Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

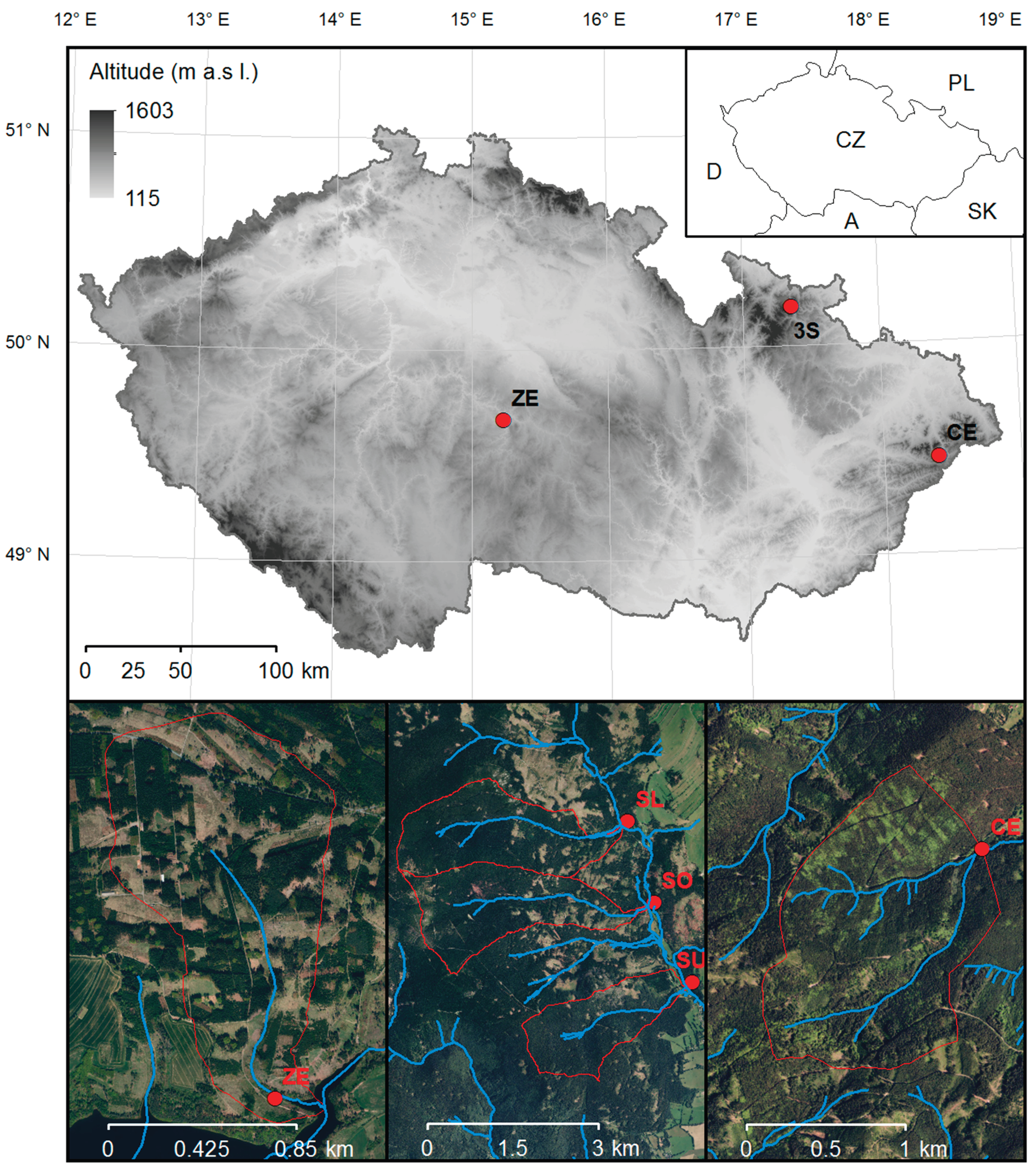

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Identification of Clear-Cut Areas

2.3. Sampling of Atmospheric Deposition and Stream Water; Analytical Methods

2.4. Hydrological Data

2.5. Elemental Budgets of the Catchments

2.6. Statistical Methods

2.6.1. Compositional Data Analysis (CoDa)

2.6.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on Isometric Log-Ratio (Ilr) Transformed Data

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Clear-Cuts

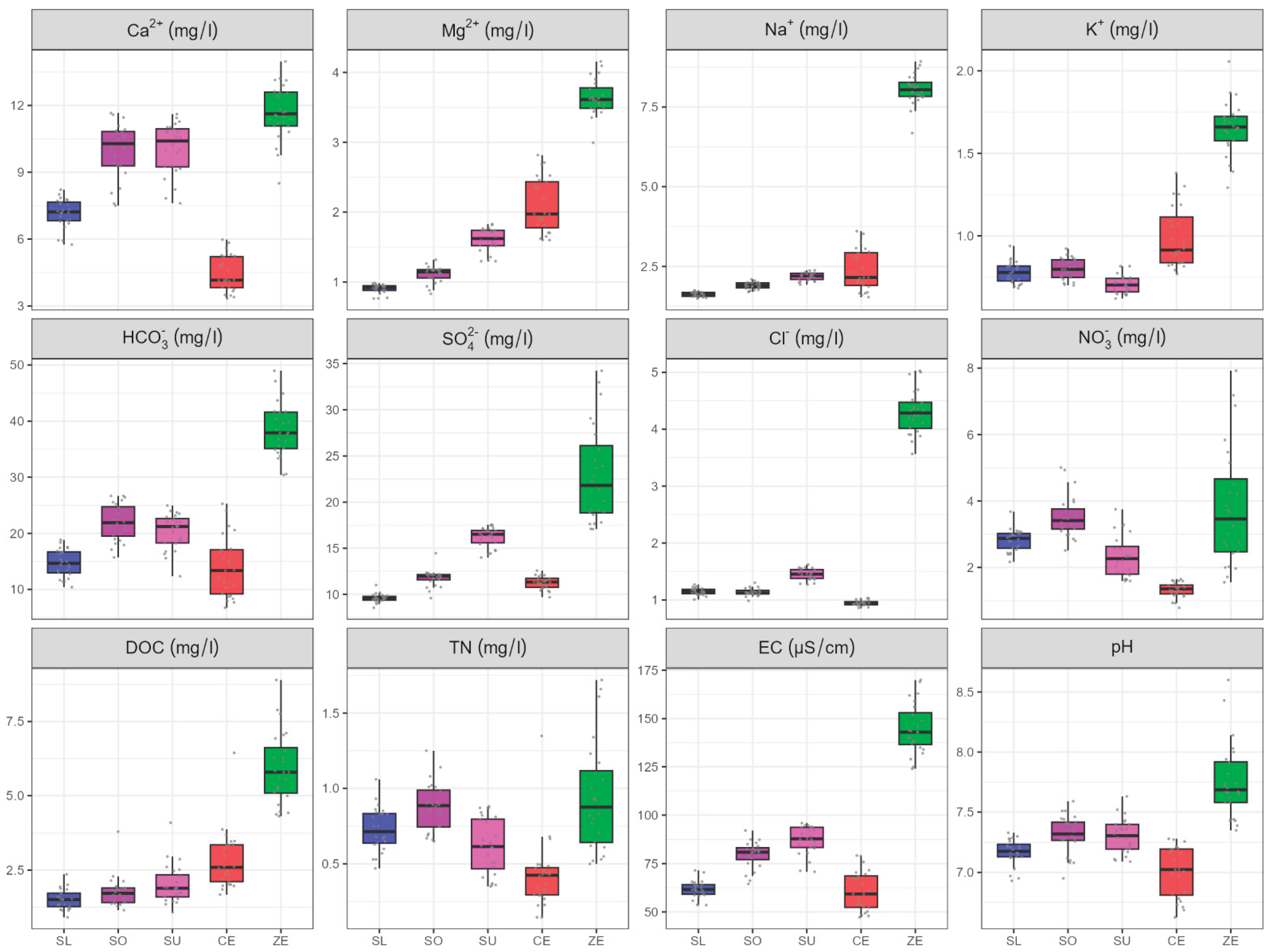

3.2. Precipitation and Stream Water Chemistry

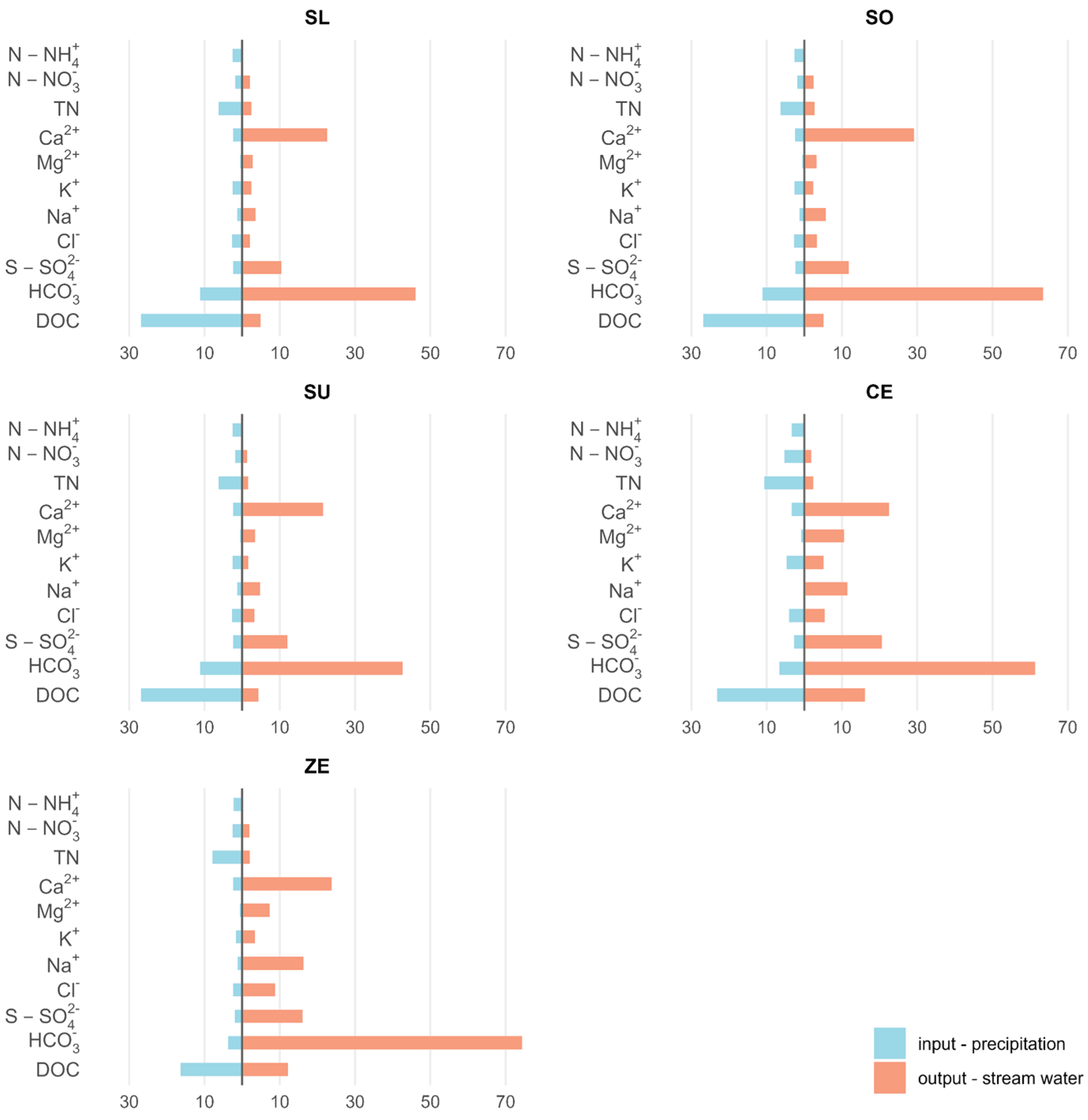

3.3. Retention and Export of Elements

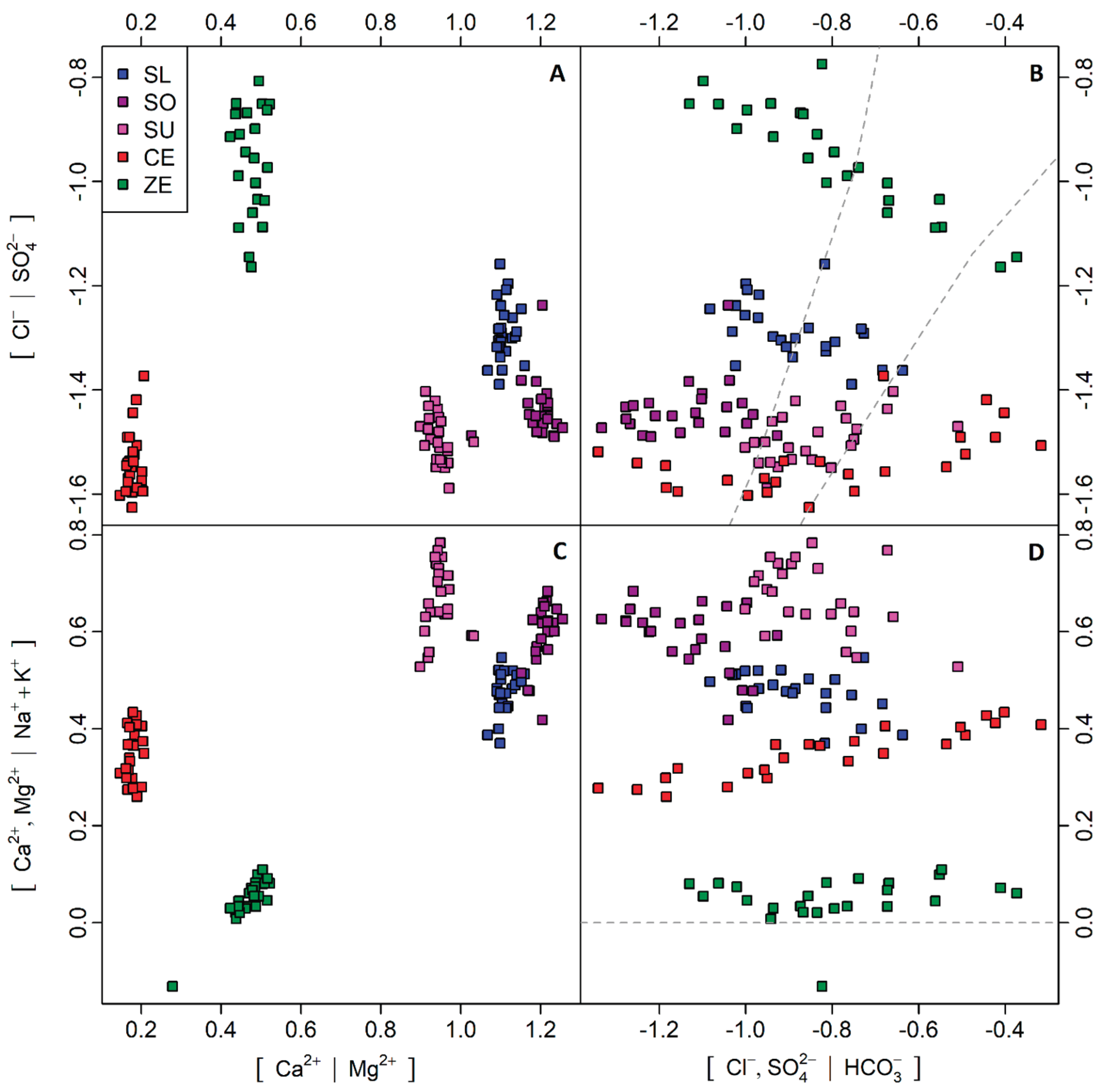

3.4. Hydrochemical Characteristics of Catchments

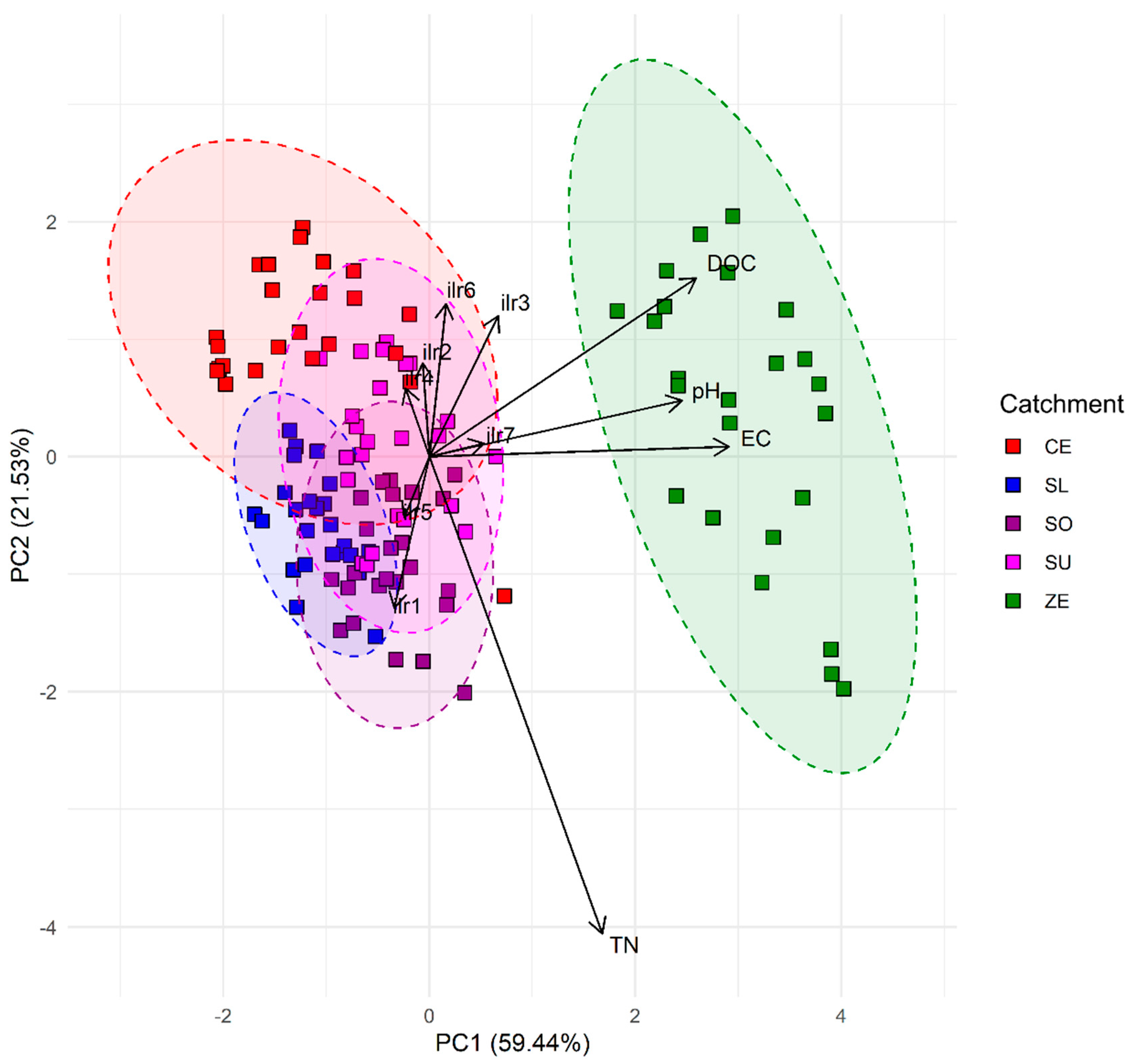

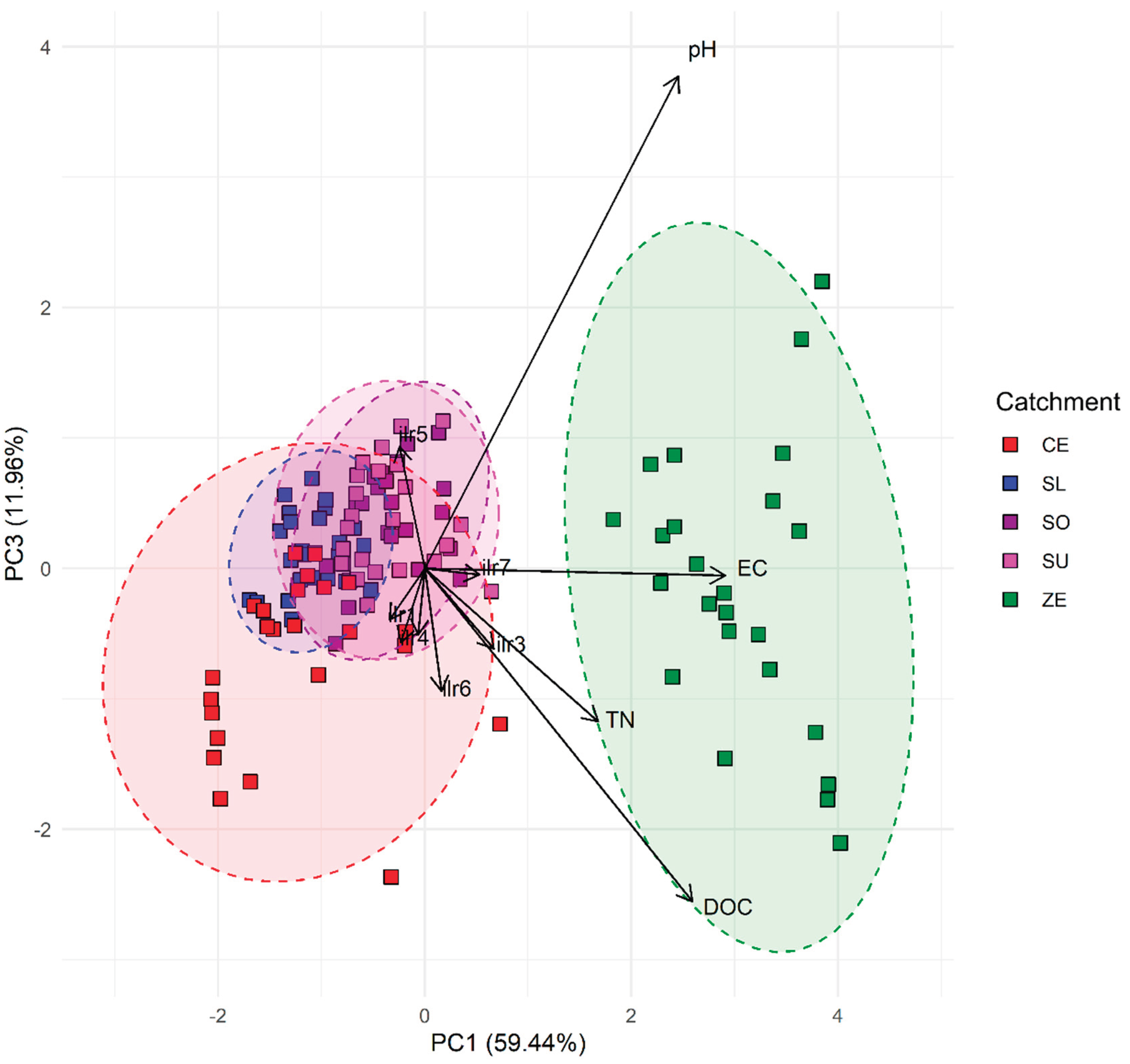

3.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

4.1. Atmospheric Deposition

4.2. Disturbance Effect on Runoff Chemistry

4.3. The Dominant Role of Geology in Individual Catchments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, M.; Wei, X. Deforestation, Forestation, and Water Supply. Science 2021, 371, 990–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filoso, S.; Bezerra, M.O.; Weiss, K.C.B.; Palmer, M.A. Impacts of Forest Restoration on Water Yield: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho-Santos, C.; Honrado, J.P.; Hein, L. Hydrological Services and the Role of Forests: Conceptualization and Indicator-Based Analysis with an Illustration at a Regional Scale. Ecological Complexity 2014, 20, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, D. Long-Term Forest Paired Catchment Studies: What Do They Tell Us That Landscape-Level Monitoring Does Not? Forests 2016, 7, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, P.V.; Martin, K.L.; Vose, J.M.; Baker, J.S.; Warziniack, T.W.; Costanza, J.K.; Frey, G.E.; Nehra, A.; Mihiar, C.M. Forested Watersheds Provide the Highest Water Quality among All Land Cover Types, but the Benefit of This Ecosystem Service Depends on Landscape Context. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 882, 163550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, P.; Ellison, D.; Ferraz, S.F.D.B.; Filoso, S.; Brancalion, P.H.S. On the Unique Value of Forests for Water: Hydrologic Impacts of Forest Disturbances, Conversion, and Restoration. Global Change Biology 2024, 30, e17162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, J.; Tulcan, R.X.S.; Zhu, W. The Neglected Role of Forest Eco-Hydrological Process Representation in Regulating Watershed Nitrogen Loss. Water Research 2025, 282, 123735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, F.J.; Vásquez-Lavín, F.; Ponce, R.D.; Garreaud, R.; Hernández, F.; Link, O.; Zambrano, F.; Hanemann, M. The Economics Impacts of Long-Run Droughts: Challenges, Gaps, and Way Forward. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 344, 118726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szejner, P.; Belmecheri, S.; Ehleringer, J.R.; Monson, R.K. Recent Increases in Drought Frequency Cause Observed Multi-Year Drought Legacies in the Tree Rings of Semi-Arid Forests. Oecologia 2020, 192, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinoni, J.; Vogt, J.V.; Naumann, G.; Barbosa, P.; Dosio, A. Will Drought Events Become More Frequent and Severe in Europe? Intl Journal of Climatology 2018, 38, 1718–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieger, S.; Kappas, M.; Karel, S.; Koal, P.; Koukal, T.; Löw, M.; Zwanzig, M.; Putzenlechner, B. Impact of Forest Disturbance Derived from Sentinel-2 Time Series on Landsat 8/9 Land Surface Temperature: The Case of Norway Spruce in Central Germany. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2025, 228, 388–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukh, S.; Sanders, T.G.M.; Krüger, I.; Schad, T.; Bolte, A. Distinct Responses of European Beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.) to Drought Intensity and Length—A Review of the Impacts of the 2003 and 2018–2019 Drought Events in Central Europe. Forests 2023, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuldt, B.; Buras, A.; Arend, M.; Vitasse, Y.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; Damm, A.; Gharun, M.; Grams, T.E.E.; Hauck, M.; Hajek, P.; et al. A First Assessment of the Impact of the Extreme 2018 Summer Drought on Central European Forests. Basic and Applied Ecology 2020, 45, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, P. Monitoring of Bark Beetle Forest Damages. In Big Data in Bioeconomy; Södergård, C., Mildorf, T., Habyarimana, E., Berre, A.J., Fernandes, J.A., Zinke-Wehlmann, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 351–361. ISBN 978-3-030-71068-2. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K.; Baldo, M.; Dobor, L.; Seidl, R.; Rammer, W.; Modlinger, R.; Washaya, P.; Merganičová, K.; Hlásny, T. The Increasing Role of Drought as an Inciting Factor of Bark Beetle Outbreaks Can Cause Large-Scale Transformation of Central European Forests. Landsc Ecol 2025, 40, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brázdil, R.; Zahradník, P.; Szabó, P.; Chromá, K.; Dobrovolný, P.; Dolák, L.; Trnka, M.; Řehoř, J.; Suchánková, S. Meteorological and Climatological Triggers of Notable Past and Present Bark Beetle Outbreaks in the Czech Republic. Clim. Past 2022, 18, 2155–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlásny, T.; König, L.; Krokene, P.; Lindner, M.; Montagné-Huck, C.; Müller, J.; Qin, H.; Raffa, K.F.; Schelhaas, M.-J.; Svoboda, M.; et al. Bark Beetle Outbreaks in Europe: State of Knowledge and Ways Forward for Management. Curr Forestry Rep 2021, 7, 138–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahradník, P.; Zahradníková, M. Salvage Felling in the Czech Republic‘s Forests during the Last Twenty Years. Central European Forestry Journal 2019, 65, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubojacký, J.; Véle, A.; Samek, M.; Lorenc, F.; Knížek, M. Hlavní Problémy v Ochraně Lesa v Česku v Roce 2024 a Prognóza Na Rok 2025. In Proceedings of the Škodliví činitelé v lesích Česka 2024/2025, Ochrana lesa a ochrana přírody; Lorenc, F., Véle, A., Knížek, M., Eds.; Zpravodaj ochrany lesa: Průhonice, 2025; Volume 28, pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Křístek, Š.; Apltauer, J.; Dušek, D.; Kačmařík, V.; Leugner, Jan; Mlčoušek, Marek; Pařízková, Alžběta; Souček, Jiří; Špulák, Ondřej; Válek, Miroslav. Generel Obnovy Lesních Porostů Po Kalamitě 2024.

- Thonfeld, F.; Gessner, U.; Holzwarth, S.; Kriese, J.; Da Ponte, E.; Huth, J.; Kuenzer, C. A First Assessment of Canopy Cover Loss in Germany’s Forests after the 2018–2020 Drought Years. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallas, T.; Steyrer, G.; Laaha, G.; Hoch, G. Two Unprecedented Outbreaks of the European Spruce Bark Beetle, Ips Typographus L. (Col., Scolytinae) in Austria since 2015: Different Causes and Different Impacts on Forests. Central European Forestry Journal 2024, 70, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.; Apoznański, G.; Dobrowolska, D.; Rachwald, A. Outbreaks of European Spruce Bark Beetle Dramatically Altered Norway Spruce-Dominated Stands with Implications for Volant Wildlife in the Białowieża Forest, Poland. Annals of Forest Science 2025, 82, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starck, I.; Aalto, J.; Hancock, S.; Valkonen, S.; Kalliovirta, L.; Maeda, E. Slow Recovery of Microclimate Temperature Buffering Capacity after Clear-Cuts in Boreal Forests. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2025, 363, 110434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falťan, V.; Petrovič, F.; Gábor, M.; Šagát, V.; Hruška, M. Mountain Landscape Dynamics after Large Wind and Bark Beetle Disasters and Subsequent Logging—Case Studies from the Carpathians. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaniz, A.J.; Abarzúa, A.M.; Martel-Cea, A.; Jarpa, L.; Hernández, M.; Aquino-López, M.A.; Smith-Ramírez, C. Linking Sedimentological and Spatial Analysis to Assess the Impact of the Forestry Industry on Soil Loss: The Case of Lanalhue Basin, Chile. CATENA 2021, 207, 105660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbitz, K.; Glaser, B.; Bol, R. Clear-cutting of a Norway Spruce Stand: Implications for Controls on the Dynamics of Dissolved Organic Matter in the Forest Floor. European J Soil Science 2004, 55, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerabkova, L.; Prescott, C.E. Post-Harvest Soil Nitrate Dynamics in Aspen- and Spruce-Dominated Boreal Forests. Forest Ecology and Management 2007, 242, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraškiene, M.; Varnagiryte-Kabašinskiene, I.; Stakenas, V. The Effect of Clear-Cut Age on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Indices in Scots Pine (Pinus Sylvestris L.) Stands. iForest 2025, 18, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blixt, T.; Bergman, K.-O.; Milberg, P.; Westerberg, L.; Jonason, D. Clear-Cuts in Production Forests: From Matrix to Neo-Habitat for Butterflies. Acta Oecologica 2015, 69, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-J.; Eo, S.H. Comparison of Soil Bacterial Diversity and Community Composition between Clear-Cut Logging and Control Sites in a Temperate Deciduous Broad-Leaved Forest in Mt. Sambong, South Korea. J. For. Res. 2020, 31, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustienė, D.; Varnagirytė-Kabašinskienė, I. Changes in Ground Cover Layers, Biomass and Diversity of Vascular Plants/Mosses in the Clear-Cuts Followed by Reforested Scots Pine until Maturity Age. Land 2024, 13, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centenaro, G.; de-Miguel, S.; Bonet, J.A.; Martínez Peña, F.; De Gomez, R.E.G.; Ponce, Á.; Dashevskaya, S.; Alday, J.G. Spatially-Explicit Effects of Small-Scale Clear-Cutting on Soil Fungal Communities in Pinus Sylvestris Stands. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 909, 168628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schelker, J.; Kuglerová, L.; Eklöf, K.; Bishop, K.; Laudon, H. Hydrological Effects of Clear-Cutting in a Boreal Forest – Snowpack Dynamics, Snowmelt and Streamflow Responses. Journal of Hydrology 2013, 484, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Giles-Hansen, K.; Spencer, S.A.; Ge, X.; Onuchin, A.; Li, Q.; Burenina, T.; Ilintsev, A.; Hou, Y. Forest Harvesting and Hydrology in Boreal Forests: Under an Increased and Cumulative Disturbance Context. Forest Ecology and Management 2022, 522, 120468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P.M.; Gosz, J.R.; Grier, C.C.; Melillo, J.M.; Reiners, W.A.; Todd, R.L. Nitrate Losses from Disturbed Ecosystems: Interregional Comparative Studies Show Mechanisms Underlying Forest Ecosystem Response to Disturbance. Science 1979, 204, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulehle, F.; Wright, R.F.; Svoboda, M.; Bače, R.; Matějka, K.; Kaňa, J.; Hruška, J.; Couture, R.-M.; Kopáček, J. Effects of Bark Beetle Disturbance on Soil Nutrient Retention and Lake Chemistry in Glacial Catchment. Ecosystems 2019, 22, 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.I.; Hejzlar, J.; Kopáček, J.; Paule-Mercado, Ma.C.; Porcal, P.; Vystavna, Y.; Lanta, V. Forest Damage and Subsequent Recovery Alter the Water Composition in Mountain Lake Catchments. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 827, 154293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vystavna, Y.; Paule-Mercado, M.C.; Schmidt, S.I.; Hejzlar, J.; Porcal, P.; Matiatos, I. Nutrient Dynamics in Temperate European Catchments of Different Land Use under Changing Climate. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2023, 45, 101288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unucka, J.; Adamecínský, M.; Pavlíková, I.; Špulák, O.; Šrámek, V.; Hellebrandová, K. Measurement and Modelling of Changes in the Runoff Regime Following Calamitous Decay and Regeneration of Forest Stands in Small Catchments in the Jeseníky Mountains. VTEI 2025, 67, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šrámek, V.; Fadrhonsová, V.; Neudertová Hellebrandová, K. Rainfall Variability in the Mountain Forest Catchments of Černá Opava Tributaries in the Jeseníky Mountains. J. For. Sci. 2025, 71, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vondráková, A.; Vávra, A.; Voženílek, V. Climatic Regions of the Czech Republic. Journal of Maps 2013, 9, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochman, V.; Maxa, M.; Bíba, M. Development of soil chemistry on FGMRI research plots during reduction of air pollution fallout. Reports of Forestry Research - Zprávy Lesnického Výzkumu 2006, 51, 106–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bíba, M.; Vícha, Z.; Janová, K.; Jařabáč, M. Forest regeneration in experimental catchment Červík and its influence on run-off process. Reports of Forestry Research - Zprávy Lesnického Výzkumu 2010, 55, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, N.; Žlindra, D.; Erwin, U.; Mosello, R.; Derome, J.; Derome, K.; König, N.; Geppert, F.; Lövblad, G.; Draaijers, G.P.J.; et al. Part XIV: Sampling and Analysis of Deposition. In Manual on methods and criteria for harmonized sampling, assessment, monitoring and analysis of the effects of air pollution on forests; Thünen Institute of Forest Ecosystems: Eberswalde, Germany, 2022; p. 34 p. [Google Scholar]

- Green, I.R.A. An Explicit Solution of the Modified Horton Equation. Journal of Hydrology 1986, 83, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2024.

- Greenacre, M. Compositional Data Analysis in Practice, 0 ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018; ISBN 978-0-429-45553-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, J.L.; Engle, M.A.; Buccianti, A.; Blondes, M.S. The Isometric Log-Ratio (Ilr)-Ion Plot: A Proposed Alternative to the Piper Diagram. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2018, 190, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, S.; Henry, T.; Murray, J.; Flood, R.; Muller, M.R.; Jones, A.G.; Rath, V. Compositional Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Thermal Groundwater Provenance: A Hydrogeochemical Case Study from Ireland. Applied Geochemistry 2016, 75, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmalek, D.; Azzeddine, R.; Mohamed, A.; Faouzi, Z.; Galal, W.F.; Alarifi, S.S.; Mohammed, M.A.A. Groundwater Quality Assessment Using Revised Classical Diagrams and Compositional Data Analysis (CoDa): Case Study of Wadi Ranyah, Saudi Arabia. Journal of King Saud University - Science 2024, 36, 103463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzeddine, R.; Abdelmalek, D.; Ewuzie, U.; Faouzi, Z.; Taha-Hocine, D. Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) and Geochemical Signatures of the Terminal Complex Aquifer in an Arid Zone (Northeastern Algeria). Journal of African Earth Sciences 2024, 210, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Kim, K.-H.; Kim, H.-R.; Park, S.; Yun, S.-T. Using Isometric Log-Ratio in Compositional Data Analysis for Developing a Groundwater Pollution Index. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 12196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitchison, J. The Statistical Analysis of Compositional Data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 1982, 44, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egozcue, J.J.; Pawlowsky-Glahn, V.; Mateu-Figueras, G.; Barceló-Vidal, C. Isometric Logratio Transformations for Compositional Data Analysis. Mathematical Geology 2003, 35, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewuzie, U.; Nnorom, I.C.; Ugbogu, O.; Onwuka, C.V. Hydrogeochemical, Microbial and Compositional Analysis of Data from Surface and Groundwater Sources in Southeastern Nigeria. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2021, 224, 106737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, M.A.; Rowan, E.L. Geochemical Evolution of Produced Waters from Hydraulic Fracturing of the Marcellus Shale, Northern Appalachian Basin: A Multivariate Compositional Data Analysis Approach. International Journal of Coal Geology 2014, 126, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Boogaart, K.G.; Tolosana-Delgado, R. Analyzing Compositional Data with R; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; ISBN 978-3-642-36808-0. [Google Scholar]

- Campodonico, V.A.; Pasquini, A.I.; Lecomte, K.L.; Alvarez, B.Y.; García, M.G. Hydrochemistry and Surface Water - Groundwater Interactions in an Anthropically Disturbed Mountain River (Sierras Pampeanas, Central Argentina). Journal of South American Earth Sciences 2024, 150, 105251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, W.; Van Der Salm, C.; Reinds, G.J.; Erisman, J.W. Element Fluxes through European Forest Ecosystems and Their Relationships with Stand and Site Characteristics. Environmental Pollution 2007, 148, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopáček, J.; Hejzlar, J.; Porcal, P.; Posch, M. Trends in Riverine Element Fluxes: A Chronicle of Regional Socio-Economic Changes. Water Research 2017, 125, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hůnová, I.; Maznová, J.; Kurfürst, P. Trends in Atmospheric Deposition Fluxes of Sulphur and Nitrogen in Czech Forests. Environmental Pollution 2014, 184, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hůnová, I. Ambient Air Quality in the Czech Republic: Past and Present. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogora, M.; Marchetto, A.; Mosello, R. Trends in the Chemistry of Atmospheric Deposition and Surface Waters in the Lake Maggiore Catchment. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2001, 5, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorenmaa, J.; Augustaitis, A.; Beudert, B.; Bochenek, W.; Clarke, N.; De Wit, H.A.; Dirnböck, T.; Frey, J.; Hakola, H.; Kleemola, S.; et al. Long-Term Changes (1990–2015) in the Atmospheric Deposition and Runoff Water Chemistry of Sulphate, Inorganic Nitrogen and Acidity for Forested Catchments in Europe in Relation to Changes in Emissions and Hydrometeorological Conditions. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 625, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaste, Ø.; Austnes, K.; De Wit, H.A. Streamwater Responses to Reduced Nitrogen Deposition at Four Small Upland Catchments in Norway. Ambio 2020, 49, 1759–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, G.M.; Lindberg, S.E. Dry Deposition and Canopy Exchange in a Mixed Oak Forest as Determined by Analysis of Throughfall. The Journal of Applied Ecology 1984, 21, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.J.; Likens, G.E. A Direct Comparison of Throughfall plus Stemflow to Estimates of Dry and Total Deposition for Sulfur and Nitrogen. Atmospheric Environment 1995, 29, 1253–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimonier, A.; Schmitt, M.; Waldner, P.; Rihm, B. Atmospheric Deposition on Swiss Long-Term Forest Ecosystem Research (LWF) Plots. Environ Monit Assess 2005, 104, 81–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hůnová, I.; Novák, M.; Kurfürst, P.; Škáchová, H.; Štěpánová, M.; Přechová, E.; Veselovský, F.; Čuřík, J.; Bohdálková, L.; Komárek, A. Comparison of Vertical and Horizontal Atmospheric Deposition of Nitrate at Central European Mountain-Top Sites during Three Consecutive Winters. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 869, 161697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musolff, A.; Tarasova, L.; Rinke, K.; Ledesma, J.L.J. Forest Dieback Alters Nutrient Pathways in a Temperate Headwater Catchment. Hydrological Processes 2024, 38, e15308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdálková, L.; Lamačová, A.; Hruška, J.; Svoboda, J.; Krám, P.; Oulehle, F. Impact of Environmental Disturbances on Hydrology and Nitrogen Cycling in Central European Forest Catchments. Biogeochemistry 2025, 168, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedwall, P.-O.; Bergh, J.; Nordin, A. Nitrogen-Retention Capacity in a Fertilized Forest after Clear-Cutting — the Effect of Forest-Floor Vegetation. Can. J. For. Res. 2015, 45, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochman, V. Vývoj zatížení lesních ekosystémů na povodí Pekelského potoka (objekt Želivka) a jeho vliv na změny v půdě a ve vodě povrchového zdroje. Lesnictví-Forestry 1997, 43, 529–546. [Google Scholar]

- Vícha, Z.; Lachmanová, Z.; Fadrhonsová, V.; Lochman, V.; Bíba, M. Air pollutants deposition development and their input into runoff water in the region of Bohemian-Moravian Highland. Reports of Forestry Research - Zprávy lesnického výzkumu 2013, 58, 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.; Thoss, V.; Watson, H. Factors Influencing the Release of Dissolved Organic Carbon and Dissolved Forms of Nitrogen from a Small Upland Headwater during Autumn Runoff Events. Hydrological Processes 2007, 21, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, G.; Dirnböck, T.; Grabner, M.-T.; Mirtl, M. Nitrogen Leaching of Two Forest Ecosystems in a Karst Watershed. Water Air Soil Pollut 2011, 218, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Finzi, A.C. Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics during Forest Stand Development: A Global Synthesis. New Phytologist 2011, 190, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, T.; Ohte, N.; Suzuki, M. Importance of Frequent Storm Flow Data for Evaluating Changes in Stream Water Chemistry Following Clear-Cutting in Japanese Headwater Catchments. Forest Ecology and Management 2011, 262, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swank, W.T. Long-Term Response of a Forest Watershed Ecosystem: Clearcutting in the Southern Appalachians; Long-Term Ecological Research Network Ser; Oxford University Press, Incorporated: New York, 2014; ISBN 978-0-19-970840-6. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, K.L.; Leach, J.A.; Hazlett, P.W.; Buttle, J.M.; Emilson, E.J.S.; Creed, I.F. Long-Term Stream Chemistry Response to Harvesting in a Northern Hardwood Forest Watershed Experiencing Environmental Change. Forest Ecology and Management 2022, 519, 120345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutzweiser, D.P.; Hazlett, P.W.; Gunn, J.M. Logging Impacts on the Biogeochemistry of Boreal Forest Soils and Nutrient Export to Aquatic Systems: A Review. Environ. Rev. 2008, 16, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelson, K.M.; Bearup, L.A.; Maxwell, R.M.; Stednick, J.D.; McCray, J.E.; Sharp, J.O. Bark Beetle Infestation Impacts on Nutrient Cycling, Water Quality and Interdependent Hydrological Effects. Biogeochemistry 2013, 115, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alewell, C.; Armbruster, M.; Bittersohl, J.; Evans, C.D.; Meesenburg, H.; Moritz, K.; Prechtel, A. Are There Signs of Acidification Reversal in Freshwaters of the Low Mountain Ranges in Germany? Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2001, 5, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajdak, M.; Siwek, J.P.; Wasak-Sęk, K.; Kosmowska, A.; Stańczyk, T.; Małek, S.; Żelazny, M.; Woźniak, G.; Jelonkiewicz, Ł.; Żelazny, M. Stream Water Chemistry Changes in Response to Deforestation of Variable Origin (Case Study from the Carpathians, Southern Poland). CATENA 2021, 202, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopáček, J.; Fluksová, H.; Hejzlar, J.; Kaňa, J.; Porcal, P.; Turek, J. Changes in Surface Water Chemistry Caused by Natural Forest Dieback in an Unmanaged Mountain Catchment. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 584–585, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, K.; Zhou, W.; Stober, I. Rocks control the chemical composition of surface water from the high Alpine Zermatt area (Swiss Alps). Swiss Journal of Geosciences 2017, 110, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krám, P.; Hruška, J.; Wenner, B.S.; Driscoll, C.T.; Johnson, C.E. Streamwater chemistry in three contrasting monolithologic Czech catchments. Applied Geochemistry 2012, 27, 1854–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosein, R.; Arn, K.; Steinmann, P.; Adatte, T.; Föllmi, K.B. Carbonate and silicate weathering in two presently glaciated, crystalline catchments in the Swiss Alps. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2004, 68, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, R.S.; Wörner, G.; Goldsmith, S.T.; Lyons, W.B.; Ogden, F.L.; Mitasova, H.; Kirby, C.S.; Asbury, R. Linking silicate weathering to riverine geochemistry—A case study from a mountainous tropical setting in west-central Panama. Geological Society of America Bulletin 2016, 128, 1780–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, M.; Andronikov, A.V.; Holmden, C.; Erban Kochergina, Y.V.; Veselovský, F.; Pačes, T.; Vítková, M.; Kachlík, V.; Šebek, O.; Hruška, J.; et al. δ26Mg, δ44Ca and 87Sr/86Sr Isotope Differences among Bedrock Minerals Constrain Runoff Generation in Headwater Catchments: An Acidified Granitic Site in Central Europe as an Example. CATENA 2023, 221, 106780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Holmden, C.; Farkas, J.; Andronikov, A.V.; Kram, P.; Hruska, J.; Curik, J.; Veselovsky, F.; Stepanova, M.; Prechova, E.; et al. Magnesium and calcium isotope systematics in a headwater catchment underlain by amphibolite: Constraints on Mg–Ca biogeochemistry in an atmospherically polluted but well-buffered spruce ecosystem (Czech Republic, Central Europe). Catena 2020, 194, 104637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stream | Slučí (SL) | Sokolí (SO) | Suchý (SU) | Červík (CE) | Pekelský (ZE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catchment area (km2) | 3.98 | 3.99 | 2.05 | 1.85 | 1.24 |

| Stream length (m) | 3436 | 3632 | 1680 | 5426 | 1671 |

| Minimum catchment elevation (m a.s.l.) | 649 | 614 | 646 | 505 | 374 |

| Maximum catchment elevation (m a.s.l.) | 1202 | 1215 | 1058 | 958 | 470 |

| Mean catchment elevation (m a.s.l.) | 914 | 919 | 892 | 696 | 445 |

| Forest area (km2)* | 3.98 | 3.99 | 2.05 | 1.85 | 1.22 |

| Forest cover (%)* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98 |

| Mean annual precipitation (mm)** | 984 | 947 | 866 | 1071 | 676 |

| Mean runoff (l·s−1·km−2)** | 9.96 | 9.60 | 7.16 | 18.18 | 6.35 |

| Period | SL | SO | SU | ZE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2006 | 1.33 | 1.32 | 0.00 | 8.40 |

| 2006–2009 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 4.08 |

| 2009–2012 | 1.17 | 1.37 | 0.66 | 5.54 |

| 2012–2014 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.06 |

| 2014–2016 | 1.03 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 3.73 |

| 2016–2018 | 3.88 | 9.22 | 2.49 | 6.28 |

| 2018–2020 | 8.73 | 18.81 | 5.81 | 21.86 |

| 2020–2022 | 15.81 | 7.73 | 7.46 | 18.00 |

| 2022–2024 | 0.24 | 6.08 | 0.00 | 7.06 |

| Locality* | pH | NH4+ (mg·l−1) |

Ca2+ (mg·l−1) |

K+ (mg·l−1) |

Mg2+ (mg·l−1) |

Na+ (mg·l−1) |

Cl− (mg·l−1) |

NO3− (mg·l−1) |

SO42− (mg·l−1) |

HCO3− (mg·l−1) |

DOC (mg·l−1) | TN (mg·l−1) |

EC (μS·cm−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL+SO+SU | Mean | 5.56 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 1.15 | 3.02 | 0.67 | 10.06 |

| STD | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 1.13 | 1.04 | 0.34 | 2.94 | |

| CE | Mean | 5.40 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 2.32 | 0.79 | 0.87 | 2.20 | 1.13 | 14.77 |

| STD | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.17 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 1.98 | 0.38 | 1.50 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 7.10 | |

| ZE | Mean | 5.67 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 1.83 | 0.94 | 0.41 | 2.65 | 1.16 | 20.05 |

| STD | 0.51 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 1.35 | 0.57 | 1.01 | 1.49 | 1.49 | 23.38 |

| Locality* | pH | NH4+ (mg·l−1) |

Ca2+ (mg·l−1) |

K+ (mg·l−1) |

Mg2+ (mg·l−1) |

Na+ (mg·l−1) |

Cl− (mg·l−1) |

NO3− (mg·l−1) |

SO42− (mg·l−1) |

HCO3− (mg·l−1) |

DOC (mg·l−1) |

TN (mg·l−1) |

EC (μS·cm−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL | Mean | 7.17 | 0.01 | 7.16 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 1.63 | 1.15 | 2.82 | 9.60 | 14.71 | 1.51 | 0.73 | 61.84 |

| STD | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 2.43 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 4.40 | |

| SO | Mean | 7.32 | 0.01 | 9.99 | 0.80 | 1.11 | 1.90 | 1.14 | 3.52 | 11.77 | 21.94 | 1.78 | 0.87 | 79.48 |

| STD | 0.16 | 0.01 | 1.22 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 0.90 | 3.24 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 6.85 | |

| SU | Mean | 7.30 | 0.01 | 10.05 | 0.70 | 1.60 | 2.17 | 1.45 | 2.32 | 16.22 | 20.34 | 2.02 | 0.62 | 87.04 |

| STD | 0.14 | 0.01 | 1.16 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.63 | 1.07 | 3.14 | 0.66 | 0.18 | 7.32 | |

| CE | Mean | 7.01 | 0.02 | 4.43 | 0.99 | 2.09 | 2.38 | 0.94 | 1.32 | 11.27 | 14.04 | 2.83 | 0.42 | 60.83 |

| STD | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.64 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.69 | 5.38 | 1.01 | 0.24 | 10.20 | |

| ZE | Mean | 7.76 | 0.01 | 11.69 | 1.66 | 3.64 | 8.06 | 4.29 | 3.80 | 22.94 | 38.47 | 5.93 | 0.94 | 144.70 |

| STD | 0.31 | 0.00 | 1.25 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 1.80 | 5.30 | 4.77 | 1.22 | 0.36 | 13.00 |

| SL | SO | SU | CE | ZE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-NH4+ | -2.54 | -2.54 | -2.55 | -3.25 | -2.27 |

| N-NO3− | 0.24 | 0.61 | -0.56 | -3.48 | -0.63 |

| TN | -3.89 | -3.59 | -4.77 | -8.25 | -5.89 |

| Ca2+ | 20.15 | 26.67 | 19.03 | 19.14 | 21.33 |

| Mg2+ | 2.33 | 2.76 | 2.94 | 9.69 | 6.76 |

| K+ | -0.08 | -0.17 | -0.95 | 0.40 | 1.72 |

| Na+ | 2.26 | 4.35 | 3.50 | 11.27 | 15.02 |

| Cl− | -0.66 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 1.41 | 6.37 |

| S-SO42− | 8.03 | 9.39 | 9.60 | 17.96 | 14.18 |

| HCO3− | 34.85 | 52.30 | 31.42 | 54.78 | 70.68 |

| DOC | -22.01 | -21.75 | -22.55 | -7.12 | -4.24 |

| catchment | z1 | z2 | z3 | z4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE | 0.35 | 0.18 | -1.26 | -0.76 |

| SL | 0.46 | 1.11 | -1.31 | -0.48 |

| SO | 0.59 | 1.20 | -1.58 | -0.66 |

| SU | 0.67 | 0.94 | -1.29 | -0.72 |

| ZE | 0.05 | 0.47 | -1.24 | -0.1 |

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | Correlation | |||

| ilr1 | -0.331 | <0.001 | -0.754 | <0.001 | -0.172 | 0.060 | Strong + | ||

| ilr2 | -0.090 | 0.326 | 0.662 | <0.001 | -0.315 | <0.001 | Moderate + | ||

| ilr3 | 0.613 | <0.001 | 0.662 | <0.001 | -0.254 | 0.005 | Weak + | ||

| ilr4 | -0.343 | <0.001 | 0.521 | <0.001 | -0.381 | <0.001 | Weak - | ||

| ilr5 | -0.318 | <0.001 | -0.404 | <0.001 | 0.546 | <0.001 | Moderate - | ||

| ilr6 | 0.157 | 0.086 | 0.764 | <0.001 | -0.412 | <0.001 | Strong - | ||

| ilr7 | 0.729 | <0.001 | 0.093 | 0.313 | -0.030 | 0.746 | Non significant | ||

| EC | 0.960 | <0.001 | 0.017 | 0.852 | -0.008 | 0.929 | |||

| pH | 0.810 | <0.001 | 0.095 | 0.303 | 0.559 | <0.001 | |||

| DOC | 0.856 | <0.001 | 0.302 | <0.001 | -0.378 | <0.001 | |||

| TN | 0.555 | <0.001 | -0.805 | <0.001 | -0.174 | 0.058 | |||

| ilr1 | ilr2 | ilr3 | ilr4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | Correlation | ||

| HCO3- | -0.544 | <0.001 | -0.162 | 0.077 | 0.584 | <0.001 | -0.349 | <0.001 | Strong + | |

| NO3- | 0.520 | <0.001 | -0.512 | <0.001 | -0.153 | 0.096 | -0.608 | <0.001 | Moderate + | |

| SO42- | -0.208 | 0.022 | 0.229 | 0.012 | 0.525 | < 0.001 | -0.473 | < 0.001 | Weak + | |

| Na+ | -0.421 | <0.001 | 0.097 | 0.290 | 0.810 | <0.001 | -0.128 | 0.164 | Weak - | |

| K+ | -0.446 | <0.001 | 0.067 | 0.466 | 0.848 | <0.001 | 0.127 | 0.167 | Moderate - | |

| Ca2+ | -0.141 | 0.123 | -0.339 | <0.001 | 0.040 | 0.664 | -0.800 | <0.001 | Strong - | |

| Mg2+ | -0.550 | <0.001 | 0.347 | <0.001 | 0.897 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.837 | Non significant | |

| Cl- | -0.285 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.726 | 0.691 | < 0.001 | -0.273 | 0.003 | ||

| ilr5 | ilr6 | ilr7 | ||||||||

| r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | |||||

| HCO3- | -0.161 | 0.080 | 0.129 | 0.160 | 0.622 | <0.001 | ||||

| NO3- | 0.073 | 0.430 | -0.459 | <0.001 | 0.330 | <0.001 | ||||

| SO42- | -0.280 | 0.002 | 0.272 | 0.003 | 0.664 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Na+ | -0.534 | <0.001 | 0.374 | <0.001 | 0.776 | <0.001 | ||||

| K+ | -0.665 | <0.001 | 0.437 | <0.001 | 0.639 | <0.001 | ||||

| Ca2+ | 0.380 | <0.001 | -0.317 | <0.001 | 0.449 | <0.001 | ||||

| Mg2+ | -0.657 | <0.001 | 0.639 | <0.001 | 0.623 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cl- | -0.420 | < 0.001 | 0.231 | 0.011 | 0.864 | < 0.001 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).