Introduction

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) is a disease that affects several tissue types, including the nervous system, and cell types including neurons[

1,

2,

3]. The underlying cause of TSC is inactivating mutations in the

TSC1 or

TSC2 genes found on chromosomes 9q34 and 16p13.3, respectively[

4,

5]. These mutations most often cause the loss of expression of the proteins encoded by

TSC1/TSC2 through nonsense and missense mutations, deletions, and large rearrangements[

9]. Loss of function of

TSC1/TSC2 causes unrestrained mTORC1 activity[

2]. TSC is considered an autosomal dominant disorder[

7]. Patients who are afflicted with TSC are frequently born with congenital malformations or develop growths called hamartomas[

1,

8]. Brain malformations are associated with a wide range of neurological manifestations[

9].

TSC is proposed to follow Alfred Knudson’s two-hit hypothesis wherein pathogenic mutations in one copy of the TSC genes may occur early in development or even be inherited from parents[

10,

11,

12]. However, “second-hit” mutations occur in the other normal (wild-type) copy of this gene. Knudson used the Eker rat, which has a germ-line transmissible

Tsc2 variant caused by a transposon-like insertion of an inactive 6,253 base pair intracisternal A-particle element containing multiple termination codons to demonstrate TSC growths adhere to the two-hit hypothesis[

13,

14]. This insertion is 3’ to the catalytic domain of the encoded protein Tuberin. Eker rats homozygous for this mutation fail to develop. However, 30-60% of heterozygous Eker rats develop CNS malformations that are reminiscent of those seen in patients[

15]. The prevalence and severity of brain hamartomas increases when Eker rats are exposed to radiation or mutagens[

16]. LOH and mTORC1 activation occur in these hamartomas[

17]. These results support the two-hit hypothesis as a mechanism that is sufficient to cause TSC malformations[

18,

19]. Forty-three heterozygous Eker rats subject to necropsy demonstrated that 100% have renal tumors, 48% have subependymal hamartomas, 21% have subcortical hamartomas, 33% have meningiomas, and 58% have pituitary adenomas[

15]. These results demonstrate that the

Tsc2 gene is critically required in numerous cell types of different brain regions consistent with the vast heterogeneity of lesions found in patients and support an evolutionarily conserved role of TSC genes. Hamartomas often arose within the striatum near the caudate nucleus reminiscent of subependymal nodules or subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGAs). More recently, the Eker rat has been revisited with demonstration of loss of neurons in the caudate, microglia activation, vasculature remodeling, gliosis, and increased neural stem cell marker expression[

20].

Given the location and timing of SEN/SEGA appearance, it has been hypothesized that LOH mutations in neural stem cells (NSCs) along the ventricular-subventricular zone might be the cause. Indeed, several animal models have explored this possibility with significant overlap in agreement with the appearance of SEGAs in the Eker model[

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. In one of these models, loss of

Tsc1 resulted in nodules along the lateral ventricles and large growths at the base of the lateral ventricles. This could be achieved by removing

Tsc1 from Nestin expressing NSCs or transit amplifying cells, an intermediate progenitor of the V-SVZ. These growths were accompanied by fewer olfactory bulb (OB) granule cells. Similar abnormalities including heterotopic clusters of cytomegalic neurons were produced by CRE electroporation and/or using

Tsc1 x

Nestin-CRE-ER

T2 mice. In another study,

Tsc1 and

PTEN were removed at P10 or P15-17 using

Nestin-CRE-ER

T2[

21]. Mice developed SEN-like and SEGA-like growths in ~1 month and shared overlapping histopathological features with patient SENs and SEGAs.

Loss of

TSC2 is, however, the most common genetic cause of SEGAs. Neonatal electroporation of conditional

Tsc2 mice with CRE recombinase caused the formation of both intraventricular anomalies and hamartomas within the boundaries of the V-SVZ and striatum[

22]. Fluorescent activated nuclei sorting (FANS) and single nuclei RNA sequencing demonstrated changes in NSC transitional states accompanied by the differential expression of stem and progenitor transcripts[

22,

26].

In vivo, neonatal lateral V-SVZ NSCs have high mTORC1 activity but generate striatal glia with low mTORC1 activity. Loss of

Tsc2 prevented glia from downregulating mTORC1 activity. As expected, aberrant translation of NSC proteins occurred. The striatal hamartomas can be partially rescued with Rapalink-1, a bisteric mTOR inhibitor, demonstrating the importance of mTOR in pathogenesis[

27].

We also crossed nestin-CRE-ER

T2 mice to conditional

Tsc2 mice and cultured mutant NSCs[

22]. Cultured NSCs had altered transcriptomes with differences in many ribosomal RNAs and translational regulatory RNAs. Predictably, NSC mRNA translational programs are also altered

in vitro. We further reported that OB granule cells from these mice have elevated mTORC1 activity and that the average soma size is enlarged[

28]. These changes were corroborated with the neonatal electroporation model. However, the V-SVZ from these same nestin-CRE-ER

T2 mice were not reported. Here, we provide corroborating evidence that loss of

Tsc2 from V-SVZ NSCs using nestin-CRE-ER

T2 mice causes brain pathology consistent with TSC patients, notably increased mTORC1 activity and ectopic clusters of cytomegalic cells.

Discussion

Here we report neuropathological phenotypes associated with

Nestin-CRE-ER

T2 x RFP x

Tsc2 mice. We confirmed selective labeling of the progeny and stem cells of the V-SVZ and hippocampus. We confirmed labeling of neuroblasts migrating to the olfactory bulb or astrocytes in the striatum and cortex that are produced from these stem cells [

22]. p4EBP was detected in V-SVZ cells including NSCs but p4EBP was absent in astrocytes. However, we cannot rule out that p4EBP is below the threshold of detection in this study. We found that removal of

Tsc2 increased p4EBP as we previously demonstrated in focal knockout using neonatal electroporation of CRE in the same conditional

Tsc2 mice. P4EBP was extremely high in outer V-SVZ NSCs, although such cells were sparse (~2/slice/V-SVZ). However, following loss of

Tsc2, on occasion, cells outside of the V-SVZ continued to have elevated p4EBP and retained stem cell proteins including Nestin or Sox2. In most slices, we found 2-4 cytomegalic cells having a neuron-like morphology within the dorsal-lateral striatum and stained positive for either NeuN or Sox2. Neurons were also prevalent along the ventral V-SVZ near the anterior commissure which is consistent with

Tsc1 or focal neonatal electroporation

Tsc1 or

Tsc2 models. However, the extent to which this represents a completely “mutant” phenomenon is unclear as occasional neurons were also identified in control conditions. However, we previously placed this increase at ~3× and ~7× the number of neurons compared to ventral and lateral control conditions[

22].

Subependymal nodules are common TSC brain malformations[

1,

40]. They are small (<1 cm) protrusions near the interface of the subependymal/subventricular zone, lateral ventricles, and striatum and frequently appear early in life[

4,

8]. They appear “button-like” or as “candle-gutterings”[

41,

42]. In addition to their anatomical appearance as “growths”, they can be discolored in comparison to the surrounding tissue. TSC SENs are often found before the age of five[

8]. However, the actual prevalence at young ages is likely higher and may go unnoticed since the mean age of TSC diagnosis was 7.5 years of age in 2011. Screening for SENs is uncommon and specific neurological manifestations are not yet attributed to SENs[

43]. However, SENs (having more than 2) is also a major diagnostic criterion of TSC[

44]. Approximately 1/5

th of TSC patients have growths around the ventricles larger than SENs called subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGAs)[

8,

40,

45]. SEGAs have profound heterogeneity, which might be a product of a specific procession of events. It appears that SENs transform into SEGAs in some patients[

46,

47]. However, this is debated. In some reports, SENs are not easily detectable by routine MRI screening and are instead found during operation, postoperatively, or posthumously[

48]. Computed tomography scans better detect SENs. Thus, the immediate appearance of SEGAs in the absence of SEN could be a limitation of diagnostic imaging and monitoring. Nevertheless, SENs and SEGAs share histopathological features and therefore it is reasonable to consider SENs as precursors to SEGAs[

49]. Although there is no consensus, the criterion of SEGA diagnosis ranges from >0.5-1.0 cm in size or serial growth[

50,

51]. SEGAs typically with a greater than 10 mm diameter near the foramen of Monro are also monitored for growth by MRI coupled with gadolinium[

52]. SEGAs form early in life with the median age of SEGA diagnosis at 1 and high growth rates in children during brain development[

53]. While the model presented here shares some aspects of SENs and SEGAs, they rarely appear to protrude into the ventricle.

Occasional neurons were found in the cerebral cortex. In comparison to previous studies using

Tsc1 mice, there were far fewer cortical neurons[

24]. However, in two

Tsc2 mutant mice, we found cortical abnormalities consistent with TSC pathology including the presence of a mislaminated cortex having sparse NeuN labeling and rounded giant or balloon-like cells that were pS6 positive. Approximately 33% of mice had clear identifiable gross anatomical defects. The most frequent defects were within the striatum but were heterogenous in appearance. They could be categorized as ectopic disorganized neuronal clusters or glia-like heterotopias. Whereas neurons were pS6 positive, cells that were glia-like were p4EBP positive. Incidentally, the majority of RFP positive cells in the cortical plate were astrocytes. We found that lower layers of the cerebral cortex had fewer astrocytes. At first appearance, these results oppose those that describe loss of

Tsc genes from neurogenic radial glia during embryogenesis[

35,

54,

55,

56,57,58,59]. Moreover, a recent study has described that removal of

Tsc1/Tsc2 causes an increase in the number of intermediate progenitors, upper layer neurons, and GFAP positive cells[

38]. Although it is unclear whether those GFAP positive cells are indeed astrocytes or NSCs. One possible explanation for our finding is that enhanced mTORC1 dependent translation alters cell transitional events based on the timing of TSC loss and which mRNAs are present [

22]. Thus, while dorsal radial glia remain, they may slow in their gliogenic divisions. Future studies should distinguish between this possibility, the importance of timing of loss of TSC genes in gliogenic stem cells and whether the mode of division (for example, self-renewing cell division vs. terminal cell division producing neurons or glia) may be disrupted.

These studies support a model wherein several events likely occur during the development of TSC brain pathology. Loss of both alleles of

Tsc2 in NSCs prevents the downregulation of mTORC1 activity in glia and stem cell proteins in a small fraction of cells leading to histopathological hallmarks consistent with TSC. These cells may require several weeks or months to gain the characteristics the pathognomonic “giant cells” of TSC as previously reported using a doxycycline

Nestin-CRE system during embryogenesis[60]. However, these studies do not rule out the possibility that some pathogenic variants in

TSC1 or

TSC2 may only require heterozygosity for the formation of lesions. In addition, there may be single nucleotide polymorphisms that collaborate with pathogenic heterozygous mutations to cause gross anatomical defects in TSC. ~2.4% of SEGAs were identified after age 40 in one study refuting the probability of mutation of genes other than

TSC1 and TSC2 as a significant cause of SEGAs[61]. Also, fewer than 10% of patients have bilateral SEGAs, but of all patients with SEGAs, ~45% have multiple or bilateral SEGAs. This result supports the idea that predisposing factors might make some patients more susceptible to developing SEGAs. This could be related to genotype since 13.2% of all patients have SEGAs with

TSC1 mutations and 33.7% of all patients have SEGAs with

TSC2 mutations[

53]. Accordingly, in this comprehensive study, ~89.3% of all patients having SEGAs had mutations identified in

TSC2. In addition,

PKD1 is oriented in a tail-to-tail configuration with the

TSC2 gene. Mutations affecting both genes cause

PKD1-

TSC2 contiguous gene syndrome, but this occurs in an estimated 3% of TSC cases and leads to polycystic kidney phenotypes and SEGAs[62]. Given that genetic testing may overlook the involvement of

PKD1, its contribution to SEGA formation may be more common than currently recognized. Bilateral SEGAs are predicted to occur more frequently in patients with familial inherited TSC gene mutations and unilaterally in sporadic TSC. This idea aligns with Alfred Knudson’s proposed two-hit theory indicating that TSC hamartomas are caused by LOH(18,63). Indeed,

TSC1 or

TSC2 LOH occurs in SEGAs[64–67]. Involvement of additional mutations including in the proto-oncogene

BRAF encoding the B-Raf kinase have dissolved with only

TSC1 or

TSC2 mutations consistently identified[67]. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen whether additional genetic or epigenetic events contribute to the appearance and growth of SEGAs.

Although there was tremendous heterogeneity in TSC mouse phenotypes, it is noteworthy that some anatomical defects were not bilaterally localized within the mice arguing against the genetic background being the major driver of phenotype. Moreover, despite several of the same cell types affected, the phenotypes appeared stochastically. Some TSC brain malformations have been theorized to arise from stem cells that are enriched in humans and are sparse in rodents which could also be a reason that brain lesions are rare in this model. It is also possible that the cell types responsible for TSC phenotypes are infrequently targeted in the Nestin-CRE-ER

T2 model when tamoxifen is provided during the early neonatal period. While this is the most parsimonious reason that cortical malformations are rare given that we previously indicated that tubers were caused by loss of heterozygosity within embryonic NSCs (radial glia), we would have predicted that SENs/SEGAs and striatal hamartomas should be produced[

36]. However, they were not efficiently generated which could be related to inefficient recombination in a cell type. Neonatal electroporation of

Tsc2 mice, loss of

Tsc1 by Nestin-CRE-ER

T2 or Mash-CRE-ER

T2, or double

Tsc1/PTEN knockout using Nestin-CRE-ER

T2 generates nodules or SEGAs [

21,

22,

23,

24,

27,68,69]. Nevertheless, we favor a model for which compensatory mechanisms may allow for the titration of mTORC1 activity and translation which may overcome loss of

Tsc2[

27]. But if cells are unable to do this in a timely manner, and stemness is not lost, the wrong cells are produced and over time develop into cytomegalic neurons or giant cells which may affect brain anatomy and function. This is consistent with the cellular diversity of SEGAs and the abundance of GABAergic neurons[70].

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Clemson University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all performed experiments, and all guidelines set forth by the Clemson University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were compliant with the Animal Care and Use Review Office (ACURO), a component of the USAMRDC Office of Research Protections (ORP) within the Department of Defense (DoD). (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J) (Strain #007909), C57BL/6-Tg(Nes-cre/ERT2)KEisc/J (Strain #:016261), Tsc2tm1.1Mjg/J (Strain #027458) were acquired from Jackson Laboratories. Mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle and fed ad libitum. Recombination was induced using (Z)-4-Hydroxy-tamoxifen (Sigma Aldrich Cat#H7904) injected at a dose of 20-50 μg/g as previously described between P0-P2 for two consecutive days.

Genotyping PCR.

50 mM NaOH with 0.2 mM EDTA was added to tissue and incubated at 50°C for 90 minutes. An equal volume of 100 mM Tris-HCl was subsequently mixed with the digested tissue. Samples were briefly vortexed and centrifuged and 1-2 µL of supernatant was added to PCR Taq buffer (#R0241), forward primer 0.1-1.0 µM and reverse primer 0.1-1.0 µM, 1 mM MgCl2, template DNA, 1.25 U of Taq DNA Polymerase, and nuclease-free water (#R0581) for a final volume of 50 µL. Samples were placed into a thermocycler set for; initial denaturation step at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, an annealing step at 60°C for 30 s, and an extension at 72°C for 30 seconds followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Mice having conditional Tsc2 alleles are distinguished by endpoint genotyping PCR using the following primer sequences, 5’-ACAATGGGAGGCACATTACC-3’ and 5’AGCAGCAGGTCTGCAGTG-3’. A wild type amplicon of 191 bp and a floxed amplicon of 250 bp are produced. Tomato genes were identified for Stock #7914 by endpoint genotyping PCR using the following primer sequences, 5’-AAGGGAGCTGCAGTGGAG TA-3’ and 5’-CCG AAAATCTGTGGGAAG TC-3’ and 5’-GGCATTAAAGCAGCGTATCC-3’ and 5’-CTGTTCCTGTACGGCATGG-3’ generating a tdTomato Mutant ~200 bp amplicon or a 297 bp Wild type amplicon. Nestin-CRE-ERT2 mice were genotyped with one of two primer sets 5’-ATGCAGGCAAATTTTGGTGT-3’ (CRE) and 5’-CGCCGCTACTTCTTTTCA AC-3’ (Nestin) and 5’-AGTGGCCTCTTCCAGAAATG-3’ (Internal Positive Control) and 5’-TGCGACTGTGTCTGATTTCC-3’ (Internal Positive Control). Alternatively, Nestin-CRE-ERT2 mice were genotyped with 5’-ATACCGGAGATCATGCAAGC-3’ (CRE) and 5’-GGCCAGGCTGTTCTTCTTAG-3’ (ERT2) and 5’-CTAGGCCAAGAATTGAAAGATCT-3’ (Internal Positive Control) and 5’-GTAGGTGGAAATTCTAGCATCATCC-3’ (Internal Positive Control)

Immunohistochemistry.

Euthasol (50 mg/kg) was administered by intraperitoneal injection followed by decapitation. Brains were dissected at room temperature in PBS and placed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde (in PBS). Brains were rinsed with PBS, mounted in agarose (3%), and sectioned on a Leica VTS 1000 vibratome. Sections were blocked with 2% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS for 1 hr at room temperature. PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 was used to subsequently was sections three times. Sections were subsequently incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed three times in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. Sections were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor series; 1:500; Invitrogen) overnight at 4°C. Sections were mounted in ProLong Gold or Prolong Glass Antifade Mountant (ThermoFisher), covered with a coverslip, and nail polish was used to seal the samples. Images were acquired on a Leica SPE spectral confocal microscope with ×63 oil immersion objective, ×20 dry objective, or ×5 dry objectives.

Image Analysis.

Images were uploaded and analyzed on FIJI (ImageJ 1.5 g). The freehand selection tool was used to trace a region of interest (ROI) on RFP positive and RFP negative cells in the same Z section. The mean gray value was used to quantify the p4EBP staining intensity represented as the ratio of RFP positive/RFP negative for Tsc2wt/wt and Tsc2mut/mut conditions. The ventral portion of the V-SVZ from the same slice and region was traced to quantify the area of RFP positive cells from Tsc2wt/wt and Tsc2mut/mut mice. The distance from the dorsal aspect of the lateral ventricle to the pia surface was measured using the line tool. The distribution of glia within the dorsal forebrain was measured by drawing a line from the dorsal lateral ventricle to the pia surface. The histogram values of RFP positive cells starting from the ventricle to the outer cortical region were then exported into Graphpad and represented as the RFP signal in relation to distance.

Statistics

Data were graphed and analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (Version 8.2.0, GraphPad Software Inc.). Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test. Quantification was performed on 5-6 mice per condition per time point. Error bars are reported as standard error mean.

Figure 1.

Targeted Recombination in Gliogenic and Neurogenic Stem Cells A. Schematic diagram of conditional Tsc2 deletion. B. Coronal section of mouse brain with targeted regions along the lateral ventricle (VL). Allen Mouse Brain Atlas and Allen Reference Atlas – Mouse Brain mouse.brain-map.org and atlas.brain-map.org. C, D. 20× image of coronal section of an olfactory bulb from Tsc2wt/wt (C) or Tsc2mut/mut (D) demonstrating that most RFP positive cells (magenta) are neuroblasts and are DCX positive (yellow) not Neu-N positive (cyan). E, F. 5× image of coronal section of region shown in B and from Tsc2wt/wt (E) or Tsc2mut/mut (F) at P10 demonstrating RFP positive cells (magenta) along the lateral ventricle and Neu-N (cyan) to mark neurons. G, H. 5× image of coronal section of region shown in B and from Tsc2wt/wt (G) or Tsc2mut/mut (H) at P10 demonstrating that RFP positive cells (magenta) along the lateral ventricle colocalize with Sox2 (cyan) which labels neuroprogenitors. I, J. 5× image of coronal section of region shown in B from Tsc2wt/wt (I) or Tsc2mut/mut (J) at P10 demonstrating that RFP positive cells (magenta), vimentin positive neural stem cells (yellow) and DCX positive neuroblast (cyan). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 1.

Targeted Recombination in Gliogenic and Neurogenic Stem Cells A. Schematic diagram of conditional Tsc2 deletion. B. Coronal section of mouse brain with targeted regions along the lateral ventricle (VL). Allen Mouse Brain Atlas and Allen Reference Atlas – Mouse Brain mouse.brain-map.org and atlas.brain-map.org. C, D. 20× image of coronal section of an olfactory bulb from Tsc2wt/wt (C) or Tsc2mut/mut (D) demonstrating that most RFP positive cells (magenta) are neuroblasts and are DCX positive (yellow) not Neu-N positive (cyan). E, F. 5× image of coronal section of region shown in B and from Tsc2wt/wt (E) or Tsc2mut/mut (F) at P10 demonstrating RFP positive cells (magenta) along the lateral ventricle and Neu-N (cyan) to mark neurons. G, H. 5× image of coronal section of region shown in B and from Tsc2wt/wt (G) or Tsc2mut/mut (H) at P10 demonstrating that RFP positive cells (magenta) along the lateral ventricle colocalize with Sox2 (cyan) which labels neuroprogenitors. I, J. 5× image of coronal section of region shown in B from Tsc2wt/wt (I) or Tsc2mut/mut (J) at P10 demonstrating that RFP positive cells (magenta), vimentin positive neural stem cells (yellow) and DCX positive neuroblast (cyan). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 2.

Loss of Tsc2 in NSCs Increases mTORC1 Activity. A. 5× image of coronal section of a P10 Tsc2wt/wt demonstrating RFP (magenta) in Nestin (yellow) positive cells in the V-SVZ and stained for p4EBP (cyan). B.,C. 20× (B) and 40× digital zoom (C) demonstrating that p4EBP (blue) staining is mostly along the V-SVZ where RFP (red) NSCs are located. D. 5× image of coronal section of a P10 Tsc2mut/mut demonstrating RFP (magenta) in Nestin (yellow) positive cells in the V-SVZ and stained for p4EBP (cyan). E., F. 20× (E) and 40× (F) digital zoom demonstrating that p4EBP (blue) staining is mostly in the V-SVZ where RFP (red) NSCs are located and in an outer V-SVZ NSC. G-J. 20× images of coronal sections of a P30 Tsc2wt/wt in the upper (G, H) or lower V-SVZ (I, J) showing RFP (magenta) and p4EBP (blue). (K-N) 20× images of coronal sections of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut in the upper (K, L) or lower V-SVZ (M, N) showing RFP (magenta) and p4EBP (blue). O-P. 63× image of coronal section with up-regulated p4EBP within the striatum of heterotopically placed cells. Q. Quantification of mTORC1 activity in the V-SVZ of Tsc2wt/wt and Tsc2mut/mut NSCs. R. Quantification of V-SVZ area. S. Schematic diagram of the regulation of mTORC1 activity in NSCs. Scale bar A, B, D, E, G-N = 50 µm. Scale bar = 100 µm for C and F. Scale Bar = 157.5 µm O-P. * = p<0.05.

Figure 2.

Loss of Tsc2 in NSCs Increases mTORC1 Activity. A. 5× image of coronal section of a P10 Tsc2wt/wt demonstrating RFP (magenta) in Nestin (yellow) positive cells in the V-SVZ and stained for p4EBP (cyan). B.,C. 20× (B) and 40× digital zoom (C) demonstrating that p4EBP (blue) staining is mostly along the V-SVZ where RFP (red) NSCs are located. D. 5× image of coronal section of a P10 Tsc2mut/mut demonstrating RFP (magenta) in Nestin (yellow) positive cells in the V-SVZ and stained for p4EBP (cyan). E., F. 20× (E) and 40× (F) digital zoom demonstrating that p4EBP (blue) staining is mostly in the V-SVZ where RFP (red) NSCs are located and in an outer V-SVZ NSC. G-J. 20× images of coronal sections of a P30 Tsc2wt/wt in the upper (G, H) or lower V-SVZ (I, J) showing RFP (magenta) and p4EBP (blue). (K-N) 20× images of coronal sections of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut in the upper (K, L) or lower V-SVZ (M, N) showing RFP (magenta) and p4EBP (blue). O-P. 63× image of coronal section with up-regulated p4EBP within the striatum of heterotopically placed cells. Q. Quantification of mTORC1 activity in the V-SVZ of Tsc2wt/wt and Tsc2mut/mut NSCs. R. Quantification of V-SVZ area. S. Schematic diagram of the regulation of mTORC1 activity in NSCs. Scale bar A, B, D, E, G-N = 50 µm. Scale bar = 100 µm for C and F. Scale Bar = 157.5 µm O-P. * = p<0.05.

Figure 3.

Cellular Phenotypes Associated with Tsc2 Mutation. A. 5× or 10× (B) image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain demonstrating RFP (magenta), GFAP (yellow), and the DNA counterstain TO-PRO-3 (cyan) showing labeling of the V-SVZ and hippocampus. C. 5× image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (magenta) positive hippocampus and the DNA counterstain TO-PRO-3 (blue) showing labeling of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. D. 5× image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (magenta) positive hippocampus, NeuN (green) and the DNA counterstain TO-PRO-3 (blue) showing labeling of neurons in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. E-J. 5× (E), 10× (F), or 20× (G-J) image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red) positive cells surrounding the ventricle with the NSC marker Nestin (green), and GFAP (blue) which labels both NSCs and astrocytes. K. 20× image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (magenta) and cytomegalic Sox2 positive (yellow) cells in the striatum indicated by cyan arrows. The magenta box was magnified 2× digitally (L) and only Sox2 is shown (green) with magenta arrows highlighting the enlarged nucleus of the cytomegalic cells. M-N. 20× image of the lateral portion of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red), pS6 (blue) and DCX (green) cells mainly localized in the V-SVZ with occasional cells infiltrating the striatum indicated by cyan arrows. O-P. 20× image of the ventral portion of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red), pS6 (blue) and DCX (green) cells mainly localized in the V-SVZ with occasional cells infiltrating the striatum indicated by cyan arrows. Q-R. 20× image of the lateral portion of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red) and glutamine synthetase (GS, blue) showing that most RFP cells in the striatum have a glial morphology and are GS positive. S-T. 20× image of the lateral portion of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red) and NeuN (blue) demonstrating the presence of cytomegalic neurons.

Figure 3.

Cellular Phenotypes Associated with Tsc2 Mutation. A. 5× or 10× (B) image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain demonstrating RFP (magenta), GFAP (yellow), and the DNA counterstain TO-PRO-3 (cyan) showing labeling of the V-SVZ and hippocampus. C. 5× image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (magenta) positive hippocampus and the DNA counterstain TO-PRO-3 (blue) showing labeling of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. D. 5× image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (magenta) positive hippocampus, NeuN (green) and the DNA counterstain TO-PRO-3 (blue) showing labeling of neurons in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. E-J. 5× (E), 10× (F), or 20× (G-J) image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red) positive cells surrounding the ventricle with the NSC marker Nestin (green), and GFAP (blue) which labels both NSCs and astrocytes. K. 20× image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (magenta) and cytomegalic Sox2 positive (yellow) cells in the striatum indicated by cyan arrows. The magenta box was magnified 2× digitally (L) and only Sox2 is shown (green) with magenta arrows highlighting the enlarged nucleus of the cytomegalic cells. M-N. 20× image of the lateral portion of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red), pS6 (blue) and DCX (green) cells mainly localized in the V-SVZ with occasional cells infiltrating the striatum indicated by cyan arrows. O-P. 20× image of the ventral portion of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red), pS6 (blue) and DCX (green) cells mainly localized in the V-SVZ with occasional cells infiltrating the striatum indicated by cyan arrows. Q-R. 20× image of the lateral portion of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red) and glutamine synthetase (GS, blue) showing that most RFP cells in the striatum have a glial morphology and are GS positive. S-T. 20× image of the lateral portion of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain with RFP (red) and NeuN (blue) demonstrating the presence of cytomegalic neurons.

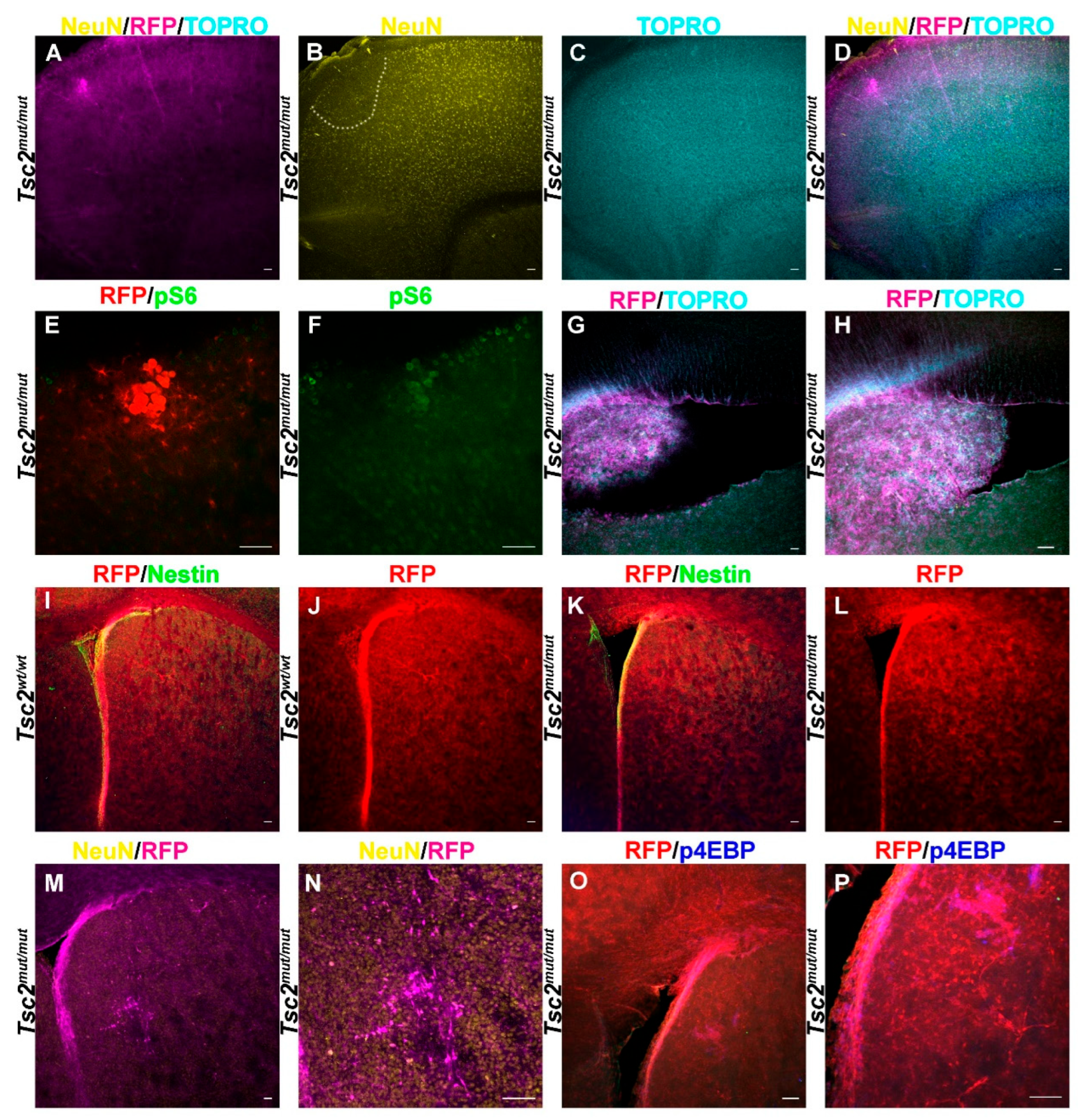

Figure 4.

Loss of Tsc2 Models TSC Brain Pathological Features. A-D. 5× image of coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut demonstrating RFP (magenta, A.) positive cells forming a lesion in the cerebral cortex. The lesion had sparse neurons indicated by NeuN staining (yellow, B.) although the cortex did not generally appear mislaminated as seen with the counterstain TO-PRO-3 (cyan, C) which labels DNA unless the composite (D) is examined. E, F. 20× image of the lesion in A-D demonstrating that RFP positive (red, E.) giant/balloon cells are also pS6 positive (green, F). G. 5× or (H) 20× image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut demonstrating RFP (red) positive cells protruding into the lateral ventricles. I. 5× image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2wt/wt brain demonstrating RFP (red) positive cells together with Nestin staining (green) around the ventricle or RFP alone (J) to show organization of the striatum. K. 5× image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain demonstrating RFP (red) positive cells together with Nestin staining (green) or RFP alone (L) to show organization of a typical brain without a lesion. M. 5× or 20× (N) image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain demonstrating RFP (magenta) and NeuN staining (yellow) positive cells and a striatal lesion made of disorganized neurons. O. 5× or 20×(P) image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain demonstrating RFP (magenta) and p4EBP staining (blue) positive cells and a striatal lesion made of disorganized glia-like cells.

Figure 4.

Loss of Tsc2 Models TSC Brain Pathological Features. A-D. 5× image of coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut demonstrating RFP (magenta, A.) positive cells forming a lesion in the cerebral cortex. The lesion had sparse neurons indicated by NeuN staining (yellow, B.) although the cortex did not generally appear mislaminated as seen with the counterstain TO-PRO-3 (cyan, C) which labels DNA unless the composite (D) is examined. E, F. 20× image of the lesion in A-D demonstrating that RFP positive (red, E.) giant/balloon cells are also pS6 positive (green, F). G. 5× or (H) 20× image of a sagittal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut demonstrating RFP (red) positive cells protruding into the lateral ventricles. I. 5× image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2wt/wt brain demonstrating RFP (red) positive cells together with Nestin staining (green) around the ventricle or RFP alone (J) to show organization of the striatum. K. 5× image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain demonstrating RFP (red) positive cells together with Nestin staining (green) or RFP alone (L) to show organization of a typical brain without a lesion. M. 5× or 20× (N) image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain demonstrating RFP (magenta) and NeuN staining (yellow) positive cells and a striatal lesion made of disorganized neurons. O. 5× or 20×(P) image of a coronal section of a P30 Tsc2mut/mut brain demonstrating RFP (magenta) and p4EBP staining (blue) positive cells and a striatal lesion made of disorganized glia-like cells.

Figure 5.

Neonatal Tsc2 Deletion Alters Cortical Development A-C. 5× coronal sections of Tsc2wt/wt mouse brains showing RFP positive cell distribution in three different mice. D-F. 5× coronal sections of Tsc2mut/mut mouse brains showing RFP positive cell distribution in three different mice. G. Quantification of cortical thickness (N=6 for each genotype). H. Quantification of RFP positive cell distribution from the ventricle to the cortical pial surface demonstrating loss of glia from lower cortical layers (N=6 for each genotype). Scale bar = 50 µm. * denotes p=0.0410.

Figure 5.

Neonatal Tsc2 Deletion Alters Cortical Development A-C. 5× coronal sections of Tsc2wt/wt mouse brains showing RFP positive cell distribution in three different mice. D-F. 5× coronal sections of Tsc2mut/mut mouse brains showing RFP positive cell distribution in three different mice. G. Quantification of cortical thickness (N=6 for each genotype). H. Quantification of RFP positive cell distribution from the ventricle to the cortical pial surface demonstrating loss of glia from lower cortical layers (N=6 for each genotype). Scale bar = 50 µm. * denotes p=0.0410.