Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Overview and Clinical Progress

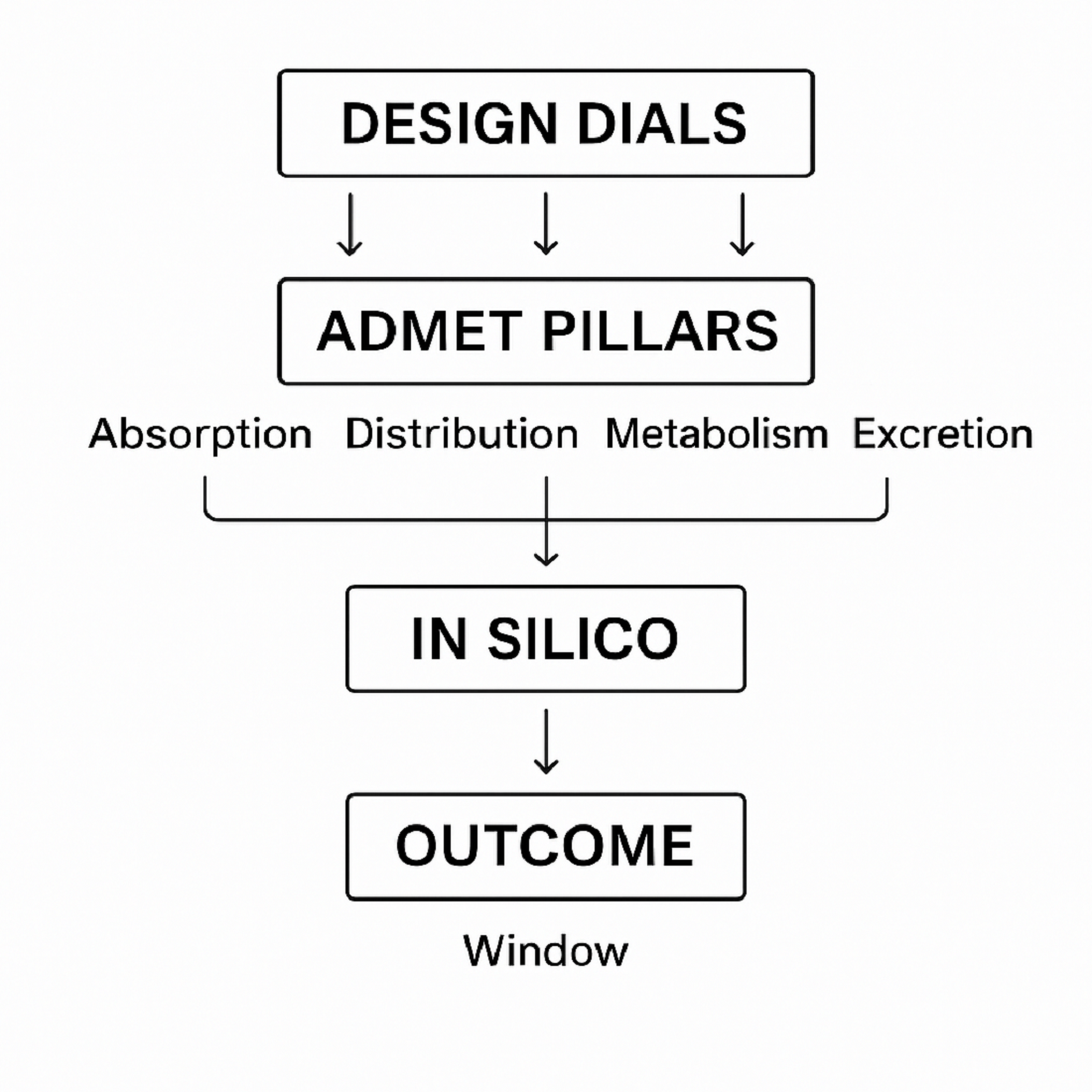

1.2. Emergence of ADMET-Guided Design

1.3. Molecular Classes of Boron-Containing Agents

1.4. European Contributions with Emphasis on Poland

1.5. Aim and Structure of the Review

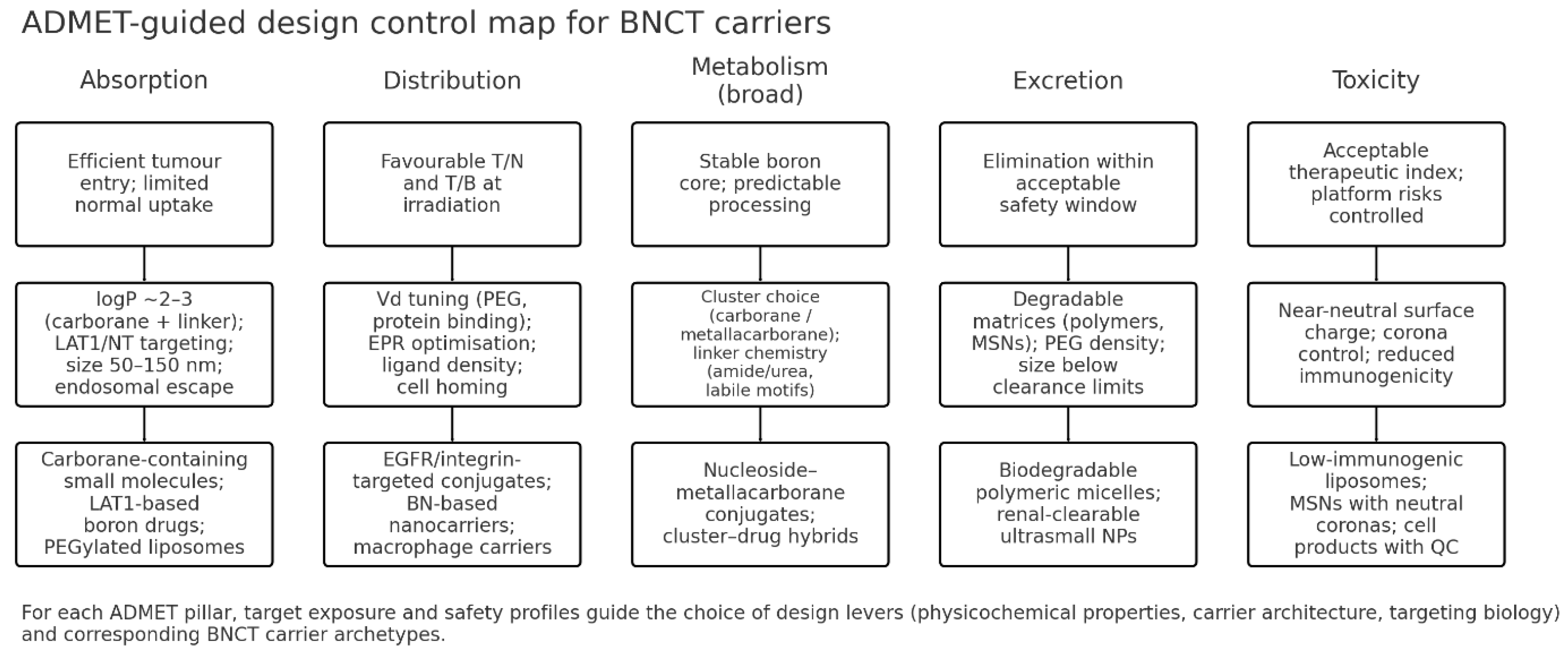

2. Absorption

2.1. Physicochemical Determinants

2.2. Absorptive Pathways

2.3. Quantitative Considerations

2.4. Strategies to Enhance Absorption

2.5. Key Insights

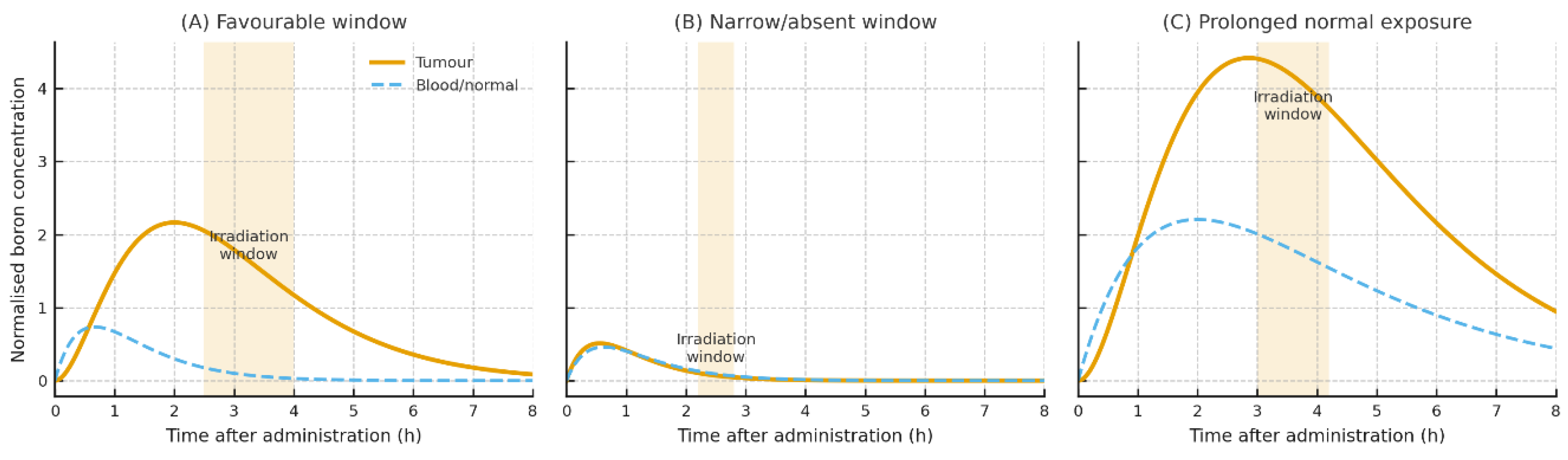

3. Distribution

3.1. Pharmacokinetic Determinants and Modelling

3.2. Tissue Distribution and Tumour Selectivity

3.3. Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) and Blood-Tumour Barrier (BTB)

3.4. Intracellular Distribution and Organelle Targeting

3.5. Distribution Kinetics and Clearance

3.6. Clinical Distribution Data

4. Metabolism of Boron-Containing Agents

4.1. Low-Molecular-Weight Agents

4.2. Metallacarborane and Carborane-Containing Small Molecules

4.3. Bioconjugates: Peptides and Targeted Ligands

4.4. Polymeric and Lipid Carriers

4.5. Inorganic Nanoplatforms

4.6. Cell-Based Delivery Systems

4.7. Analytical Read-Outs and Modelling of Metabolic Fate

4.8. Design Principles from a Metabolism Perspective

5. Excretion of Boron-Containing Agents

5.1. General Principles and Elimination Pathways

5.2. Low-Molecular-Weight Agents

5.3. Bioconjugates (Peptides, Targeted Ligands)

5.4. Polymeric and Lipid Carriers

5.5. Inorganic Nanoplatforms

5.6. Cell-Based Delivery Systems

5.7. Transporters and Clinical Pharmacology

5.8. Design Principles for Favourable Elimination

6. Toxicity and Safety of Boron-Containing Agents

6.1. Clinical Safety Experience and Normal-Tissue Effects

6.2. Small-Molecule Agents

6.3. Bioconjugates and Targeted Ligands

6.4. Polymeric and Lipid Carriers

6.5. Inorganic Nanoplatforms

6.6. Cell-Based Delivery Systems

6.7. Radiobiology-Informed Risk Management

6.8. Drug–Drug Interactions and Supportive Care

6.9. Practical Design Principles (Safety)

6.10. Genetic and Oxidative Safety

6.11. In Vivo Toxicological Profiles and NOAEL Values

6.12. Immunotoxicity and Inflammatory Responses [14,15,16,17,18,20,54,56,83]

7. Key Insights

7.1. Absorption

7.2. Distribution

7.3. Metabolism

7.4. Excretion

7.5. Toxicity

8. Conclusions & Outlook

8.1. Future directions

8.2. Perspective

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Sauerwein, W.A.; Wittig, A.; Moss, R.; Nakagawa, Y. Neutron Capture Therapy: Principles and Applications; Springer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dymova, M.A.; Taskaev, S.Y.; Richter, V.A.; Kuligina, E.V. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Cancer Communications 2020, 40, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti Hughes, A.; Hu, N. Optimizing Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT) to Treat Cancer: An Updated Review on the Latest Developments on Boron Compounds and Strategies. Cancers 2023, 15, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Li, F.; Liang, L. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: Clinical Application and Challenges. Current Oncology 2022, 29, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, S.; Suzuki, M.; Hirose, K.; Tanaka, H.; Kato, T.; Goto, H.; Narita, Y.; Miyatake, S.-I. Accelerator-Based BNCT for Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma: A Multicenter Phase II Study. Neurooncol Adv 2021, 3, vdab067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-T.; Cheng, K.; Liu, B.; Cao, Y.-C.; Fan, J.-X.; Liu, Z.-G.; Zhao, Y.-D. Recent Progress of Nano-Drugs in Neutron Capture Therapy. Theranostics 2024, 14, 3193–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghi, P.; Li, J.; Hosmane, N.S.; Zhu, Y. Next Generation of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT) Agents for Cancer Treatment. Medicinal Research Reviews 2023, 43, 1809–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Tanaka, H.; Kinashi, Y.; Kashino, G.; Masunaga, S.; Hayashi, T.; Uehara, K.; Ono, K.; Suzuki, M. Pharmacokinetic Study of 14C-Radiolabeled p-Boronophenylalanine (BPA) in Sorbitol Solution and the Treatment Outcome of BPA-Based Boron Neutron Capture Therapy on a Tumor-Bearing Mouse Model. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2023, 48, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, H. Response of Normal Tissues to Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT) with 10B-Borocaptate Sodium (BSH) and 10B-Paraboronophenylalanine (BPA). Cells 2021, 10, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xie, L.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Josephson, L.; Liang, S.H.; Zhang, M.-R. Boron Agents for Neutron Capture Therapy. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2020, 405, 213139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Rendina, L.M.; Müllner, M. Carborane-Containing Polymers: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. ACS Polym. Au 2024, 4, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Gu, W.; Tang, F.; Peng, X.; Wei, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, W.; et al. Evaluation of Pharmacokinetics of Boronophenylalanine and Its Uptakes in Gastric Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 925671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gos, M.; Cebula, J.; Goszczyński, T.M. Metallacarboranes in Medicinal Chemistry: Current Advances and Future Perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 8481–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seneviratne, D.S.; Saifi, O.; Mackeyev, Y.; Malouff, T.; Krishnan, S. Next-Generation Boron Drugs and Rational Translational Studies Driving the Revival of BNCT. Cells 2023, 12, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oloo, S.O.; Smith, K.M.; Vincente, M.d.G.H. Multi-Functional Boron-Delivery Agents for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy of Canceres. Cancers 2023, 15, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitto-Barry, A. Polymers and Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT): A Potent Combination. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, K.; Ishida, O.; Kasaoka, S.; Takizawa, T.; Utoguchi, N.; Shinohara, A.; Chiba, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Eriguchi, M.; Yanagie, H. Intracellular Targeting of Sodium Mercaptoundecahydrododecaborate (BSH) to Solid Tumors by Transferrin-PEG Liposomes, for Boron Neutron-Capture Therapy (BNCT). Journal of Controlled Release 2004, 98, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, D.; Advani, P.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Chumsri, S.; Beltran, C.J.; Bush, A.F.; Vallow, L.A. Exploring the Biological and Physical Basis of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT) as a Promising Treatment Frontier in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Gao, P.; Sun, L.; Kang, D.; Kongsted, J.; Poongavanam, V.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X. Recent Developments in the Medicinal Chemistry of Single Boron Atom-Containing Compounds. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2021, 11, 3035–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Hosmane, N.S.; Zhou, Y. Nanostructured Boron Agents for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: A Review of Recent Patents. Medical Review 2023, 3, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti Hughes, A. Importance of Radiobiological Studies for the Advancement of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT). Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2022, 24, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, P.; Wei, Y.; Qu, C.; Tang, F.; Li, Y. Application and Perspectives of Nanomaterials in Boron Neutron Capture Therapy of Tumors. Cancer Nano 2025, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; S Hosmane, N.; Zhu, Y. Boron Chemistry for Medical Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, A.; Kruszakin, R.; Migdał, P.; Pędzich, Z.; Pajtasz-Piasecka, E. Macrophages as Carriers of Boron Carbide Nanoparticles Dedicated to BNCT. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olejniczak, A.B.; Plešek, J.; Leśnikowski, Z.J. Nucleoside–Metallacarborane Conjugates for Base-Specific Metal Labeling of DNA. Chemistry A European J 2007, 13, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leśnikowski, Z.J.; Paradowska, E.; Olejniczak, A.B.; Studzińska, M.; Seekamp, P.; Schüßler, U.; Gabel, D.; Schinazi, R.F.; Plešek, J. Towards New Boron Carriers for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: Metallacarboranes and Their Nucleoside Conjugates. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2005, 13, 4168–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójciuk, K.; Dorosz, M.; Prokopowicz, R. AB028. Selected 10-Atom Derivatives of Mercaptoborate as Substrates for the Coupling Reaction with the Neurotransmitter Protein. Ther Radiol Oncol 2025, 9, AB028–AB028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaś, E.; Dorosz, M.; Wójciuk, K.; Tymińska, K.; Wiliński, M.; Maciak, M.; Domański, S.; Wojtania, G.; Bartosik, Ł.; Małkiewicz, A.; Lechniak, J.; Gryziński, M.A. Reactor Laboratory for Biomedical Research in National Centre for Nuclear Research in Poland. Polish Journal of Medical Physics and Engineering 2021, 27, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings 1PII of Original Article: S0169-409X(96)00423-1. The Article Was Originally Published in Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 23 (1997) 3–25. 1. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. Molecular Properties That Influence the Oral Bioavailability of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidon, G.L.; Lennernäs, H.; Shah, V.P.; Crison, J.R. A Theoretical Basis for a Biopharmaceutic Drug Classification: The Correlation of in Vitro Drug Product Dissolution and in Vivo Bioavailability. Pharm Res 1995, 12, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and Drug-like Compounds: The Rule-of-Five Revolution. Drug Discovery Today: Technologies 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglialunga, S.; Benrimoh, N.; Van Haarst, A. Innovative Approaches to Optimize Clinical Transporter Drug–Drug Interaction Studies. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Li, R.; Lin, J.; Gui, L.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Xia, W.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, S.; Yuan, Z. Novel Promising Boron Agents for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: Current Status and Outlook on the Future. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2024, 511, 215795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murilla, R.M.; Edilo, G.G.; Budlayan, M.L.M.; Auxtero, E.S. Boron Delivery Agents in BNCT: A Mini Review of Current Developments and Emerging Trends. Nano TransMed 2025, 4, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, R.; Miura, Y.; Kono, N.; Fujita, S.; Yamana, K.; Ikeda, A. Boron Agent Delivery Platforms Based on Natural Products for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202400323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugler, M.; Nekvinda, J.; Holub, J.; El Anwar, S.; Das, V.; Šícha, V.; Pospíšilová, K.; Fábry, M.; Král, V.; Brynda, J.; et al. Inhibitors of CA IX Enzyme Based on Polyhedral Boron Compounds. ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 2741–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, M.I. Diastereoselective Synthesis of the Borylated D-Galactose Monosaccharide 3-Boronic-3-Deoxy-d-Galactose and Biological Evaluation in Glycosidase Inhibition and in Cancer for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT). Molecules 2023, 28, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Kong, Z.; Shi, Y.; Xu, M.; Mu, B.-S.; Li, N.; Ma, W.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. A Bis-Boron Boramino Acid PET Tracer for Brain Tumor Diagnosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2024, 51, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, H.; Honda, C.; Wadabayashi, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Yoshino, K.; Hiratsuka, J.; Takahashi, J.; Akaizawa, T.; Abe, Y.; Ichihashi, M.; Mishima, Y. Pharmacokinetics of 10B-p-Boronophenylalanine in Tumours, Skin and Blood of Melanoma Patients: A Study of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy for Malignant Melanoma. Melanoma Research 1999, 9, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfavi, A.; Kavianpour, P.; Rendina, L.M. Carboranes in Drug Discovery, Chemical Biology and Molecular Imaging. Nat Rev Chem 2022, 6, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.C.; Nandwana, N.K.; Das, S.; Nandwana, V.; Shareef, M.A.; Das, Y.; Saito, M.; Weiss, L.M.; Almaguel, F.; Hosmane, N.S.; Evans, T. Boron Chemicals in Drug Discovery and Development: Synthesis and Medicinal Perspective. Molecules 2022, 27, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, F.; Kassiou, M.; Rendina, L.M. Boron in Drug Discovery: Carboranes as Unique Pharmacophores in Biologically Active Compounds. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5701–5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Hey-Hawkins, E. Carbaboranes as Pharmacophores: Properties, Synthesis, and Application Strategies. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7035–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, F.; Wu, Z.; Guo, Q.; Mei, X.; Lu, B.; Wang, C.; et al. Isotoosendanin Exerts Inhibition on Triple-Negative Breast Cancer through Abrogating TGF-β-Induced Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition via Directly Targeting TGFβR1. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2023, 13, 2990–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamek-Gliszczynski, M.J.; Taub, M.E.; Chothe, P.P.; Chu, X.; Giacomini, K.M.; Kim, R.B.; Ray, A.S.; Stocker, S.L.; Unadkat, J.D.; Wittwer, M.B.; et al. Transporters in Drug Development: 2018 ITC Recommendations for Transporters of Emerging Clinical Importance. Clin Pharma and Therapeutics 2018, 104, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Liao, M.; Shen, H.; Yoshida, K.; Zur, A.A.; Arya, V.; Galetin, A.; Giacomini, K.M.; Hanna, I.; Kusuhara, H.; et al. Clinical Probes and Endogenous Biomarkers as Substrates for Transporter Drug-Drug Interaction Evaluation: Perspectives From the International Transporter Consortium. Clin Pharma and Therapeutics 2018, 104, 836–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Fu, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, T.; Liu, Z. Covalent Organic Polymer as a Carborane Carrier for Imaging-Facilitated Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 55564–55573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longmire, M.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Clearance Properties of Nano-Sized Particles and Molecules as Imaging Agents: Considerations and Caveats. Nanomedicine 2008, 3, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexis, F.; Pridgen, E.; Molnar, L.K.; Farokhzad, O.C. Factors Affecting the Clearance and Biodistribution of Polymeric Nanoparticles. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2008, 5, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zheng, J. Clearance Pathways and Tumor Targeting of Imaging Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6655–6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chis, A.A.; Dobrea, C.; Morgovan, C.; Arseniu, A.M.; Rus, L.L.; Butuca, A.; Juncan, A.M.; Totan, M.; Vonica-Tincu, A.L.; Cormos, G.; et al. Applications and Limitations of Dendrimers in Biomedicine. Molecules 2020, 25, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, T.; Fu, C.; Tan, L.; Meng, X.; Liu, H. Biodistribution, Excretion, and Toxicity of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles after Oral Administration Depend on Their Shape. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 2015, 11, 1915–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R.; Nayak, U.Y.; Raichur, A.M.; Garg, S. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Review on Synthesis and Recent Advances. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Chen, X.; Fang, W.; Yu, K.; Gu, W.; Wei, Y.; Zheng, H.; Piao, J.; Li, F. Strategies to Regulate the Degradation and Clearance of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles: A Review. IJN 2024, 19, 5859–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monopoli, M.P.; Åberg, C.; Salvati, A.; Dawson, K.A. Biomolecular Coronas Provide the Biological Identity of Nanosized Materials. Nature Nanotech 2012, 7, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confalonieri, L.; Imperio, D.; Erhard, A.; Fallarini, S.; Compostella, F.; Del Grosso, E.; Balcerzyk, M.; Panza, L. Organotrifluoroborate Sugar Conjugates for a Guided Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: From Synthesis to Positron Emission Tomography. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 48340–48348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-P.; Hsu, F.-C.; Huang, K.-Y.; Hsieh, T.-S.; Farn, S.-S.; Sheu, R.-J.; Yu, C.-S. Fluorine-18 Labeling PEGylated 6-Boronotryptophan for PET Scanning of Mice for Assessing the Pharmacokinetics for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy of Brain Tumors. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2024, 105, 129744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowska, A.; Matuszewski, M.; Zwoliński, K.; Ignaczak, A.; Olejniczak, A.B. Insight into Lipophilicity of Deoxyribonucleoside-boron Cluster Conjugates. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2018, 111, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaniowski, D.; Ebenryter-Olbińska, K.; Sobczak, M.; Wojtczak, B.; Janczak, S.; Leśnikowski, Z.; Nawrot, B. High Boron-Loaded DNA-Oligomers as Potential Boron Neutron Capture Therapy and Antisense Oligonucleotide Dual-Action Anticancer Agents. Molecules 2017, 22, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goszczyński, T.M.; Fink, K. Metallacarboranes: Abiotic Scaffolds for Advanced Drug Discovery. Future Medicinal Chemistry 2025, 17, 2193–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallesch, J.L.; Moore, D.E.; Allen, B.J.; McCarthy, W.H.; Jones, R.; Stening, W.A. The Pharmacokinetics of P-Boronophenylalanine.Fructose in Human Patients with Glioma and Metastatic Melanoma. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 1994, 28, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiger; Iii, W.S.; Palmer, M.R.; Riley, K.J.; Zamenhof, R.G.; Busse, P.M. A Pharmacokinetic Model for the Concentration of10 B in Blood after Boronophenylalanine-Fructose Administration in Humans. Radiation Research 2001, 155, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailuno, G.; Balboni, A.; Caviglioli, G.; Lai, F.; Barbieri, F.; Dellacasagrande, I.; Florio, T.; Baldassari, S. Boron Vehiculating Nanosystems for Neutron Capture Therapy in Cancer Treatment. Cells 2022, 11, 4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, R.F.; Kabalka, G.W.; Yang, W.; Huo, T.; Nakkula, R.J.; Shaikh, A.L.; Haider, S.A.; Chandra, S. Evaluation of Unnatural Cyclic Amino Acids as Boron Delivery Agents for Treatment of Melanomas and Gliomas. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2014, 88, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissfloch, L.; Wagner, M.; Probst, T.; Senekowitsch-Schmidtke, R.; Tempel, K.; Molls, M. A New Class of Drugs for BNCT? Borylated Derivatives of Ferrocenium Compounds in Animal Experiments. Biometals 2001, 14, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalot, G.; Godard, A.; Busser, B.; Pliquett, J.; Broekgaarden, M.; Motto-Ros, V.; Wegner, K.D.; Resch-Genger, U.; Köster, U.; Denat, F.; et al. Aza-BODIPY: A New Vector for Enhanced Theranostic Boron Neutron Capture Therapy Applications. Cells 2020, 9, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Pan, Y.; Zhong, T.; He, S.; Qi, Y.; Huang, Y. Near-Infrared 10B-BODIPY for Precise Guidance of Tracer Imaging and Treatment in Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 9079–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, C.; Lian, G.; Jin, G. Nido-Carborane Encapsulated by BODIPY Zwitterionic Polymers: Synthesis, Photophysical Properties and Cell Imaging. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2021, 25, 101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez-Hernández, J.; Planas, J.G.; Núñez, R. Carborane-Based BODIPY Dyes: Synthesis, Structural Analysis, Photophysics and Applications. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1485301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.P.P.; Saxena, S.; Joshi, R. BODIPY Dyes: A New Frontier in Cellular Imaging and Theragnostic Applications. Colorants 2025, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blethen, K.E.; Arsiwala, T.A.; Fladeland, R.A.; Sprowls, S.A.; Panchal, D.M.; Adkins, C.E.; Kielkowski, B.N.; Earp, L.E.; Glass, M.J.; Pritt, T.A.; Cabuyao, Y.M.; Aulakh, S.; Lockman, P. Modulation of the Blood-Tumor Barrier to Enhance Drug Delivery and Efficacy for Brain Metastases. Neuro-Oncology Advances 2021, 3, v133–v143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, F.; Matsumura, A.; Yamamoto, T.; Kumada, H.; Nakai, K. Enhancement of Sodium Borocaptate (BSH) Uptake by Tumor Cells Induced by Glutathione Depletion and Its Radiobiological Effect. Cancer Letters 2004, 215, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig, A.; Stecher-Rasmussen, F.; Hilger, R.A.; Rassow, J.; Mauri, P.; Sauerwein, W. Sodium Mercaptoundecahydro-Closo-Dodecaborate (BSH), a Boron Carrier That Merits More Attention. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2011, 69, 1760–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Song, Q.; Luan, Y.; Cheng, Y. Targeted Strategies to Deliver Boron Agents across the Blood–Brain Barrier for Neutron Capture Therapy of Brain Tumors. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 650, 123747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumitani, S.; Oishi, M.; Yaguchi, T.; Murotani, H.; Horiguchi, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Ono, K.; Yanagie, H.; Nagasaki, Y. Pharmacokinetics of Core-Polymerized, Boron-Conjugated Micelles Designed for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy for Cancer. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 3568–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Mehta, S.C.; Lu, D.R. Selective Boron Drug Delivery to Brain Tumors for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 1997, 26, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprowls, S.A.; Arsiwala, T.A.; Bumgarner, J.R.; Shah, N.; Lateef, S.S.; Kielkowski, B.N.; Lockman, P.R. Improving CNS Delivery to Brain Metastases by Blood–Tumor Barrier Disruption. Trends in Cancer 2019, 5, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, R.F.; Yang, W.; Rotaru, J.H.; Moeschberger, M.L.; Boesel, C.P.; Soloway, A.H.; Joel, D.D.; Nawrocky, M.M.; Ono, K.; Goodman, J.H. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy of Brain Tumors: Enhanced Survival and Cure Following Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption and Intracarotid Injection of Sodium Borocaptate and Boronophenylalanine. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2000, 47, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, R.F.; Yang, W.; Bartus, R.T.; Moeschberger, M.L.; Goodman, J.H. Enhanced Delivery of Boronophenylalanine for Neutron Capture Therapy of Brain Tumors Using the Bradykinin Analog Cereport (Receptor-Mediated Permeabilizer-7). Neurosurgery 1999, 44, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Barth, R.F.; Rotaru, J.H.; Moeschberger, M.L.; Joel, D.D.; Nawrocky, M.M.; Goodman, J.H.; Soloway, A.H. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy of Brain Tumors: Enhanced Survival Following Intracarotid Injection of Sodium Borocaptate with or without Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 1997, 37, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, T.; Bhandari, S.; Rath, G.; Goyal, A.K. Current Strategies for Targeted Delivery of Bio-Active Drug Molecules in the Treatment of Brain Tumor. Journal of Drug Targeting 2015, 23, 865–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marforio, T.D.; Carboni, A.; Calvaresi, M. In Vivo Application of Carboranes for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT): Structure, Formulation and Analytical Methods for Detection. Cancers 2023, 15, 4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulvik, M.E.; Vähätalo, J.K.; Benczik, J.; Snellman, M.; Laakso, J.; Hermans, R.; Järviluoma, E.; Rasilainen, M.; Färkkilä, M.; Kallio, M.E. Boron Biodistribution in Beagles after Intravenous Infusion of 4-Dihydroxyborylphenylalanine–Fructose Complex. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2004, 61, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. The Current Status and Novel Advances of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy Clinical Trials. Am J Cancer Res 2024, 14, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.F.; Gupta, N.; Kawabata, S. Evaluation of Sodium Borocaptate (BSH) and Boronophenylalanine (BPA) as Boron Delivery Agents for Neutron Capture Therapy (NCT) of Cancer: An Update and a Guide for the Future Clinical Evaluation of New Boron Delivery Agents for NCT. Cancer Communications 2024, 44, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puris, E.; Gynther, M.; Auriola, S.; Huttunen, K.M. L-Type Amino Acid Transporter 1 as a Target for Drug Delivery. Pharm Res 2020, 37, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.P.; Saraiva, L.; Pinto, M.; Sousa, M.E. Boronic Acids and Their Derivatives in Medicinal Chemistry: Synthesis and Biological Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llenas, M.; Cuenca, L.; Santos, C.; Bdikin, I.; Gonçalves, G.; Tobías-Rossell, G. Sustainable Synthesis of Highly Biocompatible 2D Boron Nitride Nanosheets. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, F. Boron Nanocomposites for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy and in Biomedicine: Evolvement and Challenges. Biomater Res 2025, 29, 0145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudawska, A.; Szermer-Olearnik, B.; Szczygieł, A.; Mierzejewska, J.; Węgierek-Ciura, K.; Żeliszewska, P.; Kozień, D.; Chaszczewska-Markowska, M.; Adamczyk, Z.; Rusiniak, P.; Wątor, K.; Rapak, A.; Pędzich, Z.; Pajtasz-Piasecka, E. Functionalized Boron Carbide Nanoparticles as Active Boron Delivery Agents Dedicated to Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. IJN 2025, 20, 6637–6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Lv, L.; Chang, Y.; Li, J.; Xing, G.; Chen, K. Boron Nanodrugs for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2025, 225, 112044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-W.; Liu, Y.-W.H.; Chu, P.-Y.; Liu, H.-M.; Peir, J.-J.; Lin, K.-H.; Huang, W.-S.; Lo, W.-L.; Lee, J.-C.; Lin, T.-Y.; Liu, Y.-M.; Yen, S.-H. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy Followed by Image-Guided Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Locally Recurrent Head and Neck Cancer: A Prospective Phase I/II Trial. Cancers 2023, 15, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.J.; Ding, C.Z.; Akama, T.; Zhang, Y.-K.; Hernandez, V.; Xia, Y. Therapeutic Potential of Boron-Containing Compounds. Future Med. Chem. 2009, 1, 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, L.; Hu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jin, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Chou, S. Understanding High-Rate K + -Solvent Co-Intercalation in Natural Graphite for Potassium-Ion Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 12917–12924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Shi, S.; Yi, J.; Wang, N.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Peng, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, C.; Lyu, A.; Zeng, X.; Zhao, W.; Hou, T.; Cao, D. ADMETlab 3.0: An Updated Comprehensive Online ADMET Prediction Platform Enhanced with Broader Coverage, Improved Performance, API Functionality and Decision Support. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52, W422–W431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Representative (example) | Class / format | Absorption determinants | Principal uptake pathway | Absorption-enhancing strategies | Key caveats (absorption) | Representative refs (updated) |

| Boronophenylalanine (BPA) / BPA–fructose | Low-MW amino-acid analogue | Hydrophilicity; LAT1 engagement; formulation (fructose) | Carrier (LAT1) ± limited diffusion | Transporter targeting; clinical formulation (BPA-F) | Heterogeneous uptake across tumours | [8,10,14,23,29,31,32,40] |

| Sodium borocaptate (BSH) | Low-MW polyhydroborate | Extreme hydrophilicity; minimal permeability | Primarily extracellular | High-dose/infusion; carrier-assisted approaches | Rapid renal clearance; modest selectivity | [1,3,11,12,23] |

| Metallacarborane-modified nucleosides / DNA-affine constructs | Small molecules with carborane clusters | Moderate logP (~2–3); compactness; linker stability | Passive uptake; endocytic contributions | Balance polarity; endosomal-escape motifs | Lysosomal trapping if over-hydrophobic | [7,13,14,15,23,41,42,43,44] |

| Peptide / ligand-targeted conjugates (e.g., RGD, EGFR) | Targeted bioconjugates | Affinity/avidity; receptor density; linker stability | Receptor-mediated endocytosis | Valency optimisation; protease-resistant backbones | Variable receptor expression; endosomal sequestration | [14,18,19,23,33,37,45,46,47] |

| PEGylated boronated liposomes / dendrimers | Polymeric / lipid nanocarriers (≈50–150 nm) | Size; PEG stealth; near-neutral charge | Endocytosis; EPR-mediated tissue entry | PEGylation; size tuning; long-circulating designs | RES uptake if insufficient stealth | [2,11,16,17,23,29,30,31,32,48,49,50,51,52] |

| Functionalised mesoporous silica nanoparticles | Inorganic nanocarriers | Pore/ligand functionalisation; size/shape | Clathrin/caveolin-mediated endocytosis | Ligand grafting; pH-labile gates | Biodegradation timescale context-dependent | [20,21,23,53,54,55,56] |

| Cell-based delivery (e.g., macrophages) | Cellular carriers | Cell homing; payload loading | Active trafficking into tumour microenvironments | Optimise loading/release; exploit chemotaxis | Biological variability | [23,24] |

| Selected PET-oriented tracers (boronated amino acids, sugars) | Low-MW tracers (diagnostic) | Transporter targeting; radiolabelling | Carrier-mediated uptake (LAT1, sugar transporters) | PEGylation/sugar conjugation for uptake/PK | Translation to therapy requires exposure matching | [38,39,57,58] |

| Representative (example) | Distribution determinants | Typical biodistribution pattern | Selectivity (T/N; T/B) | BBB / organ targeting | Distribution-enhancing strategies | Representative refs (updated) |

| BPA / BPA-fructose | LAT1 density; hydrophilicity; short t½ | Tumour uptake in LAT1-high tissues; low Vd | Glioma PET ~2–3+ (context-dependent) | Partial BBB via LAT1 | Timing vs irradiation; formulation | [8,10,14,23,34,40,86] |

| BSH | Hydrophilicity; extracellular confinement | Blood/kidney/liver; modest tumour deposition | Lower than BPA | Poor BBB penetration | Carrier-assisted delivery | [1,11,12,23,34,86] |

| Metallacarborane/DNA-affine constructs | Lipophilicity; nuclear affinity; linker routing | Enhanced cellular/nuclear localisation | Improved local (organelle) targeting | BBB depends on scaffold | Endosomal-escape/linker tuning | [13,14,15,23,41,43,44] |

| Targeted peptides/ligands | Receptor density; valency; stability | Receptor-positive tumour deposition; off-target varies | Higher apparent selectivity with high receptor expression | Transcytosis possible with ligands | Ligand grafting; protease resistance | [14,18,19,23,33,34,35,37,47,86] |

| PEGylated liposomes/dendrimers | PEG stealth; size/charge; corona | Tumour + liver/spleen; prolonged circulation | EPR-driven (model-dependent) | BBB limited; ligand-enhanced entry | Stealth; size tuning; long-circulating designs | [11,15,16,17,23,34,35,48,49,50,51,52] |

| Functionalised MSNs | Surface chemistry; porosity; corona | Tumour (EPR) and liver/spleen | Improved with targeting ligands | BBB limited; ligand-mediated routes | Ligand grafting; neutral corona design | [20,21,23,34,53,54,55,87] |

| Cell-based carriers | Homing to hypoxia/inflammation; cell kinetics | Uniform intratumoural distribution incl. hypoxic zones | Favourable functional selectivity | Cells traverse barriers | Preconditioning; loading optimisation | [23,24,34] |

| Borylated ferrocenium (animal data) | Organotropism of cationic complexes | Liver/spleen/kidney predominant sinks | — | — | — | [66] |

| Representative (example) | Metabolic liability / processing | Intracellular fate & trafficking | Linker chemistry / trigger | Stability-/release-enhancing strategies | Key caveats (metabolism) | Representative refs (updated) |

| BPA / BPA-fructose | Minimal biotransformation; transporter-driven behaviour | Cytosolic pool; relatively rapid egress without sustained LAT1 | — | Formulation and scheduling to delay efflux | Heterogeneous LAT1; rapid washout | [8,10,14,23,40] |

| BSH | Negligible conversion; renal elimination | Largely extracellular | — | Encapsulation/conjugation | Limited cell entry | [1,3,11,12,23] |

| Metallacarborane/DNA-affine | Carborane inert; linker is liability | Risk of endo-lysosomal trapping; possible nuclear localisation | Stable amide/urea; steric shielding | Balance logP; add endosomal-escape motifs | Over-hydrophobicity → sequestration | [13,14,15,23,41,42,43,44,88] |

| Peptide/ligand conjugates | Proteolysis; endo-lysosomal degradation | Endocytosis; recycling vs degradation | Protease-resistant backbones; cleavable linkers | Cyclisation; PEG spacers; valency tuning | Premature plasma cleavage | [14,15,18,19,23,33,47,83] |

| PEGylated liposomes/dendrimers | Colloidal stability and corona drive fate; limited enzyme metabolism | Endosomal-lysosomal routing unless engineered | pH-responsive gates; cleavable spacers | Increase stealth; tune size/charge; endosomolytic features | RES processing if insufficient stealth | [11,15,16,17,23,48,49,50,51,52,56] |

| Functionalised MSNs | Biodegradation to silicic acid; corona-driven processing | Lysosomal residence if ungated | pH/enzyme-labile gatekeepers; ligand shells | Surface chemistry control; triggerable gates | Long-term retention if slow degradation | [20,21,23,53,54,55,56] |

| Cell-based carriers | Cellular processing of payload; no chemical metabolism of boron core | Deep tumour homing; sustained presence | Payload-specific | Optimise loading/release; preserve viability | Biological variability | [23,24] |

| Representative (example) | Primary elimination route(s) | Determinants of clearance | Organ retention / sinks | Excretion-optimising strategies | Key caveats | Representative refs (updated) |

| BPA / BPA-fructose | Renal (filtration) | Hydrophilicity; transporter-mediated tissue egress | Kidney exposure during infusion; transient tumour retention | Schedule vs tumour peak; delay efflux where feasible | Rapid washout in LAT1-heterogeneous tumours | [3,8,23,30,31,32,40] |

| BSH | Renal (rapid) | Extreme hydrophilicity; poor cell entry | Kidney; minimal tumour residence | Encapsulation/conjugation | High dosing without carriers | [1,3,11,12,23] |

| Peptide/ligand conjugates | Renal for small conjugates/catabolites; hepatobiliary if plasma-bound | Proteolysis; linker stability; receptor cycling | Lysosomes; liver (if opsonised) | Protease-resistant designs; tuned cleavable linkers | Premature cleavage in plasma | [11,14,15,18,23,33,47,83] |

| PEGylated liposomes / dendrimers | Predominantly hepatobiliary; renal for fragments | PEG density; size/charge; protein corona | Liver, spleen (MPS/RES) | Increase stealth; degradable matrices | Long-term retention if non-degradable | [2,11,16,17,23,48,49,50,51] |

| Functionalised MSNs | Hepatobiliary (slow); urinary for soluble products | Size/porosity; surface chemistry; corona; biodegradation | Liver/spleen; gradual degradation to silicic acid | Gatekeepers/ligands; design for biodegradation | Clearance timescale context-dependent | [20,21,23,53,54,55,56] |

| Cell-based carriers | Biological turnover; lymphatic/hepatic routes | Carrier viability; payload stability | Tumour phagocytes; lymph nodes; liver | Optimise loading/release; ensure viability | Biological variability; regulatory complexity | [23,24] |

| Historical organ distribution example (ferrocenium derivatives) | Mixed; organ sequestration → slow clearance | Cationic complex behaviour | Liver/spleen/kidney predominant sinks | — | Preclinical context | [66] |

| Representative (example) | Principal toxicity endpoints | Mechanistic drivers | Organs at risk | Mitigation strategies | Clinical/Preclinical notes | Representative refs |

| Boronophenylalanine (BPA) / BPA–fructose | Infusion-related symptoms (nausea, flushing); field-limited RT-like AEs during BNCT (mucositis, dermatitis) | Transporter-driven normal-tissue uptake (LAT1); exposure at irradiation if T/B suboptimal | Oral mucosa/skin in field; kidney (exposure during infusion) | PET selection; schedule to peak T/B; supportive care protocols | Systemic toxicity generally mild–moderate at clinical dosing with proper scheduling | [3,4,5,8,10,14,23,40,76,85,91,93] |

| Sodium borocaptate (BSH) | RT-like AEs in field; limited systemic toxicity | Extracellular distribution; blood concentrations at irradiation | Kidney (rapid renal handling); liver (minor) | Dose planning to minimise normal-tissue dose; consider carriers to improve selectivity | Conservative safety margins when scheduling is respected | [1,11,12,23,84,86] |

| Targeted peptides/ligand conjugates | Potential immunogenicity; off-target binding; infusion reactions (rare) | Proteolysis; receptor expression in normal tissues; endosomal trapping | Receptor-positive normal tissues; liver (if opsonised) | Protease-resistant designs; validate receptor maps; premedication/infusion-rate control | Risk profile depends on target expression and linker chemistry | [14,15,18,19,23,33,37,83,95] |

| PEGylated liposomes / polymeric dendrimers | Complement activation; hepatic/splenic deposition; infusion reactions | Protein corona → MPS (RES) uptake; insufficient stealth; cationic surfaces | Liver, spleen; blood (infusion) | Increase PEG density; near-neutral charge; graded dosing; endosomolytic features within safe range | Monitoring liver enzymes; mitigate CARPA-like events if relevant | [11,15,16,17,23,48,49,50,51,52,56] |

| Functionalised mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) | Inflammation with prolonged retention; long-term organ sequestration if slow degradation | Slow biodegradation to silicic acid; corona-modulated responses | Liver, spleen; reticuloendothelial system | Design for controlled post-treatment degradation; neutral corona; dose staggering | Favourable profiles when degradability and surface chemistry are optimised | [20,21,23,53,54,55,56] |

| Cell-based carriers (e.g., macrophages) | Immune activation/cytokine-related events; ectopic accumulation | Cell persistence/activation state; payload stability | Liver/spleen (clearance); lymph nodes; tumour microenvironment | GMP manufacturing; viability/release criteria; clinical monitoring | Preclinical studies show tumour homing with limited systemic redistribution of inert payloads | [23,24] |

| Imaging-oriented boron tracers (e.g., ^18F-labelled amino acids, sugars) | Low systemic toxicity at tracer doses | Transporter-mediated uptake; rapid clearance | Kidney; field-specific effects not applicable (diagnostic use) | Standard radiotracer safety; QC of radiochemistry | Useful for selection/scheduling; not therapeutic on their own | [8,38,39,40,48,57] |

| Historical ferrocene-based boron agents (preclinical) | Organ sequestration-related concerns | Cationic complex organotropism | Liver, spleen, kidney | Preclinical toxicity mapping; not for routine clinical use | Context for organ-level safety considerations | [66] |

| Tool / framework | Primary purpose | Typical inputs | Key outputs for BNCT | Use case in this review | Representative refs |

| Drug-likeness/BCS rules (RO5; Veber; BCS) | Rapid prescreen of solubility/permeability risk and formulation needs | Calculated physicochemical properties; class-based thresholds | Risk flags for absorption limits; oral bioavailability heuristics | Prioritise linker/scaffold variants for small boron agents | [29,30,31] |

| ADMETlab-style prediction (ADMETlab 3.0) | Batch prediction of ADME/T surrogates to rank candidates | SMILES/structure; descriptor set | Absorption/distribution/toxicity descriptors; comparative scores | Side-by-side evaluation of linker placements and polarity tuning | [96] |

| Transporter-aware modelling (LAT1 focus) | Assess transporter contribution vs passive permeation | Docking/LB models; ionisation; permeability estimates | Uptake likelihood via LAT1; interaction risk with transporters | Classify agents as transporter-dominant vs permeation-feasible | [10,14,33,47,87] |

| PET-informed PBPK | Time-aligned exposure modelling and irradiation scheduling | ^18F-BPA/sugar PET kinetics; plasma/biopsy boron; physiological priors | Tumour-to-blood trajectories; schedule windows; sensitivity analyses | Place neutron exposure at peak/plateau selectivity | [8,40,64,84] |

| Nano-clearance modelling (MPS/biodegradation) | Anticipate organ retention and elimination for carriers | Size/charge/PEG density; corona data; degradability parameters | Hepatobiliary vs renal balance; residence times; risk flags | Balance exposure with clearance; design degradability “timers” | [11,15,16,17,48,49,50,52,53,54,55,56] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).