1. Introduction

The high rate of urbanisation in South Africa has exerted unprecedented stress on cities, most of which have witnessed a significant rise in informal settlements. These settlements comprise over 10 per cent of the national population and are complex socio-economic ecosystems with poor infrastructure, insecure tenure, and poor service delivery [

1]. The national government has responded by initiating an electrification programme funded by grants to supply informal settlements with electricity. This programme aims to enhance household welfare, reduce the risk of fire due to the use of paraffin and unauthorised connections, and promote inclusive development.

These goals align with constitutional rights and developmental needs, but mitigate the fact that municipalities struggle with severe financial issues. Municipal revenues depend on electricity sales, which provide up to 40% of the operating revenues in certain councils [

2]. However, non-technical losses (NTLs) of electricity due to theft, meter tampering, and illegal connections are increasingly common in municipalities, especially in informal settlements [

3,

4].

The contradiction is evident: the government provides a grant to cover new electricity infrastructure in informal settlements, where municipalities experience difficulties recovering revenue. The question is whether electrification of informal settlements without similar reforms is beneficial, or whether grant funds could be used more wisely to refurbish old networks, which are experiencing decay in most cities. In this article, the author assesses both the positive and negative effects that electrification of informal settlements has on municipal revenues, while analysing options and providing strategic solutions.

2. Context: Informal Settlements and Urban Energy Poverty

Informal settlements are a historical representation of inequities, governance issues, and sophisticated migration and land occupation behaviours [

1]. Due to the extreme energy poverty experienced by numerous households, paraffin, candles, and biomass are used. These substances are linked to fires, respiratory diseases, and energy collection burdens for certain genders [

5]. Research results demonstrate that access to energy improves overall quality of life, decreases the risk of household exposure to harmful substances, and promotes social inclusion [

6]. Electrification is, therefore, considered a social need. Nevertheless, informal settlements have specific infrastructural and governance issues.

2.1. High Population Density

Informal settlements are too densely populated. Therefore, electricity supplies are overloaded, leading to a higher possibility that unlawful connections will be made. Formal electrical networks are also difficult to protect and install due to dense living conditions.

2.2. Irregular Layouts and Unplanned Land Use

Informal settlements are unplanned layouts, comprising disorganised paths and plots. This makes it challenging to install safe and compliant electrical systems. Such uncertainty adds to technical losses and maintenance issues.

2.3. Absence of Formal Street Addresses

In the absence of adequate addresses, municipalities have difficulty in registering customers, assigning meters, and developing accurate billing accounts. This makes it difficult to collect revenue and formulate bills for energy consumption.

2.4. Parallel Informal Governance Frameworks

Informal power brokers or community leaders are likely to control access to services that are not distributed as part of municipal systems, such as electricity. Such control could prevent accurate municipal billing, enforcement, and metering.

2.5. Ability to Pay Decreases with Poverty and Unemployment

Many families in informal settlements are below the poverty line and, therefore, face difficulties in making regular payments to the electricity company. This promotes dependence on illegal connections and could lead to missing payments, even for services that are provided on record.

2.6. Tenure Insecurity Makes Billing Difficult

Occupancy rights are not commonly enforced on residents, and thus, there can be confusion as to who pays the electricity bills. This deters relationships with formal service and compromises payment compliance in the long term.

Such circumstances render traditional utility plans ineffective. According to research conducted by the Energy for Growth Hub (2023) [

7], informal settlements typically use informal intermediaries to access services, leading to covert connections to the grid and alternative forms of payment. Municipalities are aware of these complexities but are legally compelled to offer simple services to maintain infrastructure, even in areas where the recovery of revenue is uncertain.

3. Government Grant Funding for Electrification

Electrification of informal settlements in South Africa is primarily funded through national grants, including the following:

Integrated National Electrification Programme (INEP);

Urban Settlements Development Grant (USDG);

Municipal Infrastructure Grant (MIG).

These grants are used to assist in the development of infrastructure, but do not support long-term operating or maintenance expenses, which municipalities are forced to cover. As Gaunt et al. (2012) [

8] point out, electrification increases the asset base but does not increase the capacity to collect revenue, causing structural deficits. The grants are understood by many municipalities as a free set of obligations to develop networks quickly, even in unstable, dense, or illegal settlements. Recent cases include the accelerated electrification programme of Nelson Mandela Bay [

9] and similar programmes in Johannesburg and eThekwini [

10,

11]. These projects tend to incorporate long-term liabilities, although they are popular politically.

4. Illegal Connections and Non-Technical Losses: A Persistent Revenue Challenge

NTLs refer to losses due to theft, meter tampering, unbilled energy consumption, inaccurate metering, and billing inefficiencies [

4]. South Africa has higher NTL rates than the global average, and in some municipalities, losses reach over 30% [

3]. Research indicates that informal settlements always have a high concentration of electricity theft due to the following points:

- (a)

Extreme poverty [

12]: When a large percentage of the population is poor, illegal connections to secondary power sources are used by many due to an inability to pay regular tariffs. This compromises local revenue and heightens the loss of networks.

- (b)

Lack of policing of illegal connections: There is inadequate enforcement capacity, which enables illegal hookups to continue unabated. Consequently, illegal use is propagated and accepted as the norm in most societies.

- (c)

Resistance to disconnection by the community: Residents usually resist disconnection attempts by utilities, as some individuals rely on illegal connections for daily survival. Such resistance complicates the ability to protect revenue over time.

- (d)

Presence of a so-called electric syndicate [

13]: Structured groups of people make a profit by laying illegal connections and securing a business. With these syndicates, a parallel electricity market is created, which decreases utility control and impacts formal revenue collection.

Municipalities report enormous losses of money due to the following reasons:

The city of Johannesburg regularly disconnects thousands of unauthorised lines, where whole transformers are found to be linked unlawfully [

14].

City Power seized a single operation of stolen cabling valued at R500,000 in Princess settlement [

15].

KwaDukuza Municipality wastes more than R1 billion every year [

16].

The rising rates of NTL lead to lower operating costs, transformer congestion, and energy balancing errors. Illegal links also cause life-threatening conditions, and recurrent deaths and fires have taken place in informal settlements across the country.

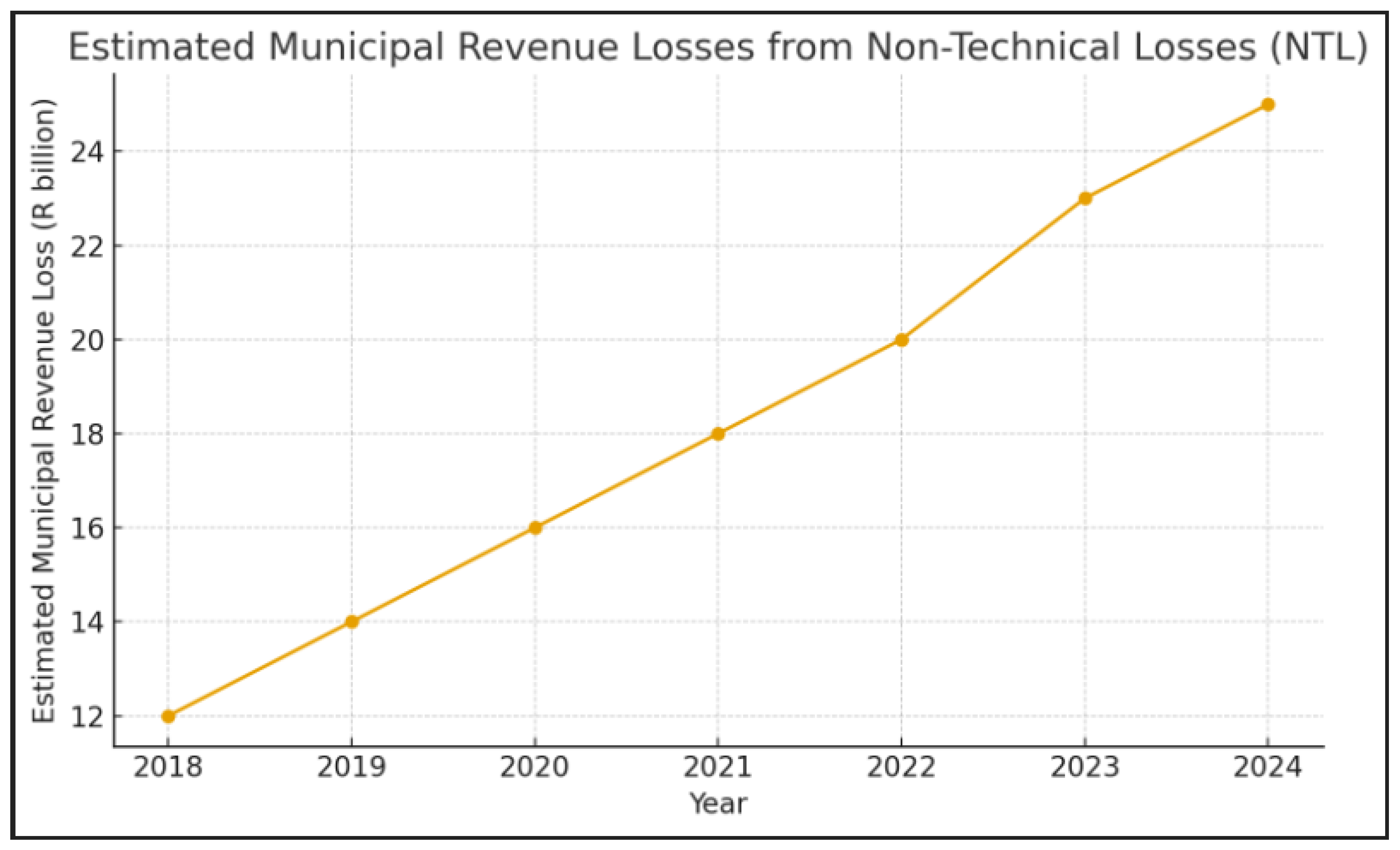

5. Graph: Estimated Municipal Revenue Losses from NTL

The following graph (downloadable) provides a hypothetical depiction of the increasing financial burden caused by NTL on South African municipalities.

Figure 1.

Estimated municipal revenue losses from non-technical losses (NTLs), 2018–2024.

Figure 1.

Estimated municipal revenue losses from non-technical losses (NTLs), 2018–2024.

These escalating losses illustrate the structural deficit faced by municipalities—losses from electrification programmes may worsen without revenue-protection interventions.

Table 1.

Key risks facing electrification in informal settlements.

Table 1.

Key risks facing electrification in informal settlements.

| Risk Factor |

Description |

Municipal Revenue Impact |

| Illegal connections |

Unauthorised tapping into the grid |

High NTL, reduced revenue |

| Overloaded transformers |

Excessive unmetered demand |

Equipment failure, costly repairs |

| Ageing infrastructure |

Old cables, substations, meter |

High energy losses and maintenance costs |

| Non-payment culture |

Resistance to paying for services |

Debt accumulation, declines in cash flow |

| Spatial informality |

Irregular layouts |

Billing and metering challenges |

| Crime and vandalism |

Cable theft, meter tampering |

Capital asset losses |

6. Impacts of Electrifying Informal Settlements on Municipal Revenue

6.1. Revenue Gains: The Potential Upside

Electrification has some potential financial benefits.

- (a)

Formalising Consumption

One of the advantages of opening up legal access to power in informal settlements is the formalisation of electricity consumption. In this case, prepaid meters provide a convenient structural tool to facilitate formalisation because households pay for electricity prior to consumption, which minimises the chances of debt accrual. The evidence from J-PAL (2016) [

17] demonstrates that prepaid meters can significantly reduce unpaid energy consumption, which proves that municipal revenue streams can be stabilised if communities learn to use and accept this technology.

Another benefit is reduced network losses. Unofficial or unlawful networks are not always well-built; they can become clogged, unsafe, and result in technical loss and constant crashes. Replacing them with legally and professionally installed connections will reduce technical losses and enhance the reliability of the whole system. This yields a safer and predictable power network for residents as well as utilities.

Long-term economic development can also result from electrification. The availability of reliable electricity will help households and small businesses to increase their economic output, from refrigeration and welding to retail and home-based businesses. In the long run, this expansion will boost local economic productivity and could build a municipal tax and revenue base.

Finally, an increase in formal access increases the social legitimacy of these municipalities. Trust increases when communities feel that the government is offering reliable and fair services. According to Tshalikala (2025) [

18], enhanced social contracts may lead to increased compliance, less conflict, and better revenue protection in the long term. These benefits, however, only become a reality when supported by strong governance and protection mechanisms. This has not been the case in most of the municipalities.

6.2. Revenue Losses: The Downside

- (a)

High NTLs undermine billing

Electrification enhances energy supply but does not always sell. It has been demonstrated that informal settlements equipped with electricity tend to become unsafe as illegal connections are formed in situations where enforcement is lax [

12].

Unlawful connections overload transformers, feeders and distribution lines, causing frequent outages and premature equipment degradation. According to Khonjelwayo and Nthakheni (2021) [

19], such failures are expensive to fix and, in many cases, demand the early replacement of infrastructure. This augments city spending and provides no attendant income.

After establishing infrastructure, municipalities are responsible for maintaining, repairing, and monitoring operations. In cases where electricity costs are not paid for by households, energy is used without a corresponding stream of income, increasing the financial pressure on municipalities. This results in a structural imbalance of service demand and funds over a period of time.

Electrification funded by grants increases the geographic scope that utilities must serve, monitor, and maintain. Although national grants fund the capital expense of electrification, the municipalities assume the long-term costs of maintenance, staffing, metering, and revenue management. These costs cannot be sustained over a large geographical footprint unless there is an equal growth in revenue.

Any attempt to cut off illegal links or impose payments is often met with opposition by inhabitants who depend on electricity as a means of livelihood. Mthethwa (2025) [

20] notes that political leaders can overlook disconnection processes, particularly during election periods, as a strategy. This negates municipal power and damages long-term revenue protection measures. Overall, the electrification of high-risk environments has low revenue recovery and high operational costs.

7. Is Electrification Wise? A Critical Evaluation

7.1. Political and Social Imperatives

Electrification fulfils the following points:

Constitutional rights;

Poverty-reduction goals;

Safety improvements;

Urban citizenship rights [

21].

Therefore, halting electrification is both politically infeasible and socially undesirable.

7.2. Fiscal Reality

The financial situation of municipalities is becoming worse. The National Treasury records a large amount of insolvency, with the collapse of electricity revenue being one of its drivers. The existing system, which aims to build more infrastructure past the point of declining revenue, is unsustainable.

Electrification is only “wise” if paired with the following plans:

Otherwise, electrification only serves to deepen municipal financial crises.

8. International and Technological Solutions

Technological innovations offer the following opportunities:

- (a)

Smart meters with tamper detection

AMI-enabled smart meters significantly reduce electricity theft through real-time monitoring and automated disconnection [

22].

Glauner et al. [

23] highlight AI’s potential to detect patterns in theft.

Studies show that off-grid systems are more sustainable for some densified informal settlements [

5].

Caprotti et al. [

24] argue for grid innovations that are co-designed with communities.

9. Policy Considerations and Strategic Options

Option 1: Continue Electrification as Is (High Risk).

This method meets political demands but increases the city’s financial shortages.

Option 2: Grant Reallocation for Network Refurbishment (Moderate Risk).

Refurbishment might be a political issue; however, it can use grant funds to minimise technical losses.

Option 3: Mandatory Revenue Protection of Electrification (Low Risk).

This blended model would require all electrification projects to implement the following:

Smart meters;

Tamperproof enclosures;

Pole-top metering;

Active NTL monitoring;

Community partnerships.

This aligns with global best practice and enhances revenue sustainability.

10. Policy Recommendations

To enhance the sustainability of electrification in informal settlements, a combination of technological, institutional, and policy reforms should be implemented to curb cases of theft, which cause strain on infrastructure and loss of revenue. This is based on the fact that, for informal electrification projects, the introduction of revenue protection technologies is a requirement because conventional grids are highly prone to unauthorised connections. Placing protection systems, including sealed distribution boxes and automated disconnect devices, in place ensures that the process of electrification is followed by the presence of systems that protect the streams of municipal revenue. This will result in a uniform national standard whereby municipalities cannot implement a weak low-voltage network in high-risk regions.

Secondly, pole-mounted or cluster metering systems can be implemented, which physically place the metering infrastructure above the reach of tampering, significantly decreasing alterations to metering infrastructure and meter bypassing. These systems have proven successful in places such as Johannesburg, where high meters minimise contact manipulation as well as damage by technicians. Cluster meters also provide a centralised approach to monitoring losses as they correspond to a cluster of households, as opposed to checking individual houses.

In addition to physically protecting infrastructure, AI and intelligent systems should be used by municipalities to detect theft in real time. Variations in consumption, voltage, and potential bypassing can be traced using AI-based systems, which have significantly higher precision compared to manual methods. A real-time understanding can enable utilities to respond before losses become too high and help focus enforcement. The use of AI-based detection is increasing in revenue protection methods worldwide, and informal settlements could modernise the approach to loss reduction in South Africa.

Concurrently, electrification must not take place outside of grid upgrades. The electrification of informal settlements, in combination with network refurbishment, can stabilise supply, eliminate transformer overloads, and increase the life of assets. Numerous failures in electrification result from the attempt to connect large, unplanned communities with old, previously installed infrastructure. By contrast, systems with coupled investment do not collapse due to increased demand.

Since technology cannot resolve behavioural and social aspects of theft, municipalities are advised to institutionalise community-based models of metering that have been tested in pilot projects. Meter custodianship with community support, energy ambassadors, and cooperative-based prepaid systems has helped reduce vandalism and established a shared responsibility for infrastructure. Compliance is raised when residents are considered to have a share in electrification and feel they have contributed to it. Nonetheless, identification and social participation cannot be effective before enforcement. City authorities need to make revenue protection departments more powerful by equipping them with specialised inspectors, legal devices, and interdepartmental coordination. Such units require the right and capability to destroy illicit networks, convict syndicates, and carry out educational programmes to strengthen legal electricity use.

Municipalities should test off-grid and hybrid mini-grids in settlements where grid electrification is neither safe nor workable. A solar–hybrid system can offer power reliably without subjecting the central grid to losses. Such options align with global off-grid trends, as they lessen the strain on congested municipal networks. Lastly, national grant terms should be altered to maintain these reforms, favouring lifecycle asset management over initial electrification. Maintenance and technologies that protect infrastructure should also be funded because this approach will help keep infrastructure running and economically viable.

11. Conclusions

The electrification of informal settlements is a key social issue aligned with the constitutional rights and objectives of poverty reduction. Nevertheless, this study shows that existing grant-based strategies, which focus on infrastructure development without relevant revenue insurance systems, are not economically viable for municipalities already under significant fiscal strain. Municipal revenues are being damaged by high levels of non-technical losses, illegal connections, and vandalism of infrastructure, which is causing high operating costs. The core reorganisation of electrification programmes, including the introduction of smart meters and AI-based theft detection, community engagement, and intensified enforcement capabilities, needs to be established to guarantee long-term viability. Also, grants must be used to fund lifecycle asset management as opposed to only financing the initial capital expenditure. It is in this context that electrification contributes to urban financial crises rather than promoting sustainable urban development. Future policies should aim to find a compromise between social justice and fiscal accountability through technologically advanced, community-based, and institutionally sound implementation designs.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Atkinson, C.L. Informal Settlements: A New Understanding for Governance and Vulnerability Study. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, D. How Can South African Municipalities Respond to the Challenges of Sustainable Electricity Provision to Urban Households Now and in the Future? 2018. Available online: https://samsetproject.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Dissertation_Final_-_Daniel_Kerr_P17233346.pdf.

- Louw, Q.E.; Eng, P.T. The Impact of Non-Technical losses: A South African Perspective Compared to Global Trends. South African Revenue Protection Convention 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335337986_The_Impact_of_Non-Technical_losses_A_South_African_perspective_compared_to_global_trends (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Carr, D.; Thomson, M. Non-Technical Electricity Losses. Energies 2022, 15, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuku, B. Rethinking South Africa’s household energy poverty through the lens of off-grid energy transition. Dev. South. Afr. 2024, 41, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runsten, S.; Fuso Nerini, F.; Tait, L. Energy provision in South African informal urban Settlements—A multi-criteria sustainability analysis. Energy Strategy Rev. 2018, 19, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy For Growth, Hub. Recognising the Energy Access Challenges of Informal Urban Communities in Africa—Energy for Growth Hub. Energy for Growth Hub. 2023. Available online: https://energyforgrowth.org/article/recognizing-the-energy-access-challenges-of-informal-urban-communities-in-africa (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Gaunt, T.; Salida, M.; Macfarlane, R.; Maboda, S.; Reddy, Y. Experience, Opportunities and Challenges Informal Electrification in South Africa Mark Borchers. 2012. Available online: https://www.cityenergy.org.za/uploads/resource_22.pdf.

- Central News Online. Nelson Mandela Bay Accelerates Electrification in Gomora Informal Settlement. Central News. 2025. Available online: https://centralnews.co.za/nelson-mandela-bay-accelerates-electrification-in-gomora-informal-settlement (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Joburg Pulse. City Power Cuts Illegal Connections to Reduce Load on the Grid. Joburg.org.za. 2024. Available online: https://joburg.org.za/media_/Newsroom/Pages/2024%20News%20Article/August/City-Power-cuts-illegal-connections-to-reduce-load-on-the-grid.aspx (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Dawood, Z. eThekwini Municipality’s Losing the Battle Against Electricity Thieves. The Post. 2022. Available online: https://thepost.co.za/dailynews/news/kwazulu-natal/2022-10-03-ethekwini-municipalitys-losing-the-battle-against-electricity-thieves (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Geyevu, M.; Mbandlwa, Z. Economic conditions that leads to illegal electricity connections at Quarry Road Informal Settlement in South Africa. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2022, 37, 11069–11078. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Economic+conditions+that+leads+to+illegal+electricity+connections+at+Quarry+Road+Informal+Settlement+in+South+Africa.+Ms.+Mawuena+Geyevu&btnG= (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Tshabalala, C. Non-Payment of Electricity Services in South Africa: Analysing the Consumers, Utilities, and Institutions. SSRN Electron. J 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikalange, S. 13 Illegally Connected Transformers Found in Kya Sands Settlement. TimesLIVE. 2024. Available online: https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2024-08-14-13-illegally-connected-transformers-found-in-kya-sands-settlement/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Mafu, H. City Power Cuts Illegal Connections, and Confiscates R500k Worth of Cables at Princess Settlement. The Star. 2025. Available online: https://thestar.co.za/news/2025-01-22-city-power-cuts-illegal-connections-and-confiscates-r500k-worth-of-cables-at-princess-settlement/?utm_source=chatgpt.com#google_vignette (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Magubane, T. Electricity Theft and Non-Payment by Consumers Leads to R1 Billion Loss for KwaDukuza Municipality. Mercury. 2025. Available online: https://themercury.co.za/2025-10-22-electricity-theft-and-non-payment-by-consumers-leads-to-r1-billion-loss-for-kwadukuza-municipality/.

- J-PAL. Prepaid Electricity Meters to Decrease Electricity Use and Recover Utility Revenue in South Africa|The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab. The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). 2016. Available online: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/evaluation/prepaid-electricity-meters-decrease-electricity-use-and-recover-utility-revenue-south.

- Tshalikala (2025).

- Khonjelwayo, B.; Nthakheni, T. Determining the causes of electricity losses and the role of management in curbing them: A case study of City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality, South Africa. J. Energy South. Afr. 2021, 32, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthethwa, S. Illegal Connections Exposed: City Power’s Action in Crown Informal Settlements. Whats on G. 2025. Available online: https://whatson.gauteng.net/illegal-connections-city-power-informal-settlements/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Tshabalala, T.; Davies, M.; Hajer, M.; Hoffman, J. Off-grid electricity imaginaries: Tracing urban citizenship in Cape Town’s informal settlements. Urban Stud. 2025, 00420980251368672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Javaid, N.; Mahmood, A.; Raza, S.M.; Qasim, U.; Khan, Z.A. Minimising Electricity Theft Using Smart Meters in AMI. arXiv 2025, arXiv:1208.232. [Google Scholar]

- Glauner, P.; Meira, J.A.; Valtchev, P.; State, R.; Bettinger, F. The Challenge of Non-Technical Loss Detection Using Artificial Intelligence: A Survey. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2017, 10, 760–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprotti, F.; de Groot, J.; Butler, C.; Pailman, W.; Mathebula, N.; Schloemann, H.; Densmore, A. Urban innovation in the informal city: Overlapping infrastructures, co-production and sector coupling in a South African informal settlement. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1654705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, X.; Kerr, D. Informal Settlements Electrification and Urban Services. 2016. Available online: https://samsetproject.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/SAMSET-UCL-Informal-Settlements-Electrification-and-Urban-Services-Dec-2016.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).