Introduction

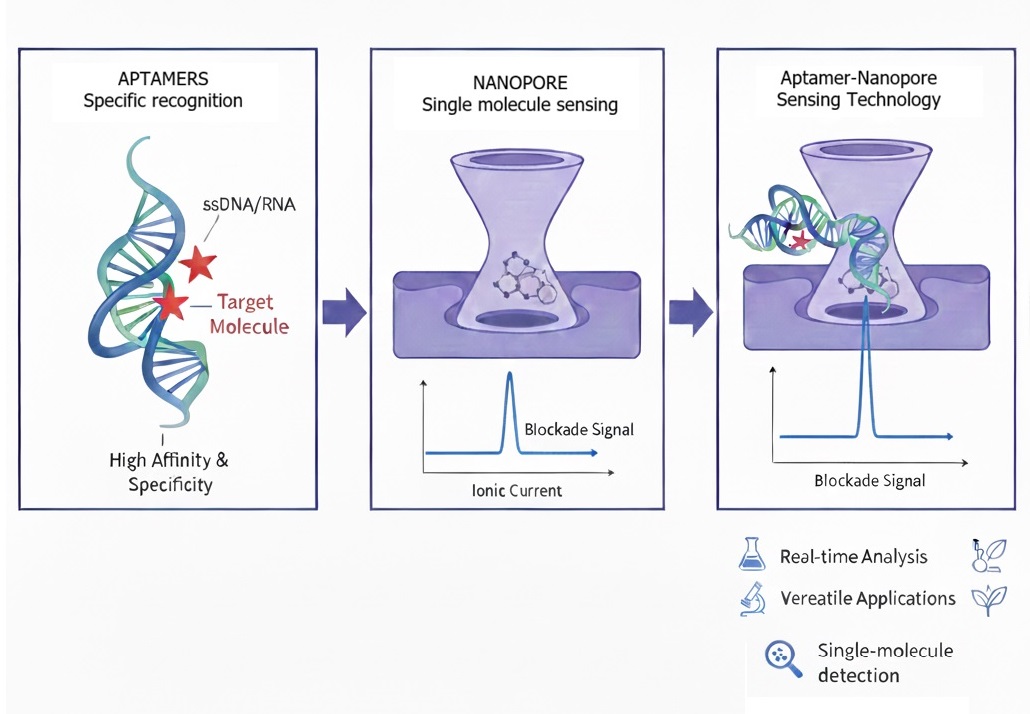

Aptamers are short, single-stranded oligonucleotides—either DNA or RNA—that fold into unique three-dimensional conformations, allowing them to bind selectively to specific molecular targets ranging from small ions and metabolites to large proteins and even whole cells. Their remarkable affinity and specificity, comparable to that of antibodies, stem from their structural adaptability and the fine-tuning possible through in vitro selection procedures such as SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment). Due to their thermal stability, chemical versatility, and reusability, aptamers have rapidly gained traction as biorecognition elements in analytical, diagnostic, and therapeutic applications. (Keefe et al., 2010; Sett et al., 2017; Simon et al., 2019)

Nanopores, on the other hand, represent a breakthrough in single-molecule detection technology. These nanometer-scale orifices—either biological (such as α-hemolysin) or solid-state (such as silicon nitride or graphene)—enable the direct, label-free detection of analytes via modulation of ionic current, when molecules traverse or interact within the pore. (T. Li et al., 2015; Winters-Hilt, 2007)This approach allows real-time analysis with extraordinary sensitivity, often down to the level of individual molecules. The precise control of pore geometry, surface chemistry, and applied potentials has further expanded nanopore platforms into powerful tools for sequencing, biomolecular detection, and high-throughput molecular diagnostics. (Lv et al., 2022)

When an analyte such as DNA, RNA, protein, or small molecule interacts with the nanopore, it temporarily disrupts the ionic current, producing a unique electrical signature that reflects its size, charge, and conformation. The integration of aptamers with nanopore technology represents a promising frontier in biosensing, merging the molecular recognition precision of aptamers with the high-resolution electrical readout of nanopores. In recent years, this hybrid platform has evolved into a versatile sensor system capable of detecting diverse analytes with single-molecule sensitivity and rapid, multiplexed signal output. Yet, despite these advances, challenges remain in nanopore surface functionalization, signal standardization, and reproducibility under complex biological conditions.(Sze et al., 2017) This review aims to highlight the recent developments, emerging trends, and integration strategies shaping the next generation of aptamer-based nanopore sensors—technologies poised to redefine rapid diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and molecular bio analytics.

Tuning of Aptamer Selection for Nanopore Applications

There are certain improvements or modifications required for SELEX to be compatible for nanopore applications. There are specific favorable sequences which retain unique folding structure and binding efficiency under specific conditions (high salt, electric field and confined geometry). Nanopore assisted selection consists of a nanopore readout (single molecule current) as the partitioning/selection signal – which helps to collect sequences that exhibit target-dependent signature sequences. This method can directly enrich the sequences that are “visible” in nanopore sensors. (Quint et al., 2024; Reynaud et al., 2020)

High-throughput SELEX makes it possible to deliberately select aptamers that are not only high-affinity binders but also better suited to the physical and functional constraints of nanopore sensing. By coupling massively parallel sequencing and advanced analytics with modified selection conditions, the process can be tuned so that aptamers remain structurally stable and discriminate under the high-ionic-strength, voltage-driven environments typical for nanopores. (Feng et al., 2025) High-throughput SELEX allows very large libraries to be screened and monitored across selection rounds, dramatically increasing the chance of discovering aptamers that retain function when confined, tethered, or partially threaded through a nanopore. Deep sequencing of intermediate pools reveals sequence families and structural motifs that persist under stringent conditions, helping to prioritize candidates with robust folding and target recognition compatible with nanopore assays.

Because selection rounds can be run directly under nanopore-like buffer, voltage, and crowding conditions, high-throughput formats support “environment-matched” evolution of aptamers. This means ionic strength, pH, and co-factors can be adjusted to mimic nanopore operation, enriching sequences that maintain affinity and structural integrity during translocation or surface immobilization. (Dupont et al., 2015) Artificial intelligence (AI) has recently emerged as a transformative and effective tool in designing aptamers that are structurally and functionally optimized for nanopore sensing environments. Traditional SELEX often fails to yield specific sequences which remain stable or exhibit clear signal transitions under the high ionic strengths and electric fields typical of nanopore operation. AI-driven methods overcome this limitation by integrating computational modeling, sequence–structure prediction, and data-driven screening tailored to nanopore conditions.

Sequence Optimization and Virtual Screening

Generative AI models (e.g., variational autoencoders and diffusion models) create novel aptamer sequences conditioned on both binding affinity and nanopore-compatible folding features (compactness, charge distribution).

Predictive scoring functions combine parameters such as Gibbs free energy, root mean square deviation (RMSD) in folding and predicted ionic blockade amplitude to rank different screened candidates before the experimental validation.

Machine learning classifiers trained on experimental nanopore current traces distinguish aptamers that produce strong, reproducible blockade patterns from those that yield noisy or transient signals.

3. Strategies of Aptamer-Nanopore Integration

Nanopore sensing relies primarily on measuring ionic current as molecules pass through or interact with a nanoscale pore (biological or solid-state). Aptamers (short, structured nucleic acids) can be integrated into nanopore systems to confer specificity for plethora of analytes: small molecules, proteins, peptides, etc.

Here are key modes of integration, with concrete illustrative examples.

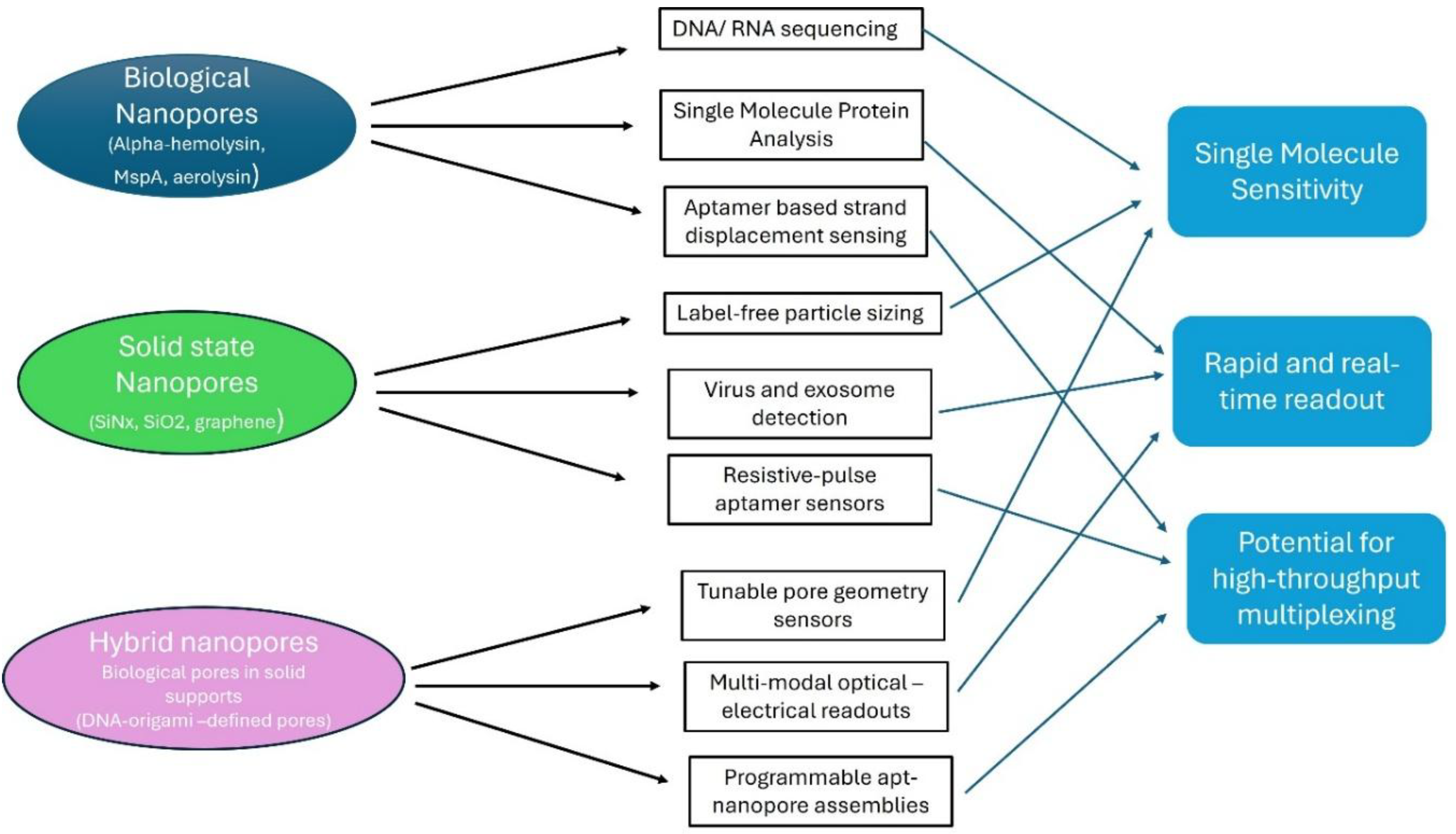

Types of Nanopores and How Aptamers Are Integrated

Biological Nanopores

α-hemolysin (α-HL) is a widely used biological nanopore. It forms a stable channel in a lipid bilayer, with a well-defined vestibule and constriction region. (Reynaud et al., 2020; Winters-Hilt, 2007)

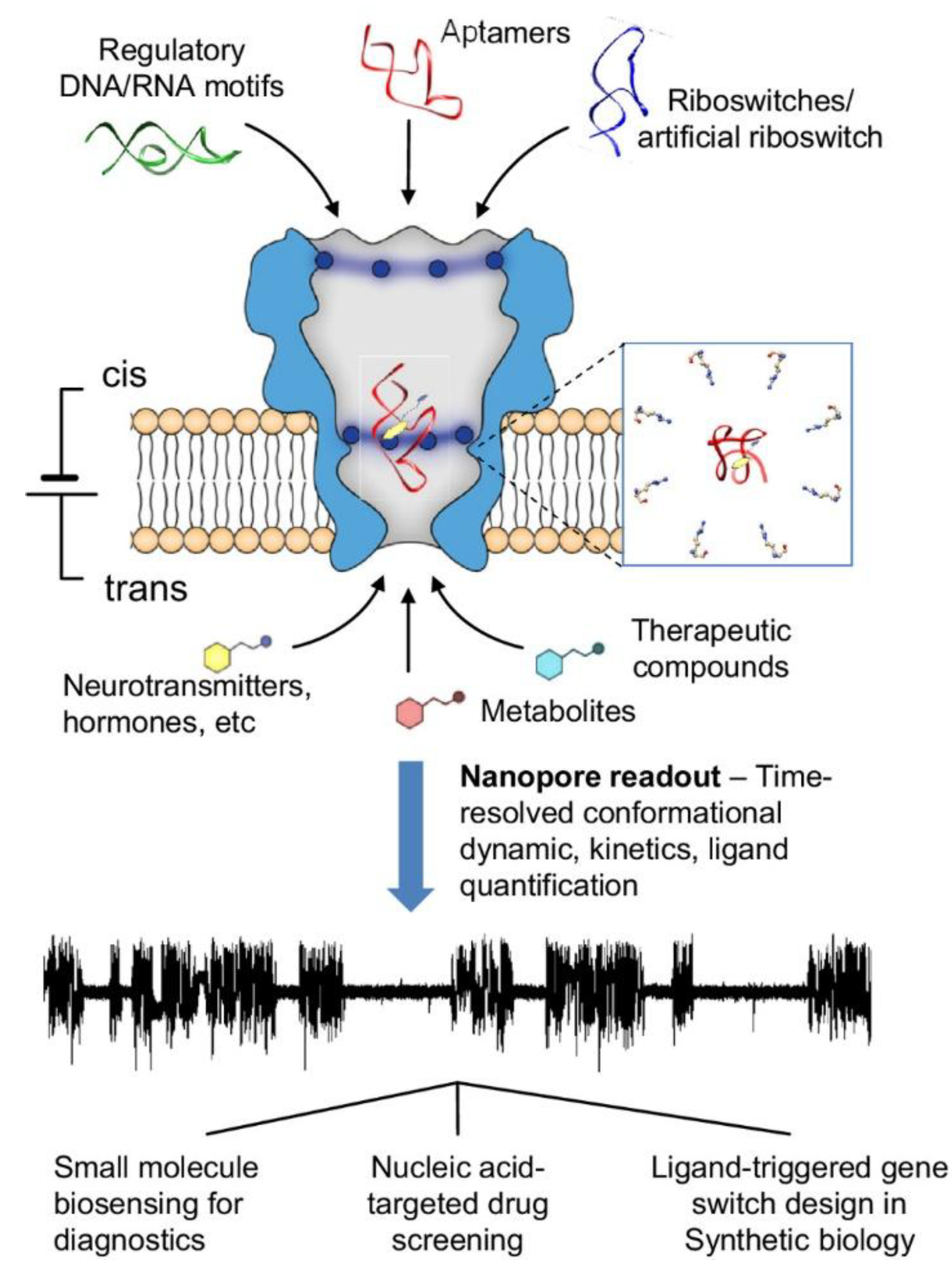

MspA nanopore (derived from Mycobacterium) has a narrow constriction and has been used for detecting aptamer conformational changes. (Chingarande et al., 2023) Aptamers are non-covalently docked into the MspA nanopore (which has a wide vestibule capable of hosting various nucleic acid structures) via a crucial R118 cationic ring which stabilizes the aptamer inside the pore. The cognate ligands interact from trans side , bind the aptamer inside the pore and change the ion current signatures , enabling the structural state discrimination. This sensing technology had been validated with three well-known aptamers (Dopamine DNA aptamer, Serotonin DNA aptamer and Theophylline RNA riboswitch aptamer) . Upon ligand binding, the aptamer adopts a single stable conformation causing reduced current fluctuations. This also showed compatibility with both DNA and RNA aptamers and platforms generalizable to riboswitches, engineered regulatory nucleic acid motifs etc. The advantages of this system include label-free detection, single molecule resolution and ability to study dynamic conformational pathways, not only binding endpoints. Currently, the limitations are the sensitivity , LOD is around 100nM for dopamine which is insufficient to detect physiological neurotransmitter levels (1-10 nM). In recent future, with the help of pore charge engineering, and aptamer sequence engineering, the sensitivity and efficiency of this sensor can be improved.

Integration Strategies:

Covalent anchoring of aptamer

In early work, a DNA aptamer (e.g., thrombin-binding aptamer) is hybridized to an oligonucleotide that is covalently attached to a cysteine engineered on the α-HL pore. (M. Cao et al., 2022a; Rotem et al., 2012)This study presents a new aptamer-based nanopore sensing strategy using the protein nanopore α-hemolysin (αHL). Unlike earlier methods where the sensing ligand is chemically fused to the pore, this work introduces a modular system, where an aptamer is attached indirectly via a DNA adapter tethered to the pore through a disulfide bond. This creates a “reporter” that resides near the pore entrance: the aptamer binding event modulates the ionic current, giving a specific blockade signature.

Host–guest / displacement strategies

In a study, researchers have developed a universal nanopore sensing strategy that integrates aptamer–probe hybridization with host–guest supramolecular chemistry inside the α-hemolysin (αHL) nanopore. The authors engineer a DNA probe modified with a ferrocene–cucurbit [

7]uril (Fc–CB[

7]) host–guest complex, which produces unique multilevel ionic current signatures when translocating the αHL pore. In the presence of a target analyte (protein or small molecule), the aptamer binds the analyte and releases the modified DNA probe, allowing its translocation and generating highly specific electrical signals. This serves as a quantitative readout, with event frequency correlating with analyte concentration.

The platform is demonstrated for VEGF121, thrombin, and cocaine, showing nanomolar sensitivity. Furthermore, the use of magnetic beads (MBs) significantly improves sensitivity by removing excess aptamer–probe duplexes, achieving picomolar detection limits. This universal platform is capable of single-molecule sensitivity and can be upgraded to high modularity, multi-target detection in one sample.

A thrombin-binding 15-mer G-quadruplex aptamer is hybridized to a short oligo linked to the pore opening. When thrombin binds the aptamer, it causes distinct ionic current changes detectable at the single-molecule level. This enables the real-time measurement of thrombin concentration and determination of its kinetic parameters (kon, koff) and dissociation constant (Kd), in agreement with the current established methods.

The study further showed how linker length and aptamer positioning influence pore entry, signal characteristics, and detection efficiency. The platform also allows convenient switching of aptamer sequences and suggests a path toward parallel nanopore sensor arrays for multiple analytes.

Using magnetic beads also improves sensitivity by concentrating the released probes, lowering the detection limit by orders of magnitude. Magnetic beads can also help with pre-concentrating of analytes. These beads (MBs) can collect target-binding events from larger sample volumes and complex matrices (serum, plasma etc.). Removing excess aptamer-probe duplexes can eliminate signal interference. Isolating only released probe-DNA generates clean nanopore events. Different aptamers can be immobilized on different bead batches , enabling them for multiple target-sensing. MBs carry tagged reporter DNA , which is released after enzymatic cleavage, binding-induced conformational change and competitive displacement. Various applications of MBs include CRISPR nanopore assays (Cas12 cleavage releases DNA from beads), enzyme activity assays and DNA methylation detection etc.

How Aptamers Integrated into Solid-State Nanopores

Solid-state nanopores (e.g., silicon nitride, glass) provide mechanical robustness, tunable geometry, and chemical functionalizability. Aptamers can be grafted onto their inner surface to design a precise, selective binding region for their targets.

Some Examples of Solid State-Nanopores Are as Follows:

A quartz nanopore was first coated with a gold film, enabling functionalization through Au–thiol chemistry. A thiolated CEA aptamer was immobilized on the inner wall of the nanopore, creating a confined environment where CEA molecules could interact with the aptamer during electrophoretic translocation.

Two distinct types of current signatures were observed:

Type I: Fast, shallow blockade events from CEA moving through a bare gold nanopore (no aptamer interaction).

Type II: Deep, long-duration blockades in the aptamer-modified nanopore, indicating binding and dissociation interactions.

By statistically analyzing these single-molecule events, the study extracted association (kon), dissociation (k off), and dissociation constant (Kd) values at the single-molecule level.

The system showed high selectivity, distinguishing CEA from non-target proteins (IgG, BSA, HRP), and successfully detected CEA in human serum samples, with results comparable to ELISA. (Yin et al., 2023)

The researchers have reported direct protein sensing strategy using biological nanopores. Sensing protein is relatively difficult compared to DNA due to big -size and structural and charge complexity. However, the authors designed a modified aptamer which can bind SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (NP) and extend it with a long DNA tail. This engineered protein–DNA complex interacts with an α-hemolysin (α-HL) nanopore to produce a distinctive two-level current blockade pattern, which serves as the sensing signature. (Yin et al., 2023). They achieved a detection limit down to ~10 pM for NP and tested the concept in conditions relevant for diagnostics.

In another study, scientists have tried to integrate amino-acid specific DNA aptamers into interface nanopores (solid-state) to detect peptides with specific residues. They have developed a force-controlled interface nanopore (iNP) system that integrates DNA aptamers to enable amino acid-specific detection of peptides. The iNP system uses a micro channeled atomic force microscope cantilever to form a nanopore at the interface with a soft PDMS substrate. This allows for dynamic tuning of the pore size which leverages unique flexibility and wide applications.

For instance, a phenylalanine aptamer was used whereas the aptamer is built into the nanopore interface; its binding to phenylalanine moieties in peptides slows down translocation of those peptides. (Schlotter et al., 2024) By tuning the applied voltage (i.e., reducing voltage), they have succeeded to prolong the aptamer–target interaction time, giving discrete ionic current levels with repeated motifs. Importantly, the system showed high selectivity: peptides containing phenylalanine generate different current signatures than peptides containing structurally similar residues (tyrosine, tryptophan). They also decoupled specific binding (aptamer–target) from nonspecific interactions (electrostatic / hydrophobic) using optical waveguide light-mode spectroscopy. This represents a step toward single-molecule proteomics, since it allows recognition of specific amino acids within peptides.

Figure 1.

Different types of Nanopores and their versatile applications.

Figure 1.

Different types of Nanopores and their versatile applications.

Mechanistic Insights: Why Aptamer and Nanopore Works Well

Aptamers (Magic bullets) fold into highly specific 3D conformations or structures that bind to their cognate targets (small molecules, proteins, cells etc.) and nanopores detect changes in ionic currents as single molecules translocate or dock through it. Together aptamers act as “molecular locks” and nanopores act as “electrical readers”. The aptamer-nanopore pairing transforms binding events into quantifiable , detectable electrical signals.

Figure 2.

Fundamental concepts and uses of a nanopore platform designed to detect nucleic acid structural shifts upon interaction with small molecules. (Reprinted and adapted with permission from (Chingarande et al., 2023).

Figure 2.

Fundamental concepts and uses of a nanopore platform designed to detect nucleic acid structural shifts upon interaction with small molecules. (Reprinted and adapted with permission from (Chingarande et al., 2023).

Conformational readout: Aptamers often change shape (folding, unfolding) upon binding. When docked or captured in a nanopore, these conformational changes modulate ion current in characteristic ways, which can be resolved at single-molecule timescales. In a study by Rugare et al., they have developed a real-time label free detection platform, which uses the MspA protein nanopore to noncovalently dock nucleic acid aptamers and monitor their conformational transitions in real-time upon binding to small molecules like dopamine, serotonin, and theophylline. (Chingarande et al., 2023)

Kinetic measurements: In the same study, with the help of analyzing the characteristic nanopore current signatures, the platform can quantify ligand binding kinetics, identify key aptamer motifs involved in ligand binding, and demonstrate the selectivity of aptamers for their target ligands.(Chingarande et al., 2023) Due to this fact, each binding or un-binding event can be read out as a separate current trace, one can compute association and dissociation rate constants from dwell times.

In another study, DNA oligonucleotide is covalently attached to the αHL nanopore, acting as an adapter to which various aptamers can be coupled by hybridization. When the thrombin-binding aptamer is hybridized to the adapter, two current blockade levels (B1 and B2) are observed, corresponding to the insertion of the aptamer’s quadruplex domain and the double-stranded DNA segment, respectively. The binding of thrombin to the aptamer results in a new current level (UB+T), allowing the detection and quantification of nanomolar concentrations of thrombin. The approach provides association/dissociation rate constants and equilibrium dissociation constants for the thrombin-aptamer interaction. The rate constants for the aptamer·thrombin interactions were determined by observing the transitions between the UB and UB+T current levels at different thrombin concentrations. The association rate constant Kon and dissociation rate constant Koff were used to determine the equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) of 77 ± 6 nM for aptamerT4 and 126 ± 34 nM for aptamerT1, which are similar to values determined by other techniques like surface plasmon resonance and capillary electrophoresis. (Rotem et al., 2012)

Interface control: In solid-state pores, the aptamer can be tethered to the wall, so only in the target-bound state, current blockade signature changes significantly, improving specificity. (M. Cao et al., 2022b) When this CEA specific aptamer functionalized glass nanopore system was tested in human serum samples, nanopore-based quantification matched ELISA results, indicating strong translational potential.

Nanopipette and interface functionalization with aptamers for localized sensing: Aptamer-functionalized nanopipettes have recently emerged as powerful tools for localized, single-cell and subcellular sensing. By decorating the nanopipette tip with aptamers, the interface gains high molecular specificity, enabling selective recognition directly at the site of interest. The confined geometry of the nanopipette allows precise spatial control, while surface functionalization stabilizes the sensing interface and enhances signal-to-noise. (Denuga et al., 2024). In another approach, the dynamic behavior of aptamer structures upon dopamine binding leads to the rearrangement of surface charge within the nanopore, resulting in measurable changes in ionic current. To assess sensor performance in real time, researchers have designed a fluidic platform to characterize the temporal dynamics of nanopipette sensors. Together, these advances make real-time, minimally invasive biochemical detection possible at unprecedented spatial resolution. (Schlotter et al., 2024; Stuber et al., 2024)

Carrier-based scaffolds (DNA origami, λ-DNA) decorated with multiple aptamers to boost detection yield.

Carrier-based scaffolds such as DNA origami and λ-DNA enhance nanosensor performance by presenting multiple spatially organized aptamers, which increases effective affinity through multivalent (avidity-based) binding, boosts target capture rates, and prolongs binding lifetimes at nanopores or nanoelectrodes. Precise nanoscale positioning on DNA origami improves cooperative interactions, while long λ-DNA provides high-density decoration for enhanced encounter probability. This multivalency significantly improves signal strength, detection yield, and single-molecule capture efficiency in modern nano sensing platforms. (Cervantes-Salguero et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020)

Recent Advancements of Aptamer based Nanopore Sensing

Recent applications of aptamer nanopore sensing have expanded significantly, moving beyond simple proof-of-concept studies into complex real-world diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety. This technology combines the high specificity of aptamers (single-stranded DNA/RNA “chemical antibodies”) with the single-molecule sensitivity of nanopores (nanoscale holes that measure changes in ionic current).

1. Medical Diagnostics & Biomarker Detection

The most active area of research is in the rapid, label-free detection of disease biomarkers. Recent work has focused on detecting low-abundance biomarkers in complex biological fluids like blood or serum without extensive purification.

Cancer Biomarkers:

Recent sensors have been developed for lung cancer biomarkers (e.g., specific proteins or circulating tumor DNA). The aptamer acts as a gatekeeper; when it binds to the cancer marker, the complex is too large to pass through the pore or changes the “dwell time” (the time it takes to pass), creating a unique electrical signature. Nanopore sensors functionalized with anti-PSA aptamers have achieved detection limits in the picomolar range, far more sensitive than traditional ELISA tests.

Recently researchers have developed specific DNA aptamer based nanopore system to detect actinomycin-D, a potent anti-cancer drug. This sensor achieves high sensitivity, with a detection limit (LOD) of 1.20 nM and sensitive in complex human serum samples. (Zhao et al., 2025)

In recent review articles, plethora of applications including cancer, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases have been discussed using aptamer-nanopore technology. This technology also facilitates early detection, multiplex analysis and translational diagnostics. (Shrikrishna & Gandhi, 2025)

Infectious Diseases (Pathogens):

During the SARS-COV2 pandemic, aptamer-nanopore systems were adapted to detect the spike protein of the virus. These sensors can distinguish between the original strain and variants (like Omicron) based on subtle differences in the binding signal.(Chen et al., 2020; Peinetti et al., 2021)

Bacterial Pathogens: Systems have been designed to detect whole bacteria (like E. coli or Salmonella) or their specific toxins.

In a recent study, scientists have designed an aptamer self-assembly sensing strategy based on hydrophobic nanopores to identify the bacterial types in mixed samples. The proposed sensor exhibits a broad dynamic detection range for Escherichia coli and S. aureus. This electrochemical sensor showed high recognition sensitivity for low-concentration bacteria. (Dong et al., 2025)

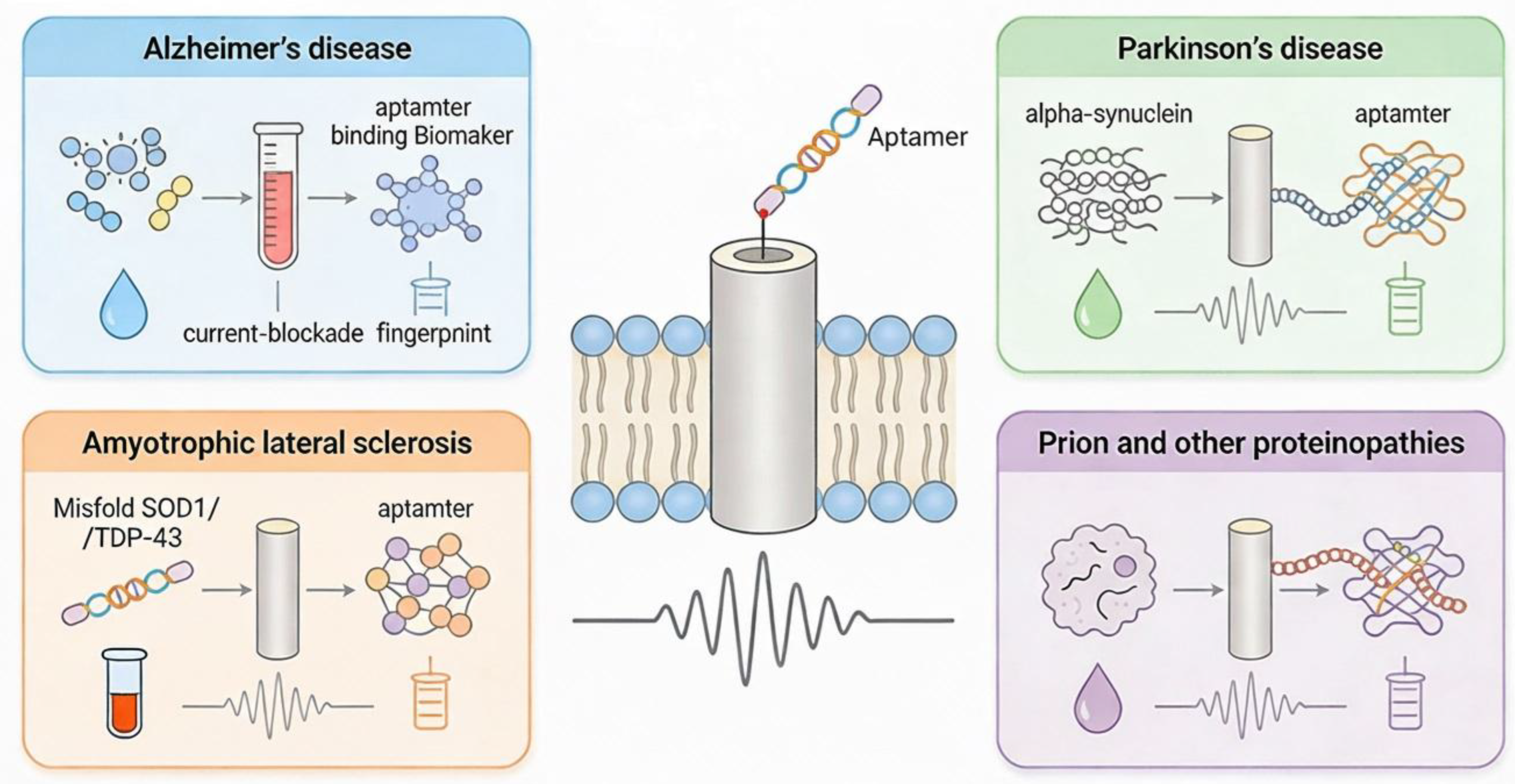

Neurodegenerative Diseases:

The current revival of aptamer technologies, combined with rapid progress in neuroscience, offers a powerful opportunity to deepen our understanding of core brain functions and dysfunctions. Structure-switching aptamers—defined by their high selectivity and target-induced conformational changes—are increasingly recognized as excellent recognition units for chemical biosensors. Yet, it remains crucial to evaluate each aptamer sequence under conditions that closely mimic the intended biological environment to ensure reliable and reproducible performance.(Stuber & Nakatsuka, 2024) To detect dopamine, serotonin like neurotransmitters, structure-switching aptamers are promising candidates for highly selective, label-free detection in complex biological environments. (Stuber & Nakatsuka, 2024) . The authors showcased aptamer-integrated FETs and nanopipettes that overcome Debye length limitations and achieve real-time, ultrasensitive, localized detection of dopamine and serotonin. Aptamer coated FETs and nanopipettes showed high sensitivity and specificity in serum, CSF and undiluted biological media. Aptamers confined inside nanopipettes allow sub-cellular and synaptic-scale chemical detection with minimal tissue damage.

Aptamer-functionalized nanopore sensors combine the single-molecule sensitivity and label-free detection of nanopores with the high specificity and tunability of aptamers to detect disease-relevant protein biomarkers (e.g. misfolded or aggregated proteins) involved in neurodegeneration. This approach has already enabled detection of pathological aggregates such as oligomeric α-Synuclein in patient cerebrospinal fluid with minimal sample processing. Aptamers can also discriminate between different fibrillar “polymorphs” of the same protein — for example different structural forms of α-Syn — potentially enabling differential diagnosis between related disorders. Due to the ability of nanopores to record individual binding or translocation events, this technology could support early diagnosis, real-time monitoring, and structural characterization of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. (Shrikrishna & Gandhi, 2025; Stuber et al., 2024)

Nanopore can also detect the difference between a single monomer (healthy) and an oligomer (toxic clump) based on the size of the current blockade.

Figure 3.

Aptamer-Nanopore Sensing in various Neuro-degenerative diseases.

Figure 3.

Aptamer-Nanopore Sensing in various Neuro-degenerative diseases.

Environmental Monitoring

Recent applications of aptamer-nanopore sensing have moved “out of the lab” to address field monitoring of pollutants, often focusing on heavy metals and small molecules that are difficult to detect with traditional methods like antibody-based systems. As-of-now, heavy-metal detection with aptamers (so-called “aptasensors”) has relied on optical or electrochemical readouts, the concept of combining aptamers with nanopores has started to gain attention to achieve single-ion sensitivity and “ultra-low” detection limits.

A recent report described a solid-state nanopore sensor functionalized with metal-ion-specific aptamers, demonstrating the detection of ions such as Hg²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Ag⁺ with high sensitivity — offering a compact, potentially portable platform for water-quality monitoring. (Xia et al., 2024)

Specialized aptamers (like T-rich sequences for mercury) undergo a conformational change (e.g., forming a hairpin) when they bind the metal ion like Mercury (Hg²⁺) and Lead (Pb²⁺) . This shape change alters the current flow through the nanopore, allowing for rapid quantification of water contamination. The integration of aptamers helps to overcome major challenges associated with heavy-metal sensing (small size, single binding site) by providing high specificity and selective binding, even in complex matrices like biological or environmental samples.(Singhal et al., 2025) In a study , scientists studied the intrinsic mechanism of structure and charge-density distribution of aptamer based resistive pulse-sensors (RPS). They have opted for two metal binding DNA aptamers (mercury and led) to create a sensor which is efficient in a wide range of electrolytes , akin to river to sea water conditions. (Mayne et al., 2018)

There are various applications of nanopore sensing to detect pharmaceutical contaminants in the environment like industrial waste, sewage water and wastewater systems. Sensors are now being used to detect antibiotics (e.g., tetracycline, kanamycin) in wastewater. This is crucial for tracking antimicrobial resistance in the environment.

Food Safety & Agriculture

In the food industry, the focus is on speed—detecting contamination before products reach the shelf of the markets. So, importance of rapid, on-site detection of contaminants, pesticides is immense.

Mycotoxins like Ochratoxin A (OTA) and Aflatoxin B1 are toxic compounds produced by mold on grains and coffee. Recent nanopore sensors use a “competitive binding” assay: the toxin in the food sample competes with a DNA probe to bind the aptamer, changing the frequency of blockage events in the nanopore.

Recent studies have demonstrated the detection of organophosphorus pesticides (like acetamiprid) at trace amounts in sub-nanomolar. Researchers have introduced a dual signal nanopore biosensor that simultaneously measures ionic current and fluorescence to detect acetamiprid (ACE) residues with high sensitivity and specificity. By using a FAM-labeled aptamer–cDNA duplex grafted onto conical nanopores, ACE binding triggers structural changes that convert the sensor from a “closed/on” to an “open/off” state, enabling robust detection down to almost 0.12 ng/mL. The platform performs reliably in complex matrices from medicine–food homology products and shows excellent selectivity, stability, and agreement with conventional LC-MS technique. The aptamer binding prevents the pesticide from inhibiting downstream reactions or simply blocks the pore in a characteristic way. (Y. Li et al., 2025) The dual-mode nanopore design provides a simple, accurate, and highly sensitive approach for pesticide residue analysis, with strong potential for broader aptamer-based sensing applications.

Allergen Detection: New applications of sensors include detecting various food-allergens like peanut (Ara h 1) or wheat (gluten) proteins in processed foods to ensure safety for allergic consumers. (Aquino & Conte-Junior, 2020) Aptamer–nanopore systems offer a powerful platform for detecting such kind of food allergens like gluten peptides, and other protein-based allergens. Aptamers provide high molecular recognition specificity, enabling them to selectively bind allergenic proteins even within complex food matrices. (Jiang et al., 2021) When an allergen binds to its aptamer tethered inside or at the entrance of a nanopore, it induces structural or charge changes that modulate ionic current, producing a clear electrical signature for detection. This nanoscale confinement enhances sensitivity because binding events significantly alter ion flow, allowing label-free, real-time quantification at very low concentrations. Nanopores can also be engineered with multiple aptamers to detect several allergens simultaneously. Overall, aptamer–nanopore sensors offer fast, portable, and highly sensitive allergen monitoring, improving food safety and supporting rapid on-site testing.(Sett, 2012)

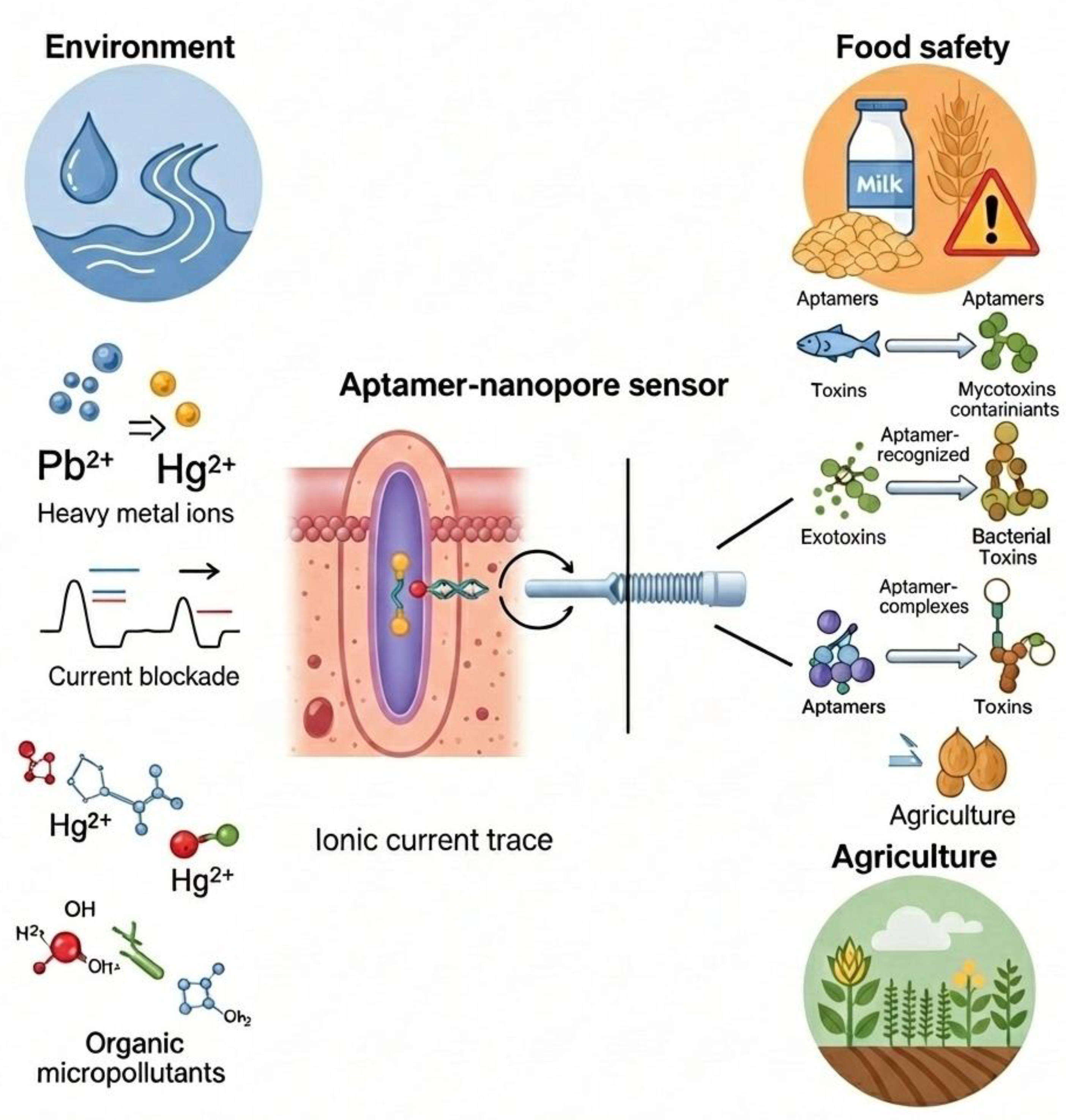

Figure 4.

Aptamer-nanopore sensing applications in Environment field (heavy metal detection, micropollutant detection), food safety applications (toxin, food contaminant) and agriculture industry (pesticide, etc).

Figure 4.

Aptamer-nanopore sensing applications in Environment field (heavy metal detection, micropollutant detection), food safety applications (toxin, food contaminant) and agriculture industry (pesticide, etc).

Machine Learning Integration in Aptamer-Nanopore Sensing Signal Readouts and Analytical Capabilities

Machine learning (ML) significantly enhances the analytical performance of aptamer–nanopore sensors by improving how ionic current signals are interpreted and enabling more accurate, automated detection.ML enables aptamer–nanopore sensors to convert complex ionic current traces into quantitative, real-time readouts of target binding and kinetics with improved sensitivity and specificity. By learning characteristic current blockade patterns associated with aptamer conformations or aptamer–target complexes, ML classifiers (e.g., SVMs, HMMs, CNNs, and deep networks) can automatically detect and label translocation or docking events, even when they are highly noisy or short-lived. Firstly, ML algorithms can denoise and deconvolute complex current traces, making it easier to distinguish true binding events from background fluctuations in real time. (Wen et al., 2021) Secondly, pattern-recognition models—such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs)—can classify subtle current blockade signatures to identify specific allergens or distinguish between closely related targets. Thirdly, ML enables quantitative prediction of analyte concentration by learning correlations between signal features (duration, amplitude, dwell time, frequency) and analyte levels. Advanced approaches such as multivoltage “voltage-matrix” profiling combined with ML further expand analytical capabilities by exploiting voltage-dependent current signatures to differentiate targets or binding states in complex mixtures, including aptamer–biomarker complexes. Finally, ML supports multiplexed sensing by differentiating multiple aptamer–target interactions within the same nanopore, enhancing throughput and reducing false positives.

The specific features that can capture aptamer conformational changes are those that describe discrete current levels and their dynamics, rather than only single-event amplitude or duration. Key engineered features include the mean residual current at each blockade substate (multiple levels), their variance, and transition probabilities between these levels, which reflect distinct conformations and switching pathways. Dwell-time distributions for each substate, including multi-exponential components and state lifetimes, are especially informative for kinetic differences between unbound, partially bound, and fully bound aptamer conformations. Additional useful features are event-level statistics such as blockade depth, rise/fall times, and inter-event intervals, which encode changes in aptamer shape geometry, charge distribution, and flexibility. For nanopipette and wall-grafted aptamers, effective surface charge density, rectification ratio, and conductance–voltage curves provide indirect but highly sensitive descriptors of aptamer expansion–contraction and layer permeability changes.(C. Cao et al., 2023; Chingarande et al., 2023) In deep-learning pipelines, raw or minimally processed current time series, optionally segmented into windows around conformational transitions, allow convolutional and recurrent networks to learn higher-order temporal patterns that correlate with hidden structural rearrangements.(C. Cao et al., 2023) Combining these level-resolved electrical features with biophysical information (e.g., MD- or FEM-informed charge-density changes) yields the most discriminative feature sets for machine-learning models that classify aptamer conformational states in nanopore sensors. Overall, integrating ML into aptamer–nanopore systems transforms raw ionic signals into accurate, automated, and high-resolution biochemical information, making these sensors more robust for real-world biosensing applications.

Challenges and Bottlenecks

Aptamer-nanopore sensing technology offers several promises like single molecule sensitivity, specificity, multiplex analysis, etc. , nonetheless, several inherent shortcomings continue to constrain this technology.

Limited Specificity and Interference in Complex Samples

Aptamer–nanopore platforms often struggle with distinguishing closely related analytes and suppressing background events, especially in serum or other complex matrices where non-specific adsorption and co-translocating species interfere current signatures. Weak or suboptimal aptamer affinity and off target binding further reduce selectivity and can produce overlapping blockade patterns. These issues complicate quantitative analysis at low concentrations and hinder reliable multiplexing. Strategies such as carrier constructs (aptamer-modified DNA or nanoparticles) improve specificity but add extra complexity and may introduce new artefacts. (Xia et al., 2024)

Pore Stability, Biofouling, and Device Robustness

Biological nanopores depend on fragile lipid bilayers, which suffer from limited lifetime, instability under varying voltages or ionic strengths, and challenges in controlled insertion and long-term operation. Solid-state nanopores provide better mechanical robustness but face severe problems with non-specific adsorption, pore clogging, and drift in effective pore geometry and surface charge over time. Biofouling caused by proteins and other biomolecules can alter baseline currents and alter aptamer accessibility, degrading sensitivity and reproducibility. (Stuber et al., 2024) These material constraints remain a major bottleneck for translating aptamer–nanopore devices into routine or point-of-care measurements.(Lv et al., 2022; Mayer et al., 2022)

Signal-to-Noise, Temporal Resolution, and Data Analysis Load

Single-molecule events can be extremely fast and of small amplitude, requiring high-bandwidth, low-noise electronics and careful filtering to resolve aptamer conformational transitions and binding states. Thermal noise, flicker noise (1/f), and instrumental artefacts can mask subtle conformational signatures, while aggressive filtering risks distorting dwell times and amplitudes. Extracting kinetic and structural information demands sophisticated event detection, feature extraction, and often machine-learning pipelines, which are computationally intensive and sensitive to parameter choices and training data bias. This bottleneck complicates standardization across various laboratories and hinders adaptation of the technology outside specialist groups. (Sze et al., 2017)

Aptamer Selection, Structural Constraints, and Generalizability

SELEX-derived nucleotide aptamers may not possess the optimal folding pathways, mechanical properties, or electrostatic profiles needed to generate robust, distinguishable nanopore signals upon target binding. (Dong et al., 2025; Mayne et al., 2018)Strong secondary structures (e.g., stable G-quadruplexes) can resist nanopore pulling or produce complex, heterogeneous blockade patterns that are difficult to interpret quantitatively. Additionally, aptamer performance often degrades in biological complex matrix conditions due to nuclease degradation (especially RNA aptamers), ionic-strength changes, and competition from endogenous ligands. These factors limit the transferability of a given aptamer–nanopore assay across targets, sample types, and operating conditions, making platform-wide standardization challenging. In solid-state nanopores, surface chemistry of modified aptamers can lead to nonspecific adsorption, which can clutter the signal unless carefully specified. (Reynaud et al., 2020)

Future Directions and Conclusions

Future development of aptamer–nanopore sensing for biological applications is moving toward clinically relevant precision diagnostics and real-time biomarker monitoring at ultra-low concentrations. Advances of various nanopore materials, aptamer engineering, and AI-assisted analysis are expected to make these platforms more robust, selective, and deployable in realistic biological environments. (Lv et al., 2022) Even, in situ aptamer evolution guided by nanopore signatures offer great promises.

One major direction is point-of-care and personalized diagnostics, where aptamer-functionalized nanopores are integrated into portable or wearable devices for rapid detection of disease biomarkers, pathogens, and drugs directly from blood, saliva, or urine. Combining multiplexed aptamer panels with high throughput nanopore arrays could enable simultaneous profiling of multiple proteins, nucleic acids, and metabolites for early disease detection and disease monitoring.

Another key trajectory is in neurobiology and cell biology, using nanopore or nanopipette platforms with aptamer probes to measure neurotransmitters and signaling molecules in or near single cells. Intracellular and synaptic-level measurements of molecules like dopamine, serotonin, or peptides are expected to support mechanistic studies of neurological disorders and drug responses.(Stuber & Nakatsuka, 2024)

Further, future direction of aptamer–nanopore systems as tools to study biomolecular structure and conformational dynamics, rather than only concentration of biomolecules. By resolving subtle conformational changes of proteins, peptides, or nucleic acids at the single-molecule level, these sensors could be applied to epigenetics, protein misfolding diseases, and drug–target interaction mapping in pharmaceutical research.

Nanopore biosensing to bridge fundamental research and real-world diagnostics, paving the way for rapid, sensitive, and accessible health monitoring tools in precision medicine. Integration with microfluidics, advanced nanofabrication, and machine learning is expected to yield automated lab-on-chip platforms that perform sample preparation, sensing, and data interpretation in a unified workflow. Such systems aim to overcome current bottlenecks of stability, bio-fouling, and data overload, enabling scalable, high-throughput aptamer–nanopore assays for routine biological and clinical specimens.

References

- Aquino, A.; Conte-Junior, C. A. A Systematic Review of Food Allergy: Nanobiosensor and Food Allergen Detection. Biosensors 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.; Magalhães, P.; Krapp, L. F.; Bada Juarez, J. F.; Mayer, S. F.; Rukes, V.; Chiki, A.; Lashuel, H. A.; Dal Peraro, M. Deep learning-assisted single-molecule detection of protein post-translational modifications with a biological nanopore. ACS Nano 2023, 18, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, L.; Tang, H.; Qiu, X.; Li, Y. Single-Molecule Investigation of the Protein-Aptamer Interactions and Sensing Application Inside the Single Glass Nanopore. Analytical Chemistry 2022, 94, 17405–17412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, L.; Tang, H.; Qiu, X.; Li, Y. Single-Molecule Investigation of the Protein-Aptamer Interactions and Sensing Application Inside the Single Glass Nanopore. Analytical Chemistry 2022, 94, 17405–17412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Salguero, K.; Freeley, M.; Chávez, J. L.; Palma, M. Single-molecule DNA origami aptasensors for real-time biomarker detection. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2020, 8, 6352–6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Ni, X.; Dai, J. A DNA Aptamer Based Method for Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein. In Virologica Sinica; Science Press, 2020; Vol. 35, Issue 3, pp. 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chingarande, R. G.; Tian, K.; Kuang, Y.; Sarangee, A.; Hou, C.; Ma, E.; Ren, J.; Hawkins, S.; Kim, J.; Adelstein, R.; Chen, S.; Gillis, K. D.; Gu, L. Q. Real-Time label-free detection of dynamic aptamer small molecule interactions using a nanopore nucleic acid conformational sensor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denuga, S.; Duleba, D.; Dutta, P.; Macori, G.; Corrigan, D. K.; Fanning, S.; Johnson, R. P. Aptamer-functionalized nanopipettes: a promising approach for viral fragment detection via ion current rectification. Sensors and Diagnostics 2024, 3, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Lu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Su, M.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, H.; Shen, S.; Ma, Q.; Gao, Z. Aptamer-anchored hydrophobic nanopores for electrochemical/fluorescent dual-mode identification of pathogenic bacteria. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, D. M.; Larsen, N.; Jensen, J. K.; Andreasen, P. A.; Kjems, J. Characterisation of aptamer-target interactions by branched selection and high-throughput sequencing of SELEX pools. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Sun, Y.; Jia, W.; Yu, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Luan, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, F. Advancements in SELEX Technology for Aptamers and Emerging Applications in Therapeutics and Drug Delivery. In Biomolecules; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), 2025; Vol. 15, Issue 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Z.; Weng, X. Microfluidic origami nano-aptasensor for peanut allergen Ara h1 detection. Food Chemistry 2021, 365, 130511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, A. D.; Pai, S.; Ellington, A. Aptamers as therapeutics. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 2010, 9, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Xie, J.; Wu, H. C. A universal strategy for aptamer-based nanopore sensing through host-guest interactions inside α-hemolysin. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2015, 54, 7568–7571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tu, J.; Wang, H.; Luo, K.; Xiao, P.; Liao, T.; Zhang, G. J.; Sun, Z. Dual signal output detection of acetamiprid residues in medicine and food homology products via nanopore biosensor. Food Chemistry 2025, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, S.; Tan, C. S.; Ming, D. Recent Advances in Aptamer-Based Nanopore Sensing at Single-Molecule Resolution. In Chemistry - An Asian Journal; John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2022; Vol. 17, Issue 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S. F.; Cao, C.; Dal Peraro, M. Biological nanopores for single-molecule sensing. IScience 2022, 25, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayne, L.; Lin, C.-Y.; Christie, S. D. R.; Siwy, Z. S.; Platt, M. The Design and Characterization of Multifunctional Aptamer Nanopore Sensors. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 4844–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peinetti, A. S.; Lake, R. J.; Cong, W.; Cooper, L.; Wu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Pawel, G. T.; Eugenia Toimil-Molares, M.; Trautmann, C.; Rong, L.; Mariñas, B.; Azzaroni, O.; Lu, Y. Direct detection of human adenovirus or SARS-CoV-2 with ability to inform infectivity using DNA aptamer-nanopore sensors. Sci. Adv 2021, Vol. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quint, I.; Simantzik, J.; Kaiser, L.; Laufer, S.; Csuk, R.; Smith, D.; Kohl, M.; Deigner, H. P. Ready-to-use nanopore platform for label-free small molecule quantification: Ethanolamine as first example. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine 2024, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaud, L.; Bouchet-Spinelli, A.; Raillon, C.; Buhot, A. Sensing with nanopores and aptamers: A way forward. In Sensors (Switzerland); MDPI AG, 2020; Vol. 20, Issue 16, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotem, D.; Jayasinghe, L.; Salichou, M.; Bayley, H. Protein Detection by Nanopores Equipped with Aptamers 2012. [CrossRef]

- Schlotter, T.; Kloter, T.; Hengsteler, J.; Yang, K.; Zhan, L.; Ragavan, S.; Hu, H.; Zhang, X.; Duru, J.; Vörös, J.; Zambelli, T.; Nakatsuka, N. Aptamer-Functionalized Interface Nanopores Enable Amino Acid-Specific Peptide Detection. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 6286–6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sett, A. Aptasensors in Health, Environment and Food Safety Monitoring. Open Journal of Applied Biosensor 2012, 01, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sett, A.; Borthakur, B. B.; Sharma, J. D.; Kataki, A. C.; Bora, U. DNA aptamer probes for detection of estrogen receptor α positive carcinomas. Translational Research 2017, 183, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrikrishna, N. S.; Gandhi, S. Nanopore-based sensing for biomarker detection: from fundamental principles to translational diagnostics. In Journal of Nanobiotechnology; BioMed Central Ltd, 2025; Vol. 23, Issue 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A. J.; d’Oelsnitz, S.; Ellington, A. D. Synthetic evolution. In Nature Biotechnology; Nature Research, 2019; Vol. 37, Issue 7, pp. 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Morya, V.; Rajwar, A.; Chandrasekaran, A. R.; Datta, B.; Ghoroi, C.; Bhatia, D. DNA-Functionalized Nanoparticles for Targeted Biosensing and Biological Applications. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 30767–30774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuber, A.; Cavaccini, A.; Manole, A.; Burdina, A.; Massoud, Y.; Patriarchi, T.; Karayannis, T.; Nakatsuka, N. Interfacing Aptamer-Modified Nanopipettes with Neuronal Media and Ex Vivo Brain Tissue. ACS Measurement Science Au 2024, 4, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuber, A.; Nakatsuka, N. Aptamer Renaissance for Neurochemical Biosensing. In ACS Nano; American Chemical Society, 2024; Vol. 18, Issue 4, pp. 2552–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, J. Y. Y.; Ivanov, A. P.; Cass, A. E. G.; Edel, J. B. Single molecule multiplexed nanopore protein screening in human serum using aptamer modified DNA carriers. Nature Communications 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, C.; Dematties, D.; Zhang, S. L. A Guide to Signal Processing Algorithms for Nanopore Sensors. In ACS Sensors; American Chemical Society, 2021; Vol. 6, Issue 10, pp. 3536–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters-Hilt, S. The α-Hemolysin nanopore transduction detector - Single-molecule binding studies and immunological screening of antibodies and aptamers. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8 (SUPPL. 7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.; Zolfigol, N.; Nahass, P.; Li, B.; Lei, Y. Aptamer-Enabled Solid-State Nanopore Sensors for Metal Ions Detection. 2024 AIChE Annual Meeting, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, B.; Tang, P.; Wang, L.; Xie, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Weng, T.; Tian, R.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D. An aptamer-assisted nanopore strategy with a salt gradient for direct protein sensing. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2023, 11, 11064–11072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Munusamy, S.; Chen, J.; Kong, J.; Jahani, R.; Kanaherarachchi, A.; Zhou, S.; Guan, X. A Label-Free Nanopore Biosensor for Rapid and Highly Sensitive Detection of Actinomycin in Human Serum. ACS Measurement Science Au 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).