Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

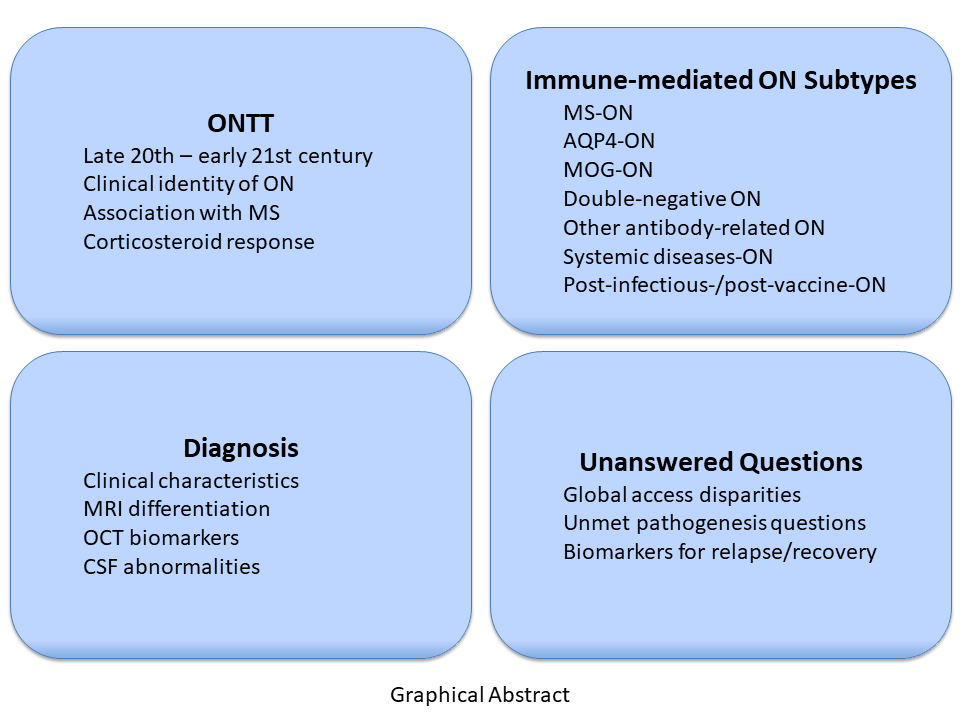

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

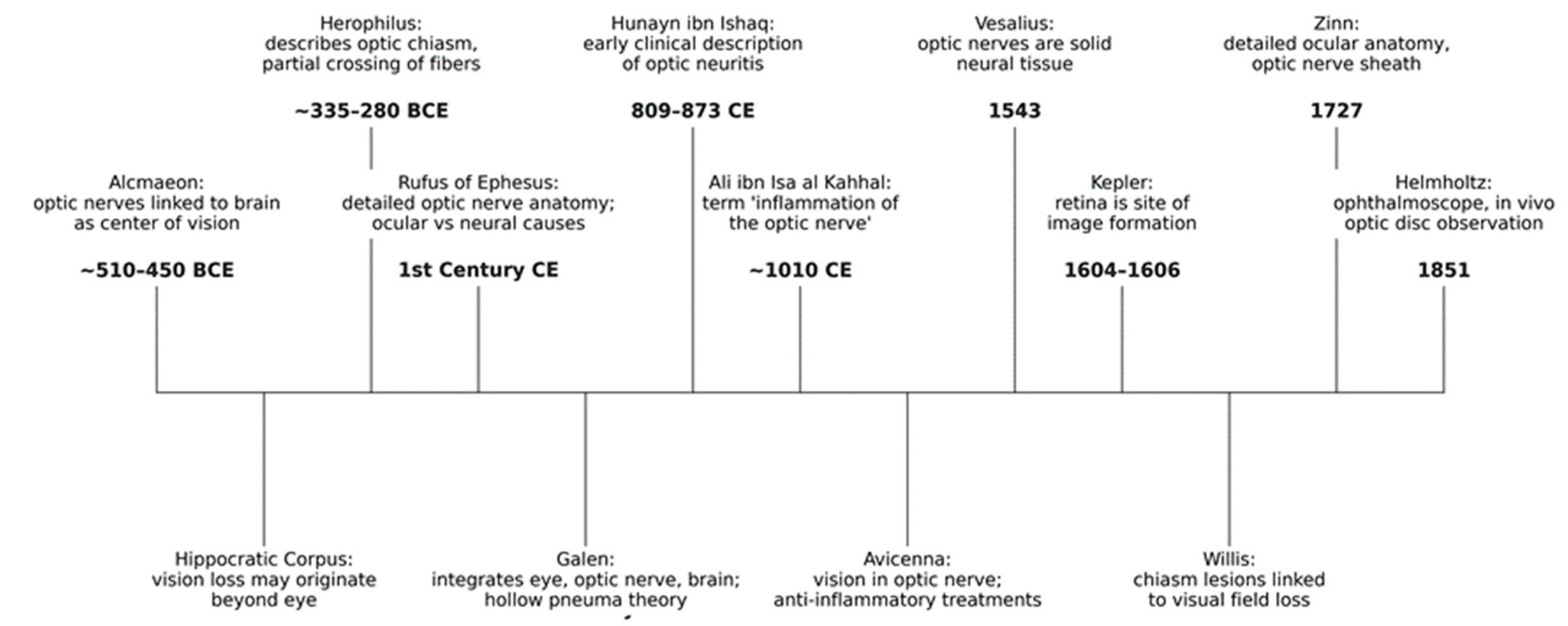

2. Historic Foundations of the Concept of Optic Neuritis

2.1. Ancient Contribution: The Discovery of the Optic Nerve and Its Function

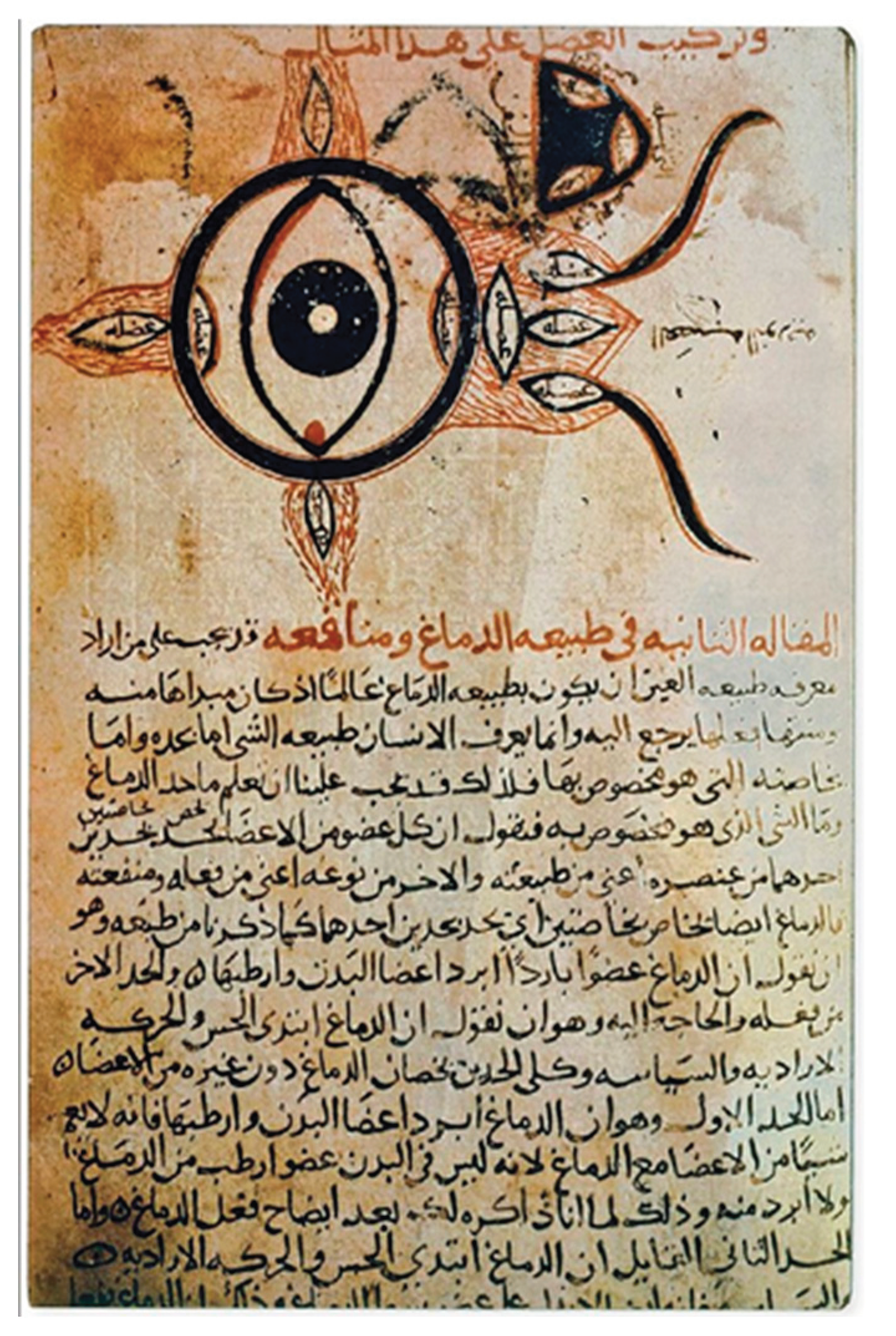

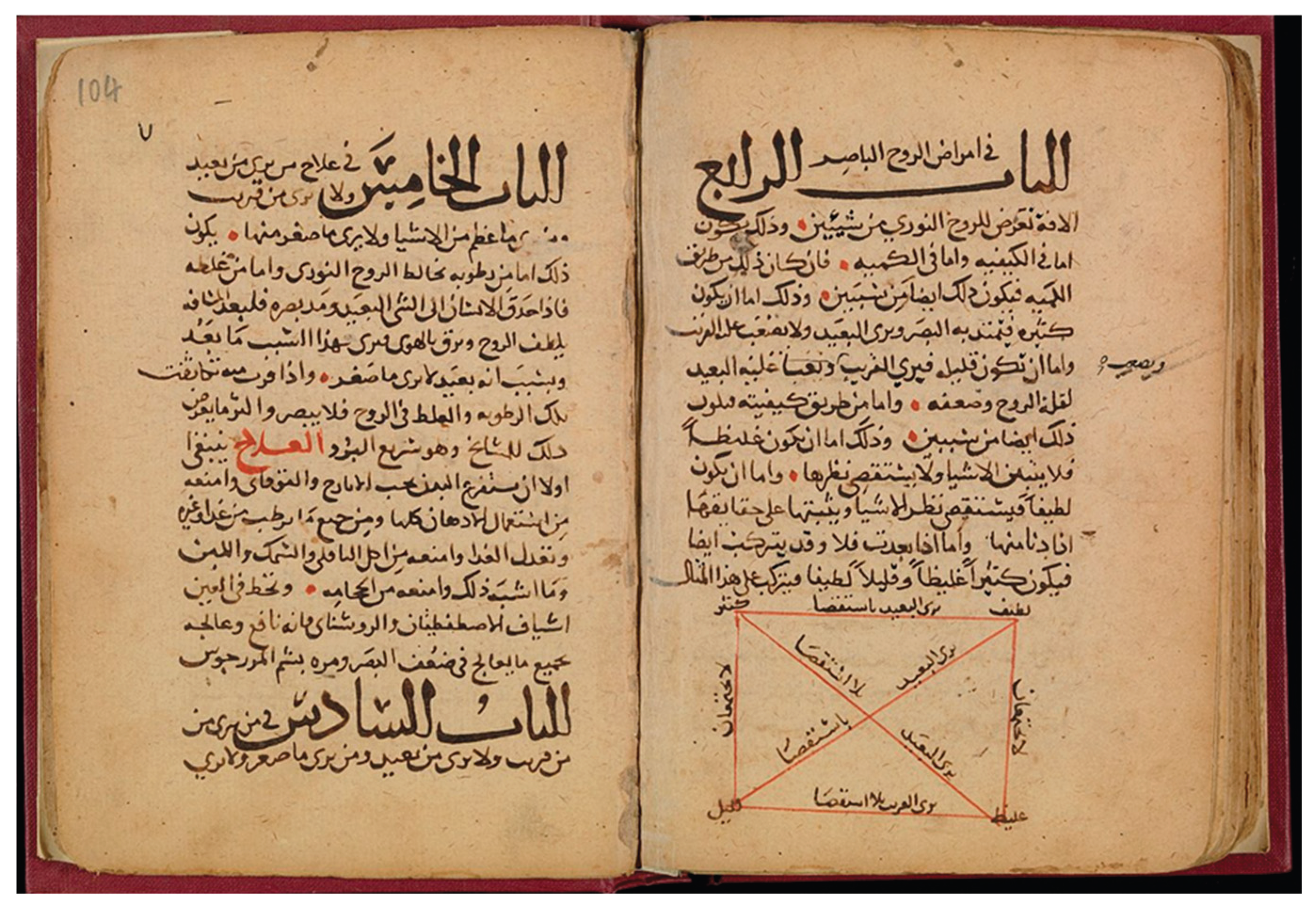

2.2. The Middle Age Contribution: Early Clinical Characterization and Treatment of Inflammation of the Optic Nerve

2.3. The Renaissance and Early Modern Age: The Definitive Abandonment of Galenic Tradition

2.4. The Modern Age: The Invention of the Microscope and the Characterization of Optic Neuritis

2.5. The Relationship Between Optic Neuritis and Multiple Sclerosis

3. The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial and Characterization of Multiple Sclerosis-Related Optic Neuritis

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characterization of Optic Neuritis in the ONTT

3.2. Assessment of Corticosteroid Treatment

3.3. Multiple Sclerosis Risk and Prognostic Value of MRI

3.4. The Role of Optic Neuritis in the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis

4. Beyond the ONTT: The Non-Multiple Sclerosis-Related Optic Neuritis (“Atypical Optic Neuritis”)

4.1. Aquaporin 4-Related Optic Neuritis

4.2. MOG-Related Optic Neuritis

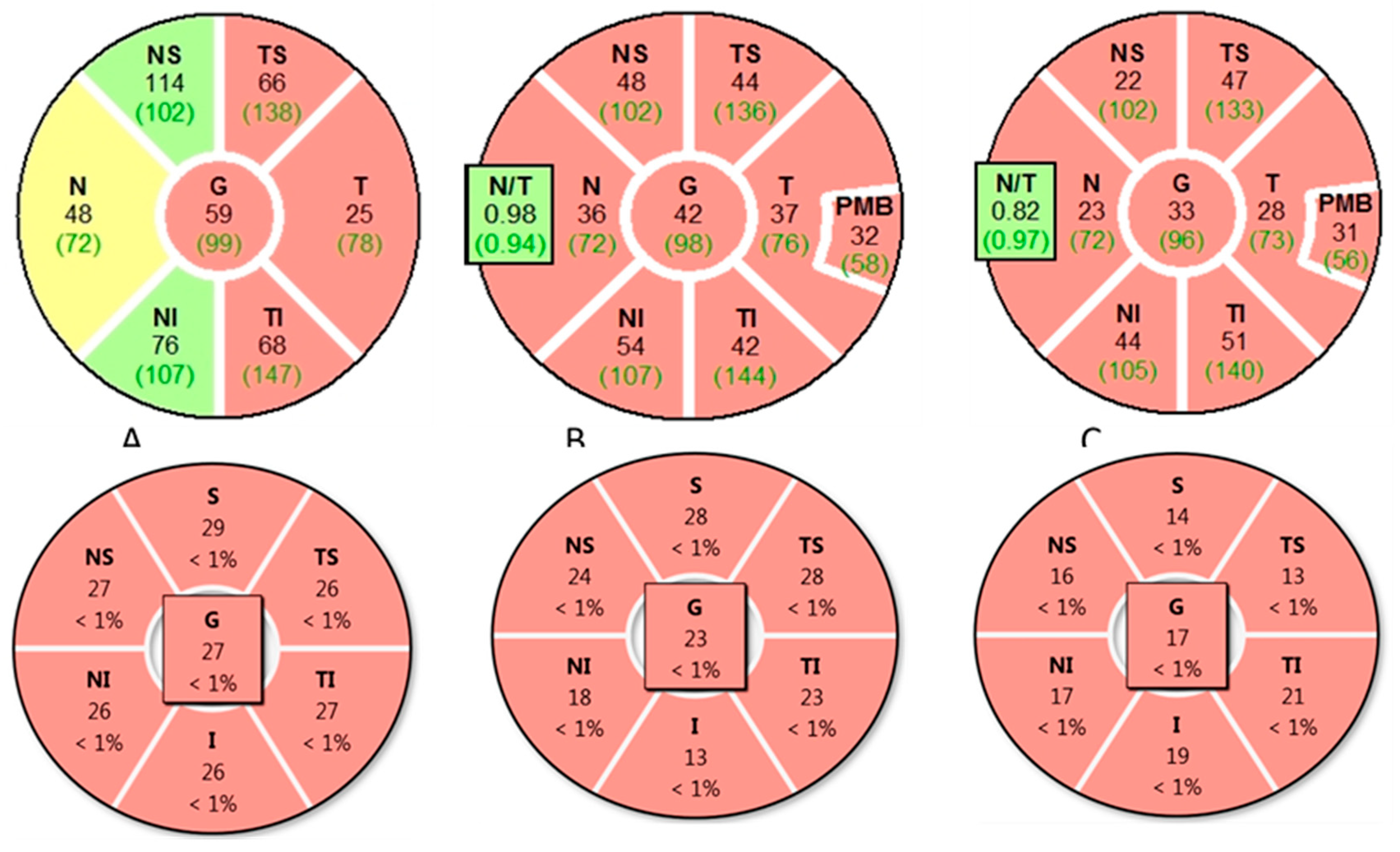

4.3. Distinct Clinical, Biomarker, and Imaging Profiles of MS-ON, AQP4-ON and MOG-ON

4.4. Relapsing Optic Neuritis

4.5. Chronic Relapsing Inflammatory Optic Neuropathy

4.6. GFAP-Related Optic Neuritis

4.7. CRMP5-Related Optic Neuritis

4.8. Optic Neuritis in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases

4.9. Post-Infectious and Post-Vaccination Optic Neuritis

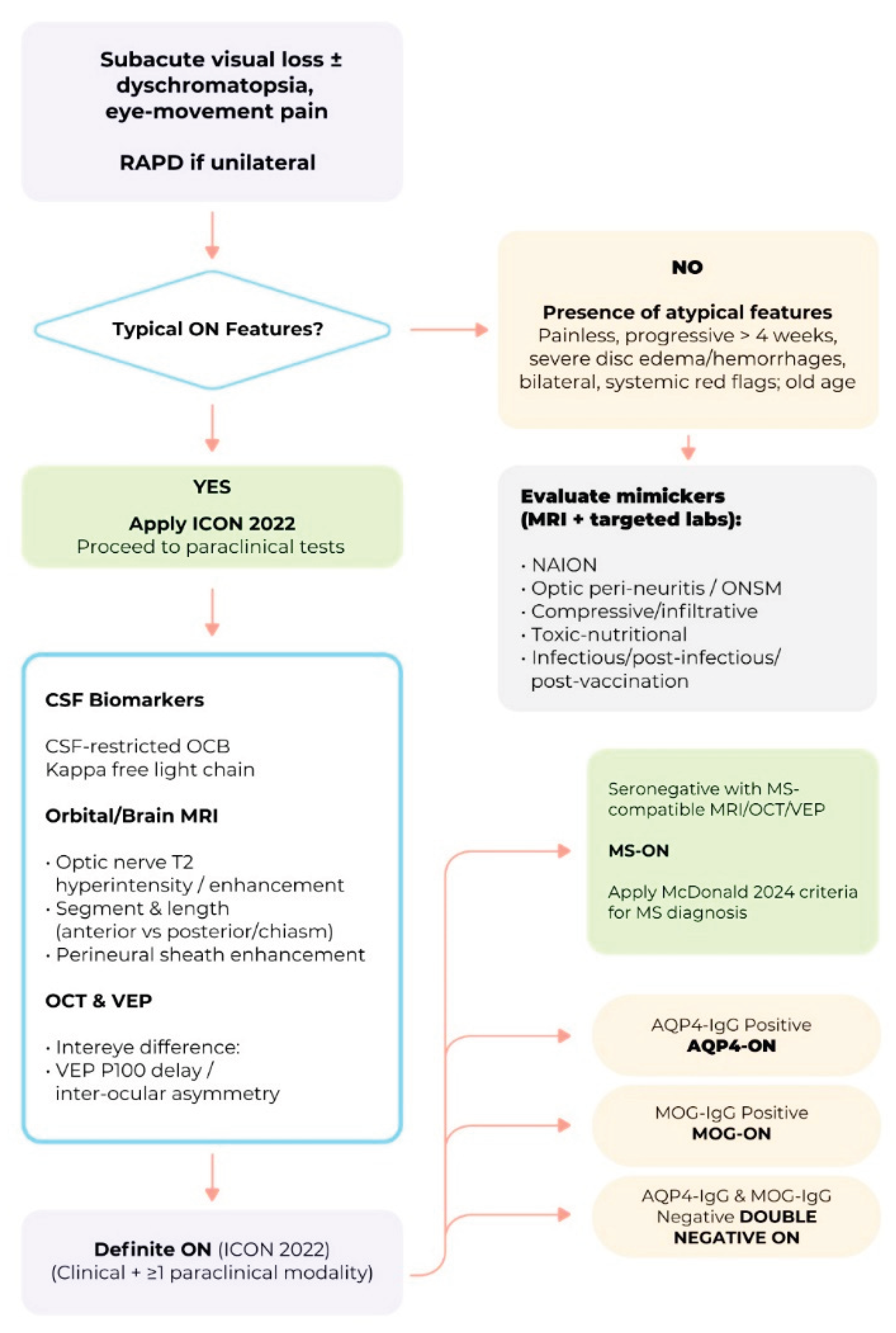

5. Diagnosis of Optic Neuritis

5.1. Clinical History and Examination

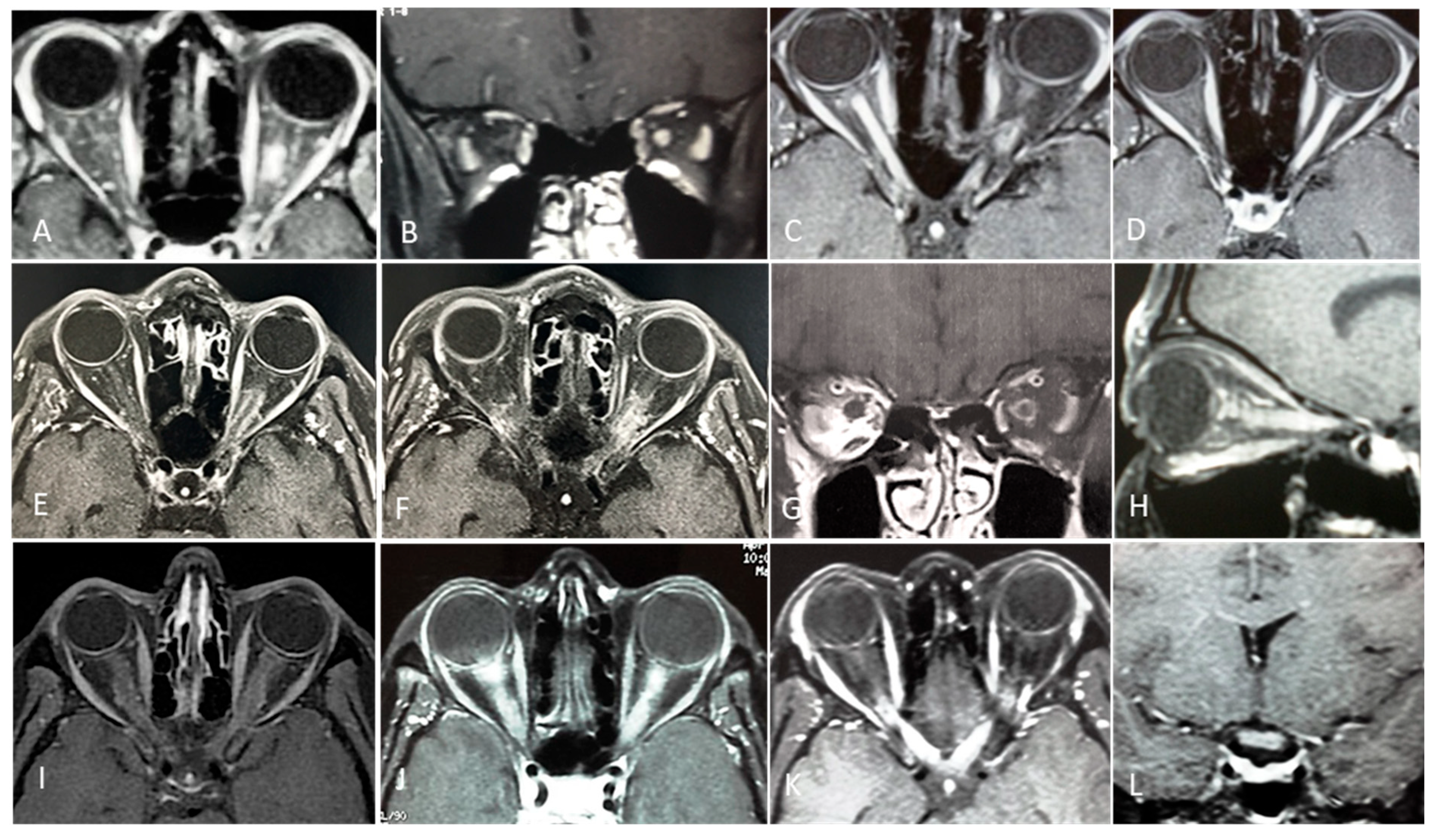

5.2. Paraclinical and Supportive Tests

5.3. Diagnostic Criteria for Optic Neuritis

6. Unanswered Questions and Unmet Research Needs

6.1. Damage and Repair in MS-ON

6.2. Double-Negative Optic Neuritis

6.3. Biomarker Development and Standardization

6.4. Imaging Biomarkers

6.5. Therapeutic Algorithms and Clinical Trials

6.6. Global Disparities and the for Collaborative Research Networks

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Angiotensin-conversion enzyme |

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| APD | Afferent pupillary defect |

| AQP4 IgG | Aquaporin-4 |

| AQP4-ON | Aquaporin-4-associated optic neuritis |

| ARR | Annualized relapse rate |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CF | Count fingers |

| CRION | Chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy |

| CRMP5 | Collapsin response-mediator protein 5 |

| CS | Contrast sensitivity |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CVS | Central vein sign |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DIS | Dissemination in space |

| DIT | Dissemination in time |

| DN-ON | Double negative optic neuritis |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| EDSS | Expanded disability status scale |

| GCIPL | Ganglion cell internal plexiform layer |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GFAP-A | GFAP astrocytopathy |

| GFAP-ON | GFAP-associated-ON |

| HCVA | High-contrast visual acuity |

| HM | Hand motion |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| ICON | International consensus on optic neuritis |

| IEAD | Intereye absolute difference |

| IED | Intereye difference |

| IEF | Isoelectric focusing |

| IEPD | Intereye percentage difference |

| IVMP | IV methylprednisolone |

| IWOS | International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis |

| KFLC | Kappa free light chains |

| LCVA | Low-contrast visual acuity |

| LEON | Longitudinally extensive optic nerve |

| LP | Light perception |

| mfVEP | Multifocal VEP |

| MOG IgG | Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein |

| MOGAD | Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease |

| MOG-ON | Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein–associated optic neuritis |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| MS-ON | Multiple sclerosis-associated optic neuritis |

| NLP | No light perception |

| NMOSD | Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder |

| non-MS-ON | Atypical ON |

| OCB | Oligoclonal bands |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| OCT-A | Optic coherence tomography angiography |

| ON | Optic neuritis |

| ONSG | Optic Neuritis Study Group |

| ONTT | Optic neuritis treatment trial |

| OPN | Optic perineuritis |

| PRLs | Paramagnetic rim lesions |

| pRNFL | Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer |

| RAPD | Relative afferent pupillary defect |

| RION | Relapsing isolated optic neuritis |

| RNFL | Retinal nerve fiber layer |

| RON | Relapsing ON |

| SS | Sjogren syndrome |

| Tdap | Tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis |

| VA | Visual acuity |

| VAERS | Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System |

| VEP | Visual evoked potential |

| VZV | Varicella zoster virus |

References

- von Staden, H. Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria: Edition, Translation and Essays; Cambridge University Press: 1989.

- Beck, R.W.; Cleary, P.A.; Anderson, M.M., Jr.; Keltner, J.L.; Shults, W.T.; Kaufman, D.I.; Buckley, E.G.; Corbett, J.J.; Kupersmith, M.J.; Miller, N.R.; et al. A randomized, controlled trial of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute optic neuritis. The Optic Neuritis Study Group. The New England journal of medicine 1992, 326, 581-588. [CrossRef]

- Lennon, V.A.; Kryzer, T.J.; Pittock, S.J.; Verkman, A.S.; Hinson, S.R. IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2005, 202, 473-477. [CrossRef]

- Kitley, J.; Woodhall, M.; Waters, P.; Leite, M.I.; Devenney, E.; Craig, J.; Palace, J.; Vincent, A. Myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in adults with a neuromyelitis optica phenotype. Neurology 2012, 79, 1273-1277. [CrossRef]

- Petzold, A.; Fraser, C.L.; Abegg, M.; Alroughani, R.; Alshowaeir, D.; Alvarenga, R.; Andris, C.; Asgari, N.; Barnett, Y.; Battistella, R.; et al. Diagnosis and classification of optic neuritis. Lancet Neurol 2022, 21, 1120-1134. [CrossRef]

- De Lott, L.B.; Bennett, J.L.; Costello, F. The changing landscape of optic neuritis: a narrative review. Journal of Neurology 2022, 269, 111-124. [CrossRef]

- Benard-Seguin, E.; Costello, F. Optic neuritis: current challenges in diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Neurol 2023, 36, 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, G.S.; Raven, J.E.; Schofield, M. The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, 2 ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1983.

- Hippocrates. Volume X: Aphorisms and Other Works; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2012.

- Pormann, P.E.; Savage-Smith, E. Medieval Islamic Medicine; Edinburgh University Press: 2007.

- Temkin, O. Galenism: Rise and Decline of a Medical Philosophy; Cornell University Press: 1973.

- Gutas, D. Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ʻAbbāsid Society (2nd-4th/8th-10th Centuries); Routledge: London, 2001.

- Goldstein, I. The Book of the Ten Treatises on the Eye Ascribed to Hunain Ibn Is-Haq (809-877 A. D.). Archives of Ophthalmology 1929, 2, 114-117. [CrossRef]

- Wikimedia. Hunayn ibn Ishaq 9th century CE description of the eye diagram in a copy of his book, Kitab al-Ashr Maqalat fil-Ayn (Ten Treatises on the Eye), in a 12th century CE edition. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Hunayn_ibn_Ishaq_9th_century_CE_description_of_the_eye_diagram_in_a_copy_of_his_book,_Kitab_al-Ashr_Maqalat_fil-Ayn_(Ten_Treatises_on_the_Eye),_in_a_12th_century_CE_edition.jpg&oldid=844124575. (accessed on 26 September).

- Wikimedia. Double Opening of the ‘Memorandum for Oculists’ by Ali Ibn Isa al-Kahhal (CBL Ar 4002, ff.103b-104a).jpg. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Double_Opening_of_the_%27Memorandum_for_Oculists%27_by_Ali_Ibn_Isa_al-Kahhal_(CBL_Ar_4002,_ff.103b-104a).jpg&oldid=1032259355 (accessed on 26 September).

- Gruner, O.C. A Treatise on the Canon of Medicine of Avicenna: Incorporating a Translation of the First Book; AMS Press: 1973.

- Lindberg, D.C. Theories of Vision from Al-kindi to Kepler; University of Chicago Press: 1976.

- Leber, T. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Neuritis des Sehnerven. Archiv für Ophthalmologie 1868, 14, 333-378. [CrossRef]

- Duke-Elder, S. System of Ophthalmology: Neuro-ophthalmology; H. Kimpton: 1971.

- Compston, A.; Lassmann, H.; McDonald, I. Chapter 1 - The story of multiple sclerosis. In McAlpine’s Multiple Sclerosis (Fourth Edition), Compston, A., Confavreux, C., Lassmann, H., McDonald, I., Miller, D., Noseworthy, J., Smith, K., Wekerle, H., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, 2006; pp. 3-68.

- Nettleship, E. On cases of retro-ocular neuritis. Trans Ophthal Soc UK 1884, 4, 186-226.

- Uhthoff, W. Untersuchungen über die bei der multiplen Herdsklerose vorkonimenden Augenstörungen. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 1890, 21, 305-410.

- Opara, J.A.; Brola, W.; Wylegala, A.A.; Wylegala, E. Uhthoff`s phenomenon 125 years later - what do we know today? J Med Life 2016, 9, 101-105.

- Pulfrich, C. Die Stereoskopie im Dienste der isochromen und heterochromen Photometrie. Naturwissenschaften 1922, 10, 553-564. [CrossRef]

- Charcot, J.M. Leçons sur les maladies du système nerveux; Médical, B.d.P., Ed.; Paris: Bureaux du Progrès Médical, 1868.

- Zalc, B. One hundred and fifty years ago Charcot reported multiple sclerosis as a new neurological disease. Brain 2018, 141, 3482-3488. [CrossRef]

- Percy, A.K.; Nobrega, F.T.; Kurland, L.T. Optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis. An epidemiologic study. Arch Ophthalmol 1972, 87, 135-139. [CrossRef]

- Kahana, E.; Alter, M.; Feldman, S. Optic neuritis in relation to multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology 1976, 213, 87-95. [CrossRef]

- Arnason, B.G. Editorial: Optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis. The New England journal of medicine 1973, 289, 1140-1141. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.; Carter, S. Relation of optic neuritis to multiple sclerosis in children. Pediatrics 1961, 28, 377-387.

- Kale, N. Optic neuritis as an early sign of multiple sclerosis. Eye Brain 2016, 8, 195-202. [CrossRef]

- Alshyaokh, F.; Alhussein, M.; Almulla, A.; Alhelal, F.; Alqhtani, M.; Abulaban, A. 3. Outcome of Multiple Sclerosis with and without Optic Neuritis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2024, 92. [CrossRef]

- SMITH, E.L. INTRAVENOUS USE OF CORTICOTROPIN IN OPTIC NEURITIS. A.M.A. Archives of Ophthalmology 1953, 49, 303-312. [CrossRef]

- Rawson, M.D.; Liversedge, L.A. TREATMENT OF RETROBULBAR NEURITIS WITH CORTICOTROPHIN. The Lancet 1969, 294, 222. [CrossRef]

- The Optic Neuritis Study Group. The clinical profile of optic neuritis. Experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Optic Neuritis Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol 1991, 109, 1673-1678. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Group, T.O.N.S. Corticosteroid treatment of optic neuritis. Neurology 1992, 42, 1133-1133, doi:doi:10.1212/WNL.42.6.1133.

- Beck, R.W.; Cleary, P.A.; Trobe, J.D.; Kaufman, D.I.; Kupersmith, M.J.; Paty, D.W.; Brown, C.H. The effect of corticosteroids for acute optic neuritis on the subsequent development of multiple sclerosis. The Optic Neuritis Study Group. The New England journal of medicine 1993, 329, 1764-1769. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Kupersmith, M.J.; Cleary, P.A.; Katz, B. Fellow eye abnormalities in acute unilateral optic neuritis. Experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. Ophthalmology 1993, 100, 691-697; discussion 697-698. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Arrington, J.; Murtagh, F.R.; Cleary, P.A.; Kaufman, D.I. Brain magnetic resonance imaging in acute optic neuritis. Experience of the Optic Neuritis Study Group. Arch Neurol 1993, 50, 841-846. [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P.A.; Beck, R.W.; Anderson, M.M., Jr.; Kenny, D.J.; Backlund, J.Y.; Gilbert, P.R. Design, methods, and conduct of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Control Clin Trials 1993, 14, 123-142. [CrossRef]

- Keltner, J.L.; Johnson, C.A.; Beck, R.W.; Cleary, P.A.; Spurr, J.O. Quality control functions of the Visual Field Reading Center (VFRC) for the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial (ONTT). Control Clin Trials 1993, 14, 143-159. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Cleary, P.A. Recovery from severe visual loss in optic neuritis. Arch Ophthalmol 1993, 111, 300. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Diehl, L.; Cleary, P.A. Optic Neuritis Study Group. Pelli-Robson normative data for young adults. . Clinical Vision Science 1993, 8, 207-210.

- Chrousos, G.A.; Kattah, J.C.; Beck, R.W.; Cleary, P.A. Side effects of glucocorticoid treatment. Experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Jama 1993, 269, 2110-2112.

- Beck, R.W.; Cleary, P.A. Optic neuritis treatment trial. One-year follow-up results. Arch Ophthalmol 1993, 111, 773-775. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Cleary, P.A.; Backlund, J.C. The course of visual recovery after optic neuritis. Experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Ophthalmology 1994, 101, 1771-1778. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W. The optic neuritis treatment trial: three-year follow-up results. Arch Ophthalmol 1995, 113, 136-137. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Trobe, J.D. The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Putting the results in perspective. The Optic Neuritis Study Group. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society 1995, 15, 131-135.

- Beck, R.W.; Trobe, J.D. What we have learned from the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Ophthalmology 1995, 102, 1504-1508. [CrossRef]

- Rolak, L.A.; Beck, R.W.; Paty, D.W.; Tourtellotte, W.W.; Whitaker, J.N.; Rudick, R.A. Cerebrospinal fluid in acute optic neuritis: experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. Neurology 1996, 46, 368-372. [CrossRef]

- Trobe, J.D.; Beck, R.W.; Moke, P.S.; Cleary, P.A. Contrast sensitivity and other vision tests in the optic neuritis treatment trial. Am J Ophthalmol 1996, 121, 547-553. [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P.A.; Beck, R.W.; Bourque, L.B.; Backlund, J.C.; Miskala, P.H. Visual symptoms after optic neuritis. Results from the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society 1997, 17, 18-23; quiz 24-18. [CrossRef]

- The Optic Neuritis Study Group. The 5-year risk of MS after optic neuritis. Experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. Neurology 1997, 49, 1404-1413. [CrossRef]

- The Optic Neuritis Study Group. Visual function 5 years after optic neuritis: experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. The Optic Neuritis Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol 1997, 115, 1545-1552.

- Cole, S.R.; Beck, R.W.; Moke, P.S.; Kaufman, D.I.; Tourtellotte, W.W. The predictive value of CSF oligoclonal banding for MS 5 years after optic neuritis. Optic Neuritis Study Group. Neurology 1998, 51, 885-887. [CrossRef]

- Long, D.T.; Beck, R.W.; Moke, P.S.; Blair, R.C.; Kip, K.E.; Gal, R.L.; Katz, B.J. The SKILL Card test in optic neuritis: experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Smith-Kettlewell Institute Low Luminance. Optic Neuritis Study Group. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society 2001, 21, 124-131. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Trobe, J.D.; Moke, P.S.; Gal, R.L.; Xing, D.; Bhatti, M.T.; Brodsky, M.C.; Buckley, E.G.; Chrousos, G.A.; Corbett, J.; et al. High- and low-risk profiles for the development of multiple sclerosis within 10 years after optic neuritis: experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2003, 121, 944-949. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Gal, R.L.; Bhatti, M.T.; Brodsky, M.C.; Buckley, E.G.; Chrousos, G.A.; Corbett, J.; Eggenberger, E.; Goodwin, J.A.; Katz, B.; et al. Visual function more than 10 years after optic neuritis: experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2004, 137, 77-83. [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Smith, C.H.; Gal, R.L.; Xing, D.; Bhatti, M.T.; Brodsky, M.C.; Buckley, E.G.; Chrousos, G.A.; Corbett, J.; Eggenberger, E.; et al. Neurologic impairment 10 years after optic neuritis. Arch Neurol 2004, 61, 1386-1389. [CrossRef]

- The Optic Neuritis Study Group. Visual function 15 years after optic neuritis: a final follow-up report from the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1079-1082.e1075. [CrossRef]

- The Optic Neuritis Study Group. Multiple sclerosis risk after optic neuritis: final optic neuritis treatment trial follow-up. Arch Neurol 2008, 65, 727-732. [CrossRef]

- Keltner, J.L.; Johnson, C.A.; Cello, K.E.; Dontchev, M.; Gal, R.L.; Beck, R.W. Visual field profile of optic neuritis: a final follow-up report from the optic neuritis treatment trial from baseline through 15 years. Arch Ophthalmol 2010, 128, 330-337. [CrossRef]

- Keltner, J.L.; Johnson, C.A.; Spurr, J.O.; Beck, R.W. Baseline visual field profile of optic neuritis. The experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. Optic Neuritis Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol 1993, 111, 231-234. [CrossRef]

- Heussinger, N.; Kontopantelis, E.; Gburek-Augustat, J.; Jenke, A.; Vollrath, G.; Korinthenberg, R.; Hofstetter, P.; Meyer, S.; Brecht, I.; Kornek, B.; et al. Oligoclonal bands predict multiple sclerosis in children with optic neuritis. Ann Neurol 2015, 77, 1076-1082. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Yen, M.Y.; Hsu, W.M.; Lee, H.C.; Wang, A.G. Low conversion rate to multiple sclerosis in idiopathic optic neuritis patients in Taiwan. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2006, 50, 170-175. [CrossRef]

- Elpers C; Amler S; Grenzebach U; Allkemper T; Fiedler B; Schwartz O; Meuth SG; Kurlemann G. Prediction of Multiple Sclerosis after Childhood Isolated Optic Neuritis. Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine 2015, 1. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H.G.; Knier, B.; Oberwahrenbrock, T.; Behrens, J.; Pfuhl, C.; Aly, L.; Kaminski, M.; Hoshi, M.M.; Specovius, S.; Giess, R.M.; et al. Association of Retinal Ganglion Cell Layer Thickness With Future Disease Activity in Patients With Clinically Isolated Syndrome. JAMA Neurol 2018, 75, 1071-1079. [CrossRef]

- Pihl-Jensen, G.; Wanscher, B.; Frederiksen, J.L. Predictive value of optical coherence tomography, multifocal visual evoked potentials, and full-field visual evoked potentials of the fellow, non-symptomatic eye for subsequent multiple sclerosis development in patients with acute optic neuritis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2021, 27, 391-400. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, W.I.; Compston, A.; Edan, G.; Goodkin, D.; Hartung, H.P.; Lublin, F.D.; McFarland, H.F.; Paty, D.W.; Polman, C.H.; Reingold, S.C.; et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001, 50, 121-127. [CrossRef]

- Polman, C.H.; Reingold, S.C.; Edan, G.; Filippi, M.; Hartung, H.P.; Kappos, L.; Lublin, F.D.; Metz, L.M.; McFarland, H.F.; O’Connor, P.W.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria”. Ann Neurol 2005, 58, 840-846. [CrossRef]

- Polman, C.H.; Reingold, S.C.; Banwell, B.; Clanet, M.; Cohen, J.A.; Filippi, M.; Fujihara, K.; Havrdova, E.; Hutchinson, M.; Kappos, L.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011, 69, 292-302. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol 2018, 17, 162-173. [CrossRef]

- Montalban, X.; Lebrun-Frénay, C.; Oh, J.; Arrambide, G.; Moccia, M.; Pia Amato, M.; Amezcua, L.; Banwell, B.; Bar-Or, A.; Barkhof, F.; et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2024 revisions of the McDonald criteria. The Lancet Neurology 2025, 24, 850-865. [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, W.J.; Vidal-Jordana, A.; Shatila, M.; Strijbis, E.; Schoof, L.; Killestein, J.; Barkhof, F.; Bollo, L.; Rovira, A.; Sastre-Garriga, J.; et al. Towards a Unified Set of Diagnostic Criteria for Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2025, 97, 571-582. [CrossRef]

- Levraut, M.; Landes-Chateau, C.; Mondot, L.; Cohen, M.; Lebrun-Frenay, C. The Kappa Free Light Chains Index and Central Vein Sign: Two New Biomarkers for Multiple Sclerosis Diagnosis. Neurol Ther 2025, 14, 711-731. [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Jordana, A.; Rovira, A.; Calderon, W.; Arrambide, G.; Castilló, J.; Moncho, D.; Rahnama, K.; Collorone, S.; Toosy, A.T.; Ciccarelli, O.; et al. Adding the Optic Nerve in Multiple Sclerosis Diagnostic Criteria: A Longitudinal, Prospective, Multicenter Study. Neurology 2024, 102, e200805. [CrossRef]

- Sati, P.; Oh, J.; Constable, R.T.; Evangelou, N.; Guttmann, C.R.; Henry, R.G.; Klawiter, E.C.; Mainero, C.; Massacesi, L.; McFarland, H.; et al. The central vein sign and its clinical evaluation for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a consensus statement from the North American Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis Cooperative. Nat Rev Neurol 2016, 12, 714-722. [CrossRef]

- Maggi, P.; Absinta, M.; Grammatico, M.; Vuolo, L.; Emmi, G.; Carlucci, G.; Spagni, G.; Barilaro, A.; Repice, A.M.; Emmi, L.; et al. Central vein sign differentiates Multiple Sclerosis from central nervous system inflammatory vasculopathies. Ann Neurol 2018, 83, 283-294. [CrossRef]

- Absinta, M.; Sati, P.; Masuzzo, F.; Nair, G.; Sethi, V.; Kolb, H.; Ohayon, J.; Wu, T.; Cortese, I.C.M.; Reich, D.S. Association of Chronic Active Multiple Sclerosis Lesions With Disability In Vivo. JAMA Neurology 2019, 76, 1474-1483. [CrossRef]

- Rjeily, N.B.; Solomon, A.J. Correction to: Misdiagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: Past, Present, and Future. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2024, 24, 559. [CrossRef]

- Sinnecker, T.; Clarke, M.A.; Meier, D.; Enzinger, C.; Calabrese, M.; De Stefano, N.; Pitiot, A.; Giorgio, A.; Schoonheim, M.M.; Paul, F.; et al. Evaluation of the Central Vein Sign as a Diagnostic Imaging Biomarker in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2019, 76, 1446-1456. [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.W. Perivascular iron deposition and other vascular damage in multiple sclerosis. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 1988, 51, 260-265. [CrossRef]

- Castellaro, M.; Tamanti, A.; Pisani, A.I.; Pizzini, F.B.; Crescenzo, F.; Calabrese, M. The Use of the Central Vein Sign in the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Belov, S.E.; Boyko, A.N.; Dolgushin, M.B. [The central vein sign in the differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis]. Zhurnal nevrologii i psikhiatrii imeni S.S. Korsakova / Ministerstvo zdravookhraneniia i meditsinskoi promyshlennosti Rossiiskoi Federatsii, Vserossiiskoe obshchestvo nevrologov [i] Vserossiiskoe obshchestvo psikhiat 2024, 124, 58-65. [CrossRef]

- Preziosa, P.; Pagani, E.; Meani, A.; Margoni, M.; Rubin, M.; Esposito, F.; Palombo, M.; Filippi, M.; Rocca, M.A. Soma and neurite density abnormalities of paramagnetic rim lesions and core-sign lesions in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2025, 272, 145. [CrossRef]

- Rocca, M.A.; Preziosa, P.; Filippi, M. Juxtacortical Paramagnetic Rim: A New MRI Marker to Characterize Focal Cortical Pathology in Multiple Sclerosis? Neurology 2024, 102, e208085. [CrossRef]

- Krajnc, N.; Schmidbauer, V.; Leinkauf, J.; Haider, L.; Bsteh, G.; Kasprian, G.; Leutmezer, F.; Kornek, B.; Rommer, P.S.; Berger, T.; et al. Paramagnetic rim lesions lead to pronounced diffuse periplaque white matter damage in multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2023, 29, 1406-1417. [CrossRef]

- Absinta, M.; Sati, P.; Fechner, A.; Schindler, M.K.; Nair, G.; Reich, D.S. Identification of Chronic Active Multiple Sclerosis Lesions on 3T MRI. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology 2018, 39, 1233-1238. [CrossRef]

- Dal-Bianco, A.; Grabner, G.; Kronnerwetter, C.; Weber, M.; Höftberger, R.; Berger, T.; Auff, E.; Leutmezer, F.; Trattnig, S.; Lassmann, H.; et al. Slow expansion of multiple sclerosis iron rim lesions: pathology and 7 T magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Neuropathol 2017, 133, 25-42. [CrossRef]

- Maggi, P.; Sati, P.; Nair, G.; Cortese, I.C.M.; Jacobson, S.; Smith, B.R.; Nath, A.; Ohayon, J.; van Pesch, V.; Perrotta, G.; et al. Paramagnetic Rim Lesions are Specific to Multiple Sclerosis: An International Multicenter 3T MRI Study. Annals of Neurology 2020, 88, 1034-1042. [CrossRef]

- Meaton, I.; Altokhis, A.; Allen, C.M.; Clarke, M.A.; Sinnecker, T.; Meier, D.; Enzinger, C.; Calabrese, M.; De Stefano, N.; Pitiot, A.; et al. Paramagnetic rims are a promising diagnostic imaging biomarker in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2022, 28, 2212-2220. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J.A.; Mohebbi, M.; Wicks, T.; Salman, F.; Bartnik, A.; Jakimovski, D.; Bergsland, N.; Schweser, F.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Dwyer, M.G.; et al. Paramagnetic rim lesions predict greater long-term relapse rates and clinical progression over 10 years. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2024, 30, 535-545. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J.A.; Bartnik, A.; Jakimovski, D.; Mohebbi, M.; Bergsland, N.; Salman, F.; Schweser, F.; Wilding, G.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Dwyer, M.G.; et al. Associations Between Paramagnetic Rim Lesion Evolution and Clinical and Radiologic Disease Progression in Persons With Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 2024, 103, e210004, doi:doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000210004.

- Klistorner, S.; Usnich, T.; Clarke, M.A.; Pareto, D.; Rovira, À.; Paul, F.; Barnett, M.; Klistorner, A. The Presence of a Paramagnetic Phase Rim is Linked to Lesion Age in Multiple Sclerosis. medRxiv 2025, 2025.2001.2012.25320426. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.; Belachew, S.; Wolinsky, J.S.; Hauser, S.L.; Kappos, L.; Barkhof, F.; Bernasconi, C.; Fecker, J.; Model, F.; Wei, W.; et al. Chronic white matter lesion activity predicts clinical progression in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain 2019, 142, 2787-2799. [CrossRef]

- Hemond, C.C.; Dundamadappa, S.K.; Deshpande, M.; Baek, J.; Brown, R.H., Jr.; Ionete, C.; Reich, D.S. Paramagnetic rim lesions are highly specific for multiple sclerosis in real-world data. Brain Commun 2025, 7, fcaf211. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.; Rudko, D.A.; Arnold, D.L.; Fetco, D.; Elkady, A.M.; Araujo, D.; Zhu, B.; Gafson, A.; Tian, Z.; Belachew, S.; et al. Lesion-level correspondence and longitudinal properties of paramagnetic rim and slowly expanding lesions in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2023, 29, 680-690. [CrossRef]

- Bacchetti, A.; McCormack, B.; Lin, T.-Y.; Doosti, R.; Ahmadi, G.; Ezzedin, O.; Pellegrini, N.; Johnson, E.; Kim, A.; Otero-Duran, G.; et al. Test–retest reliability of Cirrus HD-optical coherence tomography retinal layer thickness measurements in people with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical 2025, 11, 20552173251340957. [CrossRef]

- Kupersmith, M.J.; Garvin, M.K.; Wang, J.-K.; Durbin, M.; Kardon, R. Retinal ganglion cell layer thinning within one month of presentation for optic neuritis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2016, 22, 641-648. [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.; Gim, Y.; Park, K.-A.; Yang, H.K.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, S.-M.; Jung, J.H. Recurrence-Independent Progressive Inner-Retinal Thinning After Optic Neuritis: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 2025, 45, 190-196. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Dalmau, B.; Martinez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Torres-Torres, R.; Ortiz-Perez, S.; Zubizarreta, I.; Pulido-Valdeolivas, I.V.; Alba-Arbalat, S.; Guerrero-Zamora, A.; Calbet, D.; Villoslada, P. Early retinal atrophy predicts long-term visual impairment after acute optic neuritis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2018, 24, 1196-1204. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Ji, Y.S.; Park, S.W.; Heo, H. Retinal ganglion cell and axonal loss in optic neuritis: risk factors and visual functions. Eye 2017, 31, 467-474. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.C.; Kardon, R.H.; Leavitt, J.A.; Flanagan, E.P.; Pittock, S.J.; Chen, J.J. Optical coherence tomography is highly sensitive in detecting prior optic neuritis. Neurology 2019, 92, e527-e535, doi:doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006873.

- Bsteh, G.; Hegen, H.; Altmann, P.; Auer, M.; Berek, K.; Zinganell, A.; Pauli, F.D.; Rommer, P.; Deisenhammer, F.; Leutmezer, F.; et al. Validation of inter-eye difference thresholds in optical coherence tomography for identification of optic neuritis in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020, 45, 102403. [CrossRef]

- Saidha, S.; Naismith, R.T. Optical coherence tomography for diagnosing optic neuritis. Neurology 2019, 92, 253-254, doi:doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006866.

- Andorrà, M.; Alba-Arbalat, S.; Camos-Carreras, A.; Gabilondo, I.; Fraga-Pumar, E.; Torres-Torres, R.; Pulido-Valdeolivas, I.; Tercero-Uribe, A.I.; Guerrero-Zamora, A.M.; Ortiz-Perez, S.; et al. Using Acute Optic Neuritis Trials to Assess Neuroprotective and Remyelinating Therapies in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2020, 77, 234-244. [CrossRef]

- Presslauer, S.; Milosavljevic, D.; Brücke, T.; Bayer, P.; Hübl, W. Elevated levels of kappa free light chains in CSF support the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology 2008, 255, 1508-1514. [CrossRef]

- Konen, F.F.; Schwenkenbecher, P.; Jendretzky, K.F.; Gingele, S.; Sühs, K.-W.; Tumani, H.; Süße, M.; Skripuletz, T. The Increasing Role of Kappa Free Light Chains in the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Cells 2021, 10, 3056.

- Leurs, C.; Twaalfhoven, H.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.; van Pesch, V.; Dujmovic, I.; Drulovic, J.; Castellazzi, M.; Bellini, T.; Pugliatti, M.; Kuhle, J.; et al. Kappa free light chains is a valid tool in the diagnostics of MS: A large multicenter study. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2020, 26, 912-923. [CrossRef]

- Hegen, H.; Arrambide, G.; Gnanapavan, S.; Kaplan, B.; Khalil, M.; Saadeh, R.; Teunissen, C.; Tumani, H.; Villar, L.M.; Willrich, M.A.V.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid kappa free light chains for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: A consensus statement. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2023, 29, 182-195. [CrossRef]

- Nabizadeh, F.; Mohammadi, M.; Maleki, T.; Valizadeh, P.; Sodeifian, F. Diagnostic value of kappa free light chain and kappa index in Multiple Sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology Letters 2024, 3, 50-63. [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.A.; Ahmed, S.; Muneer, S.; Khan, S.; de Oliveira, M.H.S.; Kausar, R.; Siddiqui, I. Evaluation of CSF kappa free light chains for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS): a comparison with oligoclonal bands (OCB) detection via isoelectric focusing (IEF) coupled with immunoblotting. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2023, 76, 353-356. [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Vera, E.; Garcia-Ripoll, A.M.-E.; Enguix, A.; Abalos-Garcia, C.; Segovia-Cuevas, M.J. Application of κ free light chains in cerebrospinal fluid as a biomarker in multiple sclerosis diagnosis: development of a diagnosis algorithm. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) 2018, 56, 609-613, doi:doi:10.1515/cclm-2017-0285.

- Crespi, I.; Sulas, M.G.; Mora, R.; Naldi, P.; Vecchio, D.; Comi, C.; Cantello, R.; Bellomo, G. Combined use of Kappa Free Light Chain Index and Isoelectrofocusing of Cerebro-Spinal Fluid in Diagnosing Multiple Sclerosis: Performances and Costs. Clin Lab 2017, 63, 551-559. [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, I.; Rasch, S.; Axelsson, M.; Novakova, L.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Lycke, J. Kappa free light chain index as a diagnostic biomarker in multiple sclerosis: A real-world investigation. Journal of Neurochemistry 2021, 159, 618-628. [CrossRef]

- Maroto-García, J.; Mañez, M.; Martínez-Escribano, A.; Hachmaoui-Ridaoui, A.; Ortiz, C.; Ábalos-García, C.; Gónzález, I.; García de la Torre, Á.; Ruiz-Galdón, M. A sex-dependent algorithm including kappa free light chain for multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Scandinavian journal of immunology 2024, 100, e13421. [CrossRef]

- Keltner, J.L.; Johnson, C.A.; Spurr, J.O.; Beck, R.W. Visual field profile of optic neuritis. One-year follow-up in the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 1994, 112, 946-953. [CrossRef]

- Visual function 5 years after optic neuritis: experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. The Optic Neuritis Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol 1997, 115, 1545-1552.

- Balcer, L.J. Clinical practice. Optic neuritis. The New England journal of medicine 2006, 354, 1273-1280. [CrossRef]

- Hickman, S.J.; Ko, M.; Chaudhry, F.; Jay, W.M.; Plant, G.T. Optic Neuritis: An Update Typical and Atypical Optic Neuritis. Neuro-Ophthalmology 2008, 32, 237-248. [CrossRef]

- Ambika, S.; Lakshmi, P. Infectious optic neuropathy (ION), how to recognise it and manage it. Eye (Lond) 2024, 38, 2302-2311. [CrossRef]

- Kahloun, R.; Abroug, N.; Ksiaa, I.; Mahmoud, A.; Zeghidi, H.; Zaouali, S.; Khairallah, M. Infectious optic neuropathies: a clinical update. Eye Brain 2015, 7, 59-81. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Fu, X.; Zou, L.; Xu, Q. Teaching NeuroImage: Rapid Identification of Infectious Optic Neuritis by Next-Generation Sequencing. Neurology 2022, 98, e872-e874. [CrossRef]

- The 5-year risk of MS after optic neuritis. Experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. Neurology 1997, 49, 1404-1413. [CrossRef]

- Visual function 15 years after optic neuritis: a final follow-up report from the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1079-1082.e1075. [CrossRef]

- Multiple sclerosis risk after optic neuritis: final optic neuritis treatment trial follow-up. Arch Neurol 2008, 65, 727-732. [CrossRef]

- Lennon, V.A.; Wingerchuk, D.M.; Kryzer, T.J.; Pittock, S.J.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Fujihara, K.; Nakashima, I.; Weinshenker, B.G. A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2004, 364, 2106-2112. [CrossRef]

- Cree, B.A.C.; Bennett, J.L.; Kim, H.J.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Pittock, S.J.; Wingerchuk, D.M.; Fujihara, K.; Paul, F.; Cutter, G.R.; Marignier, R.; et al. Inebilizumab for the treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (N-MOmentum): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled phase 2/3 trial. The Lancet 2019, 394, 1352-1363. [CrossRef]

- Jurynczyk, M.; Messina, S.; Woodhall, M.R.; Raza, N.; Everett, R.; Roca-Fernandez, A.; Tackley, G.; Hamid, S.; Sheard, A.; Reynolds, G.; et al. Clinical presentation and prognosis in MOG-antibody disease: a UK study. Brain 2017, 140, 3128-3138. [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.A.; Salomao, D.R.; Parisi, J.E.; Kryzer, T.J.; Bradley, E.A.; Mines, J.A.; Lam, B.L.; Lennon, V.A. Paraneoplastic autoimmune optic neuritis with retinitis defined by CRMP-5-IgG. Ann Neurol 2003, 54, 38-50. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Bhatti, M.T.; Pulido, J.S.; Lennon, V.A.; Dubey, D.; Flanagan, E.P.; Pittock, S.J.; Klein, C.J.; Chen, J.J. Collapsin Response-Mediator Protein 5-Associated Retinitis, Vitritis, and Optic Disc Edema. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 221-229. [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Masciocchi, S.; Diamanti, L.; Bini, P.; Vegezzi, E.; Marchioni, E.; Colombo, E.; Rigoni, E.; Businaro, P.; Ferraro, O.E.; et al. Visual System Involvement in Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Astrocytopathy: Two Case Reports and a Systematic Literature Review. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Li, Z.; Lai, C. Isolated optic neuritis with positive glial fibrillary acidic protein antibody. BMC Ophthalmology 2023, 23, 184. [CrossRef]

- White, D.; Mollan, S.P.; Ramalingam, S.; Nagaraju, S.; Hayton, T.; Jacob, S. Enlarged and Enhancing Optic Nerves in Advanced Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Meningoencephalomyelitis. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society 2019, 39, 411-415. [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Jian, S.; Yang, T.; Zhao, X. Clinical characteristics and MRI features of autoimmune glial fibrillary acidic protein astrocytopathy: a case series of 34 patients. Front Neurol 2024, 15, 1375971. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, E.P.; Hinson, S.R.; Lennon, V.A.; Fang, B.; Aksamit, A.J.; Morris, P.P.; Basal, E.; Honorat, J.A.; Alfugham, N.B.; Linnoila, J.J.; et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoglobulin G as biomarker of autoimmune astrocytopathy: Analysis of 102 patients. Ann Neurol 2017, 81, 298-309. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Hernandez, E.; Sepulveda, M.; Rostásy, K.; Höftberger, R.; Graus, F.; Harvey, R.J.; Saiz, A.; Dalmau, J. Antibodies to aquaporin 4, myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, and the glycine receptor α1 subunit in patients with isolated optic neuritis. JAMA Neurol 2015, 72, 187-193. [CrossRef]

- Piquet, A.L.; Khan, M.; Warner, J.E.A.; Wicklund, M.P.; Bennett, J.L.; Leehey, M.A.; Seeberger, L.; Schreiner, T.L.; Paz Soldan, M.M.; Clardy, S.L. Novel clinical features of glycine receptor antibody syndrome: A series of 17 cases. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2019, 6, e592. [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.; Elsone, L.; Waters, P.; Woodhall, M.W.; Mutch, K.; Rafferty, C.; Tang, L.; Solomon, T.; Vincent, A.; Jacob, A. GLYCINE RECEPTOR ANTIBODY—A MARKER FOR NMO/ NON-MS DEMYELINATION? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2015, 86, e4-e4. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.B.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Z. Case Report: Severe Optic Neuritis after Multiple Episodes of Malaria in a Traveler to Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2023, 108, 868-870. [CrossRef]

- Melzi, S.; Aboura, R.; Ladjouze, A.; Bouhafs, N.; Boulesnane, K.; Bouadjar, R.; Mebrouki, L.; Beddek, Z.; Haddad, N.; Tabti, M.; et al. 66 Optic neuritis in children. Rheumatology 2022, 61. [CrossRef]

- Kerrison, J.B.; Lounsbury, D.; Thirkill, C.E.; Lane, R.G.; Schatz, M.P.; Engler, R.M. Optic neuritis after anthrax vaccination. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 99-104. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Sharma, N.; Shaia, J.K.; Cohen, D.A.; Singh, R.P.; Talcott, K.E. The Risk of Optic Neuritis following mRNA Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination Compared to Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection and Other Vaccinations. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 1076-1082. [CrossRef]

- Stübgen, J.P. A literature review on optic neuritis following vaccination against virus infections. Autoimmun Rev 2013, 12, 990-997. [CrossRef]

- Karussis, D.; Petrou, P. The spectrum of post-vaccination inflammatory CNS demyelinating syndromes. Autoimmun Rev 2014, 13, 215-224. [CrossRef]

- Matiello, M.; Lennon, V.A.; Jacob, A.; Pittock, S.J.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Wingerchuk, D.M.; Weinshenker, B.G. NMO-IgG predicts the outcome of recurrent optic neuritis. Neurology 2008, 70, 2197-2200. [CrossRef]

- Benoilid, A.; Tilikete, C.; Collongues, N.; Arndt, C.; Vighetto, A.; Vignal, C.; de Seze, J. Relapsing optic neuritis: a multicentre study of 62 patients. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2014, 20, 848-853. [CrossRef]

- Chalmoukou, K.; Alexopoulos, H.; Akrivou, S.; Stathopoulos, P.; Reindl, M.; Dalakas, M.C. Anti-MOG antibodies are frequently associated with steroid-sensitive recurrent optic neuritis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015, 2, e131. [CrossRef]

- Kidd, D.; Burton, B.; Plant, G.T.; Graham, E.M. Chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy (CRION). Brain 2003, 126, 276-284. [CrossRef]

- Petzold, A.; Plant, G.T. Chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy: a systematic review of 122 cases reported. J Neurol 2014, 261, 17-26. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, B.; Waters, P.; Woodhall, M.; Irani, S.; Ahn, S.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.M. Chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy (CRION): a manifestation of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies. J Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 302. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.L.; Costello, F.; Chen, J.J.; Petzold, A.; Biousse, V.; Newman, N.J.; Galetta, S.L. Optic neuritis and autoimmune optic neuropathies: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2023, 22, 89-100. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Optic Perineuritis and Its Association With Autoimmune Diseases. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 627077. [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.S.; Lee, C.M.; Chen, P.H.; Yang, Y.; Dong, Y.W.; Wang, Y.H.; Wei, J.C.; Zheng, W.J. Risk of Autoimmune Diseases Following Optic Neuritis: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 903608. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Woodhall, M.R.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, S.J.; Park, K.S.; Vincent, A.; Lee, K.W.; Waters, P. Antibodies to MOG in adults with inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015, 2, e163. [CrossRef]

- Hickman, S.J.; Petzold, A. Update on Optic Neuritis: An International View. Neuroophthalmology 2022, 46, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Petzold, A.; Plant, G.T. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune optic neuropathy. Autoimmunity Reviews 2014, 13, 539-545. [CrossRef]

- Hickman, S.J.; Dalton, C.M.; Miller, D.H.; Plant, G.T. Management of acute optic neuritis. Lancet 2002, 360, 1953-1962. [CrossRef]

- Toosy, A.T.; Mason, D.F.; Miller, D.H. Optic neuritis. Lancet Neurology 2014, 13, 83-99.

- Terrim, S.; Silva, G.D.; de Sá e Benevides Falcao, F.C.; dos Reis Pereira, C.; de Souza Andrade Benassi, T.; Fortini, I.; Gonçalves, M.R.R.; Castro, L.H.M.; Comerlatti, L.R.; de Medeiros Rimkus, C.; et al. Real-world application of the 2022 diagnostic criteria for first-ever episode of optic neuritis. Journal of Neuroimmunology 2023, 381. [CrossRef]

- Klyscz, P.; Asseyer, S.; Alonso, R.; Bereuter, C.; Bialer, O.; Bick, A.; Carta, S.; Chen, J.J.; Cohen, L.; Cohen-Tayar, Y.; et al. Application of the international criteria for optic neuritis in the Acute Optic Neuritis Network. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology 2024, 11, 2473-2484. [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi, A.; Martinelli, V.; Rodegher, M.; Zaffaroni, M.; Comi, G. The prognosis of idiopathic optic neuritis. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology 2000, 21, S865-869. [CrossRef]

- Siuko, M.; Kivelä, T.T.; Setälä, K.; Tienari, P.J. The clinical spectrum and prognosis of idiopathic acute optic neuritis: A longitudinal study in Southern Finland. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019, 35, 215-220. [CrossRef]

- Jendretzky, K.F.; Bajor, A.; Lezius, L.M.; Hümmert, M.W.; Konen, F.F.; Grosse, G.M.; Schwenkenbecher, P.; Sühs, K.W.; Trebst, C.; Framme, C.; et al. Clinical and paraclinical characteristics of optic neuritis in the context of the McDonald criteria 2017. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 7293. [CrossRef]

- Lebranchu, P.; Mazhar, D.; Wiertlewski, S.; Le Meur, G.; Couturier, J.; Ducloyer, J.B. One-year risk of multiple sclerosis after a first episode of optic neuritis according to modern diagnosis criteria. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2025, 93, 106213. [CrossRef]

- Stubgen, J.P. A literature review on optic neuritis following vaccination against virus infections. Autoimmunity Reviews 2013, 12, 990-997. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Tobin, W.O.; Majed, M.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Fryer, J.P.; Leavitt, J.A.; Flanagan, E.P.; McKeon, A.; Pittock, S.J. Prevalence of Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein and Aquaporin-4-IgG in Patients in the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Jama Ophthalmology 2018, 136, 419-422. [CrossRef]

- Wingerchuk, D.M.; Lennon, V.A.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Pittock, S.J.; Weinshenker, B.G. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol 2007, 6, 805-815. [CrossRef]

- Filippatou, A.G.; Mukharesh, L.; Saidha, S.; Calabresi, P.A.; Sotirchos, E.S. AQP4-IgG and MOG-IgG Related Optic Neuritis-Prevalence, Optical Coherence Tomography Findings, and Visual Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 540156. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.B.; Stern, C.; Flanagan, E.P.; Pittock, S.J.; Kunchok, A.; Foster, R.C.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Hodge, D.O.; Bhatti, M.T.; Chen, J.J. Population-Based Incidence of Optic Neuritis in the Era of Aquaporin-4 and Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibodies. Am J Ophthalmol 2020, 220, 110-114. [CrossRef]

- Oertel, F.C.; Zimmermann, H.; Paul, F.; Brandt, A.U. Optical coherence tomography in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: potential advantages for individualized monitoring of progression and therapy. Epma j 2018, 9, 21-33. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Suarez, S.; Guevara-Silva, E.; Osorio-Marcatinco, V.; Alvarez-Toledo, K.; Meza-Vega, M.; Caparó-Zamalloa, C. Clinical and paraclinical profile of neuromyelitis optic spectrum disorder in a peruvian cohort. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2022, 64, 103919. [CrossRef]

- Cam, S.; Gulec, B.; Tutuncu, M.; Saip, S.; Siva, A.; Uygunoglu, U. Disease Characteristics of Seropositive Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder in a Turkish Cohort. Neurology 2022, 99, S5-S5, doi:doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000903076.79930.c1.

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, S.; Yin, D.; Chen, X.; Xu, Q.; Chen, T.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Peng, C.; et al. Optic neuritis: a 5-year follow-up study of Chinese patients based on aquaporin-4 antibody status and ages. J Neurol 2016, 263, 1382-1389. [CrossRef]

- Arnett, S.; Chew, S.H.; Leitner, U.; Hor, J.Y.; Paul, F.; Yeaman, M.R.; Levy, M.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Banwell, B.L.; Fujihara, K.; et al. Sex ratio and age of onset in AQP4 antibody-associated NMOSD: a review and meta-analysis. J Neurol 2024, 271, 4794-4812. [CrossRef]

- Borisow, N.; Kleiter, I.; Gahlen, A.; Fischer, K.; Wernecke, K.D.; Pache, F.; Ruprecht, K.; Havla, J.; Krumbholz, M.; Kümpfel, T.; et al. Influence of female sex and fertile age on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2017, 23, 1092-1103. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Mealy, M.A.; Levy, M.; Schmidt, F.; Ruprecht, K.; Paul, F.; Ringelstein, M.; Aktas, O.; Hartung, H.P.; Asgari, N.; et al. Racial differences in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Neurology 2018, 91, e2089-e2099. [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, M.P.; Schimidt, S.; Alvarenga, R.P. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica in Latin America. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 2017, 3, 2055217317730098. [CrossRef]

- Lana-Peixoto, M.A.; Talim, N.C.; Pedrosa, D.; Macedo, J.M.; Santiago-Amaral, J. Prevalence of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder in Belo Horizonte, Southeast Brazil. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 50, 102807. [CrossRef]

- Hor, J.Y.; Asgari, N.; Nakashima, I.; Broadley, S.A.; Leite, M.I.; Kissani, N.; Jacob, A.; Marignier, R.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Paul, F.; et al. Epidemiology of Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder and Its Prevalence and Incidence Worldwide. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 501. [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, M.; Armangué, T.; Sola-Valls, N.; Arrambide, G.; Meca-Lallana, J.E.; Oreja-Guevara, C.; Mendibe, M.; Alvarez de Arcaya, A.; Aladro, Y.; Casanova, B.; et al. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation 2016, 3, e225, doi:doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000225.

- Poisson, K.; Moeller, K.; Fisher, K.S. Pediatric Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2023, 46, 101051. [CrossRef]

- Hinson, S.R.; Pittock, S.J.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Roemer, S.F.; Fryer, J.P.; Kryzer, T.J.; Lennon, V.A. Pathogenic potential of IgG binding to water channel extracellular domain in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2007, 69, 2221-2231. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, M.C.; Verkman, A.S. Aquaporin 4 and neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurology 2012, 11, 535-544.

- Jarius, S.; Paul, F.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Levy, M.; Kim, H.J.; Wildemann, B. Neuromyelitis optica. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 85. [CrossRef]

- Saadoun, S.; Papadopoulos, M.C. Role of membrane complement regulators in neuromyelitis optica. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2015, 21, 1644-1654. [CrossRef]

- Asavapanumas, N.; Ratelade, J.; Papadopoulos, M.C.; Bennett, J.L.; Levin, M.H.; Verkman, A.S. Experimental mouse model of optic neuritis with inflammatory demyelination produced by passive transfer of neuromyelitis optica-immunoglobulin G. J Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 16. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Verkman, A.S. Complement regulator CD59 prevents peripheral organ injury in rats made seropositive for neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G. Acta neuropathologica communications 2017, 5, 57. [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Itokazu, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Hiraga, S.I.; Yamashita, T. A novel aquaporin-4-associated optic neuritis rat model with severe pathological and functional manifestations. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 263. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Qiu, W.; Peng, L.; Fang, L.; Xu, Y.; Yang, H. Structural and visual functional deficits in a rat model of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders related optic neuritis. Exp Eye Res 2018, 175, 124-132. [CrossRef]

- Soerensen, S.F.; Wirenfeldt, M.; Wlodarczyk, A.; Moerch, M.T.; Khorooshi, R.; Arengoth, D.S.; Lillevang, S.T.; Owens, T.; Asgari, N. An Experimental Model of Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder-Optic Neuritis: Insights Into Disease Mechanisms. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 703249. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, L.; Pan, Y.; Chen, P.; Luo, Y.; Li, S.; Zou, W.; Wang, K. Different immunological mechanisms between AQP4 antibody-positive and MOG antibody-positive optic neuritis based on RNA sequencing analysis of whole blood. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1095966. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yao, W.; Chen, F. Brief research report: WGCNA-driven identification of histone modification genes as potential biomarkers in AQP4-Associated optic neuritis. Front Genet 2024, 15, 1423584. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wu, Y.; Song, H.; Lai, M.; Li, H.; Sun, M.; Zhao, J.; Fu, J.; Xu, X.; Xie, L.; et al. Vision Prognosis and Associated Factors of Optic Neuritis in Dependence of Glial Autoimmune Antibodies. Am J Ophthalmol 2022, 239, 11-25. [CrossRef]

- Tajfirouz, D.; Padungkiatsagul, T.; Beres, S.; Moss, H.E.; Pittock, S.; Flanagan, E.; Kunchok, A.; Shah, S.; Bhatti, M.T.; Chen, J.J. Optic chiasm involvement in AQP-4 antibody-positive NMO and MOG antibody-associated disorder. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2022, 28, 149-153. [CrossRef]

- Akaishi, T.; Takeshita, T.; Himori, N.; Takahashi, T.; Misu, T.; Ogawa, R.; Kaneko, K.; Fujimori, J.; Abe, M.; Ishii, T.; et al. Rapid Administration of High-Dose Intravenous Methylprednisolone Improves Visual Outcomes After Optic Neuritis in Patients With AQP4-IgG-Positive NMOSD. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 932. [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.; Jang, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, S.J.; Jung, J.H. Long-Term Visual Prognosis in Patients With Aquaporin-4-Immunoglobulin G-Positive Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society 2022, 42, 303-309. [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.G.; Moon, Y.; Kwon, Y.N.; Lee, B.J.; Park, K.A.; Han, J.Y.; Han, J.; Lee, H.J.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, B.J.; et al. Prognostic factors of first-onset optic neuritis based on diagnostic criteria and antibody status: a multicentre analysis of 427 eyes. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2024, 95, 753-760. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, H.; Kezuka, T.; Shikishima, K.; Yamagami, A.; Hiraoka, M.; Chuman, H.; Nakamura, M.; Hoshi, K.; Goseki, T.; Mashimo, K.; et al. Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics of Optic Neuritis in Japan. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 1385-1398. [CrossRef]

- Kümpfel, T.; Giglhuber, K.; Aktas, O.; Ayzenberg, I.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Häußler, V.; Havla, J.; Hellwig, K.; Hümmert, M.W.; Jarius, S.; et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) - revised recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). Part II: Attack therapy and long-term management. J Neurol 2024, 271, 141-176. [CrossRef]

- Niino, M.; Isobe, N.; Araki, M.; Ohashi, T.; Okamoto, T.; Ogino, M.; Okuno, T.; Ochi, H.; Kawachi, I.; Shimizu, Y.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease 2023 in Japan. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2024, 90, 105829. [CrossRef]

- Paul, F.; Marignier, R.; Palace, J.; Arrambide, G.; Asgari, N.; Bennett, J.L.; Cree, B.A.C.; De Sèze, J.; Fujihara, K.; Kim, H.J.; et al. International Delphi Consensus on the Management of AQP4-IgG+ NMOSD: Recommendations for Eculizumab, Inebilizumab, and Satralizumab. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, J.M.; Talim, N.; Kleinpaul, R.; Lana-Peixoto, M.A. Optic neuritis at disease onset predicts poor visual outcome in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020, 41, 102045. [CrossRef]

- Ueki, S.; Hatase, T.; Kiyokawa, M.; Kawachi, I.; Saji, E.; Onodera, O.; Fukuchi, T.; Igarashi, H. Visual outcome of aquaporin-4 antibody-positive optic neuritis with maintenance therapy. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2021, 65, 699-703. [CrossRef]

- Mader, S.; Gredler, V.; Schanda, K.; Rostasy, K.; Dujmovic, I.; Pfaller, K.; Lutterotti, A.; Jarius, S.; Di Pauli, F.; Kuenz, B.; et al. Complement activating antibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in neuromyelitis optica and related disorders. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 14. [CrossRef]

- Sato, D.K.; Callegaro, D.; Lana-Peixoto, M.A.; Waters, P.J.; de Haidar Jorge, F.M.; Takahashi, T.; Nakashima, I.; Apostolos-Pereira, S.L.; Talim, N.; Simm, R.F.; et al. Distinction between MOG antibody-positive and AQP4 antibody-positive NMO spectrum disorders. Neurology 2014, 82, 474-481. [CrossRef]

- Dinoto, A.; Cacciaguerra, L.; Vorasoot, N.; Redenbaugh, V.; Lopez-Chiriboga, S.A.; Valencia-Sanchez, C.; Guo, K.; Thakolwiboon, S.; Horsman, S.E.; Syc-Mazurek, S.B.; et al. Clinical Features and Factors Associated With Outcome in Late Adult-Onset Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease. Neurology 2025, 104, e213557. [CrossRef]

- Ciotti, J.R.; Eby, N.S.; Wu, G.F.; Naismith, R.T.; Chahin, S.; Cross, A.H. Clinical and laboratory features distinguishing MOG antibody disease from multiple sclerosis and AQP4 antibody-positive neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020, 45, 102399. [CrossRef]

- Hor, J.Y.; Fujihara, K. Epidemiology of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: a review of prevalence and incidence worldwide. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1260358. [CrossRef]

- Ferilli, M.A.N.; Valeriani, M.; Papi, C.; Papetti, L.; Ruscitto, C.; Figà Talamanca, L.; Ursitti, F.; Moavero, R.; Vigevano, F.; Iorio, R. Clinical and neuroimaging characteristics of MOG autoimmunity in children with acquired demyelinating syndromes. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 50, 102837. [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Sankhyan, N.; Sukhija, J.; Saini, A.G.; Vyas, S.; Suthar, R.; Sahu, J.K.; Rawat, A. Clinical outcomes and Anti-MOG antibodies in pediatric optic neuritis: A prospective observational study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2024, 49, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Wendel, E.M.; Baumann, M.; Barisic, N.; Blaschek, A.; Coelho de Oliveira Koch, E.; Della Marina, A.; Diepold, K.; Hackenberg, A.; Hahn, A.; von Kalle, T.; et al. High association of MOG-IgG antibodies in children with bilateral optic neuritis. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2020, 27, 86-93. [CrossRef]

- Armangue, T.; Olivé-Cirera, G.; Martínez-Hernandez, E.; Sepulveda, M.; Ruiz-Garcia, R.; Muñoz-Batista, M.; Ariño, H.; González-Álvarez, V.; Felipe-Rucián, A.; Jesús Martínez-González, M.; et al. Associations of paediatric demyelinating and encephalitic syndromes with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol 2020, 19, 234-246. [CrossRef]

- de Mol, C.L.; Wong, Y.; van Pelt, E.D.; Wokke, B.; Siepman, T.; Neuteboom, R.F.; Hamann, D.; Hintzen, R.Q. The clinical spectrum and incidence of anti-MOG-associated acquired demyelinating syndromes in children and adults. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2020, 26, 806-814. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tan, S.; Chan, T.C.Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Teng, D.; Fu, H.; Wei, S. Clinical features of demyelinating optic neuritis with seropositive myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody in Chinese patients. The British journal of ophthalmology 2018, 102, 1372-1377. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, K.; Hamilton-Shield, A.; Woodhall, M.; Messina, S.; Mariano, R.; Waters, P.; Ramdas, S.; Leite, M.I.; Palace, J. Prevalence and incidence of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, aquaporin-4 antibody-positive NMOSD and MOG antibody-positive disease in Oxfordshire, UK. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2020, 91, 1126-1128. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, M.; Teng, D.; Song, H.; Xu, Q.; Wei, S. The prevalence and prognostic value of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody in adult optic neuritis. J Neurol Sci 2019, 396, 225-231. [CrossRef]

- Jarius, S.; Ruprecht, K.; Kleiter, I.; Borisow, N.; Asgari, N.; Pitarokoili, K.; Pache, F.; Stich, O.; Beume, L.A.; Hümmert, M.W.; et al. MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders: a multicenter study of 50 patients. Part 2: Epidemiology, clinical presentation, radiological and laboratory features, treatment responses, and long-term outcome. J Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 280. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Flanagan, E.P.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; López-Chiriboga, A.S.S.; Fryer, J.P.; Leavitt, J.A.; Weinshenker, B.G.; McKeon, A.; Tillema, J.M.; Lennon, V.A.; et al. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Positive Optic Neuritis: Clinical Characteristics, Radiologic Clues, and Outcome. Am J Ophthalmol 2018, 195, 8-15. [CrossRef]

- Virupakshaiah, A.; Schoeps, V.A.; Race, J.; Waltz, M.; Sharayah, S.; Nasr, Z.; Moseley, C.E.; Zamvil, S.S.; Gaudioso, C.; Schuette, A.; et al. Predictors of a relapsing course in myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2024, 96, 68-75. [CrossRef]

- Boudjani, H.; Fadda, G.; Dufort, G.; Antel, J.; Giacomini, P.; Levesque-Roy, M.; Oskoui, M.; Duquette, P.; Prat, A.; Girard, M.; et al. Clinical course, imaging, and pathological features of 45 adult and pediatric cases of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2023, 76, 104787. [CrossRef]

- Cacciaguerra, L.; Sechi, E.; Komla-Soukha, I.; Chen, J.J.; Smith, C.Y.; Jenkins, S.M.; Guo, K.; Redenbaugh, V.; Fryer, J.P.; Tillema, J.M.; et al. MOG antibody-associated disease epidemiology in Olmsted County, USA, and Martinique. J Neurol 2025, 272, 118. [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Yeo, T.; Yong, K.P.; Thomas, T.; Wang, F.; Tye, J.; Quek, A.M.L. Central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating diseases and neuroimmunology in Singapore—Epidemiology and evolution of an emerging subspecialty. Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience 2021, 9, 259-265. [CrossRef]

- Höftberger, R.; Guo, Y.; Flanagan, E.P.; Lopez-Chiriboga, A.S.; Endmayr, V.; Hochmeister, S.; Joldic, D.; Pittock, S.J.; Tillema, J.M.; Gorman, M.; et al. The pathology of central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating disease accompanying myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein autoantibody. Acta Neuropathol 2020, 139, 875-892. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.A.; Denkova, M.; Ramanathan, S.; Dale, R.C.; Brilot, F. Pathogenesis of autoimmune demyelination: from multiple sclerosis to neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Clin Transl Immunology 2021, 10, e1316. [CrossRef]

- Corbali, O.; Chitnis, T. Pathophysiology of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody disease. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1137998. [CrossRef]

- Banwell, B.; Bennett, J.L.; Marignier, R.; Kim, H.J.; Brilot, F.; Flanagan, E.P.; Ramanathan, S.; Waters, P.; Tenembaum, S.; Graves, J.S.; et al. Diagnosis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: International MOGAD Panel proposed criteria. Lancet Neurol 2023, 22, 268-282. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, H.; Motomura, M.; Tanaka, K.; Fujikawa, A.; Nakata, R.; Maeda, Y.; Shima, T.; Mukaino, A.; Yoshimura, S.; Miyazaki, T.; et al. Antibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in idiopathic optic neuritis. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007766. [CrossRef]

- Shor, N.; Aboab, J.; Maillart, E.; Lecler, A.; Bensa, C.; Le Guern, G.; Grunbaum, S.; Marignier, R.; Papeix, C.; Heron, E.; et al. Clinical, imaging and follow-up study of optic neuritis associated with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody: a multicentre study of 62 adult patients. European journal of neurology : the official journal of the European Federation of Neurological Societies 2020, 27, 384-391. [CrossRef]

- Jarius, S.; Pellkofer, H.; Siebert, N.; Korporal-Kuhnke, M.; Hümmert, M.W.; Ringelstein, M.; Rommer, P.S.; Ayzenberg, I.; Ruprecht, K.; Klotz, L.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid findings in patients with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies. Part 1: Results from 163 lumbar punctures in 100 adult patients. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 261. [CrossRef]

- Bruijstens, A.L.; Breu, M.; Wendel, E.M.; Wassmer, E.; Lim, M.; Neuteboom, R.F.; Wickström, R.; Baumann, M.; Bartels, F.; Finke, C.; et al. E.U. paediatric MOG consortium consensus: Part 4 - Outcome of paediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2020, 29, 32-40. [CrossRef]

- Akaishi, T.; Himori, N.; Takeshita, T.; Misu, T.; Takahashi, T.; Takai, Y.; Nishiyama, S.; Fujimori, J.; Ishii, T.; Aoki, M.; et al. Five-year visual outcomes after optic neuritis in anti-MOG antibody-associated disease. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 56, 103222. [CrossRef]

- Havla, J.; Pakeerathan, T.; Schwake, C.; Bennett, J.L.; Kleiter, I.; Felipe-Rucián, A.; Joachim, S.C.; Lotz-Havla, A.S.; Kümpfel, T.; Krumbholz, M.; et al. Age-dependent favorable visual recovery despite significant retinal atrophy in pediatric MOGAD: how much retina do you really need to see well? J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 121. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, L.; Huang, W.; Tan, H.; Chang, X.; ZhangBao, J.; Quan, C. Fewer relapses and worse outcomes of patients with late-onset myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2025, 96, 655-664. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L. Isolated myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated optic neuritis in adults: The importance of age of onset and prognosis-related radiological features. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2024, 85, 105518. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yin, Q.; Han, B.; Yuan, T.; Su, K.; Dai, W.; Wang, D.; Yang, L. MOG-IgG detection in serum and cerebrospinal fluid: diagnostic implications and clinical correlates in adult-onset Chinese MOGAD patients. J Neurol 2025, 272, 528. [CrossRef]

- Burton, J.M.; Youn, S.; Al-Ani, A.; Costello, F. Patterns and utility of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody testing in cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol 2024, 271, 2662-2671. [CrossRef]

- Takai, Y.; Misu, T.; Kaneko, K.; Chihara, N.; Narikawa, K.; Tsuchida, S.; Nishida, H.; Komori, T.; Seki, M.; Komatsu, T.; et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: an immunopathological study. Brain 2020, 143, 1431-1446. [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.W.; Woodhall, M.R.; Kim, S.H.; Jeong, I.H.; Kong, B.; Kim, G.; Kim, Y.; Park, M.S.; Irani, S.R.; Waters, P.; et al. Longitudinal analysis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in CNS inflammatory diseases. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2017, 88, 811-817. [CrossRef]

- Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Chen, J.J.; Flanagan, E.P.; Tobin, W.O.; Fryer, J.P.; Weinshenker, B.G.; McKeon, A.; Lennon, V.A.; Leavitt, J.A.; Tillema, J.M.; et al. Aquaporin-4 and Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Autoantibody Status Predict Outcome of Recurrent Optic Neuritis. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1628-1637. [CrossRef]

- Rode, J.; Pique, J.; Maarouf, A.; Ayrignac, X.; Bourre, B.; Ciron, J.; Cohen, M.; Collongues, N.; Deschamps, R.; Maillart, E.; et al. Time to steroids impacts visual outcome of optic neuritis in MOGAD. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2023, 94, 309-313. [CrossRef]

- Bruijstens, A.L.; Wendel, E.M.; Lechner, C.; Bartels, F.; Finke, C.; Breu, M.; Flet-Berliac, L.; de Chalus, A.; Adamsbaum, C.; Capobianco, M.; et al. E.U. paediatric MOG consortium consensus: Part 5 - Treatment of paediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2020, 29, 41-53. [CrossRef]

- Whittam, D.H.; Karthikeayan, V.; Gibbons, E.; Kneen, R.; Chandratre, S.; Ciccarelli, O.; Hacohen, Y.; de Seze, J.; Deiva, K.; Hintzen, R.Q.; et al. Treatment of MOG antibody associated disorders: results of an international survey. J Neurol 2020, 267, 3565-3577. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Flanagan, E.P.; Bhatti, M.T.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Dubey, D.; Lopez Chiriboga, A.S.S.; Fryer, J.P.; Weinshenker, B.G.; McKeon, A.; Tillema, J.M.; et al. Steroid-sparing maintenance immunotherapy for MOG-IgG associated disorder. Neurology 2020, 95, e111-e120. [CrossRef]

- Bilodeau, P.A.; Vishnevetsky, A.; Molazadeh, N.; Lotan, I.; Anderson, M.; Romanow, G.; Salky, R.; Healy, B.C.; Matiello, M.; Chitnis, T.; et al. Effectiveness of immunotherapies in relapsing myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2024, 30, 357-368. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Huda, S.; Hacohen, Y.; Levy, M.; Lotan, I.; Wilf-Yarkoni, A.; Stiebel-Kalish, H.; Hellmann, M.A.; Sotirchos, E.S.; Henderson, A.D.; et al. Association of Maintenance Intravenous Immunoglobulin With Prevention of Relapse in Adult Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease. JAMA Neurol 2022, 79, 518-525. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Luo, J.; Hao, H.; Liu, R.; Jin, H.; Jin, Y.; Gao, F. Efficacy and safety of long-term immunotherapy in adult patients with MOG antibody disease: a systematic analysis. J Neurol 2021, 268, 4537-4548. [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Colombo, E.; Gastaldi, M.; Ahmad, L.; Tavazzi, E.; Bergamaschi, R.; Rigoni, E. Beyond Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein and Aquaporin-4 Antibodies: Alternative Causes of Optic Neuritis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Chen, Q.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, X.; Lu, P.; Yan, S.; Wang, M.; Tian, G. Clinical characteristics of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein seropositive optic neuritis: a cohort study in Shanghai, China. J Neurol 2018, 265, 33-40. [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; Prelog, K.; Barnes, E.; Tantsis, E.; Reddel, S.; Henderson, A.; Vucic, O.; Gorman, M.; Benson, L.; Alper, G.; et al. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibodies are Associated with Bilateral and Recurrent Optic Neuritis and have a Distinct Radiological Profile to Multiple Sclerosis or Aquaporin-4 Antibody-associated Optic Neuritis (P3.001). Neurology 2016, 86, P3.001, doi:doi:10.1212/WNL.86.16_supplement.P3.001.

- Ramanathan, S.; Prelog, K.; Barnes, E.H.; Tantsis, E.M.; Reddel, S.W.; Henderson, A.P.; Vucic, S.; Gorman, M.P.; Benson, L.A.; Alper, G.; et al. Radiological differentiation of optic neuritis with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies, aquaporin-4 antibodies, and multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2016, 22, 470-482. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, A.; Cortese, R.; Prados, F.; Tur, C.; Kanber, B.; Yiannakas, M.C.; Samson, R.; De Angelis, F.; Magnollay, L.; Jacob, A.; et al. Optic chiasm involvement in multiple sclerosis, aquaporin-4 antibody-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-associated disease. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2024, 30, 674-686. [CrossRef]

- Cortese, R.; Prados Carrasco, F.; Tur, C.; Bianchi, A.; Brownlee, W.; De Angelis, F.; De La Paz, I.; Grussu, F.; Haider, L.; Jacob, A.; et al. Differentiating Multiple Sclerosis From AQP4-Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder and MOG-Antibody Disease With Imaging. Neurology 2023, 100, e308-e323. [CrossRef]

- Stiebel-Kalish, H.; Lotan, I.; Brody, J.; Chodick, G.; Bialer, O.; Marignier, R.; Bach, M.; Hellmann, M.A. Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer May Be Better Preserved in MOG-IgG versus AQP4-IgG Optic Neuritis: A Cohort Study. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0170847. [CrossRef]

- Pache, F.; Zimmermann, H.; Mikolajczak, J.; Schumacher, S.; Lacheta, A.; Oertel, F.C.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Jarius, S.; Wildemann, B.; Reindl, M.; et al. MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders: a multicenter study of 50 patients. Part 4: Afferent visual system damage after optic neuritis in MOG-IgG-seropositive versus AQP4-IgG-seropositive patients. J Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 282. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, L.; ZhangBao, J.; Zong, Y.; Quan, C.; Wang, M. Comparison of the retinal vascular network and structure in patients with optic neuritis associated with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein or aquaporin-4 antibodies: an optical coherence tomography angiography study. J Neurol 2021, 268, 4874-4881. [CrossRef]

- Sotirchos, E.S.; Filippatou, A.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Salama, S.; Pardo, S.; Wang, J.; Ogbuokiri, E.; Cowley, N.J.; Pellegrini, N.; Murphy, O.C.; et al. Aquaporin-4 IgG seropositivity is associated with worse visual outcomes after optic neuritis than MOG-IgG seropositivity and multiple sclerosis, independent of macular ganglion cell layer thinning. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2020, 26, 1360-1371. [CrossRef]

- Graner, M.; Pointon, T.; Manton, S.; Green, M.; Dennison, K.; Davis, M.; Braiotta, G.; Craft, J.; Edwards, T.; Polonsky, B.; et al. Oligoclonal IgG antibodies in multiple sclerosis target patient-specific peptides. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0228883. [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, R.; Pique, J.; Deschamps, R.; Ciron, J.; Maillart, E.; Audoin, B.; Cohen, M.; Zephir, H.; Laplaud, D.; Ayrignac, X.; et al. Evaluation of the predictive value of CSF-restricted oligoclonal bands on residual disability and risk of relapse in adult patients with MOGAD: MOGADOC study. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2025, 31, 290-302. [CrossRef]

- Jarius, S.; Lechner, C.; Wendel, E.M.; Baumann, M.; Breu, M.; Schimmel, M.; Karenfort, M.; Marina, A.D.; Merkenschlager, A.; Thiels, C.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid findings in patients with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies. Part 2: Results from 108 lumbar punctures in 80 pediatric patients. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 262. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.G.E.; George, W.; Yu, X. The elusive nature of the oligoclonal bands in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2024, 271, 116-124. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Sato, D.K.; Nakashima, I.; Ogawa, R.; Akaishi, T.; Takai, Y.; Nishiyama, S.; Takahashi, T.; Misu, T.; Kuroda, H.; et al. CSF cytokine profile in MOG-IgG+ neurological disease is similar to AQP4-IgG+ NMOSD but distinct from MS: a cross-sectional study and potential therapeutic implications. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2018, 89, 927-936. [CrossRef]

- Hoshina, Y.; Seay, M.; Vegunta, S.; Stulberg, E.L.; Wright, M.A.; Wong, K.H.; Smith, T.L.; Shimura, D.; Clardy, S.L. Isolated Optic Neuritis: Etiology, Characteristics, and Outcomes in a US Mountain West Cohort. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society 2025, 45, 36-43. [CrossRef]

- Hervas-Garcia, J.V.; Pagani-Cassara, F. [Chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy: a literature review]. Rev Neurol 2019, 68, 524-530. [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; McKeon, A.; Hinson, S.R.; Kryzer, T.J.; Pittock, S.J.; Aksamit, A.J.; Lennon, V.A. Autoimmune Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Astrocytopathy: A Novel Meningoencephalomyelitis. JAMA Neurol 2016, 73, 1297-1307. [CrossRef]

- Hagbohm, C.; Ouellette, R.; Flanagan, E.P.; Jonsson, D.I.; Piehl, F.; Banwell, B.; Wickström, R.; Iacobaeus, E.; Granberg, T.; Ineichen, B.V. Clinical and neuroimaging phenotypes of autoimmune glial fibrillary acidic protein astrocytopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of neurology : the official journal of the European Federation of Neurological Societies 2024, 31, e16284. [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Liang, J.; Xu, H.; Huang, Q.; Yang, J.; Gao, C.; Qiu, W.; Lin, S.; Chen, X. Autoimmune glial fibrillary acidic protein astrocytopathy in Chinese patients: a retrospective study. European journal of neurology : the official journal of the European Federation of Neurological Societies 2018, 25, 477-483. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; K, V.C.C.; Kannoth, S.; Raeesa, F.; Misri, Z.; Mascarenhas, D.G.; Nair, S. Autoimmune GFAP Astrocytopathy-Beyond the Known Horizon, India’s First Multifaceted Institutional Experience. Ann Neurosci 2025, 32, 248-258. [CrossRef]

- Gravier-Dumonceau, A.; Ameli, R.; Rogemond, V.; Ruiz, A.; Joubert, B.; Muñiz-Castrillo, S.; Vogrig, A.; Picard, G.; Ambati, A.; Benaiteau, M.; et al. Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Autoimmunity: A French Cohort Study. Neurology 2022, 98, e653-e668. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, H.; Gao, C.; Yu, Q.; Fan, M.; Zhang, L.J.; Zhang, H.; Cong, H.; Wei, Y.; Böttcher, C.; et al. Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Astrocytopathy Based on a Two-Center Chinese Cohort Study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2025, 12, 1813-1822. [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Illán, C.; Esparragosa Vázquez, I.; Zelaya Huerta, M.V.; Rosales Castillo, J.J.; Paternain Nuin, A.; Arbizu Lostao, J.; García de Eulate, M.R.; Riverol Fernández, M. Autoimmune glial fibrillary acidic protein astrocytopathy: case report of a treatable cause of rapidly progressive dementia. J Neurol 2021, 268, 2256-2258. [CrossRef]

- Sechi, E.; Morris, P.P.; McKeon, A.; Pittock, S.J.; Hinson, S.R.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Aksamit, A.J.; Krecke, K.N.; Kaufmann, T.J.; Jolliffe, E.A.; et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein IgG related myelitis: characterisation and comparison with aquaporin-4-IgG myelitis. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2019, 90, 488-490. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; McKeon, A.; Koh, O.S.Q.; Chiew, Y.R.; Purohit, B.; Chin, C.F.; Zekeridou, A.; Ng, A.S.L. Teaching NeuroImages: Linear Radial Periventricular Enhancement in Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Astrocytopathy. Neurology 2021, 96, e2454-e2455. [CrossRef]

- Kraker, J.A.; Chen, J.J. An update on optic neuritis. J Neurol 2023, 270, 5113-5126. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.; Lennon, V.A.; Gadoth, A.; Pittock, S.J.; Flanagan, E.P.; Schmeling, J.E.; McKeon, A.; Klein, C.J. Autoimmune CRMP5 neuropathy phenotype and outcome defined from 105 cases. Neurology 2018, 90, e103-e110. [CrossRef]

- Uysal, S.; Li, Y.; Thompson, N.; Conway, D.; Levin, K.; Kunchok, A. Prognosticating Outcomes in Patients with CRMP5-IgG Associated Paraneoplastic Neurologic Disorders (P5-5.019). Neurology 2023, 100, 1506, doi:doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000201956.

- Yu, Z.; Kryzer, T.J.; Griesmann, G.E.; Kim, K.; Benarroch, E.E.; Lennon, V.A. CRMP-5 neuronal autoantibody: marker of lung cancer and thymoma-related autoimmunity. Ann Neurol 2001, 49, 146-154.

- Kidd, D.P.; Burton, B.J.; Graham, E.M.; Plant, G.T. Optic neuropathy associated with systemic sarcoidosis. Neurology Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation 2016, 3, e270, doi:doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000270.

- Lin, Y.-C.; Wang, A.-G.; Yen, M.-Y. Systemic lupus erythematosus-associated optic neuritis: clinical experience and literature review. Acta Ophthalmologica 2009, 87, 204-210. [CrossRef]

- Wei-Qiang, T.; Shi-Hui, W. Primary Sj?gren’s syndrome related optic neuritis. International Journal of Ophthalmology 6, 888-891.

- Kardum, Ž.; Milas Ahić, J.; Lukinac, A.M.; Ivelj, R.; Prus, V. Optic neuritis as a presenting feature of Behçet’s disease: case-based review. Rheumatology International 2021, 41, 189-195. [CrossRef]

- Junek, M.; Khalidi, N. ANCA-Associated Vasculitis For the Allergist and Immunologist: A Clinical Update. Canadian Allergy & Immunology Today 2023, 3, 13–16. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Magnetic resonance imaging indicator of the causes of optic neuropathy in IgG4-related ophthalmic disease. BMC Med Imaging 2019, 19, 49. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Romo, K.A.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, A.; Paczka, J.A.; Nuño-Suarez, M.A.; Rocha-Muñoz, A.D.; Zavala-Cerna, M.G. Optic Neuropathy Secondary to Polyarteritis Nodosa, Case Report, and Diagnostic Challenges. Frontiers in Neurology 2017, Volume 8 - 2017. [CrossRef]

- Szydełko-Paśko, U.; Przeździecka-Dołyk, J.; Nowak, Ł.; Małyszczak, A.; Misiuk-Hojło, M. Ocular Manifestations of Takayasu’s Arteritis—A Case-Based Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 3745.

- Clemmensen, K.; Akrawi, N.; Stawowy, M. Irreversible optic neuritis after infliximab treatment in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2015, 50, 1508-1511. [CrossRef]

- Suvajac, G.; Stojanovich, L.; Milenkovich, S. Ocular manifestations in antiphospholipid syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 2007, 6, 409-414. [CrossRef]

- Taga, A.; Wali, A.; Eberhart, C.G.; Green, K.E. Teaching NeuroImage: Giant Cell Arteritis With Optic Perineuritis. Neurology 2024, 103, e209707, doi:doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209707.

- El Mayel, A.; Amor, H.B.; Sellem, I.; Mesfar, R.; Khochtali, S.; Ksiaa, I.; Khairallah, M. Intermediate uveitis associated with Cogan’s syndrome. Acta Ophthalmologica 2022, 100. [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.-S.; Lu, D.-W.; Chen, J.-T. Ankylosing Spondylitis Presented as Unilateral Optic Neuritis in a Young Woman. Ocular immunology and inflammation 2011, 19, 115-117. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, N.; Dubey, A.; Kumar, K. Bilateral Optic Neuropathy in Association with Diffuse Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis with Interstitial Lung Disease. Ocular immunology and inflammation 2024, 32, 784-787. [CrossRef]

- Mansız-Kaplan, B.; Nacır, B.; Mülkoğlu, C.; Pervane-Vural, S.; Genç, H. Undifferentiated connective tissue disease presenting with optic neuritis and concomitant axial spondyloarthritis: A rare case report. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil 2021, 67, 111-114. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, N.; Alhmood, A.; Mawri, F.; Kaddurah, A.; Diskin, D.; Abuhammour, W. Bilateral optic neuritis in a patient with Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr Infect Dis 2009, 04, 301-303. [CrossRef]

- Wilf-Yarkoni, A.; Zmira, O.; Tolkovsky, A.; Pflantzer, B.; Gofrit, S.G.; Kleffner, I.; Paul, F.; Dörr, J. Clinical Characterization and Ancillary Tests in Susac Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2024, 11, e200209. [CrossRef]

- Della Zoppa, M.; Bertuccio, F.R.; Campo, I.; Tousa, F.; Crescenzi, M.; Lettieri, S.; Mariani, F.; Corsico, A.G.; Piloni, D.; Stella, G.M. Phenotypes and Serum Biomarkers in Sarcoidosis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, D.; van de Beek, D.; Brouwer, M.C. Clinical features, treatment and outcome in neurosarcoidosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol 2016, 16, 220. [CrossRef]