1. Introduction

1.1. The ME/CFS Enigma

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) represents one of the most challenging conditions in modern medicine. Despite affecting millions globally and causing profound disability, its pathophysiology remains incompletely understood. Recent research increasingly recognises ME/CFS as a systemic neuroimmunological disease (Komaroff and Lipkin, 2021, pp. 895–906). However, mechanistic models capable of explaining its core features—post-exertional malaise (PEM), unrefreshing sleep, cognitive impairment, orthostatic intolerance, and the paradoxical coexistence of hyperarousal and exhaustion—remain elusive.

1.2. The ACE Connection

Epidemiological studies have identified an association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and ME/CFS risk, though large-scale prospective studies are lacking (Van Houdenhove et al., 2001, pp. 21–28). Clinical observation reveals patterns beyond classical acute trauma: chronic emotional neglect, excessive performance pressure, parentification, and conditional love based on achievement. These patients often exhibit self-critical perfectionism and high achievement orientation—patterns measurable via validated instruments such as the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and consistent with long-term stress adaptation (Kempke et al., 2013, pp. 995–1002).

The ACE-ME/CFS connection has typically been discussed in psychological or behavioural terms. This paper proposes a specific neurobiological mechanism: chronic programming of the locus coeruleus–norepinephrine (LC–NE) system, leading to metabolic exhaustion that renders the system vulnerable to collapse after an acute trigger.

1.3. Preliminary Pharmacological Observations

Clinical reports describe unusual response patterns to stimulant medications in some ME/CFS patients. Randomised controlled trials have demonstrated modest, short-term improvements in fatigue and executive function in subgroups: Young (2013, pp. 127–133) reported significant improvement in executive functioning with lisdexamfetamine over eight weeks; Blockmans et al. (2006, pp. 1047–1053) found methylphenidate produced moderate symptom reduction in a subset of patients. Importantly, neither study documented rapid tolerance development.

Anecdotal clinical observations (not derived from controlled studies) suggest a different pattern in some patients: marked initial improvement followed by rapid tolerance requiring dose escalation. This sequence—if confirmed prospectively—would be consistent with substrate limitation (vesicular depletion) rather than receptor dysfunction. This observation is presented as a hypothesis-generating clinical impression requiring controlled validation, not as established evidence.

Mechanistically, such a pattern would be plausible given known pharmacology: amphetamines increase cytosolic monoamine concentration and promote vesicular release via vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) interaction and transporter reversal; vesicle filling requires vacuolar-type ATPase (V-ATPase)-dependent proton gradient formation and adequate ATP availability; the conversion of dopamine to NE via dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH) is energy- and cofactor-dependent (Eiden and Weihe, 2011, pp. 86–98; Edwards, 2007, pp. 835–849). If vesicular stores were chronically depleted, forced release would produce pronounced but unsustainable effects.

1.4. Scope and Structure

This paper presents a conceptual framework linking ACEs to ME/CFS through chronic locus coeruleus dysfunction. We: (1) review neurobiological foundations; (2) propose a specific mechanism; (3) integrate clinical phenomena; (4) generate specific, testable predictions with proposed study designs; (5) discuss alternative explanations and limitations. This is a hypothesis paper that synthesises existing data and proposes testable mechanisms. It makes no therapeutic claims.

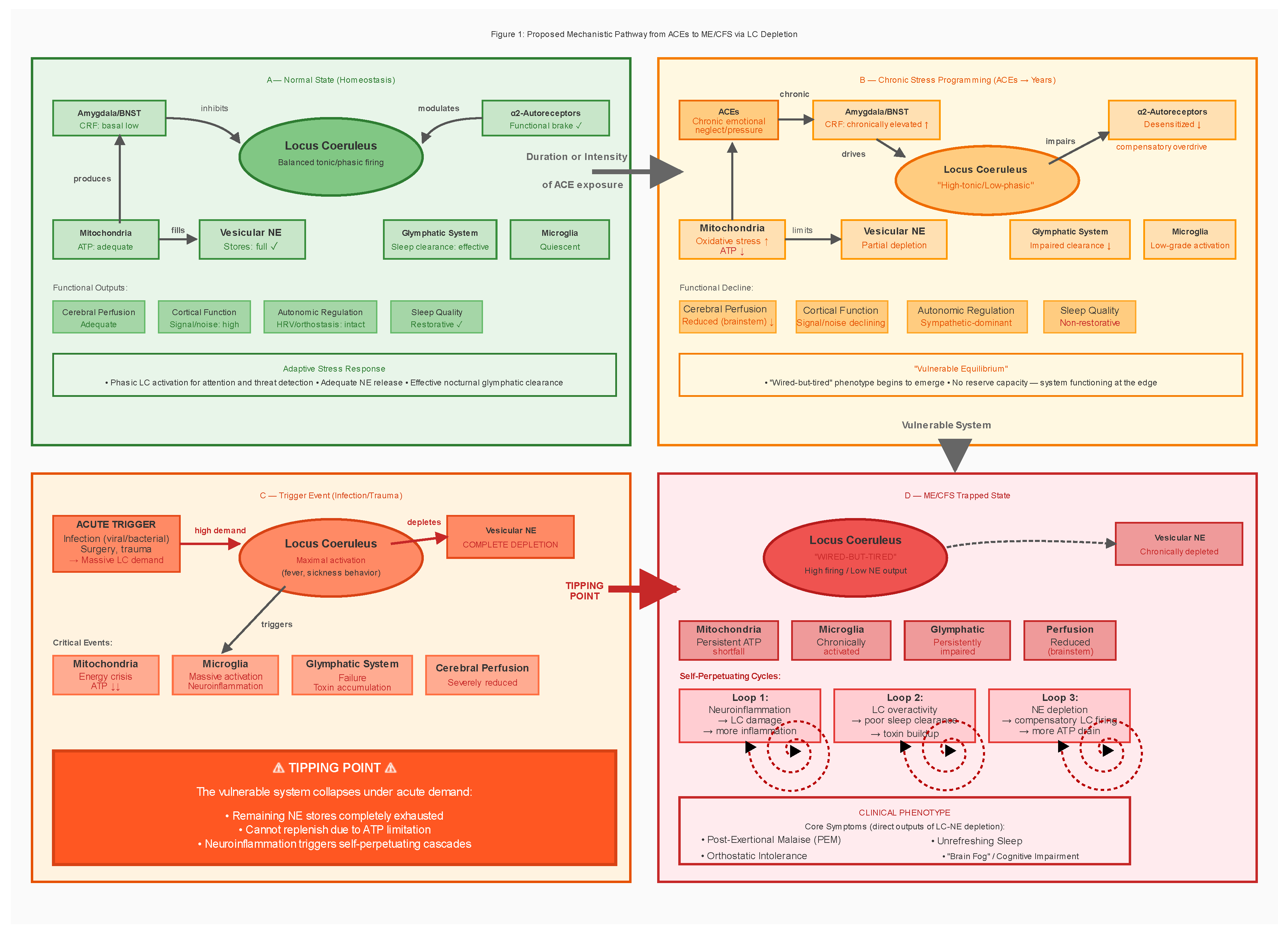

Figure 1.

Proposed Mechanistic Pathway from ACEs to ME/CFS via LC Depletion. Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism linking adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) through locus coeruleus (LC) dysfunction. Panel A shows normal LC function with balanced firing patterns and adequate norepinephrine (NE) levels. Panel B illustrates how chronic stress leads to high-tonic/low-phasic firing, mitochondrial exhaustion, and partial vesicle depletion. Panel C depicts an acute trigger (typically infection) overwhelming the vulnerable system. Panel D shows the trapped ME/CFS state characterised by self-perpetuating neuroinflammation, glymphatic dysfunction, and post-exertional malaise. Red arrows indicate positive feedback loops. Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; NE, norepinephrine; PEM, post-exertional malaise.

Figure 1.

Proposed Mechanistic Pathway from ACEs to ME/CFS via LC Depletion. Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism linking adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) through locus coeruleus (LC) dysfunction. Panel A shows normal LC function with balanced firing patterns and adequate norepinephrine (NE) levels. Panel B illustrates how chronic stress leads to high-tonic/low-phasic firing, mitochondrial exhaustion, and partial vesicle depletion. Panel C depicts an acute trigger (typically infection) overwhelming the vulnerable system. Panel D shows the trapped ME/CFS state characterised by self-perpetuating neuroinflammation, glymphatic dysfunction, and post-exertional malaise. Red arrows indicate positive feedback loops. Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; NE, norepinephrine; PEM, post-exertional malaise.

2. Neurobiological Foundations

2.1. The Locus Coeruleus: Anatomy and Function

The LC is a small, bilateral structure in the dorsal pons containing approximately 15,000–30,000 neurons per side. Despite its modest size, the LC supplies approximately 70–80% of the brain’s norepinephrine through extensive projections to virtually all brain regions (Schwarz and Luo, 2015, pp. R1051–R1056). Functional roles include: arousal and attention modulation; stress response (as primary brain target of CRF); memory consolidation; pain modulation via descending pathways; cerebrovascular regulation; and immune modulation through sympathetic outflow.

The Yerkes-Dodson relationship demonstrates that LC activity follows an inverted-U function: too-low activity produces drowsiness; optimal activity enables alert focus; too-high activity causes hypervigilance and cognitive disorganisation (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005, pp. 403–450). This balance is maintained through two firing modes: tonic activity (steady background firing at 2–5 Hz) and phasic activity (burst firing >10 Hz in response to salient stimuli).

2.2. The CRF-LC Stress Axis

Under stress, the following cascade occurs: threat detection by the amygdala; CRF release from the central amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST); LC activation as CRF binds to CRFR1 receptors; NE surge increasing alertness and readiness; and parallel hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation (Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008, pp. 194–203). This system is highly adaptive to acute threats. The problem arises with chronic activation.

2.3. ACEs: Programming the Stress System

The landmark ACE Study (Felitti et al., 1998, pp. 245–258), including over 17,000 participants, revealed a dose-response relationship between childhood adversity and adult health outcomes. Each additional ACE increases risk of cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, chronic pain syndromes, and neuroimmunological conditions. Crucially, these effects persist regardless of adult behaviour, indicating biological programming.

Neurobiological consequences of ACEs include: HPA axis dysregulation with flattened diurnal cortisol rhythm (Bunea et al., 2017, p. 1274); chronic low-grade inflammation with elevated C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumour necrosis factor-α (Baumeister et al., 2016, pp. 642–649); autonomic dysregulation with reduced heart rate variability; epigenetic modifications including methylation of the NR3C1 glucocorticoid receptor gene (McGowan et al., 2009, pp. 342–348; Perroud et al., 2011, p. e59); and brain structural changes including reduced hippocampal volume and increased amygdala reactivity.

Important caveats: The ACE-ME/CFS association is derived from cross-sectional data; prospective confirmation is lacking. Confounders including socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and retrospective reporting bias must be acknowledged. The model proposed here applies to a hypothesised subgroup with ACE histories; ME/CFS heterogeneity means other pathways likely exist.

2.4. LC Vulnerability to Chronic Stress

The LC has features making it particularly vulnerable to chronic stress. Metabolic fragility: High mitochondrial density reflects high energy demand; constant NE synthesis requires ATP via DBH; prolonged high firing rates generate oxidative stress. Autoreceptor desensitisation: α2-adrenergic autoreceptors normally inhibit NE release; with chronic CRF stimulation, these receptors desensitise, resulting in loss of negative feedback (Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008, pp. 194–203). The ‘high-tonic/low-phasic’ pattern: Chronic stress shifts the LC from responsive (phasic) to rigid (tonic) firing, documented in PTSD studies (Bangasser and Valentino, 2020, p. 601519), manifesting as hypervigilance with impaired attention shifting.

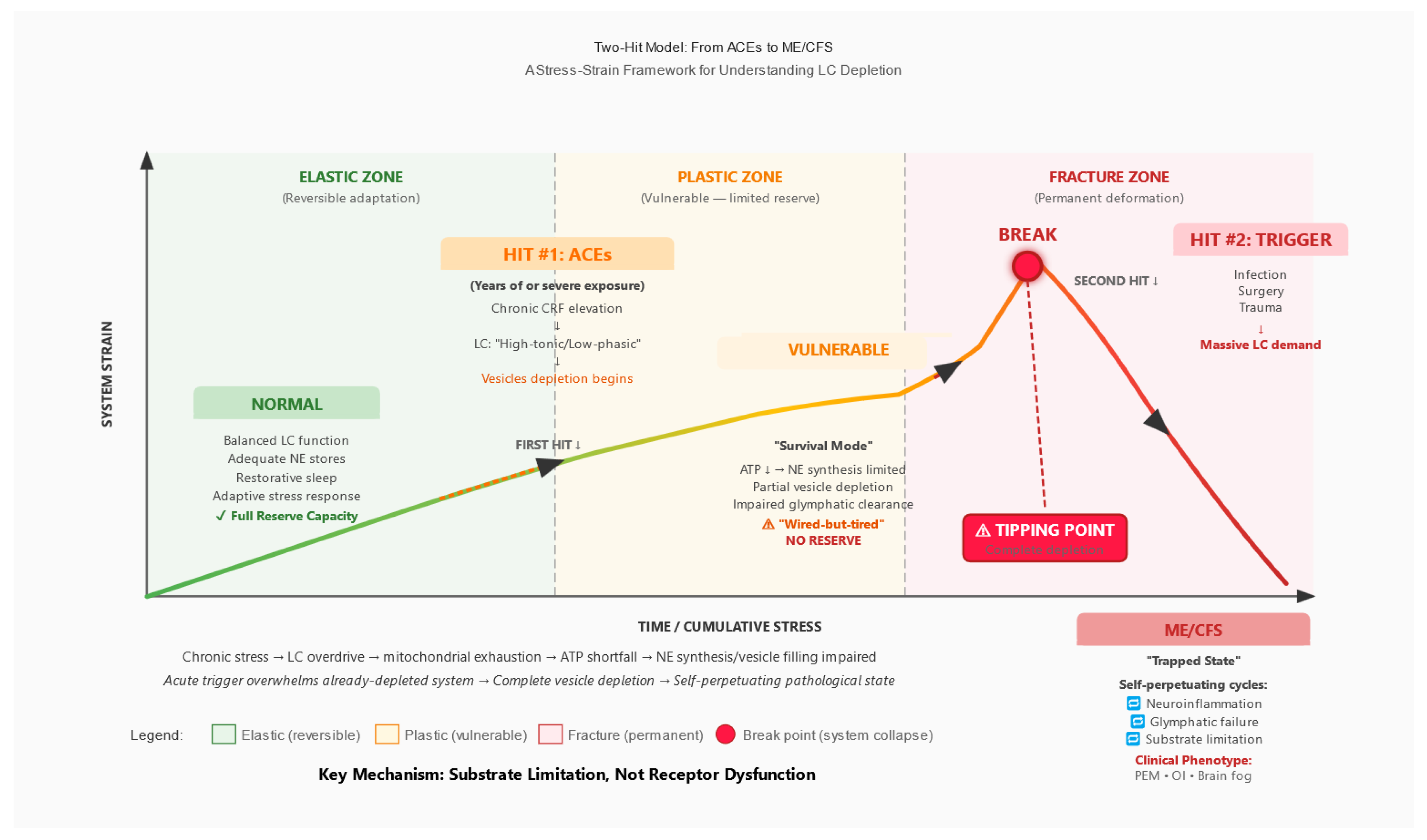

Figure 2.

Two-Hit Model: From ACEs to ME/CFS. A stress-strain framework illustrating the progression from normal state through vulnerable equilibrium to system collapse. Hit #1 (ACEs over years) produces chronic CRF elevation and LC programming into ‘high-tonic/low-phasic’ mode, creating a vulnerable state with depleted reserves. Hit #2 (acute trigger such as infection, surgery, or trauma) overwhelms the already-vulnerable system, crossing a tipping point into the trapped ME/CFS state with self-perpetuating pathological cycles. Key mechanism: substrate limitation (vesicular NE depletion), not receptor dysfunction. Abbreviations: ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; LC, locus coeruleus; NE, norepinephrine; OI, orthostatic intolerance; PEM, post-exertional malaise.

Figure 2.

Two-Hit Model: From ACEs to ME/CFS. A stress-strain framework illustrating the progression from normal state through vulnerable equilibrium to system collapse. Hit #1 (ACEs over years) produces chronic CRF elevation and LC programming into ‘high-tonic/low-phasic’ mode, creating a vulnerable state with depleted reserves. Hit #2 (acute trigger such as infection, surgery, or trauma) overwhelms the already-vulnerable system, crossing a tipping point into the trapped ME/CFS state with self-perpetuating pathological cycles. Key mechanism: substrate limitation (vesicular NE depletion), not receptor dysfunction. Abbreviations: ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; LC, locus coeruleus; NE, norepinephrine; OI, orthostatic intolerance; PEM, post-exertional malaise.

2.5. The Glymphatic Connection

The glymphatic system is the brain’s waste clearance mechanism (Nedergaard, 2013, pp. 1529–1530). During sleep, astrocytes shrink, expanding extracellular space by approximately 60%. Cerebrospinal fluid flows along perivascular spaces, washing out metabolic waste. Clearance is 10–20 times higher during sleep than during wakefulness (Xie et al., 2013, pp. 373–377).

Critical point: Effective glymphatic function requires reduced LC activity. Recent research has demonstrated that norepinephrine oscillations during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep are the strongest predictors of glymphatic clearance; optogenetic stimulation of the LC directly modulates cerebrospinal fluid flow, while pharmacological suppression of NE oscillations (e.g., with zolpidem) reduces glymphatic clearance by more than 30% (Hauglund et al., 2025, pp. 606–622). These findings establish a direct causal link between LC activity patterns and brain waste clearance. With chronic LC overactivation, the system cannot achieve the rhythmic NE fluctuations necessary for effective clearance; waste products accumulate, further damaging LC neurons in a vicious cycle. Clinical manifestation: ‘unrefreshing sleep.’

3. The Proposed Mechanism

3.1. Multi-Stage Model

We propose a multi-stage model from adaptation to exhaustion to collapse.

Stage 1 (Adaptive Response—Childhood/Adolescence): ACEs → chronic CRF elevation → sustained LC activation → hypervigilance pattern. From the child’s perspective, this is adaptive: in an unpredictable environment, constant vigilance is protective.

Stage 2 (Chronic Maladaptation—Years to Decades): Sustained high-tonic LC firing leads to progressive metabolic exhaustion: α2-autoreceptor desensitisation; mitochondrial dysfunction from chronic oxidative stress; ATP depletion; vesicular depletion (DBH is ATP-dependent); and the ‘wired-but-tired’ state where neurons fire at high rate but release inadequate NE.

Stage 3 (Vulnerable Equilibrium—Pre-ME/CFS): The system maintains function but has no reserve capacity. Vesicles are chronically depleted, mitochondria stressed, glymphatic clearance impaired, neuroinflammation subclinical. One more stressor will cause system collapse.

Stage 4 (The Trigger): Typically viral infection (e.g., EBV, SARS-CoV-2, influenza), but may include major surgery, physical trauma, severe psychological stress, or pregnancy/childbirth. Massive LC activation occurs; complete vesicular depletion follows; post-infectious neuroinflammation persists; failed recovery ensues as the pre-damaged system cannot restore homeostasis.

Stage 5 (ME/CFS—Trapped State): The system becomes locked in pathological equilibrium: high neuronal activity with low NE output; persistent neuroinflammation; continued glymphatic dysfunction; progressive mitochondrial failure; PEM from any increased demand; orthostatic intolerance; cognitive impairment; unrefreshing sleep. Positive feedback loops trap the system.

3.2. Differentiation from Existing Two-Hit Models

Two-hit models exist in ME/CFS literature (Komaroff and Lipkin, 2021, pp. 895–906). The present model differs by specifying: (1) the precise neuroanatomical target (LC rather than diffuse ‘stress response’); (2) the cellular mechanism (vesicular NE depletion via ATP limitation rather than receptor dysfunction); (3) the link to glymphatic failure explaining unrefreshing sleep; and (4) testable predictions at cellular, circuit, and systems levels.

4. Clinical Phenomena Through the LC Depletion Lens

4.1. The ‘Wired-but-Tired’ Paradox

ME/CFS patients simultaneously exhibit hypervigilance, anxiety, difficulty ‘turning off,’ profound fatigue, inability to sustain activity, and disrupted sleep despite exhaustion. Mechanistic explanation: ‘Wired’ reflects high-tonic LC firing (desensitised autoreceptors). ‘Tired’ reflects empty vesicles with inadequate NE release despite high neuronal activity. The system runs at high RPMs but produces inadequate output.

4.2. Post-Exertional Malaise

Physical or cognitive exertion produces delayed (24–72 hours) severe symptom exacerbation, often lasting days to weeks. Mechanistic explanation: Exertion requires NE mobilisation; vesicles release remaining content; compromised mitochondria cannot rapidly resynthesise NE or refill vesicles; days are required for partial recovery (versus hours for healthy individuals).

4.3. Orthostatic Intolerance

Upon standing, many ME/CFS patients experience dizziness, tachycardia, cognitive impairment, and nausea. Mechanistic explanation: Vasoregulation requires NE to prevent blood pooling; with inadequate NE, compensation fails; heart rate increases to maintain cerebral perfusion. This reflects apparent sympathetic overactivity (tachycardia) with reduced effective central noradrenergic output. Comorbidities such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and small fibre neuropathy (SFN) may act as moderator variables.

4.4. Unrefreshing Sleep

Sleep provides minimal restoration; patients often wake feeling as exhausted as when they went to bed. Mechanistic explanation: Glymphatic clearance requires rhythmic NE oscillations during NREM sleep (Hauglund et al., 2025, pp. 606–622); with chronic high-tonic LC firing, the system cannot achieve these oscillations; waste products accumulate; vesicles cannot refill (DBH requires ATP); morning cortisol surge activates a system with no reserve.

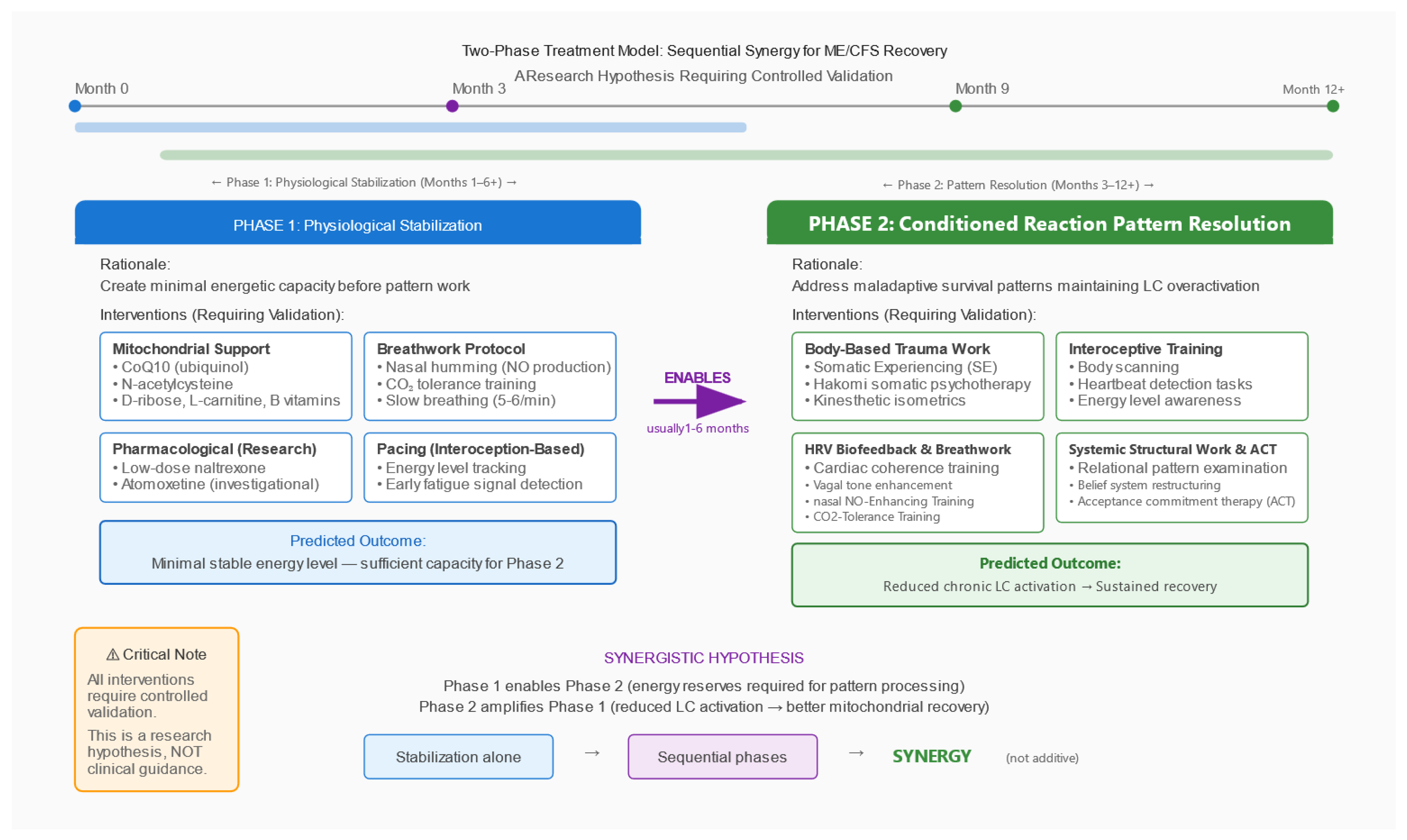

Figure 3.

Two-Phase Treatment Model: Sequential Synergy Hypothesis. Proposed therapeutic framework requiring controlled validation. Phase 1 (Physiological Stabilisation) creates minimal energetic capacity through mitochondrial support, pacing, breathwork, and pharmacological modulation. Phase 2 (Pattern Resolution) addresses maladaptive survival patterns through body-based trauma therapies, interoceptive training, and HRV biofeedback. Key insight: Phase 2 is only possible after Phase 1, but Phase 2 amplifies the effects of Phase 1 synergistically. This is a research hypothesis, not a treatment recommendation.

Figure 3.

Two-Phase Treatment Model: Sequential Synergy Hypothesis. Proposed therapeutic framework requiring controlled validation. Phase 1 (Physiological Stabilisation) creates minimal energetic capacity through mitochondrial support, pacing, breathwork, and pharmacological modulation. Phase 2 (Pattern Resolution) addresses maladaptive survival patterns through body-based trauma therapies, interoceptive training, and HRV biofeedback. Key insight: Phase 2 is only possible after Phase 1, but Phase 2 amplifies the effects of Phase 1 synergistically. This is a research hypothesis, not a treatment recommendation.

5. Supporting Evidence and Alternative Explanations

5.1. Evidence Supporting the Hypothesis

Biological plausibility: LC metabolic vulnerability is well-established; CRF-LC stress coupling is characterised; chronic stress leads to mitochondrial dysfunction; vesicular monoamine storage requires ATP; glymphatic clearance requires reduced LC activity.

Clinical phenomenology: The hypothesis explains the ‘wired-but-tired’ paradox, PEM, orthostatic intolerance, unrefreshing sleep, cognitive impairment, and coexisting hypervigilance and fatigue.

Dysautonomia profile: Reduced HRV is documented in ME/CFS (Nelson et al., 2019, p. e17600); orthostatic intolerance with reduced cerebral blood flow is documented (van Campen et al., 2020, p. 169); paradox of apparent sympathetic overactivity with ineffective central noradrenergic output is consistent with hyperactive neurons having inadequate neurotransmitter release.

Preliminary conference data (not peer-reviewed): Conference presentations at IACFS/ME 2025 reported findings consistent with this hypothesis, including low brain NE (Goldstein and Aregawi, 2025, conference abstract), reduced CRH-producing neurons in autopsy study (Da Silva et al., 2025, conference abstract), and sympathetic dysfunction meta-analysis (Hendrix et al., 2025, conference abstract). These presentations are hypothesis-generating and await peer review; they are not evidence on which the present model depends.

5.2. Alternative and Complementary Mechanisms

The LC depletion hypothesis is not mutually exclusive with other mechanisms: autoimmune mechanisms including β2-adrenergic receptor autoantibodies (Wirth and Scheibenbogen, 2020, p. 102527); small fibre neuropathy documented in significant subset; mast cell activation (histamine affects LC firing); cerebrovascular dysfunction with reduced cerebral blood flow; mitochondrial dysfunction which could be primary or secondary (Naviaux et al., 2016, pp. E5472–E5480); and immune-mediated LC damage from post-viral neuroinflammation (Nakatomi et al., 2014, pp. 945–950). The present hypothesis emphasises one pathway; ME/CFS is likely heterogeneous with multiple pathways converging on similar end states.

5.3. Limitations and Uncertainties

(1) No direct measurements of vesicular NE content in ME/CFS LC neurons exist. (2) The ACE-ME/CFS link is associative from cross-sectional data; prospective studies are lacking; confounders (socioeconomic status, comorbidities, recall bias) are not fully controlled. (3) Pharmacological observations regarding tolerance are anecdotal, not from controlled studies. (4) Conference data are preliminary. (5) Causal direction is unclear and likely bidirectional. (6) The model may be incomplete, focusing on LC while missing other critical nodes.

6. Testable Predictions and Research Agenda

To enable empirical evaluation of the model, we specify falsifiable predictions and corresponding study plans (primary endpoints, covariates, and power/analysis). MRI methods will conform to COBIDAS-MRI recommendations; PET acquisition, modelling, and quantification will follow SNMMI procedure standards and QIBA guidance; HRV analysis will follow the Task Force recommendations; and observational reporting will follow STROBE. Site-specific OSF preregistration and local IRB approval will precede any data collection.

6.1. Neuromelanin-Sensitive MRI of the LC

Prediction: LC contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) will be reduced in ME/CFS patients compared to controls and will correlate inversely with ACE score (CTQ total; a priori anticipated: r < −0.5) and symptom severity.

Design: Cross-sectional comparison; ME/CFS (n ≥ 60) vs. healthy controls (n ≥ 60), stratified by ACE score tertiles.

Primary endpoint: LC CNR vs. dorsal pontine reference tissue.

Covariates: Age (non-linear), sex, scanner/coil, signal-to-noise ratio, voxel size, head motion.

Power: Pilot (n ≈ 20/group) for variance estimation; main study powered for medium effect (d ≈ 0.5), α = 0.05 two-sided.

Status: Neuromelanin-sensitive MRI is established for LC visualisation (Betts et al., 2019, pp. 2558–2571; Priovoulos et al., 2018, pp. 427–436); application to ME/CFS would be novel.

Acquisition, QC, preprocessing and reporting will conform to COBIDAS-MRI recommendations; protocol deviations will be documented a priori.

6.2. NET-PET Imaging

Prediction: NET binding potential (BPND) will be reduced in the LC region in ME/CFS and will correlate with hypervigilance symptoms and fatigue severity.

Protocol: Primary radioligand: [11C]MeNER; 90-minute dynamic acquisition; arterial input function or reference tissue model (occipital cortex); geometric transfer matrix partial volume correction for LC region-of-interest.

Covariates: Endogenous NE levels, medications (SNRIs, atomoxetine, TCAs, beta-blockers—with appropriate washout), smoking status, age, sex.

Interpretive note: Reduced NET binding can reflect transporter density, endogenous occupancy, or partial-volume effects. Converging evidence from neuromelanin MRI, CSF markers, and physiology is essential (Pietrzak et al., 2013, pp. 1199–1205).

PET procedures (acquisition, kinetic modelling, PVC and reporting) will follow SNMMI procedure standards and QIBA guidance for neuroreceptor studies; ligand- and site-specific parameters will be preregistered (OSF).

6.3. CSF Metabolite Profiling

Prediction: Paradoxically low MHPG (principal NE metabolite) despite presumed high neuronal activity; elevated oxidative stress markers (GSH/GSSG ratio, 8-iso-PGF2α); elevated inflammatory markers.

Design: ME/CFS (n ≥ 30) vs. controls, with subgroup analysis by ACE score.

Pre-analytics: Lumbar puncture 08:00–10:00 to control circadian variation; polypropylene collection tubes; immediate centrifugation; aliquoting and storage at −80 °C; haemolysis exclusion. Robust regression with adjustment for multiple comparisons (Shungu et al., 2012, pp. 1073–1087).

Pre-analytics and reporting will follow STROBE and BRISQ principles; site-level SOPs will be preregistered (OSF) before enrolment.

6.4. Physiological Measures (HRV, Pupillometry)

Prediction: HRV parameters (RMSSD, SDNN, LF/HF ratio) will show reduced parasympathetic indices; pupillometry will show reduced pupillary light reflex amplitude and altered spontaneous fluctuations (Murphy et al., 2014, pp. 4140–4154; Joshi et al., 2016, pp. 221–234). These will correlate with functional capacity and ACE score.

Protocol: HRV: 5-minute seated rest followed by 5-minute standing; ECG sampling ≥250 Hz; exclusion of significant arrhythmias; time-domain (RMSSD, SDNN) and frequency-domain (LF, HF, LF/HF) analysis. Pupillometry: infrared eye-tracking; baseline diameter, light reflex amplitude, latency, and return-to-baseline time; spontaneous pupil fluctuation index. Test-retest reliability reported as intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Primary: correlation with SF-36 and PEM intensity.

HRV acquisition and analysis will follow the Task Force recommendations; pupillometry procedures and reporting will be standardised and preregistered (OSF).

6.5. Pharmacological Differentiation (N-of-1 Trials)

Rationale: To differentiate substrate-limited from receptor-limited states.

Design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled N-of-1 crossover with placebo run-in (2 weeks); comparing atomoxetine (blocks reuptake, does not force release), modafinil (DAT/NET blocker), and, if ethically justified, low-dose stimulant (forces release). Washout periods: minimum 5–7 half-lives between conditions.

Prediction: Atomoxetine/modafinil produce modest effect (substrate-limited); stimulant produces initial effect followed by tolerance (empties limited stores).

Safety: Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) required; predefined stopping criteria (cardiovascular events, severe psychiatric symptoms); ECG, blood pressure, sleep quality, and anxiety monitoring at each visit; preregistration on OSF/ClinicalTrials.gov. Such studies require careful ethical review.

Reporting will follow the CONSORT Extension for N-of-1 Trials (CENT 2015); blinding, washouts and stopping rules will be preregistered (OSF) prior to enrolment.

6.6. Prospective ACE-ME/CFS Cohort

Design: Large general population cohort (n ≥ 10,000); ACE assessment (CTQ) at baseline with biomarkers (HRV, inflammatory markers); long-term follow-up (10+ years); ME/CFS incidence documented per IOM/NICE criteria with infectious trigger documentation.

Prediction: Dose-response relationship—each additional ACE increases ME/CFS risk; mediation/moderation by HPA axis function and HRV; competing risks analysis.

Observational reporting will follow STROBE; analysis plans and amendments will be preregistered (OSF) before database lock.

7. Potential Disconfirming Evidence

The model should be abandoned or substantially revised if: (1) LC neuromelanin imaging shows no abnormalities in ME/CFS vs. controls; (2) CSF MHPG is normal or elevated rather than low; (3) HRV/pupillometry show no correlation with symptoms or ACE scores; (4) pharmacological probe trials show inconsistent patterns not matching substrate-limitation predictions; (5) mitochondrial support interventions show no benefit in appropriately powered trials; (6) prospective cohort shows no ACE dose-response relationship with ME/CFS incidence.

8. Discussion

8.1. Strengths

The proposed framework: (1) integrates disparate observations (ACE epidemiology, clinical phenomenology, autonomic dysfunction, sleep pathology); (2) is mechanistically specific, proposing a concrete pathway rather than vague ‘stress causes illness’; (3) generates testable predictions across imaging, CSF, physiology, and pharmacology; (4) explains heterogeneity through the two-hit model; (5) has translational potential if validated.

8.2. Weaknesses

(1) Evidence is indirect—no direct measurement of LC vesicular NE in humans exists. (2) ACE ascertainment involves retrospective reporting bias. (3) Pharmacological observations regarding tolerance are anecdotal. (4) Conference data are preliminary. (5) Causality is unclear and likely bidirectional. (6) The model may be incomplete.

8.3. Implications if Hypothesis Is Correct

For understanding ME/CFS: Shift from ‘mysterious post-viral syndrome’ to mechanistic model with identifiable vulnerability factors; explains why a subset of patients have ACE histories and high achievement orientation phenotypes; explains delayed onset and refractoriness. For research: Provides concrete targets, stratification strategies, and surrogate markers. For patients: Validates experiences (symptoms have neurobiological substrate); removes stigma. However: No immediate therapeutic implications; research must precede any clinical application.

9. Conclusions

We have proposed a specific, testable hypothesis: ME/CFS in a subset of patients results from chronic norepinephrine depletion of the locus coeruleus, programmed by adverse childhood experiences and triggered by acute systemic stressors. The hypothesis integrates ACE epidemiology, LC vulnerability to chronic stress, mitochondrial and vesicular mechanisms, glymphatic dysfunction, clinical phenomenology, and preliminary pharmacological observations.

It generates specific predictions testable through neuroimaging, CSF profiling, physiological surrogates, pharmacological probes, and prospective epidemiology. Most importantly, this is a hypothesis, not established fact. It requires rigorous testing. Until evidence exists, no therapeutic conclusions should be drawn. We present this framework to stimulate discussion and guide research.

Funding

No external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has clinical experience with body-based trauma therapies (Somatic Experiencing, Hakomi) and systemic work with ME/CFS patients, which informed this hypothesis. No proprietary methods are promoted. All therapeutic approaches discussed are well-established techniques requiring validation through controlled research. The author has no relationships with the pharmaceutical industry.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks colleagues who shared clinical observations and ME/CFS patients who shared their experiences.

Data Availability

Not applicable (conceptual hypothesis paper). Preregistration of proposed studies is intended.

Ethics

No human participants/data are included in this manuscript. The study plans are intended for institutional adoption; site-specific OSF preregistration and local IRB approval will precede any data collection.

Abbreviations

ACE, adverse childhood experience; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; BPND, non-displaceable binding potential; BRISQ, Biospecimen Reporting for Improved Study Quality; CENT, CONSORT Extension for N-of-1 Trials; COBIDAS, Committee on Best Practices in Data Analysis and Sharing (MRI); CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; CNR, contrast-to-noise ratio; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; DAT, dopamine transporter; DBH, dopamine-β-hydroxylase; DSMB, Data Safety Monitoring Board; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; ECG, electrocardiogram; GTM, geometric transfer matrix; HF, high-frequency power; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; HRV, heart rate variability; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; IOM, Institute of Medicine; IRB, Institutional Review Board; LC, locus coeruleus; LF, low-frequency power; ME/CFS, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; MHPG, 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NE, norepinephrine; NET, norepinephrine transporter; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NREM, non-rapid eye movement; OSF, Open Science Framework; PEM, post-exertional malaise; PET, positron emission tomography; POTS, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; PVC, partial volume correction; QIBA, Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance; RMSSD, root mean square of successive differences; ROI, region of interest; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SDNN, standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals; SFN, small fibre neuropathy; SNMMI, Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; STROBE, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; V-ATPase, vacuolar-type ATPase; VMAT, vesicular monoamine transporter.

References

- Aston-Jones, G. and Cohen, J.D. (2005) ‘An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance’, Annual Review of Neuroscience, 28, pp. 403–450.

- Bangasser, D.A. and Valentino, R.J. (2020) ‘The locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in stress and arousal: unraveling historical, current, and future perspectives’, Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, p. 601519.

- Baumeister, D., Akhtar, R., Ciufolini, S., Pariante, C.M. and Mondelli, V. (2016) ‘Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: a meta-analysis’, Molecular Psychiatry, 21(5), pp. 642–649.

- Betts, M.J., Kirilina, E., Otaduy, M.C.G., et al. (2019) ‘Locus coeruleus imaging as a biomarker for noradrenergic dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases’, Brain, 142(9), pp. 2558–2571. 9.

- Blockmans, D., Persoons, P., Van Houdenhove, B. and Bobbaers, H. (2006) ‘Does methylphenidate reduce the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome?’, The American Journal of Medicine, 119(12), pp. 1047–1053.

- Bunea, I.M., Szentágotai-Tătar, A. and Miu, A.C. (2017) ‘Early-life adversity and cortisol response to social stress: a meta-analysis’, Translational Psychiatry, 7(12), p. 1274.

- Da Silva, J.P. et al. (2025) ‘Delineating clinical phenotypes and HPA-axis dysfunction in ME/CFS’, presented at IACFS/ME 2025 Conference [conference abstract—not peer-reviewed].

- Edwards, R.H. (2007) ‘The neurotransmitter cycle and quantal size’, Neuron, 55(6), pp. 835–849.

- Eiden, L.E. and Weihe, E. (2011) ‘VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1216, pp. 86–98.

- Felitti, V.J., Anda, R.F., Nordenberg, D., et al. (1998) ‘Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), pp. 245–258.

- Goldstein, D.S. and Aregawi, D. (2025) ‘Low brain norepinephrine in ME/CFS’, presented at IACFS/ME 2025 Conference [conference abstract—not peer-reviewed].

- Hauglund, N.L., Andersen, M., Tokarska, K., et al. (2025) ‘Norepinephrine-mediated slow vasomotion drives glymphatic clearance during sleep’, Cell, 188(3), pp. 606–622. [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, J. et al. (2025) ‘Sympathetic dysfunction in ME/CFS: a meta-analysis’, presented at IACFS/ME 2025 Conference [conference abstract—not peer-reviewed].

- Joshi, S., Li, Y., Kalwani, R.M. and Gold, J.I. (2016) ‘Relationships between pupil diameter and neuronal activity in the locus coeruleus, colliculi, and cingulate cortex’, Neuron, 89(1), pp. 221–234.

- Kempke, S., Luyten, P., Claes, S., et al. (2013) ‘Self-critical perfectionism and fatigue and pain in chronic fatigue syndrome’, Psychological Medicine, 43(5), pp. 995–1002.

- Komaroff, A.L. and Lipkin, W.I. (2021) ‘Insights from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome may help unravel the pathogenesis of postacute COVID-19 syndrome’, Trends in Molecular Medicine, 27(9), pp. 895–906.

- McGowan, P.O., Sasaki, A., D’Alessio, A.C., et al. (2009) ‘Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse’, Nature Neuroscience, 12(3), pp. 342–348.

- Murphy, P.R., O’Connell, R.G., O’Sullivan, M., Robertson, I.H. and Balsters, J.H. (2014) ‘Pupil diameter covaries with BOLD activity in human locus coeruleus’, Human Brain Mapping, 35(8), pp. 4140–4154.

- Nakatomi, Y., Mizuno, K., Ishii, A., et al. (2014) ‘Neuroinflammation in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: an [11C-(R)]PK11195 PET study’, Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 55(6), pp. 945–950.

- Naviaux, R.K., Naviaux, J.C., Li, K., et al. (2016) ‘Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 113(37), pp. E5472–E5480.

- Nedergaard, M. (2013) ‘Garbage truck of the brain’, Science, 340(6140), pp. 1529–1530.

- Nelson, M.J., Bahl, J.S., Buckley, J.D., Thomson, R.L. and Davison, K. (2019) ‘Evidence of altered cardiac autonomic regulation in ME/CFS: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Medicine, 98(43), p. e17600.

- Perroud, N., Paoloni-Giacobino, A., Prada, P., et al. (2011) ‘Increased methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) in adults with a history of childhood maltreatment’, Translational Psychiatry, 1(12), p. e59.

- Pietrzak, R.H., Gallezot, J.D., Ding, Y.S., et al. (2013) ‘Association of PTSD with reduced in vivo norepinephrine transporter availability in the locus coeruleus’, JAMA Psychiatry, 70(11), pp. 1199–1205.

- Priovoulos, N., Jacobs, H.I.L., Ivanov, D., Uludağ, K., Verhey, F.R.J. and Poser, B.A. (2018) ‘High-resolution in vivo imaging of human locus coeruleus by magnetization transfer MRI at 3T and 7T’, NeuroImage, 168, pp. 427–436.

- Schwarz, L.A. and Luo, L. (2015) ‘Organization of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system’, Current Biology, 25(21), pp. R1051–R1056.

- Shungu, D.C., Weiduschat, N., Murrough, J.W., et al. (2012) ‘Increased ventricular lactate in chronic fatigue syndrome. III. Relationships to cortical glutathione and clinical symptoms’, NMR in Biomedicine, 25(9), pp. 1073–1087.

- Valentino, R.J. and Van Bockstaele, E. (2008) ‘Convergent regulation of locus coeruleus activity as an adaptive response to stress’, European Journal of Pharmacology, 583(2–3), pp. 194–203.

- van Campen, C.L.M.C., Rowe, P.C. and Visser, F.C. (2020) ‘Cerebral blood flow is reduced in severe ME/CFS patients during mild orthostatic stress testing’, Healthcare, 8(2), p. 169.

- Van Houdenhove, B., Neerinckx, E., Lysens, R., et al. (2001) ‘Victimization in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia in tertiary care’, Psychosomatics, 42(1), pp. 21–28.

- Wirth, K. and Scheibenbogen, C. (2020) ‘A unifying hypothesis of the pathophysiology of ME/CFS: insights from autoantibodies against β2-adrenergic receptors’, Autoimmunity Reviews, 19(6), p. 102527.

- Xie, L., Kang, H., Xu, Q., et al. (2013) ‘Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain’, Science, 342(6156), pp. 373–377. [CrossRef]

- Young, J.L. (2013) ‘Use of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in treatment of executive functioning deficits and chronic fatigue syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study’, Psychiatry Research, 207(1–2), pp. 127–133.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).