Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

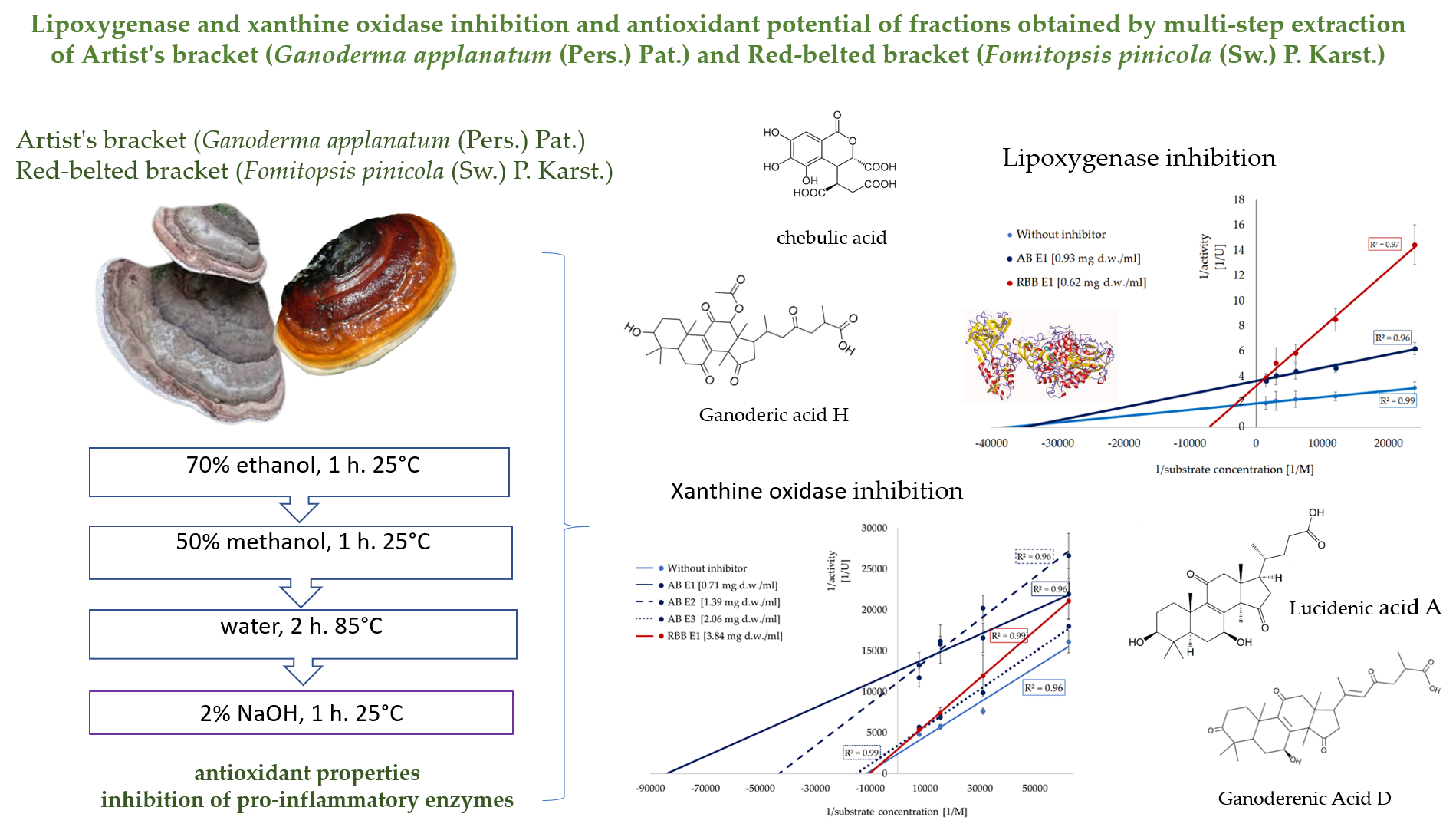

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.1.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.1.2. Preparation of Musroom Extracts

2.2. Analytical Procedures

2.2.1. Analysis of Bioactive Compounds

2.2.1.1. The Folin-Ciocalteau Reacting Substances (FC-Reacting Substances)

2.2.1.2. Total Terpenoids and Sterols

2.2.1.3. Saccharides

2.2.1.4. Untargeted Metabolomics

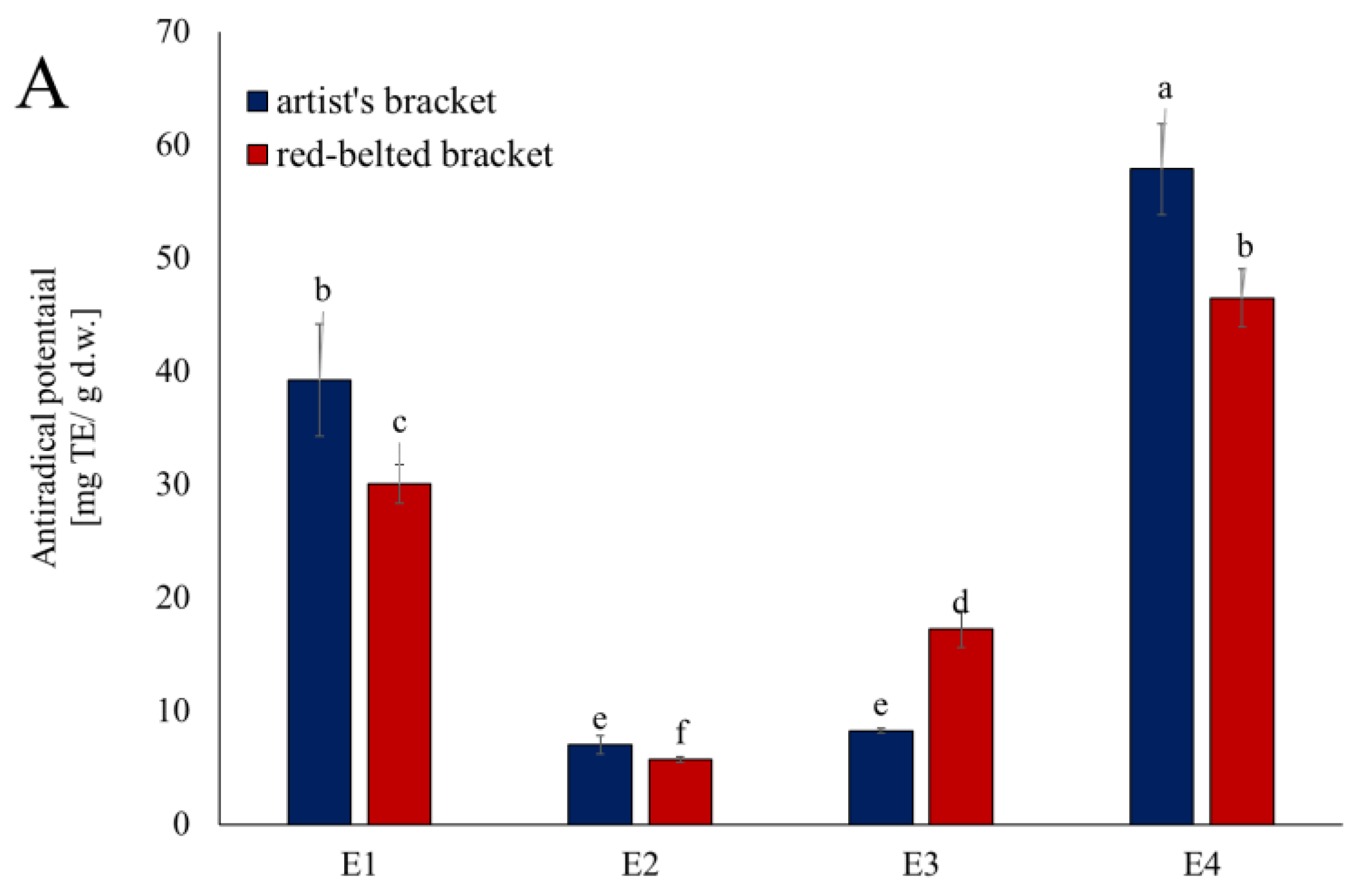

2.3.1. Antioxidant Properties

2.3.1.1. Antiradical Properties (ABTS)

2.3.1.2. Ferric Reducing Power (RP)

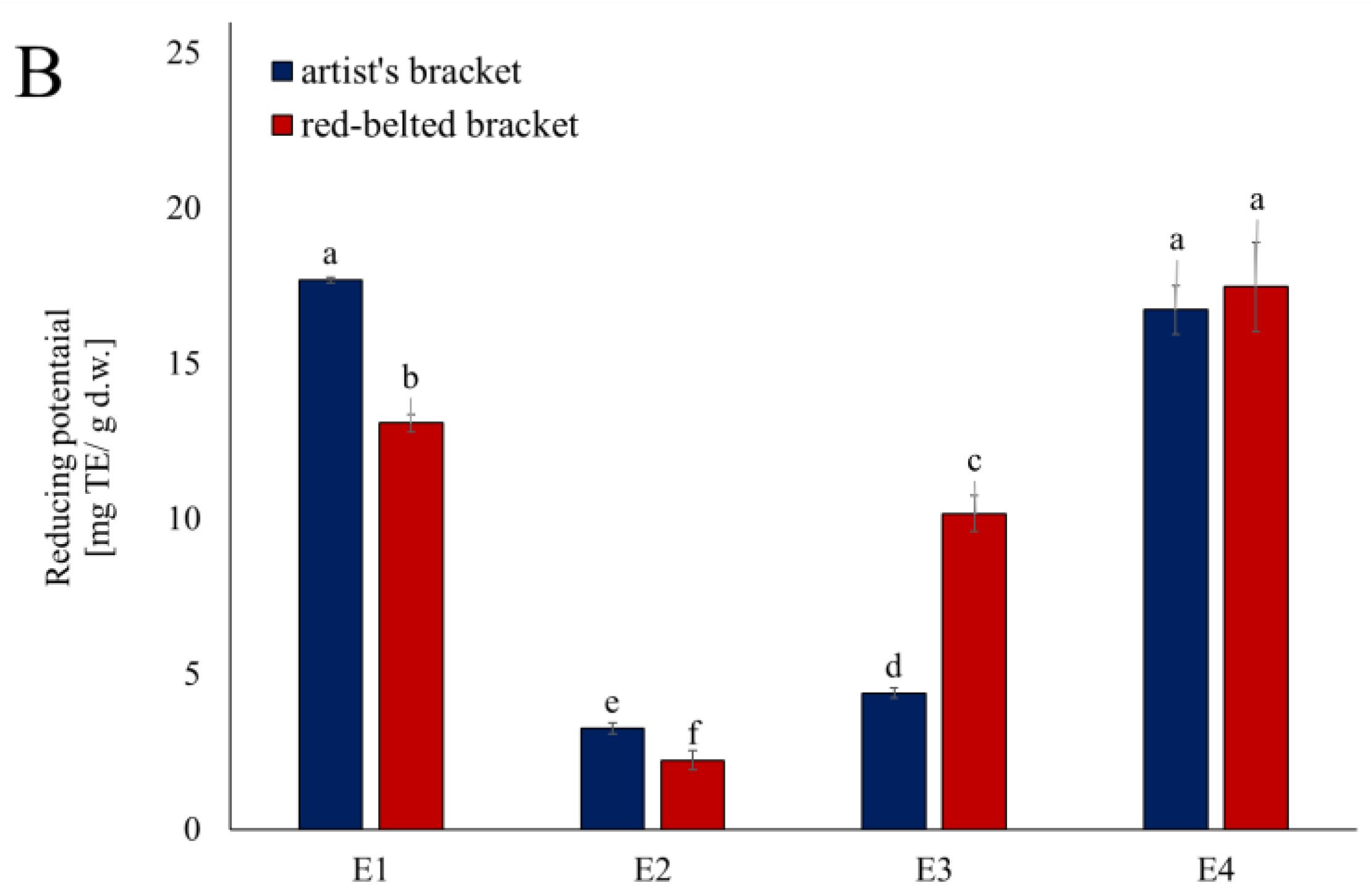

2.4.1. Anti-Inflammatory Properties

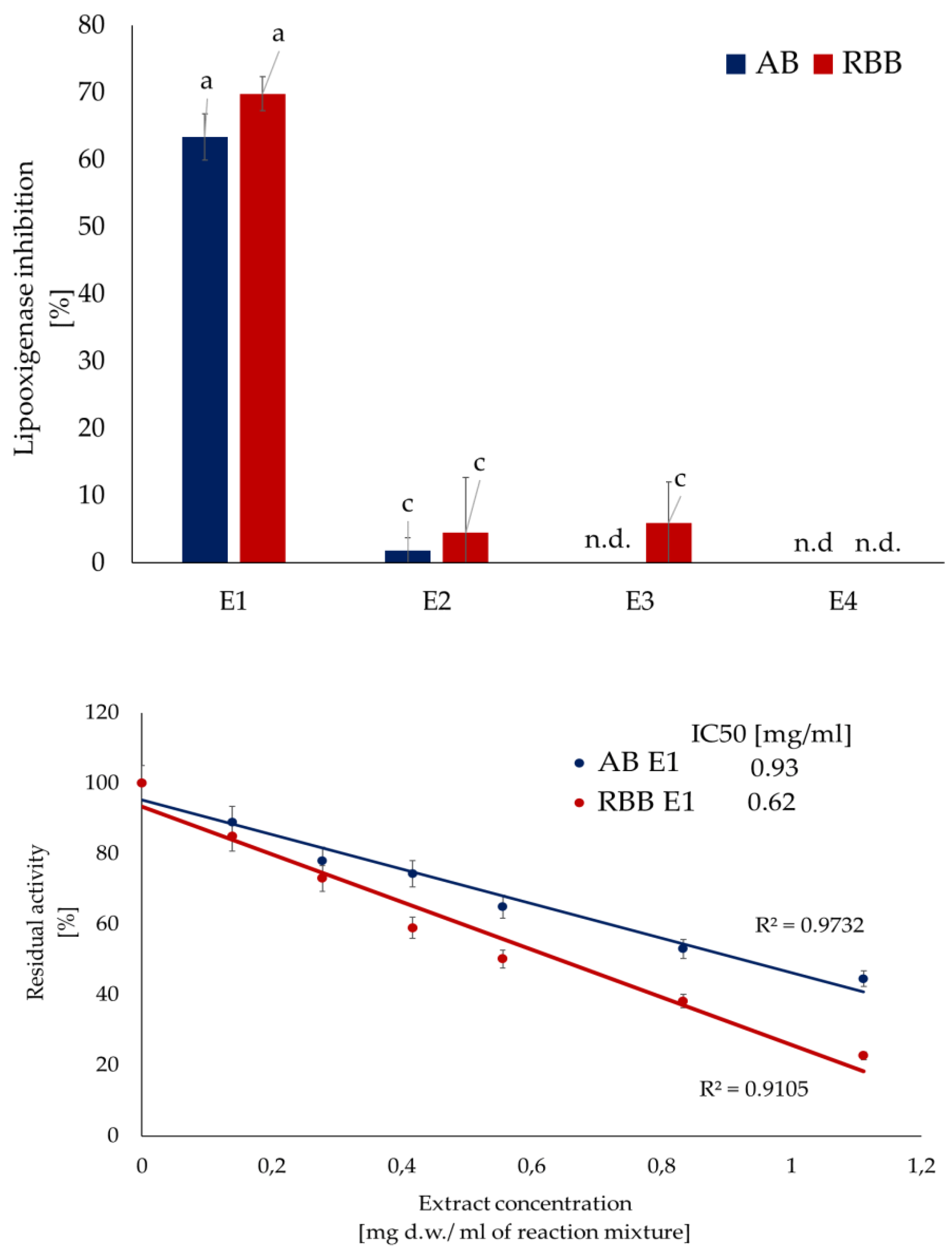

2.4.1.1. Ability to Inhibit Xanthine Oxidase Activity (LOXI)

2.4.1.2. Ability to Inhibit Xanthine Oxidase Activity (XOI)

2.4.1.3. Determination of IC50 Values and the Mode of Inhibition.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Multi-Step Extraction on the Main Active Constituents and Antioxidant Properties

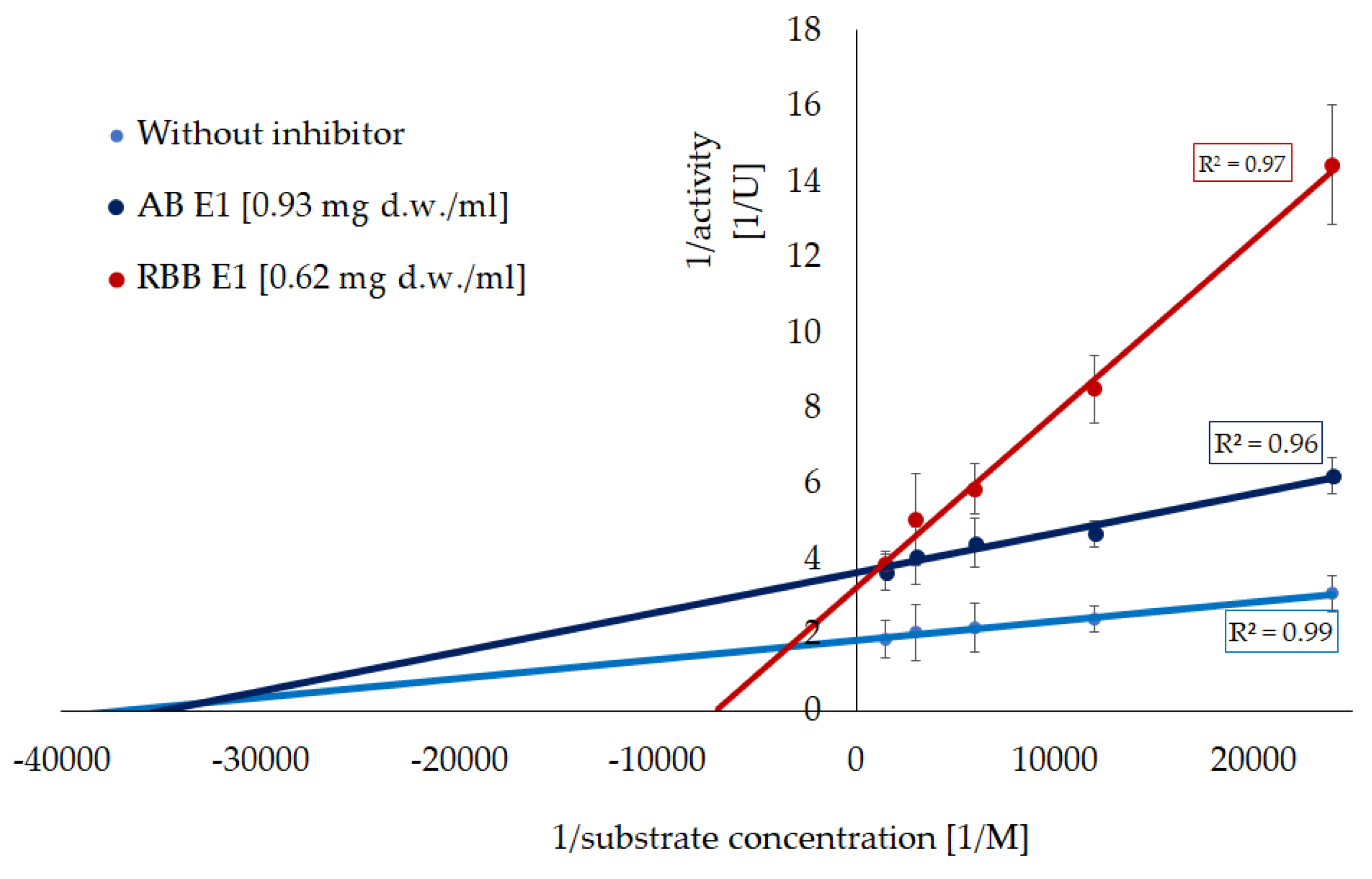

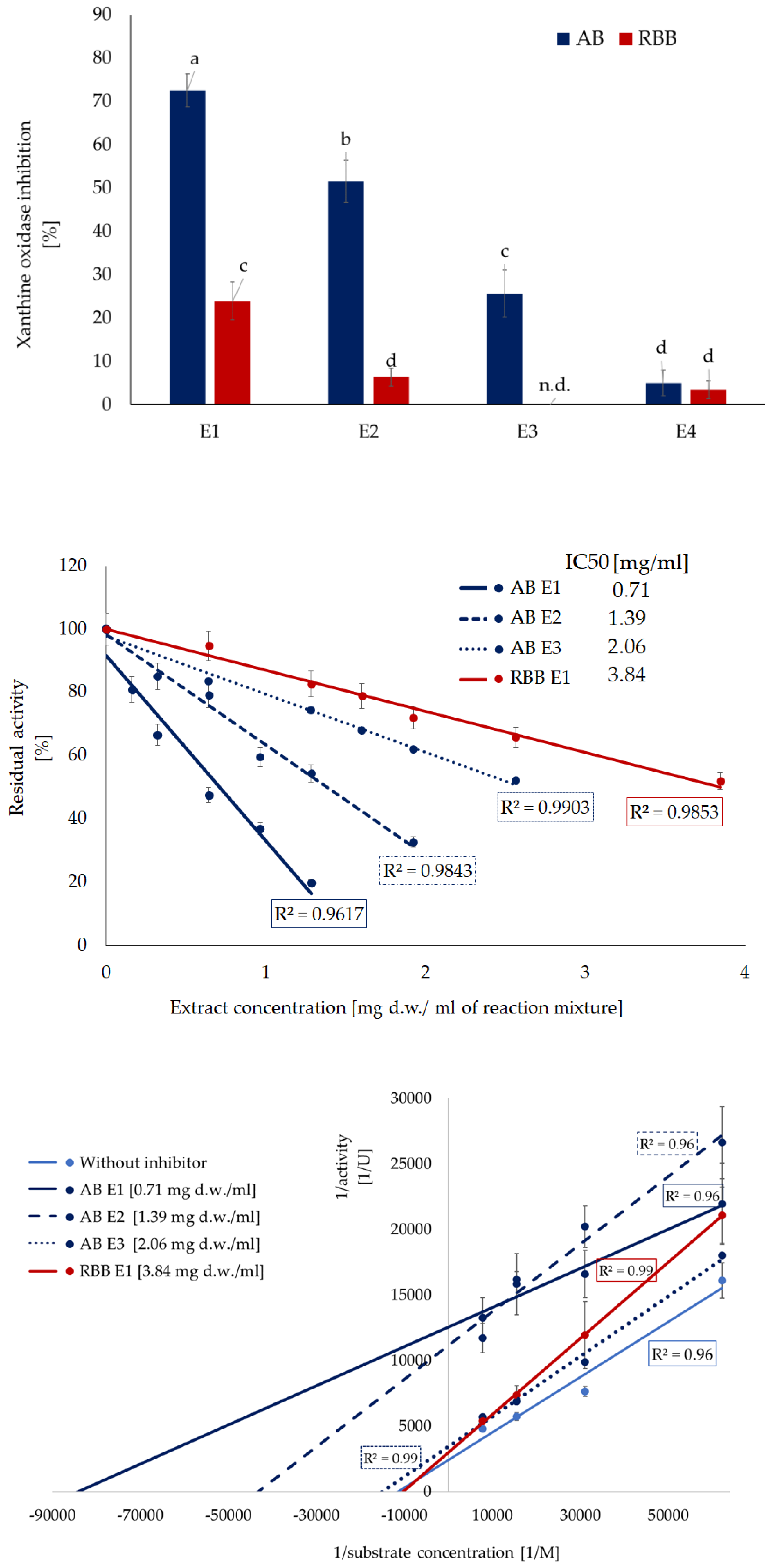

3.2. Effect of Multi-Step Extraction on the Anti-Inflammatory Properties – Inhibition of Lipoxygenase and Xanthine Oxidase

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bell, V.; Silva, C.R.P.G.; Fernandes, T.H. Mushrooms as Future Generation Healthy Foods. Front Nutr 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysakowska, P.; Sobota, A.; Wirkijowska, A. Medicinal Mushrooms: Their Bioactive Components, Nutritional Value and Application in Functional Food Production—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Mehra, R.; Guiné, R.P.F.; Lima, M.J.; Kumar, N.; Kaushik, R.; Ahmed, N.; Yadav, A.N.; Kumar, H. Edible Mushrooms: A Comprehensive Review on Bioactive Compounds with Health Benefits and Processing Aspects. Foods 2021, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalska, A.; Sierocka, M.; Drzewiecka, B.; Świeca, M. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Mushroom-Based Food Additives and Food Fortified with Them—Current Status and Future Perspectives. Antioxidants 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Disease; Elsevier Inc., 2016; ISBN 9780128032701. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Ma, S. Recent Development of Lipoxygenase Inhibitors as Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Medchemcomm 2018, 9, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katiyar, D.; Ghosh, D.; Singh, R.; Dixit, S.; Chopra, S.; Tripathi, S.; Saini, T. Medicinal Mushrooms: Bioactive Components, Pharmacological, Immunological and Toxicological Insights. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. fa; Wu, C.; Wang, M.; Chen, J. fei; Lv, G. ying Chemical Fingerprinting and the Biological Properties of Extracts from Fomitopsis Pinicola. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosecke, J.; Konig, W.A. Steroids from the Fungus Fomitopsis Pinicola. Phytochemistry 1999, 1621–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.C.; Tai, S.H.; Hung, C.C.; Hwang, T.L.; Kuo, L.M.; Lam, S.H.; Cheng, K.C.; Kuo, D.H.; Hung, H.Y.; Wu, T.S. Antiinflammatory Triterpenoids from the Fruiting Bodies of Fomitopsis Pinicola. Bioorg Chem 2021, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, Q.; Xu, T.C.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W.F.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, D.L.; Jin, P.F.; et al. Bioactive Terpenoids and Sterols from the Fruiting Bodies of Fomitopsis Pinicola. Phytochemistry 2025, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadifar, S.; Fallahi Gharaghoz, S.; Reza, M.; Shayan, A.; Vaziri, A. Comparison between Antioxidant Activity and Bioactive Compounds of Ganoderma Applanatum (Pers.) Pat. and Ganoderma Lucidum (Curt.) P. Karst from Iran. Vol. 11.

- Liu, L.; Wei, L.; Xu, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhou, S.; Ma, S.; Sun, W.; Tian, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, Z. Molecular Identification and Quality Evaluation of Commercial Ganoderma. Medicinal Plant Biology 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Zengin, G.; Gunia-Krzyżak, A.; Popiół, J.; Szewczyk, A.; Jaszek, M.; Rogalski, J.; Muszyńska, B. Bioactivity and Mycochemical Profile of Extracts from Mycelial Cultures of Ganoderma Spp. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaranarayanan Ravikumar, K.; Ramya, H.; Ajith, T.A.; Janardhanan, K.K.; Shah, A.; Reshi, Z.A.; Andrabi, K.I. ANTIOXIDANT AND ANTI-INFLAMMATORY ACTIVITIES OF BIOACTIVE EXTRACTS OF A POLYPORE MUSHROOM, FOMITOPSIS PINICOLA (SW.:FR.) P. KARST, FROM KASHMIR. Int. J. Adv. Res 6 1144–1156. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, J.; Gao, H.; Xu, Y.; Han, Y.; Shang, H.; Lu, Y.; Qin, C. Ganoderma Lucidum Triterpenoids and Polysaccharides Attenuate Atherosclerotic Plaque in High-Fat Diet Rabbits. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2021, 31, 1929–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.H.; Choi, J.; Baek, S.A.; Lee, T.S. Journal of Mushrooms 한 국 버 섯 학 회 지 Antioxidant and Inflammation Inhibitory Effects from Fruiting Body Extracts of Ganoderma Applanatum. J. Mushrooms 2021, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, K.S. Characterisation of Extracts and Anti-Cancer Activities of Fomitopsis Pinicola. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.J.; Lin, C.Y.; Lur, H.S.; Chen, H.P.; Lu, M.K. Properties and Biological Functions of Polysaccharides and Ethanolic Extracts Isolated from Medicinal Fungus, Fomitopsis Pinicola. Process Biochemistry 2008, 43, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, M. Antioxidant/Anti-Inflammatory Activities and Chemical Composition of Extracts from the Mushroom Trametes Versicolor. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences 2013, 2, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska, A.; Szymanowska, U.; Kapusta, I.; Żurek, N.; Nawrocka, A.; Różyło, R.; Jarocki, P.; Świeca, M. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antiproliferative Properties of Extracted Turkey Tail (Trametes Versicolor Lloyd) Mushroom Components Microencapsulated with Inulin. Food Chem 2025, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, S.C.; Patabendige, N.M.; Kumla, J.; Hapuarachchi, K.K.; Suwannarach, N. The Bioactive Compounds, Beneficial Medicinal Properties, and Biotechnological Prospects of Fomitopsis: A Comprehensive Overview. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katiyar, D.; Ghosh, D.; Singh, R.; Dixit, S.; Chopra, S.; Tripathi, S.; Saini, T. Medicinal Mushrooms: Bioactive Components, Pharmacological, Immunological and Toxicological Insights. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. Methods Enzymol 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.L.; Lin, C.S.; Lai, G.H. Phytochemical Characteristics, Free Radical Scavenging Activities, and Neuroprotection of Five Medicinal Plant Extracts. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2012, Article ID. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W. A Standardized Method for the Quantification of Polysaccharides: An Example of Polysaccharides from Tremella Fuciformis. Lwt 2022, 167, 113860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Kapusta, I.; Stinco, C.M.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Bieniek, A.; Ochmian, I.; Gil, Z. Distribution of Polyphenolic and Isoprenoid Compounds and Biological Activity Differences between in the Fruit Skin + Pulp, Seeds, and Leaves of New Biotypes of Elaeagnus Multiflora Thunb. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, R.P.; Dandamudi, R.B.; Patnana, D.P.; Pandey, M.; Vutukuri, V.N.R.K. Metabolic Fingerprinting of Ganoderma Spp. Using UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS and Its Chemometric Analysis. Phytochemistry 2022, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhateeb, W.A.; Zaghlol, G.M.; El-Garawani, I.M.; Ahmed, E.F.; Rateb, M.E.; Abdel Moneim, A.E. Ganoderma Applanatum Secondary Metabolites Induced Apoptosis through Different Pathways: In Vivo and in Vitro Anticancer Studies. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2018, 101, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, K.S.; Ramya, H.; Ajith, T.A.; Shah, M.A.; Janardhanan, K.K. Bioactive Extract of Fomitopsis Pinicola Rich in 11-α- Acetoxykhivorin Mediates Anticancer Activity by Cytotoxicity, Induction of Apoptosis, Inhibition of Tumor Growth, Angiogenesis and Cell Cycle Progression. J Funct Foods 2021, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Liang, J.; Han, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, R.; Liu, H.; Dai, H. Lanostane Triterpenoids with PTP1B Inhibitory and Glucose-Uptake Stimulatory Activities from Mushroom Fomitopsis Pinicola Collected in North America. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68, 10036–10049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oludemi, T.; Barros, L.; Prieto, M.A.; Heleno, S.A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Extraction of Triterpenoids and Phenolic Compounds from: Ganoderma Lucidum: Optimization Study Using the Response Surface Methodology. Proceedings of the Food and Function 2018, Vol. 9, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiseleva, I.; Ermoshin, A.; Galishev, B.; Shen, D. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Fomitopsis Pinicola Growing on Coniferous and Deciduous Substrates.

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyaizu, M. Studies on Products of Browning Reaction – Antioxidative Activities of Products of Browning Reaction Prepared from Glucosamine. Japanese Journal of Nutrition 1986, 44, 307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Dziki, D.; Świeca, M.; Nowak, R. Mechanism of Action and Interactions between Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors Derived from Natural Sources of Chlorogenic and Ferulic Acids. Food Chem 2017, 225, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lineweaver, H.; Burk, D. The Determination of Enzyme Dissociation Constants. J Am Chem Soc 1934, 56, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, C.; Singh, B.P.; Kamal, S.; Ram, H.; Oberoi, H.S.; Mostashari, P.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Advancements in Extraction and Encapsulation of Immunomodulatory Mushroom Biomolecules for Enhanced Food Applications. Applied Food Research 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Sarikurkcu, C.; Gunes, E.; Uysal, A.; Ceylan, R.; Uysal, S.; Gungor, H.; Aktumsek, A. Two Ganoderma Species: Profiling of Phenolic Compounds by HPLC-DAD, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Inhibitory Activities on Key Enzymes Linked to Diabetes Mellitus, Alzheimer’s Disease and Skin Disorders. Food Funct 2015, 6, 2794–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Nagadesi, P.; Kannamba, B. Effect of Extraction and Solvent on Mycochemicals and Proximate Composition of Lignicolous Fungi Ganoderma Lucidum and G. Applanatum: A Comparative Study. SCIREA Journal of Pharmacy 2019, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Onar, O.; Akata, I.; Celep, G.S.; Yildirim, O. Antioxidant Activity of Extracts from the Red-Belt Conk Medicinal Mushroom, Fomitopsis Pinicola (Agaricomycetes), and Its Modulatory Effects on Antioxidant Enzymes. Int J Med Mushrooms 2016, 18, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Nikšić, M.; Vrvić, M.M.; Todorović, N.; Jakovljević, D.; Van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antioxidative Activities and Chemical Characterization of Polysaccharide Extracts from the Widely Used Mushrooms Ganoderma Applanatum, Ganoderma Lucidum, Lentinus Edodes and Trametes Versicolor. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2012, 26, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Popović, M.; Beara, I.; Šibul, F.; Zengin, G.; Krstić, S.; Karaman, M. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant and Enzyme Inhibition Activities in Correlation with Mycochemical Profile of Selected Indigenous Ganoderma Spp. from Balkan Region (Serbia). Chem Biodivers 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Karaman, M.; Jakšić, M.; Šibul, F.; Kebert, M.; Novaković, A.; Popović, M. Mineral Composition, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Biopotentials of Wild-Growing Ganoderma Species (Serbia): G. Lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst vs. G. Applanatum (Pers.) Pat. Int J Food Sci Technol 2016, 51, 2583–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Muszyńska, B.; Motyl, P.; Pasko, P.; Ekiert, H. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Some Species of Polyporoid Mushrooms from Poland. 2012, Vol. 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-Y.; Li, S.-Y.; Yin, F.; Chen, H.-M.; Yang, D.-F.; Liu, X.-Q.; Jin, Q.-H.; Lv, X.-M.; Mans, D.; Zhang, X.-D.; et al. Antioxidative and Cytoprotective Effects of Ganoderma Applanatum and Fomitopsis Pinicola in PC12 Adrenal Phaeochromocytoma Cells. Int J Med Mushrooms 2022, 24, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.; Song, J.G.; Hwang, B.S.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, Y.J.; Woo, E.E.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, I.K.; Yun, B.S. Lipoxygenase Inhibitory Activity of Korean Indigenous Mushroom Extracts and Isolation of an Active Compound from Phellinus Baumii. Mycobiology 2014, 42, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C. Efficient and Fast Screening and Separation Based on Computer-aided Screening and Complex Chromatography Methods for Lipoxygenase Inhibitors from. Phytochemical Analysis 2024, 35, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ványolõs, A.; Orbán-Gyapai, O.; Hohmann, J. Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Activity of Hungarian Wild-Growing Mushrooms. Phytotherapy Research 2014, 28, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.S.; Kim, S.H.; Sa, J.H.; Jin, C.; Lim, C.J.; Park, E.H. Anti-Angiogenic, Antioxidant and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition Activities of the Mushroom Phellinus Linteus. J Ethnopharmacol 2003, 88, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B.; Valentão, P.; Baptista, P.; Seabra, R.M.; Andrade, P.B. Phenolic Compounds, Organic Acids Profiles and Antioxidative Properties of Beefsteak Fungus (Fistulina Hepatica). Food and Chemical Toxicology 2007, 45, 1805–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Yoon, K.N.; Lee, K.R.; Kim, H.Y.; Shin, P.G.; Cheong, J.C.; Yoo, Y.B.; Shim, M.J.; Lee, M.W.; Lee, T.S. Assessment of Antioxidant and Phenolic Compound Concentrations as Well as Xanthine Oxidase and Tyrosinase Inhibitory Properties of Different Extracts of Pleurotus Citrinopileatus Fruiting Bodies. Mycobiology 2011, 39, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Špirović-Trifunović, B.; Miletić, S.; Lazić, V.; Žižak, Ž.; Vunduk, J. Bioprospecting of Selected Species of Polypore Fungi from the Western Balkans. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Nikšić, M.; Vrvić, M.M.; Todorović, N.; Jakovljević, D.; Van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antioxidative Activities and Chemical Characterization of Polysaccharide Extracts from the Widely Used Mushrooms Ganoderma Applanatum, Ganoderma Lucidum, Lentinus Edodes and Trametes Versicolor. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2012, 26, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łyko, L.; Olech, M.; Gawlik, U.; Krajewska, A.; Kalemba, D.; Tyśkiewicz, K.; Piórecki, N.; Prokopiv, A.; Nowak, R. Rhododendron Luteum Sweet Flower Supercritical CO2 Extracts: Terpenes Composition, Pro-Inflammatory Enzymes Inhibition and Antioxidant Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habza-Kowalska, E.; Kaczor, A.A.; Bartuzi, D.; Piłat, J.; Gawlik-Dziki, U. Some Dietary Phenolic Compounds Can Activate Thyroid Peroxidase and Inhibit Lipoxygenase-Preliminary Study in the Model Systems. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouriche, H.; Miles, E.A.; Selloum, L.; Calder, P.C. Effect of Cleome Arabica Leaf Extract, Rutin and Quercetin on Soybean Lipoxygenase Activity and on Generation of Inflammatory Eicosanoids by Human Neutrophils. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2005, 72, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Chang, Y.Y.; Chang, S.T.; Chang, H.T. Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Activity and Chemical Composition of Pistacia Chinensis Leaf Essential Oil. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, S.H.; Kuo, P.C.; Hung, C.C.; Lin, Y.H.; Hwang, T.L.; Lam, S.H.; Kuo, D.H.; Wu, J. Bin; Hung, H.Y.; Wu, T.S. Bioassay-Guided Purification of Sesquiterpenoids from the Fruiting Bodies of: Fomitopsis Pinicola and Their Anti-Inflammatory Activity. RSC Adv 2019, 9, 34184–34195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amagata, T.; Whitman, S.; Johnson, T.A.; Stessman, C.C.; Loo, C.P.; Lobkovsky, E.; Clardy, J.; Crews, P.; Holman, T.R. Exploring Sponge-Derived Terpenoids for Their Potency and Selectivity against 12-Human, 15-Human, and 15-Soybean Lipoxygenases. J Nat Prod 2003, 66, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.W.; Chen, Y.T.; Yang, S.C.; Wei, B.L.; Hung, C.F.; Lin, C.N. Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Lanostanoids from Ganoderma Tsugae. Fitoterapia 2013, 89, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, S.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, W. Comprehensive Screening, Separation, Extraction Optimization, and Bioactivity Evaluation of Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors from Ganoderma Leucocontextum. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2025, 18, 132024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Artist’s bracket | Red-belted bracket | ||

|

FC-reacting substances [mg GAE/ g d.w.] |

E1 | 10.08 ± 0.12 a | 8.11 ± 0.17 b |

| E2 | 1.82 ± 0.04 g | 5.96 ± 0.19 c | |

| E3 | 2.45 ± 0.09 f | 5.07 ± 0.05 d | |

| E4 | 4.28 ± 0.11 e | 10.15 ± 0.11 a | |

| Sum | 18.63 | 29.29 | |

|

Total terpenoids and sterols [mg UAE/ g d.w.] |

E1 | 29.97 ± 1.23 b | 61.51 ± 2.61 a |

| E2 | 2.22 ± 0.22 e | 6.75 ± 0.39 d | |

| E3 | 2.58 ± 0.48 e | 4.98 ± 0.83 d | |

| E4 | 5.09 ± 0.26 d | 14.41 ± 0.34 c | |

| Sum | 39.86 | 87.64 | |

| Mono- and oligosaccharides [mg GluE/ g d.w.] | E1 | 53.28 ± 2.08 b | 50.44 ± 3.03 b |

| E2 | 7.15 ± 1.33 e | 4.75 ± 0.95 e | |

| Sum | 60.42 | 55.24 | |

| Polysaccharides [mg GluE/ g d.w.] |

E3 | 28.73 ± 0.92 c | 19.18 ± 1.86 d |

| E4 | 77.70 ± 0.68 a | 27.18 ± 2.03 c | |

| Sum | 106.4 | 46.4 |

| Without inhibitor | Artist’s bracket | Red-belted bracket | |

| Vmax/Vmaxi [mU] | 536 ± 14.1 a | 274 ± 16.6 b | 272 ± 17.7 b |

| Km/Kmi [μM] | 26.8 ± 0.70 b | 231.7 ± 1.66 a | 27.4 ± 2.94 b |

| Mode of inhibition | - | mixed | noncompetitive |

| kcat [s-1) | 8.40 × 108 a | 4.29 × 108 b | 4.26 × 108 b |

| Without inhibitor | Artist’s bracket | Red-belted bracket | |||

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E1 | ||

| Vmax/Vmaxi [U] | 0.415 ± 0.023 a | 0.080 ± 0.010 d | 0.090 ± 0.010 d | 0.292 ± 0.017 c | 0.335 ± 0.026 b |

| Km/Kmi [μM] | 87.7 ± 4.8 | 11.9 ± 1.5 | 23.1 ± 0.0 | 67.0 ± 0.0 | 97.2 ± 7.6 |

| Mode of inhibition | - | acompetitive | acompetitive | acompetitive | noncompetitive |

| kcat [s-1] | 0.072 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.051 | 0.058 |

| Red-belted bracket | ||||||

| Compound | Rt | λmax | [M-H] m/z | μg/ g d.w. | ||

| min | nm | MS | MS/MS | |||

| Phenolics | ||||||

| 1. | Vanillic acid | 1.67 | 274 | 167- | 123 | 5.02 ± 0.054 |

| 2. | Protocatechuic acid | 1.76 | 259, 300 | 153- | 109 | 2.26 ± 0.068 |

| 3. | Sinapic acid | 1.92 | 324 | 223- | 164 | 1.81 ± 0.042 |

| 4. | Quercetin 3-O-rutinoside | 2.45 | 255, 355 | 609- | 301 | 1.40 ± 0.013 |

| 5. | Rosmarinic acid glucoside | 2.70 | 324 | 521- | 359 | 1.23 ± 0.013 |

| 6 | Ferulic acid | 2.87 | 327 | 193- | 134 | 3.39 ± 0.074 |

| 7. | Chebulic acid | 2.93 | 320, 402 | 355- | 337, 261 | 5.92 ± 0.104 |

| Terpenes | ||||||

| 8. | 6-α-hydroxy-3,16-dioxolanosta-7(8),9(11), ,24-trien-21-oic acid |

6.43 | - | 481- | 463, 437, 403, 388, 373 | 3.43 ± 0.040 |

| 9. | Dehydrotumulosic acid | 6.55 | - | 483- | 465, 421, 255 | 1.36 ± 0.045 |

| 10. | 16-α-hydroxy-3, oxolanosta-7,9(11),24- -trien-21-oic acid |

6.60 | - | 467- | 423, 407, 389, 373, 311 | 2.20 ± 0.004 |

| 11. | Irpeksolactin E | 6.64 | - | 485- | 467, 423, 407, 353, 337 | 2.90 ± 0.012 |

| 12. | Forpinic acid D | 6.85 | - | 479- | 465, 435, 441 | 1.98 ± 0.014 |

| 13. | Forpinic acid E | 6.98 | - | 495- | 465, 421, 405, 391, 373 | 1.15 ± 0.014 |

| 14. | 16-α-hydroxy-dehydrotraumetenolic acid | 7.06 | - | 469- | 467, 425, 409, 391, 337 | 2.71 ± 0.017 |

| 15. | Unspecified | 7.38 | - | 467- | - | 5.27 ± 0.032 |

| 16. | Formipiniate B | 7.43 | - | 525- | 497, 483, 465, 441 | 2.48 ± 0.037 |

| 17. | Forpinic acid A | 8.52 | - | 599- | 537, 455 | 2.44 ± 0.057 |

| 18. | 20-OH-lucidenic acid A | 8.60 | - | 455- | 149 | 1.56 ± 0.039 |

| 19. | Forpinic acid F | 8.68 | - | 639- | 537, 451, 371, 339 | 1.90 ± 0.007 |

| 20. | Forpinic acid G | 8.74 | - | 583- | 465, 449, 434, 389 | 20.9 ± 0.176 |

| 21. | Forpinic acid C | 8.79 | - | 541- | 451, 371, 339 | 12.0 ± 0.377 |

| 22. | Piptolinic acid D | 8.87 | - | 465- | 435, 421, 405, 369 | 1.97 ± 0.025 |

| 23. | Formipinic acid H | 9.00 | - | 627- | 537, 465, 373 | 3.52 ± 0.038 |

| 24. | Unspecified | 9.10 | - | 495- | - | 2.27 ± 0.068 |

| 25. | Formitopsic acid F | 9.22 | - | 527- | 479, 435, 419, 351 | 2.69 ± 0.062 |

| Artist’s bracket | ||||||

| Terpenes | ||||||

| 1. | Ganoderenic acid A | 4.38 | - | 513- | 495, 451, 249 | 7.78 ± 0.085 |

| 2. | Ganoderenic acid D | 4.75 | - | 511- | 493, 285, 149 | 2.10 ± 0.063 |

| 3. | Ganoderic acid C6 | 4.83 | - | 529- | 481, 467, 437 | 3.57 ± 0.082 |

| 4. | Ganoderic acid A | 4.93 | - | 515- | 497, 303, 2449 | 3.31 ± 0.031 |

| 5. | Ganoderic acid H | 6.93 | - | 571- | 511, 467, 437 | 3.15 ± 0.033 |

| 6. | Ganoderic acid F | 7.16 | - | 569- | 509, 465, 435 | 8.33 ± 0.183 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).