenesis of NSCLC via Sponging microRNA-760 and May Serve as a Prognosis Predictor of NSCLC Patients. Cancer Manag Res 2022, 14, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, JE; Kim, HW; Yun, SH; Kim, SJ. Ginsenoside Rh2 upregulates long noncoding RNA STXBP5-AS1 to sponge microRNA-4425 in suppressing breast cancer cell proliferation. J Ginseng Res 2021, 45, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, S; Wang, C; Wang, S; Zhang, H; Zhang, Y. LncRNA STXBP5-AS1 suppressed cervical cancer progression via targeting miR-96-5p/PTEN axis. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 117, 109082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M; Chen, Y; Wang, S; Liu, S; Rai, KR; Chen, B; et al. Long Noncoding RNA IFITM4P Regulates Host Antiviral Responses by Acting as a Competing Endogenous RNA. J Virol 2021, 95, e0027721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).