1. Introduction

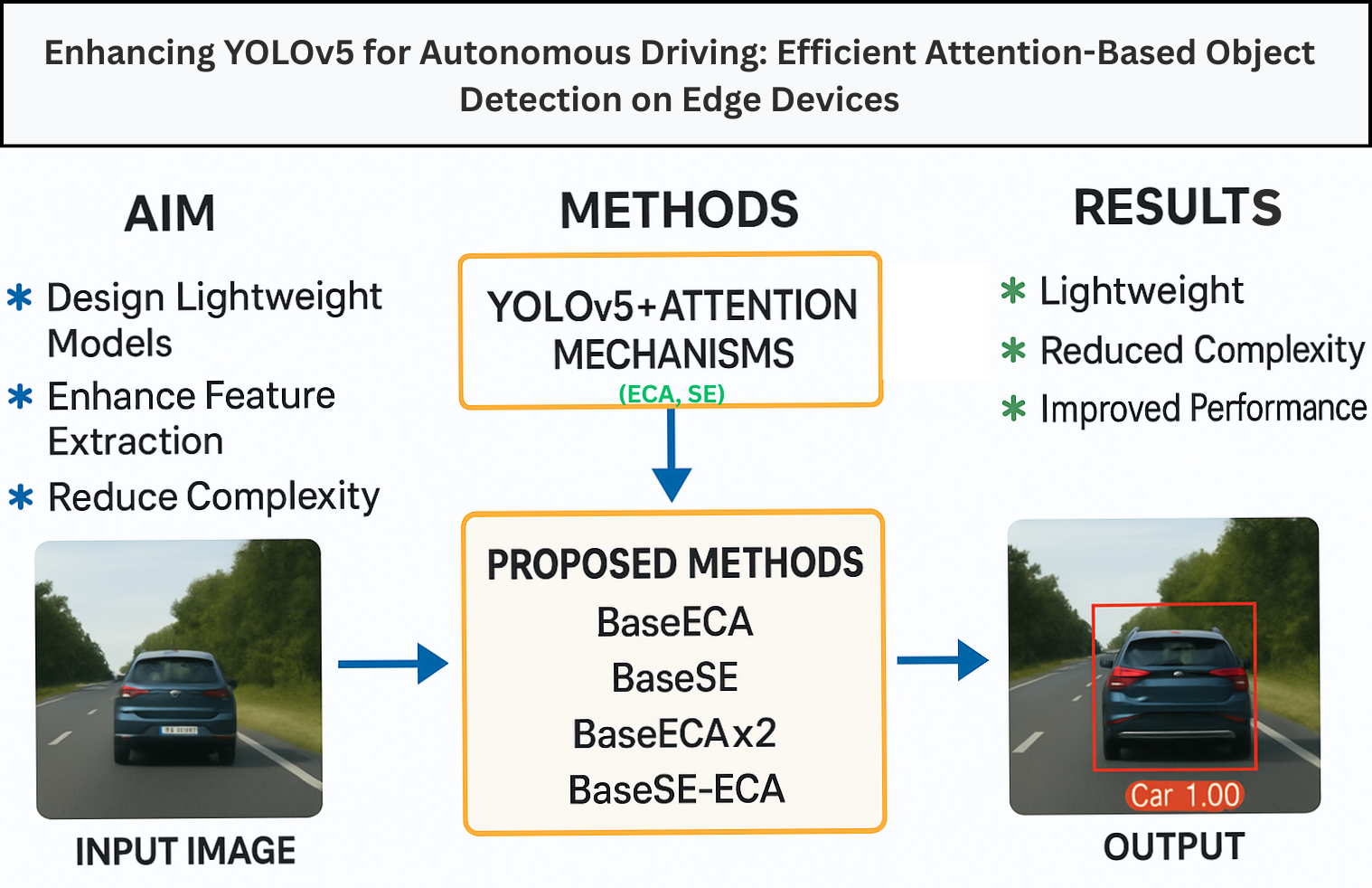

Autonomous driving has revolutionized modern transportation by improving road safety, enhancing efficiency, and enabling intelligent real-time decision-making capabilities[

1]. Object detection is pivotal in autonomous vehicle perception, enabling vehicles to identify and track surrounding objects accurately. Deep learning-based models, particularly YOLO versions, have emerged as high-performing solutions for real-time object detection as a result of their effectiveness in achieving an optimal trade-off between inference speed and detection accuracy[

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, despite their effectiveness, high computational demands, large model sizes, and inference latency make many models unsuitable for resource-constrained edge devices used in autonomous vehicles[

6,

7,

8]. Earlier detection frameworks, such as Faster R-CNN[

9], SSD[

10], and initial YOLO versions[

11], demonstrated promising accuracy but suffered from computational inefficiency that hindered real-time deployment [

12,

13,

14]. More recent architectures, including YOLOv4-5D, YOLOX, and EfficientDet, have sought to improve detection accuracy and efficiency. However, their parameter count and high FLOPs requirements continue to pose challenges for deployment in embedded autonomous systems [

15,

16,

17]. Given these limitations, research has increasingly focused on lightweight architectures and attention mechanisms to enhance computational efficiency and detection performance [

18,

19]. This study introduces enhanced lightweight object detection models derived from YOLOv5s, incorporating Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) and Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) mechanisms to improve feature selection and computational efficiency. These attention mechanisms improve feature selection while reducing computational overhead and enhancing detection performance in real-time settings. SE modules adaptively recalibrate channel-wise feature responses, strengthening relevant features while suppressing less useful ones [

13], while ECA refines attention mechanisms by reducing the complexity of channel dependencies [

12]. Training and testing of the proposed models were carried out using the KITTI dataset, a well-established standard for evaluating autonomous driving perception systems. KITTI was chosen due to its well-structured labeling system and diverse yet controlled driving scenarios, making it ideal for assessing model performance in standard conditions. While KITTI provides valuable insights into performance in typical urban and highway environments, it might not effectively encompass the complexities of real-world autonomous driving conditions. To further evaluate model robustness, we evaluated our models on the BDD-100K dataset, which features challenging scenarios, including low-light environments, occlusions, and motion blur. This additional evaluation highlights the model’s strengths and constraints in complex real-life situations. The observed performance gap on BDD-100K is attributed to ECA’s focus on lightweight channel recalibration, which may limit its effectiveness in scenarios requiring more complex spatial modeling. This evaluation underscores the need for future improvements to address challenging environmental conditions in autonomous driving.

The primary contributions of this research are as follows:

Proposition of an optimized lightweight object detection model that balances accuracy on edge devices, computational efficiency, and deployment feasibility.

Improvement of YOLOv5 by integrating SE and ECA attention mechanisms into its architecture to enhance feature selection and detection precision without increasing computational overhead.

Introduction of extensive performance evaluation on autonomous driving datasets, including the KITTI dataset for standard conditions and the BDD-100K dataset to assess model robustness in challenging scenarios.

Benchmark analysis with cutting-edge approaches to lightweight object detection models demonstrates improved trade-offs between computational efficiency and performance.

This study provides a cost-effective yet high-performance solution for edge deployment in autonomous vehicles. Our findings provide an affordable solution with state-of-the-art detection accuracy, enabling more practical real-time deployment in self-driving systems.

Application Scenarios: The proposed models are suitable for edge devices with limited computational capacity. Application areas include autonomous driving perception systems, smart surveillance infrastructures, and IoT-enabled monitoring environments, where balancing computational efficiency, low latency, and detection precision is critical. Our models are particularly suited for embedded AI systems operating in dynamic and resource-limited environments by reducing computational load without compromising detection accuracy. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section II reviews related work on lightweight object detection and attention mechanisms. Section III describes the proposed methodology and model architecture. Section IV presents the experimental results along with a comparative performance analysis. Section V discusses the implications of the findings, and Section VI concludes the study while highlighting potential directions for future research.

2. Related Work

Deep learning approaches to object detection have achieved impressive results across various applications, making them highly applicable in complex scenarios such as autonomous driving. However, models that achieve high accuracy often incur substantial computational costs. To mitigate this, researchers have proposed lightweight architectures, optimization techniques, and edge-cloud frameworks to enhance detection performance without increasing computational demands. This section categorizes the most relevant studies into lightweight detection models, generative approaches, edge-based optimizations, performance improvements under challenging conditions, and small-object detection strategies.

2.1. Lightweight Object Detection Models

One-stage detectors like YOLO are extensively used in autonomous driving for their computational efficiency and real-time performance. Numerous lightweight variants have been proposed to enhance YOLO’s efficiency for deployment on edge devices with limited resources.

Zhou et al. [

15] introduced MobileYOLO, which integrates MobileNetV2 and Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) to minimize computational complexity without sacrificing accuracy. Their model achieved 90.7% accuracy on the KITTI dataset, with an 80% reduction in model size compared to YOLOv4, enhancing its applicability in real-time edge computing scenarios. Similarly, ShuffYOLOX replaced CSPDarkNet53 with a ShuffleDet backbone, improving computational efficiency and achieving a 92.2% mAP, thus demonstrating its potential for autonomous navigation [

20].

Yasir et al. [

21] proposed SwinYOLOv7, which combines Swin Transformers with YOLOv7 for robust ship detection in SAR imagery. Although it delivers cutting-edge performance, the use of transformer modules and anchor-free heads adds significant complexity. limiting its feasibility for edge deployment.

Yang and Fan [

22] introduced YOLOv8-Lite, a lightweight adaptation of YOLOv8 optimized using the FastDet backbone, TFPN pyramid structure, and CBAM attention. Their model performed well on the NEXET and KITTI datasets, balancing speed and accuracy for real-time intelligent transportation applications. However, the reliance on transformer-style feature fusion (TFPN) and CBAM attention may still impose constraints under stricter edge limitations.

Similarly, Wei et al. [

23] developed SCCA-YOLO, integrating spatial and channel collaborative attention mechanisms to improve detection in wildlife monitoring. Yet, Performance was assessed on a custom dataset alongside the COCO128 subset, rather than on real-world urban driving benchmarks. While these attention-based designs offer practical enhancements, their applicability to real-time, street-level edge deployments remains to be validated.

Beyond structural modifications, recent studies have further explored integrating generative approaches to enhance object detection systems for autonomous driving. Although transformer-based detectors such as DETRs [

24] have surpassed YOLO models’ accuracy, their high computational cost and latency hinder real-time use on edge devices. In contrast, our attention-enhanced YOLOv5 variants are explicitly optimized to trade off accuracy and efficiency, ensuring suitability for low-power embedded systems, latency-sensitive deployment scenarios.

2.2. Emerging Generative Approaches

Generative AI has recently been employed to enhance object detection and perception tasks, especially in autonomous systems. For instance, synthetic data generation using generative AI has improved robustness and generalization in complex driving environments [

25,

26]. Additionally, generative architectures such as GenCoder [

27] have been proposed for anomaly detection in intra-vehicle networks, while multi-modal generative communication systems have been explored for intelligent vehicular ecosystems [

28]. These trends indicate a growing synergy between generative and discriminative models.

Our work, however, focuses on optimizing discriminative YOLO-based models forLow-latency use cases under edge constraints. For instance, Zhang et al. [

29] proposed CAE-YOLOv5, which integrates CBAM and ECA attention into YOLOv5, improving detection accuracy to 96.3%. However, added attention layers increased inference time, limiting their suitability for edge deployment. Likewise, YOLOv5-NAM [

30] integrates a Normalization-based Attention Module (NAM), improving small object detection and increasing mAP by 1.6% over the baseline while preserving real-time performance.

In deviation from earlier works focusing solely on lightweight design or attention-based accuracy gains, we propose three YOLOv5-based models—BaseECA, BaseECAx2, and BaseSE-ECA—each exploring distinct architectural trade-offs. BaseECA integrates ECA into the backbone to enhance channel-wise attention with minimal overhead. BaseECAx2 extends attention to the backbone and detection head for improved feature fusion. BaseSE-ECA combines SE attention in the backbone with ECA in the head to capture global and local contextual features. These models are thoroughly benchmarked across mAP, FPS, parameter count, and GFLOPs to validate their effectiveness in edge-constrained, real-time autonomous driving applications.

2.3. Edge-Based and Energy-Efficient Object Detection Approaches

Object detection models designed for edge deployment must prioritize energy efficiency and low computational cost. Liang et al.[

19] proposed Edge YOLO, which offloads intensive computations to the cloud while performing lightweight inference on edge devices. Though effective, its dependency on persistent connectivity limits its suitability for fully offline systems.

Cai et al. [

17] introduced a pruning-based version of YOLOv4, improving inference speed by 31.3% while maintaining competitive performance. Similarly, Wang et al. [

31] proposed CRL-YOLOv5, which integrates Receptive Field Blocks (RFB) and CBAM to enhance small object detection by 5.4%. However, increased complexity and memory usage hinder their application on embedded devices.

While Pruning, edge-cloud cooperation, and attention-based enhancements contribute to improved efficiency, achieving the optimal trade-off among accuracy, latency, and resource utilization remains a persistent challenge. Unlike generative or hybrid models, our attention-enhanced YOLOv5 variants are explicitly designed to offer a balanced solution, providing robust detection performance with minimal computational cost, making them more viable for real-time edge-based autonomous systems.

2.4. Object Detection Performance in Challenging Driving Environments

Autonomous driving systems must reliably detect objects under adverse conditions, such as occlusion, high-speed motion, and low lighting. Jia et al. [

32] optimized YOLOv5 through structural reparameterization and Neural Architecture Search, achieving 96.1% accuracy and 202 FPS on the KITTI dataset. Liu et al. [

33] introduced a lightweight model for traffic sign detection using Dense CSP modules, improving efficiency by 5.28%. Wang et al. [

34] introduced YOLOv3-MT, which integrates Kalman filtering and DIoU-NMS for robust multi-object tracking.

Recent work has also improved detection in aerial and nighttime scenarios. Li et al. [

45] proposed R-YOLOv5, which achieved 90.23% mAP with only 2.02M parameters on UAV datasets. Almujally et al. [

46] enhanced nighttime surveillance using MIRNet-based low-light enhancement with YOLOv5, reaching 92.4% precision. While effective, these models are generally tailored for specialized environments. In contrast, our work focuses on versatile, general-purpose detection under various autonomous driving conditions. These studies underscore the critical role of attention and feature enhancement in improving detection robustness.

2.5. Small-Scale Object Detection in Autonomous Navigation

Detecting small objects is particularly challenging due to low resolution, occlusion, and background clutter. Various studies have applied super-resolution techniques and advanced attention mechanisms to mitigate these issues [

47]. Zhao et al. [

35] introduced SatDetX-YOLO, an improved YOLOv8-based model for detecting vehicles in satellite imagery. The model incorporates Deformable Attention Modules (DAM) and a Maximum Probabilistic Distance IoU (MPDIoU) loss, improving precision by 3.5% and recall by 3.3%. While tailored for satellite images, its focus on refined attention for small object detection aligns with our approach to enhancing YOLOv5’s performance in real-time, complex driving environments.

These studies emphasize the importance of advanced attention-based architectures and super-resolution techniques for enhancing small object detection in complex environments.

Table 1 summarizes related works, detailing recent approaches’ methods, results, and key limitations. While many techniques demonstrate strong performance, they often suffer from increased computational costs or limited adaptability in real-world scenarios. Building on the comprehensive survey by Adam and Tapamo [

36], which classifies deep learning-based vehicle detection methods and highlights the challenges of edge deployment, this study introduces optimized YOLOv5 variants incorporating SE and ECA attention modules. Unlike the survey’s broader synthesis, our work presents and evaluates concrete, lightweight models that balance accuracy and efficiency for real-time applications in autonomous driving.

3. Materials and Methods

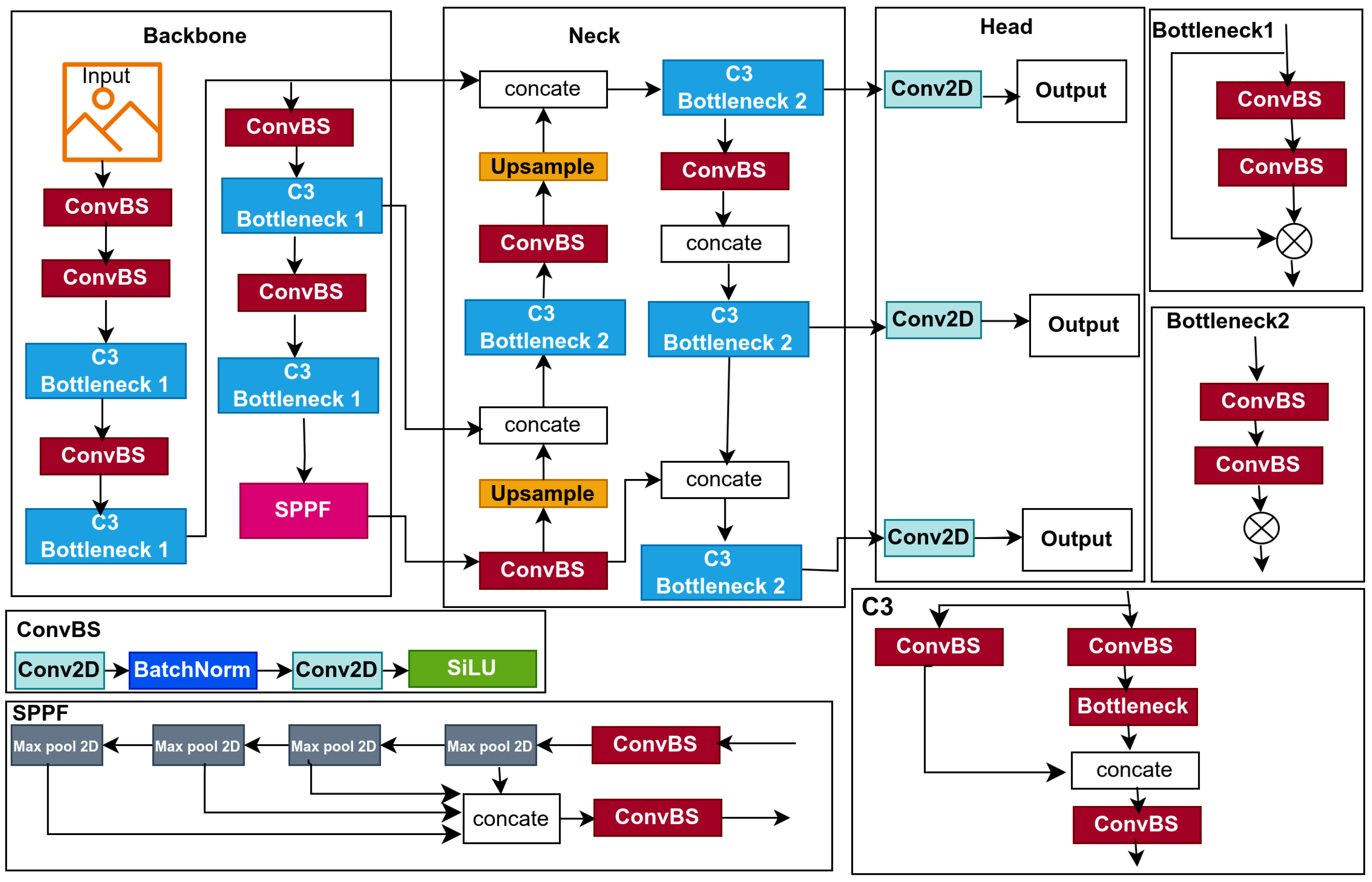

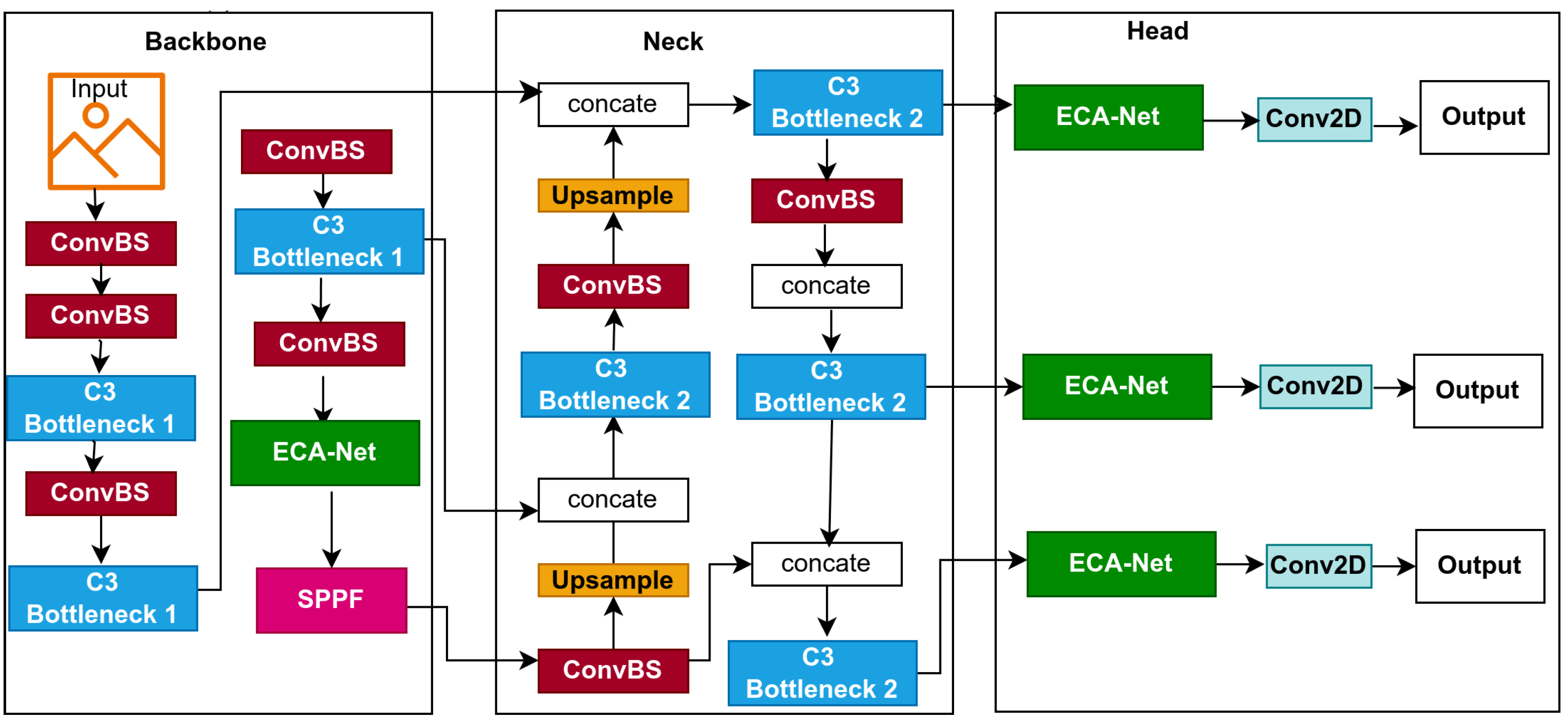

This study introduced lightweight models for edge devices for computation cost-wise and affordability; the models based on YOLOv5s, as a single-stage object detector, predict bounding boxes, class probabilities, and abjectness scores simultaneously, YOLOv5s designed for real-time object detection, balancing inference speed with detection precision, its architecture in

Figure 1, in this section, we provided a detailed explanation of the baseline model and the optimization techniques that used to improve the baseline model which resulted in proposing three lightweight models namely: BaseECA, BaseECAx2, BaseSE-ECA as their architectures explain in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 respectively. These models integrate ECA and SE mechanisms into the YOLOv5s architecture to improve channel-wise attention and feature selection. ECA and SE are lightweight mechanisms that will enhance the model’s focus on significant features by filtering out irrelevant details, reducing the model’s size, and improving its speed. ECA achieves this by adaptively recalibrating channel-wise feature responses without dimensionality reduction; SE leverages global average pooling combined with fully connected layers to capture channel dependencies.

3.1. YOLOv5

YOLOv5, which stands for You Only Look Once version five, is a highly optimized object detection model introduced by Ultralytics [

38]; it is highly efficient and achieves cutting-edge results on the widely recognized Microsoft COCO benchmark [

37], making it a widely adopted model for real-time object detection tasks owing to effectively balancing speed and accuracy. YOLOv5 is built upon three fundamental components that define its architecture: a Backbone, a Neck, and a Head, as shown in

Figure 1. The backbone is based on CSPDarknet53, an enhanced variant of Darknet53 used in YOLOv4 [

39]. It integrates cross-stage partial (CSP) connections, which partition the feature maps into two separate segments, process one through a dense block, and concatenate the outputs, reducing computational costs and improving gradient flow. Additionally, YOLOv5 introduces a Focus layer at the beginning of the backbone, which slices the input image into four parts and concatenates them, reducing spatial dimensions while preserving channel information to enhance efficiency. The Neck in YOLOv5 employs the Path Aggregation Network (PANet) to aggregate and enhance features extracted from different backbone levels. PANet extends the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) by incorporating a bottom-up path augmentation, which complements the top-down path of FPN and enhances object localization. Features from multiple levels are concatenated and refined through convolutional layers to improve multi-scale feature representation, ensuring robust detection across varying object sizes. The detection head generates the final predictions based on the YOLOv3 head [

40]. It comprises three key components: bounding box predictions, objectness scores, and class probabilities. Bounding boxes are defined by their center point (x, y), as well as their width (w) and height (h), parameterized relative to grid cells and anchor boxes. The objectness score is a binary classification value that indicates whether a bounding box contains an object. At the same time, class probabilities represent a probability distribution over detected classes computed using sigmoid activation to support multi-label classification. The image undergoes initial processing in the input layer prior to being forwarded to the backbone for feature extraction. The backbone produces feature maps at multiple scales fused in the neck to produce three features: 80×80 resolution for detecting small objects, 40×40 resolution for medium objects, and 20×20 resolution for large objects. The output features are used in the head for object prediction, where confidence scores and bounding-box regression are performed using preset anchors. Finally, confidence thresholds and non-maximum suppression (NMS) are applied to filter out irrelevant detections and produce the final predictions.

3.2. Proposed Models

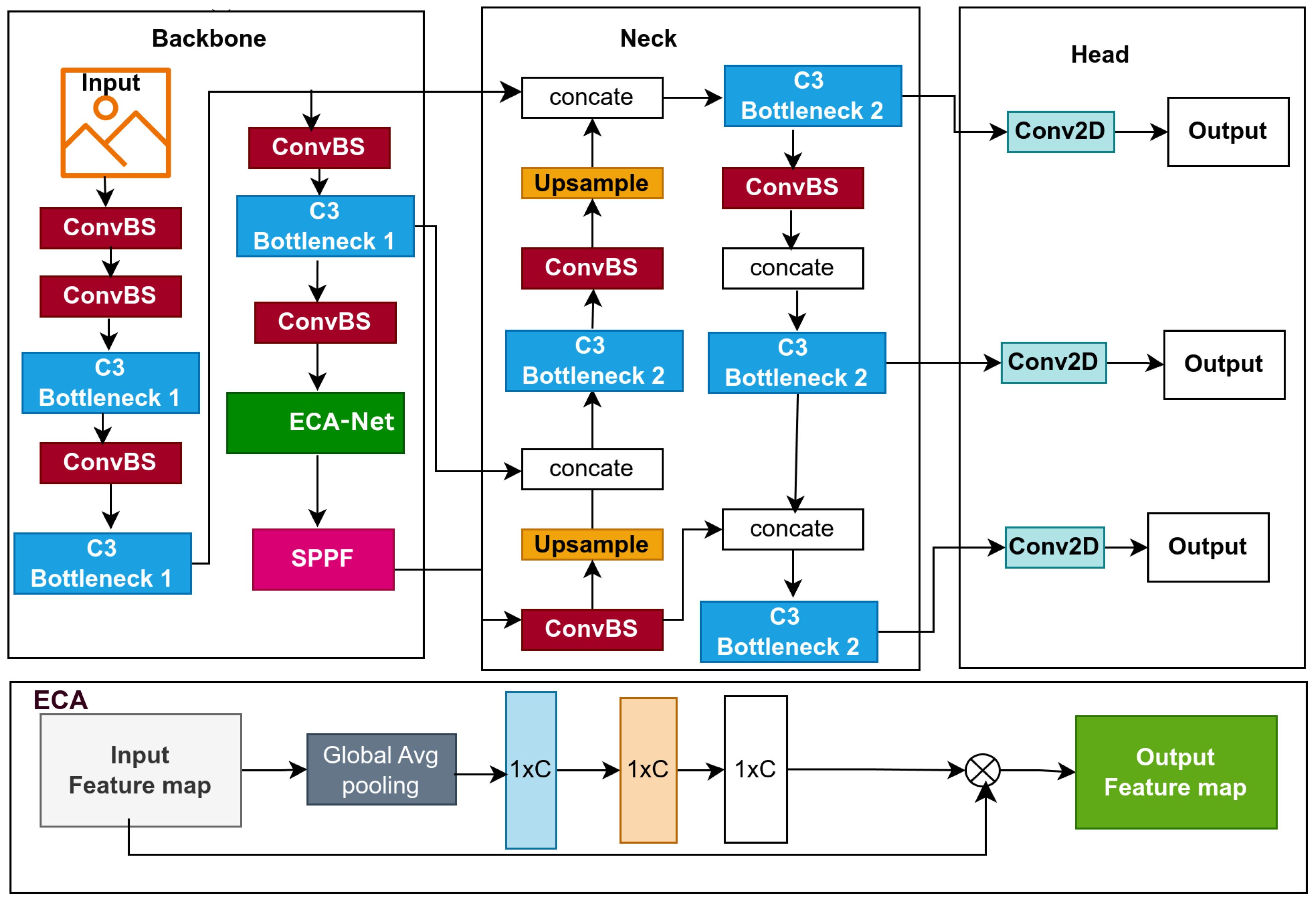

3.2.1. BaseECA Model

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) used in object detection must efficiently extract features while balancing accuracy and computational complexity. The YOLOv5 model employs Cross-Stage Partial (CSP) Bottleneck modules (C3 layers) to capture hierarchical features. However, the C3 module introduces many parameters and increases the model’s computational load, raising the question of whether reducing the number of parameters without compromising performance is possible. To answer that, we propose a novel optimized model called BaseECA by integrating Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) into the backbone of the model, as shown in

Figure 2. Specifically, we replace the C3 module before the Spatial Pyramid Pooling - Fast (SPPF) layer integrated with ECA, as this layer is crucial in refining high-level features before they are passed to the neck and head. ECA enhances feature representation by applying channel attention to emphasize the most informative features, allowing the network to focus on essential patterns while significantly minimizing the number of parameters and computational overhead. The original C3 module, composed of three convolutional layers with CSP connections, is responsible for extracting high-level features. The model preserves representative feature extraction by integrating ECA while improving computational efficiency.

-

Parameter Complexity in the C3 Module: The C3 module in YOLOv5 performs convolutional operations while utilizing CSPNet’s partial feature reuse mechanism. It consists of two convolutional layers applied to half of the input channels and one applied to all channels, followed by batch normalization and non-linear activation functions (see

Figure 2). The C3 component in layer nine introduces over 1.18 million trainable parameters, significantly contributing to the architecture’s computational complexity.

The total number of trainable parameters in the C3 module can be estimated as:

Where C represents the number of input and output channels, and K indicates the kernel size.

-

Parameter Complexity in the ECA Module: The Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module is an efficient module designed to optimize feature selection while maintaining computational efficiency. Compared to the C3 module, the ECA module applies a 1D convolution-based attention mechanism to refine channel-wise features.

Replacing this modification reduces the parameter count from 1.18 million to just 1, enhancing model efficiency. This transformation lowers memory requirements and reduces computational cost (GFLOPs) while maintaining or improving feature refinement quality, demonstrating the effectiveness of ECA in optimizing YOLOv5’s backbone.

3.2.2. BaseECAx2 Model

Features improvement across multiple scales in deep learning models for object detection improves accuracy. However, how can we enhance feature representation while keeping computational costs minimal? To address this challenge, we introduce BaseECAx2, the architecture in

Figure 3, an extension of the BaseECA architecture that further integrates the ECA module directly into the backbone architecture and the detection head. This enhancement enables the model to apply channel attention to the backbone and aggregated multi-scale features in the head, improving feature selection and object detection accuracy across varying object sizes. In BaseECAx2, the C3 module in layer nine of the backbone is replaced with ECA, allowing the model to refine extracted features early in the network by emphasizing the most informative channels. An ECA module is positioned after the C3 module in the detection head, enhancing the feature maps used for final predictions. At this stage, the detection head operates at three resolutions, 80×80, 40×40, 20×20, and ECA, allowing the model to apply adaptive channel attention at multiple scales, improving object localization and classification precision. To analyze the computational impact, consider the parameter complexity of ECA. Unlike the C3 module, which consists of multiple convolutional layers, ECA is lightweight and only requires a 1D convolution with an adaptive kernel size k, given by:

Where

C and

K are as previously defined, by replacing C3 in the backbone and inserting ECA in the head, BaseECAx2 minimizes the model’s parameters and computational overhead while sustaining or enhancing detection performance. Therefore, it ensures that the feature maps are refined before being fed into the neck and head, improving the feature discrimination across scales and resulting in a model that successfully balances performance and computational efficiency, making BaseECAx2 a powerful solution for real-time object detection.

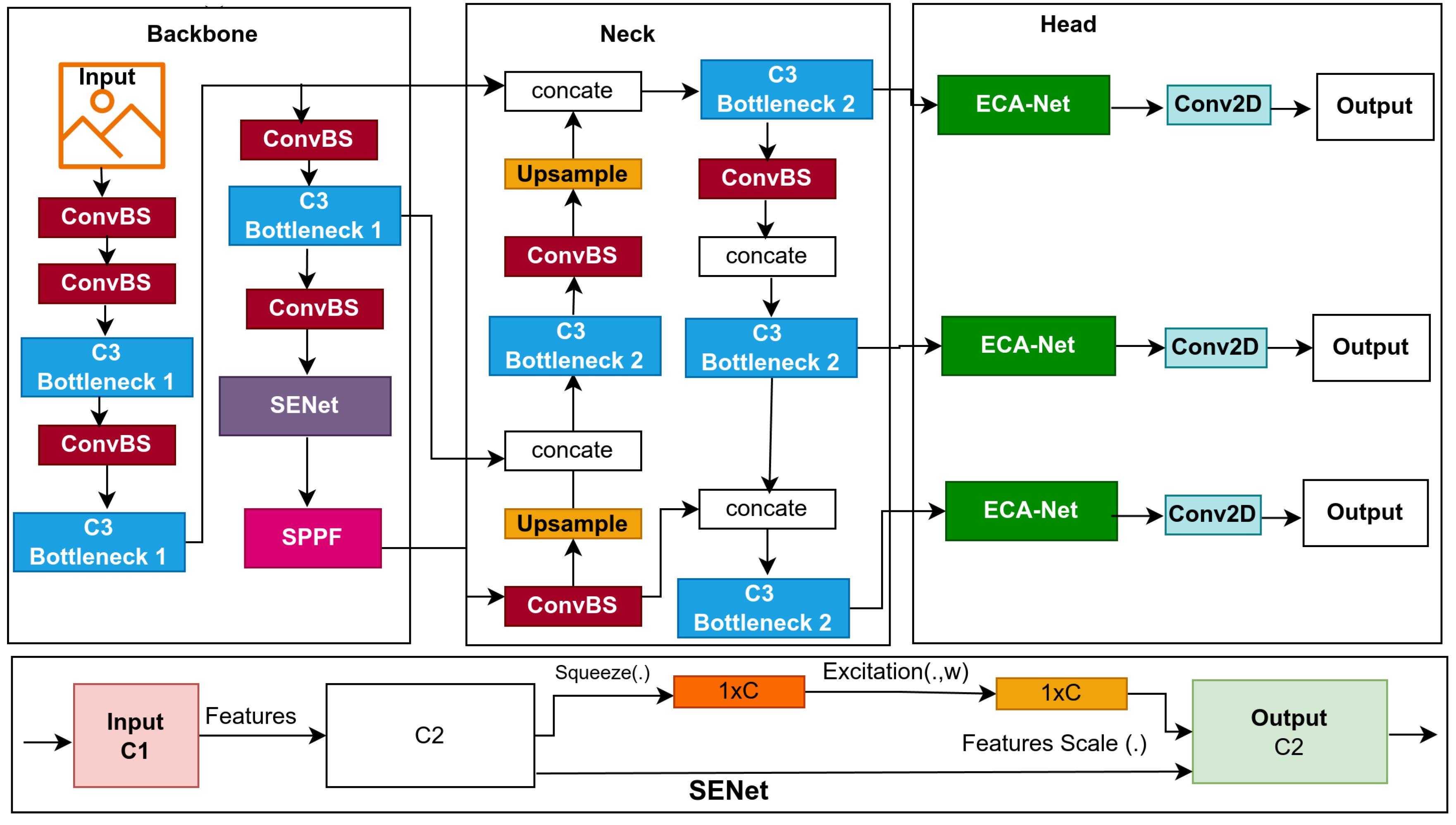

3.2.3. BaseSE-ECA

While BaseECAx2 improves multi-scale feature selection by incorporating Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) in both the backbone and detection head, one question remains: Can we further refine feature representation to improve detection precision? To address this, we introduce BaseSE-ECA, which combines the strengths of Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) and ECA modules to optimize feature extraction and refinement. Building upon BaseECAx2, BaseSE-ECA modifies the backbone by replacing the final C3 module with an SE module while keeping the ECA module in the detection head, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The SE module strengthens channel-wise feature representation by modeling interdependencies between channels, allowing the model to refine its feature selection. The ECA module in the head ensures that the final feature maps used for detection are optimally recalibrated, improving classification and localization accuracy. This strategic combination enables the model to benefit from SE’s ability to capture complex channel dependencies and ECA’s computational efficiency in attention refinement. The Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module applies a lightweight 1D convolution-based mechanism to enhance channel-wise features without dimensionality reduction. Unlike SE, which introduces fully connected layers, ECA maintains spatial information while recalibrating the importance of features. Mathematically, the ECA operation can be calculated in the following equation:

Where

denotes global average pooling across the spatial dimensions, Conv1D uses a small, dynamically selected kernel size

K to model local channel interactions, and

represents the sigmoid activation function responsible for scaling the attention weights. On the other hand, the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module follows a two-step process: the first step is Squeeze, which is Global Average Pooling (GAP), compressing spatial dimensions into a channel descriptor. The second is Excitation, which includes two fully connected layers that apply transformations to model channel dependencies. Mathematically, the SE operation is given by:

Where and refer to the trainable weights of the two fully connected layers, denotes the ReLU activation function, and is the sigmoid activation function responsible for rescaling the feature responses.

4. Experments

4.1. Dataset and Preporcessing

-

KITTI dataset stands out as one of the leading benchmark datasets to evaluate computer vision algorithms in autonomous driving scenarios. It provides diverse real-world driving scenes captured using high-resolution stereo cameras and 3D LiDAR sensors. The dataset includes various levels of occlusion and truncation, making it well-suited for testing the robustness of lightweight object detection models under challenging conditions.

The dataset is partitioned into three distinct subsets: for training, 5220 images; for validation, 1495 images; and for testing, 746 test images. It includes eight object categories, covering common road participants: car, van, truck, pedestrian, person (sitting), cyclist, tram, and miscellaneous. The dataset contains 40,484 labeled objects, averaging 5.4 annotations per image across these eight classes.

Data preprocessing was conducted prior to training to ensure consistent input structure with the proposed detection models and improve training efficiency. All images were scaled to a 640 × 640 pixels resolution while maintaining the aspect ratio using stretching techniques. Input pixel values were normalized to a range of [0,1] to ensure stable convergence during training. Data augmentation techniques, including random horizontal flipping, brightness adjustment, and affine transformations, were incorporated to improve generalization and model robustness.[

41]

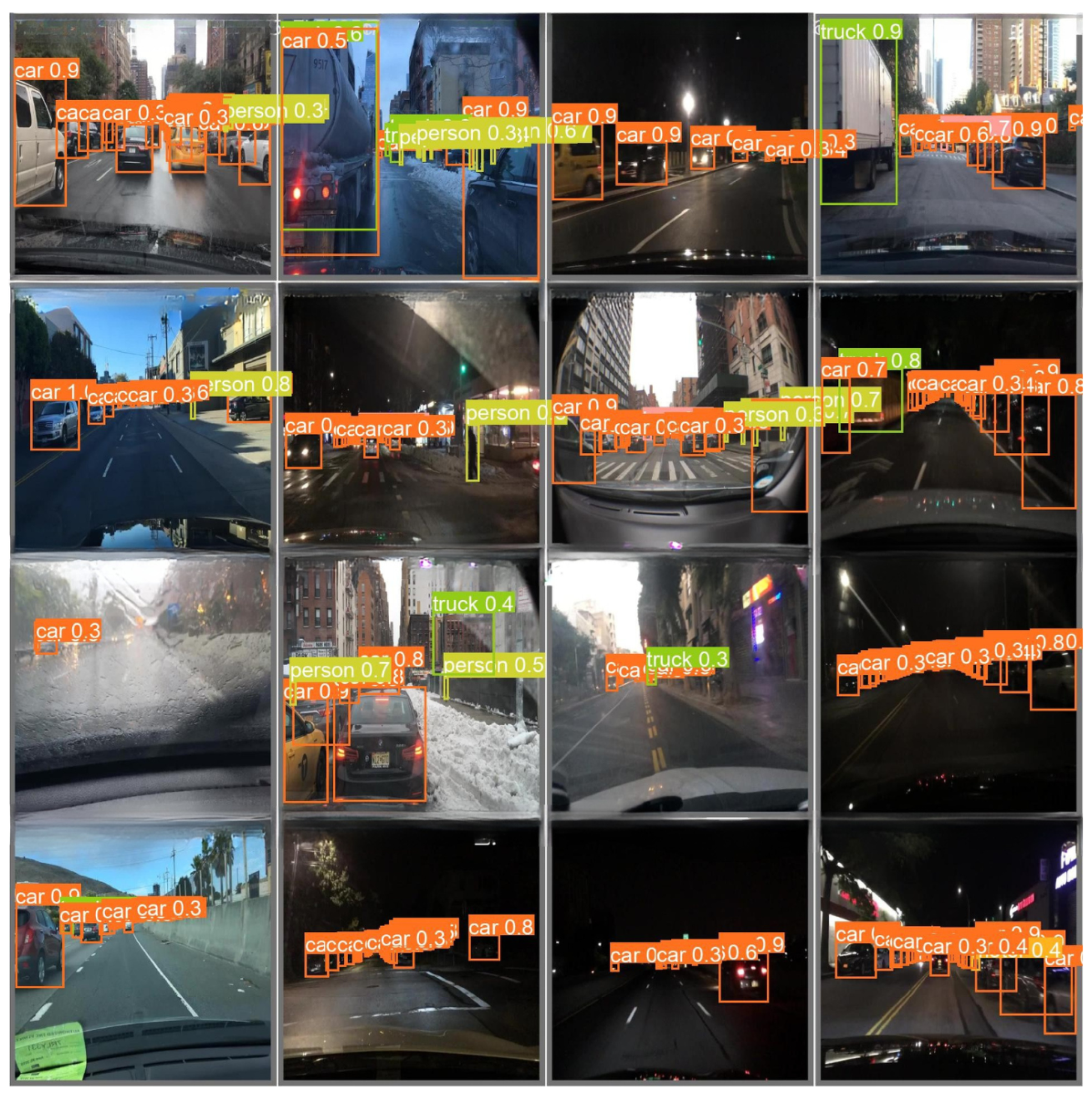

The KITTI dataset served as the primary evaluation benchmark in this study due to its well-structured annotations and established reputation for testing object detection models in autonomous driving scenarios. The proposed models achieved strong performance on KITTI, which was used as a reference to measure the models’ effectiveness in standard conditions. See some samples for detection results in

Figure 7.

BDD-100K Dataset is a comprehensive driving video dataset tailored for autonomous driving research, featuring 100,000 samples of annotated video clips collected from diverse geographic locations and environmental conditions, including urban streets, highways, and residential areas. The dataset features weather conditions such as explicit, cloudy, rainy, and foggy scenarios and daytime and nighttime driving scenes, making it suitable for evaluating model robustness in complex environments [

42]. The BDD-100K dataset was used to explore the limitations of the proposed models under more complex conditions. See some samples for detection results in

Figure 8. While the models demonstrated strong performance on KITTI, they exhibited reduced performance on BDD-100K, particularly in scenes with poor lighting, motion blur, and occlusions. This evaluation provided insights into the models’ robustness and highlighted areas for future improvements, such as enhanced temporal feature fusion and improved noise handling techniques.

4.2. Implementation and Training

All three models (BaseECA, BaseECAx2, and BaseSE-ECA) were implemented using the PyTorch framework (version 2.0.1+cu117) and trained on the KITTI dataset. The training setup included a batch size of 8, an initial learning rate of 0.01, and the SGD optimizer with momentum (0.937) and weight decay (0.0005). Data augmentation techniques were applied to enhance generalization, including mosaic augmentation (probability 1.0), random horizontal flipping (probability 0.5), hue adjustment (±0.015), saturation adjustment (±0.7), brightness adjustment (±0.4), image scaling (±0.5), and image translation (±0.1). The training was conducted over 300 epochs for each model on an NVIDIA Quadro P600 GPU (4 GB VRAM), leveraging CUDA 11.7 for accelerated computation. The process used the YOLOv5s framework, with Python 3.11.4 and PyTorch 2.0.1+cu117, running on an Ubuntu 24.04 LTS system with an Intel Core i7-8850H CPU and 32 GB RAM. A One-Cycle learning rate scheduler (lr0=0.01, lrf=0.01) was used. Alternative hyperparameter settings (e.g., different learning rates, batch sizes, and augmentation strategies) were explored. Still, they did not yield improved performance over the defaults, reinforcing the robustness of the original YOLOv5 training configuration.

4.3. Performance Metrics

To thoroughly evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed models, we used key performance metrics that assess both inference speed and detection accuracy. These include Frames Per Second (FPS) for speed evaluation and mean Average Precision (mAP) for accuracy evaluation. Precision and recall were also used to assess detection quality.

4.3.1. Inference Speed

The inference speed was evaluated using Frames Per Second (FPS), reflecting the image throughput per second. Higher FPS values indicate faster inference and better real-time performance, crucial for deployment in autonomous driving systems. FPS is calculated as follows:

Where N = total number of processed images, T = total inference time in seconds.

4.3.2. Detection Accuracy

Detection accuracy was assessed using mean Average Precision (mAP), which evaluates the model’s precision across all object classes in the dataset. Average Precision (AP) for a single class is calculated as the area under the Precision-recall (P-R) curve:

Where = precision as a recall function.

mAP is obtained by averaging the AP scores across all

C classes:

Where C = total number of object classes, = AP for the i-th class.

Higher mAP values indicate better overall detection accuracy across multiple object classes.

4.3.3. Detection Quality Assessment

We used precision and recall metrics to evaluate further detection quality, which provides an idea of the model’s ability to identify positive detections while correctly mitigating false positives and negatives.

where

(True Positives) refers to correct detection,

(False Positives) incorrect detetion, and

(False Negatives) undetected objects. A higher precision value reflects the ability of a model to minimize false positives, while a high recall value indicates improved detection of all relevant objects. Balancing these metrics ensures optimal performance for both accuracy and reliability in real-world autonomous driving scenarios. Combining these evaluation metrics assesses the proposed models’ efficiency, accuracy, and practical feasibility for real-time deployment on edge devices.

4.4. Ablation Study

Object detection models must efficiently extract, refine, and prioritize features while balancing accuracy and computational cost. We conducted an ablation study comparing the Standard C3 block, SE Attention, and ECA Attention to explore how different architectural modifications affect performance. The goal was to understand how replacing C3 with SE or ECA impacts feature importance, computational efficiency, accuracy, and speed. The architectural characteristics of the C3, SE, and ECA modules are described in

Table 2, while their quantitative performance comparisons are detailed in

Table 3 and

Table 4, highlighting the balance between accuracy, inference speed, and computational cost.

4.4.1. Impact on Feature Importance

The Standard C3 block in YOLOv5s architecture processes all channels equally, treating each feature with the same level of importance, which in some scenarios might lead to redundant or less informative features being processed. In contrast, SE and ECA modules prioritize the most relevant features by introducing attention mechanisms. While SE explicitly models channel dependencies using fully connected (FC) layers, ECA applies a lightweight 1D convolution, allowing it to capture local channel interactions efficiently.

4.4.2. Computational Cost Considerations

Replacing C3 with SE attention reduces the number of convolution operations. However, it introduces additional costs from fully connected layers used to model channel dependencies, making SE computationally lighter than C3 but still more expensive than ECA. On the other hand, ECA replaces the FC layers with a more efficient 1D convolution, significantly reducing overhead while maintaining strong feature representation, which makes ECA the most computationally efficient option among the three.

4.4.3. Effect on Accuracy

Since SE and ECA refine feature selection, they both contribute to accuracy improvements over the standard C3 module. SE enhances accuracy by globally analyzing channel dependencies, making it beneficial for detecting large objects or those with distinct characteristics. However, ECA refines attention at a more localized level, improving object recognition in scenarios where subtle local variations matter, making ECA particularly effective in handling complex backgrounds and smaller objects.

4.4.4. Effect on Speed

Inference speed plays a crucial role in real-time object detection tasks, and the standard C3 block exhibits slightly slower performance due to its increased number of convolution operations. SE attention speeds up inference by reducing convolutional complexity, but is slowed down by fully connected layers. ECA achieves the best trade-off, as its 1D convolution operation is significantly lighter than SE’s fully connected layers, making it the fastest option while improving feature representation.

These tables show that ECA offers the most favorable balance among the three modules. It delivers the highest mAP and FPS with reduced computational load, confirming its suitability for real-time edge deployment.

5. Results

The proposed models were evaluated against the YOLOv5 baseline to assess the impact of Squeeze-and-Excitation and Efficient Channel Attention modules on detection accuracy, computational efficiency, and inference speed. The evaluation was conducted using precision (P), recall (R), mean average precision at 50% (mAP@50), mean average precision at 95% (mAP@95), floating-point operations (GFLOPs), parameter count, model size, and inference speed (FPS). A comprehensive comparative analysis of detection performance, computational efficiency, and class-wise detection accuracy is presented in

Table 3,

Table 4, and

Table 5.

5.1. Detection Performance Analysis

Table 3 provides the proposed models’ precision, recall, and mAP scores and the baseline YOLOv5s. The results demonstrate that integrating attention mechanisms in the baseline model impacts detection accuracy, with variations based on the placement of ECA and SE modules.

The following observations can be drawn from

Table 3:

BaseSE-ECA (Vehicles) achieves the highest detection precision (96.7%) and recall (96.2%), demonstrating that attention mechanisms significantly enhance vehicle detection performance.

BaseECA surpasses the baseline model in mAP@50 (90.9%) and mAP@95 (68.9%), indicating improved overall detection accuracy.

BaseECAx2, incorporating dual ECA attention, demonstrates robust detection capabilities with precision (89.1%) and recall (86%), highlighting the effectiveness of multi-layer attention integration.

While BaseSE-ECA achieves the highest precision (91.3%), its lower recall (83.9%) suggests a trade-off between high selectivity and overall detection capability.

These findings indicate that the strategic placement of SE and ECA modules significantly influences model performance, with SE improving large-object detection and ECA enhancing small-object recognition.

While the proposed models performed well on KITTI, their performance declined on BDD-100K, as in

Table 6, particularly in scenes with heavy occlusions, poor lighting, and motion blur. That indicates that while ECA and SE improve feature selection, additional strategies like temporal feature integration or multi-frame processing may be required to address such challenges.

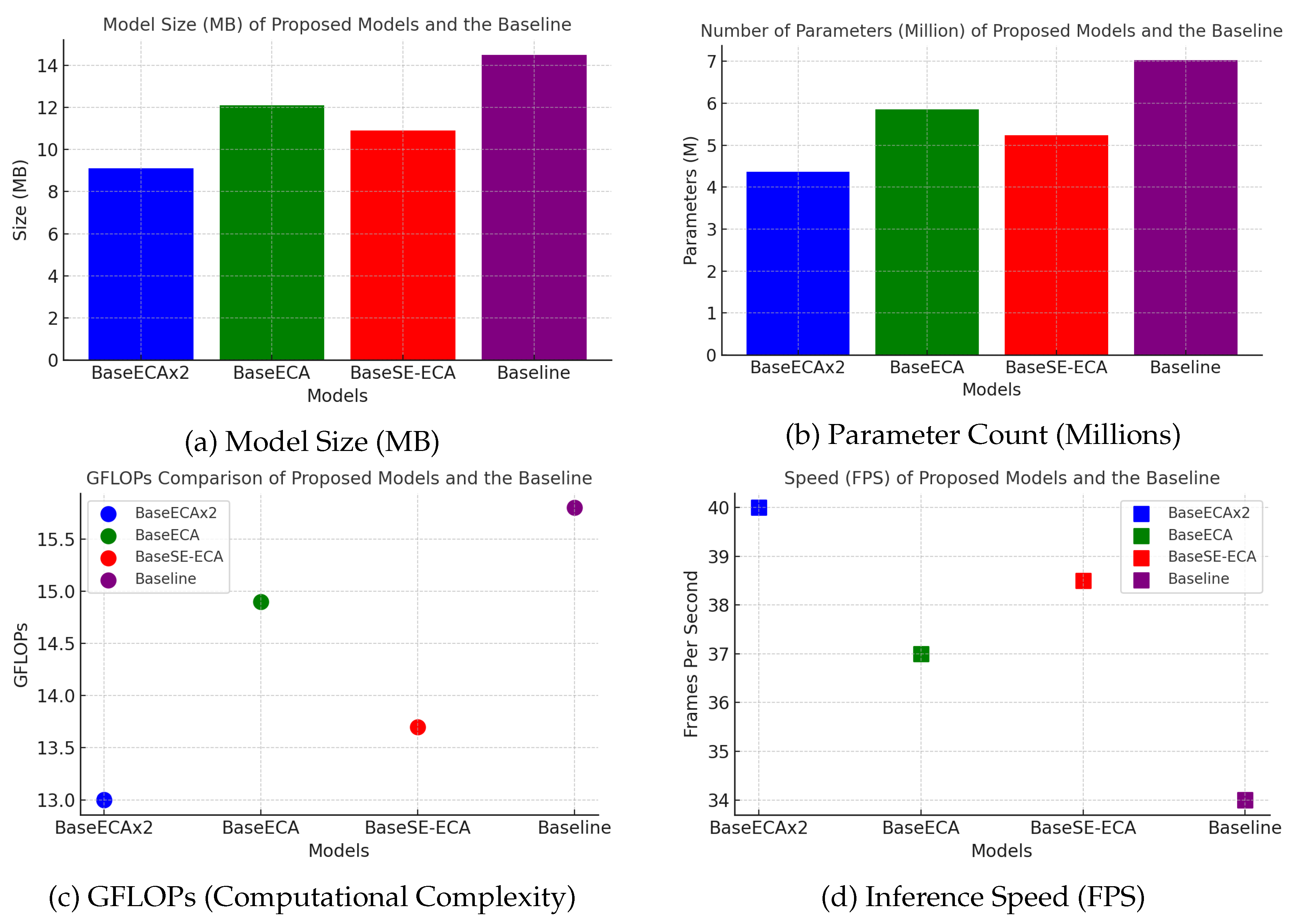

5.2. Computational Efficiency and Model Complexity

Table 4 shows the comparative analysis of GFLOPs, parameter count, model size, and inference speed (FPS). The results show the computational benefits of integrating ECA and SE modules, achieving an optimal trade-off between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. The key findings are :

BaseSE-ECA (Vehicles) achieves a compact model size (9.1 MB) with a moderate computational complexity of 13.7 GFLOPs, making it highly efficient for edge-device deployment.

BaseECAx2 exhibits the lowest GFLOPs (13.0) while maintaining fewer parameters (43.7M), confirming that multi-layer ECA integration reduces computational overhead.

BaseECA, despite enhancing feature representation, slightly increases computational complexity, requiring 14.9 GFLOPs and a model size of 12.1 MB.

The baseline YOLOv5s model has the highest GFLOPs (15.8) and parameter count (70M) while achieving the lowest FPS (34), reinforcing the efficiency gains of the proposed models.

These results confirm that ECA-based modifications effectively reduce model complexity, improving computational efficiency for real-time edge applications;

Figure 5 shows the proposed models with respect to model size, number of parameters, computational cost, and speed.

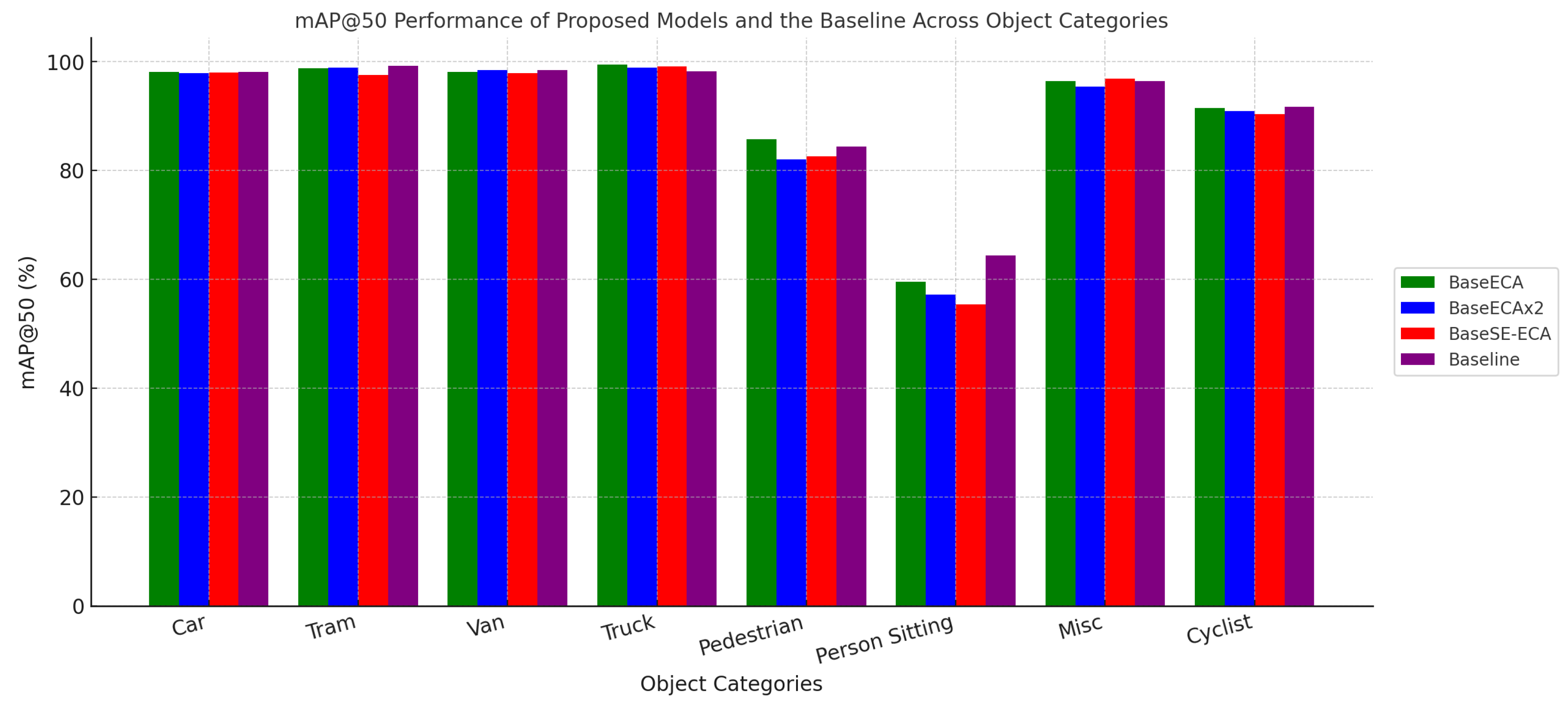

5.3. Class-Wise Detection Performance

In

Table 5, the results show different object categories measured on the mAP@50, illustrating the strengths of each model in detecting specific classes.

BaseECA achieves the highest pedestrian detection accuracy (85.7%) and performs exceptionally well for cyclists (91.4%), confirming that ECA enhances small-object detection.

BaseSE-ECA (Vehicles Only) excels in vehicle detection, achieving 98.8% mAP for vans and 98.4% for trucks, reinforcing SE’s strength in large-object recognition.

BaseECAx2 maintains strong multi-class performance, demonstrating a balanced detection capability across different object categories.

These findings demonstrated that attention-based modifications improve class-specific detection accuracy, particularly for human and vehicle detection, which are critical for autonomous driving applications.

Figure 6 shows the performance of each model on all classes.

5.4. Discussion

Deploying deep learning-based object detectors on edge devices remains a significant challenge due to strict constraints on memory, processing power, and energy consumption. To address this, we proposed lightweight variants of YOLOv5 by integrating Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) and Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) modules, aiming to enhance feature extraction with minimal computational overhead. Our findings demonstrate an effective balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. For example, the BaseECAx2 model achieved a mAP@50 of 90.0% with only 4.37M parameters and 13.0 GFLOPs, outperforming traditional models like YOLOv3 and RetinaNet regarding resource efficiency. Additionally, the BaseSE-ECA model achieved high precision (91.3%) and robust multi-class detection performance, as shown in

Table 7 and

Table 6. Unlike previous studies such as CAE-YOLOv5 [

29] and CRL-YOLOv5 [

31], which apply attention mechanisms exclusively within the backbone, our study introduces a dual-placement strategy. Specifically, BaseECAx2 applies ECA modules in both the backbone and detection head, while BaseSE-ECA combines SE in the backbone with ECA in the head. Our models achieve up to a

reduction in computational cost compared to recent attention-enhanced models such as SNCE-YOLO (35 GFLOPs) and YOLOv4-5D (103 GFLOPs) while maintaining comparable or superior accuracy. Notably, the smallest model size is just 9.1 MB, with real-time inference speeds, making the designs well-suited for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. We also compared our models to YOLOv8-Lite [

22], a recent low-resource design. While YOLOv8-Lite achieved 76.62% mAP@50 on the KITTI dataset using 4.8M parameters and 8.95 GFLOPs, our BaseECAx2 achieved a substantially higher mAP@50 of 90.0% with a similar number of parameters and only moderately higher complexity, demonstrating a superior accuracy-efficiency trade-off for practical edge applications. On the BDD-100K dataset, which includes more challenging scenarios such as occlusion, low light, and motion blur, our models experienced a moderate drop in performance compared to KITTI; this suggests that while channel-wise attention mechanisms (SE, ECA) improve spatial feature learning, they are less effective in capturing spatiotemporal variations inherent in real-world driving conditions. Compared with other recent lightweight detectors, YOLOv11n [

48] achieved a mAP@50 of 88.8% using 2.58M parameters and 6.3 GFLOPs. Our BaseECAx2 improved upon this by achieving 90.0% mAP@50 (+1.2%), with higher precision (89.1% vs. 85.2%) and a competitive inference speed of 40.0 FPS. While slightly larger, BaseECAx2 offers better detection reliability without sacrificing real-time performance. YOLOv12nYOLOv11n [

49], on the other hand, achieved a higher mAP@50 of 91.6% with 2.56M parameters and 6.3 GFLOPs. However, it exhibited lower precision (87.6%) and slower inference (38.3 FPS) compared to our BaseECAx2 and BaseSE-ECA models. These results suggest that although YOLOv12n performs well in overall detection and recall, our models offer superior precision and faster execution—critical traits in safety-critical, real-time edge AI applications. Future work will explore integrating spatiotemporal attention mechanisms, multi-frame feature aggregation, and generative learning enhancements to improve detection robustness under dynamic and challenging conditions, such as those encountered in autonomous driving. In summary, the proposed architectural enhancements to YOLOv5 introduce effective and novel attention configurations that significantly improve the trade-off between accuracy, speed, and compactness. These contributions make our models practical and deployable solutions for real-time edge AI applications, including autonomous vehicles, intelligent surveillance, and embedded vision systems.

Figure 7.

Detection result of BaseECAx2 on the KITTI dataset under various conditions.

Figure 7.

Detection result of BaseECAx2 on the KITTI dataset under various conditions.

Figure 8.

Detection result of BaseECAx2 on the BDD-100K dataset under various conditions.

Figure 8.

Detection result of BaseECAx2 on the BDD-100K dataset under various conditions.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we developed lightweight object detection models for real-time use on edge devices, such as those found in autonomous vehicles. Although the original YOLOv5 generally performs well, its high computational cost and large model size make it less suitable for environments with limited resources. To address this, we introduced three optimized variants by integrating Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) and Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) modules at different levels of the YOLOv5 architecture. Experimental evaluations on the KITTI dataset demonstrated that the BaseECAx2 model achieves the best trade-off between detection accuracy and efficiency—achieving only 13 GFLOPs, a compact model size of 9.1 MB, and a fast inference speed of 27 ms—making it highly suitable for real-time edge deployment. For applications prioritizing detection accuracy, such as vehicle-specific recognition in autonomous systems, the BaseSE-ECA model delivered the highest performance, achieving 96.69% precision, 96.20% recall, and 98.40% mAP@50. Despite these promising results on KITTI, performance degraded on the more complex BDD-100K dataset due to challenges such as occlusion, low lighting, and motion blur. The results emphasize the need for further architectural enhancements to improve robustness under real-world driving conditions. Future work will explore integrating spatiotemporal modeling techniques, including temporal feature fusion, multi-frame aggregation, dynamic input adaptation, noise-resilient attention mechanisms, and generative learning methods. This work introduces a practical and scalable direction for building efficient, high-performing object detectors using lightweight attention modules. The study demonstrates that improvements can effectively bridge the gap between computational efficiency and real-time performance, supporting the advancement of AI-driven perception in autonomous vehicles and other embedded vision applications.

Author Contributions

M.A.A.A. was responsible for conceptualization, methodology design, and original draft preparation. J.R.T. contributed to manuscript review and editing and provided supervision. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DNN |

Deep Neural Network |

| IoU |

Intersection over Union |

| mAP |

mean Average Precision |

| FPS |

Frames Per Second |

| GFLOPs |

Giga Floating Point Operations |

| V2X |

Vehicle-to-Everything |

| KITTI |

Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and Toyota Technological Institute |

| BDD100K |

Berkeley DeepDrive 100K |

| YOLO |

You Only Look Once |

| SE |

Squeeze-and-Excitation |

| ECA |

Efficient Channel Attention |

| CBAM |

Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| CA |

Coordinate Attention |

| RPN |

Region Proposal Network |

| FPN |

Feature Pyramid Network |

| NMS |

Non-Maximum Suppression |

| UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| COCO |

Common Objects in Context |

References

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, A.; Van Chien, T. (Eds.) The Intersection of 6G, AI/Machine Learning, and Embedded Systems: Pioneering Intelligent Wireless Technologies, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Hong, A.; Tang, H.; Tong, G. FQDNet: A Fusion-Enhanced Quad-Head Network for RGB-Infrared Object Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Li, H. Real-Time Pedestrian and Vehicle Detection for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Changshu, China, 26–30 June 2018; pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, J.; Li, S.; Shan, Y. SNCE-YOLO: An Improved Target Detection Algorithm in Complex Road Scenes. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 152138–152151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chaw, J.K.; Goh, S.K.; Shi, L.; Tin, T.T.; Huang, N.; Gan, H.-S. Super-Resolution GAN and Global Aware Object Detection System for Vehicle Detection in Complex Traffic Environments. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 113442–113462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, W.; Ben Rhaiem, O.; Faiedh, H.; Souani, C. Optimized Deep Learning for Pedestrian Safety in Autonomous Vehicles. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvao, L.G.; Abbod, M.; Kalganova, T.; Palade, V.; Huda, M.N. Pedestrian and Vehicle Detection in Autonomous Vehicle Perception Systems—A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 7267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karangwa, J.; Liu, J.; Zeng, Z. Vehicle Detection for Autonomous Driving: A Review of Algorithms and Datasets. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 11568–11594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M. YOLOv1 to v8: Unveiling Each Variant–A Comprehensive Review of YOLO. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 42816–42833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.03151. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.01507. [Google Scholar]

- Sarda, A.; Dixit, S.; Bhan, A. Object Detection for Autonomous Driving Using YOLO (You Only Look Once) Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 Third International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks (ICICV), Tirunelveli, India, 4–6 February 2021; pp. 1370–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wen, S.; Wang, D.; Meng, J.; Mu, J.; Irampaye, R. MobileYOLO: Real-Time Object Detection Algorithm in Autonomous Driving Scenarios. Sensors 2022, 22, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afdhal, A.; Saddami, K.; Arief, M.; Sugiarto, S.; Fuadi, Z.; Nasaruddin, N. MXT-YOLOv7t: An Efficient Real-Time Object Detection for Autonomous Driving in Mixed Traffic Environments. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 178566–178585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Luan, T.; Gao, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Sotelo, M.A.; Li, Z. YOLOv4-5D: An Effective and Efficient Object Detector for Autonomous Driving. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, C.; Peng, Y.; Ru, H. MCS-YOLO: A Multiscale Object Detection Method for Autonomous Driving Road Environment Recognition. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 22342–22354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Wu, H.; Zhen, L.; Hua, Q.; Garg, S.; Kaddoum, G.; Hassan, M.M.; Yu, K. Edge YOLO: Real-Time Intelligent Object Detection System Based on Edge-Cloud Cooperation in Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 25345–25360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Xu, A.; Ye, Z.; Zhou, W.; Cai, T. Object Detection Based on Lightweight YOLOX for Autonomous Driving. Sensors 2023, 23, 7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Shanwei, L.; Mingming, X.; Jianhua, W.; Nazir, S.; Islam, Q.U.; Dang, K.B. SwinYOLOv7: Robust Ship Detection in Complex Synthetic Aperture Radar Images. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 160, 111704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Fan, X. YOLOv8-Lite: A Lightweight Object Detection Model for Real-Time Autonomous Driving Systems. ICCK Trans. Emerg. Top. Artif. Intell. 2024, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Wang, W. SCCA-YOLO: A Spatial and Channel Collaborative Attention Enhanced YOLO Network for Highway Autonomous Driving Perception System. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-Time Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2304.08069. [Google Scholar]

- Kadiyapu, D.C.M.; Mangali, V.S.; Thummuru, J.R.; Sattula, S.; Annapureddy, S.R.; Arunkumar, M.S. Improving the Autonomous Vehicle Vision with Synthetic Data Using Gen AI. In Proceedings of the 2025 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT), Tiruchirappalli, India, 6–7 March 2025; pp. 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Kumar, G.P.; Prasad, P.; Kumar, D.; Jain, S.; Chopra, J. Synergizing Generative Intelligence: Advancements in Artificial Intelligence for Intelligent Vehicle Systems and Vehicular Networks. Iconic Res. Eng. J. 2023, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, M. GenCoder: A Generative AI-Based Adaptive Intra-Vehicle Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 150651–150663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yang, W.; Xiong, Z.; Xing, C.; Tafazolli, R.; Quek, T.Q.S.; Debbah, M. Generative AI-Enhanced Multi-Modal Semantic Communication in Internet of Vehicles: System Design and Methodologies. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.15642. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wei, H.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, W.; Yin, H. CAE-YOLOv5: A Vehicle Target Detection Algorithm Based on Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Automation Congress (CAC), Wuhan, China, 24–26 November 2023; pp. 6893–6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Z. A High-Precision Vehicle Detection and Tracking Method Based on the Attention Mechanism. Sensors 2023, 23, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Men, S.; Bai, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, L. Improved Small Object Detection Algorithm CRL-YOLOv5. Sensors 2024, 24, 6437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Tong, Y.; Qiao, H.; Li, M.; Tong, J.; Liang, B. Fast and Accurate Object Detector for Autonomous Driving Based on Improved YOLOv5. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Dongye, C.; Jia, X. The Research on Traffic Sign Recognition Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv5 Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Consumer Electronics and Computer Engineering (ICCECE), Guangzhou, China, 6–8 January 2023; pp. 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, M. YOLOv3-MT: A YOLOv3 Using Multi-Target Tracking for Vehicle Visual Detection. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 2070–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Guo, D.; Shao, C.; Zhao, K.; Sun, M.; Shuai, H. SatDetX-YOLO: A More Accurate Method for Vehicle Target Detection in Satellite Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 46024–46041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.A.A.; Tapamo, J.R. Survey on Image-Based Vehicle Detection Methods. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Bourdev, L.; Girshick, R.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Zitnick, C.L.; Dollár, P. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1405.0312. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G. Ultralytics YOLOv5, Version 7.0. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision Meets Robotics: The KITTI Dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Xian, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Liao, M.; Madhavan, V.; Darrell, T. BDD100K: A Diverse Driving Video Database with Scalable Annotation Tooling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.04687. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.; Bao, H.; Pan, W.; Pan, F. ALODAD: An Anchor-Free Lightweight Object Detector for Autonomous Driving. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 40701–40714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ji, Z.; Qu, X.; Zhou, R.; Cao, D. Cross-Domain Object Detection for Autonomous Driving: A Stepwise Domain Adaptative YOLO Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2022, 7, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pang, C.; Dong, C.; Zeng, X. R-YOLOv5: A Lightweight Rotational Object Detection Algorithm for Real-Time Detection of Vehicles in Dense Scenes. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 61546–61559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almujally, N.A.; Qureshi, A.M.; Alazeb, A.; Rahman, H.; Sadiq, T.; Alonazi, M.; Algarni, A.; Jalal, A. A Novel Framework for Vehicle Detection and Tracking in Night Ware Surveillance Systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 88075–88085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammul, M.; Li, X. Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning-Based Tiny Object Detection: Challenges, Strategies, and Future Directions. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2025, 67, 3825–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO11, Version 11.0.0. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics.

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).