1. Introduction

Over the past decade, the notion of cognitive warfare has moved from a marginal expression in military circles to a recurrent label in doctrine, policy debates, and academic research (NATO 2021; Rid 2020; Marsili 2023, 2025a). NATO’s Allied Command Transformation describes cognitive warfare as a form of competition that targets human cognition itself, exploiting vulnerabilities in perception, emotion, and reasoning in order to weaken societies from within (NATO 2021). Building on this emerging doctrinal vocabulary, scholars and practitioners analyze cognitive warfare as a specific configuration of disinformation, computational propaganda, and influence operations in digital environments, while also underscoring its fluid and contested conceptual boundaries (Rid 2020; Marsili 2023, 2025a).

Public and policy discourse often present cognitive warfare as a radically new threat, born out of social media platforms, big data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI) (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024). Yet many of the practices now grouped under this label—psychological operations, propaganda, deception, and the manipulation of information flows—have a much longer history. Modern psychological warfare emerged during the First and Second World Wars, when mass literacy, industrialised media, and total war created unprecedented incentives to target the morale and beliefs of both enemy troops and civilian populations (Taylor 2003; Cull 2008). During the Cold War, large-scale campaigns such as the broadcasts of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, covert information operations, and “wars of ideas” crystallised a repertoire of techniques designed to influence, confuse, or demoralise adversaries without crossing the threshold of open armed conflict (Puddington 2000; Johnson 2010).

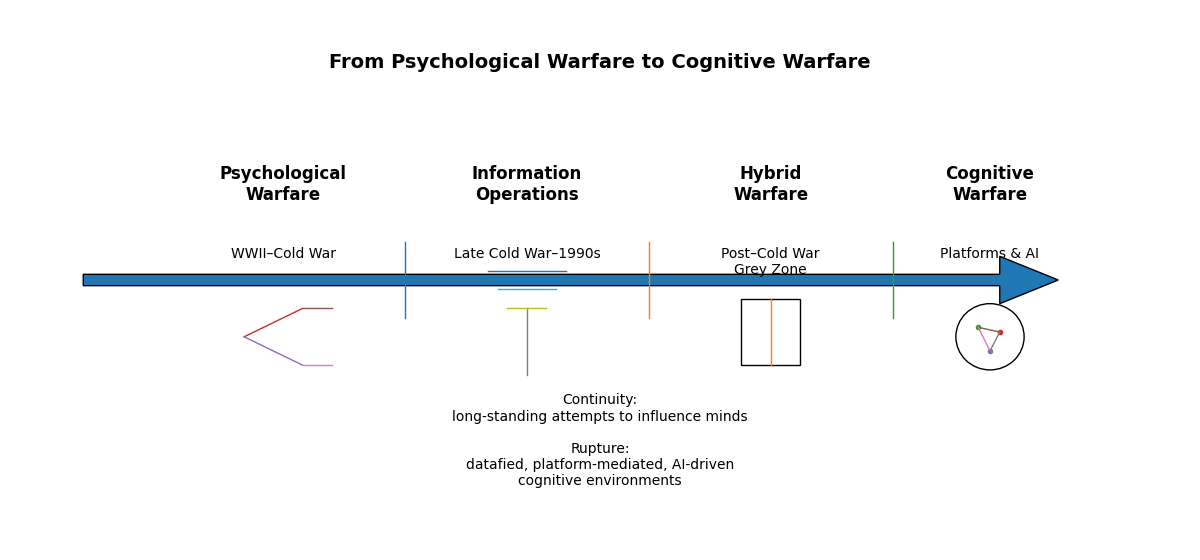

The present article argues that cognitive warfare should be understood as the latest phase in a longer historical trajectory of efforts to shape the “battlefield of the mind”. Rather than treating cognitive warfare as an ex nihilo invention of the 2010s, the analysis places it in a historical perspective that connects twentieth-century psychological warfare and propaganda, post-Cold War information operations, and the recent proliferation of AI-enabled manipulative techniques (Hoffman 2007; Rid 2020; Marsili 2023). The discussion builds on both the emerging conceptual literature on cognitive warfare and previous studies on hybrid warfare, information control, and digital transformation, including analyses devoted to cyber and information operations, the infodemic, and cognitive manipulation in the metaverse (Marsili 2019, 2020, 2025a; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024).

The approach adopted in this article is intentionally historical and genealogical. First, the analysis reconstructs the evolution of psychological and information warfare from the 1930s to the end of the Cold War, focusing on how states experimented with mass persuasion, psychological operations, and the instrumentalisation of media technologies (Taylor 2003; Cull 2008). Second, attention is devoted to the post-Cold War emergence of hybrid warfare, in which information operations, cyber activities, and economic coercion are combined to undermine the political cohesion of targeted states (Hoffman 2007; Marsili 2019, 2023). Russia’s campaigns in Ukraine since 2014 and in Western democracies more broadly provide a paradigmatic case of this hybridisation of military and informational strategies (Galeotti 2016; Marsili 2021, 2023). Third, the article examines how digital platforms, social media ecosystems, and AI-driven content production have intensified the reach, speed, and granularity of influence operations, enabling a form of cognitive warfare that operates not only through public propaganda but also through personalised, data-driven interventions in users’ information environments (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025b).

On this basis, the article advances a twofold argument. Empirically, it reconstructs how psychological warfare, information operations, hybrid warfare and, most recently, cognitive warfare have been articulated in response to successive media and technological environments, from radio and leaflets to satellite broadcasting, social media platforms and artificial intelligence (Taylor 2003; Hoffman 2007; Rid 2020; Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili 2019, 2023). Conceptually, it offers a historically grounded definition of cognitive warfare that emphasizes both continuity and rupture: continuity in the long-standing ambition to shape perceptions, emotions and beliefs for strategic purposes, and rupture in the unprecedented fusion of digital platforms, datafication and AI-enabled personalization (NATO 2021; Zuboff 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025a). In doing so, the article speaks to ongoing discussions in political, intellectual and technological history about the changing relationship between war, information and the human mind.

The article is structured as follows.

Section 2 outlines the conceptual and methodological framework, clarifying how the terms psychological warfare, propaganda, information operations, hybrid warfare, and cognitive warfare are used.

Section 3 traces the historical development of psychological warfare and propaganda from the Second World War to the late Cold War, with particular attention to broadcasting and other mass-media tools.

Section 4 discusses the emergence of hybrid warfare and information control after 1990, focusing on Russian operations in Ukraine and beyond.

Section 5 analyses the impact of digital platforms and AI on contemporary cognitive warfare, including issues such as disinformation, micro-targeting, and the governance of algorithmic information environments.

Section 6 offers a historically grounded definition of cognitive warfare and reflects on its implications for political and intellectual history, security studies, and international law.

Section 7 concludes by suggesting directions for future research on the long-term transformation of the cognitive dimension of conflict.

2. Conceptual and Methodological Framework

2.1. Clarifying Overlapping Concepts

This section clarifies the key concepts underpinning the analysis and outlines the methodological choices guiding the article. The terminological field surrounding psychological warfare, propaganda, information operations, hybrid warfare and cognitive warfare is notoriously fluid and contested, with overlapping usages in doctrine, policy and academic research (Rid 2020; Marsili 2023, 2025a). Building on classic studies of propaganda and psychological operations and on recent work on hybrid and cognitive warfare—including contributions that systematise the relationship between cyber, information and cognitive domains (Marsili 2019, 2023, 2025a)—the discussion adopts a historically sensitive, genealogical approach rather than a search for fixed, exhaustive definitions.

Modern psychological warfare (psywar) and psychological operations (PSYOP) are generally understood as the planned use of communication and other measures to influence the attitudes, emotions and behaviour of target audiences in support of military or political objectives (Taylor 2003; US DoD 1998). During the Second World War and the Cold War, psywar was associated with leaflets, radio broadcasts, rumours, deception and other instruments aimed at undermining enemy morale or bolstering friendly support (Cull 2008; Taylor 2003). In the present article, psychological warfare is used as an umbrella term for these twentieth-century military and political practices, while psychological operations refers more specifically to their institutionalised doctrinal form in late twentieth-century Western armed forces.

The notion of propaganda predates psychological warfare and is both broader and more ambiguous. Following a widely cited definition, propaganda can be understood as a deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions and direct behaviour in ways that serve the purposes of the propagandist (Jowett and O’Donnell 2018). This definition emphasises intentionality, strategic planning and the management of information and symbols, and it accommodates both state and non-state actors. In what follows, propaganda designates a mode of communication that can occur in war and peace, while psychological warfare denotes its specific militarised configuration during major conflicts of the twentieth century.

With the rise of digital networks and the growing importance of command, control, communications and intelligence systems, Western militaries in the 1990s increasingly adopted the vocabulary of information operations and information warfare. These terms refer to coordinated actions that affect an adversary’s information and information systems while protecting one’s own, combining electronic warfare, computer network operations, psychological operations and deception in a single framework (Arquilla and Ronfeldt 1997; US DoD 1998). The term information operations is used here in this doctrinal sense, to capture the post-Cold War integration of psyops and technical measures targeting the information environment.

The concept of hybrid warfare, associated above all with the work of Frank Hoffman (2007), describes conflicts in which state and non-state actors combine conventional military force, irregular tactics, terrorism, criminal activities and information campaigns in a flexible and adaptive manner. Hybrid warfare blurs the boundaries between war and peace and between internal and external security, making attribution and escalation management more difficult (Hoffman 2007; Marsili 2019, 2023). In this article, hybrid warfare is treated as an intermediate step between twentieth-century psychological warfare and the more recent cognitive warfare debate, marking a phase in which information operations are embedded in a broader multi-domain strategy. Empirical analyses of cyber and information operations against critical infrastructures and within the European security architecture have highlighted how such hybrid tactics operate in the grey zone below the threshold of declared war (Marsili 2019, 2021, 2023).

More recently, NATO’s Allied Command Transformation and related expert groups have advanced the notion of cognitive warfare to describe activities that target the human mind as a distinct domain of operations alongside land, sea, air, space and cyber (NATO 2021). NATO-linked research has defined cognitive warfare as a convergence of cyber-psychology, weaponised neuroscience and cyber-influence aimed at provoking alterations in how individuals and groups perceive and interpret the world (NATO 2021; Marsili 2023). Critical analyses have warned that the proliferation of new labels—cyber, information, hybrid, cognitive warfare—risks conceptual inflation and misunderstandings, and have proposed more systematic mappings of similarities and differences, with particular attention to the legal and strategic implications and to extensions into immersive environments such as the metaverse (Marsili 2023, 2025a).

In light of this debate, the present article adopts a relatively narrow working definition. Cognitive warfare is treated as a set of practices and strategies that seek to shape, disrupt or exploit cognitive processes—attention, memory, emotion, reasoning and decision-making—by manipulating information environments, often through digital platforms, data analytics and AI-enhanced tools. While cognitive warfare builds on earlier forms of propaganda and psychological warfare, it differs from them by the centrality of personalised, data-driven and potentially continuous interventions in individuals’ information diets, and by the increasing role of cognitive science and behavioural insights in the design of such interventions (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025a).

The literature on computational propaganda examines how algorithms, automation and data are used to manage and distribute political messages, including misleading or manipulative content, over social media networks (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Woolley and Howard 2018). Although computational propaganda is not treated here as a synonym for cognitive warfare, the concept is crucial for understanding the technical means by which contemporary influence operations are implemented. Computational propaganda is therefore considered as one important mechanism through which cognitive warfare can be conducted in digital environments.

Taken together, these conceptual clarifications situate cognitive warfare within a broader family of practices rather than as a self-standing novelty. They also show that terminological shifts often respond to changes in technology, doctrine and political context, which reinforces the need for a historical and genealogical approach.

2.2. A Historical–Genealogical Approach to Cognitive Warfare

Methodologically, the article combines conceptual history with a genealogy of military and political practices. Drawing on Reinhart Koselleck’s work on Begriffsgeschichte, concepts such as “propaganda”, “psychological warfare”, “information operations”, “hybrid warfare” and “cognitive warfare” are treated as historically situated semantic fields whose meanings change over time in response to political conflicts, technological innovations and institutional struggles (Koselleck 2004).

Rather than searching for a single, timeless definition, the analysis asks how and why certain terms emerge, gain prominence, overlap or fall into disuse. This perspective makes it possible to observe, for example, how the language of psychological warfare gradually gives way to that of information operations in the 1990s, or how the recent emphasis on cognition reflects both anxieties about disinformation and advances in AI, data analytics and neuroscience (Marsili 2023, 2025a).

This conceptual analysis is combined with a genealogical reconstruction of practices across three historical phases:

Twentieth-century psychological warfare and propaganda, from the Second World War to the late Cold War, where mass media and ideological confrontation structured campaigns targeting the morale and beliefs of domestic and foreign audiences (Taylor 2003; Cull 2008).

Post-Cold War hybrid and information warfare, where information operations, cyber activities and other non-kinetic tools are integrated into broader hybrid strategies, as illustrated by Russian campaigns in Ukraine and against Western political processes (Galeotti 2016; Marsili 2021, 2023).

Contemporary digital and AI-enabled cognitive warfare, characterised by social media platforms, big-data analytics, bots, deepfakes and immersive environments that enable finely targeted and persistent manipulation of information environments (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025a, 2025b).

This historical–genealogical perspective draws on research that has highlighted the continuity between hybrid warfare and newer cognitive warfare discourses, stressing the progressive centrality of the cognitive dimension in security thinking (Marsili 2019, 2023, 2025a). It provides the analytical backbone for the historically grounded definition of cognitive warfare proposed in

Section 6.

2.3. Case Selection, Sources and Limitations

The article does not aim to offer an exhaustive empirical mapping of all relevant operations. Instead, it employs illustrative comparative case studies to highlight patterns of continuity and change across the three phases outlined above. The main empirical foci are:

• Second World War and early Cold War psychological warfare, including Allied and Axis propaganda and early Western psywar institutions and campaigns, with particular attention to the use of radio broadcasting and leaflets (Taylor 2003; Cull 2008).

• Cold War “wars of ideas” and psychological operations, especially in Europe, where broadcasting initiatives such as Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty and other information activities targeted both Eastern Bloc and Western publics (Puddington 2000; Johnson 2010).

• Post-2014 Russian hybrid campaigns, notably in Ukraine and in the context of interference in Western electoral processes, as paradigmatic examples of integrated information, cyber and political operations in the grey zone (Galeotti 2016; Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili 2021, 2023).

• Recent digital and AI-mediated operations, including disinformation campaigns and computational propaganda over social media platforms, which illustrate the practical mechanisms of contemporary cognitive warfare (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Woolley and Howard 2018; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025b).

The sources combine:

• Official documents and doctrinal publications, including NATO materials on information, hybrid and cognitive warfare (NATO 2010, 2016, 2021).

• Academic monographs and articles on propaganda, psychological warfare, hybrid warfare, computational propaganda and conceptual history (Jowett and O’Donnell 2018; Hoffman 2007; Rid 2020; Koselleck 2004).

• Policy reports and analytical papers from think tanks and research institutes on contemporary information and hybrid threats (European Commission 2018; Bradshaw and Howard 2019).

• Studies on cyber, information and cognitive warfare, as well as on cybersecurity and critical infrastructures, which provide both empirical material and conceptual refinements (Marsili 2019, 2020, 2021, 2023, 2025a, 2025b; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024).

This combination of sources is appropriate for an article whose primary aim is conceptual and historical rather than statistical or evaluative. Nevertheless, it entails several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, much of the archival material on psychological operations remains classified or only partially accessible, which constrains the depth of empirical reconstruction, especially for recent operations. Second, analyses of contemporary campaigns often rely on open-source investigations and secondary reports, which may be incomplete or contested. Third, debates on cognitive warfare are evolving rapidly within NATO and national institutions, and any interpretation of current doctrinal trends can only be provisional (NATO 2021; Marsili 2023, 2025a).

Rather than attempting to overcome these limitations through speculative claims, the discussion adopts a cautious, historically informed interpretation. The objective is not to adjudicate the effectiveness of specific operations, but to show how changing media ecologies, doctrinal frameworks and technological capabilities have progressively reconfigured the “battlefield of the mind” from psychological warfare to cognitive warfare. This, in turn, provides the basis for the analytically precise and historically grounded definition of cognitive warfare advanced in

Section 6.

3. From Psychological Warfare to Information Operations (1930s–1990s)

This section traces the emergence and consolidation of modern psychological warfare from the 1930s to the end of the Cold War, and shows how, by the 1990s, doctrinal thinking increasingly shifted towards the broader notion of information operations. It highlights three related developments: the mobilisation of mass propaganda in total war; the institutionalisation of psychological warfare during the Cold War “wars of ideas”; and the gradual integration of psychological techniques into technologically sophisticated systems of information control and management (Taylor 2003; Cull 2008; Rid 2020).

3.1. The Origins of Modern Psychological Warfare

Although attempts to influence the minds of opponents are as old as war itself, modern psychological warfare is closely associated with the rise of mass politics and mass communication in the first half of the twentieth century. The spread of literacy, the consolidation of national public spheres, and the development of radio, cinema, and the illustrated press provided states with unprecedented tools to reach large and diverse audiences (Thompson 1995; Taylor 2003).

During the Second World War, the mobilisation of propaganda became a central component of total war. All major belligerents created specialised institutions and experimented with techniques designed to strengthen domestic morale, demonise the enemy, and influence neutral or occupied populations (Taylor 2003; Welch and Welsh 1995). In the United Kingdom, for example, the Ministry of Information coordinated domestic and foreign propaganda, while the clandestine Political Warfare Executive (PWE) orchestrated “black” and “grey” operations aimed at Axis troops and civilians (Cruickshank 1977). In the United States, the Office of War Information (OWI) and the Psychological Warfare Division of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (PWD/SHAEF) combined broadcast, print, and leaflet campaigns in support of military operations (Cull 2008). Nazi Germany and imperial Japan likewise developed elaborate propaganda systems centred on radio, film, and print, integrating them into broader projects of ideological mobilisation and repression (Herf 2006; Yoshimi 2006).

Several features of these wartime experiences would prove enduring. Psychological warfare was increasingly conceived as a planned, quasi-scientific enterprise, informed by emerging fields such as social psychology, public opinion research, and communication studies (Lasswell 1927; Doob 1949). It involved a combination of overt messaging (posters, newsreels, speeches, radio programmes) and covert activities (rumour campaigns, forgeries, deceptive broadcasts). It also underscored the importance of tailoring messages to specific audiences, experimenting with segmentations along national, class, ideological, or military lines (Taylor 2003). These elements laid the foundations for post-war doctrines of psychological operations and for later debates on the “hearts and minds” of populations in conflicts from Malaya to Vietnam (Komer 1970; Newsinger 2002).

3.2. Institutionalising Psychological Warfare in the Early Cold War

The onset of the Cold War transformed psychological warfare from an ad hoc wartime practice into a permanent feature of strategic competition. The bipolar confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union was not only a military and nuclear rivalry, but also an ideological struggle over the political and economic organisation of societies (Gaddis 2005). In this context, psychological warfare promised to exert influence without resorting to direct armed confrontation, and to exploit perceived vulnerabilities in the opponent’s political system and social cohesion (Osgood 2006).

In the late 1940s and 1950s, the United States created a complex array of institutions and coordinating bodies to manage psychological warfare and related activities, including the Psychological Strategy Board and the Operations Coordinating Board, alongside specialised psychological operations units within the armed forces (Osgood 2006; Snyder 2010). Parallel developments occurred in the United Kingdom, France, and other Western states, often in close coordination with intelligence agencies and diplomatic services (Lucas 2014). On the Soviet side, propaganda and agitation (agitprop) were integrated into party structures, state-controlled media, and international front organisations, projecting a competing vision of peace, decolonisation, and socialism (Hollander 1981).

Psychological warfare in this period was framed as a way to win “hearts and minds” at a time when nuclear deterrence limited the scope for conventional war. It included efforts to influence foreign elites and publics, but also to manage domestic opinion in support of alliance commitments, nuclear policies, and overseas interventions (Komer 1970; Newsinger 2002). Psychological operations became increasingly professionalised and bureaucratised, with doctrinal manuals, training programmes, and specialised units. At the same time, the secrecy surrounding many of these activities generated recurrent controversies, raising questions about the legitimacy and effectiveness of psychological warfare in democratic societies (Rid 2020; Marsili 2020).

3.3. Broadcasting and the “Wars of Ideas”

Radio broadcasting played a particularly prominent role in Cold War psychological warfare. Long-range radio made it possible to reach audiences behind the Iron Curtain and in the Global South, circumventing censorship and information controls (Puddington 2000; Nelson 1997). Stations such as the BBC World Service, Voice of America, Radio Free Europe (RFE), and Radio Liberty (RL) became emblematic tools of Western “public diplomacy” and psywar, while Soviet and Eastern Bloc broadcasters promoted competing narratives and counter-propaganda (Johnson 2010; Cull 2008).

The “wars of ideas” were fought not only through hostile messages but also through claims to credibility and professionalism. Western broadcasters typically presented themselves as sources of “truthful” information in contrast to allegedly censored or distorted domestic media in communist states, even as some operations were covertly funded and coordinated by intelligence services (Puddington 2000; Snyder 2010). Programming combined news, cultural content, and carefully designed political messages, often targeting specific linguistic and national audiences.

Broadcasting campaigns also illustrated the ambivalent status of psychological warfare at the intersection of propaganda, diplomacy, and journalism. They were part of a strategic effort to erode the legitimacy of rival regimes and to foster dissent, while simultaneously contributing to the normalisation of transnational media flows and to the emergence of what later scholarship would conceptualise as global public spheres. This ambiguity continues to inform debates on the boundary between legitimate public communication and manipulative influence operations, a theme that re-emerges in contemporary discussions on international broadcasting, foreign media, and platform regulation (Marsili 2020, 2025b).

3.4. Late Cold War Transformations: From Psywar to the “Information Battlefield”

By the 1970s and 1980s, technological innovation and changing strategic conditions began to reshape the toolkit and vocabulary of psychological warfare. The spread of television, the rise of transnational news agencies, and, eventually, the development of satellite communications and 24-hour news channels altered how conflicts were represented and perceived (Thompson 1995; Hoskins and O’Loughlin 2010). The so-called “CNN effect” fuelled concerns among policymakers and military planners about the impact of live media coverage on public opinion and crisis decision-making (Robinson 2002).

At the same time, advances in computing and telecommunications laid the groundwork for what military thinkers would soon describe as the “information revolution” in warfare. Command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems became central to planning and conducting operations. Electronic warfare, signals intelligence, and early forms of computer network operations highlighted the strategic value of controlling not only the content of information, but also the channels and infrastructures through which it flowed (Libicki 1995; Arquilla and Ronfeldt 1997).

Psychological operations did not disappear in this context; rather, they were increasingly reframed as one component of a broader “information battlefield”. Doctrinal documents started to emphasise the need to coordinate psychological activities with deception, electronic warfare, and other capabilities affecting the adversary’s decision-making cycle (US DoD 1998). In the late Cold War and immediate post-Cold War conflicts, such as the 1991 Gulf War, these ideas were tested in practice, with extensive use of leaflet drops, radio broadcasts, and media management alongside precision strikes on communication nodes and command centres (Freedman and Karsh 1993; Taylor 2003).

3.5. The Emergence of Information Operations in the 1990s

The end of the Cold War and the rapid spread of digital networks in the 1990s accelerated the conceptual shift towards information operations. In Western military doctrine, particularly within the United States and NATO, information operations came to designate a coordinated set of actions designed to affect adversary information and information systems while protecting one’s own (US DoD 1998; NATO 1999). Psychological operations were now explicitly combined with electronic warfare, computer network attack and defence, operational security, and military deception under a single overarching framework.

This doctrinal evolution reflected several intertwined developments. The Gulf War and subsequent peacekeeping and intervention operations appeared to demonstrate the growing importance of information superiority and media management, reinforcing the idea that controlling perceptions, narratives, and information flows was essential to achieving strategic objectives (Freedman and Karsh 1993; Hoskins and O’Loughlin 2010). The expanding civilian use of the internet, mobile communications, and satellite broadcasting blurred the boundary between civilian and military information infrastructures, raising new vulnerabilities and opportunities for influence (Libicki 1995; Arquilla and Ronfeldt 1997). The relative decline of the existential ideological confrontation of the Cold War shifted attention towards regional crises, humanitarian interventions, and peace support operations, where public opinion at home and abroad became a central constraint (Robinson 2002; Marsili 2019).

By the late 1990s, information operations had become a key organising concept in Western doctrine, even if practical implementation remained uneven and sometimes contested (Rid 2020). Psychological warfare and propaganda did not vanish; instead, they were subsumed and partially redefined within a wider understanding of conflict as a struggle over information and perception. This created the conceptual bridge to the early twenty-first century debates on hybrid warfare and, more recently, on cognitive warfare (Hoffman 2007; Marsili 2019, 2023).

From this perspective, the contemporary focus on the “cognitive domain” appears less as a radical departure than as the latest phase in a long process whereby militaries and political actors have progressively expanded their view of the battlespace to include media systems, information infrastructures, and, ultimately, the minds of individuals and societies (Rid 2020; Marsili 2023, 2025a). The next section builds on this insight to examine how post-Cold War hybrid warfare further blurred the boundary between kinetic operations, information campaigns, and political subversion, setting the stage for the emergence of cognitive warfare as a distinct label in the 2010s.

4. Hybrid Warfare and Information Control after the Cold War

The end of the Cold War did not bring about the “end of history”, but rather inaugurated a period in which conflicts increasingly shifted towards ambiguous legal spaces and below-threshold confrontations. In this context, the idea of hybrid warfare emerged as a way to conceptualise strategies that mix conventional and unconventional means, kinetic and non-kinetic instruments, military and non-military tools. Information and communication occupy a central place in this configuration: hybrid strategies systematically target media ecosystems, regulatory frameworks, and social cohesion, thereby turning information control into a key dimension of post-Cold War conflict (Hoffman 2007; Marsili 2019, 2023).

4.1. From the “Revolution in Military Affairs” to Hybrid Warfare

In the 1990s, debates on the “Revolution in Military Affairs” (RMA) framed digital technologies, precision weapons, and networked command-and-control as transformative factors that would reshape the conduct of war (Owens 1995; Freedman 1998). Under the influence of these debates, Western armed forces invested heavily in surveillance, targeting, and communication capabilities, viewing information superiority as a decisive advantage on the battlefield (Arquilla and Ronfeldt 1997; Libicki 1995). At the doctrinal level, this orientation was captured in concepts such as “information operations” and “network-centric warfare”, which integrated psychological operations, electronic warfare, deception, and cyber measures under a unified heading (US DoD 1998).

The experience of peacekeeping and stabilisation missions in the Balkans, Afghanistan, and Iraq, however, showed that technological superiority was not sufficient to secure political outcomes. Insurgencies, terrorist groups, and non-state actors learned to exploit the constraints faced by Western democracies, using asymmetric tactics and leveraging media visibility to influence public opinion and erode domestic support for interventions (Hoskins and O’Loughlin 2010; Robinson 2002). These dynamics foreshadowed some of the key features later associated with hybrid warfare: the blurring of front lines, the centrality of legitimacy and narratives, and the strategic use of ambiguity.

Against this backdrop, the concept of hybrid warfare, popularised by Frank Hoffman (2007), gained prominence. Hybrid warfare described adversaries that combined the lethality of state conflict with the protracted fervour of irregular warfare and that extensively exploited information operations, psychological tactics, and legal grey zones. For European states and NATO, this conceptual framework provided a vocabulary to discuss new forms of coercion and destabilisation that seemed to circumvent traditional deterrence and collective defence mechanisms (NATO 2010; Marsili 2019).

4.2. Russia as a Paradigmatic Hybrid Actor

Russia’s behaviour in its near abroad and towards Western democracies has frequently been cited as the paradigmatic example of hybrid warfare. From the 2007 cyber-attacks against Estonia to the 2008 war in Georgia, Russian actions combined diplomatic pressure, energy leverage, military force, cyber operations, and intensive propaganda campaigns (Galeotti 2016; Giles 2016). The 2014 annexation of Crimea and the conflict in Eastern Ukraine further consolidated this image: “little green men”, deniable armed groups, information warfare, and legal arguments about self-determination were orchestrated to create confusion, delay responses, and shape perceptions at home and abroad (Galeotti 2016; Kofman and Rojansky 2015).

Analyses of Russian strategies have highlighted how these approaches systematically exploit normative ambiguities in international law and the internal vulnerabilities of liberal democracies, operating in a “grey zone” below the threshold of overt armed conflict (Marsili 2019, 2021, 2023). Rather than relying solely on kinetic force, these strategies use disinformation, selective leaks, media manipulation, and support for fringe political actors to fragment public opinion and undermine trust in institutions. Disputes over the interpretation of events—for instance, whether a particular intervention constitutes “self-defence”, “peacekeeping”, or “aggression”—are integral to hybrid warfare, as they shape the legal and political space in which responses can be framed (Marsili 2019, 2023).

Russian influence operations targeting elections and referendums in Western states illustrate another dimension of hybrid warfare: the use of information tools to interfere directly in domestic political processes. Investigations into campaigns around the 2016 US presidential election, the Brexit referendum, and various European electoral contests have highlighted the role of state-linked media, online trolls, bots, and data-driven targeting in amplifying polarising narratives and sowing distrust (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Rid 2020). These operations blur the line between foreign propaganda, domestic political communication, and covert influence, raising complex questions for regulation and attribution (Marsili 2023, 2025a).

4.3. Information Control, Regulatory Responses, and Human Rights

Hybrid warfare has not only highlighted the offensive use of information tools, but has also pushed states and international organisations to reconsider how they regulate and protect their own information environments. Concerns about disinformation, foreign influence, and platform power have triggered a wave of regulatory and policy initiatives aimed at strengthening resilience against hybrid threats (European Commission 2018; NATO 2016). These include strategic communication units, counter-disinformation task forces, and new legal frameworks for online platforms.

Studies of the COVID-19 infodemic and of the regulation of digital platforms have shown how such measures often sit at the intersection of security, public health, and fundamental rights (Marsili 2020, 2025a). On the one hand, restrictions on harmful content, requirements for transparency, and obligations for platforms to remove or downgrade disinformation are presented as necessary tools to protect democratic processes and public safety. On the other hand, they risk entrenching new forms of censorship, chilling effects, and discretionary power over speech, especially when definitions of “disinformation” and “harm” remain vague or politically contested.

Hybrid warfare thus operates not only through overtly hostile actions, but also through the ways in which states respond to perceived threats. Measures adopted in the name of resilience can themselves reconfigure the boundary between legitimate dissent and subversion, and between information policy and security policy (Marsili 2023, 2025b). In this sense, hybrid warfare can be understood as a catalyst that accelerates broader transformations in the governance of information, including increased surveillance, data collection, and algorithmic moderation.

The energy transition and debates on climate policy provide a further example of how hybrid tactics and information control intersect. Cognitive operations and information campaigns around energy security, sanctions, and environmental policies can be used to polarise societies and delegitimise regulatory measures, while regulatory responses in turn reshape access to information and public debate (Marsili 2025a). This mutual entanglement of hybrid threats, regulatory reactions, and human rights concerns anticipates some of the challenges explored later in the article under the label of cognitive warfare.

4.4. Hybrid Warfare as a Bridge to the Cognitive Domain

From the standpoint of the present analysis, hybrid warfare is not only a phenomenon of empirical interest but also a conceptual bridge to the contemporary debate on cognitive warfare. Hybrid strategies foreground the centrality of perception, legitimacy, and narrative in modern conflict: the success of an operation depends not only on physical outcomes, but also on how events are interpreted by domestic and international audiences (Hoffman 2007; Rid 2020). Information campaigns are designed to shape these interpretations: to portray interventions as defensive or humanitarian, to frame opponents as aggressors or terrorists, and to normalise certain policy choices as inevitable or rational.

Recent scholarship has argued that hybrid warfare can be seen as a phase in which information operations are increasingly focused on the cognitive dimension, but without yet fully articulating cognition as a distinct domain of operations (Marsili 2019, 2023). Influence remains largely framed in terms of public opinion, strategic communication, and propaganda, even as the tools deployed—social media, bots, micro-targeting—begin to operate at a more granular, personalised level than traditional broadcasting. The move from hybrid to cognitive warfare therefore involves, at least in part, a shift in how the target is conceptualised: from “populations” and “audiences” to the cognitive processes of individuals and groups.

This shift is reinforced by the growing role of data analytics, behavioural science, and artificial intelligence in the design of influence campaigns. The combination of large-scale data collection, algorithmic profiling, and automated messaging enables new forms of micro-targeting that tailor content to specific psychological traits, preferences, and vulnerabilities (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025a). In this context, the “hybrid” toolkit is increasingly oriented towards manipulating attention, emotion, and decision-making rather than merely providing alternative narratives.

Hybrid warfare also familiarises policymakers and military planners with the idea that conflict takes place across multiple, overlapping domains—military, economic, informational, legal, and political—and that advantages can be gained by exploiting seams between them (NATO 2016; Marsili 2019). This multi-domain perspective provides fertile ground for the conceptual move towards a “cognitive domain” alongside land, sea, air, space, and cyber, as advocated in recent NATO discussions (NATO 2021). The language of domains legitimises the development of dedicated capabilities, doctrines, and institutional arrangements, thereby consolidating cognitive warfare as a recognised category of planning and analysis.

In this light, the contemporary discourse on cognitive warfare appears both as a continuation and as a reframing of hybrid warfare. It continues the emphasis on ambiguity, below-threshold operations, and integrated toolkits, but reframes the ultimate objective as the systematic shaping of cognition rather than merely the control of narratives or information infrastructures (Marsili 2023, 2025a). The next section builds on this insight by examining how digital platforms, computational propaganda, and AI-enabled tools intensify these trends, making cognitive warfare a distinctive lens through which to interpret the evolution of conflict in the early twenty-first century.

5. AI, Platforms, and the Intensification of Cognitive Warfare

The rise of digital platforms and artificial intelligence has profoundly transformed the conditions under which influence operations are conceived and conducted. Building on the hybrid configurations discussed in the previous section, contemporary cognitive warfare operates within an environment structured by social media platforms, algorithmic curation, data extraction and automated content production. In this environment, the capacity to shape perceptions and decision-making increasingly depends on control over digital infrastructures, access to behavioural data and the ability to deploy AI-enabled tools at scale (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Zuboff 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024).

5.1. Platforms as Infrastructures of Cognitive Exposure

Digital platforms are not merely neutral channels for information exchange, but socio-technical infrastructures that shape how information is produced, ranked and circulated. Social media newsfeeds, search engines and video-sharing services rely on algorithmic recommendation systems that prioritise content according to opaque criteria, often optimised for engagement and advertising revenue rather than for accuracy or democratic deliberation (Gillespie 2018; Napoli 2019). This architecture creates highly asymmetrical relationships between platform operators, content producers and users, as only the former have systematic visibility on flows of data and the behavioural effects of ranking decisions (Zuboff 2019).

From the perspective of cognitive warfare, these infrastructures generate distinctive forms of cognitive exposure. Users are continuously exposed to streams of personalised content, notifications and prompts that compete for attention and shape what is perceived as salient or credible. The combination of algorithmic curation and social signalling (likes, shares, comments) produces feedback loops in which emotionally charged, polarising or sensationalist content tends to be amplified (Tufekci 2017; Bradshaw and Howard 2019). This dynamic can be exploited by state and non-state actors seeking to disseminate disinformation, conspiracy theories or divisive narratives, and by malicious campaigns that imitate organic content to evade detection.

Analyses of disinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic, electoral cycles and geopolitical crises have repeatedly shown how platform logics can facilitate the viral spread of misleading or manipulative content, even when such content originates from relatively marginal actors (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili 2020, 2023, 2025a). The resulting environment is characterised less by the absence of information than by an overabundance of competing claims, in which users must navigate uncertainty, distrust and fatigue. Cognitive warfare in this context seeks not only to persuade, but also to overwhelm, confuse and fragment, thereby undermining shared reference points for public debate.

5.2. Computational Propaganda and the Automation of Influence

The concept of computational propaganda captures the use of algorithms, automation and big data to manage and distribute political messages over digital networks (Woolley and Howard 2018; Bradshaw and Howard 2019). Automated accounts (“bots”), coordinated inauthentic behaviour, troll farms and targeted advertising campaigns allow relatively small groups of operators to generate the appearance of widespread support or opposition, to harass opponents and to steer online conversations.

These techniques do not operate in a vacuum, but are layered on top of existing platform logics. Bots can amplify selected hashtags or links, making them more visible within ranking systems; coordinated networks of accounts can simulate grassroots movements or manipulate trending lists; targeted advertising systems can deliver tailored messages to narrowly defined segments of the population. The boundaries between overt political communication, covert influence and ordinary marketing practices are often blurred, especially when political actors use the same tools as commercial advertisers (Tufekci 2017; Bradshaw and Howard 2019).

From a cognitive warfare perspective, computational propaganda intensifies several tendencies already visible in earlier hybrid strategies. First, it increases the speed and scale at which influence operations can be launched, as automated systems can generate and disseminate large volumes of content, adjust messages in real time and exploit emerging events.

Second, it enhances plausible deniability: attribution is complicated by the use of intermediaries, proxies and commercial infrastructure, making it difficult to distinguish between domestic mobilisation and foreign interference (Rid 2020; Marsili 2023). Third, it enables fine-grained targeting of messages based on inferred preferences, attitudes and vulnerabilities, thereby moving beyond mass broadcasting towards more individualised forms of influence (Zuboff 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024).

Empirical research on foreign influence campaigns, including those associated with Russia, has documented extensive use of computational propaganda techniques in relation to elections, referendums and contentious policy debates (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Rid 2020; Marsili 2021, 2023). These campaigns often combine overt messaging through state-sponsored media with covert online operations, producing a multilayered information environment in which the same narratives circulate through different channels and formats. The objective is less to convince all users of a specific position than to foster distrust, cynicism and polarisation, thereby weakening the cognitive and social cohesion of targeted societies (Rid 2020; Marsili 2023).

5.3. AI-Generated Content, Deepfakes and Personalisation

Recent advances in machine learning have further expanded the repertoire of tools available for cognitive warfare. Generative AI systems can produce text, images, audio and video that closely resemble human-generated content, lowering the cost of creating persuasive or deceptive material at scale (Brundage et al. 2018; DiResta 2021). Large language models can generate tailored narratives, comments or responses; image and video generators can fabricate photorealistic scenes and faces; voice synthesis can imitate public figures or trusted interlocutors.

Deepfakes and synthetic media exemplify the potential of these tools to erode trust in audiovisual evidence. Fabricated videos can be used to discredit political leaders, incite intergroup hostility or fabricate incidents that may influence crisis decision-making (Chesney and Citron 2019). Even when specific deepfakes are detected or debunked, their existence contributes to a broader “liar’s dividend”, whereby genuine recordings can be dismissed as fake and the epistemic status of audiovisual documentation is weakened (Chesney and Citron 2019; Rid 2020).

AI-generated content also enhances personalisation. When combined with behavioural data and profiling techniques, generative models can be used to tailor messages to specific psychological traits or emotional states, adjusting tone, framing and content to maximise persuasive impact (Brundage et al. 2018; Zuboff 2019). This capability aligns closely with the definition of cognitive warfare as the targeting of attention, emotion and decision-making processes. Instead of broadcasting uniform messages to large audiences, influence operators can experiment with multiple variants and automatically select those that elicit desired reactions from different users or segments.

Analyses of emerging AI governance frameworks have highlighted the difficulty of regulating these practices, given the rapid pace of technological development, the global reach of platforms and the dual-use nature of many AI tools (Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025b). Measures designed to detect or label AI-generated content, to restrict certain uses or to ensure transparency may mitigate some risks, but can also be circumvented or weaponised, for instance by falsely labelling authentic content as synthetic. In this sense, the diffusion of AI-enabled manipulation techniques further complicates regulatory responses to cognitive warfare.

5.4. Immersive Environments and the Expansion of the Cognitive Battlespace

The emergence of immersive and mixed-reality environments adds a further layer to these dynamics. Virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and the broader constellation of platforms described under the label metaverse integrate physical and digital experiences, creating spaces in which users interact through avatars, objects and environments that can be persistently modified and monitored (Marsili 2025a). In such environments, the boundaries between information, experience and behaviour become increasingly porous.

Immersive settings offer new opportunities for cognitive targeting. Spatial arrangements, visual and auditory cues, and interaction mechanics can all be designed to elicit specific emotional responses, to reinforce certain narratives or to normalise particular hierarchies and roles. The integration of biometric sensors and motion tracking can provide additional data on users’ reactions, enabling continuous adaptation of content and environments (Slater and Sanchez-Vives 2016). In principle, this combination allows for highly granular experimentation on how different stimuli affect perception, memory and decision-making, with direct implications for cognitive warfare.

These developments resonate with earlier concerns about the role of media environments in shaping subjectivities, but extend them into a context where the distinction between representation and participation is attenuated. Rather than simply consuming information, users inhabit designed worlds that can be oriented towards commercial, political or strategic goals (Marsili 2025a). When such environments are controlled by a small number of corporations or state-linked actors, questions of access, moderation and design acquire a clear geopolitical and security dimension.

5.5. From Information Operations to Cognitive Environments

Taken together, the dynamics outlined in this section suggest that the contemporary intensification of cognitive warfare is not reducible to the deployment of new tools, but involves a broader transformation in how information environments and cognitive processes are intertwined. Digital platforms, computational propaganda, AI-generated content and immersive media contribute to the emergence of cognitive environments in which attention, emotion and reasoning are continuously monitored, predicted and nudged (Zuboff 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025a, 2025b).

This transformation accentuates three structural features already present in earlier phases of psychological and hybrid warfare. First, continuity is reinforced: influence operations are no longer limited to discrete campaigns, but can be sustained over long periods, with constant adjustments based on real-time data. Second, opacity increases: users have limited insight into how content is prioritised, how profiles are constructed and how their data are used, which complicates informed consent and accountability (Gillespie 2018; Napoli 2019). Third, entanglement deepens: commercial, political and strategic uses of the same infrastructures overlap, making it difficult to distinguish between ordinary platform operation, legitimate political mobilisation and hostile cognitive actions (Woolley and Howard 2018; Marsili 2023, 2025b).

In this context, the analytical shift from information operations to cognitive warfare captures more than a semantic innovation. It reflects the growing centrality of cognitive processes as both targets and resources within digital societies. Influence operations are no longer merely about transmitting messages or controlling channels, but about designing environments that shape how individuals and groups perceive, interpret and act upon the world. As subsequent sections argue, this shift raises significant challenges for existing legal and ethical frameworks, and calls for a historically grounded definition of cognitive warfare that can distinguish between continuity and qualitative change in the “battlefield of the mind” (Rid 2020; Marsili 2023, 2025a).

6. Toward a Historically Grounded Definition of Cognitive Warfare

The preceding sections have traced the evolution of practices and concepts from twentieth-century psychological warfare to post-Cold War hybrid warfare and the contemporary digital environment shaped by platforms and AI. On this basis, it is now possible to formulate a historically grounded definition of cognitive warfare that avoids both the temptation to treat it as a radically new phenomenon and the opposite tendency to dissolve it into older notions of propaganda or psychological operations.

6.1. Lines of Continuity: A Century of Targeting Minds

The first dimension to be emphasised is continuity. From the mobilisation of propaganda in the world wars to Cold War psychological operations and broadcasting campaigns, states and political movements have consistently sought to influence perceptions, emotions and beliefs in support of strategic objectives (Lasswell 1927; Taylor 2003; Cull 2008). Techniques such as demonisation of the enemy, appeals to fear and identity, selective disclosure and deception form a repertoire that has been repeatedly adapted to different media contexts (Jowett and O’Donnell 2018; Rid 2020).

Hybrid warfare and information operations extend these logics by integrating psychological techniques into broader strategies that combine military, economic, legal and informational tools (Hoffman 2007; Marsili 2019, 2023). Russian campaigns in Ukraine and Western democracies, for instance, rely on familiar methods—disinformation, propaganda, covert influence—deployed in a more flexible and multi-layered way (Galeotti 2016; Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili 2021, 2023). In this sense, cognitive warfare does not emerge on an empty canvas, but builds upon long-standing ambitions to shape what populations know, feel and consider legitimate.

6.2. Points of Rupture: Digital Infrastructures and Cognitive Environments

At the same time, the contemporary configuration exhibits features that justify speaking of a qualitative shift. The most significant ruptures concern infrastructures, datafication and personalisation.

First, digital platforms have become pervasive infrastructures of communication, sociality and information access (Gillespie 2018; Napoli 2019). Unlike earlier mass media, these systems rely on continuous data collection and algorithmic ranking, creating dynamic and personalised information environments. Control over these infrastructures entails a capacity to shape exposure, visibility and interaction patterns that far exceeds traditional gatekeeping by editors or broadcasters (Zuboff 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024).

Second, the datafication of social life allows for the construction of detailed behavioural profiles. Traces of online activity—clicks, likes, shares, location data—can be used to infer preferences, attitudes and vulnerabilities, providing a basis for targeted messaging and experimentation (Zuboff 2019; Woolley and Howard 2018). Influence is no longer limited to the content of messages, but extends to the design of environments in which certain reactions become more likely than others.

Third, advances in AI, particularly generative models, enable large-scale automation of content production and the tailoring of messages to specific individuals or micro-groups (Brundage et al. 2018; DiResta 2021). Deepfakes and synthetic media undermine trust in audiovisual evidence, while personalised narratives and interactive agents can be adapted in real time to users’ responses (Chesney and Citron 2019; Rid 2020). These developments bring the target of operations closer to cognitive processes themselves—attention, emotion, reasoning—rather than merely to expressed opinions.

Taken together, these ruptures justify speaking of cognitive environments in which perceptions, interpretations and choices are increasingly shaped by opaque, data-driven systems (Zuboff 2019; Marsili 2025a, 2025b). Cognitive warfare, in this sense, reflects a shift from the management of information flows to the engineering of environments that pre-structure how information is encountered and processed.

6.3. Defining Cognitive Warfare

In light of these continuities and ruptures, cognitive warfare can be defined as follows:

Cognitive warfare is the coordinated use of information, psychological techniques and technological infrastructures to shape, disrupt or exploit individual and collective cognitive processes—perception, attention, emotion, memory, reasoning and decision-making—in order to achieve strategic advantages in contexts of competition or conflict. It builds on earlier forms of propaganda, psychological and information warfare, but is characterised by the central role of digital platforms, datafication and AI-enabled personalisation in designing and manipulating the environments in which cognition takes place.

Several elements of this definition merit emphasis. First, the focus on processes rather than on isolated beliefs underscores that cognitive warfare targets how subjects come to know and evaluate the world, not merely what they explicitly think about specific issues (Marsili 2023, 2025a). For example, sustained exposure to contradictory or sensationalist information may be designed less to persuade of a particular claim than to induce distrust, fatigue or withdrawal from public debate.

Second, the notion of coordinated use signals that cognitive warfare involves strategic planning and integration of different instruments—media campaigns, platform manipulation, legal framing, economic pressure—rather than ad hoc or purely spontaneous phenomena (Hoffman 2007; Rid 2020; Marsili 2019, 2023). This does not imply that all effects are fully controllable, but highlights the intentional nature of the efforts deployed.

Third, the reference to technological infrastructures and environments captures the way in which cognitive warfare operates through the design and governance of platforms, algorithms and immersive systems (Gillespie 2018; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025a). The relevant question becomes not only who says what, but who controls the conditions under which anything can be said, seen or believed.

Finally, the definition situates cognitive warfare within a spectrum of practices that range from public diplomacy and strategic communication to covert manipulation and hostile influence. Distinguishing between these practices requires attention to criteria such as transparency, consent, respect for rights and the presence of coercive or deceptive elements (Marsili 2020, 2025b). Cognitive warfare, in this perspective, refers to the subset of activities that instrumentalise cognitive processes in ways that are incompatible with the principles of democratic self-government and human rights.

6.4. Conceptual Boundaries and Normative Implications

A historically grounded definition of cognitive warfare must also clarify its boundaries vis-à-vis neighbouring concepts. Three distinctions are particularly important.

First, cognitive warfare and propaganda overlap but are not identical. Propaganda, understood as systematic attempts to shape perceptions and behaviour, can be conducted in open, transparent ways and may be compatible with democratic deliberation under certain conditions (Jowett and O’Donnell 2018). Cognitive warfare, by contrast, is defined by the combination of strategic intent, exploitation of cognitive vulnerabilities and reliance on asymmetric control over infrastructures and data, often in covert or opaque forms.

Second, cognitive warfare is related to but broader than computational propaganda. The latter focuses on algorithmic and automated dissemination of political content on digital platforms (Woolley and Howard 2018). Cognitive warfare encompasses computational propaganda, but also includes the design of immersive environments, the use of legal and regulatory frames to shape information access and the targeting of emotions and identities in ways that extend beyond discrete messages (Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili 2023, 2025a).

Third, cognitive warfare should not be conflated with ordinary persuasion in pluralist societies. Democratic politics inevitably involves attempts to influence opinions and preferences; what distinguishes cognitive warfare is the systematic exploitation of structural asymmetries in information, data and technological control to intervene in cognitive processes without adequate transparency or safeguards (Marsili 2020, 2025b). This raises distinct normative concerns regarding autonomy, consent and the integrity of public reasoning.

These distinctions have implications for law and policy. Existing legal frameworks—ranging from the law of armed conflict and human rights law to platform regulation and data protection—were not designed with cognitive warfare in mind. The historical reconstruction offered in this article suggests that responses cannot rely solely on criminalisation or censorship, which risk reinforcing the very logics of control they seek to contain (Marsili 2023, 2025b). Instead, a combination of measures is needed, including greater transparency of infrastructures, robust protections for privacy and freedom of expression, and enhanced literacy about the cognitive dimensions of digital environments.

By situating cognitive warfare within a century-long trajectory of psychological and information warfare, hybrid strategies and digital transformation, the proposed definition aims to provide an analytical tool that can distinguish between continuity and qualitative change in the “battlefield of the mind” (Taylor 2003; Rid 2020; Marsili 2019, 2023, 2025a). This, in turn, offers a basis for future research on the historical evolution of cognitive conflict and on the normative principles that should govern the emerging cognitive domain.

7. Conclusions

The analysis developed in this article has examined cognitive warfare as the latest phase in a longer historical trajectory of efforts to influence minds in contexts of competition and conflict. Starting from twentieth-century propaganda and psychological warfare, moving through post-Cold War information and hybrid warfare, and arriving at contemporary platform- and AI-mediated influence operations, the discussion has highlighted both structural continuities and significant ruptures in the “battlefield of the mind” (Taylor 2003; Rid 2020; Marsili 2023).

On the side of continuity, the historical reconstruction has shown that many practices now associated with cognitive warfare—such as the use of fear and identity politics, the manipulation of information flows, the deployment of covert influence, and the targeting of morale and legitimacy—were already central to earlier forms of psychological and information warfare (Lasswell 1927; Taylor 2003; Cull 2008). The Cold War “wars of ideas” and the institutionalisation of psychological operations provided a durable repertoire of techniques and concepts that continue to inform contemporary strategies, even as the technological environment has changed (Puddington 2000; Osgood 2006; Johnson 2010).

On the side of rupture, the article has argued that the rise of digital platforms, datafication and AI-enabled personalisation has qualitatively transformed the conditions under which cognitive influence is exercised. Social media platforms and search engines function as infrastructures of cognitive exposure, structuring what users see and how information circulates (Gillespie 2018; Napoli 2019; Zuboff 2019). Computational propaganda techniques, including bots, troll networks and targeted advertising, automate and scale up influence operations while complicating attribution and detection (Woolley and Howard 2018; Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili 2021, 2023). Generative AI and immersive environments extend these dynamics by facilitating the production of synthetic media, deepfakes and personalised narratives, and by integrating cognitive targeting into the design of digital spaces themselves (Chesney and Citron 2019; DiResta 2021; Marsili 2025a, 2025b).

On this basis, the article has proposed a historically grounded definition of cognitive warfare as the coordinated use of information, psychological techniques and technological infrastructures to shape, disrupt or exploit cognitive processes—perception, attention, emotion, memory, reasoning and decision-making—in order to achieve strategic advantages. Cognitive warfare, thus defined, builds on earlier forms of propaganda and psychological and information warfare, but is characterised by the central role of digital platforms, datafication and AI-enabled personalisation in designing and manipulating the environments in which cognition takes place (Rid 2020; Bradshaw and Howard 2019; Marsili and Wróblewska-Jachna 2024; Marsili 2025a).

This definition has several implications for historical and conceptual research. First, it suggests that cognitive warfare should not be approached as a purely technological novelty. Rather, it must be situated within a century-long evolution in which new media and communication technologies—radio, television, satellite broadcasting, computer networks, social media, immersive environments—have been progressively integrated into military and political strategies of influence (Thompson 1995; Hoskins and O’Loughlin 2010; Marsili 2019, 2023). A historically informed perspective can therefore help resist both technological determinism and presentism, by showing how current practices reconfigure pre-existing logics rather than replacing them altogether.

Second, the analysis reinforces the need to distinguish cognitive warfare from neighbouring concepts. While overlapping with propaganda, computational propaganda and hybrid warfare, cognitive warfare refers specifically to practices that exploit structural asymmetries in data, infrastructures and technological control to intervene in cognitive processes in opaque or coercive ways (Woolley and Howard 2018; Marsili 2020, 2025b). This distinction is not merely semantic: it bears directly on how such practices are identified, monitored and addressed in legal and policy frameworks.

Third, the historical–genealogical approach adopted here underscores that conceptual innovations—such as the move from psychological warfare to information operations, hybrid warfare and cognitive warfare—are themselves part of broader transformations in strategic thinking and institutional practice (Hoffman 2007; Koselleck 2004; Marsili 2023). Concepts do not simply describe reality; they contribute to shaping priorities, legitimising new capabilities and framing responses. Understanding the emergence and diffusion of “cognitive warfare” as a category therefore requires attention to doctrinal debates, bureaucratic interests and normative contests within and across states and international organisations (NATO 2010, 2016, 2021).

Finally, the historically grounded understanding of cognitive warfare developed in this article raises important normative questions. The entanglement of security, platform governance and fundamental rights means that measures adopted in the name of resilience can themselves affect the cognitive and informational conditions of democratic self-government (European Commission 2018; Marsili 2020, 2023, 2025b). Efforts to counter cognitive warfare cannot be reduced to more aggressive information control or to purely technical solutions; they require wider reflection on transparency of infrastructures, protection of privacy, plurality of media and education about the cognitive dimension of digital environments.

From the perspective of Histories, the topic of cognitive warfare invites further work at the intersection of political, intellectual and technological history. Comparative studies of national traditions of psychological and information warfare, archival investigations into specific institutions and campaigns, and longitudinal analyses of travelling concepts such as “hearts and minds”, “information superiority” or “cognitive domain” would all help to refine and test the argument advanced here (Taylor 2003; Rid 2020; Marsili 2019, 2023, 2025a). As digital technologies continue to transform the conditions of perception, memory and action, historical inquiry can make a distinctive contribution by showing that contemporary debates on cognitive warfare are not an abrupt departure, but one more chapter in a much longer history of attempts to govern the mental and informational dimensions of conflict.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arquilla, J.; Ronfeldt, D. Athena’s Camp: Preparing for Conflict in the Information Age; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S.; Howard, P.N. The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation.; Oxford Internet Institute: Oxford, 2019; Available online: https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2019/09/CyberTroop-Report19.pdf.

- Brundage, M.; Avin, S.; Clark, J.; Toner, H.; Eckersley, P.; Garfinkel, B.; Dafoe, A.; Scharre, P.; Zeitzoff, T.; Filar, B.; et al. The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chesney, R.; Citron, D.K. Deep fakes: A looming challenge for privacy, democracy, and national security. California Law Review 2019, 107, 1753–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, C.G. The Fourth Arm: Psychological Warfare 1938–1945; Davis-Poynter: London, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cull, N.J. The Cold War and the United States Information Agency: American Propaganda and Public Diplomacy, 1945–1989.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- DiResta, R. It’s Not Misinformation. It’s Amplified Propaganda. The Atlantic. 9 October 2021. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/10/disinformation-propaganda-amplification-ampliganda/620334.

- Doob, L.W. Public Opinion and Propaganda.; Cresset Press: London, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Tackling Online Disinformation: A European Approach. COM(2018) 236 final, Brussels. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52018DC0236.

- Freedman, L. The Revolution in Strategic Affairs

. In Adelphi Paper 318; Oxford University Press for the International Institute for Strategic Studies: Oxford, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, L.; Karsh, E. The Gulf Conflict, 1990–1991: Diplomacy and War in the New World Order; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gaddis, J.L. The Cold War: A New History; Penguin: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Galeotti, M. Hybrid War or Gibridnaya Voina? Getting Russia’s Non-Linear Military Challenge Right; Lulu Press: Raleigh, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, K. Handbook of Russian Information Warfare

. In Fellowship Monograph 9; NATO Defense College: Rome, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, T. Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media; Yale University Press: New Haven, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Herf, J. The Jewish Enemy: Nazi Propaganda during World War II and the Holocaust; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, F.G. Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Wars; Potomac Institute for Policy Studies: Arlington, VA, 2007; Available online: https://www.potomacinstitute.org/images/stories/publications/potomac_hybridwar_0108.pdf.

- Hollander, P. Political Pilgrims: Western Intellectuals in Search of the Soviet Union; Oxford University Press: New York, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, A.; O’Loughlin, B. War and Media: The Emergence of Diffused War.; Polity Press: Cambridge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.R. Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty: The CIA Years and Beyond; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jowett, G.S.; O’Donnell, V. Propaganda & Persuasion, 7th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kofman, M.; Rojansky, M. A Closer Look at Russia’s “Hybrid War”

. In Kennan Cable 7; Wilson Center: Washington, DC, 2015; Available online: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/7-KENNAN%20CABLE-ROJANSKY%20KOFMAN.pdf.

- Komer, R.W. Impact of Pacification on Insurgency in South Vietnam; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, 1970; Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2008/P4443.pdf.

- Koselleck, R. Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time.; Columbia University Press: New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell, H.D. Propaganda Technique in the World War.; Kegan Paul: New York; MIT Press: reprinted Cambridge, MA, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Libicki, M.C. What Is Information Warfare? National Defense University Press: Washington, DC, 1995; Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA367662.pdf.

- Lucas, E. The New Cold War: Putin’s Russia and the Threat to the West, Updated ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marsili, M. The press: Fourth power or counter-power? ArtCiencia.com 2019, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, M. COVID-19 Infodemic: Fake News, Real Censorship. Information and Freedom of Expression in Time of Coronavirus. Europea 2020, 10(2), 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, M. Hybrid warfare: Above or below the threshold of armed conflict? Hybrid Warfare: Above or Below the Threshold of Armed Conflict? Honvédségi Szemle - Hungarian Defence Review 2021, 150(1-2), 36–48. Available online: https://kiadvany.magyarhonvedseg.hu/index.php/honvszemle/article/view/917.

- Marsili, M. Guerre à la Carte: Cyber, information, cognitive warfare and the metaverse. Applied Cybersecurity & Internet Governance 2023, 2(1), 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, M.; Wróblewska-Jachna, J. Digital revolution and artificial intelligence as challenges for today. Media i Społeczeństwo 2024, 20(1), 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, M. Cognitive warfare, disinformation, and corporate influence in Europe’s energy transition: Information control, regulation, and human rights implications. Applied Cybersecurity & Internet Governance 2025a, 4(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, M. Emerging and disruptive technologies: Strategic implications and ethical challenges of dual-use innovations. Strategic Leadership Journal. Challenges for Geopolitics and Organizational Development 2025b, 1, 57–71. Available online: https://www.difesa.it/assets/allegati/69106/slj_1_2025.pdf.

- Napoli, P.M. Social Media and the Public Interest: Media Regulation in the Disinformation Age; Columbia University Press: New York, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- NATO. The Alliance’s Strategic Concept. Approved by the Heads of State and Government, North Atlantic Council, Washington, DC; NATO: Brussels, 23–24 April 1999; Available online: https://www.nato.int/en/about-us/official-texts-and-resources/official-texts/1999/04/24/the-alliances-strategic-concept-1999.

- NATO. Active Engagement, Modern Defence: Strategic Concept for the Defence and Security of the Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation; NATO: Lisbon, 2010; Available online: https://www.nato.int/en/about-us/official-texts-and-resources/official-texts/2010/11/19/active-engagement-modern-defence.

- NATO. Warsaw Summit Communiqué.; NATO: Warsaw, 2016; Available online: https://www.nato.int/en/about-us/official-texts-and-resources/official-texts/2016/07/09/warsaw-summit-communique.

- NATO. Brussels Summit Communiqué.; NATO: Brussels, 2021; Available online: https://www.nato.int/en/about-us/official-texts-and-resources/official-texts/2021/06/14/brussels-summit-communique.

- Nelson, M. War of the Black Heavens: The Battles of Western Broadcasting in the Cold War; Brassey’s: London, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Newsinger, J. British Counter-Insurgency: From Palestine to Northern Ireland; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, K. Total Cold War: Eisenhower’s Secret Propaganda Battle at Home and Abroad; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, 2006. [Google Scholar]