1. Introduction

The diagnostic and therapeutic approaches of many human pathologies have been substantially modified by the advent of extraordinary progress in the field of molecular and cellular biology. The validation of innovative imaging methods whose purpose is to visualize and quantify complex processes in vivo represent the future development in the diagnostic and therapeutic field of nuclear medicine. The future of Nuclear Medicine is therefore an effective use of radioactivity, which allows us to get more and more into the mechanisms that generate and maintain the disease and eliminate them or, if possible, to correct them [

1].

To visualize and study the lymphatic system, a nuclear medicine procedure is used, which uses a small quantity of radioactive particles administered subcutaneously and whose path is followed with special equipment capable of revealing and rendering in an image the fate of that tracer in the lymphatic system. Over the years, this procedure, called lymphoscintigraphy, has evolved and represents now the “gold standard” for diagnosis of lymphedema. But an important limitation of lymphoscintigraphy is the lack of procedural standardization. This is the first step toward certification of lymphoscintigraphy in the field of nuclear medicine of the third millennium.

2. Lymphedema

As well known lymphedema is a chronic and debilitating disease, often misdiagnosed, treated too late or not treated at all. Yet, in the evaluation of lymphedema, advances in imaging techniques, surgical treatments, and therapies targeting the underlying mechanisms have led to new and exciting developments, despite the underestimation of lymphedema as a chronic, disabling disease. Lymphatic injury, infection or congenital anomaly cause compromised lymphatic transport which causes lymphedema.

Lymphedema is far from rare. It's a very common disease, affecting approximately 1 in 20 people, that is 300 million worldwide [

2,

3]. Primary lymphedema may be a non-hereditary or genetic condition; it can be one-sided or bilateral; it can occur at birth, puberty or adulthood [

4]. The onset of edema is generally spontaneous without a history of trauma, surgery, or radiotherapy and more often occurs in patients before 30 or 35 years of age.

Secondary lymphedema occurs with external factors damaging lymphatic drainage pathways [

5]. As we will see later, the causes of secondary lymphedema can be varied: inflammation of the lymphatics that becomes chronic and compromises the drainage function, compression and obstruction by masses of various kinds, which also compromise the outflow of the lymphatics, and even the after-effects of surgery that can alter the anatomy of the affected region, preventive removal of lymph nodes (the most classic example being edema of the homologous limb in the case of breast cancer) and after-effects of external beam radiotherapy.

The two types of lymphedema share the dysfunction of lymphatic endothelial cells that are involved in the absorption and transport of the lymph. The alteration of the lymphatic transport alters the clearance of the fluid from interstitium and macromolecules, thus affecting the osmotic and hydrostatic gradient maintained by the blood vessels [

5].

Lymphedema is found in both sexes, although women are investigated for this disease more often than men, also due to the evident aesthetic damage [

6]. Epidemiological patterns of lymphedema depend on different etiologies according to geographical and socio-economic factors. Chronic lymphedema in regions of low and medium economic status generally depends by parasitic infections caused by filarial nematodes or non-filarial etiologies such as podoconiosis [

7]. In developed countries, however, lymphedema is secondary to oncological problems, either due to the local action of neoplastic masses that compress the lymphatic drainage pathways, or as a consequence of oncological surgical interventions and, again, as a consequence of oncological external beam radiotherapy [

4,

8].

In many countries lymphedema is still considered a "cosmetic" issue, rather than a chronic, degenerative and debilitating disease. Chronic lymphedema is a progressive disease that significantly affects patients' quality of life [

9,

10]. The Italian Ministry of Health has adopted the guidelines for the National cure for lymphedema and related disorders, after a long period of study with internal and external experts [

11].

3. Lymphoscintigrapy

The stagnation of interstitial blood for the presence of proteins, increases the colloid osmotic pressure, increasing the presence of edematous fluid, causing ischemia and local inflammatory reactions at the basis of chronic lymphatic insufficiency. The diagnosis of lymphedema can be performed almost exclusively with the physical examination: edema, orange peel skin, skin fibrosis, accentuation of skin folds at the metatarsophalangeal joints (sign Stemmers), thinning of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. The diagnosis of lymphedema is not easy, since the disease can also be confused with other clinical manifestations (for example, venous insufficiency edema), but an experienced Lymphologist is usually able to diagnose it with good accuracy. However, to confirm the diagnosis, it is often necessary to resort to specialist imaging tests for an anatomo-functional definition of the pathology, thus the presence of lymphatic insufficiency can be confirmed by imaging techniques [

12].

Lymphangiography has been used for decades to study the normal anatomy of lymphatic vessels, to investigate edema, and to delineate pathological changes in lymph nodes. The contrast medium is injected directly into the lymphatic vessels. Since the primary focus was on neoplastic and metastatic lymph node disease in the pelvis and retroperitoneal space, the injections were limited to the lower limbs [

13]. However, nowadays, both due to the manual difficulties in cannulating the thin lymphatic vessels, with the risk of extravasation of the contrast medium which could cause serious problems up to necrosis, and due to the high dose of radiation supplied, lymphography by means of radiopaque contrast currently has a very limited role.

Lymphoscintigraphy has largely replaced lymphography for the evaluation of the lymphatic system, being currently recommended as the initial diagnostic test by the International Society of Lymphology (ISL) with a grade 1 recommendation and by the American Venous Forum guidelines with a level of evidence B. The possibility offered to nuclear medicine in malfunction of the lymphatic vessels associated with the pathogenesis of many diseases, including lymphedema, fibrosis, inflammation and malignant tumors, allows it to be a primary protagonist in the development of the diagnosis and therapy of complex pathologies, including a series of rare disease [

14].

Lymphoscintigraphy, on the other hand, is considered the best first-line test in patients with lymphedema. The main indication of lymphoscintigraphy is the early detection of impairment of the lymphatic system in patients with clinical suspicion of primary and secondary lymphedema [

12].

Lymphoscintigraphy is confirmed as the "gold standard" procedure for the diagnosis of lymphedema [

15,

16]. This test is not only able to refute or not the doctor's diagnosis, but it can also visually report the status of the lymphatic system, thanks to a precise and function-based imaging technique. By means of lymphoscintigraphy it is possible to see exactly the superficial and deep lymphatic passages, assessing their draining efficiency and also seeing the points where the normal flow of the lymph is interrupted.

In addition to the initial assessment of the severity of the lymphatic flow disorder, serial lymphoscintigraphic examinations may be performed during follow-up to monitor response to treatment and disease progression. In patients diagnosed with primary lymphedema, lymphoscintigraphic evaluation of immediate family members should also be considered to adopt adequate primary prevention measures [

6].

At this point we asked ourselves in the super-technological era that we are experiencing, what the role of lymphoscintigraphy is in the entire diagnostic landscape.

4. Lymphoscintigraphy Clinical Applications

- I.

Lymphedema

The examination, quite simple execution, provides morphological and functional indications in the lymphatic circulation, but it seems necessary to have a good understanding of the clinical information by nuclear physicians and lymphangiologists.

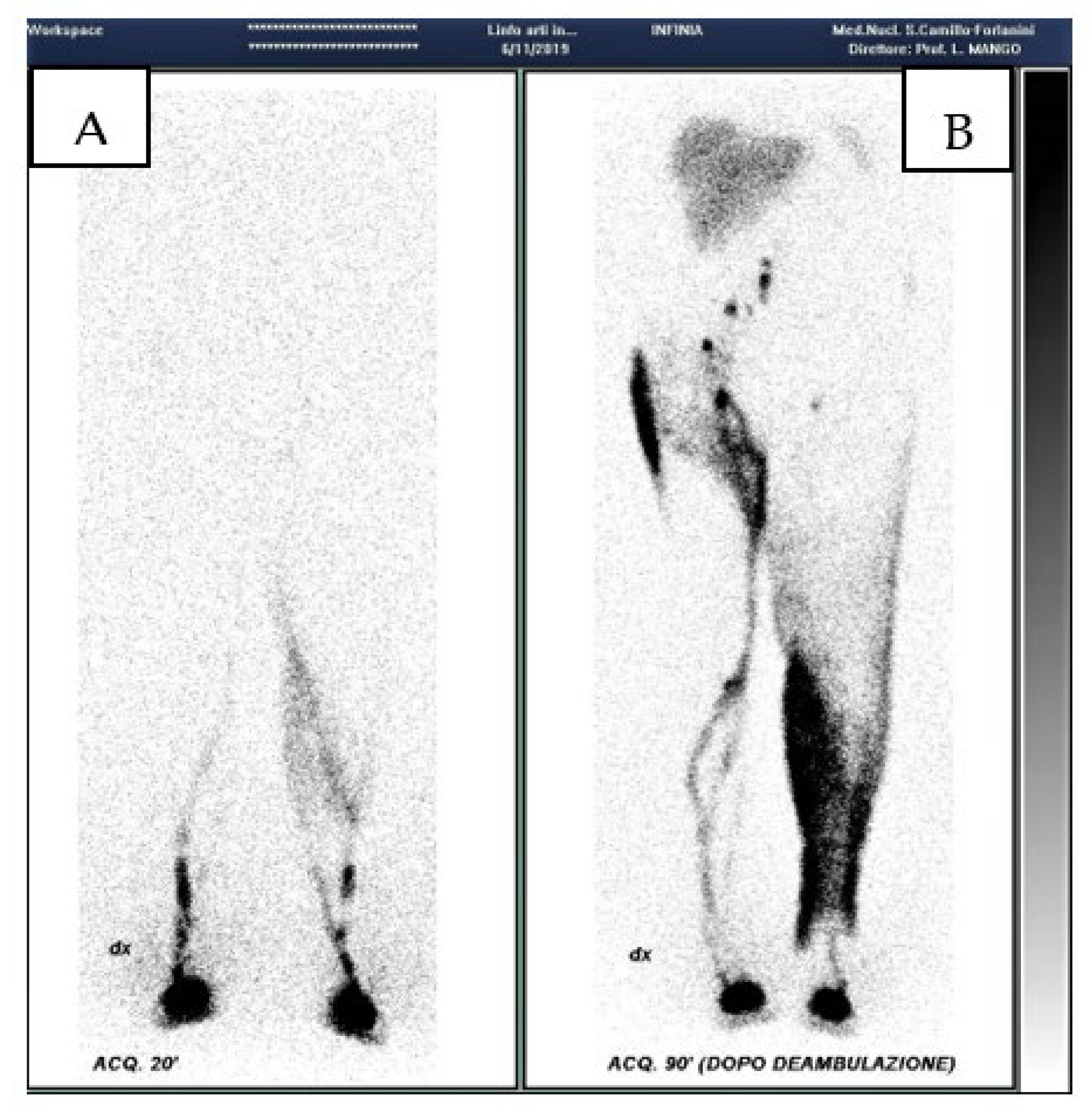

Criteria for the diagnosis of lymphatic dysfunction include delayed, asymmetric or absent visualization of regional lymph nodes, asymmetric visualization of lymphatic channels, collateral lymphatic channels, interrupted vascular structures, and visualization of the lymph nodes of the deep lymphatic c system, not visible in the normal subject. The appearance of tracer outside the main lymph routes, particularly in the skin, so called “dermal back flow”, indicates lymph reflux and suggests proximal obstruction. Poor transit of the tracer from the injection site suggests hypoplasia of the peripheral lymphatic system [

17](

Figure 1). In a cohort of 465 consecutive patients, we observed [

18] that the dermal back flow generally is proportioned to the clinical stage of lymphedema; it partially regressing after treatment and can be present also with healthy lymphatic station (for example in the post phlebitic syndrome or in iatrogenic lesions of lymphatic trunks).

Lymphoscintigraphy is also used to define the clinical characteristics, investigations, management and outcomes of lymphedema in pediatric patients [

19,

20] In particular Paudel et al. [

21] have very recently illustrated a case of primary lymphedema, with aplasia and hypoplasia of the lymphatic channels, a rather rare pathology that is often not diagnosed, thanks to lymphoscintigraphy.

Regarding the surgical treatment of lymphedema, a new technique is appearing on the horizon and it is possible to monitor its results through lymphoscintigraphy, as well as during the course of usual techniques such as microsurgical LVA [

20], Non-Vascularized Lymph Node Transfer (NVLNT). This new technique, aims to address lymphatic drainage deficit in lymphedema in a minimally invasive manner. The NVLNT technique consists of a procedure by which lymph nodes are taken from a distant site, such as the groin or armpit, and grafted into the lymphedematous site promoting lymphangiogenesis [

22]. Trevis et al in a study demonstrated the validity of this technique evaluated by means of lymphoscintigraphy [

23].

Functional lymphatic changes detected by lymphoscintigraphy after external beam radiation therapy can predict the development of upper limb lymphedema [

24].

In patients with stage I extremity lymphedema, lymphoscintigraphy can predict the long-term response to physical therapy. Lymphoscintigraphy has long been shown to be an effective and objective method of assessing response to treatment using lymphatic drainage and physical therapies [

25].

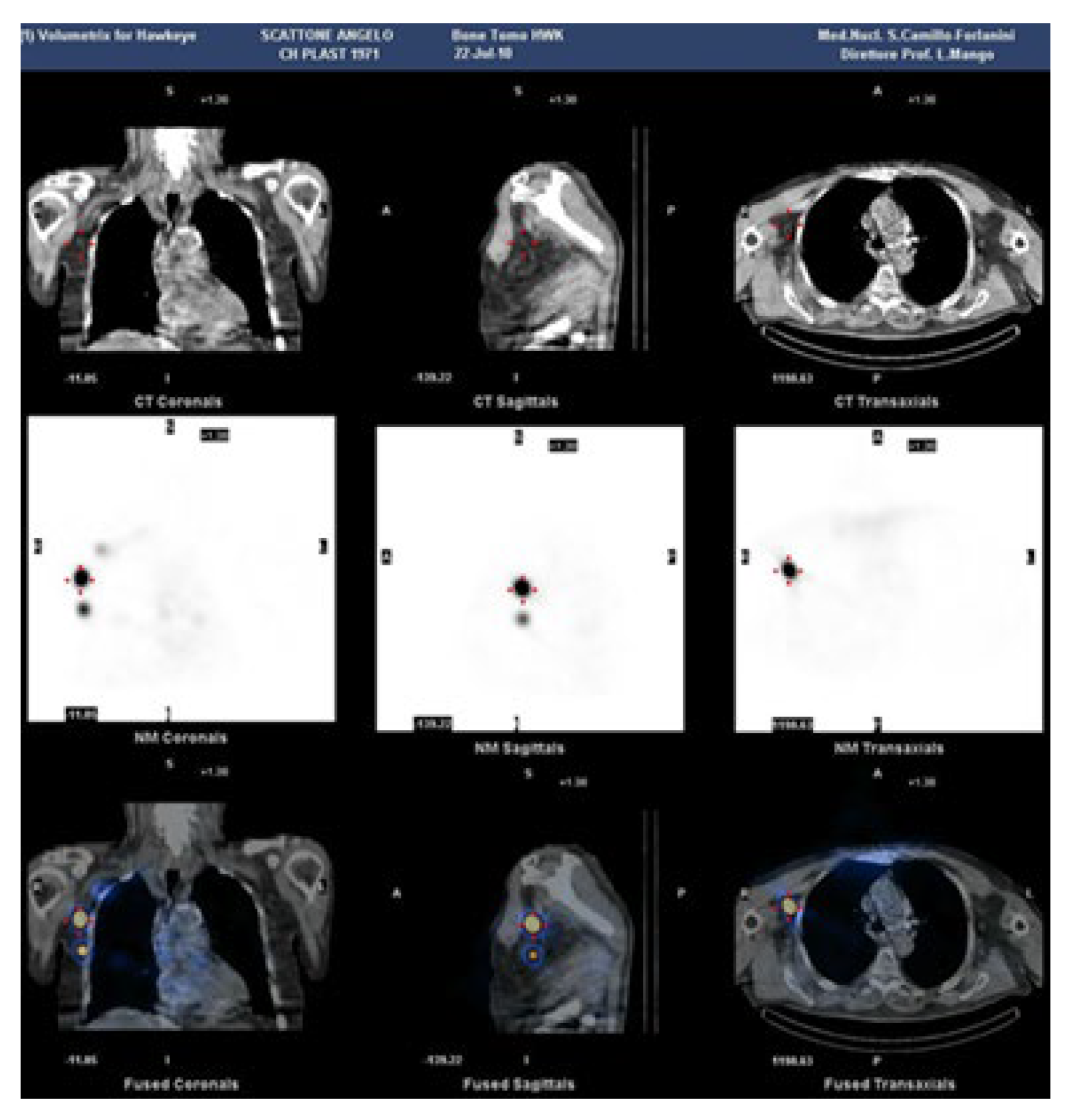

The use of tomographic projections (SPECT) in addition to planar ones for lymphoscintigraphy certainly provides greater information on deep alterations. But the real breakthrough came with the use of hybrid machines capable of simultaneously combining CT and SPECT imaging, to offer functional information (with SPECT) along with anatomical images (CT) [

26].

Lymphoscintigraphy SPECT-CT of the axillary region, has been employed to evaluate the impact of including, as target volumes in the radiation treatment plan, the lymph nodes involved in arm drainage that might affect lymphedema [

27] (

Figure 2).

Pierre Bourgeois et al. demonstrated the usefulness of lymphoscintigraphy in evaluating lymphatic drainage in a series of patients with facial edema, in particular by adding SPECT-CT findings [

28].

In pediatric patients, lymphoscintigraphy is the main diagnostic tool for clinically suspected congenital lymphatic abnormalities and in the case of edema of the limbs and genitals, chylothorax and chylous ascites [

29].

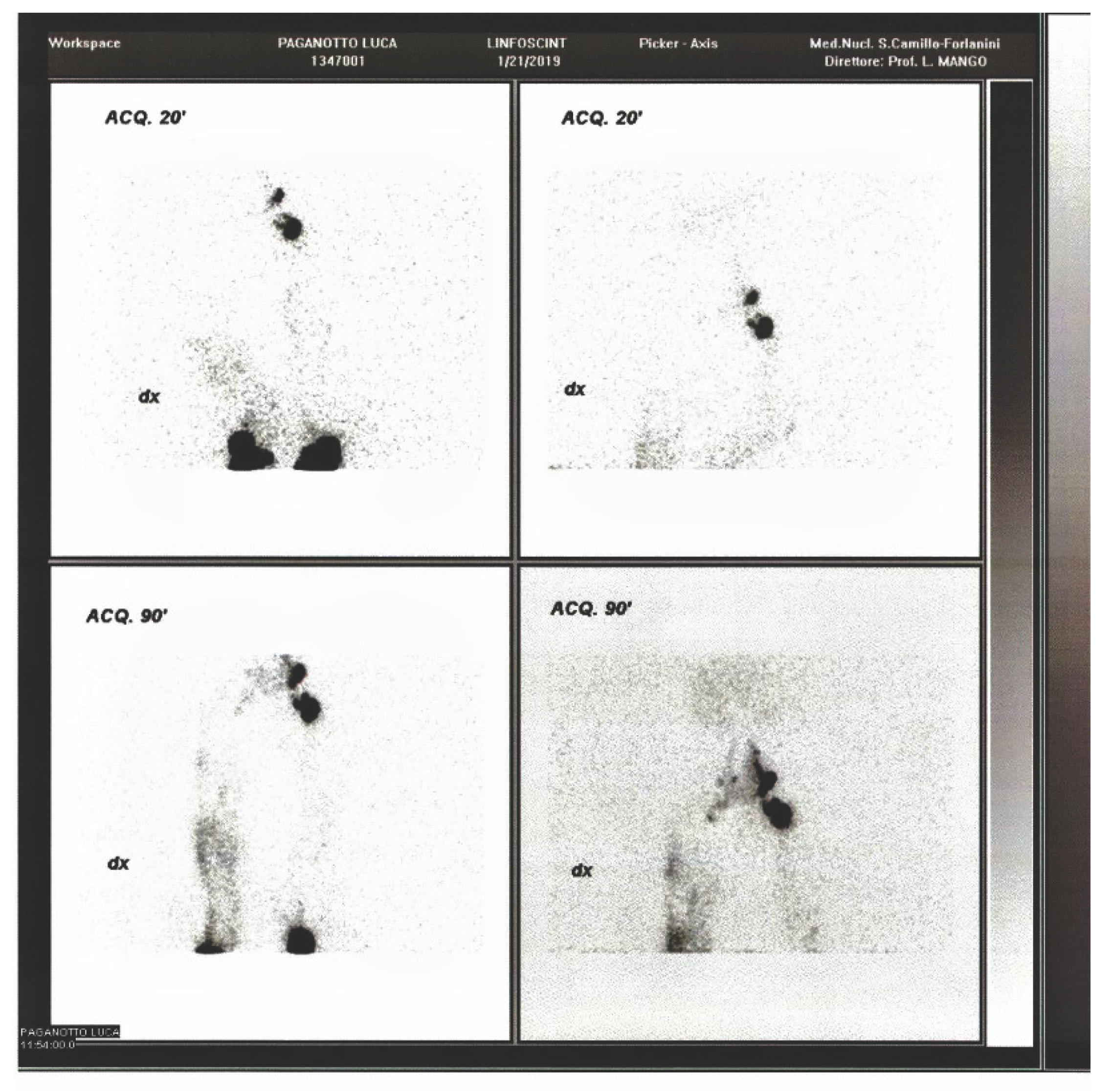

Lymphoscintigraphy offers objective evidence to distinguish lymphatic pathology from non lymphatic causes of extremity edema [

30,

31] (

Figure 3).

- II.

Sentinel lymph node

A preventive use of lymphoscintigraphy is also that of the sentinel lymph node technique, applied in various neoplastic pathologies. Correct application of the method allows avoiding the removal of a large number of lymph nodes and the subsequent appearance of lymphedema due to the scarcity or absence of drainage stations.

Since lymph node metastasis is particularly important in many oncological manifestations, in 1999 Veronesi and Paganelli developed a method for searching and detecting the first tributary lymph node, called sentinel lymph node, of the mammary region in cases of breast cancer [

32].

The concept of the sentinel lymph node had already been introduced in 1977, through lymphography of the penile region [

33] and subsequently Morton and the pathologist Cochran in 1992 developed the innovative concept of “mapping the lymph through the biopsy of the sentinel lymph node” in melanoma [

34], but being able to identify this structure through a simple lymphoscintigraphy and be able to recognize it during surgery for removal and histological examination represented a real turning point in modern oncological surgery, as demonstrated by Veronesi and Paganelli [

32].

Since 1999, the concept of the sentinel lymph node has expanded the boundaries of oncological surgery and its application has extended from the breast to many tumor types such as melanoma, uterine cervix, endometrial cancer, vulvar cancer, penile cancer, colorectal cancer and head and neck cancers. However, its clinical utility in other forms remains to be determined in future studies [

35].

- III.

Particular cases of lymphoscintigraphic application

As previously reported by us, lymphoscintigraphy can also play a role in particular situations involving the lymphatic circulation and lymph nodes [

12].

We have reported there, for example, the case of thoracic duct injury, in which lymphoscintigraphy performed in SPECT-CT documented the location and extent of the lesion [

36].

We have also cited works which showed the non-detection of alterations [

37] in some cases of chyluria and in others the real usefulness [

38].

And again the case of a patient with high fever, acute abdominal pain, and abdominal lymphadenopathy during HIV infection, where lymphoscintigraphy demonstrated thoracic duct obstruction [

39].

Chylous ascites is a rather rare complication following retroperitoneal surgery and lymphoscintigraphy can be a valid diagnostic aid in recognizing it and assessing its extent [

40].

5. Conclusions

So, going back to what was said in the introduction, one of the major goals is reaching a consensus on the procedure. An Italian group of experts met and developed a guideline that appeared valid for the clinical questions, the simplicity and repeatability of the procedure, and the minimal discomfort for the patient [

41]. Other scientific societies have or had already done the same, the EANM in 2014 [

42] and the Korean Society of Nuclear Medicine much more recently in this year [

43]. This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Overall, lymphoscintigraphy appears to consistently have higher sensitivity and specificity than MR lymphangiography [

44]. MR lymphangiography alone achieved a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 91% [

45]. A 2017 study of 227 patients found that lymphoscintigraphy had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 100%, thus confirming, with a slight improvement, the historical trend for this investigation [

46]. Other large lymphoscintigraphy studies conducted in the last decades have achieved sensitivities above 90% and specificities close to 100% and compared to them the diagnostic performance of MRI is lacking [

47].

Recently, other techniques have become a subject of interest in lymphedema imaging, for example the use of near-infrared fluorescence(NIRF) dyes such as indocyanine green(ICG). The problem is that ICG, like all NIRF agents, has obvious depth limitations. In cases of obese patients or in any case when there is abundant subcutaneous tissue, the visualization of the lymphatic vessels by ICG can be difficult, especially for the evaluation of the efficacy of the treatment, for which these patients benefit from the use of lymphoscintigraphy [

48]. To detect primary lymphedema, indocyanine green lymphography perhaps can be used first as a screening examination. But when the results are positive, lympho-scintigraphy is useful to obtain further information.

It is now well established that imaging is a fundamental tool for sustaining progress and one of the fundamental means remains the development of new contrast agents and tracers and imaging tools. Nanoparticles with multimodal imaging capabilities could represent a new horizon for allowing researchers and physicians to obtain even more information. However, further studies are needed to validate the effectiveness of these new technologies compared to more traditional methods and to ensure their complete transposition into the clinical setting.

We can therefore affirm, given all of the above, that lymphoscintigraphy still maintains its solid place in the diagnosis of lymphatic flow disorders in this millennium. A position that, even compared to other methods, allows it to be used in diagnosis, prevention, and the monitoring of therapies, be they surgical, pharmacological, or physical.

This is also because, as mentioned above, it is a non-invasive method, with the exception of targeted radiotracer injections, and has a low complication rate, with few contraindications.

A word of caution regarding radiation exposure, a factor that could disadvantage it compared to non-radiological methods. The main information regarding the effective dose to critical organs from the administration of Tc-99m-labeled colloidal tracers comes from sentinel lymph node lymphoscintigraphy.s. As reported in the manufacturer's notes of the tracer commercially available , the effective dose resulting from a subcutaneous administration of 110 MBq of Tc-99m nanocolloids in an adult patient is 0.44 mSv, with an absorbed dose of 65 mGy to the lymph nodes and 1320 mGy at the injection site. As reported in 2020 by Almujalli et al., The current radiation risk is equivalent to five weeks of exposure to natural background radiation, making it considered a low cancer risk, i.e., one case of cancer for every 105 SPECT/CT lymphoscintigraphy procedures [49].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mango, L. Nuclear Medicine in the Third Millennium. J Nucle Med Clinic Imag 2019, 1(1), 001. [Google Scholar]

- Jaszkul, K. M.; Farrokhi, K.; Castanov, V.; Minkhorst, K.; et al. Global impact of lymphedema on quality of life and society. European Journal of Plastic Surgery 2023, 46(6), 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letellier, M. E.; Ibrahim, M.; Towers, A.; Chaput, G. Incidence of lymphedema related to various cancers. Medical Oncology 2024, 41(10), 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, C. Global incidence of tropical and non-tropical lymphoedemas 1. Int Angiol 1999, 18, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Szuba, A.; Rockson, S.G. Lymphedema: classification, diagnosis and therapy. Vasc Med. 1998, 3(2), 145–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Society of Lymphology(ISL) The. diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2016 consensus document of the international society of lymphology Lymphology 2016, 49, 170–184.

- Wynd, S.; Melrose, W.D.; Durrheim, D.N.; Carron, J.; Gyapong, M. Understanding the community impact of lymphatic filariasis: a review of the sociocultural literature. Bull World Health Organ. 2007, 85(6), 493–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facondo, G.; Bottero, M.; Goanta, L.; Farneti, A.; et al. Incidence and predictors of lower extremity lymphedema after postoperative radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Radiation Oncology 2025, 20(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghian, N.R.; Miller, C.L.; Jammallo, L.S.; O’Toole, J.; Skolny, M.N. Lymphedema following breast cancer treatment and impact on quality of life: a review. Crit Rev OncolHematol 2014, 92, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnane, A.; Hayes, S.C.; Obermair, A.; Monika, J. Quality of life of women with lowerlimb lymphedema following gynecological cancer. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelini, S.; Cestari, M.; Ricci, M.; Leone, A.; et al. Italian Guidelines on Lymphedema: New public regulations. JTAVR 1(2), 119–123. [CrossRef]

- Mango, L.; Ventroni, G.; Michelini, S. Lymphoscintigraphy and clinic. Res Rev Insights 2017, 1(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mango, L.; Mangano, A.M.; Semprebene, A. Lymphoscintigraphy: Preventive, Diagnostic and Prognostic Value. ARC Journal of Radiology and Medical Imaging 2020, 4(2), 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mango, L. Lymphoscintigraphic Indications in the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Secondary Lymphedema. Radiation. 2023, 3(1), 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, M.; Cheng, M-H. Lymphoscintigraphy for the diagnosis of extremity lymphedema: Current controversies regarding protocol, interpretation, and clinical application. J Surg Oncol. 2020, 121, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keo, H.H.; Gretener, S.B.; Staub, D. Clinical and diagnostic aspects of lymphedema. Vasa. 2017, 46(4), 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mango, L.; Michelini, S.; Failla, A.; Moneta, G. Lymphoscintigraphy and clinical evidence. The European Journal of Lymphology 2005, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Wattm, H.; Singh-Grewalm, D.; Wargonm, O.; Adamsm, S. Paediatric lymphoedema: A retrospective chart review of 86 cases. J Paediatr Child Health 2017, 53(1), 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oztek, A.; Abandeh, L.; Parisi, M. Lymphoscintigraphy for evaluation of pediatric lymphedema. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2025, 66, 251114. [Google Scholar]

- Campisi, C.; Bellini, C; Campisi, C.; Accogli, S.; Bonioli, E.; et al. Microsurgery for lymphedema: clinical research and long-term results. Microsurgery 2010, 30, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, K.; Izquierdo, R.; Vandevender, D.; Warpeha, R.L.; Fareed, J. Transplantation of lymph node fragments in a rabbit ear lymphedema model: a new method for restoring the lymphatic pathway. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998, 101(1), 134–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, E.C.; Shugg, S.; McEwan, W.M. Lymph node grafting in the treatment of upper limb lymphoedema: a clinical trial. ANZ J Surg. 2015, 85(9), 631–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Sicart, S.; Valdés Olmos, R.A. Using lymphoscintigraphy as a prognostic tool in patients with cancer. Reports in Nuclear Medicine 2016, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kwon, J.; Lee, K.; Choi, J.; et al. Changes in lymphatic function after complex physical therapy for lymphedema. Lymphology 1999, 32, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Quartuccio, N.; Alongi, P.; Guglielmo, P.; Ricapito, R.; et al. 99mTc-labeled colloid SPECT/CT versus planar lymphoscintigraphy for sentinel lymph node detection in patients with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Clinical and translational imaging 2023, 11(6), 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, I.J.; Cheville, A.L.; Scheuermann, J.; Srinivas, S.M.; et al. Use of lymphoscintigraphy in radiation treatment of primary breast cancer in the context of lymphedema risk reduction. Radiother Oncol. 2011, 100(2), 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois, P.; Peters, E.; Van Mieghe, A.; Vrancken, A.; et al. Edemas of the face and lymphoscintigraphic examination. Scientific reports 2021, 11(1), 6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, H.; Singh-Grewal, D.; Wargon, O.; et al. Paediatric lymphoedema: A retrospective chart review of 86 cases. J Paediatr Child Health 2017, 53, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, C.; Villa, G.; Sambuceti, G.; Traggiari, C.; et al. Lymphoscintigraphy patterns in newborns and children with congenital lymphatic dysplasia. Lymphology 2014, 47(1), 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Paudel, P.; Paudel, N.; Timalsina, M. Right lower limb lymphatic aplasia in lymphoscintigraphy: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2025, 19(1), 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, U.; Paganelli, G.; Viale, G.; Galimberti, V.; et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary dissection in breast cancer: results in a large series. Journal of the national Cancer Institute 1999, 91(4), 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanas, R.M. An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Cancer 1977, 39(2), 456–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, D.L.; Wen, D.R.; Wong, J.H.; Economou, J.S.; et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg 1992, 127, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, R.; Zarifmahmoudi, L. Application of lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in surgical oncology. In Clinical nuclear medicine; Springer International Publishing, 2020; pp. 431–458. [Google Scholar]

- AbAziz, A.; Yusop, S.M.; Tahir, M.F.M.; Lim, Y.C; Gallowitsch, H.J. Lymphoscintigraphy SPECT/CT: Instrumental navigator in repair of thoracic duct injury. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016, 50, 173–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendu, D.R.; Sternlich, t H.; Ramanathan, L.V.; Pessin, M.S.; et al. Two cases of spontaneous remission of non-parasitic chyluria. Clin Biochem 2017, 2017 S0009-9120, 30385–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuanm, Z.; Luo, Q.; Chen, L.; Luo, Q.; Zhu, R. The role of radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy in chyluria. Hell J Nucl Med 2010, 13, 238–240. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.; Saitom, N.; Takaki, M.; Furumotom, A.; et al. Refractory chylothorax in HIV/AIDS-related disseminated mycobacterial infection. Thorax 2016, 71(10), 960–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Thng, J.; Ho, D.; Lawrentschuk, N. Clinical practice guide: management of chylous ascites after retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. European Urology Focus 2024, 10(3), 367–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccauro, M.; Villa, G.; Manzara, A.; Follacchio, G.A.; et al. Lymphoscintigraphy for the evaluation of limb lymphatic flow disorders: Report of technical procedural standards from an Italian Nuclear Medicine expert panel. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2019, 38(5), 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giammarile, F.; Bozkurt, M. F.; Cibula, D.; Pahisa, J.; et al. The EANM clinical and technical guidelines for lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel node localization in gynaecological cancers. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2014, 41(7), 1463–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, M.; Ha, S.; Yoo, M. Y.; Chae, S. Y.; Choi, J. Y.; Korean Society of Nuclear Medicine Medical Affairs Committee. Lymphoscintigraphy in Lymphedema: Procedure and Interpretation Guideline by the Korean Society of Nuclear Medicine and Korean Society of Lymphedema. Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Zavaleta, C. Current and developing lymphatic imaging approa hes for elucidation of functional mechanisms and disease progression. Molecular Imaging and Biology 2024, 26(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Burgard, C.; Baumeister, R.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus lymphoscintigraphy for the assessment of focal lymphatic transport disorders of the lower limb: first experiences. Nuklearmedizin 2014, 53(5), 190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanein, A.H.; Maclellan, R.A.; Grant, F.D.; Greene, A.K. Diagnostic accuracy of lymphoscintigraphy for lymphedema and analysis of false-negative tests. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2017, 5(7), e1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloviczki, P.; Calcagno, D.; Schirger, A.; et al. Noninvasive evaluation of the swollen extremity: experiences with 190 lymphoscintigraphic examinations. J Vasc Surg 1989, 9(5), 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihara, M.; Hara, H.; Zhou, H.P.; Tange, S.; Kikuchi, K. Lymphaticovenous anastomosis releases the lower extremity lymphedema-associated pain. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2017, 5(1), e1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almujally, A.; Sulieman, A.; Salah, H.; Alanazi, B.; Calliada, F. Patient Dosimetry in SPECT/CT Lymphoscintigraphy Examinations. J Res Med Dent Sci 2020, 8(5), 97–100. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).