2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

This was a prospective, cross-sectional study involving canine patients admitted to the Companion Animal Clinic from March 2018 until November 2018. Dogs were divided into four groups. All dogs were treated according to European legislation on animal handling and experiments (86/609/EU). The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the School of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece (Prot. No. 567/13/03/2018). The owners of the epileptic dogs were briefed about the proposed diagnostic plan (clinicopathological and diagnostic imaging testing) and signed a statement of informed consent for participation in the study.

2.2. Study Population

Group A consisted of healthy dogs (control group) with no history of seizures or any other disease. The dogs were recruited from the stray animal spraying/neutering program, run at the School of Veterinary Medicine in cooperation with the local municipality, following a written agreement. Blood sampling and brain imaging were performed at the time before spraying/ neutering surgery.

The other three groups (groups B, C, and D) consisted of dogs that were admitted with a history of recurrent epileptic seizures or as emergency cases due to

status epilepticus. The dogs were allocated into the three groups after a detailed diagnostic investigation was completed. When the diagnostic investigation did not reveal any structural abnormality, the age of the dog was compatible (> 6 months and < 5 years old) with seizure onset and a history of recurrent epileptic seizures; diagnosis of idiopathic epilepsy was strongly suggestive [

54]. Group B included dogs with idiopathic epilepsy receiving antiepileptic medication, and group C included dogs with idiopathic epilepsy without antiepileptic medication on admission. Group D consisted of dogs with structural epilepsy. The age of seizure onset ranged from 6 months to 5 years in group B and in group C dogs. There was no limitation on age for group D dogs. Prior administration of antiepileptic medication (AEM) was not an exclusion criterion for the study population. The antiepileptic medication and the duration of therapy were recorded. Some dogs that belong in group D underwent AEM on admission as well. Not only the onset of AEM but also the duration of therapy was important and thus it was set as an exclusion criterion. Therefore, dogs that were on AEM on admission were included in the study if the AEM was used in appropriate dose regimen and for a prolonged period to ensure adequate therapeutic serum concentrations. For AEM used in the study population [phenobarbital (PB), levetiracetam (LEV), bromide (Br)], the treatment duration should have been at least 1 month (for PB and LEV), except for bromide which should have been at least 3 months [

55,

56]. Serum drug concentrations were monitored in group B and D dogs in order to assess therapeutic efficacy. Drug measurements were performed in an external collaborating laboratory (IDEXX Laboratories, Kornwestheim, Germany).

Epidemiological data, age of seizure onset, frequency, and type of seizures were also recorded. For dogs receiving AEM, the response to therapy, the frequency, and the type of seizures were included in the database. Dogs that weighed less than 2 kg and dogs with reactive seizures (seizures that are caused by systemic metabolic or exogenous toxic disorder detected either during history taking or during clinicopathological testing), acute/history of head trauma, and congenital diseases (hydrocephalus), and any other concurrent disease (identified during diagnostic work-up) were excluded from the study. A detailed history (age of seizure onset, frequency, type, and duration of seizures, onset of antiepileptic medication, previous laboratory investigation, previous brain diagnostic imaging) was taken, combined with visual proof of the episode using video footage brought by the owner of the epileptic dog to distinguish epileptic seizure from other paroxysmal disorders that can mimic epileptic seizure.

Clinicopathological evaluation included complete blood counts (CBC), serum biochemistry profile, and urinalysis. Complete blood counts and serum biochemistry were performed using ADVIA 120 Hematology System (Bayer Diagnostics, Dublin, Ireland) and Vital Lab Flexor E (Spankeren, Netherlands), respectively.

Diagnostic imaging investigation included thoracic radiographs and abdominal ultrasound. Dogs with any concurrent systemic disease revealed during diagnostic investigation were excluded from the study. Brain diagnostic imaging involved computed tomography (CT) (Optima 16 slices, GEHEALTHCARE, Germany) or/and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (SignaHDe 1,5T, GE-e, Canada) under general anesthesia, propofol induced, and isoflurane maintained.

2.3. Sampling

2.3.1. Blood Sampling

Blood samples were collected from either the cephalic or the jugular vein and stored in serum separator tubes (Eurotubo, Deltalab, 0819, Rubi, Spain) before separation. After centrifugating (3000 x 8 min), serum samples (1ml for each dog) were separated in aliquots and stored in Eppendorf vials (Hamburg, Germany), frozen at -80oC for forthcoming analysis. Frozen samples were shipped for analysis as a single batch using special courier services and transport in containers with card ice.

2.3.2. Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were collected via cisternal tap under general anesthesia and after confirmation from computed tomography (CT) or/and MRI brain imaging for the safety of the procedure. The collected amount of CSF was 1mL/5 kg of body weight. CSF samples with iatrogenic blood contamination were excluded from the study. CSF analysis was performed within 30 min after collection and included total cell counts, measurements of total protein, and cytological examination. The cytological examination of CSF was performed in stained slides obtained using a cytocentrifuge (Aerospray Pro slide stainer/ cytocentrifuge ELI Tech Droup WESCOR) and the cell counts were performed microscopically using a haemocytometer (BLAUBRAND Neubauer improved). CSF total proteins were measured in an automated biochemistry analyzer (FLEXOR Vitalab, The Netherlands) using the pyrogallol red method (Dia Sys Diagnostic Systems, France). The remaining CSF samples were centrifuged to remove cells and the supernatants were frozen at -80o C for forthcoming analysis. Frozen samples were shipped for analysis as a single batch using special courier services and transport in containers with dry ice.

2.4. Sample Analysis

2.4.1. Serum Sample Analysis

Paraoxonase 1 (PON1), cupric reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC), cholinesterase and C-reactive protein (CRP) were assessed in serum samples in all 4 groups of dogs.

2.4.2. CSF Sample Analysis

Paraoxonase 1 (PON1), CUPRAC, ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), cholinesterase, and oxytocin were assessed in CSF samples. The limited volume of CSF collection was not sufficient for all five markers measurement therefore, some data are missing.

2.4.3. Methods

Serum and CSF Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) activity assays were assessed based on the hydrolytic activity of the enzyme in 4-nitrophenyl acetate substrate as previously described [

57].

CUPRAC is a laboratory method that evaluates the reduction in cupric ions (Cu+2) to cuprous ions (Cu+) by antioxidant agents in the serum and CSF samples using a validated automated assay [

58]

.

FRAP assay in CSF assessed the reduction of ferric-tripyridyltriazine (Fe3+-TPTZ) to the ferrous (Fe2+) following previously described methods [

59,

60]

.

The activity of cholinesterase was measured in serum and CSF samples using butyrylthiocholine as previously described [

61].

CRP was measured with an immunoturbidimetric assay previously validated in dogs [

62].

All the previous assays showed inter and intra-assay imprecision values lower than 15 and linearity after serial sample dilution.

For oxytocin measurement, a direct competition assay based on AlphaLISA (PerkinElmer, MA, USA) technology in which acceptor beads coated to a monoclonal anti-oxytocin antibody were used. The monoclonal antibody used for assay development is previously described in a previous report about oxytocin measurement in pigs [

63].

For analytical validation of the assay, imprecision was calculated as inter- and intra-assay variations and expressed as coefficients of variation(CVs). Five replicates of two samples with different concentrations (2443.68 and 485.31pg/ mL) were analyzed at the same time to determine the intra-assay precision of the method. Five aliquots of each sample were stored in plastic vials at -80oC. These aliquots were measured in duplicate five times over five different days using freshly prepared calibration curves for inter-assay precision.

The accuracy was evaluated by an assessment of linearity under dilution and recovery experiments. For the linearity evaluation, two samples (2443.68 and 485.31pg/ mL) were serially diluted from 1:2 to 1:256) with AlphaLISA universal buffer.

The detection limit (LD) and lower limit of quantification (LLQ) were obtained to evaluate the sensitivity of the method. The LD was calculated as the mean of 10 replicate measurements of the assay buffer plus three standard deviations. For the LLQ, a serial dilution (from 1:2 to 1:256) of the cerebrospinal fluid sample (384.66 pg/ mL) was performed, analyzing 5 replicates of each dilution in the same run. The CV was calculated for each dilution, establishing the LLQ as the lowest dilution that could be measured with <20% imprecision.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Serum Samples

Descriptive statistics were produced using SPSS 19.0. ANOVA test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference of PON1, CUPRAC, cholinesterase and CRP among the 4 groups of dogs in serum samples. Post-Hoc comparisons were performed in parameters among the four groups. Kruskal-Wallis test was also performed to assess significance among medians of the parameters (PON1, CUPRAC, cholinesterase and CRP) of the four groups. Dunn’s test which followed the Kruskal-Wallis test was also used to assess the significance of the parameters (PON1, CUPRAC, cholinesterase and CRP) among the four groups.

2.5.2. CSF Samples

Descriptive statistics were produced using SPSS 19.0. ANOVA test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference of PON1, CUPRAC, cholinesterase FRAP and oxytocin among the 4 groups of dogs in CSF samples. Post-Hoc comparisons were performed in parameters between the groups. Kruskal-Wallis test was also performed to assess significance among medians of the parameters (PON1, CUPRAC, cholinesterase, FRAP and oxytocin) of the four groups. Dunn’s test which followed the Kruskal-Wallis test was also used to assess the significance of the parameters (PON1, CUPRAC, cholinesterase, FRAP and oxytocin) among the four groups.

4. Discussion

Epilepsy is a complex disease entity that involves inflammatory and oxidative stress processes in addition to abnormal electrical activity [

31]. In the current study, inflammatory markers (CRP), oxidative stress markers (PON1, CUPRAC, FRAP), cholinesterase and oxytocin were assessed in serum and CSF samples of epileptic dogs with different types of epilepsy.

Serum CRP can be temporarily increased in patients exhibiting generalized tonic-clonic seizures,

status epilepticus, or prolonged seizures. This increase is modest unless there is another underlying condition [

33,

38]. Most patients with epilepsy have normal CRP, especially between seizures [

38]. In the current study, CRP was assessed in serum samples of epileptic dogs. Median values were 5.55 μg/ml for group A (control group), 4.1 μg/ml for group B, 3.4μg/ml for group C, and 3.8 μg/ml for group D. None of the median values exceeded the reference range for CRP in serum samples (< 10 μg/ml). All comparisons among the four groups did not reveal any significant differences. Multiple human studies have indicated increased serum CRP values in epileptic patients compared to controls [

41,

42]. In particular, despite the increased serum CRP concentration in refractory epilepsy cases, CRP values were decreased when patients received antiepileptic medication, but still remained increased compared to controls [

33,

35,

37]. Levetiracetam antiepileptic treatment decreased serum CRP concentration compared to other antiepileptics [

40,

43]. In an experimental rat model assessing CRP at different time points after electrically induced-

status epilepticus, there were no concentration changes identified [

34]. In contrast to this study, other studies involving epileptic dogs indicated increased serum CRP levels in dogs diagnosed with structural epilepsy compared to idiopathic epilepsy dogs and in dogs exhibiting

status epilepticus [

44,

45]. In the current study, there was no significant difference in CRP levels among the three groups of epileptic dogs compared to controls. The time elapsing from the last seizure till serum sampling and the different antiepileptic medications administered (group B and group D dogs) could have influence results. In particular, concerning the time interval between the last seizure and serum sampling, it was not standardized for the study population; therefore, sampling was performed regardless of the time the last epileptic seizure occurred. Furthermore, no inflammatory encephalopathy cases were included in the structural epilepsy group D). In a previously published study, including dogs diagnosed with distemper encephalitis, serum CRP levels were elevated compared to controls [

46]. The results of the current study supported evidence from human patients; CRP had been within reference ranges in epileptic patients suffering from tonic-clonic epileptic seizures [

38]. Results from the current study indicated that CRP was not a reliable inflammatory marker for either idiopathic or structural epilepsy in dogs.

Oxidative stress has been associated with epilepsy in both human and canine patients [

24,

25,

27,

46]. Although there are multiple studies assessing oxidative stress in human neurological diseases, including epilepsy, the bibliography is limited in canine epilepsy [

26,

28,

64,

65]. In the current study, selective oxidative stress markers had been evaluated in both serum (PON1 and CUPRAC) and CSF (PON1, CUPRAC, FRAP) samples of three groups of dogs diagnosed with different types of epilepsy and a control group (group A). Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) has an important anti-inflammatory and antioxidant role; it protects lipids and lipoproteins from oxidative damage by preventing lipid peroxidation in cell membranes and lipoproteins [

66,

67]. In general, PON1 concentration was decreased in oxidative stress [

66,

67]. Overall assessment of median values of PON1of the current study indicated that serum concentrations were much lower compared to CSF concentrations. To the author’s knowledge, there is no available literature indicating the reference range of PON1 in serum or CSF in dogs with epilepsy. In the study of Radamovik et al (2023), where antioxidant markers, including PON1, in dogs with idiopathic epilepsy were assessed, it was concluded that serum PON1 was lower compared to healthy controls, but no reference ranges were provided. Contrary to the results of comparisons of the serum PON1 values among the four study groups, there was a statistically significant difference in CSF PON1 when healthy controls (group A) and dogs with idiopathic epilepsy that did not receive antiepileptic medication (group C) were compared with structural epilepsy (group D). A possible explanation for this finding could be the severity of brain damage in group D cases (structural epilepsy) and the demand for further antioxidant protection of the nervous tissue from further damage. Since PON1 cannot cross blood-brain barrier (BBB), even if it is impaired [

68], the results of the current study are an important finding that requires further investigation. The same research group mentioned that despite the fact that there is no documented gene expression in mouse or human brain tissue, a hypothesis of transport of PON1 via “discoidal HDL” with unspecified mechanisms could not be excluded [

68]. There were additional studies of PON1 identification in CSF samples of patients suffering from neurodegenerative diseases and they speculate that CSF PON1 originated from the periphery [

69,

70]. Therefore, CSF PON1 identification, origin and mechanism of action in epilepsy need further investigation.

CUPRAC measurement is a reliable method for assessing the antioxidant capacity of a sample by reducing Cu

2+ to Cu

1+ [

58]. Therefore, decreased CUPRAC values may indicate reduced antioxidant defense in multiple diseases [

58]. Limited data are available regarding the assessment of CUPRAC in human and canine epilepsy. Overall assessment of median CUPRAC values between the two different sample types (serum and CSF) indicates a tendency of higher CUPRAC values in serum compared to CSF (except for group D). Although there was no significance identified in serum CUPRAC among the four groups, CSF CUPRAC was statistically significant when group A was compared with group D dogs. This could indicate that more severe brain pathologies (structural epilepsy) were associated with an increased demand for antioxidant protection of the tissue. To the author’s knowledge, there are no other previously published papers assessing CUPRAC in epileptic patients.

FRAP (Ferric reducing ability) is a method that assesses the antioxidant capacity of a sample by reducing the ferric ion (Fe

3+) to ferrous ion (Fe

2+) [

59]. In the current study FRAP was evaluated in CSF. Statistical analysis did not reveal any significance of FRAP among the four groups. Previous studies reported increased serum and CSF FRAP values in canine patients with distemper encephalitis and decreased values in human patients diagnosed with Fabry disease [

46,

64]. Since published literature is limited and involves different species (human vs canine) and/or different disease entities, secure conclusions could not be extrapolated regarding FRAP in canine epilepsy.

Cholinesterase activity (acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase) is correlated with epilepsy through cholinergic neurotransmission, which is closely linked to neuronal excitability and seizure activity [

47,

65]. In this study cholinesterase was assessed in both serum and CSF samples of epileptic dogs and healthy controls. Serum cholinesterase activity was not significant among the four study groups. On the contrary, CSF cholinesterase activity was significant when group D dogs (structural epilepsy) were compared with the other two groups of idiopathic epilepsy (groups B and C) and the control group (group A). CSF cholinesterase activity is altered (increased) probably through a localized release in the brain, as a compensatory mechanism [

71]. In this study, both serum and CSF median cholinesterase values are increased, but the increase in CSF is more prominent. Interestingly, an increase was also recorded in group A (control group). A possible explanation could be that stress may be responsible since these dogs were thoroughly investigated and no abnormalities were identified during routine physical examination and clinicopathological testing. Bibliography supports the influence of acute stress episode on cholinesterase by increasing its activity in the brain and peripheral nervous system [

72].

In this report an AlphaLISA assay for the measurement of oxytocin in CSF of dogs was analytically validated given adequate values of precision and accuracy and indicating that this assay can be applied for oxytocin CSF quantification. In humans and rats exogenous oxytocin administration (intranasally, intra-hippocampal microinjection) may reduce seizure severity and frequency in a long-term basis [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. In this study, CSF endogenous oxytocin levels were evaluated in the four groups of dogs. There was a statistically significant increase in CSF oxytocin between group D dogs compared to the other two groups of idiopathic epilepsy dogs (groups B and C). This increase in group D could be due to the presence of more severe brain lesions when structural epilepsy is suspected, and could increase to compensate for the damage since it produces neuroprotection [

53]. However, the small sample size of group D dogs (8 dogs) necessitates further investigation in a larger animal population.

The limitations of the current study originated from the retrospective nature of the study, with some missing data. The volume of CSF that may safely be collected from the patients was small and inadequate to evaluate all parameters in all dogs. The small sample size of each group may impact statistical analysis results. The heterogeneity of the antiepileptic medication of groups B and D dogs, the variable frequency of epileptic seizures, and the poorly defined time interval from the last epileptic seizure until sampling may have had an impact on results. Additional research is required to evaluate cholinesterase, oxytocin and oxidative stress, and inflammatory markers in larger groups of epileptic dogs. Homogeneity is quite difficult to obtain in naturally-occurring animal studies since each individual requires specific antiepileptic medication and seizure frequency is unique and unpredictable for every case.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.P.; methodology, R.B., A.G., M.B., J.D.M.G. and D.G.; software, I.S.; validation, R.B., A.G., M.B., J.D.M.G. and I.S.; formal analysis, R.B.; investigation, R.B. and A.G.; resources, R.B. M.B., J.D.M.G., and A.G.; data curation, R.B., M.B., J.D.M.G. and D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B.; writing—review and editing, Z.P., M.B., J.D.M.G.; visualization, Z.P.; supervision, Z.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

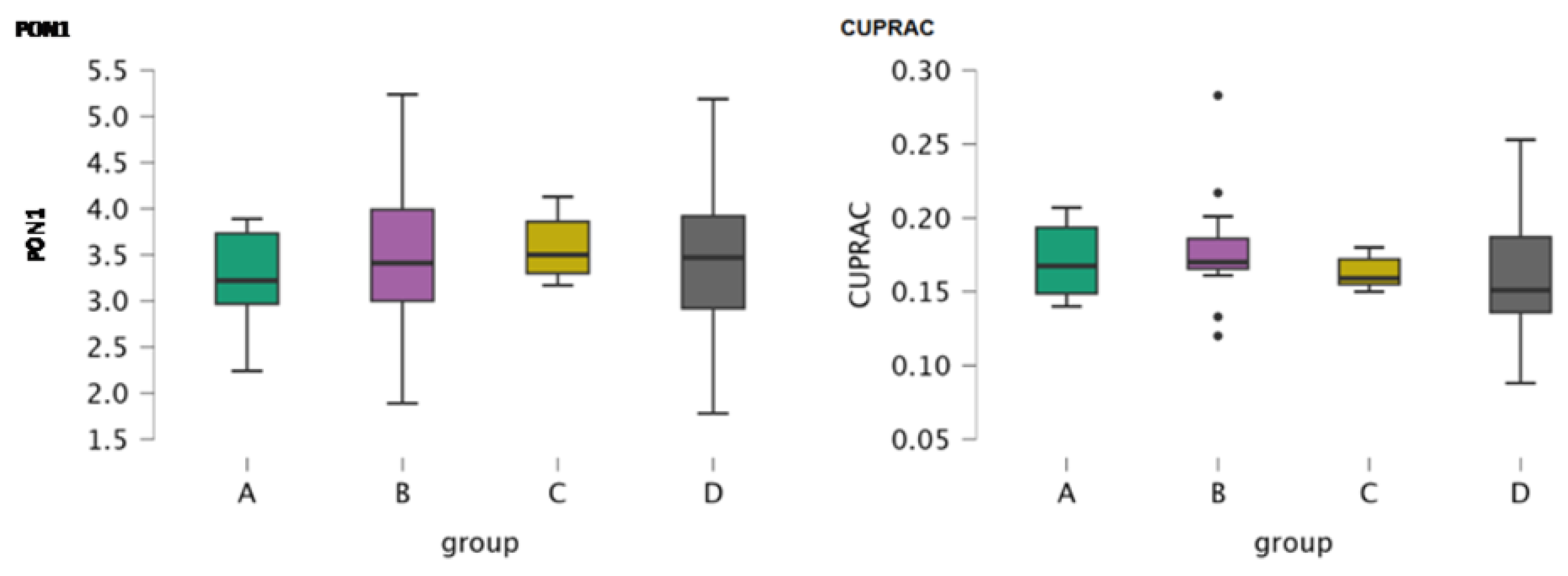

Figure 1.

Boxplots of the concentration of the oxidative stress parameters (PON1 and CUPRAC) in serum samples.

Figure 1.

Boxplots of the concentration of the oxidative stress parameters (PON1 and CUPRAC) in serum samples.

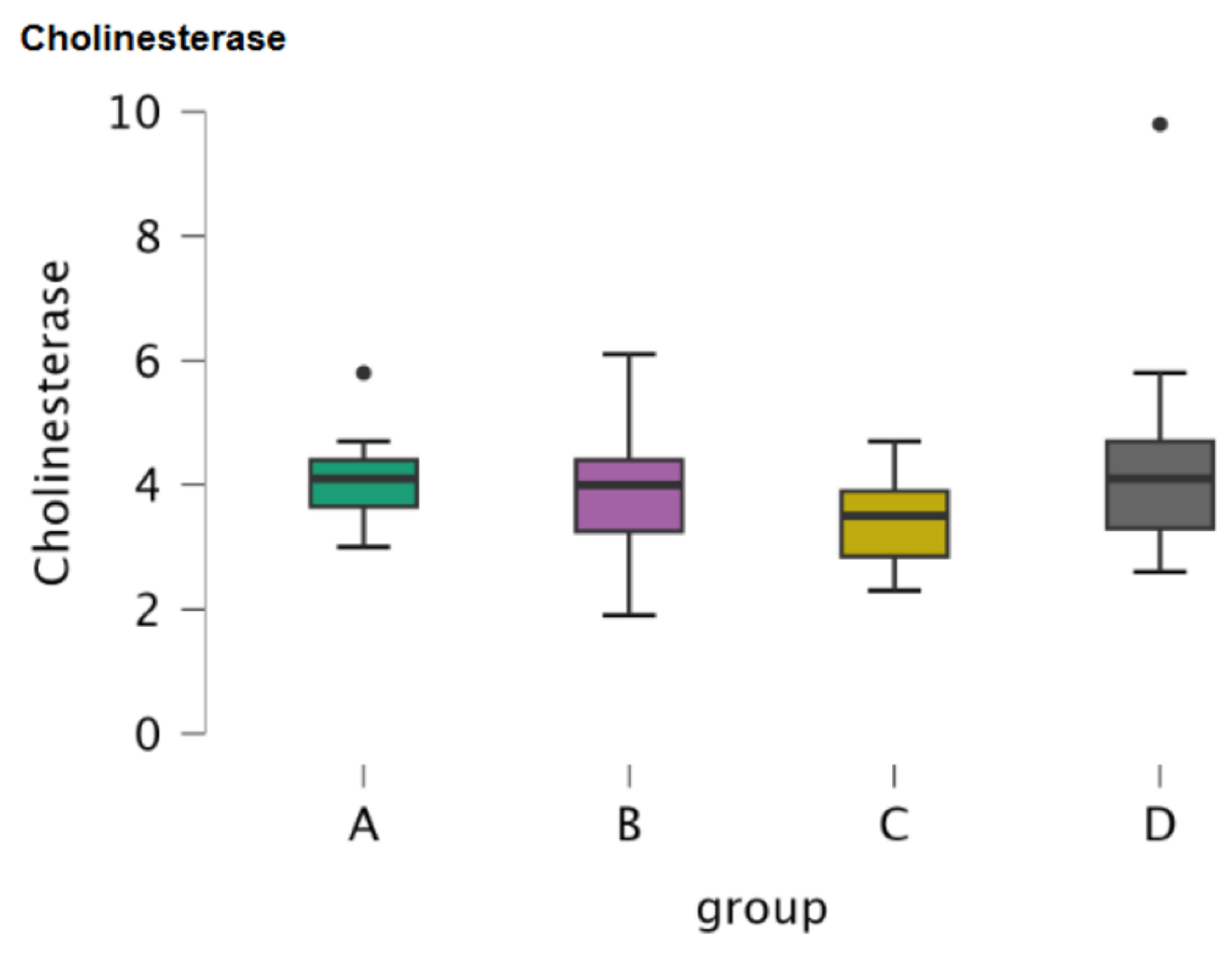

Figure 2.

Boxplot of the concentration of cholinesterase in serum samples.

Figure 2.

Boxplot of the concentration of cholinesterase in serum samples.

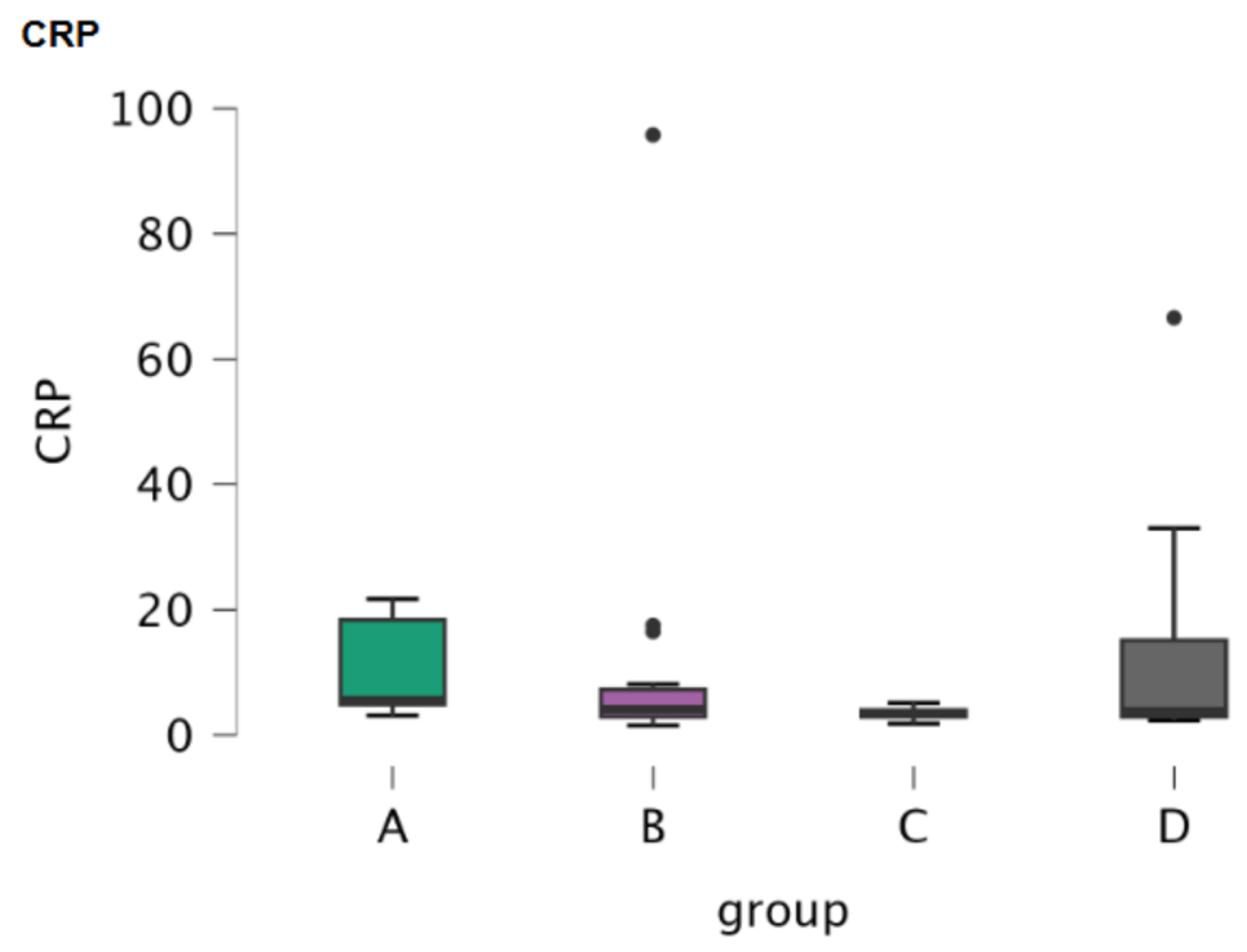

Figure 3.

Boxplot of the concentration of CRP in serum samples.

Figure 3.

Boxplot of the concentration of CRP in serum samples.

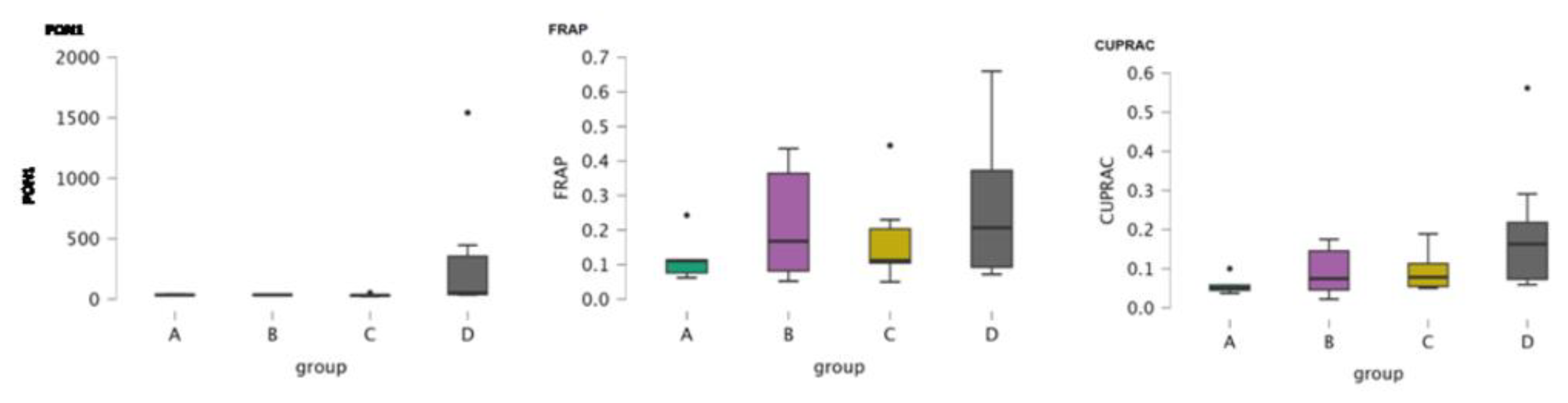

Figure 4.

Boxplots of the concentration of oxidative stress markers in CSF samples.

Figure 4.

Boxplots of the concentration of oxidative stress markers in CSF samples.

Figure 5.

Boxplot of the concentration of cholinesterase in CSF samples.

Figure 5.

Boxplot of the concentration of cholinesterase in CSF samples.

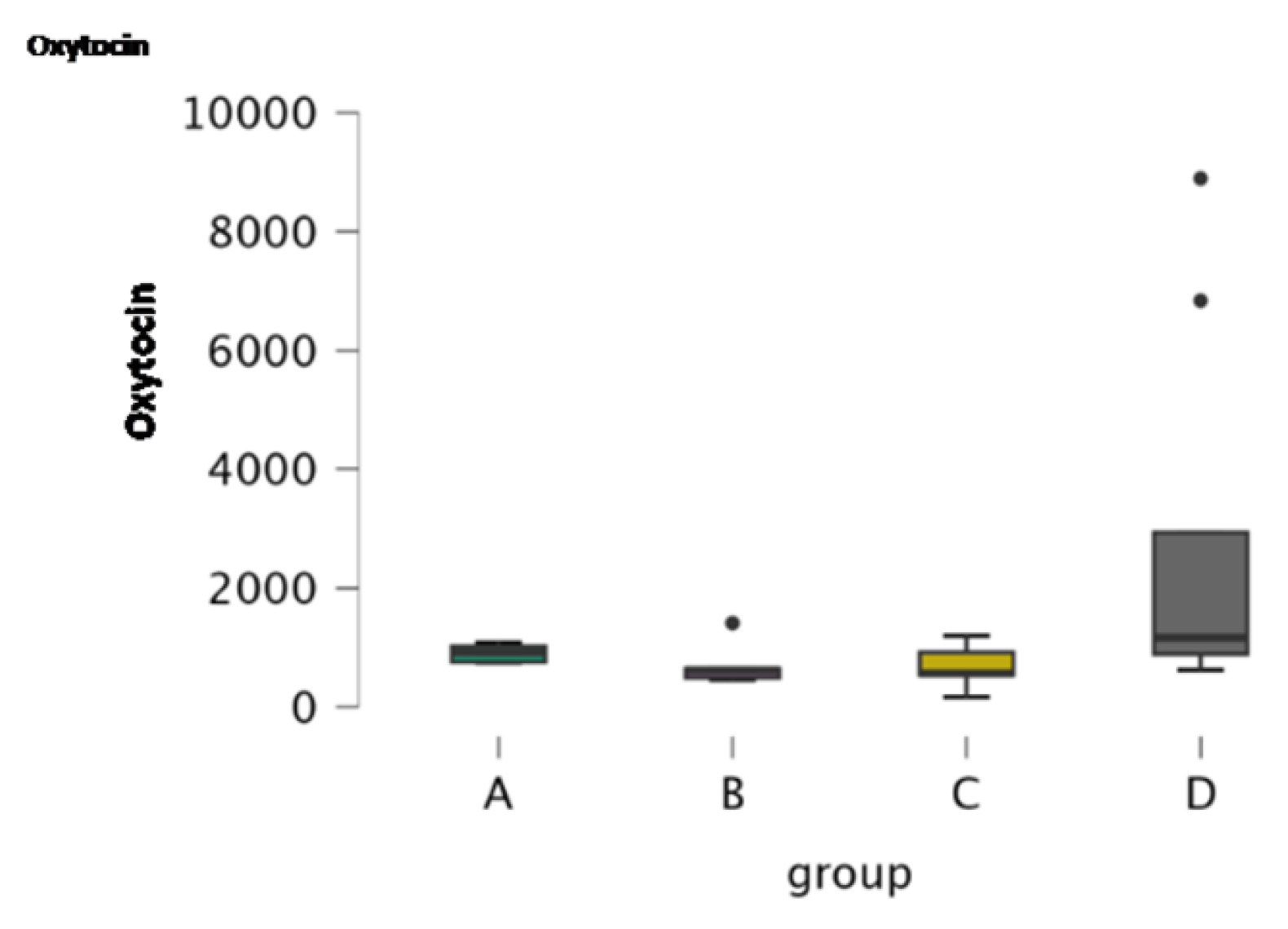

Figure 6.

Boxplot of the concentration of oxytocin in CSF samples.

Figure 6.

Boxplot of the concentration of oxytocin in CSF samples.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the serum oxidative stress parameters, cholinesterase and c- reactive protein (CRP).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the serum oxidative stress parameters, cholinesterase and c- reactive protein (CRP).

| Parameters |

PON1 |

CUPRAC |

Cholinesterase |

CRP |

| Groups |

A |

B |

C |

D |

A |

B |

C |

D |

A |

B |

C |

D |

A |

B |

C |

D |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Valid |

8 |

15 |

11 |

17 |

8 |

15 |

11 |

17 |

8 |

15 |

11 |

17 |

8 |

15 |

11 |

17 |

|

| Missing |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

| Median |

3.220 |

3.410 |

3.500 |

3.470 |

0.167 |

0.170 |

0.159 |

0.151 |

4.100 |

4.000 |

3.500 |

4.100 |

5.550 |

4.100 |

3.400 |

3.800 |

|

| Mean |

3.231 |

3.557 |

3.586 |

3.400 |

0.171 |

0.179 |

0.163 |

0.164 |

4.125 |

3.827 |

3.436 |

4.306 |

10.338 |

11.860 |

3.464 |

11.629 |

|

| Std. Deviation |

0.583 |

0.937 |

0.337 |

0.867 |

0.027 |

0.037 |

0.010 |

0.047 |

0.880 |

1.065 |

0.757 |

1.682 |

7.773 |

23.722 |

0.904 |

16.521 |

|

| 95% CI Std. Dev. Upper |

1.186 |

1.478 |

0.592 |

1.320 |

0.056 |

0.059 |

0.018 |

0.071 |

1.790 |

1.680 |

1.328 |

2.561 |

15.820 |

37.412 |

1.586 |

25.143 |

|

| 95% CI Std. Dev. Lower |

0.385 |

0.686 |

0.236 |

0.646 |

0.018 |

0.027 |

0.007 |

0.035 |

0.582 |

0.780 |

0.529 |

1.253 |

5.139 |

17.368 |

0.631 |

12.304 |

|

| Skewness |

-0.513 |

0.339 |

0.267 |

-0.013 |

0.160 |

1.395 |

0.473 |

0.674 |

0.740 |

0.094 |

0.163 |

2.290 |

0.668 |

3.612 |

0.039 |

2.678 |

|

| Std. Error of Skewness |

0.752 |

0.580 |

0.661 |

0.550 |

0.752 |

0.580 |

0.661 |

0.550 |

0.752 |

0.580 |

0.661 |

0.550 |

0.752 |

0.580 |

0.661 |

0.550 |

|

| Kurtosis |

-0.558 |

-0.272 |

-1.479 |

-0.059 |

-2.208 |

3.976 |

-1.230 |

-0.271 |

1.017 |

0.407 |

-0.847 |

7.039 |

-1.941 |

13.478 |

0.288 |

7.838 |

|

| Std. Error of Kurtosis |

1.481 |

1.121 |

1.279 |

1.063 |

1.481 |

1.121 |

1.279 |

1.063 |

1.481 |

1.121 |

1.279 |

1.063 |

1.481 |

1.121 |

1.279 |

1.063 |

|

| Shapiro-Wilk |

0.935 |

0.958 |

0.924 |

0.979 |

0.864 |

0.868 |

0.918 |

0.925 |

0.949 |

0.971 |

0.967 |

0.778 |

0.773 |

0.438 |

0.979 |

0.613 |

|

| P-value of Shapiro-Wilk |

0.561 |

0.657 |

0.351 |

0.950 |

0.131 |

0.032 |

0.303 |

0.181 |

0.706 |

0.872 |

0.860 |

0.001 |

0.015 |

1.150×10-6

|

0.961 |

1.386×10-5

|

|

| Minimum |

2.240 |

1.890 |

3.170 |

1.780 |

0.140 |

0.120 |

0.150 |

0.088 |

3.000 |

1.900 |

2.300 |

2.600 |

3.100 |

1.500 |

1.800 |

2.300 |

|

| Maximum |

3.890 |

5.240 |

4.130 |

5.190 |

0.207 |

0.283 |

0.180 |

0.253 |

5.800 |

6.100 |

4.700 |

9.800 |

21.700 |

95.800 |

5.100 |

66.600 |

|

Table 2.

Post-Hoc comparisons for oxidative stress markers, cholinesterase and CRP in serum samples.

Table 2.

Post-Hoc comparisons for oxidative stress markers, cholinesterase and CRP in serum samples.

| Group comparisons |

Mean Difference |

SE |

df |

t |

pturkey

|

| PON1 |

| A |

B |

-0.326 |

0.337 |

47 |

-0.968 |

0.768 |

| |

C |

-0.355 |

0.358 |

47 |

-0.993 |

0.754 |

| |

D |

-0.169 |

0.330 |

47 |

-0.511 |

0.956 |

| B |

C |

-0.029 |

0.306 |

47 |

-0.095 |

1.000 |

| |

D |

0.157 |

0.273 |

47 |

0.577 |

0.938 |

| C |

D |

0.186 |

0.298 |

47 |

0.626 |

0.923 |

| CUPRAC |

| A |

B |

-0.008 |

0.016 |

47 |

-0.496 |

0.960 |

| |

C |

0.008 |

0.017 |

47 |

0.492 |

0.960 |

| |

D |

0.008 |

0.015 |

47 |

0.489 |

0.961 |

| B |

C |

0.016 |

0.014 |

47 |

1.123 |

0.677 |

| |

D |

0.015 |

0.013 |

47 |

1.205 |

0.627 |

| C |

D |

-6.791×10-4

|

0.014 |

47 |

-0.049 |

1.000 |

| Cholinesterase |

| A |

B |

0.298 |

0.543 |

47 |

0.549 |

0.946 |

| |

C |

0.689 |

0.576 |

47 |

1.195 |

0.633 |

| |

D |

-0.181 |

0.532 |

47 |

-0.340 |

0.986 |

| B |

C |

0.390 |

0.492 |

47 |

0.793 |

0.857 |

| |

D |

-0.479 |

0.439 |

47 |

-1.091 |

0.697 |

| C |

D |

-0.870 |

0.480 |

47 |

-1.812 |

0.281 |

| CRP |

| A |

B |

-0.326 |

0.337 |

47 |

-0.968 |

0.768 |

| |

C |

-0.355 |

0.358 |

47 |

-0.993 |

0.754 |

| |

D |

-0.169 |

0.330 |

47 |

-0.511 |

0.956 |

| B |

C |

-0.029 |

0.306 |

47 |

-0.095 |

1.000 |

| |

D |

0.157 |

0.273 |

47 |

0.577 |

0.938 |

| C |

D |

0.186 |

0.298 |

47 |

0.626 |

0.923 |

Table 3.

Kruskal-Wallis test for oxidative stress markers, cholinesterase and CRP in serum samples.

Table 3.

Kruskal-Wallis test for oxidative stress markers, cholinesterase and CRP in serum samples.

| |

|

PON1 |

CUPRAC |

Cholinesterase |

CRP |

| |

Factor |

group |

group |

group |

group |

| |

Statistic |

1.700 |

3.120 |

3.294 |

6.648 |

| |

dF |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| |

P |

0.637 |

0.374 |

0.348 |

0.084 |

| |

Rank ε2 |

0.034 |

0.062 |

0.066 |

0.133 |

| 95% CI for Rank ε2

|

Lower |

0.009 |

0.010 |

0.017 |

0.059 |

| Upper |

0.272 |

0.358 |

0.299 |

0.305 |

| |

Rank η2 |

0.000 |

0.003 |

0.006 |

0.078 |

| 95% CI for Rank η2

|

Lower |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.016 |

| Upper |

0.174 |

0.295 |

0.229 |

0.296 |

Table 4.

Dunn’s Post-Hoc comparisons for oxidative stress markers, cholinesterase and CRP in serum samples.

Table 4.

Dunn’s Post-Hoc comparisons for oxidative stress markers, cholinesterase and CRP in serum samples.

| Comparisons |

z |

Wi

|

Wj

|

rrb

|

p |

pbonf

|

pholm

|

| PON1 |

| A - B |

-0.809 |

20.938 |

26.200 |

0.167 |

0.419 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - C |

-1.299 |

20.938 |

29.909 |

0.409 |

0.194 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - D |

-0.744 |

20.938 |

25.676 |

0.184 |

0.457 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - C |

-0.629 |

26.200 |

29.909 |

0.152 |

0.530 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - D |

0.099 |

26.200 |

25.676 |

0.043 |

0.921 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| C - D |

0.736 |

29.909 |

25.676 |

0.134 |

0.462 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| CUPRAC |

| A - B |

-0.595 |

27.063 |

30.933 |

0.083 |

0.552 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - C |

0.292 |

27.063 |

25.045 |

0.034 |

0.770 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - D |

0.831 |

27.063 |

21.765 |

0.176 |

0.406 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - C |

0.998 |

30.933 |

25.045 |

0.406 |

0.318 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - D |

1.742 |

30.933 |

21.765 |

0.278 |

0.082 |

0.490 |

0.490 |

| C - D |

0.571 |

25.045 |

21.765 |

0.262 |

0.568 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Cholinesterase |

| A - B |

0.524 |

29.438 |

26.033 |

0.092 |

0.601 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - C |

1.480 |

29.438 |

19.227 |

0.432 |

0.139 |

0.833 |

0.695 |

| A - D |

0.110 |

29.438 |

28.735 |

0.044 |

0.912 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - C |

1.155 |

26.033 |

19.227 |

0.255 |

0.248 |

1.000 |

0.993 |

| B - D |

-0.514 |

26.033 |

28.735 |

0.118 |

0.607 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| C - D |

-1.655 |

19.227 |

28.735 |

0.369 |

0.098 |

0.588 |

0.588 |

| CRP |

| A - B |

-0.809 |

20.938 |

26.200 |

0.167 |

0.419 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - C |

-1.299 |

20.938 |

29.909 |

0.409 |

0.194 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - D |

-0.744 |

20.938 |

25.676 |

0.184 |

0.457 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - C |

-0.629 |

26.200 |

29.909 |

0.152 |

0.530 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - D |

0.099 |

26.200 |

25.676 |

0.043 |

0.921 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| C - D |

0.736 |

29.909 |

25.676 |

0.134 |

0.462 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of CSF oxidative stress and inflammatory markers, cholinesterase and oxytocin.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of CSF oxidative stress and inflammatory markers, cholinesterase and oxytocin.

| Parameters |

PON1 |

FRAP |

Cholinestrase |

CUPRAC |

Oxytocin |

| Groups |

A |

B |

C |

D |

A |

B |

C |

D |

A |

B |

C |

D |

A |

B |

C |

D |

A |

B |

C |

D |

| Valid |

5 |

4 |

5 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

5 |

4 |

6 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

| Missing |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Median |

34.100 |

34.800 |

31.000 |

51.000 |

0.111 |

0.167 |

0.112 |

0.206 |

58.000 |

65.600 |

77.550 |

152.700 |

0.050 |

0.074 |

0.078 |

0.163 |

912.920 |

615.285 |

561.190 |

1161.220 |

| Mean |

34.920 |

34.450 |

31.860 |

345.014 |

0.121 |

0.218 |

0.175 |

0.263 |

61.280 |

72.150 |

79.783 |

368.671 |

0.058 |

0.092 |

0.093 |

0.197 |

902.374 |

698.715 |

688.223 |

2746.130 |

| Std. Deviation |

5.186 |

3.580 |

12.054 |

551.093 |

0.072 |

0.171 |

0.133 |

0.208 |

13.030 |

20.756 |

37.847 |

454.231 |

0.025 |

0.064 |

0.052 |

0.167 |

151.306 |

358.166 |

343.063 |

3223.943 |

| Skewness |

0.931 |

-0.549 |

1.502 |

2.238 |

1.705 |

0.492 |

1.704 |

1.008 |

0.131 |

1.431 |

0.274 |

2.038 |

1.720 |

0.467 |

1.261 |

1.760 |

0.023 |

2.142 |

0.017 |

1.521 |

| Std. Error of Skewness |

0.913 |

1.014 |

0.913 |

0.794 |

0.913 |

0.845 |

0.794 |

0.752 |

0.913 |

1.014 |

0.845 |

0.794 |

0.913 |

0.845 |

0.794 |

0.752 |

0.913 |

0.845 |

0.794 |

0.752 |

| Kurtosis |

0.139 |

0.952 |

2.565 |

5.186 |

3.215 |

-2.187 |

3.133 |

0.387 |

-0.393 |

1.739 |

-1.070 |

4.165 |

3.235 |

-1.954 |

0.740 |

3.379 |

-2.550 |

4.890 |

-0.364 |

0.726 |

| Std. Error of Kurtosis |

2.000 |

2.619 |

2.000 |

1.587 |

2.000 |

1.741 |

1.587 |

1.481 |

2.000 |

2.619 |

1.741 |

1.587 |

2.000 |

1.741 |

1.587 |

1.481 |

2.000 |

1.741 |

1.587 |

1.481 |

| Shapiro-Wilk |

0.902 |

0.982 |

0.851 |

0.658 |

0.816 |

0.851 |

0.826 |

0.866 |

0.978 |

0.867 |

0.961 |

0.709 |

0.831 |

0.892 |

0.846 |

0.805 |

0.902 |

0.700 |

0.964 |

0.690 |

| P-value of Shapiro-Wilk |

0.424 |

0.911 |

0.198 |

0.001 |

0.109 |

0.162 |

0.073 |

0.139 |

0.924 |

0.286 |

0.826 |

0.005 |

0.141 |

0.331 |

0.112 |

0.032 |

0.422 |

0.006 |

0.851 |

0.002 |

| Minimum |

30.300 |

29.800 |

21.200 |

34.600 |

0.062 |

0.052 |

0.050 |

0.072 |

44.400 |

55.800 |

34.000 |

85.800 |

0.037 |

0.022 |

0.050 |

0.059 |

743.270 |

454.080 |

164.890 |

619.650 |

| Maximum |

42.800 |

38.400 |

51.900 |

1542.700 |

0.243 |

0.436 |

0.445 |

0.660 |

78.600 |

101.600 |

133.800 |

1329.400 |

0.100 |

0.175 |

0.189 |

0.562 |

1081.760 |

1409.120 |

1195.170 |

8894.840 |

Table 6.

Post Hoc comparisons for oxidative stress markers (PON1, FRAP and CUPRAC), 11holinesterase in CSF samples.

Table 6.

Post Hoc comparisons for oxidative stress markers (PON1, FRAP and CUPRAC), 11holinesterase in CSF samples.

| Group comparisons |

Mean Difference |

SE |

df |

t |

pturkey

|

| PON1 |

| A |

B |

0.470 |

219.669 |

17 |

0.002 |

1.000 |

| |

C |

3.060 |

207.106 |

17 |

0.015 |

1.000 |

| |

D |

-310.094 |

191.743 |

17 |

-1.617 |

0.396 |

| B |

C |

2.590 |

219.669 |

17 |

0.012 |

1.000 |

| |

D |

-310.564 |

205.249 |

17 |

-1.513 |

0.452 |

| C |

D |

-313.154 |

191.743 |

17 |

-1.633 |

0.387 |

| FRAP |

| A |

B |

-0.096 |

0.098 |

22 |

-0.986 |

0.759 |

| |

C |

-0.054 |

0.095 |

22 |

-0.566 |

0.941 |

| |

D |

-0.141 |

0.092 |

22 |

-1.534 |

0.435 |

| B |

C |

0.043 |

0.090 |

22 |

0.478 |

0.963 |

| |

D |

-0.045 |

0.087 |

22 |

-0.514 |

0.955 |

| C |

D |

-0.088 |

0.084 |

22 |

-1.050 |

0.723 |

| CUPRAC |

| A |

B |

-0.034 |

0.062 |

22 |

-0.542 |

0.948 |

| |

C |

-0.035 |

0.060 |

22 |

-0.582 |

0.936 |

| |

D |

-0.139 |

0.059 |

22 |

-2.367 |

0.113 |

| B |

C |

-0.001 |

0.057 |

22 |

-0.023 |

1.000 |

| |

D |

-0.105 |

0.056 |

22 |

-1.891 |

0.260 |

| C |

D |

-0.104 |

0.053 |

22 |

-1.949 |

0.237 |

| Cholinesterase |

| A |

B |

-10.870 |

176.571 |

18 |

-0.062 |

1.000 |

| |

C |

-18.503 |

159.385 |

18 |

-0.116 |

0.999 |

| |

D |

-307.391 |

154.124 |

18 |

-1.994 |

0.227 |

| B |

C |

-7.633 |

169.905 |

18 |

-0.045 |

1.000 |

| |

D |

-296.521 |

164.980 |

18 |

-1.797 |

0.307 |

| C |

D |

-288.888 |

146.440 |

18 |

-1.973 |

0.235 |

| Oxytocin |

| A |

B |

203.659 |

1112.024 |

22 |

0.183 |

0.998 |

| |

C |

214.151 |

1075.313 |

22 |

0.199 |

0.997 |

| |

D |

-1843.756 |

1046.936 |

22 |

-1.761 |

0.318 |

| B |

C |

10.492 |

1021.705 |

22 |

0.010 |

1.000 |

| |

D |

-2047.415 |

991.794 |

22 |

-2.064 |

0.196 |

| C |

D |

-2057.907 |

950.451 |

22 |

-2.165 |

0.164 |

Table 7.

Kruskal-Wallis test for oxidative stress and inflammatory markers, cholinesterase and oxytocin in CSF samples.

Table 7.

Kruskal-Wallis test for oxidative stress and inflammatory markers, cholinesterase and oxytocin in CSF samples.

| |

|

PON1 |

FRAP |

CUPRAC |

Cholinesterase |

Oxytocin |

| |

Factor |

group |

group |

group |

group |

group |

| |

Statistic |

8.489 |

1.224 |

7.202 |

10.763 |

8.013 |

| |

dF |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| |

P |

0.037 |

0.747 |

0.066 |

0.013 |

0.046 |

| |

Rank ε2 |

0.424 |

0.049 |

0.288 |

0.513 |

0.321 |

| 95% CI for Rank ε2

|

Lower |

0.179 |

0.011 |

0.110 |

0.379 |

0.113 |

| Upper |

0.824 |

0.403 |

0.687 |

0.797 |

0.645 |

| |

Rank η2 |

0.323 |

0.000 |

0.191 |

0.431 |

0.228 |

| 95% CI for Rank η2

|

Lower |

0.108 |

0.000 |

1.106x10-4

|

0.254 |

0.000 |

| Upper |

0.706 |

0.322 |

0.642 |

0.813 |

0.665 |

Table 8.

Dunn’s Post-Hoc comparisons for oxidative stress markers, cholinesterase and oxytocin in CSF samples.

Table 8.

Dunn’s Post-Hoc comparisons for oxidative stress markers, cholinesterase and oxytocin in CSF samples.

| Comparisons |

z |

Wi

|

Wj

|

rrb

|

p |

pbonf

|

pholm

|

| PON1 |

| A - B |

-0.006 |

9.100 |

9.125 |

0.050 |

0.995 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - C |

0.586 |

9.100 |

6.800 |

0.280 |

0.558 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - D |

-2.018 |

9.100 |

16.429 |

0.771 |

0.044 |

0.262 |

0.218 |

| B - C |

0.559 |

9.125 |

6.800 |

0.400 |

0.576 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - D |

-1.879 |

9.125 |

16.429 |

0.786 |

0.060 |

0.362 |

0.241 |

| C - D |

-2.651 |

6.800 |

16.429 |

0.771 |

0.008 |

0.048 |

0.048 |

| FRAP |

| A - B |

-0.587 |

10.700 |

13.417 |

0.167 |

0.557 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - C |

-0.577 |

10.700 |

13.286 |

0.143 |

0.564 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - D |

-1.101 |

10.700 |

15.500 |

0.450 |

0.271 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - C |

0.031 |

13.417 |

13.286 |

0.000 |

0.975 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - D |

-0.504 |

13.417 |

15.500 |

0.125 |

0.614 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| C - D |

-0.559 |

13.286 |

15.500 |

0.143 |

0.576 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| CUPRAC |

| A - B |

-0.879 |

7.600 |

11.667 |

0.200 |

0.380 |

1.000 |

0.759 |

| A - C |

-1.255 |

7.600 |

13.214 |

0.543 |

0.210 |

1.000 |

0.629 |

| A - D |

-2.574 |

7.600 |

18.813 |

0.850 |

0.010 |

0.060 |

0.060 |

| B - C |

-0.364 |

11.667 |

13.214 |

0.095 |

0.716 |

1.000 |

0.759 |

| B - D |

-1.731 |

11.667 |

18.813 |

0.500 |

0.083 |

0.500 |

0.417 |

| C - D |

-1.415 |

13.214 |

18.813 |

0.482 |

0.157 |

0.942 |

0.628 |

| Cholinesterase |

| A - B |

-0.539 |

6.400 |

8.750 |

0.300 |

0.590 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - C |

-0.958 |

6.400 |

10.167 |

0.333 |

0.338 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| A - D |

-3.013 |

6.400 |

17.857 |

1.000 |

0.003 |

0.016 |

0.016 |

| B - C |

-0.338 |

8.750 |

10.167 |

0.167 |

0.735 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| B - D |

-2.238 |

8.750 |

17.857 |

0.857 |

0.025 |

0.151 |

0.126 |

| C - D |

-2.129 |

10.167 |

17.857 |

0.714 |

0.033 |

0.200 |

0.133 |

| Oxytocin |

| A - B |

1.468 |

15.800 |

9.000 |

0.667 |

0.142 |

0.852 |

0.568 |

| A - C |

1.359 |

15.800 |

9.714 |

0.429 |

0.174 |

1.000 |

0.568 |

| A - D |

-0.677 |

15.800 |

18.750 |

0.300 |

0.499 |

1.000 |

0.997 |

| B - C |

-0.168 |

9.000 |

9.714 |

0.000 |

0.867 |

1.000 |

0.997 |

| B - D |

-2.360 |

9.000 |

18.750 |

0.708 |

0.018 |

0.110 |

0.110 |

| C - D |

-2.283 |

9.714 |

18.750 |

0.679 |

0.022 |

0.135 |

0.112 |