1. Introduction

Human spaceflight exposes crews to extreme physical, cognitive, and psychosocial stressors, including microgravity, radiation, isolation, confinement, and high operational risk. Astronauts must operate complex systems, conduct scientific research, and respond effectively to time-critical contingencies, often with limited ground support. Consequently, astronaut selection represents a critical gateway for mission success and crew safety.

Historically, astronaut selection emphasized piloting skills and physical endurance. Modern exploration missions, however, require a broader skill set encompassing scientific expertise, systems thinking, autonomy, and interpersonal competence. As international space agencies pursue long-duration lunar missions and prepare for eventual Mars exploration, astronaut selection processes have evolved to incorporate advances in human factors research, behavioral health assessment, and team performance science. NASA’s Astronaut Candidate Program and ESA’s astronaut selection framework reflect this transition towards multidisciplinary and human-centred selection models [

1,

4].

This paper analyses current astronaut selection frameworks at NASA and ESA, focusing on selection criteria, procedural stages, and the growing role of quantitative human-factor metrics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Criteria for Astronaut Selection

Table 1 summarizes the main criteria for astronaut selection.

2.1.1. Educational Qualifications

Both NASA and ESA require astronaut candidates to possess at least a bachelor’s degree in a STEM discipline, including engineering, physical sciences, biological sciences, mathematics, or medicine [

1,

4]. Advanced degrees at the master’s or doctoral level are strongly preferred and are increasingly common among selected candidates.

Scientific training is particularly relevant for exploration missions involving planetary surface operations. Astronauts are expected to act as field scientists, conducting geological surveys, biological experiments, and systems diagnostics in environments where real-time guidance from Earth may be limited.

2.1.2. Professional and Operational Experience

Professional experience serves as a key indicator of a candidate’s ability to apply knowledge under operational constraints. NASA typically requires a minimum of three years of progressively responsible professional experience, while military pilots may substitute extensive flight hours in high-performance aircraft.

Operational backgrounds in test piloting, emergency medicine, systems engineering, and research leadership demonstrate competence in decision-making under uncertainty—an essential skill for spaceflight operations.

2.1.3. Medical and Physiological Standards

Astronaut candidates must meet stringent medical standards to ensure resilience to the physiological challenges of spaceflight. Evaluations assess cardiovascular health, musculoskeletal integrity, vestibular function, vision, and neurological status [

2,

5].

Exposure to microgravity induces physiological adaptations such as bone density loss, muscle atrophy, and fluid redistribution. NASA’s Human Research Program has identified these effects as key health and performance risks for long-duration exploration missions, necessitating rigorous baseline medical screening [

2].

2.1.4. Psychological and Behavioural Competence

Psychological suitability is a critical determinant of mission success. Astronauts must function effectively in isolated, confined, and extreme environments for extended durations. Selection criteria emphasize emotional stability, stress tolerance, cognitive flexibility, and interpersonal effectiveness.

Behavioural competence is evaluated through structured interviews, validated psychometric instruments, and group-based simulations. Research from spaceflight analogues and orbital missions indicates that interpersonal conflict and poor team cohesion represent significant operational risks during long-duration missions.

2.1.5. Human-Factor Metrics in Astronaut Selection

Modern astronaut selection increasingly incorporates quantitative human-factor metrics to supplement qualitative evaluations. These metrics are informed by evidence from spaceflight, ground-based analogues, and long-duration isolation studies conducted under the auspices of the NASA Human Research Program and ESA behavioural health research initiatives [

2,

6].

Table 2 summarizes the human-factor metrics used in astronaut selection.

2.1.5.1. Cognitive Performance Metrics

Cognitive performance is assessed using standardised neurocognitive test batteries. Core metrics include reaction time, working memory capacity, executive function, and spatial orientation accuracy.

NASA’s Human Research Program has identified that measurable decrements in executive function and cognitive throughput during spaceflight analogues are associated with increased operational risk and error likelihood during complex task execution [

3].

2.1.5.2. Psychological and Behavioural Metrics

Psychological suitability is evaluated using validated psychometric scales and behavioural indices, including stress tolerance, emotional stability, and adaptability. Physiological stress markers and observer-based behavioural ratings are often combined to provide robust assessments.

Evidence from spaceflight and analogue environments indicates that shorter recovery times following interpersonal stress events correlate with sustained mission performance and crew effectiveness [

7,

8,

9].

2.1.5.3. Team and Crew Dynamics Metrics

Crew cohesion and team dynamics are treated as measurable variables. Metrics include crew cohesion indices, communication efficiency, leadership adaptability, and conflict resolution effectiveness.

ESA behavioural health studies have shown that high crew cohesion scores are associated with reduced procedural deviations and improved task performance during simulated long-duration missions [

6].

2.2. Astronaut Selection Procedures

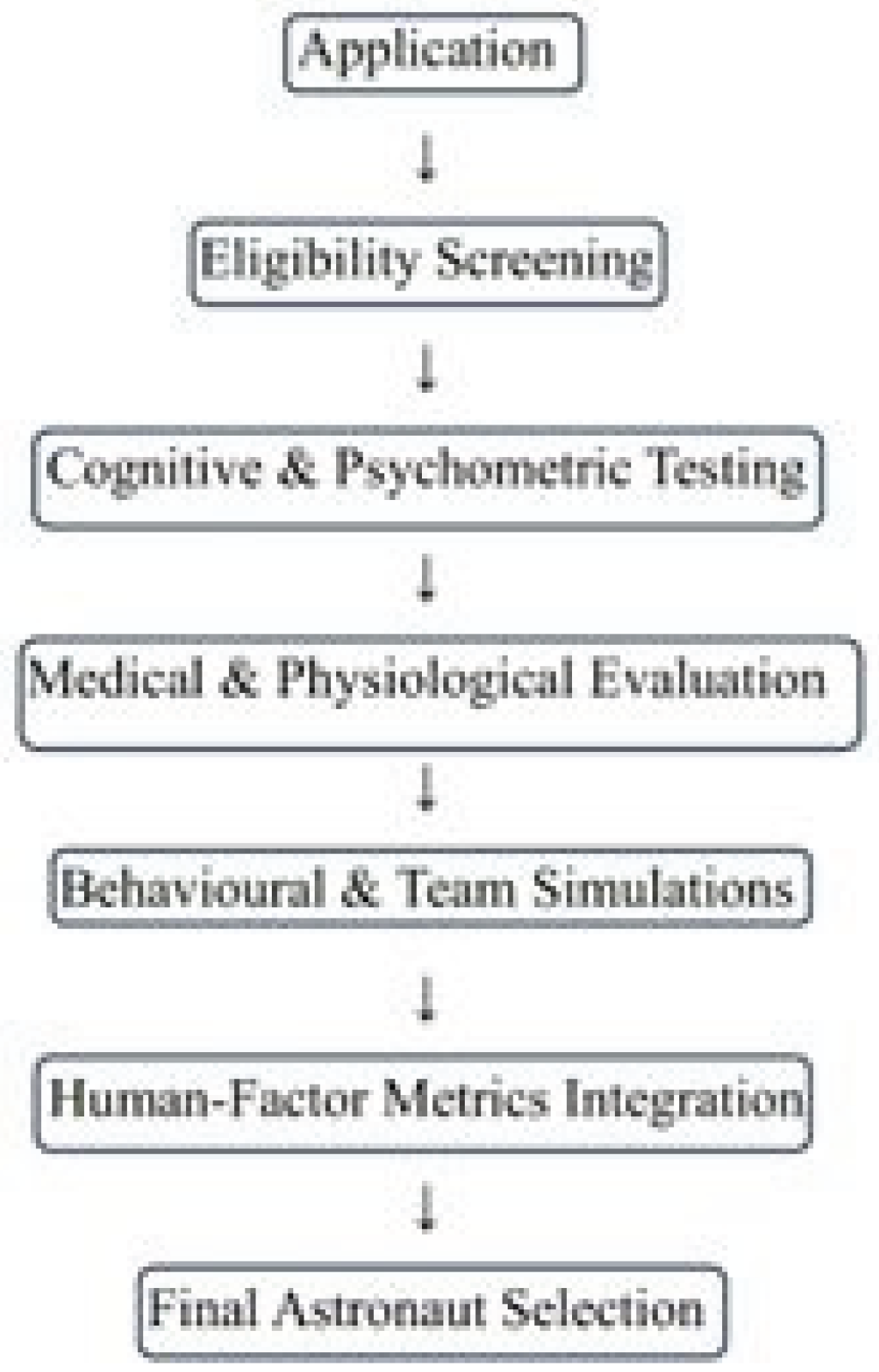

2.2.1. Application and Initial Screening

Astronaut selection begins with a competitive application process often involving thousands of applicants. Initial screening verifies compliance with baseline requirements such as education, citizenship, and professional experience. Only a small fraction of applicants advances beyond this stage.

2.2.2. Cognitive and Psychometric Evaluation

Shortlisted candidates undergo cognitive aptitude testing to assess problem-solving ability, spatial reasoning, memory, and decision-making speed. Psychometric instruments evaluate personality traits associated with teamwork, adaptability, and leadership.

2.2.3. Medical Evaluation

Candidates who pass initial assessments undergo comprehensive medical examinations conducted over several days. These include cardiovascular testing, neurological screening, vestibular assessments, and tolerance testing for acceleration and disorientation.

2.2.4. Behavioural Assessment and Group Simulations

Advanced selection stages include behavioural interviews and group-based simulations designed to observe interpersonal dynamics, leadership emergence, and conflict management strategies. Evaluations are conducted by multidisciplinary panels including astronauts, physicians, and psychologists.

2.2.5. Final Selection and Astronaut Candidacy

Final selections result in a small cohort of astronaut candidates who enter multi-year training programmes. Successful completion of training leads to astronaut certification, though mission assignment depends on program needs.

Figure 1.

Sequential stages of astronaut selection illustrating the integration of cognitive, medical, behavioural, and team-based human-factor metrics prior to final candidate selection.

Figure 1.

Sequential stages of astronaut selection illustrating the integration of cognitive, medical, behavioural, and team-based human-factor metrics prior to final candidate selection.

3. Results

3.1. Recent NASA Astronaut Selection

NASA’s recent astronaut candidate selections, conducted in support of the Artemis programme, emphasise interdisciplinary expertise and operational versatility. Selected candidates possess backgrounds in engineering, geosciences, medicine, and military aviation.

Training focuses on spacecraft systems, extravehicular activity, robotics, geological fieldwork, and survival skills. These competencies support NASA’s objective of sustained human presence on the Moon and preparation for future Mars missions, consistent with documented NASA astronaut training protocols [

10].

3.2. ESA Astronaut Selection Strategy

ESA’s latest astronaut recruitment campaign introduced a dual-track system comprising career astronauts and a reserve astronaut pool [

4]. This approach provides operational flexibility while maintaining a highly qualified cadre of mission-ready personnel.

ESA places particular emphasis on multicultural teamwork, multilingual communication, and international mission integration, reflecting Europe’s multinational operational framework and behavioural health research priorities [

6].

4. Comparative Discussion: NASA and ESA

4.1. Shared Selection Philosophy

While NASA and ESA share a common selection philosophy emphasising technical excellence, physical robustness, and psychological resilience, their implementation strategies differ in response to institutional mission profiles and workforce structures [

1,

4]. Selection standards are closely aligned to ensure interoperability during joint missions, including the International Space Station and planned lunar Gateway operations.

4.2. Institutional and Structural Differences

NASA maintains a larger permanent astronaut corps to support higher mission frequency and leadership roles. ESA employs a more flexible workforce model incorporating reserve astronauts, reflecting variable mission demand and multinational coordination.

4.3. Implications for Future Exploration

As missions extend beyond low-Earth orbit, selection criteria are likely to further emphasize autonomy, systems integration, and psychological endurance. Comparative analysis suggests that NASA’s operational scale and ESA’s adaptive workforce model are complementary, strengthening international exploration capacity.

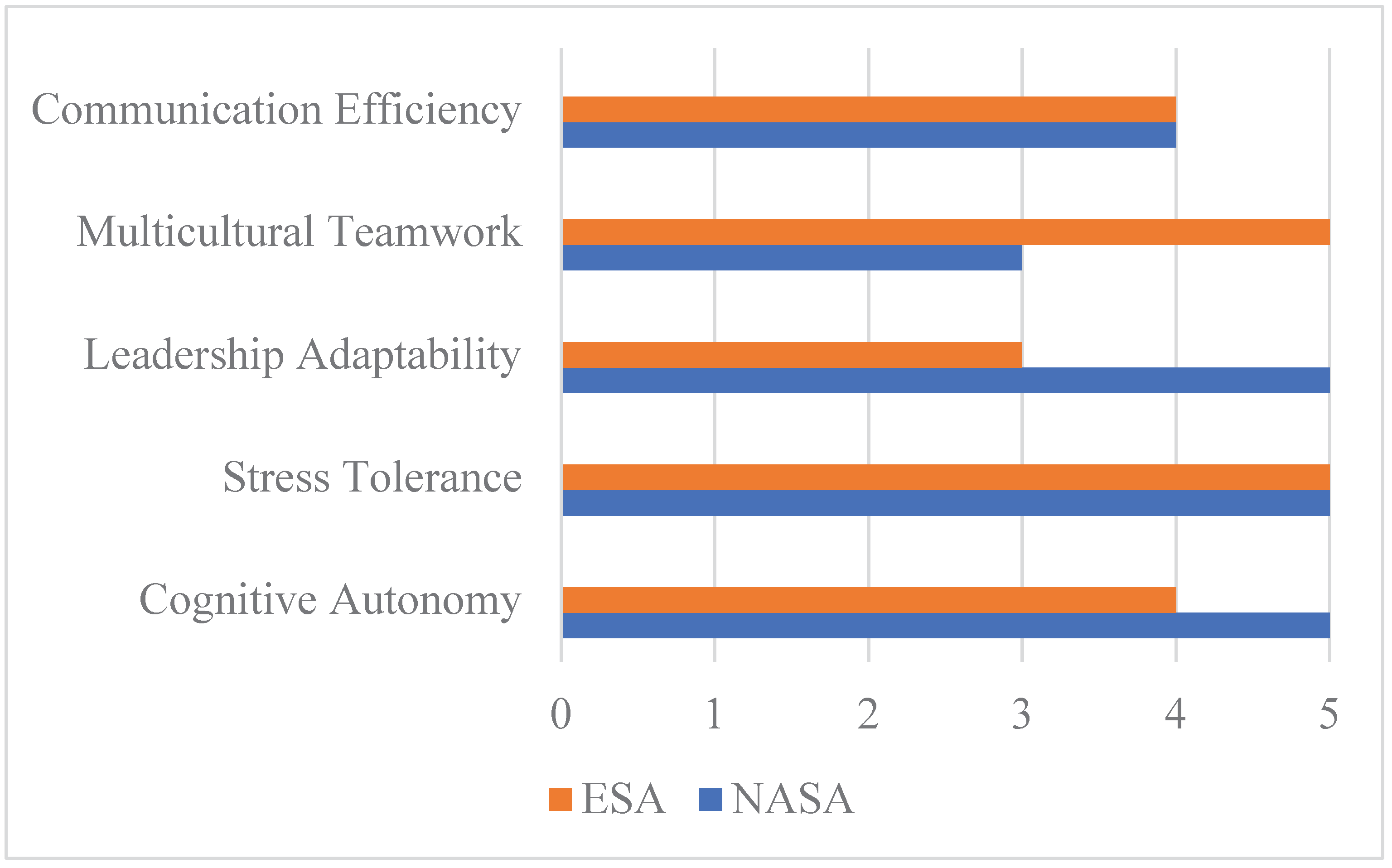

4.4. Comparative Human-Factor Emphasis: NASA vs. ESA

While NASA and ESA employ similar human-factor domains, their emphasis differs subtly due to institutional roles and mission architectures (see

Table 3).

NASA places stronger emphasis on individual autonomy, rapid decision-making, and operational leadership, reflecting mission command responsibilities and deep-space autonomy requirements under the Artemis program.

ESA emphasizes multicultural adaptability, communication efficiency, and long-term interpersonal stability, reflecting multinational crew compositions and rotating mission assignments.

Both agencies increasingly align their metrics to ensure behavioural interoperability during joint missions. Research in space psychology and human factors suggests that these complementary approaches enhance interoperability during joint missions while addressing agency-specific operational demands [

7,

8,

9].

Figure 2.

Comparative Emphasis on Human-Factor Domains in NASA and ESA Selection.

Figure 2.

Comparative Emphasis on Human-Factor Domains in NASA and ESA Selection.

5. Conclusions

Astronaut selection constitutes a foundational element of safe, sustainable, and effective human spaceflight operations. Modern selection frameworks reflect the increasing complexity of exploration missions, integrating advanced scientific expertise, operational experience, and quantitative human-factor metrics. Comparative analysis of NASA and ESA demonstrates convergence in core selection standards alongside strategic differences shaped by institutional roles. These complementary approaches will be essential as human exploration advances toward sustained lunar operations and eventual Mars missions.

For lunar surface missions and Mars transit scenarios, astronaut selection will increasingly prioritize autonomous decision-making capability, sustained cognitive performance under isolation, low interpersonal volatility, and high team adaptability over mission durations exceeding 12 months. Human-factor metrics will likely evolve from selection tools into continuous performance monitoring systems, informing crew composition and mission design.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT, version 5.2, for the purposes of generating text. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESA |

European Space Agency |

| NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| STEM |

Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics |

References

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Astronaut Candidate Program Overview. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/humans-in-space/astronauts/astronaut-selection-program/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Human Research Program. Human Health and Performance Risks of Space Exploration Missions. Available online: https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Human Research Program. Behavioral Health and Performance: Evidence Report. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20160004365/downloads/20160004365.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- European Space Agency (ESA). ESA Astronaut Selection: Timeline and Procedures. Available online: https://www.esa.int/About_Us/Careers_at_ESA/ESA_Astronaut_Selection (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- European Space Agency (ESA). Psychological_and_Medical_Selection_Process. Available online: https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/European_Astronaut_Selection_2008/Psychological_and_medical_selection_process (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- European Space Agency (ESA). Behavioral Health and Human Performance in Spaceflight. Available online: https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/Exploration/Human_health_and_performance (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Kanas, N.; Manzey, D. Space Psychology and Psychiatry; Springer, 2008; Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6770-9 (accessed on 15 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kanas, N., Sandal, G., Boyd, J., Gushin, V., Manzey, D., North, R., Leon, G., Suedfeld, P., Bishop, S., Fiedler, E., Inoue, N., Johannes, B., Kealey, D., Kraft, N., Matsuzaki, I., Musson, D., Palinkas, L., Salnitskiy, V., Sipes, W., . . . Wang, J. (2009). Psychology and culture during long-duration space missions. Acta Astronautica, 64(7-8), 659-677. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2008.12.005 (accessed on 15 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sandal, G.M.; Leon, G.R.; Palinkas, L.A. Human challenges in polar and space environments. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2006, 5, 281–296. Available online: https://ocw.unican.es/pluginfile.php/1002/course/section/576/4-12-11.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Johnson Space Center. Training for space, Astronaut Training and Mission Preparation. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/160410main_space_training_fact_sheet.pdfTitle of Site. Available online: URL (accessed 15 December 2025).

Table 1.

Core Astronaut Selection Criteria at NASA and ESA.

Table 1.

Core Astronaut Selection Criteria at NASA and ESA.

| Category |

NASA |

ESA |

| Minimum Education |

Bachelor’s degree (STEM) |

Bachelor’s degree (STEM) |

| Preferred Education |

Master’s / PhD |

Master’s / PhD |

| Professional Experience |

≥ 3 years or equivalent |

≥ 3 years |

| Medical Standards |

NASA Human Research Program |

ESA Medical Board |

| Psychological Screening |

Individual and group assessments |

Individual and group assessments |

| Language Requirements |

English (Russian preferred) |

English (additional languages valued) |

Table 2.

Representative Human-Factor Metrics Used in Astronaut Selection.

Table 2.

Representative Human-Factor Metrics Used in Astronaut Selection.

| Metric Category |

Example Metric |

Operational Relevance |

| Cognitive |

Reaction time (ms) |

Emergency response |

| Cognitive |

Executive function score |

Complex decision-making |

| Psychological |

Stress tolerance index |

Crisis management |

| Behavioural |

Conflict recovery time (h) |

Team stability |

| Team |

Crew cohesion index (%) |

Long-duration performance |

| Team |

Communication efficiency |

Error prevention |

Table 3.

Comparative Emphasis on Human-Factor Metrics.

Table 3.

Comparative Emphasis on Human-Factor Metrics.

| Human-Factor Domain |

NASA Emphasis |

ESA Emphasis |

| Cognitive autonomy |

High |

Moderate |

| Stress tolerance |

High |

High |

| Leadership adaptability |

High |

Moderate |

| Multicultural teamwork |

Moderate |

High |

| Communication efficiency |

High |

High |

| Behavioural stability |

High |

High |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).