Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

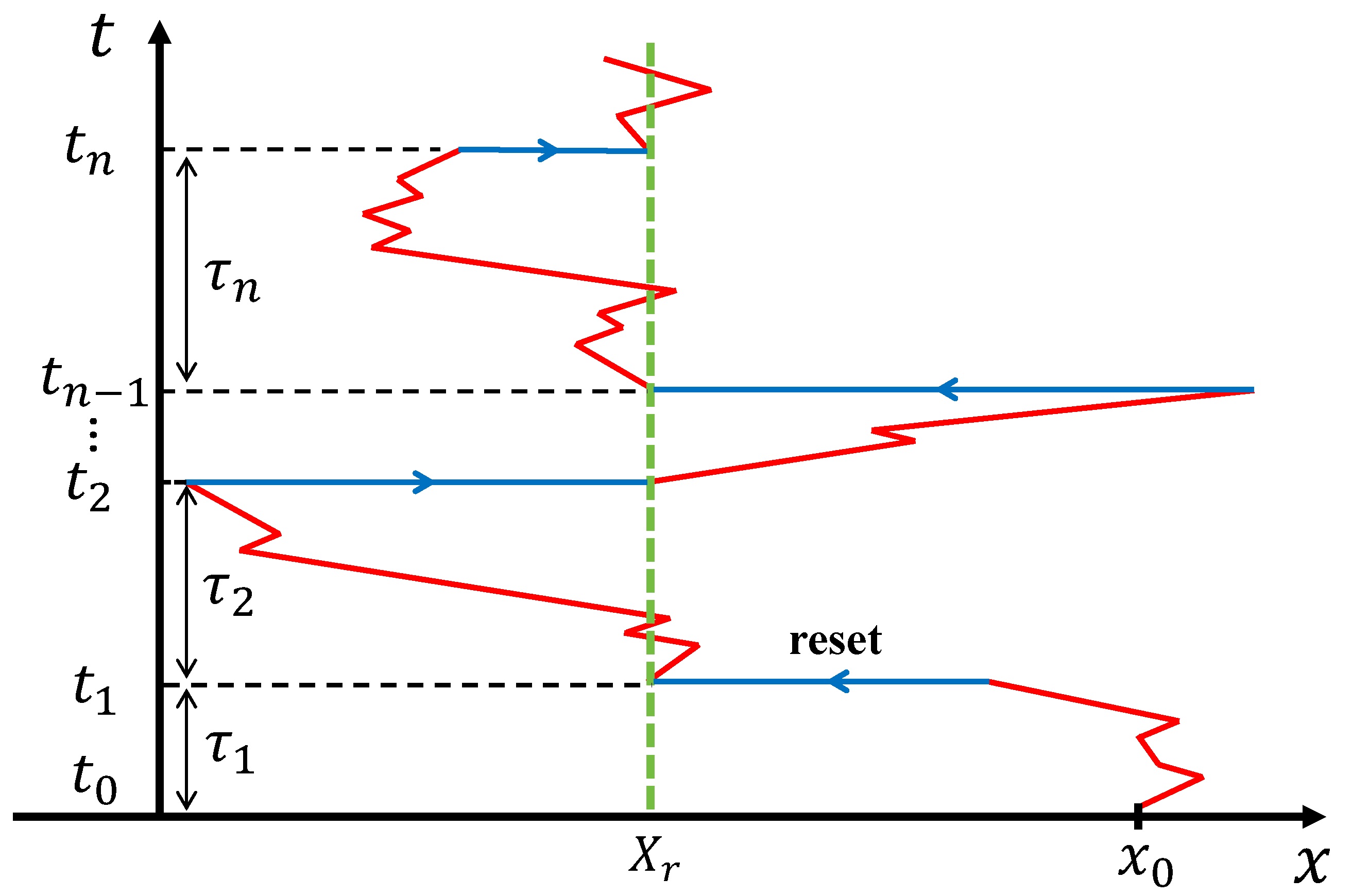

2. Lévy Walks Under Stochastic Resetting

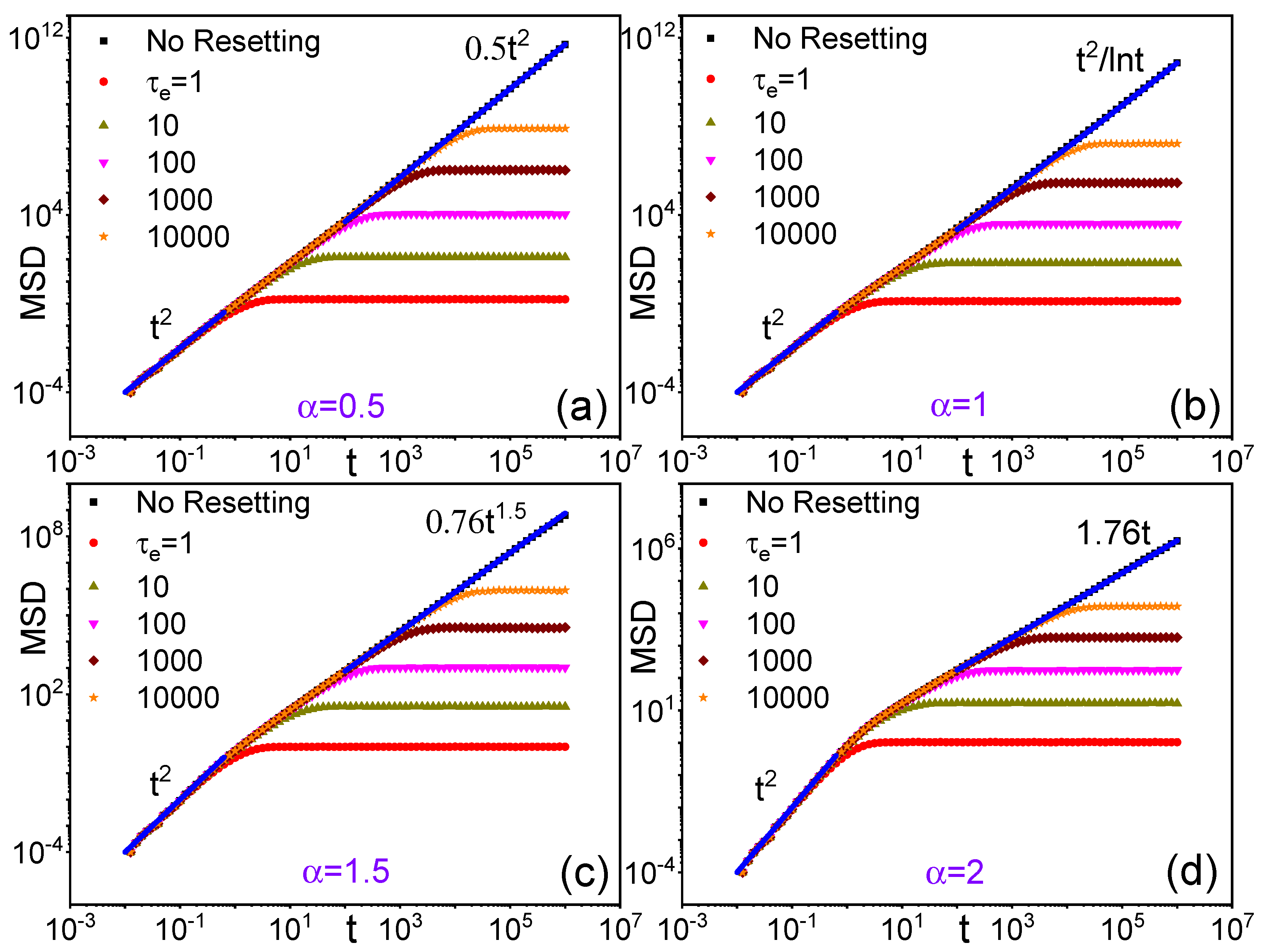

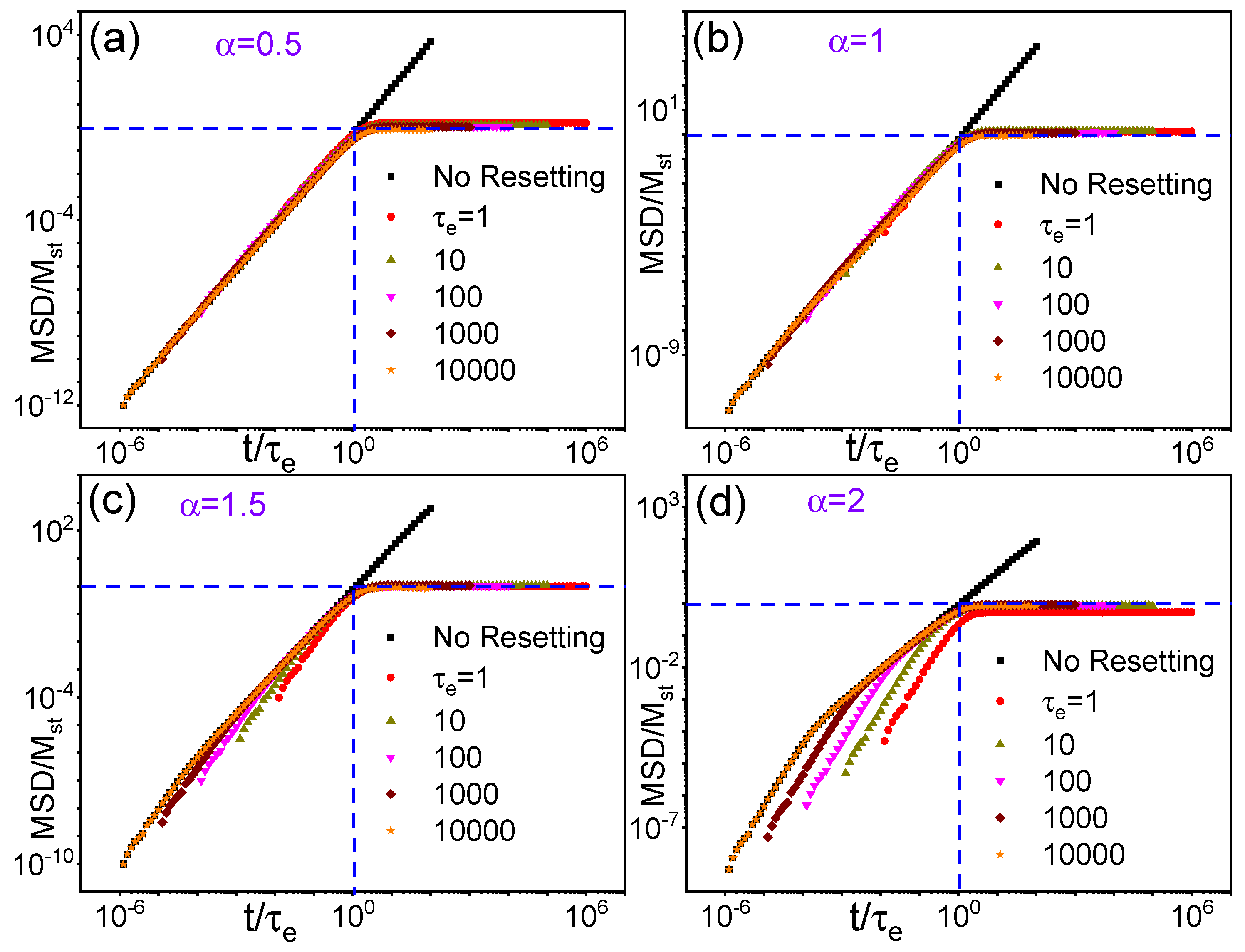

3. Lévy Diffusion Under Exponential Stochastic Resetting

3.1. Scaling Analysis and Diffusion Transition Times

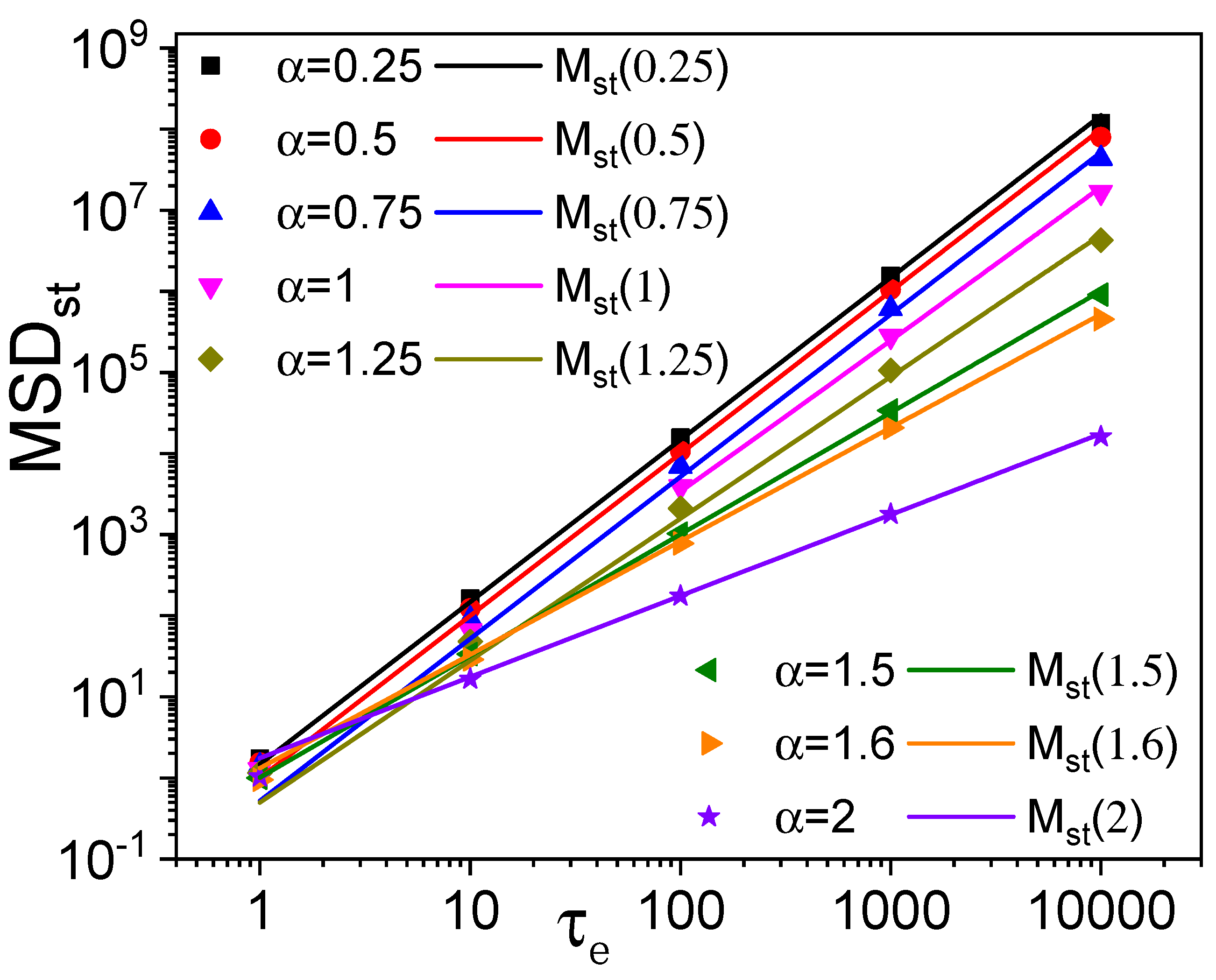

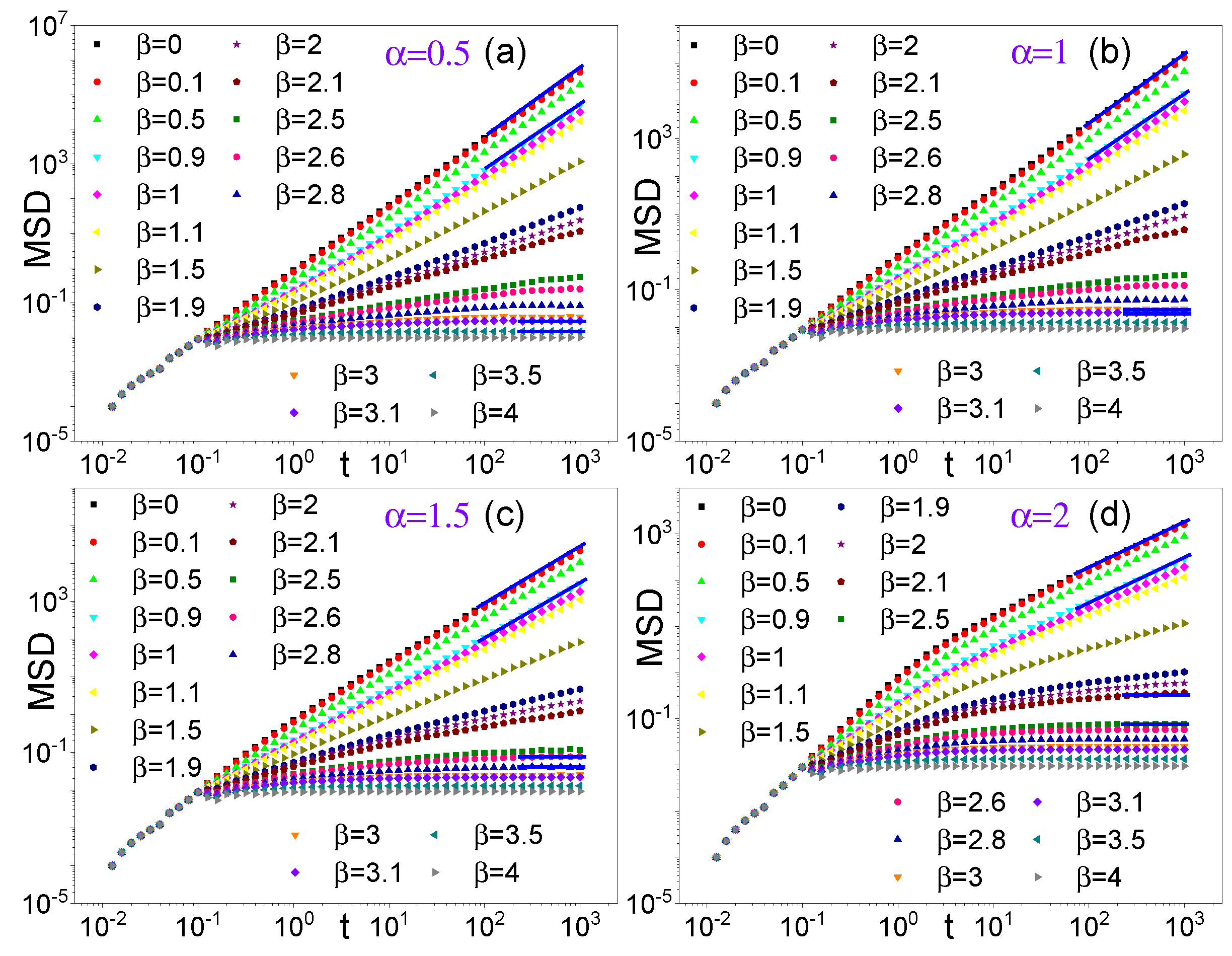

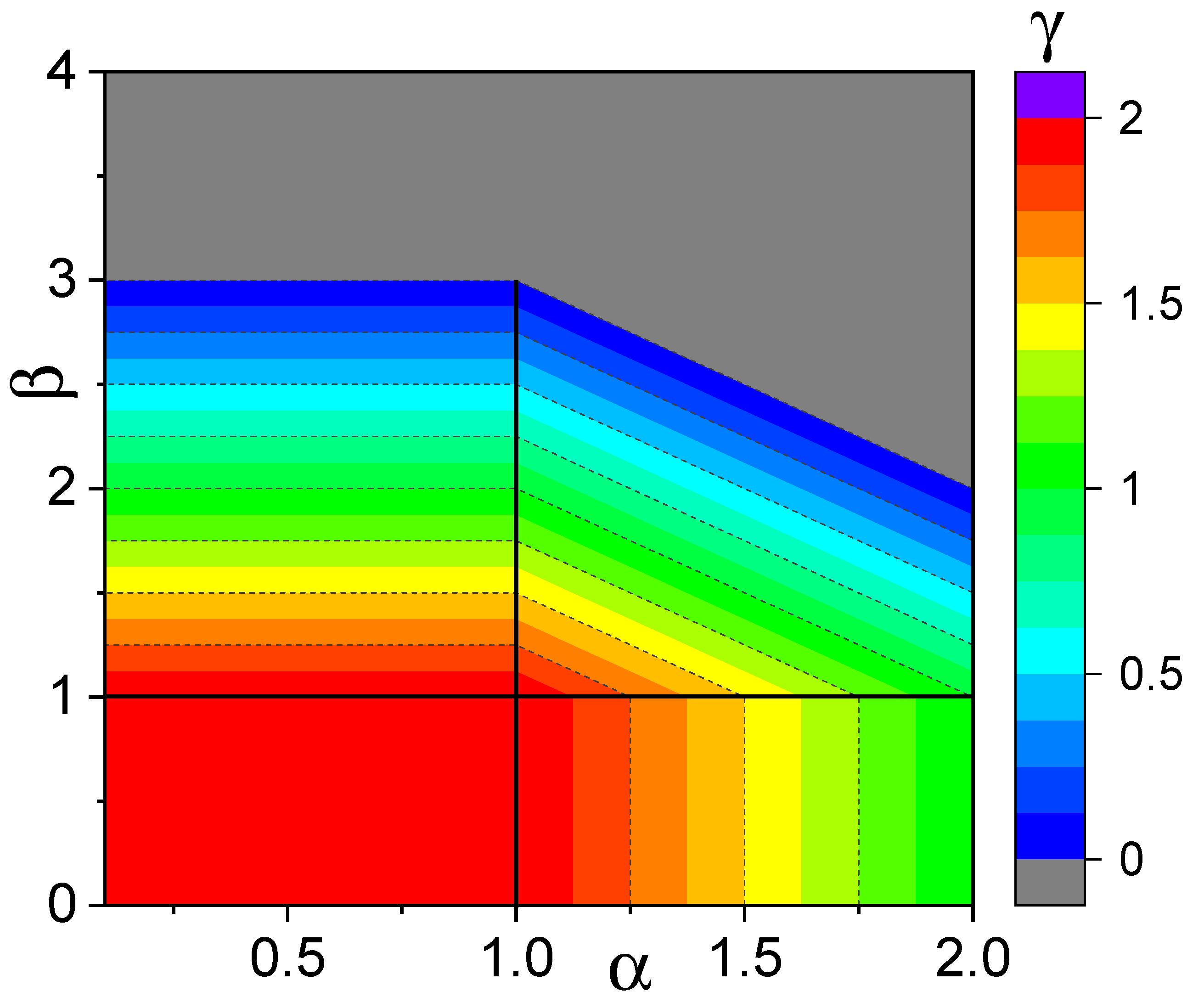

4. Lévy Diffusion Under Power-Law Stochastic Resetting

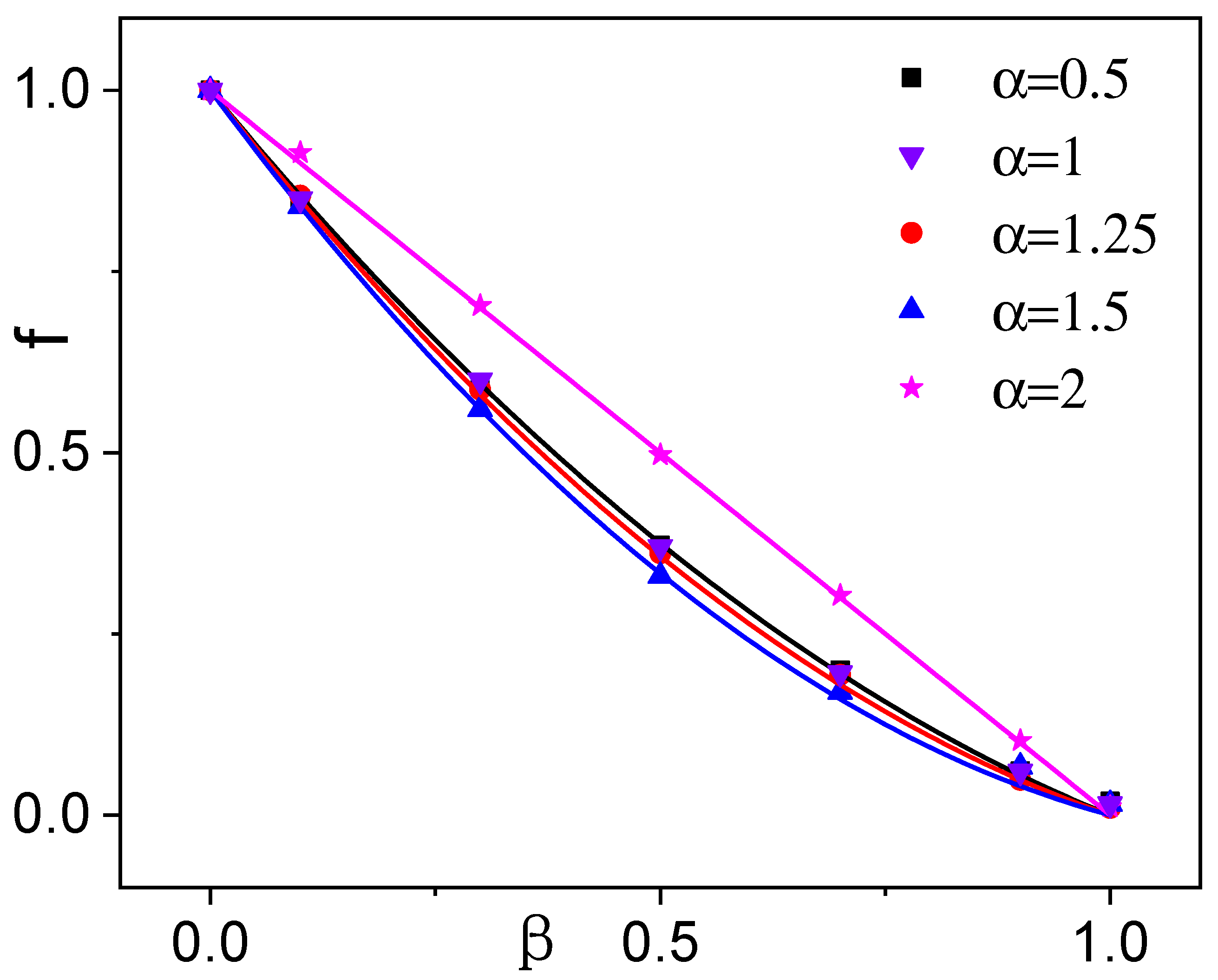

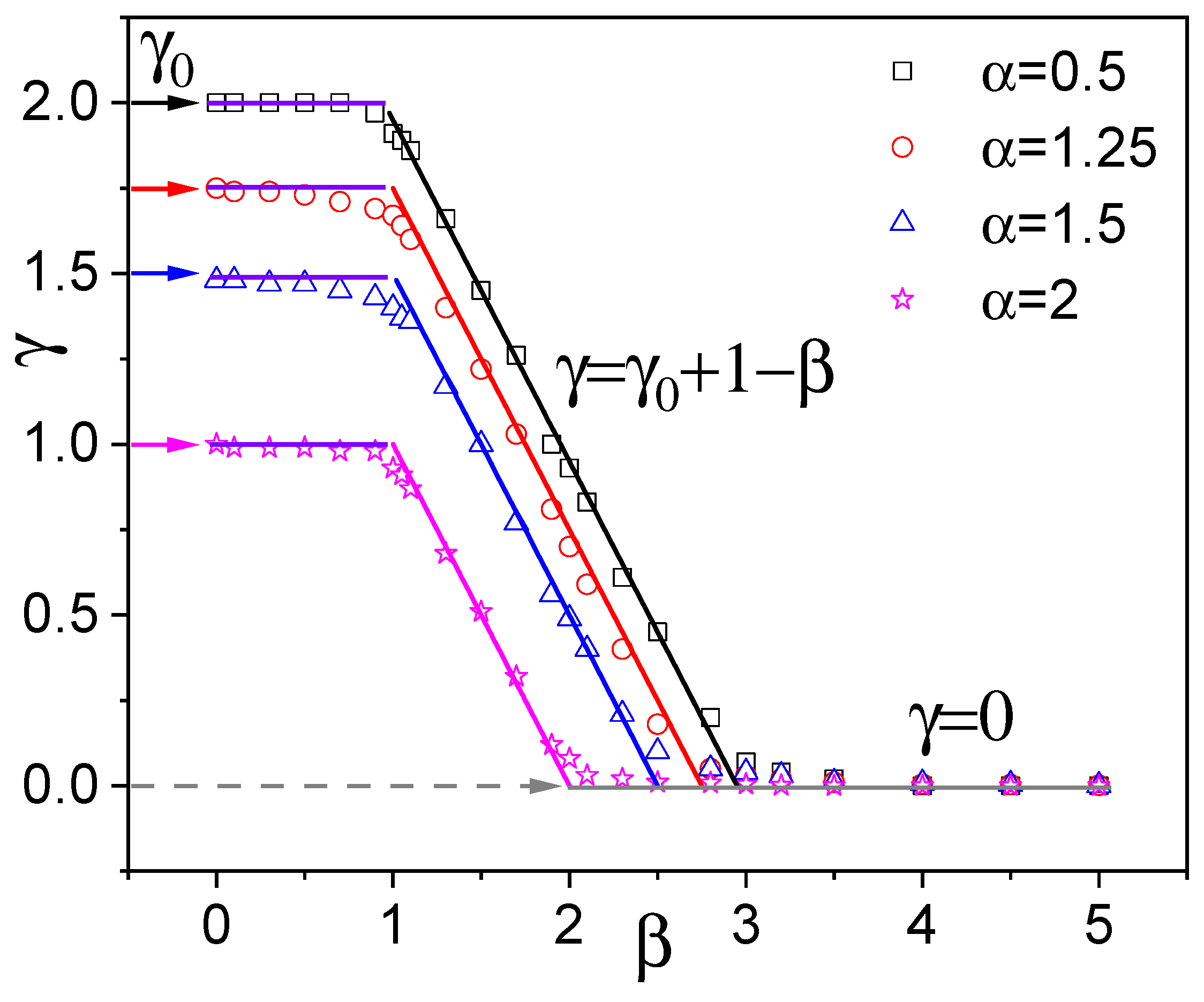

4.1. : SR Independent Diffusion Exponent

4.2. : Diffusion Exponent Attenuation

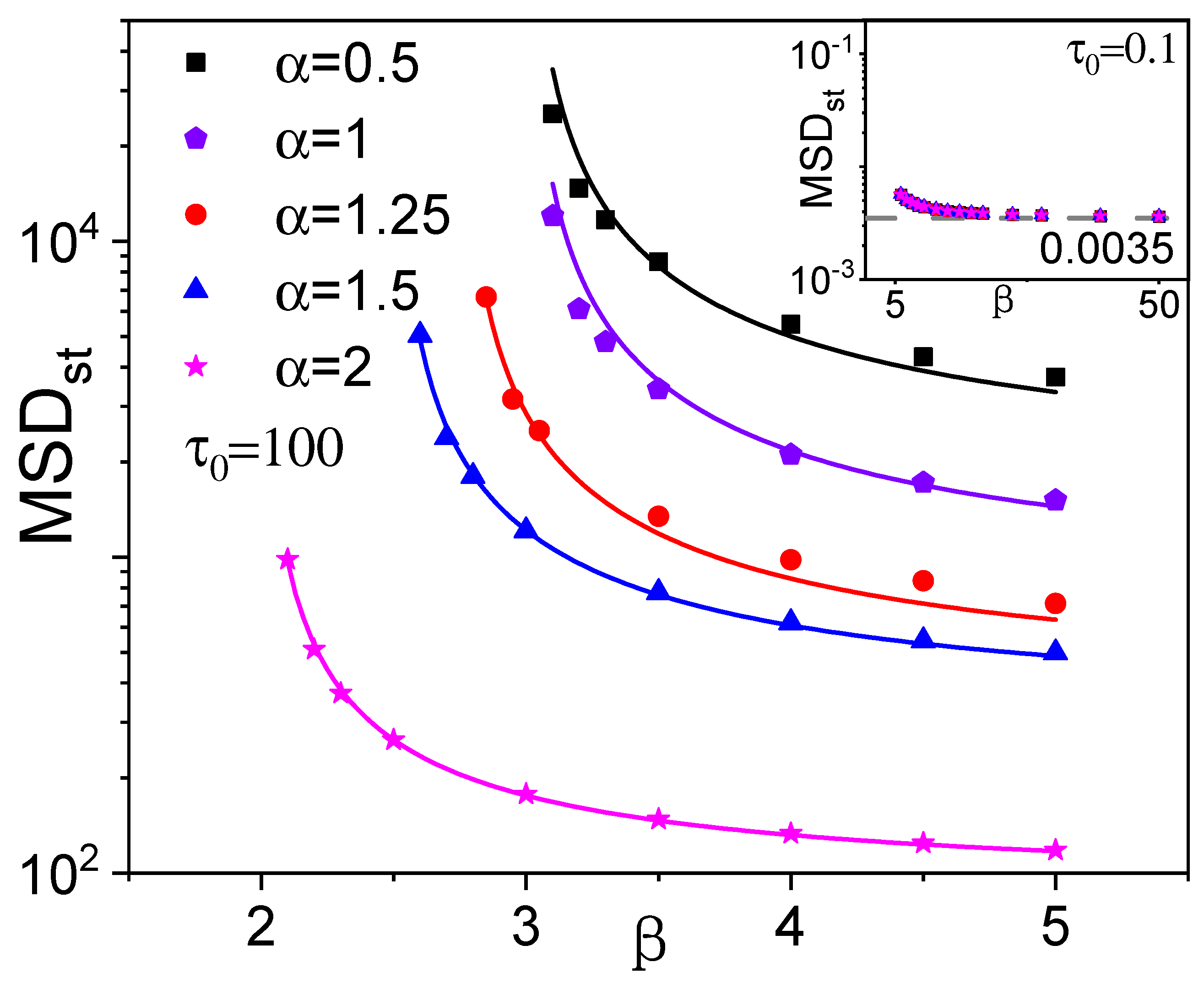

4.3. : Localization

4.4. The Case

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSD | mean squared displacment |

| SR | stochastic resetting |

| CTRW | continuous-time random walk |

References

- Viswanathan, G.M.; da Luz, M.G.E.; Raposo, E.P.; Stanley, H.E. The physics of foraging: an introduction to random searches and biological encounters; Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, G.M.; Buldyrev, S.V.; Havlin, S.; da Luz, M.G.E.; Raposo, E.P.; Stanley, H.E. Optimizing the success of random searches. Nature 1999, 401, 911–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, S.; Tang, M.; Zhang, H.P. Biased Lévy Walk Enables Light Gradient Sensing in Euglena gracilis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 108301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, T.H.; Banigan, E.J.; Christian, D.A.; Konradt, C.; Tait Wojno, E.D.; Norose, K.; Wilson, E.H.; John, B.; Weninger, W.; Luster, A.D. Generalized Lévy walks and the role of chemokines in migration of effector CD8+ T cells. Nature 2012, 486, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartumeus, F.; Catalan, J.; Fulco, U.L.; Lyra, M.L.; Viswanathan, G.M. Optimizing the Encounter Rate in Biological Interactions: Lévy versus Brownian Strategies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 097901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bénichou, O.; Coppey, M.; Moreau, M.; Suet, P.H.; Voituriez, R. Optimal Search Strategies for Hidden Targets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 198101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaburdaev, V.; Denisov, S.; Klafter, J. Lévy walks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015, 87, 483–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.R.; Majumdar, S.N.; Schehr, G. Stochastic resetting and applications. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 2020, 53, 193001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.R.; Majumdar, S.N. Diffusion with stochastic resetting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 160601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkharghani, A.; Waisbord, N.; Guasto, J.S. Self-transport of swimming bacteria is impaired by porous microstructure. Communications Physics 2023, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuveni, S.; Urbakh, M.; Klafter, J. The role of substrate unbinding in michaelis-menten enzymatic reactions. Biophysical Journal 2014, 106, 677a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, A.; Gupta, S. Diffusion with stochastic resetting at power-law times. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 93, 060102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmierz, L.; Majumdar, S.N.; Sabhapandit, S.; Schehr, G. First Order Transition for the Optimal Search Time of Lévy Flights with Resetting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 220602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Reuveni, S. First Passage under Restart. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 030603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuveni, S. Optimal Stochastic Restart Renders Fluctuations in First Passage Times Universal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 170601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal-Friedman, O.; Pal, A.; Sekhon, A.; Reuveni, S.; Roichman, Y. Experimental realization of diffusion with stochastic resetting. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 7350–7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Bao, J. The Lévy walk with rests under stochastic resetting. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2023, 2023, 073202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuśmierz; Gudowska-Nowak, E. Subdiffusive continuous-time random walks with stochastic resetting. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 99, 052116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Xu, P.; Deng, W. Continuous-time random walks and Lévy walks with stochastic resetting. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 013103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodrova, A.S.; Sokolov, I.M. Continuous-time random walks under power-law resetting. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 101, 062117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A.L. The origin of bursts and heavy tails in human dynamics. Nature 2005, 435, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.M.; Mallows, C.L.; Stuck, B.W. A method for simulating stable random variables. Journal of the american statistical association 1976, 71, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantegna, R.N. Fast, accurate algorithm for numerical simulation of Lévy stable stochastic processes. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 49, 4677–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoliver, J.; Lindenberg, K.; Weiss, G.H. A continuous-time generalization of the persistent random walk. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 1989, 157, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froemberg, D.; Barkai, E. Random time averaged diffusivities for Lévy walks. Eur. Phys. J. B 2013, 86, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żbik, B.; Dybiec, B. Lévy flights and Lévy walks under stochastic resetting. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 109, 044147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevast’yanov, B.A. Renewal theory. Journal of Soviet Mathematics 1975, 4, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.M. Stochastic processes; John Wiley & Sons, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, S.N.; Sabhapandit, S.; Schehr, G. Dynamical transition in the temporal relaxation of stochastic processes under resetting. Phys. Rev. E 2015, 91, 052131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowen, S.B.; Teich, M.C. Fractal renewal processes generate 1/f noise. Phys. Rev. E 1993, 47, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Ghosh, P.K.; Nayak, S.; Marchesoni, F. Ratcheting by Stochastic Resetting With Fat-Tailed Time Distributions. ChemPhysChem 2024, 25, e202400313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodrova, A.S.; Sokolov, I.M. Resetting processes with noninstantaneous return. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 101, 052130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theory | Simulation | Relative error | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 1% | ||

| 0.5 | 0% | ||

| 0.75 | 4% | ||

| 1 | 0% | ||

| 1.1 | 18% | ||

| 1.25 | 3% | ||

| 1.4 | 5% | ||

| 1.5 | 15% | ||

| 1.6 | 19% | ||

| 2 | 12% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).