Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

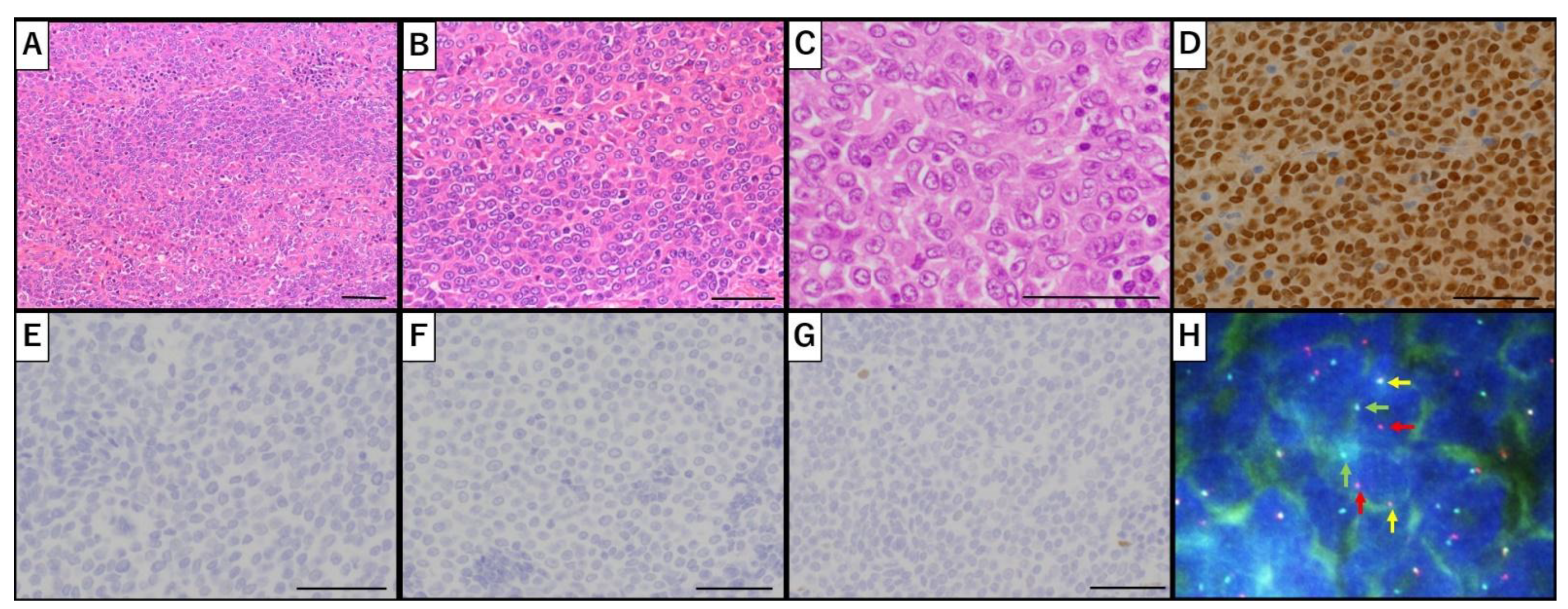

Nuclear protein in testis (NUT) carcinoma is a rare, aggressive, and poorly differentiated epithelial malignancy characterized by the rearrangement of NUTM1 (NUT middle carcinoma family member 1) on 15q14. It primarily originates along the midline structures, including the head, neck, thorax, and mediastinum. Although NUT carcinoma of the pelvic gynecological organs is exceedingly rare, reported cases have been limited to primary or metastatic ovarian tumors. Here, we present the first documented case of primary uterine NUT carcinoma. A 53-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with abnormal uterine bleeding and a uterine mass. She underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The initial postoperative histopathological evaluation suggested undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma; however, subsequent immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed NUTM1 rearrangement, confirming the diagnosis of NUT carcinoma. The patient experienced tumor recurrence six months postoperatively and succumbed to the disease nine months later. The pathological diagnosis was challenging; the presence of abrupt squamous differentiation prompted further IHC analysis, leading to the definitive diagnosis. Primary uterine NUT carcinoma may be misdiagnosed as other undifferentiated uterine tumors due to its rarity and histological overlap. Given the diagnostic challenges, NUT IHC staining and molecular testing for NUTM1 rearrangement should be considered in undifferentiated uterine tumors with ambiguous histopathological features.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NUT | Nuclear protein in testis |

| NUTM1 | NUT midline carcinoma family member 1 |

| IHC | Immunohistochemical |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| DWI | Diffusion-weighted imaging |

| FISH | Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| FDG-PET | Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography |

References

- French, C.A. Pathogenesis of NUT midline carcinoma. Annu Rev Pathol 2012, 7, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubonishi, I.; Takehara, N.; Iwata, J.; Sonobe, H.; Ohtsuki, Y.; Abe, T.; Miyoshi, I.; Novel, T. Novel t(15;19)(q15;p13) chromosome abnormality in a thymic carcinoma. Cancer Res 1991, 51, 3327–3328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- French, C. NUT midline carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.; Kim, S.I.; Kim, J.W.; Jeon, Y.K.; Lee, C. NUT carcinoma in the pelvic cavity with unusual pathologic features. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2022, 41, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, V.; Saluja, K.; Pina-Oviedo, S. NUT Carcinoma: clinicopathologic features, Molecular Genetics and epigenetics. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 860830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, D.E.; Mitchell, C.M.; Strait, K.M.; Lathan, C.S.; Stelow, E.B.; Lüer, S.C.; Muhammed, S.; Evans, A.G.; Sholl, L.M.; Rosai, J.; et al. Clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of NUT midline carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2012, 18, 5773–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, C.; Hou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, J.; Li, H. Case report: NUT carcinoma with MXI1::NUTM1 fusion characterized by abdominopelvic lesions and ovarian masses in a middle-aged female. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 1091877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, T.M.; Morlote, D.; Xiu, J.; Swensen, J.; Brandwein-Weber, M.; Miettinen, M.M.; Gatalica, Z.; Bridge, J.A. NUTM1-rearranged neoplasia: a multi-institution experience yields novel fusion partners and expands the histologic spectrum. Mod Pathol 2019, 32, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, A.; Bromley, A.; Glaze, S.; French, C.A.; Ghatage, P.; Köbel, M. A rare case of NUT midline carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep 2012, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashino, M.; Kinoshita, I.; Kurisu, Y.; Kawata, R. Supraglottic NUT carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol 2022, 15, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragoescu, E.; French, C.; Cassano, A.; Baker, S.., Jr.; Chafe, W. NUT midline carcinoma presenting with bilateral ovarian metastases: a case report. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2015, 34, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantuejoul, S.; Pissaloux, D.; Ferretti, G.R.; McLeer, A. NUT carcinoma of the lung. Semin Diagn Pathol 2021, 38, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, N.G.; Ma, C.; Danga, K.; Al-Sayegh, H.; Nardi, V.; Barrette, R.; Lathan, C.S.; DuBois, S.G.; Haddad, R.I.; Shapiro, G.I.; et al. An anatomical site and genetic-based prognostic model for patients with nuclear protein in testis (NUT) midline carcinoma: analysis of 124 patients. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2020, 4, pkz094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, C.A.; Ramirez, C.L.; Kolmakova, J.; Hickman, T.T.; Cameron, M.J.; Thyne, M.E.; Kutok, J.L.; Toretsky, J.A.; Tadavarthy, A.K.; Kees, U.R.; et al. BRD-NUT oncoproteins: a family of closely related nuclear proteins that block epithelial differentiation and maintain the growth of carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2008, 27, 2237–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, C.A.; Rahman, S.; Walsh, E.M.; Kühnle, S.; Grayson, A.R.; Lemieux, M.E.; Grunfeld, N.; Rubin, B.P.; Antonescu, C.R.; Zhang, S.; et al. NSD3-NUT fusion oncoprotein in NUT midline carcinoma: implications for a novel oncogenic mechanism. Cancer Discov 2014, 4, 928–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agaimy, A.; Haller, F.; Renner, A.; Niedermeyer, J.; Hartmann, A.; French, C.A. Misleading germ cell phenotype in pulmonary NUT carcinoma harboring the ZNF532-NUTM1 fusion. Am J Surg Pathol 2022, 46, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiota, H.; Elya, J.E.; Alekseyenko, A.A.; Chou, P.M.; Gorman, S.A.; Barbash, O.; Becht, K.; Danga, K.; Kuroda, M.I.; Nardi, V.; et al. ‘Z4’ complex member fusions in NUT carcinoma: implications for a novel oncogenic mechanism. Mol Cancer Res 2018, 16, 1826–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, S.; Perrin, V.; Guillemot, D.; Reynaud, S.; Coindre, J.M.; Karanian, M.; Guinebretière, J.M.; Freneaux, P.; Le Loarer, F.; Bouvet, M.; et al. Transcriptomic definition of molecular subgroups of small round cell sarcomas. J Pathol 2018, 245, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wang, L. CIC. CIC::NUTM1 sarcoma misdiagnosed as NUT carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Oral Oncol 2024, 156, 106787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Proteins | Results | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| NUT | Positive (diffuse) | Strong diffuse positivity is diagnostic for NUT carcinoma. |

| AE1/AE3 | Negative | Positivity indicates the epithelial origin of the tumor. |

| p40 | Negative | Specific marker for squamous cell carcinoma. |

| p63 | Positive (rare) | Marker of squamous and myoepithelial differentiation. |

| β-catenin | Negative | Nuclear positivity is observed in Wnt pathway-activated tumors, such as desmoid-type fibromatosis or solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm. |

| cyclin D1 | Positive | Overexpression is associated with cell cycle progression, as observed in various malignancies, including sarcomas. |

| ER | Positive | Estrogen receptor positivity suggests hormone responsiveness, as usually observed in gynecologic tumors. |

| PgR | Positive | Progesterone receptor positivity; usually co-expressed with ER and supports hormone sensitivity. |

| WT-1 | Positive (focal) | WT-1 is expressed in ovarian serous tumors and some mesothelial and stromal tumors. |

| desmin | Positive (rare) | Marker of muscle differentiation; rare positivity may indicate limited myogenic features. |

| αSMA | Negative | Expressed in smooth muscle and myofibroblast differentiation. |

| CD10 | Negative | Usually positive in endometrial stromal sarcoma and some renal tumors. |

| CD34 | Negative | Typically positive in vascular tumors. |

| myogenin | Negative | Myogenic regulatory factor; negativity rules out rhabdomyosarcoma. |

| INSM1 | Negative | Sensitive marker for neuroendocrine differentiation. |

| S100 | Negative | Marker of neural or melanocytic origin. |

| CD99 | Positive (focal) | Expressed in Ewing sarcoma and other small round-cell tumors. |

| NKX2 | Negative | Expressed in Ewing sarcoma. |

| SALL4 | Negative | Marker for germ cell tumors. |

| BCOR | Non-specific | Nuclear expression may indicate BCOR-rearranged sarcomas; interpretation should be carefully performed. |

| inhibinα | Negative | Marker of sex cord-stromal differentiation; negativity argues against such origin. |

| Melan A | Negative | Melanocytic marker; negative in non-melanocytic tumors. |

| HMB45 | Negative | Marker of melanocytic differentiation. |

| CD45 | Negative | Leukocyte common antigen; negativity rules out hematolymphoid origin. |

| CD117 | Negative | Positive in GIST and some germ cell tumors. |

| ARID1A | Retained | Retained expression suggests no loss-of-function mutation in the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. |

| ARID1B | Retained | |

| INI-1 | Retained | |

| BRG1 | Retained | |

| PMS2 | Retained | Mismatch repair proteins; retained expressions suggest microsatellite stability. |

| MSH6 | Retained | |

| Ki-67 | 70% | Proliferation index: higher values suggest aggressive behavior. |

| Case | Author | Year | Age, Sex | Clinical Primary Site |

Pelvic Gynecological Lesion |

Gene Fusion | IHC | Initial Serum CA125 |

Surgery | Chemotherapy / Radiotherapy |

Progression-Free Survival | Overall Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jiang et al. [7] | 2023 | 53, F | Ovary | Bilateral ovary | MXI1::NUTM1 | NUT(+), ER/PgR(+), p40(-), p63(-), Pan CK(-) |

469 | Diagnostic laparoscopy; IDS (TAH, bilateral SO, omentectomy, PLN, small intestine resection) | 3 cycles of Paclitaxel, Carboplatin, and Bevacizumab (NAC) <SD> | 6 months | 8 months (DOD) |

| 2 | Jung et al. [4] | 2021 | 54, F | Ovary | Bilateral ovary involving uterus (12×12 cm) | – | NUT(+), ER/PgR(+), p40(-), p63(-), Pan CK (faint +), Vimentin (focal +) |

502 | – | 2 cycles of Bleomycin, Etoposide, and Cisplatin <PD> | 2 months | NA |

| 3 | Stevens et al. [8] | 2019 | 32, F | Ovary and lung | Ovary | BRD4::NUTM4 | NUT(+), AE1/AE3(+) | NA | NA | NA | – | NA |

| 4 | Ball et al. [9] | 2012 | 19, F | Ovary and lung | Left ovary (15×12 cm) | BRD4::NUTM4 | NUT(+), p63(+), WT-1(-) | NA | – | 4 cycles of Bleomycin, Etoposide, and Cisplatin <PD> | – | 5 months (DOD) |

| 5 | Higashi-no et al. [10] | 2022 | 22, F | Supraglottis | Right ovary (12 cm) | – | NUT(+), p40(+), AE1/AE3(+), CK20(-) | 125 | Right SO | Chemoradiotherapy (Cisplatin) <PD>; Cetuximab and Paclitaxel <PD>; Nivolumab <PD> |

0.5 months | 7.5 months (DOD) |

| 6 | Dragoescu et al. [11] | 2015 | 38, F | Lung | Bilateral ovary (left 10 cm, right 2.7 cm) | – | NUT(+), ER(-), p63(+), CK5/6(+), CK7 (focal +), CK20(-) |

88 | Video-assisted right pleural biopsy; bilateral SO | Whole-brain external beam radiotherapy | – | 2.5 months (DOD) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).