Introduction

Major depressive disorder often takes a difficult course in teenagers and young adults. Many carry a history of bullying, family discord, or other trauma and withdraw socially while showing little change after standard selective-serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Waiting several weeks for an SSRI to work can be risky when suicidal thoughts are present, and animal data suggest that severe stress quickly disrupts synaptic connections the monoaminergic drugs do not repair [

1].

Interest has therefore shifted to medicines that act on the brain's glutamatergic system. Ketamine proved that blocking the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor can, within hours, set off an α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)-driven surge of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and mTOR signalling, with fast relief of mood symptoms [

2,

3]. Unfortunately, ketamine infusions are expensive, require monitoring, and may cause dissociation.

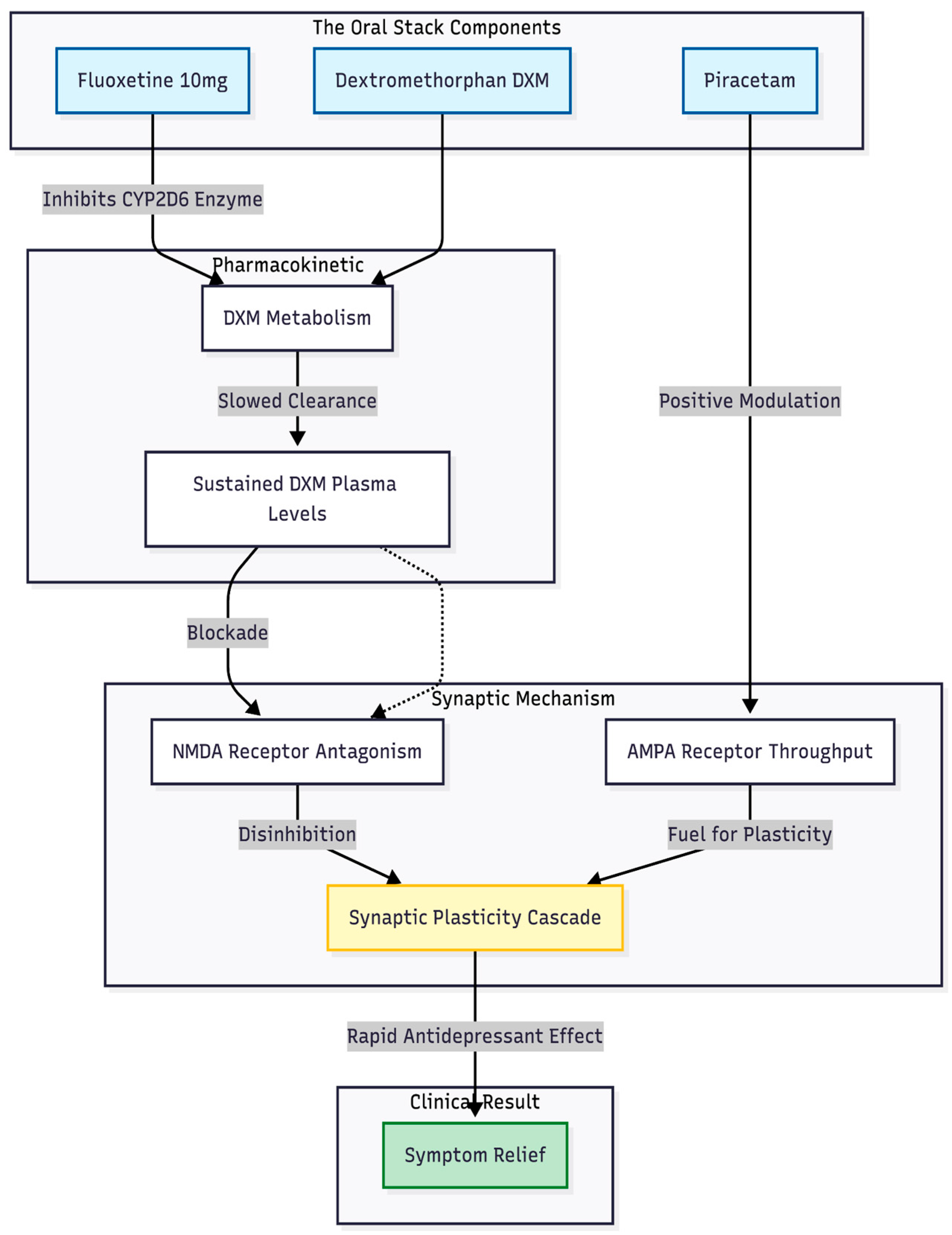

Cheung [

4] described an oral alternative that was made to act like the biology of ketamine. The plan combines dextromethorphan, an NMDA antagonist, with a CYP2D6 inhibitor such as fluoxetine or bupropion to slow dextromethorphan metabolism, and adds piracetam to enhance AMPA throughput. In effect, the NMDA "brake" is released while the AMPA "accelerator" is pressed, using inexpensive drugs already found in most pharmacies [

4,

5].

The following report describes three consecutive patients—two adolescents and one young adult—whose depression was marked by trauma, paranoia, and suicidal thinking. All began the fully oral combination of dextromethorphan, fluoxetine, and piracetam in a routine outpatient setting. Their courses offer early evidence that targeting the NMDA–AMPA pathway may deliver rapid symptom relief and functional recovery when conventional approaches have failed.

Methods

This retrospective review examines three consecutive patients—two adolescents and one young adult—seen in a private outpatient psychiatry clinic for severe major depressive disorder. All three received an off-label combination sometimes called the Cheung glutamatergic regimen, which pairs dextromethorphan (DXM) with a CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressant and adds piracetam. Before treatment began, each patient (and a parent or guardian when indicated) discussed the experimental nature of the plan, its possible risks and benefits, and signed a written consent form. The chart review was conducted under the clinic's quality-improvement policy, which allows anonymised publication of clinical observations.

Progress was followed at routine visits. Patients completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) at baseline and at successive appointments, providing a numeric estimate of depressive severity. The treating psychiatrist recorded changes in mood, suicidal thinking, school or work attendance, and social engagement. For the purpose of this report, the primary endpoint was the change in PHQ-9 score; secondary observations included any improvement in everyday functioning and the presence or absence of adverse effects.

Case Presentation

Case 1

A 20-year-old woman in her third year of university, majoring in film and creative writing, was first seen on 12 November 2025 at a private outpatient clinic in Hong Kong. Three nights earlier she had experienced an intense emotional collapse: she wept until dawn, could not regain composure, and felt as though everyone and everything around her was threatening. Since August she had struggled with thoughts of self-harm, but the November episode marked a clear escalation.

Her psychiatric history was brief. During secondary school she had twice consulted a psychiatrist after a series of interpersonal blows—a friend's betrayal, public rejection by a romantic interest, and persistent social isolation at school. No formal diagnosis had been made at that time, and the only medication she had ever tried was a short course of methylphenidate.

At assessment she appeared exhausted and tearful yet cooperative. Sleep was fragmented; academic work was being handed in sporadically. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scored 20 (severe depression) and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 scored 12 (moderate anxiety). No psychotic features or substance use were disclosed.

Initial Intervention

That same evening an oral, glutamatergic-centred programme was started, all doses scheduled at night:

dextromethorphan 30 mg (two 15 mg tablets) for NMDA antagonism

fluoxetine 10 mg to slow dextromethorphan metabolism via CYP2D6 inhibition

piracetam 600 mg (half of a 1 200 mg tablet) to enhance AMPA throughput

risperidone 0.5 mg

lemborexant 2.5 mg to consolidate sleep

alprazolam 0.25 mg and zolpidem 0.25 mg, both prescribed on a strictly "as-needed" basis

The patient and her parents were briefed on off-label status, early warning signs of serotonin toxicity, and the importance of weekly check-ins.

Two-Week Review

She came back on November 26, 2025, looking rested and much calmer. She said that waves of sadness still came up, but they didn't bother her as much as they used to. Also, thoughts of hurting herself had moved to the back of her mind. She was going to class, finishing her homework on time, and feeling less "on edge" around other people. The new scores showed that PHQ-9 = 15 (moderate depression) and GAD-7 = 6 (mild anxiety). There were no signs of dissociation, blood pressure spikes, or any other bad effects.

Given the good tolerance and partial response, doses were adjusted that day: dextromethorphan was doubled to 60 mg nightly, piracetam to 1 200 mg nightly, while fluoxetine, risperidone, and lemborexant were kept unchanged; "as-needed" anxiolytics remained available.

Early Outcome

By the end of week two the patient had achieved a meaningful clinical improvement: emotional reactivity was blunted, suicidal ideation was sporadic and controllable, and academic as well as social functioning were recovering. Treatment continued with fortnightly follow-up. At the time of writing she had experienced no hypertensive episodes, psychotomimetic effects, or other significant side-effects.

This case points to the potential for a fully oral combination of dextromethorphan, a CYP2D6 inhibitor, and an AMPA modulator to deliver rapid symptom relief in trauma-linked depression, warranting further systematic study.

Case 2

A 17-year-old Form-5 student, taking Biology and Geography, was first seen on 31 October 2025 at a private clinic in Hong Kong. He described a steady slide into low mood that had begun the previous February and worsened through Forms 3 and 4. Two longstanding family tensions dominated the history: his parents had divorced when he was in Form 1, an event he still felt "shook everything," and, more recently, he had struggled with discomfort over his mother's new relationships. A brief church-based romance had ended before the current school year but did not appear to be a major trigger.

Past records showed crying spells, episodes of school refusal, one hospital admission for depressive disorder, and follow-up at both a public service and a private clinic. He had been given sertraline and later melatonin but had stopped both on his own. By late October he was back at school, yet teachers reported irritability and poor communication with his mother. Academic workload was not a pressing concern.

On examination he was polite, made eye contact, and denied suicidal thoughts. Initial screening scores were PHQ-9 = 20 (severe depression) and GAD-7 = 12 (moderate anxiety).

Initial Treatment

That evening a night-time, glutamatergic-oriented schedule was started:

dextromethorphan 30 mg (two 15 mg tablets) for NMDA modulation

fluoxetine 10 mg to slow dextromethorphan metabolism via CYP2D6 blockade

piracetam 600 mg (half of a 1 200 mg tablet) to enhance AMPA signalling

quetiapine 12.5 mg for sleep and mood stabilisation

All medication was taken after supper to minimise daytime effects. The family were advised about off-label use, early warning signs of serotonin excess, and the plan for close follow-up.

Four-Week Review

On 29 November 2025 he returned with a markedly brighter affect. He reported full school attendance, fewer flashes of irritability, and better exchanges with classmates. Study periods were productive, and although he occasionally overslept, he could wake without difficulty. His mother confirmed a clear lift in initiative and overall mood. Repeat scales showed PHQ-9 = 3 and GAD-7 = 1. No dissociation, blood-pressure increase, or troublesome sedation had occurred.

Because the response was robust, the core doses were left unchanged. L-glutamine 500 mg nightly was added to support glutamate turnover, while dextromethorphan (30 mg), fluoxetine (10 mg), piracetam (600 mg), and quetiapine (12.5 mg) were continued.

Early Outcome

Within one month this adolescent moved from severe depressive symptomatology to clinical remission using a low-dose oral combination of dextromethorphan, fluoxetine, and piracetam, later supplemented with glutamine. The improvement appeared across school performance, family interaction, and subjective mood, and no significant adverse effects emerged. He remains under routine outpatient review.

Case 3

A 14-year-old girl in Form 2 was brought to a private psychiatric clinic in Hong Kong on 29 September 2025. She had been unhappy since the start of the school term and had begun to show clear depressive symptoms while still attending classes. Nights were often restless; she lay awake turning old events over in her mind. During lessons she found it hard to focus and, at times, was convinced classmates were talking about her both in person and online, even though she had no proof. On 4 September she began hearing a harsh inner voice that criticised her, but she could usually push it away.

The background revealed sustained bullying in Form 1. In the current year she was placed in a classroom next door to some of the former bullies. The school was highly competitive, many pupils had transferred in, and her grades were only average, which increased the pressure she felt. Shortly before the clinic visit she had been taken to Tuen Mun Hospital after cutting her wrist. She refused psychiatric admission and was discharged without medication. Screening at the first outpatient appointment gave a PHQ-9 score of 19 and a GAD-7 score of 17, both in the severe range.

Night-time treatment started immediately. Fluoxetine 10 mg was chosen to lift mood and, by blocking CYP2D6, to serve later as a metabolic "protector." Low-dose risperidone 0.5 mg was added for the psychotic features and general mood stabilisation.

When she returned on 15 October 2025—about two weeks later—she said school was "ok" in spite of numerous tests. She no longer felt watched by her peers; worries surfaced only when she thought about examinations before falling asleep. The auditory hallucinations had vanished. Repeat scores showed PHQ-9 = 6 and GAD-7 = 8. Medication was left unchanged.

The next review, on 12 November 2025, came during examination week. Marks were lower than she wanted and she was thinking about changing schools. Memories of the bullying still intruded at bedtime, often followed by nightmares, yet there were no new psychotic symptoms. PHQ-9 dropped to 7 and GAD-7 to 6, both below clinical cut-off. At this point an oral glutamatergic layer was added: dextromethorphan 30 mg nightly (two 15 mg tablets) and piracetam 600 mg nightly (half of a 1 200 mg tablet), while fluoxetine 10 mg and risperidone 0.5 mg were continued.

On 9 December 2025 she reported feeling "ok" and was attending school regularly; she might transfer next term but no longer dwelt on past events. Occasional nightmares persisted but did not interfere with daily life. Screening scores had stabilised at PHQ-9 = 6 and GAD-7 = 6. The combination of dextromethorphan, piracetam, fluoxetine, and risperidone was well tolerated: there were no dissociative sensations, blood-pressure rises, or other adverse effects. She remains in routine outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

In this small series we followed three young people—two adolescents and one young adult—whose depression, anxiety and trauma symptoms had resisted standard care. Each was offered an oral combination first described by Cheung: night-time dextromethorphan (DXM), morning fluoxetine at CYP2D6-inhibiting doses, and daytime piracetam. All three patients showed a degree of improvement that had not been achieved with previous selective-serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, mood stabilisers or antipsychotics. Symptoms that usually move only after weeks of treatment—paranoia, intrusive memories, suicidal thinking—began to soften within days and were clearly better by the second or fourth week, depending on the case. Such speed is in line with what is seen after intravenous ketamine and suggests that the oral stack is tapping the same NMDA-to-AMPA plasticity cascade [

4,

6].

DXM was the pivotal drug. On its own the molecule is cleared too quickly to sustain NMDA blockade, but a low dose of fluoxetine (10 mg) slowed metabolism enough to keep active levels in the therapeutic window. This strategy copies the pharmacokinetic trick built into the fixed-dose tablet dextromethorphan-bupropion [

5]. Piracetam was included to boost AMPA throughput, providing the "fuel" once NMDA receptors were briefly silenced. Cheung [

4] argues that this push-pull—blocking NMDA, driving AMPA—recreates the key steps of the ketamine cascade, and the clinical timelines in our patients support that view (

Figure 1).

Trauma was central to every presentation. Two patients crashed after bullying and family rejection; another carried chronic intrusive memories. In each case fear-coloured ruminations and hypervigilance eased quickly once the glutamatergic layer was added, consistent with pre-clinical work showing that NMDA modulation can speed extinction of traumatic memories [

7]. Importantly, urges to self-harm fell in parallel, echoing ketamine's well-documented anti-suicidal effect.

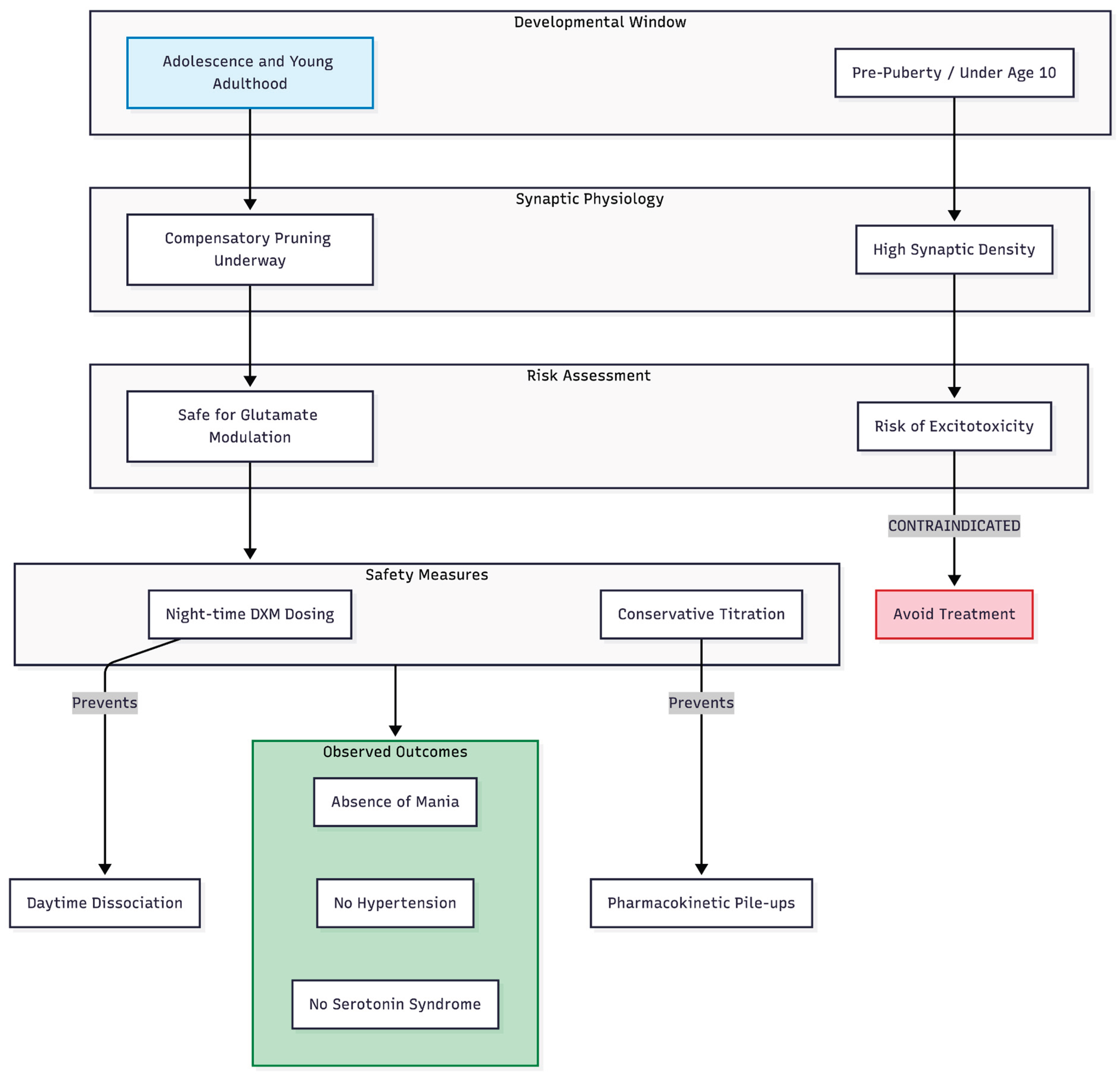

Figure 2.

Developmental safety logic and protocol safeguards. The regimen is specifically targeted at patients post-puberty, where cortical pruning has reduced the risk of excitotoxicity inherent in younger children (under age 10). Safety is further ensured through night-time dosing of DXM to minimize dissociation and conservative titration to prevent serotonin syndrome or hypertensive events.

Figure 2.

Developmental safety logic and protocol safeguards. The regimen is specifically targeted at patients post-puberty, where cortical pruning has reduced the risk of excitotoxicity inherent in younger children (under age 10). Safety is further ensured through night-time dosing of DXM to minimize dissociation and conservative titration to prevent serotonin syndrome or hypertensive events.

Age matters when manipulating glutamate. The two adolescents in this series were past puberty, a stage when synaptic density begins to fall in autism-spectrum samples and in typical development [

8]. Cheung's review on developmental timing warns that the same drugs could be harmful before age 10, when synaptic counts remain high and excitatory drive risks excitotoxicity [

9]. Our favourable outcomes, coupled with an absence of hypertension, dissociation or mania, suggest the regimen can be safe once cortical pruning is underway. Night-time DXM (30–60 mg) probably helped by limiting daytime dissociation and minimising overlap with the activating properties of fluoxetine.

No patient showed evidence of serotonin syndrome despite the SSRI–DXM pairing, perhaps because doses were kept low and titrated only after clinical review. This observation matches recommendations in Cheung's optimisation paper, which emphasises conservative dosing and symptom-led adjustments to avoid pharmacokinetic "pile-ups" [

10].

Taken together, these cases point to a useful outpatient alternative when intravenous ketamine is unavailable or unaffordable. An inexpensive, fully oral stack—DXM to provide the NMDA "spark," fluoxetine to hold that spark in place, and piracetam to amplify the downstream AMPA surge—brought rapid, broad and durable relief in conditions that had resisted conventional drugs. Larger, controlled trials are needed, but the present experience suggests that targeting the glutamatergic bottleneck of synaptic plasticity could open a new lane in everyday mood-disorder practice [

11].

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients (or their legal guardians where applicable) for publication of this case series and any accompanying images/figures.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Duman, RS; Aghajanian, GK; Sanacora, G; et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nature Medicine 2016, 22, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, RM; Cappiello, A; Anand, A; et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry 2000, 47, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanos, P; Moaddel, R; Morris, PJ; et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature 2016, 533, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: Proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B; Bunn, H; Santalucia, M; et al. Dextromethorphan-bupropion (Auvelity) for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 2023, 21, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, H; Iijima, M; Chaki, S. Involvement of AMPA receptor in both the rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in animal models of depression. Behavioural Brain Research 2011, 224, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duek, O; Korem, N; Li, Y; et al. Long term structural and functional neural changes following a single infusion of ketamine in PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 1648–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G; Gudsnuk, K; Kuo, SH; et al. Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron 2014, 83, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. Timing is everything: Why the Cheung glutamatergic regimen is contraindicated in young children with autism but promising after puberty. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Clinical experience and optimisation of the Cheung glutamatergic regimen for refractory psychiatric diseases. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Cheung's regimen series: Successful conversion from one dose of esketamine to a low-cost oral ketamine-class glutamatergic regimen in treatment-resistant depression and OCD. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).