Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

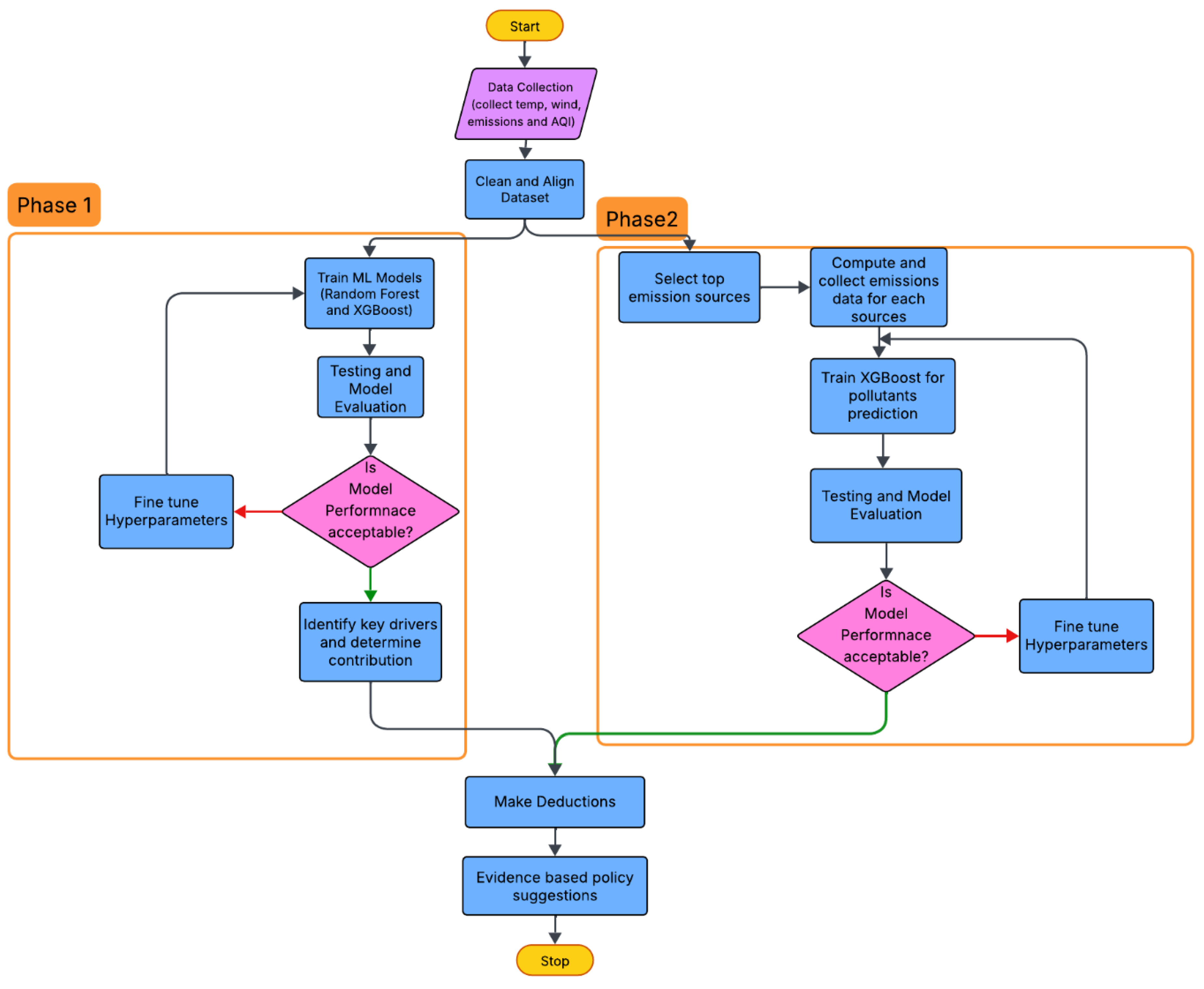

2. Materials and Methods

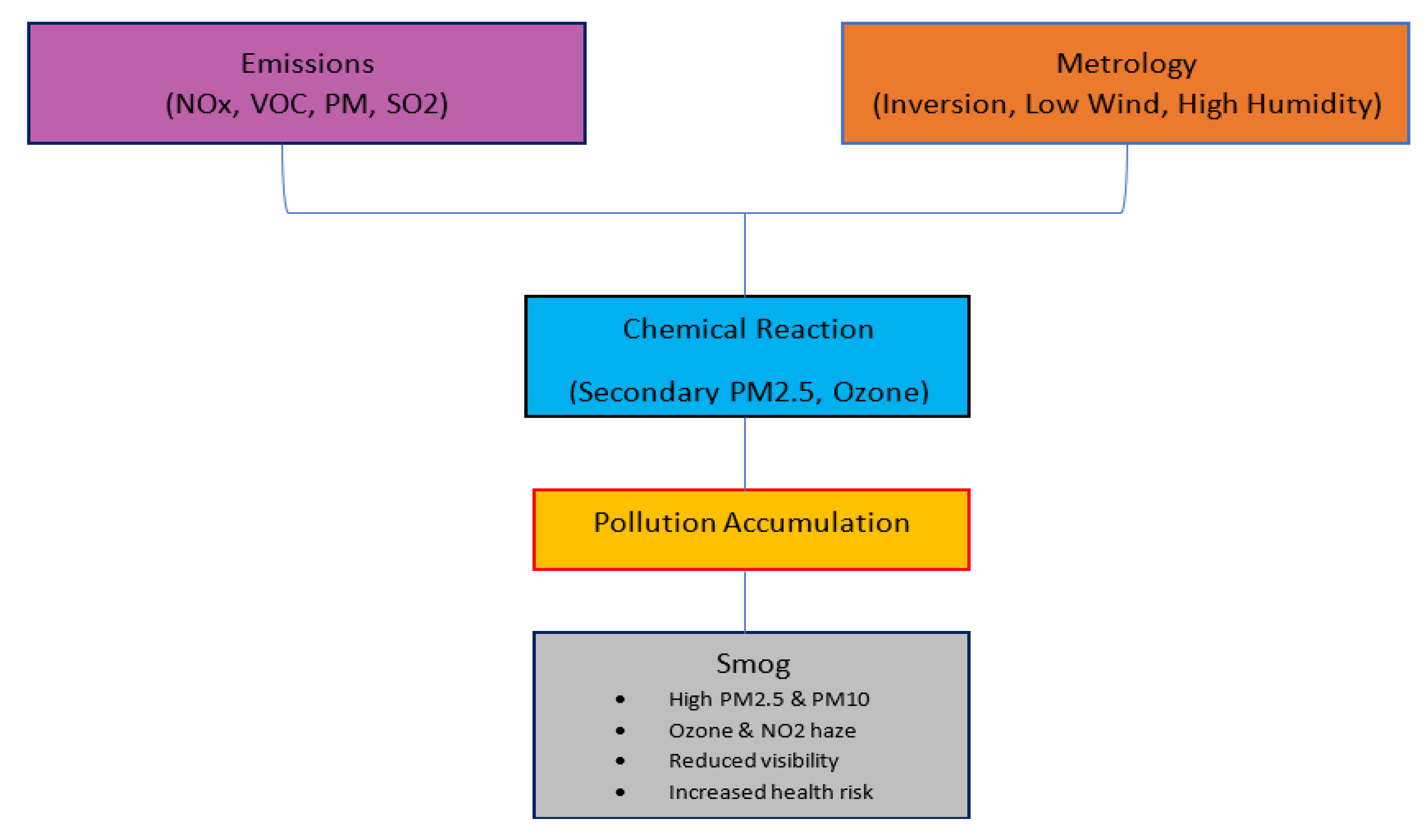

2.1. Composition of Smog

2.2. Role of Temperature Inversion

2.3. Experimental Set-up

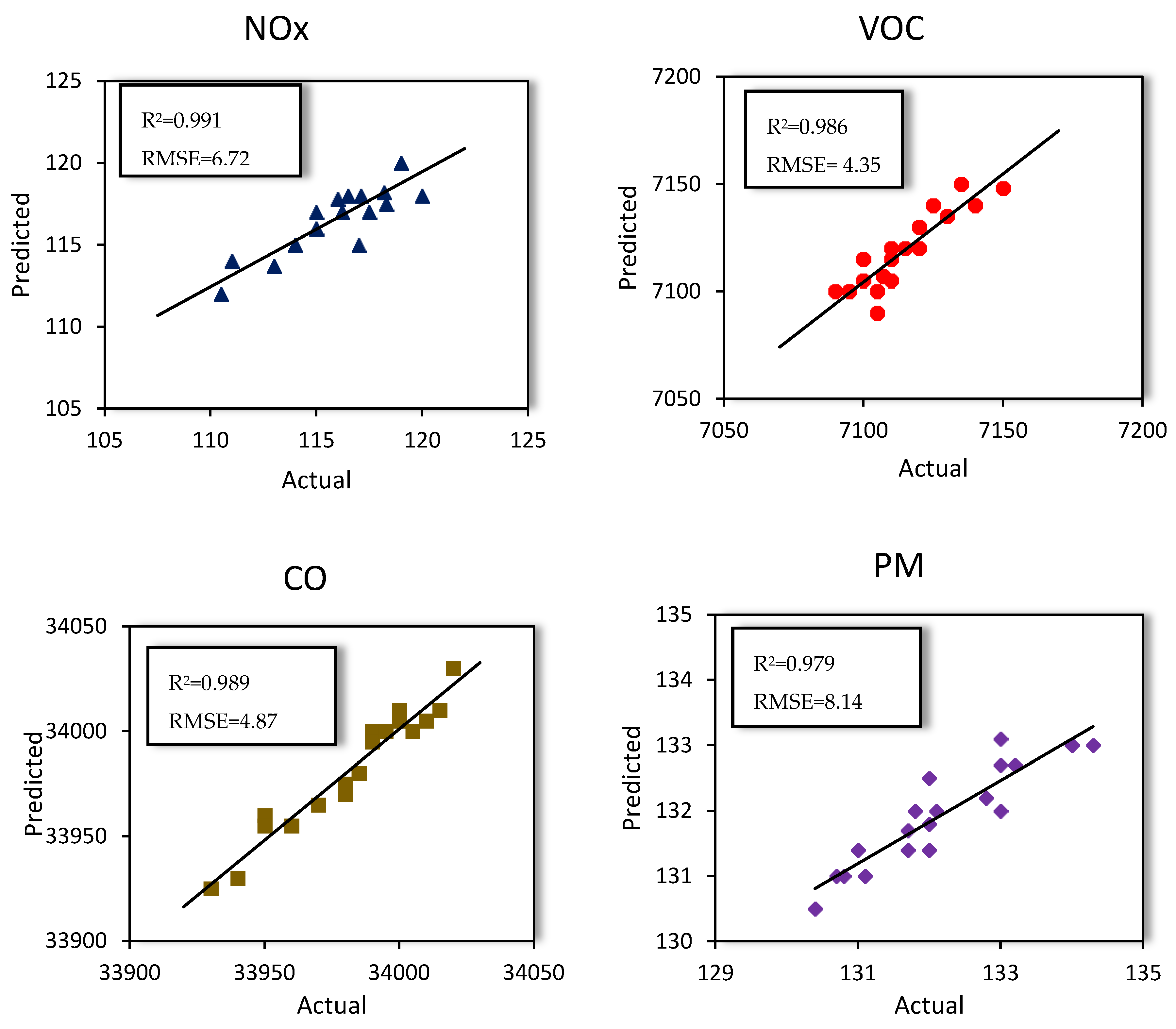

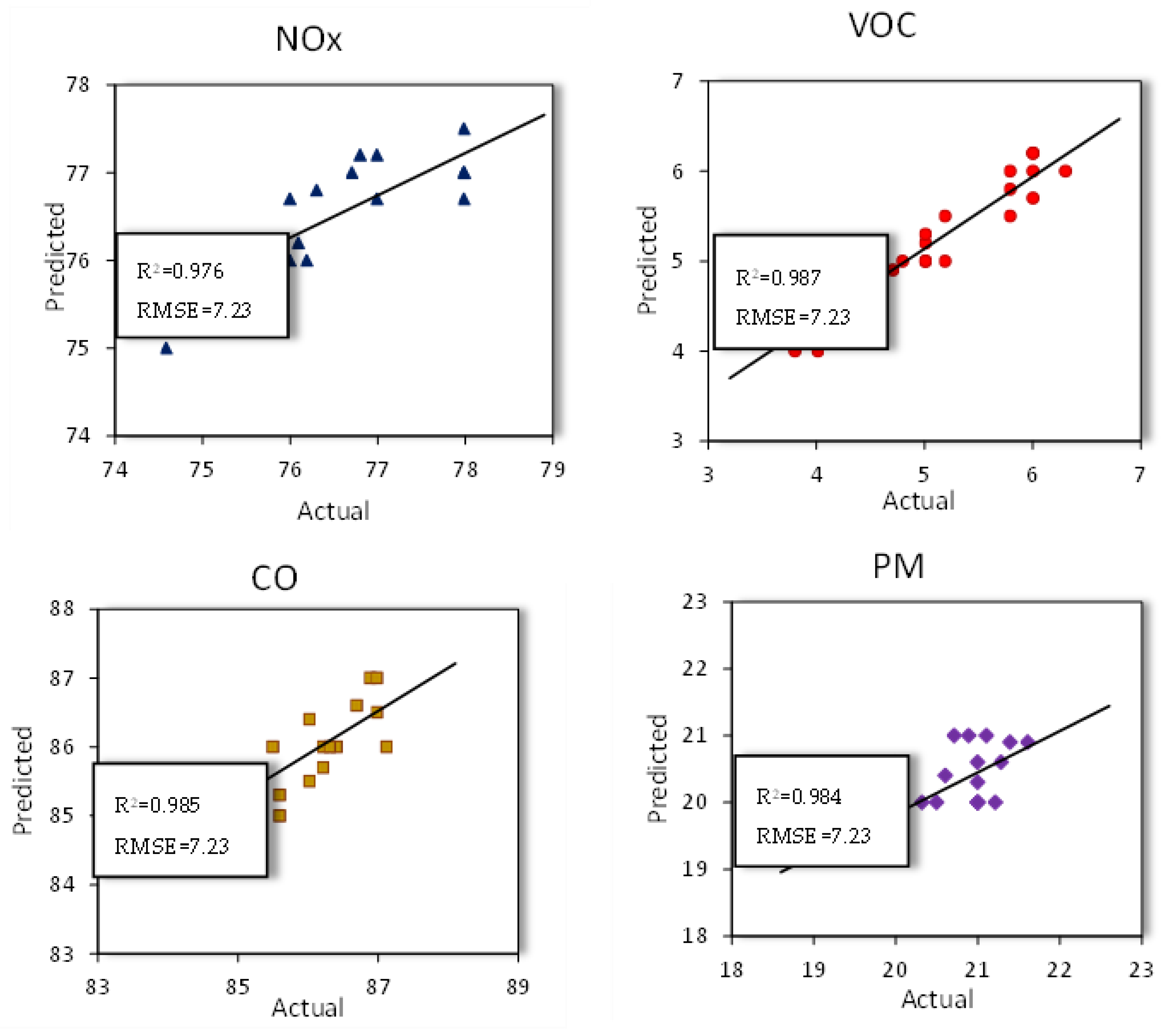

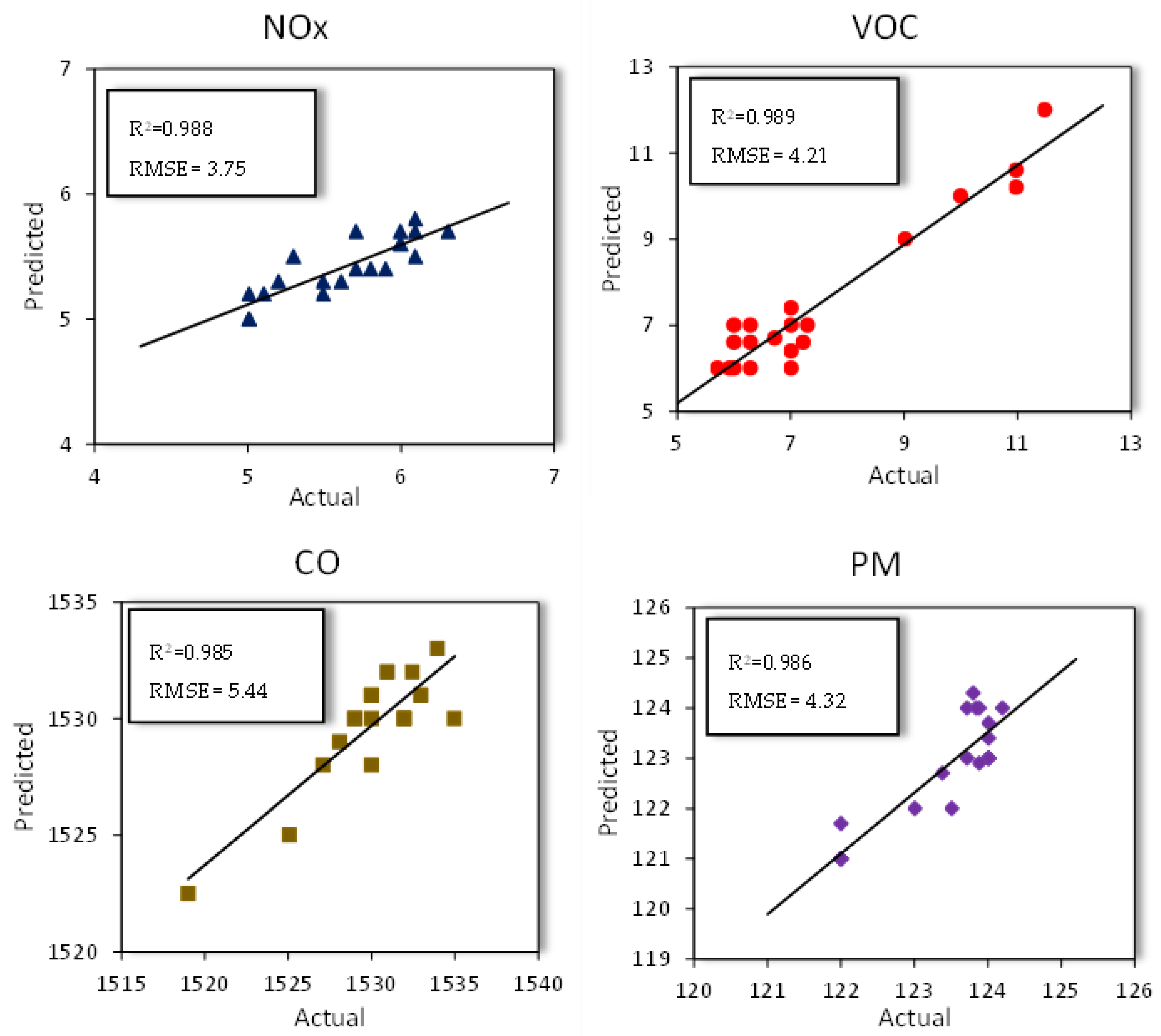

3. Results and Discussion

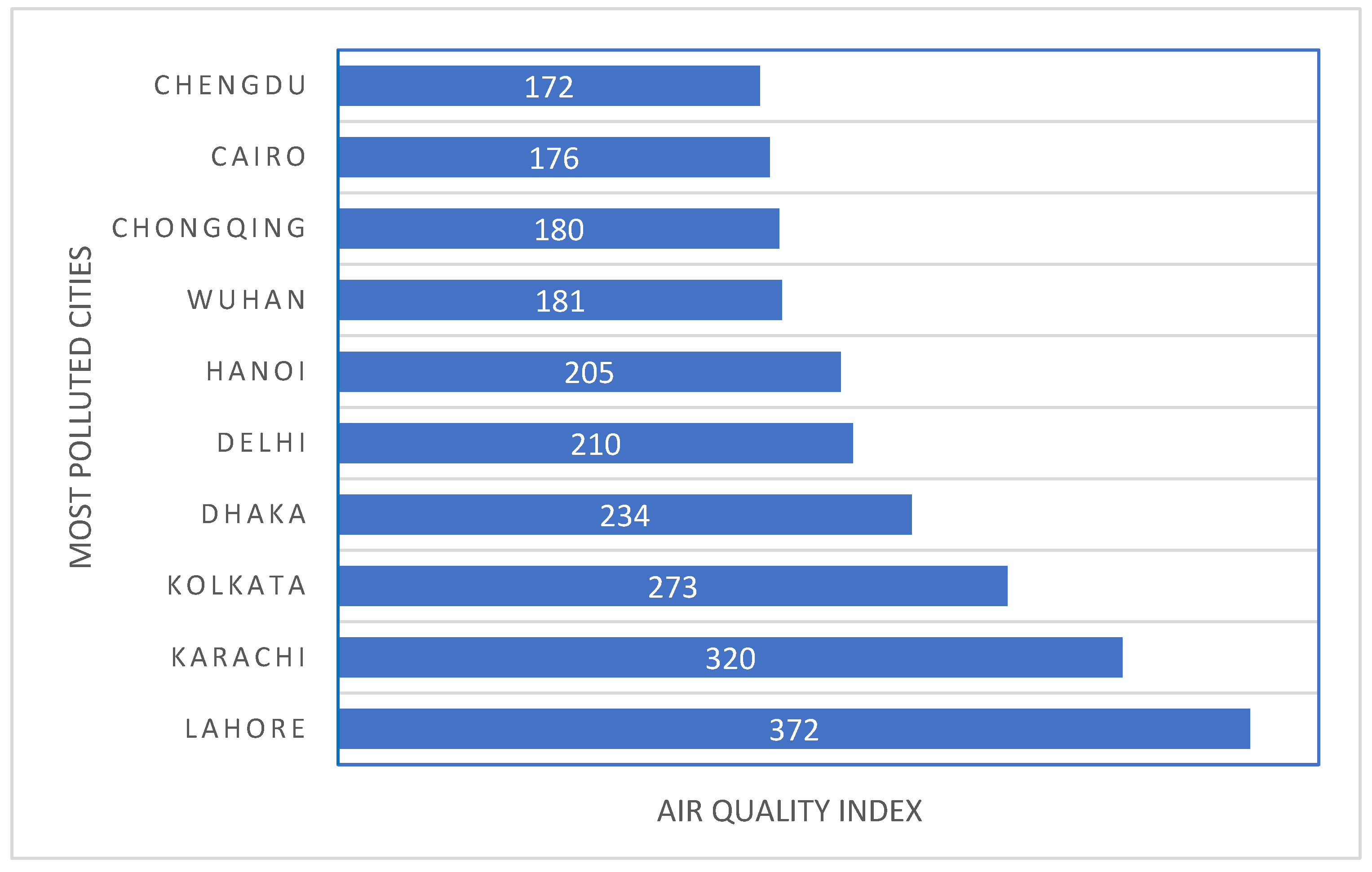

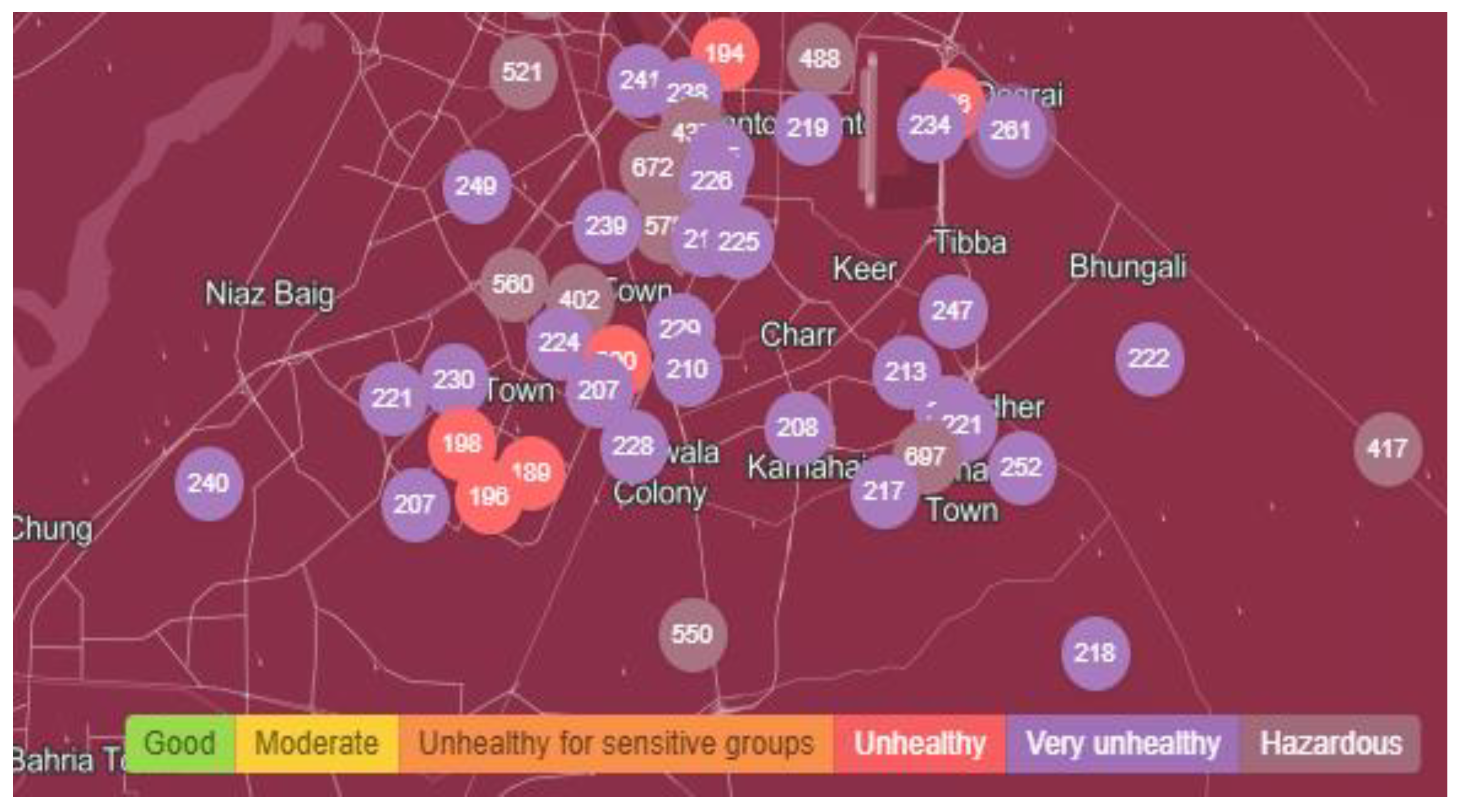

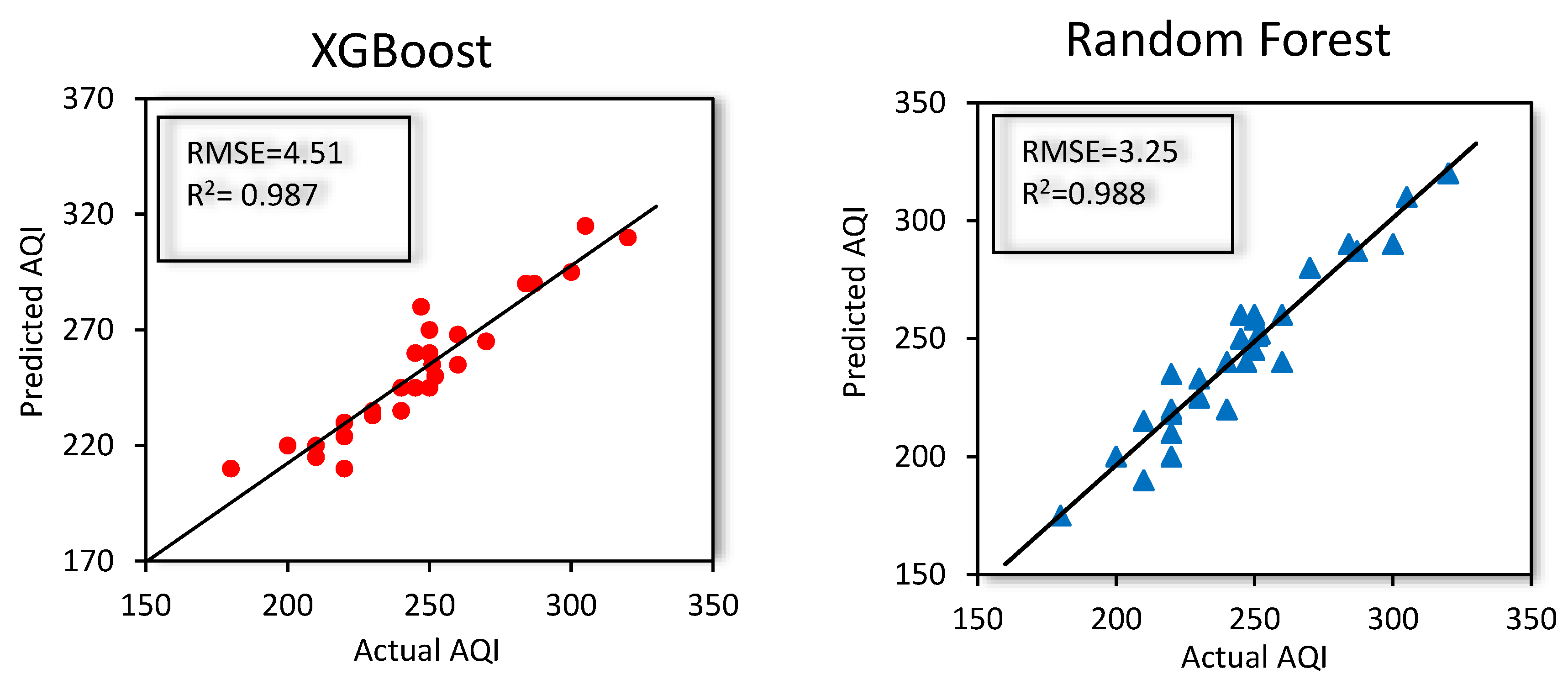

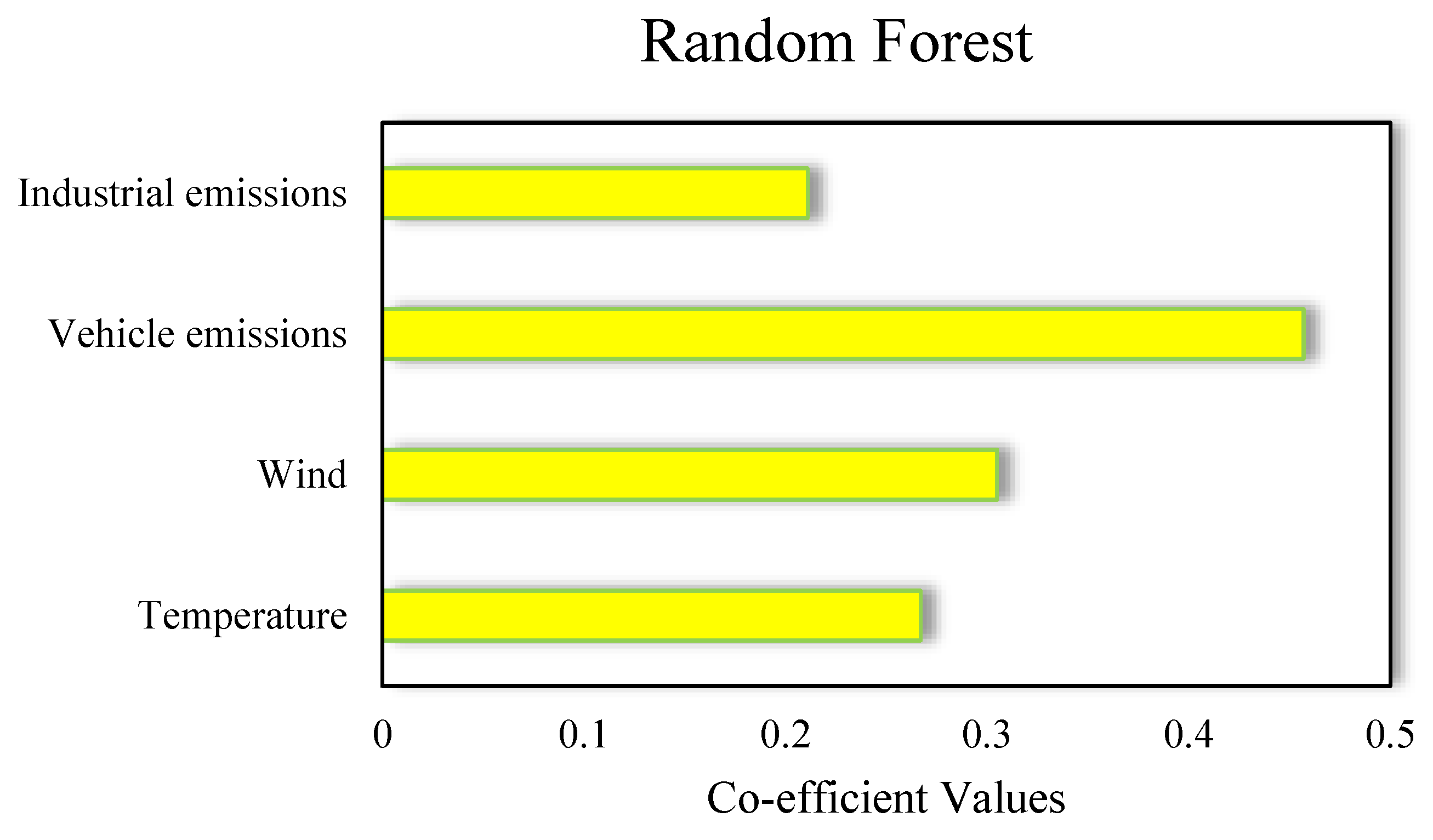

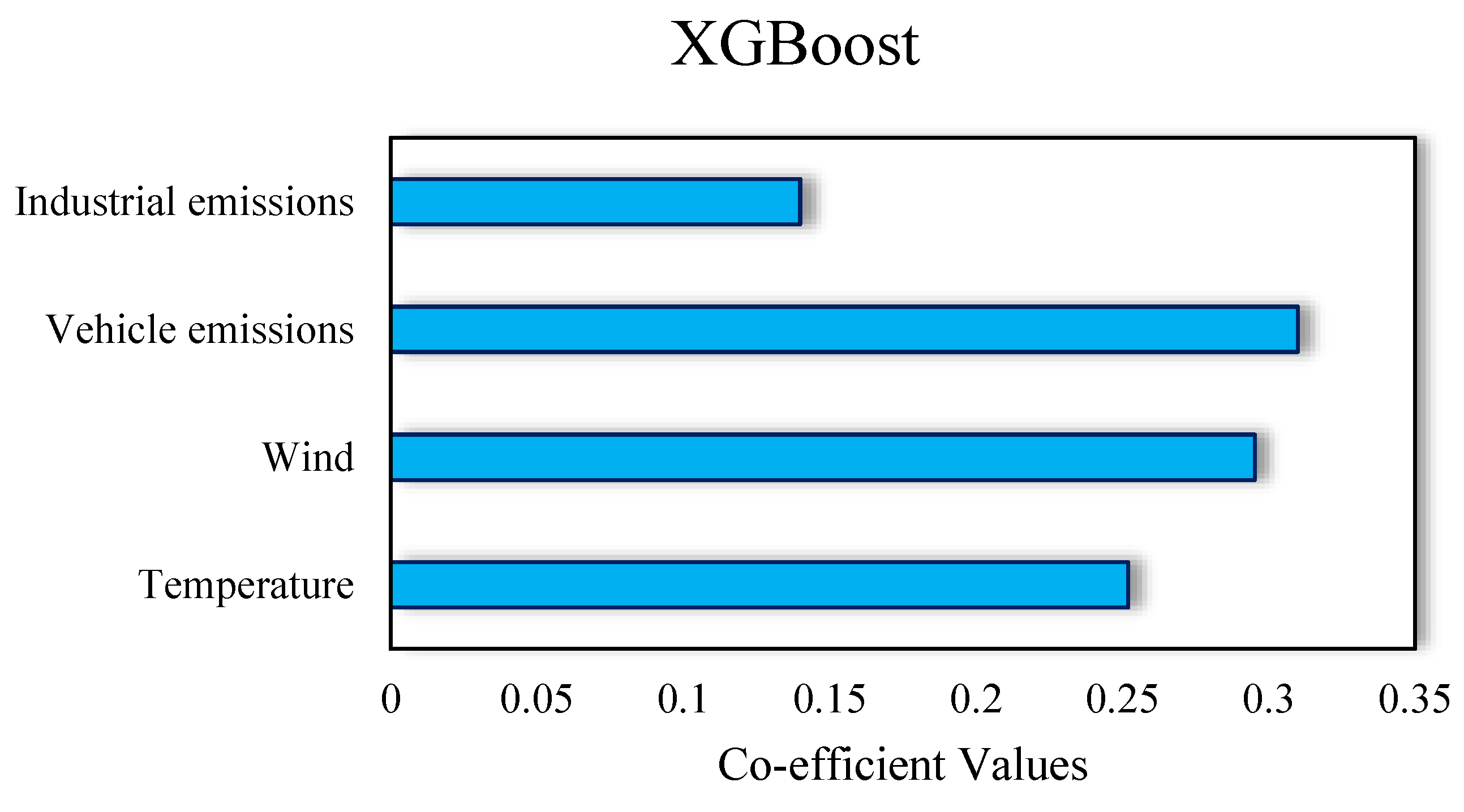

3.1. Influence of Weather and Emissions on AQI

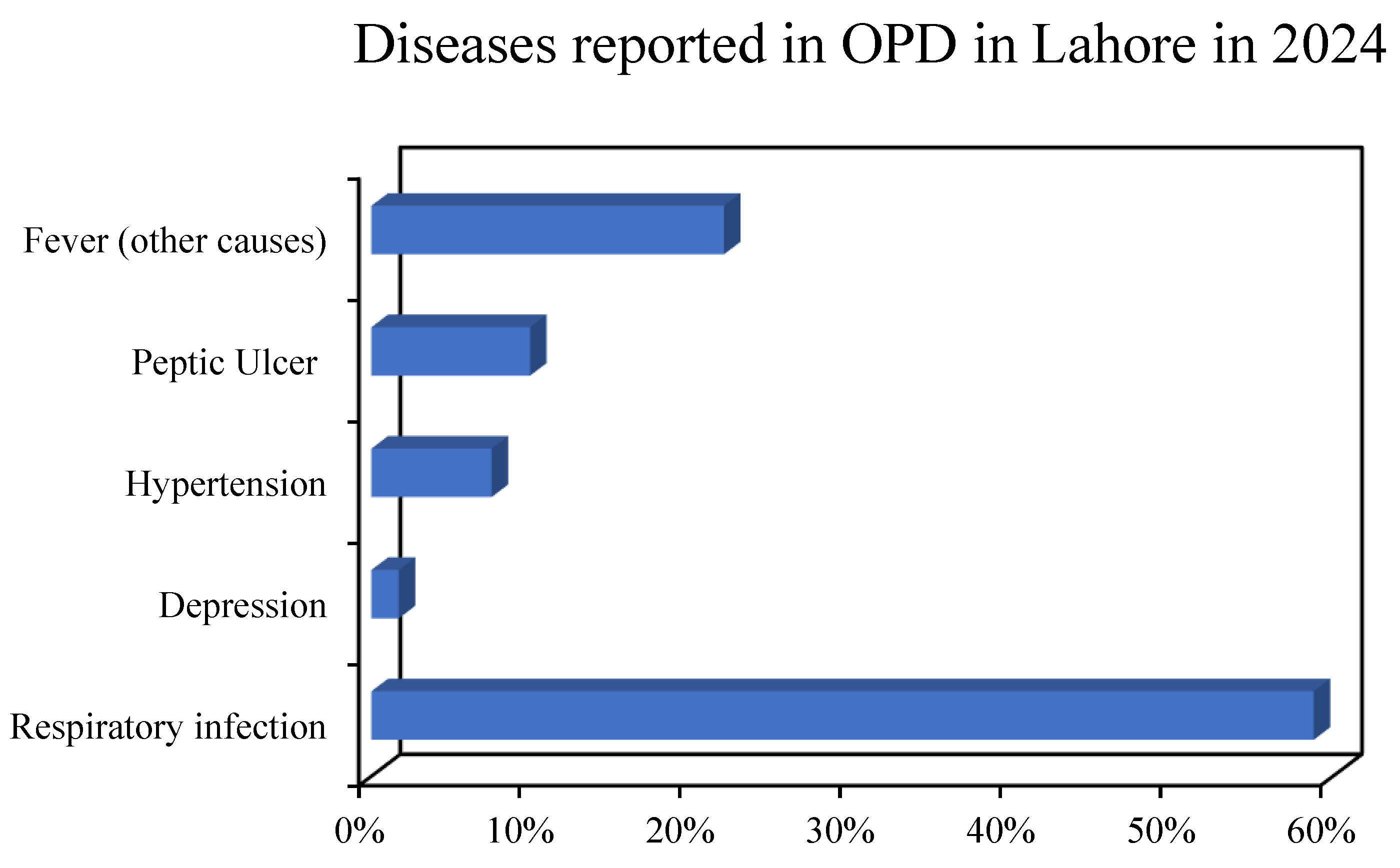

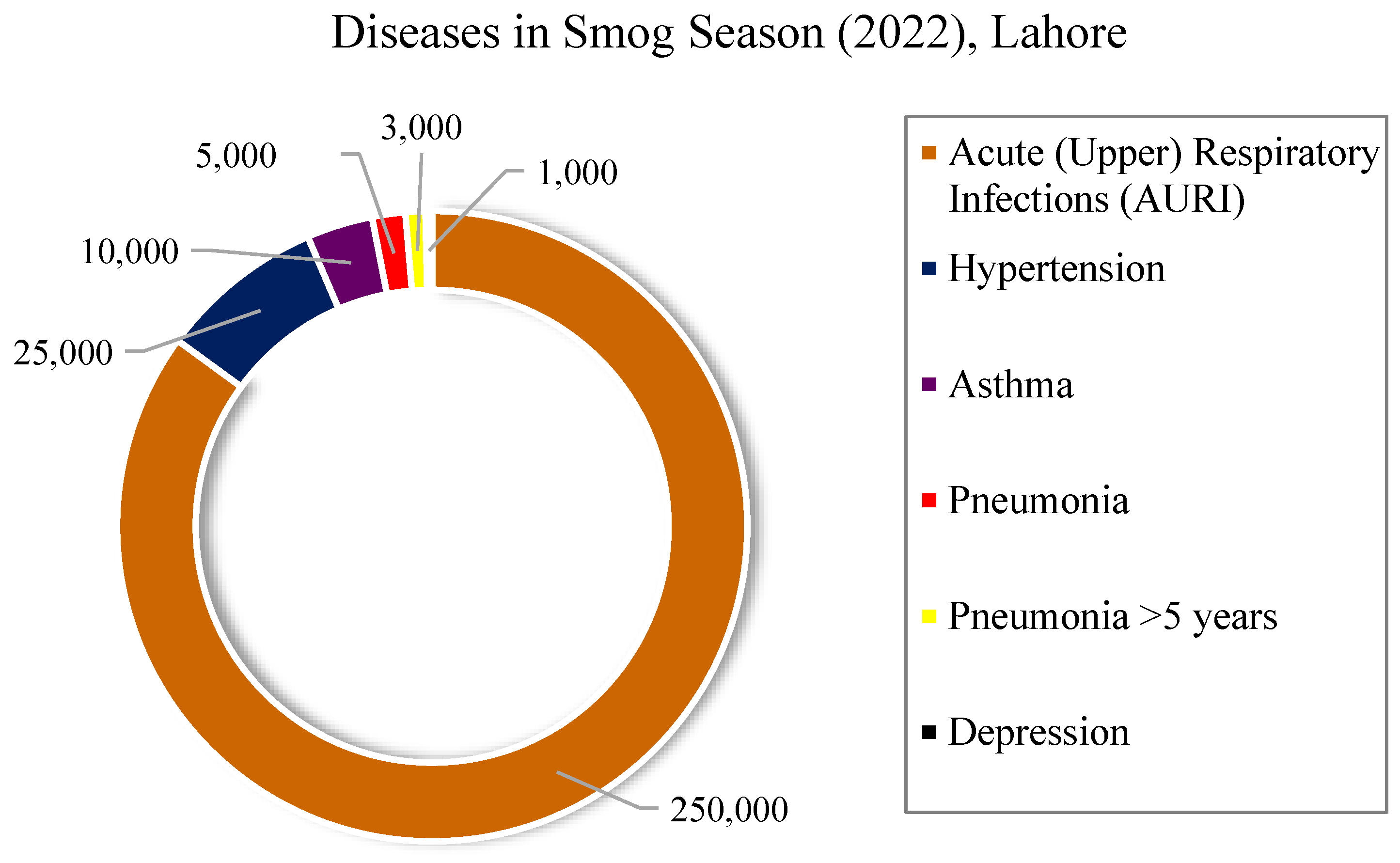

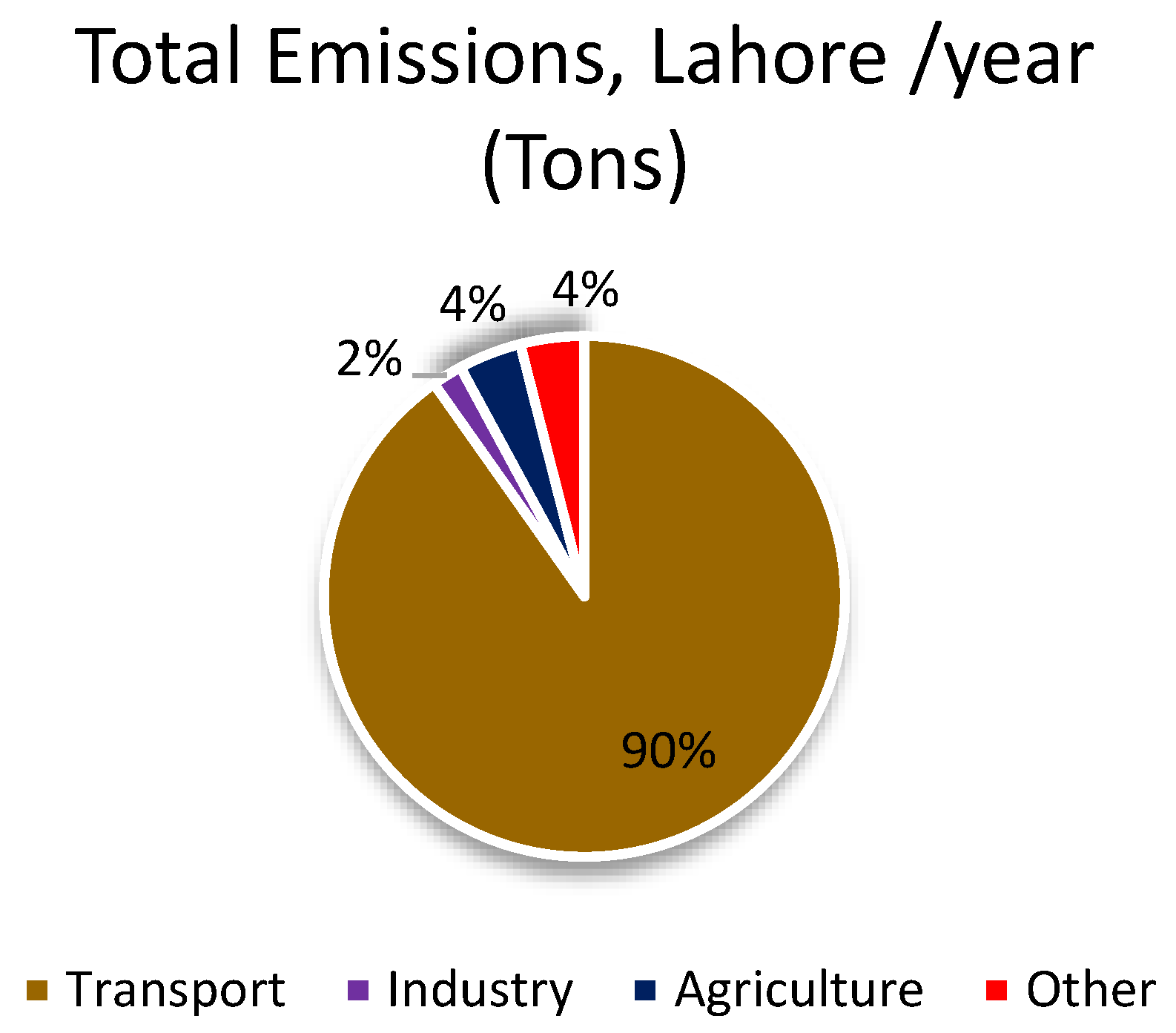

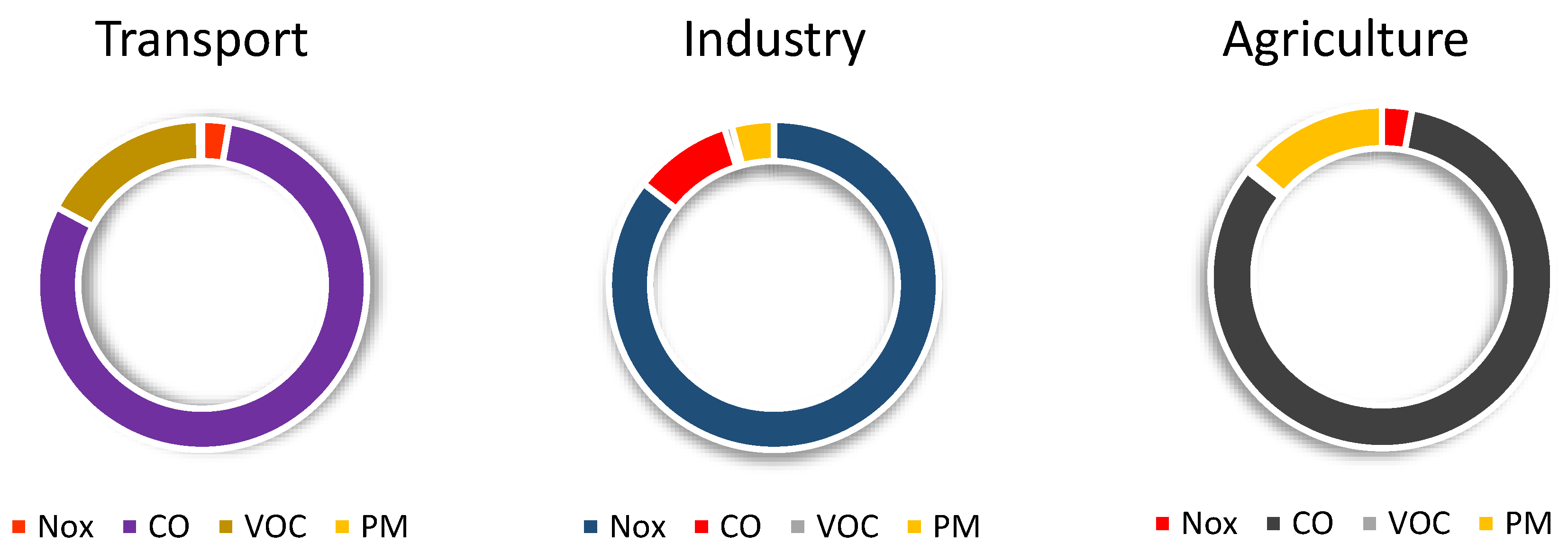

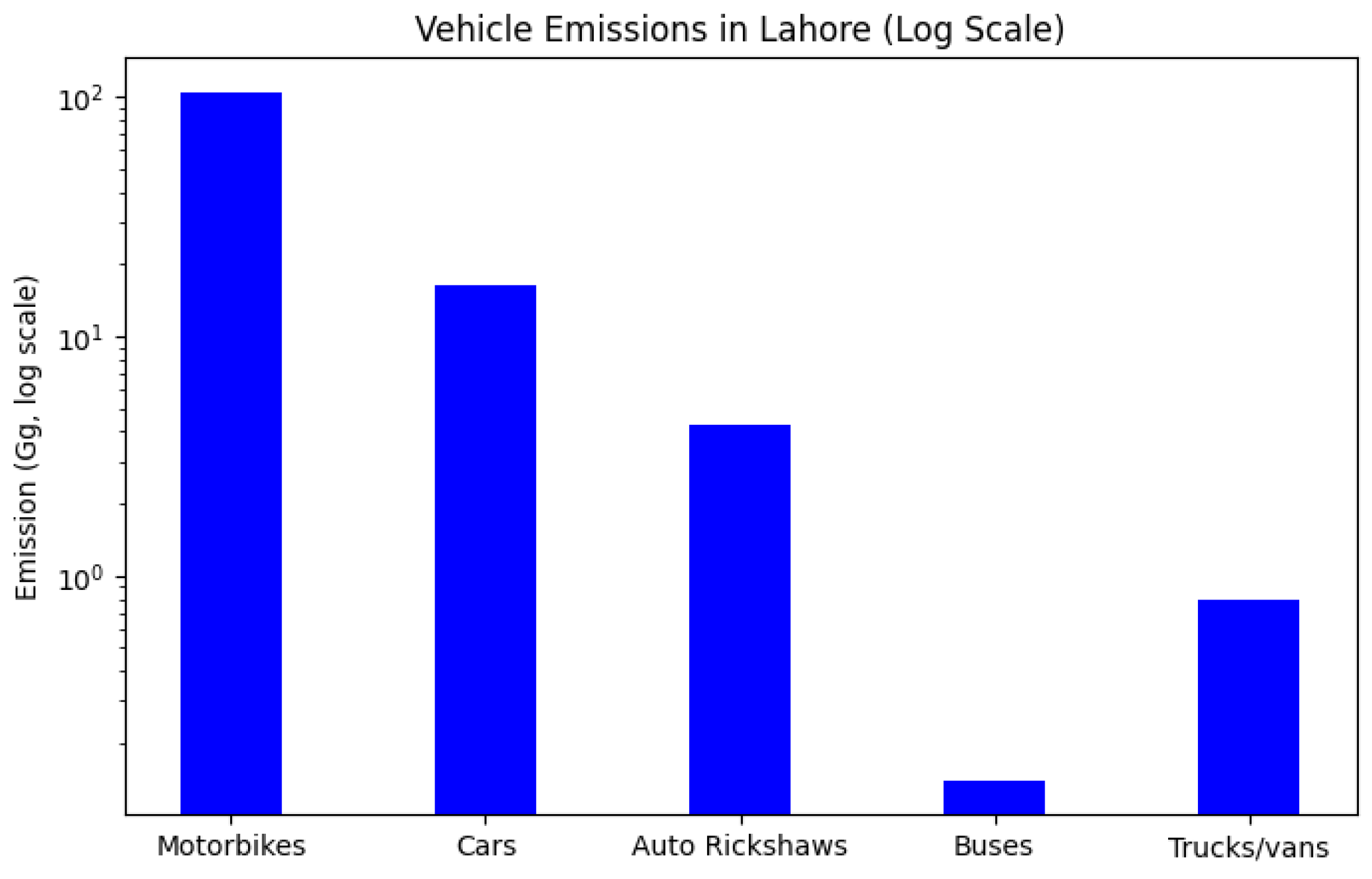

3.2. Effect of Emission Composition

4. Mitigation Strategies and Solutions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AQI | Air Quality Index |

| AR | Additive Regression |

| AURI | Acute Upper Respiratory Infections |

| BRT | Boosted Regression Trees |

| GAM | Generalized Additive Model |

| GBR | Gradient Boosting Regression |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit Network |

| GWO | Grey Wolf Optimizer |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory Network |

| REPT | Reduced Error Pruning Tree, |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RT | Random Tree |

| RSS | Random Subspace |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

References

- World Air Quality Report. 2024.

- Abhranil, B., et al., Assessing AQI of air pollution crisis 2024 in Delhi: its health risks and nationwide impact. Discover Atmosphere, 2025. 3(13). [CrossRef]

- Abdul, R., et al., Smog: Lahore needs global attention to fix it. Environmental Challenges, 2024. 16: p. 100999. [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z., C. Song Xi, and B. Le, Air pollution estimation under air stagnation—A case study of Beijing. Environmetrics, 2023. 34(6): p. e2819. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X., et al., Characterization and sources of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) during 2022 summer ozone pollution control in Shanghai, China. Atmospheric Environment, 2024. 327(15): p. 120464. [CrossRef]

- Amir, G. and G. Davoud, Identifying the Causes of Air Pollution in the Tehran Metropolis-Iran and Policy Recommendations for Sustainability. Aerosol Science and Engineering, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rabia, M., et al., Solving the mysteries of Lahore smog: the fifth season in the country. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 2024. 5: p. 1314426. [CrossRef]

- Prakash Chand, K., Air Pollution in Delhi: Causes and Consequences, in Combating Air Pollution 2024, Springer, Cham. p. 61-75.

- Kinjal, B. and S. Vishal. Sustainable Solutions for Delhi’s Air Pollution: A Data Driven Approach. in 1st International Conference on Advanced Materials for Sustainable Innovation. 2025. New Delhi, India: Springer, Singapore.

- Ashima, S. and M. Renu, Rising Extreme Event of Smog in Northern India: Problems and Challenges, in Extremes in Atmospheric Processes and Phenomenon: Assessment, Impacts and Mitigation 2022, Springer, Singapore. p. 205-236.

- Muhammad, N.-u.-M., Z. Masooma, and J. Muhammad, Exploring mitigation strategies for smog crisis in Lahore: a review for environmental health, and policy implications. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2024. 196: p. 1296.

- Shazia, I., et al., Impact of Air Pollution and Smog on Human Health in Pakistan: A Systematic Review. Environments, 2025. 12(2): p. 46. [CrossRef]

- Aiman, F. and B. Derk, Assessment of Brick Kilns’ contribution to the air pollution of Lahore using air quality dispersion modeling. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2025. 197: p. 318. [CrossRef]

- Uzma, N. and I. Muhammad, Smog diplomacy: Strengthening Pakistan-India cooperation for transboundary air pollution. Journal of Climate and Community Development, 2025. 4(1): p. 55-65.

- Muhammad, Z., Spatiotemporal analysis of tropospheric nitrogen dioxide hotspot over Lahore Division in Pakistan. Discover Environment 2025. 3: p. 113.

- IQAir. Live most polluted major city ranking. 2025; Available from: https://www.iqair.com/us/world-air-quality-ranking.

- Agency, E.P. and P. Government of Punjab. AQI Punjab. 2025; Available from: https://aqi.punjab.gov.pk/.

- System, D.H.I. Disease Wise Analytics. 2024 [cited November, 2024; Available from: https://dhispb.com/.

- Rachna, A., et al., Assessing Respiratory Morbidity Through Pollution Status and Meteorological Conditions for Delhi. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2006. 114: p. 489-504. [CrossRef]

- Mario J., M. and M. Luisa T., Megacities and Atmospheric Pollution. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2004. 54: p. 644-680.

- The Urban Unit Government Office, P. The Urban Unit. 2022 [cited November, 2024; Available from: https://urbanunit.gov.pk/.

- Siddiqui, S.A., F. Neda, and A. Anwar, Smart air pollution monitoring system with smog prediction model using machine learning. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2021. 12(8): p. 401-409.

- Pervaiz, Z., et al., Predictive Analysis of Smog Exposure and Its Impact on Human Health Outcomes. Journal of Computing & Biomedical Informatics, 2025. 9(2).

- Muhammad Fahad, M., et al., Predicting Air Quality in Pakistan with a Focus on Smog Formation: A Machine Learning Approach, in International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET). 2024, IEEE: Dubai, UAE.

- Sandhya, S. and S. Arun, Machine learning approach to PM2.5 forecasting and health risk assessment during stubble burning period in Delhi. Aerosol Science and Technology, 2025. 59(11): p. 1385-1404. [CrossRef]

- R, A. and B. M, Stubble Burning and Its Impact in Delhi’s Air Pollution of india: Predictive Approach Using Machine Learning Applied Ecology & Environmental Research, 2025. 23(4).

- Zhiyuan, L., Y. Steve Hung-Lam, and H. Kin-Fai, High temporal resolution prediction of street-level PM2.5 and NOx concentrations using machine learning approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020. 268: p. 121975.

- Thomas M. T., L., et al., Evaluation of Machine Learning Models in Air Pollution Prediction for a Case Study of Macau as an Effort to Comply with UN Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, 2024. 16(17): p. 7477.

- Yanchuan, S., et al., Estimation of daily NO2 with explainable machine learning model in China, 2007–2020. Atmospheric Environment, 2023. 314: p. 120111. [CrossRef]

- Komal, Z., S. Sana, and T. Salman, Prediction of aerosol optical depth over Pakistan using novel hybrid machine learning model. Acta Geophysica, 2023. 71: p. 2009-2029.

- Abu Reza Md. Towfiqul, I., et al., Estimating ground-level PM2.5 using subset regression model and machine learning algorithms in Asian megacity, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health 2023. 16: p. 1117-1139.

- Alibek, I., R. Nurtugan, and A. Aizhan, Predicting particulate matter (PM2.5) air pollution levels in Almaty city using machine learning techniques. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 2025. 11: p. 236.

- Gokulan, R., et al., Air quality prediction by machine learning models: A predictive study on the indian coastal city of Visakhapatnam. Chemosphere, 2023. 338: p. 139518. [CrossRef]

- AccuWeather, Lahore, Pakistan. 2025 [cited 2025; Available from: https://www.accuweather.com/en/pk/lahore/260622/weather-forecast/260622.

- Punjab Development Statistics. 2021 [cited November, 2024; Available from: https://bos.punjab.gov.pk/sites/bos.punjab.gov.pk/files/PDS%202021.pdf.

- Sevtap, T., Machine learning-based forecasting of air quality index under long-term environmental patterns: A comparative approach with XGBoost, LightGBM, and SVM. PLoS One, 2025. 20(10): p. e0334252.

- Rudy, W., P. Mauridhi Hery, and A. Wiwik. Enhancing Predictive Emissions Monitoring Performance: Data Preprocessing for XGBoost-Based Model Algorithm. in 17th International Conference on Knowledge and Smart Technology. 2025. Bangkok, Thailand: IEEE.

- Stefan, W., et al., Hourly Particulate Matter (PM10) Concentration Forecast in Germany Using Extreme Gradient Boosting. Atmosphere 2024. 15(5): p. 252. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Location | Scope | ML Model used | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | Delhi, India | Air quality monitoring using temp, humidity , wind for PM only | RF and Adaboost Models | Accuracy for Adaboost reaches 98.24% which is highest among all the models |

| [23] |

Lahore, Pakistan | Analyze pollutants to determine main cause for respiratory diseases | RF, XGBoost, Logistic Regression Models | The models had been identified to be very accurate, F1-score, and ROC-AUC measures. PM 2.5 and PM 1.0 found to be main cause of respiratory and other health problems |

| [24] | Punjab, Pakistan | Predictive model to forecast PM 2.5 and PM10 | ANN Model | Model’s high accuracy (> 90%) in predicting air quality indices and identifying critical thresholds for smog |

| [25] | Delhi, India | Predictive model for PM 2.5 forecast | RF, ANN, SVM Models | RF gave the best results for both training and testing. Testing accuracy (R2 = 0.842, RMSE = 0.06, and MAE = 0.045) |

| [26] | Delhi, India | Predictive method to examine and measure how stubble burning affects air pollution | Gradient Boosting Regression Model | AQI change per 1% fire count increase varies between 0.08% and 0.38%, showing a consistent but varying impact. |

| [27] | Hong Kong | Develop machine learning-based models for predicting hourly street-level PM2.5 and NOx concentrations | RF, BRT, SVM, XGBoost, GAM, and Cubist Models | RF outperformed other MLAs with ten-fold cross validation (CV) R2 values higher than 0.81 and 0.62 for PM2.5 and NOx predictions, respectively. |

| [28] | Macau | Develop a dependable air pollution prediction model for Macau | RF, SVR, ANN, RNN, LSTM, GRU Models | The RF model best predicted PM10, PM2.5, NO2, and CO concentrations with the highest PCC and KTC in a daily air pollution prediction |

| [29] | Eastern China | Predictive model for daily NO2 concentrations | XGBoost Model | R2 of 0.75 and root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 9.11 μg/m3 |

| [30] | Lahore, Pakistan | Predictive model for Aerosol optical depth (AOD) used to estimate the extent of air pollution | SVR and SVR-GWO Models | SVR-GWO model (RMSE = 0.07, MAE = 0.06, R2=0.6) performed better than others |

| [31] | Dhaka, Bangladesh | Prediction model for the ground-level PM2.5 concentrations | RT, AR, REPT, RSS Models | The RSS model is the most suitable model for PM2.5 prediction, as shown by the lower MAE and RMSE values and a higher R2 value |

| [32] | Almaty, Kazakhstan | Prediction model for the ground-level PM2.5 concentrations | RNN, LSTM Models | LSTM is better at forecasting for 90 days (MAE = 2.0,MAPE = 11.57, RMSE = 2.18) |

| [33] | Visakhapatnam, India, | Prediction model for AQI | RF, Catboost, Adaboost, and XGBoost Models | Catboost and RF models performed best, howing maximum correlations of 0.9998 and 0.9936 |

| Pollutant | Primary Sources | Contribution to Smog |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) | - Vehicle exhaust (cars, trucks, buses) - Power plants and thermal electricity generation - Industrial combustion processes |

NOx reacts with volatile organic compounds (VOCs) under sunlight to form ozone and secondary PM. Major contributor to photochemical smog. |

| Particulate Matter (PM2.5, PM10) | - Vehicle exhaust (especially diesel) - Industrial emissions (cement, brick kilns, steel) - Construction dust and road dust - Biomass burning (wood, crop residue) |

Causes haze, reduced visibility, and respiratory diseases. PM2.5 penetrates deep into the lungs. |

| Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) | - Fuel evaporation and incomplete combustion from vehicles - Industrial solvents and chemical processes - Biomass burning |

VOCs react with NOx in sunlight to produce ozone and secondary organic aerosols, contributing to photochemical smog. |

| Sulfur Oxides (SO₂, SOₓ) |

- Coal and oil combustion in power plants - Industrial furnaces - Refineries |

Reacts in the atmosphere to form sulphate aerosols, contributing to acid smog and haze. |

| Ozone (O₃) | - Secondary pollutant formed by NOx + VOCs under sunlight | Not emitted directly, forms in the troposphere during photochemical reactions. High ozone concentrations irritate eyes, lungs, and worsen respiratory diseases. |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | - Incomplete combustion from vehicles, industries, and biomass burning | Reduces oxygen delivery in the body; indirectly contributes to photochemical smog formation. |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | - Fossil fuel combustion - Industrial processes |

Weak direct contribution to smog, but important greenhouse gas; acts as a tracer for emissions. |

| Model | Key Hyperparameters / Architecture | Values / Settings |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest Regressor | Number of Trees (n_estimators) | 100 |

| Minimum Samples per Leaf (min_samples_leaf) | 1 | |

| Splitting Criterion | Mean Squared Error | |

| Random Seed | 42 | |

| XGBoost Regressor | Number of Trees (n_estimators) | 100 |

| Learning Rate (eta) | 0.1 | |

| Maximum Depth (max_depth) | 3 | |

| Subsample Fraction (subsample) | 1 | |

| Random Seed | 42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).