1. Introduction

Achieving a smarter and sustainable aquaculture and fishing industry, equipped with technological advancements tailored to climate change and its monitoring, stands as a predominant objective in marine science research and development. The inadequate planning could become economically unsustainable due to climate stressors and the actual climate variances have impacted aquaculture production negatively around the world ([

1]). There has been a notable increase in the amplitude of the daily sea surface temperature (SST) seasonal cycle over many ocean basins since 1950 ([

2]). Also, many studies have tried to analyze these trends, highlighting that some areas are more vulnerable than others. Our area of interest, located in the Mediterranean Sea, is one of these sensitive regions ([

3]). This region is recognized as the largest climate change hotspot, experiencing warming rates up to 20% higher than the global average ([

4]).

In order to establish a better spatial planning for the sustaintable acuaculture, the Available Zones for Aquaculture (AZAs) defined by the FAO ([

5]) summarize the main oceanographic features necessary for developing sustainable aquaculture along the Mediterranean coast. However, under a climate change scenario, these conditions will evolve in the coming decades. The magnitude and frequency of these changes will expose cultivated species to varying levels of stress, which may directly affect their health and survival ([

6,

7]). Relocating fish farms to areas less sensitive to climate change is one option for mitigating the effects of temperature increase ([

8,

9]), and efficient Marine Spatial Planning must be performed. It is crucial to consider the factors that have the greatest impact on the survival of cultured species. Studies about growing projections in a climate change scenario in the Mediterranean Sea ([

10]) alert about future areas that will be more suitable for aquaculture, and it is expected that the western Mediterranean becomes the suitable one. In order to archive that, we need to pay attention to studies like [

11], which summarize about all the stressors in the cultivated species in a warming climate change scenario.

Some studies confirm a persistent warming trend in daily sea surface temperature (SST) data derived from satellites throughout the Mediterranean region. This increase in temperature is observed on various temporal scales, ranging from daily to monthly, seasonal, and decadal assessments, affecting not only surface waters but also extending to deeper and intermediate areas ([

3,

11]). While there is some controversy surrounding this issue, [

8] emphasized the potential effects of increased surface temperature on coastal aquaculture, acknowledging both negative and positive impacts. Several studies have demonstrated that SST variability is significantly correlated with fish growth,(Islam et al., 2020; Haberle et al., 2024). Islam et al. (2021) conducted a comprehensive study on the effects of climate change on aquaculture. Additionally, high to moderate temperatures may have beneficial effects on growth models, but they can also potentially cause muscular dystrophies and neurological impairments, among others (Madeira et al., 2020). For this reason is difficult to set up a braking point for the SST in the aquaculture context. The season of growth and climate risk may differ from one year to another, sometimes overlapping among them. This is supported by the study of [

11] which shows how the range of seasonal patterns is changing due to the effects of climate change in the Mediterranean Sea.

Within this context, the present study aims to focus on the risks associated with coastal warming for aquaculture. Therefore, it is essential to understand how temperatures have evolved during key periods in the past to better predict their future trends. To achieve this, the focus must be on potentially cultivable areas, specifically in seashore areas within 50 km from the coast to facilitate the establishment of logistical bases. The primary objective is to generate 10-year future predictions of SST and conduct a temporal analysis from 1990 to the present, including interannual variability. The locations studied for this objective are several points where aquaculture activity is currently taking place. Secondly, we aim to delve into the spatio-temporal variability of the maximum SST recorded in the area, as well as the temperature range (difference between maximum and minimum values). In order to improve and expand the avaliable information from the data, a complex prediction model will increase the resolution of the area and the coverage of the data near to the weak points as the coastal margins.This spatio temporal model will cover the ummarizing, this study aims to provide a localized and detailed assessment of climate risks associated with high temperatures in a region where aquaculture plays a significant role. By addressing both historical variability and future projections, the research seeks to equip stakeholders with the insights needed to mitigate risks and adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Figure 1.

Area of study located in the western Mediterranean (left) and locations details (right).

Figure 1.

Area of study located in the western Mediterranean (left) and locations details (right).

Figure 2.

Seasonal time series of SST at each location, showing observed data and ARIMA-based 10-year prediction band (pink). The shaded area indicates the forecast uncertainty. The plot highlights seasonal variation, with summer months showing higher inter-annual variability, while winter months remain relatively stable.

Figure 2.

Seasonal time series of SST at each location, showing observed data and ARIMA-based 10-year prediction band (pink). The shaded area indicates the forecast uncertainty. The plot highlights seasonal variation, with summer months showing higher inter-annual variability, while winter months remain relatively stable.

Figure 3.

Trend decomposition of SST time series and 10-year ARIMA predictions for each location. Points represent monthly SST observations, lines the trend component, and the shaded area the prediction interval. Seasonal and latitudinal variations are captured in the trend component

Figure 3.

Trend decomposition of SST time series and 10-year ARIMA predictions for each location. Points represent monthly SST observations, lines the trend component, and the shaded area the prediction interval. Seasonal and latitudinal variations are captured in the trend component

Figure 4.

Predicted maximum monthly SST (June–October) across all locations from 1995 to 2024, obtained from the spatio-temporal INLA model. Colors represent SST in °C. The model captures both spatial and temporal variation, with the shaded areas (or color gradient) reflecting the uncertainty of the predictions. A slight upward trend is observed in maximum SST, particularly during 2015–2024. The effective range of the spatial Gaussian field is 246 km, indicating the distance over which spatial correlation stabilizes.

Figure 4.

Predicted maximum monthly SST (June–October) across all locations from 1995 to 2024, obtained from the spatio-temporal INLA model. Colors represent SST in °C. The model captures both spatial and temporal variation, with the shaded areas (or color gradient) reflecting the uncertainty of the predictions. A slight upward trend is observed in maximum SST, particularly during 2015–2024. The effective range of the spatial Gaussian field is 246 km, indicating the distance over which spatial correlation stabilizes.

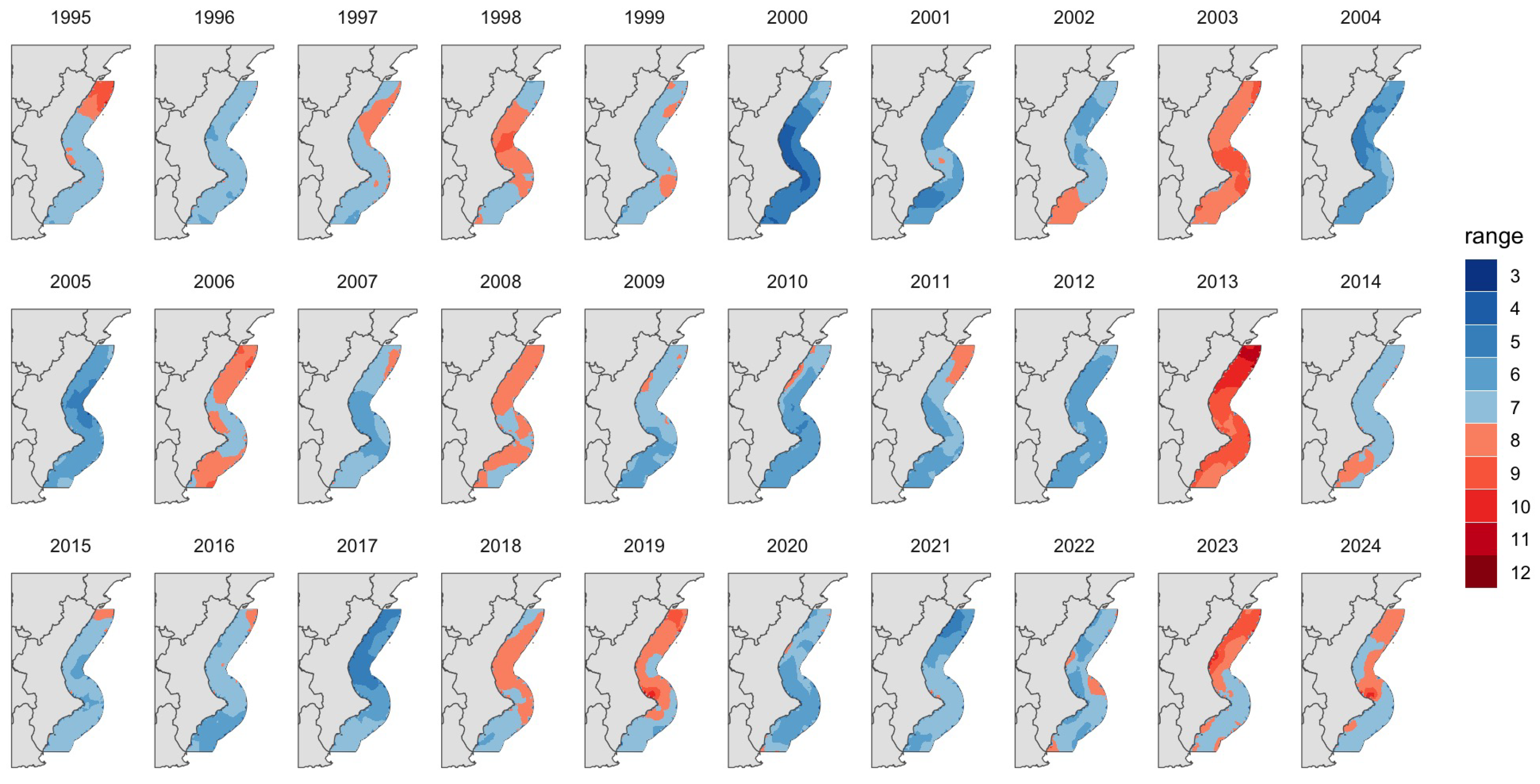

Figure 5.

Predicted range of monthly SST (difference between maximum and minimum SST) for June–October, 1995–2024. Colors indicate the magnitude of SST variability (°C), with higher ranges corresponding to greater intra-annual variation. The spatial model accounts for temporal and spatial correlation, with an effective range of 207 km.

Figure 5.

Predicted range of monthly SST (difference between maximum and minimum SST) for June–October, 1995–2024. Colors indicate the magnitude of SST variability (°C), with higher ranges corresponding to greater intra-annual variation. The spatial model accounts for temporal and spatial correlation, with an effective range of 207 km.

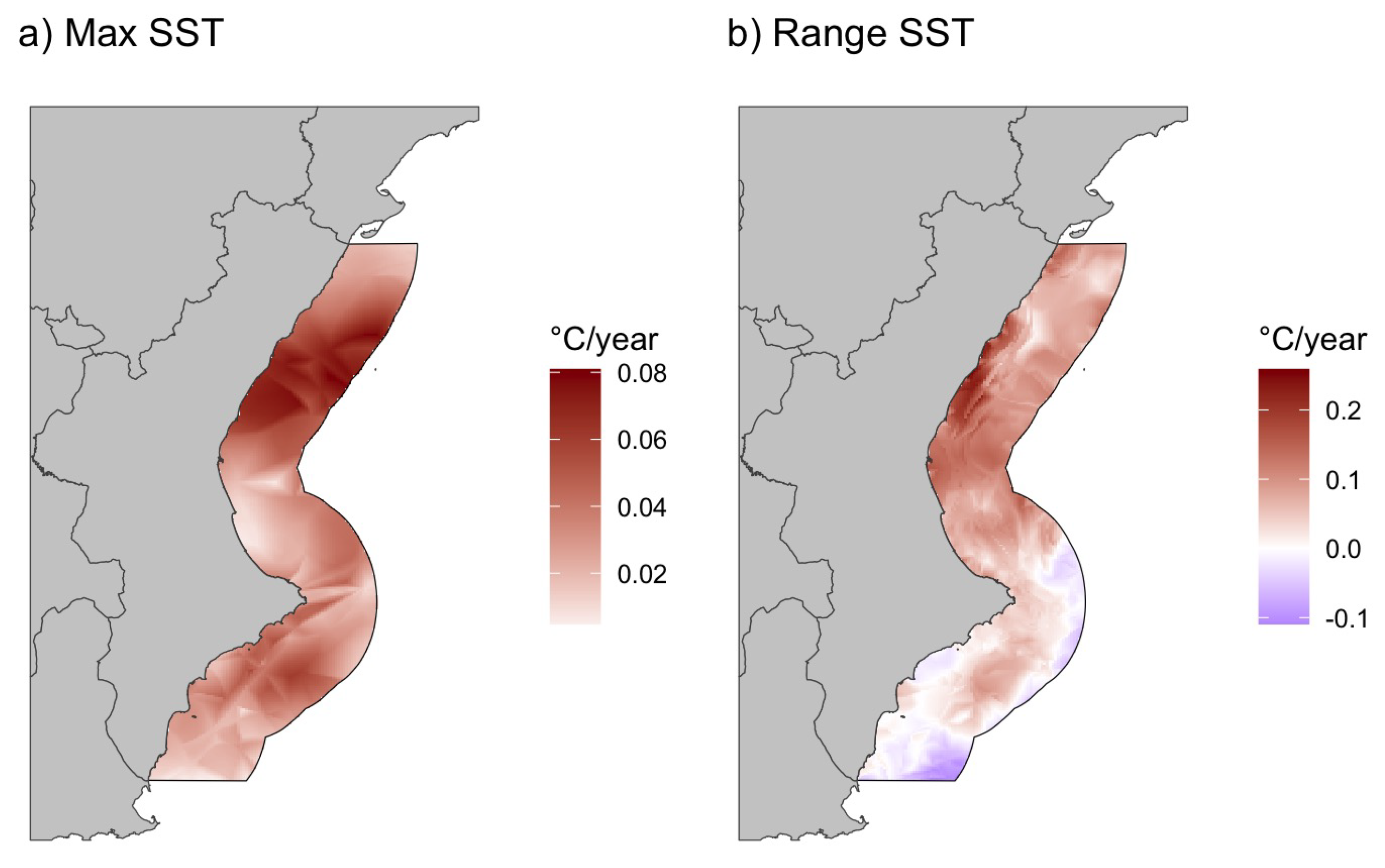

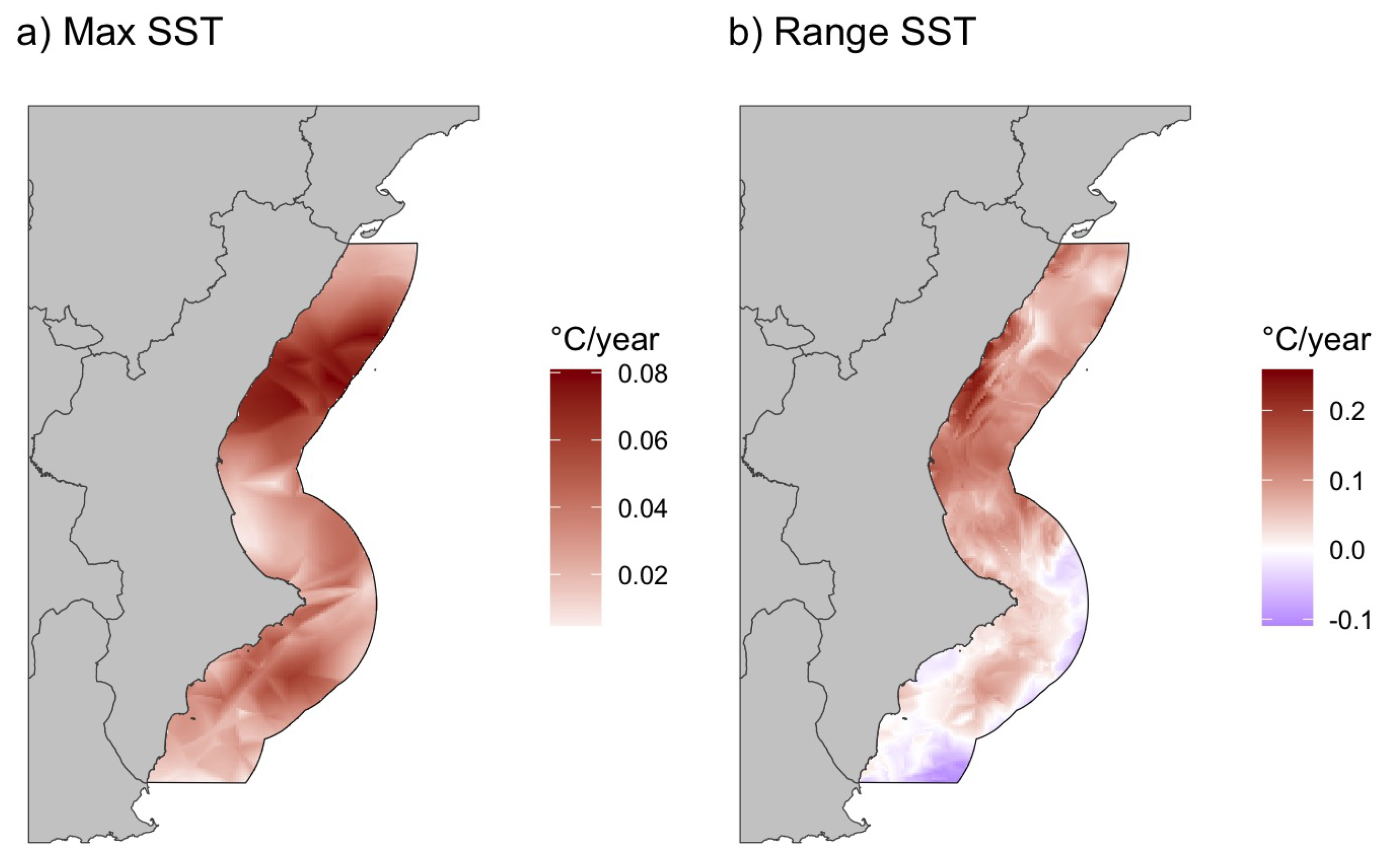

Figure 6.

Sen’s slope estimates for the long-term trends in SST maxima (panel a) and SST ranges (panel b) across the study area. The slopes quantify annual change (°C/year), highlighting areas with significant warming or increased variability. This analysis complements the spatio-temporal model predictions, confirming the seasonal and inter-annual patterns of warming and variability.

Figure 6.

Sen’s slope estimates for the long-term trends in SST maxima (panel a) and SST ranges (panel b) across the study area. The slopes quantify annual change (°C/year), highlighting areas with significant warming or increased variability. This analysis complements the spatio-temporal model predictions, confirming the seasonal and inter-annual patterns of warming and variability.

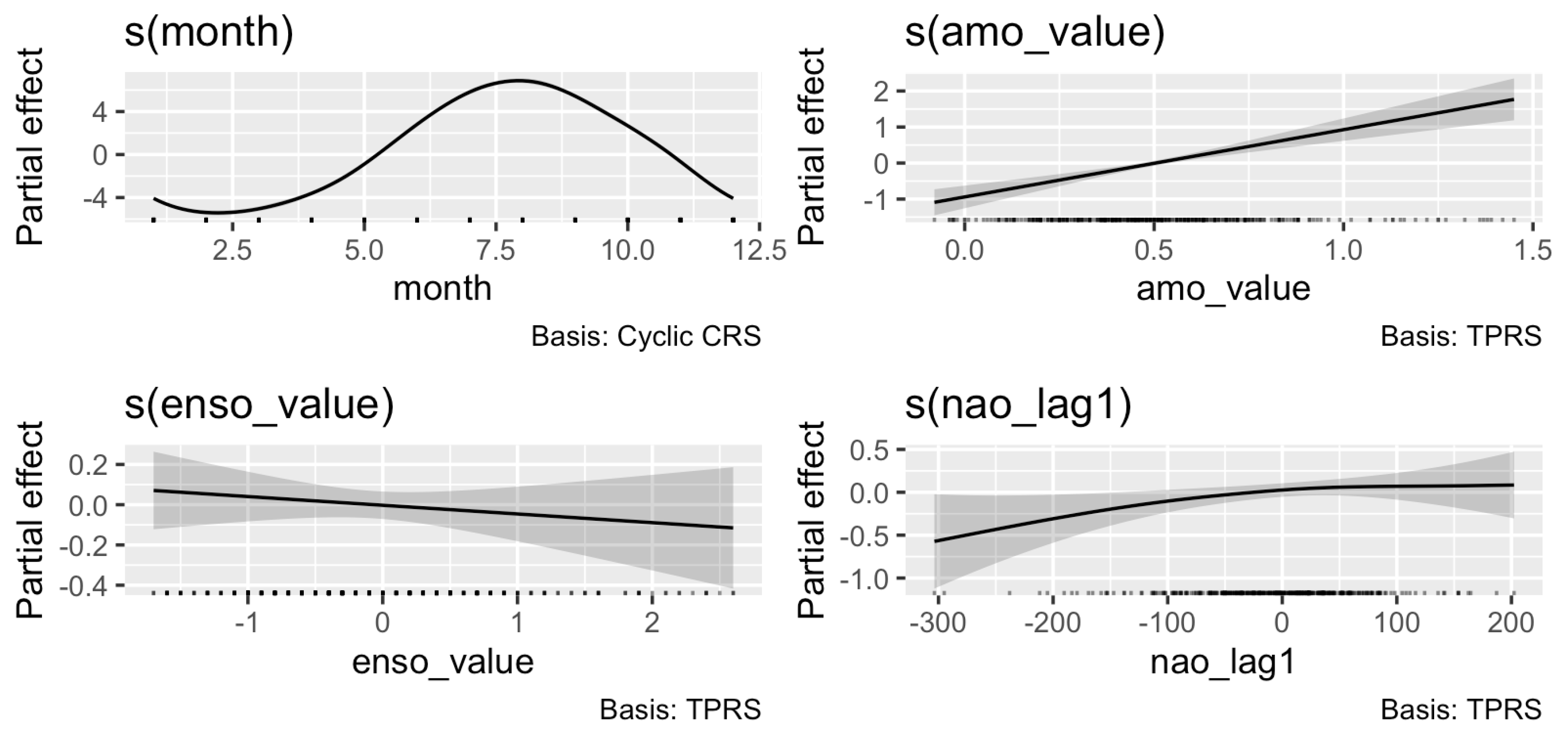

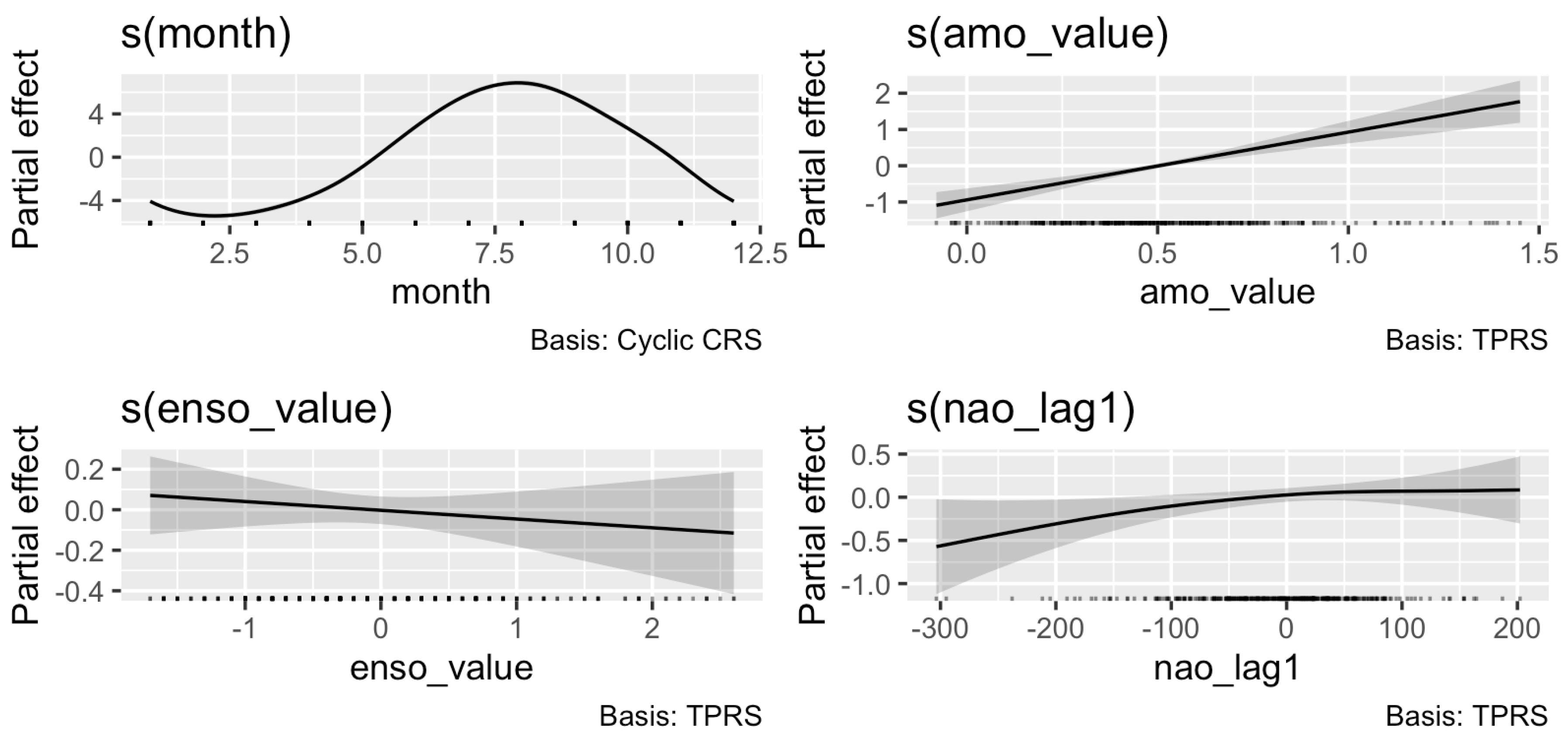

Figure 7.

Estimated smooth effects of cyclic month, AMO, ENSO index, and lagged NAO on monthly SST, obtained from the GAM. Each panel shows the partial effect of the corresponding predictor, with the solid line representing the estimated smooth function and the shaded area its 95% confidence interval (calculated using the Bayesian covariance matrix of the smooth). The y-axis indicates the deviation in SST (°C) relative to the model intercept. A smooth is considered statistically significant if its confidence band does not overlap zero and/or if the associated approximate significance test (summary output) yields .

Figure 7.

Estimated smooth effects of cyclic month, AMO, ENSO index, and lagged NAO on monthly SST, obtained from the GAM. Each panel shows the partial effect of the corresponding predictor, with the solid line representing the estimated smooth function and the shaded area its 95% confidence interval (calculated using the Bayesian covariance matrix of the smooth). The y-axis indicates the deviation in SST (°C) relative to the model intercept. A smooth is considered statistically significant if its confidence band does not overlap zero and/or if the associated approximate significance test (summary output) yields .

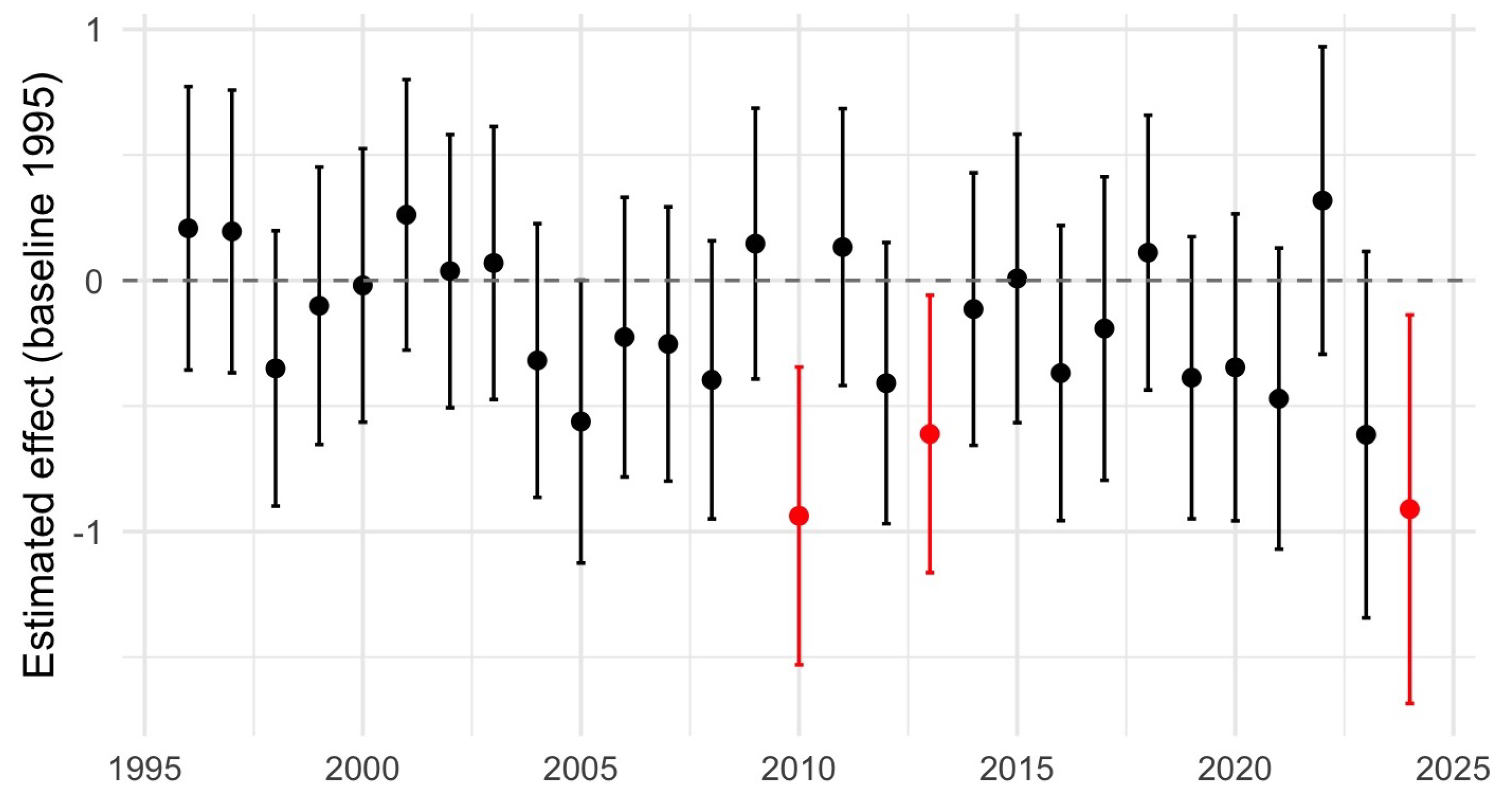

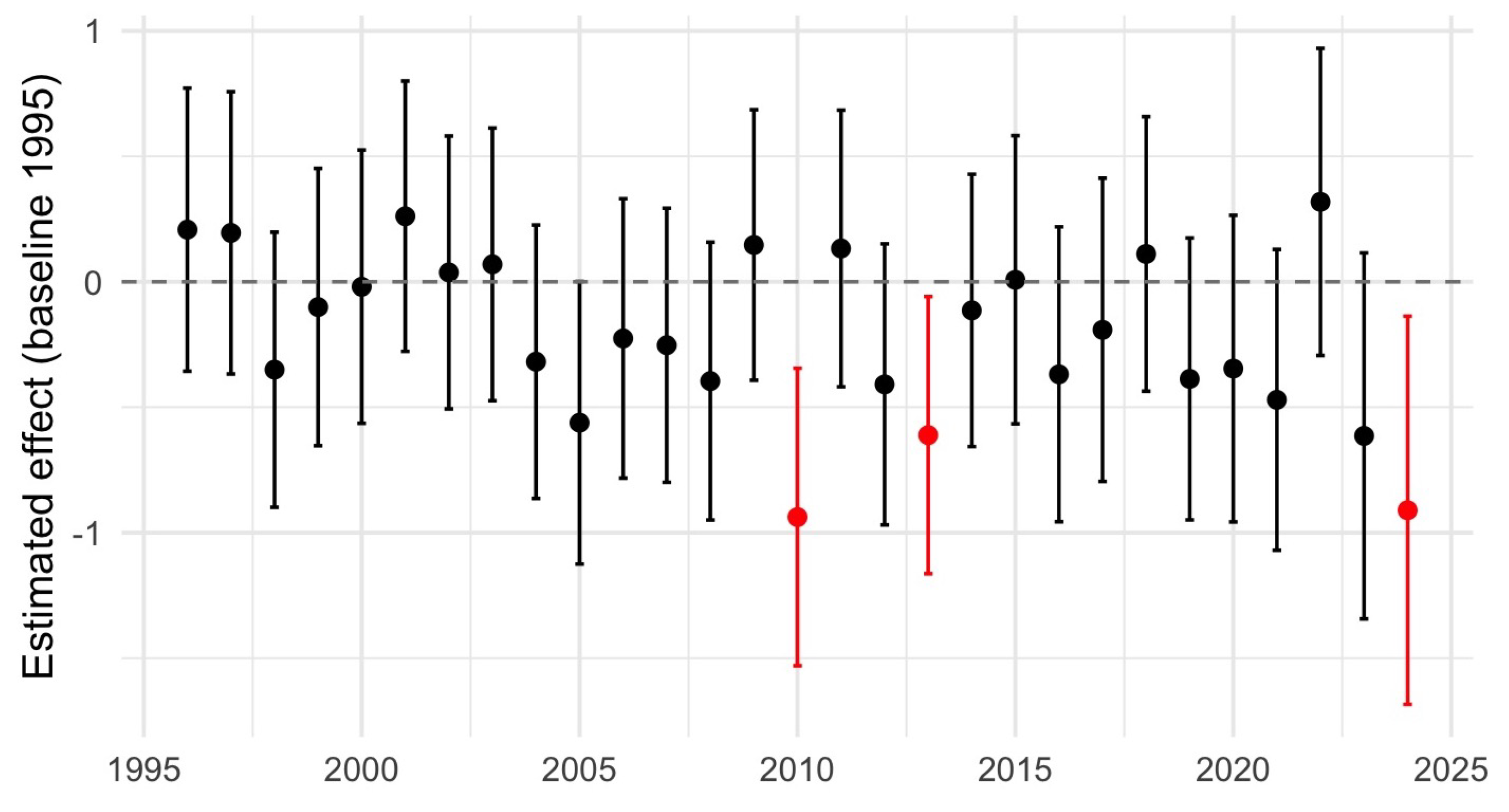

Figure 8.

Forest plot of estimated annual effects (±95% confidence intervals) of year on monthly sea surface temperature (SST), relative to the baseline year 1995. Points represent model coefficients from the GAM, with vertical lines indicating approximate 95% confidence intervals calculated as estimate ± 1.96 × SE. Years shown in red are significantly lower than the baseline ( .), based on parametric tests in the GAM summary. Non-significant effects are shown in black. The dashed horizontal line marks zero, i.e., no difference from the reference year.

Figure 8.

Forest plot of estimated annual effects (±95% confidence intervals) of year on monthly sea surface temperature (SST), relative to the baseline year 1995. Points represent model coefficients from the GAM, with vertical lines indicating approximate 95% confidence intervals calculated as estimate ± 1.96 × SE. Years shown in red are significantly lower than the baseline ( .), based on parametric tests in the GAM summary. Non-significant effects are shown in black. The dashed horizontal line marks zero, i.e., no difference from the reference year.

Figure 9.

Seasonal time series of SST at each location, showing observed data and ARIMA-based 10-year prediction band (pink). The shaded area indicates the forecast uncertainty. The plot highlights seasonal variation, with summer months showing higher inter-annual variability, while winter months remain relatively stable.

Figure 9.

Seasonal time series of SST at each location, showing observed data and ARIMA-based 10-year prediction band (pink). The shaded area indicates the forecast uncertainty. The plot highlights seasonal variation, with summer months showing higher inter-annual variability, while winter months remain relatively stable.

Figure 10.

Trend decomposition of SST time series and 10-year ARIMA predictions for each location. Points represent monthly SST observations, lines the trend component, and the shaded area the prediction interval. Seasonal and latitudinal variations are captured in the trend component

Figure 10.

Trend decomposition of SST time series and 10-year ARIMA predictions for each location. Points represent monthly SST observations, lines the trend component, and the shaded area the prediction interval. Seasonal and latitudinal variations are captured in the trend component

Figure 11.

Predicted maximum monthly SST (June–October) across all locations from 1995 to 2024, obtained from the spatio-temporal INLA model. Colors represent SST in °C. The model captures both spatial and temporal variation, with the shaded areas (or color gradient) reflecting the uncertainty of the predictions. A slight upward trend is observed in maximum SST, particularly during 2015–2024. The effective range of the spatial Gaussian field is 246 km, indicating the distance over which spatial correlation stabilizes.

Figure 11.

Predicted maximum monthly SST (June–October) across all locations from 1995 to 2024, obtained from the spatio-temporal INLA model. Colors represent SST in °C. The model captures both spatial and temporal variation, with the shaded areas (or color gradient) reflecting the uncertainty of the predictions. A slight upward trend is observed in maximum SST, particularly during 2015–2024. The effective range of the spatial Gaussian field is 246 km, indicating the distance over which spatial correlation stabilizes.

Figure 12.

Predicted range of monthly SST (difference between maximum and minimum SST) for June–October, 1995–2024. Colors indicate the magnitude of SST variability (°C), with higher ranges corresponding to greater intra-annual variation. The spatial model accounts for temporal and spatial correlation, with an effective range of 207 km.

Figure 12.

Predicted range of monthly SST (difference between maximum and minimum SST) for June–October, 1995–2024. Colors indicate the magnitude of SST variability (°C), with higher ranges corresponding to greater intra-annual variation. The spatial model accounts for temporal and spatial correlation, with an effective range of 207 km.

Figure 13.

Sen’s slope estimates for the long-term trends in SST maxima (panel a) and SST ranges (panel b) across the study area. The slopes quantify annual change (°C/year), highlighting areas with significant warming or increased variability. This analysis complements the spatio-temporal model predictions, confirming the seasonal and inter-annual patterns of warming and variability.

Figure 13.

Sen’s slope estimates for the long-term trends in SST maxima (panel a) and SST ranges (panel b) across the study area. The slopes quantify annual change (°C/year), highlighting areas with significant warming or increased variability. This analysis complements the spatio-temporal model predictions, confirming the seasonal and inter-annual patterns of warming and variability.

Figure 14.

Estimated smooth effects of cyclic month, AMO, ENSO index, and lagged NAO on monthly SST, obtained from the GAM. Each panel shows the partial effect of the corresponding predictor, with the solid line representing the estimated smooth function and the shaded area its 95% confidence interval (calculated using the Bayesian covariance matrix of the smooth). The y-axis indicates the deviation in SST (°C) relative to the model intercept. A smooth is considered statistically significant if its confidence band does not overlap zero and/or if the associated approximate significance test (summary output) yields .

Figure 14.

Estimated smooth effects of cyclic month, AMO, ENSO index, and lagged NAO on monthly SST, obtained from the GAM. Each panel shows the partial effect of the corresponding predictor, with the solid line representing the estimated smooth function and the shaded area its 95% confidence interval (calculated using the Bayesian covariance matrix of the smooth). The y-axis indicates the deviation in SST (°C) relative to the model intercept. A smooth is considered statistically significant if its confidence band does not overlap zero and/or if the associated approximate significance test (summary output) yields .

Figure 15.

Forest plot of estimated annual effects (±95% confidence intervals) of year on monthly sea surface temperature (SST), relative to the baseline year 1995. Points represent model coefficients from the GAM, with vertical lines indicating approximate 95% confidence intervals calculated as estimate ± 1.96 × SE. Years shown in red are significantly lower than the baseline ( .), based on parametric tests in the GAM summary. Non-significant effects are shown in black. The dashed horizontal line marks zero, i.e., no difference from the reference year.

Figure 15.

Forest plot of estimated annual effects (±95% confidence intervals) of year on monthly sea surface temperature (SST), relative to the baseline year 1995. Points represent model coefficients from the GAM, with vertical lines indicating approximate 95% confidence intervals calculated as estimate ± 1.96 × SE. Years shown in red are significantly lower than the baseline ( .), based on parametric tests in the GAM summary. Non-significant effects are shown in black. The dashed horizontal line marks zero, i.e., no difference from the reference year.

Table 1.

parameter values. represents the magnitude of the autoregressive effect from the previous month, the impact of the previous month’s error term, and the effect of the error 12 months prior. Northern locations show lower values, indicating smaller month-to-month autocorrelation, while and are similar across sites, with small differences in magnitude.

Table 1.

parameter values. represents the magnitude of the autoregressive effect from the previous month, the impact of the previous month’s error term, and the effect of the error 12 months prior. Northern locations show lower values, indicating smaller month-to-month autocorrelation, while and are similar across sites, with small differences in magnitude.

| |

|

|

|

| Vinaroz |

0.300 |

-1.000 |

-0.922 |

| Burriana |

0.326 |

-1.000 |

-0.916 |

| Sagunto |

0.333 |

-1.000 |

-0.929 |

| Valencia |

0.350 |

-1.000 |

-0.930 |

| Denia |

0.387 |

-1.000 |

-0.920 |

| Altea |

0.404 |

-1.000 |

-0.885 |

| Campello |

0.416 |

-0.997 |

-0.925 |

| Guardamar |

0.386 |

-0.994 |

-0.900 |

Table 2.

Posterior summaries of the maximum SST spatio-temporal model (40% of the data). is the intercept on the log scale, is the residual standard deviation, “Range for i” indicates the effective spatial range of the Gaussian field (km), and “sd for i” the standard deviation of the spatial effect. The results show a moderate spatial correlation (246 km) and low residual uncertainty.

Table 2.

Posterior summaries of the maximum SST spatio-temporal model (40% of the data). is the intercept on the log scale, is the residual standard deviation, “Range for i” indicates the effective spatial range of the Gaussian field (km), and “sd for i” the standard deviation of the spatial effect. The results show a moderate spatial correlation (246 km) and low residual uncertainty.

| |

mean |

sd |

|

|

|

|

5.706 |

0.0024 |

5.701 |

5.706 |

5.710 |

|

0.002 |

0.000021 |

0.002 |

0.002 |

0.002 |

| Range for i

|

246.365 |

16.756 |

212.799 |

246.700 |

278.490 |

| sd for i

|

0.0046 |

0.0003 |

0.0041 |

0.0046 |

0.0051 |

Table 3.

Posterior summaries of the SST range spatio-temporal model (35% of the data). The parameters are analogous to Table \ref{tab:st_param_max}. The effective spatial range is slightly smaller (207 km), indicating stronger localized spatial correlation for SST variability.

Table 3.

Posterior summaries of the SST range spatio-temporal model (35% of the data). The parameters are analogous to Table \ref{tab:st_param_max}. The effective spatial range is slightly smaller (207 km), indicating stronger localized spatial correlation for SST variability.

| |

mean |

sd |

|

|

|

|

1.293 |

0.111 |

1.074 |

1.293 |

1.512 |

|

0.005 |

0.000085 |

0.005 |

0.005 |

0.004 |

| Range for i

|

207.767 |

7.695 |

194.379 |

207.162 |

224.596 |

| sd for i

|

0.298 |

0.010 |

0.280 |

0.297 |

0.321 |

Table 4.

Bibliographic recompilation of different studies about extreme sea surface temperatures and their effects in the Mediterranean Sea

Table 4.

Bibliographic recompilation of different studies about extreme sea surface temperatures and their effects in the Mediterranean Sea

| Years of interest |

Impact type |

Reference |

| 2018, 2003 |

MHWs with medicanes |

[39] |

| 2022, 2016 |

MHWs in the West Med |

[40] |

| 2003, 2020 |

EMS in the West Med |

[41] |

| 2008-2017 |

Higher SST trend in the West Med |

[42] |

| 2003, 2018, 2015 |

MHWs in the West Med |

[43] |

| 1998, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2022 |

Sumer and Autumn MHWs in the Med |

[44] |

Table 5.

Summary of smooth effects from the GAM of monthly SST.The estimated degrees of freedom (edf) indicate the complexity of the smooth function(EDF corresponds to a linear effect, higher values indicate non-linear responses).F-tests are approximate significance tests for each smooth term. SST shows a strong seasonal cycle () and a significant positive association with AMO. ENSO and lagged NAO did not contribute significantly.

Table 5.

Summary of smooth effects from the GAM of monthly SST.The estimated degrees of freedom (edf) indicate the complexity of the smooth function(EDF corresponds to a linear effect, higher values indicate non-linear responses).F-tests are approximate significance tests for each smooth term. SST shows a strong seasonal cycle () and a significant positive association with AMO. ENSO and lagged NAO did not contribute significantly.

| Term |

EDF |

Ref.df |

F |

p-valor |

|

7.688 |

8.000 |

1527.703 |

p < 0.001 |

|

1.000 |

1.001 |

36.031 |

p < 0.001 |

|

1.000 |

1.001 |

589 |

0.443 |

|

1.849 |

2.388 |

2.264 |

0.930 |

Table 6.

parameter values. represents the magnitude of the autoregressive effect from the previous month, the impact of the previous month’s error term, and the effect of the error 12 months prior. Northern locations show lower values, indicating smaller month-to-month autocorrelation, while and are similar across sites, with small differences in magnitude.

Table 6.

parameter values. represents the magnitude of the autoregressive effect from the previous month, the impact of the previous month’s error term, and the effect of the error 12 months prior. Northern locations show lower values, indicating smaller month-to-month autocorrelation, while and are similar across sites, with small differences in magnitude.

| |

|

|

|

| Vinaroz |

0.300 |

-1.000 |

-0.922 |

| Burriana |

0.326 |

-1.000 |

-0.916 |

| Sagunto |

0.333 |

-1.000 |

-0.929 |

| Valencia |

0.350 |

-1.000 |

-0.930 |

| Denia |

0.387 |

-1.000 |

-0.920 |

| Altea |

0.404 |

-1.000 |

-0.885 |

| Campello |

0.416 |

-0.997 |

-0.925 |

| Guardamar |

0.386 |

-0.994 |

-0.900 |

Table 7.

Posterior summaries of the maximum SST spatio-temporal model (40% of the data). is the intercept on the log scale, is the residual standard deviation, “Range for i” indicates the effective spatial range of the Gaussian field (km), and “sd for i” the standard deviation of the spatial effect. The results show a moderate spatial correlation (246 km) and low residual uncertainty.

Table 7.

Posterior summaries of the maximum SST spatio-temporal model (40% of the data). is the intercept on the log scale, is the residual standard deviation, “Range for i” indicates the effective spatial range of the Gaussian field (km), and “sd for i” the standard deviation of the spatial effect. The results show a moderate spatial correlation (246 km) and low residual uncertainty.

| |

mean |

sd |

|

|

|

|

5.706 |

0.0024 |

5.701 |

5.706 |

5.710 |

|

0.002 |

0.000021 |

0.002 |

0.002 |

0.002 |

| Range for i

|

246.365 |

16.756 |

212.799 |

246.700 |

278.490 |

| sd for i

|

0.0046 |

0.0003 |

0.0041 |

0.0046 |

0.0051 |

Table 8.

Posterior summaries of the SST range spatio-temporal model (35% of the data). The parameters are analogous to Table \ref{tab:st_param_max}. The effective spatial range is slightly smaller (207 km), indicating stronger localized spatial correlation for SST variability.

Table 8.

Posterior summaries of the SST range spatio-temporal model (35% of the data). The parameters are analogous to Table \ref{tab:st_param_max}. The effective spatial range is slightly smaller (207 km), indicating stronger localized spatial correlation for SST variability.

| |

mean |

sd |

|

|

|

|

1.293 |

0.111 |

1.074 |

1.293 |

1.512 |

|

0.005 |

0.000085 |

0.005 |

0.005 |

0.004 |

| Range for i

|

207.767 |

7.695 |

194.379 |

207.162 |

224.596 |

| sd for i

|

0.298 |

0.010 |

0.280 |

0.297 |

0.321 |

Table 9.

Bibliographic recompilation of different studies about extreme sea surface temperatures and their effects in the Mediterranean Sea

Table 9.

Bibliographic recompilation of different studies about extreme sea surface temperatures and their effects in the Mediterranean Sea

| Years of interest |

Impact type |

Reference |

| 2018, 2003 |

MHWs with medicanes |

[39] |

| 2022, 2016 |

MHWs in the West Med |

[40] |

| 2003, 2020 |

EMS in the West Med |

[41] |

| 2008-2017 |

Higher SST trend in the West Med |

[42] |

| 2003, 2018, 2015 |

MHWs in the West Med |

[43] |

| 1998, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2022 |

Sumer and Autumn MHWs in the Med |

[44] |

Table 10.

Summary of smooth effects from the GAM of monthly SST.The estimated degrees of freedom (edf) indicate the complexity of the smooth function(EDF corresponds to a linear effect, higher values indicate non-linear responses).F-tests are approximate significance tests for each smooth term. SST shows a strong seasonal cycle () and a significant positive association with AMO. ENSO and lagged NAO did not contribute significantly.

Table 10.

Summary of smooth effects from the GAM of monthly SST.The estimated degrees of freedom (edf) indicate the complexity of the smooth function(EDF corresponds to a linear effect, higher values indicate non-linear responses).F-tests are approximate significance tests for each smooth term. SST shows a strong seasonal cycle () and a significant positive association with AMO. ENSO and lagged NAO did not contribute significantly.

| Term |

EDF |

Ref.df |

F |

p-valor |

|

7.688 |

8.000 |

1527.703 |

p < 0.001 |

|

1.000 |

1.001 |

36.031 |

p < 0.001 |

|

1.000 |

1.001 |

589 |

0.443 |

|

1.849 |

2.388 |

2.264 |

0.930 |