1. Introduction

Neuroautoimmune conditions of the CNS including Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders (NMOSD), Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD), and Autoimmune Encephalitis/Encephalomyelitis (AE), are characterized by demyelination and/or axonal degeneration, resulting from the activation of inflammatory responses against CNS antigens [

1]. Historically, potent corticosteroids and other systemic immunosuppressants were used. This approach exposed patients to increased toxicity and an elevated risk for infections and development of malignancies, from the chronic and extensive immune compromise. The development of DMTs shifted this paradigm by enabling for the selective targeting of immune mediators, without broad immunosuppression. Such DMTs include IFN-beta, and Glatiramer Acetate introduced in the 1990s [

2,

3], and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), later, in the 2000s [

4]. The three main mAb targets are: (1) pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. Tocilizumab, anti-IL6); (2) integrins, which facilitate lymphocyte entry into the CNS via the blood–brain barrier (BBB) (e.g. Natalizumab); and (3) immune cell populations, primarily B-cells (e.g. Rituximab, anti-CD20). These immunotherapeutic agents have been used for decades in adult patient cohorts and are also promising targeted immunotherapies for pediatric populations [

4,

5]. Although, various unmet needs remained, regarding the immunological frame of cellular targeting and antigen specificity.

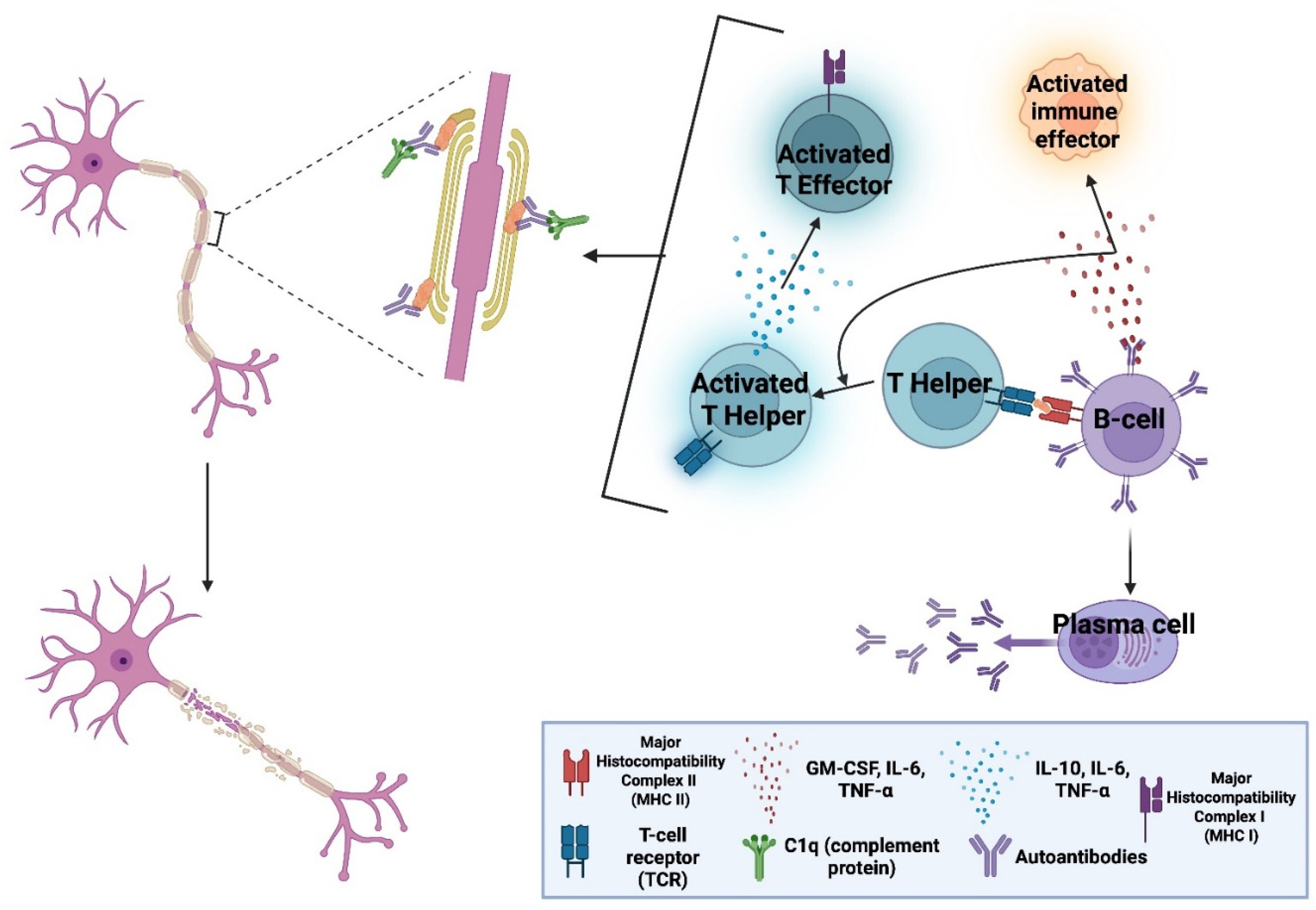

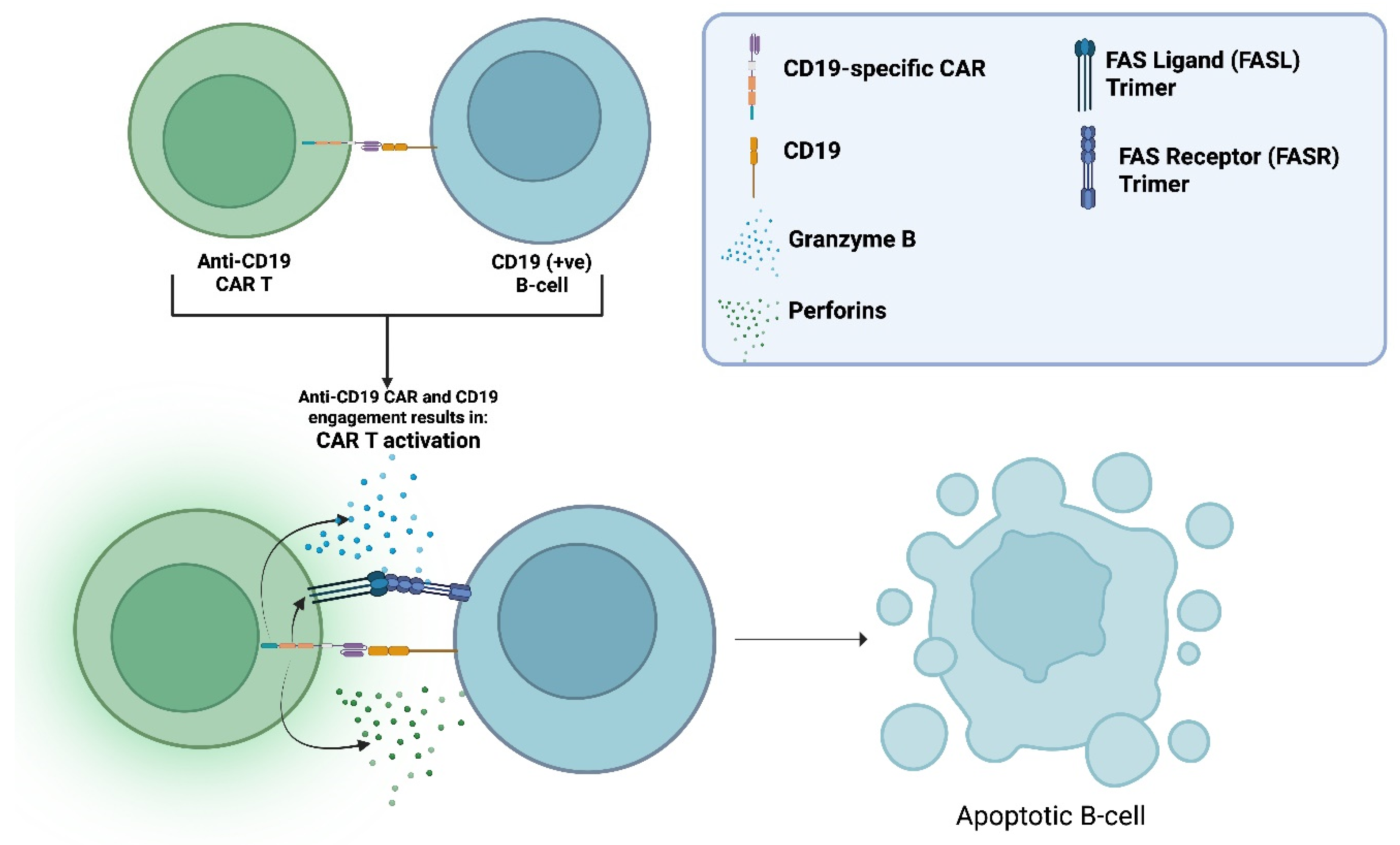

The CAR is an engineered transmembrane receptor protein formed by linking an antigen-recognition domain to T-cell activating signalling motifs (Figure 3). CAR T-cells are human T-cells, modified to express these receptors, to create a “living drug” that binds and eliminates cellular targets in an antigen-specific manner, potenitally covering the previous mentioned immunological unmet needs.

All currently approved CAR T-cell therapies are used in B-cell malignancies, targeting either CD19 or B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) (+ve) B-cells. Long-term follow-up data demonstrate an extensive and durable B-cell-depleting capacity [

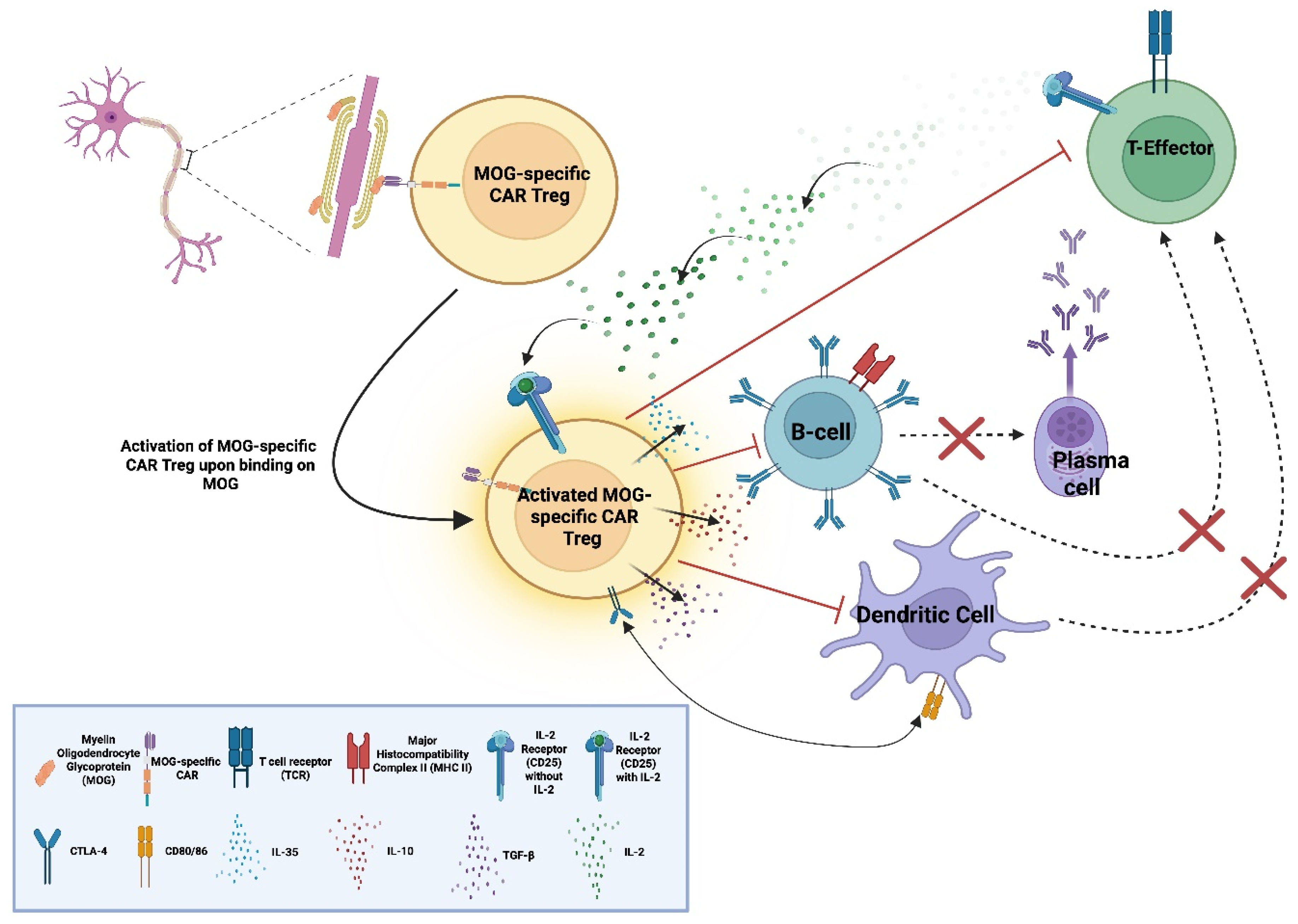

6]. B-cells also have a consistent and substantial contribution to the pathophysiology of all major CNS autoimmune conditions. Their involvement includes promotion of inflammation with cytokine and chemokine secretion, autoantibody production and antigen presentation with subsequent activation of autoreactive T-cells and other effectors (See

Figure 1). As a result, mAb-based DMTs targeting B-cells, remain central for disease management [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Despite their effectiveness, current DMTs do not benefit all patients. mAb-based therapies require repeated dosing to achieve and maintain disease remission due to their finite half-life and the eventual reconstitution of the immune populations targeted. Their limited biodistribution constitutes them unable to eliminate CNS-residing autoreactive cells, especially ones that reside within tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs).

CAR T-cells offer distinct advantages. As a “living therapy,” they persist and continue to express the CAR, enabling for a prolonged elimination their target, potentially serving as a one-time treatment. Successful deep B-cell depletion may induce a curative “immune reset” if: (1) autoreactive clones do not re-emerge, (2) the eliminated cells are central mediators in the pathophysiology of the disease, (3) and no genetic drivers are responsible in autoreactivity. Long-term observations from CAR T-cell use in oncology include a profound B-cell depletion, deep tissue penetration, and the flexibility to target different cell types/subtypes. These characteristics, collectively support CAR T-cell investigation in CNS autoimmune conditions with 16 clinical trials currently active or planned (See

Table 1).

However, CAR T-cell therapies are associated with acute and delayed toxicities, high manufacturing costs, and logistical challenges, limiting their use in non-aggressive/non-life-threatening cases. Continued development of safety-mitigation strategies and cost-reduction approaches will be essential to improve scalability and enable broader application in CNS autoimmunity.

2. The CAR and Its Evolution, “Hijacking” Cytotoxic T-Cell Capacities to Eliminate Cellular Targets

2.1. The Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)

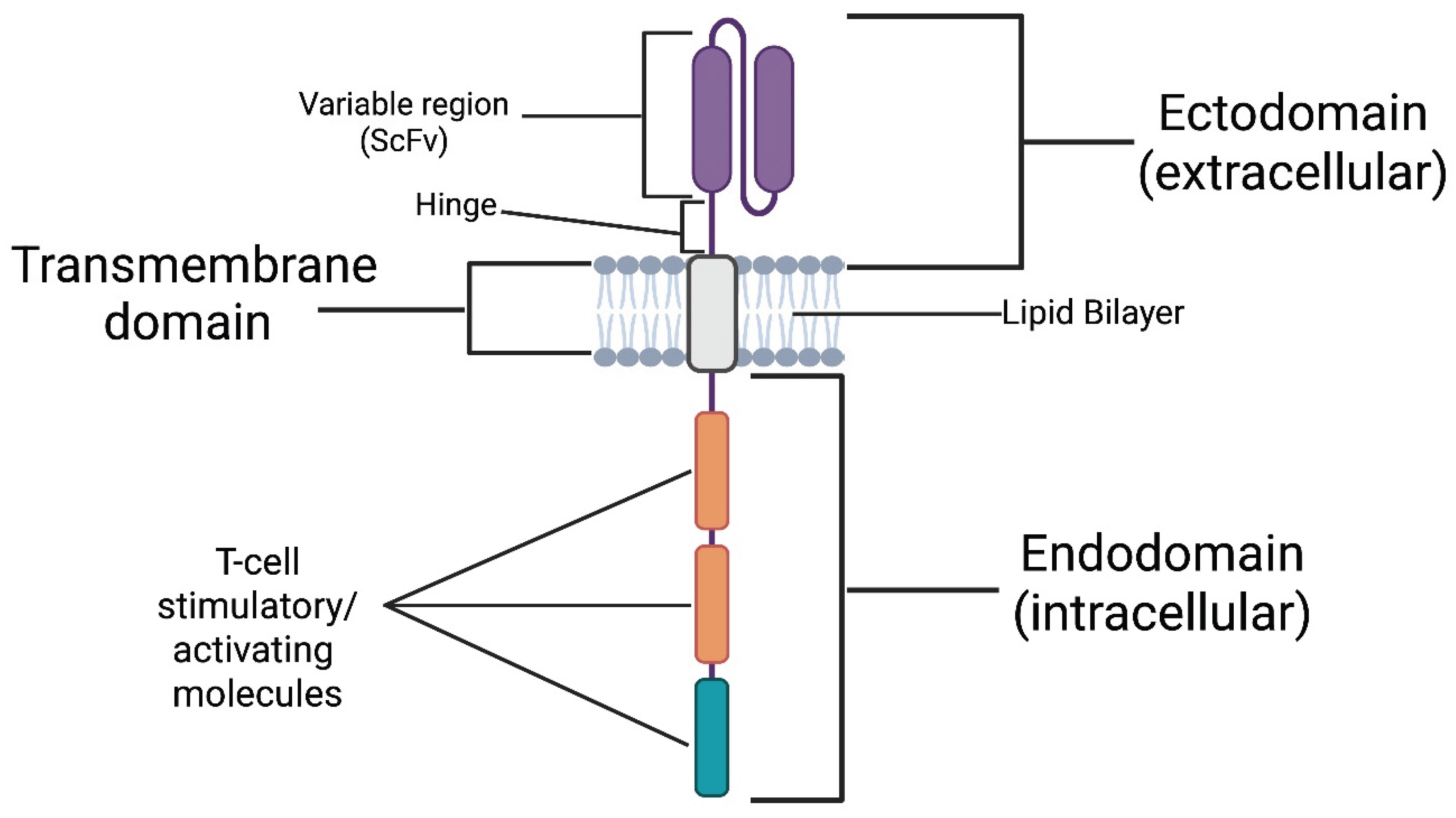

The CAR can be divided into three major domains [

12]: the (1) ectodomain, the (2) transmembrane domain, and the (3) endodomain (See

Figure 2). The ectodomain is the extracellular portion of the receptor. It includes a variable-binding region with affinity and specificity for an antigen expressed on a cellular target. The variable-binding region is a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from the heavy and light chains of an antibody with affinity and specificity for the target antigen. The scFv is connected to a hinge region, which bridges it to the transmembrane domain. The hinge increases binding capacity at the immunological synapse by providing flexibility. This flexibility allows the binding region to adopt different spatial orientations to facilitate a more efficient scFv-antigen interaction [

13]. Next comes the transmembrane domain, which, as the name implies, spans the lipid bilayer and anchors the receptor in place. Finally, the endodomain, located intracellularly, translates extracellular antigen recognition into signalling cascades, activating the CAR T-cell, resulting in the elimination of the cellular target [

14]. The activated CAR T-cell eliminates its target by the secretion of perforins and Granzyme B, and the upregulation of its Fas ligand (FasL). As it is well known, perforins open pores on the target’s membrane to fascilitate Granzyme B entry in the targets cytoplasm which in-turn activates intrinsic apoptotic pathways. FasL binds Fas receptor (FasR) on the target which activates its extrinsic apoptotic pathways (See

Figure 3)

Physiologically, the activation of T-cells requires the T-cell receptor (TCR) to recognise non-self antigens presented by self-major-histocompatibility-complex (MHC) molecules on the target’s cell surface and to receive co-stimulatory signals from secondary receptors for a successful T-cell activation, in the context of immunological synapsis. A breakthrough introduced by CAR technology is that its intracellular signalling motifs can exert sufficient activatory-signalling independently of co-stimulation, while its ectodomain can recognise antigens without the need for them to be processed and presented through MHC molecules. This innovation renders CAR T-cell activation independent of both MHC- and co-stimulatory signals, effectively allowing us to “hijack” the major physiological checkpoints that typically regulate a T-cell-mediated cytotoxic response. However, this characteristic has also led to them being described as “biological serial killers” [

15] owing to their potentially aggressive behaviour.

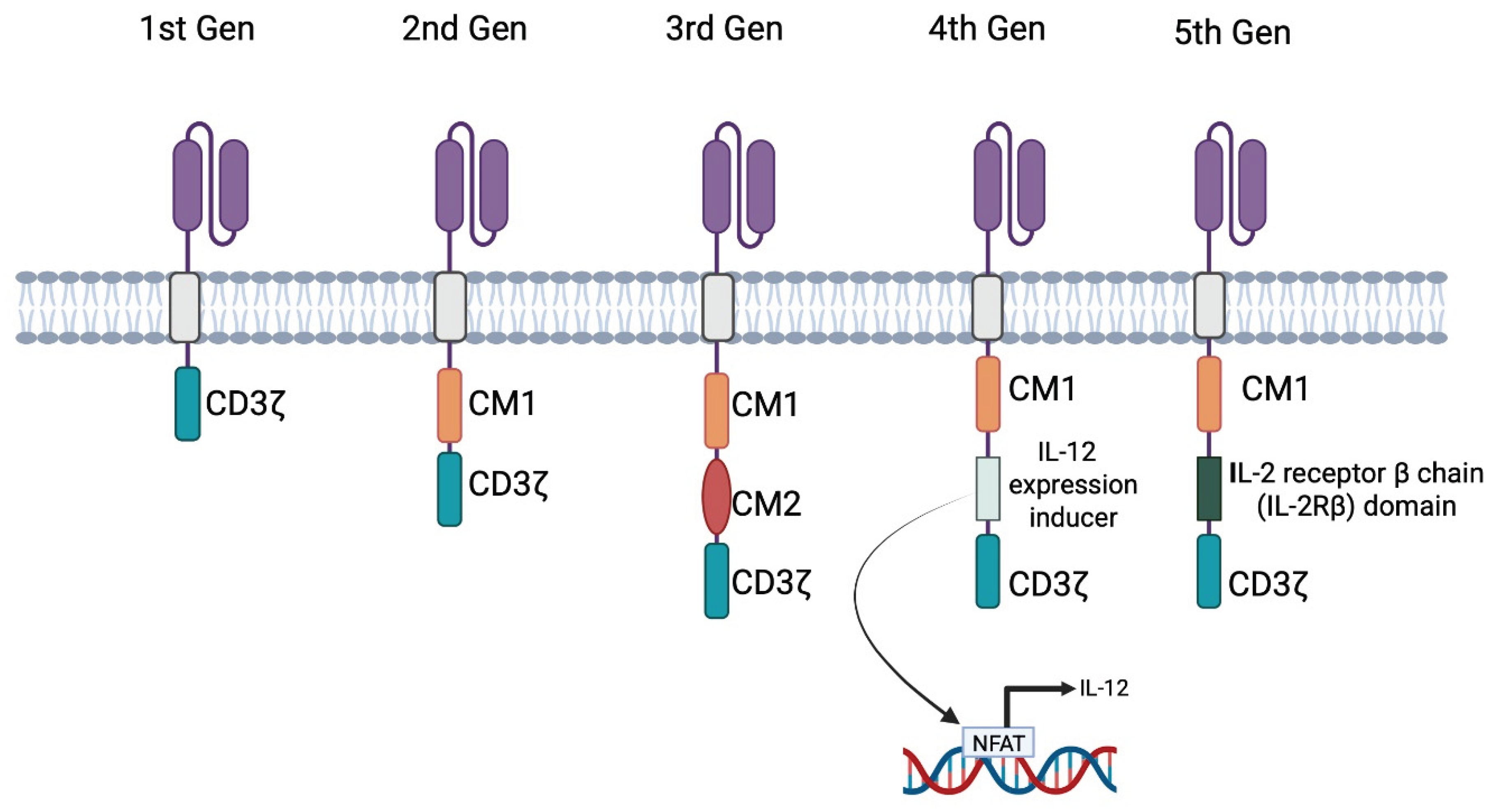

2.2. The History and the Different Generations of CARs

In 1988, Rosenberg et al. [

17] investigated the collection and ex vivo expansion of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), which were subsequently reinfused into patients with metastatic melanoma. In this cohort of 20 patients, the study demonstrated strong evidence of tumour regression. The success of TIL therapy paved the way for the development of CAR T-cell therapy. The initial CAR T-cells were genetically engineered to express synthetic receptors, to recognise and target tumour-associated antigens. Since the first CAR design, different generations of this molecule have been developed. The key differences between generations involve modifications of the intracellular signalling domain. All CAR generations include CD3ζ which is derived from the native TCR. Different generations include additional signalling regions also known as co-stimulatory molecules (CMs). CMs modulate the intensity and products of CAR T-cell activation.

2.2.1. 1st Generation

Eshhar et al. [

18] introduced the first-generation chimeric antigen receptors in 1993. First-generation CARs synthesised by fusing scFvs to the CD3ζ signalling-domain of the T-cell receptor. As first-generation CARs lacked CMs, limited clinical efficacy was observed, with CARs failing to adequately activate the cytotoxic mechanisms of the T-cell.

2.2.2. 2nd Generation

Second-generation CARs included an additional intracellular CM typically derived from molecules such as CD28 or 4-1BB (CD137), on top of CD3ζ. The additional CM improved T-cell activation, proliferation, persistence, and cytokine secretion upon antigen engagement. This concept was first demonstrated by Finney et al. [

19] with a CD28 as the additional CM and later by Milone et al. [

20] with CD137.

Maher et al. [

21] showed that 2

nd generation prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) CAR T-cells, incorporating both TCRζ and CD28, could effectively eliminate PSMA-expressing tumour cells.

2.2.3. 3rd to 5th Generation

The third generation of CARs incorporates more than one CM alongside CD3ζ such as CD28, CD137 (4-1BB), CD134 (OX-40), NKG2D, CD27, TLR2, or ICOS. Ramos et al. [

22] demonstrated that third-generation CARs with two CMs persist longer and expand more compared to second-generation CARs with one CM, although they may undergo faster exhaustion due to overstimulation [

23]. Exhaustion refers to cells being still alive but with a reduced cytotoxic capacity.

The fourth generation, also known as T-cells Redirected for Universal Cytokine-mediated Killing (TRUCKs), incorporates an Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells (NFAT)-responsive promoter. Upon antigen encounter, NFAT translocates to the nucleus and induces transcription of additional immune-activating cytokines such as IL-12. These CARs typically include one CM and CD3ζ [

24,

25].

The fifth generation includes an interleukin-2 receptor subunit beta (IL2RB) on top of CD3ζ and a CM. IL2RB utilizes the JAK-STAT pathway to promote cell proliferation and prevent terminal differentiation, overall aiming for prolonged activity of the CAR T [

26].

Figure 4.

Schematic of the five generations of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), varying in their intracellular/signalling domain. The 1st generation includes only the CD3ζ signalling domain (homologous to the native T-cell receptor); the 2nd generation adds a single co-stimulatory motif (CM1); the 3rd generation incorporates two co-stimulatory motifs (CM1 and CM2); the 4th generation known as T-cells Redirected for Universal Cytokine-mediated Killing (TRUCKs) introduces an IL-12 expression inducer for enhanced cytokine release via Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells (NFAT) transcription; and the 5th generation includes an IL-2 receptor β chain (IL-2Rβ) domain to activate the JAK-STAT pathway promoting activation and survival [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

"Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 4.

Schematic of the five generations of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), varying in their intracellular/signalling domain. The 1st generation includes only the CD3ζ signalling domain (homologous to the native T-cell receptor); the 2nd generation adds a single co-stimulatory motif (CM1); the 3rd generation incorporates two co-stimulatory motifs (CM1 and CM2); the 4th generation known as T-cells Redirected for Universal Cytokine-mediated Killing (TRUCKs) introduces an IL-12 expression inducer for enhanced cytokine release via Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells (NFAT) transcription; and the 5th generation includes an IL-2 receptor β chain (IL-2Rβ) domain to activate the JAK-STAT pathway promoting activation and survival [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

"Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

3. From mAbs to CAR T-Cells: Overcoming Immune-Access Limitations of mAbs and Compartmentalisation Barriers in CNS Autoimmunity

Anti-B-cell mAbs, a revolutionary DMT, introduced the ability to selectively deplete immune-cells based on the expression of surface markers such as CD20 on B-cells, sparing more unrelated/healthy cell populations. This marked a pivotal shift from earlier broad-acting treatments. mAbs though cannot autonomously kill the cells they bind but require the aid of other immune effectors. When mAbs bind their cellular antigen, they opsonise “tag” the cell for elimination. Opsonised cells are eliminated via three mechanisms [

27]: (1) antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), (2) antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) and (3) complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). ADCC involves natural killer (NK) cells, neutrophils (Neu), and/or macrophages (MΦ) that secrete cytotoxic granules to eliminate their targets. ADCP is largely mediated by MΦs, which phagocytose their targets. CDC eliminates opsonised cells when circulating complement proteins recognise a bound antibody and trigger cascades that recruit additional complement proteins to form a membrane-attack-complex (MAC), which forms a hole and kills the opsonised cell. In contrast, CAR T-cells are entirely self-sufficient.

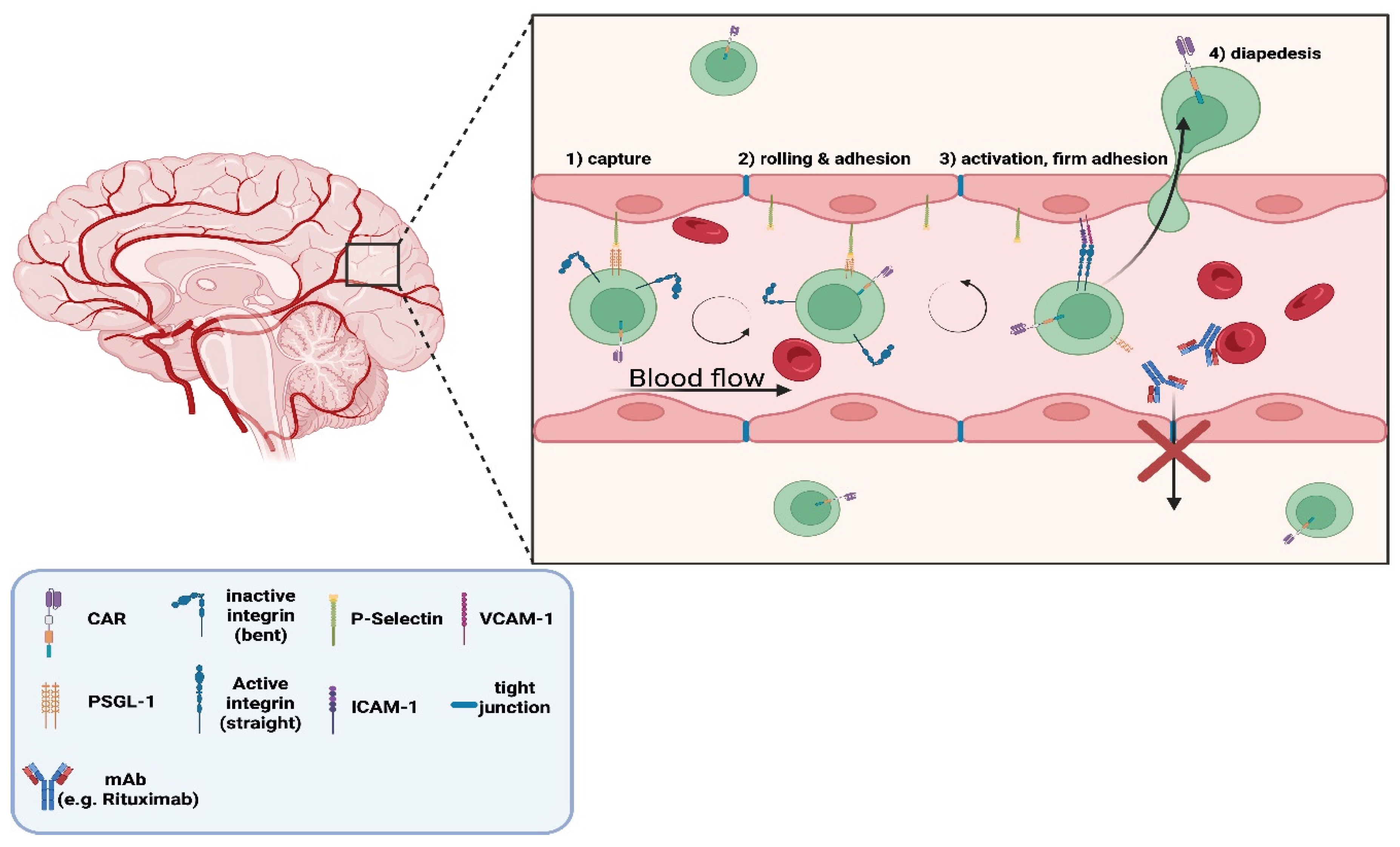

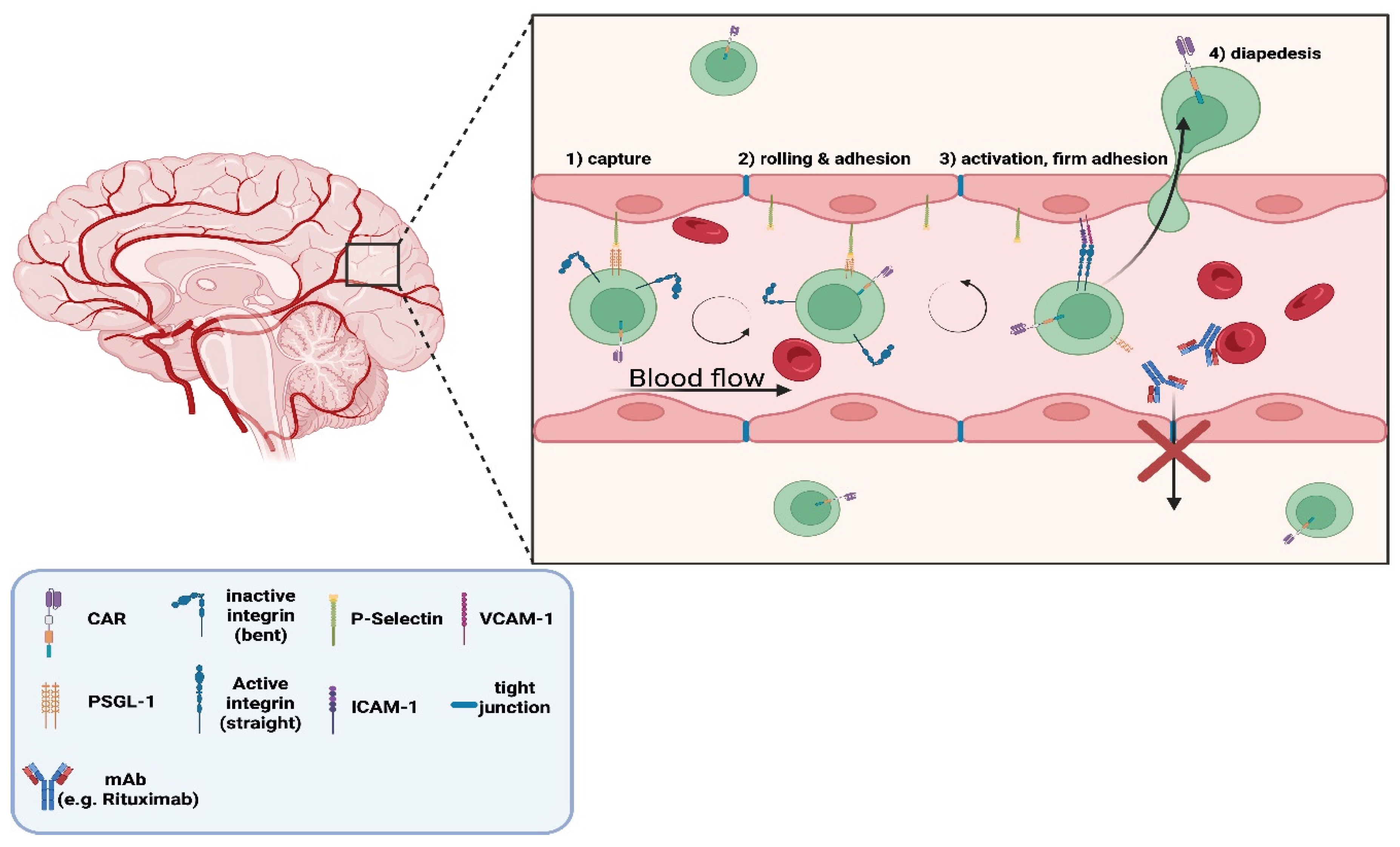

A major limitation of mAb-based DMTs aiming to deplete autoreactive B-cell populations lies in their restricted biodistribution, particularly within isolated/protected compartments. Such compartments include the CNS, due to the BBB filtration. A study reported that Rituximab levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were under 1% of corresponding serum concentrations [

28]. Furthermore, the accessory immune effectors required for mAb-mediated cytotoxicity previously discussed, must also access the CNS to exert their functions, making their biodistribution an additional limiting factor for successful target depletion.

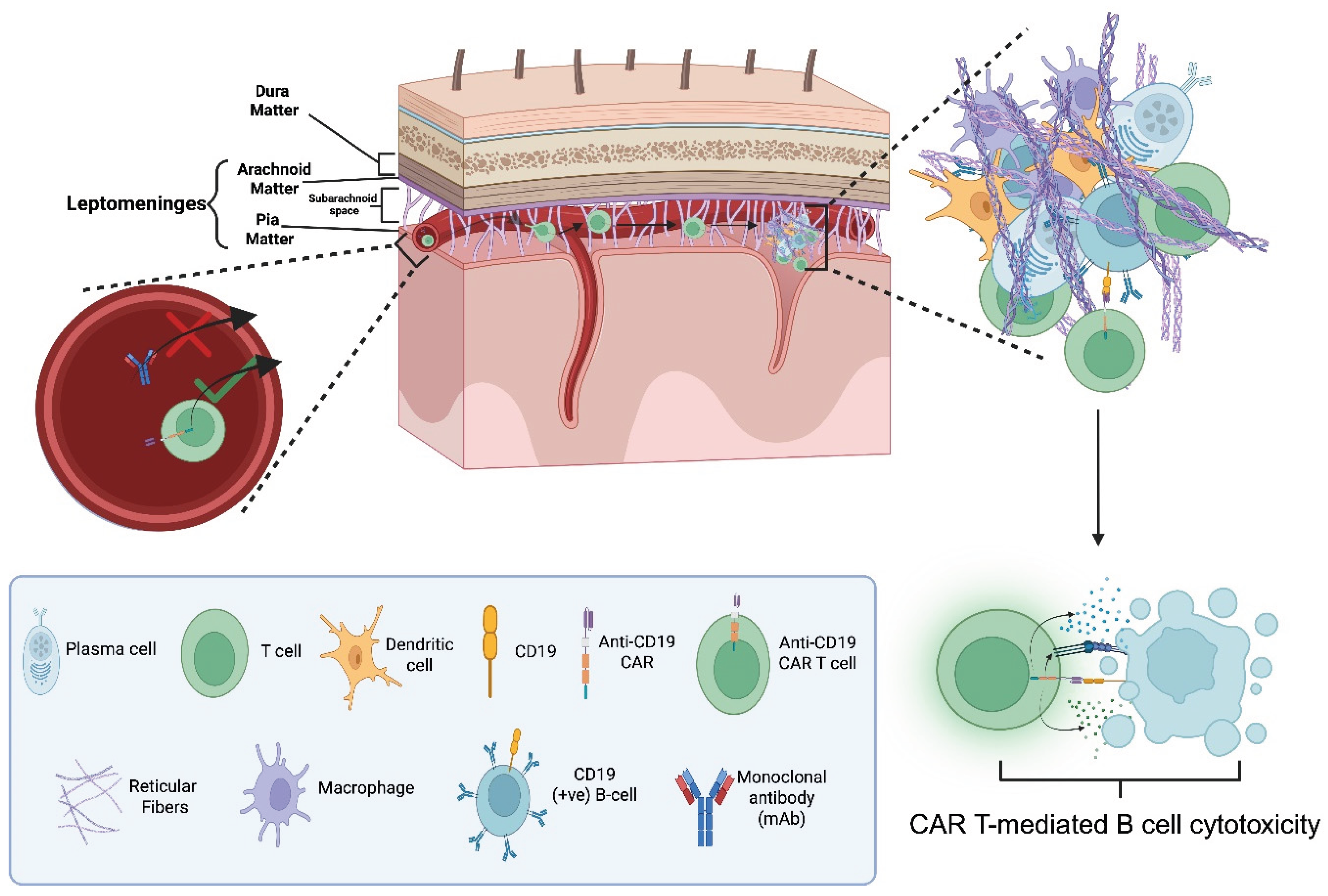

Compartmentalisation of autoreactive cells is a common and sometimes crucial condition for the manifestation and maintenance of certain CNS autoimmune pathologies. The presence of CSF-restricted oligoclonal bands (OCBs) from intrathecal autoantibody production, is among the most reliable diagnostic features distinguishing MS from NMOSD, MOGAD, and AE [

29]. The consistent absence of OCBs in the serum underscores the importance of CNS-resident immune populations in the progression and maintenance of MS pathology and highlights the need to develop efficient ways to target them.

Particularly in secondary progressive MS (SPMS), meningeal tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) are frequently observed and correlate with a more severe disease phenotype [

30]. B-cells residing within these follicles are particularly resistant to mAb-mediated depletion. In addition to the minimal CNS biodistribution of mAbs, the follicular microenvironment provides survival signals and acts as a physical barrier, further hindering antibody penetration and effector-cell access [

30]. CAR T cells are being explored to overcome these access-related limitations. Known mechanisms facilitating the diapedesis of activated leukocytes across the BBB [

31], along with experience from CAR T-cell uses in CNS malignancies which show significant CAR T-cell CNS penetration [

32], give promise for the expectation of a similar scenario in their application in CNS autoimmunity. This can fundamentally change the targeting of until now inaccessible targets.

Figure 5a.

Illustration of the differential ability of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells versus monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to cross the blood-brain-barrier (BBB). The expanded inset depicts the leukocyte adhesion cascade enabling CAR T-cell diapededsis across the BBB endothelium. The process involves four steps: (1) capture, where P-selectin on endothelium binds P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) on activated CAR T-cells; (2) rolling and adhesion, as integrins on T-cells engage with endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1); while cells roll with blood flow (3) activation and firm adhesion, mediated by integrin conformational change from inactive (bent) to active (straight); and (4) diapedesis, in which CAR T-cells migrate through endothelial tight junctions to enter the CNS. In contrast, mAbs (e.g., Rituximab) are shown unable to pass the BBB, due to the existence of dense tight junctions between endothelial cells [

28,

31].

"Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 5a.

Illustration of the differential ability of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells versus monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to cross the blood-brain-barrier (BBB). The expanded inset depicts the leukocyte adhesion cascade enabling CAR T-cell diapededsis across the BBB endothelium. The process involves four steps: (1) capture, where P-selectin on endothelium binds P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) on activated CAR T-cells; (2) rolling and adhesion, as integrins on T-cells engage with endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1); while cells roll with blood flow (3) activation and firm adhesion, mediated by integrin conformational change from inactive (bent) to active (straight); and (4) diapedesis, in which CAR T-cells migrate through endothelial tight junctions to enter the CNS. In contrast, mAbs (e.g., Rituximab) are shown unable to pass the BBB, due to the existence of dense tight junctions between endothelial cells [

28,

31].

"Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 5b.

Proposed elimination mechanism of B-cells e.g. CD19 (+ve) within tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) in the subarachnoid space of the leptomeninges of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells. CAR T-cells successfully migrate into the leptomeningeal compartment while monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) do not. The left inset depicts this differential ability. The inset on the right shows the pathogenic cellular organization within the TLS, consisting of: B-cells, plasma cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and reticular fibres. The lower panel depicts CAR T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity directed against CD19 (+ve) B-cells [

28,

33]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 5b.

Proposed elimination mechanism of B-cells e.g. CD19 (+ve) within tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) in the subarachnoid space of the leptomeninges of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells. CAR T-cells successfully migrate into the leptomeningeal compartment while monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) do not. The left inset depicts this differential ability. The inset on the right shows the pathogenic cellular organization within the TLS, consisting of: B-cells, plasma cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and reticular fibres. The lower panel depicts CAR T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity directed against CD19 (+ve) B-cells [

28,

33]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

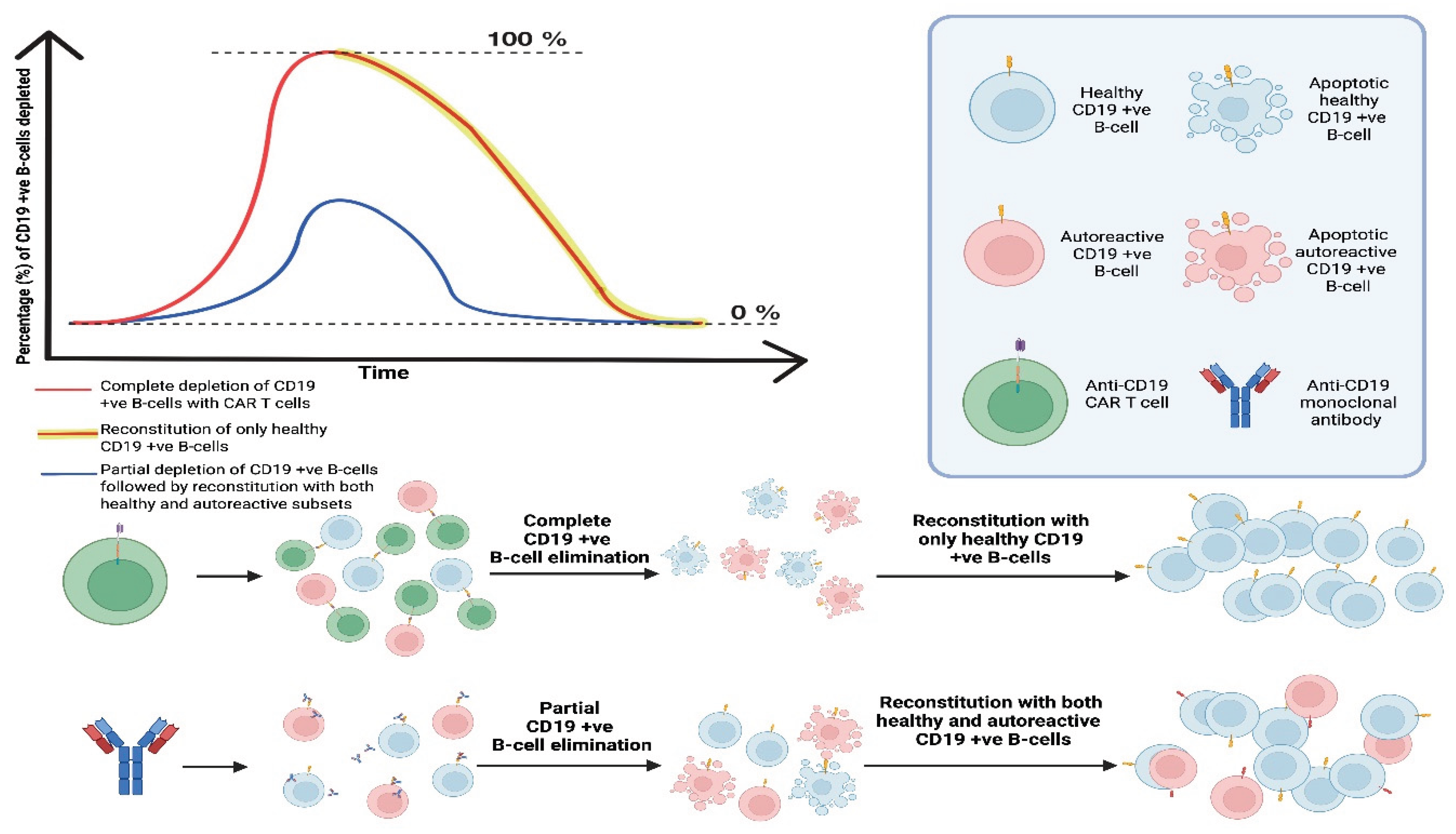

4. Could CAR T-Cell Therapies Achieve an “Immune Reset” to Cure CNS Autoimmunity?

The concept of “resetting” the immune system in autoimmunity has garnered significant attention, as it aims to address autoimmunity from its roots. The underlying rationale is that by fully eliminating immune populations with a limiting contribution in the pathophysiological mechanisms of disease and allowing for their reconstitution, autoreactive subsets may be absent in the regenerated repertoire unless a genetic etiology drives autoimmunity. This approach holds the potential for complete disease remission with discontinuation of any form of therapy.

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (aHSCT) is also being explored as a strategy to achieve “immune resetting” in CNS autoimmunity, wherein hematopoietic stem cells are introduced into the patient following the administration of chemotherapeutic regimens to synergistically induce extensive myeloablation, protocols originally developed for cancer treatment [

34].

In this context, CAR T-cells offer a distinctive advantage over aHSCT by allowing for the selective targeting rather than broad depletion. The myeloablative chemotherapies and aHSCT administration are indiscriminate when targeting myeloid derived cells, whereas CAR T-cells have an antigen-defined cellular target, sparing more unrelated cells, constituting them a potentially safer option.

“Immune resetting” has been observed in peripheral autoimmunity with the use of anti-CD19 CAR T-cells in 5 systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients, with active, multi-organ SLE at baseline [

35]. Immunosuppressive therapies were ceased, and a drug-free remission was achieved in all five patients. They all showed their B-cell populations re-establishing withing 110 +/- 32 days post CAR T-cell infusion with no SLE relapse after long-term follow-ups. The immune phenotype of the B-cells of these patients showed the regenerated populations being mostly CD21(+ve)/CD27(+ve) naive cells, CD21(+ve)/CD27(+ve) memory B-cells and the commonly proliferated in SLE, CD11c (+ve) and CD21

lo populations being absent.

Figure 6.

Proposed model of “immune resetting” specific populations of cells e.g. CD19 (+ve) B-cells. The graph shows that anti-CD19 CAR T-cells induce rapid and complete depletion of CD19 (+ve) B-cells (healthy and autoreactive), followed by reconstitution with solely healthy CD19 (+ve) B-cells. In contrast, anti-CD19 monoclonal antibodies achieve only partial, transient depletion, permitting survival and subsequent re-emergence of both healthy and autoreactive CD19 (+ve) B-cells.

"Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 6.

Proposed model of “immune resetting” specific populations of cells e.g. CD19 (+ve) B-cells. The graph shows that anti-CD19 CAR T-cells induce rapid and complete depletion of CD19 (+ve) B-cells (healthy and autoreactive), followed by reconstitution with solely healthy CD19 (+ve) B-cells. In contrast, anti-CD19 monoclonal antibodies achieve only partial, transient depletion, permitting survival and subsequent re-emergence of both healthy and autoreactive CD19 (+ve) B-cells.

"Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

4. Adverse Side-Effects Associated with CAR T-Cell Therapies and a Way to “Switch Off” Their Activity as a Safety Measure

4.1. Adverse Side-Effects

Unfortunately, CAR T-cell therapy is associated with toxicities that can be life-threatening in some patients. The most common severe toxicities are cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). Both are cytokine-driven: CRS manifests as systemic inflammation with fever, hypotension, and hypoxia, whereas ICANS involves CNS inflammation presenting as encephalopathy with aphasia, tremor, and seizures. Key cytokines implicated include interferon γ, TNF α, and interleukins 1, 2, 6, 8, and 10. Grading for both syndromes relies on ASTCT criteria [

36].

Clinically, ICANS usually emerges within days to a couple of weeks after infusion, and CRS also within several weeks after the infusion in almost 100% of patients that received anti-CD19 CAR T-cells. While mechanisms are not fully defined, ICANS is thought to arise from endothelial activation and blood–brain-barrier dysfunction, and CRS is the result of a cytokine “storm” from the extensive and rapid CAR T-cell activation [

37].

Management is syndrome-specific. For CRS, IL-6 receptor blockade with Tocilizumab is standard, with corticosteroids added for severe or refractory cases. IL-1 blockade with Anakinra is increasingly used when CRS or ICANS is refractory to initial therapy. In contrast, isolated ICANS is managed primarily with corticosteroids as Tocilizumab is not reliably effective for ICANS in the absence of concurrent CRS [

38].

In a report of 957 patients with hematologic malignancies who received Tisagenlecleucel or Axicabtagene Ciloleucel, both anti-CD19 CAR T-cell products, approximately 5% died from non-relapse causes within 30 days of their initial infusion [

39].

Early experience with CD19-directed CAR T cells in autoimmune diseases, including CNS autoimmunity, suggests lower rates and severity of CRS and ICANS than those observed in cancer. This is most logically due to a lower total antigen burden (B-cell populations) in autoimmunity compared to malignancies, resulting in milder CAR T responses and fewer pro-inflammatory killing by-products released into the circulation [

40].

A separate safety consideration is on-target, off-tumour toxicity, which refers to recognition of the intended antigen on healthy tissues when expressed outside the target population. A notable example is a 2010 phase I trial in which a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer received third-generation anti-HER2/ERBB2 CAR T cells and developed respiratory failure within minutes, dying hours later. The event was traced to recognition of physiologic HER2 on lung epithelium, triggering a massive cytokine surge [

41].

This phenomenon has not been observed with anti-CD19 CAR T cells. CD19 expression is highly restricted to the B-cell lineage, with no meaningful expression on other cells. Therefore, HER2-like fatal on-target, off-tumour injury to vital organs, including the brain, is considered highly unlikely on current evidence with anti-CD19 and similar anti-B-cell CAR T-cell therapies. The expected on-target, off-“tumour” effect of anti-B-cell CAR T-cell therapies is B-cell aplasia with hypogammaglobulinemia, reflecting depletion of both pathogenic and non-pathogenic B cells. This can result in immune compromise; immunoglobulin replacement therapy can be utilised if needed.

4.2. iCasp9 Suicide System [42]

As previously discussed, the use of CAR T-cell therapy can be accompanied by adverse side effects. To improve safety, researchers have developed a CAR T-cell “suicide” system designed to enable the elimination of infused CAR T-cells in the event of severe toxicity. This strategy involves the co-expression of an inducible caspase-9 (iCasp9) safety switch, which can trigger downstream apoptotic signalling upon administration of a chemical inducer of dimerization (CID).

Although no currently approved or clinically used CAR T cell products incorporate this system, preclinical studies in animal models presented highly promising results, showing that iCasp9 effectively depletes CAR T cells following CID administration. CAR T-cells were monitored on days 7 and 14 post-infusion showing their persistence, and on day 14, CID was administered, leading to dimerization and activation of the iCasp9 proteins. Within three days (day 17), CAR T cell signal intensity was almost eliminated with even less signal measured by day 22 (eight days post-CID). In contrast, a control group (no CID) showed stable CAR T cell persistence over the same time.

Development of such safety-switch technologies provides an important safeguard when severe adverse effects occur. Incorporating these approaches could significantly enhance the risk/benefit profile of CAR T-cell therapies, potentially expanding their applicability to less severe forms of disease including CNS autoimmunity.

5. The Plasticity in Different CAR T-Cell Constructs

Plasticity in CAR constructs involves several parameters. One key parameter is the antigen targeted. This flexibility allows us to explore disease-specific cellular targets to more precisely eliminate autoreactive populations and spare healthy subsets according to the pathophysiology behind different CNS autoimmune conditions. Another important parameter is the intracellular signalling domain which varies across CAR generations. This domain translates antigen-recognition into signalling and activation of the CAR T-cell. By modifying these signalling motifs, we can fine-tune the activity and persistence of the therapy, tailoring the CAR T-cell therapy intensity accordingly. A newer concept being explored involves expressing the CAR on different cell lines. This approach could allow us to harness other cellular capacities to become selectively activated, rather than remaining purely cytotoxic. Examples include the expression of CAR on immunosuppressive but not cytotoxic T-cells like Tregs.

Different approaches to CAR expression are also under study. The current standard involves transducing T-cells with viral vectors carrying the CAR transgene, but other strategies, including mRNA-based transient CAR expression, are being explored. Finally, an area of interest is the source of the T-cells used to generate CAR T-cells and whether they are coming from the individual patient (autologous) or from a donor (allogeneic).

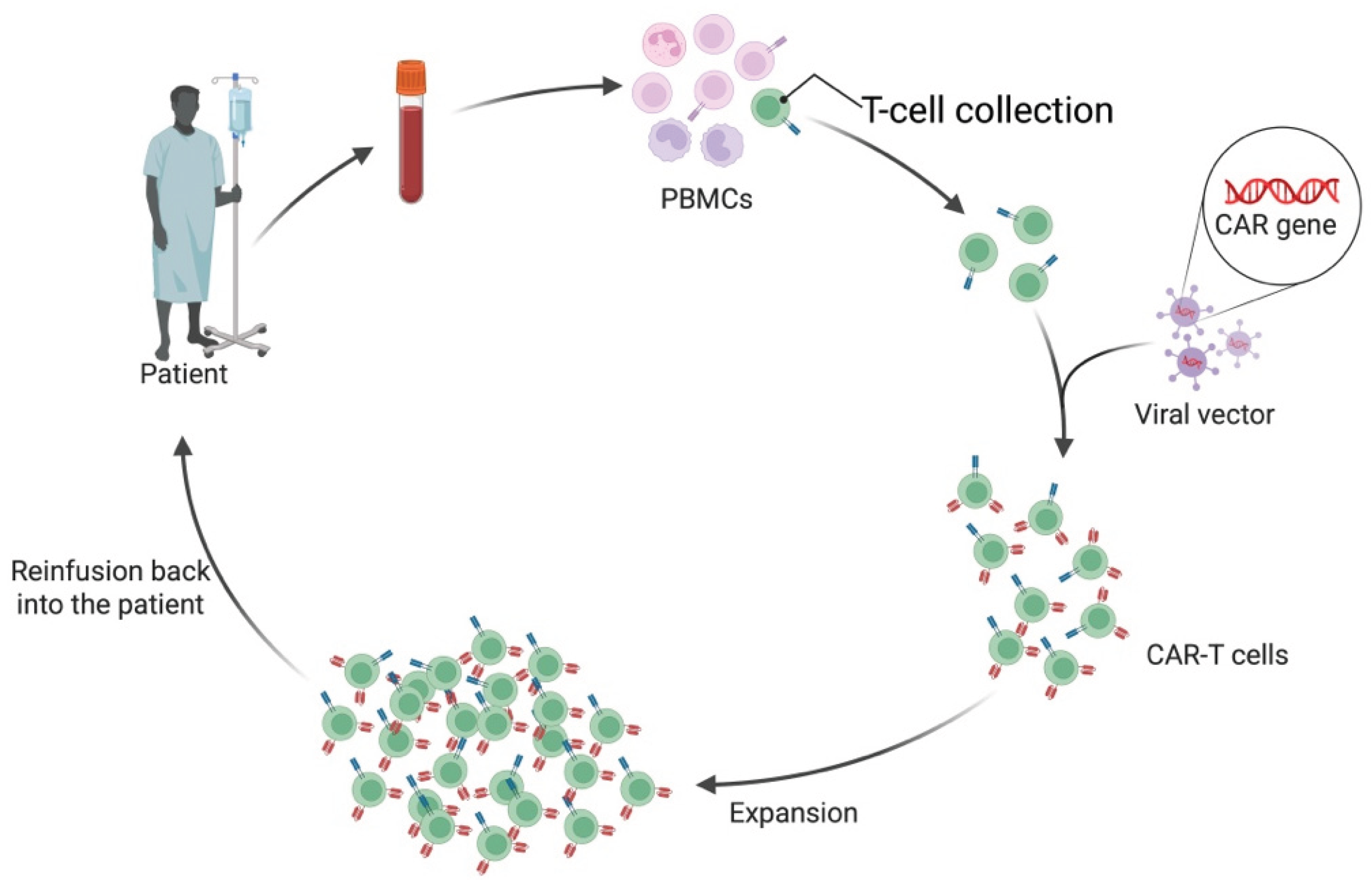

5.1. Allogeneic CAR T-Cells

CAR T-cell preparation typically begins with leukapheresis, a procedure that collects T-cells from the patient (in autologous therapy) or a donor (in allogeneic therapy). T-cells are often selected for surface markers indicative of differentiation state and functionality. Once collected, these T-cells are genetically modified to express the CAR, most commonly using viral vectors such as lentiviruses or retroviruses. These vectors deliver DNA encoding the CAR transgene, which integrates into the host T-cell genome, leading to stable CAR expression. Following successful engineering and expansion of the CAR T-cell population, they are reinfused back into the patient [

43] (See

Figure 7a).

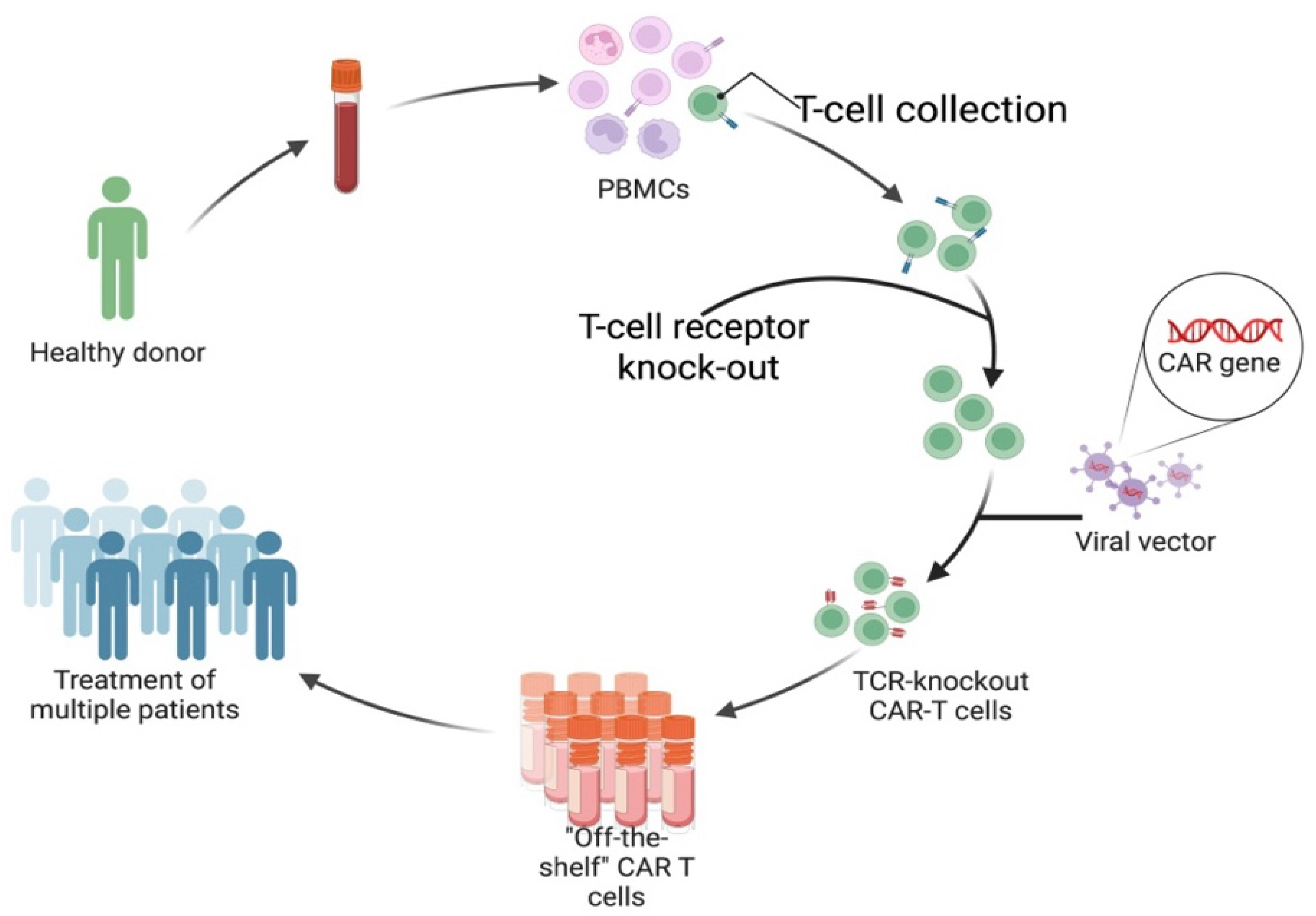

All six currently FDA-approved CAR T-cell products are autologous. Allogeneic CAR T-cellss have significant advantages, and ongoing clinical trials are exploring them. As the name suggests, allogeneic CAR T-cells are not derived from the individual patient but are an off-the-shelf option using T-cells collected from healthy donors (See

Figure 7b). Significant advantages come with this, as the preparation of autologous CAR T-cells takes over two weeks and requires extensive specialised facilities, with costs ranging into the hundreds of thousands of dollars [

44].

Autologous CAR T-cells fail to respond in 10–20% of patients who receive them in oncology, while autoimmunity data are early but growing [

45]. Failure in response arises because harvesting T-cells from the individual patient carries risks regarding the quality and, especially, the quantity of leukocytes when patients undertake treatment protocols involving immunosuppressive and/or lymphodepleting agents [

46]. Treatment-related T-cell lymphopenia excludes patients from receiving autologous CAR T-cell therapy or makes retreatment unfeasible. T-cell fitness also varies with factors such as age and chronic infections [

47]. Unlike autologous products, allogeneic CAR T-cells are not limited by the patient’s own T-cell quantity or quality. Donor-derived T-cells tend to be more “fit” than patient cells and can be banked in preset dose ranges [

48].

The main limitation in safely using allogeneic products is the potential of Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) or Host-versus-Graft Disease (HVGD). GVHD involves the CAR T-cells recognising the host’s tissue as foreign and attacking it; this can result from incomplete knockout of the native TCRs during allogeneic preparation. Whereas HVGD involves the host recognising the CAR T-cells as foreign and eliminating them due to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch [

49].

One allogeneic CAR T-cell example being investigated is the so-called azer-cel from TG Therapeutics, which was granted FDA approval for a Phase I clinical trial in 2024 for its application in autoimmune diseases and is currently recruiting patients (NCT06680037). Other allogeneic CAR T-cells under investigation are included in

Table 1.

Figure 7.

a. Autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell manufacturing workflow. Peripheral blood is collected from the patient to obtain peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), from which T-cells are isolated. These T-cells are then genetically modified using a viral vector that introduces the CAR gene, creating CAR T-cells capable of recognising and targeting the cell that expresses an antigen for which the CAR has affinity and specificity. They are then expanded and infused back into the patient [

44]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 7.

a. Autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell manufacturing workflow. Peripheral blood is collected from the patient to obtain peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), from which T-cells are isolated. These T-cells are then genetically modified using a viral vector that introduces the CAR gene, creating CAR T-cells capable of recognising and targeting the cell that expresses an antigen for which the CAR has affinity and specificity. They are then expanded and infused back into the patient [

44]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 7.

b. Production of allogeneic or “off-the-shelf” CAR T-cells. Peripheral blood collected from healthy donors to obtain PBMCs, from which T-cells are isolated. Endogenous T-cell receptor (TCR) is knocked out to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following infusion. The modified T-cells are then transduced with a viral vector carrying the CAR gene, generating TCR-knockout CAR T-cells. These engineered cells are expanded and cryopreserved as standardized “off-the-shelf” products that can be used to treat multiple patients [

48]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 7.

b. Production of allogeneic or “off-the-shelf” CAR T-cells. Peripheral blood collected from healthy donors to obtain PBMCs, from which T-cells are isolated. Endogenous T-cell receptor (TCR) is knocked out to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following infusion. The modified T-cells are then transduced with a viral vector carrying the CAR gene, generating TCR-knockout CAR T-cells. These engineered cells are expanded and cryopreserved as standardized “off-the-shelf” products that can be used to treat multiple patients [

48]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

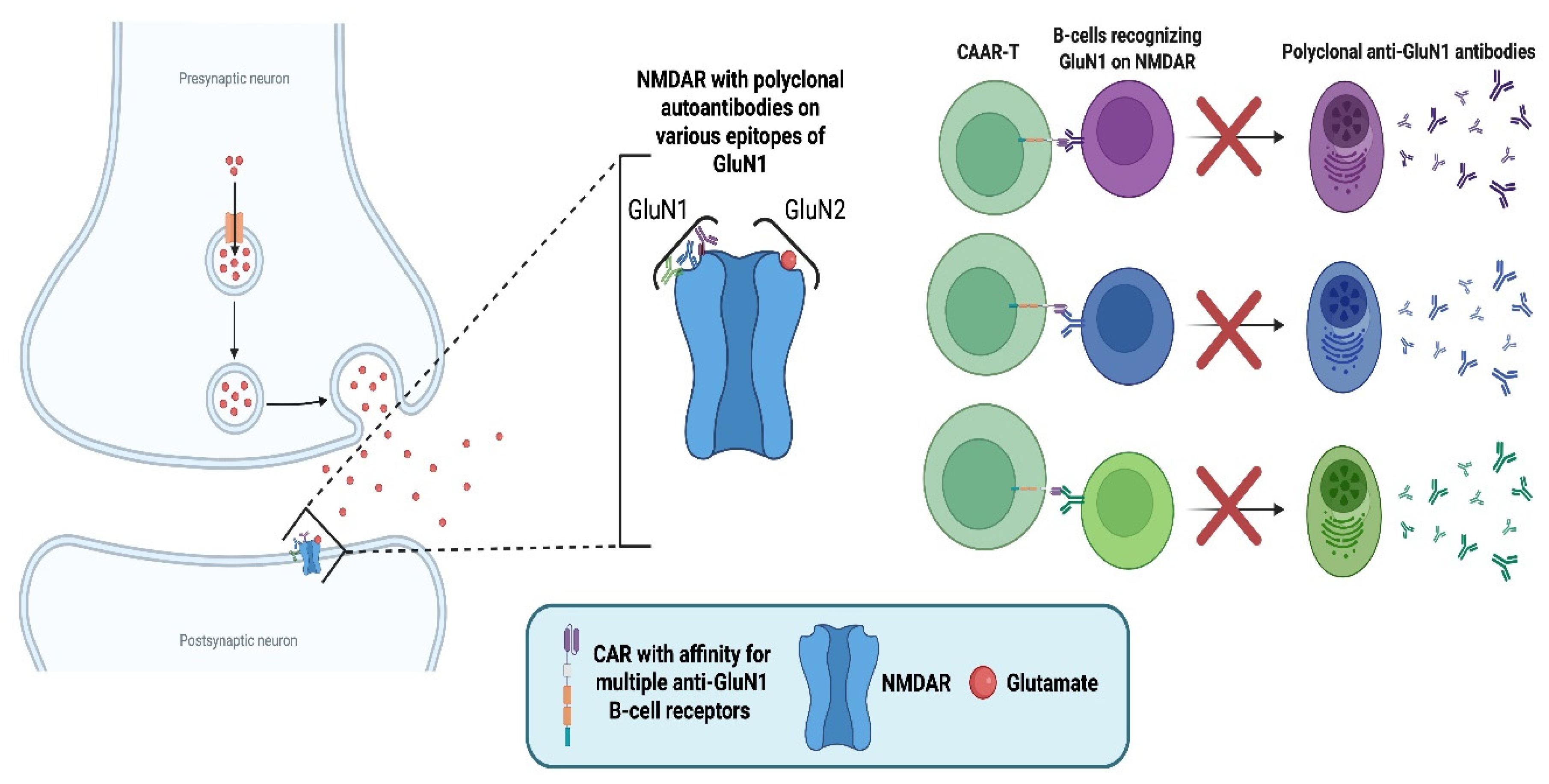

5.2. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate Receptor (NMDAR)-Specific Chimeric Autoantibody Receptor (CAAR) T-Cells for NMDAR Autoimmune Encephalitis (AE)

Autoimmune encephalitides (AEs) are characterised by autoantibody production against specific neuronal or glial antigens. Among these, NMDAR encephalitis is the most common subtype. The NMDAR is a glutamate-gated ion channel that plays a key role in synaptic transmission, synapse formation, and plasticity, thereby contributing to learning and memory [

50].

The immunopathological mechanism of NMDAR AE involves polyclonal autoantibodies with affinity against the glutamate (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor subunit 1 (GluN1) subunit of the NMDAR [

51,

52] resulting in NMDAR loss of function with subsequent synaptic changes that manifest as psychosis, epileptic episodes, and loss of cognitive function, with encephalopathy features [

53,

54]. NMDAR AE involves the presence of autoantibodies in both CSF and serum. The source of these autoantibodies are short-lived plasma cells continuously repopulated by the differentiation of anti-NMDAR memory B-cells [

55].

Due to the solely autoantibody-mediated pathology, a recent study investigated NMDAR-specific Chimeric Autoantibody Receptor (CAAR) T-cells [

56]. The CAR construct specifically recognises the B-cell receptor (BCR) of NMDAR-specific B-cells to specifically target the autoantibody-producing populations while sparing healthy subsets. This was achieved by utilising an NMDAR autoantigen extracellular domain.

The repertoire of autoantibodies in NMDAR AE involves polyclonal IgG antibodies with affinity to various epitopes on the GluN1 subunit of NMDAR [

55]. Therefore, the CAR construct was designed to simultaneously recognise variable BCRs, as the polyclonal antibody-pool must be eliminated for successful disease remission. Polyclonality of autoantibodies is a major issue faced when designing autoantibody-specific CAAR T-cells, as the CAR needs to recognise various BCRs without recognising healthy antigens.

The study did not involve humans but presented promising results in mouse models, both in vivo and in vitro. NMDAR-CAAR T-cells were successfully activated with human autoantibodies, secreted effector molecules, and killed targeted cells in vitro. Moreover, they proliferated upon encountering target cells and eliminated pathogenic populations in vivo without signs of therapy-induced toxicity.

This CAR construct highlights the plasticity of CAR design, a key strength of this revolutionary therapeutic platform. Currently, there are no approved therapies for AE, but there is an ongoing phase III trial (NCT05503264) investigating satralizumab in NMDAR and Leucine-rich glioma-inactivated 1 (LGI1) AE patients, along with inebilizumab (NCT04372615) and bortezomib (NCT03993262) in phase IIb clinical trials.

Figure 8.

Mechanism of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA)–specific chimeric autoantibody receptor (CAAR) T-cells in anti-NMDAR autoimmune encephalitis (AE). The left panel depicts the pathophysiology of anti-NMDAR AE, where polyclonal autoantibodies targeting the glutamate (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor subunit 1 (GluN1) of NMDA receptors disrupt synaptic signalling. The right panel illustrates the mechanism of CAAR T-cells engineered to express an NMDA receptor–derived extracellular domain that binds multiple B-cell receptors (BCRs) on anti-GluN1 B-cells. These CAAR T-cells eliminate pathogenic B-cells, preventing their differentiation into plasma cells. The ability of the same CAR to simultaneously recognise and bind multiple BCRs is depicted as the elimination of the polyclonal pool of plasma cells, which is the goal to achieve disease remission [

55,

56]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 8.

Mechanism of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA)–specific chimeric autoantibody receptor (CAAR) T-cells in anti-NMDAR autoimmune encephalitis (AE). The left panel depicts the pathophysiology of anti-NMDAR AE, where polyclonal autoantibodies targeting the glutamate (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor subunit 1 (GluN1) of NMDA receptors disrupt synaptic signalling. The right panel illustrates the mechanism of CAAR T-cells engineered to express an NMDA receptor–derived extracellular domain that binds multiple B-cell receptors (BCRs) on anti-GluN1 B-cells. These CAAR T-cells eliminate pathogenic B-cells, preventing their differentiation into plasma cells. The ability of the same CAR to simultaneously recognise and bind multiple BCRs is depicted as the elimination of the polyclonal pool of plasma cells, which is the goal to achieve disease remission [

55,

56]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

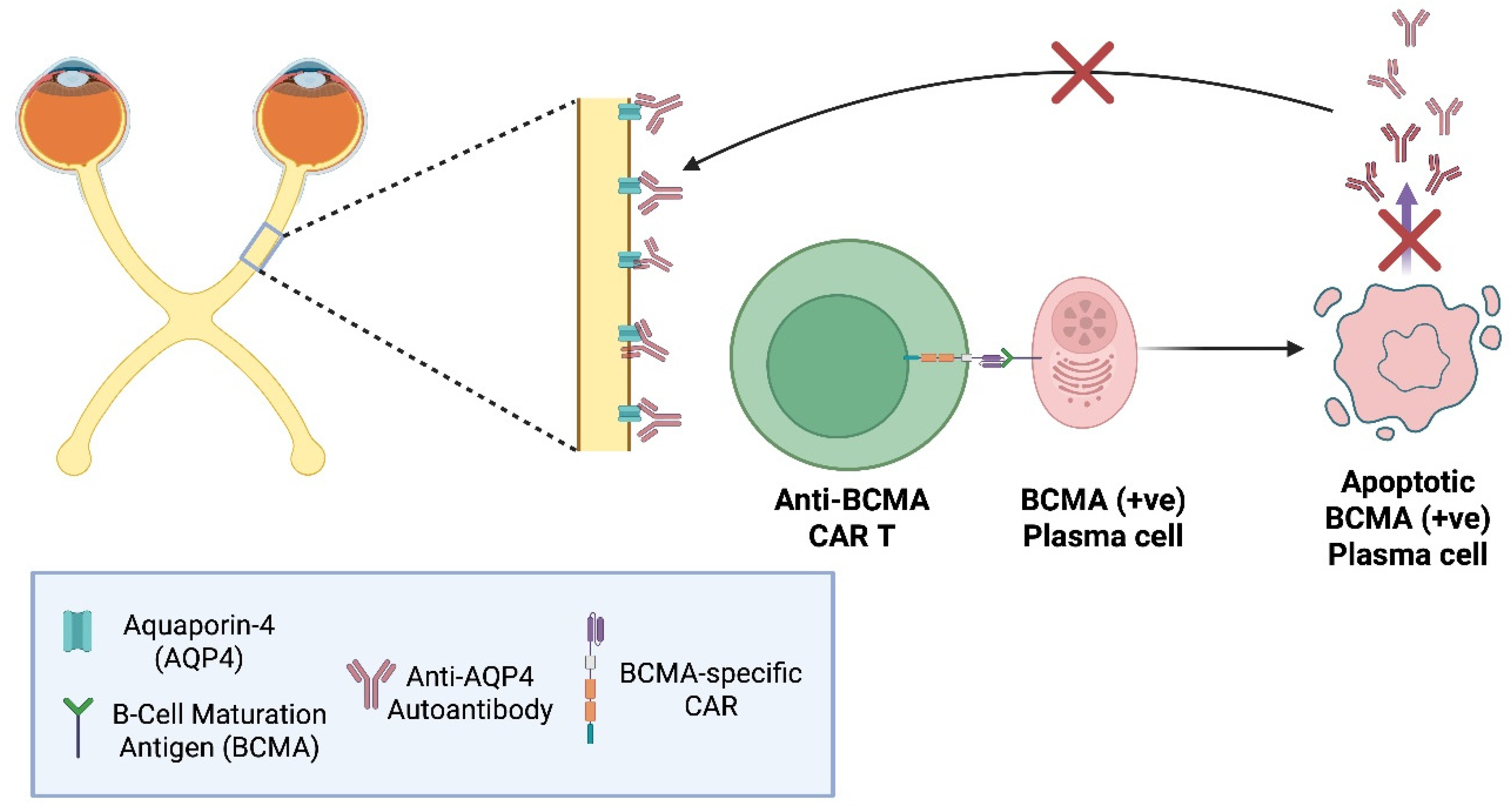

5.3. Anti-BCMA CAR T-Cells in NMOSD

NMOSD was long considered a variant of MS until the discovery of anti–aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibodies in 2004 by Lennon et al. [

57]. Polyclonal, plasma cell–derived IgGs primarily bind AQP4 on astrocytes of the optic nerve, but also the spinal cord, and other specific CNS locations, triggering complement activation, inflammation, astrocyte loss, and demyelination.

First-line therapy has traditionally combined high-dose intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone for acute attacks with targeted mAb immunotherapies; however, 25–60% of NMOSD patients on these regimens still experience relapses [

58]. B-cell–depleting mAbs reduce relapse rates but often fail to lower circulating anti–AQP4 titers, since long-lived plasma cells may lack CD19/CD20 expression [

59]. Recently introduced anti-C5 therapies, such as ravulizumab, have shown outstanding therapeutic outcomes, achieving up to 98.6% reduction in relapse risk [

60].

Unlike MS, in which CD19/CD20 (+ve) B-cells, among others, act as APCs, sustaining T-cell–mediated demyelination, NMOSD is primarily an autoantibody-driven astrocytopathy. This distinction and the usual lack of CD19 and CD20 expression on plasma cells, support the rationale for anti-BCMA CAR T-cells instead of anti-CD19 or anti-CD20. BCMA is a TNF receptor family member upregulated on late stage plasmablasts and mature plasma cells [

61]. BCMA-targeted CAR T-cell therapies aim to eliminate BCMA(+ve)/CD19/CD20(-ve) B-cells which anti-CD19/CD20 CAR T-cellscannot, while sparing non-antibody-secreting B-cells.

Figure 9.

Anti-B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD). In this autoimmune disorder, plasma cells produce pathogenic anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP4) autoantibodies that target AQP4 channels on astrocytes mainly within mainly the optic nerve and spinal cord, leading to inflammation and demyelination. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cells are engineered to recognise BCMA expressed on late plasma cells and plasmablasts. Upon engagement with BCMA, the CAR T-cells get activated and induce apoptosis, eliminating the source of anti-AQP4 autoantibodies [

58,

59].

"Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 9.

Anti-B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD). In this autoimmune disorder, plasma cells produce pathogenic anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP4) autoantibodies that target AQP4 channels on astrocytes mainly within mainly the optic nerve and spinal cord, leading to inflammation and demyelination. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cells are engineered to recognise BCMA expressed on late plasma cells and plasmablasts. Upon engagement with BCMA, the CAR T-cells get activated and induce apoptosis, eliminating the source of anti-AQP4 autoantibodies [

58,

59].

"Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

5.4. MOG-Specific CAR T-Regulatory Cells (CAR Tregs) in MS

CAR Tregs represent an alternative approach to treat multiple sclerosis (MS) compared to anti-CD19 CAR T-cells. As previously discussed, CD19 is expressed in most B-cell populations; thus, anti-CD19 CAR T-cells can induce deep B-cell depletion, potentially leading to opportunistic infections due to extensive immunosuppression until protective immune populations reconstitute.

The capacity to engineer CARs on different cell types has enabled the exploration of anti-MOG CAR Tregs as an alternative to conventional cytotoxic anti-CD19 CAR T-cells. In contrast to cytotoxic CAR T-cells that recognise and eliminate e.g. CD19 (+ve) B-cells, MOG-specific CAR Tregs aim to harness the immunosuppressive capacities of regulatory T-cells to silence the immune response against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) without directly killing B-cells.

The immunosuppressive mechanisms of MOG-specific CAR Tregs involve CAR-mediated recognition of native MOG in the CNS, which activates Tregs and promotes the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β. These molecules inhibit locally resident immune populations and are expected to upregulate immune checkpoint receptors, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell-death-protein 1 (PD-1) [

62].

A preclinical study [

63] investigated the capacity of human MOG-specific CAR Tregs in inhibiting the proliferation of CD4 (+ve) conventional T-cells (Tconvs) ex vivo. The MOG-specific CAR Tregs demonstrated antigen-specific activity, significantly inhibiting Tconv proliferation only upon MOG stimulation, following pre-stimulation with MOG-coated plates or anti-CD3/CD28 beads.

This antigen-specific regulatory approach represents a promising direction for precision immune modulation in MS, offering potentially therapeutic effects without the broad immunosuppression observed with cytotoxic CAR T-cell therapies.

Figure 10.

Myelin oligodendrocyte (MOG)-specific chimeric antibody receptor (CAR) Tregs recognise and bind MOG, leading to their activation. Upon activation, they secrete immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10, IL-35, and TGF-β) suppressing B-cell activation and differentiation into antibody-producing plasma cells and upregulate CTLA-4 which interacts with its ligands (CD80 & CD86) on antigen-presenting-cells (APCs) limiting T-effector activation. Expression of CD25 consumes IL-2, depriving effector T-cells of this growth factor, inhibiting them [

62,

63]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 10.

Myelin oligodendrocyte (MOG)-specific chimeric antibody receptor (CAR) Tregs recognise and bind MOG, leading to their activation. Upon activation, they secrete immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10, IL-35, and TGF-β) suppressing B-cell activation and differentiation into antibody-producing plasma cells and upregulate CTLA-4 which interacts with its ligands (CD80 & CD86) on antigen-presenting-cells (APCs) limiting T-effector activation. Expression of CD25 consumes IL-2, depriving effector T-cells of this growth factor, inhibiting them [

62,

63]. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

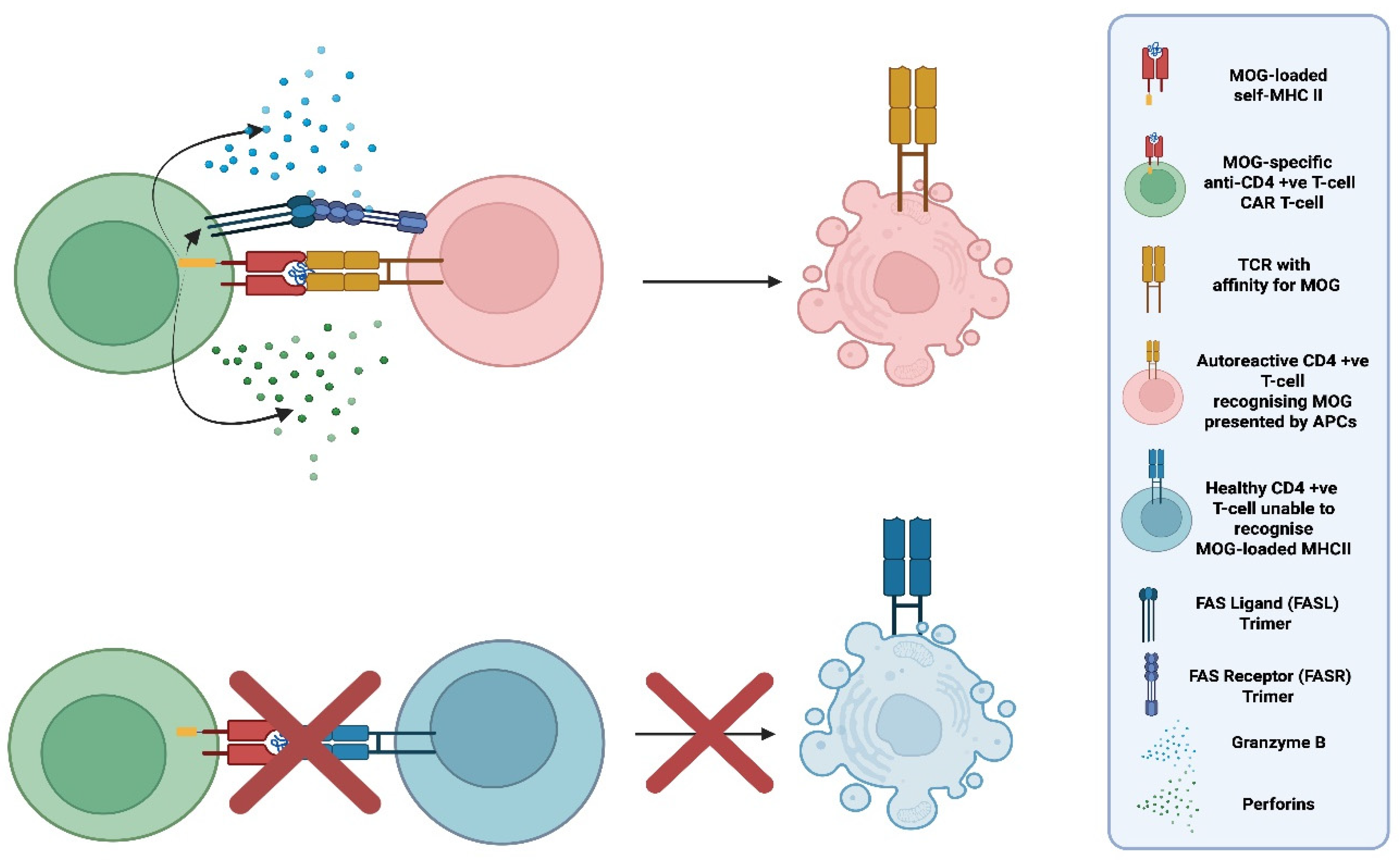

5.5. Peptide-Specific CAR T-Cells (pMHCII CAR T-Cells ) for the Selective Depletion of Autorective T-Cells [64]

In 2022 in a preclinical study with mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), Jaeu Yi et al. introduced the concept of replacing the traditional CAR recognition domain (an antibody-derived scFv), with an MHC II molecule loaded with self-peptides. MHC II is expressed by antigen-presenting-cells (APCs) presenting to and activating CD4 (+ve) T-helper cells which in-turn promote inflammation and activate other immune effectors including cytotoxic CD8 (+ve) T-cells. By using MOG-loaded MHC II molecules as the extracellular domain, the peptide-specific CAR can selectively bind self-reactive T-cells whose TCRs recognise MOG presented by APCs. Upon encountering a CD4 (+ve) T-cell expressing a MOG-specific TCR, the MOG-MHCII-CAR T-cell gets activated and eliminates the autoreactive CD4 (+ve) T-cell.

Yi et al. demonstrated that these pMHCII-CAR T-cells can efficiently eliminate both naïve and activated antigen-specific CD4 (+ve) T-cells in vivo. Importantly, the sensitivity of the CAR was influenced by TCR affinities: the original lower-sensitivity MOG35–55 pMHCII-CAR preferentially eliminated high-affinity MOG-specific T-cells, including regulatory T-cell (Treg) clones, whereas many lower-affinity effector T-cells persisted. Engineering improvements that enhanced CAR stability and signalling strength increased sensitivity, enabling broader deletion of both high- and low-affinity autoreactive T-cells. These findings highlight the critical role of TCR affinity in autoimmune pathogenesis and suggest that pMHCII-CAR designs could be used to target specific subsets of autoreactive T-cells. Up to date, there are no human trials active or planned that investigate this concept, but it still shows the potential future capacities of this revolutionary therapy in CNS autoimmunity.

Figure 11.

Schematic illustration of the selective elimination of autoreactive CD4 (+ve) T-cells recognising myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) by peptide (MOG)-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells (MOG-MHCII-CAR T-cells). Top: A pMHCII-CAR T-cell engineered to express an MHC II molecule loaded with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) selectively engages autoreactive CD4 (+ve) T-cells whose T-cell receptors (TCRs) recognise MOG presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). This antigen-specific interaction triggers targeted elimination of the autoreactive CD4(+ve) T-cell. Bottom: CD4⁺ T-cells that do not recognize MOG do not bind the MOG–MHCII CAR and are spared, demonstrating the specificity of this CAR design for autoreactive CD4 (+ve) T-cells. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

Figure 11.

Schematic illustration of the selective elimination of autoreactive CD4 (+ve) T-cells recognising myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) by peptide (MOG)-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells (MOG-MHCII-CAR T-cells). Top: A pMHCII-CAR T-cell engineered to express an MHC II molecule loaded with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) selectively engages autoreactive CD4 (+ve) T-cells whose T-cell receptors (TCRs) recognise MOG presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). This antigen-specific interaction triggers targeted elimination of the autoreactive CD4(+ve) T-cell. Bottom: CD4⁺ T-cells that do not recognize MOG do not bind the MOG–MHCII CAR and are spared, demonstrating the specificity of this CAR design for autoreactive CD4 (+ve) T-cells. "Created in BioRender. demetriou, f. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/jw8pks9 ".

5.6. mRNA-Induced CAR T-Cells

Conventional CAR T-cell manufacturing involves transducing patient-derived T-cells with viral vectors, leading to permanent CAR expression in each engineered and descendant cell. While this approach yields potent, long-lived CAR T-cells, it also results in unpredictable pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) [

65]. This unpredictability is among the reasons CAR T-cell therapies are confined to last-resort use in refractory or aggressive cases.

In contrast, mRNA-based CAR T-Cell therapies offer predictable persistence and a level of intensity that can be easily manipulated. mRNA has a defined half-life, which reflects the duration of CAR expression. The mRNA molecule can be delivered ot the T-cells to create CAR T-cells using electroporation which results in CAR expression for roughly a week [

66,

67]. This transient expression results in a more controllable PK/PD profile, minimising the risk of prolonged or excessive activity, potentially constituting mRNA CAR T-Cell therapies a choice for less aggressive forms of diseases.

With mRNA-transduced CARs, lymphodepletion therapy, a process used to create optimal conditions for successful in vivo expansion, is not required. The risks associated with lymphodepletion include cytopenia and an added risk of opportunistic infections due to significantly reduced lymphocyte counts. On the downside, patients receiving mRNA-transduced CARs may require repeated dosing to achieve durable disease remission.

A clinical trial currently in phase 1b/2a released data in 2023 on the safety and efficacy of an autologous RNA CAR T-Cell (rCAR T), called Descartes-08, in patients with Myasthenia Gravis (MG) [

68]. Fourteen patients were enrolled, and follow-ups with a median of 5 months showed no dose-limiting toxicities, CRS, or ICANS. Descartes-08 administration resulted in decreases in MG severity that persisted at the most recent follow-up at 9 months.

6. Case Reports of CAR T-Cell Use in CNS Autoimmunity

The available case reports on the use of CAR T-cells in CNS autoimmunity are encouraging but too limited to allow firm conclusions. To date, 15 patients have been reported: 2 with MS, 1 with MOGAD, and 12 with NMOSD. Results from ongoing and planned studies will be crucial for validating these preliminary observations and determining the safety and efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy in CNS autoimmune diseases.

6.1. Anti-CD19 CAR T-Cellsin 2 MS Patients [69]

Kyverna Therapeutics developed KYV-101, an anti-CD19 CAR T-Cell therapy for B-cell-driven autoimmunity, and released data on two MS patients: a 47-year-old female with relapsed-refractory multiple sclerosis (RRMS) treated with KYV-101, who showed no treatment-related toxicity, improved walking distance, reduced serum IgG at day 14 through day 64, and a decrease in oligoclonal bands from 13 to 6 sustained through day 64. The second patient, a 36-year-old male with primary-progressive (PPMS) exhibited no CRS or ICANS.

6.2. Anti-CD19 CAR T-Cells in a 25-year-old Male Patient with Refractory Myelin Oligodendrocyte Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD)

MOGAD is another autoimmune CNS disease characterised by demyelination. MOGAD in the past was also under the umbrella of MS. MOG-specific antibodies are found in the CSF and serum of 85% of patients, and OCBs in 15% [

70] of patients with MOGAD.

A case report [

71] describes the use of anti-CD19 CAR T-cells in a patient who, at the age of 18, presented with sensory disturbances in his lower limbs, later accompanied by paresis and impaired bladder emptying. Upon evaluation, MRI revealed a spinal cord lesion extending from T4 to the conus medullaris, with no lesions in the brain. Cell-based assays detected anti-MOG IgG only in the serum (titer 1:160), with no antibodies in the CSF, and AQP4-IgG was negative. Electrophoresis showed no OCBs. In the following years, the patient experienced two episodes of myelitis, followed by six episodes of optic neuritis (ON); ON is the most common initial symptom in MOGAD. Five months after his initial presentation, he developed relapsing sensory impairment, a new spinal cord lesion at T6, and persistent serum MOG-IgG positivity, which led to the initiation of long-term treatment with Rituximab.

All six episodes of ON were treated with intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMTP) and prednisone. In two of these episodes, plasma exchange was performed in conjunction with IVMTP. After the sixth ON episode, the patient underwent optic coherence tomography (OCT), which showed reduced retinal and inner plexiform layer thickness and decreased visual acuity. The aggressiveness of the disease made the patient eligible for autologous anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy (ARI-0001). The results of this CAR T-cell application are highly promising, raising hopes that it may become a therapy capable of curing MOGAD.

Upon the administration of CAR T-cells, complete elimination of CD-19 (+ve) B-cells was achieved by day +7, and the populations re-established in +141 days. The newly formed populations consisted of naïve B-cells and diminished or absent memory B-cells. At day +29, the patient experienced an episode of left ON even though he was already seronegative for MOG IgG. Since then, a year later, he remains healthy with no relapses and free of anti-MOG IgG.

The fact that this is a case report involving a single patient prevents us from drawing any significant conclusions. Additionally, right before the introduction of the CARs, patients undergo lymphodepleting therapy with cyclophosphamide. We cannot exclude the possibility that the observed results are not due to lymphodepletion from these therapies. This study provides class IV evidence as controls were not included.

6.3. Anti-BCMA CAR T-Cells in Twelve NMOSD Patients [72]

A study evaluated the efficacy of anti–BCMA CAR T-Cell therapy in 12 patients with relapsed or refractory AQP4-IgG seropositive NMOSD. All patients experienced adverse events (AEs), primarily hematologic toxicities: leukopenia (100%), neutropenia (100%), anemia (50%), and thrombocytopenia (25%). Infections related to CAR T-cell-mediated immunosuppression occurred in 58% of patients. Notably, no CRS or ICANS were observed.

CAR T-cells remained detectable in peripheral blood for up to six months: 100% at one month (12/12), 73% at two months (8/11), 60% at three months (6/10), and 17% at six months (1/6). The median time to peak expansion was 10 days post-infusion.

Regarding serum biomarkers, anti–AQP4-IgG decreased after infusion in all patients and was below the threshold by week 12 in 70% of patients. Serum BCMA also fell below threshold within the first month post-infusion but returned to baseline by six months. In a follow-up of these patients ranging from 1 to 14 months, 92% of the patients achieved a drug-free remission without any relapses with the discontinuation of all other medications, including corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents. All 12 patients presented with a decreased Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score. Half of the patients had improved visual acuity in at least one eye; 8 out of 12 patients had improved walking abilities, of whom 4 were previously restricted to a wheelchair and were able to walk unassisted. 9 of the 12 patients had improved bowel and bladder function, and 5 did not require manual measures for defecation or urination.

7. Discussion

CAR T-cell therapies are emerging as a potentially transformative option for CNS autoimmune diseases, offering selective, deep, and durable immune modulation that may overcome limitations of current immunotherapies. Existing treatments, including corticosteroids, conventional immunosuppressants, and mAbs, have improved disease outcomes but remain constrained by systemic toxicity, incomplete tissue penetration, especially into the CNS and the need for chronic administration. The ability of CAR T-cells to persist, penetrate protected compartments, and eliminate antigen-defined immune populations provides the rationale for their investigation in CNS autoimmunity.

The early experiences in autoimmune diseases outside the CNS, suggest that CAR T-cells may induce a meaningful and potentially long-lasting remission. Evidence of cases with B-cell reconstitution with a naïve, non-autoreactive phenotype following CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy, supports the possibility of “immune reset”. Case reports in MS, MOGAD, and NMOSD point toward clinical benefits with acceptable acute toxicity profiles. However, these findings remain preliminary given the extremely small number of treated patients and the absence of controlled data.

A major question is whether CAR T-cell therapy can be safely scaled beyond the most refractory cases. Toxicities such as CRS and ICANS, although observed at lower rates in autoimmunity, remain important considerations. Strategies including inducible suicide systems and the use of transient mRNA-based CAR expression may expand the therapeutic window.

Alternative cellular platforms such as CAAR T-cells for exclusively autoantibody-mediated disease, CAR Tregs and pMHCII-CAR T-cells highlight the exceptional modularity of the CAR design and its capacity for disease-specific precision. Allogeneic CAR T-cells represent another important direction, offering off-the-shelf availability and potentially superior T-cell fitness, though challenges such as GVHD and host rejection must be addressed.

Ultimately, CAR T-cell therapies hold the potential to shift the treatment paradigm in CNS autoimmunity by enabling deep, selective, and possibly curative immune interventions. However, the current evidence base is insufficient to draw firm conclusions. Larger, controlled clinical trials and data from ongoing ones, will be essential to determine which patient populations benefit, the durability of remission, the true incidence of toxicity in autoimmune cohorts, and how best to deploy the expanding array of CAR-based platforms. The next several years will define whether CAR T-cell therapy becomes a viable option for broader use or remains reserved for the most severe and treatment-refractory cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.; methodology, M.A and F.D.; investigation, M.A.; resources, F.D.; data curation, F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.D..; writing—review and editing, M.A. and F.D.; Original Figure Formation, F.D.; supervision, M.A..; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| DMT |

Disease modifying therapy |

| BCMA |

B-cell maturation antigen |

| CD |

Cluster of differentiation |

| MS |

Multiple sclerosis |

| mAbs |

Monoclonal antibodies |

| NMOSD |

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder |

| MOGAD |

Myelin oligodendrocyte antibody-associated disease |

| AE |

Autoimmune encephalitis |

| AEm |

Autoimmune encephalomyelitis |

| CAR |

Chimeric antigen receptor |

| MHC |

Major histocompatibility complex |

| TCR |

T-cell receptor |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| NFAT |

Nuclear factor of activated T-cells |

| TNF |

Tumour necrosis factor |

| TIL |

Tumour infiltrating lymphocyte |

| CM |

Co-stimulatory molecule |

| PSMA |

Prostate-specific membrane antigen |

| TRUCKS |

T-cells redirected for universal cytokine-mediated killing |

| ADCC |

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| ADCP |

Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis |

| CDC |

Complement-depended cytotoxicity |

| NK Cell |

Natural killer cell |

| Neu |

Neutrophil |

| MΦ |

Macrophage |

| MAC |

Membrane-attack complex |

| CSF |

Cerebrospinal fluid |

| OCBs |

Oligoclonal bands |

| SPMS |

Secondary progressive MS |

| BBB |

Blood-brain-barrier |

| TLS |

Tertiary lymphoid structure |

| VCAM-1 |

Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| ICAM-1 |

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| aHSCT |

Autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation |

| SLE |

Systemic lupous erythematosus |

| CRS |

Cytokine release syndrome |

| ICANS |

Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome |

| CID |

Chemical Inducer of dimerization |

| Treg |

T-regulatory cell |

| CTLA-4 |

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 |

| PD-1 |

Programmed cell-death-protein 1 |

| GVHD |

Graft-versus-host disease |

| HVGD |

Host-versus-graft disease |

| HLA |

Human leukocyte antigen |

| PBMCs |

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| NMDAR |

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor |

| CAAR |

Chimeric autoantibody receptor |

| BCR |

B-cell receptor |

| LGI1 |

Leucine-rich glioma-inactivated 1 |

| AQP4 |

Aquaporin-4 |

| MOG |

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein |

| TGF |

Transforming growth factor |

| APCs |

Antigen-presenting cells |

| PK |

Pharmacokinetics |

| PD |

Pharmacodynamics |

| MG |

Myasthenia gravis |

| rCAR T |

RNA CAR T-cell |

| RRMS |

Relapse-refractory multiple sclerosis |

| PPMS |

Primary-progressive multiple sclerosis |

| ON |

Optic neuritis |

| IVMTP |

Intravenous methylprednisolone |

| OCT |

Optic coherence tomography |

| EDSS |

Expanded disability status scale |

References

- Ramanathan, S.; Brilot, F.; Irani, S. R.; Dale, R. C. Origins and immunopathogenesis of autoimmune central nervous system disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology 2023, 19, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, L. D.; Cookfair, D. L.; Rudick, R. A.; Herndon, R. M.; Richert, J. R.; Salazar, A. M.; Fischer, J. S.; Goodkin, D. E.; Granger, C. v.; Simon, J. H.; Alam, J. J.; Bartoszak, D. M.; Bourdette, D. N.; Braiman, J.; Brownscheidle, C. M.; Coats, M. E.; Cohan, S. L.; Dougherty, D. S.; Kinkel, R. P.; Whitham, R. H. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Annals of Neurology 1996, 39, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K. P.; Brooks, B. R.; Cohen, J. A.; Ford, C. C.; Goldstein, J.; Lisak, R. P.; Myers, L. W.; Panitch, H. S.; Rose, J. W.; Schiffer, R. B.; Vollmer, T.; Weiner, L. P.; Wolinsky, J. S. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1995, 45, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlis, C.; Angelopoulou, E.; Rentzos, M.; Papageorgiou, S. G.; Anagnostouli, M. Monoclonal Antibodies as Therapeutic Agents in Autoimmune and Neurodegenerative Diseases of the Central Nervous System: Current Evidence on Molecular Mechanisms and Future Directions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 9398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlis, C.; Kotsari, M.; Anagnostouli, M. Advancing Treatment in Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis: The Promise of B-Cell-Targeting Therapies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappell, K. M.; Kochenderfer, J. N. Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2023, 20, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali, A. M.; Nirschl, L.; Sie, C.; Pfaller, M.; Ulianov, O.; Hassler, T.; Federle, C.; Petrozziello, E.; Kalluri, S. R.; Chen, H. H.; Tyystjärvi, S.; Muschaweckh, A.; Lammens, K.; Delbridge, C.; Büttner, A.; Steiger, K.; Seyhan, G.; Ottersen, O. P.; Öllinger, R.; Korn, T. B-cells orchestrate tolerance to the neuromyelitis optica autoantigen AQP4. Nature 2024, 627, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbali, O.; Chitnis, T. Pathophysiology of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody disease. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14, 1137998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, T. v.; Brewer, R. C.; Ho, P. P.; Moon, J.-S.; Jude, K. M.; Fernandez, D.; Fernandes, R. A.; Gomez, A. M.; Nadj, G.-S.; Bartley, C. M.; Schubert, R. D.; Hawes, I. A.; Vazquez, S. E.; Iyer, M.; Zuchero, J. B.; Teegen, B.; Dunn, J. E.; Lock, C. B.; Kipp, L. B.; Robinson, W. H. Clonally expanded B-cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Shen, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Y.; Gao, F. B-cell targeted therapies in autoimmune encephalitis: mechanisms, clinical applications, and therapeutic potential. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, 1368275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comi, G.; Bar-Or, A.; Lassmann, H.; Uccelli, A.; Hartung, H.; Montalban, X.; Sørensen, P. S.; Hohlfeld, R.; Hauser, S. L. Role of B-cells in Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. Annals of Neurology 2021, 89, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadelain, M.; Brentjens, R.; Rivière, I. The Basic Principles of Chimeric Antigen Receptor Design. Cancer Discovery 2013, 3, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Tsunei, A.; Kusabuka, H.; Ogaki, E.; Tachibana, M.; Okada, N. Hinge and Transmembrane Domains of Chimeric Antigen Receptor Regulate Receptor Expression and Signaling Threshold. Cells 2020, 9, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate-Daga, D.; Davila, M. L. CAR models: next-generation CAR modifications for enhanced T-cell function. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 2016, 3, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, A. J.; Jenkins, M. R. Programming a serial killer: CAR T cells form non-classical immune synapses. Oncoscience 2018, 5, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benmebarek, M.-R.; Karches, C. H.; Cadilha, B. L.; Lesch, S.; Endres, S.; Kobold, S. Killing Mechanisms of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, S. A.; Packard, B. S.; Aebersold, P. M.; Solomon, D.; Topalian, S. L.; Toy, S. T.; Simon, P.; Lotze, M. T.; Yang, J. C.; Seipp, C. A.; Simpson, C.; Carter, C.; Bock, S.; Schwartzentruber, D.; Wei, J. P.; White, D. E. Use of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Interleukin-2 in the Immunotherapy of Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 1988, 319, 1676–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshhar, Z.; Waks, T.; Gross, G.; Schindler, D. G. Specific activation and targeting of cytotoxic lymphocytes through chimeric single chains consisting of antibody-binding domains and the gamma or zeta subunits of the immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1993, 90, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, H. M.; Lawson, A. D.; Bebbington, C. R.; Weir, A. N. Chimeric receptors providing both primary and costimulatory signalling in T cells from a single gene product. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 1998, 161, 2791–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milone, M. C.; Fish, J. D.; Carpenito, C.; Carroll, R. G.; Binder, G. K.; Teachey, D.; Samanta, M.; Lakhal, M.; Gloss, B.; Danet-Desnoyers, G.; Campana, D.; Riley, J. L.; Grupp, S. A.; June, C. H. Chimeric Receptors Containing CD137 Signal Transduction Domains Mediate Enhanced Survival of T Cells and Increased Antileukemic Efficacy In Vivo. Molecular Therapy 2009, 17, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, J.; Brentjens, R. J.; Gunset, G.; Rivière, I.; Sadelain, M. Human T-lymphocyte cytotoxicity and proliferation directed by a single chimeric TCRζ /CD28 receptor. Nature Biotechnology 2002, 20, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C. A.; Rouce, R.; Robertson, C. S.; Reyna, A.; Narala, N.; Vyas, G.; Mehta, B.; Zhang, H.; Dakhova, O.; Carrum, G.; Kamble, R. T.; Gee, A. P.; Mei, Z.; Wu, M.-F.; Liu, H.; Grilley, B.; Rooney, C. M.; Heslop, H. E.; Brenner, M. K.; Dotti, G. In Vivo Fate and Activity of Second- versus Third-Generation CD19-Specific CAR-T Cells in B Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas. Molecular Therapy 2018, 26, 2727–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hombach, A. A.; Rappl, G.; Abken, H. Arming Cytokine-induced Killer Cells With Chimeric Antigen Receptors: CD28 Outperforms Combined CD28–OX40 Super-stimulation. Molecular Therapy 2013, 21, 2268–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, M.; Abken, H. TRUCKs: the fourth generation of CARs. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 2015, 15, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewski, M.; Abken, H. TRUCKS, the fourth-generation CAR T cells: Current developments and clinical translation. ADVANCES IN CELL AND GENE THERAPY 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagoya, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Guo, T.; Anczurowski, M.; Wang, C.-H.; Saso, K.; Butler, M. O.; Minden, M. D.; Hirano, N. A novel chimeric antigen receptor containing a JAK–STAT signalling domain mediates superior antitumor effects. Nature Medicine 2018, 24, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogesch, P.; Dudek, S.; van Zandbergen, G.; Waibler, Z.; Anzaghe, M. The Role of Fc Receptors on the Effectiveness of Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, J. L.; Combs, D.; Rosenberg, J.; Levy, A.; McDermott, M.; Damon, L.; Ignoffo, R.; Aldape, K.; Shen, A.; Lee, D.; Grillo-Lopez, A.; Shuman, M. A. Rituximab therapy for CNS lymphomas: targeting the leptomeningeal compartment. Blood 2003, 101, 466–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, C. M. Oligoclonal bands: An immunological and clinical approach. Advances in Clinical Chemistry 2022, 109, 129–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magliozzi, R.; Howell, O.; Vora, A.; Serafini, B.; Nicholas, R.; Puopolo, M.; Reynolds, R.; Aloisi, F. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain 2006, 130, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, B.; Ransohoff, R. M. Capture, crawl, cross: the T cell code to breach the blood–brain barriers. Trends in Immunology 2012, 33, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choquet, S.; Soussain, C.; Azar, N.; Morel, V.; Metz, C.; Ursu, R.; Waultier-Rascalou, A.; di Blasi, R.; Houot, R.; Souchet, L.; Roos-Weil, D.; Uzunov, M.; Quoc, S. N.; Jacque, N.; Boussen, I.; Gauthier, N.; Ouzegdouh, M.; Blonski, M.; Campidelli, A.; Houillier, C. CAR T-cell therapy induces a high rate of prolonged remission in relapsed primary CNS lymphoma: Real-life results of the LOC network. American Journal of Hematology 2024, 99, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Kipp, M.; Han, W.; Kaddatz, H. Ectopic lymphoid follicles in progressive multiple sclerosis: From patients to animal models. Immunology 2021, 164, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai Santhosha Mrudula, A.; Avula, N. L. P.; Ahmed, S. K.; Salian, R. B.; Alla, D.; Jagannath, P.; Polasu, S. S. S. P.; Rudra, P.; Issaka, Y.; Khetan, M. S.; Gupta, T. Immunological outcomes of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Annals of Medicine & Surgery 2024, 86, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackensen, A.; Müller, F.; Mougiakakos, D.; Böltz, S.; Wilhelm, A.; Aigner, M.; Völkl, S.; Simon, D.; Kleyer, A.; Munoz, L.; Kretschmann, S.; Kharboutli, S.; Gary, R.; Reimann, H.; Rösler, W.; Uderhardt, S.; Bang, H.; Herrmann, M.; Ekici, A. B.; Schett, G. Anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 2124–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegler, E. L.; Kenderian, S. S. Neurotoxicity and Cytokine Release Syndrome After Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy: Insights Into Mechanisms and Novel Therapies. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, E. C.; Neelapu, S. S.; Giavridis, T.; Sadelain, M. Cytokine release syndrome and associated neurotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Immunology 2022, 22, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavriilaki, E.; Tzannou, I.; Vardi, A.; Tsonis, I.; Liga, M.; Gkirkas, K.; Ximeri, M.; Bousiou, Z.; Bouzani, M.; Sagiadinou, E.; Dolgyras, P.; Kotsiou, N.; Bampali, V.; Mallouri, D.; Tzenou, T.; Batsis, I.; Sotiropoulos, D.; Gigantes, S.; Papadaki, H. A.; Sakellari, I. Management strategies for CAR-T cell therapy-related toxicities: results from a survey in Greece. Frontiers in Medicine 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, J.; Bachy, E.; Cartron, G.; Beauvais, D.; Gastinne, T.; di Blasi, R.; Rubio, M.-T.; Guidez, S.; Mohty, M.; Casasnovas, R.-O.; Joris, M.; Castilla-Llorente, C.; Haioun, C.; Hermine, O.; Loschi, M.; Carras, S.; Bories, P.; Fradon, T.; Herbaux, C.; Houot, R. Non relapse mortality after CAR T-cell therapy for large B-cell lymphoma: a LYSA study from the DESCAR-T registry. Blood Advances 2023, 7, 6589–6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, F.; Taubmann, J.; Bucci, L.; Wilhelm, A.; Bergmann, C.; Völkl, S.; Aigner, M.; Rothe, T.; Minopoulou, I.; Tur, C.; Knitza, J.; Kharboutli, S.; Kretschmann, S.; Vasova, I.; Spoerl, S.; Reimann, H.; Munoz, L.; Gerlach, R. G.; Schäfer, S.; Schett, G. CD19 CAR T-Cell Therapy in Autoimmune Disease — A Case Series with Follow-up. New England Journal of Medicine 2024, 390, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R. A.; Yang, J. C.; Kitano, M.; Dudley, M. E.; Laurencot, C. M.; Rosenberg, S. A. Case Report of a Serious Adverse Event Following the Administration of T Cells Transduced With a Chimeric Antigen Receptor Recognizing ERBB2. Molecular Therapy 2010, 18, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, V.; Savoldo, B.; Quintarelli, C.; Mahendravada, A.; Zhang, M.; Vera, J.; Heslop, H. E.; Rooney, C. M.; Brenner, M. K.; Dotti, G. Engineering CD19-specific T lymphocytes with interleukin-15 and a suicide gene to enhance their anti-lymphoma/leukemia effects and safety. Leukemia 2010, 24, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala Ceja, M.; Khericha, M.; Harris, C. M.; Puig-Saus, C.; Chen, Y. Y. CAR-T cell manufacturing: Major process parameters and next-generation strategies. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2024, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, M. M.; Stamatis, C.; Lakelin, M.; Farid, S.; Titchener-Hooker, N.; Shah, N. Autologous CAR T-cell therapies supply chain: challenges and opportunities? Cancer Gene Therapy 2020, 27, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J. A.; Luznik, L. This CAR won’t start: predicting nonresponse in ALL. Blood Advances 2023, 7, 4215–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Chyra, Z.; Kotulová, J.; Celichowski, P.; Mihályová, J.; Charvátová, S.; Hájek, R. Impact of T cell characteristics on CAR-T cell therapy in hematological malignancies. Blood Cancer Journal 2024, 14, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P. H.; Fiorenza, S.; Koldej, R. M.; Jaworowski, A.; Ritchie, D. S.; Quinn, K. M. T Cell Fitness and Autologous CAR T Cell Therapy in Haematologic Malignancy. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 780442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, C.; Jozwik, A.; Pepper, A.; Benjamin, R. Allogeneic CAR-T Cells: More than Ease of Access? Cells 2018, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Liu, M.; Lyu, C.; Lu, W.; Cui, R.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Mou, N.; Deng, Q.; Yang, D. Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease After Humanized Anti-CD19-CAR T Therapy in Relapsed B-ALL Patients After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 10, 573822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuis, J. P.; Nicole, O.; Groc, L. NMDA receptor functions in health and disease: Old actor, new dimensions. Neuron 2023, 111, 2312–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, E. G.; Peng, X.; Gleichman, A. J.; Lai, M.; Zhou, L.; Tsou, R.; Parsons, T. D.; Lynch, D. R.; Dalmau, J.; Balice-Gordon, R. J. Cellular and Synaptic Mechanisms of Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis. The Journal of Neuroscience 2010, 30, 5866–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, J.; Lancaster, E.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; Rosenfeld, M. R.; Balice-Gordon, R. Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. The Lancet Neurology 2011, 10, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titulaer, M. J.; McCracken, L.; Gabilondo, I.; Armangué, T.; Glaser, C.; Iizuka, T.; Honig, L. S.; Benseler, S. M.; Kawachi, I.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; Aguilar, E.; Gresa-Arribas, N.; Ryan-Florance, N.; Torrents, A.; Saiz, A.; Rosenfeld, M. R.; Balice-Gordon, R.; Graus, F.; Dalmau, J. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. The Lancet Neurology 2013, 12, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Yue, Y.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor hypofunction as a potential contributor to the progression and manifestation of many neurological disorders. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2023, 16, 1174738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]