Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Deep Learning Approaches and Limitations

1.3. Classical Geometry-Based Methods

1.4. Objective and Contribution

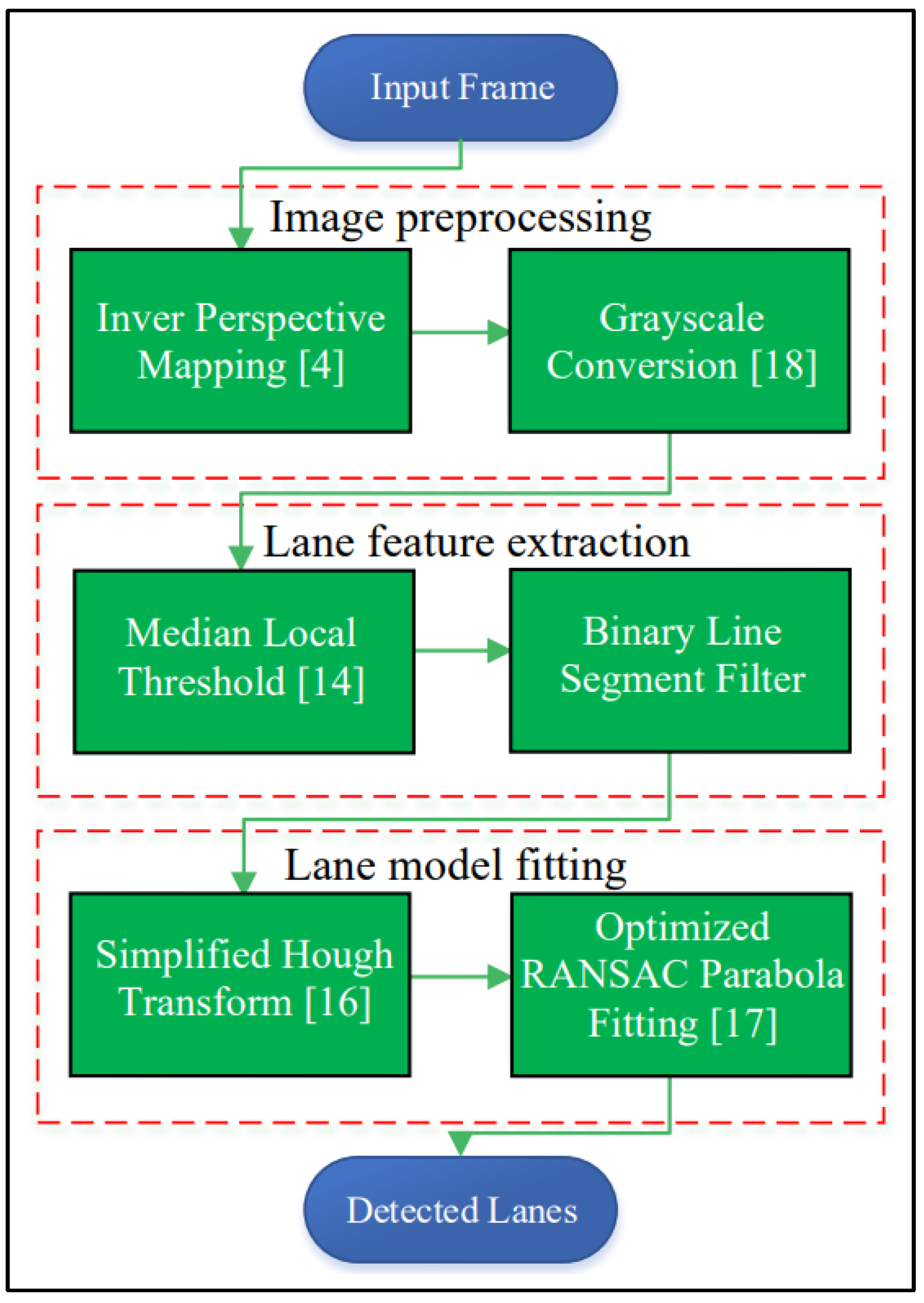

2. Proposed Lane Detection Pipeline

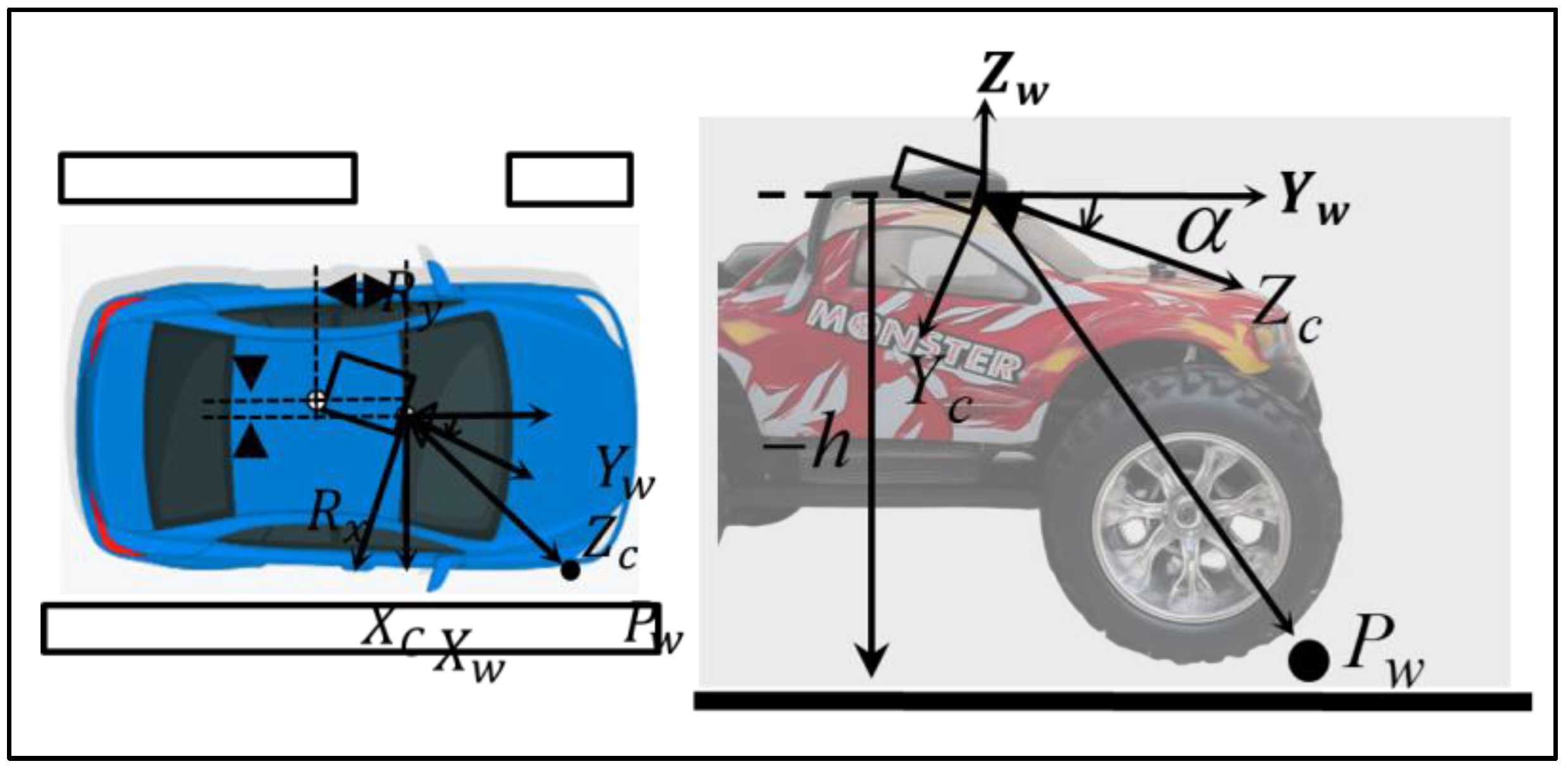

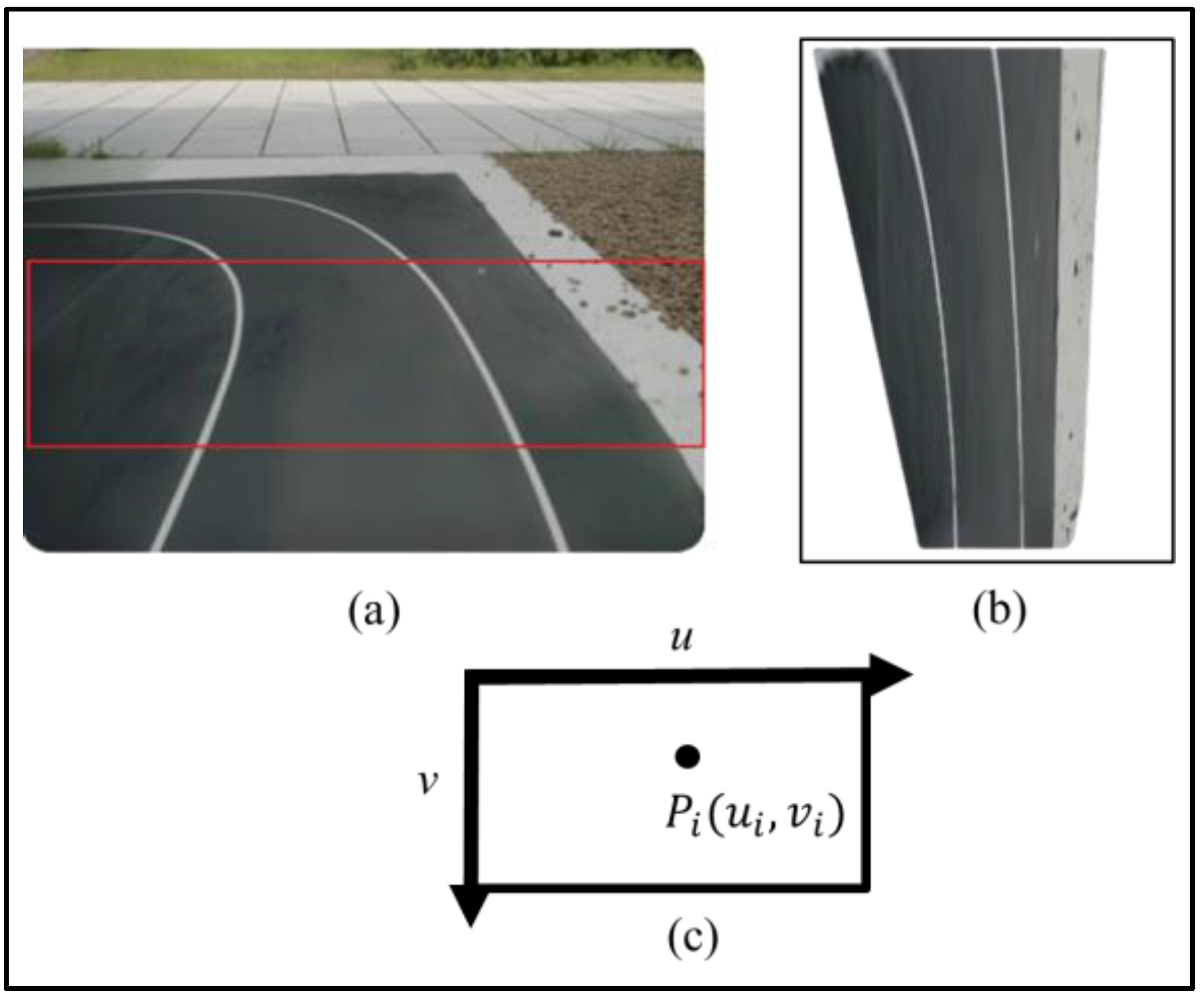

2.1. Image Pre-processing

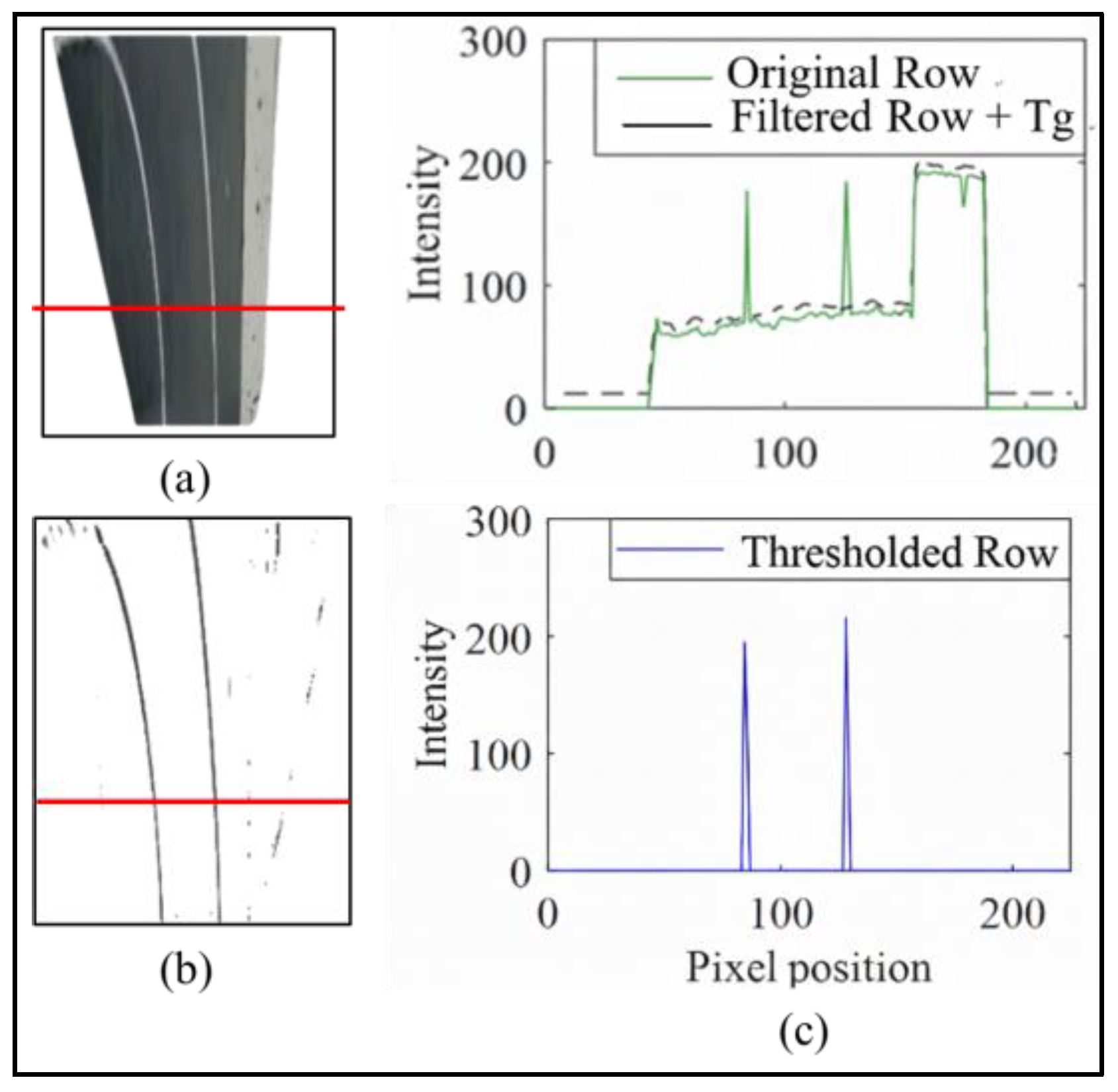

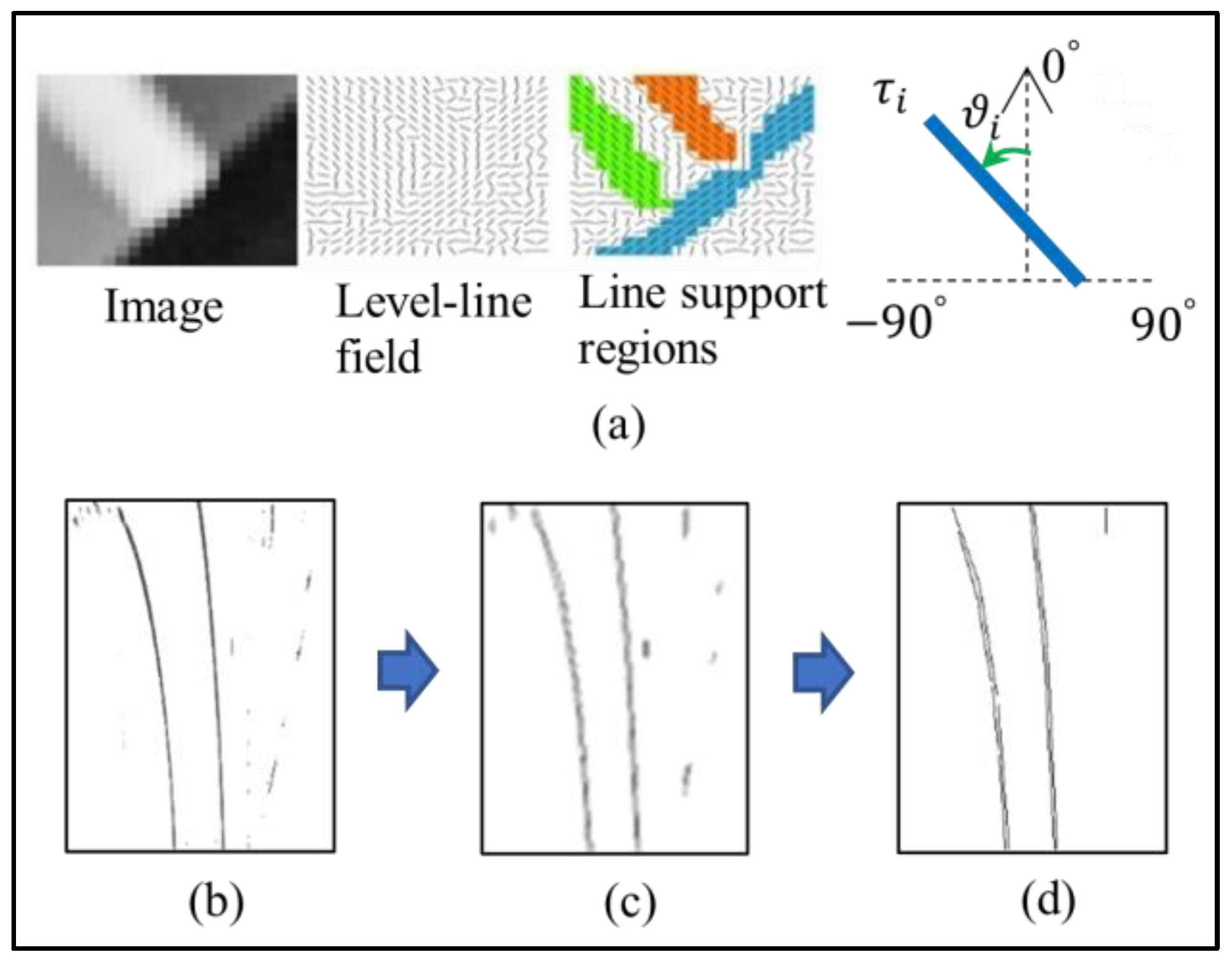

2.2. Lane Feature Extraction

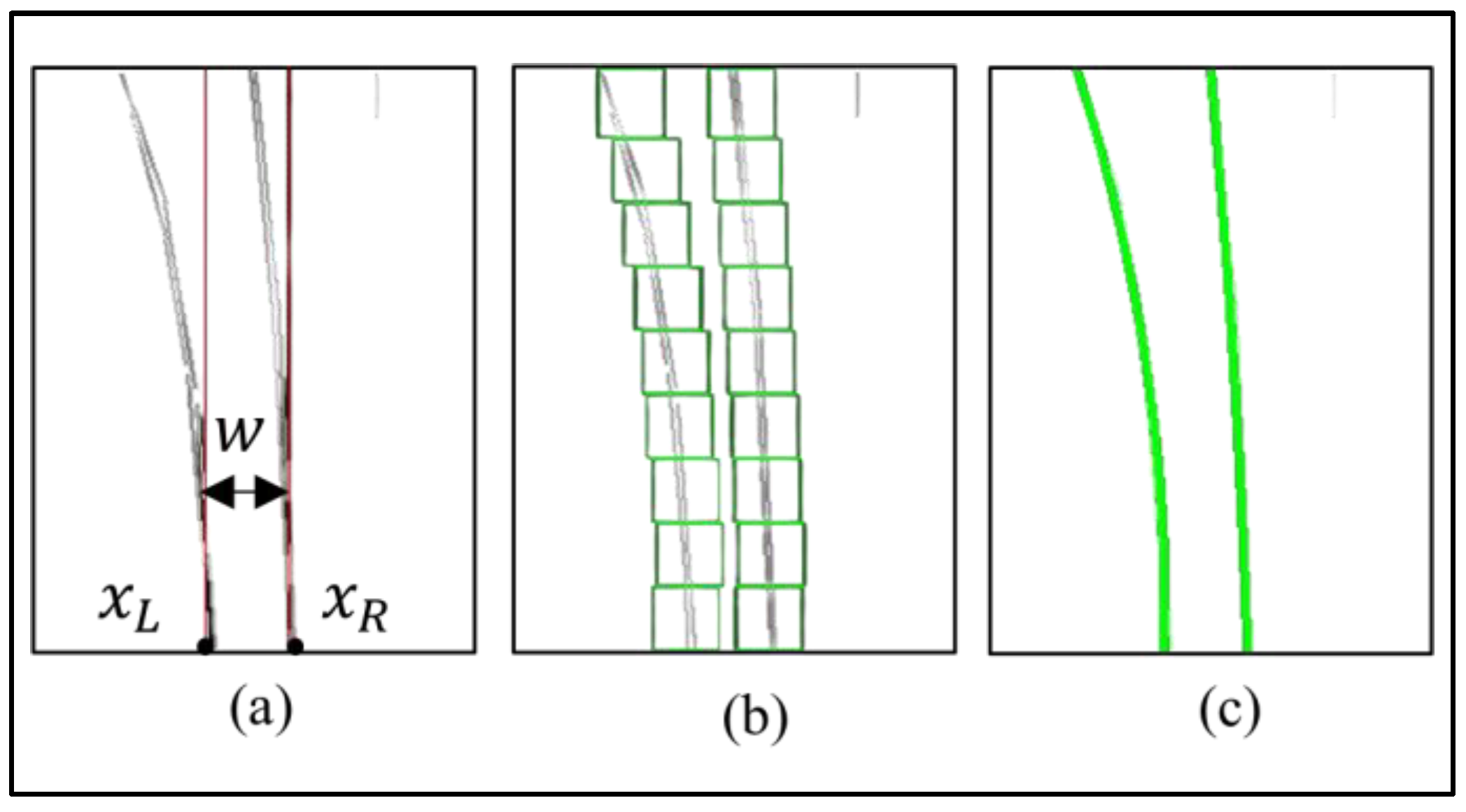

2.3. Geometric Priors of Lane Markings in BEV

2.4. Lane Model Fitting

3. Experimental verification

3.1. Failure Modes and Dataset Description

3.2. Quantitative Validation and Statistical Confidence

3.3. Computational Complexity and Runtime Analysis

3.4. Experimental Setup and Image Preprocessing

3.5. Lane Feature Extraction and Parameter Optimization

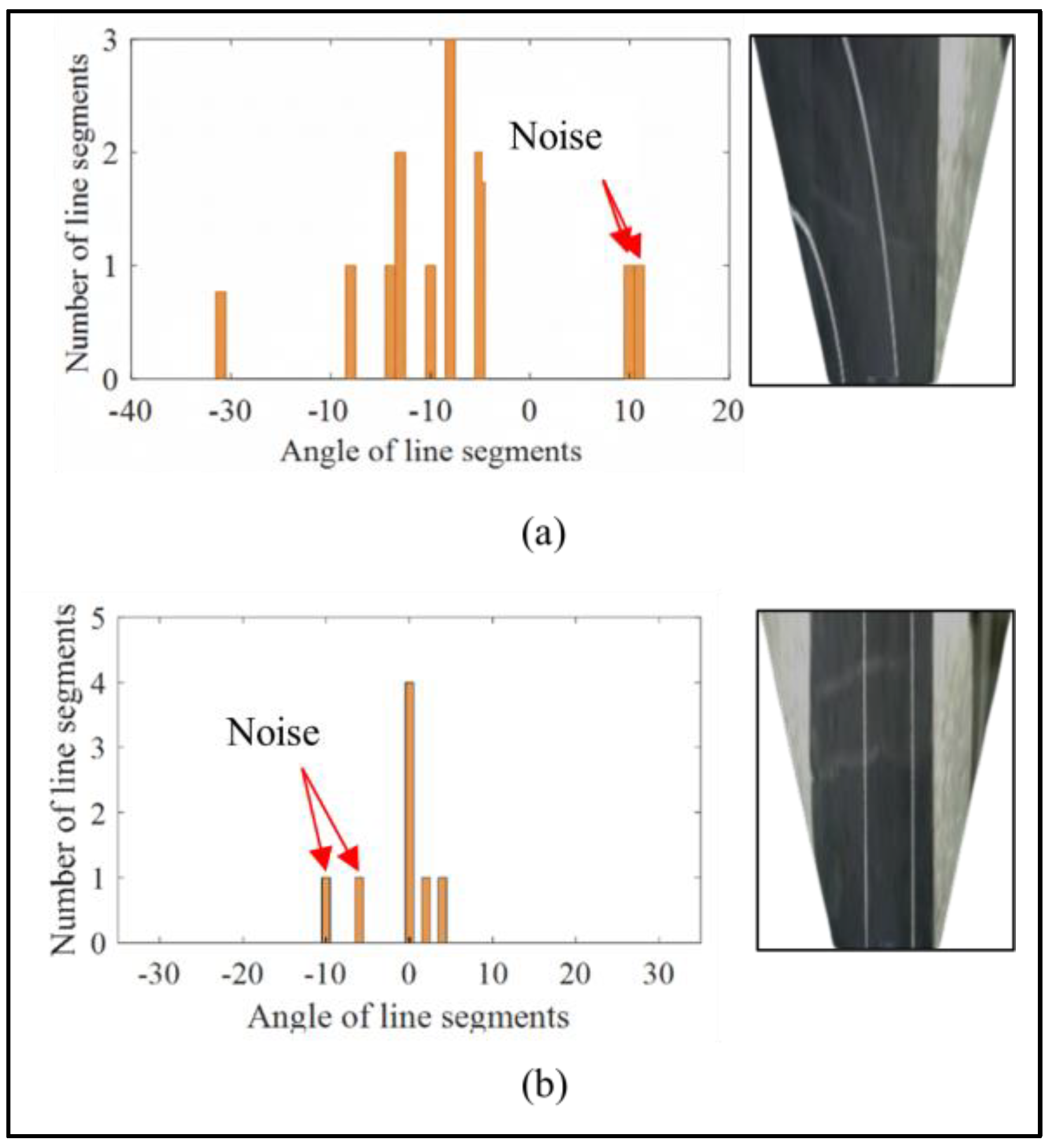

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis and Geometric Filtering

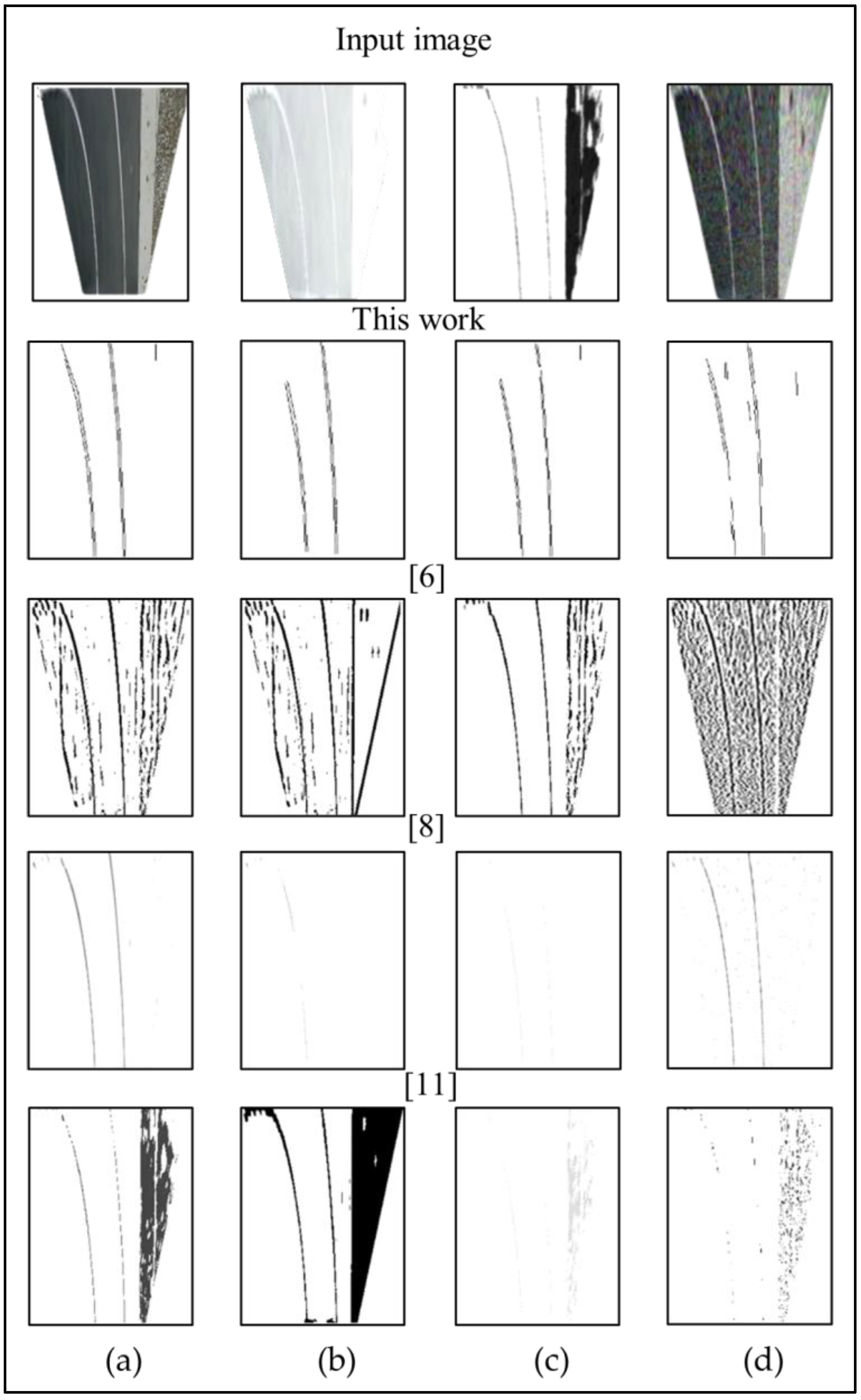

4. Performance Evaluation

4.1. Discussion on the Effect of Removing BLSF

5. Application in Autonomous Logistics

5.1. Enabling Sustainable Last-Mile Delivery

5.2. Overcoming Infrastructure and Regulatory Barriers

5.3. Integration with 5PL and Digital-Twin Logistics Ecosystems

6. Limitations and Future Work

7. Conclusions

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Future Work and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global status report on road safety 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, A.A.; Maity, T.; Yadav, R.K. Vehicle detection in intelligent transport system under a hazy environment: a survey. IET Image Processing 2020, 14(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Cao, D.; Velenis, E.; Wang, F.-Y. Advances in vision-based lane detection: algorithms, integration, assessment, and perspective on ACP-based parallel vision. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2018, 5, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.U.; Ali, A.R.; Hassan, A.; Ali, A.; Kazmi, W.; Zaheer, A. Lane detection using lane boundary marker network with road geometry constraints. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Snowmass Village, CO, USA, 2020; pp. 1834–1843. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgunalp, U. Robust lane-detection algorithm based on improved symmetrical local threshold for feature extraction and inverse perspective mapping. IET Image Processing 2019, 13, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.T.; Pham, C.C.; Tran, T.H.P.; Nguyen, T.P.; Jeon, J.W. Near real-time ego-lane detection in highway and urban streets. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics–Asia (ICCE-Asia), Seoul, South Korea, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Piao, J.; Shin, H. Robust hypothesis generation method using binary blob analysis for multi-lane detection. IET Image Processing 2017, 11, 1210–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Ye, P.; Han, S.; Sun, H.; Jia, Q. Road lane modeling based on RANSAC algorithm and hyperbolic model. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI), Shanghai, China, 2016; pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Ultra Fast Structure-aware Deep Lane Detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Ma, Z.; Liu, C.; Loy, C.C. Learning Lightweight Lane Detection CNNs by Self Attention Distillation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, South Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1013–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.B.; Wang, L.H.; Wang, K.C. Ultra-low complexity block-based lane detection and departure warning system. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2018, 29, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Lu, Y.R.; Yang, S.M. On the image sensor processing for lane detection and control in vehicle lane keeping systems. Sensors 2019, 19, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narote, S.P.; Bhujbal, P.N.; Narote, A.S.; Dhane, D.M. A review of recent advances in lane detection and departure warning systems. Pattern Recognition 2018, 73, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-H.; Hsu, H.P.; Yang, S.M. Development of an efficient and resilient algorithm for lane feature extraction in image sensor-based lane detection. Journal of Advances in Technology and Engineering Research 2019, 5(2), 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, M.; Zhan, X. A combined approach to single-camera-based lane detection in driverless navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium (PLANS), Monterey, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 1042–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, S.; Zhao, X.; Zu, G.; Lu, L.; Cheng, C. An algorithm for lane detection based on RIME optimization and optimal threshold. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 27244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Shan, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Shen, J. A lane detection method based on a ridge detector and regional G-RANSAC. Sensors 2019, 19(18), 4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.-C.; Tai, P.-L. Defect detection in striped images using a one-dimensional median filter. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Gioi, R.G.; Jakubowicz, J.; Morel, J.M.; Randall, G. A fast line segment detector with false detection control. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2010, 32, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkar, A.; Hayes, M.; Smith, M.T. A novel lane detection system with efficient ground-truth generation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2012, 13, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engesser, V.; Rombaut, E.; Vanhaverbeke, L.; Lebeau, P. Autonomous Delivery Solutions for Last-Mile Logistics Operations: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alverhed, E.; Hellgren, S.; Isaksson, H.; Olsson, L.; Palmqvist, H.; Flodén, J. Autonomous last-mile delivery robots: a literature review. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2024, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Shi, J.; Luo, P.; Wang, X.; Tang, X. Spatial as deep: Spatial CNN for traffic scene understanding. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, K.; Soussan, R. Unsupervised labeled lane markers using maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) Workshops, Seoul, South Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Storsæter, A.D. Camera-based lane detection—Can yellow road markings facilitate automated driving in snow? Vehicles 2021, 3(4), 664–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suder, J.; Podbucki, K.; Marciniak, T. Power Requirements Evaluation of Embedded Devices for Real-Time Video Line Detection. Energies 2023, 16, 6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabkowski, P.; Gal, Y. Real time image saliency for black box classifiers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

| Condition | With BLSF | Without BLSF | [12] |

|---|---|---|---|

| High curvature | 99% | 97% | 19% |

| Strong backlighting | 93% | 89% | 3% |

| Low contrast night | 92% | 92% | 36% |

| Heavy rain | 95% | 78% | 17% |

| Method | Backbone / Type | Dazzling Light (F1-score / IoU) | Night (F1-score / IoU) | FPS (CPU) | Power Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLSF (Ours) | Geometric (LSD) | 0.861 / 0.792 | 0.847 / 0.774 | 30.6 | High |

| Baseline (No BLSF) | Geometric (LSD) | 0.801 / 0.776 | 0.776 / 0.731 | 29.2 | High |

| Kuo et al. [12] | Geometric (Grid) | 0.654 / 0.582 | 0.698 / 0.610 | 28.5 | High |

| UFLD [9] | DL (ResNet-18) | 0.872 / 0.805 | 0.855 / 0.781 | 8.4 | Low |

| ENet-SAD [10] | DL (ENet) | 0.841 / 0.763 | 0.832 / 0.755 | 14.1 | Medium |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).